Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 51

September 17, 2015

Because of My Religion…

I think I was probably about nine years old the first time I asked to be exempted from something for religious reasons. Like most Seventh-day Adventist kids, I was taught early how to do this: to say respectfully, “I’m sorry, I can’t do that because it’s on Saturday. I’m a Seventh-day Adventist, and we observe Saturday as the Sabbath.”

I got, as I have done most times since then, a blank look. If I remember correctly the person giving me the blank look was my piano teacher — I believe I was explaining why I couldn’t play in a Saturday recital. She said, “Can’t you just ask your minister or your priest if it’s OK for you to play on Saturday?”

I wrestled with finding the right words — how to explain, as a child, something that I intuitively understood but an adult did not? How to put into words that this had nothing to do with obeying a religious authority figure or getting permission, but with inner conviction that would make Sabbath a special day regardless of what any clergy person said? I told her that wouldn’t work and I wouldn’t be able to play, and I missed the recital.

It was the first of many times I was to enact this tiny drama. Since I went to a Seventh-day Adventist school and eventually to a church-run college, I had to do this far less than Adventist kids who went to public school did, but I had to explain over and over why I couldn’t attend everything from piano recitals to final exams (the year I attended public university) “because of my religion.”

Ah, the things we can and can’t do because of our religion. Is there a hotter topic in the news right now? Kim Davis can’t have her name appear on the marriage license for a same-sex couple because of her religion, even if she goes to jail for it. Zunera Ishaq needs to appear in her niqab at her citizenship ceremony because of her religion, even if it means going covered-head-to-uncovered-head with a prime minister desperate for a distracting fake-issue to save his campaign. Ranee Panjabi won’t wear a recording device to broadcast her lectures to a hard-of-hearing student because of her religion, even if it earns her the incensed derision of the entire province of Newfoundland.

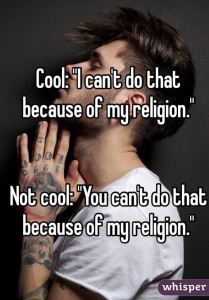

The meme at the top of this post has been popular lately, although for my own purposes I’d rephrase it to: “I CHOOSE NOT TO … because of my religion.” I don’t think any mature person should say “I can’t…” as if to imply there’s an immovable force stopping us from breaking the laws of our religion. Of course we could do it — I could go to committee meetings, or do readings from my books, or pick up my groceries on Sabbath, but I choose not to. And most of us would agree that freedom of religion doesn’t give us the right to impose our religious rules on other people. I can’t tell other writers not to hold a literary event on Saturday just because I choose not to attend.

But it’s not that simple, is it? Just let everyone practice their own religion in peace and don’t interfere, and we’ll all be happy. Except that there are many, many cases where my right to practice my religion might interfere with the free exercise of someone else’s rights. And what do we do then? How do we decide which right trumps another?

There’s not a lot of respect in the population as a whole for people who refuse to do something “for religious reasons,” especially if that religious belief is unpopular or unfamiliar or in any way viewed as strange. The brand of Christianity that leads Kim Davis to disapprove of same-sex marriage is very well-respected and approved of among those who share it, but vilified by almost everyone else as homophobic, backward and ignorant. Zunera Ishaq is a Muslim woman who wears the niqab: in lots of Canadian minds (including that of Stephen Harper, apparently), that makes her something dangerously close to an ISIS terrorist, and we have to unveil her to make sure she’s just an ordinary immigrant who wants to be Canadian. As for Ranee Panjabi, nobody understands what kind of weird whack-job mysticism won’t let you wear a microphone — could she just be making the whole thing up? These are the attitudes floating around social media — not a lot of tolerance for religious beliefs if they are odd, or obscure, or inconvenient.

The fact is, if I pass up the opportunity to do a reading for my book because it’s on Friday night (or for that matter if I passed up the chance to play in a piano recital when I was nine), it inconveniences nobody but myself. And in my view, the value of having a sacred day of rest once a week that nothing is allowed to impinge on, more than makes up for the inconvenience of missing out on a single event now and then.

But what if my workplace decided it could better serve students by offering classes on Saturdays? I would ask to be excused, take a cut in pay and have another instructor cover my Saturday classes. But sooner or later a student would complain that their education was being compromised by having a substitute teacher in once a week, and they’d be right. What then? When my right to practice my religion conflicts with the student’s right to an education, what do we do? I teach in a private charitable institution (although we do receive government funding). Would the answer be different if I taught in a fully government-funded public school?

Kim Davis’s desire to preserve what she sees as a traditional definition of marriage conflicts with the right of same-sex couples in Kentucky to be legally married. Ranee Panjabi’s right to refrain from wearing a recording device conflicts with William Sears’ right to receive accommodation for his hearing impairment at our public university. I’m not sure whose rights are being violated if Zunera Ishaq wears her niqab when she becomes a Canadian citizen, but Stephen Harper is pretty darn sure somebody’s rights are being violated — maybe the rights of all Canadians to look each other right in the face at all times?

I don’t want to belittle any of these rights — on either side — even though there’s plenty of belittling going on in the press and social media, and in thousands of water-cooler conversations that swirl around these controversies. As a person who’s spent my whole life asking for religious exemptions, I’m used to missing opportunities and inconveniencing myself in pursuit of what I see as a greater good. But does my right to religious freedom allow me to inconvenience someone else and perhaps even deny their legal rights — when the tenets of my religion, like that of practically every other religion, place a high priority on loving, helping and serving others above myself?

Did you think this blog post was going to end with answers? That something in my experience was going to give me a key to unlock a problem that is only becoming more tangly as our society becomes more controversial? I think I might have thought that when I started, but I can’t write or think my way out of this. I have no easy answers, only the certainty that the answers aren’t as easy and obvious as people would like them to be.

I know this much: people who say “I can’t — or I won’t, or I choose not to — do this because of my religion,” never say that lightly. They have learned and practiced those words for a long time, and they have missed out on opportunities and put up with inconvenience, for reasons that make sense to them but often don’t make sense to other people. Anyone who claims a religious exemption from doing something others take for granted — whether it’s signing a document, or showing her face, or wearing a microphone, or working on Saturday — has already had plenty of experience with questions, doubt, disbelief, and ridicule. And she is braced for plenty more of that.

But at the same time, such a person’s sincerely held belief — mine included — and the legal right to hold that belief, doesn’t trump everyone else’s rights. That’s where it gets hard, and messy, and compromises have to be made. In lots of cases, compromises can be found that will make both sides happy. But let’s not kid ourselves: this won’t happen every time. Sometimes, sincerely held religious belief means that a person has to say, “I can’t do this job; I need to resign” (which, if you’re wondering, is what I would do in the hypothetical situation above if I were required to teach on Saturday, and the accommodation of providing a substitute teacher was deemed inadequate to serve the students’ needs).

This business of “freedom of religion” may have seemed straightforward once upon a time in North America, when the vast majority of people practiced one of the mainstream variations of Christianity and even non-believers accepted the values of that religions as normative (though even then, Seventh-day Adventists were losing their jobs for refusing to work on Sabbath). The thing is, for better or for worse, we don’t live in that world anymore. I think it’s for better, because I love diversity. But diversity brings problems that aren’t easily solved.

Diversity brings Muslim women who we may think are oppressed behind their niqabs, but who insist that they are making a free choice they have every right to make. It brings mystical Hindus who don’t want to wear recording devices even though we have trouble understanding why. It brings secular people who are no longer willing to live by the dictates and definitions of a Christianity they don’t practice. And it brings all of us rubbing shoulders with each other, trying to get along. And mostly, we suck at that, as is demonstrated every time you bring up one of the above news stories and listen to what the people around you have to say. Listen, in fact, to your own voice.

It’s possible to disagree respectfully, but most of us are not very good at it. It’s possible to seek compromises, but compromise only works if we accept that people on both sides have rights that need to be valued — and that includes the right of people to practice their religion, even religions we don’t understand or agree with. On the flip side, compromise only works if we religious people accept that our right to practice our religion doesn’t mean we’ll always get what we want, or that we can ignore the rights of others.

It’s tough and it’s messy, and all our religions say that we ought to be nice to each other as we’re working it out. Why is that so hard to do?

September 3, 2015

Quote Unquote

Several years ago, on this very blog, I wrote an angry rant about the trend of literary fiction writers dropping the use of quotation marks. In the years since, I still haven’t embraced the trend, but I’m maybe a little less angry. I decided to use my latest Shelf Esteem video to explore this phenomenon and see how widespread it really is. It does get a bit angry at one point, but only at Cormac McCarthy.

September 2, 2015

Quebec City Revisited

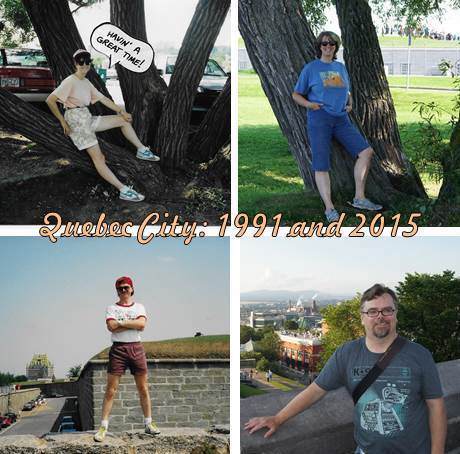

So, almost everyone who knows me in real life knows this story, at least if you’ve known me long enough. But I don’t know if I’ve ever blogged about it — certainly not in recent years — and it seems timely to tell, or re-tell, this story now.

A couple of weeks ago Jason and I celebrated our 20th wedding anniversary with a trip to Quebec City, where we stayed at the famous (and fabulously overpriced) Chateau Frontenac hotel. We had a wonderful time walking the streets of Old Quebec, eating crepes and fondue, swimming in the hotel pool and generally relaxing/sightseeing. But there’s a very significant reason why I picked Quebec for our anniversary trip and why we had to stay in the Frontenac regardless of the cost, and it goes back more than 20 years, to the summer of 1991.

Jason and I were in our mid-20s then and we had been dating for about six or seven months. However, I was convinced this was not a serious relationship with much of a future. While we had a great time (and most importantly a great laugh) together, I was planning to leave St. John’s at the end of August for a job in Alberta. I didn’t know if this relationship had what it took to survive long distance; I liked him, but wasn’t sure how serious I was about him. I thought me moving away might provide a nice natural ending to things, and we’d both move on.

All that year, Jason and I had both been counsellors in our church’s Pathfinder Club for kids ages 10-15, and during the summer the club took a trip to Quebec for an Eastern Canada Pathfinder Camporee. We spent four days driving to Quebec on a school bus loaded with with kids singing at the top of their lungs, and a bus driver who didn’t believe in bathroom stops. Then we all went to stay at the Seventh-day Adventist church camp in Val d’Espoir, Quebec, a not-very-lovely campsite in the middle of nowhere where the 30C temperatures were exacerbated by the heavy, old-fashioned canvas tents we had to sleep in. It was, to put it mildly, not a dream vacation.

One day the Pathfinders were scheduled to climb back on the bus and go into Quebec City for a tour of the old city. That morning I woke up with a stomach bug — just what I needed to make that trip even more perfect. I didn’t want to stay back at the campsite and be sick alone, so, gambling that I would feel better as the day went on, I got on the bus with everyone else and drove into Quebec City.

My gamble did not pay off. As soon as we got off the bus near the Citadelle, I was sick again. I threw up into a plastic bag that another leader had helpfully given me for that purpose. When I looked up from barfing into the Sobey’s bag, I was surprised to see Jason standing beside me. I was even more surprised when he took the bag of barf from my hands and said, “Are you OK? I’ll take care of that.”

I watched my boyfriend walk away with a plastic bag full of my vomit to dispose of it in a garbage can, and I thought, This guy is a keeper.

I didn’t feel better as the day went on, and after dragging myself with the group of kids around the Citadelle walkway (and posing for a picture, above, in which I look much happier than I was — the caption was intended to be ironic), I knew I couldn’t go on for the rest of the tour. We were near the fabulous, elegant and air-conditioned Chateau Frontenac and Jason suggested that I wait in the hotel lobby for the group to finish the tour, where I could throw up in their lovely washrooms if needed. He went off shepherding Pathfinders while I huddled in misery in the nicest hotel lobby I’d ever been sick in.

Some girls are impressed by roses, diamonds, poetry. Some girls like flashy cars and big bank accounts. I was, and remain, impressed by a guy who’s willing to step up and do the dirty work. The guy who carries the bag of vomit, I thought that day, is probably the guy who will clean the floor when the dog gets sick; who will change the baby’s diaper; who will genuinely be there in sickness and in health. And so far, 20+ years later, I’ve been right about all those things. He was, and is, a keeper, and he’s there for the bad times as well as the good, and we’ve been able to laugh through it all.

I decided that someday, maybe on an important anniversary, Jason and I would go back to Quebec without anyone else’s noisy kids — even without our own! — and stay in the Chateau Frontenac, and nobody would get sick, and we would see that beautiful city as it was meant to be seen and celebrate a relationship that did turn out to be for the long haul after all. Because greater love hath no man than this, than to dispose of a bag of puke for you. Remember that, young ladies, and don’t be led astray by bronzed biceps and a fancy car. Go for the guy who’s there when things get messy; he’s the one you can count on. I know I do, every day.

August 18, 2015

Solvitur Ambulando (and Why I Didn’t Get a Tattoo)

Among the things I’ve always known about myself, one biggie is that I’ve never wanted a tattoo. Not that this was a tough choice when I was a young adult and only sailors and really hardcore punks got tattoos. But now that everyone’s doing it, I have had to reinforce several times in conversation with others that I never, ever, ever want to get a tattoo.

Among the things I’ve always known about myself, one biggie is that I’ve never wanted a tattoo. Not that this was a tough choice when I was a young adult and only sailors and really hardcore punks got tattoos. But now that everyone’s doing it, I have had to reinforce several times in conversation with others that I never, ever, ever want to get a tattoo.

But a few months ago while I was out walking I thought about the Latin phrase “Solvitur Ambulando” and thought, “I wonder if I should get that tattooed on my ankle when I turn 50?”

“Solvitur Ambulando” means “It is solved by walking,” and the phrase is meaningful to me on a lot of levels. First, on a purely literal level. I believe a lot of life problems, mental and physical, can be solved by walking. Go for a walk and clear out the cobwebs. If you can’t do anything else at least get off the couch and go for a walk (no offense intended to those unable to walk, obviously). I’ve always enjoyed walking and as you know from this summer’s blogs I am trying to add more trail hiking into my routine as well. Walking solves a lot of problems.

But I also find it true on a metaphorical level, as a guide for how to get through life, especially as I’m definitely past the midpoint of that life thing now. When I think “It is solved by walking,” I think of a few of my favourite quotes:

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow

I learn by going where I have to go. (Theodore Roethke, “The Waking”)

We walk by faith, not by sight. (2 Corinthians 5:7)

Travelers, there is no path. The path is made by walking. (Antonio Machado)

The (so far, very small handful of) people who’ve read my recent novel What You Want will recognize that two of those three quotes are sent to my character Megan by different people as she’s trying to figure out what to do next with her life. (I would have used all three quotes in the novel, but that’s what we in the business call Hitting the Reader Over the Head With the Theme, so I held back).

Although there’s a lot of me in every character I write about, Megan, in the novel, is very different from me in some key ways. At 23, she’s uncertain and doesn’t know what she really wants in life. When I was 23 I was absolutely certain about … well, almost everything. I knew what I wanted and how I was going to get it. Some people, like Megan, have to gradually figure out their life’s purpose. Others, like me, come out of the womb 100% sure of everything — and have to spend the rest of life unlearning all the things we thought we knew.

At 50, I am so much less sure of things than I was in my teens or twenties. I may not have thought I had all the answers then, but I certainly thought I had a lot of them and I knew where to find the others (not Google. We didn’t have Google then, children).

This is especially true for me in the spiritual realm. Half a lifetime ago, when I was 25, I thought I knew a lot about God, faith, the Bible and what God was calling me to do. Now I know almost none of that. I am figuring things out as I go. “Solvitur Ambulando” is more true for me in the walk of faith than anywhere else. I don’t know the answers. I don’t have the path all mapped out. But I won’t figure anything out by sitting down theorizing about it. I get out and try to live the life of faith. I put one foot in front of another. I show up trying to love God and love my neighbour and failing and learning. The path is made by walking.

It’s true in every other area of life too. When I was in my early 30s, becoming a parent was terrifying. I went to the hospital and these tiny people came out of my body and a couple of days later the nurses handed them over to me to take home as if Jason and I had any idea what to do with completely helpless infant humans! As if we knew how to keep them alive and make them grow up big and strong.

Now they are big and strong, almost adults, and — parenting is still completely terrifying. Even more so because they are making their own path by walking and I cannot guide or control as much as I used to! Everything is uncertain. Everything is scary. And the only way to learn anything — parenting, or teaching, or writing, or following God, or being a decent human being — is just to do it. To try and fail. To learn by going where I have to go.

I decided not to get a tattoo. There are a lot of good reasons for this but 98.7% have to do with my extreme dislike of pain. Instead, I found a wonderful jewellery artist (Etsy shop: WatchWords) who would custom-design this beautiful copper bracelet. It’s on my arm instead of my ankle, and I can look at it while I’m walking, or while I’m at the computer, or while I’m just trying to figure things out, and remind myself: I don’t have the answers. And I don’t have to. Just take the next step (by faith, not by sight). It is solved by walking.

This somehow makes turning 50 a bit less scary.

August 17, 2015

ECT #9-13: Stiles Cove Path (in pieces)

I broke up the stunning Stiles Cove Path (Flatrock to Pouch Cove) into several section hikes to accommodate lack of time and transportation. It would be lovely to hike the whole 15k in a single stretch, but the only section I was able to hike one way was a stretch of about 7k from Stiles Cove to Shoe Cove, where I was able to arrange for my son to pick me up and one end and drive me back to my car. The whole trail is filled with staggeringly lovely vistas, and I had the good fortune of hiking most of it after our terrible July weather and ended and we finally began having summer in August.

I also searched for some geocaches along the way, some of which I found and some of which just resulted in scrached-up shins as I stumbled through bushes and brambles (since it had finally gotten warm enough to wear shorts on the trail!). There are just so many breathtakingly beautiful spots along this trail and the quick pictures I snapped with my phone don’t do justice to them, but they do allow me to recapture for a moment the wonder of being there.

Stiles Cove Path: Length of trail — 15K

Due to return section hikes I probably hiked a total of 23-24K on this path over 5 days of hikes

August 14, 2015

Dating Myself

One expression I’ve always found kind of hilarious is “dating myself.” Of course people use it to mean “showing how old I am, ” like when you say that the M*A*S*H finale was the best series finale in TV history (you know it’s true) and then you giggle and say, “Oops, I’m dating myself!” because that aired in 1983 and some of the people you’re talking to may not have been, you know, BORN YET. But I always hear it as “going on a date with myself” and think, “Dating yourself? Well at least you know you’re out with someone who shares your interests ….”

I have had to date myself quite a bit since Jason has been seconded to Halifax for four months to work at the Halifax Shipyard. He’s home on weekends, so that’s good and we can date each other quite a bit then, but during the weekdays I’m on my own with two teenage children who have jobs and lives of their own. Fortunately, I do enjoy going to restaurants by myself for a nice meal (assuming I have a good book) and I don’t object taking in a movie or any other form of entertainment by myself if no-one else who might like it is free to join me (or even if I just want to go alone).

Yesterday I took myself on a lovely date. I drove out to Cupids to see Perchance Theatre’s production of Much Ado About Nothing in their lovely little semi-outdoor theatre built in the style of Shakespeare’s Globe. Despite occasional bursts of rain which the cast, attired in WW2 period costume, did a great job of working around (and ad-libbing about), the production was a joy to watch. It featured a Claudio and Hero (Dylan Brenton and Erin Mackey) who made those rather thankless roles charming and appealing, and a Beatrice and Benedick (Alexis Koetting and John Sheehan) who stole the show exactly as Beatrice and Benedick should always do (nobody will ever beat Catherine Tate and David Tennant in the B&B roles for me, but Sheehan and Koetting did a fantastic job and of course, I saw them live which is always the best way to see Shakespeare).

Yesterday I took myself on a lovely date. I drove out to Cupids to see Perchance Theatre’s production of Much Ado About Nothing in their lovely little semi-outdoor theatre built in the style of Shakespeare’s Globe. Despite occasional bursts of rain which the cast, attired in WW2 period costume, did a great job of working around (and ad-libbing about), the production was a joy to watch. It featured a Claudio and Hero (Dylan Brenton and Erin Mackey) who made those rather thankless roles charming and appealing, and a Beatrice and Benedick (Alexis Koetting and John Sheehan) who stole the show exactly as Beatrice and Benedick should always do (nobody will ever beat Catherine Tate and David Tennant in the B&B roles for me, but Sheehan and Koetting did a fantastic job and of course, I saw them live which is always the best way to see Shakespeare).

The theatre is right next to a hiking trail, and by the time the play was out the rain had stopped so I went for a short hike on  the Burnt Head trail, then drove over to Brigus for the Country Corner Cafe’s special: cod chowder and blueberry crisp (not together. The chowder is your main course and the blueberry crisp is your dessert — did I have to explain that?). Seriously, if you live within driving distance of Brigus and you are not a vegetarian (or allergic to fish) GO THERE NOW and have a bowl of that cod chowder. It may be the best soup ever put into a bowl since humans started making soup. And of course I had a wonderful book along to read while I enjoyed my supper.

the Burnt Head trail, then drove over to Brigus for the Country Corner Cafe’s special: cod chowder and blueberry crisp (not together. The chowder is your main course and the blueberry crisp is your dessert — did I have to explain that?). Seriously, if you live within driving distance of Brigus and you are not a vegetarian (or allergic to fish) GO THERE NOW and have a bowl of that cod chowder. It may be the best soup ever put into a bowl since humans started making soup. And of course I had a wonderful book along to read while I enjoyed my supper.

All in all it was a great date. While I’ll be glad to have Jason home tonight for a weekend together, the fact that I enjoy my own company has made this summer easier to bear. If you haven’t taken yourself on a date lately, I highly recommend asking yourself out. After all, you know what you like!

August 7, 2015

Shelf Esteem: Elf Publishing

I’ve been a self-published author for all of a week now. Here are my current thoughts on the publishing business:

August 2, 2015

Road Trips

Layout 1

So it’s no secret to anyone who reads this blog or follows me on social media that I just released a new novel, and it’s about three friends on a continent-wide road trip. When I think back to the genesis of this book (which has been percolating a long time both in my head and on paper), what happened was these three very different characters all moved into the apartment in my brain where Characters of Future Books come to live, and they intrigued me, and I wanted to put them in a situation where they and their relationships would be tested in interesting ways. So I sent them on a road trip, because to me, almost nothing is more interesting than a road trip.

As a kid, I went on lots of family road trips — my parents both loved to drive — and I don’t remember loving the process that much. I enjoyed the actual places we visited but I used to find sitting in the backseat of the car boring. As an adult, I still don’t really love driving itself, but somehow, if I’m hopping in the car with someone whose company I enjoy and heading out on the highway to someplace I don’t normally go, then it’s “road trip!” and that’s exciting in and of itself.

It doesn’t have to be a big expedition. Earlier this summer, my friends the Strident Women were heading out to our usual getaway, my aunt’s place in Coley’s Point, which is only an hour’s drive from town. Yet when Tina told me she could catch a ride out with me instead of taking her own car, this familiar one-hour drive suddenly became charged with the excitement of a road trip. A week or so later I had to go to Eastport (a three-hour drive) to visit a book club that was discussing my book A Sudden Sun. A long, tedious way to go to visit a book club (though a lovely group of women at the other end!) but when I invited my friend Sherry to come along, it became a road trip and I was excited about it. A family trip with the kids and two of their friends to go river rafting near Grand Falls involved a four-hour road trip each way with a minivan full of teenagers, and for me, getting there really was half the fun.

The excitement I attach to those two words “road trip” is all about adventure and possibility, even if the adventures are tiny ones. It’s about the songs you sing along to on the car stereo and the snacks you pick up at Irving when you stop for gas and a bathroom break. It’s about the unexpected things you see along the way and the conversations you might never have if you weren’t trapped in a vehicle together for hours at a time. Thinking about the road trip my characters are on in What You Want got me thinking about some of the great road trips of my past.

I have this picture of Sherry, at 17, packing stuff in the trunk of my mom’s Buick Skylark, which I was borrowing for the weekend. I treasure this photo and this memory, not just because Sherry is wearing such an incredibly cute hat or because the actual trip turned out so badly (we were going to a youth retreat weekend at camp, and I injured my knee an hour after arriving at camp and was in excruciating pain and had to be driven back to town to the emergency room and never got to go to the retreat and had to wear a cast for the next three weeks). When I look at this picture I remember that this is the very first road trip I took with a friend where I was the driver, and I vividly recall that thrill of packing up the car and hitting the open road.

I have this picture of Sherry, at 17, packing stuff in the trunk of my mom’s Buick Skylark, which I was borrowing for the weekend. I treasure this photo and this memory, not just because Sherry is wearing such an incredibly cute hat or because the actual trip turned out so badly (we were going to a youth retreat weekend at camp, and I injured my knee an hour after arriving at camp and was in excruciating pain and had to be driven back to town to the emergency room and never got to go to the retreat and had to wear a cast for the next three weeks). When I look at this picture I remember that this is the very first road trip I took with a friend where I was the driver, and I vividly recall that thrill of packing up the car and hitting the open road.

Road trips were a standard feature of my college years because I went to school in southwestern Michigan and returned home to Newfoundland every Christmas and summer break. Because it was much much cheaper in those days, I always flew in and out of Toronto and then had to arrange a ride from Toronto to school. This was not that difficult as lots of people from the Toronto area attended Andrews University, but it did mean a lot of road trips in rattle-trap old cars, often full of people I didn’t know that well (though sometimes full of friends; it was really just the luck of the draw how any given trip would play out). At least once but probably twice I remember somebody’s car breaking down in Small Town Nowhere and waiting several hours for a repair job that would allow us to continue.

Here’s a picture of me and my friend Kirsten on a camping trip we and a bunch of other friends took to Algonquin Park in Ontario one summer in the late 80s (possibly 1990). I have great memories of that trip but they’re all of stuff that happened at the campsite, not the process of getting there, so I never really think of that one as a road trip. The reason I include it is because I don’t have any pictures from the TRULY EPIC ROAD TRIP that Kirsten and I went on in June/July 1990, when I moved back from Ontario to Newfoundland and she decided to come along for the ride. That trip in my Dodge Omni actually included a few experiences that much later made their way into What You Want: we had to sleep on the picnic table at a campsite when we couldn’t find a hotel late at night, just as my characters do. And the terrible cheap motel room in Arizona where some crucial revelations are made in the novel, is modelled on a terrible cheap hotel room Kirsten and I stayed in in Vermont (I just added Arizona heat and a cockroach, as well as a bunch of unrequited love and sexual tension which was NOT present with myself and Kirsten).

Later in my 20s, I moved back home again, this time from Alberta, and once again I had a travelling companion — my mom. She flew out to  Alberta to drive home with me, and again I do not have a picture of the two of us together on that trip, although I do have this picture she took of me and my then-car along the way. We had a lot of laughs on that trip and it’s one I will long remember.

Alberta to drive home with me, and again I do not have a picture of the two of us together on that trip, although I do have this picture she took of me and my then-car along the way. We had a lot of laughs on that trip and it’s one I will long remember.

One of the nicest endorsements I’ve gotten so far for What You Want comes from fellow writer Jill Sooley, who said: “Like any good road trip What You Want has its share of untimely breakdowns, wrong turns and a colorful cast of characters. But not every road trip has Megan, Andrew and Jonathan, an unlikely trio with bags packed and overflowing with dysfunction….We know them. We might even be them. What You Want just might be to grab your best friends, load up the car, and go wherever the road takes you.”

If you read What You Want and it inspires you to head out on an adventure of your own … I couldn’t be happier.

July 28, 2015

ECT #6, 7 and 8: Cobbler Path

I hiked the Cobbler Path from Outer Cove to Red Cliff in three sections, since I was solo hiking and didn’t have the option of a car at each end. On the first hike, I started at the Doran’s Lane trailhead and took the relatively short hike out to Torbay Point and back. Though this was the shortest segment of the trail, it was the most challenging for me as I did it on a windy evening and a good bit of this trail is over open ground near the edge of the cliffs. While the East Coast Trail is built in such a way that even the trails that go along clifftops are well in from the edge and perfectly safe, it doesn’t always FEEL that way to a person who suffers from fear of heights, as I do. I had one of the worst bouts of vertigo I’ve ever had while climbing back up that trail, and had to sit for awhile with my back pressed against a rock to feel grounded — even though I was never in the slightest danger!

My second crack at the path took me in at Doran’s Lane again but this time I went south to Cobbler Brook. This took about an hour (and of course another hour coming back) and involved some steep climbing and lovely views. I met a fellow hiker with two very friendly dogs (I never walk Max on the ECT because he doesn’t interact well with other dogs, and as so many of them are off-leash on this trail I would not be able to handle him if they rushed up intending to be friendly. But I always enjoy meeting other hikers with dogs!). Finally, today I tackled the last part, entering from Red Cliff Road. I hiked out to the other side of Cobbler Brook, meeting up with my own progress from last time, then hiked back and looped around the end of the trail at Red Cliff to come back by the gravel road that leads past the old military ruins up there. I also did some geocaching on this leg of the trip and found four of the seven caches I searched for.

Total distance — about 8K, but since I had to double back every time I guess that puts it around 16 K for all three hikes.

July 15, 2015

Go Set a Watchman

If you’ve been debating whether or not to read Harper Lee’s “new” novel (that’s a misnomer) Go Set a Watchman, check out my lengthy review/reflection after breezing through it on its release day. I posted it over at my book review blog, Compulsive Overreader.

If you’ve been debating whether or not to read Harper Lee’s “new” novel (that’s a misnomer) Go Set a Watchman, check out my lengthy review/reflection after breezing through it on its release day. I posted it over at my book review blog, Compulsive Overreader.