Linda Collison's Blog, page 11

July 3, 2016

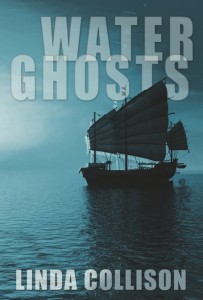

Water Ghosts — the movie?

There are many ways to tell a story. Ever since I stood on board Intrepid Dragon II in Honolulu’s Ala Wai Small Boat Harbor I’ve envisioned Water Ghosts, the movie. I wrote the novel but the idea of a feature film still haunts me. I can hear the dialogue, the music, the scary voices of the ghosts in my head. I can see their dead faces peering up at me from beneath the water. I can envision the colorful splendor of Imperial Ming Court of early 15th century China.

There are many ways to tell a story. Ever since I stood on board Intrepid Dragon II in Honolulu’s Ala Wai Small Boat Harbor I’ve envisioned Water Ghosts, the movie. I wrote the novel but the idea of a feature film still haunts me. I can hear the dialogue, the music, the scary voices of the ghosts in my head. I can see their dead faces peering up at me from beneath the water. I can envision the colorful splendor of Imperial Ming Court of early 15th century China.

After actor Aaron Landon gave voice to the characters in his terrific narration of Water Ghosts on the audio book, I was convinced; I had to try to get the movie made.

One person can write a novel but it takes a team to produce a film. Even though Water Ghosts has not been optioned by any major studios I decided to look into what it would take to make a movie. With all the independent films being produced these days, maybe I have a chance.

I have a little experience writing scripts but Water Ghosts is a big project. I wanted help so I went to Hollywood and attended a weekend book-to-screen workshop to learn the basics and to connect with some people in the business. I pitched my novel, got some valuable feedback — as well as connected with a producer and a young screenwriter interested in the project.

When books are adapted to the screen the story changes, often significantly. To be commercially viable feature movies must fit into a genre. The novel Water Ghosts is marketed as YA — young adult — but the producer I’m working with steered me away from making a YA movie. Most successful “teen films” are franchised (Twilight, Hunger Games). I also learned that to develop Water Ghosts as a family movie meant that I couldn’t mention, much less show, castration — which is a major theme for Yu, the Ming Court eunuch. So family film was out. I might have gone with straight drama/adventure but decided to focus on the horror aspects of the story.

Chinese mythology and folklore is fairly dripping with horror. Ghosts, gods, and demons vie for power and use humans like pawns in their eternal struggles much the same way as the Greek pantheon plays us. Fear — terror — horror — all play a big role in the novel, so why not make a horror film? Horror movies are popular, inexpensively made, and a lot of independents want to make them. With a professionally written script based on a successful novel, I have a chance of attracting a producer and finding a studio dying to make Water Ghosts. At least, that’s the dream.

Intrepid Dragon II, the junk that inspired the novel, has been used as a movie and television set in the past. Who knows? Maybe she’ll be cast as the Good Fortune? Fingers crossed…

Water Ghosts, the novel, is available for download from Smashwords and Amazon.com. The audiobook, narrated by actor Aaron Landon, is available from Audible. The trade paperback edition can be ordered from Amazon or from your favorite independent brick-and-mortar bookstore.

Water Ghosts, the novel, is available for download from Smashwords and Amazon.com. The audiobook, narrated by actor Aaron Landon, is available from Audible. The trade paperback edition can be ordered from Amazon or from your favorite independent brick-and-mortar bookstore.

A horror film? What do you think? As always, I appreciate helpful comments and shares on social media.

Save

Save

May 30, 2016

The power of Setting in fiction

I’m reading Birds Without Wings, by Louis de Bernieres — a novel I chose partly because I enjoyed Corelli’s Mandolin and partly because the particular setting is one I know so little about. Birds Without Wings is the story of a small coastal town in South West Anatolia in the dying days of the Ottoman Empire. I was lured by the setting – an element important to me as both a reader and a writer – and I bought the book on the promise of setting and my confidence in the author’s proven ability to transport me.

Is it because I like to travel that I’m drawn to novels that give me a vivid sense of place and time?

As fiction writers we hear a lot of advice about the importance of plot, conflict, and character development. Stories happen to people (or other sentient life forms). What happens is plot. Characters and plot make a story but stories don’t take place in a void, they grow out of a particular place at a particular time in history. This time and place is the story’s setting. Setting is more than a backdrop on a stage — it’s the medium, the stew, the garden in which the story is born and takes shape. Setting directly affects plot and character development.

There are different techniques writers employ to portray setting. One way is to write an establishing shot for the beginning and subsequent scenes, shooting with a wide angle lens, so to speak. The establishing shot is a sentence or paragraph that reveals the environment and places the reader in the scene – before focusing the lens on the protagonist and his actions or on the thoughts inside the character’s head.

Hemingway use of the establishing shot is evident in the short story “Hills Like White Elephants.” Here are the opening three sentences: The hills across the valley of the Ebro were long and white. On this side there was no shade and no trees and the station was between two lines of rails in the sun. Close against the side of the station there was the warm shadow of the building and a curtain, made of strings of bamboo beads, hung across the open door into the bar, to keep out flies.

In these three sentences (each one a little longer and more complex than the one before it) the author sets us in the scene. Even if we don’t know where the Ebro River is at first, we know it is a dry and barren place through which a river and railroad tracks run – a place so hot even the shade cast by the building is warm. The curtain made from strings of bamboo beads is a tangible object that forms a bridge from something we know or have seen before to this particular setting. By the end of the paragraph (three more sentences) we know the story takes place at a remote train station in Spain between Barcelona and Madrid and it involves an American man and a “girl.” After this establishing shot of six sentences Hemingway slips into his effective style of terse dialogue and short, simple, powerful sentences to develop the characters and reveal the inherent story. (Tim Tomlinson of the New York Writers Workshop talks about Hemingway technique on pg. 57 of The Portable MFA in Creative Writing. The story “Hills Like White Elephants” is available online in pdf format and is free to download.)

Neal Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane beings with the protagonist driving down a long, narrow, winding, bumpy road. As we ride along with him we feel we’re driving back in time and we’re not entirely sure it’s a good place we’re headed.

Neal Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane beings with the protagonist driving down a long, narrow, winding, bumpy road. As we ride along with him we feel we’re driving back in time and we’re not entirely sure it’s a good place we’re headed.

Developing a rich setting – is it accomplished through experience and imagination – or is it through the mechanics of craft? Both, I’ve discovered. The immersive technique of writing helps bring the setting into focus. Writers who have lived or can deeply imagine their settings and can bring to life details otherwise unseen by a writer who crafts by technique alone. Details and nuances of setting can be uncovered or added on during a second or third draft. Don’t go overboard – less is more – according to twenty-first century tastes. By choosing just the right details and the right words to convey the atmosphere – the physical, emotional, political, and the cultural environment – you immerse the reader in setting without bogging her down.

Deconstruct your favorite stories for setting, to see how its done. Browse novels in the library, at the bookstore, or online (Amazon’s “look inside” feature) to find techniques that resonate with you.

H.P. Lovecraft’s The Shunned House is all about setting – can a setting be the protagonist?

Joseph Conrad’s settings – often hot, tropical, shipboard, Victorian – are rich in mood, atmosphere, and moral conflict.

She floated at the starting point of a long journey, very still in an immense stillness, the shadows of her spars flung far to the eastward by the setting sun. At that moment I was alone on her decks. There was not a sound in her –and around us nothing moved, nothing lived, not a canoe on the water, not a bird in the air, not a cloud in the sky. In this breathless pause at the threshold of a long passage we seemed to be measuring our fitness for a long and arduous enterprise the appointed task of both of our existences to be carried out, far from human eyes, with only sky and sea for spectators and for judges.

She floated at the starting point of a long journey, very still in an immense stillness, the shadows of her spars flung far to the eastward by the setting sun. At that moment I was alone on her decks. There was not a sound in her –and around us nothing moved, nothing lived, not a canoe on the water, not a bird in the air, not a cloud in the sky. In this breathless pause at the threshold of a long passage we seemed to be measuring our fitness for a long and arduous enterprise the appointed task of both of our existences to be carried out, far from human eyes, with only sky and sea for spectators and for judges.

In this, the second paragraph of the novella The Secret Sharer, the author not only puts us on a sailing vessel in deathly quiet waters on the eve of a long voyage, he also evokes a supernatural atmosphere in his introspective tone and hints at a struggle of some sort, as well as a mystery.

Details of setting can mirror the mood or it can be in opposition to it. For example Shirley Jackson’s short story The Lottery begins on a beautiful blue sky day when nothing bad could possibly happen:

The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day; the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green.

There is inherent tension here because the reader knows something is going to happen, but what? And to whom?

Another way to reveal the setting is piece by piece, weaving minute but important details into each paragraph – details that create atmosphere and remind us where we are. Neil Gaiman does this particularly well in his literary coming-of-age fantasy — except he wants to make us wonder when we are — have we traveled back in time, or forward in time? The place is familiar but is it now or is it then?

Part of the trick of portraying an exotic place or an historical time is not just showing what is unique about that setting but connecting us to sensations that are familiar to a modern reader; details or descriptions that form a bridge between what we’re familiar with and what we’ve never experienced first-hand.

Setting is often thought of as adjectives, phrases and entire sentences devoted to description, yet too much detail bogs the reader down the way a forest of kelp clings to a swimmer’s limbs. Instead of objects or description of weather, clothing, or architecture, think focus. What’s important to the story in the particular paragraph, the particular sentence you are writing? What do you want your reader to see or hear that grounds them in the setting – the place and time where this particular story was born? Don’t describe everything the character sees in the room, choose one or two details and work them into the action or dialogue.

Within the structure of a declarative sentence whole worlds can be evoked. Nouns and verbs can help express setting, even in an action sentence stripped of adjectives, adverbs and modifying phrases. This is setting at its most elemental. The mere action of moving a character from one place to another can evoke different settings. Nouns, verbs and direct objects are freighted with meaning so that even a six word sentence gives a hint of time and place. Here’s a simple exercise: Using only a noun, verb, and prepositional phrase or direct object, try to reveal a different setting.

The couple strolled through the park

The couple strolled through the park

The carriage clattered across the cobblestones

The carriage clattered across the cobblestones

The teenagers raced down the highway

The teenagers raced down the highway

Having chosen the best nouns and verbs for the job you can now flesh out some sentences with descriptive clauses to enrich the story’s environment. A character’s thoughts, personal values, cultural mores and prejudices can also indicate setting. Don’t forget dialogue but avoid overusing dialect and slang; it can be distracting, confusing, or even annoying. Instead, examine speech patterns, rhythms and vocabulary to suggest time and place.

Most of my own fiction is inspired by setting. In writing Water Ghosts I wanted to explore a setting within a setting, within a larger setting. That is, a boat carrying ghosts from the past as well as living souls, adrift on a vast unfathomable ocean. The story had its beginnings in my imagination aboard a real vessel — the Intrepid Dragon II — moored at the Ala Wai Small Boat Harbor on Oahu where Bob and I kept our own sailboat for many years. My experiences at sea further fueled the setting as well as the plot. Yet it took numerous drafts to portray the setting in a powerful way – as powerful as the ocean itself. Or at least that was my intention.

On the advice of a writer whose opinion I value, I added an establishing shot at the beginning of the first chapter, showing the boat Good Fortune at the crumbling docks of the Marianas Marina in Honolulu. Since most of the story takes place aboard this floating stage it was important to show the reader the boat from the protagonist’s perspective on the first page. In an earlier draft I had this information but it was further along in the chapter. Moving it to the beginning felt right and I thanked the writer (Rick Spilman, Old Salt Press ) for this suggestion. Here then, is the establishing shot.

Chapter 1

The doomed ship is set to sail at ten A.M. and I am to be aboard. The taxi has dropped us off at the marina – my mother, her boyfriend and me. They’re here to see me off.

From the parking lot I can see it. Good Fortune is unmistakable because it’s bigger than the other boats and because it’s old and foreign-looking. Three masts rise up like pikes from the rectangular deck. A tattered pennant hangs limply from the smallest one. Faded yellow silk.

I don’t want to go but Mother is making me. Walking toward it, carrying my sea bag, I already feel like I’m drowning. Dragging my feet along the rickety wooden pier, past neglected powerboats and sailboats covered with blue plastic tarps, I’m trying to resign myself to my fate. I’m trying to do what Dad used to tell me to do when I was afraid. Think of something funny! But nothing funny comes to mind.

Looking around at this run-down dockyard in an industrial park near the Honolulu International Airport I’m thinking it’s wrong, it’s all wrong. Hawaii is not paradise – at least, not for me. A jet takes off, flying low overhead, drowning us out momentarily with its thunderous roar. Mother covers her ears with her hands and squeezes her eyes shut until it passes. The boyfriend glances at his big gold watch and grins.

“Nine-forty,” he says. “You’ll be boarding soon.”

I wrote the first draft of Water Ghosts under the working title “Blue Milieu,” which gives you some idea of how important the setting was to me. More than background, setting surrounds us and is organic to each story we write. Setting influences plot and character development and provides a portal to the imagined past and future.

Bon voyage…

Water Ghosts, as narrated by Aaron Landon

James McCafferty, a 15-year-old troubled by the visions and voices in his head, is a unwilling passenger aboard a Chinese junk — an adventure-therapy sailing program for teens with behavior problems. Once at sea James’s premonitions of doom begin to take shape in the form of long-dead ghosts who populate the hold of the ship. One in particular, the spirit of Yu, a young courtier from the Ming Dynasty, makes himself known to James and seemingly tries to befriend him. Then one by one the adults on board go missing and the teens are left alone to fend for themselves — and struggle for their very lives.

Save

May 17, 2016

Water Ghosts — Read First Chapter here

Water Ghosts

Copyright © Linda Collison 2015

Published by Old Salt Press, LLC

ISBN: 9781943404001

LCCN: 2015941395

Publisher’s Note: This is a work of fiction. Certain characters and their actions may have been inspired by historical individuals and events. The characters in the novel, however, represent the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

——

Under heaven nothing is more soft and yielding than water.

Tao Te Ching

——-

Water Ghosts

A novel

by Linda Collison

Chapter One

The doomed ship is set to sail at ten A.M. and I am to be aboard. The taxi has dropped us off at the marina – my mother, her boyfriend and me. They’re here to see me off.

From the parking lot I can see it. Good Fortune is unmistakable because it’s bigger than the other boats and because it’s old and foreign-looking. Three masts rise up like pikes from the rectangular deck. A tattered pennant hangs limply from the smallest one. Faded yellow silk.

I don’t want to go but Mother is making me. Walking toward it, carrying my sea bag, I already feel like I’m drowning. Dragging my feet along the rickety wooden pier, past neglected powerboats and sailboats covered with blue plastic tarps, I’m trying to resign myself to my fate. I’m trying to do what Dad used to tell me to do when I was afraid. Think of something funny! But nothing funny comes to mind.

Looking around at this run-down dockyard in an industrial park near the Honolulu International Airport I’m thinking it’s wrong, it’s all wrong. Hawaii is not paradise – at least, not for me. A jet takes off, flying low overhead, drowning us out momentarily with its thunderous roar. Mother covers her ears with her hands and squeezes her eyes shut until it passes. The boyfriend glances at his big gold watch and grins.

“Nine-forty,” he says. “You’ll be boarding soon.”

“Oh, James! It looks like an old pirate ship, doesn’t it?” Mother’s perky voice edges toward hysteria. “A Chinese pirate ship, how cool is that! You are going to have the time of your life. I wish I was going!” She continues to talk but I can’t hear her anymore. Her words are bursts of color, blinding me. I look away.

I see things other people don’t see.

The old wooden ship lists in its slip. Doesn’t look anything like the picture on the website. Up close the Good Fortune doesn’t look fortunate at all. It looks bedraggled and unseaworthy; it looks like it’s about to sink right here at the dock. I think of a lame cormorant, riding low in the water, awaiting its fate.

Cormorants are different from most other water birds. Cormorants will drown if they don’t dry their feathers. That’s why you see them on a pier or on shore with their dark, dripping wings spread out in the sun and the wind. But they’re the bravest of birds because they are not really at home in the water; they’re not as buoyant as ducks and geese. They’re marginal creatures, living on the edge. They have to work harder to get by.

My father taught me about cormorants. He was a wildlife journalist, specializing in birds. Dad always said he was going to take me on a photo shoot to follow the sandhill crane migration. It was going to be a man-expedition, he promised, an epic father-son trip from Canada to Mexico. We never went.

On the front side of the boat a painted, peeling eye stares at me. A dead man’s stare. An eye that never closes. Is there a matching eye on the other side? I don’t want to look, I don’t want to know.

“What a piece of junk,” I say. “No wonder they call them junks. “Can’t you see it’s a scam? How much did you pay for this, anyway?”

“Don’t be ungrateful, James,” Mother shoots back. “You’re so unappreciative. This is Hawaii. You’re starting your summer adventure in Hawaii. How many kids your age get to do that? You are so lucky!” Orange light leaps out from her head, a solar flare. The intense light triggers the song.

With a yo-heave-ho and a fare-you-well

And a sullen plunge in the sullen swell

Ten fathoms deep on the road to hell

I hear things other people don’t hear.

The dead men sing as they march through my head, the men from the dream. And now the dream is bringing itself to life in the form of this summer adventure program. Somebody’s sick idea of “helping” kids with behavior problems, a sort of boot camp for misfits. Mother found this program on the Internet. Or maybe the program found her, summoned her somehow. She doesn’t know she’s being influenced by people she has never met, some of them dead.

“What’s the matter, James?” Her concern is real, I feel it, little ripples of warmth. But she doesn’t get it. At all. Right now we’re standing side-by-side but we’re worlds apart. Like birds and humans, we merely coexist.

I’d like to tell her what the matter is – but what exactly am I going to say? Mother, the dead men are singing, it’s a bad sign. The boat is a doomed cormorant that can’t dry its wings. That’s the kind of talk that gets me into trouble. She hates it when I repeat what they say; she’s afraid I’m psychotic or something.

“James?” Gone is the false cheerfulness. Now her aura crackles and spits. A Fourth of July sparkler penetrating my skin with hot little darts.

Mother’s face is splotched red from the Honolulu heat. Her once pretty face, now unnaturally fragile, a face stretched too thin, too tight. A face that’s known too many Botox injections, too many interventions, a face carefully composed yet beginning to crumble. Yet even now I can see the blue light of her love for me shining through the veil of disappointment. Disappointment and shame.

I look normal enough on the outside (at least, I think I do) but inside me there’s this, like, hole – a cavity – that I’m constantly trying to avoid. Sometimes I hear my dead father’s voice calling me. James! But his voice doesn’t come from the hole inside, it comes from behind me, and when I hear it my heart flutters. It’s not really him, it’s the echoes of his words bouncing around the universe, never at rest. Then comes the weight of his hand on my left shoulder and the sound of him breathing hard, like he’s been running to catch up. Sometimes when I close my eyes I see his face against the backs of my eyes, like a poor quality video. His lips are moving but I can’t make out what he’s trying to tell me.

Mother’s boyfriend interrupts my thoughts; his voice is a Doberman’s whine.

“He’ll be fine. You’ll be fine, won’t you, kid? Come on, now. Man up!” He reaches out to grip my shoulder but I step back to avoid it, nearly falling off the dock. I’ve hated all my mother’s boyfriends. I know what it is they want and it sickens me.

She smiles, her lips tight. “It’s just – now that we’re here – he seems so young. Compared to the others.”

And now I see them – three guys sitting on the dock at the end of the pier. They’re leaning against new Urban Outfitter gear bags, all sprawled out with their long legs and arms, their hair spiked up with gel. They are cut from the same mold, they could be brothers, they could be triplets.

They’re going aboard with me, I realize. We’re all in the same boat; we’re all going down together. These guys don’t seem to know it, or care. They’re all holding cell phones, making last minute texts to their friends back home, cigarettes hanging from their mouths. I didn’t bring any cigarettes, I don’t smoke. But I did bring my lighter, I carry it everywhere because you never know. I brought my cell phone too, but it’s already dead and there’s no way to charge it on the boat – that’s what it said on the website. I don’t know why I even brought it, except the weight of it, deep in the pocket of my shorts, feels solid. Comforting.

My shipmates have man-legs, I envy them that. . Coarse hair covers their muscular calves like sea grass. Billabong shorts hang low on their hips, they look like some kind of California surf gang. Their feet are all huge in their ragged Converse All-Stars: black, brown, red. These three are the shit and they know it. These fuckers will taunt me, they will make my life miserable; of this I’m sure.

“He’ll be fine. He just hasn’t got his growth spurt yet. Your boy’s old enough, hell, he’s fifteen. Aren’t you, Jim? You’ll be fine.” The Jerk-du-Jour looks at his watch again. His face is shiny, his Tommy Bahama aloha shirt is all creased and damp, and his gut presses against it like he’s pregnant. “It’s not like he’s going off to war. This is just a cruise, a floating summer camp. They used to send kids like him to military school. Kids these days have all gone soft. Now they get to go sailing the South Pacific. Pretty sweet deal, if you ask me, right Jim?” He has the nerve to wink at me, like we’re buds. Like we share a secret. I hate that he calls me Jim.

The truth is I’m here because my mother wants to be rid of me. She can’t deal with what I am, with what I’m becoming. She needs me gone. Not like dead gone, just out of sight, out of mind for the summer. So she and the jackass boyfriend can – ugh – I can’t let myself think about what it is they want to do with each other when I’m not around.

Last summer it was a different boyfriend (I forget his name, I forget all of their names) and the Teens for Christ Summer Camp for me. There I endured six weeks of forced socialization, thrown in with people I had nothing in common with. Of course I was immediately rejected from their group, expelled into the void of oblivion where I remained in orbit around Planet Jesus like a piece of space junk – potentially dangerous but mostly forgotten, a reflected light passing overhead. What were the odds of my re-entry? The resident life forms ignored me. .

But this summer is going to be worse. Much worse.

*

“All hands!” a man bellows through a bullhorn. “Ten minutes ‘til cast-off!”

Was that the captain? His voice reverberates through my bones like the crash of a gong and I nearly piss my pants with fear. This is it. This is where I board the boat, never to be heard from again. Mother bends her head for a kiss. I feel her warm lips brush my left ear as I turn my head away. She touches my shoulder, like she’s afraid of me.

“I’ll miss you, Jamey, honey. Love you!”

I want her to hug me, to be enfolded in those fake-tanned arms. “You don’t have to miss me, Mother. You could take me home.”

She stiffens and a wave of white light shoots from her head, a scorching flame, a solar flare. She is thinking, You ungrateful brat! She’s also singed with guilt. I can smell her guilt like a slice of bread stuck in the toaster, smoke filling the kitchen.

“It’s not every kid who gets to go sailing on a real Chinese junk for the summer,” says the boyfriend, backing her up. Wanting me out of the way. Like he’s the one who paid for it. Maybe he was, for all I know. I don’t think we have that kind of money.

The energy pulsates from her body, so intense I’m afraid she’ll spontaneously combust. Her lips move but the words are drowned out by the dead men from the black hole inside me, chanting that stupid poem again.

‘Twas a cutlass swipe, or an ounce of lead

Or a yawning hole in a battered head

And the scuppers glut with a rotting red

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum…

END of CHAPTER ONE…

Available in trade paperback, electronic and Audible editions wherever good books are sold

May 16, 2016

Beyond Research: Creating Verisimilitude in Historical Fiction

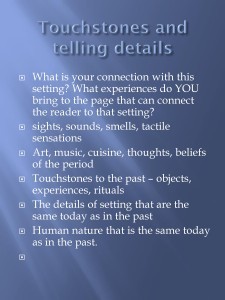

Here are a few of the slides from my power point outline, Beyond Research, shared at the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writer’s spring Genre Con, May 14, at Table Mountain Inn in Golden, Colorado. The keynote and morning session was given by Kristin Nelson and Angie Hodapp of Nelson Literary Agency. The afternoon was devoted to craft in genre breakout sessions.

Here are a few of the slides from my power point outline, Beyond Research, shared at the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writer’s spring Genre Con, May 14, at Table Mountain Inn in Golden, Colorado. The keynote and morning session was given by Kristin Nelson and Angie Hodapp of Nelson Literary Agency. The afternoon was devoted to craft in genre breakout sessions.

Rebecca Bates — Mystery Linda Collison — Historical Fiction Nathan Lowell — SciFi/Fantasy

Bernadette Marie — Romance Aaron Michael Ritchey — YA

The works-in-progress of the writers in my group is indicative of the wide spectrum of historical novels being written and published today. Our stories include historical mystery, historical fantasy, historical paranormal, historical adventure, literary historical, family sagas, fictional memoir, and contemporary novels with strong historical elements. Interest in historical fiction has never been stronger.

The importance of setting is something all historical fiction has in common — and it’s generally agreed that these stories takes place before the author was born, usually set 50 years or more in the past. Setting isn’t arbitrary; a story happens in a particular place and time for a reason. Setting affects character, plot, mood, and tone.

But how do we go beyond gathering events, dates, and second-hand details to make our setting feel real? How can we bring first-hand authenticity to the page?

While there are effective techniques a writer can use to enhance setting, credibility can’t really be crafted. The old “write what you know best” is what leads to convincing settings.

To tap into our own individual wells of verisimilitude we discussed our personal connections to our stories. I asked the group to consider:

What drew you to write about your particular time & place? How did you fall in love with your setting? What problems does your character face that are inherent to the setting?

What areas of expertise do you have; what skills, hobbies, and life experiences can you take back to the past with you to enrich your story and add meaningful and credible detail?

For me, it was my sailing experiences and my nursing experiences. Another woman has a biomedical background, having worked for the Federal Drug Administration. She takes her 21st century knowledge in writing about medieval herbalists and apothecaries. Several writers had a deep interest in genealogy and were writing novels based on the immigration stories of their own ancestors. These personal connections and experiences give our stories conviction and authority and direct our focus. We bring our own past and passions to the page.

Discovering your personal connection to the story and using it with authority gives your work verisimilitude. It’s also part of your author platform. Be sure to mention it in your bio; use it to engage your readers.

March 9, 2016

Water Ghosts a Foreword Reviews Book of the Year Finalist

Foreword Reviews Finalist — Water Ghosts

Today, Old Salt Press is pleased to announce Water Ghosts has been recognized as a finalist in the 18th annual Foreword Reviews’ INDIEFAB Book of the Year Awards, in the Young Adult category. Here is the complete list:

https://indiefab.forewordreviews.com/finalists/2015/

Each year, Foreword Reviews shines a light on a select group of indie publishers, university presses, and self-published authors whose work stands out from the crowd. In the next three months, a panel of more than 100 volunteer librarians and booksellers will determine the winners in 63 categories based on their experience with readers and patrons.

“The 2015 INDIEFAB finalist selection process is as inspiring as it is rigorous,” said Victoria Sutherland, publisher of Foreword Reviews. “The strength of this list of finalists is further proof that small, independent publishers are taking their rightful place as the new driving force of the entire publishing industry.”

Foreword Reviews will celebrate the winners during a program at the American Library Association Annual Conference in Orlando, Florida in June. We will also name the Editor’s Choice Prize 2015 for Fiction, Nonfiction and Foreword Reviews’ 2015 INDIEFAB Publisher of the Year Award during the presentation.

About us: Old Salt Press is an independent press catering to those who love books about ships and the sea. We are an association of writers working together to produce the very best of nautical and maritime fiction and non-fiction. We invite you to join us as we go down to the sea in books.

About Foreword: Foreword Magazine, Inc is a media company featuring a Folio:-award-winning quarterly print magazine, Foreword Reviews, and a website devoted to independently published books. In the magazine, they feature reviews of the best 170 new titles from independent publishers, university presses, and noteworthy self-published authors. Their website features daily updates: reviews along with in-depth coverage and analysis of independent publishing from a team of more than 100 reviewers, journalists, and bloggers. The print magazine is available at most Barnes & Noble and Books-A-Million newsstands or by subscription. You can also connect with them on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and Pinterest. They are headquartered in Traverse City, Michigan, USA.

February 21, 2016

Yankee Moon — Chapter 4

Landfall: Havana

Andromeda slowed to a drift and we dropped anchor into the muddy bottom on the far side of Havana Bay. A Spanish Customs sloop watched us all the way and was already heading toward us with all due speed. A show of our false papers and some silver to line his pocket seemed to satisfy him – at least, for a while. If we lingered too long, he would be back for more, and I had none to spare.

My plan was to get it done quickly and leave for home as soon as possible. First I had to find my contact, a man called Sancho. Right at that moment, it seemed quite impossible. Perhaps Sancho would find us.

We were anchored off Regla, a small fishing village in the back bay, a few miles across the water from the city of Havana – the very same city we had besieged three years before, in the summer of 1762. Our hard-won prize had been handed back to Spain in the peace treaty, six months later. And now the rebuilding of the city – and the fort we had taken. Alejandro O’Reilly, the Irish-born governor of Havana, was overseeing the re-design and enlargement of the fort –it was to be unconquerable, they said. Perhaps. But in the meanwhile adventurers of many nationalities were making profits in trade. The savvy O’Reilly had essentially turned Havana into a free port, for a short time. And now, though the restrictions against trade were once again in effect, nobody seemed to pay them any mind –as long as the customs officials were given their due. British and American ships were bringing building materials and machinery, flour and foodstuffs, and Africans by the thousands. This island would soon have sugar plantations to rival Jamaica.

All around us now, hustle, hustle, goodwill and prosperity. Englishmen fraternizing with habaneros, with French, Dutch and Danes, everyone trying to make a discreet profit before Spain shut the door again. That’s all we were looking for. Not empire, just a return on our investment and labor.

At sunset I changed into a fresh shirt and neck stock, slipped into my waistcoat, donned my wig and hat and launched the ship’s boat, heading to a shabby waterfront pothouse on Regla’s shore. This was where I hoped to meet Sancho; this was where I had met him the last time I was here. Sancho’s counting house, he had said with a grin. Indeed, the establishment had no sign, no name in print. Everyone knew it as Sanchos.

“Aguardiente?” the matron asked, resting her plump elbows on the plank of polished wood that was the serving bar. The cane liquor they called aguardiente was a vile spirit. A man must be low indeed to let that spirit pass his lips. I thought of the fine Rhode Island rum I had to sell.

“No, gracias. I’m here to see Sancho.”

The senora winced at my bad Spanish. “Of course you are. Señor Sancho, he’s a busy man.” She looked me up and down with shrewd black eyes as if she was inspecting a side of beef for maggots. The mole beneath her left eye quivered ever so slightly. “You are Inglés.” It was an accusation. We had broken El Morro, destroyed their forts, damaged their fine homes, humiliated them. Now that Havana was theirs again they held us in disdain but welcomed the goods we brought and defied their own king’s law to buy them.

“I was born of an Englishman,” I said with a slight sniff of superiority, bred into me. “But I haven’t seen her shores in years. The sea is my proper home.”

She shrugged and allowed me a jaded smile. “It’s all the same to me, señor, where you come from. Havana is a regular barnyard these days. Pigs, goats, chickens, all grubbing together. But all animals must drink. What are you drinking, inglés?”

“I’ll have a pint of ale, señora,” I said, overlooking the insult. Indeed, it sounded like a farmyard – the brays and squawks of men laughing, talking in a variety of languages, loud with their liquor. Even though Cuba had been returned to Spain and officially closed once again to outsiders, it wasn’t closed at all. Havana was essentially a free port; Havana was prospering and no one wanted to put a stop to that.

The matron brought my ale –warm, flat, and slightly sour. I drank it down, not caring, and ordered a second.

“Relax, inglés. Stay awhile. Nothing happens fast in Regla. Have some supper while you wait for your friend.” It was an order I couldn’t refuse. I took my second pint and found a chair in front of a barrel in the far corner of the room where I waited for whatever fare she was serving up. Fish, I expected, but instead it was goat stewed with peppers and plantains. Only in Havana would this taste good, I realized, lifting the first spoonful to my mouth. What it needs in a bit of Rhode Island johnnycake to soak up the broth – and I had barrels of cornmeal in the hold to sell.

Not wanting to invite company, I pulled out my little pocket book and pretended to look over some accounts. The last thing I wanted to do was converse with someone. I was here to make a trade and the sooner I could do so, the better. With any luck we could exchange goods quickly and be on our way back north in a day or two.

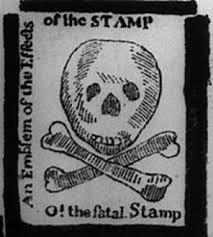

Glancing around the dark room I saw I wasn’t the only one who seemed to be waiting for someone. A den of freebooters, this was, yet I was neither pirate, thief, nor smuggler. A Rhode Islander avoiding unjust taxes is quite a different animal than a common smuggler. Besides, the war was over. We were no longer trading with the enemy, we were trading with neighboring colonies for mutual benefit. Did that make it right? By whose law? By a Parliament we had no voice in; a Parliament who was overstepping their bounds and directly taxing the colonies to raise revenues.

Enough of these thoughts. What do I know? Precious little when it comes to governments and the rights of man. My schooling prepared me to bang at the harpsichord, speak French, dance the quadrille, and embroider a collar –all badly. The only thing I excelled at was riding; I could ride a horse with the best of them. Oh, but why think of those days, they’re gone. And where is Sancho? I want to go back to my boat and sleep. This squalid tavern like so many others I’ve been to – dark as a cellar, the smell of spirits and beer where men go seeking something they don’t have.

My eyes were beginning to blur. I had finished the peppers and plantains, two pints of ale and was making my way through a carafe of cheap rojo when I felt his presence. From across the room a man was looking at me, looking at me in the manner of a man looking at a woman he wants to bed. It wasn’t Sancho. I could feel his eyes and his gaze unnerved me, yet I met his eyes, man to man. My cheeks flushed, but I squared my shoulders and narrowed my eyes. My God, he picked up his glass and was walking toward me across the crowded room. Was this someone Sancho had sent in his place? He looked magnificent in his bleached white shirt, no stock, open at the neck revealing his Adam’s apple and the hollow beneath it. His well-cut breeches, flawless stockings, like he had just stepped out of the haberdasher’s shop.

And as if I had been struck by lightning, I recognized him. But how does one greet a former enemy and captor?

“Lieutenant Guyon. What a surprise, meeting you here,” I said coldly, though I felt a strange and warm excitement as he approached. I stood to greet him, wondering if I should bow first. He was taller than I remembered. More handsome. I found myself staring.

“Docteur.” The Frenchman bowed. “The pleasure is mine.”

My heart was knocking ridiculously in my chest and I felt the blood race up my neck. “You have keen eyes and a good memory to recognize me from across the room,” I said as dryly as I could manage.

He regarded me with frank knowing – as if we had been lovers. “I never forget a face.” His own face, so perfectly made, so composed. An enigmatic smile played on his lips and lit up his dark eyes.

What does one say to a former enemy – the man who boarded your vessel and took you captive? Yet, he had been ever the gentleman.

“How is your Captain’s health?” I had pulled Renwez’s offending tooth in exchange for our release.

Guyon shook his head and gave me a Frenchman’s dismissive shrug. “I am my own captain now. But if you’re referring to Renwez, I’ve not seen him since the war’s end. I’m told he has retired to a little cottage back in Bretagne. Raising cabbages. With one less tooth to give him pain, thanks to you.”

“And you, Lieutenant? Or shall I address you as Captain Guyon? Have you retired?”

“Au contraire. But the King of France doesn’t require my services at the present.”

“Do you work for Spain, then?” I goaded.

He smiled, his dark eyes dancing. “I work for my own gain. As do you, I would venture.”

“I would ask you to join me, but there seems to be a shortage of chairs.”

“Such an ill appointed little pot house. But I have a chair for you at my table. Will you do me the honor?”

“I do not intend to stay long,” I feigned. “I’m here on business matters.”

“Of course you are. We’re all here on business matters. Mon Dieu, this place is not known for its food! But since we are waiting for a certain someone, we might as well pass the time in good company. As I recall, we started a backgammon game in Martinique that was never finished.” His look was unmistakable. “Come, have a glass of wine and roll the dice with me while you wait for your contact.”

A flush of heat crept up my already warm neck. “I’m not a gaming man, Guyon.”

He looked at me and smiled, his eyes filled with my secret. “I believe you are quite adept at games. Le jeu, c’est tout, n’est ce pas?”

Against my better judgment I followed him across the room, weaving in and out between the tables filled with traders and fishermen, to his table where he poured me a glass of wine from an open bottle. French wine, not Madeira. “There, that’s better. It’s no good to drink alone. Now, let me guess, is it Sancho you’re waiting for? He’s always late. It’s unfortunate you have fallen in with him. Juan is much more trustworthy.”

Was I so transparent? Was I a fool?

“Do you always have an extra glass?”

“But of course. One never likes to drink alone.” He raised his glass and smiled warmly. “Once enemies, now friends?”

“Friends? On what basis? On whose authority?” I challenged, my insides beginning to go soft as butter in the churn.

“Fortune. It seems she has flung us together again.”

“For me, friendship is based on more than chance. Let me make one thing clear, Lieutenant: We are not friends. But I bear you no ill will and I will drink to your health.”

He smiled broadly, warmly, and raised his glass.

Touching his glass, hearing the little clink, I felt like I was entering deep water.

“Salut. To our health and to our mutual success. Money brings us all to Havana, does it not? The richest city in the hemisphere. Why the British returned it to the Spanish is quite beyond me. Ah, but you kept the cold Canadian provinces, didn’t you? That would not have been my choice. And you gave Nouvelle Orleans to the Spanish to weaken France even further.”

“It wasn’t my idea.”

He laughed. “Of course not. None of ever has a say in the treaties.” Then, leaning across the table as if to confide in me, he said. “I know a better place than this. Shall we?”

My heart nearly leaped from my chest. “I told you I’m waiting for someone. I have business to attend to.”

“Ah, yes. Sancho. Waiting for Sancho. Everyone is waiting for Sancho.” His eyes, dark-lashed and moist, were to be avoided. I looked past them, at his left ear, but I felt them like hands, caressing my face. “Sancho is not to be relied upon. He’s an opportunist, Doctor MacPherson.”

“Actually it’s Captain MacPherson. I am now master of the schooner Andromeda. The vessel you detained.”

“Captured, you mean to say.” His smile was unmistakably flirtatious. “So you are no longer a ship doctor? You no longer practice medicine?”

I had served as a surgeon’s mate in the navy but did not have a medical degree; in fact, though I was skilled as a ship surgeon, I had never sat for the exam. I was an imposter.

“I can still pull a tooth or dig out a bullet. Or remove a gangrenous limb, should the occasion arise.”

“Handy skills for a merchant captain to have.” He sipped his wine, regarding me the whole while. “I too, have advanced from my former rank. Now captain of my own vessel – a fine merchant brig. Like you, after the war I turned to trade. We have much in common, MacPherson. We’d made a good team.”

Now that he had my attention, Guyon prepared to take his leave. “The habaneros will be here shortly; I’ll leave you to your rendezvous. But you may find his terms less favorable than you would like. You’ve only just arrived. The rules of the game here have changed, you’ll find. In any case, perhaps I can be of some assistance.”

He pushed back his chair and I stood up, wondering whether to offer him my hand in the cordial Yankee fashion. He bowed courteously and I touched the corner of my hat in return.

“Speaking of games, we never finished that game of backgammon, Capitain. Later this evening, perhaps? Your vessel, Andromeda, such a lovely little schooner. To think, I let you go.”

Guyon left a doubloon on the table and walked out into the night. I sat there as if in a trance, staring after him.

*

Sancho showed up soon after and helped himself to the rest of Guyon’s bottle.; we quickly closed our deal over the rest of the bottle Guyon had paid for. He wanted everything we had, offering molasses, tobacco, and coffee in return; the only catch was, he did not have them ready. It would be a week, maybe two. For a price he could perhaps expedite the transaction. I didn’t like sitting around in a foreign port, and he knew it.

“There are many pleasures in Havana for you to take advantage of, while you’re waiting for the goods. If you’d like a woman, for instance? A nubile young girl?”

“I cannot afford to wait very long. Maybe we should call the deal off.”

Sancho smiled, showing his yellow teeth. “I wouldn’t, if I were you, Capitan. The officials would not look kindly on an English Colonial trading vessel. The woman, she’s complementary. My gift to you, to make your short delay –more bearable.”

“How long?”

He shrugged. “I will see what I can do.”

*

I gave Lovelace and the crew the night off. The men changed into their liberty clothes and gathered their personal articles to sell, then took the ship’s boat across the bay to Havana proper, which offered more prospects and excitement than sleepy little Rigel. I remained aboard, in the cockpit, enjoying the night air and my inebriated state. Havana wakes up when the sun goes down and the land breeze brings the smell of burning cane from inland. From the new fort, a cannon rumbles and the great chain guarding the entrance is winched up off the harbor floor.

A bumping alongside, a soft, Ahoy. I dropped him two lines – one to secure his jollyboat and one to climb aboard. Guyon scrambled nimbly up the side and onto Andromeda’s deck.

“I’ve come to tell you I’ve spoken with the harbor master. He will ignore you for a week.”

“I should thank you, I suppose. But what do I owe you for the favor of your influence?”

“Only that you entertain my proposition.”

“Your proposition?”

“Of an alliance. We would make a good pair, you and I.”

“You’re mad, Guyon,” I said, my heart knocking furiously in my chest.

He stepped closer, close enough to kiss me, I thought. And I realized I wanted that very much. “You’re quite right. You make me so.” His voice was low and strained with desire. But I could not believe it. I could not believe he could find me attractive. I was an abomination.

“That’s ridiculous,” I said, backing away. “Are you an unnatural man? Are you looking for a young boy to bugger?”

“Come now, Madame. I recognized you for a woman the first time we met. Remember our game of backgammon aboard my ship? We never finished.”

“I detest games.”

He smiled and gestured in a French-like fashion. “All of this is a game, my dear. Life is a game. Best to have a good partner. Someone who knows your mind and can back your play. Someone to throw your lot in with, win or lose.”

Guyon was one of the very few who knew me for the woman I was, he sensed it almost immediately. Yet he had not tried to take advantage of me, for those hours I was his captive, nor had he exposed me. The fact that he was a Frenchman, a former enemy, bothered me not in the least. What held me back was much more complicated. Still, the desire was there, an enormous and powerful presence that would occupy my thoughts and dreams in the hot days and sultry nights to come.

He lifted his hat, gave me a courtly bow. “I respect your independence, as well as your disguise, Captain. But do allow me to be of service to you and to enjoy the pleasure of your company for a few evenings. Allow me to show you Havana and her many charms.” With that he disappeared over the gunwale, untying the painter and casting off in his boat, leaving me wanting him.

*

Havana wakes up when the sun goes down and the land breeze brings the smell of burning cane from inland. From the new fort, a cannon rumbles and the great chain guarding the entrance is winched up off the harbor floor.

The next few evenings Guyon showed me Havana, the Havana he had come to know. The old Spanish stronghold and the newly rebuilt, emerging city – all of it was new to me. Even though I had been among the victorious besiegers, I had never set foot in the great old city proper. All I had known of it were the jungles of the heights where Dudley Freeman and I, as Richmond’s surgeon’s mates, had been sent to operate a field hospital. More of our men died from tropical fevers and fluxes than from battle wounds. I had fallen to disease myself and taken prisoner in the Moro. For us, Havana had been a hellhole. Now Guyon was showing me the opulence and opportunity of the city, once more a possession of Spain but no longer entirely Spanish.

The Havana he showed me was a city of churches, convents and elegantly aloof palacios, built in the Moorish style. The soldiers, the tradesmen, the engineers, and the servants who were rebuilding the fort and the city mingled in the cobblestone streets and plazas, Havana’s public places. We moved among them, Guyon and I, to El Arsenal, the shipyard, where a dozen vessels were under construction. The smell of sawdust hung on the thick, sweet evening air. Havana had been building ships for nearly two centuries. “This one,” Guyon said, stopping in front of a massive frame on blocks, “is to be the largest ship of the line ever constructed – over two hundred feet long. Designed by the Irish naval architect Mullan. Mateo Mullan, an Irishman in the service of King Charles. Built of mahogany from the forests – forests being cleared for sugar cane.”

Mullan wasn’t the only wild goose working for Spain, my companion assured me. Alejandro O’Reilly had left Ireland to fight for Spain in the last war, rising in the ranks to become major general. Now that England had returned our prize, Havana, as part of the peace treaty, King Charles III sent the Irishmen to oversee the rebuilding of the city and forts.

Havana was a gold pot of opportunists, attracted to a free port, bringing all sorts of goods for a tidy profit. Captive Africans were being shipped in and sold at the slave market. We walked among them now, finishing their long day’s work under the watchful eye and whip of the overseer.

It was very late when we supped, nearly midnight, at a tavern near the water’s edge. We quenched our thirst with small beer, brewed on site from New England barley. It was then he popped the question. “Will you accompany me to the Lieutenant Governor’s palace tomorrow night? There are some men I’d like to acquaint you with.”

“Really, Guyon, I think you’ve confused me with someone important. I’m a Yankee merchant who, at the moment, is sitting fully laden in a forbidden port, waiting for a disreputable factor to deliver the goods.” I found myself returning his smile. “I’m a freebooter of no consequence.”

“Precisely.” Now the smile was gone. He leaned forward, resting his hands on the tabletop. “What I have in mind for you – for us – is much bigger than Sancho. I am well-connected with the men who operate the new Havana.”

Why would he want to include me, I wondered? What could I possibly offer? If he wanted a woman – or a man – he could get one, God knows. I’m sure he has no difficulty finding someone to share his bed. Surely there were any number of wealthy creoles with beautiful, well endowed daughters. Lively widows with fortunes aplenty.

“Bien.” The smile returned and he reached for his glass. “I will come for you at sunset.”

*

— from Yankee Moon; the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures

copyright 2016 Linda Collison

February 6, 2016

Yankee Moon — Chapter 3

Yankee Moon; Book 3 of Patricia MacPherson’s Nautical Adventures

Chapter Three (working draft)

Christiansted, St. Croix

November, 1765

The wind, barely a whisper, teased us, flirting with the sails and making us work the sheets to keep them filled. Everyone was on deck and I at the tiller, coaxing the crippled rudder as we ghosted into the outer reaches of Christiansted harbor, anchoring on the lee of Protestant Island. Launching the ship’s boat, George and Moses towed the schooner to back down and set the anchor in the rich black mud. Stripped of their shirts, they strained at the oars, their bodies glistening with sweat. Lord, it was hot.

I breathed easier now that we were at anchor, safe for the moment in this shallow, sheltered bay. With any luck we’d quickly fix our rudder – or make a new one – and be on our way before incurring too many fees. That is to say, Moses, our carpenter would make a new rudder; he worked as a shipwright at the Redbone yard. Meanwhile, I would check in with the Danish port officials and explain that we were just here for emergency repairs and not to trade. Then I would look up my old friend Rachel. The last I had heard from her she was leaving Nevis for St. Croix with her adventurer, whose two children she had born. It was Rachel who had discovered me washed up on the beach outside her home after the British hospital ship I was serving hit the reef and went down. It was Rachel who helped me carry off my new identity, and it was the absent Mr. Hamilton’s clothes I borrowed for the purpose. I never returned them. If I should find her here in Christiansted I would compensate her, for the clothes, along with her care and coaching, had got me back on my feet.

Dressed in my best going ashore attire, I climbed down into the boat and cast off, leaving the vessel in Mr. Lovelace’s care, rowing for the wharf in front of the yellow bricked Customs House, dazzling in the hot afternoon sunlight. Approaching shore, my spirits rose unaccountably, as if I were discovering a new and wonderful land. Every time I make landfall, I have this secret expectation. Maybe this time I’ve come back, found my real home, the place where all know me and accept me, the neglected house that I can re-inhabit, re-kindling the logs in the long cold hearth. Or would this be just another ravaged, plundered sugar isle? I was a child of sugar, my own father had been a Barbadian plantation owner, my mother, his Irish maid. When she died he sent me back to England to be raised by strangers where I was more or less forgotten. The profits of sugar sustained me now. I bought and sold the sweet gold, worse yet, foreign grown sugar. I made a profit trading with our former enemies, the French, the Spanish, the Dutch.

Slavery is not a sweet word, yet the Christian Bible does not forbid it and neither do the laws of this land. But these same men say that woman is the weaker vessel and that we are lesser beings than men, that we are incapable of rational thought –yet look at me, doing a man’s work. If they knew they would likely revile me. Maybe I should become a Quaker. Would they, who abhor slavery and war, accept me as I am? A woman in man’s attire? A woman making her way in this world as a man?

Almost to shore now, the breeze has died. I drop the little sail and pick up the oars, rowing the rest of the way, perspiration trickling down my back and pooling under my breasts, hidden beneath chemise and waistcoat. The crushing heat, the hard sparkle of sunlight on water drive all musings from my head. Must approach the authorities, find a cool tavern and slake my thirst before looking for Rachel.

After two weeks in a rough sea, walking on terra firma made my head swirl and my ears roared with the sound of the wind and the sea. I walked with the peculiar lurching gait common to seamen who become accustomed to walking across a constantly shifting deck. Land sickness, we called it – very much like sea sickness – and this too, shall pass.

The fort, customs house and warehouse all built of Danish yellow brick, brought in ballast, to this island, an island they purchased from the French. Everything is available at a price, the entire world is being discovered, conquered, plundered, settled, sold. Every time I stepped foot on land after being at sea, I had the same feeling of wonder, of homecoming. Here the streets are laid out wide and straight, covered with a thick layer of crushed coral and limestone. Not a thatched roof to be seen along the water front, all very tidy, very prosperous. Looking around like Robinson Crusoe washed up on a new shore, I tramped, making my way to the Customs House, ship’s papers tucked under my arm, weaving my way through a throng of hucksters, fishmongers, errant boys and militia men, stepping aside for the black men rolling hogsheads of molasses to the docks. A chatter of patois I couldn’t understand; the blend of French, English, Danish, and a dozen African tongues sounded like a great flock of starlings. Children of all shades of black, brown, and tan, chasing chickens and herding goats through the streets, hitting them with green sticks, shrieking at them like lieutenants. Women with dark, shiny, imperturbable faces glided along carrying baskets of laundry to the beach to be bleached in the sun. Barefoot beneath their brightly colored skirts, yet imperious as Bantu queens. I felt a sudden and inexplicable longing for my childhood home on Barbados.

Presenting my papers to the Danish official, I explained as best I could about the broken rudder, and was granted permission to stay long enough to make repairs. I then quenched my thirst at a nearby tavern where I obtained an address for the Hamilton family. Now I walked along Company Street, looking for the tile marked 34. And there it was, with a prim little sign hanging above the door. Faucette Dry Goods. Would she recognize me? Expectantly, I entered the shop, the bell on the door ringing as I opened it.

“Hallo?”

“Good afternoon, sir. May I help you?”

I couldn’t see her – my eyes had not yet adjusted to the dark interior – but her voice I remembered well. The French creole accent, the musical inflection. Her voice reminded me of a woodwind instrument, distinctively mellow as an haut bois.

“Rachel.” Her name burst from my mouth.

She moved from behind the counter in a rustle of taffeta. I smelled her before I could clearly see her face.

“Have we been introduced? Tell me sir, what is your name?”

“Ah, what good are surnames, Madame? They are never our own.”

Yes, it was Rachel, and I had clearly caught her off guard. “T’was what I replied when you first asked me my name on Nevis after you rescued me, a castaway, on the beach. Took me in and nourished me. Dressed me in your husband’s clothes.”

Another brief silence as she came from behind the counter and stood directly before me. “Patricia? Is it really you?”

A great guffaw escaped me. “Yes. But please, call me Patrick. It was you who helped me become Patrick. Patrick MacPherson.” I removed my hat and made a flourishing little bow. “I kept my late husband Aeneas’s name.”

Her hand, a white tern, fluttered to her décolletage. Her lovely décolletage. “What joy! Can it be?” She approached me, her dark eyes wide, taking me in, enveloping me in a sisterly embrace. We both laughed, tears in our eyes.

“Let me look at you.” She held me at arm’s length to examine me, her dark eyes bright with curiosity and concern, then drew me close again, more fiercely this time. “Oh, Patricia.” I could feel her heart beating against my own and her own particular scent enveloped me. I had forgotten how she smelled but now remembered but cannot adequately describe it. Warm milk and irises, the oil from her hair, hair gone silver at the temples.

“But what brings you here to Christiansted? Why didn’t you write and tell me you were coming? And how do you fare? How does a man’s life suit you?” Her lilting voice, her laugh, bright as the tinkling bell over the door, lit up her face – a face beginning to show its age by the fine lines at the corners of her dark eyes and around her mouth, like delicate parentheses. An exquisitely expressive face.

“You are as beautiful as ever, Rachel.”

“And you, sir, are…” She held me at arm’s length to study me. “You are absolutely original.”

I laughed but found myself close to tears.

“Pray tell me, what brings you here? I cannot believe my good fortune.”

“I’m a shipmaster, can you believe it? Part owner of a small trading vessel out of Newport, Rhode Island.” It all sounded quite unbelievable as I spoke it aloud.

“A shipmaster? I thought you were a medical man. A ship surgeon.”

“Ah, but there was little profit in bleeding and cupping. Fewer bones to be sawed, with the war over and the treaty signed. Newport is filled with medical men, besides. Filled with merchants too. The trading business is profitable, Rachel. Risky but profitable. And you –you are minding Mr. Hamilton’s store?”

Her face clouded, the furrow between her eyes deepened, then vanished in a proud smile. “This is my store. My own business. I will tell you the details over supper, and you must relate your adventures. You will stay for supper, won’t you?”

“I’d like nothing better, but I must see to my vessel. We’ve damaged our rudder and stopped here just to repair it.” Oh, but I wanted to stay for supper. I missed female companionship – Rachel’s in particular. She and I had developed a close rapport during those weeks I stayed under her roof.

“Go see to your ship, Captain MacPherson, of course.” She grasped both of my raw, red hands in hers, squeezing them. “But do come back and join us. If I can be of any help, if you need any materials at cost, do let me know. I have connections with the chandler. Oh, Alexander will be so pleased to see you again, and you’ll meet James who was with his father when you stayed with me on Nevis. We have so much to catch up on, so much to say to one another. Please do say you’ll sup with us, and stay the night.”

The bell above the door tinkled as a customer entered – an older gentleman who greeted her in accented English. Tipping my hat, I bid Rachel a good afternoon, and stepped out into the street, squinting against the late afternoon sunlight. Back to my ship where Moses was at work making a new rudder with a slab of oak we had aboard. He was confident it would be finished in a few days’ time.

*

I went back to Rachel’s at dusk, bringing with me two gifts – a small cask of stone-ground Rhode Island flint corn and a pamphlet of essays from the Goddard’s print shop. The smell of pepperpot wafted from the apartment overtop the store.

Close around the table we sat, the heat, the spices, and the warm red wine flushing our faces. My head swam pleasantly, I could hear the waves lapping against my ears as if I were still at sea. Toying with a piece of gristle left in my bowl, I listened to Alexander and James recite their lessons, at their mother’s insistence. She was eager to show me what good students they were.

“James starts his apprenticeship in a few weeks. He’s to learn carpentry.”

“An excellent trade, James. I have a great respect for woodworkers, ashore or at sea. Andromeda’s carpenter is making us a new rudder, to replace the one that broke during the storm.”

The boys were eager to hear a death-defying tale, yet what was there to say? It had been exciting, yes. But also monotonous. Miserable. Exhausting. But I couldn’t disappoint them, so I told them the story they wanted to hear, a story of man against nature – and man winning.

“What do you carry in your ship?” Alexander asked.

“Whatever we can fill our hold with. This voyage we have corn meal, cobblestones, candlesticks, and Rhode Island rum.”

“Rum to the Caribee? Isn’t that like shipping coals to New Castle, Mr. MacPherson?”

I smiled. “It would seem so. But Rhode Island makes very good rum. And Spain is rebuilding her forts – rebuilding the city of Havana itself. They don’t grow enough cane in Cuba yet, to meet the need, though that is changing with all the Africans the English are bringing in for labor. But right now all of the engineers, the soldiers, the artisans, they’re thirsty for our good Newport rum. It fetches a high price in Havana right now, but the opportunity won’t last forever. The world is changing rapidly.”

“Perhaps,” Rachel said, with a wry little smile. “But not fast enough for me.”

After eating, Rachel and I left the boys to their reading and went for a walk about town. The land breeze was welcome, after the heat of the day.

“Walking is good for the digestion.”

“Spoken like a true man of medicine,” she teased, pushing back her chair. “Ah, but now you’re a shipmaster, not a ship surgeon.”

“I am an opportunist, madam. That’s what I am. And you? You’re a woman of business. And a mother of sons.”

“I’m an opportunist as well, Patricia. We’re adventurers, you and I. I trust your luck has been better than mine.”

Now, away from her sons, the cheerful mask dropped away, the lilting voice flattened. I tried to lift her spirits, to make her smile. “What will people thing, a strange man come to dinner, then strolling the waterfront with you, with your husband gone?”

She laughed, but it was a hollow sound. “People think the worst of me as it is. My name is ruined, I have nothing to lose. My only goal in life is to make a better life for James and Alexander.”

“Every mother’s goal, I’m sure. But what of Mr. Hamilton?”

“It appears he has sailed out of our lives forever.”

“What? But you were to be married, here on St. Croix. When I saw you last on Nevis, you told me yourself.”

“I hoped so, but when we arrived, the Danes, and the church, forbade it. Mr. Lavien remarried, yet I was denied the right to remarry. Oh, it wouldn’t have suited Mr. Hamilton anyway. Not to mention, he’s lost what money I gave him from my little inheritance. Lost it all in bad schemes. He has neither the head nor the luck for speculating – and too much pride to admit defeat. He’s a wanderer.”

“But to leave his family –

“We manage well enough.” There was a hint of pride in her voice.

Three seamen stumbled down the street, exuberant in their liquor and oblivious to our presence. Out in the harbor a hundred lanterns glowed, their light dancing on the dark water. An orchestra of blocks tapped and hemp rope slapped against masts in the night breeze sliding down from the hills. The sound, heard in every port I’ve ever been to, made me restless to leave.

Ahead, the stone fort. A sentry leaned against the wall, waiting for his watch to be over. Rached stopped.

“Years ago I was jailed there, for adultery. Lavien branded me a harlot.” Her mouth twisted into an ugly smile. “But I’ve told you all this before, back on Nevis. My reputation is ruined – except as a merchant. The men of Christiansted do business with me. One man in particular whom I count as my particular friend.”

The night land breeze felt refreshing to me but my friend shivered and pulled the light muslin wrap draped around her shoulders closer, grasping it in both hands. I put my arm around her and drew her close, knowing it wasn’t just the cool night air that caused her to tremble. She stiffened, shaking her head. Rachel wasn’t seeking my comfort, rather she was unburdening herself. It was a sensitive and sympathetic ear she needed, more than a strong arm.

“For three months I was held there, behind bars. And the guards, they have their way with women said to be whores. They bound and gagged me so no one could hear my rage against them.”

I had heard her story before when we first me, but I listened again as she relived it again.

“It was then Lavien took Peter from me. Peter, my first born, and Lavien’s own. He poisoned his mind against me.”

“Is there no hope of reconciliation?”

Her thin nostrils flared. “Peter is lost to me, I fear. Only in the next world might I know his love and he, mine. But in this world I still have James and Alexander’s welfare to consider.”

“Mr. Hamilton’s children.”

I felt her bristle and realized my gaff. It sounded like I was questioning their parentage. “I didn’t mean to imply –I just meant, well, does he not support his own offspring?”

“Mr. Hamilton claims them as his own, yes, but he’s not a dependable means of support. He never has been. James isn’t a bad man, he’s just…” She sighed. “Ineffectual. He was never a provider. A schemer and a dreamer. Still, he took me in and protected me when I fled from Lavien and I shall always be grateful to him for that.”

“But the store you manage? Is it not profitable?”

“The store is my own venture.” I thought I heard a note of pride. “A friend, Mr. Stevenson, loaned me the capital. My sister’s brother pays for my lodging – at least, for the time being. And yes, the store keeps us fed. But I want a better life for my sons. James starts his apprenticeship soon. Next year Alexander will apprentice as a clerk with Mr. Stevenson. The boy had a quick mind, he’s good with figures, have you noticed? He is very close to the Stevenson lad – the two are fast friends. As close as brothers. In fact, Mr. Stevenson thinks of Alexander as his own.” She gave me a quick look, freighted with meaning but I dared not pursue her insinuation.

“Which one is your ship, Patricia?”

“She’s way out there, just to the right of the island. A schooner. My Andromeda.

“I see her, yes. She looks rather small from here.”

I felt a blooming of pride in my chest, like a parent might feel for a child. “Oh, she’s a very stout vessel, very weatherly. And because of her size we don’t require a large number of men to manage her, leaving most of the available space for goods. Which is profitable. As a woman of affairs yourself, you can appreciate the advantage.”

It was good to feel her shoulders soften, and to hear her laugh in agreement.

“Can you stay, Patricia? A fortnight? ”

“No, I must sail as soon as the rudder is repaired. Every day sitting in a harbor is costly and cuts into the profits.”

“Profits, I understand. But I hope you’ll come back some day.”

“If only we could do business, you and I…But I’m afraid the Danish duties are prohibitive.

“There are ways around that.”

That, I well knew for my living depended upon it.

We walked along the waterfront, hand in hand. The docks were mostly quiet now; those that had come ashore for the evening were ensconced in the taverns and pot houses, leaving just a few low women as there are in any port town looking to make a krone, a peso de ocho, or whatever bit of currency she could get.

“Tell me, my dear Patricia, how is it, being a man? I’ve often wondered.”

A laugh burst from me and I squeezed her hand in mine. “It’s very much to my advantage, I must say.”

“Always?”

“Most always. It can be lonely.” My chest swelled, my throat thickened with feelings seeking release. Being here with her, not having to pretend, not having to prove myself, made me realize how lonely I was.

A three-legged beagle hobbled across the street in front of us; a bitch dog, heavy with milk. We paused as she passed, limping down a dark passageway.

“And is it to your liking?”

I shrugged. “Mostly. Being a man has its advantages.”

“Yes, but don’t you ever tire of it? The pretense? The burden? Don’t you ever just want to be yourself?”

The breeze from the hills enveloped us. After the stultifying heat of the day, it made me shiver.

“I am myself, Rachel. This is who I am.” I turned to face her, holding my arms open as if to say, behold. She slipped her arms around my waist and pulled me close.

“You are strong and proud but you’re not content. I sense your loneliness. Is there anyone who knows your secret? Is there anyone who knows you and loves you?”

“There was one man. A man I served with aboard the frigate Richmond. He loved me, and I him.”

“Was is a sad word. Past, gone,” she murmured.

“Will you write me, Patricia?”

“I will,” I said. “If you will answer.” I buried my face in her hair, glad for the darkness, glad for her arms around me.

— from Yankee Moon copyright 2016 Linda Collison

February 1, 2016

Yankee Moon — Chapter 2

Yankee Moon is a a work in progress. Told as a memoir, the book is from the viewpoint of 20 year old Patricia, who has taken a dead man’s identity and lives as Patrick MacPherson. It takes place in Rhode Island, St. Croix, Havana — and aboard a merchant schooner at sea in 1765. Comments, questions and suggestions are appreciated!

Chapter 2 — The passage

A voyage to the West Indies from Newport this late in the year was always a gamble, yet for the moment luck seemed to be on our side. We sailed out of Narragansett Bay on a broad reach, the October air crisp and tart as a crab apple. I pulled my cap down low on my brow, squinting into the rising sun. Visibility was good – but a herd of wispy mares’ tails high overhead foretold of a blow to follow.

Andromeda was not a large vessel but she was efficiently constructed and could carry a good deal of cargo when properly loaded, and didn’t require a large crew to sail. She was a tops’l schooner – sixty-five feet on deck, nineteen feet wide at her beam, and drawing seven feet of water. I had come to call her home and took tremendous pride in her.

On the foredeck the two watermen stowed the anchor line, washing away the Narragansett mud with buckets of seawater as they flaked the hemp rope neatly into the foredeck. George, whose face seemed permanently twisted into a disfiguring scowl, as if scarred from birth, was younger than he appeared. Twenty years old, he had been working on local coasters and fishing boats since he was a lad of ten. The other one – a young African, property of Dominic Hale by way of his wife – worked with an unreadable expression. His flaring nostrils indicated either determination or suppressed anger, I couldn’t be sure. Hatless, he wore his hair long, plated into a queue and made slick with grease; a scrap of faded red cloth tied around his forehead, Indian-fashion, kept the perspiration out of his eyes. He was called Moses, a name given to him by the Redbones, upon acquiring him as a boy, from Guinea. He seldom spoke, but when he did his English was understandable.

Beside me, the blue-eyed Mr. Lovelace looked very much at ease with his hand lightly on the tiller, his feet comfortably apart, rocking with the boat’s motion, as effortless as breathing. Like he had learned to sail when he had learned to walk. Below, in the galley, Sam was singing as he prepared a sea pie for our midday meal, his rich voice carried up on the bones of the vessel and into the wind. What was it, a song from his homeland? I could not make out the words.

Who were these men, my crew? I trusted them because Dominic did. Did they trust me for the same reason?