Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 56

August 11, 2014

August 11

My mom, Joan “Sue” (Ellis) Morgan, would have been 80 years old today. It never occurred to me that she would not live to be 80, and it seems trite to say I miss her every day, because I miss her several times every day.

I wish she had seen her 80th birthday but, as I see others of her generation growing older and hear about what friends experience with their aging parents, I’m well aware I would only wish that for her if she could have reached eighty years in good health and full independence.

In the “small mercies” category I will always be grateful that my mom remained fully herself and engaged with her life almost to the very moment of her death. In the “large blessings” category I am grateful for the 78 years of life she lived, the people she touched, and the unconditional love she always showed me.

August 6, 2014

Writing Wednesday 81 Book Talk: Cabin Edition

I was at the cabin and there weren’t a lot of books around, so I went for the cheap laughs in today’s video.

August 3, 2014

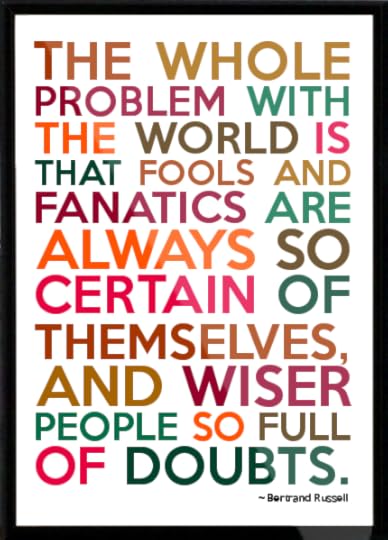

Certainty

A Facebook friend shared this on her wall the other day, and I find in looking around the web that it’s a favourite quote by that crusty old atheist Bertrand Russell (although it’s possible that the more accurate form of the quote is: “The fundamental cause of trouble in the world today is that the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” Same concept, anyway).

I’ve thought a lot about faith and doubt, certainty and uncertainty, lately. Mostly because of the crisis in Gaza, and the way my Facebook feed is flooded with posts by people who seem to know exactly who is to blame and exactly what they’re doing wrong. Judging by social media, about half my friends are convinced that the state of Israel is the evil empire harrassing innocent Palestinian civilians, while the other half is convinced that Hamas are murdering terrorists who will wipe Israel off the map given a chance.

And I just think, it’s awful. It’s so awful. I’m moved by the images of suffering in Gaza, and I hate even thinking about the whole Israel/Palestine situation — as I tell my students when we take a day or two to briefly glance at the topic in our overview of 20th century history, this is going to be the most depressing day of the whole course, because it’s an intractable problem that produces lots of violence and has no easy solutions.

But what I can’t get over is how sure people are, and how hard it is for me to grasp that kind of certainty. Is Israel doing terrible things in the occupied territories and violating the human rights of the Palenstinian people? Without doubt, it is. Would Hamas terrorists try to destroy Israel if the harsh Israeli rule was lifted? Almost certainly, yes. Are there legitimate claims and grievances on both sides? Yes. Has great evil been done by people on both sides? Absolutely.

And then I think (because I can’t think about Gaza too long and keep going on with my everyday life), I’m just this way about everything. I find it so hard to be sure of anything, and I can’t understand why people around me seem to find it so easy to take sides. Even something like abortion — my pro-life and my pro-choice friends are both so effortlessly certain that they’re right and I can’t even imagine having that kind of certainty about an issue where it seems so clear to me that both sides are absolutely right, and completely incompatible.

I’ve written in the past about doubt and the role that it plays in my spiritual life, how I’ve tried to become comfortable with not having all the answers and not knowing everything. Yet as I get older I feel less and less certain about everything — not just my faith but all these hot-topic issues that other people find it so easy to take sides on. I’d like to take solace in that Bertrand Russell quote and believe that I’m unsure of things because I’m so wise, but the fact is, many of the people I know who are absolutely certain about something are not fools. They’re pretty smart people, often much smarter and better-informed than I am. The problem is, equally smart people come down on the opposite side of the same question, leaving me no better off than before.

So I don’t think I’m wise exactly … I just think maybe there are certain types of brains that are more shaped for seeing all sides of an issue, and I have one of those, and it makes it hard to choose a definite side. And there are positive aspects to this, like empathy and, hopefully, being willing to listen and learn, as well as negative sides, like being wishy-washy and unsure sometimes.

I feel like this uncertainty is deepening with age — that as I approach age 50 I may be losing the ability to see in black and white at all, and viewing the world as an ever-shifting palette in infinite shades of grey.

Approaching 50 … shades of grey …

Fifty Shades of Grey is a terrible, terrible book and it will be a terrible movie. I utterly loathe this horrific waste of paper and pixels, and denounce it as a Christian, as a feminist, and, most importantly as a writer and a lover of literature.

What a relief! Apparently there are still a few things I can be certain about!!

July 30, 2014

Writing Wednesday 80 Book Talk: The Sunne in Splendour

Historical fiction is my genre, both to read and to write. In this week’s video I talk about the first grown-up book of historical fiction I ever read and loved, and how it still serves as a template for me as to how to incorporate your historical research into fiction. Sometimes it’s done badly; here it’s done well.

July 29, 2014

Also, I don’t think video actually killed the radio star

The image that accompanies this blog post is from a special edition of the young-adult novel Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell, which I picked up in the bookstore the other day. What makes this painting, “The Kiss,” special? It’s fan art — one of thousands of images created and shared online by a fan who loved the book, in this case an illustrator named Simini Blocker. A handful of these have been selected to appear in the endpapers of the new special edition of this wildly popular young adult novel.

The image that accompanies this blog post is from a special edition of the young-adult novel Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell, which I picked up in the bookstore the other day. What makes this painting, “The Kiss,” special? It’s fan art — one of thousands of images created and shared online by a fan who loved the book, in this case an illustrator named Simini Blocker. A handful of these have been selected to appear in the endpapers of the new special edition of this wildly popular young adult novel.

I’m on record as having enjoyed both Eleanor and Park and the other Rainbow Rowell novel I’ve read, Fangirl. But as much as I’ve enjoyed the novels, I’ve enjoyed Rainbow Rowell’s Tumblr just as much — not only for her Benedict Cumberbatch obsession, but for the generous and delighted way she shares the creative work than fans have come up with to celebrate her art. Including fan art in the new edition of the novel furthers the sense that the life of a novel continues outside and beyond the words the author put onto the page, into the creative work that readers spin out of it.

This is not a new phenomenon, of course — people have always responded creatively to works of art they love. But the internet age has made it possible for ordinary readers, not just professional artists, to share their fanfic, their fan art, their celebration of creativity, both with other fans and with the original creators. And I think that’s a wonderful thing. While not every book may inspire the kind of fan-art that a young-adult novel like Eleanor and Park does, while not every reader responds with visual art, while not every writer shares Rainbow Rowell’s eager willingness to enjoy and re-share the work that her readers have made … well, enough do to make me certain that we’re living in a very exciting time for books and readers.

We hear the opposite often enough. We hear that we’re living in the era of the death of books, the death of bookstores, the death of publishing, the death of reading. That the internet and e-books and self-publishing and the 140-character Twitterverse are sounding the death knell for the world that we readers and writers know and love.

Is that world changing? Changing too fast, sometimes, for us traditionalists to keep up? You bet your sweet bippy it is. Traditional publishers are struggling to keep their financial heads above water and taking fewer risks on new writers as a result. Bricks-and-mortar bookstores are closing, and people like me lament their loss while buying 90% of the books I read in digital format. People are reading different things, in different ways, than they have traditionally read, and writers and publishers and booksellers are scrambling to adjust. There have been, and will be, losses. Transitions are hard, and painful.

But. BUT.

People love stories. People will never ever stop loving stories. We are a storytelling, story-consuming species — in fact, that might be the very thing that makes us human.

Bookstore chains may go bankrupt. Publishers may merge and/or die. New writers may struggle to find readers. And yes, these are bad things, hard things, things that have to be navigated before new paths can be found.

But through it all, people will keep writing and telling and seeking out and reading and sharing stories. We will never stop doing this. We can’t stop.

And the very same technologies that threaten our old methods and patterns of telling and sharing stories, also make new methods available. And that is exciting. The losses are real but so are the gains.

In the pre-internet age, a beautiful, thoughtful, romantic story like Eleanor and Park would still have been published, still have found young-adult readers to fall in love with it. Some of those readers might still have drawn and painted pictures of the characters, made posters of their favourite quotes from the book. But they wouldn’t have shared them on Tumblr. They wouldn’t have shown them to the book’s writer (well, a few might have sent them to her by mail, but on the whole, not that many), and a generous and engaged writer wouldn’t have re-shared them with her other fans. The fact that a book is a collaboration between the writer and the reader, while always true, has never been as apparent, as open and celebrated, as it is in the internet age.

A project like the fan-art-decorated special edition of Eleanor and Park would not have happened in the pre-Internet era. And without downplaying any of the challenges this new age poses for books and the people who love them … I have to say this is a wonderful thing. A wonderful time to be a reader, and a writer.

And if anyone ever wants to make fan art based on one of my books, I’d be delighted.

July 23, 2014

Writing Wednesday 79 Book Talk: The Diviners

Margaret Laurence published The Diviners forty years ago. The five-minute video above talks about what I’ve learned from it, as a writer. This much longer written piece gives three more reasons why I think The Diviners is a great book.

July 17, 2014

Writing Wednesday 78: My Name is Asher Lev

It’s a day late, so it’s Writing Wednesday on Thursday, but hey, I’m on summer time. My Name is Asher Lev by Chaim Potok is one of my favourite novels and one of the books that influenced me most as a young adult. In this third installment of my summer Book Talk series I talk about what I’ve learned from it as a writer. If you’d like to read more of my thoughts about this book and how it influenced me, here’s a r

July 9, 2014

Writing Wednesday 77 Book Talk: Galore

For this week’s Book Talk, I picked the book that is probably my favourite novel ever by a Newfoundland writer: Michael Crummey’s Galore. As I say in the video, it’s hard to describe this novel without using the words “sweeping” and “epic” because it is, well, a sweeping epic about a century of life in a Newfoundland outport.

What I love about this book is Crummey’s brilliant use of language, of which I give a few examples in the video. I have kind of an ambiguous relationship with a lot of literary fiction, because while I love writing where the language is carefully crafted and lovely, I don’t like it when a writer pays attention to language at the expense of plot or character development. If it’s nothing but lovely language, it might as well be poetry, and while poetry is beautiful, that’s not what I look for when I pick up a novel. For me, Galore is a nearly-perfect book because it marries wonderful writing with great characters and a compelling story.

July 5, 2014

How the Straightest Woman in the World Ended Up at a Pride Event

OK, two disclaimers: first of all, I say “ended up at” as if the event is already in the past, when in fact it’s in the future — I want to talk about it before I do it. (Fair warning: I may feel the need to talk about it afterwards as well). To be specific, it’s a panel discussion called “OUT in Faith: A Discussion on LGBTQ+ People and Spirituality,” it’s sponsored by St. John’s Pride, and it’s being held Monday night, July 14, at the Rocket Room.

OK, two disclaimers: first of all, I say “ended up at” as if the event is already in the past, when in fact it’s in the future — I want to talk about it before I do it. (Fair warning: I may feel the need to talk about it afterwards as well). To be specific, it’s a panel discussion called “OUT in Faith: A Discussion on LGBTQ+ People and Spirituality,” it’s sponsored by St. John’s Pride, and it’s being held Monday night, July 14, at the Rocket Room.

Second, you might want to dispute my claim that I’m the straightest woman in the world, and I’ll admit that I haven’t actually won a competition in this area (how interesting that would be, though!). However, I am an extremely heterosexual and extremely cisgendered person to be involved in any way, much less speaking at, a Pride Week event. (I’m also the whitest person you know and the most middle-class person you know, but since race and class are less relevant here I won’t continue to bore you with the million and one ways in which I am bland, boring and vanilla).

So, how I came to get involved in this, is that a person I greatly respect, Matt Caravan (who is a bona fide gay person and quite active in St. John’s Pride) asked myself and another person I greatly respect, Reverend Robert Cooke (an Anglican clergyman who is thoughtful and progressive about a lot of interesting issues) to help out with organizing and planning an event during Pride Week that would focus on LGBTQ+ people and spirituality. I was interested in participating because, as you probably know from my numerous previous blog posts on the subject, the question of how we church people relate to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people is an issue that I think we need to be having lots of conversations about, and here was an opportunity to have such a conversation.

I did not, at first, grasp that I had actually been asked to speak at this event. And when I did grasp that, my response was, well, what do I have to say that anyone wants/needs to hear? The voices that we need to be listening to are those of people within the LGBT community who have, in many cases, struggled to reconcile their sexuality and their spirituality. And I was interested to hear what Robert had to say, speaking from the perspective of a clergyperson who is affirming towards LGBT individuals. But me? This is a conversation where I need to be a listener, not a speaker.

But as it turns out I will be speaking – very briefly, like for 5 minutes — next Monday night, about my own journey as someone in a conservative Christian denomination and how I’ve moved through trying to be tolerant, to acceptance, to (trying to be) a more outspoken ally of LGBT people in our communities. I’ll talk a little bit about what I think conservative Christians, those of us whose churches have not rethought and are not likely (anytime soon) to re-think their stance on these issues, need to be doing in our encounters with LGBT people. And most of what I think we need to be doing is listening, which is why I’ll very quickly be stepping back from the microphone to make way for some more interesting speakers — people who will talk about their own challenges in reconciling (or not) their faith and their sexuality. Then things will open up to a general discussion in which anyone attending can join in and share their experiences, their thoughts, their questions. I hope it’s going to be a really interesting and challenging evening, from all possible perspectives.

So to get back to why I’m involved with it — like I said, I initially agreed because Matt and Robert are both people I have so much respect for, but also because this is an issue I feel more and more of a burden to speak out on. The few friends who’ve followed my blog closely for a long time know that this burden goes back several years — back to the first time I blogged about “coming out” as an ally of LGBT people, certainly back to before my friend Jamie died. In the last year, within my own denomination, I have been discouraged by events like the church’s Capetown conference on sexuality that excluded so many LGBT voices from the discussion, and the recent church guidelines on sexuality that many fear will make it easier for churches to disfellowship openly gay and lesbian members.

At the same time as our church leadership has been doing these discouraging things, I’ve been so encouraged by grassroots movements like the Seventh Gay Adventists movie, or the discussion held at my alma mater, Andrews University, with, not just about, LGBT students. And what all the encouraging moments have in common is that they involve being with people, listening to their stories, treating them as equals rather than as a problem to be solved.

I know that some people’s views about “traditional marriage” (problematic as that term is) are rooted not in ignorance and prejudice but in genuine theological beliefs related to how they interpret the Bible. And that’s not something that I’m going to change. I’m no theologian (though I can recommend some). I’ve long since decided that my role in this discussion is not to try to convince people to change their beliefs — I can’t do that. I just want to encourage people to listen to each other. And the “OUT in Faith” discussion seems like it will be a wonderful opportunity to do that.

So if you’re in the St. John’s area, and if you’re at all interested in issues around faith and LGBT people, I hope you’ll come out and listen to people talk about their experiences.

July 2, 2014

WW76 Book Talk: To Kill a Mockingbird

I’m looking forward to making this series of summer videos talking about books I’ve loved. This week: To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee. Next week: Newfoundland writer Michael Crummey’s epic saga Galore.