Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 72

July 16, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Legislature May Choose What Viewpoints May or May Not Be Taught in Public Schools

From today's decision in Walls v. Sanders, by Eighth Circuit Judge Steven Grasz, joined by Judges James Loken and Raymond Gruender (which I think is generally correct):

[T]he government's own speech "is not restricted by the Free Speech Clause," so it is free to "choose[ ] what to say and what not to say." …

[Arkansas law, "Section 16,"] directs the Arkansas Secretary of Education to ensure the Arkansas Department of Education complies with Titles IV and VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act by reviewing its communications and materials to see if they "promote teaching that would indoctrinate students with ideologies such as Critical Race Theory, otherwise known as 'CRT', that conflict with the principle of equal protection under the law or encourage students to discriminate" based on someone's protected characteristics. The Secretary must also "amend, annul, or alter" any "rules, policies, materials, or communications that are considered prohibited indoctrination" and "review and enhance the policies that prevent prohibited indoctrination." "Prohibited indoctrination" is defined as:

communication by a public school employee, public school representative, or guest speaker that compels a person to adopt, affirm, or profess an idea in violation of Title IV and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, including that:

(1) People of one color, creed, race, ethnicity, sex, age, marital status, familial status, disability status, religion, national origin, or any other characteristic protected by federal or state law are inherently superior or inferior to people of another color, creed, race, ethnicity, sex, age, marital status, familial status, disability status, religion, national origin, or any other characteristic protected by federal or state law; or

(2) An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment solely or partly because of the individual's color, creed, race, ethnicity, sex, age, marital status, familial status, disability status, religion, national origin, or any other characteristic protected by federal or state law.

Section 16 expressly excludes from its prohibition: (1) discussions about "[i]deas and the history of concepts described" in the "prohibited indoctrination" definition; and (2) discussions about "[p]ublic policy issues of the day and related ideas that individuals may find unwelcome, disagreeable, or offensive." A teacher who violates Section 16 by engaging in "prohibited indoctrination" "could be punished (up to losing his or her license) by the State Board of Education."

Students challenged Section 16 on Free Speech Clause, but the Eighth Circuit rejected that argument:

Though a listener's right to receive information means the government cannot stop a willing private speaker from disseminating his message, that right cannot be used to require the government to provide a message it no longer is willing to say. After all, "[w]hen the government wishes to state an opinion, to speak for the community, to formulate policies, or to implement programs, it naturally chooses what to say and what not to say," unrestrained by the Free Speech Clause. The government is ultimately accountable to its citizens for its speech through elections, so the government may change the message it promotes in response to the political process.

Students do not possess a supercharged right to receive information in public schools that alters these principles. Just as ordinary citizens cannot require the government to express a certain viewpoint or maintain a prior message, students cannot oblige the government to maintain a particular curriculum or offer certain materials in that curriculum based on the Free Speech Clause.

The court also rejected an academic freedom claim (a claim that some courts have accepted as to public higher education, but that has generally not been accepted as to K-12 education):

Board of Education v. Pico (1982) …, which dealt with a school board's decision to remove certain books from school libraries, is of little help to [the students';] cause…. Pico lacks any holding as to the First Amendment ….

Even considering the persuasive value of the principal plurality opinion which concluded students had a right to receive books previously added to a school library, it distinguished the school library from the classroom and recognized that the government has a "claim of absolute discretion in matters of curriculum" and "the compulsory environment of the classroom" to carry out its "duty to inculcate community values." The other Pico opinions that discussed the First Amendment's Free Speech Clause also cast doubt on the Clause's role as a check on curriculum choices. Here, we deal not with books in a library, but instead with in-classroom instruction and materials in a high school. If Pico is any guide, Arkansas has substantial, if not absolute, discretion in selecting what materials and information to provide in its public school classrooms.

[Pratt v. Indep. School Dist. No. 831 (8th Cir. 1982)] is closer to the present case. There, we concluded "school boards do not have an absolute right to remove materials from the curriculum" if the removal "was intended to suppress the ideas expressed" in the removed materials…. [But] Pratt, which was decided in 1982, predates the numerous Supreme Court decisions holding that the government is permitted to engage in viewpoint discrimination when it speaks. Since Pratt, the Supreme Court has instructed that a court must consider "principles applicable to government speech" when the issue involves "speech by an instructor or a professor in the academic context."

The present case deals directly with such in-classroom instructional speech, as all parties agree. Pratt omitted the crucial step of considering whether the speech at issue was the government's and therefore not subject to the Free Speech Clause's restrictions. Indeed, its test resembles the one applied to the government's regulation of student speech in school-sponsored settings. We have not reaffirmed Pratt's application to a Free Speech Clause challenge since the proliferation of the government speech doctrine. In similar circumstances where subsequent Supreme Court cases have demonstrated that our earlier panel decision engaged in "only half of the analysis" required to address the issue, we concluded we were not bound to reach the same result as our prior precedent.

Despite the clear incompatibility of Pratt's imposition of a viewpoint discrimination limitation and the Supreme Court's government speech doctrine, the students argue we should still follow it in the narrow circumstance where the government is alleged to have changed a pre-existing curriculum for "partisan or political" reasons. But "virtually all educational decisions necessarily involve 'political' determinations," so any time something is removed from the curriculum based on the decision of a democratically elected government entity, it could be characterized as a "partisan or political" choice.

We see no basis in the Free Speech Clause to conclude the students would have a right to prevent something from being removed from the curriculum based on ideology if they do not also have a right to require the school to add materials. And the students reasonably concede they lack the latter right. Given that this asserted right only runs in one direction, the students' proposition would create an incumbency bias that erodes democratic accountability for government speech. Any time the government seeks to alter the curriculum by removing materials, it would face potential challenges that it is doing so for perceived ideological reasons.

By applying this test only when materials are removed, we essentially assume that the preexisting curriculum reflects some neutral ideal. If the removed materials were added to the curriculum for "partisan or political" reasons, future governments should surely be free to remove those materials to reflect new priorities based on voters' wishes. Nevertheless, under the students' proposed rule, the government is stuck with those materials unless it can sufficiently convince a court that it is removing them for non-ideological reasons. And removing materials because those materials were added to promote "partisan interests" could itself be classified as suppressing a particular ideological viewpoint from the classroom and therefore an improper ideological motivation for modifying the curriculum.

{ Indeed, this case suggests how such an explanation would likely result in litigation. While the Arkansas officials dispute that Section 16 prohibits teaching about CRT, their brief argues they could remove such materials even under the students' test because the materials promote an "ideolog[y] that … urg[es] openly race-based policies"—in other words, they view teaching about CRT as inculcating a certain ideological position.

Ultimately, if we followed the students' approach, a government could not successfully defend its decision to change the curriculum by arguing that it was responding to the electorate and the political process. Such an outcome runs headlong into the Supreme Court's government speech cases, which repeatedly emphasize the role of the political process and elections in regulating government speech. Typically, "[i]f the citizenry objects, newly elected officials later could espouse some different or contrary position." Thus, we usually permit changes in government speech motivated by the political process, rather than declare them unconstitutional.

It would be odd to treat government speech in schools differently since "the education of the Nation's youth is primarily the responsibility of parents, teachers, and state and local school officials, and not of federal judges." We decline the students' invitation to make the school curriculum uniquely static and unaccountable. We therefore conclude that Pratt's test has been abrogated by the Supreme Court.

We do not minimize the students' concern—whether in this case or in the abstract—about a government that decides to exercise its discretion over the public school curriculum by prioritizing ideological interests over educational ones. But the Constitution does not give courts the power to block government action based on mere policy disagreements. The right to receive information cited by the students in support of the preliminary injunction does not authorize a court to require the government to retain certain materials or instruction in the curriculum of its primary and secondary public schools, even if such information was removed for political reasons. Since the speech belongs to the government, it gets to control what it says….

The court also rejected a vagueness objection to the law, on procedural grounds.

The post Legislature May Choose What Viewpoints May or May Not Be Taught in Public Schools appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Professor Barrett Was At Home In CASA

After the Supreme Court decided Trump v. CASA, the Wall Street Journal editorial page took a victory lap. The editors, who have consistently defended Barrett, wrote "What an end-of-term rejoinder to the MAGA loudmouths who have been complaining that Justice Barrett is a pushover." On July 4, the WSJ published a letter to the editor as a follow-up:

A few months ago I ran into Justice Neil Gorsuch and lamented some of his colleagues' recent opinions. I criticized Justice Amy Coney Barrett and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson in particular, both of whom had recently ruled against the Trump administration. Justice Gorsuch was characteristically gracious and spoke of how each was entitled to his own opinions.

I once was what your editorial "The Supreme Court Kills 'Universal' Injunctions" (June 28) refers to as a "MAGA loudmouth." After reading Justice Barrett's superb opinion in Trump v. CASA, I am a repentant MAGA loudmouth. She is a star—and I regret ever doubting it.

Joel Marks

Richmond, Va.

Did this encounter with Justice Gorsuch actually happen? I find this conversation so implausible. And I cannot find any record for a Joel Marks who is an attorney in Richmond. I searched the Virginia State Bar for a Joel Marks and found nothing. I did find a news story from Henrico County, Virginia, where a Joel Marks complained about a broken water main.

I provide this background to illustrate how poorly the criticism of Justice Barrett is understood. If Marks criticized Barrett for simply ruling against Trump, he has no idea what he is talking about. And if he thinks that Justice Barrett's decision in CASA suggests she will not rule against Trump in the future, then Marks really has no clue what he is talking about. Why then did the WSJ give Marks the time of day? Marks fit the template--those who doubted Justice Barrett now have no doubts.

My doubts remain. Indeed, they are reinforced. These doubts predated Trump's re-election, and were never premised on whether Barrett rules for Trump. Brackeen and Vidal are critical data points, combined with a string of emergency docket rulings, and a consistent record of denying cert on important cases. My concern is this: how much evidence does Barrett requires to reach an originalist ruling? Academics, as a whole, require fully-developed theories based on a volume of scholarly articles to reach a solid conclusion. Judges, generally, do not.

Trump v. CASA should not have been a particularly difficult case. There is fairly overwhelming evidence that universal injunctions are recent innovations, and that under Grupo Mexicano, such novelty is doubtful. Justices Thomas and Gorsuch reached this conclusion years ago with ease. I can imagine Justice Scalia disposing of this case pretty easily.

Yet, Justice Barrett's opinion reads like a law review article that summarizes the academic literature. On point after point, Barrett contrasts the views of Sam Bray, Will Baude, and Michael Morley on the one hand with the views of Mila Sohoni on the other. Indeed, Barrett refers to Amanda Frost as the "mainstream" view. For readers of this blog, these names may be familiar. But for most lawyers, this sort of scholarly debate is quite esoteric.

Footnote 7 illustrates the point.

7There is some dispute about whether Wirtz was the first universal injunction. Professor Mila Sohoni points to other possible 20th-century examples, including West Virginia Bd. of Ed. v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624 (1943), Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925), and Lewis Publishing Co. v. Morgan, 229 U. S. 288 (1913). See M. Sohoni, 133 Harv. L. Rev., at 943; Brief for Professor Mila Sohoni as Amica Curiae 3; see also post, at 21 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.). But see M. Morley, Disaggregating the History of Nationwide Injunctions: A Response to ProfessorSohoni, 72 Ala. L. Rev. 239, 252–256 (2020) (disputing these examples).

Justice Sotomayor in dissent argues that West Virginia v. Barnette and Pierce v. Society of Sisters were examples of universal injunction. Yet, in a footnote, Justice Barrett leads off by citing Professor Sohonoi, with a see also to Justice Sotomayor's dissent! Doesn't that seem backwards? Shouldn't the Justice come first? And does Justice Barrett discuss those landmark cases, and explain why Sotomayor is wrong? No, she includes a But see citation to Michael Morley who "disputes" those examples. I suppose it is fair enough to cite a law review article that parses some history or arcana. But wouldn't it fall to a Supreme Court majority on how best to interpret landmark Supreme Court cases? I would like to know why Barnette and Pierce did not approve of universal injunctions. This is the sort of footnote that is all too common in academia. When there is contrary authority, just cite someone else who disputes it. But this is not how the Supreme Court usually handles a central disagreement.

I am grateful that Bray, Baude, and Morley have made such a compelling case against universal injunctions. But what if they hadn't? What if the theoretical framework was not so airtight? What if some earlier injunctions could plausibly have been characterizes as universal? Or what if this case came to the Court several years ago when many of these arguments were still being developed? Would Barrett have had enough of a theory to go on? I'm not sure. In short, Justice Barrett was able to write the strong opinion she did because of the scholarly work done by others. What would she have done in a case like Lopez, or even Heller, where the scholarly literature was not so solid?

We will have to wait for the next case that presents a novel constitutional question, and where there is not a clear scholarly consensus. That will provide the real test of where Justice Barrett is--and not the uncertain views of a MAGA loudmouth.

I appreciate my friend Ilya Shapiro's defense of Justice Barrett in the Washington Post. I find myself in agreement with much of it. Still, there are caveats. Ilya writes that Barret "will join the conservative majority on the substance of issues that are squarely presented [like] overturning Roe v. Wade." But Barrett voted to deny cert in Dobbs, and the Court only took the case after (likely) Justice Kavanaugh granted cert. Ilya writes that Barrett gave "Trump the immunity he needed to escape the lawfare he faced in the run-up to the last election." Sort of. It isn't clear which parts of the majority opinion she actually joined, and she would have allowed a trial to consider a range of otherwise immune conduct. Ilya writes that Barrett has "join[ed] the conservative majority" to "preserv[e] religious freedom." Except she refused to join Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch on overruling Employment Division v. Smith, and has shown no interest in revisiting the interest since Fulton. Ilya wrote that Barrett voted to "end[] racial preferences in college admissions." But she has denied review in cases where schools are flagrantly violating Students for Fair Admissions. Justice Barrett's Skrmetti concurrence read like the efforts of a law professor to make sense of Footnote Four--a Footnote that has no basis in the Constitution. I am still befuddled why Justice Thomas joined it, given that he agreed with Justice Scalia that Footnote Four should be jettisoned. And Ilya does acknowledge Barrett's opinion in Murthy, which erected an almost insurmountable standard for standing.

I could go on, but I won't. At a high level, Barrett's record look great. But if you drill down just a bit, things look differently. See the wall of receipts.

Still, OT 2024 was far better for Barrett than last term, or the term before. If we are grading terms, I would give her a solid B. I would give Justice Kavanaugh a B+. And Justice Gorsuch would get an A-. All three Trump appointees lose points for AARP. There is always hope for next term.

And with that, I have finished blogging about the decisions of the OT 2024 Term. Perhaps.

The post Professor Barrett Was At Home In CASA appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Congratulations To Kirill Muzyka, Chief Justice of FantasySCOTUS for OT 2024

Kirill Muzyka

Kirill Muzyka The October 2024 Term of FantasySCOTUS finally came to a close. On the whole, this term was a less predictable than some recent terms. In the aggregate, our crowd predicted 76.36% of the cases accurately, down from 83.05% of the cases accurately last term.

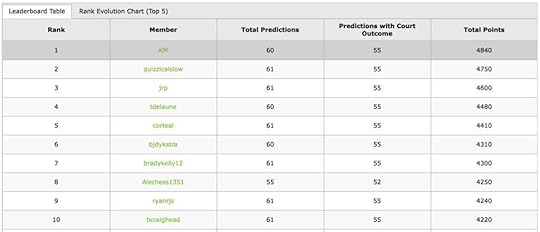

I am happy to announce that the Chief Justice is Kirill Muzyka. Players receive ten points for each correct prediction of a Justice's vote. We recorded 55 merits cases (DIGs do not count). A perfect score would have been 4,950 points. Kirill scored 4,840 points.

Here is the Top 10:

I usually ask the winner several questions to figure out their approach to predicting cases. Kirill's response was so thorough and insightful, that I reproduce it in its entirety:

My name is Kirill Muzyka. I'm from St. Petersburg, Russia, and I'm currently finishing my master's degree in Political Science at the London School of Economics.

My interest in American politics began quite some time ago, but I became especially focused on the U.S. Supreme Court in 2020, following the death of Justice Ginsburg. Her passing turned the Court into a major topic of public debate during the election, and that moment drew my attention. I eventually wrote a paper during my undergraduate studies on the Supreme Court's role in the polarization of American politics, and my interest in the Court has only grown since then.

What particularly drew me in was the contrast between the legal system in the U.S. and in my own country. The Supreme Court's dual nature — both legal and political — was fascinating to me. I was also struck by how the Justices manage to maintain respectful, even friendly, relationships despite deep ideological divisions. That kind of civility seemed rare and especially meaningful in today's political climate.

Since 2022, I've been listening to all oral arguments and making predictions about case outcomes for myself. In 2023, I began submitting predictions publicly through FantasySCOTUS. I've also read all of the Court's opinions from the past 2 terms. I really enjoy trying to understand the different perspectives each Justice brings, and I often try to reconstruct their arguments myself to determine which position I find most compelling. While I'm not a lawyer, I appreciate how the Justices generally write in a way that's accessible to an educated reader. In that sense, I'm especially fond of the opinions by Justices Kagan, Gorsuch, and Barrett — they're usually the clearest and most engaging to read.

When it comes to making predictions, I rely primarily on oral arguments. I think the post-COVID format — where each Justice has time to ask their questions — gives a clearer picture of how they're thinking about the case. If oral arguments don't reveal a clear outcome, I turn to other background factors, like the Justices' previous decisions or their overall judicial philosophy. Some Justices make prediction easier through their questioning. For instance, Justices Alito, Sotomayor, and Jackson often clearly signal their positions during arguments, which allows for solid predictions. Others — like Justices Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Thomas and Barrett, — tend to be more reserved and balanced in their questioning, so background information becomes more important. Justices Kagan, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh fall somewhere in between.

When I listen to arguments, I pay particular attention to "friendly" questions — the kinds that help, rather than challenge, an advocate's position. While Justices may press both sides on weak points, they rarely throw supportive "softball" questions to the side they ultimately oppose. I also find Oyez especially helpful — having both the audio and the transcript available in the same place makes it easier to fully understand the Justices' wording and tone.

Because I've been closely following the Court only in recent years, the only personnel change I've directly experienced has been Justice Jackson's appointment. Her style is notably clearer than Justice Breyer's often convoluted questioning, and she typically makes her views evident during argument. That has made case prediction somewhat easier — though not significantly so, given that she's part of the liberal minority and doesn't often determine the outcome.

In terms of case types, I find that technical statutory cases are generally harder to predict than high-profile constitutional ones. For example, this term, cases like Feliciano, Advocate Christ Medical, Bufkin, and Stanley were among the most difficult for me. That's, in my view, because in such cases, oral argument really can make a difference — the Justices often come in without firm views and genuinely explore the issues. In contrast, in more ideological cases, the Justices often already hold strong positions and are less swayed by the details. A good example of this contrast was the one argument I attended in person while visiting the U.S. as a tourist. — Mahmoud v. Taylor. After waiting in line for seven hours, I finally got in. It was a fascinating experience, but I doubt the oral arguments had much influence on the Justices, as they seemed to have already made up their minds based on ideological grounds.

I realize it may seem unusual for a complete foreigner with no formal legal training in the U.S. to be so interested in the Supreme Court. But coming from a country where the rule of law is almost absent, it's genuinely inspiring to watch a legal institution function with such intellectual rigor. While I understand and respect the perspective of those who view SCOTUS as primarily a political institution — "politicians in robes," as some say — I believe that's only part of the story. In reality, the Justices often demonstrate complexity and depth in their reasoning, and their opinions frequently reflect that nuance.

As someone from an authoritarian background, I'm deeply impressed by a system in which judges must publicly explain their decisions (putting aside the shadow docket), where legal reasoning matters, and where debate — even among ideological opponents — can shape outcomes. While my personal political leanings tend to align more with the liberal side of the Court, I've found that many conservative opinions are more thoughtful and well-argued than they are often given credit for. In my view, the American judicial system — though far from perfect — is an institution of extraordinary interest, and I look forward to continuing to follow it closely.

Well said. The seventeenth season of FantasySCOTUS will launch on the first Monday in October 2025.

The post Congratulations To Kirill Muzyka, Chief Justice of FantasySCOTUS for OT 2024 appeared first on Reason.com.

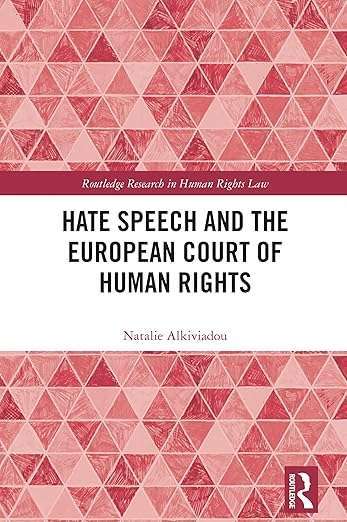

[Natalie Alkiviadou] Hate Speech and the European Court of Human Rights: The Low Threshold Hatred Paradigm—When "Offence" Is Enough to Restrict Speech

In this third post in The Volokh Conspiracy guest series, I examine a critical issue in the European Court of Human Rights' (ECtHR) hate speech jurisprudence: its embrace of what I term the "low threshold hatred paradigm." Under this approach, expressions that offend, insult, ridicule, or defame minority groups are routinely held to fall outside the protection of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). This, I argue, has diluted the robust speech protections previously associated with the ECtHR's celebrated precedent in Handyside v The United Kingdom (1976), a landmark case on the freedom of expression and its boundaries. As a result, the ECtHR's jurisprudence increasingly reflects not a balancing of rights, but an asymmetric favoring of state-defined "tolerance" over pluralistic expression. This approach risks insulating majoritarian or institutional viewpoints from critique under the guise of promoting social cohesion.

From allowing speech that may "shock, offend, disturb" to prohibiting offense, insult and ridicule

The ECtHR famously held in Handyside that Article 10 on the right to freedom of expression protects not only inoffensive speech, but also that which "offends, shocks or disturbs." In theory, this forms the backbone of European free speech protection. In practice, however, the ECtHR's hate speech rulings suggest a growing willingness to subordinate the Handyside principles to vague concepts such as the values and spirit of the Convention, particularly when the speech in question targets protected characteristics such as religion, ethnicity, or sexual orientation.

The paradigmatic shift can be traced most clearly to Féret v Belgium (2009), where a far-right member of parliament was criminally convicted for distributing anti-immigration leaflets during an election campaign. The ECtHR upheld the conviction, holding that statements such as "Stop the Islamization of Belgium," were likely to arouse feelings of "distrust, rejection or hatred" and thus justified interference. In a blistering dissent, Judge András Sajó warned that the majority had abandoned the foundational principle that speech must be protected especially "when we face ideas that we abhor or despise." He cautioned that "humans, including judges, are inclined to label positions with which they disagree as unacceptable and therefore beyond the realm of protected expression." According to Judge Sajó, the Féret majority treated the public as susceptible "nitwits," incapable of resisting emotional manipulation. This marked the emergence of a paternalistic framework: citizens need protection not just from direct harm, but from exposure to ideas the ECtHR deems offensive.

The "Féret doctrine" spreads: Le Pen, Zemmour and beyond

In the years since Féret, the ECtHR has cited and silently applied its logic across a range of cases. In Le Pen v France (2010), the ECtHR dismissed, without a full Article 10 review, a complaint from Jean-Marie Le Pen after he was fined for warning of a Muslim "conquest." As in Féret, there was no incitement to violence or unlawful acts, but the ECtHR found the statement "likely to arouse a feeling of rejection and hostility." In Zemmour v France (2022), journalist and politician Eric Zemmour was fined for claiming on live television that Muslims in France represent a form of "territorial occupation." The ECtHR again upheld the penalty, invoking Féret's reasoning that hate speech includes "insults, ridicule or defamation" without needing to cross into incitement. Despite acknowledging the statements touched on a matter of public interest, immigration and national identity, the ECtHR found that Zemmour's words were "not merely criticisms of Islam" but rather calls to marginalize Muslims. While Article 17 which prohibits the abuse of rights provided for by the ECHR was not formally applied, the ECtHR declared that the statements were "not protected under Article 10 in light of Article 17," blurring the boundary between exclusion and interpretation.

Political speech: still protected?

The ECtHR purports to give enhanced protection to political speech, especially during election periods. But its recent hate speech rulings appear to exempt themselves from this norm. In Féret, the ECtHR held that alleged racist speech becomes more harmful in electoral contexts, since it may "contribute to stir up hatred and intolerance." This logic was reiterated in Zemmour, where the applicant's public profile and media reach were cited as reasons for heightened responsibility. But as the dissenters in Féret argued, this effectively reverses the burden: instead of acknowledging the value of robust public debate, the ECtHR uses influence as a reason to silence it. What we are witnessing is not a careful balancing between expression and harm, but a presumption against controversial speech, especially from populist or right-wing politicians. The danger, of course, is that courts begin to enforce viewpoint-based restrictions under the cover of neutrality.

Elastic concepts of harm

A central concern throughout these cases is the ECtHR's failure to define the harm that justifies speech restriction. The ECtHR rarely explains how contested speech threatens democracy, minority rights, or public order in any concrete sense. It invokes abstract notions which it does not extrapolate on such as "social tension" and "trust in democratic institutions" but provides no standard for measuring these effects or proving a causal link between the speech and its consequences. In Féret, the ECtHR did not assess whether the applicant's leaflets led to hostility or discrimination, nor whether less restrictive measures could address the concerns. Instead, it accepted the government's position that the speech was harmful, treating emotional or reputational discomfort as sufficient for criminal sanctions. This trend continued in Lilliendahl v Iceland (2020), where a man was fined for online comments describing LGBTQ people as "sexual deviants." The comments were not widely disseminated nor where they uttered by a politician or someone else with a certain standing, yet the ECtHR upheld the penalty, holding that the expression of "disgust" itself justified restriction.

Platform, audience, and inconsistency

Another inconsistency concerns how the ECtHR weighs the medium and reach of speech. In Karataş v Turkey (1999), the ECtHR found that Kurdish nationalist poetry did not violate Article 10, partly because poetry reaches a relatively small audience. But in Lilliendahl, the limited reach of the speech (online comment under a news article) made no difference to the outcome. By contrast, in Soulas and Others v France (2008), the ECtHR found that a book's accessible style and wide distribution contributed to its potential harm. These cases reveal a lack of guiding principle. Sometimes reach matters, sometimes it doesn't. This inconsistency undermines legal predictability and reinforces the risk of arbitrary enforcement.

Toward a more coherent standard

While the ECtHR's goal of combating discrimination is principled and essential, its current trajectory in hate speech jurisprudence risks undermining the very values it seeks to protect. What is needed now is a recalibration, one that restores coherence to the ECtHR's speech doctrine and ensures that freedom of expression remains a meaningful safeguard in pluralistic democracies. At the heart of this recalibration should be a renewed commitment to the Handyside principle: the recognition that freedom of expression must extend not only to inoffensive or widely accepted speech, but also, and especially, to speech that shocks, offends, or disturbs. This foundational standard should not be treated as a rhetorical preface to judgments that ultimately uphold restrictions; it must serve as a guiding framework with substantive weight in legal reasoning. Crucially, the ECtHR must also articulate clearer thresholds for what constitutes hate speech, particularly in cases where the expression does not advocate violence or unlawful conduct. The current doctrine, where insult, ridicule, or prejudice alone can justify criminal penalties, leaves too much room for subjective interpretation and state overreach and is an anathema to the fundamental right to freedom of expression. A coherent standard requires more than abstract appeals to "social cohesion" or "democratic values"; it demands precise legal tests that distinguish between expression that merely causes discomfort and that which poses a demonstrable risk to the rights of others. To that end, restrictions on speech should be grounded in concrete evidence of harm. The ECtHR must move beyond assumptions about potential emotional injury or speculative societal disruption and instead require rigorous justification for why a particular expression crosses the threshold into legally punishable hate speech. Vague invocations of public order or institutional trust are insufficient when what is at stake is the criminalization of speech in democratic societies. Throughout the book I argue that the ECtHR must turn to the rich body of academic literature from legal and social science to support this recalibration.

Moreover, any interference with political expression must be subjected to strict scrutiny. Political discourse, even when provocative, lies at the core of democratic participation. It is in this domain that the doctrine of the margin of appreciation should narrow, not expand. Deference to national authorities cannot excuse the abdication of the ECtHR's supervisory role, particularly where laws risk silencing dissent or chilling public debate. If the ECtHR is to preserve its credibility as a guardian of democratic freedoms, it must apply these principles consistently. Protecting vulnerable groups and confronting discrimination are legitimate and necessary aims. But they must not come at the cost of abandoning the robust, principled protection of free expression. As things stand, the ECtHR's low-threshold paradigm threatens to turn Article 10 into a conditional liberty, available only to those who speak within the bounds of what is socially comfortable or politically acceptable. That is not the promise of the Convention. It is a warning sign.

[UPDATE 10:31 am from EV: Sorry, originally posted this under my own name, but it's of course Natalie Alkiviadou's guest-post; just corrected this.]

The post Hate Speech and the European Court of Human Rights: The Low Threshold Hatred Paradigm—When "Offence" Is Enough to Restrict Speech appeared first on Reason.com.

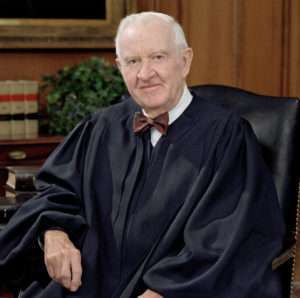

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 16, 2019

7/16/2019: Justice John Paul Stevens died.

Justice John Paul Stevens

Justice John Paul StevensThe post Today in Supreme Court History: July 16, 2019 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Wednesday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Wednesday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

July 15, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Interesting Third Circuit Statutory / Procedural Immigration Case

A short excerpt from today's long opinion by Judge Arianna Freeman, joined by Judge Cheryl Ann Krause, in Qatanani v. Attorney General:

The Supreme Court has long recognized that the admission and exclusion of noncitizens is a "fundamental sovereign attribute exercised by the Government's political departments largely immune from judicial control." But in that endeavor, both political branches have particular roles to play.

On the one hand, the Executive has authority to enforce the immigration laws passed by Congress and to exercise the discretion Congress delegates to it. On the other hand, "the formulation of [immigration] policies is entrusted exclusively to Congress." Indeed, there is "no conceivable subject" over which the "legislative power of Congress [is] more complete" than the admission and exclusion of noncitizens. In this balance, it is the Judiciary's exclusive province to resolve separation-of-powers questions. So where an administrative agency purports by regulation to evade procedures mandated by Congress in the Immigration and Nationality Act ("INA"), it is incumbent upon us to intervene. We do so here.

In 1996, Mohammad M. Qatanani was admitted to the United States on a work visa. In 1999, he applied under 8 U.S.C. § 1255(a) to adjust his immigration status to that of a Lawful Permanent Resident ("LPR"). After lengthy proceedings regarding Qatanani's application, an Immigration Judge ("IJ") twice made fact findings and credibility determinations in Qatanani's favor and granted his application to adjust to LPR status. The IJ issued those orders in 2008 and 2020, respectively.

The IJ's 2008 order never became final; the Department of Homeland Security ("DHS") appealed the order within the 30-day period permitted for it to do so. On appeal, the Board of Immigration Appeals ("BIA") vacated the IJ's order and remanded the matter to the IJ for further proceedings. Those proceedings led to the IJ's April 2020 order that again granted Qatanani's application to adjust to LPR status.

DHS did not appeal the IJ's April 2020 order within 30 days, so that order became final. As part of Congress's regime for adjustment to and recission of LPR status, the Attorney General was then required to memorialize that final order by recording Qatanani's admission with LPR status as of the date of the IJ's April 2020 order. And Congress specified how the Attorney General could rescind that LPR status if warranted: Within five years of the adjustment date, the Attorney General could commence proceedings pursuant to § 1256(a).

But here, the Attorney General evaded that statutory path. Instead, the BIA invoked an agency regulation to "self-certify" an appeal of the IJ's April 2020 order eleven months after that order issued. And at the conclusion of those self-certified appeal proceedings, the BIA issued an order purporting to reverse the IJ's April 2020 order and to order Qatanani removed from the United States. Qatanani petitioned us for review of the BIA's decision.

The BIA exceeded its authority when it attempted to undo Qatanani's adjustment to LPR status by using an agency regulation in a manner inconsistent with the procedures set out by Congress in the INA. Accordingly, we granted Qatanani's petition for review and vacated the BIA's order….

Qatanani is Palestinian and a citizen of Jordan. He was born in the West Bank and lived there until he finished high school. In 1982, he began studying at the University of Jordan, where he earned his bachelor's and master's degrees and a Ph.D. In 1989, he began working as an Imam in Jordan.

In 1993, Qatanani traveled to the West Bank with his wife and children to renew his residency card. While there, he was detained, beaten, and interrogated by the Israeli military. Upon his release, Israeli authorities renewed Qatanani's residency card.

In 1996, Qatanani was admitted to the United States, along with his wife and then four children, on a non-immigrant H1-B visa to serve as an Imam at the Islamic Center of Passaic County ("Islamic Center") in Paterson, New Jersey. In 1998, the Immigration and Naturalization Service determined that Qatanani was eligible to receive an immigrant visa. On April 1, 1999, when his H1-B visa was set to expire, Qatanani applied to adjust his status to LPR. On his application form ("I-485 application"), Qatanani checked a box stating that he had not been arrested or imprisoned for violating a law or ordinance within or outside the United States.

In 2005, while his I-485 application was still pending, Qatanani requested a meeting with the Federal Bureau of Investigation ("FBI") and Immigration and Customs Enforcement ("ICE") to inquire about the reason for the delay. In February 2005, an FBI agent and an ICE agent conducted a voluntary interview in which Qatanani disclosed that the Israeli military detained him in the West Bank in 1993. The agents informed United States Citizenship and Immigration Services ("USCIS") that Qatanani had been arrested and possibly convicted in the West Bank, and officials reached out to Israeli authorities to obtain records.

In May 2006, USCIS interviewed Qatanani regarding his I-485 application. The USCIS officer presented a declaration executed in January 2006 by the FBI agent who conducted the February 2005 interview. Qatanani and his counsel, who were seeing the declaration for the first time, objected that its contents were inaccurate and that they needed more time to review the document. The interview was terminated soon thereafter, and there was no subsequent USCIS interview.

In July 2006, USCIS denied Qatanani's I-485 application. It stated that Qatanani was inadmissible because he made a material misrepresentation in his application. Relying on the FBI agent's declaration, USCIS found that, in the February 2005 interview, Qatanani admitted that he was arrested, pleaded guilty to a crime, and was imprisoned for three months by Israeli authorities in the West Bank in 1993. Accordingly, USCIS found that Qatanani made a material misrepresentation when he stated on an immigration form that he had never been arrested, charged, or imprisoned for violating any law or ordinance. USCIS also denied Qatanani's application in the exercise of discretion.

That same day, ICE placed Qatanani in removal proceedings. Qatanani appeared before the Newark Immigration Court and conceded his removability. As relief from removal, he renewed his request for adjustment of status before the Immigration Court.

After receiving voluminous documents in evidence and holding a hearing over four days, the IJ granted Qatanani's application for adjustment of status. In a lengthy opinion issued in 2008, the IJ found that Qatanani was admissible and that he merited adjustment of status as a matter of discretion.

The IJ rejected the two grounds upon which DHS claimed that Qatanani was inadmissible. The first ground was alleged engagement in terrorist activity. Specifically, DHS claimed that Qatanani provided material support to Hamas. DHS based this claim in large part on documents it obtained from the Israeli military. Those documents state that, in 1993, a military court convicted Qatanani of two charges: (1) membership in an unlawful association (specifically, Hamas) and (2) performing a service for an unlawful association.

The IJ conducted a detailed discussion of the evidence. Among other concerns, the IJ stated that the documents from the Israeli military were premised on a written confession that was absent from the record. The IJ found that the military court was internationally stigmatized for failing to meet fair-trial standards, and even the Israeli Supreme Court had condemned it for abusive treatment to coerce confessions from detainees during the time of Qatanani's detention. The IJ also found it "perplex[ing]" and "remarkable" that the Israeli military would convict Qatanani (who refused to cooperate or become a spy for Israel) of being a member of Hamas and then release him after three months and renew his West Bank residency permit. Because the military court documents were "highly questionable, fail to clarify the identity of the respondent[,] and border on being, flatly stated, unreliable," the IJ gave the documents "very low evidentiary weight." He found they did not prove Qatanani engaged in terrorist activity.

In addition to the military court documents, two DHS witnesses—the FBI agent and the ICE agent who interviewed Qatanani in 2005—testified that Qatanani admitted during the interview that he was arrested for being a member of Hamas. In Qatanani's own testimony, he maintained that he had not done so. The IJ found Qatanani credible. But the IJ recounted numerous examples of the FBI agent's evasive, unresponsive, implausible, and contradictory answers that caused the IJ to disregard the FBI agent's testimony as unreliable. The IJ also explained that the ICE agent contradicted herself in her testimony, which was further undermined by DHS's failure to present the documents the ICE agent reviewed to prepare for her testimony. As a result, the IJ did not credit either agent, leaving Qatanani as the "only one of the three that has been consistent" about whether he was detained in 1993 or whether he was arrested and convicted.

The other grounds DHS raised to support its allegation that Qatanani engaged in terrorist activity were Qatanani's possible associations with members of Hamas and his one-time transfer of money to the West Bank. But, upon review of the evidence, the IJ found none of Qatanani's associations were improper, and DHS presented no evidence that the money Qatanani transferred to the West Bank came from an illegal source or was used for an illegal purpose. So the IJ found that Qatanani was not inadmissible for having engaged in terrorist activity….

[More details available in the opinion. -EV] …

And a short excerpt from Judge Paul Matey's long dissent:

For more than a quarter century, five Presidents and ten Attorneys General have objected to Mohammad Qatanani's presence in our Nation. After his three-year allowance ended in 1999, these Executives and their representatives determined, over and again, that Qatanani must leave. Yet today, this Court makes him a lawful permanent resident because we have lost the "respect for the functions of the other branches," which was grounded in "a judicial attitude founded in law and hallowed by time" that "sees judicial review of agency action and executive action as sensitive business" deserving deference. Our decision today forgets that humility and adds another impediment to the Executive's ability to carry out his duty to take care of immigration matters, a power that is both derived from congressional will and inherent in any sovereign.

Nearly thirty years ago, the same year Qatanani arrived for his "temporary" visit to the United States, Congress, in an action praised by then-President Clinton as a "landmark immigration reform" that "strengthens the rule of law by cracking down on illegal immigration at the border,"1 acted to "'protec[t] the Executive's discretion' from undue interference by the courts." I would respect that political judgment, mindful that "[n]o one, so far as my search of the several constitutional records uncovered, look[s] to the Court for 'leadership' in resolving problems that Congress, the President … failed to solve." So with due regard for the political branches' control over immigration, I would dismiss Qatanani's petition….

{As the majority notes, Qatanani was detained and questioned by Israeli forces upon crossing into the West Bank from Jordan in 1993. From 1985 to 1991, Qatanani was an active member in the Muslim Brotherhood, which led to Israeli suspicion that Qatanani was a "member of the Islamic Resistance Movement; also known as HAMAS" because "HAMAS had been formed from the Muslim Brotherhood" in 1987. The same year Qatanani was detained by Israeli forces, Qatanani met with his now deceased brother-in-law, Sumaia Abu Hanoud, whom Qatanani himself described as the "military leader of HAMAS." Despite Qatanani's acknowledgment of Hanoud's leadership in Hamas, Qatanani's wife and her brothers have "denied the relationship between Mr. Hanoud and HAMAS when questioned by the U.S. authorities."}

[Here too, more details available in the opinion. -EV] …

For more on Judge Matey's First Amendment analysis (which goes beyond the statutory and procedural questions that the panel majority focused on), see this post.

The post Interesting Third Circuit Statutory / Procedural Immigration Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Defending the Court of International Trade Ruling Against Trump's Tariffs—A Reply to Estreicher and Babbitt [Updated]

[Estreicher and Babbitt are right to conclude that Trump's tariffs violate the nondelegation doctrine, but wrong to reject other arguments against them.]

NA

NA In a recent Just Security article, NYU law Prof. Samuel Estreicher and attorney Andrew Babbitt criticize the May 28 Court of International Trade ruling against Trump's IEEPA tariffs, in VOS Selections, Inc. v. Trump, a case brought by the Liberty Justice Center and myself, on behalf of five small businesses harmed by the tariffs. The case is now on appeal before the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

Estreicher and Babbitt (EB) actually agree with us and the court that the tariffs are illegal! They just don't like much of the CIT's reasoning, and would prefer a ruling based on nondelegation doctrine. In this respect, they are similar to some previous critics of the ruling who support the result, but object to the reasoning, most notably John Yoo. He takes the exact opposite position: that CIT should have relied on the statutory text, rather than nondelegation and major questions doctrine (see my response to Yoo here).

EB overlook the fact that the CIT ruling did in fact rely, in part, in parton nondelegation. In addition, the other grounds for the court's decision are much stronger than they realize.

EB agree with us that Trump's interpretation of IEEPA grants the president virtually unlimited power to impose tariffs, and also agree that such boundless delegation violates constitutional constraints on delegation of legislative power to the executive. They chide the CIT for supposedly avoiding this constitutional issue. But CIT did not avoid it! The court's decision specifically states that "any interpretation of IEEPA that delegates unlimited tariff authority is unconstitutional." It clearly relied on this point as an additional reason to rule against the administration.

The CIT also relied on the closely related major questions doctrine (MQD), which requires Congress to "speak clearly" when authorizing the executive to make "decisions of vast economic and political significance." EB complain that MQD may not apply here, because it is not clear that it applies to presidential actions, as opposed to those of administrative agencies. But there is no good reason to exempt the president from MQD scrutiny, and three federal circuit courts have ruled that way. This point is further reinforced by the Supreme Court's increasing embrace of "unitary executive" theory, under which the president is entitled to near-total control over executive branch subordinates, thus making distinctions between them illusory. For more on this point, see our appellate brief in the case (pp. 51-53).

EB also note that MQD applies with greater force when an assertion of executive power is unprecedented. But, as they acknowledge, no previous president has ever used IEEPA to impose tariffs at all, much less on a scale large enough to start the biggest trade war since the Great Depression. It is true, as they emphasize, that President Nixon used IEEPA's predecessor statute, the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), to enact more limited tariffs, and this was upheld by the predecessor court to Federal Circuit in United States v. Yoshida International Inc. (1975). But the Yoshida court specifically stated it was not endorsing unlimited tariff authority. It emphasized that the Nixon tariffs were linked to the preexisting tariff schedule set by Congress, and that "[t]he declaration of a national emergency is not a talisman enabling the President to rewrite the tariff schedules." It even noted that to "sanction the exercise of an unlimited [executive] power" to impose tariffs "would be to strike a blow to our Constitution."

Thus, Yoshida actually refused to interpret TWEA as endorsing the kind of unlimited tariff authority Trump asserts under IEEPA. Moreover, we cannot assume that the even the more limited tariff authority Yoshida allowed continues under IEEPA, merely because the latter statute used wording similar to TWEA. Congress wanted IEEPA to be more limited than TWEA, and specifically emphasized it could only be used to address an "emergency" that amounts to a "unusual and extraordinary threat…. to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States" (concepts that were supposed to be narrowly defined and not a "normal" state of affairs). Trade deficits - the rationale for the Liberation Day tariffs at issue in our case - are neither an emergency, nor extraordinary, nor unusual, nor a threat (for more on these points see the excellent amicus brief in our case, filed by a cross-ideological group of leading economists).

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that IEEPA doesn't actually authorize tariffs at all. The statute does not even mention the word "tariff" or any synonym such as "duty" or "impost." All it allows is the power to "regulate" certain international economic transactions. Regulation and taxation are historically distinct powers, separately listed in the Constitution. The CIT decision deliberately chose not to address this issue. But in the Learning Resources case, decided a day later, Judge Rudolph Contreras of the US District Court for the District of Columbia (DDC) did address this question and correctly ruled IEEPA doesn't allow tariffs.

EB argue that Judge Contreras got this issue wrong, but they have no good reason for that claim, other than just relying on the Yoshida precedent (which itself provides little analysis justifying its conflation of taxation and regulation). If "regulate" inherently implies a power to impose taxes or tariffs, that would render the constitutional grant of power to Congress to "lay and collect… Duties, Imposts and Excises" superfluous, since the Constitution also gives Congress the power to "regulate" international commerce. Moreover, it would mean all of the many statutes that give some federal agency a power to "regulate" an activity also give it the power to impose taxes, which would be a massive expansion of executive branch taxation authority.

In addition, as Judge Contreras points out, this interpretation of IEEPA would render it unconstitutional, because the language of the statute applies to regulation of exports, as well as imports:

IEEPA provides that the President may "regulate . . . importation or exportation." 50 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(1)(B). The Constitution prohibits export taxes. See U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 5 ("No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State."). If the term "regulate" were construed to encompass the power to impose tariffs, it would necessarily empower the President to tariff exports, too. The Court cannot interpret a statute as unconstitutional when any other reasonable construction is available. See Nat'l Fed'n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519, 563 (2012).

Given these realities, there is every reason to confine Yoshida's reasoning to the narrow range of tariffs it upheld under TWEA, and not apply it to IEEPA at all. Even if Yoshida does apply, it explicitly rejects the kind of sweeping tariff authority claimed by the Trump Administration.

In sum, I completely agree with EB that it would be good if appellate courts struck down Trump's IEEPA tariffs under the nondelegation doctrine. Indeed, I have said as much since my very first piece on the subject, back in February (the post that eventually led to the filing of our case).

But there are also multiple additional reasons to rule against the tariffs, including 1) IEEPA doesn't authorize tariffs at all, 2) trade deficits are not an "emergency" or an "unusual and extraordinary threat" 3) deficit-related tariffs are now governed by the Trade Act of 1974 (a point noted by the CIT), not IEEPA, 4) the major questions doctrine, and 5) constitutional avoidance (relied on by both CIT and Judge Contreras). We cover all these in much more detail in our Federal Circuit brief.

UPDATE: EB also criticize the part of the CIT decision striking down Trump's fentanyl-related IEEPA tariffs imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China, which held that the tariffs in question do not actually "deal with" the fentanyl problem (IEEPA states that the statute can only be used to "deal with" the "unusual and extraordinary threat" it is invoked to address). This part of the decision relates not to our case, but to that brought by twelve state governments (decided in the same ruling).

EB argue the CIT's reasoning on "deals with" would inhibit all other efforts to use IEEPA sanctions as leverage, such as their use against Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Not so. There is an obvious difference between the Russia sanctions and Trump's fentanyl tariffs. The Russian government is obviously responsible for its attack on Ukraine and pressuring Russia to stop its own wrongdoing is an obvious way of "dealing with" the threat it poses. In addition, reducing the flow of money to the Russian government reduces the resources available to it, and makes it harder for Vladimir Putin to continue his war. . By contrast, the flow of fentanyl from Canada to the US is negligible and pretty obviously not caused by the Canadian government; that from Mexico is overwhelmingly by US citizens returning home, and also not caused by the Mexican government. Thus, the fentanyl tariffs are not meaningfully dealing with the problem that supposedly justifies them, even assuming that cross-border drug smuggling qualifies as an "unusual and extraordinary threat" (which it doesn't, as such smuggling is a longstanding and virtually inevitable consequence of the War on Drugs, which predictably creates large black markets).

The post Defending the Court of International Trade Ruling Against Trump's Tariffs—A Reply to Estreicher and Babbitt [Updated] appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] May Aliens Be Denied Lawful Permanent Resident Status Based on Their Speech?

Third Circuit Judge Paul Matey argues yes, dissenting in Qatanani v. Attorney General. (The two judges in the panel majority seem to disagree, stating that "the [Board of Immigration Appeals] penalized Qatanani for quintessential First Amendment activity," but declines to discuss the matter in detail because it concludes Qatanani should prevail on statutory and procedural grounds.) Here's an excerpt:

Qatanani entered the United States in 1996 on a H-1B nonimmigrant visa with authorization to serve as an imam at The Islamic Center of Passaic Country (ICPC) until April 1, 1999. Rather than leave, he applied to adjust his status to lawful permanent residence (LPR). After almost two decades of administrative proceedings, an Immigration Judge (IJ) found Qatanani eligible for a status adjustment and deserving one as a matter of discretion. But the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) disagreed [in April 2024], noting Qatanani's lack of candor, admitted association with Hamas supporters, public call for a "new intifada," and failure to demonstrate yearly tax filings. As I explain below, I would not disturb the BIA's decision…. [Statutory and procedural details omitted. -EV]

Finally, I explain why the BIA's review of Qatanani's Times Square speech and admitted associations with Hamas supporters does not violate the First Amendment. Of course, an alien's speech can offer important insight into his character that informs the Executive's determination about whether the alien's presence will add to the common good. None disagree with that observation, nor does the First Amendment because Qatanani is not part of "the people" the First Amendment protects, nor is the denial of LPR status a punitive action….

[A]n alien "does not become one of the people to whom" the First Amendment applies "by an attempt to enter, forbidden by law." U.S. ex rel. Turner v. Williams (1904). That is because "[t]o appeal to the Constitution is to concede that this is a land governed by that supreme law, and as under it the power to exclude has been determined to exist, those who are excluded cannot assert the rights in general obtaining in a land to which they do not belong as citizens or otherwise." So there is no debate that excluded aliens cannot invoke the First Amendment.

Whether the First Amendment restrains government action against all aliens within our Nation's borders is less explored. Begin with Bridges v. California (1941), involving state contempt charges against a group including a resident alien lawfully within the country for at least two decades. With little analysis, the Court concluded the contempt charge was impermissible under the First Amendment. But the Court did not mention, let alone analyze, Bridges's alien status.

A few years later, the Court considered whether Bridges, still a lawful resident alien, was removable under 8 U.S.C. § 137(f) for affiliation with the Communist Party. Bridges v. Wixon (1945). The majority saw insufficient evidence of his alleged membership but, in dicta, wrote that "[f]reedom of speech and press is accorded aliens residing in this country," citing only the earlier decision in Bridges v. California. Concurring, Justice Murphy wrote that the statute was unconstitutional and that all aliens lawfully within our borders receive "the immutable freedoms guaranteed by the Bill of Rights," including freedom of speech. But Chief Justice Stone and Justices Roberts and Frankfurter found no fault with the statute based on Congress's "plenary power over the deportation of aliens." So Wixon does not resolve whether the First Amendment applies to all resident aliens, much less unauthorized aliens. At most, its dicta suggests that lawful resident aliens, what we today could call LPRs, can potentially invoke the First Amendment in some criminal prosecutions.

{Little has been clarified since Wixon. The Court has continued to acknowledge lawful resident aliens receive First Amendment protections, but it has never held the First Amendment restrains government action against aliens with less protective status. See, e.g., United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez (1990). Some decisions correctly understand Wixon to address no more than LPRs. See, e.g., OPAWL - Bldg. AAPI Feminist Leadership v. Yost (6th Cir. 2024); Nat'l Council of Resistance of Iran v. Dep't of State (D.C. Cir. 2001). But others read Wixon with less nuance and assume any alien within the country holds First Amendment guarantees, regardless of whether the alien is an LPR, only has temporary authorization to be in the country, or is here illegally. See, e.g., Kim Ho Ma v. Ashcroft (9th Cir. 2001); Underwager v. Channel 9 Austl (9th Cir. 1995); Am.-Arab Anti-Discrimination Comm. v. Reno (9th Cir. 1995).}

Our Nation's longstanding practice also yields few insights, as there is no unbroken chain of understanding or "regular course of practice" that might "liquidate & settle the meaning" of the First Amendment's applicability to aliens. Nor is there any evidence of "a governmental practice [that] has been open, widespread, and unchallenged since the early days of the Republic," that might "guide our interpretation." All to say, there is no long standing post-enactment practice—custom, we might properly call it—recognizing all aliens within our borders possess First Amendment rights….

But lack of precedent and practice does not mean an absence of answer derived from "the natural principles that support our legal tradition," which are the "certain 'primary truths, or first principles, upon which all subsequent reasoning must depend.'"

We know that many aliens within our borders do not enjoy constitutional protections against state action. Much like the Preamble and the Second, Fourth, Ninth, and Tenth Amendments, the First Amendment uses the term "the people," referring "to a class of persons who are part of a national community or who have otherwise developed sufficient connections with this country to be considered part of that community." Only as an alien "increases his identity with our society" do the "generous and ascending scale of rights" spring into action, some of which include the "constitutional provisions [that] extend beyond the citizenry." But neither "lawful but involuntary" entry, nor mere physical entry without "significant voluntary connection[s]," suffice for an alien to become part of "the people."

This distinction makes sense, as it has long been accepted that a sovereign's laws, including restrictions and privileges, extend only to "persons and things within its own territory according to its own sovereign will and public policy." This understanding was viewed as "inherent in nature, for it was derived from an underlying assumption about the essential purpose of government, protection, which in turn was derived from ideas about the equal freedom of human beings in the state of nature." Thus, "an individual ha[s] a right to the protection of government and its laws only by virtue of his allegiance."

Eighteenth-century thinkers recognized this principle as following the nature of things, making protectionism "a truism of the common law." "[F]ounded in reason and the nature of government," "[a]llegiance is the tie, or ligamen, which binds the subject to the king, in return for that protection which the king affords the subject." Blackstone, Commentaries. But an alien falls into an "obvious division," because he owes only a "[l]ocal allegiance" to the Sovereign, a temporary affinity "for so long time as he continues within the king's dominion and protection … and it ceases the instant such stranger transfers himself from this kingdom to another." …

The Founders followed this understanding of the reciprocal relationship between allegiance and protection. Though they sometimes split over whether the principle of protection entitled aliens to the benefit of all constitutional rights, as contested during the debates over the Alien and Sedition Acts, all acknowledged that some relationship between the Sovereign and the alien was essential. Leading the Democratic-Republicans, James Madison contended "[a]liens are not more parties to the laws than they are parties to the Constitution; yet it will not be disputed that, as they owe, on the one hand, a temporary obedience, they are entitled, in return, to their protection and advantage." And even the Federalists—who reasoned that because aliens were not part of the people for whom the Constitution was created and thus have no rights thereunder—still recognized the protection principle. Thus, despite disagreement about what laws aliens were entitled to the protection of, the principle of protection was universally accepted. And early American law adhered to this understanding.

This history, and the tradition it follows, reveals three insights. First, the protection principle confers only a temporary license to aliens—a discretionary privilege to be within the land—so it cannot guarantee a right to indefinitely remain. That is because "[n]atural allegiance is therefore perpetual, and local temporary only."

Second, the relationship between the alien and the Sovereign can be terminated by "the express will of the sovereign power to order him away." Although "a vested right is to be taken from no individual without a solemn trial, … the right of remaining in our country is vested in no alien; he enters and remains by the courtesy of the sovereign power, and that courtesy may at pleasure be withdrawn." So "even as to alien friends, one who is ordered away or is present without permission would be outside the public protection."

Third, a temporary license does not confer aliens access to all rights enjoyed by citizens. "[T]he sovereign is supposed to allow [an alien] access only upon this tacit condition, that he be subject to the laws" limited to "the general laws made to maintain good order, and which have no relation to the title of citizen or of subject of the state." So "submitting to the laws of any country, living quietly, and enjoying privileges and protection under them, makes not a man a member of that society." Which explains why aliens had "circumscribed" rights such as a prohibition on political engagement and property ownership. The same thinking animated the Federalists' position that aliens cannot claim the Constitution's protection because, although the protection principle applies, the alien is not party to the Constitution.

All told, the protection principle establishes that the Sovereign does not owe all aliens within its borders the same obligation it does its citizens. Thus, Congress may make rules for aliens that would be unacceptable if applied to citizens.

{Arguments to the contrary violate not only precedent but the political branches' plenary power over immigration. The Court has upheld removals based on determinations that an alien's speech or association demonstrated undesirability sufficient to terminate the privilege of presence. See Harisiades v. Shaugnessy (1952) (rejecting the argument that the First Amendment barred removal of three based on their associations with the Communist Party); Kleindienst v. Mandel (1972) (upholding an alien's exclusion based on his speech the Sovereign deemed undesirable, regardless of citizens' First Amendment rights to hear that alien's speech); Reno v. Arab-Am. Anti-Disc. Comm. (1999) ("When an alien's continuing presence in this country is in violation of the immigration laws, the Government does not offend the Constitution by deporting him for the additional reason that it believes him to be a member of an organization that supports terrorist activity."). And proper respect for the political branches' plenary power over immigration has repeatedly moved the courts against second guessing their judgment. See, e.g., Reno (declining to enjoin deportation proceedings based on the aliens' claim that they were selectively targeted for deportation because of their affiliations); Galvan v. Press (1954) (upholding constitutionality of deporting an alien based on his associations with the Communist Party despite First Amendment concerns); Kleindienst (courts may neither "look behind" the "facially legitimate and bona fide" denial of immigration waiver, nor weigh it against asserted "First Amendment interests"); United States v. Aguilar (9th Cir. 1989) (rejecting an alien's claims under the First Amendment in light of "the government's overriding interest in policing its borders").

Under the best understanding of the First Amendment, Qatanani is not part of "the people" whom the First Amendment restricts government action against, and he cannot claim its protection. At the time of the BIA's decision, Qatanani was not subject to the protection principle. He entered the country with permission via a non-immigrant H1-B visa to work for a limited time. During those three years, Qatanani was within the country with the express permission of the Sovereign and owed temporary allegiance in exchange for a temporary license. But once the visa expired, so did the protection principle. If not then, surely when USCIS denied his initial status adjustment application or when DHS initiated removal proceedings against him. No matter what date, the Executive had removed authorization for Qatanani to remain many years before he publicly called for a new intifada….

Even if Qatanani were afforded First Amendment protection as an unauthorized alien (or even an LPR), denial (or recission) of an immigration privilege, to which he has no right or entitlement, is not a punitive or adverse action that could trigger First Amendment restrictions on government action. Through the Constitution, "[t]he people of the United States … limit[ed] the power of their government over themselves; but la[id] no restraint on the power of their government over aliens." So until an alien "become[s] [a] citizen[ ], they are in the power of the ordinary legislature," which "may receive them, and admit them to become citizens; or may reject them, or remove them, before they become citizens." Thus, when aliens "come here, they know, that they come at the discretion of the ordinary legislature … and have no reason to complain, if this legislature remove them, before they become citizens." Put simply, an alien within our Nation as a matter of administrative grace has no right to remain.

That is why "[d]eportation is not a criminal proceeding and has never been held to be punishment." Rather, "[a] deportation proceeding is a purely civil action to determine eligibility to remain in this country, not to punish an unlawful entry, though entering or remaining unlawfully in this country is itself a crime." So "[w]hile the consequences of deportation may assuredly be grave, they are imposed not as a punishment" but "to bring to an end an ongoing violation of United States law."

The same is true for Executive determinations denying status adjustments because the legislature has not created a statutory entitlement to an adjustment of status under section 1255. To the contrary, Congress explicitly stated that the privilege of a status adjustment is purely discretionary and should be determined by the Executive. Immigration benefits differ from other benefits the Executive offers. True, neither Congress nor the Executive may condition the receipt of a government benefit in a manner that infringes constitutional rights. This principle has been applied to benefits such as "tax exemptions," "unemployment benefits," "welfare payments," and "denials of public employment." But legal status to enter or remain in our Nation is not an administrative benefit held out to all aliens who meet a strict set of qualifications. No. It is the highest privilege the political branches may grant to those individuals deemed, in their discretion, deserving of the opportunity to work towards the common good of our republic.

By design then, immigration determinations, without more, cannot serve as adverse actions against an alien, making appeals to First Amendment limitations inapposite.

UPDATE: My apologies; due to an editing error on my part, I originally wrote that Judge Matey answered the question "no," though of course as to the question that ended up being the title of the post, he answered the question "yes." I've corrected this; very sorry for the error.

The post May Aliens Be Denied Lawful Permanent Resident Status Based on Their Speech? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Richard Fallon R.I.P.

[The passing of a legal giant.]

Harvard law professor Richard Fallon passed away Sunday. He was an incredibly important and influential scholar and thinker. He was 73.

The Harvard Crimson reports:

A leading scholar in constitutional law, Fallon was widely regarded for his insightful, prolific academic output and his commitment to thoughtful debate.

He has written extensively about the Supreme Court and constitutional interpretation, tackling how the more than 200-year-old document applies to the country today. In 2021, he was nominated to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States, a committee established by then-President Joe Biden to investigate legal questions and possible reforms to the Supreme Court.

"HLS can be grateful for the more than forty years in which Professor Fallon wrote, taught, mentored, counseled, and led with extraordinary distinction," Goldberg wrote in the Monday announcement of Fallon's death. "His passing leaves a hole in our community that cannot be filled."

Fallon was also remembered by former students and colleagues for his humor and his down-to-earth nature — qualities many said could be uncommon in the rarefied halls of Harvard Law School.

Cass R. Sunstein, a professor at HLS, wrote in a statement to The Crimson that Fallon combined his intellectual "brilliance" with "humility in a way I have never seen in all my years."

Larry Solum has this remembrance on the Legal Theory Blog.

The post Richard Fallon R.I.P. appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers