Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 131

April 2, 2025

[Keith E. Whittington] AFA Statement on Speech Rights of Foreign Nationals

After several high-profile examples of university students having their authorization to study in the United States revoked and of international scholars being turned away at the border, the Academic Freedom Alliance has released a statement on the deportation of foreign scholars and students. There are clearly circumstances in which foreign nationals can and should be expelled from the country, but the administration's actions have had the effect of dampening lawful but politically disfavored speech on American college campuses and pose a serious threat to the international academic community.

Foreign students and scholars who enter in the United States, temporarily or indefinitely, do so on a conditional basis, and if they violate the conditions of their lawful presence in the country they can properly be removed. It is imperative that the permission of foreign students and scholars to enter or remain in the country be revoked only for the proper reasons, which do not include the mere expression of controversial scholarly, political, or social views. If foreign scholars and students are going to be able to live and work in the United States, to express themselves freely in public and to engage in the ordinary activities of scholarship and teaching, they must be confident that their status will not be put at risk by their engaging, alongside other members of the academic community, in the lawful expression of ideas that those with political power happen to find controversial.

We call on American government officials to clearly state that international students and scholars will not be removed from the country simply for engaging in lawful expressive activities, whether personal or professional. We call upon American government officials to clearly state the factual basis and legal rationale when visas are revoked. A climate of uncertainty is itself a threat to the free exchange of ideas on American university campuses. It is imperative that the government not only refrain from removing individuals from the country for exercising First Amendment liberties but also credibly reassure the scholarly community that the immigration laws will not be used to stifle First Amendment protected speech.

The post AFA Statement on Speech Rights of Foreign Nationals appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Harlan Virtual Supreme Court Round of Four

[Ten teams of high school students presented oral arguments on Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton.]

The topic for the 13th Annual Harlan InstituteVirtual Supreme Court competition is Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton. Yesterday, the top four teams presented oral arguments. The Championship Round will be held at the Georgetown Supreme Court Institute on May 1, 2025 between Teams #20601 and 20094.

Round of 4 Match #1 Round of 4 Match #2The post Harlan Virtual Supreme Court Round of Four appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Drama and Misgendering at the Imperial Court

From Rozanski v. Rocky Mountain Court System, Inc., decided Feb. 16, 2023 by the Colorado Court of Appeals (Judge Craig Welling, joined by Judges David Furman and Rebecca Freyre) but just recently posted on Westlaw:

The ICRME {Imperial Court of the Rocky Mountain Empire} is a nonprofit organization that serves Colorado's lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, plus (LGBTQ+) community. Among other things, the ICRME holds functions and raises funds for related charities. The ICRME is a chapter of the International Court System (ICS) and the International Court Council (ICC).

Each year, members of the ICRME elect a leader for the organization's fundraising endeavors, which include charitable drag shows. The person so elected receives the honorary title of "Emperor" or "Empress." The events surrounding the 2018 election led to this dispute.

Haskett, Brendlinger, Whitley, and Menchaca were on the ICRME's eleven-member Board of Directors (the Board). Norrie Reynolds was a long-time member of the ICRME and a previous Empress. Reynolds and Rozanski were close friends.

Rozanski founded and owns a large retailer and distributor of comic books. {Rozanski uses "they," "them," and "their" pronouns.} As part of their business, they distribute a newsletter to over 120,000 people worldwide. They also distribute a national newsletter to over 10,000 people in the United States. They have profiles on websites such as IMDb and Wikipedia. Rozanski was also an ICRME member. They sometimes participated in ICRME drag shows using the alter ego "Bettie Pages."

On March 22, 2018, two days before the annual election, Reynolds—who is not a party to this appeal—told Whitley that Rozanski was organizing an "anti-gay rally." According to Reynolds, Rozanski's rally would occur during the election at the Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods facility in Denver, which was the polling location for the election. Whitley immediately relayed this information to the rest of the Board in an email. Haskett subsequently called Reynolds, who confirmed what she had reported to Whitley. Reynolds also told Haskett that "she was afraid"; that she was "feeling unsafe for herself and ICRME"; and that Rozanski "had a temper" and "was out to get" Whitley, Menchaca, and Haskett.

That same day, the Board held a closed emergency meeting to address the alleged threat. At Haskett's invitation, the candidates for Emperor and Empress also attended the emergency meeting. During the meeting, Haskett repeated Reynolds' statements about Rozanski's alleged threats to individual Board members. The Board unanimously approved significant changes to the 2018 election process. Such changes included moving the location of the polling station, hiring security, and limiting voting to paying ICRME members.

Without contacting Rozanski regarding the allegations, the Board released a public statement and posted it on the ICRME's website. We will refer to this as the "Public Statement." In the Public Statement, the Board announced the election changes and outlined the alleged threat in the following terms (without identifying Rozanski by name or description):

A concern was brought to the Board of Directors in regards to the safety for people on Voting Day, March 24th, 2018 …. The Board of Directors got information that there was going to be an Anti-Gay Rally on Voting Day ….

Whether this information may be true or not, the Board of Directors must take this matter seriously ….

Rozanski themself republished the Public Statement to about 11,000 people through their Facebook profile and their national newsletter. The day before the election, Rozanski publicly posted that they'd engaged a defamation attorney. On election day, they went to the original location of the voting polls and passed out copies of the Public Statement.

Many ICRME members saw the Board's decision to modify election procedures as a ploy to suppress votes and rig the election. Menchaca exchanged posts and comments with several ICRME members on Facebook. He defended the Board's decision to change the 2018 election process, reiterating his concerns about the risk of violent demonstrations. Menchaca didn't name Rozanski in any of his posts.

The day after the election, the Board had a private conference call with the national leaders of the ICS and ICC. The call was recorded. During this call, Brendlinger made comments about an alleged confrontation between Rozanski and Rob Surreal, one of the national leaders. During the same call, Haskett defended the Board's election changes despite criticism from the national leaders.

Rozanski sued Reynolds for providing false information. They settled with her after she provided an affidavit and compensation for attorney fees, emotional distress, reputational damages, and pain and suffering.

Rozanski subsequently sued the ICRME, as well as Haskett, Brendlinger, Whitley, and Menchaca in their individual capacities. Rozanski brought claims of defamation, civil conspiracy, intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED), respondeat superior, and aiding and abetting against the defendants.

The court threw out Rozanski's defamation claims:

As a preliminary matter, we accept Rozanski's concession that they're a public figure. Hence, we focus our analysis on whether there's clear and convincing record evidence that the defendants acted with actual malice….

In contending that the defendants acted with actual malice, Rozanski argues that the defendants failed to investigate Reynolds' allegations before issuing the Public Statement. Rozanski maintains that the defendants—allegedly ignoring the prompting of several ICRME members—deliberately chose not to reach out directly to verify or corroborate the allegations. Rozanski asserts that the defendants, therefore, knowingly acted without supporting evidence….

[But] the defendants did have a basis for their statements: they received notice of threats from Reynolds, whom they all knew to be close to Rozanski. This isn't disputed. In addition, Reynolds had been sufficiently respected and trusted within the ICRME to have previously served as its Empress. Whereas the reporter in Burns knew that the sergeant was "frustrated" and "bitter," and that his comments should be viewed skeptically, our review of the present record reveals no similar evidence suggesting that the defendants—at the time Reynolds communicated the alleged threats—had cause for similar skepticism….

[T]he defendants here were [also] acutely time-pressured…. Reynolds communicated the threats on March 22, 2018, only two days before the election was scheduled. Given the complicated logistics of altering well-established election procedures along with the scale of election day, which could involve hundreds of ICRME members, any changes would need to be implemented immediately to take effect before the event on March 24, 2022 [likely should be 2018 -EV]. Additionally, even viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to Rozanski, as we must, the nature of the alleged threats in this case placed heightened pressure on the Board to respond effectively within a short timeframe: the allegations concerned an anti-gay rally on election day at the polling place, which, if true, posed the risk of violence and disorder at a large LGBTQ+ gathering….

Moreover, the tight timeframe here undermines the utility of pursuing the most obvious source of possible refutation—namely, Rozanski, who, for the purpose of resolving this summary judgment appeal, we presume would've denied making the threat. Meaningful investigation, therefore, would've required subsequent inquiries, such as thorough discussions with Rozanski, Reynolds, and several ICRME members; a deliberative balancing of the resulting information, which, based on the record before us, would've been conflicting; followed by consultations with ICS and ICC leadership.

Even if the two-day window afforded time for some of these inquiries, and the defendants negligently failed to pursue them, Rozanski has nonetheless failed to submit sufficient evidence to prove with convincing clarity that the defendants made the statements with actual malice….

The court also rejected Rozanski's claims of intentional infliction of emotional distress based on "misgendering":

To state a claim for IIED by outrageous conduct, a plaintiff must allege behavior by a defendant that is extremely egregious…. "Liability has been found only where the conduct has been so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency, and to be regarded as atrocious, and utterly intolerable in a civilized community." Although the jury ultimately determines whether conduct is outrageous, a court must first determine if reasonable persons could differ on the question….

Rozanski highlights that extreme and outrageous conduct may also "arise from the actor's knowledge that the other is peculiarly susceptible to emotional stress, by reason of some physical or mental condition or peculiarity." They further emphasize that the "conduct may become heartless, flagrant, and outrageous when the actor proceeds in the face of such knowledge, where it would not be so if he did not know."

Rozanski alleges that the defendants knew that Rozanski was susceptible to severe depression and suicidal urges, and that misgendering them would exacerbate these conditions. Yet, Rozanski claims, the defendants recklessly disregarded this and refused to let them present at ICRME events in conformity with their gender identity. Rozanski points to no concrete examples in the record of misgendering at ICRME drag shows and we can find none.

Instead, Rozanski's own affidavit suggests that they're referring to "various events" at "outside court[s]." For example, Rozanski alleges that misgendering occurred through the submission of their "protocol" with the "incorrect gender" at events in Las Vegas, New York, and Colorado Springs. Rozanski explains in their affidavit that "'[p]rotocol' is when a member of an outside court visits a court during coronation. Protocol is a moment of public recognition of title when a member of an outside court is announced to the home court."

Whitley's affidavit further supports the notion that Rozanski's misgendering claims arose under circumstances that were outside the direct control of the ICRME, its Board, or any other defendant:

Related to Mr. Rozanski walking at ICS events or events at other Courts, each event and Chapter has its own protocols that are beyond the control of ICRME. Neither ICRME nor myself have attempted to block or express views related to Mr. Rozanski walking at events as Mr. Rozanski and/or Bettie Pages. As I understand it, ICRME has worked with Mr. Rozanski in an attempt to provide assistance with issues [that] have arisen.

Thus, it appears that the incidents about which Rozanski complains occurred in compliance with other courts' or chapters' rules.

Even if we ignore that possibility and accept Rozanski's allegations as true—that Whitley and the ICRME Board blocked Rozanski's protocol, or otherwise caused it not to be submitted—without more, we fail to see how such conduct goes "beyond all possible bounds of decency" and can be regarded as "atrocious, and utterly intolerable in a civilized community." …

Tiffaney A. Norton and Kristin A. Lillie (SGR, LLC) and Colin C. Campbell and Rachel A. Wright (Campbell, Wagner and Frazier, LLC) represent defendants.

The post Drama and Misgendering at the Imperial Court appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] School Contractor Allegedly Fired for Complaining About Drag Show for Students in Grades 7-12

[A federal court has allowed the contractor's claim to go forward, denying defendants' motion to dismiss (though of course the facts remain to be ascertained at trial or summary judgment).]

From Monday's decision by Judge Edmond Chang (N.D. Ill.) in Lopez v. Fasana:

[According to the Complaint,] April Lopez worked at Disney II Magnet High School as a chief engineer from October 2021 through April 2023. Although the school takes the name "High School," the school teaches students from Grade 7 through 12. She was not a direct employee of the Chicago Public Schools system; instead, she worked for Eco-Alpha, a subcontractor of Jones Lang LaSalle (the giant real-estate services company).

During the early morning of April 28, 2023, before students arrived at school, Lopez saw a poster for a drag show for students posted in a hallway. She said to one of her colleagues, "I cannot get on board with that." Vice Principal Matt Fasana overheard the comment and "expressed anger at her point of view." Then, later that morning, Lopez approached Fasana and directly "expressed her concern over having a drag show at a school with children as young as 12."

That conversation allegedly triggered a series of reports up the command chain—all on the same day, April 28—eventually leading to Eco-Alpha terminating Lopez's employment….

Lopez sued the school officials, and the court allowed the case to go forward:

Generally speaking, government employers may not retaliate against their employees (or contractors) for exercising their right to free speech. {The parties do not dispute that Lopez is a government contractor and her claim receives the same analysis as government employees.} … To plausibly state a claim for First Amendment retaliation, Lopez must allege that her speech was constitutionally protected, that she suffered an adverse action or that she suffered a deprivation likely to deter free speech, and that the protected conduct was at least a motivating factor behind the adverse action….

If Lopez was speaking pursuant to her official duties, then she has no retaliation claim, because that kind of speech—for First Amendment purposes—is considered to be government speech. If, on the other hand, she plausibly alleges that she was speaking as a private citizen on a matter of public concern, then the First Amendment may be implicated, and the next step of the evaluation is commonly referred to as Pickering balancing. At that step, the Court engages in "a delicate balancing of the competing interests surrounding the speech and its consequences," including whether the employee's interest in her speech is outweighed by "'the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.'"

[1.] On the threshold requirement, Lopez plausibly alleges that she was speaking as a private citizen, not pursuant to her official duties. On this question, courts consider the context of the speech, including whether the employee engaged in speech "ordinarily within the scope" of her employment, whether the speech was pursuant to government policy or to convey a government-created message, and who was the intended target of the speech. Put another way, did Lopez's not-on-board-with-that comment and the later conversation with Fasana "ow[e their] existence" to her responsibilities as the employee of a government subcontractor?

At the pleading stage, the only answer is no—and clearly so. Lopez was the chief engineer at the school. Nothing in the Amended Complaint suggests that a school engineer's duties include advising or opining on the substance of school programming. So Lopez's speech is not "ordinarily within the scope" of her engineer duties. Nor is there anything in the Amended Complaint hinting that Lopez was speaking pursuant to a school policy or seeking to convey a school-created message—instead, she expressed her own concern about the drag show for students as young as 12. Nor did Lopez connect the concern with her duties, for example, by refusing to work on the set up for the drag show….

Lopez's speech [also] did not owe its existence to her responsibilities as a public employee. It is true that she was in the school hallway and saw the poster while she was at work. But the Supreme Court has held that the test for official-duty-speech is not whether the speech "simply relates to public employment" or—importantly here—"concerns information learned in the course of public employment." … "[T]he mere fact that a citizen's speech concerns information acquired by virtue of his public employment does not transform that speech into employee—rather than citizen—speech. The critical question under Garcetti is whether the speech at issue is itself ordinarily within the scope of an employee's duties, not whether it merely concerns those duties." …

[2.] [T]he next question is whether Lopez also plausibly alleges that she spoke on a matter of public concern. "Whether an employee's speech addresses a matter of public concern must be determined by the content, for, and context of a given statement, as revealed by the whole record." Generally, when the speech of employees relates to "any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community," then they are speaking on a matter of public concern.

Here, Lopez's comments addressed a public issue: her opinion on what kinds of shows are appropriate for children to view in a school setting addresses a topic of public debate protected by the First Amendment. Indeed, the topic literally is about what should be shown in a public school. It is worth adding that the answer to the public-concern-or-not question does not depend on the viewpoint of the speaker. Consider, for example, if the hallway announcement had publicized the cancellation of a drag show due to parental concerns, and a school engineer expressed her concern to the vice-principal about bowing to that pressure. That speech would just as much touch on a matter of public concern as Lopez's. Based on the limited facts, Lopez spoke on a matter of public concern….

[3.] The final question is whether Lopez's claim survives Pickering balancing. The answer again is yes. Right now, confined to the facts in the Amended Complaint, the scales are tipped entirely in Lopez's favor. Her interest in expressing her opinion on what is appropriate for children to view in a school setting outweighs the needs of the school in carrying out the school system's duties.

Indeed (and not surprisingly), the Amended Complaint contains no allegations at all as to what disruption, if any, was caused by Lopez's speech. Reasonable inferences must be drawn in Lopez's favor, and nothing in the pleading suggests that any students heard her remarks. The overhead comment happened before students arrived. The allegation on the later conversation with Fasana says nothing about anyone else being present for it. There is nothing else about how the comment or the conversation otherwise affected the school day specifically or the school's operations more generally.

At this pleading stage, the Pickering balance is all one-sided in Lopez's favor. It is true that discovery might illuminate more about what Lopez said and more about the effect on the school. The Defendants could then renew their arguments at the summary judgment stage. For now, though, Lopez has more than plausibly alleged a claim for First Amendment retaliation….

And the court concludes that First Amendment protection is so clear (again, assuming all the facts are as Lopez has plausibly pleaded them) that the defendants cannot claim qualified immunity, at least at the motion to dismiss stage.

Seems quite right to me, at least given plaintiff's factual allegations (and the lack, at this stage, of any evidence of substantial disruption). Julie Herrera represents Lopez.

The post School Contractor Allegedly Fired for Complaining About Drag Show for Students in Grades 7-12 appeared first on Reason.com.

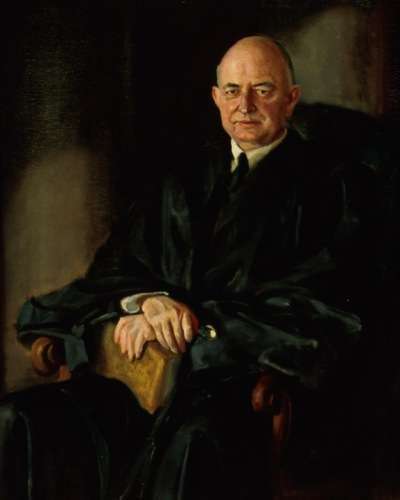

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: April 2, 1980

4/2/1980: Justice Stanley Forman Reed dies.

Justice Stanley Forman Reed

Justice Stanley Forman ReedThe post Today in Supreme Court History: April 2, 1980 appeared first on Reason.com.

April 1, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Lawsuit Over UC Berkeley's Alleged Toleration of Anti-Semitism …

[can go forward in part, a federal trial judge concludes.]

From yesterday's decision by Judge James Donato in Louis D. Brandeis Center, Inc. v. Regents of the Univ. of Cal.:

The FAC [First Amended Complaint] alleges a series of events unfolding over the course of several months on campus, which are said to have been precipitated by a campus culture hostile to Jewish students and professors. [See below for more details. -EV] The FAC says that these events were perpetrated by students who professed to oppose Zionism, but actually intended to discriminate against Jewish students and professors because they are Jewish. The FAC also alleges that Berkeley failed or refused to enforce its anti-discrimination policies as to its Jewish students and faculty in response to these events.

Taken as a whole, the FAC plausibly alleges disparate treatment with discriminatory intent and policy enforcement that is "not generally applicable." The FAC also plausibly alleges that Berkeley was deliberately indifferent to the on-campus harassment and hostile environment. Consequently, Brandeis's claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violations of the Equal Protection and Free Exercise Clauses of the U.S. Constitution will go forward, as will the Title VI claim.

It bears mention that the FAC repeatedly alleges that "Zionism is a central tenet of the Jewish faith." This raises concerns about whether Brandeis intends to call upon the Court to determine the articles of faith of Judaism. If so, a serious constitutional problem would arise. The Establishment Clause properly forbids the federal courts from saying what the tenets of a religion are. See, e.g., Our Lady of Guadalupe Sch. v. Morrissey-Berru (2020) ("The First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions 'to decide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of … faith and doctrine.'"). This proscription is particularly forceful when, as here, there is genuine disagreement on the matter.

Because the FAC as a whole plausibly alleges that Jewish students and professors were disparately treated because they are Jewish, the Court need not get into the issue now. The "Establishment Clause will be no worse for not having been so tested." It may be that the Court may properly determine whether Zionism is a sincerely held religious belief for some individuals, as circumstances might warrant, but the Court will not determine if it is a central tenet of Judaism.

The 42 U.S.C. § 1981 claim is dismissed. The gist of this claim is that members of the plaintiff organizations who are legal academics cannot contract with certain Berkeley student organizations that adopted a bylaw barring invitations to individuals espousing Zionist beliefs.

Brandeis does not dispute it must show standing to challenge the bylaw in connection with the Section 1981 claim. The complaint does not allege that any academic member has sought to contract with the organizations since adoption of the bylaw, been turned away on account of the bylaw, or has otherwise been put at a contractual disadvantage by the bylaw. The conclusory allegation that the academics "would welcome the opportunity to speak" is not enough. {Allegations that two academic members spoke to unnamed Berkeley student groups in the past does not plausibly allege an injury in fact, because there is not a non-speculative basis for reasonably inferring those unnamed groups adopted the bylaw or the members would speak or attempt to speak at such groups in the future.} …

Here's an excerpt from parts of the Complaint cited by the court (following the sentence "The FAC alleges a series of events unfolding over the course of several months on campus, which are said to have been precipitated by a campus culture hostile to Jewish students and professors"):

[3.] On February 26, 2024, a violent student mob succeeded in executing its plan to forcibly shut down a speaking engagement organized by Jewish students at Berkeley. Jewish students who had assembled to hear the speaker, and the speaker himself, were evacuated by police, who were unable to prevent the mob from smashing through glass windows, forcing their way into the event, terrorizing Jewish students, and physically assaulting them. Students screamed for help to the police. The police yelled to each other for help. Both the students and the police were overwhelmed. The mob's anti-Semitic motives were on full display, as when a rioter spat on a Jewish student and called him a "dirty Jew."

[4.] The organizers of the mob—Bears for Palestine, an officially recognized student organization—made no secret of their plans or intent. They openly advertised their plan to shut down the event. UC Berkeley was aware of their plans. Yet, not only did UC Berkeley fail to stop the mob from terrorizing and assaulting Jews, it has failed to take any meaningful action against Bears for Palestine since the riot. To this day, Bears for Palestine and other groups on campus continue to target and intimidate Jewish students, forcing them to conceal their Jewish identity, seclude themselves in their dorm rooms, or take circuitous routes around campus to avoid harassment.

[5.] Starting in early February, Sather Gate, a landmark that leads to the center of the UC Berkeley campus, has been the site of a blockade organized by a registered student organization. The blockade has closed down the middle of the gate completely to foot traffic, leaving only two smaller side paths available to the University at large. Although this blockade impedes all persons equally, Jewish students who have tried to pass have been singled out for harassment. They have been spat at, called ethnic slurs (including "dirty Zionist"), filmed as they pass, and even followed by the organizers of the blockade. Students have been singled out for such abuse if the protestors knew them to be Jewish or if they were wearing outward signs of their Jewish identity, such as Stars of David or yarmulkes. As a result of this intimidation, Jewish students have often stayed home or have been forced to take alternate routes to avoid Sather Gate. The blockade's effects have also been keenly felt by the disabled community. One Jewish graduate student who is blind repeatedly collided with protestors and nearly fell on multiple occasions while trying to make his way through the blockade. The University was repeatedly apprised that Jewish students are being harassed as a result of the blockade and that the disabled community's right to equal access was being denied. While the University committed to ending the harassment and ensure freedom of access through the gate, these issues continue.

[6.] Unfortunately, the harassment and obstruction that began at Sather Gate has spread. As of the filing of this Amended Complaint, student groups have occupied the area outside of Sproul Hall, an administration building on campus that houses the Registrar, Financial Aid, and other offices to which students require access. Because of the occupation, Jewish students report being unable to access the building and being harassed when they try to do so. One Jewish student was physically assaulted when he was observing the occupation. Another Jewish student who was wearing a Star of David was surrounded by masked protestors, who restricted his movement while telling him that "Zionists can go back to Europe." Despite being informed of the harassment, the University has once again failed to act. Indeed, the occupation has grown from 50 tents as of the week of April 21 to up to at least 175 at the time of this filing.

[7.] The post-October 7 eruption of anti-Semitic harassment was not a new development that caught the University off guard. To the contrary, anti-Semitism has been allowed to fester and grow on campus because UC Berkeley has chosen for years to ignore it. In 2016, a Brandeis University research study on anti-Semitism on college campuses found that over a third of students surveyed at UC Berkeley and three other University of California (UC) campuses perceived a hostile environment toward Jews on their campuses. And in 2017, Berkeley ranked fifth in a Jewish publication's list of the 40 worst colleges for Jewish students in the United States and Canada. That study noted that "Berkeley has long been accused of fostering an environment that can be unfriendly to Jews and Zionists." …

[9.] These bylaws—or any other mechanism—that treat Zionists in an inferior manner to non-Zionists are a guise for anti-Semitism. This reality is evident from the post-October 7 harassment of Jews at UC Berkely, where the harassers no longer hide their anti-Jewish animus behind the "it's just anti-Zionism" pretext. Jewish students who want to participate in the organizations that adopted the Exclusionary Bylaw have been constructively expelled or barred from joining. And legal scholars who are ready, able, and willing to speak to these organizations are prohibited from even competing for the opportunity to do so.

[10.] Although the Exclusionary Bylaw purports to target "Zionists," the message, as accurately perceived by Jewish students, is clear: Jews are not welcome. Moreover, while UC Berkeley administrators have publicly acknowledged the fundamentally anti-Semitic nature of the Exclusionary Bylaw, they have continually failed to take action to address it. To this day, student organizations on campus openly exclude Jews under the guise of excluding "Zionists."

[11.] The same anti-Semitic sentiment that animates the Exclusionary Bylaw recently spread beyond the walls of the University and invaded the home of the Dean of Berkeley Law, Erwin Chemerinsky. Less than a month ago, students from Law Students for Justice in Palestine—the same group responsible for drafting the Exclusionary Bylaw—disrupted a dinner Dean Chemerinsky was hosting to recognize and celebrate graduating students. The protestors refused to leave when asked to do so, violating not only University policy but numerous state trespass laws in the process.

[12.] Law Students for Justice in Palestine had planned their protest in advance, making no effort to disguise the anti-Semitic motives when they announced their protest on Instagram. There, they posted the e-mail invitation that Dean Chemerinsky had sent to students together with the dates the dinners would occur and a sign-up link to attend.. The same post featured a gruesome caricature of Dean Chemerinsky holding a blood-soaked knife and fork with the caption, "No Dinner With Zionist Chem While Gaza Starves." The image invoked the ancient anti-Semitic "blood libel" that Jews use the blood of non-Jewish children for ritual purposes. As Dean Chemerinsky acknowledged in response to the image, "I never thought I would see such blatant antisemitism, with an image that invokes the horrible antisemitic trope of blood libel and that attacks me for no apparent reason other than I am Jewish." {Law Students for Justice in Palestine ultimately took down the blood-stained caricature, replacing it with an identical image of Dean Chemerinsky, this time holding clean utensils.} As a result of this disruption, Jewish students did not attend additional dinners that Dean Chemerinsky hosted.

[13.] The unmistakable anti-Semitism animating this "anti-Zionist" protest was recognized by the University as well. Defendant Drake, issuing an official statement, recognized that "[t]he individuals that targeted [Dean Chemerinsky's dinner] did so simply because it was hosted by a dean who is Jewish," and explained that the protestors' actions "were antisemitic, threatening, and do not reflect the values of this university." Josh Kraushaar (@JoshKraushaar), X (Apr.11, 2024), https://x.com/JoshKraushaar/status/17.... Rich Leib, Chair of the University of California Board of Regents echoed the same statement and called the students' actions "deplorable." Jaweed Kaleem, 'Please leave!' A Jewish UC Berkeley dean confronts pro- Palestinian activist at his home, LOS ANGELES TIMES (Apr. 10, 2024), https://www.latimes.com/california/st...- pro-palestinian-activists ("The individuals that targeted this event did so simply because it was hosted by a dean who is Jewish. These actions were antisemitic, threatening, and do not reflect the values of this university.").

[14.] As this incident and others make clear, the student groups on campus responsible for this harassment equate Zionists with Jews or, at the very least, do not differentiate between the two. They single out Jewish students and faculty for harassment (even though non-Jews who associate with Jews may also be Zionists), and they target events organized by Jews or Jewish organizations. As the gruesome caricature of "Zionist Chem" made clear, they targeted him not because of his views on the policies of Israel—he is a frequent critic of the current Israeli government and avowed supporter of Palestinian rights. Rather, they targeted him because he is a Jew. Indeed, Law Students for Justice in Palestine—an organizing force behind the protests on campus—offers a "Tool Kit" to its supporters that equates Zionists with Jews, defining Zionism as "[t]he claim that all people worldwide who identify themselves as Jewish belong to a 'Jewish nation … and that this 'nation' has an inherent right to a 'Jewish state' in Palestine."

[15.] The University has acknowledged that what is occurring on campus violates school policy. It has acknowledged that the incursion onto a Jewish faculty member's property violated the student code of conduct. It has admitted that the blockade of Sather Gate violated the school's time, place, and manner restrictions on campus free speech. It has acknowledged that the February 26 rioters targeted Jews, despite the fact that the University's original statement in response to the riot omitted any reference to anti-Semitism. Dean Chemerinsky has even implicitly acknowledged that the Exclusionary Bylaw is anti-Semitic, given his recognition that Zionism is an integral part of Jewish identity for more than 90% of the Jewish students on campus.

[18.] Specific instances demonstrate that Israelis are also victims of the current hate on campus. A group of Israelis who came to observe the Sproul Hall occupation were harassed and physically assaulted. The protestors at the occupation told the Israelis that they should "Go back to Europe!," that "Zionists [should stay] out of Berkeley!" and "We will find the Zionists and kick them out of our classes!" Making clear that they equate Israelis with Jews (as well as Zionists), the protestors also called the Israeli students "Talmudic devils." One of the protestors approached one of the Israeli observers who was holding an Israeli flag, grabbed the flag, and then punched the observer three times in the head. The observer received medical care for his injuries.

[19.] A visiting Israeli professor had her invitation to return and teach at the school revoked given "everything that's happening on campus." The professor indicated that she had heard there was "enormous pressure from the faculty, especially from the furious master's degree students, not to bring anybody from Israel and not to hold courses dealing with Israel." …

The post Lawsuit Over UC Berkeley's Alleged Toleration of Anti-Semitism … appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "The Originalist Case Against Overturning Humphrey's Executor," by Lorianne Updike Schulzke

I was talking to Prof. Lorianne Updike Schulzke (who teaches at Northern Illinois and is visiting this semester at Yale), and she brought up some interesting thoughts on the President's supposed inherent constitutional power to dismiss independent agency officials. She was kind enough to pass along this quick summary; I'm not an expert on the field myself, but I thought it was worth passing along in turn:

Serious Originalists should pause before solidifying President Trump's control over independent agencies by overturning Humphrey's Executor. Yesterday the DC Circuit stayed the reinstatement of Gwynne A. Wilcox of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), potentially under the theory that Seila Law throws Humphrey's Executor into doubt.

Yet as I demonstrate in a paper just out in the Connecticut Law Review, Un-fathering the Constitution, the historical grounding of Seila Law in Madison's vision of executive removal is tenuous at best. In fact, more careful historical analysis demonstrates that Madison's vision should not dominate executive removal.

Further, this history shows that the original Congress anticipated a role for itself in limiting the president's removal power. If this history is to have any sway (and Originalism dictates that it should), Humphrey's Executor should be kept intact and greater power over independent agencies should not be granted to the Trump administration.

Congress began creating independent agencies in the 1880s, when they established the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate railroads. Since then, the President has made top appointments for such agencies, and Congress lower appointments according to Article II, Sec. 2 of the Constitution. Under Humphrey's Executor, the appointees who run these agencies have a quasi-legislative role (being set up by Congress), and therefore the president's ability to control and fire them is limited.

Humphrey's Executor stands in the way of Trump firing heads, especially multi-member heads, of independent agencies. The idea of Humphrey's Executor is that executive removal should be limited, or the president should be limited in his ability to remove heads of such agencies and wield control over them because they were established by Congress to be independent and create something of a check on executive power. The argument on the other side—called the theory of a unitary executive—is that independent agencies are not politically accountable and sweeping them under the executive (and overturning Humphrey's Executor) would make them so. Recently, this theory has gained support from liberal theorists.

Seila Law, decided by the Supreme Court in June of 2020, according to DC Circuit Judge Walker's concurrence filed in the Wilcox case yesterday, casts doubt on Humphrey's Executor. According to Walker, although Seila Law did not "revisit prior decisions" (Slip Opinion at 2), it did decide that independent agencies headed by a single head were removable by the President. By the same reasoning, multi-headed agencies like the NLRB would also be subject to removal.

Yet Seila Law is founded on the reasoning of Myers v. United States, which in turn is founded on the "Decision of 1789." In the Decision of 1789, the First Congress was suppose to have decided that the Constitution vested the power over removal of federal agency officials in the president.

Except that it didn't. Instead, the Myers' Court used Congressman Madison's arguments in favor of executive removal—and the First Congress' ability to set precedent for the Constitution—and interposed them as Congress' reasoning behind a very complicated vote and even more complicated Congressional debate.

A simple review of the votes of the 1789 Congress regarding the president's power to remove the Secretary of Foreign Affairs makes this clear. Twice, the First Congress rejected the language "to be removable by the President"—once by a vote of 34-20, and again by a vote of 31-19. The opposition to this language—and an interpretation of the Constitution vesting unfettered removal in the president—is clear.

After much debate, where some Congressmen expressed grave doubt over both Congress' ability to interpret the Constitution and placing strong removal power in the president, Congress approved the following language: "whenever the said principal officer shall be removed by the President" by a vote of 30-18.

The flip in at least 11 votes does not show that these Congressmen changed their beliefs, but that the language was more acceptable to them. Based on the debates leading up to this vote, a much more likely interpretation is that this language mustered a majority because 1) it did not mean Congress was assuming to itself a precedent-setting role in interpreting the Constitution and 2) the president's removal could be determined by either Congress or the Constitution. In effect, the vagueness of the language allowed for both interpretations.

More, at least a majority of the First Congress anticipated a role for Congress in determining removal of agency appointees. This does not translate into a strong case for executive removal OR a unitary executive, where independent agencies should all report to and be controlled by a president. It does leave open the possibility that independent agencies could report back to Congress rather than the president. Either way, this history is not good grounding for strong executive removal.

The reason why this "decision" has been interpreted as a decision—and one in favor of executive removal—is because of basic assumptions surrounding Madison. He is the presumed father of the Constitution, so his view of the Constitution and here, executive removal, is given more weight. Yet as I detail in Un-fathering the Constitution, this presumption is based more in fiction than fact. Madison does not a father make, especially in the singular sense, for three basic reasons.

First, Madison did not bring about the Constitutional Convention. This has long been known by historians, but not accepted by the public at large. He was a johnny-come-lately to the idea and didn't sign on till after the Annapolis Convention of 1786, likely convinced by Hamilton that it was worth putting his weight behind, which he did.

Second, Madison did not author the Virginia Plan. It was, instead, Virginia's Plan proposed and attributed throughout the Constitutional Convention to Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph who headed the quasi-committee of Virginia and Pennsylvania delegates who arrived on time to the Pennsylvania State House (now called Independence Hall) but before a quorum met. While Randolph held quill in hand, the Virginia Plan was likely dictated or worked out by constitution-writing veteran George Mason, who authored Virginia's famous (and much-replicated) Constitution of 1776. The biggest tell of Madison's non-authorship is shown in him nearly torpedoing the plan on day 1. On May 30, 1787, Madison raised the question of solidifying slavery in the representation calculus, something he would not do if the plan was his own (and certainly shows he did not win on major questions answered by the plan).

Third and perhaps most importantly, as shown by new analytics made possible by the Quill Project, Madison was not all that influential on the Constitutional Convention's floor. He came to the Convention with little national influence: Madison's correspondence shows he wrote to almost no one outside of Virginia before the Convention. Additionally, he was not picked for the Convention's most important committee, the Committee of Detail, tasked to come up with a draft of the Constitution, not asked to chair any of the four committees on which he sat, and though he was #3 in making the most proposals, he as 13th in terms of proposal success.

In the end, Madison emerges from the Convention depressed over his own and the Constitution's chance at success. This because the two proposals he was most passionate about, proportional representation in the Senate and a Congressional veto over state laws, failed. Madison later writes himself out of this funk when he, as Hamilton's #2 pick as co-author after Gouverneur Morris, writes 1/3 of the Federalist Papers. Although these papers are not immediately influential anywhere, they provide debating guides for himself in helping to secure Virginia's ratification.

Without a seat on the Supreme Court nor in Washington's cabinet and after losing his senatorial bid, Madison scrapes by in winning a seat in Congress by making a campaign promise to support a Bill of Rights. He makes good on this promise and cobbles other proposals together in drafting a Bill of Rights, which he champions through Congress thanks to help from Washington, but only just.

In all, Madison becomes influential later as a member of Congress, as the Federalist Papers are published as a two-volume book, and posthumously through his Notes on the Constitutional Convention. But he is not all that influential initially, and cannot faithfully fill the role of "Father of the Constitution." This becomes a problem when he is used to represent other Founders or when his interpretation is used inappropriately as the interpretation of the Constitution, as it has in executive removal jurisprudence, beginning with Myers v. United States.

Madison's views on executive removal in the First Congress should not be the lynchpin upon which executive removal jurisprudence, including Humphrey's Executor, should turn. Instead, the Court and advocates who take Originalism seriously should be careful to weigh other, more diverse sources to determine the public meaning of the president's power to remove agency officials such as those serving on the NLRB.

I'd of course be glad to post contrary arguments on this as well (and I know some of my cobloggers have already written on this).

The post "The Originalist Case Against Overturning Humphrey's Executor," by Lorianne Updike Schulzke appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Important Questions for Boeing's CEO at Tomorrow's Senate Commerce Committee Hearing

[Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg should explain whether Boeing continues to plan to plead guilty to conspiring to defraud the FAA, or whether it will attempt to shirk its responsibility for the deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history.]

Tomorrow, Senator Ted Cruz has scheduled a hearing entitled "Safety First: Restoring Boeing's Status as a Great American Manufacturer." Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg is scheduled to testify about steps Boeing has taken to address safety issues that have arisen in recent years. Foremost among these issues is Boeing's conspiracy to defraud the FAA about the safety of its 737 MAX aircraft—a proven criminal conspiracy which directly and proximately led to two crashes of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft.

Like Senator Cruz, I truly hope that Boeing will, in its next chapter, be restored to its status as a great American manufacturer. But moving onto that next chapter is not possible until Boeing concludes its current chapter. Over the next few weeks, Boeing's leadership will decide how it will conclude the criminal case that has been pending against it for more than four years. Boeing's decision will shed considerable light on whether it truly committed to again becoming a great and responsible manufacturer.

As is well known, Boeing defrauded the FAA about the safety of its 737 MAX aircraft. In January 2021, Boeing entered into a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) with the Justice Department, in which it admitted the crime. In exchange for the Government's agreement to defer prosecution, Boeing promised to address safety issues connected with the 737 MAX and, more broadly, its internal safety procedures.

I am representing (on a pro bono basis) some of the two crashes victims' family members. As I have blogged about before (see here, here, here, and here), the DPA was concluded in violation of the Crime Victims' Rights Act because the parties (the Justice Department and Boeing) kept that agreement secret from the 346 families who lost loved ones in the two crashes. Indeed, Senator Cruz wrote a powerful amicus brief supporting the families' position that they represented "crime victims" of Boeing's conspiracy. Senator Cruz explained that "Boeing engaged in criminal conduct that defrauded government regulators and left hundreds of people dead in preventable plane crashes.… This is not a mine-run fraud case where some low-level employee lied or committed a technical violation; it is a long-running conspiracy that directly led to some of the worst air travel disasters of the 21st century."

During the DPA's three-year term, Boeing failed to deliver on its promises to improve safety processes. In May, 2024, Boeing's failures led the Justice Department to declare that Boeing had breached its DPA obligations, setting up the issue of how to resolve the pending conspiracy charge. Last summer, Boeing agreed to plead guilty. But after the victims' families objected to the proposed "sweetheart" deal, Judge O'Connor rejected the proposed plea agreement for various reasons. Judge O'Connor then directed the parties to explain how they intended to proceed. Whether Boeing intends to plead guilty to the charge, go to trial, or try to do something else is currently pending.

During the last week, news reports have suggested that Boeing is now lobbying the Justice Department to cut some kind of new deal. According to these reports, Boeing wants an even sweeter deal in which it would not have to even acknowledge that it committed a crime, much less that its senior leadership engaged in a "long-running conspiracy that directly led to some of the worst air travel disasters of the 21st century." If these reports are true, Boeing is now seeking to shirk its responsibility for its past crime and simply jump to the next chapter in its corporate history.

Following these reports that Boeing was waffling on its previously expressed plan of pleading guilty, the judge handling the case (Judge Reed O'Connor in the Northern District of Texas) sua sponte set a trial date in June to finally resolve the case. Boeing is, of course, free to pursue its own interests as it sees them. But it is important to highlight that Boeing seems to want to have it both ways—one the one hand, appearing to be contrite about causing the crashes, while seeking to skate through the criminal justice system without admitting its guilt on the other.

For example, last summer, at another Senate hearing, outgoing Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun turned to apologize directly to the family members in the gallery who lost loved ones in Boeing crashes and said:

I would like to speak directly to those who lost loved ones on Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. I want to personally apologize, on behalf of everyone at Boeing. We are deeply sorry for your losses. Nothing is more important than the safety of the people who step on board our airplanes. Every day, we seek to honor the memory of those lost through a steadfast commitment to safety and quality.

This made for good theater—while the cameras were rolling during Calhoun's testimony. But Calhoun's statement appears to have been carefully crafted to avoid acknowledging the full scope of Boeing's crime. A few lowlights are worth recounting, which are all clearly established in an earlier congressional report, internal Boeing emails, an SEC investigation, and Boeing's own admissions.

Boeing's conspiracy involved its Chief Test pilot and others who deceived the FAA into believing that there was no need to include information about a new, powerful software system on the 737 MAX (called MCAS) because MCAS could only activate during

rare situations—not during routine flight operations. By concealing MCAS's expanded operational scope from the FAA, Boeing defrauded the FAA and obtained a low-level (less rigorous level) of training for pilots transitioning to fly to the new 737 MAX aircraft. And pilots flying the 737 MAX aircraft were not given relevant information about the scope of MCAS and how to respond to improper MCAS activation—which could produce a crash.

Tragically, this was no mere theoretical possibility. On October 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610, a Boeing 737 MAX, crashed shortly after takeoff into the Java Sea near Indonesia. All 189 passengers and crew on board died due to improper MCAS activation, which the pilots did not respond to because they had not been trained in proper responses. After the Lion Air crash, Boeing investigators quickly identified MCAS as the cause. But rather than be forthcoming about what had happened, Boeing attempted to focus attention on the foreign pilots as the accident's central cause. However, they did not disclose that one of Boeing's own test pilots in late 2012 had failed to recover from uncommanded MCAS activation in a flight simulator. This was a fundamentally important event that Boeing chose not to share with the FAA or its MAX customers.

While Boeing knew the deadly truth about MCAS, it concealed that truth from pilots and the public. For example, on November 13, 2018, then-Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg appeared on the FOX Business Network and claimed that Boeing had been "very transparent on providing information," the MCAS procedure was already "part of the training manual," and the "737 MAX is a very safe airplane." These were false statements—all designed to keep Boeing's stock price from declining further and to buy time for Boeing's engineers to continue working behind he scenes to fix the MCAS problem. In other press releases, Boeing failed to mention that it had identified an ongoing "airplane safety issue" associated with MCAS and that it feverously working on a planned software redesign. Indeed, Boeing did not mention MCAS at all. Instead, at the specific direction of CEO Muilenburg, Boeing lied to the world, saying that "[a]s our customers and their passengers continue to fly the 737 MAX to hundreds of destinations around the world every day, they have our assurance that the 737 MAX is as safe as any airplane that has ever flown the skies."

A stunning example of how Boeing hid the truth is how it refused to answer pointed questions from Ethiopian Airlines pilots (information that the capable legal team I am working with pried out of Boeing through civil discovery). Shockingly, on December 1, 2018, the Ethiopian Airlines Head of Flight Operations emailed Boeing with three questions from the group's pilots about its directions to pilots in the event of uncommanded and erroneous MCAS activation. Senior Boeing officials declined to answer two out of the three questions. If Boeing had responded to each of the questions instead of refusing to answer them, the pilots' ability to respond to the situation it described would have been full explained, likely preventing the crash of flight ET 302 on March 10, 2019 … and saving 157 lives. But answering the questions would have revealed the truth about the serious MCAS problem—imperiling Boeing's stock price.

At the Senate Commerce Committee hearing tomorrow, I hope that the Senators will explore these questions. The key issue now is whether is Boeing still apologizing and willing to admit it criminally caused 346 deaths? If so, how does it explain recent news reports that its lawyers are working behind the scenes to cut another deal that would avoid any accountability for these losses? Has Boeing considered the devastating harm that it will cause to the 737 MAX victims' families if it manages, through high-powered lawyering and back-room deal cutting, to avoid pleading guilty to its deadly crime?

Perhaps such a deceitful maneuver will lead to some short-term advantage. But in the long run, such an outcome would signal that Boeing will do whatever it takes to avoid admitting a mistake, even a deadly one. That path does not seem calculated to return Boeing to the status of being one of America's great manufacturers. The Senators holding tomorrow's hearing should ask CEO Ortberg whether he plans to have his company admit in court the deadly crime it has committed.

Update: I changed the punctuation in the subtitle.

The post Important Questions for Boeing's CEO at Tomorrow's Senate Commerce Committee Hearing appeared first on Reason.com.

[Evan Bernick] Lash's Last Stand

[Evan Bernick's second in a series of guest-blogging posts: Part II of a critique of an important defense of the constitutionality of Donald Trump's executive order on birthright citizenship.]

Yesterday I published a critical review of a document that Kurt Lash described several weeks ago as a "completed article." Within several hours, I learned that it is not in fact complete. Shortly after my critique went live, Lash posted a revised draft. The latest revisions aren't substantial. But readers should be aware that I'm firing on a moving target and that eventually, I'll have a full-length critique of his (actually) completed article.

I'll finish up with Lash's contrarian take on birthright citizenship by doing three things. First, I'll critique his bizarre treatment of the children of enslaved people and Confederates. Then I'll put to rest a claim that Lash makes about the importance of parental allegiance to the few exceptions to birthright citizenship recognized by the time of the Fourteenth Amendment's ratification. Finally, I'll discuss Lash's treatment of Indian law—roughly, the law defining and regulating the relationships between the government of the United States and that of 575 federally recognized Native nations and their citizens. Although Lash has never written anything substantial about Indian law, Indian law is the source of a crucial analogy which he uses to argue for an exception to birthright citizenship that did not exist in 1868. I'll show that the analogy doesn't work.

Loyal Slaves? Loyal Confederates?

As Lash recognizes, the most damning defect of allegiance-based accounts of the Citizenship Clause which turn upon reciprocal consent (on the part of citizen to allegiance and the sovereign to protection) is that they cannot explain how the Clause performed the function that literally everyone (even DOJ lawyers defending the anti-birthright EO) agrees that it was designed to perform: the nullification of Dred Scott v. Sandford. Neither enslaved people nor their children consented to be kidnapped and imported as property into the United States, and the United States did not consent to the foreign slave trade either following a congressional ban in 1808. No theory of reciprocal consent can, I think, overcome the Dred Scott problem, and I think Lash agrees.

But recall that Lash does link birthright citizenship to parental allegiance and conceptualizes allegiance as loyalty to sovereign power. Just how is it that people forced into the United States and subjugated by the laws of enslaving states can be determined to be loyal to the United States? Why would they (in Lash's terms) have "fidelity towards" sovereign power of that nature?

Lash's solution to this apparent problem is an extraordinarily strong presumption in favor of loyalty. How strong? Strong enough that Lash can assert that "[n]othing about that context suggests, much less involves proof of, refused or counterallegiance."

Seriously? It seems obvious that any presumption in favor of the loyalty of enslaved people to the sovereign on whose soil they were enslaved would be unwarranted. What of the countless souls who tried to flee slavery? Were those who agreed (as Frederick Douglass initially did) with William Lloyd Garrison that the Constitution of the United States was a covenant with hell, loyal to the United States? Was Douglass loyal to the United States when he offered a qualified defense of killing slavecatchers who were empowered by federal law? Was he disloyal, then loyal? These are puzzles that Lash created for himself.

I applaud Lash for uplifting the general strike through which enslaved laborers emancipated themselves before Lincoln proclaimed their freedom. But the more straightforward explanation for the citizenship of the children of enslaved people does not depend upon this momentous act of collective liberation. It is the conventional one in Citizenship Clause scholarship: Children who are born in the United States and subject to its unmediated sovereign power are citizens.

So, too, does Lash struggle to explain the Republican consensus in favor of the citizenship of the children of Confederates. If any parents manifested their disloyalty towards the United States, it would be Confederate parents. Lash responds by labeling the Confederacy a conspiracy and thus subsuming it within a broader category of "criminality." Of course, conspiring to overthrow a government is a crime, but it is more. So, it seems odd to say (as Lash does) categorically that criminality "has no necessary relationship to refused or counter allegiance," and is not sufficient to "rebut the presumed natural allegiance of a child born in the United States." Again, why complicate things with loyalty? On the conventional account, these children are subject to the unmediated sovereign power of the United States—day in, day out, through its lawmaking, enforcement, and adjudicatory institutions—so they are subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

I assume some originalist readers will regard what follows as an inadmissible "policy" argument. (But see Sai Prakash's intriguing recent argument for the interpretive significance of consequences in Founding-era law.) Still, I can't pass over it entirely. On Lash's account, Reconstruction Republicans chose to codify a constitutional rule that did not exclude the children of Confederates, serial killers, or mob bosses from birthright citizenship but which did exclude the children of undocumented immigrants. Parental criminality as such does not determine a child's birthright citizenship, nor does parental insurrection against the government. But voluntary parental refusal to express loyalty to the United States through the specific means of compliance with laws governing entry into its "sovereign territory" does. As Lash seems to recognize at some level, normatively, it seems problematic to effectively punish children for parental crimes. It seems perverse to punish them for parental border crossing but not for parental insurrection or mass murder.

But we don't have to rely upon our own moral intuitions to be skeptical that the Citizenship Clause was designed to yield such an outcome. Again, we have compelling reasons to think that abolitionists and Republicans attached less moral significance to border crossing than Lash does when it comes to determining whether the children of people who cross borders illegally are to be denied citizenship. Amanda Frost has shown how abolitionist birthright freedom treated a parent's illegal conduct in crossing the border from an enslaving to a free state as irrelevant to the status of the child: the child was free if born in a free state. If Lash is right, Republicans responded to this experience by turning back towards lineage-based citizenship once they held constitutional power. That seems unlikely.

More Exceptions, More Problems

Yet another problem for Lash is the absence of any widely recognized exception to birthright citizenship for the children of unlawful entrants at the point of ratification. This problem is not fatal; it is certainly possible that the Citizenship Clause communicated to the ratifying public a principle which incorporated not only extant exceptions to the birthright citizenship rule but other exceptions that were sufficiently like them. Still, it's also possible that it did not, and it is problematic for Lash to so quickly assume that it did and grasp for analogies.

Suppose, however, that there was indeed a delegation to the future. What was the scope of that delegation? Lash submits that long-recognized exceptions are best explained by his loyalty-based, parent-derived concept of allegiance. Parents who have what Lash calls "counter-allegiance" or who "refuse" allegiance to the United States bear children who lack loyalty.

Lash spends significant time with only three exceptions to birthright citizenship of any practical relevance that had any evidentiary support at all in 1868. The first exception concerned the children of diplomats and their families and staff. The second exception concerned the children of members of occupying armies. And the final exception excluded the children of American Indians from birthright citizenship. None of these exceptions turned on parental loyalty to the United States.

As Michael Ramsey has detailed, the children of diplomats and their families and staff were excepted from birthright citizenship because of the nature of international relations and the legal infrastructure that surrounded them. For most purposes, people in the active service of a foreign nation did not receive the protection of the United States and owed no allegiance to its laws. Any obligations were consensual and strictly delimited. The exception for the children of members of occupying armies was grounded in the lack of practical power that sovereigns have over people in their territory during an invasion. That it did not turn on parental allegiance is evident from the fact that the loyalty of those under occupation did not determine whether their children are birthright citizens. Chris Mirasola points out that what matters is whether the occupation is only temporary or results in the formal annexation of territory, as well as when the child is born.

Finally, the exclusion of American Indians from birthright citizenship is no great mystery and it certainly has nothing to do with parental loyalty to the United States. Republicans, like the abolitionists before them, swore by Worcester v. Georgia and affirmed the sovereignty of Native nations. Sovereignty in Worcester was linked to territory, and leading Republicans made plain their understanding that Tribal citizens on Tribal land, despite being within the boundaries of the United States, did not ordinarily experience U.S. power over their internal affairs. They could not be sued, they could not be prosecuted, they could not be bound by sovereign U.S. power—except to the extent of treaty-based consent. Once again, not parental or any other kind of loyalty but exposure to the unmediated sovereign power of the United States was decisive.

One last note: Lash mentions but devotes no significant discussion to a long-acknowledged exception to birthright citizenship that's been raised by others. This exception applied to birth on foreign public vessels within U.S. territorial waters. Once again, parental allegiance doesn't help us. The United States and other nations treated foreign public vessels as floating parts of foreign nations, even though they might have chosen to do otherwise. So, they didn't subject them to their unmediated sovereign power. That was that.

There is no urgent need for a novel unified theory of the Citizenship Clause, much less this one. The above exceptions are well known and have been long studied by scholars who have traced their common-law origins and documented their development during the antebellum period. None of them resemble the exclusion for which Lash contends in nature or scope, and none of them require Lash's ungainly allegiance framework.

Lost in Indian Country

Lash's case for the exclusion of the children of unlawful entrants turns upon an analogy to the Indian exception. He claims that unlawful entrants are like what he terms "unaligned Indians" who unlawfully left lands reserved to them by treaty, in violation of treaty terms. In both cases, the problem is that the would-be entrant has "willfully decline[d] to present themselves to any sovereign authority and intentionally and intentionally refuse to be subject to the laws regarding entry into the sovereign territory of the people of the United States." In neither case ought their children be entitled to birthright citizenship.

It is true that Republicans left open the possibility of U.S. citizenship for Tribal citizens who renounced their Tribal ties, which would put their children in a different jurisdictional situation. But that doesn't make parental loyalty to the United States determinative of a Native child's birthright citizenship, any more than it would that of a child of a foreign ambassador who had retired from service and become a naturalized U.S. citizen. What ultimately matters for birthright citizenship purposes is U.S. sovereign power over the child, in both cases. The focus on power is evident in the exchanges upon which Lash relies.

Consider these two paragraphs, which appear midway through Lash's discussion of the allegiance of "voluntary unlawful entrants":

During the debates over the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Mr. Doolittle reminded his colleagues about the need to exclude the "wild Indians of the plains." Joint Committee Chair William Pitt Fessenden echoed this concern wondered whether the amendment might include unaligned Indians since they fell at least arguably within the "jurisdiction" of the United States. Trumbull could not deny that, as a technical matter, the United States exercised a degree of jurisdiction over all such Native Americans. Antebellum treaties were express on this matter. However, the language of the Citizenship Clause demanded persons born in the United States be "subject to the complete jurisdiction thereof." To be "completely subject" to the jurisdiction of the United States involved "complete allegiance" to the same. As Trumbull summarized, "[i]t is only those persons who come completely within our jurisdiction, who are subject to our laws, that we think of making citizens."

The reason citizenship for unaligned Indians was inappropriate had little if anything to do with their allegiance to a different sovereign. The problem was a failure of these groups to be positively place themselves subject to the United States. This is why Indians who had left their tribe but refused to present themselves for formal assimilation were not appropriate candidates for citizenship. In terms of the Citizenship Clause, proof that a child was born into such a familial context of "refused allegiance" rebuts the prima facie presumption of natural loyalty to the country of birth.

By "unaligned Indians" Lash means Indians who were "living outside of tribal authority." Lash says that they did not have sufficient allegiance to be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States because they failed to "positively place themselves subject to the United States" through "formal assimilation." But Indians who were Tribal citizens also were not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States—Trumbull said so repeatedly. He insisted that Tribes with which the U.S. treated and members of Tribes with which the U.S. did not have treaties "are not" subject to U.S. jurisdiction and that "[w]e do not exercise jurisdiction over them."

Why, then, did Trumbull speak of "complete allegiance" and "complete jurisdiction"? In fact, he did not speak of "complete allegiance"—this is one of many occasions in which Lash creates confusion by putting quotation marks around phrases that he coined himself, right next to phrases that do appear in the sources. And Trumbull illustrated (in a passage that Lash does not discuss) what he meant by "complete jurisdiction" with specific examples of lawmaking, enforcement, and adjudicatory power to which Native people were not subject in Indian country without treaty-based consent:

Can you sue a Navajoe [sic] Indian in court? Are they in any sense subject to the complete jurisdiction of the United States? By no means. We make treaties with them, and therefore they are not subject to our jurisdiction. If they were, we would not make treaties with them. If we want to control the Navajoes, [sic] or any other Indians of which the Senator from Wisconsin has spoken, how do we do it? Do we pass a law to control them? Are they subject to our jurisdiction in that sense? Is it not understood that if we want to make arrangements with the Indians to whom he refers we do it by means of a treaty?

Once again, the conventional wisdom works just fine: Indians were subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to the extent that they were subject to the unmediated lawmaking, enforcement, and adjudicatory authority of the United States.

Nothing that Trumbull or any other credible source says about the extent of U.S. power over Tribal citizens in Indian country describes a reality that remotely resembles that which undocumented people and their children experience. Regardless of the reality on the ground, according to Trumbull, Tribal citizens on Tribal land could not be sued, prosecuted, or bound without treaty-based consent. Denying the children of undocumented people citizenship subjects them to all that power without affording them any protection, contrary to the basic allegiance-protection framework that undergirds Lash's theory. It's what Trumbull said, it was widely covered, and it was common—the stuff of public meaning.

In a since-deleted tweet, Lash came close to recognizing the fatal shortcomings of his own analogy. Here it is:

Although the framers of the Citizenship Clause expressly drafted the provision to address situations involving Native Americans leaving their quasi-foreign reservations and living in the United States without authorization (in "the wild") some scholars insist we cannot reasonably view this history as informing the original meaning or contemporary application. Originalists do not have the option to engage in such anti-historical squeamishness.

I'm not sure which scholars Lash had in mind. But I am certain that within the borders of the United States, neither undocumented immigrants nor their children live on territory that can reasonably be described as "quasi-foreign" and beyond the unmediated sovereign power of the United States. I am certain that the Reconstruction Framers repeatedly, publicly proclaimed that members of Native nations, whether bound to the U.S. by treaty or not, were beyond that power in Indian country. I am certain that they remembered the Trail of Tears and the birthright freedom movement. And I am certain that Lash does not mention any of this.

In the deleted tweet, as in the underlying article, Lash presents himself as a resolute realist, challenging a squeamish scholarly consensus. There is, however, nothing realistic about the picture that he paints of the Citizenship Clause. He ought to have taken more time—to read, to talk to people who have studied the subjects under discussion for years, to circulate more widely.

What was the rush?

The post Lash's Last Stand appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] Dear Harvard: You Have $50 Billion in the Bank - Use It Now

[Isn't one of the reasons you have built up an endowment is to protect your integrity as an institution of higher learning from political assault? ]

In a statement released yesterday, the Administration announced that it would be undertaking …

"… a comprehensive review of federal contracts and grants at Harvard University and its affiliates … as part of the ongoing efforts of the Joint Task Force to Combat Anti-Semitism. The Task Force will review the more than $255.6 million in contracts between Harvard University, its affiliates and the Federal Government. The review also includes the more than $8.7 billion in multi-year grant commitments to Harvard University and its affiliates to ensure the university is in compliance with federal regulations, including its civil rights responsibilities. Today's actions by the Task Force follow a similar ongoing review of Columbia University. That review led to Columbia agreeing to comply with 9 preconditions for further negotiations regarding a return of canceled federal funds."

[NB: While many people have been describing Columbia as having "settled" its dispute with the Administration, this announcement makes clear that the Administration views the agreement with Columbia as having settled only the "preconditions for further negotiations regarding a return of canceled federal funds." I.e., "You're not off the hook yet, and we have not yet decided to 'return … canceled federal funds'"]