Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 94

May 24, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Thoughts on the Oral Argument in the Oregon Case Against Trump's IEEPA Tariffs

[Like that in the similar case filed by Liberty Justice Center and myself, this one indicated judicial skepticism of Trump's claims to virtually unlimited power to impose tarifs.]

(NA)

(NA) On May 21, The US Court of International Trade (CIT) held oral arguments in Oregon v. Trump, a case challenging Trump's massive IEEPA tariffs filed by twelve states led by the state of Oregon. The Oregon case is similar to that filed by the Liberty Justice Center and myself on behalf of five US businesses harmed by the tariffs, though there are some distinctions (see here for a more detailed discussion).

I won't try to go over the entire two hour argument here. Interested readers can listen to the audio available at the CIT website. And, as always, it is difficult to predict judicial decisions based purely on oral arguments. But I will say that, as in the argument in our case on May 13, the judges seemed highly skeptical of the government's claim that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) gives the president virtually unlimited power to impose tariffs. Judge Restani repeatedly noted that the government's position would allow the president to declare an "emergency" for any "crazy" reason, and then impose whatever tariffs he wanted. In response to the government lawyer's assertion that the delegation of nearly boundless tariff authority was clear enough to satisfy the requirements of the major questions doctrine (a key issue in the case for reasons I describe here), Judge Restani said "[w]e're having a lot of argument for something that's clear" and that "It's not clear to everybody." Amen.

Unlike the argument in our case, this one included some discussion of the scope of the remedy should the plaintiffs prevail. Should there be a nationwide injunction against the tariffs, or one limited to the plaintiffs? I could easily be wrong about this. But it seemed to me the judges were leaning towards s broader remedy. The judges also asked about the standing of the states, especially those who do not directly import goods subject to the tariffs. This issue did not come up in our case, as all our clients are businesses that directly import.

In my view, if even one state is entitled to standing (as Oregon likely is, based on their direct importation), the same goes for the rest, based on the "standing for is standing for all" rule recently applied by the Supreme Court in Biden v. Nebraska (the red state lawsuit challenging Biden's student loan forgiveness program). The Court ruled Missouri had standing, and therefore there was no need to consider whether the other state plaintiffs did.

At one point, the government's lawyer complained that an injunction against the tariffs would "kneecap the president" in his efforts to use the tariffs as leverage against our trading partners. I say the kneecapping would be a feature, not a bug. The Constitution requires a trade system based on the rule of law, not the whims of one man able to impose tariffs whenever he feels like it, in hopes that they might be useful leverage. Otherwise, consumers, investors, and businesses like our clients won't have the stable legal regime they need to make plans and function effectively. I develop these and related points in more detail in my Lawfare article, "The Constitutional Case Against Trump's Trade War," and my post on why Trump's tariffs threaten the rule of law.

While there is no set schedule for the court to issue its decisions in either our case or Oregon's, I would not be surprised if they come relatively quickly. I would also expect them to be issued at the same time, or in close succession.

The post Thoughts on the Oral Argument in the Oregon Case Against Trump's IEEPA Tariffs appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Judge James Ho's Concurrence in the Fifth Circuit Library Decision: Positive Rights vs. Negative Rights

An excerpt from Judge Ho's concurrence in the Little v. Llano County en banc decision (he also joined the majority opinion as to listener interests and the seven-judge decision as to library curation decisions being government speech):

The Constitution protects "the freedom of speech." That freedom ensures that citizens are free to speak—not that we may force others to respond. It's the First Amendment, not FOIA.

So "[t]here is … no basis for the claim that the First Amendment compels others—private persons or government—to supply information." The Supreme Court "has never intimated a First Amendment guarantee of a right of access to all sources of information within government control." "The First and Fourteenth Amendments do not guarantee the public a right of access to information generated or controlled by government."

Our Founders enacted a charter of negative liberties. "[L]iberty in the eighteenth century was thought of much more in relation to 'negative liberty'; that is, freedom from, not freedom to." …

The fundamental distinction between negative and positive rights is essential to a proper understanding of the First Amendment.

Consider how the law treats public museums. It's well understood that you have no First Amendment claim just because a public museum won't feature the art or exhibit you wish to view. That's because, as today's en banc majority opinion explains, when a government funds and operates a museum, it necessarily acts as a curator for the public's benefit—and there is no First Amendment claim when the government is curating, not regulating.

So a public museum "may decide to display busts of Union Army generals of the Civil War, or the curator may decide to exhibit only busts of Confederate generals. The First Amendment has nothing to do with such choices." PETA v. Gittens (D.C. Cir. 2005). See also, e.g., Pulphus v. Ayers (D.D.C. 2017) (rejecting First Amendment claim by an artist challenging the removal of his painting from a Congressional art competition); Raven v. Sajet (D.D.C. 2018) (rejecting First Amendment claim to require display of a portrait of the then-President-Elect at the National Portrait Gallery).

That should end this case, because I see no principled First Amendment distinction between public museums and public libraries.

And neither do Plaintiffs. During oral argument, counsel for Plaintiffs was given repeated opportunities to draw a distinction between public museums and public libraries for purposes of First Amendment analysis. They repeatedly declined to do so. They didn't, because they can't….

The dissent appears to accept that the freedom of speech embodies negative, not positive, rights. The dissent focuses instead on a different distinction. It theorizes that the First Amendment does not require a public library to buy certain books—but it does forbid a public library from removing them, having already bought them. As the dissent puts it, it's "not an affirmative right to demand access to particular materials," but rather "a negative right against government censorship." So "[t]he First Amendment does not require Llano County either to buy and shelve … or to keep [certain books]; but it does prohibit Llano County from removing [them]."

But I confess that I have trouble locating in the First Amendment a distinction between refusing to purchase certain books (which the dissent would allow) and removing them (which the dissent would condemn).

Consider how we would treat the proposed distinction in other constitutional contexts. Does the Fourteenth Amendment allow a government agency to refuse to hire people based on their race—just so long as they don't fire people based on their race? Does the Free Exercise Clause permit a public park to exclude all Christians from entry—it just can't kick them out once they've been let in? Obviously not. No one would draw those distinctions. And the same logic should apply here. If viewpoint discrimination is forbidden, then viewpoint discrimination is forbidden.

So it's not surprising that Plaintiffs appear to concede that they would forbid public libraries from refusing to purchase as well as remove certain books.

I also wonder about the workability of the proposed distinction. Imagine that someone donates their book collection to a local library upon their death. But it turns out that the collection contains some of the material at issue in this case. So the library declines to accept those particular items. Is that refusing to purchase (and therefore permitted)? Or is that removing (and therefore forbidden)? Suppose the entire book collection has already been boxed up, so the estate administrator tells the librarian to either take the entire collection or refuse it whole. So the librarian can't accept custody of certain books while declining others—it can only remove those books after accepting them. Does that make a difference? Why should it?

It seems more principled to me to conclude that the First Amendment permits all of this, because like public museums, public libraries have to make decisions about which materials to include in, and exclude from, their collections. I'm sure we could all find ways to quibble with how a particular library or museum curates their collections. But curators are not regulators. And I have difficulty determining which curating decisions are subject to scrutiny, and which are exempt, consistent with the text and original understanding of the First Amendment….

Plaintiffs have a First Amendment right to read books. They don't have a First Amendment right to force a public library to provide them….

The post Judge James Ho's Concurrence in the Fifth Circuit Library Decision: Positive Rights vs. Negative Rights appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Seven Fifth Circuit Judges on Public Library Selection and Curation Decisions as Government Speech

As I noted yesterday, a ten-judge Fifth Circuit majority held that the Free Speech Clause doesn't secure a right of readers to access material in a public library, and thus generally doesn't constrain public library selection and removal decisions. But seven of the ten judges in the Fifth Circuit (led by Judge Kyle Duncan) also argued that the government speech doctrine provides a separate basis for this decision; the seven judges in the dissent disagreed. This government speech reasoning thus isn't a binding precedent on the question, but it will doubtless come up in other circuits, and in the Supreme Court if the Court agrees to hear the case (perhaps because of the circuit split between the Fifth and Eighth circuits):

"[T]he Free Speech Clause … does not regulate government speech." … [W]hen Llano County shapes its library collection, choosing some books but not others, is the county itself speaking or is the county regulating private speech?

The judges began by citing cases in which the Court recognized that private entities—social media platforms curating their news feeds (see last Term's Moody v. Netchoice), parade organizers choosing floats, newspapers choosing what submissions to publish, and so on—often speak by "present[ing] a curated collection of third-party speech." "Deciding on the third-party speech that will be included in or excluded from a compilation—and then organizing and presenting the included items—is expressive activity of its own." Moody. And, they reasoned,

Like a private person, a government may express itself by crafting and presenting a collection of third-party speech. See, e.g., Ark. Educ. Television Comm'n v. Forbes (1998) ("When a public broadcaster exercises editorial discretion in the selection and presentation of its programming, it engages in speech activity."). A key precedent illustrating this point is City of Pleasant Grove v. Summum (2009), [where] … the City created displays in a public park by accepting privately donated monuments …. The City's selecting some monuments over others[, the Court held,] "constitute[s] government speech." It did not matter that the monuments were works by private sculptors. The relevant expression was the City's choosing the ones it wanted. The City could "express its views," [and thus could pick and choose which monuments to accept -EV,] the Court explained, even "when it receives assistance from private sources for the purpose of delivering a government-controlled message."

Summum maps neatly onto our case. Just as the City of Pleasant Grove selected private speech (monuments) and displayed that speech in a park, the Llano County library selects private speech (books) and features them in the library. The relevant expression lies not in the monuments or the books themselves, but in the government's selecting and presenting the ones it wants. And in both cases the government sends a message. Pleasant Grove said, "These monuments project the image we want." Llano County says, "These books are worth reading."

Plaintiffs object that, while a City's selecting monuments for a park is an expressive act, a library's selecting books for a library does not convey "any particular message to the public." We disagree….

In sum, Supreme Court precedent teaches that someone may engage in expressive activity by curating and presenting a collection of someone else's speech. Governments can speak in this way no less than private persons.

Take any public museum—say, the National Portrait Gallery. The Gallery selects portraits and presents them to the public. Its message is: "These works are worth viewing." A library says the same thing through its collection: "These books are worth reading." The messages in both cases are the government's.

{Plaintiffs … suppose that the claimed government speech here is merely a library's "warranting" that books "are of a particular[] quality." Not so. A library selects books it thinks suitable, buys them with public funds, and presents a curated collection to the public. That is the "expressive activity" at issue, not merely the government's putting its seal of approval on a book.}

The seven judges concluded that Matal v. Tam (2017) didn't preclude their conclusion that library curation decisions are government speech:

In Matal, the federal Patent and Trademark Office ("PTO") refused to place a rock band's name on the principal register because it found the name ("The Slants") was "disparaging" under trademark law. The Supreme Court held this violated the band leader's Free Speech rights by discriminating based on viewpoint…. [But] the claimed government speech [in this case and Matal] is entirely different. Defendants argue that a library speaks by selecting and presenting a collection of books. In Matal, by contrast, the PTO argued the government spoke through the actual content of the marks….

Matal also lacks the expressive elements present here. While a library selects only the books it wants, the PTO does not register only the marks it likes; registering all qualified marks is "mandatory." Similarly, the register is not a curated compilation—rather, it is a listing of millions of marks that "meet[] the Lanham Act's viewpoint-neutral requirements." Nor is the register presented to the public; to the contrary, few people "ha[ve] any idea what federal registration of a trademark means." And, while trademarks have never been thought to convey government messages, libraries' collection decisions (as discussed [below]) have traditionally conveyed the library's view of worthwhile literature.

Finally, Matal's concerns about expanding government speech are not implicated here. The Court worried that, "[i]f federal registration makes a trademark government speech," then someone could say the same about copyright. This case raises no such worry. No one supposes that, by choosing books, the library transforms the books themselves into government speech. The library's speech consists only in presenting a curated collection of books to the public.

They also concluded that the library's collection isn't a "limited public forum," a form of government property where viewpoint discrimination is generally forbidden:

Library shelves are not a community bulletin board: they are not "places" set aside "for public expression of particular kinds or by particular groups." If they were, libraries would have to remain "viewpoint neutral" when choosing books. That would be absurd. Libraries choose certain viewpoints (or range of viewpoints) on a given topic. But they may exclude others. A library can have books on Jewish history without including the Nazi perspective. Forum analysis has no place on a library's bookshelves.

This conclusion is supported by the government speech cases discussed above. Start again with Summum. In addition to ruling that the City was speaking by choosing monuments, the Court also ruled that the City did not create a public forum. Allowing "a limited number of permanent monuments" was not the same as opening the park for "the delivery of speeches [or] the holding of marches." The park obviously had limited space. And it would be absurd to bar the City from engaging in "viewpoint discrimination" when choosing monuments….

And they concluded that the Shurtleff v. City of Boston (2022) didn't preclude this result:

In [Shurtleff], the City of Boston allowed private parties to fly flags of their choosing on the city flagpole. The Supreme Court held the City was not engaging in government speech but instead had created a limited public forum. As a result, the City could not refuse a group's request to fly a "Christian flag" because that would constitute viewpoint discrimination.

In deciding the program was not government speech, the Court considered certain kinds of evidence: "[1] the history of the expression at issue; [2] the public's likely perception as to who (the government or a private person) is speaking; [3] and the extent to which the government has actively shaped or controlled the expression."

All three factors support the conclusion that a library's choice of the books on its shelves is government speech….

[1.] History of the expression

Public libraries, in the modern sense, arose in the United States in the mid-19th century…. [T]he first municipal public library recognized by state statute, the 1848 Boston Public Library, was considered by its Board of Trustees to be "the means of completing our system of public education."

In light of public libraries' avowed educational mission, content selection was critical. For instance, by 1834, the Petersborough Town Library's collection consisted overwhelmingly of historical, biographical, and theological works. Novels, despite their popularity, occupied a mere 2% of the collection. This was no accident: many educators, echoing Thomas Jefferson, found novels "poison[ous]" and "trashy."

The same was true of state libraries. New York's 1835 library law, establishing the first statewide tax-supported library, considered the public library an "educational agency" and charged the state superintendent with creating lists of suitable books. Collections weeded books promoting "improper" morality, with the result that fiction was mostly excluded….

The lesson from this historical sketch is obvious: by shaping their collections, public libraries were speaking, loudly and clearly, to their patrons. "These books will educate and edify you. But the books we have kept off the shelves—trashy novels, for instance—aren't worth your time." …

Today, public libraries convey the same message to the reading public…. Just take a look at the 2012 Texas State Library "CREW" guide. See generally CREW: A Weeding Manual for Modern Libraries. This is the official guide to curating collections in Texas libraries… Public libraries are told to weed the following:

"[B]iased, racist, or sexist terminology or views." "[S]tereotypical images and views of people with disabilities and the elderly, or gender and racial biases." "[O]utdated philosophies on ethics and moral values." "[B]ooks on marriage, family life, and sexuality … [are] usually outdated within five years." "[B]ooks with outdated [political] ideas." "[B]iased or unbalanced and inflammatory items [about immigration]." "[O]utdated ideas about gender roles in childrearing." "Art histories … [with] cultural, racial, and gender biases." "[Children's] books that reflect racial and gender bias" or have "erroneous and dangerous information."Similarly, the American Library Association also advises librarians to remove "items reflecting stereotypes or outdated thinking; items that do not reflect diversity or inclusion; [and] items that promote cultural misrepresentation." For instance, the handbook's chapter on "Diversity and Inclusion" warns librarians that "children's books have overwhelmingly featured white faces" and encourages them to include works that "represent diverse people of different cultures, ethnicities, gender identities, physical abilities, races, religions, and sexual orientation." More specifically, it advises that it is "basic collection maintenance" to "[r]emov[e] the Dr. Seuss books that are purposefully no longer published due to their racist content."

This guidance would be right at home in 1850s Massachusetts. See Jesse H. Shera, Foundations of the American Public Library (1949) (recounting Rep. Wight's 1851 argument that libraries would "diminish[] the circulation of low and immoral publications"). To be sure, today's librarian may have a different idea of what constitutes a "low and immoral publication." But the song remains the same: officials, both in 1851 and 2024, are telling the public which books will "promote virtue, reform vice, [and] increase morality." …

[2.] Public perception

Shurtleff next "consider[ed] whether the public would tend to view the speech at issue as the government's." The answer is yes…. "People know that publicly employed librarians, not patrons, select library materials for a purpose." …

And yet the Eighth Circuit recently reached a different conclusion. In GLBT Youth in Iowa Schools Task Force v. Reynolds (8th Cir. 2024), the court ruled that the public would not "view the placement and removal of books in public school libraries as the government speaking." The panel's reasoning? Given the variety of books on the shelves, if the government were the one speaking, it would be "babbling prodigiously and incoherently." …

[But] the Eighth Circuit misunderstood the government "speech" at issue. It is not "the words of the library books themselves." No one even claims that. As the D.C. Circuit pointed out nearly 20 years ago …, "[t]hose who check out a Tolstoy or Dickens novel would not suppose that they will be reading a government message." A library that includes Mein Kampf on its shelves is not proclaiming "Heil Hitler!" Rather, "the government speaks through its selection of which books to put on the shelves and which books to exclude." …

[3.] Extent of government control

The answer to Shurtleff's third question—"the extent to which the government has actively shaped or controlled the expression"—follows from the first question. As explained, literally from the moment they arose in the mid-19th century, public libraries have been shaping their collections for specific educational, civic, and moral purposes. They still do today….

{Plaintiffs (and the dissent) argue [the government speech] issue was "waived" because defendants did not raise it before the panel. Not so. The issue was raised and ruled on in the district court, ruled on by the panel majority, and thoroughly explored in en banc briefing. So, the issue is before us. In any event, we have discretion to reach the issue.}

{We express no opinion on whether a public library's removal of books can be challenged under other parts of the Constitution. See, e.g., Summum (observing there may be other "restraints on government speech," such as the Establishment Clause).}

Judge Stephen Higginson's dissent (for seven different judges) didn't discuss the government speech doctrine in detail, but here's the excerpt that touches on the subject:

[O]ur court's holding today is incompatible with the "fixed star [of] our constitutional constellation" that "no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion."

By eliminating the public's right to challenge government censorship of public library books, our court's holding becomes a Trojan horse for the government speech doctrine that fails to command a majority in its own name. The majority opinion elucidates no functional difference between its holding that the public has no First Amendment right to challenge the government's removal of public library books, no matter the reason, and its ostensible plurality holding that the government may "speak" by removing library books for any reason, without First Amendment restraint. Turning freedom of speech into government speech is more than a sleight of hand. It results from the majority ignoring preliminary facts found by a district court and repudiating half-century-old Supreme Court authority….

{As counsel for Defendants acknowledged during the en banc oral argument, the majority's "no right to receive" holding collapses into its "government speech" position, creating a circuit split with the Eighth Circuit…. It … unsurprising that this position is not openly embraced by a majority of this court; nor is it surprising that Defendants themselves declined to make this argument at the panel stage, thus waiving the issue despite the primary opinion's assertions to the contrary.

This attempted First Amendment collapse—supplanting free speech with government speech—contradicts multiple Supreme Court decisions. See Matal; Shurtleff. In Shurtleff, the Court explained that the government speech inquiry is a "holistic" one, and that relevant factors include: "the history of the expression at issue"; "the public's likely perception as to who (the government or a private person) is speaking"; and "the extent to which the government has actively shaped or controlled the expression." As explained by the Eighth Circuit, none of these factors supports a conclusion that library book removals constitute government speech. Across multiple "government speech" cases, Justice Alito has emphasized the narrowness of the government speech doctrine and the extreme care with which courts must apply it. See, e.g., Matal (emphasizing that the Supreme Court "exercise[s] great caution before extending [its] government-speech precedents" and warning that the government speech doctrine "is susceptible to dangerous misuse"); Summum (describing as "legitimate" the "concern that the government speech doctrine not be used as a subterfuge for favoring certain private speakers over others based on viewpoint"); Shurtleff (Alito, J., joined by Thomas and Gorsuch, JJ., concurring in the judgment) (writing separately to articulate his view of "the real question in government-speech cases: whether the government is speaking instead of regulating private expression"); id. (admonishing that the government speech doctrine may be "used as a cover for censorship," and that "[c]ensorship is not made constitutional by aggressive and direct application"); id. ("[G]overnment speech occurs if—but only if—a government purposefully expresses a message of its own through persons authorized to speak on its behalf, and in doing so, does not rely on a means that abridges private speech"); id. ("Naked censorship of a speaker based on viewpoint, for example, might well constitute 'expression' in the thin sense that it conveys the government's disapproval of the speaker's message. But plainly that kind of action cannot fall beyond the reach of the First Amendment.").

The post Seven Fifth Circuit Judges on Public Library Selection and Curation Decisions as Government Speech appeared first on Reason.com.

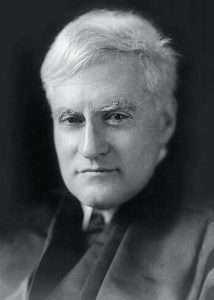

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: May 24, 1870

5/24/1870: Justice Benjamin Cardozo's birthday.

Justice Benjamin Cardozo

Justice Benjamin CardozoThe post Today in Supreme Court History: May 24, 1870 appeared first on Reason.com.

May 23, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Video of National Constitution Center Panel on "The War Over the Constitution's Meaning"

[The participants were Amanda Shanor (Univ. of Pennsylvania), Alan Trammell (Washington and Lee), Wilfred Codrington, III (Cardozo), and myself.]

(NCC)

(NCC) I took part in a recent National Constitution Center panel on "The War Over Constitutional Meaning." The other participants were Prof. Amanda Shanor (Univ. of Pennsylvania), Prof. Alan Trammell (Washington and Lee), and Prof. Wilfred Codrington, III (Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, serving as moderator). Here is the video:

We covered a lot of ground, ranging from the pros and cons of originalism, to whether the Reconstruction amendments are "underrated" to whether we need fundamental constitutional reform. On the latter issue, I made the case that many of our current problems stem not from inherent flaws in the Constitution but from failure to enforce it more fully.

The panel was part of a larger conference on "Constitutional Meaning in the Shadow of the Articles of Confederation." Video of the full conference and the full list of participants (including many prominent legal scholars and Rep. Jamin Raskin, himself a former legal scholar) are available here.

The post Video of National Constitution Center Panel on "The War Over the Constitution's Meaning" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] District Court Declines to Stay Order Reinstating Fired U.S. Institute of Peace Board Members, Holds Trump v. Wilcox Doesn't Apply

From today's order by Judge Beryl Howell (D.D.C.) in U.S. Institute for Peace v. Jackson:

[On Monday, t]his Court declared that President Trump's termination of USIP Board members violated the statutory removal protections in 22 U.S.C. § 4605(f), and because those protections posed no constitutional problem, the terminations were null and void. This Court also declared null and void actions taken as a result of those improper removals, including the removal and replacement of USIP President Ambassador Moose, as well as the transfer of property and other actions taken by those illegitimately installed replacements. This Court then ordered that plaintiff Board members and Ambassador Moose remain in their leadership positions for USIP and may not be treated as having been removed, among other concomitant relief.

Defendants sought a stay of this order while it's being appealed, but the court said no:

Whether a stay is appropriate depends on four factors: "(1) whether the stay applicant has made a strong showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits; (2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay; (3) whether issuance of the stay will substantially injure the other parties interested in the proceeding; and (4) where the public interest lies." "The first two factors of the traditional standard are the most critical," and the showing of likelihood of success must be "substantial."

For all of the reasons explained in this Court's Memorandum Opinion, defendants have not made the requisite showing that they are likely to succeed on the merits. President Trump removed the USIP Board members without complying with the statutory requirements in 22 U.S.C. § 4605(f). Defendants did not argue that the President met those requirements but rather challenged the constitutionality of the statutory removal restrictions, arguing that USIP is part of the Executive branch and its Board members are subject to at-will presidential removal under Article II of the Constitution.

As the Court explained, however, while USIP may be considered part of the federal government, USIP does not exercise executive power and thus is not part of the Executive branch, so the President does not have absolute constitutional removal authority over USIP Board members but must comply with the statute in exercising his removal power. Further, even if USIP were part of the Executive branch, Congress's restrictions on the President's exercise of constitutional removal authority in 22 U.S.C. § 4605(f) would be permissible under Humphrey's Executor v. United States (1935), and its progeny, given USIP's Board's multimember structure and de minimis, if any, exercise of executive power. Thus, whether USIP is or is not part of the Executive branch, the President must comply with the various mechanisms at his disposal, as provided in the statute to remove members of USIP's Board.

Contrary to defendants' suggestion, the Supreme Court's recent stay in Trump v. Wilcox has no bearing here. The Supreme Court there opined that the National Labor Relations Board ("NLRB") and Merit Systems Protection Board ("MSPB") "exercise considerable executive power" and thus invoked concerns about the President's Article II removal power. As explained in the Memorandum Opinion, USIP exercises considerably less executive power than such agencies. USIP is rather a "uniquely structured, quasi- private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States,"—the kind the Supreme Court explicitly noted are not "implicate[d]" by its stay decision.

Defendants insist that the Court erred in concluding that USIP could be part of the government while not falling within one of the three branches. Defendants' cited authorities do not, however, hold that every entity must fall squarely within one of the three branches, and as the Court has previously pointed out, other entities also fall outside of this tripartite structure.

Refraining from classifying USIP as squarely within a particular branch does not make it "unanswerable to the electorate or the Judiciary," as defendants contend. To the contrary, the Institute is highly responsive to both Congress and the Executive branch through numerous oversight mechanisms (including mandatory biennial reporting to both branches), control of appropriations on which the organization is largely dependent, the President's ability to appoint all voting Board members (including two that are part of his Cabinet), and the President's broad—though not limitless—removal authority.

Moreover, defendants' argument that USIP exercises "core executive powers" because the Institute "promot[es] peace and alternatives to war, including by distributing directly appropriated funds to private entities" and "travel[s] to foreign countries and attempt[s] to negotiate peace" is both legally and factually wrong. Those activities are not, as defendants suppose, inherently executive just because they involve foreign relations. As the Court explained, NGOs regularly engage in similar activities. What matters is whether the entity is doing so under the auspices of the President of the United States. USIP neither represents nor acts on behalf of the Executive branch, and instead operates abroad as an independent think tank.

Further, defendants misrepresent the activities USIP undertakes abroad. USIP is a scholarly, research-oriented, educational institution or "think tank." While its focus on peace leads USIP to deliver workshops, conduct field research, and facilitate discussions on the subject of resolving conflicts, the Institute in no way occupies the same role as the Executive branch in formally negotiating foreign agreements. Defendants' overly generic view of Executive power is perhaps convenient, one conducive to aggrandizing presidential authority, but this Court must take a more scrutinizing approach to the nature of executive power under the Constitution and the character of the authority USIP wields.

Defendants next argue that the Court's issuance of injunctive relief was improper but cite only dissenting opinions in support of that point. The questions before this Court were indeed "novel," but novelty is no substitute for failure to demonstrate likelihood of success on the merits. Indeed, defendants' failure to show likelihood of success is "an arguably fatal flaw for a stay application," but regardless, defendants also fail to satisfy the other factors. Defendants do not describe any cognizable harm they will experience without a stay, let alone an irreparable one.

Defendants point to the Wilcox Stay Order to suggest that the government faces a "risk of harm from an order allowing a removed officer" to remain. Yet, the Supreme Court specified that the risk of harm was that of allowing a removed officer to "continue exercising the executive power." Such a risk is not present in this case because, again, the Institute's Board members do not exercise any meaningful executive power under our Constitution. Plaintiffs and the public, on the other hand, experience harm every day that plaintiffs are not able to carry out their statutory tasks and operate USIP with independence and expertise. Cf. New Motor Vehicle Bd. v. Orrin W. Fox. Co. (1977) (Rehnquist, J., in chambers) (describing irreparable harm to the government that occurs "any time" it is unable to "effectuat[e] statutes enacted by representatives of its people"). As plaintiffs explain, every day that goes by without the relief this Court ordered, "the job of putting [USIP] back together by rehiring employees and stemming the dissipation of USIP's goodwill and reputation for independence will become that much harder."

In the alternative, defendants have requested a "two-business-day administrative stay to allow defendants to seek a stay from the D.C. Circuit." Defendants do not provide any separate rationale to warrant such an administrative stay, and none is apparent in light of the equities and public interest just discussed.

The post District Court Declines to Stay Order Reinstating Fired U.S. Institute of Peace Board Members, Holds Trump v. Wilcox Doesn't Apply appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Baude on Trump v. Wilcox: "Predictable and Reasonable"

[A defense of the Supreme Court's decision to let President Trump remove members of the NLRB and MSPB.]

Yesterday, by a vote of 6-3, the Supreme Court stayed district court orders blocking President Trump from removing members of the Gwynne Wilcox from the National Labor Relations Board and Cathy Harris from the Merit Systems Protection Board. As I noted before, this case targeted Humphrey's Executor and had the potential to effectively eliminate independent regulatory agencies as a category.

In today' New York Times, Will Baude has an op-ed largely defending the Court's order as both "predictable and reasonable" that largely captures my views on the subject (thus freeing me from writing a longer blog post on the case). He writes:

We have plenty of things to worry about in constitutional law today. But those worried about how the court will confront the unprecedented and sometimes unlawful actions of the Trump administration should save their outrage for other cases.

In the two cases here, the court held that the president was likely to prevail in his unitary executive claim, that the administration was unduly harmed by allowing the officials to keep their offices while the case was pending, and that this reasoning would not imperil the independence of the Federal Reserve. It did all of this in an emergency order, rather than waiting for the issues to arrive on the court's regular docket.

All four of these things are noteworthy and provoked a powerful dissent by Justice Elena Kagan. But in this particular case, all four can be justified.

It was reasonable for the Court to conclude that the NLRB and MSPB are more like the Consumer Financial Protection Board than they are like the 1930s Federal Trade Commission, and thus limitations on presidential removal of board members conflicted with Seila Law and should not be saved by Humphrey's Executor. Indeed, it is not clear the current FTC would qualify. The "quasi-legislative" functions of the FTC the Court considered important in Humphrey's were the FTC's responsibilities for assisting and informing Congress, not promulgating regulations.

But what about the Federal Reserve? Baude writes:

The court's declaration that the Federal Reserve is different also has a plausible basis. In the decades after the nation's founding, practice and precedent firmly established the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, which operated as a corporation with some independence from the president. This suggests that monetary policy is not necessarily executive power. While the Federal Reserve today does many things beyond its core mission of monetary policy, the court would have several options for preserving at least some independent functions for the Federal Reserve.

I would go a little further and note that all the Court said in its order is that allowing the removal of NLRB and MSPB members does not "necessarily" mean that members of the Federal Reserve Board are also removable. It is simply a separate question, and it may well be the case that the Fed's primary responsibilities (monetary policy) can be insulated from executive control, whereas some of its regulatory functions cannot. Those are all questions courts can sort out another day.

More Baude:

Officially, the court was careful not to completely prejudge the legal issues, nor to state definitively that previous precedents about independent agencies would be narrowed or overruled. It made an honest judgment about the likelihood of success on the merits, as the law calls for.

Even if it had gone further and made such definitive statements, this is not the kind of case where that should especially concern us. It is bad when the emergency docket forces the justices to quickly take positions on tough issues that they have not had time to consider carefully. But the unitary executive question has been before the court multiple times in recent cases, with extensive briefing and argument. All of the justices have thought carefully about the legal issues and made up their minds about most of them.

The president's ruinous tariffs, purported cancellation of birthright citizenship, renditions to foreign prisons and retaliations against his political opponents all raise far graver constitutional problems than the court's ultimately unsurprising order in these cases. We should focus our concern there.

That seems right to me.

The post Baude on Trump v. Wilcox: "Predictable and Reasonable" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Does the Big, Beautiful Bill Contain a Threat to Judicial Independence? (Updated)

[Is it a problem if a provision requires judges to comply with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure?]

The New York Times reports on an ominous provision in the House passed "Big Beautiful Bill" through which Republicans are trying to "weaken federal judges." From the story:

The sprawling domestic policy bill Republicans pushed through the House on Thursday would limit the power of federal judges to hold people in contempt, potentially shielding President Trump and members of his administration from the consequences of violating court orders. . . .

The language in the House-passed bill would block federal judges from enforcing their contempt citations if they had not previously ordered a bond, a provision that Republicans said was intended to discourage frivolous lawsuits by requiring a financial stake from those suing. . . .

Democrats have argued that House Republicans' measure would rob courts of their power by stripping away any consequences for officials who ignore judges' rulings. They also noted that the measure would effectively shield the Trump administration from constitutional challenges by making it prohibitively expensive to sue.

"We've never said to American citizens and constituents that in order to vindicate their rights in federal court, they're going to be required to provide a security when their constitutional rights have been violated by their government," Representative Joe Neguse, Democrat of Colorado, said.

Curious, I looked up the relevant provision in the House-passed bill. It reads:

No court of the United States may use appropriated funds to enforce a contempt citation for failure to comply with an injunction or temporary restraining order if no security was given when the injunction or order was issued pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c), whether issued prior to, on, or subsequent to the date of enactment of this section.

So the issue, then, is what is required by FRCP Rule 65(c). It provides:

The court may issue a preliminary injunction or a temporary restraining order only if the movant gives security in an amount that the court considers proper to pay the costs and damages sustained by any party found to have been wrongfully enjoined or restrained. The United States, its officers, and its agencies are not required to give security.

So it would seem that Rule 65(c) already requires security to be given before such orders issue, subject to the judge's discretion as to what constitutes a "proper" amount.

This has become an issue because many judges use this discretion to set the security amount at zero. From the story:

The amount is supposed to be set at what "the court considers proper" to cover any costs that might be suffered if that injunction is later found to have been incorrectly issued. But federal judges have wide discretion to set their bonds, and often refrain from doing so.

Samuel L. Bray, a Notre Dame law professor, said many judges do not order injunction bonds in cases where people are seeking to stop government actions that they claim are unconstitutional.

"It doesn't wind up getting used as much as it's supposed to," he said, "and it especially doesn't wind up getting used when people sue the federal government."

I'll defer to Prof. Bray on this point, but it seems to me that the common practice of waiving any security is contrary to the rule as written. After all, if the rule were intended to give judges the discretion to set the security amount at zero, might it have been drafted to make requiring security at all a matter of judicial discretion? That is, giving judges discretion to set an amount is not the same thing as giving judges the discretion as to whether to require security at all.

In any event, this may all be moot as it is not clear that this provision will survive the Senate. Among other things, it is not clear how this provision is sufficiently budget-related for a reconciliation bill, but we will see.

UPDATE: It's a good thing I said I'd defer to Prof. Bray, as he was ahead of me in flagging this provision, and notes that it does more than I suggest. Indeed, in a post at Divided Argument he suggests the provision is "underinclusive, overinclusive, and likely unconstitutional." Going forward, judges could effectively evade its requirements by setting the security required at $1. But since the provision is also retroactive, it could blow up all sorts of federal court injunctions on the books (as in school desegregation orders or antitrust remedies). And, most significantly, he suggests the provision "is probably unconstitutional as an attempt to interfere with the inherent power of a court of equity to enforce its decrees with contempt." Duly noted.

The post Does the Big, Beautiful Bill Contain a Threat to Judicial Independence? (Updated) appeared first on Reason.com.

[John Ross] Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal

[Helicopter accidents, nasty feuds, and serial lies.]

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

Not in my backyard! In which IJ goes full NIMBY: IJ client Dalton Boley used to enjoy camping with his three little boys in the 10-acre woods immediately behind his house. That is, until he learned that Alabama game wardens have been spying on them without warrants. On multiple occasions, these armed agents have trespassed onto the property, tampering with Dalton's trail cameras, while ignoring No Trespassing signs. So this week, IJ filed suit on Dalton's (and others') behalf, seeking to vindicate the Alabama Constitution's protections against unreasonable searches and the state's common-law right against trespasses. Click here to learn more. And click here for a special podcast episode explaining why this isn't a Fourth Amendment case.

This week on the Short Circuit podcast: Dirt biking around the nondelegation doctrine and unmooting free speech.

We wish we could tell you if, in 2017, two FBI officials unlawfully leaked info from a classified FISA warrant to the press in order to besmirch the reputation of a Trump adviser. But the D.C. Circuit (over a dissent) says the suit claiming as much is time-barred. North Carolina helicopter pilot dies when his crop-dusting chopper collides with a steel wire strung between a tall pole and a distant tree. Negligence on the part of the farm's owners and the pesticide company that hired the crop-duster? District court: No. The risk posed by the wire wasn't reasonably foreseeable to the defendants, since they're farmers, not pilots. Fourth Circuit: Under North Carolina law, which governs here, summary judgment is basically never appropriate in negligence cases. To trial the case must go! (Your summarist must confess to not being entirely sure the court faithfully applied the Erie doctrine in placing such weight on North Carolina's fondness for jury trials, but … who knows? Not us!) In 2024, the federal gov't entered into a settlement with a certified class of unaccompanied alien children. Under it, the gov't agreed not to remove any class member while his or her asylum applications remained pending. Following President Trump's Alien Enemies Act proclamation, the gov't sends a class member to an El Salvadoran prison. District court: Quit violating the settlement agreement, and "facilitate" getting the guy back. Fourth Circuit (2-1): We cordially deny the gov't's request to stay that order. Widow of assassinated Saudi Arabian journalist and human rights activist Jamal Khashoggi sues Israeli company, alleging that "at least one cell phone she owned and used to communicate with Jamal had been the subject of unlawful surveillance using a technology developed and licensed by" the company, and that "this surveillance culminated in his death." Fourth Circuit: But her allegations are too vague to show that the company did anything in Virginia, where she sued. So no personal jurisdiction. The FCC has been charged by Congress with regulating the broadcast spectrum "in the public interest." Seems kinda vague. Does that mean they can do anything they think is good or useful for the public? Fifth Circuit: It does not. And, in particular, they cannot require broadcasters to disclose employment demographic data, which the FCC wants to post online. Gravity Capital submitted a claim to property that was subject to criminal forfeiture, but their lawyer accidentally signed the petition with the name Gravity Funding, a different entity. No problem, you may be thinking—a signature is anything a party intends to be a signature, the lawyer intended this to be Gravity Capital's signature (it's a claim for a loan made by Gravity Capital, after all), and it's all a silly goof. Fifth Circuit: "There but for the grace of God go I." Your lawyer forfeited your claim. In 1946, Congress passed the Federal Tort Claims Act so that when a mailman causes a car accident, the feds will pay for the damage. (The Act covers other torts, bien sûr, but the mailman is the example that came up in legislative hearings.) Later, in 1974, Congress amended the FTCA so that when federal agents raid the wrong home, the feds are on the hook for damages. (The amendment covers other law-enforcement misconduct, bien sûr, but wrong-house raids were the motivation for the legislation.) Fifth Circuit: Good news in this tragic case; the act still covers postal worker accidents. Editorial comment: And maybe it still covers wrong-house raids, too. We'll have to see what SCOTUS does. Texas associate departs his law firm and also tries to leave with a bundle of clients and files. His former employer is displeased and sues him in state court. Associate moves to dismiss under Texas's anti-SLAPP law and then removes the case to federal district court. District court then remands on the ground that the MTD waived removal. Associate appeals, but under old precedent Fifth Circuit (2024) says it can't review remand orders based on waiver. Fifth Circuit (2025): And as an en banc court we now overrule that old precedent 17-0. Ohio man is convicted of murdering his wife. Yikes! The lead investigator is a serial fabulist, having lied about, among other things, having a master's degree, having been a U.S. Postal Inspector and a Special Forces parajumper. Sixth Circuit (unpublished): His testimony wasn't all that important. Habeas denied. Sixth Circuit: The Eleventh Amendment means never having to say you're sorry—and also that we can resolve the merits of your ADA claim against the state (there are none) while deciding we lack jurisdiction. In which the Seventh Circuit faults a set of plaintiffs for failing to clearly articulate whether their challenge to Cook County, Ill.'s Covid-19-vaccination policy is "facial" or "as-applied." (According to the plaintiffs, the county treated requests for religious exemptions worse than requests for secular exemptions.) Is the Seventh Circuit's complaint reasonable? Quite possibly. Is the distinction between facial and as-applied challenges an absolute mess that might not have been particularly relevant to this case at all? Also, quite possibly. Missouri man is going to trial for dealing meth when he tries to fire his (second) lawyer and defend himself pro se. District court: That's "not a very good decision." Even if you were a lawyer, "pro se is a bad decision." Defendant: Whatever. Court: OK, fine. Defendant is then convicted, receiving 25 years in the slammer. Eighth Circuit: This waiver was not made "knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently". Allegation: Oklahoma City officer pushes calm, handcuffed, and very drunk man on the shoulder so as to nudge him toward paddy wagon. The man falls and breaks his ribs. Tenth Circuit: Accidents happen. Eleventh Circuit: The Eleventh Amendment may not allow federal courts to order the states to pay money, but these plaintiffs haven't asked the state for any money yet, which means federal courts can order the state not to withhold the money when they ask for it. We wish you could tell you if some of The Hollywood Reporter's reporting in its 2020 article entitled "Allegations of Prostitution, Substance Abuse, and Spying: Inside Hollywood's Nastiest Producer Feud" was defamatory or nah. But the Eleventh Circuit says the suit claiming as much is time-barred. And in en banc news, the Fifth Circuit will not reconsider its decision that an appellate waiver in a plea agreement did not cover restitution because the restitution was beyond the "statutory maximum" sentence allowed. Seven judges disagreed and would have granted the en banc petition. But what is the name of the disagreeing opinion they sign onto? Concurrence 1: No mention. Concurrence 2: Dissental. Concurrence 3: Dissent. Dissent(al): Dissent.Victory! In 2022, IJ client Sean Young invited a group of high school art students to design a mural for his bakery's storefront. Within days, however, Conway, N.H. officials ordered him to remove the mural because the students chose to paint muffins, donuts, scones, etc. If the students had instead painted mountains or a covered bridge or literally anything else, no problem. If the exact same mural was painted on a different building in town, no problem. Which is a First Amendment problem, and this week a federal judge ruled that the town's enforcement efforts have "no rational connection to any of its stated interests." Click here to learn more.

Victory! Some weeks back, we obtained TROs barring the feds from undertaking ruinous financial surveillance of money services businesses in Texas and California. And we now have written orders (Texas and California) granting a PIs. And, friends, they're beauts. For example: "While the Government's goal of ferreting out illegal drug money laundering is laudable, the tactic employed here is akin to using a blunderbuss to target a fly, likely wreaking economic destruction on surrounding law-abiding citizens who the facts show are already subject to the 'nth degree' of audits by Internal Revenue Service, Texas bank regulators and other extensive federal reporting requirements, all of which give the Government ample information of suspicious activities. Using proper law enforcement investigation techniques and other information from Currency Transaction Reports already available, the Government could establish probable cause before a neutral judge to obtain a search warrant. This is called Due Process, the violation of which is the revolutionary reason for the Fourth Amendment to our Bill of Rights." Click here to learn more.

The post Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] The Fifth Circuit on Library Selection and Removal Decisions and First Amendment Rights of Listeners

The primary argument supporting a claimed First Amendment prohibition on public libraries' excluding books based on viewpoint was the First Amendment right of listeners. The majority in today's Little v. Llano County en banc decision held that this right doesn't give people an entitlement to have the government provide the materials in the library:

We hold that plaintiffs cannot invoke the right to receive information to challenge the library's removal of the challenged books.

First, plaintiffs would stretch the right far beyond its roots. As discussed, the [Supreme Court's right-to-receive-information precedents] teach that people have some right to receive information from others without government interference.

It is one thing to tell the government it cannot stop you from receiving a book. The First Amendment protects your right to do that. It is another thing for you to tell the government which books it must keep in the library. The First Amendment does not give you the right to demand that.

Second, if people can challenge which books libraries remove, they can challenge which books libraries buy. "[A] library just as surely denies a patron's right to 'receive information' by not purchasing a book in the first place as it does by pulling an existing book off the shelves." For good reason, no one in this litigation has ever defended that position.

Suppose a patron complains that the library does not have a book she wants. The library refuses to buy it, so she sues. Her argument writes itself: "[I]f the First Amendment commands that certain books cannot be removed, does it not equally require that the same books be acquired?" She would be right. This means patrons could tell libraries not only which books to keep but also which to purchase. Could they also sue the county to increase its library fund?

In a footnote, plaintiffs try to distinguish book removals from purchases. They say libraries have "a wider variety of legitimate considerations" for not buying books, such as "cost," and they assert unbought books will "vastly outnumber" removed books.

So what? Plaintiffs can just as easily probe a library's "considerations" for not buying a book as for removing one. Did the library lack funds, or did the librarian dislike the book's views? That's what discovery is for. And it is no answer to say that a failure-to-buy case will be harder to prove than a removal case. Maybe, maybe not. The point is that, once courts arm plaintiffs with a right to contest book removals, there is no logical reason why they cannot contest purchases too.

Third, how would judges decide whether removing a book is verboten? What standard applies? The district court asked whether the library was "substantially motivated" to "deny library users access to ideas" by engaging in "viewpoint or content discrimination." The panel clarified that libraries could remove books that are "[in]accura[te]," "pervasively vulgar," or "educational[ly] [un]suitabl[e]." On en banc, plaintiffs argued the standard was "no viewpoint discrimination." Applying such tests to library book removals would tie courts in endless knots.

Consider one of the challenged books: It's Perfectly Normal, a book for "age 10 and up" that features cartoons of people having sex and masturbating. If the library removed the book because of the pictures, as plaintiffs claim, did it violate the First Amendment? Surely the library wanted to "deny access" to the book's "ideas." So, yes. And surely the library "discriminated" against the book's "content." So, yes again. But the library also deemed the book "educationally unsuitable" for 10-year-olds. So, no. And it likely found the book "vulgar," but perhaps not "pervasively." So, maybe. No surprise, then, that the panel majority split over whether removing It's Perfectly Normal was permitted.

Or consider a hypothetical that came up at oral argument. A library discovers on its shelves a racist book by a former Klansman. See, e.g., David Duke, Jewish Supremacism: My Awakening on the Jewish Question (2003). Can it be removed? If the library deems the book "inaccurate" or "educationally unsuitable," yes. But if the library dislikes its content or viewpoint, no. The problem is obvious: deeming a book "inaccurate" or "unsuitable" is often the same thing as disliking its "content" and "viewpoint." Judges might as well flip a coin.

It is worth noting plaintiffs' view on this question. Incredibly, they maintain the First Amendment forbids removing even racist books. They defended that position before the panel: a librarian, they insisted, cannot remove "a book by a former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan" if she dislikes its view that "black people are an inferior race." At en banc, they doubled down. Astonishing. Who knew that the First Amendment requires libraries to shelve the collected works of the Ku Klux Klan? {Notably, the dissent declines to say whether its own rule would forbid a library's removing a racist book. But the answer seems clear. If the First Amendment prohibits a public library from removing a book because of its "inappropriate, offensive, or … undesirable" content, then the library could not constitutionally remove from its shelves even the most noxious racist screed. That is reason enough to reject the dissent's proposed rule.}

That is, of course, utter nonsense. "[I]f a library had to keep just any book in circulation—no matter how out-of-date, inaccurate, biased, vulgar, lurid, or silly," then "[i]t would be a warehouse, not a library." That is confirmed, not only by common sense, but also by the practices of leading library associations.

For example, a Texas weeding manual instructs librarians to weed "books that contain stereotyping … or gender and racial biases," "unbalanced and inflammatory items [about immigration]," and "books that reflect outdated ideas about gender roles." Similarly, the American Library Association (ALA) advises librarians to remove "items reflecting stereotypes or outdated thinking; items that do not reflect diversity or inclusion; [and] items that promote cultural misrepresentation." The same handbook proclaims it is "basic collection maintenance" to remove racist books, such as "the Dr. Seuss books that are purposefully no longer published due to their racist content." {Surprisingly, the ALA joined an amici brief that contradicts its own weeding advice. See Brief for Amici Curiae Freedom to Read Found. (arguing that weeding is based on "viewpoint neutrality," is "not the targeted removal of disfavored or controversial books," and "should not be used as a deselection tool for controversial materials").}

Whatever else one might think of the advice in these guides, it is unmistakably viewpoint discrimination. And, by plaintiffs' account, all of it violates the First Amendment. That cannot be the law. By definition, libraries must have discretion to keep certain ideas—certain viewpoints—off the shelves. "The First Amendment does not force public libraries to have a Flat Earth Section."

Finally, by removing a book, the library does not prevent anyone from "receiving" the information in it. The library does not own every copy. You could buy the book online or from a bookstore. You could borrow it from a friend. You could look for it at another library.The only thing disappointed patrons are kept from "receiving" is a book of their choice at taxpayer expense. That is not a right guaranteed by the First Amendment.

The majority also had this to say about a claimed viewpoint-neutrality requirement:

Racism is a viewpoint. So is sexism. So are "quackeries like phrenology, spontaneous generation, tobacco-smoke enemas, Holocaust denial, [and] the theory that the Apollo 11 moon landing was faked." If a librarian finds such dreck on the shelves, does the First Amendment bar him from removing it?

The dissent held that listeners' rights did indeed prohibit viewpoint-based book removals:

[T]he right asserted by Plaintiffs here … is not an affirmative right to demand access to particular materials. Rather, consistent with the First Amendment's text and longstanding Supreme Court doctrine, Plaintiffs assert a negative right against government censorship that is targeted at denying them access to disfavored, even outcast, information and ideas.

The First Amendment does not require Llano County either to buy and shelve They Called Themselves the K.K.K., or to keep They Called Themselves the K.K.K. in its collection in perpetuity; but it does prohibit Llano County from removing They Called Themselves the K.K.K., or books with similar ideas and information, because it seeks to "prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion." …

As a public library, rather than a school library, the Llano County library system serves patrons of all ages. Today, a majority of our court sanctions government censorship in every section of every public library in our circuit. As counsel for Defendants acknowledged in oral argument, there is nothing to stop government officials from removing from a public library every book referencing women's suffrage, our country's civil rights triumphs, the benefits of firearms ownership, the dangers of communism, or, indeed, the protections of the First Amendment….

The majority—apparently "amuse[d]" by expressions of concern regarding government censorship—disparages such concerns as "over- caffeinated" because, if a library patron cannot find a particular book in their local public library, they can simply buy it.

This response is both disturbingly flippant and legally unsound.

First, as should be obvious, libraries provide critical access to books and other materials for many Americans who cannot afford to buy every book that draws their interest, and recent history demonstrates that public libraries easily become the sites of frightful government censorship.

More significantly, the flippancy mischaracterizes the text and promise of the First Amendment. The First Amendment question presented by Plaintiffs' allegations … is not whether a library has an affirmative obligation to add a particular book to its collection whenever a patron wants it. Plaintiffs "have not sought to compel [Defendants] to add to the [public] library shelves any books that [patrons] desire to read." That is a red herring dragged throughout the majority opinion.

{Regardless, book acquisitions demand different considerations than book removals. As Justice Blackmun remarked in Pico:

[T]here is a profound practical and evidentiary distinction between the two actions: "removal, more than failure to acquire, is likely to suggest that an impermissible political motivation may be present. There are many reasons why a book is not acquired, the most obvious being limited resources, but there are few legitimate reasons why a book, once acquired, should be removed from a library not filled to capacity."

Justice Souter offered similar sentiments in another case: "Quite simply, we can smell a rat … when a library removes books from its shelves for reasons having nothing to do with wear and tear, obsolescence, or lack of demand…. The difference between choices to keep out and choices to throw out is [] enormous, a perception that underlay the good sense of the plurality's conclusion in [Pico]." And the two situations are distinct: book removal necessarily follows book acquisition, such that any book that is removed has passed the library's initial purchase assessment and expenditure.}

The relevant question is a more sobering one, implicating the very text of the First Amendment's protection against the abridgment of free speech: whether government officials may restrict—abridge—the spectrum of ideas available to the public by culling books from public library shelves, simply because those officials find the books' ideas inappropriate, offensive, or otherwise undesirable. The answer is: "No." The government may not order books removed from public libraries out of hostility to disfavored ideas and information….

Public libraries importantly serve patrons of all ages, and they have broad latitude to provide safe spaces for parents to encourage a love of learning in their children, while respecting each parent's prerogative to guide their own child's public library reading and, at the same time, without encroaching on every other patron's First Amendment rights. To repeat what is fundamental, Director Milum confirmed that "no parent has the authority in a library system to control what somebody else's children read."

Indeed, public libraries of course are free to organize their books in a manner that ensures patrons are directed to age-appropriate materials. Many, if not all, public libraries already do this by maintaining distinct sections for children and for young adults, while the remainder of the library is geared toward adults. Furthermore, the New Orleans Public Library, for example, provides parents and guardians with additional oversight by allowing them to adjust check-out permissions for their children. Parents can and should review what their children read and make decisions regarding what public library materials are appropriate for their children.

But that is each parent's prerogative for their own children. These decisions cannot be dictated by government officials, any more than they can be dictated by other parents, based on their own distaste for ideas they deem "inappropriate." Certainly, government officials cannot constitutionally dictate what ideas are "inappropriate" or "offensive" for adult library patrons. Yet this is precisely the government censorship that our court approves today.

The post The Fifth Circuit on Library Selection and Removal Decisions and First Amendment Rights of Listeners appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers