Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 127

April 7, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Can A Federal Court Force The President To Negotiate With A Foreign Leader To Obtain Return of Alien?

[Noem v. Garcia comes to the Supreme Court.]

Earlier today, Solicitor General Sauer filed his first emergency application with the Supreme Court. concerns the District Court's order to return an alien who was deported to a prison in El Salvador. The statement lays out the stakes:

On Friday afternoon, a federal district judge in Maryland ordered unprecedented relief: dictating to the United States that it must not only negotiate with a foreign country to return an enemy alien on foreign soil, but also succeed by 11:59 p.m. tonight. Complicating the negotiations further, the alien is no ordinary individual, but rather a member of a designated foreign terrorist organization, MS-13, that the government has determined engages in "terrorist activity" or "terrorism"—or "retains the capability and intent to engage in terrorist activity or terrorism"—that "threatens the security of United States nationals or the national security of the United States." The order compels the government to allow Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia to enter the United States on demand, or suffer the judicial consequences.

At a superficial level, I understand the district court's order. The judge found that Garcia was unlawfully deported, and therefore sought the return of the alien. Isn't this simply the sort of injunction that courts issue to the executive branch all the time? Not quite. Here, obtaining the return of the alien would require the President to successfully negotiate the release of the alien from a foreign leader. Even if the President makes this request, the foreign leader is under no obligation to comply. I am seriously doubtful this is the sort of power that the judiciary has.

The SG makes this argument quite forcefully:

Even amidst a deluge of unlawful injunctions, this order is remarkable. Even respondents did not ask the district court to force the United States to persuade El Salvador to release Abrego Garcia—a native of El Salvador detained in El Salvador— on a judicially mandated clock. For good reason: the Constitution charges the President, not federal district courts, with the conduct of foreign diplomacy and protecting the Nation against foreign terrorists, including by effectuating their removal. And this order sets the United States up for failure. The United States cannot guarantee success in sensitive international negotiations in advance, least of all when a court imposes an absurdly compressed, mandatory deadline that vastly complicates the give-and-take of foreign-relations negotiations. The United States does not control the sovereign nation of El Salvador, nor can it compel El Salvador to follow a federal judge's bidding. The Constitution vests the President with control over foreign negotiations so that the United States speaks with one voice, not so that the President's central Article II prerogatives can give way to district-court diplomacy. If this precedent stands, other district courts could order the United States to successfully negotiate the return of other removed aliens anywhere in the world by close of business. Under that logic, district courts would effectively have extraterritorial jurisdiction over the United States' diplomatic relations with the whole world.

The government concedes that Gacia's removal was in error, but maintains that the Supreme Court should recognize the sovereignty of a co-equal branch of government.

But, while the United States concedes that removal to El Salvador was an administrative error, see App., infra, 60a, that does not license district courts to seize control over foreign relations, treat the Executive Branch as a subordinate diplomat, and demand that the United States let a member of a foreign terrorist organization into America tonight.

Judges have ordered planes to be turned around and negotiations to be had with foreign leaders. I realize that Trump is breaking many norms, but judges are streamrolling through norms as well.

What does Chief Justice Roberts do here? The John Roberts of 2005, who vigorously ruled in favor of the Bush Administration with regard to Guantanamo Bay, would grant this application in a heartbeat. But the John Roberts of 2025 has been changed by decades of compromise.

I think the most likely outcome is that Roberts follows the lead of Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson on the Fourth Circuit: deny the application, but "clarify" that the District Court can only require the President to "facilitate" the return of the alien. Here is what Wilkinson wrote:

I would deny the request for a stay of the district court's order pending appeal. We deal here with what I hope is the extraordinary circumstance of the government conceding that it made an error in deporting the plaintiff to a foreign country for which he was not eligible for removal. In this situation, I think it legitimate for the district court to require that the government "facilitate" the plaintiff's return to the United States so that he may assert the rights that all apparently agree are due him under law. It is fair to read the district court's order as one requiring that the government facilitate Abrego Garcia's release, rather than demand it. The former seems within the trial court's lawful powers in this circumstance; the latter would be an intrusion on core executive powers that goes too far.

Like in the USAID case, the Court would ostensibly deny relief, but still offer instructions to the lower court--yet another advisory opinion.

I still remain confounded that the best the Bush Administration had to replace Rehnquist was Roberts, Wilkinson, or Luttig. Our bench is so much deeper today.

Update: Chief Justice Roberts granted a temporary administrative stay, and called on the Respondent to file a brief tomorrow (Tuesday):

Order entered by The Chief Justice: Upon consideration of the application of counsel for the applicants, it is ordered that the April 4, 2025 order of the United States District Court for the District of Maryland, case No. 8:25-cv-951, is hereby stayed pending further order of The Chief Justice or of the Court. It is further ordered that a response to the application be filed on or before Tuesday, April 8th, 2025, by 5 p.m. (EDT).

Almost immediately, Respondents filed their response. They were ready to go.

The post Can A Federal Court Force The President To Negotiate With A Foreign Leader To Obtain Return of Alien? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jim Lindgren] A Computational Error May Be Driving the Size of the Tariffs

[Tariffs #2: AEI says that the Administration Seems to Have Used the Wrong Number in its Formula]

In an American Enterprise Institute article, Kevin Corinth and Stan Veuger claim that the Administration made a mistake when figuring the "reciprocal" tariffs that are the basis for its the schedule of tariffs released last week:

The formula for the tariffs, originally credited to the Council of Economic Advisers and published by the Office of the United States Trade Representative, does not make economic sense. The trade deficit with a given country is not determined only by tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers, but also by international capital flows, supply chains, comparative advantage, geography, etc.

But even if one were to take the Trump Administration's tariff formula seriously, it makes an error that inflates the tariffs assumed to be levied by foreign countries four-fold. As a result, the "reciprocal" tariffs imposed by President Trump are highly inflated as well.

The alleged error is a technical one:

The Trump Administration assumes an elasticity of import demand with respect to import prices of four, and an elasticity of import prices with respect to tariffs of 0.25, the product of which is one and is the reason they cancel out in the Administration's formula.

However, the elasticity of import prices with respect to tariffs should be about one (actually 0.945), not 0.25 as the Trump Administration states. Their mistake is that they base the elasticity on the response of retail prices to tariffs, as opposed to import prices as they should have done. The article they cite by Alberto Cavallo and his coauthors makes this distinction clear. The authors state that "tariffs [are] passed through almost fully to US import prices," while finding "more mixed evidence regarding retail price increases." It is inconsistent to multiply the elasticity of import demand with respect to import prices by the elasticity of retail prices with respect to tariffs.

Correcting the Trump Administration's error would reduce the tariffs assumed to be applied by each country to the United States to about a fourth of their stated level, and as a result, cut the tariffs announced by President Trump on Wednesday by the same fraction, subject to the 10 percent tariff floor. As shown in Table 1 [in the AEI post], the tariff rate would not exceed 14 percent for any country. For all but a few countries, the tariff would be exactly 10 percent, the floor imposed by the Trump Administration.

The post A Computational Error May Be Driving the Size of the Tariffs appeared first on Reason.com.

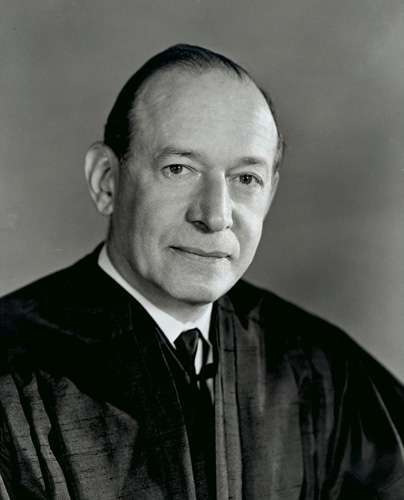

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: April 7, 1969

4/7/1969: Stanley v. Georgia decided.

The Warren Court (1969)

The Warren Court (1969)The post Today in Supreme Court History: April 7, 1969 appeared first on Reason.com.

April 6, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] "The Trump Administration's Unconstitutional Hate Mail to Harvard," by Prof. Genevieve Lakier (Chicago)

I've worked with Prof. Lakier on various projects recently, and have been much impressed with her analyses (as well as by her scholarship more generally). I'm therefore delighted to pass along her thoughts on the Administration's letter to Harvard University, with which I generally very much agree:

On April 3, officials in the Trump administration sent a letter to Harvard University, apparently in response to efforts by university administrators to open a "dialogue" with them about the funding cuts the administration had several days earlier announced it was considering making. The letter responded to the university's attempt to talk by outlining some, but possibly not all, of the changes the university would have to make in order to preserve the university's "continued financial relationship with the United States government."

The changes the letter asks for are sweeping, if also very much lacking in specifics. The letter demands, among other things that Harvard "review[]" and make "necessary changes" to academic programs and departments that "fuel antisemitic harassment" to "improve [their] viewpoint diversity and end ideological capture." Harvard also has to "consistently and proactively enforce its existing disciplinary policies, ensuring that senior administrative leaders are responsible for final decisions." It must impose a "comprehensive mask ban" on campus, and hold student protestors and student groups more strictly accountable for violation of the institutional time, place and manner rules.

It must cease all DEI programming on campus, as well as adopt a "merit-based" system of admissions and hiring (as opposed to what Harvard has now?). Harvard also has to "make meaningful governance reforms … to foster clear lines of authority and accountability, and … empower faculty and administrative leaders who are committed to implementing the changes indicated in this letter." It must in other words, reallocate power within the institution to those who agree with the administration's ideological agenda.

These demands are breathtaking in their ambition. The administration appears to be asking Harvard to change not only how it regulates speech and conduct on campus but how it performs its core educational and research functions, how it determines who constitutes the university community in the first place, and how it self-governs—although, again, without giving Harvard clear direction in any of these respects.

These demands are also very likely unconstitutional. As I, along with fifteen other constitutional law scholars argued in a public statement several weeks ago, the decision by the Trump administration to terminate $400 million in funding to Columbia was not only unjustified on statutory grounds but very likely violated the First Amendment by chilling, and pushing Columbia to suppress, protected expression. The same is true here, even though in this case, the administration hasn't actually cut Harvard's funding (yet!) but merely threatened to do so.

It doesn't matter that the administration has so far merely threatened to pull Harvard's funding, not actually done it, because—as the Supreme Court made clear just a year ago, in National Rifle Association v. Vullo—threats can violate the constitution too when they promise legal or regulatory harm in an effort to coerce private speakers or speech hosts like Harvard into censoring themselves or suppressing other people's speech. As the Court put it in Vullo, quoting an earlier Second Circuit opinion, "although government officials are free to advocate for (or against) certain viewpoints, they may not encourage suppression of protected speech in a manner that can reasonably be interpreted as intimating that some form of punishment or adverse regulatory action will follow the failure to accede to the official's request."

It is very hard to read the Harvard letter as doing anything else but "reasonably intimating"—indeed, very strongly intimating—that adverse regulatory action will follow the failure to accede to its demands. In a recent case, the Ninth Circuit held that Elizabeth Warren did not violate the First Amendment when she sent a letter to Amazon that expressed displeasure at the fact that a book that contained Covid-19 misinformation was listed on the retailer's best seller lists and hinting at possible legal consequences if Amazon did not change how it promoted this kind of material. The Ninth Circuit found that the letter did not violate the First Amendment because the letter did not "intimate[] that [Warren would] use her authority to turn the government's coercive power against the target if it does not change its ways" but merely expressed concern about Amazon's actions. In this case, by contrast, it is impossible to read the Harvard letter as doing anything other than making crystal clear that the administration will use its coercive power of the purse to punish the university if it does not change its ways.

There also can be no question that the demands the administration is making of Harvard are intended to suppress protected expression, of various kinds. To avoid the loss of federal funds, Harvard will have to refrain from advocating for, or empowering others to advocate for, the viewpoint that diversity, equality, and inclusion are important educational and social values. It will have to change how it oversees faculty research and teaching, and what kinds of scholarly viewpoints it hires and promotes. And it will have to suppress student speech and association, including core political expression, more severely than it has chosen to do so far—or at least it will have to promise to do so. Fundamentally, the letter uses the stick of funding cuts to undermine every single one of the "four essential freedoms"—the freedom "to determine for itself … who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study"—that Justice Frankfurter, in concurring opinion in Sweezy v. New Hampshire, identified as core to the institutional autonomy that the U.S. constitution guarantees to universities.

It may be the case that some of the hiring practices that the letter requires Harvard to change are unprotected because they constitute, say, the kind of racial discrimination prohibited by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Similarly, some of the student expression that Harvard will have to promise to regulate more strictly may not be protected because it constitutes involve fighting words, or discriminatory harassment prohibited by Title VI.

But there can be no doubt that much of what the administration is targeting here is protected speech and association, even under the most expansive interpretations of both Title VI and Title VII. After all, neither statute would ever give the government the power to decide when and how academic departments are ideologically captured, or insufficiently diverse in their viewpoints. Similarly, it is very difficult to see how Title VI would ever give the government the power to force universities like Harvard to strictly enforce their time, place, and manner rules, or ensure that senior administrators are responsible for disciplinary decisions. And that is to say nothing of the other demands, such as the demand to get rid of all DEI programming.

The fact that it lacks the power to simply legislate these changes is obviously an important reason why the Trump administration is instead attempting to use the stick of funding cuts to force Harvard to make them on its behalf. But the fact that the administration is proceeding in this informal manner, by negotiating with Harvard rather than ordering it to act, does not make its actions any less inconsistent with the First Amendment. If anything, it makes them only more troubling.

After all, as the example of Columbia University vividly demonstrates, the businesses that are typically targeted by these kinds of threats (including, evidently, non-profit educational businesses) will often choose to comply rather than fight them in court even when they have a very good chance of succeeding in that litigation. This is because these institutions will often believe, rationally enough, that it is more advantageous to maintain good relationships with the officials who oversee their operations than to defend the speech interests of the third parties (in this case, students and faculty) who use their property and resources to speak.

And when, as here, it is unclear exactly what is required to make the government happy, businesses targeted by these kinds of threats may restrict even more speech than officials expressly demand of them, to avoid any risk of retribution down the line. (In one case, for example, retailers accused of disseminating pornography who faced far milder threats of governmental retribution than Harvard faces now removed not only issues of Playboy and Penthouse magazines from their shelves, but also "out of an abundance of caution," also temporarily suspended the sale of American Photographer and Cosmopolitan magazines because they contained photographs of women with bare breasts.)

The result is that informal government threats and sanctions can create what Justice Brennan, in Bantam Books v. Sullivan, described as an "informal system … of regulation" that is not governed by the ordinarily speech-protective rules that govern the formal system but instead restricts whatever speech government officials want private actors to restrict, without judicial oversight. Powerful actors in the system can, in effect, sacrifice other people's speech interests in order to save their hide. And for this reason, the Court has recognized that this kind of "do it or else" approach to speech regulation creates, as Justice Brennan put it, "hazards to protected freedoms markedly greater than those that attend reliance upon the criminal law" and categorically prohibited it. (For a fuller version of this argument, see here.)

The fact that this kind of tactic can succeed in coercing even very rich and powerful institutions to comply demonstrates how effective, and dangerous, it can be as a tool of speech suppression. It also makes it essential to call the government out when it engages in this kind of "jawboning against speech." Even if it never actually cuts any of the university's money, the letter that the Trump administration sent to Harvard poses a very serious threat to the free speech values that Harvard itself has insisted is essential to its institutional mission.

Hopefully the fact that complying with the government's demands will require Harvard to abandon the values it has argued are "uniquely important" to it as an educational institution will mean that, in the end, the university will not choose the path of appeasement that Columbia has chosen so far but will instead defend its own institutional expressive interests, as well as those of its student and faculty, in court. If Harvard does give in, however, we should all recognize what it is doing—namely, enabling, and thereby encouraging, the unconstitutional actions of an administration that appears hellbent on destroying the independence of American higher education, one rich ivy-covered institution at a time.

I might have come to these results slightly differently; for instance, I'm not positive that Frankfurter's freedom of a university "to determine for itself on academic grounds … who may be admitted to study" entirely makes sense in the funding context (where, even beyond bans on race and sex discrimination, a state might be allowed to, for instance, condition funding for private universities on those universities' maintaining preferences for in-state students). But these are minor differences; in general, I think Prof. Lakier's analysis is correct and important.

The post "The Trump Administration's Unconstitutional Hate Mail to Harvard," by Prof. Genevieve Lakier (Chicago) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: April 6, 1938

4/6/1938: United States v. Carolene Products argued.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: April 6, 1938 appeared first on Reason.com.

April 5, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Justice Jackson's Dissent in Department of Education v. California Treats The Federal Government Like Just Another "Party"

[The dissenters no longer treat the federal government with solicitude as a coordinate branch of government.]

When I was a 2L, I saw Justice Scalia give a speech to the Baltimore Federalist Society Chapter. Someone asked him whether the Solicitor General should be considered the "Tenth Justice." Scalia scoffed at the question, and said that there were only nine Justices. Still, as I recall, Scalia acknowledged that the federal government was a special litigant before the Supreme Court. Indeed, the Solicitor General is the representative of a coordinate branch of government.

Historically at least, the Solicitor General, received some special treatment. The SG had the highest number of cert petitions granted. Moreover, the Solicitor General is uniquely skilled at opposing certiorari by finding, and in some cases inventing, vehicle problems. The SG routinely obtains leave to participate in oral argument. These requests are rarely granted for any other party. The Court often invites the SG to offer views on a particular case. Critically, however, when the SG files an emergency motion with the Court, the Justices have treated the case with urgency.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court split 5-4 in Department of Education v. California. The majority seems to have treated the Solicitor General's application with the sort of comity that was due to a coordinate branch of government. Indeed, it remains unclear to me why this deference was not granted to the even-more-pressing USAID case.

Justices Jackson and Sotomayor, however, would not have afforded the federal government such treatment. Rather, the dissenters would have apparently treated the incumbent administration as just another "party." To be sure, the dissenters identified several legal errors in the majority opinion, but at bottom, the disagreement concerned whether the executive should get any relief on the emergency docket, or instead wait for a regular appeal like any other party.

Consider how Justice Jackson described the United States as just another "party" seeking emergency relief:

I, for one, think it would be a grave mistake to permit parties seeking equitable emergency relief not only to make an inadequate showing of interim harm but also to seek relief on the basis of their concerns about issues that can be addressed later, in the ordinary course.

Yet, here we are. Instead of leaving the lower court judges alone to do the important work of efficiently adjudicating all of the parties' legal claims, the Supreme Courthas decided to enter the fray.

The Government has now gotten this Court to nullify clearly warranted interim injunctive relief, deflecting attention away from the Government's own highly questionable behavior, all without any showing of urgency or need. I worry that permitting the emergency docket to be hijacked in this way, by parties with tangential legal questions unrelated to imminent harm, damages our institutional credibility.

Department of Education v. California, as the name suggests, is a conflict between the federal government and the states. The lower courts issued emergency rulings against the federal government, even as the United States argues these cases belong in a different court. The only court that can set aside these rulings is the United States Supreme Court. Justice Jackson would have the case percolate in the normal course, and perhaps return to the Supreme Court through the certiorari process. That may be fitting for the leisurely pace of Justices who sit for about about thirty weeks per year, with a healthy summer break, but it disregards an urgent plea from the federal government.

I am still struck how Justice Jackson refers to subject matter jurisdiction, sovereign immunity, and venue as "tangential legal questions." She later refers to these bedrock principles as "shiny objects."

It is thus small wonder that the Government has chosen not to press its merits arguments in this emergency application. See n. 2, supra. What better way to avoid prompt consideration of the Plaintiff States' serious claims about the unlawful arbitrariness of the Government's conduct than to demand that jurists turn away from those core questions and entertain a host of side issues about the power of the District Court on an "emergency" basis? Courts that are properly mulling interim injunctive relief (to prevent imminent harms and thereby facilitate fair adjudication of potentially meritorious claims) should be wary of allowing defendants with weak underlying arguments to divert all attention to ancillary threshold and remedial questions. Children, pets, and magicians might find pleasure in the clever use of such shiny-object tactics. But a court of law should not be so easily distracted.

The Solicitor General has made an art form out of raising arguments based on sovereign immunity, jurisdiction, and venue. But Justice Jackson sees these arguments as a diversion. I wrote an entire book about how the Obama Administration consistently rewrote the Affordable Care Act, and the only conceivable defense was that no one was injured by these acts, so there was no standing. At the time, I heard only crickets. What we are seeing here is not new.

It seems pretty clear to me that the dissenters still refuse to "normalize" the Trump Administration. Perhaps Justice Jackson cannot embed talismans in her opinion to ward off evil, but she can still deny the government the traditional presumption of regularity. And, she concludes, it harms the Court's "institutional credibility" to grant the government such comity. I disagree. Quite the opposite, the Court weakens itself in immeasurable ways by refusing to treat this administration as the duly-elected coordinate branch that it is. Let law professors argue whether this President is entitled to the presumption. Judges should stay in their own lane.

The post Justice Jackson's Dissent in Department of Education v. California Treats The Federal Government Like Just Another "Party" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Steven Calabresi] President Trump's New Tariffs Are Unconstitutional

[They violate the major questions doctrine set forth by the Roberts Court and must be stopped by a nationwide injunction.]

I have agreed with President Trump on most policy questions, and I defended him ardently against the despicable campaign of lawfare waged against him by former President Biden and by the Left more generally. I greatly admire the President and believe strongly that the President has the power to remove all federal officers and employees who do not either work for Congress or for the Article III federal courts. I will defend in amicus briefs his power to fire FTC commissioners, NLRB commissioners, Inspectors General, and civil service personnel.

I must, however, respectfully disagree with President Trump's imposition of sweeping tariffs, which are huge tax increases, this week because I think he lacks the statutory and constitutional authority to raise tariffs in the way and to the degree he has done. Under Article I, Section 8, Clause 3, it is Congress that has the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations and not the President, and under Article I, Section 8, Clause 1, it is Congress and not the President that has the power to impose duties, imposts, and excises—better known as taxes.

The American Revolution was fought over the principle that there should be "no taxation without representation." While the President does represent the American people, Congress represents them as well. The Constitution gives Congress and not the President the critical voice in the imposition of taxes on the importation of goods.

While Congress has delegated substantial discretion to the President to raise tariffs when there are emergencies, which Congress may do under U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corporation, 299 U.S. 304 (1936), the tariffs, which President Trump has imposed, especially this week, raise "the major question" of whether tariffs on this scale ought to be imposed as: (1) a big source of the federal government's revenue (partly replacing for this purpose the income tax), or (2) in response to currency manipulation or (3) in response to the inclusion in the price of foreign goods of value added taxes or (4) to deal with the types of emergencies, which President Trump's new tariffs are said to be imposed to address. The supposed emergencies of currency manipulation or the burying of value added taxes in the price of foreign goods, which President Trump has pointed to, have existed for many decades—yet during that time no such tariffs were announced or thought to be necessary. Congress has never addressed these "major questions," and until and unless Congress approves of such taxes/tariffs, the President lacks the power to impose them.

Congress has frequently delegated to the President the power to impose reciprocal tariffs when another nation restricts American exports unfairly. It has never delegated to the President the power to answer the major public policy question as to whether our system of taxation should finance the government to a greater degree through tariffs than through income taxes, which are far less of a burden on the middle class and the poor than are tariffs. Moreover, Congress has long been aware of the phenomenon of currency manipulation and the burying of value added taxes in the price of foreign goods, yet it has never delegated to the President the power to impose tariffs to counter those phenomena.

The foreign affairs emergencies where Congress has delegated power to impose tariffs, or sanctions, are those like Russia's invasion of Ukraine, or Iran's effort to develop nuclear missiles. Congress has known of the "emergency" of the erosion of America's manufacturing base for decades, and yet Congress has ratified many free trade deals with Canada, Mexico, Central America, and South Korea. It is simply implausible as a matter of statutory construction for President Trump to interpret the word "emergency" in federal law as encompassing the erosion of our manufacturing base—just as it was implausible for President Biden to interpret the term pollutant as including carbon dioxide in his attempt to use his presidential power to enact national climate change rules.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has on several occasions, and particularly during President Biden's Administration, struck down executive branch and presidential action based on vague statutory authority addressing "major questions" that only Congress has the power to address. The "major questions doctrine" is a commonsense approach to statutory interpretation, not a canon of statutory construction. The Roberts Court has only formulated the "major questions doctrine" in recent years, and it has not yet applied it in the context of foreign affairs, but there is no inherent reason why the doctrine ought not to apply in that context where Congress's core powers to tax and to regulate foreign commerce are implicated. In my opinion, no President has the legal authority to raise tariffs in the way, and on the scale, in which President Trump has done.

The "major questions doctrine" was deployed by the Roberts Court to stop President Biden from doing an end run around Congress by: (1) imposing unilaterally hugely expensive climate change rules without congressional approval; (2) requiring all workplaces to make their employees get Covid shots without specific congressional approval; (3) declaring a nationwide moratorium on the eviction of renters by property owners because of Covid without getting congressional approval; and (4) excusing billions of dollars in unpaid student loan debt without getting congressional approval. These Supreme Court decisions striking down unilateral White House lawmaking were correct, and they are based on a correct earlier precedent that the Food and Drug Administration cannot regulate cigarette use on the ground that nicotine is a drug.

These decisions all reflect the commonsense idea that there are some matters that are just so important that Congress must decide them. There is a reason why Article I, which addresses congressional power, is so much longer than is Article II, which addresses presidential power. The Framers thought and wanted for all of the truly big policy choices to be made by Congress subject to a presidential veto.

While it is true that presidents have broad emergency powers, especially in time of war, there are nonetheless limits even to that power, as President Truman found out when the Supreme Court held that he could not on his own nationalize the steel industry to avert a strike during the Korean War. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952). Justice Robert Jackson in that case wrote that the President's powers to deal with foreign powers emergencies are at their weakest when Congress has delegated to the President a power in one context, but not in another. Here, Congress has delegated to the President the power to impose sanctions on Russia and Iran for real foreign policy reasons, but it has not delegated the power to impose tariffs because of the erosion of our manufacturing base. The grant of power in the one instance makes quite telling the lack of a grant of power in this instance. Notwithstanding my agreement with President Trump on many matters, the tariffs/taxes he just announced are in my opinion unlawful.

The New Civil Liberties Alliance (NCLA) has just filed a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of President Trump's new tariffs, Emily Ley Paper, Inc v. Trump (N.D. Fla.), on behalf of plaintiffs who import goods from China and are directly harmed by the unlawful tariff/taxes. The District Court should enter an immediate nationwide injunction suspending the Trump tariffs, and the Supreme Court should hold those tariffs/taxes to be unconstitutional as soon as possible.

The post President Trump's New Tariffs Are Unconstitutional appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Compendium of Evan Bernick Guest-blogging Posts on Birthright Citizenship

[Links to all of his posts compiled.]

Many thanks to Prof. Evan Bernick for his insightful guest-blogging posts on birthright citizenship over the past week. For convenience, here are links to all of his posts, gathered in one place:

1. "Evan Bernick, Guest-Blogging About Birthright Citizenship" (post introducing Evan and compiling links to some of his work; written by Ilya Somin)

2. "88 Problems for Kurt Lash"

3. "Lash's Last Stand"

5. "The Dred Scott Challenge or: Why Constitutional Law is Not a Game"

The post Compendium of Evan Bernick Guest-blogging Posts on Birthright Citizenship appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: April 5, 1982

4/5/1982: Justice Abe Fortas dies.

Justice Abe Fortas

Justice Abe FortasThe post Today in Supreme Court History: April 5, 1982 appeared first on Reason.com.

April 4, 2025

[Orin S. Kerr] Jack Goldsmith on the Edward Martin Nomination

["The Case for Non-Confirmation"]

Over at his Executive Functions substack, Jack Goldsmith urges the United States Senate to refuse to confirm Edward Martin for U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia. From the post:

Martin even in his temporary role has proven to be the most openly politicizing and weaponizing figure in the most politicized and weaponizing department in our history. If the Senate confirms him, it will be directly responsible for his foreseeably abusive actions as U.S. attorney. . . .

Martin had a long career in Missouri politics but has no prior prosecutorial experience. He popped up on the D.C. radar screen when he tweeted at 2:53 p.m. on Jan. 6, 2021, that he was "at the Capitol right now" and added that there was a "[r]owdy crowd but nothing out of hand."

Martin later represented Jan. 6 defendants. Yet after his appointment as interim U.S. attorney on Jan. 20, 2025, he dismissed charges against his own client, thus serving simultaneously as prosecutor and defense counsel in probable violation of his ethical duties.

Martin's other abusive activities as acting U.S. attorney are well known. Here is a partial list:

He fired career prosecutors involved in Jan. 6 cases. He threatened to "chase … to the end of the Earth" not just people who had acted unlawfully, but "simply unethically"—a threat that is beyond his authority to make and is itself unethical. He has made "a practice of sending threatening letters announcing vague 'inquiries' into figures he feels have crossed Trump in some way, including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Rep. Robert Garcia (D-Calif.)." He is groundlessly using his office to question whether president Biden issued lawful pardons in his final days in office. He threatened Georgetown Law School over its DEI program without citing any legal principles. He conceives of his role as U.S. attorney primarily as one of "Trump's lawyers" fighting to "protect his leadership," as he made clear in connection with the case brought against the government by the Associated Press. He has engaged in other conduct unbecoming of a federal prosecutor on social media.It is unclear whether Martin acted in these instances with pure political goals; or whether he does not understand the role of a U.S. attorney; or whether he simply cannot meet basic professional standards. Any of these explanations is disqualifying; all three could be true. . . .

I cannot think of any U.S. attorney nominee in my lifetime who embodies [Justice Robert Jackson's worries about federal prosecutors' more, and who is more likely to abuse federal prosecutorial power, than Edward Martin. And this wolf comes as a wolf. Martin has wielded prosecutorial power recklessly and openly while serving in a temporary role, during his Senate audition period; his actions will surely grow much more menacing if he is confirmed.

As they say, read the whole thing.

The post Jack Goldsmith on the Edward Martin Nomination appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers