Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 87

June 1, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] "Trump Remedies to Harvard's Ills Should Respect Free Speech," by My Hoover Institution Colleague Peter Berkowitz

This excerpt from his piece today in Real Clear Politics should give you a flavor for the argument; the entire piece is worth reading:

In its multi-pronged efforts to pressure Harvard to live up to its self-proclaimed mission to seek and transmit knowledge and pursue the truth, the Trump administration seems to be of two minds on free speech. Along with demanding that Harvard meet its obligations under civil-rights law to combat antisemitism on campus and end race-based discrimination or lose federal funding, the Trump administration has conditioned billions in taxpayer dollars on the university's protecting the free speech on which excellence in scholarship and teaching depend. Yet the White House's remedies to Harvard's censoring and indoctrination clash with free-speech imperatives and risk turning Harvard, with its shameful record of stifling dissent from progressive orthodoxy, into a free-speech martyr.

Only weeks after inauguration, Vice President JD Vance delivered an unequivocal message to America's European friends: Free speech is central to our shared civilization and essential to our prosperity and security…. But the Trump administration's campaign against Harvard sends an equivocal message on free speech, affirming it and calling it into question….

Notwithstanding their many and serious faults, America's elite universities conduct extensive and costly scientific research that fuels America's global leadership in technology. A substantial portion of the billions in federal funds earmarked for Harvard frozen by the Trump administration supports such scientific research. Consequently, Trump's Harvard remedy erodes America's "technological edge." By operating against Harvard with a sledgehammer, the Trump administration not only breaks its promise to respect free speech but also impairs a core national-security interest….

The post "Trump Remedies to Harvard's Ills Should Respect Free Speech," by My Hoover Institution Colleague Peter Berkowitz appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Is Justice Barrett "Solidifying Herself as the Swing Justice"?

[Claims that Justice Amy Coney Barrett is at the center for the Court are not supported by the data. The truth is more complicated.]

In a recent post, Josh Blackman writes that "Justice Barrett is solidifying herself as the swing Justice," citing a recent analysis by Adam Feldman of Legalytics. As someone who follows the Court quite closely, this did not seem right to me. It turns out my skepticism was warranted.

The primary point of Feldman's analysis, "The Myth of the Modern Swing Vote," is that there is no Justice Kennedy-style median justice on the current court. Rather, there is a more complex dynamic among the Court's six conservative justices that results in shifting coalitions depending upon the subject-matter and salience of the case at hand. But even with that caveat, and if one solely wishes to focus on which conservative justice's vote is most often in play to form a majority with multiple liberal justices, Feldman's analysis does not point to Justice Barrett. Indeed, it expressly rejects that position.

On the "central question" of "Which conservative justices act as swing votes—and under what conditions?" Feldman writes:

To answer this, I analyzed each instance where a conservative justice—Roberts, Kavanaugh, Barrett, Gorsuch, Alito, or Thomas—joined at least two liberal colleagues (Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, or Jackson) in forming the majority in a 5–4 or 6–3 decision. These are the votes that shift outcomes and signal ideological movement.

The results were clear—and revealing.

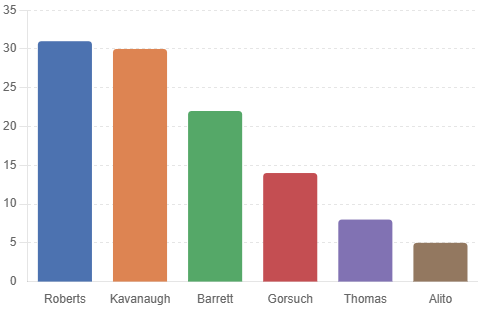

Chief Justice John Roberts was the most frequent swing vote, joining liberal-majority coalitions 31 times. Justice Brett Kavanaugh was close behind with 30 swings, followed by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who broke ranks in 22 decisions. By contrast, Justice Gorsuch did so just 14 times, and Justices Thomas and Alito remained firmly aligned with the conservative bloc, swinging only 8 and 5 times, respectively.

And later he writes: "Roberts remains the most institutionally consistent swing voter."

Perhaps the Chief Justice as swing should be discounted, however, as it takes at least one more conservative justice to flip the outcome in a case. But even if one discounts the Chief Justice, Feldman's analysis identifies Kavanaugh as much more of a swing than Justice Barrett. It's even illustrated in a graph.

Feldman notes that the predictive model he develops is strongest with regard to Justice Barrett--suggesting a greater degree of jurisprudential consistency--but that is a different question. So he writes:

The quantitative and case-level analyses converge on a central insight: Justice Barrett's swing behavior, though less frequent than Roberts or Kavanaugh, is the most systematically tied to the nature of the case. While Chief Justice Roberts often garners attention as the Supreme Court's institutional swing vote, the data reveals a quieter but consequential evolution: Justice Amy Coney Barrett is emerging as a swing vote in key domains—particularly those involving enforcement power, procedural fairness, and statutory interpretation.

Since joining the Court in 2020, Barrett has aligned with liberal justices in multiple closely divided decisions. Her swing behavior concentrates in issue areas defined by constraint and clarity: the 4th Amendment & Police Powers and Post-Conviction & Habeas Corpus clusters. Her votes in these domains don't signal ideological drift but reflect a jurisprudence rooted in textual rigor and structural restraint. . . .

Barrett's swing votes do not appear driven by ideology—they are rooted in textual discipline, a willingness to reconsider enforcement practices, and a procedural sensibility that sometimes leads her to coalition with the Court's liberal wing. She is not a centrist in the Kennedy mold. But she is increasingly a structural voice for constraint—especially when liberty, enforcement, and precision intersect.

And in terms of how Justice Barrett's behavior differs from that of Roberts and Kavanaugh:

Chief Justice Roberts remains the most frequent swing voter. But his influence is no longer universal—it is situational, shaped by questions of institutional credibility and precedent. Justice Kavanaugh is nearly as likely to swing, particularly in cases involving procedural fairness or criminal law. And Justice Barrett, while swinging less frequently overall, shows the clearest directional shift: a rising presence in clusters where state power, enforcement boundaries, and constitutional dignity are contested.

This reflects not the death of the swing vote—but its transformation. The era of a single ideological median, epitomized by Justice Kennedy, has given way to a modular model: different conservative justices swing in different legal terrains, guided by distinct judicial logics.

Kennedy's swing votes spanned doctrines and decades. His role was personal, often framed in the language of dignity and individual autonomy. But today's Court does not hinge on personality. It hinges on terrain.

Roberts swings where institutional legitimacy is at stake—especially in administrative law, precedent-sensitive disputes, and interbranch tension. Kavanaugh swings when procedural integrity comes to the foreground—cases involving arrest process, prosecution, or due process claims. Barrett swings in domains of constitutional restraint—where liberty and dignity intersect with enforcement, and where doctrinal clarity can limit state power without signaling ideological compromise.This fragmentation has both doctrinal and predictive consequences.

Among other things, Feldman notes, identifying and understanding the legal context of a given case is more important than political identity in determining whether one of these justices is likely to swing. That bottom line may not fit neatly into partisan or ideological complaints about any given justice's voting record, but it does provide important insight about the current Supreme Court.

The post Is Justice Barrett "Solidifying Herself as the Swing Justice"? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] David French Is Right: Judges Do Seek The "Respect" Of Their Peers

[And that is the problem.]

President Trump continues to shift paradigms and cause people to reconsider long-held beliefs. His latest Truth Social post has launched a thousands takes. I've already focused on Ed Whelan and the Wall Street Journal. Here, I will write about David French's column in the New York Times.

David purports to explain why many Republican-appointed judges have ruled against Trump. David is not simply writing based on what he reads in judicial opinions. Rather, he suggests that he has some inside information--or at least personal insights. French writes:

I come from the conservative legal movement, I have friends throughout the conservative legal movement (including many Trump-appointed judges), and I think I know the answer, or at least part of it.

David is speaking, or least he purports to speak, for judges that Trump appointed during his first term.

I've written that Whelan and the Wall Street Journal got the situation 100% backwards. French, to his credit, accurately perceives the symptoms, but makes the wrong diagnosis.

French explains that judges are more interested in the respect of their peers than the applause of the crowd:

The immense pressure that Trump puts on his perceived rivals and opponents exposes our core motivations, and the core motivations of federal judges are very different from the core motivations of members of Congress. Think of it as the difference between seeking the judgment of history over the judgment of the electorate, and to the extent that you seek approval, you place a higher priority on the respect of your peers than the applause of the crowd.

What David writes here is absolutely correct. But I don't think he sees the problem. Who are the "peers" that judges seek the approval of? Legal elites. The New York Times. The Wall Street Journal Editorial Page. The faculty at top law schools. Conservatives who are allowed in polite company. Look at the fawning treatment that Judges Wilkinson and Boasberg have received in recent months. By contrast, look at the crucible the press placed Judges Cannon and Judge Kacsmaryk under. If you rule the right way, you win awards and receive standing ovations from bar associations. If you rule the wrong way, you receive death threats. (The media has not seen fit cover the two cases in which defendants have pleaded guilty to threatening Judge Kacsmaryk--not just sending pizzas.)

There is an entire ecosystem established on the left and center-right to keep conservative judges in line. David is a focal point of that ecosystem. Indeed, this column, whether by design or intent, reinforces the theme that he and others are the gatekeepers of valid arguments.

Judges of all stripes seek the approval of one group over the other. David is simply telling us that seeking his approval is just fine, but don't even think about seeking other types of approval.

Judge Ho has written that most judges fear getting booed. He's right. And many judges really fear getting booed by people like Ed Whelan, David French, and the Wall Street Journal. What makes Trump nominees like Bove different is that they don't care. They reject these pillars of the conservative establishment. And in turn, the pillars can only charge people like Bove with being partisan hacks.

When I write about judicial courage, I am not simply speaking about standing up to pillories from the left. It also entails resisting pillories from the right. And this is the sort of fracture that we see happening before our eyes.

Those who once had influence see that influence slipping away. And the locus of influence is moving.

French writes:

If your decisions are the measure of your worth, then seeking the applause of the crowd can lead you down a dangerous path.

I agree, but I think seeking the applause from French and others is leading the Supreme Court down a very dangerous path. There is a storm brewing on the horizon.

Judges should stop seeking applause, full stop. Decide the case based on the law, and put all political considerations aside. We will all be much better for it. Judges have to follow the Constitution, just like the President.

The post David French Is Right: Judges Do Seek The "Respect" Of Their Peers appeared first on Reason.com.

May 31, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Hub and UnPopulist Podcasts About the Tariff Case

[The podcasts cover the case and its relationship to the more general problem of abuse of emergency powers.]

I recently did two additional podcasts on our win in the tariff case before the US Court of International Trade, and its implications. One was with the Canadian conservative website The Hub:

The other podcast was with The UnPopulist (available here).

The Hub podcast focuses more on the legal issues at stake, while that with the UnPopulist considers the broader issue of abuse o emergency powers, and what can be done about it. I discussed that latter issue in greater detail in a recent Lawfare article.

The post Hub and UnPopulist Podcasts About the Tariff Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] What Message Does Emil Bove's Nomination Send To Justices Thomas and Alito?

[Do you really think Justices Thomas and Alito would prefer another Justice Barrett?]

On Friday, the Wall Street Journal editorialized against Emil Bove's nomination. The Journal echoed points by Ed Whelan and others that fewer judges will step down if they think Trump will replace them with judges like Bove--including Justices Thomas and Alito:

The President should understand that his attacks on judicial conservatives will hurt his own agenda and legacy. His social-media post is the talk of the judicial ranks, and he is making no friends. Mr. Trump is likely to see fewer judges retire, lest they be replaced by partisan hacks. That includes Justices Samuel Alito (age 75) and Clarence Thomas (76). Keep exercising daily, good Justices.

Like Whelan, the Journal gets things 100% backwards. In Trump-related cases, Justices Thomas and Alito are dissenting alone. Look at A.A.R.P. v. Trump. Where are the three Trump appointees on that case? Justice Kavanaugh was the closest, but he still concurred. More generally, Justice Gorsuch has voted with Alito and Thomas on most religious liberty issues and separation of powers cases, but who can forget Bostock, McGirt, Brackeen, the tax return cases, and others. And as Adam Feldman's recent analysis shows, Justice Barrett is solidifying herself as the swing Justice. I appreciate this AI graphic from Adam's post.

If I had to guess, Justices Thomas and Alito would not want someone like the three Trump appointees to replace them. They would want someone who votes like them. Bove would likely fill the mold. Indeed, if the same sorts of people are advising Trump on his next batch of Supreme Court nominee who advised on his first batch, Thomas and Alito would just as well hold on.

Meanwhile, quotes an unnamed conservative "consultant" who apparently has such strong insights, he cannot be named.

For Trump's allies, the Federalist Society now represents the old guard that "hide[s] behind a philosophy" instead of supporting the Republican cause, said one conservative consultant, who was granted anonymity in order to speak freely about dynamics in the Republican legal world. They want more people like Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito and fewer people like Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the person said. . . .

"They don't want someone who's just going to be like, 'We're going to follow the law and do the originalistic thing, and whatever the result is, so may be it,'" said the consultant. "They want someone [who] can figure out how to get the result that they want."

Okay "originalistic" is not a real thing. I can't recall an actual originalist who has ever used this word. It mocks originalism. I have my doubts about this "conservative consultant's" insights into the conservative legal movement.

In any event, this quote backfires, big league. Justices Thomas and Alito are the standard-bearers for the conservative legal movement. This so-called conservative, by calling Emil Bove a political hack, is calling Thomas and Alito a hack.

More often than not, the difference between Justices Alito and Thomas, and their colleagues, is not jurisprudence, but courage. Alito and Thomas have been saying this for years. Only now, people are listening.

A kind note to Politico and other outlets: you can call me to get an on-the-record quote. You don't need to quote anonymous posters. Much of the reporting on this kerfuffle has been unusually one-sided. Quoting a Republican who disagrees with the Bove nomination does't count as "balance."

The post What Message Does Emil Bove's Nomination Send To Justices Thomas and Alito? appeared first on Reason.com.

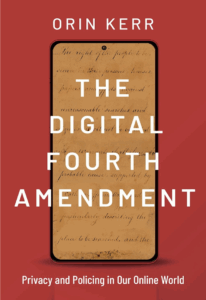

[Orin S. Kerr] Stewart Baker vs. Orin Kerr on "The Digital Fourth Amendment"

[A debate between Volokh bloggers.]

My friend Stewart Baker discussed his recent interview of me about my new book, but let me add two important links. First, you can listen to our podcast debate about the book here. And just as importantly, you can buy the book here.

The post Stewart Baker vs. Orin Kerr on "The Digital Fourth Amendment" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Plaintiff's Idaho Murder Libel Claim Continues to Beat Defendant's "Psychic Intuition"

[More in Prof. Rebecca Scofield's defamation lawsuit against alleged psychic Ashley Guillard, based on Guillard's accusation that Scofield was involved in the Nov. 2022 murder of four University of Idaho students.]

From Friday's decision by Judge Raymond Patricco (D. Idaho) in Scofield v. Guillard:

This case arises out of the tragic murder of four University of Idaho students in November 2022. Plaintiff Rebecca Scofield is a professor at the University of Idaho. She alleges that, despite never meeting any of these students or being involved with their murders in any way, Defendant Ashley Guillard posted numerous TikTok (and later YouTube) videos falsely claiming that Plaintiff (i) had an extramarital, same-sex, romantic affair with one of the victims; and then (ii) ordered the four murders to prevent the affair from coming to light….

Plaintiff asserts two defamation claims against Defendant: one is premised upon the false statements regarding Plaintiff's involvement with the murders themselves, the other is premised upon the false statements regarding Plaintiff's romantic relationship with one of the murdered students.

On June 6, 2024, the Court granted Plaintiff's Amended Motion for Partial Summary Judgment …. On the issue of liability for Plaintiff's two defamation claims against Defendant, the Court concluded that Plaintiff sufficiently demonstrated the absence of any genuine issue of material fact relating to the falsity of Defendant's statements about her. Id. (after citing evidence, stating: "This is powerful evidence at the summary judgment stage. It not only substantiates Plaintiff's argument that Defendant's statements about her are false, it also highlights the complete lack of any corroborating support for Defendant's statements.").

Under Rule 56, this shifted the burden to Defendant to dispute that claim by setting forth facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial relating to whether her statements about Plaintiff are true. In relying only on her spiritual investigation into the murders, however, the Court concluded that Defendant did not satisfy her burden. Id. ("As a result, Defendant's psychic intuition, without more, cannot establish a genuine dispute of material fact to oppose Plaintiff's summary judgment efforts."). The Court therefore concluded that "the totality of the evidence reveals that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact that Defendant defamed Plaintiff."

Also on June 6, 2024, the Court granted Plaintiff's Motion for Leave to Amend Complaint to Add Punitive Damages. In permitting a claim for punitive damages, the Court concluded that Plaintiff "established a reasonable likelihood of proving, by clear and convincing evidence, that Defendant's conduct in accusing Plaintiff of an affair with a student before ordering that student's and three other students' murders was oppressive, fraudulent, malicious, and/or outrageous." The extent of Plaintiff's damages, if any, remains an issue for trial.

Defendant moved to reconsider, but the court said no:

Defendant claims that newly discovered evidence (in the form of filings in a related state court criminal proceeding) "provides factual support that substantiates the Tik-Tok videos [Defendant] posted regarding the murder of the four University of Idaho students …." Defendant maintains that she cannot be found liable for defamation because this newly discovered evidence proves that she was telling the truth in these Tik-Tok videos, or otherwise highlights outstanding issues of material fact that precludes summary judgment…..

Defendant argues that newly discovered evidence—revealed in a parallel criminal proceeding in state court—tracks statements made in her earlier Tik Tok videos about various circumstances surrounding the murders. For example, Defendant claims that newly discovered evidence confirms her statements about (i) how the surviving roommates were afraid the night of the murders; (ii) a dog being in the house at the time of the murders; (iii) a break-up involving one of the victims and her boyfriend; (iv) the four victims being located in two different rooms; and (v) the imminence of an arrest. From this, Defendant contends that the perceived synergy between her psychic intuition and the newly discovered evidence not only validates her separate statements about Plaintiff's role in the murders and relationship with one of the victims, but also highlights how her theories about the murders have never been proven false, and therefore her absolute defense of truth against Plaintiff's defamation claims remains plausible….

[But] the evidence does not change the disposition of the case. Absolutely nothing about this evidence suggests that Defendants' statements about Plaintiff are true. That certain of Defendant's psychic insights may have randomly coincided with banal aspects of notorious and well-publicized murders is hardly surprising. But this happenstance alone does not legitimize Defendant's perceived clairvoyance, nor can it bridge the gap between Defendant's intuition and the truth—a crucial aspect of Plaintiff's defamation claims against Defendant. Ultimately, the cited evidence is wholly unrelated to Plaintiff; if anything, it underscores that there continues to be no evidence that Plaintiff had an affair with a student or orchestrated the murders to keep that affair secret.

Defendant's insistence about how her theories surrounding the murders have never been proven false is likewise unavailing. She claims that evidence pertaining to three sets of DNA under M.M.'s fingernails, the victims' defensive wounds, and blood at the crime scene from two unidentified males, is not inconsistent with her underlying theory that Plaintiff orchestrated the murders and framed Brian Kohberger (the defendant in the state criminal action) by planting a knife sheath at the crime scene. But this misses the point. As the Court already stated, this case is not about whether Mr. Kohberger committed the murders…. "Though the Court's consideration of those issues may have touched upon a matter of criminal concern in a parallel criminal proceeding in state court, the Court never endeavored to apply the elements of murder and adjudge Plaintiff "innocent" and Mr. Kohberger "guilty." ….

Rather, this case is about whether Defendant defamed Plaintiff by repeatedly accusing Plaintiff of an affair with a student before ordering that student's and three other students' murders. On that lynchpin point, the Court concluded that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact that Defendant did so, regardless of whether Mr. Kohberger—or anyone else—committed the murders. The evidence that Defendant cites in support of her Motion does not change this conclusion because there continues to be no corroborating support for Defendant's statements about Plaintiff.

Cory Michael Carone and Wendy Olson (Stoel Rives, LLP) represent Schofield.

The post Plaintiff's Idaho Murder Libel Claim Continues to Beat Defendant's "Psychic Intuition" appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] Checking A Presidential Bully

[Do Congress and the courts have adequate tools to rein in Trump’s scattershot use of executive power?]

[This is a guest blog from a friend and colleague, Abner S. Greene, who is the Leonard F. Manning Professor at Fordham Law School and has been following the constitutional separation-of-powers issues at the heart of many of the current cases involving the scope of President Trump's powers for many years.]

Donald Trump's aggressive use of executive power in his second term threatens to upset the balance of power between President and Congress, and although courts have pushed back against Trump's excesses, up-front hurdles and back-end limits render courts an imperfect check. In this essay I will describe an argument I made 30 years ago about the problem of expanded presidential power, explain the hurdles facing my suggestions for a better balance of executive-legislative power, discuss the limits of congressional power to check an unhinged President, and outline some difficulties with relying on courts to save the day.

In 1994, I published a law review article called "Checks and Balances in an Era of Presidential Lawmaking." I examined the records of the 1787 constitutional convention and looked closely at the Federalist Papers. From these materials, I concluded that "the framers were overwhelmingly concerned with either political branch aggrandizing its own power without sufficient checks. To the extent that there is any 'original understanding' of the division of power between the President and Congress, it is that both are to be feared, neither is to be trusted, and if either one grows too strong we might be in trouble."

The article than zoomed forward to the post-New Deal era, where we have seen an enormous expansion of presidential power, sometimes from congressional delegations of power but other times without clear constitutional or statutory authorization. Some of these presidential power-grabs are increases in foreign affairs or war power (e.g., attacking foreign nations without congressional authorization), while others are exercises of domestic policymaking without congressional approval, for example, dismantling a cabinet department, which one would think needs a statutory basis. In part to provoke discussion, I referred to such domestic policymaking actions – which seem to have the force of law – as lawmaking. Understanding modern presidential power assertions in this way helps us see how far things have come since 1787.

I then examined several ways in which we might bring the Congress-President relationship back into the kind of balance the framers envisioned. One angle was to support congressionally created independent agencies, where the heads may not be fired by the President except for good cause. But in the intervening 30 years, the Supreme Court has increasingly (and incorrectly) cut back on Congress' power to create such agencies, asserting that they improperly take executive power from the President. Another angle was to argue for congressional power to act through bicameralism (i.e., majority support in both houses of Congress) but not presentment (i.e., without need to present a Bill to the President for his approval and signature), in situations where the House and Senate deem a presidentially supported regulation beyond the scope of statutory delegation. This would involve overruling INS v. Chadha, which nixed such a "legislative veto" for not following proper Article I, section 7 process, and although I still support this move as a proper translation of how the framers would have wanted balanced power in today's world, I recognize that the U.S. Supreme Court is unlikely to overrule Chadha.

Although Chadha has been mostly important for taking away unilateral congressional power to reject administrative regulations, we should appreciate that it also stands in the way of what could be an effective congressional check on Trump. Congress has limited power to respond to a President who behaves as a bully by issuing commands without authority. It can hold hearings. It can negotiate with the President over whether to amend or repeal extant legislation, and it can similarly negotiate with him about appropriations moving forward. Sometimes – rarely – it will have veto-proof majorities to insist on its priorities. But what it cannot do is respond by itself to presidential orders that appear to be unauthorized. This is sometimes misunderstood, as in when we hear someone say "Congress is feckless! It should do something about Trump! Where are those civic-minded Republicans?" Maybe the person saying this is talking about desired speech acts from members of Congress, or hearings, but my sense is that people are sometimes calling for Congress to act, as a body, to push back against Trump. But Congress has no power to act – with legal consequences – by itself; the Chadha decision forbids this kind of action.

So other than whatever power the press and the people can muster up, we are left with the courts. But there are (at least) four hurdles here. First, Trump forces others to find a lawyer and, unless one can find pro bono counsel, to pay the lawyer. Second, the time Trump has forced on others is unrecoverable, and the attorney's fees are as well, since we live in a country with a strong presumption against attorney's fees shifting. Even if one wins an easy case, the money spent on the lawyer is gone. Third, litigation takes time, even in the best of cases, and even when Federal District Courts have ruled against Trump, circuit courts and the Supreme Court have sometimes stayed the District Court order, with a metric that, although (somewhat) clearly stated, is hard to apply consistently. Fourth, is Trump obeying court orders against him? In some cases it seems he is not. Do courts have adequate powers to punish and deter presidential disobedience of their orders? Do Trump and his agents fear jail time for contempt of court, or monetary fines? And consider that there is a proposal on the table in Congress to limit the power of courts to hold the executive in contempt.

We have come a long way from a framing generation that sought to provide a structure in which legislative and executive power would balance each other out, with courts as backstops. Presidential lawmaking, as I have dubbed it, precedes Trump, but the aggressive use of often unauthorized power is something that Trump, shameless as ever, appears to proudly own. Although Congress and the courts have authority to face down a presidential bully, these bodies must be willing to take what is sometimes courageous action, in the face of legal limits and practical hurdles. We will see in the coming weeks and months whether the Constitution – with its "constant aim [of] divid[ing] and arrang[ing] the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other" – provides sufficient counterbalances against a President acting with disregard for constitutional structure.

Below is a sampling of Federal District Court orders against Trump that have not been stayed or reversed on appeal. See, e.g., Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP v. Executive Office of the President (executive order targeted at law firm; D. D.C. May 27, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278933/gov.uscourts.dcd.278933.110.0_4.pdf; D.V.D. v. U.S. Dep't of Homeland Sec. (deportation; D. Mass. May 23, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.282404/gov.uscourts.mad.282404.132.0.pdf; Jenner & Block v. U.S. Dep't of Justice (executive order targeted at law firm; D. D.C. May 23, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278932/gov.uscourts.dcd.278932.138.0_6.pdf; American Fed'n of Govt't Employees v. Trump (reduction in force at federal agencies; N.D. Cal. May 22, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cand.448664/gov.uscourts.cand.448664.124.0.pdf; New York v. McMahon (dismantling of Department of Education; D. Mass. May 22, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.281941/gov.uscourts.mad.281941.128.0.pdf; Doe v. Trump (deportation; N.D. Cal. May 22, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cand.447674/gov.uscourts.cand.447674.50.0_1.pdf; Association of Am. Univs. v. Department of Energy (higher education cap on indirect funding costs; D. Mass. May 15, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.283318/gov.uscourts.mad.283318.62.0.pdf; American Bar Ass'n v. U.S. Dep't of Justice (termination of grants to the ABA; D. D.C. May 14, 2025), https://ecf.dcd.uscourts.gov/cgi-bin/show_public_doc?2025cv1263-28; American Foreign Serv. Ass'n v. Trump (exclusion of federal workers from collective bargaining; D. D.C. May 14, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.279230/gov.uscourts.dcd.279230.37.0.pdf; Rhode Island v. Trump (reduction in force at federal agencies, and funds termination; D. Mass. May 6, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.rid.59257/gov.uscourts.rid.59257.57.0_2.pdf; Perkins Coie LLP v. U.S. Dep't of Justice (executive order targeted at law firm; D. D.C. May 2, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278290/gov.uscourts.dcd.278290.185.0_1.pdf; Community Legal Servs. in East Palo Alto v. U.S. Dep't of Health & Human Servs. (withholding of appropriated federal funds; N.D. Cal. April 29, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cand.447078/gov.uscourts.cand.447078.87.0_3.pdf; City and County of San Francisco v. Trump (withholding funds from sanctuary cities; N.D. Cal. April 24, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cand.444175/gov.uscourts.cand.444175.111.0.pdf; National Educ. Ass'n v. U.S. Dep't of Education (DEI and federal funding; D. N.H. April 24, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.nhd.65138/gov.uscourts.nhd.65138.74.0_1.pdf; Orr v. Trump (transgender applicants for passports; D. Mass. April 18, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.280559/gov.uscourts.mad.280559.74.0_1.pdf; American Fed'n of State, County, and Municipal Employees v. Social Security Admin. (privacy, information access; D. Md. April 17, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.577321/gov.uscourts.mdd.577321.146.0.pdf; Climate United Fund v. Citibank N.A. (withholding of appropriated federal funds; D. D.C. April 16, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278196/gov.uscourts.dcd.278196.89.0.pdf; Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council v. U.S. Dep't of Agriculture (withholding of appropriated federal funds; D. R.I. April 15, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.rid.59116/gov.uscourts.rid.59116.45.0.pdf; Chicago Women in Trades v. Trump (DEI certification, and funds termination; N.D. Ill. April 14, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ilnd.473983/gov.uscourts.ilnd.473983.68.0_1.pdf; League of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Trump (federal elections rules; D. D.C. April 14, 2025), https://ecf.dcd.uscourts.gov/cgi-bin/show_public_doc?2025cv0946-104; Abrego Garcia v. Noem (deportation; D. Md. April 6, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.578815/gov.uscourts.mdd.578815.31.0.pdf, substantially affrirmed by Noem v. Abrego Garcia (U.S. S. Ct. April 10, 2025), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a949_lkhn.pdf; Associated Press v. Budowich (curtailment of AP access; D. D.C. April 8, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.277682/gov.uscourts.dcd.277682.46.0_1.pdf; Doe v. Bondi (prison facilities, transgender persons; D. D.C. March 19, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.276959/gov.uscourts.dcd.276959.68.0_3.pdf; State of New York v. Trump (withholding of appropriated federal funds; D. R.I. March 6, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.rid.58912/gov.uscourts.rid.58912.161.0_2.pdf; Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. National Insts. of Health (cap on indirect funding costs; D. Mass. March 5, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.280590/gov.uscourts.mad.280590.105.0_2.pdf; State of Washington v. Trump (funds, transgender medical care; W.D. Wash. February 28, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.wawd.344459/gov.uscourts.wawd.344459.233.0_4.pdf; National Council of Nonprofits v. Office of Mgmt. and Budget (withholding of appropriated federal funds; D. D.C. February 25, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.276842/gov.uscourts.dcd.276842.51.0.pdf; O. Doe v. Trump (birthright citizenship; D. Mass. February 13, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.279895/gov.uscourts.mad.279895.144.0_1.pdf.

Abner S. Greene, Checks and Balances in an Era of Presidential Lawmaking, 61 U. Chi. L. Rev. 123 (1994). https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol61/iss1/3/

Id. at 125.

For some examples, see https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/articles/article-i/clauses/753.

See New York v. McMahon (dismantling of Department of Education; D. Mass. May 22, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.281941/gov.uscourts.mad.281941.128.0.pdf.

See Greene, supra note ii, at 176.

See, e.g., Collins v. Yellen, 594 U.S. 220 (2021); Seila Law LLC v. CFPB, 591 U.S. 197 (2020). See also Trump v. Wilcox (May 22, 2025) (Supreme Court order staying lower court orders that would have protected heads of independent agencies from at-will presidential removal; suggesting that Court might be about to rule that all independent agencies are unconstitutional (or most, perhaps excepting the Federal Reserve)), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a966_1b8e.pdf.

Greene, supra note ii, at 187-95.

462 U.S. 919 (1983). Chadha itself involved a one House (rather than bicameral) "veto" that would result in deporting an individual. As Justice Powell's concurrence in the judgment correctly saw, this looks like Congress giving itself (or part of itself) a kind of adjudicative power, which it surely lacks. Chadha also applies to "legislative vetoes" of regulations. This kind of veto doesn't have the problem of looking like adjudication; they look like legislation, but since done without presentment to the President, the Court also ruled them unconstitutional. See Process Gas Consumer Grp. v. Consumer Energy Council of Am., 463 U.S. 1216 (1983) (summary affirmance).

The ruling had a significant impact. It "sounded the death knell for nearly 200 other statutory provisions in which Congress has reserved a 'legislative veto.'" 462 U.S. at 967 (White, J., dissenting).

U.S. Const. Art. I, § 7 ("Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States; If he approve he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated, who shall enter the Objections at large on their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it. If after such Reconsideration two thirds of that House shall agree to pass the Bill, it shall be sent, together with the Objections, to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if approved by two thirds of that House, it shall become a Law.").

Another angle on reducing presidential power and recovering congressional power is for Congress to delegate less open-ended power to the President, and/or legislate more precisely. For many years, the Court has not enforced the so-called "nondelegation doctrine," which prevents Congress from writing laws in a way that appears to delegate legislative power to the President. The Roberts Court might begin reenforcing the nondelegation doctrine. See Gundy v. United States, 588 U.S. 128 (2019) (three dissenting Justices suggest such a course). See also FCC v. Consumers Research (Nos. 24-354 and 24-422; nondelegation doctrine question pending at Supreme Court after briefing and oral argument).

The Court has arguably begun sneaking in some nondelegation doctrine invalidations of (or pruning of) statutes through its use of the "major questions doctrine." See, e.g., Biden v. Nebraska, 600 U.S. 477 (2023); West Virginia v. EPA, 597 U.S. 697 (2022); Department of Homeland Sec. v. Regents of the Univ. of California, 591 U.S. 1 (2020). Here, the Court refuses to allow readings of statutes that would permit administrative resolution of major questions without clearer guidance from Congress in the governing statute. Whether the major questions doctrine constitutes a stealth reinvigoration of the nondelegation doctrine is a disputed matter. See, e.g., Biden, 600 U.S. at 507 (Barrett, J., concurring); West Virginia, 597 U.S. at 735 et seq (Gorsuch, J., concurring); Gundy, 588 U.S. at 149 (Gorsuch, J., dissenting). It will be interesting to see if the Court applies the major questions doctrine to some of Trump's broad assertions of power under less than clear statutory authorization. For a lower court that has just done so, see V.O.S. Selections, Inc. v. The United States of America (invalidating tariffs; U.S. Ct. Int'l Trade, May 28, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cit.17080/gov.uscourts.cit.17080.55.0.pdf.

Similarly, the Senate can threaten to refuse to confirm presidential nominations or ratify treaties.

Musings about Congress' power to act – either via the kind of legislative veto that Chadha rejects, or through standard Article I, section 7 bicameralism and presentment – may seem fanciful at a moment when Congress appears supine before a presidential bully. Nonetheless, it's worth pondering the powers available to and the limits that would confront an effective and willing Congress.

I don't mean to downplay such powers here. They may be key to stopping Trump's excesses. They're just not the focus of this essay.

See, e.g., Merrill v. Milligan, 142 S. Ct. 879, 880 (2022) (per curiam grant of stay) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring) (applicant to Supreme Court for stay of lower court judgment "ordinarily must show (i) a reasonable probability that this Court would eventually grant review and a fair prospect that the Court would reverse, and (ii) that the applicant would likely suffer irreparable harm absent the stay…. In deciding whether to grant a stay pending appeal or certiorari, the Court also considers the equities (including the likely harm to both parties) and the public interest."); see also id. at 883 n.1 (Kagan, J., dissenting) ("A stay pending appeal is an "extraordinary" remedy"; "The applicant … bears the "especially heavy" burden of proving that such relief is warranted"; "Our stay standard asks (1) whether the applicant is likely to succeed on the merits, and (2) whether the likelihood of irreparable harm to the applicant, the balance of equities, and the public interest weigh in favor of granting a stay.").

See, e.g., D.V.D. v. Department of Homeland Sec. (deportation; D. Mass. May 21, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.282404/gov.uscourts.mad.282404.118.0_1.pdf; Abrego Garcia v. Noem (deportation; D. Md. April 11, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.578815/gov.uscourts.mdd.578815.61.0_3.pdf; State of New York v. Trump (frozen federal funds; D. R.I. February 10, 2025), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.rid.58912/gov.uscourts.rid.58912.96.0_2.pdf.

Trump himself might not. See Trump v. United States, 603 U.S. 593 (2024) (granting President absolute immunity for some official acts and at least qualified ("presumptive") immunity for other official acts).

119th Congress, "H.R. 1 § 70302. RESTRICTION ON ENFORCEMENT. No court of the United States may enforce a contempt citation for failure to comply with an injunction or temporary restraining order if no security was given when the injunction or order was issued pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c), whether issued prior to, on, or subsequent to the date of enactment of this section."

One might offer a fifth and sixth hurdle: Courts do not have the power to enforce contempt sanctions themselves; they must rely on executive branch actors. Thus, the President might thwart effective enforcement of contempt sanctions, and also (arguably) might pardon those held in contempt of a federal court order. For some questions about this, see https://verdict.justia.com/2017/08/31/presidential-pardon-power-may-not-absolute.

Federalist 51 (Madison), https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library/detail/james-madison-federalist-no-51-1788.

The post Checking A Presidential Bully appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "AI and the Death of Literary Criticism"

A very interesting piece by Prof. Thomas Balazs in Quillette. An excerpt:

When ChatGPT can analyse Hamlet as well as any grad student, we might reasonably ask, "What is the point of writing papers on Hamlet?" Literary analysis, after all, is not like building houses, feeding people, or practising medicine. Even compared to its sister disciplines in the humanities (e.g., history or philosophy) the study of literature serves little practical need. And, besides, when machines can build houses as easily as people, we won't need people to build houses either.

So, why do we teach English literature (or "language arts," as some secondary schools now call it) at all? According to the nineteenth-century British literary critic Mathew Arnold, the purpose of studying and teaching literature is "to know the best that is known and thought in the world, and by in its turn making this known, to create a current of true and fresh ideas." … English literature was, in truth, a substitute for religion. We wanted people to be good, but we no longer believed in God. Instead, we believed in Shakespeare, Milton, and eventually Toni Morrison. Until we didn't.

It's always been problematic, though, this idea that literature makes you a better person. Besides the obvious counterfactuals—the allied soldiers allegedly found copies of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's works in the desk drawers of Nazi prison guards when they liberated the camps—there were the problems that always arise when you try to push your religion on other people.

Our religion was literature, and like any people of true faith, we deeply believed in it, thought it was essential, thought everyone must be saved through it. The remarkable thing was that we somehow convinced American college presidents of the idea, but then again, many of them, like University of Chicago president Robert Hutchins, creator of the "Common Core" and advocate of "Great Books," were members of the same religion. Not all countries make students of mathematics and engineering take literature courses, but in the United States we do. So for nearly a century, we evangelised our religion to college students, some of whom were already in love with reading and therefore happy to worship at the Temple of Literature. Many were not, but, nonetheless, we rammed Shakespeare, Herman Melville, and Toni Morrison down their throats—to make them better people.

That doesn't mean that it necessarily stayed with them…. Some students of the right temperament and with the right intellectual predilections are drawn to the Temple of Literature, but most are not. For most, it is like going to Sunday school—they endure it reluctantly and quickly forget any lessons learned.

But that's just an excerpt; here's the whole thing.

The post "AI and the Death of Literary Criticism" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: May 31, 1860

5/31/1860: Justice Peter Daniel's death.

Justice Peter Daniel

Justice Peter DanielThe post Today in Supreme Court History: May 31, 1860 appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers