Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 80

June 10, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Civitas Institute Symposium: Texas and the Future of Legal Education

[Five scholars discuss what role, if any, the ABA should play in the regulation of legal education.]

Recently, the Texas Supreme Court requested comments on "whether to reduce or end the Rules' reliance on the ABA." Perhaps unsurprisingly, all of the Law Deans and nearly all law professors have fallen in line to support the ABA. I thought that the SCOTX would benefit from some alternate views. I helped to coordinate an excellent symposium from the Civitas Institute about the future of legal education in Texas. Here, five scholars discuss what role, if any, the ABA should play in the regulation of legal education.

Josh Blackman "The Supreme Court of Texas Must Put Texas First, and Liberate Law Students from the ABA Seth J. Chandler "Accrediting for Tomorrow: Law School Metrics and Interstate Compacts Andrew P. Morriss "Ending the ABA's Role in Accreditation Will Benefit Texas Derek T. Muller "New Paths for Legal Education Should Be Considered Ilya Shapiro "The ABA Deserves to Lose Its Accreditation Monopoly John Yoo "The Conserving Force of Lawyers in American Democracy"My essay challenges the orthodoxy that what is good for elite Texas law schools is good for Texas. I am skeptical.

The Texas Supreme Court, and indeed most state courts, have been subject to regulatory capture. Law deans want to attract law students from across the country, even those who do not plan to stay in Texas. Two decades ago, Justice Clarence Thomas lamented that the University of Michigan Law School was little more than "a waystation for the rest of the country's lawyers, rather than a training ground for those who will remain in Michigan." Thomas, as usual, was right. He questioned UM's "decision to be an elite institution [that] does little to advance the welfare of the people of Michigan or any cognizable interest of the State of Michigan."

We can ask the same question about Texas. Why is it in the interest of the Texas Supreme Court to allow students to be educated here and practice elsewhere? President Trump is fond of saying that Americans should put America first. Why shouldn't Texans put Texas first? Certainly, the Texas legislature does not provide benefits to Texans who pledge to leave the state. Why should the Supreme Court of Texas, when acting as a legislative body, behave any differently?

Thankfully, SCOTX now has a chance to correct the course. In 1983, SCOTX delegated to the American Bar Association the authority to accredit law schools. For the past four decades, law students must graduate from an ABA-approved law school to sit for the Texas bar exam. But in April 2025, SCOTX solicited public comments on "whether to reduce or end the . . . reliance on the ABA." This request came on the heels of the Florida Supreme Court's similar request.

The problems with the American Bar Association's Section of Legal Education are well known. The ABA imposes an endless series of "standards" on law schools, without providing any evidence that these standards are actually effective. The organization imposes a one-size-fits-all all policy, without regard to how the missions of elite law schools differ from those of access law schools. And critically, the left-leaning ABA has dragooned all law schools to impose onerous DEI requirements — a step they have only temporarily suspended in response to action from the Trump Administration. Critically, the ABA does not consider the needs of the people of Texas.

Yet, as could be predicted, the Texas Law Deans have rallied in support of the American Bar Association. On May 12, a "conversation" on the ABA's role as accreditor was convened by all of the Texas law schools (including my own). There were eleven speakers, ten of whom wholeheartedly supported the ABA's role as accreditor. Only Professor Seth J. Chandler of the University of Houston offered some critical comments about the organization. However, such groupthink is emblematic of the broader lack of ideological diversity in the academy. Moreover, this monolithic thought is especially unhelpful when deciding whether to change the regulatory regime. (Indeed, this online symposium hosted by the Civitas Institute was occasioned by the glaring one-sided nature of the ABA defense rally.)

The Texas Supreme Court would be well served to consider the entire symposium.

The post Civitas Institute Symposium: Texas and the Future of Legal Education appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Arresting Someone for Violating a Probation Condition That Doesn't Exist …

[would violate the Fourth Amendment, holds the Eleventh Circuit.]

A short excerpt from the long Gervin v. Florence, decided yesterday by the Eleventh Circuit (opinion by Judge Robin Rosenbaum, joined by Judges Nancy Abudu and Charles Wilson):

DeShawn Gervin has not been a model citizen. But he did do at least one thing right. As Gervin's sole condition of probation, a Georgia court kicked him out of its jurisdiction and banned him from returning. And Gervin followed that instruction. He moved to North Carolina.

But he didn't stay out of trouble there, either. North Carolina imprisoned Gervin for breaking and entering, larceny, and robbery and kidnapping.

Soon after, a probation officer with the Georgia Department of Community Supervision learned of Gervin's North Carolina transgressions. And she sought a warrant for his arrest in Georgia. In support, she swore that Gervin had "failed to report" and "absconded from probation supervision" in violation of his probation conditions. Another probation officer under her supervision then petitioned to revoke Gervin's probation based on his failure to report.

After the probation officer obtained the warrant, police officers in North Carolina arrested Gervin on the Georgia warrant. Then they extradited Gervin to Georgia. And Gervin spent 104 days in jail waiting for the court to resolve his probation-revocation charges.

But as we've recounted, the Georgia court's only probation condition for Gervin required him never to reenter its judicial circuit. And that's the one thing he had not done. So however else Gervin had broken the law, he had not violated his Georgia probation.

For that reason, the Georgia court concluded that the State failed to show that Gervin had violated his probation. So it ordered Gervin's release.

After his release, Gervin sued the two probation officers under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. He alleged violations of his Fourth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights. The probation officers moved for summary judgment, and the district court denied their motion.

We now affirm the district court's ruling. When we view the evidence in the light most favorable to Gervin as the non-moving party, the probation officers recklessly swore that Gervin had violated his Georgia probation, even though it was clear that he had not. That violated Gervin's Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable seizures because the officers' misconduct caused his arrest and prolonged confinement. And because every reasonable state official would have understood that the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit recklessly making false statements and material omissions to obtain an arrest warrant and prosecute a probation violation, the probation officers are not entitled to qualified immunity….

There's more, oh so much more, back to the Statute of Marlborough (1267). Zack Greenamyre (Mitchell Shapiro Greenamyre & Funt LLP) argued on behalf of plaintiffs, and Matthew Cavedon argued on behalf of amicus Cato Institute.

The post Arresting Someone for Violating a Probation Condition That Doesn't Exist … appeared first on Reason.com.

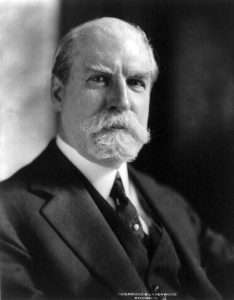

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: June 10, 1916

6/10/1916: Justice Charles Evans Hughes resigns.

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes

Chief Justice Charles Evans HughesThe post Today in Supreme Court History: June 10, 1916 appeared first on Reason.com.

June 9, 2025

[Ilya Somin] My New UnPopulist Article on Synergies Between Litigation and Political Action in Resisting Trump

[The article describes how the two can be mutually reinforcing, building on lessons from previous episodes in constitutional history.]

Today, the UnPopulist published my article on synergies between litigation and political action in resisting Trump 2.0's multi-faceted assaults on the Constitution. I explain how the two tracks can be mutually reinforcing.

As I was writing the article, it occurred to me that—with my role in the tariff case—I am directly involved in implementing these ideas; we are, of necessity, litigating this case in both the court of law and the court of public opinion. That kind of direct involvement in the subject of my own writings is not an accustomed role for an academic, at least not for me. Whether it gives me greater insight, reduces my objectivity or some combination of both, is for readers to judge.

Here is an excerpt from the article:

The Trump administration has launched a multi-faceted assault on many aspects of our constitutional system, ranging from illegal deportations of immigrants to blocking legal migration by unconstitutionally declaring a state of "invasion," to usurpation of congressional authority over federal spending and tariffs. These efforts have, in turn, encountered resistance by means of both litigation and political mobilization. But there has been little consideration of how the two types of resistance to Trumpism relate to each other. There are often important synergies between litigation and political action. Each can bolster the other. Such synergies don't always happen—and there are situations where litigation might actually undermine political efforts. Still, activists and litigators can act in ways that maximize synergies, while mitigating potential downsides.

Throughout modern history, successful constitutional reform movements have generally combined litigation and political action, not relied exclusively on one or the other. That was true of the Civil Rights Movement, the women's rights movement, same-sex marriage, and movements to expand property rights and gun rights, among others. Litigation can bolster political action, and vice versa.

These dynamics are also evident in the early results of litigation against some of Trump's abuses of power, most notably in immigration and trade.

The rest of the article discusses how these synergies have played out over the last few months, and notes some potential lessons we can learn.

The post My New UnPopulist Article on Synergies Between Litigation and Political Action in Resisting Trump appeared first on Reason.com.

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: S&W Sí, Mexico No

[“The AR–15 is the most popular rifle in the country.”]

On June 5, in an unanimous decision by Justice Elena Kagan, the Supreme Court ruled in Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. v. Estados Unidos Mexicanos that Mexico failed plausibly to plead that the American firearm industry aided and abetted unlawful sales routing guns to Mexican drug cartels. The decision not only adds teeth to the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA), it also recognizes that semiautomatic rifles like the AR-15 are in wide use by Americans, verifying that they meet Heller's common-use test.

While the Court does not expressly mention that PLCAA reaffirms Second Amendment rights, it does reference the preamble of the law, which explicitly set forth one primary purpose of PLCAA is to protect the Second Amendment rights of Americans. The Court then explained how the law protects the firearm industry from civil lawsuits blaming the industry for crimes and torts committed by third parties. It provides that "a qualified civil liability action" – defined as a civil suit against a manufacturer or seller of a firearm or firearm part (called a "qualified product") – may not be brought in any federal or state court.

Excluded from PLCAA is the "predicate exception," defined as "an action in which a manufacturer or seller of a qualified product knowingly violated a State or Federal statute applicable to the sale or marketing of the product, and the violation was a proximate cause of the harm for which relief is sought…." That includes acts in which a dealer or manufacturer knowingly makes false entries in records or conspires to sell a firearm to a prohibited person. If such violation is the proximate cause of harm, then liability arises from a third party's misuse of a gun.

Mexico claimed that Smith & Wesson and other manufacturers aided and abetted the third-party misuse of guns in Mexico. First, they supplied guns to dealers who sold guns to traffickers. Second, they allegedly failed to impose extra-legal controls on their distribution networks. And third, they supposedly make "design and marketing decisions" to stimulate cartel demand, such as production of "'military-style' assault weapons" and use of inscriptions that appeal to cartel members (like the "Emiliano Zapata 1911" pistol).

But Mexico's complaint failed to allege any specific criminal transactions by the manufacturers. Its claim that they sell guns to "known rogue dealers" (which it did not even identify) did not count as aiding and abetting. That claim could not be taken at face value, as "Mexico never confronts that the manufacturers do not directly supply any dealers, bad-apple or otherwise. They instead sell firearms to middlemen distributors, whom Mexico has never claimed lack independence."

Mexico further claimed that manufacturers did not regulate dealer practices, such as banning bulk sales or sales from homes. But federal law imposes no such requirement.

Finally, in the Court's view, Mexico's claims about the "design and marketing decisions" of manufacturers were of no consequence. The Court explained:

Mexico here focuses on the manufacturers' production of "military style" assault weapons, among which it includes AR–15 rifles, AK–47 rifles, and .50 caliber sniper rifles…. But those products are both widely legal and bought by many ordinary consumers. (The AR–15 is the most popular rifle in the country….)

For that last proposition, the Court cites T. Gross, How the AR–15 Became the Bestselling Rifle in the U.S., NPR (Apr. 20, 2023). Although that article is filled with inaccuracies, it states that the AR-15 "now pretty much dominates the rifle market in the U.S. and is one of the most popular … guns, period, sold…." It adds that, "using industry estimates and production estimates, … about 20 million AR-15s have been sold in … the last couple of decades in the U.S." And it has "market dominance … 1-in-4 guns manufactured these days – it's unmistakable."

So now we have all nine Justices agreeing that the AR-15 is "widely legal and bought by many ordinary consumers" and "is the most popular rifle in the country." That comes on the heels, as we discussed here, of the Court denying cert in Snope v. Brown, in which Justice Kavanaugh stated that "Americans today possess an estimated 20 to 30 million AR–15s," strongly implied that the Fourth Circuit "erred by holding that Maryland's ban on AR–15s complies with the Second Amendment," and predicted that "this Court should and presumably will address the AR–15 issue soon, in the next Term or two." And don't forget Justice Sotomayor stating in Garland v. Cargill that AR-15s are "commonly available, semiautomatic rifles."

On a personal note, I'm grateful for the Justices buttressing the validity of the title of my latest book, America's Rifle: The Case for the AR-15.

While one cannot predict how every Justice would rule on a ban on semiauto rifles, the Court held in Heller that the Second Amendment protects arms that are "in common use at the time" for "lawful purposes like self-defense" or are "typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes." And because the "in common use" test arises from the history portion of the Court's "text first, history second" interpretative methodology, the burden actually lies with the government to demonstrate that the subject arm is not in common use. Unfortunately, in upholding bans, lower courts are pretending not to understand the common-use test, if not ridiculing and obstructing it.

As Justice Kagan continued in Smith & Wesson, "The manufacturers cannot be charged with assisting in criminal acts just because Mexican cartel members like those guns too. The same is true of firearms with Spanish-language names or graphics alluding to Mexican history." Even if desired by cartel members, "they also may appeal, as the manufacturers rejoin, to 'millions of law-abiding Hispanic Americans.'" (As I pointed out here after oral argument, it turns out that the engravings were put on the pistols by a distributor, not by Colt.)

Accordingly, Mexico failed adequately to allege the predicate exception under PLCAA, the purpose of which was "to halt a flurry of lawsuits attempting to make gun manufacturers pay for the downstream harms resulting from misuse of their products." Mexico's claims "would swallow most of the rule," which requires that a manufacturer violate a gun law and seek to have an unlawful act succeed.

Since Mexico failed to make a plausible claim for aiding-and-abetting liability, "We need not address the proximate cause question…." It would have been helpful had the Court resolved that issue as well, because many anti-industry suits don't involve aiding-and-abetting liability but are based on theories that are antithetical to traditional concepts of proximate cause. Despite that, the tone of the decision in recalling the purpose of PLCAA will be helpful in other cases.

Concurring, Justice Thomas noted that the decision did not resolve what would be required to show a "violation" of a gun law under the predicate exception. That would arguably require not just an allegation, but an actual finding of guilt or liability in an earlier adjudication. "Allowing plaintiffs to proffer mere allegations of a predicate violation would force many defendants in PLCAA litigation to litigate their criminal guilt in a civil proceeding, without the full panoply of protections that we otherwise afford to criminal defendants."

Justice Jackson also concurred, noting the complaint's failure to allege any nonconclusory statutory violation. But "PLCAA reflects Congress's view that the democratic process, not litigation, should set the terms of gun control." Mexico faulted the industry for practices that are lawful and sought to have the courts become the regulators, despite that "Congress passed PLCAA to preserve the primacy of the political branches—both state and federal—in deciding which duties to impose on the firearms industry."

From the beginning, Mexico's suit against the American firearms industry was not a sincere PLCAA claim brought to remedy cartel violence. It was instigated and lawyered by the anti-gun political movement that PLCAA was enacted to curtail. The Supreme Court's 9-0 decision is a refreshing reaffirmation that the Supreme Court can get it right.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: S&W Sí, Mexico No appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] The Divisions Among the Court's Originalists

[Professor Joel Alicea on how to understand what may be the most important jurisprudential divisions on the Supreme Court. ]

Professor Joel Alicea has a thoughtful and perceptive op-ed in the New York Times, "The Supreme Court Is Divided in More Ways Than You'd Think," discussing the issues that divide the Supreme Court's five originalist justices. It begins:

When Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett joined the Supreme Court during President Trump's first term, originalism found itself in an unfamiliar and challenging position.

All three of the court's new members were avowed originalists, holding that judges ought to interpret the Constitution according to the meaning it had when it was ratified. As a result, a majority of the justices, including Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, now subscribed to this theory. Originalism, long seen as an insurgent force at the Supreme Court, had become its reigning philosophy.

For the originalists on the court, the shift from backbenchers to decision makers brought new responsibilities and presented new difficulties. Problems that had mostly been hypothetical debates within the court's originalist minority became central questions of constitutional law. How readily should an originalist court overturn a precedent at odds with the original meaning of the Constitution? What should an originalist judge do when the original meaning of the Constitution does not fully address a modern dispute?

As Professor Alicea notes, the five originalist justices often disagree on a range of issues that can affect how cases are decided and how quickly the Court's doctrine changes, including the extent to which the Court should respect non-originalist precedent and whether originalism, on the margin, should be more focused on constraining judicial discretion or on fulfilling the original meaning of the Constitution.

These differences matter because in a fair number of high-profile cases, such disagreements may control case outcomes and the contours of case holdings. Writes Alicea:

For originalists such as myself, these fractious dynamics pose the greatest threat to the urgent effort to restore the rule of law that was so badly damaged by the Supreme Court in the 1960s and '70s under Chief Justices Earl Warren and Warren Burger. But for all observers of the court, regardless of judicial or political inclination, these disputes are key to understanding its decisions.

He concludes:

This Supreme Court, contrary to accusations that it is lawless and political, is more committed to a particular constitutional theory than any Supreme Court has been since at least the 1940s. Understanding the deep theoretical roots of the conservative justices' agreements and their disagreements is crucial to appreciating what has happened since Mr. Trump transformed the court during his first term — and what may happen in the years to come.

The post The Divisions Among the Court's Originalists appeared first on Reason.com.

[Steven Calabresi] Should the Seventh Amendment Civil Jury Trial Right Apply to the States?

[The right to a civil jury trial is far more deeply rooted in American history and tradition than is the right to own guns, which the Supreme Court was right to incorporate.]

This coming Thursday, June 12th, the Court will decide whether to grant certiorari (or whether to request a response) to the Institute for Justice's petition for certiorari in Thomas v. County of Humboldt, a case which asks the Court to incorporate the Seventh Amendment civil jury trial right through the Fourteenth Amendment against the States.

The Bill of Rights was originally enacted in 1791 to constrain Congress; protections against state overreach were left to state constitutions. But the Fourteenth Amendment was created to provide federal protection against state power; and since the Civil War, the Court has held (through a process called "incorporation") that nearly all the Bill of Rights applies to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment.

The right to civil jury trial was among the three civil rights most deeply rooted in American history and tradition at the time of the framing of the federal Bill of Rights along with the right to criminal jury trial and the right to the free exercise of religion. The right is by far and away the most important right in the Bill of Rights that has not yet been incorporated; the other two unincorporated rights are the Third Amendment's protection against the quartering of soldiers in peoples' homes (a practice that no longer happens) and the right to indictment by a grand jury (which is meaningless since prosecutors can persuade grand juries to indict even "a ham sandwich").

Cases like Thomas v. County of Humboldt, which involve a dispute between the government and a private citizen, where petitioners are challenging millions of dollars of fines assessed against impoverished litigants in administrative proceedings by the government with no right to a civil jury trial, show that incorporation of the Seventh Amendment is as urgent as was incorporation of the Excessive Fines Clause in Timbs v. Indiana, 586 U.S. 146 (2019). As the Supreme Court held last year in SEC v. Jarkesy, 603 U.S. 109 (2024) (requiring the SEC to litigate fraud cases in federal district court with a Seventh Amendment right to a civil jury trial), "[t]he right to trial by jury is 'of such importance and occupies so firm a place in our history and jurisprudence that any seeming curtailment of the right' has always been and 'should be scrutinized with the utmost care.'" Id. at 121. A continuing failure by the Supreme Court to incorporate the civil jury trial right against the States would thus be an embarrassing omission from the Court's caselaw given that this right is even more deeply rooted in American history and tradition than are almost any other right including especially the right to own a gun for one's own self-defense.

The Thomas case seeks to change that, and I think the Court should agree on this with the petitioners.

In 2010, the Supreme Court correctly incorporated the Second Amendment's right to own a gun for one's own self-defense in McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010) on a five to four vote. The Court held correctly that the right to own a gun for one's self-defense was a right that was deeply rooted in American history and tradition following Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997). Accord, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. 215 (2022) (abortion rights are not deeply rooted in history and tradition).

In McDonald, the Court observed that 22 States out of 37 States in 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, protected the right to keep and bear arms in their State Bills of Rights, i.e. 59% of the States at that time. Steven G. Calabresi & Sarah E. Agudo, Individual Rights Under State Constitutions When the Fourteenth Amendment Was Ratified in 1868: What Rights are Deeply Rooted in American History and Tradition? 87 Texas L. Rev. 7, 50-55 (2008). Sixty-one percent of the American people lived in those States in 1868—a sizable super-majority. Id. at 50. Based on this, and other evidence, the Court rightly concluded that the right to own a gun for one's own self-defense was very deeply rooted in American history and tradition. The Court reached this correct outcome even though in 1791, when the federal Bill of Rights was ratified, only 5 States out of 12 that had written constitutions and Bills of Rights protected gun rights. Steven G. Calabresi, Sarah E. Agudo, and Kathryn L. Dore, State Bills of Rights in 1787 and 1791: What Individual Rights are Really Deeply Rooted in American History and Tradition?, 85 Southern California Law Review 1451, 1485-1487 (2012).

But when it comes to the Seventh Amendment, 36 out of 37 State Constitutions in 1868, guaranteed the right to jury trials in all civil or common law cases. Calabresi & Agudo, supra at 77-78. "Fully 98% of all Americans in 1868 lived in jurisdictions where they had a fundamental state constitutional law right to jury trial in all civil or common law cases." Id. at 77. The lone State in the Union not to recognize a right to civil jury trial in 1868 was Louisiana, which because of its French and Spanish roots in the civil law tradition found there to be no right to civil jury trial; in this, Louisiana diverged from all other states' common law tradition, which recognizes such a right. The case for the incorporation of the Seventh Amendment is much stronger than was the case for the incorporation of the Second Amendment (which, again, I think the Court was right to incorporate).

In 1791, when the federal Bill of Rights was ratified, 12 of the 14 States (the original 13 plus Vermont, which had just joined the Union) had new constitutions and Bills of Rights, while Rhode Island and Connecticut retained their colonial charters with all references to the King of Great Britain struck out. All 12 of these States protected the right to civil jury trial in their new State constitutions and Bills of Rights. Calabresi, Agudo & Dore, supra at 1511. More than 85% of the American people lived in states with such constitutional protection of the right to civil jury trial. Id. In addition, Connecticut and Rhode Island also protected the right to civil jury trial even in the absence of newly crafted state constitutions. See Charles W. Wolfram, The Constitutional History of the Seventh Amendment, 57 Minn. L. Rev. 639, 655 (1973). "In all of the thirteen original states formed after the outbreak of hostilities with England, the institution of civil jury trial was continued, either by express provision in a state constitution, by statute, or by continuation of the practices that had applied prior to the break with England." Id.

Today, forty-nine States representing 98% of the States and 98.5% of the U.S. population guarantee the right to jury trials in civil cases within their state constitutions, and Louisiana is the only outlier. Steven Gow Calabresi et al., Individual Rights Under State Constitutions in 2018: What Rights Are Deeply Rooted in a Modern-Day Consensus of the States?, 94 Notre Dame L. Rev. 49, 113 (2018). But as the Thomas petition for certiorari shows States are ignoring their State Constitutions (or at least reading them unduly narrowly), including in imposing outrageous multi-million-dollar fines in administrative proceedings against impoverished defendants.

The last time the Supreme Court considered in any detail whether to incorporate the Seventh Amendment was in 1916, 109 years ago, in Minneapolis & St. Louis R. Co. v. Bombolis, 241 U.S. 211 (1916). To say the least, the Supreme Court's incorporation caselaw has shifted mightily since then, but the Court has never gone back and overruled Bombolis as it should do now. The Thomas case presently before the Court shows why it is urgent to take that step right away.

The civil jury has a long and distinguished history in Anglo-American law. The great English Law commentator, William Blackstone, who was widely read by the framers of the Bill of Rights, wrote that jury trial was used "for time out of mind" in England, see William Blackstone, Commentaries 349; whether or not he was correct as a matter of history, his views were the basis for founding-era attitudes, see Wolfram, supra at 653 n.44 (1973) ("The framers all seem to have agreed that trial by jury could be traced back in an unbroken line to … Magna Charta"). The Declaration of Independence complained in 1776 of "pretended Legislation … depriving us in many cases of the benefit of Trial by Jury."

The Continental Congress in the Ordinance for the Northwest Territory ensured that the "inhabitants of the said territory shall always be entitled to the benefits of … the trial by jury." An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, Northwest of the River Ohio art. II (1787). And, importantly, the Judiciary Act of 1789 provided for jury trials in "all suits at common law in which the United States sue," even before the ratification of the Seventh Amendment in 1791. An Act to Establish the Judicial Courts of the United States Section 9, 1 Stat. 73,77 (1789).

The absence of a civil-jury guarantee in the Constitution was among the Antifederalists' chief objections to the Constitution of 1787, and the Framers responded to this objection by putting the Seventh Amendment in the federal Bill of Rights. Several relevant themes emerge from their remarks from that era. For one, they concurred with Blackstone that the right was a critical check on abuses of power by tribunals of all stripes. A pseudonymous Farmer warned that juries were integral to curbing the power of corrupt judges, "who may easily disguise law, by suppressing and varying fact," and stopping a backslide into "despotism." Essays by a Farmer, Md. Gazette (March 21, 1788) in 5 The Complete Anti-Federalist 36, 37-40 (Storing Ed. 1981).

In addition, the Antifederalists understood that the civil-jury guarantee was an especially vital shield for liberty in a particular context: suits between private citizens and the government as in Thomas v. County of Humboldt. The pseudonymous Democratic Federalist warned in 1787 of possible abuses by military officers, excise or revenue officers, or constables:

[I]n such cases a trial by jury would be our safest resource, heavy damages would at once punish the offender, and deter others from committing the same: but what satisfaction can we expect from a lordly court of justice, always ready to protect the officers of government against the weak and helpless citizen …? What refuge shall we then have to shelter us from the iron hand of arbitrary power?

See Letter from a Democratic Federalist (Oct. 17, 1787), in The Founders' Constitution 354 (P. Kurland & Ralph Lerner eds. 1987). The reference to "excise or revenue officers" makes clear that civil suits between citizens and either the federal or state governments like the one in this very case under discussion were especially worrisome.

Likewise, James Monroe at the Virginia ratifying convention worried about the possible loss of the jury trial in tax disputes with the federal government. See 3 The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution 218 (Jonathan Elliot ed. 1891). Monroe's concern about such suits is just as relevant in tax disputes between a private citizen, or a victim of police brutality, and a State revenue officer or a State police department.

The Antifederalists understood that the guarantee to a civil jury trial was, at its core, a republican ideal. The jury was to a judicial branch of government what the lower Houses of the federal or state legislatures were to the legislative branch:

The trial by jury is very important in another point of view. It is essential in every free country, that common people should have a part and share influence, in the judicial as well as in the legislative department. To hold open to them the offices of senators, judges, and offices to fill [for] which an expensive education is required, cannot answer any valuable purposes for them; they are not in a situation to be brought forward and fill those offices …. The few, the well-born, etc. as Mr. Adams calls them, in judicial decisions as well as in legislation, are generally disposed and very naturally too, to favour those of their own description.

The trial by jury in the judicial department, and the collection of the people by their representatives in the legislature, are those fortunate inventions which have procured for them, in this country, their true proportion of influence, and the wisest and most fit means of protecting themselves in the community.

Letter from the Federal Farmer, No. 4 (Oct. 12, 1787), in 2 The Complete Anti-Federalist 249-50 (Storing Ed. 1981).

The first ever dictionary of the English language, as it was spoken in the United States, was Noah Webster's, American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). Webster defines the word "jury" as follows (emphasis added): "JU'RY, noun [Latin juro, to swear.] A number of freeholders, selected in the manner prescribed by law, empaneled and sworn to inquire into and try any matter of fact, and to declare the truth on the evidence given them in the case. Grand juries consist usually of twenty four freeholders at least, and are summoned to try matters alleged in indictments. Petty juries, consisting usually of twelve men, attend courts to try matters of fact in civil causes, and to decide both the law and the fact in criminal prosecutions. The decision of a petty jury is called a verdict." It is clear that Webster in 1828, thought there was a nearly **just to acknowledge the Louisiana exception** universal right to civil jury trial in all federal and state civil cases in the U.S., which there was.

During the years leading up to the Civil War, abolitionists complained bitterly about the lack of federal or state jury trials in cases determining whether an alleged northerner, who happened to be Black, was, or was not, a fugitive slave. Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction 269-270 (1998). For a full and persuasive argument that the Fourteenth Amendment demands what Amar calls the refined incorporation of the Seventh Amendment, one need only consult pages 269 to 278 of Amar's timeless and excellent book. The right to a civil jury trial was as foundational to the Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment as it was to the Framers of the Bill of Rights. This is hardly surprising given that, as noted above, 36 out of 37 States constitutionally guaranteed a right to civil jury trial in 1868 when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified.

My good and highly esteemed friend, Sam Bray, has urged on another blog against the incorporation of the Seventh Amendment for what are, in my view, essentially policy reasons. Even if I agreed with Sam as a matter of policy—and I do not, because of the ruinous effects of State use of administrative proceedings in multi-million dollar cases involving poor and abused litigants like those in Thomas—I think that the law here is quite clearly in favor of the incorporation of the Seventh Amendment, as is argued in Amar's spectacular book cited above.

Sam's biggest concern is with what he fears would be the devastating effect that incorporating the law on civil jury trial, as it stood in 1791, would have on Delaware's Court of Chancery where most of the nation's corporations are chartered and where much corporate litigation takes place.

Professor Amar, and I, however, do not think that Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment incorporates the law as to rights in the federal Bill of Rights as that law stood in 1791. Instead, we favor what Amar calls refined incorporation, which would among other things ask what the law was on civil jury trial rights, or on the division between law and equity, in 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, not what it was in 1791 when the Seventh Amendment was ratified. Thomas is a Fourteenth Amendment case, unlike SEC v. Jarkesy, which was a Seventh Amendment case.

Accordingly, the relevant original meaning in Thomas is the original meaning of the civil jury trial right in 1868, not in 1791 as it was in Jarkesy. I know that the U.S. Supreme Court has failed to accept this principle in its incorporation caselaw, but all true originalists must concede its truth. I have no idea how many of Sam's policy concerns are alleviated by shifting the time of origin from 1791 to 1868, but I do think that is the only lawful thing for an originalist to do.

Another good friend, and esteemed former co-author, Will Baude, has a blog post up in response to Sam's. Will argues, and I agree with him, that:

[T]echnically speaking it's not that the Fourteenth Amendment mechanically incorporates the enumerated rights in Amendments 1-8, it's that both the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment's Privileges or Immunities Clause aimed to protect a range of fundamental rights.

I think the civil jury probably was such a right. But once we see the issue through the general law lens, it's easier to remember that incorporating the fundamental right still left it open to reasonable regulations within each state. So protecting the fundamental right to a civil jury shouldn't mean, as Sam fears, locking every state "into the English division between law and equity in 1791" or detonating "a neutron bomb on the Delaware Court of Chancery."

I agree that general law "incorporated" Fourteenth Amendment rights, drawn from the first eight amendments to the federal Constitution, which are constitutionally protected vis-à-vis the States according to what they meant in 1868. I also agree with Will that such rights can be regulated under the State police power given the statement in Corfield v. Coryell, 6 Fed. Cas. 546 (C.C.E.D.Pa. 1823) that all federal privileges or immunities are "subject nevertheless to such restraints as the government may justly prescribe for the general good of the whole." Reasonableness review under this language might leave some variation in how Delaware draws the law/equity line from how it might be drawn in other States. Mechanical incorporation of the Bill of Rights against the States with every right given only the meaning it had in 1791 and not in 1868 would be unwise, especially given that it's the likely outcome of the Court's agreeing to incorporate the Seventh Amendment. But that is not the sort of incorporation I mean to defend here.

Finally, the Institute for Justice has also responded to Sam Bray, and I agree with pretty much all of that response. But IJ does not comment on Will Baude's post, and that post I think contemplates a more originalist, more meaningful, and more flexible form of incorporation than is contemplated in IJ's petition for certiorari in Thomas. In any event, the Roberts' Court can certainly come up with a better reading of the relationship between the Seventh and the Fourteenth Amendments than did the White Court in Minneapolis & St. Louis R. Co. v. Bombolis (1916), which is an excellent reason to grant certiorari on Thursday, June 12th.

The post Should the Seventh Amendment Civil Jury Trial Right Apply to the States? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] No First Amendment Violation in Excluding Associated Press from "the Room Where It Happens"

In Friday's AP v. Budowich, the D.C. Circuit stayed the preliminary injunction that required the White House to let the AP back into White House, Air Force One, and Mar-a-Lago briefings. Judge Neomi Rao, joined by Judge Greg Katsas, wrote a statement explaining the ruling; here's a short excerpt from the 27-page opinion.

The Associated Press wants to be in the room where it happens. But in February 2025, White House officials excluded the AP from the Oval Office and other restricted spaces. Officials announced that access was denied because the AP continued to use the name Gulf of Mexico in its Stylebook, rather than the President's preferred Gulf of America. The AP sued, alleging that its exclusion violated the First Amendment. The district court held the AP was likely to succeed on its constitutional claims, and it issued a preliminary injunction prohibiting White House officials from denying, on the basis of viewpoint, access to press events held in the Oval Office, on Air Force One, and at the President's home in Mar-a-Lago.

We grant in part the government's motion for a stay pending appeal. The White House is likely to succeed on the merits because these restricted presidential spaces are not First Amendment fora opened for private speech and discussion. The White House therefore retains discretion to determine, including on the basis of viewpoint, which journalists will be admitted. Moreover, without a stay, the government will suffer irreparable harm because the injunction impinges on the President's independence and control over his private workspaces….

Reporters and photographers have long been permitted access to the White House complex to cover the President and his administration. The White House manages access by requiring journalists to obtain a press credential called a hard pass. More than one thousand journalists hold hard passes, through which they may access spaces such as the James S. Brady Briefing Room, where the White House Press Secretary delivers regular briefings.

Hard pass holders may also sign up via a reservation system to attend larger events hosted in the East Room, which is often used for meetings with foreign leaders, executive order signings, and press conferences. Because the White House has opened these press facilities "to all bona fide Washington-based journalists," hard passes may not be denied arbitrarily or based on the content of a journalist's speech. Sherrill v. Knight (D.C. Cir. 1977).

A small subset (around one percent) of hard pass holders is sometimes invited into even more restricted White House spaces, such as the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room. This group of privileged journalists, referred to as the "press pool," has historically been selected by the White House Correspondents' Association, a private organization of which the AP is a founding member. Since its inception, the press pool has had a relatively stable, although not fixed, membership. Journalists selected to be part of the press pool may travel with the President aboard Air Force One and attend small press events at the President's home in Mar-a-Lago, usually to observe presidential speeches and events. For many years, the Correspondents' Association offered the AP a standing invitation to send one reporter and one photographer to press pool events.

On February 11, 2025, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt informed the AP that it would not be permitted in the Oval Office or press pool unless it revised its Stylebook to refer to the Gulf of America, which President Trump had recently renamed from the Gulf of Mexico. The President and other senior White House officials publicly stated that the reason for the AP's exclusion was its continued use of the name Gulf of Mexico. The AP was similarly excluded from events in the East Room, despite signing up in advance through the reservation process. On February 25, the White House announced it would select journalists for participation in press pool events, instead of deferring to the selection made by the Correspondents' Association….

The district court held the Oval Office, Air Force One, and similar restricted spaces are nonpublic fora when members of the press pool are present, and therefore the AP's exclusion on the basis of viewpoint violates the First Amendment. We conclude the spaces to which the AP seeks access are not any type of forum. As such, the White House may consider journalists' viewpoints when deciding whether to grant access….

"A nonpublic forum is government property that is not by tradition or designation a forum for public communication." The government, "no less than a private owner of property, has power to preserve the property under its control for the use to which it is lawfully dedicated." Government property does not become a nonpublic forum unless and until the government takes some affirmative step to open the space for private communication. While the government need not open up property "that is not by tradition or designation a forum for public communication," the government "creates a nonpublic forum when it provides selective access for individual speakers." Until the government opens a restricted space to private speech between private parties, such a space is not a First Amendment forum at all.

Our cases provide guideposts for applying forum analysis to spaces in the White House. When the White House opens its facilities to the press generally, as it does in the Brady Briefing Room, it cannot exclude journalists based on viewpoint. Sherill v. Knight.

On the other hand, we have never suggested that there are any First Amendment restrictions on "the discretion of the President to grant interviews or briefings with selected journalists." Sherrill. In deciding which journalists to speak with, the President may of course take into account their viewpoint. If President Trump sits down for an interview with Laura Ingraham, he is not required to do the same with Rachel Maddow. The First Amendment does not control the President's discretion in choosing with whom to speak or to whom to provide personal access. It is a time honored and entirely mundane aspect of our competitive and free press that public officials "regularly subject all reporters to some form of differential treatment based on whether they approve of the reporters' expression." The Baltimore Sun Co. v. Ehrlich (4th Cir. 2006).

These uncontested principles provide the framework for assessing the AP's claim that the Oval Office and other restricted spaces become nonpublic fora when the White House selects a small group of journalists (such as the press pool) to be present for observational newsgathering and reporting.

{While viewpoint discrimination is often unconstitutional, we reject the dissent's primary argument that the White House's viewpoint-based exclusion of the AP is per se unconstitutional. This blanket conclusion finds no support in our First Amendment jurisprudence, which carefully assesses the type of government property at issue and recognizes that some government spaces are not fora at all and therefore are not subject to prohibitions on viewpoint discrimination.} …

The Oval Office is the President's office, over which he has absolute control and discretion to exclude the public or members of the press. As the district court explained, the Oval Office "is a highly controlled location … shrouded behind a labyrinth of security protocols," which "few members of the public will ever" enter. The President uses the space for myriad purposes, including speeches, signing ceremonies, and meetings with senior officials or heads of state. When events in the Oval Office are broadcast to the public, they feature the President's speech and expressive activity.

It hardly needs to be said that the Oval Office, Air Force One, or even the East Room are not places "traditionally open to assembly and debate," nor are they open to the public for expressive activity. The parties agree the White House could, consistent with the First Amendment, exclude press from these spaces entirely.

The AP's primary contention, however, is that when the Oval Office and similar spaces are opened to the press pool, they become nonpublic fora and therefore the White House may not withhold access on the basis of viewpoint. We disagree….

[T]he press events to which the AP seeks access do not involve the type of communicative activities that transform a restricted government space into a nonpublic forum. "[F]orum analysis applies only to communicative activities." In each of the Supreme Court's forum analysis cases, the activity triggering application of the doctrine involved "assembly, the exchange of ideas to and among citizens, the discussion of public issues, the dissemination of information and opinion, and debate—all of which are communicative activities." Where, as here, a small group of journalists is permitted to attend events in restricted White House spaces like the Oval Office, the primary activity is observational newsgathering…. Newsgathering may enjoy some First Amendment protections from government interference. But newsgathering is not itself a communicative activity. When journalists are invited to observe events in the Oval Office, they are gathering information for their reporting, which is "a noncommunicative step in the production of speech." …

[T]hese spaces should [also] not be classified as nonpublic fora because access to them is tightly controlled and highly selective. Only about one percent of hard pass holders can fit in spaces like the Oval Office. When access to government property is very limited, considerations of viewpoint may be permissible….

{Both the AP and the district court at various points suggest that if the White House maintains something like the press pool, it must allow access on a viewpoint neutral basis. For the reasons already explained, a group of journalists observing presidential events is not a forum of any sort. Accordingly, the White House should not have to choose between excluding all journalists and admitting journalists under the restrictions of a nonpublic forum. By recognizing the distinctions between different fora "we encourage the government to open its property to some expressive activity in cases where, if faced with an all-or-nothing choice, it might not open the property at all."}

Finally, the fact that the President is communicating at these events further distances this context from forum analysis. When the government is speaking, forum analysis is usually inapplicable because while the First Amendment "restricts government regulation of private speech[,] it does not regulate government speech."

Although the White House disclaims primary reliance on the government speech doctrine, the events to which the AP seeks access by their nature involve presidential, i.e. government, speech. The messages conveyed in the Oval Office are government speech and opportunities for the President's administration to express its message. "When government speech is involved, forum analysis does not apply and the Government may favor or espouse a particular viewpoint." Forum analysis is also inappropriate when government speech occurs within a limited space, such as the Oval Office, the "essential function" of which would be defeated by compelling the President to support private speech on a viewpoint-neutral basis.

{The district court relied heavily on a Seventh Circuit decision, which concluded that an "invitation-only, limited-access press event" hosted by the governor of Wisconsin was a nonpublic forum. See John K. MacIver Inst. for Public Policy, Inc. v. Evers (7th Cir. 2021). In that case, however, while the Governor argued that his press events were likely not a forum at all, he acknowledged that nonpublic forum analysis "might apply" under the circumstances. Without explanation, the Seventh Circuit held "the non-public forum analysis is the appropriate one" and concluded that the Governor's access policies were constitutional even under this more demanding standard. The case is therefore of limited relevance to the inquiry here, where the parties dispute whether these spaces are fora at all.}

The panel majority's opinion also rejected, for similar reasons, the AP's claim that it was impermissibly retaliated against based on its viewpoint:

Choosing who may observe or possibly speak with the President in these spaces is not the type of action that supports a retaliation claim. Rather, it is more akin to a decision about how the President wields the bully pulpit.

{Our dissenting colleague emphasizes that the denial of a government benefit based on speech is often actionable. While this is generally true, the press pool is in no way a government benefit program. Denying unemployment benefits, tax exemptions, or trademarks on the basis of viewpoint can support a First Amendment retaliation claim. Denying access to observe or speak with the President in his private spaces cannot. The dissent acknowledges that the President may take viewpoint into account when granting interviews to select journalists. Our holding today reflects the fact that granting access to spaces such as the Oval Office is more like granting interviews than like denying unemployment benefits.}

Furthermore, in determining whether a First Amendment retaliation claim is actionable, courts may be guided by "long settled and established practice[s]." White House staff, not to mention the President, often form relationships with reporters who cover the administration. Hard pass holders and press pool members daily jockey for access to certain privileged spaces and to senior administration officials. As the AP acknowledges (and the district court recognized), the White House can and does reward journalists with advantages like interviews with the President and the opportunity to ask questions at press events. Such viewpoint-based preferences occur at every level of government in the relationship between elected officials and the press. These pervasive practices simply do not give rise to a retaliation claim, regardless of how valuable the access may be….

Judge Nina Pillard dissented; a short excerpt from her opinion (which is also 27 pages long):

Defendants have not made the showing critical to their stay application that they are likely to succeed in establishing that the First Amendment allows them to oust journalists from the White House Press Pool based on their employing organization's viewpoint. Forum analysis readily confirms that failure. My colleagues' effort to distinguish forum analysis is nonetheless beside the point because the bar on viewpoint discrimination in nonpublic forums for private speech is but one iteration of a broader First Amendment principle strongly supportive of the AP's claims.

The majority's defense of defendants' viewpoint-based exclusion of the AP from the Press Pool utterly disregards that broader principle. So, too, does its assumption that the AP's retaliation claim is likely to fail. Denial of a tangible benefit in retaliation for a recipient's own viewpoint expressed elsewhere violates the First Amendment….

The prohibition on viewpoint discrimination applies equally to the imposition of penalties and the denial of benefits. The government may not condition receipt of any otherwise-available benefit or opportunity on a recipient's endorsement or avoidance of a particular viewpoint. That rule applies to government benefits generally, including federal funding, tax exemptions, trademarks, government contracts, and public-sector employment. Even where a government program is designed to support a small number of speakers selected on discretionary, aesthetic criteria, it may not impose restrictions intended to punish "certain ideas or viewpoints." NEA v. Finley (1998). And even discretionary support to public broadcasters cannot be allocated to "curtail expression of a particular point of view." FCC v. League of Women Voters (1984)….

The President's use of the Oval Office as a platform for his official speech does not entail governmental authority to impose viewpoint restrictions on the Press Pool. Even where the government funds private organizations to advance official policy and therefore can control the viewpoint expressed within the funded program, it may not deny support based on disapproval of the recipient's speech outside that program. The government may not require private participants to "adopt—as their own—the Government's view on an issue of public concern as a condition of funding." That is why the Supreme Court in Agency for International Development held that the government violated the First Amendment rights of an organization receiving public support to advance the government's HIV/AIDS prevention mission when it required the organization to echo the government's opposition to prostitution in the organization's own work with its own funds. Id. at 218-21. The rule that public funds may be limited to the purpose for which they are granted does not empower the government to impose viewpoint restrictions on grantees' private speech.

Whatever my colleagues mean by emphasizing that Oval Office events "involve" governmental speech because the President typically speaks there, the Press Pool's coverage of those events—let alone the content of the AP's Stylebook—is not governmental speech legitimately subject to official viewpoint control. My colleagues are also wrong that the "essential function" of the Oval Office is "defeated" by the presence of a Press Pool free from viewpoint discrimination. The Press Pool has operated without viewpoint control for almost a century during which presidents have communicated directly from the Oval Office. The purpose of the Press Pool has never been to propagandize for the President, but only to enable reliable news coverage of his leadership. Public officials' prerogative to speak for the government does not include any ability to control private parties' speech on their own behalf, even when that speech relates to the government's message….

Defendants' (and the majority's) principal argument is that the President has unlimited discretion to pick "which journalists to grant special access unavailable to other members of the press corps." Their sole precedent is Baltimore Sun Co. v. Ehrlich (4th Cir. 2006), which is both inapposite and not binding on this court. The plaintiff journalists in Baltimore Sun objected to government officials' refusal to grant them interviews or return their calls. Judicial relief would have required the defendants to speak with certain reporters. Any such command would have strained the basic principle that "[t]he First Amendment's Free Speech Clause does not prevent the government from declining to express a view," and that the government may choose for itself "what to say and what not to say."

The AP does not assert a right to have the President return its phone calls, or to "interact and speak with government officials." What the AP challenges is its reporters' and photographers' exclusion from a government program for which it is otherwise fully eligible and has long participated, based solely on the AP's own expression in its Stylebook and reporting….

The government is represented by lawyers Daniel Tenny, Eric Dean McArthur, Mark Reiling Freeman, and Steven Andrew Myers (Justice Department) and Jane M. Lyons (D.C. U.S. Attorney's Office).

The post No First Amendment Violation in Excluding Associated Press from "the Room Where It Happens" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Dismisses Justin Baldoni's Defamation Claims Against Blake Lively and Others (Stemming from the Making of It Ends With Us)

The opinion (132 pages long) by Judge Lewis Liman (S.D.N.Y.) is here; the court also rejects the Baldoni side's civil extortion, breach of contract, false light, promissory fraud, and breach of contract claims. The opinion is too long to summarize here, but the key arguments that the court accepted as to the defamation claims are:

Statements quoting from Lively's California Civil Rights Department complaint are protected by the "fair report" privilege, which covers fair reports of court filings (and which is especially broad in California). Statements that go beyond the CRD complaint, made by Lively's publicist (Leslie Sloane), Lively's husband (Ryan Reynolds), and the New York Times, were not made with knowledge that they were false or likely false (what libel law calls "actual malice").You can see much more in the opinion.

The post Court Dismisses Justin Baldoni's Defamation Claims Against Blake Lively and Others (Stemming from the Making of It Ends With Us) appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers