Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 2555

May 15, 2012

Is JP Morgan’s $2 Billion Loss a Mountain or a Molehill?

Yale Law School’s Jonathan Macey places JP Morgan’s $2 billion loss in perspective. His article begins:

Regulators, politicians and news reporters are hysterical at the news of J.P. Morgan’s recent $2 billion trading loss. The Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating to see whether laws were broken.

We appear to be on the verge of making it a crime for a business to lose money. The truth is that nobody should care about J.P. Morgan’s loss—nobody except J.P. Morgan stockholders and a few top executives and traders who will lose their bonuses or their jobs in the wake of this teapot tempest. The three executives with the closest ties to the losses are already out the door.

After the $2 billion in losses, J.P. Morgan still had $127 billion in equity. This means that J.P. Morgan could lose another $100 billion and creditors would still have an equity cushion that could absorb 10 times the losses that the bank suffered on this trade. The trading loss wasn’t close to apocalyptic even for shareholders. J.P. Morgan’s shares dropped 9.28% in the wake of the loss. A shareholder with a $100,000 investment in J.P. Morgan would see the value of his investment reduced to $90,720, hardly a financial Chernobyl.

The $2 billion loss also resulted from trades designed to hedge against the threat of even bigger losses. Macey also explains why JP Morgan’s loss is not a justification for additional government regulation.

The real lesson of what J.P. Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon has called the bank’s “egregious failure” in risk management is that hedging is far more difficult to do in real life than it appears to be in theory—because the real world is a complicated place. The trades that J.P. Morgan made were extremely complex, and it certainly appears that they did not work the way that they were supposed to. But the reason that markets work better than central planning is because market participants learn from experience, and they learn fast and thoroughly because they suffer significant losses when their investments, whether they be hedges or not, turn out badly.

Thus, far from serving as a pretext to justify still more regulation of providers of capital, J.P. Morgan’s losses should be treated as further proof that markets work. J.P. Morgan and its competitors will learn from this experience and do a better job of hedging the next time. They will learn because they have to: In the long run their survival depends on it. And in the short run their jobs and bonuses depend on it.

May 14, 2012

Jeffrey Toobin on Citizens United

The latest New Yorker has an extensive excerpt of Jeffrey Toobin’s forthcoming book, The Oath: The Obama White House vs. the Supreme Court, focusing on the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision. The story, “Money Unlimited: How Chief Justice John Roberts orchestrated the Citizens United decision,” is everything you’d expect from a Toobin piece. It’s engaging and informative, with exclusive behind-the-scenes reporting of how the decision came to be. This stuff is catnip for court watchers. Yet the article also contains plenty of subtle (and not-so-subtle) spin in service of Toobin’s broader narrative of an out-of-control conservative court. As a consequence, Toobin paints a somewhat misleading picture of the case and the Court.

The heart of Toobin’s article tells the story of how Citizens United metastasized from a narrow case about the application of federal campaign finance law to an obscure conservative documentary to a significant decision vindicating the First Amendment rights of corporations. As Toobin tells the tale, after the case was first argued Chief Justice Roberts drafted a narrow opinion that would have held for Citizens United on statutory grounds, but leaving the statutory regime intact. The vote would still have been 5-4, but it would have been a far less significant case. Justice Kennedy was not happy with this result, however, and authored a concurrence calling for a broader holding that would rest on First Amendment grounds. Kennedy’s concurrence apparently swayed enough of the court’s conservatives that Roberts initially acquiesced. Such a broad ruling would be improper, the court’s liberals complained, as the broader First Amendment questions had not been briefed and were not properly before the Court. Yet as there was no interest in a narrower holding, the Court ordered a reargument with supplemental briefing that would place the First Amendment question front and center.

Toobin dwells on Justice Stevens’ complaint that the Court’s broad holding in Citizens United was unnecesary, as the Court could have held for the petitioners on narrower, statutory grounds. Yet as Toobin’s own reporting confirms, no one other than Chief Justice Roberts had any interest in resolving the case on such grounds. Even when the case was first argued, not a single liberal justice was prepared to side with Citizens United, in no small part because the statutory argument was so weak.

Toobin criticizes the Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart for a concession at the first oral argument that may have sealed the government’s fate.

Since McCain-Feingold forbade the broadcast of “electronic communications” shortly before elections, this was a case about movies and television commercials. What else might the law regulate? “Do you think the Constitution required Congress to draw the line where it did, limiting this to broadcast and cable and so forth?” Alito said. Could the law limit a corporation from “providing the same thing in a book? Would the Constitution permit the restriction of all those as well?”

Yes, Stewart said: “Those could have been applied to additional media as well.”

The Justices leaned forward. It was one thing for the government to regulate television commercials. That had been done for years. But a book? Could the government regulate the content of a book?

“That’s pretty incredible,” Alito responded. “You think that if a book was published, a campaign biography that was the functional equivalent of express advocacy, that could be banned?”

“I’m not saying it could be banned,” Stewart replied, trying to recover. “I’m saying that Congress could prohibit the use of corporate treasury funds and could require a corporation to publish it using its—” But clearly Stewart was saying that Citizens United, or any company or nonprofit like it, could not publish a partisan book during a Presidential campaign. . . .

Stewart was wrong. Congress could not ban a book. McCain-Feingold was based on the pervasive influence of television advertising on electoral politics, the idea that commercials are somehow unavoidable in contemporary American life. The influence of books operates in a completely different way. Individuals have to make an affirmative choice to acquire and read a book. Congress would have no reason, and no justification, to ban a book under the First Amendment.

Yet here it is Toobin who is wrong, not Stewart. The statutory provision at issue was limited to broadcast, cable and satellite communications, and the film at issue was to be shown as a cable on-demand program, but the government never sought to defend the law on the basis that it was limited to electronic media. After all, the point of the was to limit the role of money in campaigns, not limit television advertising. The position the government was defending was that Congress could limit corporate expenditures related to campaigns, not that it could regulate TV. Under this theory, a corporate-funded book with impermissible campaign-related content would receive no more First Amendment protection than a corporate-funded video or film, just as Stewart said. If this is an incredible proposition, that says more about the position the government sought to advance than it does Stewart’s oral argument. Campaign finance activist Fred Wertheimer made the same concession when pressed by the NYT. It’s true that Solicitor General Elena Kagan would back away from this position when it was her turn to argue the case at the second oral argument, but not without first acknowledging that the statute’s language could apply to “full-length books” and that there would, in the government’s view, be no problem with banning corporate-funded pamphlets.

Like many of the decision’s critics, Toobin suggests Citizens United is best seen as the product of the “aggressive conservative judicial activism” of Chief Justice Roberts and the court’s conservative majority.

Citizens United is a distinctive product of the Roberts Court. The decision followed a lengthy and bitter behind-the-scenes struggle among the Justices that produced both secret unpublished opinions and a rare reargument of a case. The case, too, reflects the aggressive conservative judicial activism of the Roberts Court. It was once liberals who were associated with using the courts to overturn the work of the democratically elected branches of government, but the current Court has matched contempt for Congress with a disdain for many of the Court’s own precedents. When the Court announced its final ruling on Citizens United, on January 21, 2010, the vote was five to four and the majority opinion was written by Anthony Kennedy. Above all, though, the result represented a triumph for Chief Justice Roberts. Even without writing the opinion, Roberts, more than anyone, shaped what the Court did. As American politics assumes its new form in the post-Citizens United era, the credit or the blame goes mostly to him.

As Toobin tells the tale, Citizens United is emblematic of the current Court’s assault on precedent and the prerogatives of the political branches. It’s a nice story, but it’s not true. “Judicial activism” is a notoriously malleable charge, but if “judicial activism” is shorthand for striking down federal statutes and overturning judicial precedents, the Roberts Court is the least “activist” court of the post-war period. As a New York Times analysis showed, the Roberts Court strikes down statutes and overturns Court precedents at a slower rate than any of is post-war predecessors, and it’s not even close. “Activism” is also a peculiar charge to make about this case, as the dissenting justices were just as reluctant to embrace a narrow statutory holding and were just as willing to overturn precedent as those in the majority. They just sought to move the law in the opposite direction. If Citizens United is supposed to be evidence of unprecedented “activism,” it’s not clear what “activism” means.

The most interesting parts of Toobin’s article are those that disclose how Citizens United was handled inside the Court. This is great stuff, and testament to Toobin’s skill as a reporter, but I still have some misgivings. We don’t know the identities of Toobin’s sources, and some of his claims are difficult to check. His story may reflect how some justices or clerks saw the case, but there may well be another side, and we won’t know until such time as the relevant court documents are released. I also cannot help but wonder whether some of Toobin’s sources, such as former Supreme Court clerks, may have violated their own ethical obligations in disclosing portions of the Court’s internal deliberations. Even if Toobin’s sources were sitting or former justices, there is something unseemly about the selective disclosure of what went on inside the Court on such a recent case.

In any event, the article is still worth reading — as I am sure Toobin’s book will be as well. Some portions will just go down better with a healthy dose of salt.

Henry Kissinger Gets TSA Pat Down

The Washington Post reports that former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger got a full pat down by the TSA at Laguardia. Maybe one of the TSA agents had been reading Christopher Hitchens.

Crossover Sensation, Justice Sotomayor

Check out today’s Hall et ux. v. United States, a bankruptcy law case in which Justice Sotomayor’s majority opinion is joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito, and Justice Breyer’s dissent is joined by Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, and Kagan. This is also a good opportunity to make sure you know what “et ux.” means; the term is no longer used in most citations, I think, but the Supreme Court and some other courts still use it in captions.

The “crossover sensation” line is borrowed from my coblogger John Elwood.

Reducing the Drug War’s Damage to Government Budgets

That’s the title of an article that I have co-authored with the Cato Institute’s Trevor Burrus, in a symposium issue of the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy. The symposium is “Law in an Age of Austerity,” and includes contributions from Charles Cooper (Treasury Dept.’s authority to index capital gains for inflation), John Eastman (state authority to enforce immigration laws), and others.

The major part of the Article details some recently-enacted criminal law and sentencing reforms in Colorado, which mitigate the fiscal damage of the drug war. The second part of the Article summarizes the fiscal benefits of ending prohibition. Finally, the Article looks at some of the legal history of alcohol prohibition, and suggests that current federal drug prohibition policies are inconsistent with the spirit of the Tenth Amendment, including state tax powers.

The Burden of Small Business Licensing

Two recent studies find that state licensing regimes for small businesses impose severe burdens on consumers and entrepreneurs alike. The first, by the libertarian Institute for Justice, finds that licensing is ubiquitous for a wide range of professions, and that it often has little or no public interest justification:

License to Work details licensing requirements for 102 low- and moderate-income occupations in all 50 states and D.C. It is the first national study of licensing to focus on lower-income occupations and to measure the burdens licensing imposes on aspiring workers….

All of the 102 occupations studied in License to Work are licensed in at least one state. On average, these government-mandated licenses force aspiring workers to spend nine months in education or training, pass one exam and pay more than $200 in fees. One third of the licenses take more than one year to earn. At least one exam is required for 79 of the occupations….

Noted licensure expert Morris Kleiner found that in the 1950s, only one in 20 U.S. workers needed government permission to pursue their chosen occupation. Today, it is closer to one in three. Yet research to date provides little evidence that licensing protects public health and safety or improves products and services. Instead, it increases consumer costs and reduces opportunities for workers….

the difficulty of entering an occupation often has little to do with the health or safety risk it poses. Of the 102 occupations studied, the most difficult to enter is interior designer, a harmless occupation licensed in only three states and D.C. By contrast, EMTs hold lives in their hands, yet 66 other occupations face greater average licensure burdens, including barbers and cosmetologists, manicurists and a host of contractor designations. States consider an average of 33 days of training and two exams enough preparation for EMTs, but demand 10 times the training—372 days, on average—for cosmetologists. “The data cast serious doubt on the need for such high barriers, or any barriers, to many occupations,” said Lisa Knepper, IJ director of strategic research and report co-author. “Unnecessary and needlessly high licensing hurdles don’t protect public health and safety—they protect those who already have licenses from competition, keeping newcomers out and prices high.”

The second new study – by Thumbtack.com and the Kauffman Foundation reinforces some of IJ’s conclusions. It consists of a nationwide survey of several thousand small business owners, and finds that, in their view, the ease of obtaining a license is the biggest public policy determinant of a state’s level of friendliness to small businesses – far more important even than tax rates:

Although taxes are a dominant topic in many discussions of a location’s attractiveness to business, our analysis indicates that small businesses tend to care more deeply about the friendliness of a region’s licensing regime by a factor of nearly two. Similarly, being subject to special regulatory requirements had a negative effect on overall small business friendliness, and among those small businesses subject to special regulations, the ease of complying with these requirements was by far the most important factor.

These results are not entirely surprising. Licensing regulations are often “captured” by interest groups seeking to keep out their competitors because most voters are unaware of them and often lack the knowledge needed to assess their quality even when they do happen to know about them. As a result, licensing regimes are often heavily influenced by lobbying from politically connected businesses seeking to keep out less influential competitors. Both consumers and potential new entrants into the market get the short end of the regulatory stick. It’s yet another example of the harm caused by political ignorance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST WATCH: I have done pro bono work for the Institute for Justice on unrelated projects.

How the British Gun Control Program Precipitated the American Revolution

I posted a draft of this article a few months ago, and I thank VC readers for some helpful comments in improving it. The final version has been published by the Charleston Law Review, and is available on SSRN. Here’s the abstract:

This Article chronologically reviews the British gun control which precipitated the American Revolution: the 1774 import ban on firearms and gun powder; the 1774-75 confiscations of firearms and gun powder, from individuals and from local governments; and the use of violence to effectuate the confiscations. It was these events which changed a situation of rising political tension into a shooting war. Each of these British abuses provides insights into the scope of the modern Second Amendment.

From the events of 1774-75, we can discern that import restrictions or bans on firearms or ammunition are constitutionally suspect — at least if their purpose is to disarm the public, rather than for the normal purposes of import controls (e.g., raising tax revenue, or protecting domestic industry). We can discern that broad attempts to disarm the people of a town, or to render them defenseless, are anathema to the Second Amendment; such disarmament is what the British tried to impose, and what the Americans fought a war to ensure could never again happen in America. Similarly, gun licensing laws which have the purpose or effect of only allowing a minority of the people to keep and bear arms would be unconstitutional. Finally, we see that government violence, which should always be carefully constrained and controlled, should be especially discouraged when it is used to take firearms away from peaceable citizens. Use of the military for law enforcement is particularly odious to the principles upon which the American Revolution was based.

Readers interested in more detail on the role of gun rights and gun control in period leading up to the Revolution, and in the remainder of 18th century America, are encouraged to read Stephen Halbrook’s excellent book The Founders’ Second Amendment, which is the result of decades of work by Halbrook in finding primary sources of the period, including newspapers, correspondence, and diaries.

On a related topic, some readers might also be interested in my 2005 article The Religious Roots of the American Revolution and the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, detailing the role of Congregationalist and other ministers in inciting the Revolution, by explaining collective self-defense of natural and civil rights as a moral and religious obligation.

May 13, 2012

Minister Prosecuted for Teaching Parishioners to Hit Children “on the Bare Buttocks with Wooden Dowels”

The Wisconsin State Journal reports:

A Dane County judge on Thursday denied a motion to dismiss charges against a Black Earth pastor convicted of conspiracy to commit child abuse for advocating the use of wooden rods to spank children as young as 2 months old.

Philip Caminiti, 55, pastor of the Aleitheia Bible Church, was convicted in March of eight counts of conspiracy to commit child abuse for instructing church members to punish children by hitting them on the bare buttocks with wooden dowels to teach them to behave correctly, in keeping with the church’s literal interpretation of the Bible.

The motion to dismiss the charges alleged Caminiti had been deprived of his constitutional right to religious freedom.

Circuit Judge Maryann Sumi found that Caminiti had “a sincerely held religious belief” as a Christian fundamentalist that requires using a rod to discipline children beginning at a young age. But Sumi said Caminiti failed to show the state’s child abuse statute “places a burden on his sincerely held religious belief.”

“Scripture doesn’t specify how and when the rod should be used,” Sumi said, adding that Caminiti also was willing to modify the church’s practices to comply with the law….

If Caminiti had simply preached the propriety of such behavior in the abstract, I think such a conviction would likely be unconstitutional under the Free Speech Clause without regard to any special religious freedom claim, given Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), even if the hitting of the children would indeed be a crime. (It probably would be; note that, according to the sheriff’s department, “the dowels were described as being 12-18 inches long with a diameter about the size of a quarter.”)

Teaching that it’s proper or even obligatory to commit a crime is generally constitutionally protected unless it’s intended to and likely to yield imminent crime, which is to say crime some time in the immediate future, likely within a few hours or at most days, and not “at some indefinite future time.” That’s why it’s not a crime to teach that it’s proper or even religiously obligatory to use marijuana, or to refuse to register for the draft, or to engage in jihad. And it sounds from news accounts that the minister’s teachings were not intended to yield such imminent conduct, but instead were meant as guidance for “some indefinite future time.”

But if Caminiti had specifically counseled particular parents about what to do with their particular children in particular contexts — “minister, my child did this-as-such; should I beat him tonight for it?” — this might qualify as either incitement of imminent criminal conduct, or as constitutionally unprotected solicitation of crime (see United States v. Williams (2008)). The line between solicitation, which is unprotected even when it calls for action in the indefinite future (e.g., “please send me some child pornography, whenever you happen to have some”) and incitement, which is protected unless it calls for imminent action, is unclear. Urging people that some general course of action is morally obligatory, without reference to a particular proposed action dealing with a particular person or a particular item, would be a classic example of material covered under Brandenburg (general advocacy) rather than Williams (solicitation). But the more specific the advocacy, the more likely it is to be seen as unprotected solicitation (or as unprotected incitement, if it’s advocacy of what the parent is to do right away).

Note that Wisconsin courts have interpreted the Wisconsin Constitution to require, in some situations, religious exemptions from generally applicable laws, under the Sherbert/Yoder regime. But it’s not clear to me that, even so, the best argument for the minister is a religious freedom argument. The protection offered by free speech law in such cases should, I think, be rather greater than the protect offered by religious exemptions law. And if the pastor’s speech is unprotected by the Free Speech Clause, I doubt that courts would find it protected even under the state constitution’s religious freedom guarantee, even using the Sherbert/Yoder test.

If anyone can point me to any reasoned opinions on the judge’s part in this case — or to more facts on the subject — I’d love to see them. All I could find myself online is the docket sheet, which doesn’t have the documents. Note that “Caminiti was not charged with having committed any abuse himself.” Thanks to Prof. Howard Friedman (Religion Clause) for the pointer.

May 11, 2012

EPIC Loses FOIA Appeal Against NSA

Today the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit decided Electronic Information Privacy Center v. National Security Agency. Here’s the summary from the beginning of Judge Brown’s opinion for the court.

Plaintiff-appellant Electronic Privacy Information Center (“EPIC”) filed a Freedom of

Information Act (“FOIA”) request with the National Security Agency (“NSA”) seeking disclosure of any communications between NSA and Google, Inc regarding encryption and cyber security. NSA issued a Glomar response pursuant to FOIA Exemption 3, indicating that it could neither confirm nor deny the existence of any responsive records. EPIC challenged NSA’s Glomar response in the district court, and the parties cross-moved for summary judgment. The district court entered judgment for NSA, and EPIC appealed. We affirm.

UPDATE: BLT reports on the case here.

May 10, 2012

Iranian Cartoonist Sentenced to 25 Lashes for Cartoon of Member of Parliament

The Guardian (UK) reports (see also MSNBC Cartoon Blog and other sources):

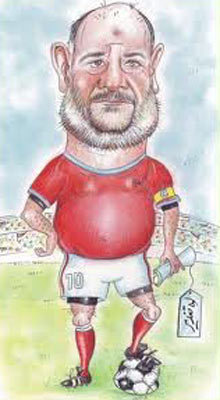

Mahmoud Shokraye was put on trial after an Iranian MP, Ahmad Lotfi Ashtiani, took offence to a cartoon he drew of the parliamentarian in Nameye Amir, a city newspaper in Arak, the capital of Iran’s central province of Markazi….

In the cartoon, Ashtiani is depicted in a football stadium, dressed as a footballer, with a congratulatory letter in one hand and his foot resting on the ball. The MP’s forehead has a dark mark, said to be the sign of a pious Shia Muslim, caused (supposedly) by frequent prostration during prayer. The cartoon contains little exaggeration and Ashtiani’s forehead has a prayer mark in reality.

Shokraye drew Ashtiani following widespread criticism in Iranian society towards a number of politicians who have been accused of interfering in the country’s sports….

Speaking to an Iranian journalist, Esmail Kowsari, a member of the parliamentary committee on national security, defended the sentence: “[A cartoonist] should be persecuted if the cartoon is not ordinary and ridicules someone … Any crime has its own punishment, including lashing, imprisonment or being fined.”

Note that “persecuted” might (or might not) be a mistranslation. Thanks to Opher Banarie for the pointer.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers