Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 278

August 28, 2024

[Ilya Somin] Eighth Circuit Wrongly Struck Down Missouri's Gun Sanctuary Law—But Also Created a Roadmap for How Such Laws Can Escape Invalidation in the Future

[The court indicates the law would be constitutional so long as it does not claim to declare a federal law "invalid."]

(Nomadsoul1 | Dreamstime.com)

(Nomadsoul1 | Dreamstime.com) As co-blogger Jonathan Adler notes, on Monday the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, upheld a trial court decision striking down Missouri's Second Amendment Preservation Act (SAPA), the state's "gun sanctuary" law. I think the court got the decision wrong. But, in the process, it also essentially laid out a road map by which SAPA and other similar laws could survive judicial scrutiny with only cosmetic changes.

SAPA, like other gun sanctuary laws, bars state and local officials from helping to enforce various federal gun regulations that the state considers to be unconstitutional violations of the Second Amendment. Like the district court, the Eighth Circuit ruling recognizes that "Missouri may lawfully withhold its assistance from federal law enforcement." A long line of Supreme Court decisions has held that the federal government may not "commandeer" state and local governments into helping enforce federal law. In part on that basis, numerous federal court decisions struck down Trump Administration efforts to force liberal sanctuary cities and states to help enforce federal immigration law. Conservative gun sanctuary laws are an imitation of liberal immigration sanctuaries, albeit advancing a right-wing cause rather than a left-wing one.

Nonetheless, the Eighth Circuit struck down SAPA because the state statute says that the federal laws it targets are "invalid." While the state can refuse to help federal law enforcement, that "does not mean that the State may do so by purporting to

invalidate federal law."

This reasoning strikes me as wrong. All SAPA actually does is deny state assistance to federal efforts to enforce certain gun laws. I went over this point in detail in my analysis of the district court ruling. The law does not impede the federal government's own law enforcement efforts. The fact that the state's motive for denying assistance is a belief that the federal laws in question violate the Second Amendment and are therefore "invalid" should be immaterial.

There are situations where an otherwise permissible state law becomes unconstitutional due to illicit motivations (e.g.—if the law is motivated by racial or ethnic discrimination). But a belief that a given federal law is unconstitutional isn't one of them. That's true even if the state legislature is wrong to think the laws in question violate the Second Amendment. Even if these federal laws are perfectly constitutional, the state still has the constitutional authority to refuse to help enforce them.

Such denial of assistance is distinct from "nullification," with which it is often confused. When states try to "nullify" federal laws, as happened in conflicts over slavery, tariffs, and civil rights, they go beyond merely denying assistance to impending federal law enforcement efforts. SAPA and other gun sanctuary laws do not do that.

Another flaw in the Eighth Circuit decision is that it refuses to sever the part of SAPA it found unconstitutional from the rest of the statute, despite SAPA having an explicit severability clause: "We conclude that the law is not severable because the entire Act is founded on the invalidity of federal law." However, SAPA's statement of the reasons for the law ("invalidity") is severable from the operative portions of the statute (which bar state officials from helping to enforce the laws in question). I think the Eighth Circuit, like the district court, also ignored Missouri's requirement that state laws be interpreted to avoid unconstitutionality, where possible (federal courts must defer to state courts in interpreting state law). Here, that means the declaration of "invalidity" should be interpreted as only extending to state assistance to the feds, not any general invalidity of the laws within Missouri's border.

Despite these flaws, the Eighth Circuit ruling actually provides a road map for how Missouri can easily fix SAPA, and protect it against future legal challenges. It could bar state officials from helping to enforce the exact same federal laws, but do so without asserting that the laws are "invalid." Substantively, this revised SAPA would be exactly the same as the current version. But by avoiding references to "invalidity," the state can satisfy the test set up by the Eighth Circuit. After all, the court concedes (as it must) that Missouri has the right to "withhold its assistance from federal law enforcement." Other gun sanctuary states would be well advised adopt similar strategies, especially if they are within the Eighth Circuit's jurisdiction. The state can even still assert the laws in question violate the Second Amendment, so long as it recognizes that doesn't make them completely invalid until a court decision so holds.

If you think this is the kind of legal hair-splitting that makes people hate lawyers, I don't really disagree. But I'm not the one who created this somewhat silly distinction. The Eighth Circuit did.

In sum, this decision should not meaningfully impede state gun sanctuary laws, so long as state legislatures avoid references to the "invalidity" of the federal laws they want to stop state officials from helping to enforce.

Despite the legal and structural similarities between gun sanctuary laws and immigration sanctuaries, most who claim the former are illegal support the latter, and vice versa. I'm one of the relatively few people who support both. In my view, both types of sanctuaries protect valuable forms of liberty against federal overreach, and help empower people to vote with their feet. But, regardless of the policy merits, both are protected by constitutional restrictions on federal commandeering of state and local governments.

The post Eighth Circuit Wrongly Struck Down Missouri's Gun Sanctuary Law—But Also Created a Roadmap for How Such Laws Can Escape Invalidation in the Future appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Sarah Palin Gets New Trial in Libel Lawsuit Against N.Y. Times

["[T]he district court’s Rule 50 ruling improperly intruded on the province of the jury by making credibility determinations, weighing evidence, and ignoring facts or inferences that a reasonable juror could plausibly have found to support Palin’s case."]

From today's Second Circuit decision in Palin v. N.Y. Times Co., written by Judge John Walker and joined by Judges Reena Raggi and Richard Sullivan:

Plaintiff Sarah Palin appeals the dismissal of her defamation complaint against defendant The New York Times ("the Times") and its former Opinion Editor, defendant James Bennet, for the second time.

We first reinstated the case in August 2019 following an initial dismissal by the district court (Rakoff, J.) under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). Palin's claim was subsequently tried before a jury but, while the jury was deliberating, the district court dismissed the case again—this time under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 50. We conclude that the district court's Rule 50 ruling improperly intruded on the province of the jury by making credibility determinations, weighing evidence, and ignoring facts or inferences that a reasonable juror could plausibly have found to support Palin's case.

Despite the district court's Rule 50 dismissal, the jury was allowed to reach a verdict, and it found the Times and Bennet "not liable." Unfortunately, several major issues at trial—specifically, the erroneous exclusion of evidence, an inaccurate jury instruction, a legally erroneous response to a mid-deliberation jury question, and jurors learning during deliberations of the district court's Rule 50 dismissal ruling—impugn the reliability of that verdict.

The jury is sacrosanct in our legal system, and we have a duty to protect its constitutional role, both by ensuring that the jury's role is not usurped by judges and by making certain that juries are provided with relevant proffered evidence and properly instructed on the law. We therefore VACATE and REMAND for proceedings, including a new trial, consistent with this opinion….

The opinion is long (but readable), and interested readers should review the whole thing. But here a few excerpts; first, the factual background:

On June 14, 2017, the Times' Editorial Board published the editorial challenged in this case, entitled "America's Lethal Politics" …, which compared two political shootings. In the first attack, on January 8, 2011, Jared Loughner killed six people and injured thirteen others, including Democratic Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, during a constituent event held by Giffords in Arizona ("the Loughner shooting"). In the second, which took place in 2017 in Virginia on the day the editorial was published, James Hodgkinson seriously injured four people, including Republican Congressman Stephen Scalise, at a practice for a congressional baseball game ….

In comparing these two tragedies, the editorial made statements about the Loughner shooting that are the subject of this defamation action. It stated that there was a "clear" and "direct" "link" between the Loughner shooting and the "political incitement" that arose from a digital graphic published in March 2010 by former Alaska governor and vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin's political action committee ("the challenged statements")…..

{In full, the paragraphs of the editorial containing the challenged statements read [emphasis added]:

"Was [the Hodgkinson shooting] evidence of how vicious American politics has become? Probably. In 2011, when Jared Lee Loughner opened fire in a supermarket parking lot, grievously wounding Representative Gabby Giffords and killing six people, including a 9-year-old girl, the link to political incitement was clear. Before the shooting, Sarah Palin's political action committee circulated a map of targeted electoral districts that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized cross hairs.

Conservatives and right-wing media were quick on Wednesday to demand forceful condemnation of hate speech and crimes by anti-Trump liberals. They're right. Though there's no sign of incitement as direct as in the Giffords attack, liberals should of course hold themselves to the same standard of decency that they ask of the right."}

The graphic was a map that superimposed crosshairs over twenty congressional districts represented by Democrats—including Giffords' district. In fact, a relationship between the crosshairs map and the Loughner shooting was never established; rather, at the time of the editorial, the attack was widely viewed as a tragic result of Loughner's serious mental illness….

The idea of publishing an editorial about the Hodgkinson shooting was first raised by Elizabeth Williamson, a writer for the Times, on the morning of June 14, 2017 in an email to James Bennet and other members of the Times' Editorial Board. A follow-up email from Williamson indicated that Hodgkinson might have had "POSSIBLE … pro-Bernie, anti-Trump" views. Editorial Board members weighed in on Williamson's idea. Bennet asked "whether there's a point to be made about the rhetoric of demonization and whether it incites people to this kind of violence," adding that "if there's evidence of the kind of inciting hate speech on the left that we, or I at least, have tended to associate with the right (e.g., in the run-up to the Gabby Giffords shooting) we should deal with that."

Williamson conducted research for the editorial with the aid of the Board's editorial assistant, Phoebe Lett. Prompted by Bennet's suggestions, she asked Lett whether there was a prior Times editorial "that references hate type speech against [Democrats] in the runup to [the Loughner] shooting," since "James [had] referenced that." Lett forwarded the email to Bennet, who clarified that he was asking if the Times had "ever writ[ten] anything connecting … the [Loughner] shooting to some kind of incitement." He asked Lett to "send [him] the pieces [she] sent [Williamson]," and he forwarded to Williamson other pieces that he received from Lett. Specifically, Lett sent Bennet the following three Times articles, the first of which was sent to Williamson by Lett at Bennet's suggestion and the latter two of which Bennet forwarded to Williamson himself:

"No One Listened to Gabrielle Giffords" by Frank Rich (Jan. 15, 2011), which stated that "[w]e have no idea" whether Loughner saw the crosshairs map and referred to Loughner as being "likely insane, with no coherent ideological agenda," while also noting that that "does not mean that a climate of antigovernment hysteria ha[d] no effect on [Loughner]."

"Bloodshed and Invective in Arizona" by the Times' Editorial Board (Jan. 9, 2011), which noted that Loughner "appears to be mentally ill," indicated that Loughner does not fall into "usual ideological categories," and stated that "[i]t is facile and mistaken to attribute [the Loughner shooting] directly to Republicans or Tea Party members."

"As We Mourn" by the Times' Editorial Board (Jan. 12, 2011), which quoted then-President Barack Obama's statement that "a simple lack of civility … did not" cause the Loughner shooting and mentioned that Palin accused journalists of "committ[ing] a 'blood libel'when they raised questions about overheated rhetoric" in connection with the Loughner shooting.

Williamson drafted the editorial and uploaded it to "Backfield," part of the Times' content management system, in the late afternoon of June 14. Williamson's draft ("the initial draft") did not contain the challenged statements. It stated only that Loughner's "rage was nurtured in a vile political climate" and that the "pro-gun right [was] criticized" at the time of the Loughner shooting. It also noted that, before the shooting, Palin's political action committee had "circulated a map of targeted electoral districts that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized crosshairs." {The initial draft and the published editorial both incorrectly implied that the crosshairs symbols were placed on photos of Giffords and other Democratic representatives, rather than on their congressional districts.} The word "circulated" in the initial draft was hyperlinked to a January 9, 2011 ABC News article entitled "Sarah Palin's 'Crosshairs' Ad Dominates Gabrielle Giffords Debate" ("the ABC Article"), which stated that "[n]o connection ha[d] been made between [the crosshairs map] and the [Loughner] shooting."

Linda Cohn, an Editorial Board member, was the first person to edit the initial draft. After making her edits, Cohn asked Bennet to look at the piece, and Bennet added his own revisions to the draft. Bennet's changes were substantial: Williamson testified that Bennet "rewrote [her] editorial" and, after receiving a complimentary email from a colleague about the piece, Williamson responded that it "was mostly a [Bennet] production" and that Bennet had been "super keen to take it on." Bennet's edits added the challenged statements.

After saving his revisions in Backfield, Bennet emailed Williamson, noting that he "really reworked this one" and apologizing for "do[ing] such a heavy edit." Bennet also asked Williamson to "[p]lease take a look." Williamson responded seven minutes later that the revised piece "[l]ook[ed] great." Several other Times employees under Bennet also reviewed the revised draft prior to its publication and made minor edits, but none raised concerns regarding the challenged statements.. The editorial was published online on the Times' website at approximately 9:45 pm on June 14, 2017 and appeared in the Times' print edition the next morning….

After a swift public backlash, the Times revised the challenged statements and issued two corrections. The first correction was published on June 15, along with revisions to the challenged statements. The correction read: "An earlier version of this editorial incorrectly stated that a link existed between political incitement and the 2011 shooting of Representative Gabby Giffords. In fact, no such link was established." The second correction, released the next day, clarified that the map had overlaid crosshairs on Democratic congressional districts, not photos of the representatives themselves….

And an excerpt of the Second Circuit's legal analysis:

The central issue in this appeal is whether the evidence at trial was sufficient for Palin to prove that the defendants published the challenged statements with actual malice, as required for public-figure defamation plaintiffs….

The district court based its judgment for defendants solely on its conclusion that, as a matter of law, the trial evidence was insufficient to permit a jury to find that the defendants acted with actual malice. We disagree with that conclusion. After reviewing the record and making all reasonable inferences in Palin's favor as the nonmoving party, we conclude that there exists sufficient evidence, detailed below, for a reasonable jury to find actual malice by clear and convincing evidence.

Bennet's Testimony

During cross-examination by the defense, defendant Bennet, who was called as a witness by the plaintiff, stated what could be plausibly viewed as an admission: "I didn't think then and don't think now that the [crosshairs] map caused Jared Loughner to act." But the district court dismissed out of hand the possibility that Bennet's statement could be viewed as an admission supporting a finding of actual malice. The district court concluded that such an interpretation was "not a reasonable reading of Bennet's answer and … would be inconsistent with [his] testimony overall." Crediting Bennet's explanation that he did not intend to convey in the editorial that the crosshairs map directly caused Loughner to act, the district court interpreted Bennet's "admission" to be merely a statement that the question of whether the crosshairs map spurred Loughner's attack never entered his mind.

But in deciding a Rule 50 motion, a district court may not credit the movant's self-serving explanations or adopt possible exculpatory interpretations on his behalf when interpretations to the contrary exist. Furthermore, the district court was plainly incorrect to conclude that Bennet's testimony cannot "reasonabl[y]" be understood to "indicate[] that Bennet did not believe that what he was writing was true." Bennet's statement—that he "didn't think," when revising the editorial, that "the [crosshairs] map caused Jared Loughner to act"—can permissibly be read to suggest that Bennet entertained serious doubts as to his assertion that the map and shooting had a "clear" and "direct" "link." The jury may ultimately accept the district court's understanding of Bennet's words—but, as we previously cautioned, "it is the jury that must decide."

The ABC Article Hyperlink

The ABC Article hyperlinked in Williamson's initial draft—which remained in the article following Bennet's edits—unequivocally states that "[n]o connection has been made between [the crosshairs map] and the [Loughner] shooting." Had Bennet read this article, its contents would at a minimum allow a rational juror to plausibly infer that Bennet recklessly disregarded the truth when he published the challenged statements.

The district court erroneously ignored this potential inference, in part because it credited Bennet's denial that he had ever clicked the hyperlink and read the article. But a district court may not make credibility determinations when considering a Rule 50 motion and, "although the court should review the record as a whole, it must disregard all evidence favorable to the moving party that the jury is not required to believe." Here, the jury was not required to believe Bennet's testimony, which could be viewed as self-serving. The district court's acceptance of that testimony in the jury's stead improperly infringed on the jury's exclusive role.

The district court also erred in concluding that Palin "adduced no affirmative evidence" from which a jury could presume that Bennet read the ABC Article. Under our caselaw, inferential and circumstantial evidence can satisfy the "affirmative evidence" requirement …. Here, Williamson testified that, although editorial writers were "the first line of fact-checking" for the pieces they drafted, when "someone rewrote a draft" that someone else prepared, the person who did the rewrite had "primary responsibility for fact-checking the portion that they rewrote."

A jury could reasonably conclude that Bennet would therefore have been responsible for fact-checking the sentence containing the hyperlink to the ABC Article because, although his revisions to that sentence were minor, his revisions to the preceding sentence—where he added that "the link to political incitement was clear"—substantially changed the nature of the sentence that contained the hyperlink. A jury could also reasonably believe that such fact-checking obligations would include clicking on and reading through articles hyperlinked in the edited portions of an editorial draft to ensure the accuracy of any changes. And, thus, it could infer that it was more likely than not that Bennet read the ABC Article as part of his editing duties.

Prior Times Opinion Pieces

Bennet admitted at trial that, while conducting his editorial research, he "must have read" the three prior Times opinion pieces on the Loughner shooting that Lett sent to him and that he sent or had Lett send to Williamson (namely, "No One Listened to Gabrielle Giffords," "Bloodshed and Invective in Arizona," and "As We Mourn"). These articles were received into evidence, but the district court concluded that they "provide[d] no basis for finding that Bennet knew or suspected that his revision introduced false statements of fact into the [e]ditorial" because the articles do not "contradict the facts asserted in the [c]hallenged [s]tatements." We disagree. The articles can also be plausibly read as casting significant doubt on any link between the Loughner shooting and the crosshairs map. [Details omitted. -EV] …

Possible Prior Knowledge

The district court acknowledged that "Bennet theoretically could have had prior knowledge regarding the relationship—or lack thereof—between the crosshairs map and the [Loughner] shooting" outside of any research he conducted for the editorial. Its conclusion, however, that "the record belies this possibility," relied substantially on Bennet's self-serving testimony indicating that "he was not aware of the details of the Loughner case and that he did not recall the controversies surrounding the crosshairs map before the [e]ditorial was written." Such crediting of Bennet's testimony in resolving a Rule 50 motion was error.

Moreover, the district court's determination that "Palin offered no admissible evidence that would undermine Bennet's testimony" on this issue, ignored plausible inferences tending to support the conclusion that Bennet would have known when he revised the editorial that there was no link between the crosshairs map and the Loughner shooting…. The district court opinion similarly failed to consider evidence of Bennet's recall abilities…. [Details omitted. -EV]

Finally, as discussed [below] …, the district court also erred in excluding … additional circumstantial evidence of Bennet's potential prior knowledge. Namely, it improperly rejected: (1) the Excluded Articles, which Palin offered to show that Bennet "knew that the allegations of a link between Loughner and the [crosshairs] map had been discredited," and (2) evidence regarding Bennet's relationship with his brother, a Democratic U.S. Senator ("Senator Bennet"), which Palin argued "could establish bias" and "would have made … Bennet more likely to have been aware of the [crosshairs] map" and any controversy surrounding it. [Factual details on this omitted.—EV]

"Incompatible" Evidence

In addition to improperly discounting Palin's evidence, the district court also impermissibly viewed Bennet's evidence in the light most favorable to him. For example, it deemed "incompatible" with the conclusion that Bennet acted with actual malice (1) Bennet's compliance with the Times' standard editing process, (2) his attempted apology to Palin, and (3) his post-publication exchanges with Ross Douthat and other colleagues. In so doing, the district court failed to draw all reasonable inferences in Palin's favor and avoid drawing inferences in the defendants' favor….

The Second Circuit also concluded that Palin didn't have to prove "defamatory malice," "i.e., that Bennet intended or recklessly disregarded that ordinary readers would understand his words to have the defamatory meaning alleged by Palin." (This is different from the normal "actual malice" requirement, which merely requires proof that the defendant recklessly disregarded the possibility that the statements were false, or knew that they were false.)

Finally, the Second Circuit concluded that the jury verdict had to be reversed because of "the jurors' exposure during deliberations to push notifications announcing that the district court found for the defendants in deciding the Rule 50 motion":

[The district court erred in concluding] that the jury's verdict was not prejudiced because the jurors assured his law clerk that the push notifications "had not … played any role whatever in their deliberations."

It is well-settled that "an analysis of prejudice cannot be based on the subjective reports of the actual jurors." And, after applying the required objective test, we have no difficulty concluding that an average jury's verdict would be affected if several jurors knew that the judge had already ruled for one of the parties on the very claims the jurors were charged with deciding….

Shane B. Vogt and Kenneth G. Turkel (Turkel Cuva Barrios, P.A.) and Michael Munoz and S. Preston Ricardo (Golenbock Eiseman Assor Bell & Peskoe LLP) represent Palin.

The post Sarah Palin Gets New Trial in Libel Lawsuit Against N.Y. Times appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Kopel] The History of Bans on Types of Arms Before 1900

[Restrictions on carry, minors, and misuse were the norm -- not bans]

Controversial arms are nothing new in the United States. During the 19th century, there were widespread concerns about criminal use of arms such a Bowie knives, slungshots, blackjacks, and brass knuckles. The full history of state, territorial, and colonial laws about controversial arms is detailed in my recent article for Notre Dame's Journal of Legislation, The History of Bans on Types of Arms Before 1900, coauthored with Joseph Greenlee.

Because the article is thorough, it is enormous: 163 pages of text, and 1,563 footnotes. The student staff for volume 50 of the Journal of Legislation was spectacular. Not every law journal has staff who could handle such a megillah, let alone a staff that whose meticulous cite-check would improve the article.

The mainstream American approach to controls of the above arms were: 1. bans on concealed carry; 2. limits on sales to minors, such as requiring parental permission; and 3. extra penalties for misuse in a crime. Sales bans were the minority approach, and possession bans very rare.

From 1607 through 1899, sales bans for nonfirearm arms were:

Bowie knife. Sales bans in Georgia, Tennessee, and later in Arkansas. Georgia ban held to violate the Second Amendment. Nunn v. State, 1 Ga. 243 (1846). Prohibitive transfer or occupational vendor taxes in Alabama and Florida, which were repealed. Personal property taxes at levels high enough to discourage possession by poor people in Mississippi, Alabama, and North Carolina. Dirk (a type of fighting knife). Georgia (1837) (held to violate Second Amendment); Arkansas (1881). Sword cane (a sword concealed in a walking stick). Georgia (1837), held to violate the Second Amendment. Arkansas (1881). Slungshot or "colt" (most typically, a lead weight held in the tip of a flexible bludgeon). Sales bans in nine states or territories. The Kentucky ban was later repealed. Illinois also banned possession. Sand club or blackjack. New York (1881), (1884), (1889), (1899). Billy. New York (1881), (1884), (1889), (1899). Metallic knuckles. Sales bans in eight states, later repealed in Kentucky. Illinois also banned possession. Cannons. No bans. Restrictions on discharge without permission in a variety of municipalities.American bans on possession or sale to adults of particular types of firearms were:

Georgia (1837), all handguns except horse pistols. Held unconstitutional in Nunn v. State, 1 Ga. 243 (1846). Tennessee (1879) and Arkansas (1881). Bans on sales of concealable handguns. Based on militia-centric interpretations of the state constitutions, the laws did not ban the largest and most powerful revolvers, namely those like the Army or Navy models. Florida (1893). Discretionary licensing and an exorbitant licensing fee for carry of repeating rifles. Extended to handguns in 1901. The law was "never intended to be applied to the white population" and "conceded to be in contravention of the Constitution and non-enforceable if contested." Watson v. Stone, 148 Fla. 516 (1941) (Buford, J., concurring).Earlier this month, the en banc Fourth Circuit, by a 10-5 vote, upheld Maryland's ban on common rifles dubbed "assault weapons." Judge Wilkinson's majority opinion cited the article 16 times, and Judge Richardson's dissent cited it 9 times. Bianchi v. Brown, 2024 WL 3666180 (4th Cir. 2024) (en banc).

The article has also been cited in three U.S. District Court opinions supporting the claims of Second Amendment plaintiffs. Association of New Jersey Rifle & Pistol Clubs, Inc. v. Platkin, 2024 WL 3585580 (D.N.J. July 30, 2024); Miller v. Bonta, 699 F.Supp.3d 956, 981 n.86, 987 n.107 (S.D. Cal. 2023); Duncan v. Bonta, 695 F.Supp.3d 1206, 1242 n.177 (S.D. Cal. 2023). And in a Third Circuit dissent disagreeing with Second Amendment claims. Lara v. Commissioner Pennsylvania State Police, 91 F.4th 122, 144-45, 147 (3d Cir. 2024) (Restrepo, J., dissenting).

As the cites indicate, judges can disagree about how strictly or broadly to draw historical analogies, and about what sorts of laws create an established tradition at a given level of generality. It is at least helpful, I hope, that judges can have access to a common set of facts about the historical regulation of controversial arms.

The post The History of Bans on Types of Arms Before 1900 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 28, 1958

8/28/1958: Cooper v. Aaron is argued.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: August 28, 1958 appeared first on Reason.com.

August 27, 2024

[Jonathan H. Adler] Eighth Circuit Rejects Missouri's Second Amendment Preservation Act

[States cannot invalidate or refuse to recognize federal law. ]

Yesterday, a unanimous panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit rejected Missouri's attempt to nullify federal gun laws with which the state disagrees. Chief Judge Colloton wrote a remarkably brief opinion for the panel in U.S. v. Missouri, joined by Judges Loken and Kelly.

Here is the opinion's introduction:

Missouri's Second Amendment Preservation Act classifies various federal laws regulating firearms as "infringements on the people's right to keep and bear arms, as guaranteed by Amendment II of the Constitution of the United States and Article I, Section 23 of the Constitution of Missouri." The Act declares that these federal laws are "invalid to this state," "shall not be recognized by this state," and "shall be specifically rejected by this state."

The United States sued the State of Missouri, the governor, and the attorney general, alleging that the Act violates the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution of the United States. The district court denied Missouri's motions to dismiss for lack of standing and failure to state a claim, granted the motion of the United States for summary judgment, and enjoined implementation and enforcement of the Act. On this appeal by the State, we agree that the United States has standing to sue. Because the Act purports to invalidate federal law in violation of the Supremacy Clause, we affirm the judgment.

After concluding that the federal government has standing to sue to challenge the Missouri statute, Chief Judge Colloton addressed the merits.

The Supremacy Clause states that federal law is "the supreme Law of the Land, . . . any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding." U.S. Const. art. VI, cl. 2. "By this declaration, the states are prohibited from passing any acts which shall be repugnant to a law of the United States." McCulloch v. Maryland, 7 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 361 (1819). The "Second Amendment Preservation Act" states that certain federal laws are "invalid to this state," Mo. Rev. Stat. § 1.430, but a State cannot invalidate federal law to itself. Missouri does not seriously contest these bedrock principles of our constitutional structure. The State instead advances two arguments.

First, the State argues that the United States cannot sue to enforce the Supremacy Clause because it lacks a cause of action. While there is no implied right of action under the Supremacy Clause, there is an equitable tradition of suits to enjoin unconstitutional actions by state actors. Armstrong v. Exceptional Child Ctr., Inc., 575 U.S. 320, 326-27 (2015). Based on that equitable tradition, the United States has sued in other cases to enjoin a state law's implementation and enforcement or for other appropriate relief. See, e.g., United States v. Washington, 596 U.S. 832, 837 (2022); United States v. Minnesota, 270 U.S. 181, 194 (1926); Sanitary Dist. of Chi. v. United States, 266 U.S. 405, 425-26 (1925). We see no reason why the United States cannot proceed similarly in this case.

Second, Missouri contends that the Act is constitutional because the State may constitutionally withdraw the authority of state officers to enforce federal law. The State argues that the reason why it withdrew its authority—i.e., because the State declared federal law invalid—is immaterial.

That Missouri may lawfully withhold its assistance from federal law enforcement, however, does not mean that the State may do so by purporting to invalidate federal law. In this context, as in others, the Constitution "is concerned with means as well as ends." Horne v. Dep't of Agric., 576 U.S. 350, 362 (2015). Missouri has the power to withhold state assistance, "but the means it uses to achieve its ends must be 'consist[ent] with the letter and spirit of the constitution.'" Id. (quoting McCulloch, 7 U.S. (4 Wheat.) at 421) (alteration in original). Missouri's assertion that federal laws regulating firearms are "invalid to this State" is inconsistent with both. If the State prefers as a matter of policy to discontinue assistance with the enforcement of valid federal firearms laws, then it may do so by other means that are lawful, and assume political accountability for that decision.

The post Eighth Circuit Rejects Missouri's Second Amendment Preservation Act appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Participating in Black Lives Matter Protest Isn't Protected by Federal Labor Law

Federal labor law limits employers' ability to fire employees for "engag[ing] in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection." (It also limits unions' ability to discipline members for their speech on union matters.) But, unlike the laws in some states, it doesn't protect employees' broader political activities. The question then arises: What kinds of concerted activities are for purposes of employees' "mutual aid or protection"?

In NLRB v. SFR, Inc., the National Labor Relations Board (Members Kaplan, Prouty & Wilcox) affirmed Administrate Law Judge Arthur Amchan's decision that participating in Black Lives Matter protests wasn't sufficiently focused on employee rights:

Specifically, we agree with the judge that the employees' participation in Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests was not shown to be for mutual aid or protection in the context of the facts here and under extant law; therefore, we dismiss the allegations.

{Although Member Wilcox agrees that the evidence here does not establish that the employees' participation in outside BLM protests was for ""other mutual aid or protection" under Sec. 7 as defined in Eastex, Inc. v. NLRB (1978), she observes that the judge's articulation of the relevant standard was unduly narrow. Instead, as the Board explained in Home Depot USA, Inc. (NLRB 2024), "an employee's concerted actions are protected by Sec. 7 of the Act so long as an objective is protected. The fact that the employee's actions may have other objectives, or even that those objectives may predominate, is immaterial."}

And here's an excerpt from the decision that was affirmed (read the full document for more factual details):

Nichols and King engaged in concerted activity by attending a BLM protest together…. However, in the circumstances of the instant case, none of the alleged discriminatees engaged in activity protected by Section 7 of the Act. The lead case on this issue is Eastex, Inc. v. NLRB (1978). In that case, the Supreme Court held or reaffirmed the proposition that Section 7 protects employees when they engage in otherwise protected concerted activities in support of employees of employers other than their own. The Court also made it clear that Section 7 protection may cover appeals to persons or entities that are not being solicited for support in their capacity as an employer, such as an appeal to a state legislature opposing "Right To Work" legislation, and an appeal to voters to elect representatives favorable to the employees' concerns.

However, Justice Powell, in the majority opinion also wrote, "It is true, of course, that some concerted activity bears a less immediate relationship to employees' interests as employees than other such activity. We may assume that at some point the relationship becomes so attenuated that an activity cannot fairly be deemed to come within the "mutual aid or protection" clause."

BLM was at least originally a protest movement against police misconduct of African Americans. It may well have morphed into a protest movement against all forms of racial injustice, including in the workplace. Nevertheless, that is not BLM's primary focus. At the BLM protest attended by Taylor, not a word was said about racial discrimination in the workplace. The protest appears to have been focused entirely on mistreatment of African Americans by the police and specifically the George Floyd murder.

There is no connection between the BLM protests in this case and any concerns about racial injustice at Parkside Cafe or any other particular employer. In this record, there is no evidence that the BLM protests focused on any specific workplace issue festering in workplaces generally, e.g. racial discrimination in hiring. To find that the Act protects activity which by no stretch of the imagination can be related to the workplace, is to expand the scope of the Act far beyond that to which it has ever been applied before. Moreover, I doubt it was intended to reach such activity.

The consequences of such an expansion of the scope of the Act would logically forbid employers for prohibiting all sorts of divisive activity from their workplaces, which are at best tangentially related to the concerns of employees as employees.

I find that the attendance of Taylor, King and Nichols at BLM rallies, at least in the circumstances established in this record, is so attenuated to the interests of the alleged discriminatees as employees to fall outside of the "mutual aid or protection clause. Thus, even if they were constructively discharged, Respondent did not violate the Act by doing so….

The Administrative Law Judge also held that the employees weren't "constructively discharged" (i.e., pressured into quitting because work conditions had become intolerable) or told that they couldn't remain employed if they supported Black Lives Matter:

While Dykes expressed his displeasure towards BLM and his employees' participation, he made no demand or suggestion that they could no longer work at Parkside if they continued to attend BLM protests…. Bagwell, who normally set employee work schedules and supervised them, never conditioned continued employment on ceasing support for Black Lives Matter. In fact, in the three-way text exchanges between Bagwell, Dykes and Taylor, Bagwell wrote that he was not firing anybody. Given this situation, which was ambiguous at best, I find that the discriminatees were not given a clear and unequivocal choice between continued employment and continued support for Black Lives Matter….

The post Participating in Black Lives Matter Protest Isn't Protected by Federal Labor Law appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Accused Plaintiff of Calling Her the 'F-Word'"

In Winfree v. Warren County School Dist., decided last month by Judge Travis McDonough (E.D. Tenn.), plaintiff was a girls' high school basketball player, who "had been offered a full scholarship to play basketball at Trevecca Nazarene University":

On November 15, 2023, Defendant Mendy Stotts, the women's basketball coach, pulled Plaintiff out of practice to speak with her in the hallway. Stotts "yell[ed]" at Plaintiff, "saying she was tired of [Plaintiff's] disrespect towards her" and accused Plaintiff of calling her the "f-word" during practice. Stotts told Plaintiff that "[Stotts] no longer wanted her as part of the basketball team." That same night, Plaintiff emailed Phillip King, one of the school's athletic directors, to request a meeting.

The next day, on November 16, 2023, Plaintiff and her mother met with King and Assistant Principal Anna Geesling to discuss the incident. Plaintiff's mother explained that she had never heard about any disciplinary proceedings prior to Plaintiff being kicked off the team. Another meeting was held the next day, this time with King, Principal Chris Hobbs, Stotts, Plaintiff, her parents, her grandparents, and a family friend.

At the meeting, Stotts said she had evidence that Plaintiff said "the f-word," while Plaintiff stated that there were witnesses who would testify that she did not say the "f-word." Plaintiff was not allowed to present those witnesses. At the end of meeting, Stotts dismissed Plaintiff from the basketball team. Hobbs upheld Stotts's decision. Two weeks after Plaintiff was dismissed from the team, Trevecca Nazarene rescinded her scholarship offer. Plaintiff alleges she also "had anticipated" scholarship offers from Middle Tennessee State University and Tennessee Tech University, but these offers never came….

Plaintiff alleges that Defendants violated her due process rights by dismissing her from the team without a hearing and defamed her by falsely stating that she had said "the f-word." …

Plaintiff argues that students have a property interest in playing on a school sports team "when they are faced with suspension or removal from their respective teams, and that removal results in the student-athlete losing one or more athletic scholarships to colleges or universities."

[But] the Sixth Circuit has repeatedly held that "[a student] has neither a liberty nor a property interest in interscholastic athletics subject to due process protection." … Furthermore, courts have held that the due process analysis is no different when a student has an athletic scholarship. Courts that have assumed that a scholarship could constitute a property interest have noted that the mere offer of a scholarship is not enough.

{The Second Circuit recently recognized a student's property interest in a one-year athletic scholarship that the student had already accepted. However, the court limited its holding to scholarships that were "for a fixed period and terminable only for cause," reasoning that a student could "reasonably expect[] to retain the scholarship's benefits for that set period." Here, Plaintiff only had "a [] scholarship offer" from one school and "anticipated [] scholarship offer[s]" from two more….}

Plaintiff points to a handful of non-binding cases where courts have found a property interest in participation in school sports. This is hardly a deep bench of cases, and, regardless, Plaintiff's argument runs afoul of binding precedent. While the Court recognizes the practical impact that a scholarship offer often has on the ability of a student to obtain a higher education, it does not have the discretion to ignore the weight of binding precedent….

Plaintiff also brings a state-law defamation claim, arguing that Defendants defamed her by falsely alleging that she said the "f-word." {Plaintiff never actually explains what "the f-word" is, or even the context in which it was allegedly used. Such details are important when they form the basis of a defamation claim. There are certainly contexts in which the use of "the f-word" would be more offensive than others.}

"[A] federal court that has dismissed a plaintiff's federal-law claims should not ordinarily reach the plaintiff's state-law claims." … The Court finds that the interests of judicial economy and abstaining from needlessly deciding state-law issues weigh in favor of declining to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the remaining state-law defamation claim….

For other examples where expurgation led to confusion, see n.73 (pp. 19-20) of Randy Kennedy's and my The New Taboo: Quoting Epithets in the Classroom and Beyond.

The post "Accused Plaintiff of Calling Her the 'F-Word'" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Plaintiff Who Sued Over Alleged Discrimination at the Public Radio Marketplace Show Allowed Retroactive Pseudonymity

Many plaintiffs—especially plaintiffs suing their employers—worry that, if their lawsuit becomes publicly visible, future employers will be reluctant to hire them. Few people want to be viewed as a litigious employee. Nonetheless, courts generally reject claims of pseudonymity that are based on such concerns about reputational or economic harm, see pp. 1457-60 of The Law of Pseudonymous Litigation.

But courts aren't entirely consistent on virtually anything related to pseudonymous litigation, and the same is true here. I've seen a few cases that allow pseudonymization, including retroactive pseudonymization, and even retroactive sealing at the behest of such plaintiffs. Here's one in which the court offered at least some degree of explanation, from the L.A. Superior Court.

In 2023, plaintiff had sued Minnesota Public Radio, American Public Media, Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal, and former Marketplace general manager Deborah Clark, alleging that

she [had] engaged in legally protected activities including but not limited to reporting and opposing employment and hiring practices she reasonably believed were discriminatory including but not limited to discrimination based on an individual's gender

and as a result was harassed and ultimately fired from Marketplace (in 2019). As best I can tell, the court filings offered few details on exactly what plaintiff did, though they "noted that Plaintiff was a female employee who opposed the unfair treatment against male employees by Defendants."

The case apparently drew no public attention; and, a bit under a year later, the parties settled, so the case is now in the process of being dismissed. For whatever it's worth, note that the plaintiff is now an editor in charge of certain kinds of investigations at a major American newspaper (and appears to have held that position when the lawsuit was filed).

After the notice of settlement, plaintiff asked the court to seal the record, or at least "to replace her name with a pseudonym." (The defendants didn't oppose the motion.) Judge Theresa Traber rejected the sealing request, on the grounds that it wasn't "narrowly tailored," precisely because the "proposed alternative … of proceeding under a pseudonym plainly demonstrates that a less-restrictive means exists to achieve the interest asserted by Plaintiff." And Judge Traber conditionally granted the request for pseudonymity; here's an excerpt from her Tentative Ruling last month (in the case that is now called Doe 1 v. Minnesota Public Radio);

In 2022, the Court of Appeal held that the overriding interest test, described in NBC Subsidiary (KNBC-TV) Inc. v. Superior Court (Cal. 1999) with respect to sealing the record and codified in the Rules of Court discussed above, is equally applicable to a request for anonymity.

Here, there has been a failure of proof because Plaintiff has not presented admissible evidence from an individual with personal knowledge of the risk to Plaintiff arising from the case proceeding under her own name. Had such evidence been provided, the Court would be inclined to find that the risk of Plaintiff suffering irreparable damage to her career prospects and reputation overcomes the right of public access to the records bearing Plaintiff's true name.

The Court also finds that the proposed relief is narrowly tailored: while proceeding under a pseudonym would require refiling of all documents bearing Plaintiff's name to replace that name with a pseudonym and sealing of the original documents, the practical effect of that relief would maintain the right of public access to the substance of the records. Finally, the Court finds that there is no less restrictive means of achieving the overriding interest, as the only other remedy would be to seal the records outright, as discussed above.

In acknowledgement of the stipulation by the parties to sealing of the record or proceeding under a pseudonym and the defects in the motion arising from a failure of proof, the Court will grant the alternative motion to proceed under a pseudonym conditioned on a supplemental declaration from Plaintiff setting forth the matters that are uniquely within her personal knowledge….

Such a supplemental declaration was indeed filed:

[3.] I respectfully request the use of a pseudonym for all public documents within this matter against American Public Media to protect me from the harm of potential retaliation by current or future employers should they learn about this case.

[4.] The media industry is small and very connected. Further, the options for employment in Los Angeles are particularly scarce as many of the most highly coveted employers are either in the process of or completed layoffs this year.

[5.] Due to the extreme scarcity of employment opportunities, even the slightest hint of a "problem" in my industry is a black mark that makes it almost impossible to overcome. In the media industry, people know each other and have ties across companies. Further, I have had to agree to background checks as a condition of employment.

[6.] Though employers are not supposed to take the filing of lawsuits against former employers against individuals when considering employment, I believe that within my industry they unquestionably do.

[7.] Based on my more than 30 years of experience within the media industry, I believe it would be frowned upon and hurt my prospects to gain future employment within my profession if prospective employers were to find out I filed a lawsuit against a former employer.

[8.] In addition, the stress associated with knowing that any employer, colleagues, or other journalist could find this case and make determinations about me with no other information would be harmful to me.

[9.] It would haunt me and cause huge stress in any possible future conversations about Marketplace including interviews with potential employers.

And the court did indeed retroactively pseudonymize the findings.

I'm generally skeptical that such pseudonymity is proper, in large part because it interferes with people's ability to report on cases in a serious way; as I noted in , the names of the parties are often key to investigating the case further, for instance to answer:

Is the case part of a broad pattern of litigation by, say, an ideological advocate, a local businessperson or professional with an economic interest in the cases, or a vexatious litigant? Is there evidence that the litigant is untrustworthy, perhaps in past cases, or in past news reports? Does the litigant have a possible ulterior motive—whether personal or political—that isn't visible from the court papers? Was the incident that led to the lawsuit covered or investigated in some other context? Is there online chatter from possibly knowledgeable people about the underlying incident? Is there some reason to think that the judge might be biased in favor of or against the litigant?Knowing the parties' names can help a reporter or an interested local activist quickly answer those questions, whether by an online search or by asking around—the parties themselves might be willing to talk; but even if they aren't, others who know them might answer questions, or might voluntarily come forward if the party is identified.

And litigation of course deploys the coercive power of the state, even as it also accomplishes private goals. A libel lawsuit, even between two private parties, is aimed at penalizing (and sometimes enjoining) supposedly constitutionally unprotected speech. An employment lawsuit is aimed at implementing a set of legal rules that constrain employers, protect employees, and affect the interests of the public in various ways, direct or indirect. In the words of Justice Holmes, writing about the fair report privilege,

It is desirable that the trial of causes should take place under the public eye, not because the controversies of one citizen with another are of public concern, but because it is of the highest moment that those who administer justice should always act under the sense of public responsibility, and that every citizen should be able to satisfy himself with his own eyes as to the mode in which a public duty is performed.

Courts have recognized that this rationale applies also to the openness of court records, including to the presumption against pseudonymity. And evaluating the credibility of the parties, whether as to their in-court statements or as to their court filings, will often require knowing their identities.

On the other hand, as I noted in my article, in most cases where denying pseudonymity can harm parties (whether through harming privacy or reputation or otherwise), denying pseudonymity can also undermine the public policy that the civil causes of action are aimed to serve. Plaintiffs faced with the prospect of these harms might choose not to litigate. They might decline to sue or might decline to continue with their lawsuits once pseudonymity is denied.

Likewise, defendants might settle before complaints are filed, even if they have sound legal or factual defenses. The underlying causes of action (or defenses) may end up being underenforced, and useful precedent may end up being underproduced.

In any event, I thought this case was noteworthy because it illustrates that sometimes, even if not usually, courts do allow pseudonymity to protect plaintiffs' reputational and economic interest. (I should also note that the reason I'm not mentioning plaintiff's name or the name of the plaintiff's employer is that it's no longer part of the case title, and I see no reason to publicize the name any more than necessary. On the other hand, there is no legal restriction on me that would compel me to omit the name; and the decision itself strikes me as important and interesting, so I don't feel any ethical obligation to avoid posts that might be used to determine the plaintiff's identity.)

The post Plaintiff Who Sued Over Alleged Discrimination at the Public Radio Marketplace Show Allowed Retroactive Pseudonymity appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 27, 1948

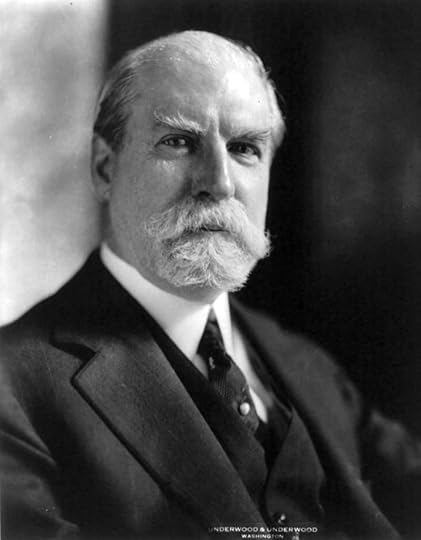

8/27/1948: Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes dies.

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes

Chief Justice Charles Evans HughesThe post Today in Supreme Court History: August 27, 1948 appeared first on Reason.com.

August 26, 2024

[Jonathan H. Adler] Did Supreme Court Violate the Purcell Principle in Arizona Voting Case?

[Rick Hasen and Derek Muller offer competing takes on the RNC v. Mi Familia Vota order.]

Last week, in RNC v. Mi Familia Vota, the Supreme Court granted a partial stay of a district court order enjoining portions of Arizona's election laws that require proof of citizenship for voter registration. The question splintered the justices. Justices Thomas, Alito and Gorsuch would have stayed the district court order (allowing the Arizona law to take effect) in full, while all four female justices (Kagan, Sotomayor, Barrett and Jackson) would have denied the stay request across-the-board. Thus the Chief Justice and/or Justice Kavanaugh made the difference (possibly "or" because only one of them needs to have voted with the female justices to deny part of the stay request).

Over at the Election Law Blog, there is a little debate over whether this order violates the "Purcell Principle," which seeks to prevent meaningful changes to election laws or election administration in the run up to election day.

Rick Hasen thinks the order violates the principle, because it alters and complicates the rules governing voter registration. Although he's not a fan of Purcell, he thinks the Supreme Court should be criticized for not applying it consistently. He writes:

beginning today, people who try to register to vote using the state form who do not provide documentary proof of citizenship while registering to vote will not be allowed to register at all. This is a change from the past when they could vote at least in federal races. It's going to create administrative confusion and voter disenfranchisement in the period before the election. Although the plaintiffs in the case raised the Purcell issue repeatedly, the Supreme Court ignored it here. . . .

The instructions on the state form are incorrect, there's not going to be enough time to get the word out to voters, and procedures have to change with the election just weeks away. How a court that is committed to Purcell could allow this to happen is inexplicable.

Derek Muller takes a different view. According to Muller, Purcell is not about whether the Supreme Court should stay its hand in the period just before an election, but whether the federal judiciary should. He writes:

I think the opening description of Purcell, one that "discourages court orders in the period before the election on grounds that it can cause election administrator difficulties and voter confusion," isn't necessarily the right framing. I think Purcell is about court orders that change the legal status quo, not simply any change.

Consider three of the major Court decisions here:

Purcell: The Arizona legislature enacted a statute on voter identification; the Court discourages a court from issuing an order changing the status of that statute too close to an election.

RNC v. DNC (2020): The Wisconsin legislature enacted a statute on the date of holding an election; the Court discourages a court from issuing an order changing the status of that statute too close to an election.

Merrill v. Milligan (2022): The Alabama legislature enacted a statute setting boundaries in legislative election; the Court discourages a court from issuing an order changing the status of that statute too close to an election.

RNC v. Mi Familia Vota fits this pattern exactly. The Arizona legislature enacted a statute in 2022 about proof of citizenship; the Court discourages a court from issuing an order changing the status of that statute too close to an election.

So in this posture, here's the typical issue: there is a law on the books (new or longstanding) that a plaintiff tries to enjoin from operation. The plaintiff is likely to succeed on the merits, but the defendant argues the timing precludes the injunction. . . .

if the Court is serious about Purcell, . . . the majority has it right. The problem is a district court's decision to enjoin operation of a statute close in time to an election. If we are close to an election, the court should not enjoin the operation of a statute under Purcell. There may be other equitable considerations at stake, and there may be concerns about election administration, but those are distinct issues.

Professors Hasen and Muller are both more expert on this question than I am, but Professor Muller's account is more consistent with the way that I have understood Purcell. As I see it, if the principle is to apply to lower courts, then the Supreme Court has no choice but to intervene no-less-close to an election than the offending lower court if the principle is to mean anything at all. To which I suspect Professor Hasen would reply: Perhaps that is a reason not to have this principle in the first place. I take the point, but would question whether abandoning Purcell altogether would make it too easy to game election rules with strategic litigation.

The post Did Supreme Court Violate the Purcell Principle in Arizona Voting Case? appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers