Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 23

October 3, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 3, 1990

10/3/1990: Justice David Souter takes the oath.

Justice David Souter

Justice David SouterThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 3, 1990 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Friday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Friday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

October 2, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Fifth Circuit Will Rehear Alien Enemies Act Case En Banc

[It will review a panel decision holding that Trump could not invoke this sweeping wartime authority by claiming illegal migration and drug smuggling qualify as an "invasion."]

AI-generated image.

AI-generated image. Earlier this week the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit decided to grant an en banc rehearing in W.M.M. v. Trump. The panel decision in that case ruled that Trump's invocation of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 was illegal, because illegal migration and drug trafficking and other activities of the Venezuelan drug gang Tren de Aragua do not qualify as a war, "invasion," or "predatory incursion." The AEA can only be used to detain and deport immigrants when one of these extraordinary conditions, or a threat thereof, exists.The case will now be reheard by all 17 active Fifth Circuit judges.

In an amicus brief I coauthored in the case on behalf of the Brennan Center, the Cato Institute, and others, we argue that "invasion" and "predatory incursion" require a military attack, and that courts should not defer to presidential assertions that these extraordinary conditions exist. As James Madison put it in addressing this issue, "invasion is an operation of war."

Otherwise, the AEA and the Constitution's grant of extraordinary emergency powers when an "invasion" exists could be invoked by the president anytime he wants, thereby creating grave dangers to civil liberties and to the separation of powers. For example, the Constitution states that, in the event of "invasion," the federal government can suspend the writ of habeas corpus, thereby authorizing indefinite detention without due process - not only of recent immigrants, but also US citizens.

Prominent conservative Judge Andrew Oldham wrote a lengthy dissent to the panel decision, arguing that the definition of "invasion" and other terms in the AEA is left to the unreviewable discretion of the executive. I outlined some key flaws in his argument here. In a solo concurring opinion in United States v. Abbott, a previous Fifth Circuit en banc case, Judge James Ho, another well-known conservative, similarly argued the definition of "invasion" is an unreviewable "political question," left to the determination of the executive, and also of state governments (under Ho's approach, they too can claim and "invasion" exists whenever there is illegal migration or drug smuggling). I criticized Judge Ho's reasoning here.

Both Ho's approach and Oldham's would give the president (and, in Ho's case, also state governments) unlimited authority to declare an "invasion" at any time, and thereby wield sweeping authority to undermine civil liberties and the separation of powers. The federal government could use this power to detain and deport even legal immigrants, and to suspend the writ of habeas corpus (including for US citizens). Under the Constitution, in the event of "invasion" state governments can "engage in war" even without congressional authorization. I wrote about the dangers of that in greater detail here, as well as in the amicus brief.

Such vast unilateral authority goes against the text and original meaning of both the Constitution and the Alien Enemies Act. British violations of the writ of habeas corpus were one of the main grievances that led to the American Revolution, and the Founding Fathers did not intend to give the president the power to replicate those abuses anytime he might want.

I will have more to say about these issues as the AEA litigation continues in this case and in other cases currently before various federal courts. We will likely file an updated version of our amicus brief before the en banc Fifth Circuit.

The post Fifth Circuit Will Rehear Alien Enemies Act Case En Banc appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Marking 50th Anniversary of Our Arrival in the U.S., with a Free-Speech-Related Matter

On Oct. 8, 1975, my parents brought my brother Sasha and me to the U.S. As one might gather, Oct. 8 (and June 13, the anniversary of the day we left the Soviet Union earlier that year) are the most significant holidays on our family calendar.

I'm therefore particularly delighted that, by sheer coincidence, I'll be doing something related to my research on free speech on the 50th anniversary of that day: I was asked to testify at a Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation hearing on free speech and government pressure on social media platforms. Should be an interesting program, which I'm honored to be a part of.

The post Marking 50th Anniversary of Our Arrival in the U.S., with a Free-Speech-Related Matter appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] The Hatchet-Wielding-Hitchhiking-Murderer-Unsuccessful-Intellectual-Property-Litigant

From McGillvary v. Hartley, decided Tuesday by Judge Ashley Royal (M.D. Ga.):

Pro se Plaintiff Caleb McGillvary is currently serving a 57-year sentence for first-degree murder. In February, 2013, McGillvary rose to internet fame as the "hatchet wielding hitchhiker" after he gave interviews to a local Fresno, California KMPH Fox News TV reporter in which McGillvary described "smash, smash, suh-mash[ing]" Jett Simmons McBride three times over the head with a hatchet after McBride crashed his car into a group of pedestrians and attacked bystanders at the scene ("KMPH Clip"). Fresno authorities concluded that Plaintiff used justifiable force in protection of the bystanders and cleared him of any wrongdoing.

Three months later, after gaining media notoriety for viral news interviews and media appearances, including an interview on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, Plaintiff was arrested for and ultimately convicted of murdering Joseph Galfy, Jr., a New Jersey attorney. Plaintiff's arrest was unrelated to the hatchet incident.

On January 10, 2023, Netflix released a documentary about McGillvary entitled The Hatchet Wielding Hitchhiker that described his background; interviewed those around him during his rise to fame; and detailed his subsequent murder conviction (the "Documentary"). Five days before the Documentary was released, on January 5, 2023, Defendants created and published an episode on their YouTube channel, "The Behavior Panel," wherein they analyzed the KMPH Clip and made statements about Plaintiff based on their assessment of his body language and behavior (the "YouTube Video"). This suit arises out of the comments made in the YouTube Video….

There's a lot more in the opinion, but here's a short excerpt of the legal analysis:

Defamation …

Plaintiff alleges Defendants made 28 "slanderous and libelous statements with reckless disregard for and/or knowledge of their falsity, with actual malice intending the harm that would result therefrom." Defendants' allegedly defamatory statements include telling viewers they will analyze Plaintiff's body language and behavior from the News Clip to determine whether Plaintiff is a "sociopath" or "psychopath"; commenting on Plaintiff's "odd behavior for someone who's killed somebody in the last three hours"; questioning whether Plaintiff has a "personality disorder" and lacks language and relationship skills; questioning the relationship between Plaintiff and McBride, the driver of the car, "be it a drug deal, be it a prostitution situation, whatever was happening there"; commenting that Plaintiff was trying to be a "hero"; calling Plaintiff a "drifter" and a "vigilante"; suggesting because Plaintiff stated in the News Clip he was from "Dogtown," Plaintiff was "kind of suggesting that he's a mutt out of the back streets … a bit of a mongrel from the backstreets"; opining that Plaintiff "probably has done some things. We know he gets convicted of murder later …. I don't think what we're seeing here is the Johnny Appleseed of goodness running around the country beating up bad guys. I think this was opportunistic…. I'm not sure whether this is a true story of being a savior or it was an opportune moment to be violent with somebody, if it indeed happened"; opining Plaintiff has "been in a whole lot more trouble than we're aware of at this point with local authorities"; stating he was accused of "killing a guy he had consensual sex with"; and opining that Plaintiff and McBride got into a fight before McBride ran into the crowd of people. Plaintiff contends Defendants' analysis falsely implies that he is a sociopath or psychopath; he killed someone within three hours before the news interview; he lacks the interpersonal skills, language capacity, and intelligence that would make him a good business partner or leader; he was criminally culpable in his use of force on McBride; he lied about the events and therefore committed perjury at McBride's arraignment; he is "some kind of glory hog who interjected himself into the interviewer's dialogue in an act of self-aggrandizement"; that people did not like him because he was a drifter; he promoted vigilantism; he was a prostitute who engaged in a "prostitution situation" with McBride; that his identity is synonymous with that of a mutt or mongrel from the backstreets; and that he engaged in a pattern of criminal activity before the incident….

Here, the context of Defendants' statements establish that they are rhetorical hyperbole. All reasonable viewers understand Defendants' comments as expressing their beliefs about Plaintiff's actions based on their subjective assessments of his body language actions, not as literal assertions….

Misappropriation of Likeness …

"Georgia recognizes a right of publicity to protect against 'the appropriation of another's name and likeness … without consent and for the financial gain of the appropriator … whether the person whose name and likeness is used is a private citizen, entertainer, or … a public figure who is not a public official.'" …

"In order to navigate between the competing constitutionally protected rights of privacy and publicity and the rights of freedom of speech and of the press, the courts have adopted a 'newsworthiness' exception to right of publicity." "[W]here an incident is a matter of public interest, or the subject matter of a public investigation, a publication in connection therewith can be a violation of no one's legal right of privacy." "[W]here a publisher may be precluded by the right of publicity from publishing one's image for purely financial gain, as in an advertisement, where the publication is newsworthy, the right of publicity gives way to freedom of the press." …

Here, all factors weigh against Plaintiff and establish that he cannot maintain a claim for a violation of his right to publicity as a matter of law. The YouTube Video did not intrude on Plaintiff's private affairs; Plaintiff voluntarily placed himself in the position of public notoriety; and the information is a matter of public record. Defendants analyzed the KMPH news Clip, a matter of public record that Plaintiff acknowledges in his Amended Complaint went viral. There can be "no liability when the defendant merely gives further publicity to information about the plaintiff which is already public." Plaintiff voluntarily placed himself before the public, allowing the news reporter to interview him and later voluntarily appearing on the late-night television show Jimmy Kimmel Live!. Indeed, Plaintiff acknowledges in his Amended Complaint that he is "famous and widely recognized."

Plaintiff contends Defendants used his identity solely to further their own commercial efforts to market their YouTube channel and sell its products. But, having analyzed the Video, it is clear Plaintiff's identity is not being used to sell a product in an advertisement. Defendants do not use Plaintiff's identity on merchandise. And any use of Plaintiff's identity to attract web traffic to Defendants' YouTube channel is merely incidental to the use of Plaintiff's identity. Defendants do not use Plaintiff's identity to endorse or sell their products. The "fact that the publisher or other user seeks or is successful in obtaining a commercial advantage from an otherwise permitted use of another's identity does not render the appropriation actionable." …

[Trademark] …

Even assuming Plaintiff has a trademark ownership in the words "Smash, Smash, SUH-MASH!" and/or the moniker "Kai the Hatchet Wielding Hitchhiker," Plaintiff cannot show consumers were likely to believe that Plaintiff approved, sponsored, was affiliated, or was the origin of the YouTube Video. The YouTube Video is not a copy of Plaintiff's work. Defendants used the public KMPH news Clip to analyze Plaintiff's body language and behavior….

"[L]ikelihood of confusion occurs when a later user uses a trade-name in a manner which is likely to cause confusion among ordinarily prudent purchasers or prospective purchasers as to the source of the product." Plaintiff has not pled nor can he establish that any ordinarily prudent purchaser or prospective purchaser would have any confusion that Plaintiff approved, sponsored, endorsed, was affiliated, or was the source of Defendants' YouTube Video analyzing his body language and behavior….

Copyright …

Plaintiff alleges he created and performed the "dramatic work and spoken words" he used during the KMPH news interview on February 1, 2013. He alleges he registered his copyright to the "dramatic work 'Smash, Smash, SUH-MASH!'" …

[But plaintiff] has no ownership in the KMPH Clip…. "As a general rule, the author is the party who actually creates the work, that is, the person who translates an idea into a fixed, tangible expression entitled to copyright protection." … Plaintiff was an interview subject of the KMPH news interview. He played no role in fixing the clip into tangible expression; KMPH employees "fixed" McGillvary's performance—recording him using KMPH controlled and operated equipment. Plaintiff consented to the live media interview when speaking with the KMPH Fox News reporter, engaging in a question-and-answer format, wherein he recounted the events on February 1, 2013….

Defendants are represented by Pamela Grimes (Wilson, Elser, Moskowitz, Edelman & Dicker LLP).

The post The Hatchet-Wielding-Hitchhiking-Murderer-Unsuccessful-Intellectual-Property-Litigant appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] D.C. Circuit Rejects Journalist's Privilege Claim in Privacy Act Case Involving Fox News

From Chen v. FBI, decided Tuesday by D.C. Circuit Judge Gregory Katsas, joined by Judges Michelle Childs and Harry Edwards:

Yanping Chen alleges that federal officials violated the Privacy Act by disclosing records about her compiled as part of an FBI investigation. The records were published by Fox News. In discovery, Chen sought to compel Catherine Herridge—one of the journalists involved in publishing the records—to identify who had leaked them. Herridge invoked a First Amendment reporter's privilege to avoid being compelled to testify….

{We recite the facts as alleged in the complaint. Yanping Chen was born in China. In 1987, she moved to the United States to study at George Washington University, from which she eventually obtained graduate degrees. Chen became a lawful permanent resident in 1993 and a citizen in 2001.

In 1998, Chen founded the University of Management and Technology (UMT), an educational institution headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. Until January 2018, UMT participated in the Department of Defense's "Tuition Assistance Program," which pays a portion of tuition expenses for military students.

In 2010, the Federal Bureau of Investigation began investigating Chen for statements made on her immigration forms. [Details omitted. -EV] In 2016, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Virginia decided not to file charges against Chen.

In 2017, Fox News aired a report alleging that Chen had concealed her prior work for the Chinese military. The network later published [various FBI documents]…. The print versions of these reports were authored by Catherine Herridge.

In 2018, DoD terminated UMT's participation in the Tuition Assistance Program. That decision, along with a broader hit to UMT's reputation, caused its enrollment and revenue to fall sharply. These losses impacted Chen's income and the value of her personal investment in UMT.} …

In Zerilli v. Smith (D.C. Cir. 1981), this Court recognized a "qualified reporter's privilege" based on the First Amendment. Where it applies, the privilege allows reporters to resist civil discovery into the identity of their confidential sources. We identified two considerations as being "of central importance" in determining whether the privilege applies—the litigant's "need for the information" and her efforts "to obtain the information from alternative sources" [the latter being called the "exhaustion requirement"-EV] We further noted that the "equities weigh somewhat more heavily in favor of disclosure" if, as in libel cases, the journalist is a party and successful assertion of the privilege "will effectively shield him from liability." …

In Lee v. Department of Justice (D.C. Cir. 2005), this Court held that a litigant may overcome the privilege by showing centrality and exhaustion—even in a case where the reporter is not a party. Like this case, Lee involved an appeal by non-party journalists held in contempt for refusing to identify their confidential sources in Privacy Act litigation.

Applying Zerilli's "two guidelines [for] determining when a court can compel a non-party journalist to testify about a confidential source," we held that the district court had not abused its discretion in requiring the reporters to testify. First, the plaintiff had shown that the information he sought went to the "heart" of the case, given the difficulty in proving intent or willfulness without knowing the identity of the leakers. Second, by deposing numerous witnesses before seeking to compel the reporters' testimony, the plaintiff had met his burden to exhaust reasonable alternative sources of information.

For the Lee Court, that was the end of the matter. We expressly declined to engage with Zerilli's distinction between journalists who are parties to a lawsuit and those who are not, since all the journalists in the case before the court were non-parties. And in response to an objection that we were leaving journalists without enough protection, we explained that a litigant's power to subpoena a journalist remains constrained by the requirements of centrality and exhaustion, which are not perfunctory, and by "the usual requirements of relevance, need, and limited burdens on the subpoenaed person" embodied in federal procedural and evidentiary rules….

On appeal, Herridge does not contest the district court's determination that Lee's centrality and exhaustion requirements for overcoming the privilege were satisfied. Herridge nonetheless asks us to rule in her favor because … Chen's Privacy Act claim is frivolous or meritless ….

We reject Herridge's contention that the Privacy Act claim here is frivolous. Herridge presses two main points: "most" of Chen's alleged damages were caused by DoD's independent decision to cut off funds to UMT, and "almost all" of Herridge's reporting came from sources other than Privacy Act information. But "most" is not all, and Chen does seek damages not flowing from a loss of business after DoD severed its ties with UMT.

Likewise, even if Herridge collected "almost all" of her information from material that was already in the public domain, Chen plausibly alleges that some of it had to have come from Privacy Act violations—such as the disclosure of photographs seized from Chen's home during the FBI search. And so long as Chen establishes that some Privacy Act violation harmed her, she may recover actual or statutory damages if it was willful….

Herridge more broadly urges that Chen's claim is simply not that important. In Herridge's view, regardless of centrality and exhaustion, the reporter's privilege should prevail if a court determines that the social importance of the news story outweighs the plaintiff's personal interest in vindicating her claim. Here, for example, Herridge argues that "the public's interest in protecting journalists' ability to report without reservation on sensitive issues of national security" should outweigh Chen's merely private interest in recovering perhaps as little as $1,000 in statutory damages.

Herridge's proposed balancing test echoes the view advanced by the judges dissenting from denial of rehearing en banc in Lee. As they were in dissent, we are left simply to apply the Lee panel opinion…. Lee held that a district court permissibly found a reporter's privilege overcome based on findings of centrality and exhaustion in a Privacy Act case, without any broader balancing of private and public interests. And that suffices to foreclose Herridge's privilege claim here….

Finally, Herridge urges us to recognize, as a matter of federal common law, a reporter's privilege broad enough to permit the case-by-case interest balancing urged by the Lee dissentals. We decline this invitation to end-run our precedent.

Rule 501 of the Federal Rules of Evidence authorizes federal courts to recognize new privileges "in the light of reason and experience." But Herridge has provided little cause to think that "reason and experience" support the privilege that she propounds. As to reason, the First Amendment analysis in cases like Zerilli and Lee thoroughly lays out the competing considerations of encouraging newsgathering while also respecting the elemental principle that "the public has a right to every man's evidence."

As to experience, Herridge contends that virtually every state has recognized some form of a reporter's privilege. She attached to her opening brief a chart summarizing the relevant law in every state. But as this chart demonstrates, the privilege varies widely in its scope from state to state, both in the abstract and on the question whether case-by-case interest balancing is appropriate. In short, if the First Amendment itself does not entitle Herridge to disobey discovery obligations imposed on every other citizen in the circumstances of this case, we see little reason to create that entitlement as a matter of judge-made common law.

Andrew Phillips represents Chen.

The post D.C. Circuit Rejects Journalist's Privilege Claim in Privacy Act Case Involving Fox News appeared first on Reason.com.

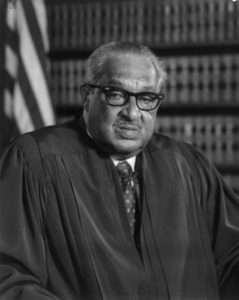

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 2, 1967

10/2/1967: Justice Thurgood Marshall takes the oath.

Justice Thurgood Marshall

Justice Thurgood MarshallThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 2, 1967 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 1, 2025

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: Removal of Firearm Disabilities

[Comments to the NPR are due by October 20, 2025.]

The Attorney General has proposed regulations for procedures for persons to apply for removal of federal firearm disabilities. Most disabilities are found in 18 U.S.C. § 922(g). Under § 925(c), a person prohibited from firearm possession may petition for relief from federal disabilities by applying to the Attorney General, who "may grant such relief if it is established to his satisfaction that the circumstances regarding the disability, and the applicant's record and reputation, are such that the applicant will not be likely to act in a manner dangerous to public safety and that the granting of the relief would not be contrary to the public interest."

In my view, overall the proposed regulations are fair and reasonably implement the above statutory provision. However, there are two items that should be eliminated or modified. Both provide that applications will be denied, absent extraordinary circumstances, if the applicant has been convicted of two types of offenses. Those convictions should be considered on a case-by-case basis instead of being subject to presumptive denial.

Common-law assault convictions

Proposed § 107.1(a) provides in part: "Applications will therefore be denied, absent extraordinary circumstances, if the applicant: (1) Has been convicted under state or federal law of any offense punishable by a term exceeding one year (as defined in 18 U.S.C. 92l(a)(20)) that involves the following conduct, excluding jurisdictional requirements: … (iii) Assault or battery…."

That may be reasonable as applied to such convictions that are truly felonious and aggravated. However, it creates the presumptive denial of relief where the person was convicted of the common-law state misdemeanor of assault and battery, which is punishable by imprisonment for over two years because there is no upper limit on the punishment. That situation exists in Maryland and maybe other states. United States v. Coleman, 158 F.3d 199, 203 (4th Cir. 1998) (en banc), held about Maryland law:

A "crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year" is defined in pertinent part so as to exclude "any State offense classified by the laws of the State as a misdemeanor and punishable by a term of imprisonment of two years or less." … While a Maryland conviction for common-law assault is classified as a misdemeanor, the offense carries no maximum punishment; the only limits on punishment are the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clauses of the Maryland and United States Constitutions. See United States v. Hassan El, 5 F.3d 726, 733 (4th Cir.1993). As such, a Maryland common-law assault "clearly is punishable by more than two years imprisonment" and is not excluded from the definition of a "crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year" by the misdemeanor exclusion. Id.

There are plenty of convictions of this type based on minor incidents, such as a fight in a bar when one is young, that may result in two days in jail, if that. In United States v. Schultheis, 486 F.2d 1331, 1332 (4th Cir. 1973), "The 'felony' conviction upon which the indictment was based was appellant's 1966 conviction of simple assault, a common law crime in Maryland, which grew out of appellant's involvement in a fist fight. For this crime appellant was given a suspended 90-day sentence, fined $25.00 and placed on unsupervised probation for two years."

Accordingly, common-law assault and battery convictions should not be subject to presumptive denial.

Knowing importation of a firearm or ammunition

Proposed § 107.1(a) also provides in part: "Applications will therefore be denied, absent extraordinary circumstances, if the applicant: … (2) Has been convicted under state or federal law of any felony offense involving conduct prohibited under 18 U.S.C. 922 … (1). Section 922(l) makes it "unlawful for any person knowingly to import or bring into the United States … any firearm or ammunition…." Exceptions exist for licensed importers, certain other licensees, and members of the Armed Forces.

Knowing import of a single firearm or a single round of ammunition, absent a wrongful purpose, is a mala prohibita offense that should not presumptively be cause for denial of relief.

In the Gun Control Act, "the term 'knowingly' does not necessarily have any reference to a culpable state of mind or to knowledge of the law." Bryan v. United States, 524 U.S. 184, 192 (1998). Since it is not "necessary to prove that the defendant knew that his [act] was unlawful," the term 'knowingly' merely requires proof of knowledge of the facts that constitute the offense." Id. at 193. By contrast, "with respect to the conduct … that is only criminal when done 'willfully,'" "[t]he jury must find that the defendant acted with an evil-meaning mind, that is to say, that he acted with knowledge that his conduct was unlawful." Id. at 193.

There are numerous gun shows in Europe where an American collector might buy a gun and bring it back without going through a licensed importer. There are shooting matches worldwide in which a participant might bring back a few rounds of unused ammo. The same occurs when a hunter brings back a rifle that had to be replaced or some unused ammo from a foreign country. Such persons may not know that the import must be through a licensed importer, and in such cases the importation would have been granted if done through a licensee.

Such innocent acts contrast sharply with traffickers bringing in guns or ammo for nefarious purposes. Instead of presumptive denial, these should be fact-based decisions.

Readers may spot other provisions that warrant revision. Written comments on the notice of proposed rulemaking must be postmarked and electronic comments must be submitted on or before October 20, 2025.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: Removal of Firearm Disabilities appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Caleb Nelson's Originalist Critique of Unitary Executive Theory

[The prominent originalist legal scholar argues the Constitution does not require that the president have the power to fire executive branch officials.]

NA

NA The Supreme Court seems likely to embrace "unitary executive" theory (UET) in its upcoming case in Trump v. Slaughter, at least in so far as that theory mandates that the president have the power to fire lower-level executive branch officials with any significant policy discretion. It already strongly hinted in that direction in its May "shadow docket" decision in Trump v. Wilcox (though it also suggested the Federal Reserve is an exception to the rule).

Prominent originalist legal scholar Caleb Nelson (University of Virginia) recently posted an originalist critique of UET. Here's an excerpt:

Aside from its provisions about impeachment,… the Constitution does not specifically address the removal of officers in the executive branch (which, for this purpose, includes the enormous variety of agencies that administer an enormous variety of statutes in an enormous variety of ways). Who gets to fire them and for what reasons?

It would be natural to conclude that as with other issues relating to the structure of the executive branch, Congress has broad authority to address this topic by statute. Given the range of tasks that Congress can authorize different officers to perform (entering into contracts, making grants, issuing licenses, conducting formal adjudications, participating in the promulgation of regulations, and more), and given the variety of things that different statutes require or allow these officers to consider (including legal constraints, technical or scientific expertise, the evidence introduced in adjudicative proceedings, and more), one might not expect a one-size-fits-all approach. For sensible policy reasons, Congress might decide that the President should be able to remove many officers or even lower-ranking employees at will, but that other officers or employees should be removable only for defined causes and through defined processes. In my view, the Necessary and Proper Clause lets Congress make these judgment calls as it enacts particular statutes that structure particular agencies.

The Supreme Court, however, has interpreted Article II of the Constitution to address the topic of removal itself. Although the case law is still in flux, the Court appears to be moving toward a sweepingly pro-President position: most officers who participate in the exercise of executive power must be removable at will by the President or his direct subordinates….

As Nelson notes, the text of the Constitution does not indicate that the president has any specific removal authority. And, as the rest of his article describes, historical evidence is at best ambiguous on this score, and may well point to the conclusion that Congress can determine the scope of removal authority.

I, myself, have a different set of originalist reservations about UET, which I most recently outlined earlier this year:

If the executive branch still wielded only the relatively narrow range of powers it had at the time of the Founding, the case for the unitary executive would be pretty strong…. Unfortunately, however, the current scope of executive authority goes far beyond that. To take just one noteworthy example, the president now presides over a vast federal law-enforcement apparatus, much of it devoted to waging the War on Drugs (which accounts for the lion's share of federal prosecutions and prisoners). Under the original meaning of the Constitution - and the dominant understanding of the first 150 years of American history - the federal government did not have the power to ban in-state possession and distribution of goods. That's why it took a constitutional amendment to establish federal alcohol Prohibition in 1919…. Immigration is another field where the executive now wields vast power, despite the fact that, as James Madison and others pointed out, the original meaning of the Constitution actually did not give the federal government any general power to restrict migration into the United States….

The same holds true for a great many other powers currently wielded by the executive branch. The original Constitution does not authorize the federal government to regulate nearly every aspect of our lives, to the point where we have so many federal laws that a majority of adult Americans have violated federal criminal law at some time in their lives (to say nothing of civil law).

There is nothing originalist about giving the president such unconstitutional powers. If "executive" power is the power to "execute" federal laws authorized by the original meaning of the Constitution, it does not apply to powers that have no such authorization. The only way to truly enforce the original meaning in such cases is to remove such authority from federal hands altogether. But if we cannot or will not do that, there is no reason to think that giving the power to the president is any better - from an originalist point of view - than lodging it somewhere else. Either way, someone in the federal government will be wielding power that they are not supposed to have under the original meaning of the Constitution.

If we are not going to enforce the original scope of federal power, then we also should not enforce the (possibly) unitary original distribution of that authority. Concentrating such vast power in the hands of one man would actually run counter to the Framers' objective of promoting separation of powers, and avoiding excessive concentration of power in any one person.

Later in my piece, I criticize the "political accountability" rationale for UET. As I explain, accountability through Congress is just as good as that through the executive, perhaps more so; though neither actually works particularly well, given the combination of vast federal powers and widespread voter ignorance about many of the functions of government. At the very least, accountability rationales can't justify giving one man sweeping authority that goes beyond anything envisioned at the Founding.

Nelson hints at a similar concern about concentration power near the end of his article:

If most of what the federal government currently does on a daily basis is "executive," and if the President must have full control over each and every exercise of "executive" power by the federal government (including an unlimitable ability to remove all or almost all executive officers for reasons good or bad), then the President has an enormous amount of power—more power, I think, than any sensible person should want anyone to have, and more power than any member of the founding generation could have anticipated.

I am an originalist, and if the original meaning of the Constitution compelled this outcome, I would be inclined to agree that the Supreme Court should respect it until the Constitution is amended through the proper processes. But both the text and the history of Article II are far more equivocal than the current Court has been suggesting. In the face of such ambiguities, I hope that the Justices will not act as if their hands are tied and they cannot consider any consequences of the interpretations that they choose.

I agree. Whether these or any other considerations stay the hand of the Supreme Court remains to be seen.

The post Caleb Nelson's Originalist Critique of Unitary Executive Theory appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Eliminating The Voting Rights Act Asymmetry

[After Callais, neither party would benefit from a VRA bonus.]

As a practical matter, the Voting Rights Act helps one political party and hurts the other party. When a Republican legislature draws a gerrymandered map, Democrats will claim that the map harms African American or Hispanic voters. But when a Democratic legislature draws a gerrymandered map, Republicans will have a hard time raising a Section 2 claim that the map harms White voters. Illinois could gerrymander all Republican districts off the map, without any meaningful legal challenges. But if Mississippi or Louisiana tried to gerrymander all the Democratic districts off the map, there would be immediate legal challenges. Indeed, these southern states are forced to create "opportunity" districts to ensure minority voters can elect Democratic politicians.

This is the asymmetry of the Voting Rights Act. Because African American and Hispanic voters tend to vote for Democratic politicians, Democrats will benefit from VRA claims. By contrast, because White voters tend to vote for Republican politicians, Republicans will less likely benefit from VRA claims. What is the upshot? Gerrymandered maps in the South drawn by Republican legislatures are routinely blocked under the VRA, while gerrymandered maps in the North drawn by Democratic legislatures are far more likely to survive.

This asymmetry is not a bug of modern Voting Rights Act jurisprudence. It is a feature. Is it any wonder that Republican groups are lining up behind Louisiana in Callais to weaken, if not nullify Section 2? And is it any wonder why Democratic groups are fighting to save Section 2?

Nick Stephanopoulos has a post at the Election Blog that explains what might happen if the Callais challenge is successful:

A final feature of the SG's proposal is that it would doom most Section 2 claims in areas where most minority voters are Democrats and most white voters are Republicans. In these areas—which notably include much of the South—an additional minority-opportunity district can usually be drawn only at the cost of an existing Republican district. This swap of an old Republican district for a new minority-opportunity district, however, is exactly what the SG's proposal would prevent.

But what is the status quo now? Currently, Democratic voters in the South benefit from the VRA, while Republican voters in the North do not. Much turns on what the baseline is.

I see a similar argument over mid-decade redistricting. If Texas redistricts, then California should redistrict as well. Fair elections, the argument goes, depends on red states not having an advantage over blue states. But this is precisely what the VRA accomplishes: burdening red states, but not burdening blue states.

Callais would eliminate the asymmetry. Going forward, neither party would benefit from a VRA bonus. Critics may charge that this approach is unfair or unjust, but I think that doesn't fully recognize that for decades, the VRA would typically only help one side of the political spectrum. It is no longer 1964. As Shelby County explained more than a decade ago, "things have changed dramatically."

I'm not convinced the sky will fall after Callais. We were told the sky would fall after Rucho v. Common Cause, and it didn't. Now both parties are seeking to engage in overt partisan gerrymandering. I think most predictions of doomsday fail to account for how political groups respond to new dynamics.

The post Eliminating The Voting Rights Act Asymmetry appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers