Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 275

August 30, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Title IX's Exemption for Religious Institutions as to Sex, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity Is Constitutionally Permissible

[The court concludes that the government may institute such an exemption, though doesn't decide whether it must do so.]

So holds today's Ninth Circuit opinion in Hunter v. U.S. Dep't of Ed., decided by Judge Milan Smith, joined by Judges Mark Bennett and Anthony Johnstone:

Title IX, a landmark law prohibiting gender discrimination at federally funded educational institutions, carves out an exception for religious institutions whose tenets mandate gender-based discrimination. Plaintiffs are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or nonbinary (LGBTQ+) students who applied to or attended religious institutions and alleged that they experienced discrimination on the basis of their sexuality or gender identity.

They brought suit against the Department of Education (Department), claiming that Title IX's religious exemption violates the equal protection guarantee of the Fifth Amendment and establishes a religion in violation of the First Amendment. They also challenge the Department's implementing regulations of Title IX as arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)….

This case addresses, among other issues, the question of whether Congress's attempt to balance the important interests of religious freedom and gender-based equality violated the Constitution. Because we hold that Congress did not exceed its constitutional boundaries, we affirm….

Title IX prohibits certain educational institutions from receiving federal funding if they exclude, deny benefits to, or subject to discrimination any person "on the basis of sex." We have recently interpreted this provision to prevent federally funded educational institutions from discriminating against gay or transgender students. See also Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) ("[I]t is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex" in the context of Title VII.). Title IX does not prohibit discrimination, however, when an educational institution "is controlled by a religious organization if the application of [Title IX] would not be consistent with the religious tenets of such organization." …

The court held that the exemption doesn't violate the Establishment Clause:

To determine whether government action violates the Establishment Clause, the panel must "focus[ ] on original meaning and history." Any practice that was "accepted by the Framers and has withstood the critical scrutiny of time and political change" does not violate the Establishment Clause. … Because no identical exemption existed at the Founding, we must use the historical analogues that are available….

Given the dearth of historical equivalents, … tax exemptions are the most analogous case to Title IX's statutory exemption…. [T]ax exemptions for religious institutions are really "[s]ubsid[ies] of buildings of worship," which is "a universal practice of state and federal government." Just as a school is not required to accept federal funding, a religious institution is not required to own property. Even so, religious institutions are constitutionally exempted from paying property taxes.

Both the statutory exemption to Title IX and property tax exemptions operate as a financial benefit to non-secular entities that similarly situated secular entities do not receive. And they were deemed constitutional without a requirement that the exemption only apply if the tax conflicted with a specific tenet of the religion. Even if Title IX's exemption is a "benefit" instead of a "burden," "[a] variety of benefits have been bestowed by government on religious practices and either have been unchallenged or passed constitutional muster without fatal compromise of principle." Absent additional historical evidence—and Plaintiffs point us to none here—the history of tax exemptions near the time of the Founding suggests that the statutory exemptions that operate as a subsidy to religious institutions do not violate the Establishment Clause according to its original meaning.

Having considered the history of religious exemptions at or near the Founding, the history and tradition test requires us to look next to the "uninterrupted practice" of a law in our nation's traditions. The Department identifies a relevant tradition in "modern legislative efforts to accommodate religious practice." [Examples omitted. -EV] … [These efforts] evince a continuous, century-long practice of governmental accommodations for religion that the Supreme Court and our court have repeatedly accepted as consistent with the Establishment Clause. The examples provided by the Department demonstrate that religious exemptions have "withstood the critical scrutiny of time and political change." And given that this exact law did not exist at the Founding, that more recent (albeit, still lengthy) tradition is of greater salience.

Plaintiffs make several arguments that, despite the long tradition of statutory religious accommodations, the Title IX exemption still violates the Establishment Clause. First, Plaintiffs argue that the exemption prefers religion to irreligion, impermissibly "singling out religious institutions for special benefits." We disagree. In Amos, the Supreme Court held that Title VII's similar exemption for religious institutions from religious non-discrimination in employment, even when the job function is secular, does not violate the Establishment Clause. While Amos was decided under Lemon and does not reference historical practices or understandings, it does make the logical point that no religious accommodation could stand if we held that this type of accommodation prefers religion over irreligion. Given that the government "sometimes must" accommodate religion, the exemption does not prefer religion to irreligion for simply carving religious behavior out of the statute….

Second, Plaintiffs argue that the exemption "discriminates between religious sects and is available only to some religious groups—those whose tenets are inconsistent with an application of Title IX." This argument fails. The statute facially applies to any religious organization for which the religious tenets would not be consistent with the application of Title IX. And there is no evidence in the record that the exemption here "was drafted with the explicit intention of including particular religious denominations and excluding others." Under Plaintiffs' view, the only constitutional alternative would be to exempt any religious institution from the statute without regard to its tenets—a less narrowly tailored law. The Constitution does not require such a result.

Third, Plaintiffs contend that the exemption impermissibly "conscripts federal employees as ecclesiastical inquisitors, charged with ascertaining the 'religious tenets' of each school and determining whether a particular application of Title IX is consistent with the teachings of that denomination."

The Department must "accept the ecclesiastical decisions of church tribunals as it finds them." It clearly does so. Here, when a school claims an exemption, the Department must make two determinations—whether the school is controlled by a religious organization and whether Title IX would conflict with the religious tenets of the controlling organization. The Department has, as pleaded in the FAC, "never rejected an educational institution's assertion that it is controlled by a religious organization" and "never denied a religious exemption when a religious educational institution asserts a religious objection."

We are not persuaded that this type of facially neutral religious accommodation violates the Establishment Clause.

And the court held that the exemption didn't violate equal protection principles:

Plaintiffs contend that the Title IX exemption violates [the Fifth Amendment's] equal protection guarantee because it "targets Americans for disfavored treatment based on their sex, including targeting based on sexual orientation and gender identity." They claim that the exemption is facially discriminatory, motivated by discriminatory animus, and unconstitutional as applied to Plaintiffs. Specifically, they argue that we should apply intermediate scrutiny and hold that the exemption does not meet that high standard. Defendants, on the other hand, argue that we should apply rational basis review, which they contend the exemption easily withstands.

Because the exemption would survive the more demanding intermediate scrutiny standard, we need not decide which standard applies. A statute passes intermediate scrutiny when it "serve[s] important governmental objectives" and is "substantially related to achievement of those objectives." The exemption seeks to accommodate religious educational institutions' free exercise of religion. The free exercise of religion is "undoubtedly, fundamentally important."

The exemption substantially relates to the achievement of limiting government interference with the free exercise of religion. As the Department states, the "statutory limitations on its application ensure a substantial fit between [ends and] means." It only exempts educational institutions (a) controlled by religious institutions and (b) only to the extent that a particular application of Title IX would not be consistent with a specific tenet of the controlling religious organization. The exemption does not give a free pass to discriminate on the basis of sex to every institution; it contains limits that ensure that Title IX is not enforced only where it would create a direct conflict with a religious institution's exercise of religion. Thus, the exemption substantially relates to a "fundamentally important" governmental interest.

{We decline to address the Religious Schools' argument that the exemption is required by the First Amendment's Free Exercise clause.}

The court also rejected plaintiffs' claims under the Administrative Procedure Act related to the Department's rules implementing the exemption; for more, read the whole opinion.

Ashley C. Honold argued the case for the Justice Department, Christopher P. Schandevel (Alliance Defending Freedom) for intervenor educational institutions, and Gene C. Schaerr (Schaerr Jaffe LLP) for intervenor Council for Christian Colleges & Universities. Note that I'm a part-part-part-time academic affiliate for the Schaerr Jaffe firm, but I wasn't involved in this case (and indeed just learned of the firm's participation in it when reading the opinion). They were joined on the briefs by too many other lawyers for me to list.

The post Title IX's Exemption for Religious Institutions as to Sex, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity Is Constitutionally Permissible appeared first on Reason.com.

[John Ross] Short Circuit: A Roundup of Recent Federal Court Decisions

[A tardy oath, old-timey drunkards, and telling it man to [redacted] man.]

New on the Bound By Oath podcast: Civil forfeiture is a civil rights nightmare. On this episode, we dig into the birth of the modern forfeiture regime (which we put at 1984, give or take), and we dig into forfeiture's historic roots (1789). And we ask what forfeiture's historic pedigree means for its constitutionality today. (It's still unconstitutional.)

And check out recent episodes of the Short Circuit podcast, some of which are now on YouTube. Proving that our host and guests are (or at least resemble) real people.

The Postal Regulatory Commission is tasked with ensuring that USPS competes fairly in its non-monopoly package-delivery market. UPS contends that it has not done so with peak-season costs, allowing USPS to subsidize December costs with its first-class mail market, in which it has a monopoly. D.C. Circuit: Don't be a Scrooge, UPS. The rates are fine. Remember how during the Sarah Palin v. New York Times trial the judge threw the case out in the middle of the jury's deliberations, let the jury give its 2 cents anyway because he hadn't told them about his ruling, but some of them saw what he did anyway via "push notifications," and he was like whatever? Well, the Second Circuit says that wasn't exactly tip-top courtroom management. New trial granted. Look, if the government induces you to enter a plea bargain by promising to advocate for one sentencing range and then argues for a different, higher sentencing range, the government has breached the plea agreement, but you can't expect the Second Circuit to do anything about that if your lawyer only protested that this was unfair instead of saying the magic words "the government is breaching the plea agreement." In which the Third Circuit reminds us that the easiest way to remember the nuanced differences between the independent-source doctrine and the inevitable-discovery doctrine is the simple mnemonic "if you invoke the wrong one your client will go to prison for 240 months." This farcical, Coen-brothers-esque caper starts with a "fight-club-style altercation" among motorcycle gang members, proceeds to an alleged kidnapping, and escalates to an abortive robbery/murder attempt. It ends with one of the gang members convicted of the alleged kidnapping. Third Circuit: But his jury trial rights were violated. The convicted defendant argued there was no kidnapping (i.e., that the kidnappee was a willing participant in the robbery). His acquitted co-defendant argued that he was coerced into going along with the whole scheme. Both can't be true, so they required separate juries. In 1988 a 15-year-old immigrates to the U.S. and is adopted by U.S. citizen parents. At 17 he applies for citizenship. A few months later, after turning 18, the INS interviews him and—congratulations!—has him take the Oath of Allegiance and says he's a citizen. Except: Later they realize he's actually ineligible under the form they used because he's over 18. They don't tell him this for . . . 21 years. At which time he's in prison. He's later deported. He appeals on statutory grounds and also pleads equitable estoppel. Third Circuit: You might win if you had taken the oath before your 18th birthday. But you didn't. Plus, equity delights to do justice unless you're asking for citizenship. Allegation: In 1993 a woman skipped parole in Pennsylvania. In 2019 state authorities get around to issuing a warrant for her arrest. However, they use the address and photo of a different woman with the same name. The innocent woman is arrested and held for two weeks despite repeated pleas that she's innocent. She sues. Third Circuit: And loses. Too bad for her, but federal officials, not state, did the bad things and unless your name (and the woman who skipped parole, of course) is "Webster Bivens" you have no claim. Most Marylanders must obtain a license before purchasing a handgun, which requires that they submit fingerprints, be at least 21 years old, complete a safety course, and not be barred by law from having a gun. Fourth Circuit (en banc): Which is fine. Shall-issue licensing laws, like Maryland's, generally don't infringe the right to keep and bear arms. Concurrence: Laws regulating acquiring a handgun are encompassed by the Second Amendment's text but are nevertheless constitutional. Partial concurrence: Too much dicta. Dissent: The Supreme Court created a test, which the majority didn't apply and under which the law fails. In qualified-immunity news, the Fifth Circuit says that reasonable officials should probably have known that "declining to treat the broken screws in a prisoner's ankle and then sending him out to do manual labor in the fields while standing on that very ankle" was less than perfectly constitutional. Louisiana law prohibits automobile manufacturers from selling directly to consumers, and the commission that enforces the law is run by folks associated with auto dealerships. Chagrined by electric-car manufacturer Tesla's business model of selling direct to consumers, the commission opens an investigation. Tesla sues. Fifth Circuit: And the company's due process and antitrust claims should not have been dismissed. There is indeed something amiss about the way these market participants run things. Judge Jerry Smith is so displeased with the Fifth Circuit's ruling that the New Orleans Parish Sheriff's Office must abide by a 2013 consent decree and complete construction of housing for prisoners with mental health issues and medical needs that he dissents a la Ricky Bobby: "The result? An opinion with reasoning that, at every turn, is fatally compromised. Some parts are totally unhinged. And the remainder is incomprehensible. I respectfully dissent." Judge Smith seems happier to dissolve an older consent decree. 1992 a class of voters entered into a consent decree requiring remedial actions for elections to the Louisiana Supreme Court. In 2021, Louisiana moved to dissolve the decree, primarily on the ground that it had complied. The district court and a panel of Fifth Circuit judges decline to dissolve the decree. Fifth Circuit, en banc (written by Englehart, J., joined by, inter alia, Smith, J): Everyone agrees that Louisiana has fully complied with everything, so the consent decree is dissolved. Dissent: The consent decree imposed a "future compliance obligation" that the majority fails to reckon with. On the one hand, Texas man is charged with being an illegal alien in possession of a gun and ammo. He raises a Second Amendment defense. Fifth Circuit: We've already said that "illegal aliens are not 'law-abiding, responsible citizens'" and the Bruen case doesn't change that. Concurrence: They're not members of "the people" in the first place. On the other hand, police arrest an El Paso, Tex. man outside his home and begin speaking to his wife. She tells them she sometimes smokes pot for medical reasons. She is not high during their conversation. Yet, because she owns some guns she's prosecuted for being a "user" in possession. Fifth Circuit: When we analogize this lady to the Founding she's more like a drunkard than a lunatic so this law (as applied) cannot stand. It's not quite the Judean People's Front vs. The People's Front of Judeah, but if you want to learn the latest on what faction properly controls the Libertarian Party of Michigan (or at least can use the LP's trademarks) the Sixth Circuit will get you up to speed. In 1970, Congress created a grant program for family-planning projects. Since then, HHS has repeatedly flip-flopped between whether recipients may not or instead must provide counseling about and referrals for abortions. Today, HHS is in must-provide mode. After Dobbs, Tennessee largely banned abortion, and when it refused to comply with HHS's requirements, it lost its grant. Sixth Circuit: Which is OK because HHS's rules are permissible implementations of the statute. Partial Dissent: The statute says no funds "shall be used in programs where abortion is a method of family planning"—notwithstanding precedent that relied on the now-defunct Chevron doctrine. After Rahimi, the Sixth Circuit was obviously going to hold that the Second Amendment doesn't prevent disarmament of a felon convicted of robbery with a deadly weapon. But was it just going to say that felon-in-possession laws are presumptively lawful, or was it going to engage in a lengthy and nuanced historical analysis leaving open the possibility of as-applied challenges by people with less serious felony records? Sixth Circuit: A lengthy and nuanced historical analysis leaves open the possibility of as-applied challenges by people with less serious felony records. (A concurrence preferred the short version.) Malta, Ill. vocational high school teacher searches a student's bag and finds a suspected vaping product. When confronted, the student proffers "let me tell you something man to [expletive] man. How would you like it if I searched you?" Student then repeatedly tries to reach into the teacher's pants and physical contact ensues. Teacher is arrested and prosecuted for assault—and the judge directs a not guilty verdict after the prosecution rests. Can the teacher sue the officers who submitted the arrest warrants? Seventh Circuit: Arguable probable cause is all you need for qualified immunity. Missouri: Various federal gun-control laws "shall be specifically rejected by this state" and "shall be invalid to this state." Eighth Circuit: You see, it's the supremacy part of the Supremacy Clause that doesn't let you do that. You don't have to assist with enforcing federal laws you don't like, but that can't be premised on saying those laws don't exist in your state. In 1976, Congress welcomed the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) into the American political system. That same year, Congress banned animal fighting, but continued to allow it in states and territories—like the CNMI—where it was permitted by law. But in 2018, Congress banned it everywhere. A Northern Mariana Islander with a penchant for cockfighting challenges the amendment. Ninth Circuit: Nope, it's fine. The original law existed when CNMI entered our political system, and the Covenant between the U.S. and CNMI makes the amendments applicable as well. Idaho's Constitution requires the legislature to provide "free common schools." Idaho Parents: That means that all the fees I pay for my kid to take extra-curriculars are "takings" under the Fifth Amendment! Ninth Circuit: It does not mean that, no. (Also, here's some bonus guidance for district courts on the "law of the case" doctrine.) You might think this case is boring because it's just about whether police officers can sue a sitting city councilwoman for defamation after she claimed they murdered an innocent man while on duty, but the Ninth Circuit wisely publishes only the sexy part, which concerns whether the federal rule that says each party must pay for the deposition of opposing experts means that each party must pay for the deposition of opposing experts. Ninth Circuit: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act means the defendant cannot be held liable for the fact that its product was a cesspool of hateful cyberbullying, but it can maybe still be held liable for falsely promising people that its product was something other than a cesspool of hateful cyberbullying. If you're a litigant in Hawaii state court and are counting on the court system's practice of sealing all medical and health records then you probably should read this Ninth Circuit opinion that says it violates the First Amendment. Allegation: The Navy misled San Francisco officials when leasing a contaminated former shipyard riddled with radiation to the city, resulting in police officers working at the site being exposed to contaminants. Officers sue the United States, but the gov't asserts it has sovereign immunity because Congress has not waived immunity for tort claims "arising out of . . . misrepresentation [ or] deceit." Ninth Circuit: And that is broad enough to bar these claims, even if it was the city rather than the officers who relied on the misstatements about the contaminated site. Oregon attorneys must join the Oregon State Bar and pay dues that fund its activities. A member objects to some of the speech that OSB engages in, including lobbying and statements in its membership magazine. Ninth Circuit (2021): SCOTUS precedent forecloses a speech claim but a freedom of association claim can go forward. District court: And I see no unconstitutional associating. Ninth Circuit (2024): But we do. Couldn't the OSB include a disclaimer that not all members agree? And in en ban news the Eleventh Circuit will not reconsider its decision to not enjoin the enforcement of Alabama's ban on providing certain puberty blocker hormones to minors. One of the dissents opens with words that at IJ would be awarded the prize for understatement of the year: "Substantive due process is hard."To trial! The Sheriff's Office of Pasco County, Florida ran a program called "predictive policing," harassing people and their family members in their homes because they suspected those people might commit crimes in the future. The program unfolded like a dystopian nightmare for many county residents, including Robert Jones and his son (who was on the future-suspect list). When deputies decided Robert wasn't cooperating fully, they arrested him several times on bogus charges. IJ went to federal court to stop the Orwellian scheme in 2021. And after the Sheriff resisted our efforts at every turn this week the court allowed the case to go to trial.

The post Short Circuit: A Roundup of Recent Federal Court Decisions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Mark Movsesian] Can a Public School Ask Students to State their Religion?

[Overzealous school administrators should think about students' privacy rights]

Last month, at the end of a three-year saga, the U.S. Department of Education ruled on a complaint that New Jersey parents had filed against the Cedar Grove School District. The conflict is interesting for what it suggests about overreaching school administrators and about the capacity of persistent parents who believe their kids' rights have been violated to get things done.

Back in 2021, without giving parents prior notice, the district surveyed elementary, middle and high school students about a variety of sensitive topics, including the students' gender identity, race, ethnicity and, in the case of high school students, religious affiliation. The district argued that it was collecting the students' information confidentially in the interests of promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion.

When they learned about the surveys, many parents objected. One of those parents was my colleague at St. John's Law, Patricia Montana. As she recounts in a recent Legal Spirits podcast, with a little research, she discovered that the surveys violated several state and federal privacy laws, including, with respect to the question about religious affiliation, the federal Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment, or PPRA. The PPRA requires a school district that wishes to survey students on certain subjects, including religious affiliation, to notify parents in advance and allow parents an opportunity to opt their children out of participation.

The district didn't act on the parents' complaints, so the parents contacted the NJ and US Departments of Education for help. The NJ authorities quickly sided with the parents and ordered the district to destroy the results of the surveys. The US DOE delayed giving an answer, for reasons that are unclear, so Montana and the parents sued. Last month, US DOE finally ruled—again, in favor of the parents. The US DOE ordered the district to train its employees so that violations of the PPRA's parental notification and opt-out provision do not occur again (and to provide documentation of such training) and, in future, to notify parents of their rights under the PPRA.

This is a fascinating story for a couple of reasons. First, it shows how overzealous school administrators can be so sure of their own good faith that they ignore basic privacy concerns. How could the administrators have thought it was wise to ask students about their religious affiliations? Just as the state has no business forbidding students from holding and expressing religious beliefs, it has no business asking students to reveal their beliefs. Even if surveys are anonymous—and Montana and the other parents were skeptical about how anonymous they were—students could legitimately feel uncomfortable revealing such sensitive information to school authorities. Plus, asking about religious affiliation, at least without advance notice to parents, is illegal—which the school administrators should have known.

Second, the story shows that parents can prevail against school bureaucracies. True, some of the parents' success here resulted from the serendipitous fact that one of them just happened to be a lawyer, who saw that what the district had done was illegal. That won't always be the case, of course. But with luck and persistence, it is possible to win an important battle every now and then. That's worth remembering as another school year begins.

You can listen to my podcast with Professor Montana here.

The post Can a Public School Ask Students to State their Religion? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Private Universities That Reject First Amendment Principles Put Themselves At Legal Risk (Updated)

[Conforming speech policies to the First Amendment would serve private universities well, legally and otherwise.]

As private institutions, private universities are not legally obligated to comply with the First Amendment. Some university administrators relish this fact, and think this is a reason to adopt and enforce policies related to speech and expression that would not pass First Amendment muster. Some may even think this approach makes sense as a matter of reducing legal risk, given the existence of federal civil rights laws and the like. This is a mistake.

Failing to adopt and enforce speech policies that follow the First Amendment is actually a source of legal risk and potential liability, as Northwestern law professors Max Schanzenbach and Kimberly Yuracko explain in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Universities are facing a tsunami of federal enforcement actions and private litigation stemming from their responses — or their lack of one — to campus protests. Some universities still do not realize how legally exposed they are. Their own speech policies are a big part of the problem.

Private universities are not bound by the First Amendment, but they are bound by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act to enforce their policies in a way that does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin. But many universities have student-speech policies that are inconsistent, vague, and in some cases seemingly illegal on their face. . . .

the problem is not simply that universities have poorly written policies. It is that such policies are likely to lead to discriminatory enforcement. Universities are too one-sided and too politically homogeneous to be able to enforce ambiguous and vague policies in a neutral way.

As we have seen from recent campus controversies, universities get themselves in particular trouble when they do not enforce speech, expression, and protest policies in a neutral and consistent fashion. Thus, private universities that seek greater discretion in what sorts of speech and expression to allow actually put themselves at greater legal risk under federal law.

As Schanzenbach and Yuracko explain, conforming speech policies to the First Amendment solves these problems.

private universities should voluntarily commit to following the First Amendment with regard to student speech. Doing so will not shield universities from their Title VI obligations, but it will make compliance easier for several reasons. Committing to the First Amendment makes consistency across cases more likely. From a legal perspective, the main risk to universities from existing speech policies flows from their inconsistent and ideologically driven application. The First Amendment mitigates this risk in the first instance by simply shrinking the class of cases plausibly subject to university sanction. With less speech subject to punishment, there are fewer opportunities for administrative bias, inconsistency, and error.

Committing to the First Amendment also provides greater clarity regarding the scope of protected speech. While university speech codes are often vague and the outcomes of disciplinary proceedings secret, making it difficult for students and adjudicative bodies to understand the boundaries and parameters of university codes, there is a robust body of First Amendment case law to guide university decisions.

One thing that many university administrators seem to forget is that statutes like Title VI cannot require universities to suppress First Amendment-protected speech. For starters, the federal government cannot adopt and enforce a statute that violates the Constitution. Moreover, state universities–which are clearly bound by the First Amendment–are also fully capable of complying with statutes like Title VI.

One thing I have always found curious about university administrators who seek to avoid conforming their policies with the First Amendment is that they are implicitly adopting at least one of two arguments. Either they believe that their students, staff, and faculty are not deserving of the same speech and expression rights as their state university counterparts, or they believe that (as administrators) they are less capable of fulfilling the university's educational and truth-seeking missions than their state university counterparts. Were I an administrator at a private university, I would be embarrassed to embrace either premise, yet here we are.

[Note: I recognize that some universities have religious or other missions that may justify a different approach, but that is not the case at most private universities.]

Of course there are other reasons why private universities should embrace First Amendment values. Among other things, this can help ensure that universities protect divergent viewpoints, foster an environment of open inquiry, and support academic freedom. Indeed, there are few things a university can do that are more integral to its educational and truth-seeking mission than to safeguard the fullest possible right to hold and express opinions, to speak and write, to listen, challenge, inquire and learn. But if that were not reason enough, adopting this sort of standard can reduce a university's legal risk too.

UPDATE: Perhaps due to lack of clarity on my part, some readers seem to misunderstand the claim about why neutrality and consistency reduces legal risk for universities. To clarify, my claim (and the claim I understand Schanzenbach and Yuracko to be making) is not that Title VI requires private universities to be ideologically neutral or consistent. As private institutions, they have no legal obligation to be neutral about ideological or other matters, and no obligation to be consistent beyond that which is entailed in their own voluntarily assumed legal commitments (such as commitments to respect academic freedom and the like).

The claim here is that a lack of neutrality and consistency in certain instances that implicate matters covered by Title VI (such as, say, the handling of protest activity that may implicate protected classes) can be a source of legal risk, and that such neutrality and consistency can protect against Title VI liability. Further, a commitment to adhere to First Amendment standards can help ensure that a university maintains a sufficiently neutral and consistent posture that will reduce its legal vulnerability. Obviously, a university that neutrally and consistently allows for overt racial harassment or other conduct that is not plausibly protected by the First Amendment could not use its consistency or neutrality as a defense, but that is not a position I understand any university administrator to be advocating.

The post Private Universities That Reject First Amendment Principles Put Themselves At Legal Risk (Updated) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Private Universities That Reject First Amendment Principles Put Themselves At Legal Risk

[Conforming speech policies to the First Amendment would serve private universities well, legally and otherwise.]

As private institutions, private universities are not legally obligated to comply with the First Amendment. Some university administrators relish this fact, and think this is a reason to adopt and enforce policies related to speech and expression that would not pass First Amendment muster. Some may even think this approach makes sense as a matter of reducing legal risk, given the existence of federal civil rights laws and the like. This is a mistake.

Failing to adopt and enforce speech policies that follow the First Amendment is actually a source of legal risk and potential liability, as Northwestern law professors Max Schanzenbach and Kimberly Yuracko explain in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Universities are facing a tsunami of federal enforcement actions and private litigation stemming from their responses — or their lack of one — to campus protests. Some universities still do not realize how legally exposed they are. Their own speech policies are a big part of the problem.

Private universities are not bound by the First Amendment, but they are bound by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act to enforce their policies in a way that does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin. But many universities have student-speech policies that are inconsistent, vague, and in some cases seemingly illegal on their face. . . .

the problem is not simply that universities have poorly written policies. It is that such policies are likely to lead to discriminatory enforcement. Universities are too one-sided and too politically homogeneous to be able to enforce ambiguous and vague policies in a neutral way.

As we have seen from recent campus controversies, universities get themselves in particular trouble when they do not enforce speech, expression, and protest policies in a neutral and consistent fashion. Thus, private universities that seek greater discretion in what sorts of speech and expression to allow actually put themselves at greater legal risk under federal law.

As Schanzenbach and Yuracko explain, conforming speech policies to the First Amendment solves these problems.

private universities should voluntarily commit to following the First Amendment with regard to student speech. Doing so will not shield universities from their Title VI obligations, but it will make compliance easier for several reasons. Committing to the First Amendment makes consistency across cases more likely. From a legal perspective, the main risk to universities from existing speech policies flows from their inconsistent and ideologically driven application. The First Amendment mitigates this risk in the first instance by simply shrinking the class of cases plausibly subject to university sanction. With less speech subject to punishment, there are fewer opportunities for administrative bias, inconsistency, and error.

Committing to the First Amendment also provides greater clarity regarding the scope of protected speech. While university speech codes are often vague and the outcomes of disciplinary proceedings secret, making it difficult for students and adjudicative bodies to understand the boundaries and parameters of university codes, there is a robust body of First Amendment case law to guide university decisions.

One thing that many university administrators seem to forget is that statutes like Title VI cannot require universities to suppress First Amendment-protected speech. For starters, the federal government cannot adopt and enforce a statute that violates the Constitution. Moreover, state universities–which are clearly bound by the First Amendment–are also fully capable of complying with statutes like Title VI.

One thing I have always found curious about university administrators who seek to avoid conforming their policies with the First Amendment is that they are implicitly adopting at least one of two arguments. Either they believe that their students, staff, and faculty are not deserving of the same speech and expression rights as their state university counterparts, or they believe that (as administrators) they are less capable of fulfilling the university's educational and truth-seeking missions than their state university counterparts. Were I an administrator at a private university, I would be embarrassed to embrace either premise, yet here we are.

[Note: I recognize that some universities have religious or other missions that may justify a different approach, but that is not the case at most private universities.]

Of course there are other reasons why private universities should embrace First Amendment values. Among other things, this can help ensure that universities protect divergent viewpoints, foster an environment of open inquiry, and support academic freedom. Indeed, there are few things a university can do that are more integral to its educational and truth-seeking mission than to safeguard the fullest possible right to hold and express opinions, to speak and write, to listen, challenge, inquire and learn. But if that were not reason enough, adopting this sort of standard can reduce a university's legal risk too.

The post Private Universities That Reject First Amendment Principles Put Themselves At Legal Risk appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Confusing Use of Another Political Group's Name as "Source Identifier" May Lead to Trademark Injunction

[A dissenting subgroup of the Libertarian Party of Michigan was barred from "from identifying as the Libertarian Party of Michigan in the provision of services."]

From Wednesday's decision in Libertarian National Committee, Inc. v. Saliba, by Sixth Circuit Judge Julia Smith Gibbons, joined by Judges Guy Cole and Chad Readler:

This trademark action arises out of a dispute within the Libertarian Party of Michigan (referred to by name or as the "Michigan affiliate"). The Libertarian National Committee, Inc. ("LNC") sued dissenting members of the Michigan affiliate—mainly former officers of the affiliate or board members of local parties—for using the LNC's trademark to hold themselves out as the official Michigan affiliate after a turnover of power resulted in two factions claiming to hold power.

The district court granted the LNC's request to preliminarily enjoin the dissenting members' use of the mark, and the dissenting members appealed. They argue that the district court's application of the Lanham Act to the context of noncommercial speech both unduly expands the Act and violates the First Amendment. Even if the Lanham Act covers the dissenting members' use of the trademark, they argue that their use was authorized and not likely to cause confusion [details on this omitted -EV].

The circuit court largely agreed with the district court, concluding that trademark law may permissibly restrict confusing uses of another entity's name as "designat[ing the] source" of speech, goods, and services, even in political speech rather than commercial advertising:

In Taubman Co. v. Webfeats (6th Cir. 2003), this Circuit addressed the use of a shopping mall's trademark in domain names by the creator of a "fan site" and, after the relationship between the parties soured, a gripe site for that mall. The website creator contended that his purpose for using the mall's trademark in his websites was expressive rather than commercial, and thus outside of the realm of the Lanham Act and protected by the First Amendment. In combatting the defendant's allegation that the Lanham Act conflicted with the First Amendment, the Taubman Court reasoned that the Lanham Act is constitutionally sound "because it only regulates commercial speech, which is entitled to reduced protections under the First Amendment." …

In explaining why the defendant's use of the mall's mark was protected expression, the Taubman Court expounded that the defendant used the mark to comment on the trademark holder—not "to designate source." Jack Daniel's Properties, Inc. v. VIP Prods. LLC (2023). In other words, the defendant did not use the mark to pass off the goods or services advertised on his website as those of the shopping mall.

Since Taubman, the Supreme Court has explained how the Lanham Act and the First Amendment interact when a defendant uses a trademark to misrepresent his or her goods or services as those of or associated with the trademark owner. Just last year, the Court noted that where a defendant uses a trademark as a source identifier, "[t]he trademark law generally prevails over the First Amendment." Jack Daniel's Properties. This is because use of a trademark as a source identifier undermines the primary function of trademark law, which is to prevent "misinformation[ ] about who is responsible for a product" or service. Such is true even where the defendant's use of the mark also conveys an expressive message. Cf. San Francisco Arts & Athletics, Inc. v. U.S. Olympic Comm. (1987) ("The mere fact that the [nonprofit defendant] claims an expressive, as opposed to a purely commercial purpose does not give it a First Amendment right to appropriate to itself the harvest of those who have sown."). In that circumstance, "the likelihood-of-confusion inquiry does enough work to account for the interest in free expression."

We take this opportunity to clarify that Taubman's language limiting the Lanham Act's coverage, while implicated where a defendant uses the mark purely for protected expression, like satire, critique, or commentary, does not prohibit application of the Lanham Act to a defendant who uses the trademark to identify the source of his or her competing goods or services. Because the defendants here used the LNC's trademark to speak as the Libertarian Party of Michigan, defendants used the mark to designate the source of their political services as affiliated with the LNC, thus implicating "the core concerns of trademark law" and rendering Taubman inapposite.

Defendants resist this conclusion by emphasizing that Jack Daniel's Properties contemplated trademark infringement in the context of commercial products—a context in which trademark law traditionally and comfortably operates. True, trademark law was designed to combat potential consumer confusion and the theft of the trademark owner's goodwill in the context of commercial sales. And we acknowledge that outside of the facts before us, speech rendered in connection with the provision of political services typically constitutes political speech awarded heightened protection under the First Amendment. But we find support in Jack Daniel's Properties for our position that, in the narrow context where a defendant uses the trademark as a source identifier, the Lanham Act does not offend the First Amendment by imposing liability in the political arena.

While explaining why a predicate First Amendment test, rather than ordinary trademark scrutiny, does not apply when a defendant uses a trademark as a source identifier, Jack Daniel's Properties cited a case remarkably similar to the case at hand.. In United We Stand America, Inc. v. United We Stand, America New York, Inc. (2d Cir. 1997), the Second Circuit contemplated a trademark infringement action by United We Stand America, Inc., which owned the slogan, "United We Stand America." After friction within the group, the defendant created an offshoot political coalition, "United We Stand, America New York, Inc." which also used the slogan to engage in political activities.

The Second Circuit deemed the defendant's trademark use within the scope of the Lanham Act and outside the protection of the First Amendment because the offshoot group used the trademark "as a source identifier" for the group's political services rather than to pose "commentary on [the trademark's] owner." Accordingly, such use subjected the defendant to Lanham Act liability even though the offshoot coalition "might communicate its political message more effectively by appropriating [the trademark]."

The Supreme Court cited United We Stand with approval of the Second Circuit's decision to apply ordinary trademark scrutiny even though the defendant's use of the slogan also "had expressive content." Jack Daniel's Properties. Because the offshoot political coalition used the trademark "to suggest the 'same source identification' as the original 'political movement,'" such use was not insulated from Lanham Act liability. Id. (quoting United We Stand, 128 F.3d at 93). We find the Supreme Court and the Second Circuit's reasoning persuasive. Focusing on the use of a trademark as a source identifier adequately accounts for the core interests undergirding trademark law without "suck[ing] in speech on political and social issues through some strained or tangential association with a commercial or transactional activity." Radiance Found., Inc. v. N.A.A.C.P., 786 F.3d 316, 323 (4th Cir. 2015). Thus, in the narrow context before us, where a defendant uses a trademark as a source identifier, we find the extension of the Lanham Act into the political sphere appropriate.

Defendants next contend that, as a political entity, they do not render the type of services included in the scope of the Lanham Act. Accordingly, they argue, their use of the LNC's mark in connection with these services is not prohibited by the Lanham Act. A "service" is an "amorphous concept, 'denot[ing] an intangible commodity in the form of human effort, such as labor, skill, or advice.'" As defendants used the LNC's trademark to advertise a political convention, operate a website, promulgate political news and party activities, file campaign finance reports, endorse candidates, and solicit donations, they "unquestionably render[ed] a service" contemplated by § 1114(1)(a). United We Stand (finding "services characteristically rendered by a political party to and for its members, adherents, and candidates," like political organizing, maintaining an office, endorsing candidates, and distributing partisan material to be "services" under the Lanham Act)…. [T]he First Amendment tolerates the Lanham Act's interjection to prevent use of a trademark as a source identifier in a manner that creates confusion as to the source of the defendant's political services.

{ The district court clarified that the injunction merely prohibits defendants from identifying as the Libertarian Party of Michigan in the provision of services, it does not prevent them from identifying as members of the Libertarian Party or the Michigan affiliate, or from using the trademark to criticize or comment on either entity. We emphasize again that the Lanham Act does not restrict defendants' ability to engage in political speech. It merely restricts defendants from using the LNC's trademark to identify as the Libertarian Party of Michigan in connection with providing or advertising their own political services.}

"If different organizations were permitted to employ the same trade name in endorsing candidates, voters would be unable to derive any significance from an endorsement, as they would not know whether the endorsement came from the organization whose objectives they shared or from another organization using the same name." United We Stand America. Thus, we agree with the district court that defendants' use of the LNC's trademark in connection with the provision of competing political services created a high likelihood of confusion for consumers, i.e., potential voters, party members, and, in the case of solicitations not accompanied by a clear disclaimer, donors.

Defendants' use of the "Libertarian Party" mark meant that two different entities simultaneously held themselves out as the Libertarian Party of Michigan. A potential voter visiting defendants' website would not be able to tell if the platforms defendants espoused or events they advertised were actually affiliated with the Libertarian Party. Given defendants' use of the LNC's exact mark in the provision of competing political services to the same target population, such risk is at play here. And this risk is not hypothetical—the LNC submitted at least some evidence of actual confusion about the sponsorship of competing conventions. This likelihood of confusion is sufficient to support a Lanham Act claim.

Defendants also used the LNC's trademark on their website to solicit donations. In connection with the donation tab, defendants displayed one of two pop-up disclaimers notifying the potential donor of the governance dispute, the LNC's recognition of the Chadderdon-led faction, and that any donations would be going solely to defendants. The disclaimers also included hyperlinks to the Chadderdon-led affiliate's website. By clearly explaining the identity of the donation recipient, these disclaimers ameliorated the confusion the Lanham Act seeks to prevent. The disclaimers also resemble those we have previously found sufficient to eliminate a likelihood of confusion. Accordingly, defendants' use of the trademark in connection with their online solicitation of donations, when accompanied by appropriate disclaimers, does not create a sufficient likelihood of confusion as to the recipient of the funds and thus cannot be the predicate for Lanham Act liability….

We affirm the preliminary injunction granted except as to defendants' online solicitation accompanied by clear disclaimers.

Joseph J. Zito (DNL Zito Castellano) represents the plaintiff.

The post appeared first on Reason.com.

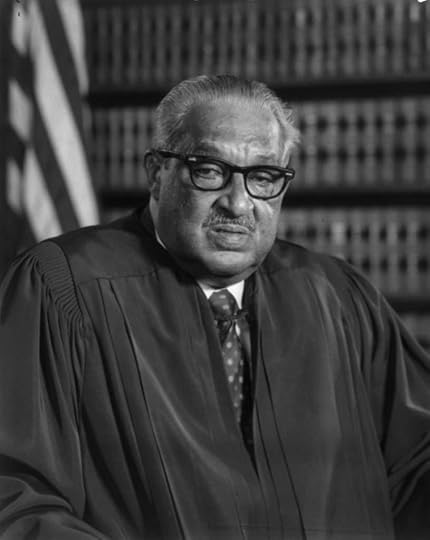

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 30, 1967

8/30/1967: Justice Thurgood Marshall takes the oath.

Justice Thurgood Marshall

Justice Thurgood MarshallThe post Today in Supreme Court History: August 30, 1967 appeared first on Reason.com.

August 29, 2024

[Josh Blackman] National Constitution Center Podcast on United States v. Trump (Florida Edition)

[Can the Attorney General Appoint a Special Counsel?]

Today I recorded the We the People Podcast with Jeff Rosen and Matt Seligman. We discussed one of several cases called United States v. Trump. No, not the immunity case. Instead, we talked about the appointment of Jack Smith as special counsel. I though this was a wide-ranging and informative conversation. Also, Seligman and I both presented arguments before Judge Cannon in March.

You can listen here.

The post National Constitution Center Podcast on United States v. Trump (Florida Edition) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Some Thoughts on Raising the Sanity Waterline

[I am happy to share this guest post from Professor Seth Barrett Tillman, which addresses some discourse on legal academia, including a recent post by Will Baude.]

There has been much back-and-forth on social media and blogs lately about what constitutes good behaviour for academics. Having been in academic affrays from time to time—mostly unsought by me—I thought I would add my thoughts on that and some closely related issues.

1. E-mail.For academia to work, we have to be free to talk to one another. And that means contacting one another, without fear of sanctions. From time to time, I have sent or offered to send other academics, in law and other fields, courtesy copies of my drafts and published articles. I often make such offers to people whom I have cited or people who have written about one of the topics discussed in my paper. Usually, I will receive one of two pro forma responses. Many will write back: "Thank you very much, I am sure I will benefit from reading your contribution to the literature, as time allows." Alternatively, I will sometimes receive: "Really—no need for e-mail contact in the future—I stay abreast of developments in the literature." The virtue of these two responses is their directness, clarity, and guidance: they leave you no doubt about whether future contacts are desired. Yes to the former; no to the latter.

Still, on other occasions, I have not received any response at all. And that produces a quandary: Do you contact that person again? So, a year or two or three later, I might have another paper, and I might e-mail a non-responding recipient a second time or third time or fourth time. At that juncture, I might receive a pro forma response. But I might not. At that juncture, I might get a (pleasant) response along these lines:

Professor A: Dear Professor Tillman—thank you so much for writing me. Your article comes timely as I am writing/teaching on this topic currently, and I will be sure to cite/discuss your new perspective. (Albeit, I am not saying, I agree with it!) I now see also that you wrote me on several prior occasions. My mistake—your e-mails went to my spam folder, or perhaps, I just did not recognize your name and mistakenly ignored your e-mail. I won't do so again.

This has happened to me more than once, and it has led to fruitful contacts, intellectual exchanges, and occasionally, friendships.

On other occasions, you get another sort of response.

Professor B: Mr Tillman, I have received your recent e-mail, as well as several prior e-mails. I chose not to respond to your prior e-mails. But you still persist in contacting me. You should have taken the hint. But seeing that you have not: stop now.

In situations involving a non-responding e-mail recipient, we can let Professor-A or Professor-B set the norm for good (academic) behaviour. We can value autonomy, privacy, and peace of mind. If so, a first-non-response becomes a basis for a sender's refraining from future contacts. Or, we could let Professor-A set the norm. In that situation, a non-response counts for nothing because it lacks clarity and directness. This leaves the possibility open that future contacts will be welcomed. As they sometimes are.

So what to do?

Given that our business—academia—exists to develop ideas, my view is that one ought to risk upsetting many Professor-B-type-individuals to discover any one Professor-A. It is this latter strategy that permits the exchange of ideas, even if it risks some unwelcome and some unpleasant contacts. I might add: unpleasant for both the recipient and the sender. To put it another way, I do not think we should let the most fragile personalities amongst us set the ground rules for intellectual contact.

2. Responses As Counter-Authority.I have had the good fortune of putting forward novel ideas from time to time. Putting forward a new idea poses challenges. One such challenge is: What to do with counter-authority? Any development of counter-authority runs the risk that one will present such evidence in a biased manner in order to insulate one's idea from criticism. And even if one does not do that, more than a few readers might very well suspect that you have done so. That's why in the past, I have actively solicited responses to my articles to be published along with my own. I either reached out to the respondent myself (usually to several potential respondents) or had the journal, where my publication was placed, do so. See, e.g., Lawson (2005); Levinson (2006); Bruhl (2007); Kalt (2007); Calabresi (2008); Blomquist (2009); Prakash (2009); Sheppard (2009); Bailey (2010); Peabody (2010); Teachout (2012, 2014, 2016); cf., e.g., Hoffer (2014); Kalt (2014); Melton (2014); Stern (2014); Baude (2016). In one of these exchanges, I had good reason to believe that I had information unknown to the respondent—so, I sent that information to the respondent, leaving it to that individual how (if at all) to make use of the information and how to present it.

There are many benefits to this approach, albeit, there are some downsides too. On the upside: First, it frees up your allotted journal space to present your idea as a standalone idea. Second, it leaves it to others how best to knock your idea down—and such points, as necessary, can be addressed in replies. Third, the exchange itself makes both publications attractive to readers—as the exchange itself is some indicia that a serious idea is at stake, and that the idea and counterpoints are well presented. Fourth, by inviting a third party to respond, you often make a friend, particularly if that person is a junior academic who is happy to have an extra publication. The downside is that there will be a few less-than-well-informed readers who are not bemused by your new idea, who believe that they have a monopoly of expertise, and who are entirely unaware of the existence of the response, and so, they are led to think that obvious counter-authority has been ignored—if not wilfully hidden from the readers. (Of course, they know all about what was purportedly hidden.) Here too, I do not think we academics should live in fear of the most mistaken and most suspicious amongst us—otherwise, we lose the advantages I outlined above. See, above, First through Fourth.

3. Changing One's Mind.It is a good thing that what are considered settled issues are re-opened from time to time. Moreover, people should get to change their minds. Indeed, if a person has never changed his mind or has never expressed doubt about ideas he has held, then it is fair to ask what sort of mind that person has. When a person changes his mind—particularly in public—they court opprobrium for doing so. Rather than punishing people for risking their reputation, we should praise their courage.

Recently, Professor Calabresi has changed his mind. In 2008, he thought I was wrong about one of my novel ideas about the Constitution's "office"- and "officer"-language. More recently, he has taken the opposite view. Professor Baude has moved in the opposite direction in regard to my novel idea about the Constitution's "office"- and "officer"-language. In 2016, he put forward praise. More recently, he has taken a different position. Although I understood their 2008 and 2016 views, I really do not understand why they have changed from their prior positions. But that's my problem, not theirs. They have started a new conversation. They work on their schedules; they don't owe me a further detailed explanation about why they changed their views. Perhaps, they are each satisfied that they have put forward grounded, fully fleshed-out explanations for their change of position. Perhaps, they think that I just do not understand their new reasons for having changed their minds. And if so, they have no reason to return to these issues.

In any event, both Calabresi, in 2008, and Baude, in 2016, and both Calabresi and Baude during the recent Trump-related ballot-access litigation (2023 and 2024) spelled my name correctly and cited my material correctly. So, I have nothing about which to complain. I hope that one day they both return to these issues, but that's just a hope. And if they do not do so, they and I have plenty of other things to do with our time.

4. What Academics Should Not Do On Social Media.There are more than a few legal academics whose behaviour on social media fails to meet the standard for good behaviour. They publicly deprecate ideas, causes, individuals, and organizations in hyperbolic terms. The problem here is not the lack of public reason. (That's a problem, but it is not the problem.) The problem here is not the injury, deserved or not, incurred by the targets of their tweets, and the concomitant social media mob. (These are problems too, at least, where the injury is not entirely deserved.) Rather, the problem is the model these academics are setting for students—including their own students.

The legal academics who engage in this sort of behaviour have tenure. They are part of a protected class enjoying institutional goodwill and privilege arising in connection with special protections which accrued to universities during feudalism. Our students do not enjoy such benefits. And employers, public and private, now monitor the social media footprints of both those who apply for work and extant employees. When students copy the less than wholesome behaviour of these academics, they may find themselves unemployed and unemployable. These academics are trading their students' futures for the rush of an exhilarating barb.

Anyway, that is social media. Academic articles are, arguably, another thing. Perhaps the standards are different. Still, if your articles systematically describe others' work-product as "appalling" or "wacky" or "bonkers" or in other similar language … you might not be Raising the Sanity Waterline. William Baude & Michael Stokes Paulsen, The Sweep and Force of Section Three, 172 U. Pa. L. Rev. 605 (2024).

The post Some Thoughts on Raising the Sanity Waterline appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Biden Administration Restarts CHNV Immigration Parole Program for Migrants From Four Latin American Nations

[The program should not have been suspended to begin with. The restart, unfortunately, includes some dubious security measures that will make applications more difficult and time-consuming.]

Venezuelans fleeing the socialist regime of Nicolas Maduro. (NA)

Venezuelans fleeing the socialist regime of Nicolas Maduro. (NA)

Today, the Biden Administration Department of Homeland Security restarted the CHNV (AKA "CNVH") migrant sponsorship program for migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela:

The Biden administration is reopening an updated version of a migrant sponsorship program it paused abruptly earlier this summer due to concerns about fraud, Department of Homeland Security officials said Thursday.

First set up in late 2022 and expanded in early 2023 as a way to divert migrants away from the U.S.-Mexico border, the initiative allows up to 30,000 people from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela to fly to the U.S. each month if U.S.-based sponsors successfully apply to support them….

After a weeks-long pause, the Department of Homeland Security is restarting the program with an enhanced screening process for those applying to sponsor migrants under the policy. The government will now require those who wish to sponsor migrants to submit fingerprints for the vetting process. Officials also plan to more closely review the financial and criminal records of would-be sponsors, and increase scrutiny of repeat sponsors….

Sponsors need to be U.S. citizens or permanent residents, or hold another legal immigration status. The fraud concerns about the program centered around would-be sponsors, not the migrants, who also undergo security vetting before being allowed to book travel to the U.S.

DHS officials said an initial probe into potential fraud within the program found that a majority of cases of concern had a "reasonable explanation," including filing errors. But officials said the review did find some cases involving fraud, including prospective sponsors using fraudulent Social Security numbers. A small number of applicants have been referred to law enforcement for further investigation and potential prosecution, officials said.

It's good that the administration has restarted the program. In a previous post, I explained why it should never have been suspended in the first place; see also this Reason article by Cato Institute immigration policy specialists David Bier and Alex Nowrasteh. The fact that DHS appears to have found only a few cases of fraud by sponsors and none at all by actual migrants, is further evidence that the pause was a mistake.

I worry that the new fingerprinting requirement and other additional vetting will make an already excessively bureaucratic application process more complicated and time-consuming, without much affecting the already-low rate of fraud. DHS should be simplifying the process, not making it more difficult. The administration would also do well to drop the arbitrary 30,000 per month cap for migrants from all four nations combined.

The CHNV program is vital as both a way to help migrants escape horrific oppression and violence (including at the hands of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela's brutal socialist governments), and for reducing disorder at the border. CHNV migrants, like previous migrants from Latin America, also make valuable contributions to our economy.

As noted in my previous post about the pause, I am a sponsor in the Uniting for Ukraine program, which is very similar to CHNV and uses the same forms and procedures (at least up until now); indeed, CHNV is largely based on U4U. I have also advised CHNV sponsors and applicants (on an unpaid basis). I am, therefore, familiar with how the program works, and with the application process.

The post Biden Administration Restarts CHNV Immigration Parole Program for Migrants From Four Latin American Nations appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers