Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 55

October 1, 2014

Course Correction

So I posted last week about the joys of family vacations. Anyone who knows me can tell you that I love planning trips. When it comes to travelling as a family, I don’t believe in too much spontaneity; I think you need an agenda and that when you tumble off the train in a strange city, there should be a hotel reserved in your name so you know where to go. As a result, I plan our trips pretty thoroughly and well in advance. What happens each day may be a lovely surprise but I always know where we’re going to sleep at night.

However, there are drawbacks to too much careful planning.

Five years ago, after the 2009 Pathfinder Camporee in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, our family rented an RV and drove west, exploring some of the US. Our plan was to drive all the way to Yellowstone National Park, where we would see Old Faithful and go white-water rafting. I had booked ahead campsites in most of the places we planned to stay, up to and including a short stop near Mount Rushmore and then onward to Yellowstone, where we would stay for a couple of nights.

Driving an RV was much less fun than we had imagined. I know a lot of people love their RVs and have made great vacation memories in them, but my main impression was that just to keep on target with our travel schedule we were spending seven or eight hours a day pushing this giant box along the highway, not spending much time stopping to see interesting things. It drove more slowly and guzzled more gas than we had imagined, and I didn’t dare attempt to drive the thing so Jason was behind the wheel hour after hour. As we approached Mount Rushmore I dared to say to Jason, “What if we didn’t go on to Yellowstone for the weekend? We’d miss out on Yellowstone, sure, but we’d spend a lot less time driving and a lot more time relaxing and doing fun things.”

I’m such a hardcore trip planner that it actually took me a couple of days on the road, in the RV, to think that one through and realize that I could change our plans. And yes, I’m sad we never saw Old Faithful, and didn’t go whitewater rafting (although this past summer we did it right back home in Newfoundland and it was awesome). But some of our kids’ best travel memories are from that KOA Kampground in South Dakota where we spent four lovely, fun, relaxing days. As soon as I called ahead to the campground in Yellowstone to cancel our reservation, I knew it was the right decision. I felt lighter, safer and more relaxed when we made a course correction and scaled back our plans.

The same thing happened twice on our recent trip to Europe — once in the Netherlands, when we had planned to take our rented canal boat to Amsterdam, and once in England when we had planned a day trip from London to Liverpool. In both cases Jason and I talked it over and realized the added time we’d spend and the stress of getting there (and in the case of Liverpool, the cost) would be more of a burden than it was worth. On the canal boat, we spent the day sailing to a much nearer town, mooring there and sightseeing (we still went to Amsterdam by train later, after we’d returned the canal boat as planned). In England we never did get to see Liverpool (which I wanted to see mainly because of my obsession with visiting all the Peter Pan statues in the world — there’s one in Liverpool I haven’t seen yet) but had an extra day in London, a quiet relaxing day which we really needed.

In every one of these cases, the decision to make a course correction has meant missing out on something, but it has also led to immediate feeling of rightness, a sense that pressure has been relieved. And because I’m a big believer in listening to your intuition and your gut feelings when you make decisions, I’m trying to figure out how to apply what I’ve learned on vacation to my everyday life.

I know all of us who have goals, dreams and aspirations (and who doesn’t?) are laden down with advice to “Never give up on your dreams! Keep at it!! Don’t get discouraged!!! Keep trying and you WILL get there!!!!” The thing is, depending on your definition of “get there,” this can get to be very frustrating advice by the time you’ve reached midlife. Maybe “getting there” looks like RV’ing to Yellowstone or canal-boating to Amsterdam — something that would be really cool to accomplish, but might be so time-consuming and costly that the destination isn’t, in the end, worth the journey. How does one know?

I sat at coffee with one of my best writer-friends awhile back and we talked, as we so often do, about where our writing careers are going. I said that with the big 5-0 birthday approaching for me next year, I had started to feel that it was time to focus on what I can do, what I am successful at — which, at the moment, is writing historical novels set here in Newfoundland, which will probably never be widely read outside Newfoundland but which have many kind and dedicated local readers. Maybe, I said, that’s my niche, and I should be happy with that niche and not strive for more — a bigger publisher, wider sales, literary prizes, publication for books I’ve written that don’t fit into that niche. I said I’d been thinking that I might self-publish a couple of my unpublished books at some point — not with the hopes of reaching a huge audience, but just to make them available to people who already know and like my work. Perhaps this is enough, I said. I’ve been through that whole round of querying agents over and over, getting rejected, re-working my query or my manuscript — Never give up! Never surrender!! — and I’m no longer sure that’s where I want to put my energies.

My friend wasn’t convinced. She wanted to see me keep striving to reach those far-off goals. And, comparing my career aspirations to family road trips and boat trips, I’m not sure what the take-away lesson here is. Taking the path of least resistance certainly isn’t the answer — if it were, I’d never plan a family vacation at all, and I’d never seek to get my work published, either. But endless striving to go further and do more is not necessarily the answer either — not if it leads to stress and frustration all the time.

I have no easy answers. I just know that I’m trying to learn to listen to my intuition, to wait for that feeling I got when I said, “Hey, let’s stay here at Mount Rushmore instead of driving to Yellowstone,” or “Let’s just take the boat up the river to Muiden instead of trying to get all the way to Amsterdam.” That good feeling of relief, of knowing that the pressure is off and that while I may miss out on something, I’ll be happy with what I have instead. If I can do it on a road trip with my family, I hope I can learn to do it in my writing career too.

I’m just not sure what that will look like yet.

September 24, 2014

Writing Wednesday 85: Word on the Street

September 22, 2014

In Praise of the Family Vacation

Just a couple of weeks ago, my family was in Europe, hopping on and off trains and travelling from Paris to Copenhagen to London in a journey that, despite the decidedly modest nature of our accommodations (the first thing the kids now ask before we go to a new hotel is “Does this one have its own bathroom?”), still cost a lot more than we probably should have spent.

(sadly, the only pic from this year’s trip that includes all four of this is this not-very-good selfie in front of Lego Mount Rushmore, but what can you do? One of us is always holding the camera)

I am a big believer in family vacations. And I recognize that not everyone has the ability to take their kids to Europe. But to my mind the benefits of family vacations are the same whether you’re skiing in the Alps or setting up the pop-up trailer at Butterpot Park. And it can sometimes be much easier not to take a family vacation — travelling with kids poses its challenges, not just from an economic point of view but from sanity and time-management and energy points of view too. I believe there are two unique benefits to family trips that you can achieve no matter how far you go or how much (or little) you spend — two things you can’t achieve by staying home.

1. You experience something new. The opportunity to try, taste, do or see something completely outside the range of their everyday experience is a precious gift to give your kids. Yes, you do valuable and fun and useful things with them all the time at home, and so do their teachers at school, but both home and school fall into routines and there are certain things we and our children will never get to experience if we don’t get outside our comfort zones. And again, this is not dependent on budget or on your ability to travel someplace exotic. Whether it’s a Canadian kid who gets to go to the top of the Eiffel Tower, or a city kid who gets to bait a fishing hook with a real live worm for the first time, the important thing is that your family is doing, seeing or trying something they wouldn’t normally do as part of their everyday lives. That’s how we learn. That’s how we grow. And unlike experiences they might have on a school field trip (which are also great, of course), on a family vacation kids get to do these new things with their parents and siblings. Which brings me to my second point …

2. You only have each other. Once again, this benefit applies regardless of how far you go or how much it costs. The only type of vacation it doesn’t apply to is the kind where you go to visit friends or relatives who live far away and stay at or near their house (or meet up with them somewhere). That kind of trip has benefits of its own — like your kids getting to meet and play with cousins they wouldn’t otherwise know. But I’m thinking here of the type of trip where it’s just your nuclear family, the two or three or four or six or however many of you, in a confined space like a minivan or a camper or a hotel room (or a series of hotel rooms) for day after day after day. On this kind of trip, you make memories whether you want to or not. And many of them are great memories (see point 1) of new things you saw and did and new challenges you faced together.

You will also make memories of how you handled the unexpected disappointments and letdowns of the trip, so that in future years your kids may not remember that you drove them all the way to a National Park to see amazing scenery but may instead remember the 355 games of Uno you played in the tent that weekend it refused to stop raining. I know in the case of our family, any conversation in which someone mentions bad customer service will result in any one of the four of us turning to the others and saying, “No. There is nothing. Nothing,” in an accent that recalls the hotel desk employee in Rome who so memorably (and, it turned out, inaccurately) answered our question about whether there was a place nearby to get supper.

On family vacations, things go wrong. On ours they do, anyway. And our kids argue, and we the parents sometimes lose patience and snap at the kids, and teenagers get bored and complain. And we all have to practice a lot of patience and forgiveness, because we’re not used to such intense, concentrated togetherness for so long, without familiar surroundings or other people or our own rooms to dilute all this togetherness. And these things don’t ruin the family vacation, they are the family vacation. Since the very first time we put six-month-old Chris on a foam mattress in a tent in Terra Nova National Park and fed him baby cereal at a nearby picnic table, travelling together has been a big part of how we become us. I highly recommend it.

September 17, 2014

Apolog-ish

So, I kind of fell down on posting the Women’s Suffrage Trivia Questions here on the blog. I ended up posting five photos with trivia questions on Facebook, and had many readers playing along there, but I fell behind here on the blog. It turned out that having your new book come out the same week that you start teaching classes at school is … kind of a lot to have happening. And now that we’re into the third week of school, and the book is more-or-less out there (still on its way to some bookstore shelves), things are still, well, kind of hectic. But the main thing is, the book is out there. Ish. And I apolog-ish for letting the blog fall a few days behind, but I did have a contest winner, and Edwina now has her free copy of the book, and I’m hoping a lot more people will be reading and enjoying copies of it very soon.

I’ll post book-related updates here as I’m able, but an even better place to look is on my official website, www.trudymorgancole.com . If you click on “Events” you’ll find out when and where I’m reading from and signing the novel, and I’ll post links to reviews and interviews under the “Press” tab. I’ve also created this page which has links to a lot of information about the historical background of A Sudden Sun, so you can check that out too!

September 3, 2014

Women’s Suffrage Trivia, Day Two

Here’s today’s WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE TRIVIA QUESTION (I can’t really call this a Fun Fact):

NAME THIS FAMOUS SUFFRAGIST! She is probably best known for the circumstances of her death in 1913, when she stepped in front of the King’s horse at Epson Derby, sustaining injuries that led to her death four days later. The reasons why she did this have been debated for, well, a century now, but the consensus seems to be that she was attempting to disrupt the event and draw attention to her cause — possibly by throwing a “Votes for Women” sash around the horse’s neck, though this theory, like everything else about the incident, is controversial.

Writing Wednesday 84 Book Talk: The Fault in Our Stars

It’s the last of my summer series about books I love and what I’ve learned from them, and I filmed this one in Amsterdam (where the book is partially set).

September 2, 2014

Women’s Suffrage Trivia — Day One

All this week I’ll be posting trivia facts and questions about how women won the right to vote, in honour of my novel A Sudden Sun coming out later this week. I’m not sure how exactly I’m going to work it out but there will be some free books involved for at least some of those who participate, so check either here on the blog or on Facebook if you have me on Facebook for a daily trivia post/question about women’s suffrage. Here’s today’s trivia question:

This woman, Kate Sheppard, fought for women’s right to vote in the country which in 1893 became the first self-governing country in the world to give ALL women the right to vote in parliamentary elections. NAME THE COUNTRY!!

August 29, 2014

A Season of Shameless Self-Promotion (with, yes, a book giveaway)

Yes, it’s that time again. I have a book coming out. Books, in fact. Which is great. But also awkward, from a social media point of view, because it’s such a difficult line to walk — how, and how much, to promote your own work.

Yes, it’s that time again. I have a book coming out. Books, in fact. Which is great. But also awkward, from a social media point of view, because it’s such a difficult line to walk — how, and how much, to promote your own work.

On the one hand, you have to do it. No writer can exist in the social media world today without talking about his or her own work: helping to promote it to readers is part of your job.

On the other hand, nobody wants to be Todd Manley-Krauss. And every writer is secretly afraid that they are — afraid of being the one whose self-promotion is so shameless that people start unfriending you. If you don’t think it’s a difficult balance to strike, then you’ve probably never tried to promote your own work, in any field (or else you actually are Todd Manley-Krauss).

So here’s the deal: I’ll be talking about this stuff here on the blog a little bit over the next few weeks — here on the blog, and on Facebook (amidst my vacation photos), and on Twitter. I have a new book coming out next week. And an old book of mine has just been re-released in a new format. And as a writer, it’s my job to make sure that if you are interested in either of those, you know that they’re out there and where to get them. And if you’re not, to avoid boring you so much that you stop hanging out with me in cyberspace.

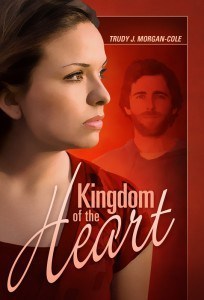

Today I want to talk to you about Kingdom of the Heart, because with all the promotion I’m going to be doing for A Sudden Sun over the next few weeks, Kingdom might get a little lost in the shuffle. So here’s the story:

Back about 1989 or 1990, I wrote what was, for many years, my favourite thing I’d ever written. This was before I started writing historical fiction about Bible characters; this was almost the opposite. I tried (not the only writer to do so by a long shot) to imagine Jesus coming as an everyday person in today’s world, doing and saying the things he said and did the first time, but in a modern North American context. I loved that book, and it was published in 1991 under the title The Man from Lancer Avenue. Some people read it and also loved it (presumably others read it and didn’t like it, but I didn’t hear from them) and in due course, a few years later, it went out of print. End of story.

Awhile back I was contacted by Pacific Press Publishing Association about re-issuing The Man from Lancer Avenue as an e-book. I thought that this would be a great way to make an out-of-print novel available to new readers in the digital age — in fact, I did it myself by self-publishing The Violent Friendship of Esther Johnson as an e-book re-release — so I was eager to do the same for Lancer Avenue. The idea grew with time, and it ended up involving somewhat of a rewrite — I wanted to bring the story and characters into the twenty-first century. Also, Pacific Press asked me to create a condensed version of the book for a print release. This is the book that’s currently available under the new title Kingdom of the Heart — the e-book of the whole story will be out in a few months.

The complete book tells the story from the point of several characters who more-or-less correspond to modern-day versions of Jesus’ disciples. The condensed print version focuses on just two of those characters — Marie Castillo, a contemporary Mary Magdalene, and Pete Johnson, my updated apostle Peter. Marie and Pete, along with their families and friends, both meet up with an unconventional street preacher named Chris Davidson who allegedly has the power to heal the sick, and who invites ordinary people to leave their jobs, homes and families behind to follow him.

Kingdom of the Heart is a short book, novella-length, and it’s available for only $2.99 (US) at this link. I also have some copies to give away, and I’ll gladly send them to the first five people who post here or email me at trudyj65@hotmail.com and tell me why you’d like to have this book.

If you’d like to read the whole story, look for the e-book, which will be out later this year. I’ll let you know … and I’ll try not to be too annoying in the process!

August 27, 2014

Writing Wednesday 83 Book Talk: The Liveship Traders

In fantasy, as in many other genres, there are a lot more people who think they can write a novel than people who actually can. I love reading fantasy but I don’t think I’m one of those who can write it — at least, not at this stage in my career. Maybe someday. In this video I talk about the work of Robin Hobb, one of my two favourite fantasy authors, and I tell you the one thing that I believe you need in order to write a great fantasy novel.

August 21, 2014

Writing Wednesday 82 Book Talk: Gaudy Night

Want a classic mystery that’s really a great love story? Read Dorothy Sayers’s four novels about Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane: Strong Poison, Have His Carcass, Gaudy Night and Busman’s Honeymoon. Watch the video to find out why I think they’re so great.