Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 90

May 28, 2025

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: Bruen Was Right

[Joel Alicea’s defense of originalism demonstrates broad applicability of the text-history method.]

J. Joel Alicea, "Bruen Was Right," 174 U. Pa. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2025), sets forth a comprehensive defense of the text-history approach and rejection of means-scrutiny set forth in Justice Clarance Thomas' opinion in Bruen. A professor at the Columbus School of Law, Alicea is the director of the Center for the Constitution and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition.

Some scholars argue that Bruen was a mistake. An exception Alicea cites is William Baude & Robert Leider, "The General-Law Right to Bear Arms," 99 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1465 (2024). My own humble defense of Bruen is set forth in "Text and History, Means-Ends Scrutiny, and the Second Amendment," 24 Fed. Soc. Rev. 54 (2023). Alicea's article deserves a deep read about which I can only skim the surface here.

As Alicea explains, the larger significance of Bruen "is in its rejection of tests like strict or intermediate scrutiny that have loomed large in rights jurisprudence since the 1960s. In their place, Bruen substituted a text-and-history-based test for evaluating the constitutionality of arms regulations that, if successful in the Second Amendment domain, holds out the prospect of displacing the tiers of scrutiny and other judicial balancing tests elsewhere in constitutional law." But if this "most thoroughgoing attempt by the Court to do originalism in the area of constitutional rights" fails, "it calls into question originalism's capacity to transition from a critical posture to a governing one, at least in the rights space."

Before outlining the article, I'll mention two cases citing Alicea about which readers may already be familiar. In NRA v. Bondi (11th Cir. 2025) (en banc), Chief Judge William Pryor sought to justify Florida's law subjecting persons aged 18 to 20 to imprisonment for purchase of a firearm based on this supposed analogue: "Founding-era law precluded individuals under the age of 21 from purchasing arms because they lacked cash and the capacity to contract."

But Alicea added to the above quote: "That being said, … I have not come across evidence of a principle that was generally held to be part of the Second Amendment right but that failed to make its way into some form of positive law." In fact, neither the common law nor Founding-era statutory law made it a crime for a minor to buy a firearm, and indeed the Militia Act of 1792 required every male citizen 18 and over to "provide himself with a good musket or firelock." By relying on civil laws involving the capacity to contract, Chief Judge Pryor "view[ed] a tradition at too high a level of generality," as Alicea would say. Bruen's Footnote 11 cautions against this type of reasoning when it said "[t]o the extent there are multiple plausible interpretations of [the scope of our Second Amendment rights], we will favor the one that is more consistent with the Second Amendment's command."

Alicea was more appropriately cited by Judge Ryan Nelson, dissenting in Duncan v. Bonta (9th Cir. 2025). As I explained in a post, the majority upheld California's ban on possession of a magazine holding over ten rounds on the basis that a magazine is a mere "accessory," not an "arm" under the Second Amendment's text, and that plaintiffs had not shown that such magazines are in "common use" under Bruen's Step One, the textual analysis. But as Judge Nelson cites Alicea as clarifying, "Conducting the common-use inquiry at the first step 'would be at odds with the fact that the common-use test is not about the semantic meaning of the Second Amendment's plain text.'"

That's a good lead in to Alicea's analysis of Bruen's Step One, the textual analysis, which first asks whether the persons are part of "the people," whether handguns (or magazines, in Duncan) are "arms," and whether carrying handguns for self-defense in public constitutes "bearing arms." Second, Bruen assumes that Heller conducted all of the historical work at Step One. Third, Step One covers whether the Second Amendment is implicated (similar to asking whether "speech" is being regulated under the First Amendment). And fourth, if successful under Step One, the burden shifts to the government to prove the constitutionality of the restriction.

A consequence of the above is that, "if the common-use test applies at Step Two, the government would have the burden of proving that an arm is not in common use, rather than the burden being on the challenger to prove that an arm is in common use." This becomes clearer under Bruen's analysis of the operative clause. "At Step One, it does not matter whether the person in question is a law-abiding citizen or a felon, whether the object in question is a handgun or a machine gun, or whether the conduct in question involves bearing an arm for self-defense or bearing an arm to commit a crime." One must go to Step Two to determine if there is a historical tradition of banning violent persons from gun possession, of prohibiting dangerous and unusual weapons, and of carrying arms for criminal purposes.

That leads to Step Two, the historical analysis, in which courts reason analogically to compare a modern restriction with the historical tradition of firearm regulation. This inquiry is originalist, but does not require the same historical law to justify the modern law, as long as consistent with the same principles. A good example of a historically-justified sensitive place is on board a commercial aircraft.

"Bruen's key move is to relocate who determines the appropriate means and end, largely taking this task away from judges and giving it back to the ratifiers." By contrast, under tiers of scrutiny, judges decide whether the state's interest is compelling and, for narrow tailoring, whether the means are proportional to the ends.

Alicea categorizes three principal criticisms of Bruen at Step Two. First is the Fallacy from Absence. Where there is historical silence, why should the state bear the burden to justify a restriction? For one thing, "putting the burden on the rights-claimant at Step Two would be asking the rights-claimant to prove a negative: that there was no historical limit on the right the claimant asserts." Moreover, the Second Amendment codifies a preexisting right, creating the presumption that the covered conduct is protected. Additionally, this is how other constitutional rights like speech are treated. "The difference is that Bruen—true to its originalist premises—requires historical support to overcome the presumption of unconstitutionality, whereas the tiers of scrutiny allow judicial moral and policy judgments to overcome the presumption."

Second is the Level-of-Generality Problem. This is presented in the "why" and the "how" of a historical tradition. In Rahimi, the majority decided that the surety and affray laws sufficed as analogues, while Justice Thomas in dissent thought they were at too high a level of generality.

Alicea distinguishes "substantive" from "incidental" features of the history, the former being the contours of the right understood at the Founding and the latter being facts that were not germane to those contours (e.g., that the supposed analogue and the modern law were both passed on a Tuesday). Whether an arm is dangerous and unusual or in common use is informed by the historical purposes of the right, including to enable citizens to bring arms kept at home for militia duty. "Thus, just as it is an error to incorporate incidental features into our description of a historical tradition, it is a mistake to efface substantive features in our description. The former occurs by viewing a tradition at too low a level of generality, while the latter occurs by viewing a tradition at too high a level of generality."

Third is the Administrability Problem. Some complain that the text-history approach is too difficult to administer, despite that that's what judges and lawyers typically do – they analyze the words of the Constitution and the original understanding thereof. Alicea suggests that it's too soon after Bruen was decided to make sweeping judgments about the precedent's viability. Some issues don't have a clear answer, such as the number of laws that make a tradition, but that's the case with other tests as well. As the Court resolves more cases under Bruen, uncertainty will diminish. Not to mention that "ideologically-divergent judging in highly controversial cases is not a phenomenon unique to Bruen."

Finally, Alicea analyzes Bruen's rival, tiers of scrutiny. First, without Bruen's historical approach, courts decide for themselves whether an interest is compelling. "But where does the positive law grant judges the authority to answer such political questions in the realm of constitutional adjudication, and when did the people decide to allocate that authority to judges?" Judges are able to manipulate outcomes by how they frame the questions.

Second, the same problem arises when judges determine whether a regulation is sufficiently tailored to achieve a government interest. Recall Justice Breyer's quip in McDonald v. Chicago about how judges must resolve complex empirical issues. Once again, judges shouldn't determine public policy.

And third, use of tiers of scrutiny allows judges to do the balancing. By contrast, Step One invokes the presumption of protection for conduct within the Second Amendment's original semantic meaning, and Step Two allows only restrictions with proper historical analogues. "It adds insult to injury for judges to first create a new legal standard without basis in democratically enacted positive law and craft a standard that grants broad authority to themselves to 'usurp[] the people's right to make major policy choices.'" (Quoting Justice Kavanaugh's Rahimi concurrence.)

Alicea concludes that if critics are right that Bruen is incoherent and manipulable, its failure will reinforce tiers of scrutiny in other areas of constitutional adjudication, reverting to the kind of judge-empowering interest-balancing inquiry that originated with the Warren Court. "The alternative future is one in which Bruen marks the end of one era of constitutional law and the advent of another, one in which history-based methodologies increasingly displace those created before the rise of modern originalism."

* * *

The Court has now relisted two Second Amendment cases fifteen times, in this instance for its conference on Friday May 29. They include Ocean State Tactical v. Rhode Island, which concerns Rhode Island's magazine ban, and v. Brown, which concerns Maryland's ban on semiautomatic rifles.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: Bruen Was Right appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] We Won Our Tariff Case!

[The Court of International Trade just issued a decision striking down Trump's "Liberation Day" tariffs and other IEEPA tariffs.]

The US Court of International Trade just issued a unanimous ruling in the case against Trump's "liberation day" tariffs filed by Liberty Justice Center and myself on behalf of five US businesses harmed by the tariffs. The ruling also covers the case filed by twelve states led by Oregon; they, too, have prevailed on all counts. All of Trump's tariffs adopted under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) are invalidated as beyond the scope of executive power, and their implementation blocked by a permanent injunction. In addition to striking down the "Liberation Day" tariffs challenged in our case (what the opinion refers to as the "Worldwide and Retaliatory Tariffs"), the court also ruled against the fentanyl-related tariffs imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China (which were challenged in the Oregon case; the court calls them the "Trafficking Tariffs"). See here for the court's opinion.

(NA)

(NA) It is worth noting that the panel include judges appointed by both Republican and Democratic presidents, including one (Judge Reif) appointed by Trump, one appointed by Reagan (Judge Restani), and one by Obama (Judge Katzmann).

Here is the court's summary of its ruling, from its per curiam opinion (issued in the name of all three judges together):

The Constitution assigns Congress the exclusive powers to "lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises," and to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations." U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cls. 1, 3. The question in the two cases before the court is whether the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 ("IEEPA") delegates these powers to the President in the form of authority to impose unlimited tariffs on goods from nearly every country he court does not read IEEPA to confer such unbounded authority and sets aside the challenged tariffs imposed thereunder.

From the very beginning, I have contended that the virtually limitless nature of the authority claimed by Trump is a key reason why courts must strike down the tariffs. See, e.g., my Lawfare article, "The Constitutional Case Against Trump's Trade War." I am glad to see the CIT judges agreed with our argument on this point!

The court elaborated further on the statutory point:

Underlying the issues in this case is the notion that "the powers properly belonging to oneof the departments ought not to be directly and completely administered by either of the other departments." Federalist No. 48 (James Madison). Because of the Constitution's express allocation of the tariff power to Congress, see U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 1, we do not read IEEPA to delegate an unbounded tariff authority to the President. We instead read IEEPA's provisions to impose meaningful limits on any such authority it confers. Two are relevant here. First, § 1702's delegation of a power to "regulate . . . importation," read in light of its legislative history and Congress's enactment of more narrow, non-emergency legislation, at the very least does not authorize the President to impose unbounded tariffs. The Worldwide and Retaliatory Tariffs lack any identifiable limits and thus fall outside the scope of § 1702.

Second, IEEPA's limited authorities may be exercised only to "deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat with respect to which a national emergency has been declared . . . and may not be exercised for any other purpose." 50 U.S.C. § 1701(b) (emphasis added). As the Trafficking Tariffs do not meet that condition, they fall outside the scope of § 1701.

It also ruled that an unlimited delegation of tariff authority would be unconstitutional:

The Constitution provides that "[a]ll legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States." U.S. Const. art. 1, § 1. Congress is empowered "[t]o make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution" its general powers. Id. § 8, cl. 18. The Constitution thus establishes a separation of powers between the legislative and executive branches that the Framers viewed as essential to the preservation of individual liberty. See, e.g., The Federalist No. 48 (James Madison). To maintain this separation of powers, "[t]he Congress manifestly is not permitted to abdicate or to transfer to others the essential legislative unctions with which it is thus vested." Pan. Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388, 421 (1935); see also Marshall Field & Co. v. Clark, 143 U.S. 649, 692 (1892).

The parties cite two doctrines—the nondelegation doctrine and the major questions

doctrine—that the judiciary has developed to ensure that the branches do not impermissibly abdicate their respective constitutionally vested powers. Under the nondelegation doctrine, Congress must "lay down by legislative act an intelligible principle to which the person or body authorized to fix such [tariff] rates is directed to conform." J.W. Hampton, Jr., 276 U.S. at 409 (1928); see also Pan. Refining, 293 U.S. at 429–30. A statute lays down an intelligible principle when it "meaningfully constrains" the President's authority. Touby v. United States, 500 U.S. 160, 166 (1991)… Under the major questions doctrine, when Congress delegates powers of "'vast economic and political significance,'" it must "speak clearly." Ala. Ass'n of Realtors v. HHS, 594 U.S. 758, 764 (2021) (quoting Util. Air Regul. Grp. v. EPA, 573 U.S. 302, 324 (2014))….The separation of powers is always relevant to delegations of power between the branches. Both the nondelegation and the major questions doctrines, even if not directly applied to strike down a statute as unconstitutional, provide useful tools for the court to interpret statutes so as to avoid constitutional problems. These tools indicate that an unlimited delegation of tariff authority would constitute an improper abdication of legislative power to another branch of government. Regardless of whether the court views the President's actions through the nondelegation doctrine, through the major questions doctrine, or simply with separation of powers in mind, any interpretation of IEEPA that delegates unlimited tariff authority is unconstitutional.

Nondelegation and major questions were crucial elements of our case against the tariffs, and I am happy to see they played a role in the decision.

The Court also rejected the government's claim that president has unreviewable authority to determine whether there is a "national emergency" and "unusual and extraordinary threat" justifying the invocation of IEEPA:

IEEPA requires more than just the fact of a presidential finding or declaration: "The authorities granted to the President by section 1702 of this title may only be exercised to deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat with respect to which a national emergency has been declared for purposes of this chapter and may not be exercised for any other purpose." 50 U.S.C. § 1701(b) (emphasis added). This language, importantly, does not commit the question of whether IEEPA authority "deal[s] with an unusual and extraordinary threat" to the President's judgment. It does not grant IEEPA authority to the President simply when he "finds" or "determines" that an unusual and extraordinary threat exists. Cf., e.g., Silfab Solar, 892 F.3d at 1349 (collecting cases involving "statute[s] authoriz[ing] a Presidential 'determination'"); United States v. George S. Bush & Co., 310 U.S. 371, 376–77 (1940).

Section 1701 is not a symbolic festoon; it is a "meaningful[] constrain[t] [on] the

President's discretion," United States v. Dhafir, 461 F.3d 211, 216 (2d Cir. 2006) (internal

quotation marks, alteration, and citation omitted). It sets out "the happening of the contingency on which [IEEPA powers] depend," and the court will give it its due effect. The Aurora, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 382, 386 (1813).

The court issued a permanent injunction against implementation of the various IEEPA tariffs. That means they are blocked with respect to all importers, not just the plaintiffs in the two cases.

There is more to the court's ruling, and I will have more to say soon. But the bottom line is a major victory in the legal battle against these harmful and illegal tariffs.

The post We Won Our Tariff Case! appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Setting the Wayback Machine to 1995: "Cheap Speech and What It Will Do": Music: The New System

[I thought it would be fun to serialize my 1995 Yale Law Journal article "Cheap Speech and What It Will Do," written for a symposium called "Emerging Media Technology and the First Amendment.) Thirty years later, I thought I'd serialize the piece here, to see what I may have gotten right—and what I got wrong.]

[1.] The new distribution technology will do more than just make music cheaper and easier to get. It will also radically change what music is available.

I've already mentioned one way this will happen: The music databases will provide access to albums that stores otherwise wouldn't stock. Even if there are 50,000 fans of a particular kind of music throughout the country, a music store might expect there to be only a handful of these people among its customers. It can't afford to use shelf space for material that so few people want. But electronic databases can carry even albums that appeal to only a tiny fraction of the market. The result will be more diversity for the listeners (even if not all of them take advantage of this diversity).

But electronic home distribution will do more than eliminate the bottleneck of music stores. It will also greatly reduce the power of the music production companies (the "labels").

Electronic distribution will drastically lower up-front costs. Even today an artist can make a commercially viable master recording relatively cheaply. With electronic distribution the cost will be even lower-once the master is made, there are no tangible copy production, distribution, or sales costs. An artist will no longer have to persuade a production company that his product is worth the investment. He'll be able to create it and submit it to the electronic databases himself; and once it's in the databases, the work will be as available as if it were in every music store in the country.

Many artists will probably still prefer that someone else pay for recording and editing the album, especially if they want a more-frills recording, and they'll probably like to have someone invest in advertising. Labels will thus still survive, and the artists will still have to persuade the labels that their works will sell enough to justify investment.

But the needed investment will be much less than it is today. Less money will have to be recouped for production expenses, so the labels will be more willing to back material that they think has a small audience. Even if no one is willing to invest, the artist could still pay for the recording himself, go without advertising, and hope it sells through word of mouth, good reviews, or radio play (especially through custom-mix radio, which I describe below). Advertising is better for the artist than no advertising; but no advertising on the infobahn is still better than the current system, where without a label an artist essentially can't make the music available to the public at all.

[2.] The great obstacle to consumers getting what they want will no longer be that there are too few products available; it will be that there are too many. The new system, by reducing barriers to entry, will make much more material accessible to consumers. Some of it will be good; most will be junk.

This, of course, isn't a new problem. Tens of thousands of books and CDs come out yearly. Most of us have had the experience of going to the store and not knowing what to choose. But we've made do, largely because the information overload has spawned professionals-reviewers, radio programmers, and decision makers at the record stores and the labels-who help us wade through the material. These people's job is to find what they think we'll like most, and tell us about it, play it for us so we can decide for ourselves, or try to sell it to us.

The new system will reduce the role of the record stores and the labels, but the other sources of information, such as reviewers, will remain. Rather than sending its work to production companies, hoping for a contract, a musical group will send it to reviewers. The reviewers will probably specialize in particular genres, and there will probably be quite a few of them, of varying reputations.

Some of these reviewers will, like music reviewers today, write for newspapers, magazines, and such. Other reviewers will select albums that they recommend and e-mail sample songs to their clients. The clients will then be able to listen to the songs at their leisure, and, if they like what they hear, buy the album (perhaps after first listening to it) at the touch of a few keys.

Still other reviewers will write brief reviews-perhaps even just give numerical ratings-for the music databases; they might also compare the music to other albums or artists. This will let database customers search for, say, "New Reggae that has gotten a thumbs up from at least two reviewers," or "Songs that someone who likes They Might Be Giants might enjoy." This class of reviewers will probably be paid by the music database operators.

Custom-Mix Cable Radio: The most valuable review service, though, should be something akin to cable radio today. The virtue of radio as a selection tool is that, because the play list is ultimately outside of your control, radio familiarizes you with material you didn't know about. This, of course, is also its vice. You have some ability to select what's played-you can listen to a given station or a given show. But the selection is limited. Even in a big radio market you might find that no station quite satisfies you.

What one would optimally want, I believe, is the ability to specify the radio mix more precisely, without sacrificing the element of the unexpected and new that radio can provide. One would like to be able to say, for instance: "I'd like a mix of '60's rock, rock ballads from all decades, bluegrass, songs recommended by a Rolling Stone reviewer, and songs that someone who likes the Talking Heads, Paul Simon, and Concrete Blonde might like. I'd also like a small part of the mix to be random rock. And no Steely Dan!" People would prefer this approach because it maximizes the chances that they'll like what they hear. One doesn't have to be particularly musically literate to know roughly what one enjoys, and to want to hear more of it.

It should be easy to get such a mix piped into your home. You could configure your preferences on your computer, and when you choose "home radio" mode, the computer would pick up a semi-random mix from the electronic databases and play it for you. Within the boundaries set by your preferences, the music would be selected based on the reviews stored in the databases.

Because you can pay for the music directly, you'll have the option of either a free service with commercials, or a paid service with no commercials. There's no reason to think the paid service would be very expensive, since there'll be no transmitter and FCC license to amortize, and since the copyright owners, interested in selling albums, will likely charge little for the rights. Cable radio is already available in some markets, though of course without the preference configuration system; it costs $5 to $10 per month.

You could also set up your computer to automatically store a mix every morning onto a DCC or a MiniDisc; then, you could take it into your car and play it all day in place of wireless radio. It might bother some to have to pop in a new cassette or disc every night and take it to the car every morning. Nonetheless, this extra effort shouldn't be prohibitive, especially since investing this effort could substantially increase listening pleasure.

{Getting the custom-mix radio sent directly to your car will probably be too expensive. Maybe some day using wireless private lines will be as cheap as using the fiber optics of the infobahn, but that day may be quite some time from now.}

If a reviewer has 10,000 subscribers—and recall that the market is nationwide—he can make a decent living charging them $5 to $10 a year, plus copyright clearance costs, for a custom-mix service based on his reviews. Even with 1000 subscribers, the reviewer can make some money for not very hard work. Alternatively, reviewers can accept advertising, or take money from people who want their material reviewed. Some people might not trust reviewers paid by the musicians, but subscribers will be able to choose among those reviewers paid by musicians, those paid by subscribers, and those funded by advertising.

Of course, like the other screening mechanisms, this will give some people-no longer the labels but now the reviewers-some power over what people will hear. A band that once complained, "Our music is brilliant but the producers are keeping it off the market," will instead say, "Our music is brilliant but the reviewers can't appreciate it."

The power of reviewers, though, is based on people's approval of their tastes. Maybe the people's trust is misplaced, but it's hard for artists to complain that the reviewers' power is illegitimate. Moreover, the reviewers' power is much less exclusionary than the power of the labels. If I don't like one reviewer's taste, I can easily switch to another. If reviewers are neglecting material that at least some listeners-even small groups of listeners-would like, other reviewers will step into the breach. And the low cost of providing reviews means even small markets should have quite a few reviewers serving them.

[3.] I mentioned above that electronic music databases will succeed because both copyright owners and consumers can benefit from them. But many sound recording copyrights are owned by the music production companies. If, as I suggest, production companies will be hurt by the new system, will they be willing to license copyrights to businesses that will likely displace them?

Production companies may well be reluctant to let the electronic music databases get off the ground; but it seems to me competitive pressures will ultimately force them to go along. The new system gives copyright owners a new way of exploiting markets they otherwise couldn't reach. Even if it will prove generally bad for labels in the long term, some small labels-which may have their sights set more on selling their existing stock rather than on the long run-will want to take advantage of it. Musicians signing new recording deals may want to take advantage of it, too, because the new system is definitely in their interest; if the musician has a good enough bargaining position, the label may have to participate even if it doesn't really want to.

Also, the fact that copyrights in musical works aren't truly exclusive may play a role. A musician can record a song without the composer's permission, so long as he pays a compulsory royalty (today, 6.6 cents per song per copy). Of course, people might still much prefer the Beatles' Let It Be to Volokh's Let It Be; but the fact that new covers of old standards constantly come out will weaken somewhat the copyright monopolist's hold on the market.

Finally, once the system gets off the ground, the lower cost and extra convenience to consumers will lead to pressure for reluctant labels to participate. Even consumers who today are willing to pay $10 for albums at stores may become reluctant to do this once they get used to paying $5 from home. Though the existing market players might not like the system, I think they'll have to accept it. To take an analogous case, prices often fall not because sellers prefer that they fall, but because new entrants, or small vendors looking for market share, drive the prices down. While large producers may try to stop this, they generally can't.

The post Setting the Wayback Machine to 1995: "Cheap Speech and What It Will Do": Music: The New System appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] White Multicultural Student Services Administrator's Race Discrimination Claim Against U Wisconsin Can Go Forward

From yesterday's decision by Judge James Peterson (W.D. Wisc.) in Hoffman v. Bd of Regents:

Hoffman previously worked in the Blugold Beginnings office at the university, which provides support to low-income, first-generation, and other underrepresented students. In 2022, Blugold Beginnings merged with the Office of Multicultural Affairs to become the Multicultural Student Services department.

After Hoffman was appointed interim director of the new department, students, faculty, and staff objected to her appointment because she was white. Hoffman [sues] …, contending that the university … demoted Hoffman from her leadership position, … forced Hoffman to transfer to a different department, and then retaliated in various ways against Hoffman for filing a racial discrimination complaint….

In late January 2022, Diaz {the vice chancellor of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Student Affairs} asked Hoffman to serve as interim director of the new MSS department and Hoffman accepted. Hoffman's appointment generated backlash from students. At open houses on February 14 and February 18, students asked Diaz why she "hired a white woman as the interim director" and questioned whether Diaz "personally fe[lt] that white staff can do as effective a job as a person of color, within a space for people of color." The student senate also released a resolution on February 28 expressing "concerns over placing white-identifying individuals in positions of interim leadership for major [equity, diversity, and inclusion] offices."

Some faculty and staff also expressed disapproval with Hoffman's appointment as interim director. In a private meeting with Diaz on February 11, non-white faculty members expressed concerns about the university placing white staff in positions formerly held by non-white staff. (It's disputed whether the faculty knew at this point that Hoffman was to be interim director of MSS.) After the student senate resolution was released, student coordinator Jensen said in a staff meeting that she agreed with the resolution. She also told Hoffman that Hoffman's white identity was "an issue" for Jensen. Hoffman says that staff members also "participat[ed] with the students" at the open houses, but Hoffman did not identify any specific statements made by staff members….

Diaz decided to remove Hoffman as interim director of the MSS department and make her the assistant director instead. In early spring 2022, Hoffman began using the assistant director title on a working basis. She also received overload salary payments for performing duties consistent with the assistant director role, including supervising new MSS staff and chairing a search committee to appoint a new MSS coordinator. In early June, Diaz initiated a "request to fill" application with the HR department to formalize Hoffman's position as assistant director of MSS….

Hoffman continued to experience opposition to her role in the MSS department. At open houses throughout the spring and summer, attendees criticized the appointment of white people to leadership positions in the MSS department. In May, … a native American professor[] emailed O'Halloran expressing concern that Hoffman and [a] MSS administrative assistant …, "two white women … who have overpowering voices," were chairing the search committee for four new positions in the MSS department.

A group called "UWEC BIPOC Alumni" posted criticism about the MSS department's staffing on social media: the group did not mention Hoffman by name, but they said that the department was "overwhelmingly white" and that "positions of decision-making authority [were being] strategically replaced by white folks." Some faculty and staff "liked" the alumni group's posts on social media. Over 100 faculty members also signed an open letter expressing concerns about the "marginalization" of students served by the equity, diversity, and inclusion department, the resignation of staff who served those students, and the "disregard for collaboration and shared governance" in the department….

The court allowed Hoffman's discrimination claims to proceed to trial as to her demotion from interim MSS director to assistant director:

Hoffman asserts that in January 2022, Diaz asked Hoffman to be interim director of the new MSS department and Hoffman accepted. But in early March, Diaz demoted her to assistant director because of the backlash from faculty, staff, and students who did not want a white person leading the department….

Hoffman lost job responsibilities when Diaz demoted her from the interim director role, namely supervisory responsibilities over student coordinators Maggie Jensen, Vaj Fue Lee, and Jacqueline Navarez. A reasonable jury could find that losing these responsibilities was an identifiable harm to her employment.

As for the causation element, the university contends that Diaz demoted Hoffman not because of discriminatory animus but to "shield [Hoffman] from the negative reactions of others." The university argues that Hoffman cannot show that the demotion occurred because of her race if the decisionmaker, Diaz, didn't hold racial animus. But this argument mischaracterizes the standard for a racial discrimination claim. Plaintiffs in discrimination cases frequently rely on evidence of a decisionmaker's racial animus to prove that an adverse action was caused by the plaintiff's race, but animus is not an element of a discrimination claim. Plaintiff must show only that the decisionmaker took an adverse action "because of" plaintiff's race. A well-intended but patronizing effort to shield an employee from racial hostility is enough to show causation….

Hoffman has adduced evidence that Diaz demoted her from the interim director position because "people … had questioned whether a white person" should be leading the MSS department. That's enough for a reasonable jury to find that Diaz would have made a different decision had Hoffman not been white.

And the court allowed Hoffman's discrimination and retaliation claims to proceed to trial as to her transfer from the MSS department to the SSS department. The court rejected a third discrimination claim, however, as well as her hostile environment harassment claim.

The post White Multicultural Student Services Administrator's Race Discrimination Claim Against U Wisconsin Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Setting the Wayback Machine to 1995: "Cheap Speech and What It Will Do": Music: The New System

[I thought it would be fun to serialize my 1995 Yale Law Journal article "Cheap Speech and What It Will Do," written for a symposium called "Emerging Media Technology and the First Amendment.) Thirty years later, I thought I'd serialize the piece here, to see what I may have gotten right—and what I got wrong.]

[a.] What It Will Look Like

I want to start by discussing how the new technologies will change popular music. These changes may be less politically momentous than the similar changes that I think will happen in print and video. But the music industry will probably be the one that changes most quickly; and in any case, many of the things I say in this Section-about cost savings, increased choice, information overload, and so on-will apply equally well to the others.

The reasons for the changes will be very simple: There's lots of money in them. The existing music distribution system is inefficient, both for consumers and for musicians. For consumers, in particular, it has three problems:

Cost: Music costs more than it could. Consumers must pay about $8 to $15 for a new album, though musicians generally see less than ten percent of this in royalties.

Choice: Consumers get a smaller selection than they could-many titles, especially ones that are relatively old or that appeal to fairly small markets, aren't available in most places.

Convenience: To buy music, a consumer has to take the time and trouble to go to the store.

And these problems translate into problems for musicians. High cost, low availability, and the inconvenience of buying lead to fewer sales.

These inefficiencies aren't the result of some sinister plot or even of market irrationality. They are an inevitable consequence of the existing distribution system. People today must buy music on some tangible medium, such as tape or CD. This means they generally have to go to the music store (inconvenient), which has limited shelf space (lowering the choice). And the tangible medium has to be created, imprinted, distributed, and sold (costly).

The infobahn, once it brings high-speed two-way communications to private homes, is a far superior way of delivering music to the consumer. It will work something like this:

(1) Using your computer-or perhaps your TV set, with a keyboard, a touch screen, a mouse, or even voice activation-you access an electronic music database. This database (actually, there'll probably be several competing databases) will contain virtually all the music that's available in electronic form.

(2) You choose the music you want, by album name, by song title, by artist, by composer or songwriter, or by genre. You might even ask the computer for suggestions, based on the artists or albums you tell it you like. (The suggestions will be derived from judgments entered into the computer by reviewers.) You can also browse in some way, perhaps looking only at music of a particular kind, or music that has gotten good reviews. You can then play the music, to make sure you really want to buy it.

(3) Once you decide you like it, you download the album to a digital recorder connected to your computer. Your bank account gets debited automatically.

This would mean:

Cost: Once the music is recorded-which even now can cost fairly little -the only significant other expenses will be advertising costs, royalties, the cost of electronic distribution, and the cost of the recording medium (which will be supplied by the customer). There'll be no need to spend money to create tangible recordings, ship them, and sell them. Assuming cheap electronic transmission (an assumption I'll try to support shortly), a CD-quality album may well cost as little as $3 to $5—a $1 royalty, plus amortization of the recording costs and advertising costs, plus the $1 or $2 that the customer will have to pay for the recording medium. An artist who's willing to pocket less money to get more customers might be able to charge $3 or less.

Choice: You'll have close to the whole music library of the world at your disposal. Copyright owners will be able to sell to any infobahn-connected consumers, not just to the ones who have access to a store that's willing to stock the work. Because there'll be no shelf-space limitation-computer storage is cheap and getting cheaper-it won't matter how esoteric your tastes are; there'll be room for nearly everything.

Convenience: You'll no longer have to drive to the music store or wait in line. You'll also be able to select what you want more conveniently, because you'll easily be able to pre-listen to what you're buying, and because you'll have readily available reviews. The copyright owners will benefit from this system too, because whenever consumers read a good review or like a song they hear on the radio, they'll be able to buy the music instantly, or at most have to wait until they get home.

[b.] Why It Will Look Like This

Music Database Operators: There's a lot of money to be made here. In the United States alone, there were over 475 million albums sold in the first six months of 1994, at an average suggested list price of over $10 each, including both the more expensive CDs and the cheaper, lower sound-quality tapes. The sales volume should increase as costs go down, and the convenience of buying the product from home should raise volume even more. Skimming even, say, ten cents per transaction would mean, at today's rates, almost $100 million yearly.

Mail-order CD catalogs—including computerized ones, such as cdconnection.com, which is accessible either directly through your modem or through the Internet —are already the first step toward the system I describe. They attract customers by offering a large selection, slightly lower prices, and the convenience of home shopping (partly countered by the inconvenience of having to wait for the CDs to arrive by mail ). {Cdconnection.com, which lets you order CDs from your computer but delivers them to you through normal mail, boasts over 100,000 CDs, covering the entire catalogs of all U.S. major labels and more than 2000 independent labels, plus several thousand import CDs. I had looked for years for one album—Leonard Cohen's New Skin for the Old Ceremony—and finally found it there.} Direct downloading should provide even greater cost savings, selection, and convenience.

Setting up a music database shouldn't be much harder than starting a mail-order CD business today; and it should be much easier than starting a chain of music stores. Like the U.S. Postal Service, the telephone system, or the Internet, the infobahn should let any business be accessible through it. The database operators will have to buy computer equipment and design some software, but this shouldn't cost much. Even a database operator who gets only, say, 1% of the total market can make almost $10 million yearly by charging a $1 markup (which will still save consumers a lot of money). Ten million transactions yearly—thirty thousand daily—can easily be handled even today with fairly cheap equipment. {Storage of the music shouldn't be a problem, either. While the central databases will need a lot of storage, disk space today costs less than $1 per megabyte, down from a bit under $2 per megabyte a year before.} And the low cost of setting up a database should keep competition high and consumer prices low.

Copyright Owners: There's also profit here for copyright owners. The new system will let copyright owners exploit markets that are closed to them now: people who would pay, say, $5 for electronic delivery of an album but not $10 for the album in the store (cost); people who don't have access to stores that stock the album (choice); and people who otherwise wouldn't take the trouble to go to the record store, or who may want to buy an album they hear on the radio but forget about it by the time they get to the store (convenience). And the electronic database operators would easily be able to pay the copyright owners royalties as high as what the owners get from music store sales, if that's what it takes to get the owners to sign up.

This will become especially true when, as some copyright owners join, others will find themselves pushed by competitive pressures to do the same. Once even a few albums become available for $5 rather than $10, albums that sell for $10 will be at a significant disadvantage. Though music isn't fungible—loyal fans of New Kids on the Block might not think Tom Waits an adequate substitute—some product substitution will doubtless occur.

{Some people to whom I've described this theory have suggested that copyright owners won't license their music for electronic distribution because they fear copyright infringement. Once music is electronically available, the argument goes, people could buy it once and then upload it to some computer bulletin board, or sell bootleg copies via e-mail. Copyright owners will therefore be reluctant to allow electronic music distribution.

But while electronic copying is indeed a serious threat to music copyright owners, this threat will exist whether or not the music is available in some central database. Even without an electronic music database, a pirate could easily go to the store, buy a CD, and make many copies of it on his DCC or Minidisc recorder. The electronic databases might make commercial piracy more tempting, because they will increase the number of people with digital players, who are the pirates' potential customers. On the other hand, some of this effect may be counteracted by the lower costs of legitimate buying through the databases. Pirates will thrive more when their rip-offs are competing with $10 albums than with $5 albums.

The music industry's reaction to DAT (Digital Audiotape) recorders, the first digital-quality home recording medium, is worth noting. When it became likely that home digital recording could let people easily make CD-quality copies of music, the music industry and the DAT industry agreed to a compromise, embodied in the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992. The Act (1) legalized home noncommercial copying; (2) taxed DAT recorders and blank DATs, with the proceeds going to a fund to compensate copyright owners for the expected losses due to home copying; and (3) required DAT recorder manufacturers to design their recorders in a way that limits the possibility of large-scale copying.

A similar solution might be set up for the electronic music databases. The music industry may be able to push through a law that would compensate for possible copying losses by: (1) requiring an extra royalty payment on each electronic sale, and (2) requiring, say, designers of e-mail systems or bulletin board systems to put in checks that would make unauthorized copying harder. This is hardly a foolproof solution, but it might provide some protection for copyright holders while still allowing them to exploit a powerful new sales tool.}

Consumers: As I mentioned before, consumers can also benefit greatly from the new system. True, any change-especially one involving computerization-risks alienating customers, but the new system can be made very user-friendly. The system needn't be any harder to use than an ATM; and, as with the ATM, which has probably saved billions of person-lunch-hours per year, the new system's benefits should be substantial enough that people will learn to use it.

Moreover, the physical advantages of music store layout-the ability to browse, and the possibility of stumbling over something good that one hadn't even thought of buying-could be made available on the home computer, too. The software could easily have a general "Browse" (or "Browse The Kind Of Music I Like") feature, if this is what users want. The software could also have other useful features—such as a convenient pre-listen mode, or cross-references to reviews—that many music stores don't have. {Cdconnection.com's main information screen asserts that its system contains 50,000 ratings from fellow customers, and 26,000 professional ratings from the All-Music Guide. You can look up the ratings easily as you browse through the CDs.} And if people really need human help, the software could, at the touch of a button, switch to a voice connection with an operator at the central database location.

{Some consumers might actually enjoy going to music stores, either because they like the atmosphere, because they prefer being around other people rather than closeted at home, or because they like to go to music stores with friends. Movies, for instance, haven't been entirely supplanted by VCRs, in part because of the better picture and sound quality, but in part because people like going to the movies.

But even if one sees going to the music store as a pleasure rather than an inconvenience, there will probably be few people to whom it will be worth the extra cost. People can socialize with friends, or mingle with strangers, in lots of other places. If home access provides a better deal on music, most people will just buy the music at home and do their socializing at a restaurant or the beach.}

Technology: The new setup will require a good deal of new technology, but what's not here yet is coming soon. Digitally recorded music is simply a collection of data, no different (from the computer's point of view) from your WordPerfect document. Music is already sent through the Internet. There's no reason it can't be sent down the infobahn to your home.

{Today such a transmission would take quite some time, because it goes over comparatively slow phone lines. The whole point of the infobahn, though, is to change all that. Data can be sent much more quickly through fiber optics than through wires; though no one is quite sure, people are generally expecting speeds tens of thousands of times greater than those of phone lines, which now generally ship about 1000 bytes per second. Cable TV wires can already be used for data transfers 50 times faster than those over phone lines.}

Once the music arrives—in data form—at your home, it will need to be recorded on some high-quality medium. Two familiar media are nonstarters: Normal analog audiotape is too low-quality, and today's CDs are read-only. But two recently introduced technologies—digital compact cassettes (DCCs) and MiniDiscs—might have what it takes. They both provide sound quality as good as that of a CD; you should be able to download music to them from your home computer, and then play it at home, in your car, or in your Walkman. Today this equipment costs a lot, but prices are expected to fall as the technology improves and economies of scale kick in, just as they did for normal CD equipment. {MiniDisc recorders/players now cost $800; DCC recorders/players cost $400. Blank MiniDiscs start at $14 each, blank DCCs at $8.50.}

{Actually, you might even skip the recording step and instead play the music directly from a central database (just as you could today listen to music over the phone, only with much better sound quality). You might then be charged on a per-play basis rather than on a once-per-album basis. You'll still need to record the music, though, if you want to listen to it away from your infobahn connection, say in your car. And if transmission costs are high enough, you might prefer to pay them only once when you download the album, rather than every time you listen to it.}

To use this system, people will need computers, but there are already an estimated thirty million home computers installed today. The cheapest ones now cost about $700, and, of course, this money will buy you many more features than just home music delivery.

Moreover, even people who can't afford a home computer and a home digital recorder might still use the system through public music vending machines. These machines may cost more than the home versions, because they'll need to be more resilient (and probably more theft- and vandalism-proof); a fragile keyboard interface might have to be replaced by a touch screen interface, or by something similarly robust. Still, this shouldn't be especially difficult or expensive-consider ATMs, video games, and public lottery ticket machines. So long as there are millions of people who don't have home computers and home digital recorders, there'll be plenty of incentive to develop these technologies. Indeed, some music stores already have computerized music catalog machines (called Muzes) that have these features-the music vending machines would basically be Muzes, plus an infobahn hookup, a credit or debit card reader, and a recorder.

Finally, it shouldn't be hard to charge people electronically for using the service. The system could ask for a credit card number when you access it-much as is done today for phone sales, or for cdconnection.com computer sales-and confirm it while you're shopping. Better yet, it could charge you through your infobahn provider, much as 900 numbers now charge through the phone company. Music vending machines could accept credit cards or debit cards. And even more convenient forms of electronic payment may soon be available; electronic payment could be a boon to many businesses, and the market demand for it has generated a good deal of research and investment.

The post Setting the Wayback Machine to 1995: "Cheap Speech and What It Will Do": Music: The New System appeared first on Reason.com.

[Steven Calabresi] President Trump Made History Last Week on the Supreme Court's Shadow Docket

[The Supreme Court very strongly hinted that it will overrule, or greatly narrow, Humphrey's Executor v. United States (1935).]

President Donald Trump began his second term with a sweeping and much needed "firing spree" in which he went after the notorious independent agencies in the so-called Headless Fourth Branch of the Government. A National Labor Relations Board Commissioner and a Merit Systems Protection Board Commissioner, both of whom were protected by statutory clauses providing that they could only be fired for cause, were instead fired at will. The Commissioners whom Trump fired had secured an order from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit reinstating them in their jobs.

In an unsigned 6 to 3 order on May 22, the Supreme Court stayed the D.C. Circuit's reinstatement order, saying the plaintiffs were unlikely to prevail on the merits because they were exercising "executive power" in violation of Seila Law LLC v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 591 U.S. 197 (2020). Justice Kagan's dissent quite accurately accused the six Republican appointed justices who were in the majority of implicitly overruling an infamous 90-year-old precedent, Humphrey's Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935).

Former Attorney General Ed Meese, in an address that he gave on February 27, 1986, swung for the fences and called for the overruling of Humphrey's Executor 39 years ago and an end to the headless Fourth Branch. Meese argued that independent agencies exercising "executive power" are unconstitutional since the Vesting Clause of Article II of the Constitution provides that "The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America" and not also in a headless Fourth Branch. A generation of Federalist Society scholars, including me and especially, Professor Saikrishna Prakash of the University of Virginia School of Law, have followed Ed Meese's call and have urged the overruling of Humphrey's Executor. See, e.g., Steven G. Calabresi & Christopher S. Yoo, The Unitary Executive: Presidential Power from Washington to Bush (2012); Steven G. Calabresi & Saikrishna B. Prakash, The President's Power to Execute the Laws, 104 Yale Law Journal 541 (1994).

Three people deserve great credit for this enormous victory in a campaign to get Humphrey's Executor overturned that has lasted for 39 years. First, and most obviously, credit goes to President Donald Trump for having the resolve to fire independent agency commissioners, which no recent other President—including even Ronald Reagan—had done. Second, credit goes to Reagan's former Attorney General Ed Meese for boldly pointing out what needed to be done 39 years ago, for which he was thrashed then by the press and even by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor and his own Solicitor General, Charles Fried. Third, a huge amount of credit goes to President Trump's first-term White House Counsel, Don McGahn, who helped President Trump in appointing Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. Like Ed Meese 40 years ago, Don McGahn made it a top priority to appoint Supreme Court justices and lower federal court judges who believed in the theory of "The Unitary Executive" and who would work to get rid of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's oppressive, undemocratic, and unconstitutional Administrative State.

All three of President Trump's first-term appointees joined this ruling together with Justice Clarence Thomas, a George H.W. Bush-appointed justice, and George W. Bush's two appointees, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito. Chief Justice Roberts has paved the way for last week's victory in opinion after opinion over the last fifteen years, and he also deserves a lot of credit for this great victory.

Don McGahn is the brilliant lawyer who planted the seeds so that this 1937-like constitutional moment in presidential power law would happen. President Trump in turn deserves a huge amount of credit for making McGahn his first term White House Counsel. As Trump promised legal conservatives, you will win so many times you will almost get tired of winning! Libertarians as well should thank McGahn and President Trump for this as well.

Incidentally, I had the personal experience of getting a huge amount of help behind the scenes from McGahn in writing my amicus brief with Attorneys General Ed Meese and Michael Mukasey and Professor Gary Lawson in Trump v. United States. That amicus brief helped persuade District Judge Aileen Cannon to toss out former special counsel Jack Smith's unconstitutional indictment of Donald Trump in the classified documents case brought against him by the former Biden Administration. Don McGahn is one of the most talented libertarian lawyers of all time.

[UPDATE 5/28/2025 10:28 am: Eugene writes: I inadvertently scheduled this umder my own name, but it was from Steven Calabresi; I've corrected the byline.]

The post President Trump Made History Last Week on the Supreme Court's Shadow Docket appeared first on Reason.com.

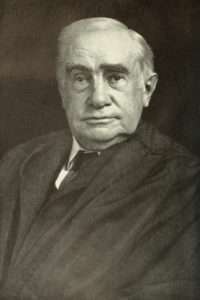

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: May 28, 1906

5/28/1906: Justice Henry Billings Brown retired.

Justice Henry Billings Brown

Justice Henry Billings BrownThe post Today in Supreme Court History: May 28, 1906 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Wednesday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Wednesday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

May 27, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Video of Cato Institute Virtual Event on "Tariffs, Emergencies, and Presidential Power"

[I spoke along with my Cato colleague Walter Olson.]

Today the Cato Institute held a virtual event on "Tariffs, Emergencies, and Presidential Power." Cato Institute Senior Fellow Walter Olson and I discussed Trump's "Liberation Day" tariffs attempting to leverage the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA), the lawsuit against them brought by the Liberty Justice Center and myself on behalf of five US businesses harmed by the tariffs, nondelegation, the general problem of abuse of emergency powers, and other related issues. Brent Skorup of Cato (who is also a former student of mine!) moderated, and asked some great questions. Here is the video:

I have gone over the legal issues raised by Trump's IEEPA tariffs in greater detail in my Lawfare article, "The Constitutional Case Against Trump's Trade War." See also my post on why these tariffs threaten the rule of law, an issue we discussed at the Cato event.

The post Video of Cato Institute Virtual Event on "Tariffs, Emergencies, and Presidential Power" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] These Are Trained Judges, Readers! Don't Try This Yourselves at Home!

Readers of today's opinion in Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale & Dorr LLP v. Executive Office of the President (which I think got it largely right in its substantive analysis), might notice that it included 26 exclamation points (not counting one in a quote from President Trump). Here is just a subset:

The Founding Fathers knew this! …

Please—that dog won't hunt! …

The causal chain contains at most two links, and it is certainly not highly attenuated! …

Please! …

I agree! …

Taken together, the provisions constitute a staggering punishment for the firm's protected speech! The Order is intended to, and does in fact, impede the firm's ability to effectively represent its clients! …

Thus, to the extent the President does have the power to limit access to federal buildings, suspend and revoke security clearances, dictate federal hiring, and manage federal contracts, the Order surpasses that authority and in fact usurps the Judiciary's authority to resolve cases and sanction parties that come before the courts! …

I appreciate that the author is a federal judge, and I'm not, but my sense is that the exclamation points do more to detract from the persuasiveness of the opinion than to advance it. And even if it works for a judge, I would strongly recommend lawyers to avoid such massive use of exclamation points—indeed, even any use of exclamation points. ("Quod licet Iovi, non licet bovi," as my father liked to quote.)

To pass along again (albeit imprecisely) an exchange I blogged about in 2007,

[Talk had turned to effective legal writing; B is a smart soon-to-be-law-student.]

A. Another thing I learned about legal writing: Don't use exclamation points for rhetorical emphasis. And all-caps — don't do that, either. Bold is also very bad. So is italics: It's OK to use it to highlight important terms in quotes, or terms that you're trying to distinguish from each other in your arguments, but don't use it as an exclamation point.

B. But what then are you supposed to use for rhetorical emphasis?

A. How about … forceful arguments?

The post These Are Trained Judges, Readers! Don't Try This Yourselves at Home! appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers