Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 52

July 13, 2015

Sunset Over the Ocean (a GCSA15 and ECT mashup)

You’d think I’d have a lovely picture of sunset over the ocean to illustrate this post instead of a Springsteen concert video (although, when is a Springsteen video ever a bad thing?), but the whole point of the story is about a hike where I didn’t have my phone with me. I couldn’t take a picture, but — and this is important — I also couldn’t check Twitter, and while I usually think it’s a bad idea to go hiking without a phone, in this case, it was the right decision.

I took the hike in question — the Silver Mine Head path from Middle Cove to Torbay, for those keeping score at home — last Wednesday evening, July 8, at the end of a day when I’d outwardly done little except stare at my computer, but inwardly it had been a tough, emotional day.

To those of you who either don’t go to church, or go to churches where they’ve very sensibly given women equal status with men years ago, this may seem unnecessarily obscure, but I spent most of this Wednesday completely absorbed (via Twitter, Facebook, and live-streaming) in my church’s General Conference session, a world-wide meeting held once every five years, at which delegates were voting on whether to allow the different divisions of the world church to proceed with ordaining women to ministry as they saw fit. After a long day of speeches on both sides, the vote was taken.

Most supporters of women’s ordination, like me, already felt that the “Yes, allow women to be ordained” side would probably lose this vote, for a lot of complex behind-the-scenes reasons having to do with both politics and politicking within the church, and with deep cultural differences between the different areas of the world church.

As I watched the livestream and commented on the presentations via Twitter and Facebook, I felt hopeful and encouraged at some of the powerful, visionary speeches that were made in favour of the motion, but also deeply discouraged by some of those against. Not so much discouraged by delegates from Africa and South America speaking against women’s ordination because I know that people are deeply influenced by their culture and I know that cultural norms in many of those countries don’t grant women equal status with men. But discouraged by people from North America — especially one young woman, who spoke with the kind of confidence and authority that could only be assumed by a woman benefitting from 50+ years of hard-won feminism in her culture — speaking against it, arguing to hold women back from full equality. It was hard to listen to, and discouraging. Then people began voting, and, knowing that it would take hours for the votes to be cast and counted, I went for a hike by the ocean.

To be honest, I expected to feel sadder and more upset than I did at that point. Knowing that the vote was probably going to go against women’s ordination, I had been thinking about it for days beforehand. A few days earlier, I’d been listening to my iPod when the Springsteen cover of “This Little Light of Mine” (video above) came on, and I burst into tears. That song usually makes me want to get up and dance and raise my hands in the air. Why did the idea that Jesus gave me light, and I’m gonna let it shine, suddenly make me cry?

I think it made me cry because I was already pre-mourning that vote against women’s ordination. I have never, not for one minute, in my long life of churchgoing and following Jesus, wanted to be any kind of a minister. The pastoral ministry is incredibly not for me. Yet I have spent all these years in church supporting the idea of women in ministry, hoping to be part of a church that embodies the simple ideal of Galatians 3:28, “In Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for all are one in Christ Jesus.”

It’s always seemed so simple and clear to me, although I’ve done a lot more Bible study to make sure that the truth that seems so obvious in that one verse really is borne out throughout the whole Bible (spoiler: it is). But I’ve always known that it’s not simple and clear to all Christians. It’s a divisive, debatable issue. When I was a student at an Adventist university in the early 1980s, I had female friends who were studying theology or completing M. Div. degrees at the seminary, and they were being told, “Be patient. The church is changing. By the time you’re ready to go out in the field, the church will be ready to ordain you.”

And now we are all middle-aged and some of us are old, and the church is changing, but not always in the ways we’d expected. Yes, there was more support for the idea of ordaining women than there was at any previous GC, but there is also a strong conservative movement that is pulling in the opposite direction (on this and other issues) and those voices are very prominent in leadership right now.

Anyone who knows me either in real life or online knows that I wrestle a lot with my relationship to my church. That I love it a lot, and am very actively involved in it, but also that I disagree with its teachings on a few controversial points, and don’t mind saying so. I struggle with this, and over the years, as I’ve watched more and more dear friends give up on their struggle with the church and just step away, I’ve wondered whether I would ever be one of them.

I was crying several days ago as I listened to “This Little Light of Mine” because I know that Jesus has given us all light, but we don’t always let each other shine. And on Wednesday night, as I hiked the beautiful trail on the rocks above the ocean, I sang that song over and over — sometimes out loud, sometimes in my head — because no matter what happens, no matter what a bunch of dudes in suits at a meeting in a stuffy auditorium say, I still believe it. I believe Jesus gives me light — gives all of us light — and we can choose to share it with the world. We can do that inside an institutionalized religious body — though they may make it more difficult with their rules and regulations about how much light and when and where. Or we can do it outside any organized group, though that may feel isolated and lonely sometimes. The important thing is: WE SHINE.

When I reached the river that crosses the Silver Mine Head trail last Wednesday night, where I planned to turn back to Middle Cove and my parked car, I sat on a rock for awhile and looked out at the ocean. It was getting close to sunset then, and I knew the vote was probably in at the GC, and I knew that my beloved church had most likely voted, once again, to deny the gifts and calling of women in ministry. I was glad I had misplaced my phone before leaving the house that evening, because if I’d had it, I would have been checking Twitter to see the results. And I didn’t want the outside world, or the outside church, intruding on that sunset moment between me and God.

Then someone did intrude — a group of about fifteen teenagers of various ages and sizes, picking their way across the rocks on the river, coming from the Torbay side and heading to the Middle Cove side. I told a few of the girls in front, as they walked past, to watch out for the muddy part of the trail they’d just come through. The diversity of age in the group, and the presence of one bearded thirty-something guy as the token adult bringing up the rear and making sure everyone got across, screamed, “CHURCH YOUTH GROUP!!” to anyone with eyes to see. So I chose to believe that was what they were, and that right here along my path a young adult was shepherding a bunch of teenagers on a hike and to a bonfire on the beach because of a love for Jesus that he wanted to share with them. Because Jesus gives us light, and we’re gonna let it shine.

As the probably-a-youth-leader guy passed me there on my rock, he said, “Sorry for disturbing your peace!” so I must have looked like I was meditating or something, and I laughed and said, “No, that’s just fine!” And it was. My peace was just fine, and for that moment, regardless of the perfectly legitmate sadness and anger I’d felt before and would feel again, it was true. There on the rocks with the natural beauty of the sea and shore, and the human beauty of a bunch of kids on a hike, God seemed much bigger than any church meeting. The phrases: “There is so much good in the world; there is so much God in the world” repeated over and over like a mantra in my head, along with “Jesus gave me light; I’m gonna let it shine.”

Am I angry, hurt, disappointed by the church’s decision, once again, not to give women an equal footing with men? Oh yes. Am I worried about the direction in which certain conservative elements are pulling the church, not just on this issue but others? Very much so. Am I leaving my church? Not till they kick me out. Will my relationship to the church change? Yes, but then it’s always changing — always has been, ever since I was toted off to church all bundled up to be dedicated as a baby; it will keep changing till they carry me out of there in a box, as they someday will if Jesus doesn’t return before then.

But my relationship with God will always be bigger than my relationship with the church. And I will always try to let it shine.

(ECT stats, for my own keeping-track purposes: between this hike and another one earlier, I completed the tail end of Father Troy’s Trail and all of the Silver Mine Head trail — a total of about 3 km one way, or 6km return, as I did it).

June 30, 2015

7 Reasons Why This Traditionally-Published Author is Releasing a Self-Published Novel. Number Four Will Blow Your Mind!

This summer, I’ll be releasing my novel What You Want, a work of contemporary fiction about three unlikely friends on a road trip, as a self-published e-book. There’ll be a paperback release later, probably sometime in the fall.

What would convince me, as a writer in mid-career who has had 23 books published by traditional publishers, to self-publish a novel? You’ll be amazed by the answers!!

1. I have run out places to spend or store the piles of cash I made from traditional publishing. As we all know, there’s a TON of money in traditional publishing. Authors can make as much as one or even two dollars for every copy of a book sold, and with small publishers like the ones I’ve worked with, that can run into three and even four digits! It’s just not fair for one human to have so much wealth at her fingertips.

As we all know, there’s a TON of money in traditional publishing. Authors can make as much as one or even two dollars for every copy of a book sold, and with small publishers like the ones I’ve worked with, that can run into three and even four digits! It’s just not fair for one human to have so much wealth at her fingertips.

2. I need a break from the paparazzi. The book trade is glamorous but exhausting. I’m sure you’ve all read blog posts and tweets from your favourite authors complaining about how tiring it was when they went on that nine-city book tour and had to be up at five to do morning television and come back to the hotel room and ice their hand after signing 3000 books in two hours. I myself have gone on tour to locations as exotic as Mount Pearl and even Conception Bay South. I have spoken to groups of up to sixteen people and signed as many as five books in an afternoon. A gal needs a break from that kind of adoration.

The book trade is glamorous but exhausting. I’m sure you’ve all read blog posts and tweets from your favourite authors complaining about how tiring it was when they went on that nine-city book tour and had to be up at five to do morning television and come back to the hotel room and ice their hand after signing 3000 books in two hours. I myself have gone on tour to locations as exotic as Mount Pearl and even Conception Bay South. I have spoken to groups of up to sixteen people and signed as many as five books in an afternoon. A gal needs a break from that kind of adoration.

3. Matt Damon is bugging me to know if he can star in the movie adaptation. We all know that some writers have achieved mind-blowing success with books that started out as self-published works. Let’s take E.L. James for example. Wait, no, let’s not. Let’s take Andy Weir, whose book The Martian, originally self-pubbed online, not only became a bestseller when it was picked up by a traditional publisher, but is now being made into a movie starring MATT DAMON. MY MOVIE BOYFRIEND. So apparently, self-publishing a book will lead directly to me meeting Matt Damon. I can’t draw any other conclusion, can you?

We all know that some writers have achieved mind-blowing success with books that started out as self-published works. Let’s take E.L. James for example. Wait, no, let’s not. Let’s take Andy Weir, whose book The Martian, originally self-pubbed online, not only became a bestseller when it was picked up by a traditional publisher, but is now being made into a movie starring MATT DAMON. MY MOVIE BOYFRIEND. So apparently, self-publishing a book will lead directly to me meeting Matt Damon. I can’t draw any other conclusion, can you?

4. Did you really think #4 would blow your mind?? Seriously?!?! Honestly, if it’s not clear by now that this is a parody of one of those Buzzfeed listicles in which #4 NEVER ACTUALLY BLOWS YOUR MIND, well, I don’t know what to say. But I will say: everything above #4 has, of course, been for laughs. All the points below #4 are the REAL reasons I’m self-publishing.

5. I have a story I want to share with readers. This is a book about three characters who have been living in my head for a long time. I wrote the first draft of this story several years ago, and have been fiddling with it off and on ever since. This year, I just had the strong feeling that I really wanted readers to be able to meet Megan, Jonathan and Andrew and share their adventures, and self-publishing the story as an e-book is the most direct way to do that. Click here if you want to learn more about this story, which you will be able to read later this summer.

6. This book is different from my other books.

Let me be perfectly clear: I am not one of those writers who’s self-publishing because I’m unhappy with traditional publishing. I have had GREAT experiences with traditional publishers. Breakwater Books, which released my three Newfoundland historical novels, is simply the finest regional publisher in Atlantic Canada. I hope they will continue publishing my historical fiction for as long as I can keep writing it. As for my earlier books — the Biblical fiction and other inspirational books I published with Pacific Press and the sadly-now-defunct Review and Herald — right now, I don’t have any new ideas for books in that line, but if I do, I would love to work with the team at Pacific Press again.

Despite my jokes above about wealth and fame, the truth is that except for a very tiny handful of bestselling writers, nobody gets rich and famous writing novels — whether traditionally published or self-published. Traditional publishing and self-publishing both have their strengths, something I discussed awhile back in this video about the subject.

What You Want is something I haven’t done before — contemporary fiction for a mainstream audience — and I want a new way to get it to readers. Some authors use pen names when they jump into a different genre. I’m not going that route — I’ll always be Trudy Morgan-Cole — but I am going to make use of whatever publishing avenue seems to fit best for a particular work.

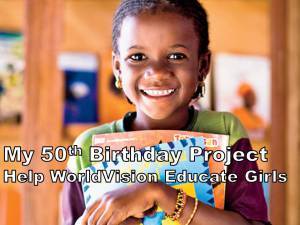

7. I’m raising some money for a good cause. Some of you may have noticed this pic on the sidebar of my blog here announcing a fundraising project. I have a big milestone birthday coming up this year, and I’ve decided that between the time I release What You Want in mid-July, to my birthday on Sept. 11, every cent I make from selling copies of the book will go directly to WorldVision programs to help girls in developing countries access education. So if you want to help out with this project, jump on the bandwagon and grab the book as soon as it comes out!

Some of you may have noticed this pic on the sidebar of my blog here announcing a fundraising project. I have a big milestone birthday coming up this year, and I’ve decided that between the time I release What You Want in mid-July, to my birthday on Sept. 11, every cent I make from selling copies of the book will go directly to WorldVision programs to help girls in developing countries access education. So if you want to help out with this project, jump on the bandwagon and grab the book as soon as it comes out!

Watch this space for further developments, and be sure to check out my What You Want page for more information.

June 26, 2015

Shelf Esteem: Book Questions Answered

In this video I talk about books people spotted in my last video, the Messy Bookshelf tour. In less than 5 minutes total I discuss Margaret George’s The Autobiography of Henry VIII, Douglas Adams’ Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, Caryl Rivers’ Virgins and Girls Forever Brave and True, and, last but not least, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, which I explain (as I did in my review after reading it) is, in a few ways, quite a lot like the Bible.

June 24, 2015

ECT #3: Flatrock to Gallows Cove

I had company this time — my cousin Jennifer joined me for the 5.7 km hike from Flatrock to Gallows Cove on Father Troy’s Trail. Having another hiker is not only good company but offers the possibility of a car parked at both ends so we could do a longer one-way hike. It was a chilly but clear evening and the views were tremendous! Also, I found a cache.

This means I’ve now done almost all of Father Troy’s Trail, except for the little piece from Torbay Beach to the Spray Lane end of the trail, and I’ll soon have to start branching out to other parts of the East Coast trail.

Distance: 5.7 km. Probably would have been an even 6 if we’d walked all the way out to the Beamer at Flatrock, but I was in a bit of a hurry to pick up Emma from work so we took a shortened version and did not go right out to the end of the point (if we had, I’d probably have found another cache, because there is one out there).

June 13, 2015

ECT #2, Gallows Cove to (almost) Torbay Beach

Continuing from my last blog post, I did another mini-section of Father Troy’s Trail on the ECT this past week. I started at th same spot I started before — Gallows Cove — but headed south instead of north, making it almost all the way to Torbay Beach and back in about an hour. I could have gone farther if someone had been picking me up at the other end, but knowing that if I went all the way down to the beach I’d have to turn around and climb back up kept me from going any farther! It was a beautiful evening; I found three caches and thoroughly enjoyed my little hike.

Observation at Tapper’s Cove: if you’re going to put money into public art for your community, you should put some money aside for maintenance. Otherwise you get this Ghosts of Murals Past look:

Distance: about 2.5 km one way, 5K return.

June 2, 2015

ECT#1 — Father Troy’s Trail, Gallows Cove to Church Cove

I’ve decided one of the things I want to do this summer is see how much of the East Coast Trail I can hike. Unlike my Grand Concourse project from a few years ago, I’m not going to set any lofty goals like completing the whole trail network, because hiking trails are a much bigger committment and more time-consuming than walking trails, but I’m going to do what I can — aided and abetted by the fact that my lovely daughter has taken a part-time job in the town of Torbay, about a 20-minute drive from home and close to several trail access points. Tonight i started out alone and had an unexpected minor adventure on a short section of Father Troy’s trail from Gallows Cove to Church Cove.

I’ve decided one of the things I want to do this summer is see how much of the East Coast Trail I can hike. Unlike my Grand Concourse project from a few years ago, I’m not going to set any lofty goals like completing the whole trail network, because hiking trails are a much bigger committment and more time-consuming than walking trails, but I’m going to do what I can — aided and abetted by the fact that my lovely daughter has taken a part-time job in the town of Torbay, about a 20-minute drive from home and close to several trail access points. Tonight i started out alone and had an unexpected minor adventure on a short section of Father Troy’s trail from Gallows Cove to Church Cove.

I’d planned a short walk, about 20-25 minutes up the trail in one direction, then back to where I’d parked the car. However, it turned into a long hike because it was a beautiful evening on a lovely trail, and I was lured further on by the chance of finding a geocache.

I ended up hiking down and up much steeper trails than I’d intended. At one point I passed a sign that showed Father Troy’s trail continuing on ahead, with the “Church Cove Loop” (marked “Difficult”) veering off to the right. I’m not the sort of hiker who does well on “Difficult” trails, but the cache I was looking for was at Church Cove, so I thought I’d push on towards it.

I found myself heading down, down, down, then crossed a stream at the bottom of the lovely little waterfall where I snapped a picture. After that it was all up, up, up, clambering over steps cut in the rock, thinking “Was this really a good idea?” It was a much steeper and harder hike (almost a climb, by this time). The view from the top of Church Cove was worth it (and I found the cache) but I wasn’t looking forward to the climb back. I’d already been hiking for an hour now and figured it would take me even longer to get back.

Then, in the clearing at the top of Church Cove where the cache was hidden, I turned around, looked at the signs, and saw one pointing off to my left: “Father Troy’s Trail to Torbay.” The shorter, much easier route that I’d turned off of, ended up in the exact same place I had been heading for. I’d taken what turned out to be a much longer, tougher route to arrive at the very same spot.

There’s a life lesson in there somewhere!

I took the easy route back, of course. Look for more East Coast Trail updates over the coming months …

May 12, 2015

Shelf Esteem: Bookshelf Tour

Over on Tumblr, I often see book bloggers sharing beautifully shot photographs of their artfully arranged bookshelves, organized by colour, by theme, or some other clever scheme. My books are arranged by “whatever fits on that shelf” and the result is quite messy. Despite this, I decided to take friends and vlog viewers on a tour of (some of) the many bookshelves in my home. I also offer viewers a chance to pick out books for me to talk about in upcoming videos and even win a book, so play along!

April 25, 2015

All Will Be Well

This is the song I’ve been listening to over and over all week (since discovering it on the soundtrack of a Parks and Recreation episode).

Julian of Norwich, that odd medieval mystic, famously said “All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.” And this is a statement of faith that I hear quoted a lot, both from people who share Julian’s Christian faith and those who most emphatically don’t. It’s a statement that I love but find hard to believe.

As near as I can figure from my reading, when Julian said it she meant it in the broadest cosmic sense — in fact, she was probably expressing the theological idea that today we would call Universalism — that no-one will be lost, that God will, in the end, find a way to save all creation. This is an idea I found powerfully appealing (though not necessarily Scriptural) — but I think many of the Christians who like to quote this line might disagree with this idea.

A lot of people seem to use “all will be well” as general sort of assurance, a kind of “everything will work out in the end” when you’re going through hard times. I struggle with this, not least because it’s certainly not a kind of assurance Julian would have recognized. As a medieval mystic, she not only expected but welcomed suffering, another perspective not shared by most modern Christians. I assume many Christians who say “All will be well” today mean that somehow, God is in charge and things will pretty much work out, even though you might be having some tough times now.

Some days I believe that, but some days I don’t. I’ve lived a life blessedly free (so far) of shocking tragedies, but I see enough horrific tragedies and senseless losses in the lives of those around me that I find it hard to trust that God is going to just “work things out.” As for those who don’t have any religious faith but still quote this? I have no idea what they’re trusting. The universe? Karma? Either way, “all will be well” doesn’t seem to be working out very well for either the Christians or the atheists of my acquaintance — unthinkable tragedy seems to hit both groups equally.

So I’ll admit I struggle. I don’t see either God or a beneficent universe offering people any guarantees that everything will work out OK, which means that whenever someone says “All will be well,” my chattery inner voice jumps up and says, “Well, maybe it will and maybe it won’t, but it’s distinctly possible that God’s definition of ‘well’ may be incompatible with mine, and how ‘well’ did things work out for the parents of that poor kid who died last week, and and and and ….”

Suffice it to say I have a hard time drawing comfort from these words.

And yet, when I heard this song by the Gabe Dixon Band, I just fell into it like I fall into bed at the end of a hard day. It warmed me. It comforted me. I listen to it over and over again.

I’m a wordy person, but sometimes words need music with them for me. Especially if they’re going to connect to me at a level that goes deeper than my incessantly-analyzing rational mind.

When I hear people quote “All will be well,” I think “Yeah, but ….” When I hear Gabe Dixon sing “All will be well,” I feel it. I feel that all will be well. Maybe it’s because the song itself acknowledges that all-wellness is problematic — that the fight is just as frustrating as well, and sometimes this is hard to tell. But I think it’s just that music gets past my defenses. I know there’s no rational way to understand how “All will be well,” that I can’t pull out a signed contract from God or the Universe or Whoever guaranteeing that I and all those I love will be safe from major trauma and I will triumphantly overcome all obstacles. But when I sing along, I don’t need that. “All will be well” is not about the rational mind. It’s about something deeper and more inarticulate — an attitude that approaches this big, scary life with openness and hope rather than with fear and dread.

It’s true in a part of me that theology and reason can’t reach, but music can. All will be well.

April 23, 2015

How I Wound Up Having Tea at Government House

This week, we celebrated 90 years since Newfoundland women won the right to vote and run for public office. Here’s my video report on the celebration!

April 16, 2015

What is Common Knowledge?

I’ve been thinking about the question of “common knowledge” — things that everyone is supposed to know — a little this week, partly because of the “Friends” clip above and partly because I had another crack at the Jeopardy! Online Contestant test, which is always good for revealing how much “common knowledge” I actually don’t know.

Awhile back the whole ten seasons of “Friends” appeared on Netflix, and both our teenagers watched the series, which meant a lot of blasts from the past for me and Jason if we were in the room at the time. We relived not only the highs and lows of what was (in its early years) an extremely funny sitcom, but also the years of our own lives that unrolled while we watched that show (we dated, married, bought our house and had both our kids while Friends was on air, so we kind of grew into adulthood along with the characters).

One of the things that really struck me in re-watching the show was how aggressively anti-intellectual all the characters (except Ross, who has a PhD in Paleontology) are. Four of them (Ross, Chandler, Monica and Rachel) apparently have college degrees, but the things they don’t know, and the pride they take in not knowing those things, is sometimes staggering. This is exemplified in the clip above, where the three women make fun of Joey for not knowing who “we” (i.e. the US) fought in World War One, and then realize that they don’t know either, but think maybe it was Mexico.

This is jaw-droppingly ignorant, and I’m inclined to put it down to typical sitcom exaggeration — making characters look dumber than anyone could possibly be, for the sake of getting a laugh. But then I reflected a little more and thought, maybe it only seems staggeringly stupid to me because I have a history degree, teach history, and am a history geek. Maybe the question of who fought who in WWI is not actually general knowledge for most educated people? And that (along with trying the Jeopardy quiz) made me think — what’s actually included in “common knowledge”? What can most educated people be expected to know?

I would think that “Who did we fight in WWI?” would be a general-knowledge level question that most people can answer, while, “What were the terms of the Treaty of Versailles?” is a specialized-knowledge question that I’d expect only someone with a strong background in history to be able to answer (I would hope that my World History students could answer it on the days before and after the final exam, but I know most of them will forget it within a week).

I wondered, what about my “general knowledge” in areas I’m not particularly strong in? Science, for example. I studied Biology and Chem in high school and got good grades, did first-year Biology in university, and haven’t touched a science subject since then. I know that I have forgotten a lot of things I learned in those courses.

One of the Jeopardy Online questions was “Na is the symbol for this element,” which I knew immediately (sodium). But another (from a different night when I didn’t take the test) was “Generally this metal has to be at -37.93 degrees Farenheit to become a solid” and I would not have gotten that answer (mercury) within the allotted 15 seconds. I might have figured it out given more time, by asking myself, “Aren’t all metals solid anyway? What metal do we commonly see in a liquid state?” but I definitely would not have gotten there in 15 seconds.

Is that “common knowledge”? By definition the people who get on to Jeopardy! (and trivia buffs in general) have to have a knowledge base that’s at least a bit broader and deeper than the general population. But they don’t ask expert-level questions on Jeopardy — that is, not the kind of questions you’d have to answer if you were getting a degree in a subject.

So what all this thinking has taught me is — I don’t actually know what constitutes “General Knowledge” or “Common Knowledge.” I’d hate to think that I’m looking down on people, like Monica, Rachel, Joey and Phoebe, for not knowing things that seem obvious to me, if those things really aren’t common knowledge. (I don’t actually mind looking down on sitcom characters, but I’d hate to transfer that snobbery to real people). At the same time, I’d like to think that I know enough things, outside my own area of expertise, to avoid looking stupid about things like Math and Science, but I’m not really sure I do.

So I put it out to you, blogosphere and social media friends! What do YOU consider general knowledge, or common knowledge? Do YOU know who your country fought in World War One, without being a hardcore history junkie? How much do you know about subjects outside your own area of expertise? And just how dumb ARE the characters on Friends?