Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 21

October 6, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

October 5, 2025

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: Supreme Court grants cert in Wolford v. Lopez

[Hawaii law bans firearms on private property open to the public without explicit permission.]

On October 3, the Supreme Court granted cert in Wolford v. Lopez on the following issue: "Whether the Ninth Circuit erred in holding, in direct conflict with the Second Circuit, that Hawaii may presumptively prohibit the carry of handguns by licensed concealed carry permit holders on private property open to the public unless the property owner affirmatively gives express permission to the handgun carrier?"

In response to Bruen's holding that citizens may not be denied permits to carry firearm without a special need, several states enacted sweeping bans on where firearms may be carried. One such provision enacted by Hawaii prohibits the carrying of firearms by a permit holder onto private property open to the public unless the owner affirmatively gives permission by "unambiguous written or verbal authorization" or by the "posting of clear and conspicuous signage." The Ninth Circuit upheld this prohibition in Wolford v. Lopez (2024).

That conflicts with the Second Circuit's decision in Antonyuk v. James (2024), which found violative of the Second Amendment New York's ban on firearm possession by a permitee onto private property open to the public unless the owner or lessee of the property posts clear and conspicuous signage or otherwise gives express consent to bring the firearm onto the property. That created an unprecedented default presumption that carriage is banned, instead of the historical presumption that it is banned only if explicitly done so.

To show that Hawaii's reverse default presumption satisfied Bruen's requirement that a restriction find analogues in American historical tradition, Wolford pointed to a 1771 New Jersey law focusing on hunting that prohibited going on the lands of another armed without consent, and an 1865 Louisiana law that prohibited carrying firearms on the premises or plantation of another without consent. But as Judge Lawrence VanDyke pointed out, dissenting from denial of en banc rehearing, the 1771 New Jersey law was "an antipoaching and antitrespassing ordinance," while the 1865 Louisiana law was one of the "notorious Black Codes that sought to deprive African Americans of their rights, including the right to keep and bear arms otherwise protected by state law."

As I noted in a previous post, the United States filed an amicus curiae brief in support of the cert petition in Wolford, explaining that "after Bruen, five States, including Hawaii, inverted the longstanding presumption and enacted a novel default rule under which individuals may carry firearms on private property only if the owner provides express authorization, such as by posting a conspicuous sign allowing guns." As the brief explained, the Court's consideration of the issue "would help lower courts seeking to interpret the Second Amendment, legislatures seeking to comply with the Constitution, and (most important) ordinary Americans seeking to exercise their fundamental right to possess and carry arms for lawful purposes such as self-defense."

The Wolford cert petition also proposed that the Court resolve a second issue: "Whether the Ninth Circuit erred in solely relying on post-Reconstruction Era and later laws in applying Bruen's text, history and tradition test in direct conflict with the holdings of the Third, Fifth, Eighth and Eleventh Circuits?" While the Court did not grant cert on that issue, it is sure to covered in the briefing, and the Court may well expand on its prior rulings that focused on Founding-era history and allowed later history only if consistent with Founding-era history. On that topic, see Mark W. Smith's article "Attention Originalists: The Second Amendment was adopted in 1791, not 1868."

Another state that tried to nullify Bruen was New Jersey, which prohibited carrying a firearm on "private property, including but not limited to residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural, institutional or undeveloped property, unless the owner has provided express consent or has posted a sign indicating that it is permissible to carry on the premises a concealed handgun." After the briefing in Wolford was complete, on September 10 the Third Circuit decided Koons v. Attorney General New Jersey, which held this ban likely to be violative of the Second Amendment as applied to carriage on private property open to the public, further buttressing the challengers in Wolford.

The Supreme Court has now decided to resolve an outlier law without precedent in American history until a handful of states sought to push back on the Court's ruling in Bruen. Most of the other of the Court's prior Second Amendment precedents invalidated outlier laws – the handgun bans in the District of Columbia (Heller) and Chicago (McDonald), and the discretionary licensing law in New York (Bruen). However it decides Wolford is sure to give major guidance as applied to the avalanche of other Second Amendment cases being litigated mostly in the same restrictive states.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: Supreme Court grants cert in Wolford v. Lopez appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] Oregon Court Strikes Down Trump's Federalization of National Guard

[Judge Immergut's opinion is worth a look, not least because she was a Trump appointee with strong Republican credentials]

The court's opinion, available here, has some powerful language regarding the President's deployment of national guard troops to protect "War-ravaged Portland," as Trump called it on Truth Social. Worth a look.

This case involves the intersection of three of the most fundamental principles in our constitutional democracy. The first concerns the relationship between the federal government and the states. The second concerns the relationship between the United States armed forces and domestic law enforcement. The third concerns the proper role of the judicial branch in ensuring that the executive branch complies with the laws and limitations imposed by the legislative branch. Whether we choose to follow what the Constitution mandates with respect to these three relationships goes to the heart of what it means to live under the rule of law in the United States. . . .

Plaintiffs bring claims alleging that Defendants' actions violate (1) the statutory authority granted the President in 10 U.S.C. § 12406, (2) Oregon's sovereign rights as protected in the Tenth Amendment, (3) the Posse Comitatus Act, (4) the Administrative Procedures Act, and (5) the separation of powers, as well as the Militia and Take Care Clauses of the U.S. Constitution. . . .

For the reasons discussed below, this Court finds that Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their claim that the President's federalization of the Oregon National Guard exceeded his statutory authority under 10 U.S.C. § 12406 and was ultra vires. In addition, because Section 12406 defines the scope of Congress's constitutional delegation to the President to federalize the National Guard, Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their claim that the President exceeded his constitutional authority and violated the Tenth Amendment. . . .

Under 10 U.S.C. § 12406, the President may federalize National Guard service members if: (1) the United States, or any of the Commonwealths or possessions, is invaded or is in danger of invasion by a foreign nation; (2) there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States; or (3) the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.

In Newsom II, the Ninth Circuit held that 10 U.S.C. § 12406 does not "preclude[] judicial review of the President's determination that a statutory precondition exists." However, a reviewing court must give "a great level of deference to the President's determination that a predicate condition exists." A court "review[s] the President's determination to ensure that it reflects a colorable assessment of the facts and law within a 'range of honest judgment.'" At the same time, the Executive's "exercise of his authority to maintain peace" must be "conceived in good faith, in the face of the emergency and directly related to the quelling of the disorder or the prevention of its continuance."

In this case, and unlike in Newsom II, Plaintiffs provide substantial evidence that the protests at the Portland ICE facility were not significantly violent or disruptive in the days—or even weeks—leading up to the President's directive on September 27, 2025. The record evidence establishes that while disruption outside the Portland ICE facility peaked in June of 2025, federal and local law enforcement officers were able to "quell[] . . . the disorder." As of September 27, 2025, it had been months since there was any sustained level of violent or disruptive protest activity in Portland. During this time frame, there were sporadic events requiring either PPB monitoring or federal law enforcement intervention, but overall, the protests were small and uneventful.

This deployment of additional federal law enforcement officers reduced the level of disorder between June and September to the point that in the immediate days leading up to the federalization order, around twenty or fewer protesters gathered outside the ICE Facility and "FPS indicated no issues or criminal reports." On September 26, the eve of the President's directive, law enforcement "observed approximately 8–15 people at any given time out front of ICE. Mostly sitting in lawn chairs and walking around. Energy was low, minimal activity." It is clear that "the regular forces," i.e. FPS and additional federal law enforcement, were able to execute the laws of the United States. . . .

"[A] great level of deference" is not equivalent to ignoring the facts on the ground. As the Ninth Circuit articulated, courts must "review the President's determination to ensure that it reflects a colorable assessment of the facts and law within a 'range of honest judgment.'" Here, this Court concludes that the President did not have a "colorable basis" to invoke § 12406(3) to federalize the National Guard because the situation on the ground belied an inability of federal law enforcement officers to execute federal law. The President's determination was simply untethered to the facts. . . .

[T]he following "key characteristics" provide the boundaries for what constitutes a "rebellion": First, a rebellion must not only be violent but also be armed. Second, a rebellion must be organized. Third, a rebellion must be open and avowed. Fourth, a rebellion must be against the government as a whole—often with an aim of overthrowing the government—rather than in opposition to a single law or issue. Here, the protests in Portland were not "a rebellion" and did not pose a "danger of a rebellion," especially in the days leading up to the federalization. As discussed above, Defendants presented evidence of sporadic violence against federal officers and property damage to a federal building. Defendants have not, however, proffered any evidence demonstrating that those episodes of violence were part of an organized attempt to overthrow the government as a whole, and therefore, Defendants have failed to show that the President had a colorable basis to conclude that Section 12406(2) was satisfied.

Furthermore, this country has a longstanding and foundational tradition of resistance to government overreach, especially in the form of military intrusion into civil affairs. "That tradition has deep roots in our history and found early expression, for example, in . . . the constitutional provisions for civilian control of the military." Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1, 15 (1972); see also James Madison, Address to the Constitutional Convention (1787), reprinted in 1 Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, at 465 ("A standing military force, with an overgrown Executive will not long be safe companions to liberty. The means of defence [against] foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home."). This historical tradition boils down to a simple proposition: this is a nation of Constitutional law, not martial law. Defendants have made a range of arguments that, if accepted, risk blurring the line between civil and military federal power—to the detriment of this nation.

The post Oregon Court Strikes Down Trump's Federalization of National Guard appeared first on Reason.com.

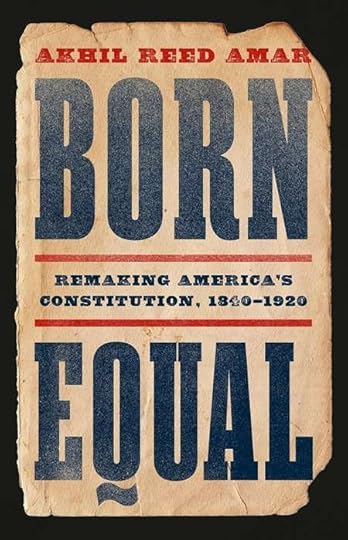

[Steven Calabresi] Gordon S. Wood Weighs in on Akhil Reed Amar's Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840-1920

[Praise from Wood for what I think is the best new book this year.]

On September 16, Yale Law professor Akhil Reed Amar published Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840-1920, the second volume of an in-progress three-volume history of America's constitutional project from 1760 to the present day. The first volume, The Words That Made Us: America's Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840, was published in 2021. I much liked both volumes (more on that below), and I'm delighted to report that America's greatest historian of the Founding era, Gordon S. Wood, has recently publicly praised them as well.

Wood wrote a detailed review of Born Equal that he read aloud at a September 19 Yale Law School conference on originalism that I organized; Wood labeled Born Equal "wonderful" and went on to say that,

[I]t is the most extraordinary kind of history that I have read…. [Akhil] has paid tribute to the power of equality in our political and constitutional lives as no other historian ever has.

The complete transcript of Wood's glowing remarks may be found here, and may well be published in more polished form in the months ahead.

Kirkus Reviews awarded Born Equal a rare and much-coveted Kirkus Star and The Wall Street Journal ran a rave review by Adam J. White. The New York Times review by Jeff Shesol was generally favorable, but criticized Akhil's staunch defense of originalism. Read Born Equal and decide for yourself!

As I mentioned, I liked both volumes very much. Back in 2021 I described The Words That Made Us as:

[A] masterpiece [that] reveals Akhil Amar to be the greatest constitutional historian of his generation. He brilliantly shows, for example, how George Washington got everything he wanted at the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, while geniuses like Madison, Hamilton, Wilson, and Franklin all came up short. This book will be the canonical account of the birth of our Constitution and our early years as a nation for decades to come.

And here is what I said about Born Equal:

Akhil Reed Amar is the most accomplished scholar of his age cohort in both law and history because he writes superb books like Born Equal, which will change the minds of everyone across the political spectrum from Federalist Society members to Bernie Sanders leftists. The history told in this book goes to the very core of what it means to be an American citizen and to understanding our Constitution. Amar knows, that for all our faults, the United States is, as President Ronald Reagan called it, "A Shining City on a Hill." This book brilliantly proves that Ronald Reagan was right! Born Equal is one of the most important books ever written.

Akhil and I have been close friends for decades, and we have co-taught an originalism seminar at Yale Law School for many years. I'm glad that others share my view as well.

The post Gordon S. Wood Weighs in on Akhil Reed Amar's Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840-1920 appeared first on Reason.com.

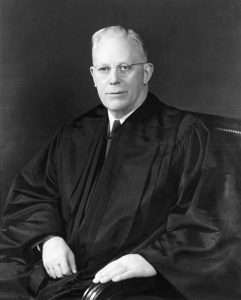

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 5, 1953

10/5/1953: Chief Justice Earl Warren takes the oath.

Chief Justice Earl Warren

Chief Justice Earl WarrenThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 5, 1953 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Sunday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Sunday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

October 4, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] The Proposed "Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education" and the First Amendment

[1.] There's a lot going on in the Trump Administration's proposed "Compact," and there's a lot that we might want to ask about it. Some questions would have to do with whether particular demands (such as a tuition freeze or a 15% cap on foreign students or mandatory U.S. civics classes for foreign students) are a good idea. Some might be and some might not be. Some might have to do with the way that the Compact would rebalance power between universities and the federal government.

Some might have to do with whether particular demands (for instance, the requirement that universities require all applicants to take standardized admission tests) should be implemented top-down on a one-size-fits-all basis. The federal government may have the power to impose certain conditions on the recipients of government funds, but that doesn't mean that it necessarily should do so. This question of when conditions become excessive micromanagement perennially arises when it comes to government contracts and grants.

Some questions have to do with whether the Executive Branch can impose these conditions through just an announcement, whether this would require notice-and-comment regulatory rulemaking, or whether it would require express Congressional authorization. Similar questions have arisen in the past with regard to whether, for instance, Title IX should be understood to mandate university investigation of alleged sexual assault by students; whether it should be understood as mandating a preponderance-of-the-evidence standard in such situations rather than a clear-and-convincing-evidence; and other matters. In particular, the Compact seems to contemplate conditions on universities' "preferential treatment under the tax code," which I expect would likely require revisions to the tax code. But there too there have been controversies about where the Executive Branch has power to read provisions into tax exemption requirements that hadn't been expressly authorized by Congress (see, e.g., Bob Jones Univ. v. U.S. (1983)).

Still, I can at most note such matters—important as they are—since they aren't within my core area of expertise. So let me turn instead to the First Amendment problems posed by the Compact, which I am more knowledgeable about. I don't want to suggest that these are the most important issues, but that's where the light is best for me, so maybe I can find some keys there.

[2.] As a general matter, when the government is providing funding or other benefits for private parties' speech, it may not discriminate based on viewpoint. Thus, for instance, Rosenberger v. Rector (1995), held that when a university funds student newspapers, it can't exclude ones that convey religious viewpoints. The Court there expressly "reaffirmed the requirement of viewpoint neutrality in the Government's provision of financial benefits." Many other precedents say the same.

To be sure, the government may create programs for conveying its own preferred viewpoints. As Rust v. Sullivan (1991) noted, Congress can set up a National Endowment for Democracy without setting up a National Endowment for Communism. But the Court has distinguished such government speech, which the government can select based on viewpoint, from government programs that subsidize a diverse range of private speech, as in Rosenberger. To quote Rosenberger again,

[W]hen the government appropriates public funds to promote a particular policy of its own it is entitled to say what it wishes. When the government disburses public funds to private entities to convey a governmental message, it may take legitimate and appropriate steps to ensure that its message is neither garbled nor distorted by the grantee. It does not follow, however, … that viewpoint-based restrictions are proper when the [government] does not itself speak or subsidize transmittal of a message it favors but instead expends funds to encourage a diversity of views from private speakers.

Moreover, the government can't impose even viewpoint-neutral funding conditions that seek to restrict the recipient's speech using its own funds. Thus, in FCC v. League of Women Voters (1984), the Court struck down a law that barred editorializing by the recipients of public broadcasting subsidies. The Court acknowledged that the government could provide that federal funds can't be used to editorialize (that would be a viewpoint-neutralize restriction). But Congress can't provide that "a noncommercial educational station that receives only 1% of its overall income from [federal] grants is barred absolutely from all editorializing." It is unconstitutional for Congress to thus bar a partly federally subsidized station "from using even wholly private funds to finance its editorial activity."

[3.] In the Compact, the government isn't just awarding grants for promoting particular government-supported viewpoints, which both Democrat and Republican administrations have long done. Rather, it applies to a vast range of funding and benefit programs, such as "(i) access to student loans, grant programs, and federal contracts; (ii) funding for research directly or indirectly; (iii) approval of student and other visas in connection with university matriculation and instruction; and (iv) preferential treatment under the tax code." Indeed, when it comes to tax exemptions, Rosenberger expressly made clear that "Congress' choice to grant tax deductions" was subject to "the requirement of viewpoint neutrality"; and see also the similar holding in Matal v. Tam (2017) with regard to the nonmonetary benefit of trademark registration.

[a.] This suggests that the Compact's requirement that, as a condition of getting benefits, signatories must "commit themselves" "to transforming or abolishing institutional units that purposefully … belittle … conservative ideas" is unconstitutional: It targets particular viewpoints (those that "belittle … conservative ideas"), however vaguely defined those viewpoints may be.

[b.] I think the same is likely true about the demand that universities "shall adopt policies prohibiting incitement to violence, including calls for murder or genocide or support for entities designated by the U.S. government as terrorist organizations." To be sure, "incitement" may constitutionally be even criminalized outright, if it's limited to speech intended to and likely to produce imminent illegal action, which is to say action in the coming hours or days, as opposed to speech that advocates such action "at some indefinite future time." (See Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) and Hess v. Indiana (1973).) But in context, that doesn't seem the likely meaning of the demand: After all, basically no speech in the U.S. involves advocacy of imminent genocide by the listeners (as opposed to calls for genocide at some indefinite future time), and even calls for murder on college campuses are almost invariably calls for violence at some indefinite future time.

Likewise, while "material support" for foreign terrorist organizations, in the sense of providing personnel, training, and the like, is constitutionally unprotected (see Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010)), "support" in the lay sense—which is to say independent expression of endorsement of a terrorist organization's position or actions—remains constitutionally protected. Indeed, Holder several times stressed that the law upheld in that case "does not cover independent advocacy" supporting a foreign terrorist group's position.

So unless the "shall adopt policies prohibiting incitement to violence, including calls for murder or genocide or support for entities designated by the U.S. government as terrorist organizations" is read very narrowly indeed, this demand would require universities to suppress fully protected student speech. And even if a private university could suppress such speech on its own (simply because a private university isn't itself constrained by the First Amendment), the government can't pressure the university into engaging in suppression (see, e.g., NRA v. Vullo (2024)).

[c.] I also think the government can't demand that universities, as a condition of getting benefits, "pledge … screen out [foreign] students who demonstrate hostility to the United States, its allies, or its values."

The government likely can deny visas to prospective students based on their viewpoints; see Kleindienst v. Mandel (1972) (I oversimplify matters here somewhat). Whether the federal government can deport already-admitted people based on such speech is a separate matter, but it likely can reject them when they're just applying for a student visa.

But that's something the government can do itself, because of its special power over immigration. I don't think it can demand that universities, in exercising their own decisions about whom to associate with and whom to speak to, exclude foreign students based on the students' viewpoints.

[d.] The Compact also requires that universities receiving federal benefits "shall maintain institutional neutrality at all levels of their administration," including "all colleges, faculties, schools, departments, programs, centers, and institutes." This means "that all university employees, in their capacity as university representatives, will abstain from actions or speech relating to societal and political events except in cases in which external events have a direct impact upon the university." This expressly does not apply to "students, faculty, and staff" commenting "in their individual capacities, provided they do not purport to do so on behalf of the university or any of its sub-divisions."

This requirement, unlike the ones I discussed in items (a) to (c) above, is facially viewpoint-neutral; and I think the government could require that no federal funds be spent on ideological commentary by university departments. That would be much like the requirement, upheld in Regan v. Taxation with Representation (1983), that no tax-exempt contributions—which are in effect subsidized by the government through the charitable tax exemptions—be spent on advocacy for or against a candidate, or on substantial advocacy for or against legislation. To be sure, Regan involved only candidate- and legislation-related speech, not all ideological advocacy, but I think such a viewpoint-neutral requirement would be permissible even if it covers ideological advocacy more broadly.

But as I read the Compact, it contemplates that universities "abstain from … speech relating to societal and political events" even when such speech is paid for solely with their own funds (of which universities have plenty). And that's precisely the sort of broad condition on funding that the Court struck down in FCC v. League of Women Voters, when it held that the government couldn't use its subsidies to public broadcasters to prohibit all editorializing by the broadcasters (including editorializing paid for from other funds).

I appreciate the rationale the Compact offers for the mandate, quoting the President of Dartmouth:

Consider a student interested in majoring in a certain subject. Upon going to the department homepage to discover course offerings, the student is slapped in the face with an official statement excoriating his own political ideology. How comfortable would that student feel taking a class in that department? Our Principles of Institutional Restraint permit departments to issue public statements only on limited issues directly related to their academic expertise. Rather than publishing these proclamations on their homepages, departments must create new webpages specifically dedicated to public statements and endorsements. This ensures that departments promote their academic missions, not their social or political beliefs.

I generally support such ideological neutrality mandates for university administrations and departments myself as a policy matter, partly for this very reason. But whatever the value of institutional neutrality mandates as a means of promoting uninhibited discourse among students and faculty, I don't think that this value can justify suppressing speech by the universities themselves. And, as FCC v. League of Women Voters makes clear, that remains so even when the universities are receiving government money to support some of their operations.

[e.] The Compact also seems to broadly call for universities to promote a "broad spectrum of ideological viewpoints." As I'll be blogging this coming week, I have a forthcoming law journal article in which I argue that ideological diversity mandates are generally a bad idea and likely unconstitutional, even when they are imposed as a condition on access to government funding. This having been said, it's not completely clear whether the Compact outright demands enforceable viewpoint mandates (which the April letter to Harvard appears to have contemplated), or whether it sets forth viewpoint diversity as an aspirational goal, the way one might set "excellence," "openmindedness," and the like as an aspirational goal.

The Compact states, in relevant part, that funding recipients must "commit themselves to fostering a vibrant marketplace of ideas on campus," to engaging in a "rigorous, good faith, empirical assessment of a broad spectrum of viewpoints among faculty, students, and staff at all levels," to "sharing the results of such assessments with the public," and to "seek[ing] such a broad spectrum of viewpoints not just in the university as a whole, but within every field, department, school, and teaching unit." It also states that "A vibrant marketplace of ideas requires an intellectually open campus environment, with a broad spectrum of ideological viewpoints present and no single ideology dominant, both along political and other relevant lines." The question here, I think, will largely turn on how such a call for a vibrant marketplace of ideas and a broad spectrum of viewpoints will be operationalized.

[* * *]

In any event, these are just some tentative thoughts about some of the provisions; I look forward to seeing more discussion of the Compact in the months ahead.

The post The Proposed "Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education" and the First Amendment appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] First Circuit Rules Trump's Birthright Citizenship Executive Order is Unconstitutional

[This is the second appellate court ruling against the order. So far, every court that has addressed this issue has ruled the same way.]

Photo by saiid bel on Unsplash; Reamolko

Photo by saiid bel on Unsplash; Reamolko Yesterday, the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit issued a decision that Donald Trump's executive order denying birthright citizenship to children of undocumented immigrants and non-citizens present on temporary visas is unconstitutional. It also ruled that it violates a 1952 law granting naturalization to children born in the United States, and upheld a nationwide injunction against implementation of the order. This is the second appellate court decision ruling against Trump's order, following an earlier Ninth Circuit decision. Multiple district court judges (including both Democratic and Republican appointees) have also ruled that the order is illegal, and so far not a single judge has voted to uphold it.

Judge David Barron's opinion for the First Circuit runs to 100 pages. But he emphasizes that this length is the product of the large number of issues (including several procedural ones) that had to be considered, and does not mean the case is a close one:

The analysis that follows is necessarily lengthy, as we must address the parties' numerous arguments in each of the cases involved. But the length of our analysis should not be mistaken for a sign that the fundamental question that these cases raise about the scope of birthright citizenship is a difficult one. It is not, which may explain why it has been more than a century since a branch of our government has made as concerted an effort as the Executive Branch now makes to deny Americans their birthright.

I won't try go to through all the points in the decision in detail. But I think Judge Barron's reasoning is compelling and persuasive, particularly when it comes to explaining why this result is required under the Supreme Court's ruling in the 1898 Wong Kim Ark case, and why the 1952 naturalization statute provides an independent ground for rejecting Trump's order.

I would add, as I have noted previously (e.g. here and here), that virtually all the government's arguments for denying birthright citizenship to children of undocumented immigrants and those on temporary visas would also have denied it to numerous slaves freed as a result of the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment. For example, if children of people who entered the US illegally are ineligible, that would exclude the children of many thousands of slaves who were brought into the US illegally after Congress banned the slave trade in 1808. And granting citizenship to freed slaves and their children was, of course, the main purpose of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

I also think the ruling is sound in concluding that the state government plaintiffs in the case have standing to sue (though, admittedly, the Supreme Court's precedents on state standing are far from a model of clarity), and in suggesting that "complete relief" for their injuries requires a nationwide injunction (though it ultimately remanded this issue to the district court for further consideration). State lawsuits are one of several possible exceptions to the Supreme Court's general presumption against nationwide injunctions in Trump v. CASA, Inc. Both this exception and that for class actions have been used in lower court decisions against the birthright citizenship order, since Trump v. CASA came down in June. These exceptions are among the reasons why CASA has so far not had anywhere near as devastating an impact as some feared (though I continue to believe it was a bad decision).

Both the substantive birthright citizenship issue and the procedural issue of the proper scope of injunctions are likely to return to the Supreme Court. Hopefully, the justices will affirm the lower court rulings on these issues. We shall see.

The post First Circuit Rules Trump's Birthright Citizenship Executive Order is Unconstitutional appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Lawsuit Challenges Trump's $100,000 H-1B Visa Fee

[The case was filed yesterday by a broad coalition of different groups, including a health care provider, education groups, religious organizations, and labor unions.]

NA

NA Yesterday, a broad coalition of groups filed the first lawsuit challenging President Trump's imposition of a $100,000 fee on applications for H-1B visas, which are used by tech firms, research institutions, and other organizations to hire immigrant workers and researchers with various specialized skills. If allowed to stand, the fee would effectively end most H-1B visas, by making them prohibitively expensive, thereby inflicting serious harm on the US economy.

The case is called Global Nurse Force v. Trump. The plaintiffs are a broad coalition including the Global Nurse Force (which supplies nurses to health care providers), education groups (e.g. - the American Association of University Professors), religious organizations, and labor unions. I am a little surprised that multiple labor unions joined this lawsuit, as one might think they would want to keep out potential competitors to their members. However, I would guess they have H-1B visa holders among those members. In addition, studies show that H-1B workers actually increase wages for many US-citizen workers by increasing productivity and innovation.

The complaint argues the H-1B visa is illegal for a number of different reasons. Here's a brief excerpt that summarizes some of them:

Defendants' abrupt imposition of the $100,000 Requirement is unlawful. The

President has no authority to unilaterally alter the comprehensive statutory scheme created by Congress. Most fundamentally, the President has no authority to unilaterally impose fees, taxes or other mechanisms to generate revenue for the United States, nor to dictate how those funds are spent. The Constitution assigns the "power of the purse" to Congress, as one of its most fundamental premises. Here, the President disregarded those limitations, asserted power he does not have, and displaced a complex, Congressionally specified system for evaluating petitions and granting H-1B visas. The Proclamation transforms the H-1B program into one where employers must either "pay to play" or seek a "national interest" exemption, which will be doled out at the discretion of the Secretary of Homeland Security, a system that opens the door to selective enforcement and corruption.

The plaintiffs also argue that the government's assertion of virtually unlimited power to impose visa fees goes against the major questions doctrine (which requires Congress to speak clearly when it delegates broad powers to the executive over issues of vast economic and political significance), and the constitutional nondelegation doctrine, which limits delegation of legislative power to the executive branch.

I made similar points in an earlier post about the H-1B visa fee policy, where I explained why it goes against the statutory scheme enacted by Congress, and why it would violate the nondelegation doctrine if Congress had delegated this power.

As the Global Nurse Force complaint notes, enforcing nondelegation is particularly crucial when it comes to the power to raise revenue, which is a specifically enumerated congressional power. The $100,000 fee goes far beyond anything that could plausibly be described as defraying administrative expenses, and is essentially a form of taxation. The Framers of the Constitution were careful to ensure that only the legislative branch could impose taxes, in order to avoid the abusive executive taxation pursued by 17th century British monarchs. This is one of several areas where Trump is attempting to usurp this legislative power. Others include his unilateral imposition of massive tariffs, and his unconstitutional export taxes (which even Congress lacks the power to impose under the Constitution).

I hope the plaintiffs prevail here. I expect there may also be other lawsuits challenging the H-1B fee.

The post Lawsuit Challenges Trump's $100,000 H-1B Visa Fee appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Especially Concerned About Hallucinations in Criminal Defense Lawyer's Filings

From California Court of Appeal Justice Judith McConnell, writing for the court Thursday in People v. Alvarez; the lawyer involved has been licensed in California for 54 years:

[A filing in this case] included a quotation attributed to In re Benoit (1973) 10 Cal.3d 72, 87–88, but the purported quote did not exist in the case. Attorney Siddell later clarified that it was not a direct quotation because he modified it "to incorporate broader principles."

The opposition also included a citation to a case that does not exist: People v. Robinson (2009) 172 Cal.App.4th 452. Counsel additionally cited two cases that do not address the issues for which they were cited: People v. Jones (2001) 25 Cal.4th 98 and People v. Williams (1999) 77 Cal.App.4th 436….

At [a] hearing [after the matter was discovered], Attorney Siddell apologized for failing to verify the legal citations and sources included in his motion and explained that this failure resulted from feeling rushed. He reported he had taken courses regarding artificial intelligence (AI) and was aware that AI could hallucinate cases, but he did not verify the accuracy of any citations. He explained he relies on staff to help draft motions and briefs, but he recognized it is his responsibility to check the caselaw before submitting documents to the court. He said in the future he would "trust but verify" research provided through the use of AI….

The Second Appellate District recently published Noland v. Land of the Free, L.P., discussing the impact of the improper use of AI. We agree with our colleagues that "there is nothing inherently wrong with an attorney appropriately using AI in a law practice," but attorneys must check every citation to make sure the case exists and the citations are correct….

The conduct here is not as egregious as what occurred in Noland. But it is particularly disturbing because it involves the rights of a criminal defendant, who is entitled to due process and representation by competent counsel. Courts are obligated to ensure these rights are protected.

When criminal defense attorneys fail to comply with their ethical obligations, their conduct undermines the integrity of the judicial system. It also damages their credibility and potentially impugns the validity of the arguments they make on behalf of their clients, calling into question their competency and ability to ensure defendants are provided a meaningful opportunity to be heard. Thus, criminal defense attorneys must make every effort to confirm that the legal citations they supply exist and accurately reflect the law for which they are cited. That did not happen here.

Attorney Siddell admitted to violating his professional duty by including a hallucinated citation and misrepresenting the law provided in other opinions…. Attorney Siddell voluntarily withdrew from representation, and new counsel was appointed to protect the defendant's rights, but his unprofessional behavior cost the court time and resources.

Because we conclude Attorney Siddell has violated a Rule of Professional Conduct, we are required to "take appropriate corrective action." In line with this obligation, we are publishing this order. Further, consistent with the notion that sanctions should deter future improper behavior, we issue a sanction in the amount of $1,500 to be paid by Attorney Siddell individually to the Fourth District Court of Appeal, Division One. This monetary sanction will also reimburse the court for a small portion of the time and resources expended on this issue.

We direct the Clerk of this court to notify the State Bar of the sanctions against Attorney Siddell.

Thanks to Irwin Nowick for the pointer.

The post Court Especially Concerned About Hallucinations in Criminal Defense Lawyer's Filings appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers