Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 59

March 12, 2014

Writing Wednesday 66: Judge and Be Judged

Today — a few thoughts about writing contests. I think entering your writing in a contest is a great idea. I also think it’s really important not to pin too much on winning these contests, because the entire judging process is so subjective, and full of things you can’t control — like the quality of other people’s entries. In this video I talk about being on both side of the contest-judging fence, and what I’ve learned.

March 10, 2014

Upcoming Event!

My cousin Jennifer Morgan and I are doing an artist talk together this Wednesday evening at the Red Ochre Gallery here in St. John’s, where Jennifer has an exhibit of prints based on the same collection of Coley’s Point postcards that inspired my book That Forgetful Shore (enough links in that sentence fer ya?). We were interviewed on CBC Radio’s Weekend Arts Magazine about it, and I put together this video of the postcards and some of Jennifer’s prints to accompany the audio of our interview. Hopefully it gives you a little foretaste of what you’re doing and perhaps, if you’re in the local area, you might want to drop down and see us this Wednesday night at 7:30 p.m.

March 7, 2014

Time for a music video …

March 2, 2014

Dogs, Walks, and Mindfulness

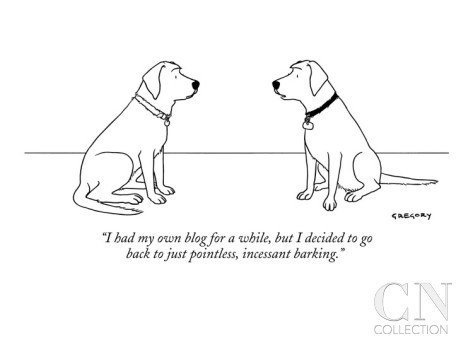

A Facebook friend posted this image the other day … one of those “wise thoughts” that looks great until you start to over-analyze it.

It’s a lovely idea, isn’t it? Ah, animals, they are so wise in their simple ability to focus on the here and now. Our human minds are cluttered with distractions and to-do lists, while the dog is entirely in the moment.

Except, has the person who drew this cartoon ever actually taken a live dog for a walk?

I can tell you, when Max and I go walking, my brain is exactly like the brain of the human in the cartoon — full of a crazy tangle of thoughts, ideas, worries and trivia. But Max’s brain is full too. Instead of trotting placidily by my side like the dog in the cartoon (OFF-LEASH might I add — is this dog well-trained or lobotomized? Max wouldn’t even be in the cartoon without a leash!), Max is sniffing every plant, rock and blade of grass (or, if we’re walking in our neighbourhood as is more usual, every car tire and fencepost). I assume his thought bubble would be saying something like “Oooh, someone peed here! Who peed here? Can I pee here? Or over there? Yes, I’ll pee there! Wait, who peed here? What was that? WHAT WAS THAT?! Should I chase it? Will it chase me? Am I predator or prey? I can’t remember!!! Oooh, someone peed here!”

My dog is, in fact, a lot more like Allie Brosh’s “simple dog” (please, please read her Hyperbole and a Half cartoon about the simple dog if you haven’t already) than like the Zen dog in the cartoon — he’s “simple” but not in the “mindfulness” sense.

My dog’s brain is full of thoughts that are presumably useful for canines in the wild, where it’s important to know what’s prey, who’s a predator, and whether this is your territory or has been marked by another animal. All this information is completely useless (though, I hope, entertaining) to Max. No matter whose territory we walk through or how many bushes he pees on, he’s coming home with me. He can bark at the neighbour’s cat and scare it up a tree, but when we get home he’s still getting dry dog food for his supper despite his best attempts at hunting behavior. His mind is chock-full of utterly pointless information.

My dog’s brain is full of thoughts that are presumably useful for canines in the wild, where it’s important to know what’s prey, who’s a predator, and whether this is your territory or has been marked by another animal. All this information is completely useless (though, I hope, entertaining) to Max. No matter whose territory we walk through or how many bushes he pees on, he’s coming home with me. He can bark at the neighbour’s cat and scare it up a tree, but when we get home he’s still getting dry dog food for his supper despite his best attempts at hunting behavior. His mind is chock-full of utterly pointless information.

My brain, on the other hand, is 99.5% full of useless information, but it’s worth having it there for the sake of the other 0.5% percent. This is where I kind of part ways with the “mindfulness” thing. As a person with a counselling psych degree, and as Christian who tries to be open to and learn from other traditions, I do think there’s a lot of wisdom in this whole mindfulness, “Be Here Now” kind of philosophy that (some) Buddhists and (some) therapists talk about. If I’m constantly caught up in worrying over the future or regretting the past I’m not living fully in the present or fully connecting with the people I’m present with. I get that, and I strive to improve it.

But some people who are into mindfulness take it to the point of saying that when you wash a dish, you should focus only on the dish and the act of washing. Be completely in the moment, not distracted by your thoughts. When you walk, be totally absorbed in the walk: quiet your mind. Now, that’s nice sometimes, and I do think it’s a shame if you’re so locked into your own crazy head that you don’t even notice the landscape or the cityscape you’re walking through, or take time to enjoy the beauty of the day. But to be 100% focused on just the walk, everytime I go for a walk? That’d be such a waste, because going for a walk is some of my most productive thinking time.

Yes, when I’m going for a walk, 99.5% of what goes through my head is pointless trivia or useless worry or inane observations. But somewhere amidst all that is the other 0.5% where I might unlock the secret to a knotty problem that’s been bothering me … or have a great inspiration … or figure out what to do next in my novel. Many of my best ideas (as well as some of my worst ones) have come to me while walking. I wrote half this blog entry in my head while walking this morning … and other half while washing dishes. Too much mindfulness, and there wouldn’t have been a blog today. Which might not be a great loss to literature, but I’m glad I had those thoughts while walking, and wrote them down.

Max wasn’t with me on this morning’s walk. But if he had been, as he usually is — well, I doubt he’d have come up a great blog post. I wouldn’t trade my frantic human brain for his canine one, even if I did believe it would bring me inner peace. On the other hand, if he could respond, Max might say:

(Note: cartoon credits to Alex Gregory for “pointless incessant barking” and to the inimitable Allie Brosh for “the simple dog.” Cartoon credits AND apologies to Henck van Bilsen, from whose blog the “Mind Full or Mindful” cartoon comes. If Mr. van Bilsen ever reads this I hope he isn’t offended … I actually do get the point he’s making and he may well have a dog and know lots about dog behavior! I’ve just used his cartoon in a teasing sort of way to unravel some thoughts of my own … and Max’s).

February 26, 2014

Writing Wednesday 64: How to Begin

What’s the best way to write the opening scene of a book?

Many thanks to my kids’ old Tickle-Me-Elmo, who was unearthed and put in a give-away bag just before I made this video. The video gave the opportunity to bring him out for one last hurrah as I needed a co-star.

February 22, 2014

I may take up reviewing movies …

… but it’s unlikely. I don’t even go to that many movies, and I have a full-time hobby just reading and reviewing books. So it’s unlikely I’ll branch out into movie reviews anytime soon.

But occasionally I see a film and think, “More people should see this!” and want to share about it on my blog. One such film is Seventh-Gay Adventists: A Film About Faith on the Margins. Check out the trailer, below, and then I’ll tell you why I think you should see it:

1. If (like many of my friends) you’re a Christian who believes in the traditional view of marriage and you’re worried about the growing trend in society to accept gays and lesbians and same-sex marriage as normal, you should see this movie. Why? Not because it will change your mind; it almost certainly won’t. It’s not an argument or debate-type movie. You should see it because it tells the stories of gay and lesbian Christians whose lives have been affected by traditional church teachings and beliefs about homosexuality. It puts a human face on what might otherwise just be the “Other Side” in an intellectual or theological debate. Since your religion (and mine) calls us to love, we owe it to ourselves and others to think hard about how to love those with whom we disagree. You can’t love people theoretically. You have to see their faces, hear their voices and stories, before you can grapple with what love looks like in a particular context.

2. If (like many of my other friends) you’re a completely secular person who takes it for granted that LGBT people have the same rights as straight people, and can’t understand why religious people are dragging their heels, you should see this movie. Even if (perhaps especially if?) you’re gay or lesbian yourself, and have no ties to organized religion — maybe even have a great deal of contempt for it. Yes, religions (all religions!) have a pretty bad track record with the LGBT community. Watching this film may give you a different perspective, might help you understand why some people choose to cling to their faith, what an important cornerstone of life it is for them, even when it brings them into conflict over their sexuality.

3. If (like me) you are a Christian who questions the traditional definition of marriage (or at least the often hypocritical way in which it’s applied in the church), and you want to be an ally for your LGBT brothers and sisters, you should see this movie. Especially if your LGBT brothers and sisters are literally your brother or your sister — or your uncle, or your mom, or your best friend, or anyone you care about. Maybe you’ve heard stories like the ones in this movie many times. Or maybe you haven’t, because the people you love haven’t talked to you about their experiences. Hearing these stories will open your heart even further, and make you realize how important this struggle really is. Maybe, like me, you’ll emerge from the experience realizing that you need to be more outspoken, more pro-active, in supporting those who are truly “the least of these” in our congregations and church fellowship halls, or on our missing-member lists.

While it’s a film set firmly within the context of the Seventh-day Adventist community (and there are definitely some SDA in-group references, like “What’s not to love about haystacks?”) this film is relevant to everyone who’s ever been part of any faith community, because gay and lesbian people exist in every church and temple and gathering place, and as this film clearly shows, ignoring “the problem” in hopes that it’ll go away, isn’t enough.

Particularly if you’re in Category #1 above, I urge you to see this movie — not because I expect it to change the way you read Scripture — it doesn’t even attempt to do that. But because I believe listening is so important, and love is impossible without it. It’s possible to love people and sincerely disagree with them, about lots of issues. It’s not possible to love people while ignoring them and refusing to hear their stories.

There are lots of ways to get hold of this movie. If all else fails, I have a copy. Borrow mine.

February 19, 2014

Writing Wednesday 64: Ten More Questions

I did sort of a fun thing this past week. The local paper, The Telegram, runs a weekly feature in which they select someone from the community — an artist, a businessperson, someone who works with a community agency, anyone at all — and throw twenty random questions at them. I find it an interesting little get-to-know-you piece each week, and this week I was honoured to be the “20 Questions” person. You can read the piece here.

It got me thinking: there are other, equally random questions that I’d like to answer, but rarely get asked. So I decided to interview myself for this week’s video — questions I would have liked to answer but didn’t.

February 12, 2014

Writing Wednesday 63: The Plot Thickens. Or does it?

February 6, 2014

Use Your Words

Sorry, no Writing Wednesday this week –I had some good ideas, but didn’t get myself organized in time. But I realized that in the last few weeks of Wednesday videos, I’ve shared a few interesting pieces of writing-related news that might have been missed by people who read my blog but don’t watch my videos. Of course my dream is that EVERYBODY is watching my videos but I do understand that not everyone has the time or bandwidth to click on a YouTube video every week. So I decided to use my (written) words and write a post bringing you up to speed on some of my news:

1. A Sudden Sun has been accepted by Breakwater Books for publication in the fall of 2014. Again, I’ve talked a lot about this book project on the vlog and probably a lot less here in written form, but this is the novel I’ve been working on for the last year. It’s a historical novel about two women, a mother and daughter, who are separately involved with the campaign for women’s votes in Newfoundland in the 1890s and the 1920s. It’s about a lot more than that, but that’s my thumbnail sketch. I’m very pleased to have a third Newfoundland historical novel coming out with Breakwater, a publisher I’ve really enjoyed working with over these last few years.

2. The Violent Friendship of Esther Johnson is now available as an e-book. This novel about the woman best known to literary history as Jonathan Swift’s friend “Stella” was published by Penguin Books Canada in 2006 but has been out of print for a few years. You can now get it for Kindle at amazon.com, amazon.ca and other Amazon stores, and will soon(ish) be available for other e-readers as well. This book was my first serious foray into writing historical fiction (my book about the “other” Esther, the Biblical queen, was released before this one, but written later). While The Violent Friendship never got the wide sales in print that every writer hopes for, I have had a lot of readers tell me they loved it over the years. If you like historical fiction woven around the lives of real women who lived in the shadow of great men, you should check out my book! Here’s the link for Amazon.com in the US but you can find it on any Amazon site, I think.

2. The Violent Friendship of Esther Johnson is now available as an e-book. This novel about the woman best known to literary history as Jonathan Swift’s friend “Stella” was published by Penguin Books Canada in 2006 but has been out of print for a few years. You can now get it for Kindle at amazon.com, amazon.ca and other Amazon stores, and will soon(ish) be available for other e-readers as well. This book was my first serious foray into writing historical fiction (my book about the “other” Esther, the Biblical queen, was released before this one, but written later). While The Violent Friendship never got the wide sales in print that every writer hopes for, I have had a lot of readers tell me they loved it over the years. If you like historical fiction woven around the lives of real women who lived in the shadow of great men, you should check out my book! Here’s the link for Amazon.com in the US but you can find it on any Amazon site, I think.

3. Upcoming event to talk about That Forgetful Shore. Years ago when I first began writing That Forgetful Shore, I asked my cousin Jennifer, whose parents owned the old family home at Coley’s Point, if she had the collection of postcards that had belonged to our great-great-aunt Emma Morgan — the postcards that had initially inspired me to write the novel. Much to my amusement she delivered them in a cardboard box on which her mother, novelist Bernice Morgan, had written in Sharpie marker: “This is valuable stuff — from Coley’s Point — will make a novel or an art exhibit one day.” She wasn’t wrong. Not only did I write a postcard inspired by those novels, Jennifer now has a display of prints on exhibit at the Red Ochre Gallery on Duckworth St. in St. John’s, inspired by those same postcards. On Wednesday evening, March 12, at 7:30 p.m. she and I will be giivng a talk at the gallery about the postcards and how we used them in our work. I’m really looking forward to this event!