Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 2552

May 20, 2012

Woody Allen had already registered dot-insecure

Two and a half years after former Director of National Intelligence Mike McConnell called for a “dot-secure” network, a Silicon Valley startup with $9.6 million in funding has announced plans to launch one. From the description, this isn’t intended to be a wholly secure network, since that’s a promise no one can fulfill. Instead, it’s intended to link companies that take security seriously. At a minimum, the shared standards and security consciousness should allow much better forensics and audits of network behavior, even when the behavior crosses organizational and technical firewalls. In fact, I assume the $9.6 million will be spent mainly on rule-writing and rule-enforcement.

Two and a half years after former Director of National Intelligence Mike McConnell called for a “dot-secure” network, a Silicon Valley startup with $9.6 million in funding has announced plans to launch one. From the description, this isn’t intended to be a wholly secure network, since that’s a promise no one can fulfill. Instead, it’s intended to link companies that take security seriously. At a minimum, the shared standards and security consciousness should allow much better forensics and audits of network behavior, even when the behavior crosses organizational and technical firewalls. In fact, I assume the $9.6 million will be spent mainly on rule-writing and rule-enforcement.

If ever there were a startup that lawyers and accountants could have dreamed up, this is it. I hope that doesn’t guarantee its failure.

Darwin shudders

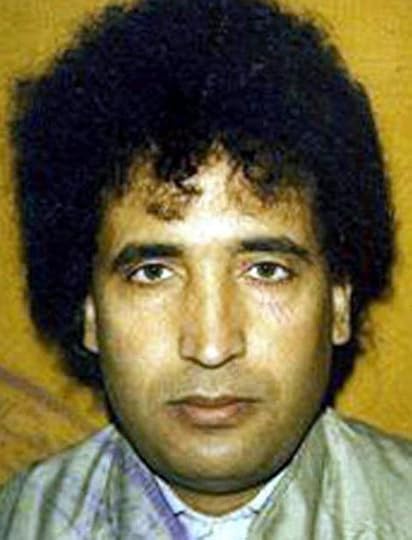

The one man convicted of the Lockerbie bombing has died, three years after being released by the Scottish Nationalist government for what was advertised as his last few weeks of life.

Evidently determined never to apologize, SNP leader Alex Salmond defended that release today, saying that “regardless of people’s views they can have complete confidence that it was taken on the basis of the due process of Scots Law.”

The application of Scots law instead of British law is the result of what the Scots call devolution. A remarkably apt name that, when you think about it.

Sex, Consent, Pushiness, and Acquiescence

An interesting recent sex crime case, In re Tiemann (Mich. Ct. App. May 8, 2012). Because the parties were underage (defendant was 15 and HS was 14), consent was not a defense to the underlying crime, but it proved to be important to deciding whether the defendant could avoid having to register as a sex offender. An excerpt:

On February 20, 2010, Tiemann went to HS’s home at her invitation. They went to the guest house and proceeded to “make out.” HS said that after Tiemann removed her shirt, she protested when he tried to remove her bra and told him “she really didn’t want to do this.” Tiemann allegedly told her he had done this before and not to worry. HS said that ultimately, Tiemann removed all her cloths, digitally penetrated her, and performed cunnilingus on her. She said she told him she “didn’t want to” while he was digitally penetrating her but then “gave in because she knew he wouldn’t stop.” She claimed that during the subsequent sexual acts, she told him to stop, and he did, but then started again. HS said that Tiemann stopped completely when she told him to stop a second time. After that, they dressed, lay down on the couch together, and fell asleep.

Tiemann admitted that HS said once that they were moving too fast, but then she said that she would be okay. He claimed that she pulled him back on three occasions when he asked if she wanted him to leave. He also acknowledged that HS said she wanted to stop while he was digitally penetrating her, and he offered to leave. Further, he acknowledged that she sat up and that he laid her back down four times. He claimed that he was not forcing her during penile-vaginal sex. Further, he acknowledged understanding that she wanted to stop when she expressed that she was uncomfortable. When asked if he should have stopped, Tiemann said “Yeah, lots of times.” Finally, Tiemann stated that he felt he was being pushy when he told her to relax and be comfortable with it and that eventually it seemed that she was comfortable because it “felt like she just gave in.” However, he said he “forc[ed] it on her a couple of times” and that he knew it was wrong….

[T]he parties reached a plea agreement whereby Tiemann was to plead no contest to one [Criminal Sexual Conduct] III [statutory rape] count and the other charges [alleging force or coercion] would be dismissed. After reviewing two case report summaries of interviews of the victim and Tiemann, the trial court accepted the plea. The trial court found a factual basis for a determination that Tiemann had intercourse with the victim who was between the age of 13 and 16 (there was no mention of force or coercion).

Apparently, an initial order of adjudication indicated that Tiemann was convicted based on force or coercion. However, a corrected order of adjudication specifies that the victim’s age was the basis for the conviction….

An amendment to [the Sexual Offender Registration Act] subsequently took effect and provided that for cases pending on July 1, 2011, a juvenile could be excused from registration under the SORA under certain circumstances if he could establish consent. The trial court therefore held a trial on the issue of consent. At the trial, various witnesses were called, and HS read a statement into the record giving a more detailed account of what transpired on the night in question. In this account, she indicated that she may have acquiesced “so that he wouldn’t be so mean” but gave further indications that the sex was not consensual. Ultimately, the trial court found that Tiemann was not exempt from SORA registration requirements.

Note that to get an exemption from the registration requirement, the defendant must prove consent by a preponderance of the evidence. In a typical criminal case alleging nonconsensual sex, the prosecution must prove absence of consent beyond a reasonable doubt. Still, the common question in these cases is what counts as “consent.”

An Interesting Defamation Case

I just ran across an interesting case, Memphis Pub. Co. v. Nichols (Tenn. 1978). The Memphis Press-Scimitar published the following article that mentioned Mrs. Ruth Ann Nichols:

WOMAN HURT BY GUNSHOT

Mrs. Ruth A. Nichols, 164 Eastview, was treated at St. Joseph Hospital for a bullet wound in her arm after a shooting at her home, police said.

A 40-year-old woman was held by police in connection with the shooting with a .22 rifle. Police said a shot was also fired at the suspect’s husband.

Officers said the incident took place Thursday night after the suspect arrived at the Nichols home and found her husband there with Mrs. Nichols.

Witnesses said the suspect first fired a shot at her husband and then at Mrs. Nichols, striking her in the arm, police reported.

No charges had been placed.

Please think briefly about the story, and then click on the link before to learn what the court decided.

Did you read the story as suggesting that the shooter found her husband in a compromising position with Mrs. Nichols — perhaps having sex, or having had sex, or being just about to have sex? That’s apparently how many readers read the story as well.

But it turns out that, though each statement in the story was literally true, Mrs. Nichols was at the Nichols home together with the shooter’s husband, Mr. Nichols, and two neighbors. They were apparently all sitting in the living room, talking.

The court concluded that the story could be libelous — assuming negligence was shown on the newspaper’s part — because, even though the statements were literally true, they carried a strong implication (that the husband and Mrs. Nichols were together by themselves in a compromising position) that was false:

In our opinion, the defendant’s reliance on the truth of the facts stated in the article in question is misplaced. The proper question is whether the meaning reasonably conveyed by the published words is defamatory, “whether the libel as published would have a different effect on the mind of the reader from that which the pleaded truth would have produced.” The publication of the complete facts could not conceivably have led the reader to conclude that Mrs. Nichols and Mr. Newton had an adulterous relationship. The published statement, therefore, so distorted the truth as to make the entire article false and defamatory. It is no defense whatever that individual statements within the article were literally true. Truth is available as an absolute defense only when the defamatory meaning conveyed by the words is true.

Such “defamation by half-truth” decisions are rare. All statements, after all, omit something, and one can always argue that the full story would convey a somewhat different message from the partial story. Usually that’s not enough to turn literal truth into libel. But in some situations, where the statement does carry a very strong implication that turns out to be false, a libel claim can indeed be brought even when the statement is literally true.

Another classic example — though just a hypothetical and not a real case — involves the first mate who, upset by his teetotaling captain, writes in the ship’s log,

Captain sober today.

The statement may be literally accurate (the captain was sober today, as on all days) but it carries a very strong implication that turns out to be false (that today was unusual in this respect).

H.P. Grice’s work on conversational implicatures, by the way, relates to this.

Is Marriage a Legal Contract?

A reader asks:

In a discussion thread on another blog, I hazarded an observation that marriage is NOT a contract as typically defined at law. I based this on my view that marriage does not contain elements that a contract must contain, such as a definition of goods and services offered in exchange for consideration.

My interlocutor held that marriage does, indeed, contain all the necessary elements of a contract, including defined exchange and “payment” for it.

I have researched this question online, but can find no satisfactory answer. Black’s Law (2nd ed.) seems to treat marriage as a legal status, but not a contract. At the same time, there’s no lack of other commentaries which pointedly describe marriage as a contractual relationship.

So: Might you and your conspirators shed some light on the question by posting your thoughts: Is marriage — technically — a legal contract?

I thought I’d response to this on-blog because it illustrates a considerably broader point: In law, as in life, concepts like “contract” aren’t unitary things, so that either something is a contract and has all the properties of a contract or something isn’t a contract. There are different kinds of contract, with different qualities, and different possible definitions for the term “contract.”

To begin with, “contract” is a quite broad concept. I don’t want to try to give a thorough definition here, but suffice it to say that an exchange of promises might well be a contract even if the promises don’t involve money, goods, or even services. Thus, for instance, “Each of us promises not to be anyone else’s bridge partner” can be a contract; it’s an exchange of promises not to engage in certain conduct. (Note that the contract doesn’t promise that I’ll be your bridge partner, just that I won’t be anyone else’s.) Substitute something else for “bridge,” and you’ll have one aspect of a marriage contract.

But beyond this, it turns out that a marriage contract is a contract — it’s an exchange of promises, it has effect because of consent of the parties, and it after all is called a marriage “contract.” But it also has many consequences that a normal contract doesn’t have: Not so long ago, it turned otherwise criminal sexual conduct (fornication) into legal conduct. Even today, it has that effect with marriages where one party is too young to consent to sex but old enough to consent to marriage (usually with the parents’ consent). It makes the parties’ children legitimate, which used to have very important legal effects and still has some legal effects. It gives the parties the right to refuse to testify against each other in court. If one party is not a citizen, it gives the party a relatively easy path to citizenship. The list could go on.

It also lacks some of the properties of a normal contract. It can be severed pursuant to divorce laws without the opportunity to sue for damages for breach of contract. It is not governed by the Contracts Clause of the Constitution, so that newly enacted divorce laws could impair the obligation of existing contracts of marriage (see the Dartmouth College Case (1819)).

So marriage is a contract, and has long been described as a contract, but it’s a very peculiar kind of contract that has its own special legal rules. To ask whether marriage is “technically” a contract doesn’t make much sense, because it presupposes a single unique meaning for the term “contract.” If by contract you mean “a contract as typically defined at law,” which is to say a contract that has most of the legal consequences that a typical contract has, then the answer is “largely not,” because marriage contracts have such specialized legal consequences. If by contract you mean “something the law has typically labeled a contract,” the answer is “probably yes,” simply because “marriage contract” has long been a common term. If by contract you mean “a mutual agreement that the law treats as binding as a consequence of the parties’ having agreed to it,” then the answer is “yes.”

So, as I said, there are different kinds of contract, with different qualities, and different possible definitions for the term “contract.” In math, you can ask, “is a number even, or is it odd?” In law, asking “is X a contract?” will often yield the response, “in what sense, and for what purposes?”

The Irrelevant Myth of the “Constitution-in-Exile Movement”

As a follow up to my previous post, I wish to comment briefly on Jeff Rosen’s revival of Cass Sunstein and his invention: the Constitution-in-Exile Movement that seeks a return to the pre-1937 Supreme Court doctrine. As my previous post makes clear, the challenge to the Affordable Care Act is in no way based on the return to anything. It is based solely on refusal to acknowledge an unprecedented, uncabined, unnecessary and dangerous congressional power to compel all Americans to enter into contracts with private companies.

In addition to being irrelevant, however, the so-called Constitution-in-Exile Movement is also a myth. In 2005, I engaged in a week-long debate with Cass Sunstein about this on the Legal Affairs’ Debate Club. You can read the whole thing here. (For others who questioned or rejected this Constitution-in-Exile meme see posts by David Bernstein, Orin Kerr, Stephen Bainbridge, and a recent related piece by Adam White. You can read the whole Volokh chain here, though it includes a few posts that are not directly on point.) But here I will confine myself to reproducing my initial reply to Cass’s opening post:

Let me begin this week-long exchange, Cass, with a denial. There is no “Constitution in Exile” movement, either literally or figuratively. As for literally, I and others had not even heard the expression, plucked from an obscure book review by Judge Douglas Ginsburg, until well after folks like you and Jeff Rosen had started using it to describe their intellectual opponents. And as author of the 2004 book, Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty, I would seem to be at the heart of whatever movement supposedly exists.

For obscure reasons that we may perhaps glean from this week’s debate, the phrase “Constitution in Exile” viscerally appeals to critics of scholars and judges who, like me, favor interpreting the Constitution as amended according to its original meaning. Maybe it makes these “originalists” sound kooky or marginal or radical—like Russian nobility with their shadow governments futilely planning their return to power from the irrelevant comfort of London tea rooms. Maybe this rhetorical move has something to do with undermining future nominees to the Supreme Court who may be originalists.

Cass, you say the “Constitution in Exile” refers “to the Constitution of around 1930, before Roosevelt’s New Deal.” The problem here is that I know of no one (including Judge Ginsburg), whether originalist or not, who entirely agrees with the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution in 1930 or at some earlier point. To take but one example, many originalists like Justice Scalia entirely reject the Due Process Clause jurisprudence of the pre-1930s Supreme Court. In contrast, many progressive law professors today think that the Supreme Court was correct in 1923 when it used the Due Process Clause to protect the right of parents to send their children to schools that teach foreign languages and in 1925 when it used the Due Process Clause to protect the right of parents to send their children to private schools. Both of these cases remain good law today. From an originalist perspective, I agree with today’s progressives and disagree with Justice Scalia, though I think these cases should have been grounded on the original meaning of the Privileges or Immunities Clause rather than on Due Process. (So even here I contend that the Supreme Court was wrong in the 1920s.) Indeed, I could name many other important examples of disagreements by today’s originalists with the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court before 1937.

And a portion of my final post:

Cass, thank you for the passion and clarity that your most recent remarks have brought to our debate. As you say, we have covered a lot of ground, and for the most part, I think we’ve succeeded in bringing more light than heat to the vitally important issues we’ve discussed. Let me step back a moment before addressing directly the most recent points you’ve made. . . .

Our conversation has demonstrated that the effect of talking about a “Constitution in Exile” is to obscure rather than illuminate the terms of this debate. I fear that this rhetorical shift aims to evade genuine intellectual and political discourse about the merits of originalist jurisprudence by raising a red herring about a fictitious and ill-defined movement or conspiracy to restore the constitutional doctrines of 1930 or 1920. Our interchange this week has been productive, in part, because it has refocused the discussion on the real choice before us: Should judges follow the text of the written Constitution in light of evidence about its original public meaning or should they ignore that meaning to translate their fundamental values or beliefs about how government should be arranged into constitutional law?

Cass, you and I agree on much, but we disagree about the answer to this question. You believe that the importance of reaching certain results—you listed them today—justifies the judicial nullification or updating of whole provisions of the Constitution. (If “updating” does not fairly describe a nonoriginalist approach, then I don’t know what does.) I believe that judges who stick to the original meaning should be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. . . .

Over the course of this week, Legal Affairs readers have been provided a preview of a great debate that lies ahead. As my final contribution to our discussion, let me express my hopes and aspirations for that debate. I hope that the political process upon which we rely to select Supreme Court Justices will not be thwarted by name calling, conspiracy mongering, or false claims about bad motives on either side. I hope that judicial nominees will not be presented with a laundry list of results intended to serve as a litmus test for ideological acceptability. I hope they will be asked instead about their judicial philosophy and their commitment to the rule of law. I hope that those who participate in this great debate will frame their arguments in language that clarifies the issues rather than obscures them. And I most fervently hope that the debate will not be conducted in a topsy-turvy newspeak that charges originalists with being insufficiently conservative and equates adhering to the rule of law supplied by the Constitution of the United States with activism or radicalism!

Rosen writes as if there had been no response to his and Sunstein’s previous attempt to turn a principled commitment to original meaning into an insidious conspiracy to return to pre-1937 Supreme Court doctrine. But, as I already said, even if he is right about the conspiracy he describes, the challenge to the Affordable Care Act has absolutely nothing to do with “original meaning” and everything to do with extending the power of Congress beyond existing Supreme Court doctrine.

And Jeff Rosen is too smart a guy not to know this.

Judicial Minimalism and the Individual Mandate

If the Supreme Court invalidates the individual insurance mandate, it need not call into question any other law that has ever been passed in the history of the United States. Why? Because the Congress has never before exercised its Commerce Power to impose a requirement on the American people to enter into a contract with a private company, upon pain of a penalty payable to the IRS. All the Court need do is confine Congress to the powers it has always exercised, including all the powers it exercised since the New Deal which also includes all the powers that were upheld by the Warren Court. A decision to invalidate would be the most minimal of minimalist decisions as it would apply to one law, and only one law.

True, the Affordable Care Act is a major piece of legislation. Indeed it is an audaciously ambitious piece of social engineering designed to fundamentally transform a sixth of the national economy. But there is no doctrine that limits the power of judicial review to small symbolic pieces of legislation like the Gun Free School Zone Act. Nor do any four justices have a fillubuster power to prevent a majority from finding a portion of even a major piece of legislation unconstitutional. To assert that “conservative” justices may not invalidate legislation sponsored by a “progressive” President, or a Democratic Congress (albeit a prior Democratic Congress) would be to inject a wholly political consideration into what is supposed to be the impartial exercise of judicial judgment.

It would be like saying that, in Game Seven of the World Series, a National league umpire should shrink the strike zone when the American league players are at bat — if the game is close, and the American league team is behind. Just to be perceived as “fair.”

Ever since the oral argument, progressive commentators have been engaged in a series of rearguard litigation tactics designed to intimidate or threaten the Court with dire political consequences should it fail to uphold legislation that they strongly favor. The most recent, and most blatant, of these efforts is by my friend Jeff Rosen. Rosen always likes to instruct conservatives about how to be good judicial conservative, lest they be accused of being activist by folks like Jeff Rosen. In his recent column, he throws down his gauntlet to Chief Justice Roberts:

This, then, is John Roberts’s moment of truth: In addition to deciding what kind of chief justice he wants to be, he has to decide what kind of legal conservatism he wants to embrace. Of course, if the Roberts Court strikes down health care reform by a 5-4 vote, then the chief justice’s stated goal of presiding over a less divisive Court will be viewed as an irredeemable failure. But, by voting to strike down Obamacare, Roberts would also be abandoning the association of legal conservatism with restraint—and resurrecting the pre–New Deal era of economic judicial activism with a vengeance. This is the era that Judge Brown and Randy Barnett yearn to revive: a time when crusading judges struck down progressive economic regulations in the name of hotly conservative economic doctrines that a majority of the country didn’t favor. We’ve seen this script play out before, and it didn’t end well for the Court.

The justices know what many readers of the New Republic do not: Nowhere did the challengers to the ACA ever base their claim on “conservative economic doctrines.” No. Where. Our case has always been simply that this claim of federal power exceeds any that has ever previously been authorized by the Supreme Court, and that it is an uncabined, unnecessary and dangerous power to recognize for the first time.

Still, this is very clever advocacy of a radical result under the guise of judicial conservatism. For, if the Court were to take Rosen’s advice, the Roberts Court will have adopted the radical position that law professors have long desired, but that even the New Deal Court never announced: Unless the Congress violates an express prohibition in the Constitution, there are no judicially-enforceable limits on the Commerce Power of Congress. Indeed, we know from legal historian Barry Cushman that some New Deal justices privately considered and rejected adopting this approach in Wickard v. Filburn.

And, as we all know, the Supreme Court expressly rejected this proposition in Lopez v. United States, which these same law professors bitterly derided as “conservative judicial activism” when they were decided. Indeed, back in 2000, Rosen wrote this of the New Federalism of the Rehnquist Court:

The most startling quality of today’s conservative judicial activists is not only the unselfconscious hypocrisy with which they are abandoning the judicial philosophies on which they have staked their careers. It is also their overconfidence and lack of humility — as they blithely substitute their own policy judgment for those of the Congress, the president, . . . and the states.

And, in his 2005 New York Times Magazine story promoting the Constitution-in-Exile meme, he wrote this of Lopez:

By 1995, the Constitution in Exile movement had reached what appeared to be a turning point. The Republicans had recently taken over both houses of Congress after pledging, in their Contract With America, to rein in the federal government. And the Supreme Court, by rediscovering limits on Congress’s power in Lopez, seemed to be answering the call.

Rosen’s claim that, unless the conservative justices uphold this new and dangerous power, they are betraying their conservativism is the height of presumptuousness. If accepted, Rosen’s claim that five justices cannot legitimately invalidate a “big” law unless some of other four go along would create a new, unprecedented, and strictly politically-based filibuster power by a minority of justices. To equate the invalidation of this deeply unpopular law with the adoption of a economic doctrines “that a majority of the country didn’t favor” is to turn constitutional history on its head. If the justices are perceived by the public as yielding to this overtly political media onslaught, it would fatally undermine the independence of the Supreme Court.

In the end, though, I confess that I almost admire Jeff Rosen’s chutzpah.

Google Self-Driving Car Test-Ride

Randal O’Toole (Cato@Liberty) reports on his experience. The technology sounds very cool, and I take it that so far it has been pretty accident-free. Of course, my first reaction to hearing about this was “how dangerous!,” but it’s not like this is a new technology trying to replace an absolutely safe current technology — and it may well be that such a car is already safer than the average real driver, or will soon be safer. It will be very interesting to see how this develops (and of course to explore the legal dimensions).

Thanks to Opher Banarie for the pointer. Disclosure: I have occasionally worked on Google legal projects, and was recently commissioned by Google to write a white paper.

May 18, 2012

The PPACA in Wonderland

That’s the title of a new article by Gary Lawson and me, in Boston University’s American Journal of Law and Medicine, in a symposium issue on the PPACA. Except that unlike Alice, the PPACA neither becomes a Queen, nor wakes up to return to reality. Written before the oral argument, the article provides an overview of some of the main constitutional and linguistic topics at play in the PPACA cases.

Tax Exemption Law and Camp Predominantly Used by Muslims

An interesting case in Michigan, in which a Tax Tribunal decision was reversed by Camp Retreats Foundation, Inc. v. Township of Marathon (Mich. Ct. App. May 15, 2012). The question is whether a camp was exempt from property taxes; the camp was rentable by the general public (and sometimes rented by the public), but it was mostly used by Muslim groups, “because (i) the facilities were constructed so that separate ‘villages’ are available to boys and girls such that a ‘conducive environment’ is created to ‘manage the two genders,’ and (ii) word of mouth of the availability of the subject facilities was generated through Muslim lines of communication.” The main user was a summer camp that had a pretty clearly Muslim focus, with a good deal of time devoted to prayer and study of the Koran, and with the rules providing that:

All participants must observe Islamic laws, which includes but is not limited to, good moral standards, maintaining proper hijab, keeping away from backbiting and gossiping, presenting oneself with respect and dignity, maintaining decency with appropriate clothing and more. Brothers and sisters must show respect for each other. Any misconduct may lead to expulsion from the camp if deemed necessary.

Under Michigan law, a property-owning organization is treated as a charitable organization and can therefore claim tax-exempt status for its property when it is organized “for the benefit of an indefinite number of persons, either by bringing their minds or hearts under the influence of education or religion, by relieving their bodies from disease, suffering or constraint, by assisting them to establish themselves for life, or by erecting or maintaining public buildings or works or otherwise lessening the burdens of government” and at the same time “does not offer its charity on a discriminatory basis by choosing who, among the group it purports to serve, deserves the services.” The Township argued that Camp Retreats didn’t qualify, because, in relevant part,

1) it discriminates in determining who can use the subject property, 2) participation in the Tawheed Summer Camp, sponsored by Petitioner’s parent organization, and the primary user of the subject facilities, is conditioned specifically on observance of Islamic laws and management, [and] 3) Petitioner has not established by testimony or exhibits that Petitioner’s purpose is to “bring people’s minds or hearts under the influence of education or religion,” nor do they “relieve people’s bodies from disease, suffering or constraint[.]“

The Tax Tribunal concluded that Camp Retreats was indeed not a charity, because it was “is chiefly organized for recreational purposes rather than for charitable purposes.” The Tribunal’s opinion didn’t discuss the “bringing … minds or hearts under the influence of … religion” part of the test, and relied on the fact that the articles of incorporation for the camp focused on recreation rather than religion.

The Michigan Court of Appeals reversed, reasoning that the tax tribunal should have looked at how the property was actually used rather than focusing on what the articles of incorporation said, and that the actual use of the property was indeed charitable under Michigan law:

In reaching [its] conclusions, the Tribunal disregarded its own factual determination that the facility was chiefly used as camp for children and families of the Muslim faith, and in so doing misapplied the law. We find that the property fulfills the requirements of a charity because its primary use focuses on “bring[ing] people’s minds or hearts under the influence of … religion,” and it offers this charity on a nondiscriminatory basis.

As the Tax Tribunal recognized in its findings of fact, various groups sharing an identity with Islam constitute the principal users of the camp facility: “Most groups renting the subject facilities were of the Islamic faith because the facilities are constructed to separate and ‘manage’ the two genders and because the availability of the facilities was generated through word of mouth communications among Muslims.” Indeed, unrebutted evidence established that Camp Retreats bought the land specifically intending to create a camp for use by people of the Islamic faith, and has created a facility particularly suitable for that use….

The relevant inquiry is whether the property “benefit[s] … an indefinite number of persons, either by bringing their minds or hearts under the influence of … religion.” This requires a searching examination of the actual nature of the activities conducted on the land, with an eye toward evaluating “the overall nature of the institution, as opposed to its specific activities.” … Camp Retreats’ central focus is on providing the Islamic community with religious experience in a camp environment. Marathon Township admits as much; its brief in this Court asserts: “Apart from a few exceptions, all uses share the common thread of being Islamic in nature. Participants either have a personal connection to the two directors, who are both Muslim, or are tied to Muslim groups or activities.”

Given that the evidence overwhelmingly supports the religious nature of Tawheed’s activities on the property, we are hard-pressed to distinguish this case from Gull Lake Bible Conference Ass’n v. Ross Twp, 351 Mich. 269; 88 NW2d 264 (1958). In that case, the nonprofit plaintiff’s stated purpose was “[t]o promote and conduct gatherings at all seasons of the year for the study of the Bible and for inspirational and evangelistic addresses.” The plaintiff owned a “tabernacle and youth chapel” located on land exempt from ad valorem taxation. In addition, the plaintiff owned land “in close proximity” to the tabernacle and youth chapel that included a lake, “a fellowship center building, picnic area, boat docks, bath house, bathing beach, playground, and horseshoe and badminton courts.” The Supreme Court held that the additional land qualified for a charitable property tax exemption because its use “promote[d]” gathering for the study of the Bible. The Supreme Court adopted the following elaboration of the plaintiff’s charitable function:

Looking at the situation in the light of this latter purpose, it may be logically concluded that in order to obtain satisfactory attendance to its conference, plaintiff found it advisable and necessary to provide those attending with living accommodations, recreational facilities and all of the other services offered by plaintiff and made possible through the use and occupancy of the land in question by plaintiff in the manner in which they do use and occupy such land.

As in Gull Lake, the Tawheed camp’s recreational opportunities further religious purposes. Islamic worship and observance are inextricably interwoven into the camp’s daily programs. An internet description of the property introduced by Marathon Township portrayed Tawheed camps as providing “a full residence summer and winter camp experience in a beautiful setting within an Islamic environment.” Thus, the camp’s overall structure operates as a “gift” for the benefit of an indefinite number of persons, by bringing their minds or hearts under the influence of religion.

I’m not an expert on the law of charitable tax exemptions, but the Michigan Court of Appeals decision seems quite right to me.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers