Larry Gottlieb's Blog: The Insights Blog, page 4

June 27, 2022

“If I Perceive It, It’s Real”

Some back-and-forth with my readers about various relevant topics

Some back-and-forth with my readers about various relevant topicsA while back, I posted a reference to a passage from my book, Hoodwinked: Uncovering Our Fundamental Superstitions. It reads: “How can the physical world be what is real when it requires perception in order to come into being?”

I made that statement in the context of inquiring into the meaning of quantum physics. Most of my readers seem to accept that quantum theory correctly predicts how the physical world behaves. In fact, if it didn’t do that, we wouldn’t have transistors, cellphones, and computers.

However, quantum theory also presents a powerful enigma: it speaks to the likely results of any observation of the world, and not to the world itself. In this way, it describes the world in a way that conflicts mightily with our common sense understanding. So much so that the question inevitably arises: what does all this mean? Lacking a satisfying answer, most physicists subscribe to an approach that boils down to: “just shut up and calculate.”

That post on the role of perception gave rise to the following conversation.

Jeff:

If it wasn't real, there would be nothing for you to perceive. The world existed for billions of years before humans first existed to perceive anything.

Larry Gottlieb, Author

Hey Jeff! It's not that the world isn't real... it's that our idea of the world is a conditioned interpretation. We humans always think that the world is senior to ourselves, existing more-or-less as we perceive it to be before we got here and long after we're gone.

I like to say that we think the world is an "is," as in "it just is that way." My assertion, rather, is that the world is more a "shows up as," as in "the world shows up for me as a safe place, whereas it shows up as a dangerous place to others..."

My contention is that we don't experience the world directly... our interpretation of sensory input, our description of the world, always stands in between. As a result the world, whatever it is, is and will always remain mysterious and unfathomable to us humans.

Jeff:

Larry Gottlieb, Author. Agreed. What we perceive is not what animals, birds or fish perceive. It's the three blind men and the elephant.

L.W.:

One idea I’d like to suggest is that the world exists apart from our perception of it. Obviously when a sentient being dies, the world doesn’t go out of existence. It is slightly changed, overall, very slightly, in most cases. However HIS world does cease to exist.

When I say exist, I mean in an ever changing, evolutionary way.

I sort of understand the double slit experiment, and have heard of Schrodinger and Heisenberg. I’m not a materialist nor a determinist.

Larry Gottlieb, Author

Yes, I agree... the world does exist. However, what we call the world is a description, an interpretation of sensory data which has been conditioned by our experience of the past, by our habits of thought, by our beliefs, and by what we were told when we were young. All we have is our interpretation of what we see, and we all mistake that interpretation for what is actually there. As for what is actually there, quantum theory says it's a field of weighted possibilities, aka probabilities. It tells us that what's required is observation in order to select one of those probable outcomes of the observation and make it actual. One interpretation of that result is that there are an infinitude of universes available for perceiving, and we choose one every moment of our lives. That's my take on the subject. Thanks for your comment!

L.W.:

I am not as learned as you and mostly I think we agree. I like the the idea that the world consists of weighted probabilities, but observation by whom or what? Would observation of a squirrel, trilobite or stegosaurus do the trick? Surely it doesn’t have to be a human. I completely accept that we do not know the world in its profound complexity- least of all me. I love talking about though.

Larry Gottlieb, Author

Albert Einstein wondered if a "side-long glance from a mouse would suffice." In my book Hoodwinked, I make the case that human Being (capitalization intended) needs to be redefined in light of quantum mechanics. I explore our belief, shared by virtually everyone who's ever been alive, that our being-ness begins and ends at a boundary called our skin... in other words, that a human being is an object among other objects. I hope you'll read the book and then challenge my argument to the contrary if you feel that's needed. I too love talking about this stuff!

L.W.:

Larry Gottlieb, Author, I doubt that human BEING has anything to do with the overall existence or operation of the universe.

It does, of course, have an enormous influence on the existence and operation of OUR universe. But the rest of the universe really really doesn’t care.

Larry Gottlieb, Author

Once again, if you'll read the book you'll see my argument that the Universe DOES care and that's one way of expressing why we're here. I'm not saying I'm right... just that I think I make a pretty good argument. But it takes me 220 pages to do it, not a couple sentences on Facebook.

June 13, 2022

What About the Quantum Physics Observer Effect?

I’ve been speaking and writing for about a decade now about, among other things, the relevance of quantum physics to the inquiry about what a human being really is. With respect to this work, a number of people have asked if I’m talking about the so-called “observer effect.”

In general terms, the observer effect is the established fact that observing a situation or phenomenon necessarily changes it. This idea shows up in a range of contexts, from psychology to computer science and electronics to quantum physics. Let’s take a very brief look at how the effect shows up in these areas.

How does the observer effect show up?In psychology, observer effect is the name given to the phenomenon that occurs when the subject of a study alters their behavior because they are aware of the observer's presence. This results in incorrect data: the researcher records behavior that is not the way the subject actually behaves when not under observation.

In computer science, the “observer effect” names a situation in which a software bug seems to disappear or alter its behavior when one attempts to study it. Studying the behavior of software usually requires using other software as a probe, and the probe becomes part of the software being studied, thus altering its behavior.

In electronics, by attaching a measuring device of some type to a system being measured, small amounts of capacitance, resistance, or inductance may be introduced. Though good instruments have very slight effects, in sensitive circuitry these can lead to unexpected failures, or conversely, unexpected fixes to failures.

A deeper look into the nature of human beingIt turns out that the “observer effect” shows up in an entirely different and much more powerful way when you take a deeper look into the nature of human perception and its relationship to the world around us.

We most commonly think of “human being” as name given to a particular creature, an animal with certain unique characteristics, one of which is consciousness of self. In terms of this definition, the human animal is the object and the consciousness of self is an attribute of that particular animal.

It is possible, however to consider human Being in an entirely different way, in which the human animal is the manifestation of a particular degree of consciousness of self. In other words, once a self becomes conscious of itself, it appears in physical manifestation as the human animal. This amounts to an inversion of the usual conceptual relationship between the world and the conscious observer.

Classically, the conscious observer is contained within the world an as object among many other objects. In the inverted view, the world is contained within the consciousness of the observer as an interpretation of sensory data delivered to the brain. The form we call the human animal then is the end result of the interpretive mechanism which takes optical, tactile, and other sensory data and produces a multisensory picture in the brain. It is this picture to which we refer when we use the term “human being.”

The observer effect in the context of consciousnessHow, then, does the “observer effect” show up when the world of objects is recognized to be the result of an interpretive process?

The default or classical understanding of the observer effect is the phenomenon of changing the situation from the way it was before being observed to something different. But when the world and all its components are viewed as the result of interpretation by the observer, the observer effect is no longer an agent of change but rather an agent of creation. The observer brings the world he/she is experiencing into being through interpretation. There is no situation prior to its observation, and therefore there can be no effect on the situation in the usual sense.

This inversion of the relationship between the world and the observer has numerous benefits. Psychologically, it puts the observer in a position of personal power with respect to the world of one’s experience which is unavailable in the classical view. Most of us have found that changing the world is difficult at best. However, interpretations can be changed or replaced, and thus the world as a product of interpretation can be changed as well.

An Aside for Quantum Physics EnthusiastsIn quantum physics, we find the idea of the wavefunction. The wavefunction is a description of the building blocks of nature (electrons, protons, and so on) in which each particle is represented by the probability of any particular result of a measurement on some aspect of the particle. For example, the particle’s position in space is not fixed, but a measurement can result in a number of positions each with a probability of finding it there.

The process by which a measurement of one of these aspects appears to select one possibility from among them all is called the collapse of the wavefunction. The phrase “collapse of the wavefunction” refers to the fact that the normal state of an unobserved particle is what’s called a superposition of possible states (possible outcomes of any yet-to-be-performed experiment on or measurement of the particle), and the actual experiment or observation causes this superposition to disappear. We know this because we never observe a physical object, no matter how small, in more than one state at a time. This collapse is very hard to explain when the particle is considered to exist as it is, whether it’s being observed or not.

However, when what we think of as the particle is the result of a process of interpretation of sensory data (augmented of course by detectors or other scientific devices), it’s the interpretation, or the description we so derive, that contains the collapse. In this “interpretive-centered” view, the particle, the wavefunction, and the experimental apparatus are all parts of a description of the world. And this description is not the world itself.

What follows is a demonstration of how the observer effect shows up in physics.

The Double-Slit Experiment in Physics - The Quantum Physics Observer Effect

Actual result of the double-slit experiment (energywavetheory.com)

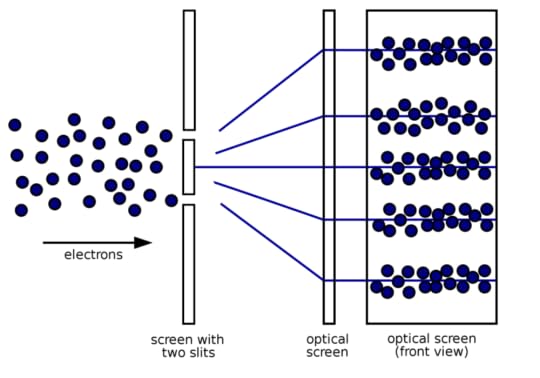

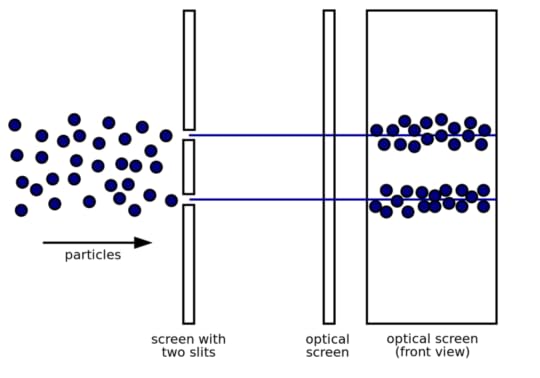

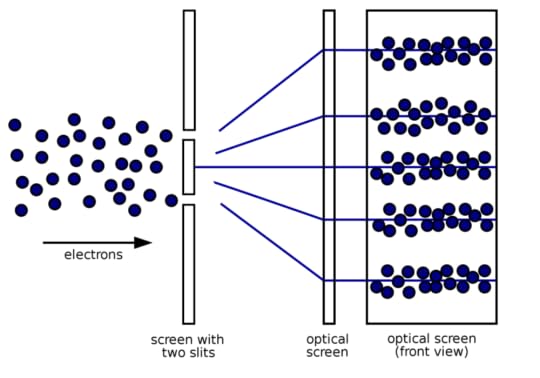

One very interesting use of the term “observer effect” is in physics, specifically the quantum physics observer effect. The famous double-slit experiment demonstrates the wave nature of particles. So-called fundamental particles, such as electrons, when made to impinge on a screen with two slits, appear to pass through both slits at once. This is obviously impossible from a classical perspective. However, examining the results of sending these particles through the double-slit apparatus shows this behavior as an interference pattern on an optical screen. This behavior is impossible from a classical perspective.

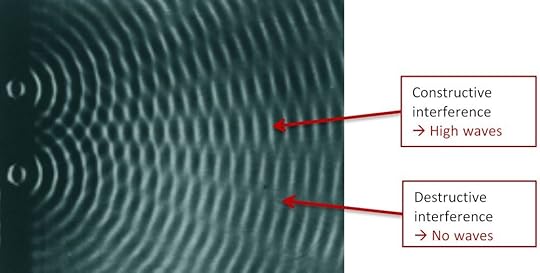

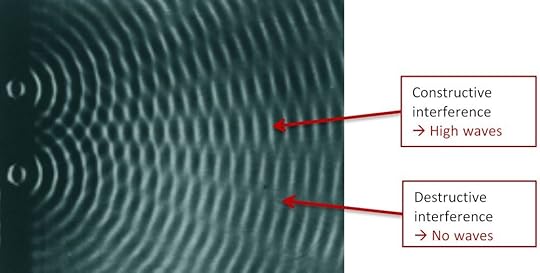

Double-slit with water (wiki.anton-paar.com)

The interference pattern resulting from the double-slit experiment is the same result you get if you allow water waves to impinge on a barrier that contains two slits: at some distance behind that barrier, the waves coming from the slits will interfere with one another, causing them to add to each other at some places and at other places cancel each other out. This phenomenon is called interference, and it’s interpreted as conclusive evidence of wave behavior.

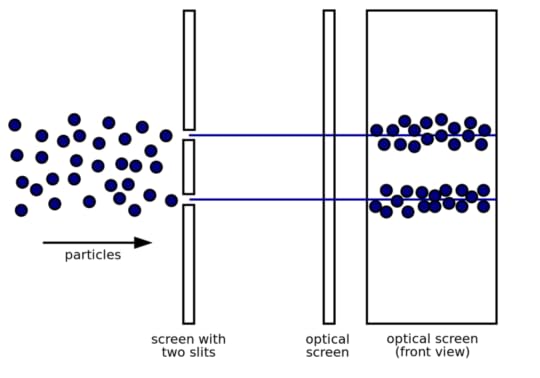

The classically-expected result (commons.wikimedia.org)

The observer effect enters into the double-slit experiment in the following manner: the way we look at the world causes us to assume that a physical particle will only pass through one of the slits. After all, every object we’ve ever observed at our human scale follows only one trajectory through space and time.

Intuitively, we expect to be able to measure which slit the particle went through by firing it at the screen with two slits and looking at the resulting image on the optical screen.

However, it turns out that any attempt to measure which slit the particle “actually” passes through destroys the interference pattern and produces the classically-expected result of all the particles striking the screen directly behind one of the slits. This measurement by an observer and his/her equipment effectively removes the wave aspect from the particle! For those of us who think about quantum physics, this is a stunning result!

ConclusionThe world you and I experience is an interpretation of sensory data. As to the question of what the world might be beyond its human interpretation, we have no knowledge. Equipped with only our sensory apparatus, we cannot know what lies behind the curtain of interpretation. The world itself will always be unknowable, unfathomable, and mysterious to us. That’s not a problem; it’s the source of the possibility of magical experience for human Being.

If you are interested in reading more on this subject, I encourage you to take a look at my book, Hoodwinked.

What About the “Observer Effect”?

I’ve been speaking and writing for about a decade now about, among other things, the relevance of quantum physics to the inquiry about what a human being really is. With respect to this work, a number of people have asked if I’m talking about the so-called “observer effect.”

In general terms, the observer effect is the established fact that observing a situation or phenomenon necessarily changes it. This idea shows up in a range of contexts, from psychology to computer science and electronics to quantum physics. Let’s take a very brief look at how the effect shows up in these areas.

In psychology, “observer effect” is the name given to the phenomenon that occurs when the subject of a study alters their behavior because they are aware of the observer's presence. This results in incorrect data: the researcher records behavior that is not the way the subject actually behaves when not under observation.

In computer science, the “observer effect” names a situation in which a software bug seems to disappear or alter its behavior when one attempts to study it. Studying the behavior of software usually requires using other software as a probe, and the probe becomes part of the software being studied, thus altering its behavior.

In electronics, by attaching a measuring device of some type to a system being measured, small amounts of capacitance, resistance, or inductance may be introduced. Though good instruments have very slight effects, in sensitive circuitry these can lead to unexpected failures, or conversely, unexpected fixes to failures.

The Double-Slit Experiment in Physics

Actual result of the double-slit experiment (energywavetheory.com)

One very interesting use of the term is in physics, specifically quantum physics. The famous double-slit experiment demonstrates the wave nature of particles. So-called fundamental particles, such as electrons, when made to impinge on a screen with two slits, appear to pass through both slits at once. This is obviously impossible from a classical perspective. However, examining the results of sending thesse particles through the double-slit apparatus shows this behavior as an interference pattern on an optical screen.

Double-slit with water (wiki.anton-paar.com)

This is the same result you get if you allow water waves to impinge on a barrier that contains two slits: at some distance behind that barrier, the waves coming from the slits will interfere with one another, causing them to add to each other at some places and at other places cancel each other out. This phenomenon is called interference, and it’s interpreted as conclusive evidence of wave behavior.

The classically-expected result (commons.wikimedia.org)

The observer effect enters into this experiment in the following manner: the way we look at the world causes us to assume that a physical particle will only pass through one of the slits. After all, every object we’ve ever observed at our human scale follows only one trajectory through space and time. However, it turns out that any attempt to measure which slit the particle “actually” passes through destroys the interference pattern and produces the classically-expected result of all the particles striking the screen. This measurement by an observer and his/her equipment effectively removes the wave aspect from the particle!

A deeper look into the nature of human beingIt turns out that the “observer effect” shows up in an entirely different and much more fundamental way when you take a deeper look into the nature of human perception and its relationship to the world around us.

We most commonly think of “human being” as name given to a particular creature, an animal with certain unique characteristics, one of which is consciousness of self. In terms of this definition, the human animal is the object and the consciousness of self is an attribute of that animal.

It is possible, however to consider human Being in an entirely different way, in which the human animal is the manifestation of a particular degree of consciousness of self. In other words, once a self becomes conscious of itself, it appears in physical manifestation as the human animal.

This amounts to an inversion of the usual conceptual relationship between the world and the conscious observer. Classically, the conscious observer is contained within the world an as object among many other objects. In the inverted view, the world is contained within the consciousness of the observer as an interpretation of sensory data delivered to the brain. The form we call the human animal then is the end result of the interpretive mechanism which takes optical, audible, and other sensory data and produces a multisensory picture in the brain. It is this picture to which we refer when we use the term “human being.”

The observer effect in the context of consciousnessHow, then, does the “observer effect” show up when the world of objects is recognized to be the result of an interpretive process?

The default or classical understanding of the observer effect is the phenomenon of changing the situation from the way it was before being observed to something different. But when the world and all its components are viewed as the result of interpretation by the observer, the observer effect is no longer an agent of change but rather an agent of creation. The observer brings the world he/she is experiencing into being through interpretation. There is no situation prior to its observation, and therefore there can be no effect on the situation in the usual sense.

This inversion of the relationship between the world and the observer has numerous benefits. Psychologically, it puts the observer in a position of personal power with respect to the world of one’s experience which is unavailable in the classical view. Interpretations can be changed or replaced, and thus the world as a product of interpretation can be changed as well.

An Aside for Quantum Physics EnthusiastsIn quantum physics, the difficulty of visualizing how the wavefunction can collapse upon observation largely disappears in the context of that inversion as well.

The phrase “collapse of the wavefunction” refers to the fact that the normal state of an unobserved particle is what’s called a superposition of possible states (possible outcomes of any experiment on or measurement of the particle), and the actual experiment or observation causes this superposition to disappear. We know this because we never observe a physical object, no matter how small, in more than one state at a time. This collapse is very hard to explain when the particle is considered to exist as it is, whether it’s being observed or not.

However, when what we think of as the particle is the result of a process of interpretation of sensory data (augmented of course by detectors or other scientific devices), it’s the interpretation, or the description we so derive, that contains the collapse. In this “interpretive-centered” view, the particle, the wavefunction, and the experimental apparatus are all parts of a description of the world. And this description is not the world itself.

This is the world you and I experience: an interpretation of sensory data. As to the question of what the world might be beyond its human interpretation, we have no knowledge. Equipped with only our sensory apparatus, we cannot know what lies behind the curtain of interpretation. The world itself will always be unknowable, unfathomable, and mysterious to us. That’s not a problem; it’s the source of the possibility of magical experience for human Being.

May 11, 2022

What is Real? Maybe It’s About Time

What is real?

What is real?It’s a question that’s been argued about for a long time, both in popular culture and in scientific circles. Here’s a quote from Psychology Today:

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” — Phillip K. Dick

From dictionary.com:

“Existing or occurring as fact; actual rather than imaginary, ideal, or fictitious: a story taken from real life.

And attributed to Albert Einstein:

“The further quantum physicists peer into the nature of reality, the more evidence they are finding that everything is energy at the most fundamental levels. Reality is merely an illusion, although a very persistent one.”

What do we all believe about what is real?

What do we all believe about what is real?The human mind seems to contain a number of perceptual biases. Perhaps the primary such bias is the one about what is real. Human beings seem to come inevitably to believe that what is real is that which is identified by the senses as being the actual configuration of the physical world. “I believe what I see with my own eyes,” people say.

People can, and do, argue about how the senses actually work. They argue about whether the pictures the brain assembles from sensory information actually correspond to a fixed configuration of all the atoms and molecules we say make up the world.

And then there’s the question of whether quantum theory tells us that there is always uncertainty about that configuration, how the distribution of possible configurations collapses into the one observed, and all that.

Here’s one more way of looking at this question about what is real.Let’s consider the relationship between reality and time. The physicist Carlo Rovelli, in his book “The Order of Time,” points out that “usually, we call ‘real’ the things that exist now, in the present. Not those that existed once, or may do so in the future." We say that things in the past or the future ‘were real’ or ‘will be’ real, but we do not say they ‘are’ real.”

Rovelli then goes on to challenge this view in the light of the special theory of relativity, which shows that time is different for different observers. He concludes from special relativity that the “present” is not defined for distant observers, that is, distant from us.

This understanding of the “present” from physics may, however, be misleading in defining reality for us human beings. That’s because any theory about anything is conceptual. It’s an explanation for what we observe and experience. The special theory of relativity, for example, is a mathematical explanation of why we always measure the speed of light as being the same, no matter how fast we or the light source is moving. It’s a model of the physical world, not the world itself.

For a human being, the present is defined experientially, not in terms of time. For us humans, now is all there is. We can’t experience “then,” any more than we can experience “there.” It’s always “now and here,” for us in our experience, in our reality.

What about those things we say “were real” in the past, or “will be real” in the future? A human being can’t experience past or future. Experientially, there is no past; there are only memories and records. And experientially, there is no future; there are only pictures in the mind of what we think might be.

What about “solid, physical reality”? I contend that “solid” is a concept, created in the mind after we experience certain electrical stimuli in the brain. “Solid” is ultimately a memory. That’s the nature of what we think of as the physical world. It’s a memory.

So again, what is real?To go back to Rovelli’s initial statement about things being real in the present, none of what we remember is real, because it’s not taking place in this moment. And, nothing in the future is real, because it’s only a picture in the mind. So reality isn’t about solidity, or about a particular configuration of atoms and molecules, or even about what everybody knows. Reality is about the present moment, about what you and I are experiencing in this right-now. If you’re in the present, you’re experiencing what’s real. As soon as you think about it, it’s not real anymore, though it can be useful to think about it. It’s about now. It’s about time.

March 21, 2022

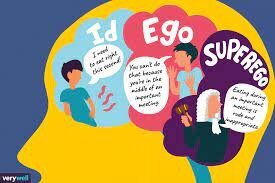

Illustrating the Global Ego

From www.verywellmind.com

In a previous post, I suggested that one of the most fundamental misunderstandings we humans labor under is that an ego is a part of ourselves. In psychoanalysis, the ego is the part of the mind that mediates between the conscious and the unconscious and is responsible for reality testing and a sense of personal identity.

Instead, we can think of the ego as a construct, a conceptual entity each of us created in order to get along in life. It’s essentially a story about ourselves as individuals.Virtually all of us believe that what we see out in the world is seven-plus billion beings interacting with one another. That leads to great complexity in analyzing all apparent interactions if we desire to make sense of what we see out there. However, we could choose to look at the human drama in the following way: for each of us, the so-called human drama is a play starring one’s own ego, with all the rest of the egos we encounter as supporting actors. And none of those egos represent even a part of who we really are.

Immersed in the global Ego

Picture each newborn human being emerging into a global field of Ego, as if we are newborn fish emerging into the ocean. We immediately begin to look at life through the Ego-field into which we have emerged, and we allow it to shape our world view, the one we’ll carry with us and with which we’ll act consistently throughout our lives.

That world view has as its foundation the assumption that we are separate beings, separate from one another and from Being, that which we really are. As we become acculturated into that view, we are taught limitation, scarcity, and inevitability, all of which rely on the foundation of separation. And so we each become a unique component of the global Ego.

That’s a fundamentally different story. Looking at the world from that perspective allows us to lighten the load of the seriousness with which we ordinarily regard our lives. It relieves us of the idea that the ego is a part of us that we need to moderate, change, or rid ourselves of altogether. It also relieves us of blame, regret, shame, and so on. All of those belong to the Ego and not to us as Being.

I recently came upon two editorials in the New York Times in their March 18, 2022 edition. Both of these pieces refer to the behavior of the global Ego.

David Brooks

More and more, powerful people “turn into gangsters. When men rise to power and have that kind of autocratic power, they become autocrats and they become mobsters, and they become even more thuggish than they were when they rose to power because they become more paranoid.” - David Brooks

Bret Stephens

… “democracy tends to hide its strengths until it needs them, and dictatorships tend to advertise their strengths until they’re exposed as actual weaknesses.” - Bret Stephens

Both of those quotes describe the way the Ego controls our behavior and acts to hide that control from us, thus ensuring its continued influence and very survival. Autocrats, who accumulate power in a zero-sum context, must protect it from loss. Dictators, who believe in the reality of the power they wield over others, must resist any challenge to their strength lest their power be revealed to be illusory. These imperatives act to distract us from the real problem: we are acting in the interests of something that’s only concerned with its own survival.

We have been hoodwinked into believing that we are members of a species that makes rational decisions based on self interest, and that self interest, when aggregated, results in the best economic interest for all. That’s the definition of “self-interest” in economics.

It doesn’t look to me as if decisions being made on the world stage these days are actually resulting in the best economic interest for all. For a small handful of people, maybe, but not for all. Why is that? I believe it’s because we humans are NOT actually making rational decisions based on self-interest. We’re actually making them based on the interest of the global Ego, and those two entities couldn’t be further apart.

March 7, 2022

Cleaning Up the Ocean of Ego

The Ocean of Ego

Last time, I made the following argument: It’s helpful to consider that we human beings live in an ocean of Ego. Like the fish, we’re not aware of being immersed in that ocean, because we’ve spent our entire lives in it and so we have nothing to compare it to.

That viewpoint seems to me more workable than thinking that ego is a character defect or liability that each of us carries around and which needs to be punished or minimized or gotten rid of entirely.

The ocean in which each of us is submerged is our individual belief system. And our belief systems, though they differ in some respect from one another, are all based on some common fundamental misunderstandings that we’ve all inherited from the culture into which we were born. That commonality is what forms the ocean of Ego.

Let’s see if we can identify which aspects of our belief systems constitute misunderstandings, because if we can do that, we can allow our beliefs to be more fully consistent with what’s really going on, and that should make us more effective in addressing our problems.

Vladimir Putin (from Financial Times)

In my previous post, What in the World is Going On, I suggested that Mr. Putin is demonstrating for us how the Ego blames, resists, and seeks revenge. It does so when it’s threatened with loss of power, prestige, and influence. It seethes, it plots revenge and restitution, it seeks to dominate others and avoid their domination, and it attempts to even some imagined score.

The question now is, what misunderstandings lie beneath all that?Only something that believes it has power, prestige, and influence would plot revenge and restitution for losing those things. But the Ego, the ocean of belief we swim in, never had any of them to start with. The Ego is a construct, a conceptual entity that behaves as if it is a being. The Ego clearly considers itself to be something whose survival is threatened and that must survive at all costs. And that’s simply not the case.

Who created that construct, that conceptual entity? We did! As we were growing up, we felt the emotional pain of discovering that our lives were not under our control, if only because people bigger than we were making all the decisions. In order to protect ourselves from that pain, we developed strategies for minimizing it and for trying to regain some measure of power that we couldn’t seem to access. And then we relied on those strategies to do what we created them for.

Those strategies coalesced into our individual egos. And because our struggles were nearly universal in our culture, the strategies were common to most of us. That is what gave rise to the ocean of Ego.

So, here’s the first of our fundamental misunderstandings:

“We are our egos!”We believe we are these invented selves, these constructs or conceptual entities, which we created in order to get along in life. And if recognizing that misunderstanding makes us uncomfortable, or if we refuse to recognize it, that’s just the Ego trying to insure its own survival.

We are Being. We don’t need survival mechanisms. For Being, survival is a non-issue. All of the survival-based strategies… and all of the “bad behavior” we see out there is a survival-based strategy… are there to insure the survival of something we created! Clearing up just this one misunderstanding begins the process by which we (Being) will recover our power.

So, thanks are due to all those whom we have considered “bad actors” out in the world. They serve us by illuminating for us particular aspects of the global Ego, so that we can shed layers of misidentification with which we are all burdened. That is the way to true freedom and the recovery of true power, the power to live our lives in harmony with the Being that we are.

Next time: more about fundamental misunderstandingsFebruary 24, 2022

What In the World is Going On?

From the New York Times, February 24, 2022

As I write this, the lead story is that Russia is invading Ukraine. It feels to many people like yet another setback for those of us whose desire for peace and harmony seems to be consistently thwarted. The story this morning is all about bad behavior and punishment, or at least about consequences, for that behavior. When I think about the history of this and the previous century, I find it hard to identify any occasion on which punishment and consequences have actually rid the world of the bad behavior they were designed to counter. Why is that?

Whenever I observe what I judge to be bad behavior, whether in myself, my family, or my community, the first place my mind goes is to: “What’s wrong with him/her/them?” “What character defect is responsible for this conduct?” “How can we fix ourselves and people in general?”

Back in July of last year, I suggested in a post entitled “Ego and the Transformed Relationship,” that there is another way of looking at these situations that might offer more understanding and ultimately more leverage in changing the way things are. We normally consider ego to be that (undesirable) aspect of our being in the world that blames, resists, and seeks revenge. I suggested that it is more effective and empowering to consider Ego as the context or container in which we live our lives.

The Ocean of Ego

I find it useful to liken the Ego to a global ocean, or field, in which we are immersed. And like the fish in the ocean, we’re not aware that the ocean of Ego colors or distorts everything we look at. Because we’re not aware of this fact, we think we’re seeing things clearly, the way they are. When we’re not aware of the ocean we are immersed in, we tend to regard others, and ourselves, as acting rationally from that person’s particular perspective, which might be selfish, altruistic, or somewhere in between.

However, what we’re really doing is acting in accordance with our view of the world from within the Ego. So, while we are sorely tempted to blame those who act in ways that are odious, distasteful, or simply incomprehensible from our perspective, we could instead thank them for illuminating the Ego itself.

So, what of the drama that’s playing out this morning in Ukraine? We can indulge in blaming Mr. Putin, or Mr. Biden, or whomever we choose to identify as the culprit in what’s going on. Or, we can allow those prominent characters in the drama of the day to illuminate for us a particular aspect of the global Ego, the dominant cultural understanding of our world, the ocean in which we’re immersed.

From that perspective, what does Mr. Putin have to teach us this morning? We can choose to see him as showing us the behavior of the Ego when it’s threatened with loss of power, prestige, and influence. It seethes, it plots revenge and restitution, it seeks to dominate others and avoid their domination, and it attempts to even the score of some un- or misidentified contest of will.

Where else have we seen that behavior? Where else have those proclivities of the Ego been acted out?

Who among us has not indulged in seething, plotting revenge and restitution, trying to avoid the domination of others, and perhaps in trying to even some score? If we’re all immersed in the same ocean, and I think it’s demonstrable that we are, we have all had those thoughts, and many of us have acted on them in some way. And it’s no wonder… all of us are thinking within and acting from a viewpoint that is distorted by the Ego. That’s inevitable for a human being, acculturated as we are to gain membership in the dominant worldview into which we were born.

What is the way out? Is that even the right question to ask, assuming we do want out of this mess?

A “Way Out”

Suppose I decide to clean house when the sunlight is coming in through all the windows. My first reaction upon seeing the dirt that previously had gone unnoticed might be some form of upset. If I don’t want to take the time and effort to clean it up, I might sweep it under the rug. Or I might wait for clouds or darkness to hide the dirt, so that my ordinary efforts at housecleaning might be considered “good enough.”

It has become apparent to me that if I really want my house to be clean, I can take advantage of the sunlight that pours in through the windows to illuminate what’s not clean. Mr. Trump illuminated some aspects of the global Ego, and Mr. Putin seems to be taking those aspects “on the road,” so to speak. At some point, human beings will have had enough of providing the energy with which the Ego sustains itself. They (we) will recognize that we must get “underneath” our identification with the Ego and find the truth of our Being, the fish that is immersed in the ocean. And then, because the ocean of Ego is made of a few fundamental assumptions, we can clean up the ocean so that we can see clearly.

It’s worth a try. Next time: cleaning up the ocean of Ego…

February 17, 2022

The Case for Not-Knowing

Our minds record multi-sensory records of the past, and we call these records ‘memory.’

[image error]Our memories

Those memories also contain the meaning we placed on each of those recorded scenes, as well as a record of the emotions we experienced in those moments of now. And our minds are equipped with a sorting mechanism that allows us to compare the present situation to all those in memory. We then consult our mental library to figure out the action we should take next.

This process, called rational analysis, is very powerful when used according to its design. The knowledge we accumulate as we face challenges and learn from our successes and our mistakes enables us to become increasingly effective and efficient in solving our problems.

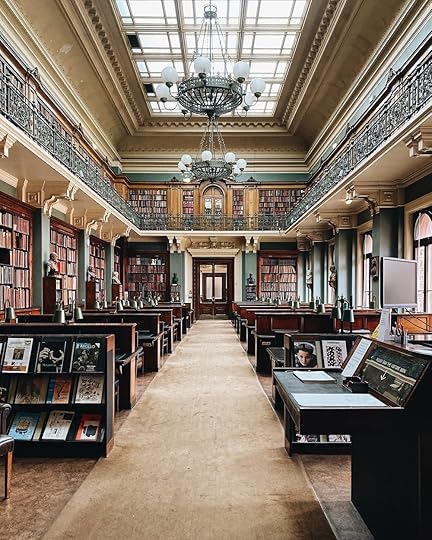

The Library

This storehouse of records of the past is like a library. Libraries contain records of the past… past writings, sayings, quotes, recordings, and so on. And now that most libraries have their card catalogs online, cross-referencing and comparisons are easier than ever before.

However…Poring over records of the past won’t provide solutions to the problems our rational approach to life creates. That requires “thinking outside the library.

Albert Einstein is quoted as saying that “You can’t solve problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” It seems that we are able to solve certain kinds of problems, but very often we create new and different problems in the process. Why is that?

Looking for solutions to our problems in our records of past experiences (our memories) is called thinking inside the box. We are constantly exhorted to “think outside the box.” But nobody ever tells us what the box is made of, where the walls are, and how to get out of the box. So, we’re typically left feeling powerless when we hear that advice.

I’m suggesting that the box is made of our beliefs and opinions. Beliefs and opinions give us a place to stand in our social environment. They allow us to stake out conceptual territory and defend it from others. But they also tend to filter out anything that doesn’t conform to them. In that way, they keep us within their boundaries, inside the box.

So, how do we get outside the boundaries of our beliefs and opinions? The answer seems to be to acknowledge that while they do allow us to win arguments and feel “right,” they don’t actually empower us to discover new conceptual ground.

There is a place to stand that doesn’t constrain us, that doesn’t force us to defend our positions. It’s called “not-knowing.” The problem is, it’s a scary place! It doesn’t allow us to win arguments. It can’t be defended. It doesn’t even feel like a place to stand. But unless you can stand in “not-knowing,” you can’t ever discover anything new. Not-knowing is outside the box. It’s not a place outside the box… it’s the space in which the box exists. It is the outside of the box!

February 14, 2022

The Purpose of Metaphor

As a dear friend of mine said the other day, “ALL good writing contains metaphors. Otherwise it reads like a stock report or a grocery list.” I think that’s so true. One primary purpose of metaphor is to arouse interest in our readers, and to add color and feeling to our efforts to articulate whatever we’re writing about. That’s the province of poets and songwriters.

There is a subtler purpose for metaphor, however, and that is to point the way to things that are difficult to describe directly.

The word “ineffable” means “that which is incapable of being expressed in words.” In Hoodwinked, I argue that there are aspects to our being human that are ineffable. When someone asks us who we are, we usually start with our name, what we do, and perhaps other personal characteristics. We almost never get to the ineffable aspects of who we are.

That’s where metaphor comes in. Metaphors can point the way to those aspects by helping us visualize hopelessly inadequate (not to mention dry and boring) descriptions of the ineffable.

Here’s an example of such a metaphor from Hoodwinked. It’s called the planetarium. The planetarium is a mechanism that allows us to project ideas into visual representation. While we have the language to accurately describe how planets and moons orbit their host stars and planets, projecting those movements onto the inside surface of a dome helps us visualize what orbits look like, and can even evoke emotion because of the sheer beauty of the night sky.

It’s probably fairly obvious that the laws by which celestial bodies appear to move about were figured out by people who observed those motions. That’s our common assumption about how abstract ideas, such as the laws of celestial mechanics, relate to our observation of the world. First comes the observation, and then we come upon the law which describes what we’re observing.

However, there exists another way of seeing this relationship between our ideas and what we observe. Without claiming this is a better way, or the “right” way, we can choose to see the physical world as a projection of our ideas about it.

The ordinary, or default way of seeing this relationship places us humans as passive observers of a world that doesn’t care what our ideas about it are. That relationship can be seen to be profoundly disempowering. But seeing the world as a projection of our ideas puts us in the driver’s seat.

But is that explanation true? How would you test that theory? I guess you’d have to assume it as a premise, change your idea about the world, and see if the world shifts accordingly, over time of course. Try assuming that the physical world to which you awaken in the morning is a projection of your inner understanding of who you are and of your relationship to the world around you. That view gets rid of blame and irrational fear by placing you at cause: the creator of your own experience. See if it works for you!

February 6, 2022

A Brief Conversation about Reality

Back in September, 2021, I posted a meme I created about quantum physics as a story. That post has generated a huge number of comments, some acknowledgement, and much criticism. Here’s a brief, illustrative conversation.

Michael: It goes to the theory that nothing happens until it is observed.

John: So, if you close your eyes, it doesn’t exist right?

Larry: Hey John, thanks for the question, though it sounds more like a comment. This business of whether the world exists independent of its observation is not idle speculation. It has been argued about since the advent of quantum physics.

My premise is that equipped only with five senses and a brain, all we have as humans is the picture our brains create, essentially an interpretation of electrical impulses. I can think of no way one could prove that the world actually exists as our pictures seem to suggest.

So, our interpretation of what the world seems to be constitutes a story about the world. But quantum physics is also a story, and while it is the most powerful description we have (in terms of predictive power) of the world, it doesn't speak directly about how or what the world is. Instead, it speaks about what we're likely to see when we observe the world. And those two things are different.

So, it's not that the world doesn't exist when you're not looking at it (i.e. when you close your eyes). It's that when you're not observing it you can't know what it will be like when you do open your eyes. You can predict what it will look like, and most of the time you'll be right, but not always. If you seek real knowledge about the world (and your self), you are better off to release what you already know and find a place of not-knowing instead. That will, so to speak, get rid of the box you think in, and it will allow you access to what's really there. That's my premise... I just wanted you to know what I was trying to get at when I did my original post.

I appreciate your comments and questions!

The Insights Blog

Those superstitions are responsible for Albert Einstein’s declaration that “you can’t solve problems with the same thinking that created them in the first place.” Our superstitions have us hoodwinked!

Those superstitions are responsible for Albert Einstein’s declaration that “you can’t solve problems with the same thinking that created them in the first place.” Constructing belief systems on top of superstitions is like building on top of an unstable foundation.

When we were taught language, it was inevitable that we also acquired the world view of those from whom we learned that language. We now live inside that description of the world, and it shapes and colors everything we look at. Because we depend on that understanding for our well-being and for the success of all our endeavors, it has become a jealous master.

I call our understanding of the world "the water we swim in." Like the proverbial water to the fish, we are essentially unaware that we are immersed in that understanding. My work helps readers unlock their natural power to determine the quality of their own lives. ...more

- Larry Gottlieb's profile

- 122 followers