Adam Thierer's Blog, page 68

April 9, 2013

What’s Wrong with Intergovernmentalism?

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public.

— Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

As we approach the World Telecommunication/ICT Policy Forum, the debate over whether intergovernmental organizations like the International Telecommunication Union should have a role to play in Internet governance continues. One argument in favor of intergovernmentalism, advanced, for instance, by former ITU Counsellor Richard Hill (now operating his own ITU lobbying organization, delightfully named APIG), goes as follows:

Everybody already agrees that governments are sovereign within their own territories.

Other than a few “separatists,” everyone agrees that national laws apply to use of the Internet within national borders.

It may be advantageous to “harmonize” national laws concerning the Internet.

Harmonization of national laws happens through intergovernmental organizations, such as the ITU.

Therefore, intergovernmental organizations such as the ITU should have a role in Internet governance.

My purpose in this post is to unpack the third premise. Who exactly benefits (and who is harmed) when national governments harmonize their national laws concerning the Internet?

One way to begin to answer this question is to see which governments think they would benefit from a greater intergovernmental role. One rough metric might be International Telecommunication Regulations (Dubai, 2012) signatories. In the map below, signatories are shown in black.

If it’s not clear from the map, there is a strong correlation between authoritarianism and support for the ITRs. Ninety-one percent of those countries ranked as Full Democracies in the Democracy Index opposed the ITRs, while 91 percent of those countries listed as “Authoritarian” supported them.

What national laws do these authoritarian regimes believe need harmonization? I am not privy to any government’s internal deliberations, but as The Economist reports, many of these countries are engaged in “monitoring, filtering, censoring and criminalising free speech online.” It seems to me that the most reasonable hypothesis is that countries like Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, China, United Arab Emirates, Russian Federation, Iraq, and Sudan would benefit from a “national Internet segment” because it would normalize the idea of such monitoring and censorship.

In other words, authoritarian regimes favor intergovernmental “harmonization” of national Internet laws because it would enable them to get away with more authoritarianism. China already basically operates a “national Internet segment;” traffic into and out of China is filtered by the government. It is going to be a problem for the Chinese government when its subjects become wealthier, more empowered, and ultimately able to point to Internet policy outside of China and politely ask why part of the Chinese Internet is missing. If other countries were to adopt national Internet segments, the Chinese government would be able to avoid this uncomfortable conversation.

The “cooperation” that is likely to result from intergovernmental Internet policymaking is not the solving of communications problems, which is already accomplished quite ably through international technical organizations such as the Internet Engineering Task Force, but a kind of collusion. If we all agree to respect each other’s right to control information within our respective borders, say the authoritarian regimes, we can tame the more revolutionary aspects of the Internet and solidify our grip on power.

In practice, therefore, intergovernmentalism seems to enable national policies that are not only deplorable from a broadly liberal perspective, but illegal under international law. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 19 reads:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Intergovernmentalism should be opposed, therefore, not merely by “separatists,” those who believe national governments have no business applying national law to the Internet. It should be opposed by anyone who does not wish to advance the agenda of censorship.

Andy Greenberg on WikiLeaks and cypherpunks

Andy Greenberg, technology writer for Forbes and author of the new book “This Machine Kills Secrets: How WikiLeakers, Cypherpunks, and Hacktivists Aim to Free the World’s Information,” discusses the rise of the cypherpunk movement, how it led to WikiLeaks, and what the future looks like for cryptography.

Greenberg describes cypherpunks as radical techie libertarians who dreamt about using encryption to shift the balance of power from the government to individuals. He shares the rich history of the movement, contrasting one of t the movement’s founders—hardcore libertarian Tim May—with the movement’s hero—Phil Zimmerman, an applied cryptographer and developer of PGP (the first tool that allowed regular people to encrypt), a non-libertarian who was weary of cypherpunks, despite advocating crypto as a tool for combating the power of government.

According to Greenberg, the cypherpunk movement did not fade away, but rather grew into a larger hacker movement, citing the Tor network, bitcoin, and WikiLeaks as example’s of its continuing influence. Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks, belonged to a listserv followed by early cypherpunks, though he was not very active at the time, he says.

Greenberg is excited for the future of information leaks, suggesting that the more decentralized process becomes, the faster cryptography will evolve.

Related Links

This Machine Kills Secrets: How WikiLeakers, Cypherpunks, and Hacktivists Aim to Free the World’s Information , Greenberg

WikiLeaks’ ‘PLUS D’ Aims To Digitize America’s Secret Diplomatic History, Greenberg

A Different Approach To Foiling Hackers? Let Them In, Then Lie To Them., Greenberg

WCITLeaks, Greenberg

April 5, 2013

CFAA and Prosecutorial Indiscretion

With renewed interest in the failings of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and the role of prosecutorial discretion in its application in light of the tragic outcome in the Aaron Swartz case, I went back to what I wrote about the law in 2009.

Back then, the victim of both the poorly-drafted amendments to CFAA that expanded its scope from government to private computer networks and the politically-motivated zeal of federal prosecutors reaching for something—anything—with which to punish otherwise legal but disfavored behavior was trained on Lori Drew, a far less sympathetic defendant.

But the dangers lurking in the CFAA were just as visible in 2009 as they are today. Those who have recently picked up the banner calling for reform of the law might ask themselves where they were back then, and why the ultimately unsuccessful Drew prosecution didn’t raise their hackles at the time.

The law was just as bad in 2009, and just as dangerously twisted by the government. Indeed, the Drew case, as I wrote at the time, gave all the notice anyone needed of what was to come later.

Here’s the section of The Laws of Disruption from 2009 discussing CFAA:

What did Lori Drew do?

The late-forties suburban St. Louis mother was apparently unhappy about the “mean” behavior of Megan Meier, a thirteen-year-old former friend of Drew’s daughter Sarah. The Drews, along with Ashley Grills, the eighteen-year-old employee of Lori Drew’s home business, hatched a plan. They created a fake MySpace profile for a bare-chested sixteen-year-old boy named “Josh,” who would befriend Megan and encourage her to gossip about other girls. Then they would take printouts to Megan’s mother to show her what the girl was up to.

Not only was the idea stupid, it wasn’t even original—Sarah and Megan, back when they were friends, had done the same thing, creating a profile for a boy who didn’t exist as a way to talk to other boys. This time, however, the plan went awry. Megan became deeply infatuated with Josh. She pressed for his phone number. She wanted to meet him in person. The women behind his account looked for a way out.

According to Grills, “We decided to be mean to her so she would leave him alone . . . and we could get rid of the page.” After deliberating on the easiest way to end an ill-conceived hoax that was going very wrong, Grills sent an instant message to Meier: “The world would be a better place without you.”

The consequences were tragic. Meier, who was being treated for depression, took the suggestion all too literally. After an argument with her parents, who had closely monitored the relationship with Josh from the beginning, Meier went to her room and hanged herself.

Media accounts of the teen’s suicide and the subsequent revelation of who was behind “Josh” created a froth of outrage and hand-wringing. Commentators invented and then proclaimed an epidemic of “cyberbullying.”

When it became clear that the mother of one of Meier’s former friends was involved, Drew herself was subjected to death threats and vandalism. A fake MySpace page for her husband was created. On cable news and the blogosphere, Drew was instantly convicted and sentenced to hell. (“Call me vindictive,” a typical blog entry read, “but i hope that someone kills the woman who is responsible.”)

In the midst of the media storm, state attorneys in Missouri announced there would be no prosecution of Drew for the simple reason that no criminal law had been broken. Federal prosecutors weren’t so sure. They found a 1986 law, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, that set stiff penalties for breaking into and damaging computers.

Drew was charged under the novel theory that since the MySpace terms of service agreement prohibits posting false information in one’s profile, the creation of Josh violated Drew’s contract. Hence, she “accessed” MySpace computers without “authorization.” The creation of Josh, in other words, was a kind of hacking. The victim was not Meier (who with her parents’ permission had also violated the TOS, which requires users to be at least fourteen years old). The victim was MySpace.

Although the jury ultimately refused to convict Drew on the felony charge, they did convict her of the lesser crime of unauthorized access. Valentina Kunasz, the jury’s foreperson, made no apologies for the conviction. “It was so very childish; so very pathetic,” she told reporters after the trial. “She could have done quite a few things to stop it, and she chose not to. And I think she got kind of a rise out of doing this to another person and that bothers me, it really irks me.” Drew faces up to three years in prison and $300,000 in fines.

Legal scholars were generally in agreement that the prosecution was deeply flawed and will very likely be set aside or reversed on appeal. (N.B. Later, it was.) First, there were gaping holes in the government’s case. For one thing, it was Grills, and not Drew, who set up the Josh account and therefore agreed to the TOS (Grills, testifying for the prosecution in exchange for immunity, admitted she never read the TOS). Drew herself was only occasionally involved in the hoax.

By a weird twist of irony, one of the few times she communicated with Meier it turned out she was talking to Meier’s mother, who told Josh he ought to be looking for friends his own age. The fateful message was sent by Grills without Drew’s knowledge, and wasn’t even sent through MySpace.

As a matter of public policy, the prosecution is even more disturbing. Even assuming Drew was bound by the TOS, these contracts are notoriously long and intentionally unreadable. Most of us, even lawyers, don’t read them.

Yet following the logic of the Drew prosecution, anyone who misrepresents some of their personal details on an online dating service has committed a federal crime. Anyone who gives a nonworking telephone number when signing up for a Web site has committed a federal crime.

Indeed, after the verdict, one social network researcher was pained to admit, “We’ve been telling our kids to lie about ID information for a long time now.”

The computer fraud law began as a protection against hackers targeting government computers. The law has never before been used in connection with the violation, willful or otherwise, of private terms of service. There’s no reason to believe Congress intended to criminalize cyberbullying in 1986 or any other time.

Supporters of the conviction argue that the real problem here was a hole in the law—the lack of a statute outlawing whatever it was Lori Drew had done. But the decision of lawmakers not to criminalize a behavior is no reason to correct the problem in a way that undermines the very idea of law. People are often cruel to each other. Other children, adults, and even parents can and do humiliate children in the real world. No laws, in all but extreme cases, are being broken.

It’s difficult to see how this case differs in any respect other than the use of a computer and the tragic outcome.

If the conviction stands, it effectively gives every federal prosecutor a blank check to charge anyone they want with criminal behavior, subject only to their discretion of whether and when to use that power.

Some commentators, pleased with the result if not the process, argued that there was no cause for alarm. Prosecutors, they said, will only use this power in extreme cases.

The Drew prosecution suggests precisely the opposite. For elected prosecutors, the real temptation is to exercise discretion not when the law would otherwise let a heinous crime slip through the cracks but when passions are high and the facts (at least the version presented by the media) are the most lurid—when, in other words, an angry mob demands it.

What Is the Value of Bitcoin?

With Bitcoin enjoying a spike in price against government currencies, there is lots of talk about it on the Interwebs, including Jerry’s typically thoughtful post from earlier today. If you’re not familiar with it yet, here’s a good Bitcoin primer, which also counsels reading a lot more before you acquire Bitcoin, as Bitcoin may fail. If you like Bitcoin and want to buy some, don’t go all goofy. Do your homework. As if you need to be told, be careful with your money.

Much of the commentary in the popular press declares a Bitcoin bubble for one reason or another. It might be a bubble, but nobody actually knows. A way of guessing is to compare Bitcoin’s qualities as a currency and payment network to the alternatives. Like any service or good, there are many dimensions to value storage and transfer.

I may not capture them all, and they certainly don’t predict the correct price against the dollar or other currencies. That depends on the ultimate viscosity of Bitcoin. But Bitcoin certainly has value of a different kind: it may discipline fiat currencies and the states that control them.

Intrinsic Value: If you’re just starting to think about money, this is where you’ll find Bitcoin an obvious failure. These evanescent strings of code have no intrinsic value whatsoever! Anyone relying on them as a store of value is a volunteer victim. Smart people stick with U.S. dollars and other major currencies, thin sheets of cloth or plastic with special printing on them…

No major currency has intrinsic value. Indeed, there isn’t much of anything that has intrinsic value. The value of a thing depends on other people’s demand for it. This is as true of Bitcoin as it is of dollars, sandwiches, and sand. So the intrinsic value question, which seems to cut in favor of traditional currencies, is actually a wash.

Transferability: Bitcoin is good with transferability–far better than any physical currency and quite a bit better than most payment systems. Not only is it fast, with transactions “settling” fairly quickly, but it is borderless. The genius of PayPal (after it gave up on being a replacement monetary system itself) was quick transfer to most places that rich people want to send money. Bitcoin allows quick transfer anywhere the Internet goes.

Acceptance: Bitcoin bombs badly in the area of acceptance. Try buying a sandwich with Bitcoin today and you’ll go hungry because few people and businesses accept it. This is a real problem, but it’s nothing intrinsic to Bitcoin. When Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s home run record, people didn’t understand that credit cards were like money. (Watch the video at the link two or three times if you need to. It’s not only a great moment in sports.) Acceptance of different form-factors for value and payments can change.

Cost: How many billions of dollars per year do we pay for storage and transfer of money? Bitcoin is free.

Inflation-Resistance: Assuming the algorithms work as advertised, the quantity of Bitcoin will rise to a pre-established level of about 21 million over the next couple of decades and will never increase after that. This compares favorably to fiat currencies, the quantity of which are amended by their managers, sometimes quite dramatically, to undercut their value. If you want to hold money, holding Bitcoin is a better deal than holding dollars. Which brings us to…

Deflation-Resistance: Without central planners around to carefully debase its value, Bitcoin might go deflationary, with people refusing to spend it while it rises against all other stores of value and goods. Arguably, that’s what’s happening in the current Bitcoin price-spike. People are buying it in anticipation of its future increase in value.

Deflation can theoretically cause an economy to seize up, with everyone refusing to buy in anticipation of their money gaining in value over the short term. There is room for discussion about whether hyper-deflation can actually occur, how long a hyper-deflation can persist, and whether the avoidance of deflation is worth the risk of having centrally managed currency. I have a hard time being concerned that excessive savings could occur. However, whatever the case with those related issues, Bitcoin is probably deflation-prone compared to dollars and other managed currencies.

Surveillance-Resistance: Where you put your money is a reflection of your values. Payment systems and governments today are definitely gawking through that window into our souls.

Bitcoin, on the other hand, allows payments to be made with very little chance of their being tracked. I say “little chance” because there is some chance of tracking payments on the network. Sophisticated efforts to mask payments will be met by sophisticated efforts to track them. Relatively speaking, though, payments through traditional payment systems like checks, credit cards, and online transfer are super-easy to track. Cash is pretty darn hard to track. So Bitcoin stacks up well against our formal payment systems, but equally or perhaps poorly to cash.

Seizure-Resistance: The digital, distributed nature of Bitcoin makes it resistant to official seizure. Are you in a country that exercises capital controls? (What a euphemism, “capital controls.” It’s seizure.) Put your money into Bitcoin and you can email it to yourself. Carve your Bitcoin code into the inner lip of your frisbee before heading out on that Black Sea vacation. Chances are they won’t catch it at the border.

Traditional currencies either exist in physical form or they’re held and transferred by institutions that are more obediant to the state than they are loyal to their customers. (If Cyprus has anything to do with the current price-spike of Bitcoin, it’s as a lesson to others. Cypriots apparently did not move into Bitcoin in significant numbers.)

Because Bitcoin transactions are relatively hard to track, many can be conducted–how to put this?–independent of one’s tax obligations. In relation to the weight of the tax burden, Bitcoin may grow underground economies. Indeed, it flourishes where transactions (in drugs, for example) are outright illegal. Bitcoin probably moves the Laffer curve to the left.

Security: The tough one for Bitcoin is security. Most people don’t know how to store computer code reliably and how to prevent others from accessing it. Individuals have lost Bitcoin because of hard-drive crashes. (This will cause small losses in the total quantity of Bitcoin over time.) Bitcoin exchanges have collapsed because hackers broke in. And there’s a genuine risk that viruses might camp on your computer, waiting for you to open your (otherwise encrypted) wallet file. They’ll send your Bitcoin to heaven-knows-where the moment you do.

When a Bitcoin transaction has happened, it is final. Like a cash expenditure or loss, there is no reversability and nobody to complain to if you don’t have access to the person on the other side of the transaction. The downside of a currency that costs nothing to transfer is the lack of a 1-800 number to call.

So Bitcoin lags traditional currencies along the security dimension. But this is not intrinsic to Bitcoin. Security will get better as people learn and technology advances. (How ’bout a mega-firewall that requires approval of all outbound Internet traffic while the wallet is open?)

There may be Bitcoin-based payment services, banks, and lenders that provide reversibility, security, that pay interest, and all the other goodies associated with dollars today. To the extent they can stay clear of the regulatory morass, they may be less expensive, more innovative, and, in the early going, more risky.

So what’s the right price for Bitcoin? Only a fool can say. (No offense, all of you declaring a Bitcoin bubble.) I think it depends on the ultimate “viscosity” of Bitcoin.

Let’s say Bitcoin’s exclusive use becomes a momentary medium of exchange: Every buyer converts currency to Bitcoin for transfer, and every seller immediately converts it to her local currency. There’s not much need to hold Bitcoin, so there’s not that much demand for Bitcoin. Its equilibrium price ends up pretty low.

On the other hand, say everybody in the world keeps a little Bitcoin on hand for quick, costless transactions once there’s a handy, reliable, and secure Bitcoin payment system downloadable to our phones. If lots of people hold Bitcoin just because, that highly viscous environment suggests a high price for Bitcoin relative to other currencies and things.

Whatever the case, people are now buying Bitcoin because they think others are going to buy it in the future. Whether they’re “speculators” trying to buy in ahead of other speculators, or if they’re buying Bitcoin as a hedge against the varied weaknesses of fiat currencies and state-controlled payment systems, it doesn’t matter.

What does matter, I think, is having this outlet. The availability of Bitcoin is a small, but growing and important security against fiat currencies and state-controlled payments. It is a competitor to state money.

Bitcoin’s existence makes central bankers slightly less free to inflate the money they control, states will have slightly less success with seizing money, and surveillance of traditional payment systems will be decreasingly useful for law enforcement, taxation, and control.

I don’t think Bitcoin delivers us to libertarian “Shangri-la” or anarcho-capitalism, but it’s a technology that fetters government some. It’s a protection for people, their hard-earned wealth, and their privacy. That’s the value of Bitcoin, in my mind, no matter its current price.

Why bitcoin’s valuation doesn’t really matter

Over the past few days, interest in bitcoin has exploded as its valuation has reached stratospheric levels. Most of the media attention has been focused on that valuation and on bitcoin’s viability as money. For example, the Financial Times had the run-up in bitcoin’s price on its front page yesterday, emphasizing its volatility and its commodity-like qualities. It quoted one analyst saying, “It’s gold for computer nerds.” For many folks, this is how they will be introduced to bitcoin, and it’s a shame because it misses what’s really interesting about the crypto-currency.

Over the past few days, interest in bitcoin has exploded as its valuation has reached stratospheric levels. Most of the media attention has been focused on that valuation and on bitcoin’s viability as money. For example, the Financial Times had the run-up in bitcoin’s price on its front page yesterday, emphasizing its volatility and its commodity-like qualities. It quoted one analyst saying, “It’s gold for computer nerds.” For many folks, this is how they will be introduced to bitcoin, and it’s a shame because it misses what’s really interesting about the crypto-currency.

It’s no secret that bitcoin excites libertarians above all others. What’s less understood is that there are two distinct reasons driving this enthusiasm. The first is that bitcoin is not issued by any authority, so there’s no central banker to monkey the money supply. This attracts what we can affectionately call the “gold bugs” or “audit the Fed” types. They are interested in bitcoin as a new, more moral form of money. And bitcoin as money is what’s been getting all the attention given it’s rising valuation.

But there is a second reason libertarians should be excited about bitcoin, and it’s the reason I am an enthusiast: bitcoin as a payments system. As the world’s first completely decentralize digital currency, there is not only no central banker, there is no intermediary of any kind needed for two parties to make a transaction. Today we rely on third parties to transact online, and when government wants to restrict how we can spend money online, it’s these intermediaries they turn to. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard and other traditional payment processors don’t let you transmit money to WikiLeaks, or to UK gambling sites, or to people in Iran, or to buy illegal goods and services on anonymous black markets. Bitcoin disrupts the ability of governments and intermediaries to control your transactions, and because there is no bitcoin company or bitcoin building anywhere, it can’t be shut down.

Tim Lee gets this when he writes that bitcoin is no competition for the dollar as a currency,

Rather, the future demand for Bitcoins will largely come from applications where conventional currencies don’t perform that well. Bitcoins have some unique properties that no other financial instrument has. They combine the irreversibility of cash transactions with the convenience of electronic transactions. And, the lack of middlemen and regulations greatly reduces the barrier to entry. You don’t need to get permission from big banks or financial regulators to create a Bitcoin-based financial service. All of this means it makes sense to think of Bitcoin less as an alternative currency than as a new platform for financial innovation.

One objection to this view comes from Felix Salmon in a very thoughtful and nuanced essay. He recognizes that bitcoin is “in many ways the best and cleanest payments mechanism the world has ever seen,” but he laments that it is “an uncomfortable combination of commodity and currency.” He goes on to ask rhetorically, “If the currency of a country ever fluctuated as much as bitcoins did, it would never be taken seriously as a medium of exchange: how are you meant to do business in a place where an item costing one unit of currency is worth $10 one day and $20 the next?”

The answer is that bitcoin doesn’t need to be a good unit of account or a good store of value to be a good medium of exchange. Indeed, the prices of products and services being sold for bitcoin online today are denominated in dollars and are converted at the market rate for bitcoin when the transaction happens. This is how WordPress, one of the most prominent companies accepting bitcoin, does it. In fact, WordPress never even handles bitcoin. They employ the services of a very interesting company called Bitpay that manages bitcoin payment processing for them.

When you check out at WordPress using bitcoin, Bitpay quotes you the total of your dollar-denominated shopping cart in bitcoin at the current exchange rate, takes your bitcoin payment, and then deposits dollars in WordPress’s account. This allows WordPress to sell to persons in Iran or Haiti or anyone of the dozens of other countries where PayPal, Visa and MasterCard are not available. It also highlights bitcoin’s true disruptive quality as a payments system—one that is unstoppable, largely anonymous, and incredibly cheap to boot.

To answer Salmon more directly: It doesn’t matter what the price of bitcoin is for it to operate as the amazing payments system that it is. It doesn’t matter if it is very volatile. Dollars go in and dollars come out and the fact that some folks are (probably unwisely) treating it as a store of value doesn’t really matter.

That all said, there are some caveats to point out. Bitcoin will work as a seamless payment system so long as you can get in and out of it quick enough to mitigate volatility. That is largely a technical consideration, but it could also depend on the market’s liquidity, which conceivably could be hurt by speculative hoarding. I haven’t given this much thought yet, but given that bitcoin can be denominated down to eight decimal places, I’m not sure it will be a big problem anytime soon.

April 4, 2013

Ithiel de Sola Pool’s “Technologies of Freedom” Turns 30

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the publication of Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age by the late communications theorist Ithiel de Sola Pool. It was, and remains, a remarkable book that is well worth your time whether you read it long ago or are just hearing about it for the first time. It was the book that inspired me when I first read in 1994 to abandon my chosen field of study (trade policy) and do a deep dive into the then uncharted waters of information technology policy.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the publication of Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age by the late communications theorist Ithiel de Sola Pool. It was, and remains, a remarkable book that is well worth your time whether you read it long ago or are just hearing about it for the first time. It was the book that inspired me when I first read in 1994 to abandon my chosen field of study (trade policy) and do a deep dive into the then uncharted waters of information technology policy.

A Technological Nostradamus

Long before most of the world had heard about this thing called “the Internet” or using terms like “cyberspace” or even “electronic superhighway,” Pool was describing this emerging medium, thinking about its ramifications, and articulating the optimal policies that should govern it. In Technologies of Freedom, Pool set forth both a predictive vision of future communications and “electronic publishing” markets as well as a policy vision for how those markets should be governed. “Networked computers will be the printing presses of the twenty-first century,” Pool argued in a remarkably prescient chapter on the future of electronic publishing. “Soon most published information will disseminated electronically,” and “there will be networks on networks on networks,” he predicted. “A panoply of electronic devices puts at everyone’s hands capacities far beyond anything that the printing press could offer.” As if staring into a crystal ball, Pool predicted:

Separate nations will have separate networks, as they do now, but these will interconnect. Within nations, the satellite carriers, microwave carriers, and local carriers may be—and in the United States almost certainly will be—in the hands of separate organizations, but they will interconnect. So even the basic physical network will be a network of networks. And on top of the physical networks will be a pyramid of service networks. Through them will be published or delivered to the public a variety of things: movies, music, money, education, news, meetings, scientific data, manuscripts, petitions, and editorials.

Remember folks, he was writing this in the early 1980s, when VCRs and the Sony Walkman were still considered cutting-edge electronic technologies! His predictions, which must have sounded like science fiction in 1983, are today’s reality. Few scholars or futurists were more accurate in their forecasts about the world of electronic commerce or online communications that was emerging. It’s worth reading the book just to see how much Pool got right about the future because it is absolutely astonishing. [Note: You might also want to check out how he almost perfectly predicted the copyright policy wars of modern times in his posthumous book, Technologies without Boundaries.]

A Passionate Defense of Free Speech & Technological Freedom

But what made Technologies of Freedom truly special is that Pool did not stop with predictive judgments and scenarios about future tech developments. He continued on to offer a passionate defense of technological freedom and freedom of speech in the electronic age. Pool worried that technological convergence would lead to the convergence of regulatory policies unless action was taken to quarantine electronic publishing and digital networks from analog era regulatory policies:

In the coming era, the industries of print and the industries of telecommunications will no longer be kept apart by a fundamental difference in their technologies. The economic and regulatory problems of the electronic media will thus become the problems of the print media too. No longer can electronic communications be viewed as a special circumscribed case of a monopolistic and regulated communications medium which poses no danger to liberty because there still remains a large realm of unlimited freedom of expression in the print media. The issues that concern telecommunications and now becoming issues for all communications as they all become forms of electronic processing and transmission.

“The specific question to be answered,” Pool asserted, “is whether the electronic resources for communications can be as free of public regulation in the future as the platform and printing press have been in the past.” In his closing chapter on “Policies for Freedom,” Pool discussed possible futures for the emerging world of electronic communications and argued that:

Technology will not be to blame if Americans fail to encompass this system within the political tradition of free speech. On the contrary, electronic technology is conducive to freedom. The degree of diversity and plenitude of access that mature electronic technology allows far exceed what is enjoyed today. Computerized information networks of the twenty-first century need not be any less free for all to use without hindrance than was the printing press. Only political errors might make them so.

Guidelines for Freedom

To guard against those “political errors,” Pool set forth ten “Guidelines for Freedom”:

The First Amendment applies fully to all media.

Anyone may publish at will.

Enforcement must be after the fact, not by prior restraint.

Regulation is a last recourse. In a free society, the burden of proof is for the least possible regulation of communication.

Interconnection among common carriers may be required.

Recipients of privilege (monopolies) may be subject to disclosure.

Privileges (copyrights and patents) may have time limits.

The government and common carriers should be blind to circuit use. What the facility is used for is not their concern.

Bottlenecks should not be used to extend control.

For electronic publishing, copyright enforcement must be adapted to the technology.

Pool’s vision was quite libertarian for his time, but his embrace of minimal interconnection / common carriage regulation shows this he was open to some forms of regulatory oversight. Nonetheless, the role of law in Pool’s paradigm was tightly constrained to ensure new electronic networks developed free of the regulatory burdens of the past.

Importantly, Pool also identified regulation as the source of many of the “monopoly” problems that drove traditional communications and media policy. “The force that preserves most monopoly privilege is the law,” and “most monopolies exist by grace of the police and the courts,” he noted. Further, “most would vanish in the absence of enforcement.” This reflected his general concern about regulatory capture in tech sectors.

Toward Tech Liberty

So, on the occasion of its 30th anniversary, I strongly encourage you to give Pool’s Technologies of Freedom a second look, or a first look if you haven’t had the pleasure of taking it all in before. I think that, like me, you’ll find his predictive powers breathtaking and his principled policy vision refreshingly bold and enlightening. And I challenge you to find another Internet policy book since Technologies of Freedom that has contained more elegant, inspiring prose. It is a beautifully written polemic. Toward that end, I leave you with the final passage from the book and hope that it inspires you as it has me to keep up the good fight for tech liberty:

The easy access, low cost, and distributed intelligence of modern means of communication are a prime reason for hope. The democratic impulse to regulate evils, as Tocqueville warned, is ironically a reason for worry. Lack of technical grasp by policy makers and their propensity to solve problems of conflict, privacy, intellectual property, and monopoly by accustomed bureaucratic routines are the main reasons for concern. But as long as the First Amendment stands, backed by courts which take it seriously, the loss of liberty is not foreordained. The commitment of American culture to pluralism and individual rights is reason for optimism, as is the pliancy and profusion of electronic technology.

April 2, 2013

Joshua Gans on the economics of information

Joshua Gans, professor of Strategic Management at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and author of the new book Information Wants to be Shared, discusses modern media economics, including how books, movies, music, and news will be supported in the future.

Gans argues that sharing enhances most information’s value. He also explains that the business models of traditional media companies, gatekeepers who have relied on scarcity and control, have collapsed in the face of new technologies. Equally important, he argues that sharing can revive moribund, threatened industries even as he examines platforms that have, almost accidentally, thrived in this new environment.

Related Links

Information Wants to be Shared, Gans

Is There a Market for Ideas?, Gans and Scott Stern

The Product Market and the Market for ‘Ideas’: Commercialization Strategies for Technology Entrepreneurs, Gans and Stern

The Impact of Uncertain Intellectual Property Rights on the Market for Ideas: Evidence from Patent Grant Delays, Gans, Stern, and David H. Hsu

March 31, 2013

On the Pursuit of Happiness… and Privacy

Defining “privacy” is a legal and philosophical nightmare. Few concepts engender more definitional controversies and catfights. As someone who is passionate about his own personal privacy — but also highly skeptical of top-down governmental attempts to regulate and/or protect it — I continue to be captivated by the intellectual wrangling that has taken place over the definition of privacy. Here are some thoughts from a wide variety of scholars that make it clear just how frustrating this endeavor can be:

“Perhaps the most striking thing about the right to privacy is that nobody seems to have any very clear idea what it is.” – Judith Jarvis Thomson, “The Right to Privacy,” in Philosophical Dimensions of Privacy: An Anthology, 272, 272 (Ferdinand David Schoeman ed., 1984).

privacy is “exasperatingly vague and evanescent.” – Arthur Miller, The Assault on Privacy: Computers, Data Banks, and Dossiers, 25 (1971).

“[T]he concept of privacy is infected with pernicious ambiguities.” – Hyman Gross, The Concept of Privacy, 42 N.Y.U. L. REV. 34, 35 (1967).

“Attempts to define the concept of ‘privacy’ have generally not met with any success.” – Colin Bennett, Regulating Privacy: Data Protection and Public Policy In Europe and the United States, 25 (1992).

“When it comes to privacy, there are many inductive rules, but very few universally accepted axioms.” - David Brin, The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us To Choose Between Privacy and Freedom? 77 (1998).

“Privacy is a value so complex, so entangled in competing and contradictory dimensions, so engorged with various and distinct meanings, that I sometimes despair whether it can be usefully addressed at all.” – Robert C. Post, Three Concepts of Privacy, 89 GEO. L.J. 2087, 2087 (2001).

“[privacy] can mean almost anything to anybody.” – Fred H. Cate & Robert Litan, Constitutional Issues in Information Privacy, 9 Mich. Telecomm. & Tech. L. Rev. 35, 37 (2002).

privacy has long been a “conceptual jungle” and a “concept in disarray.” “[T]he attempt to locate the ‘essential’ or ‘core’ characteristics of privacy has led to failure.” – Daniel J. Solove, Understanding Privacy 196, 8 (2008).

“Privacy has really ceased to be helpful as a term to guide policy in the United States.” - Woodrow Hartzog, quoted in Cord Jefferson, Spies Like Us: We’re All Big Brother Now, Gizmodo, Sept. 27, 2012.

“for most consumers and policymakers, privacy is not a rational topic. It’s a visceral subject, one on which logical arguments are largely wasted.” – Larry Downes, A Rational Response to the Privacy “Crisis,” Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 716 (Jan. 7, 2013), at 6.

In my new Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy article, “The Pursuit of Privacy in a World Where Information Control is Failing” I build on these insights to argue that:

precisely because privacy has always been a highly subjective philosophical concept;

and is also a constantly morphing notion that evolves as societal attitudes adjust to new cultural and technological realities;

America may never be able to achieve a coherent fixed definition of the term or determine when it constitutes a formal right outside of some narrow contexts.

That doesn’t mean the privacy isn’t profoundly important to many of us, but privacy is, first and foremost, an exercise of personal determination and personal responsibility. To some extent, we have to make our own privacy in this world. In this sense, we can liken it to our right to pursue happiness. Here’s how I put it in Part I of my Harvard JLPP article:

Even if agreement over the scope of privacy rights proves elusive, however, everyone would likely agree that citizens have the right to pursue privacy. In this sense, we might think about the pursuit of privacy the same way we think about the pursuit of happiness. Recall the memorable line from America’s Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Consider the importance of that qualifying phrase—“and the pursuit of”—before the mention of the normative value of happiness. America’s Founders obviously felt happiness was an important value, but they did not elevate it to a formal positive right alongside life, liberty, physical property, or even freedom of speech.

This framework provides a useful way of thinking about privacy. Even if we cannot agree whether we have a right to privacy, or what the scope of any particular privacy right should be, the right to pursue it should be as uncontroversial as the right to pursue happiness. In fact, pursing privacy is probably an important element of achieving happiness for most citizens. Almost everyone needs some time and space to be free with their own thoughts or to control personal information or secrets that they value. But that does not make it any easier to define the nature of privacy as a formal legal right, or any easier to enforce it, even if a satisfactory conception of privacy could be crafted to suit every context.

The most stable and widely accepted privacy rights in the United States have long been those that are tethered to unambiguous tangible or physical rights, such as rights in body and property, especially the sanctity of the home. Moreover, these rights have been focused on limiting the power of state actors, not private parties. By contrast, privacy claims premised on intangible or psychological harms have found far less support, and those claims have been particularly limited for private actors relative to the government. All this will likely remain the case for online privacy. Importantly, if privacy is enshrined as a positive right even in narrowly drawn contexts, it imposes obligations on the government to secure that right. These obligations create corresponding commitments and costs that must be taken into account since government regulation always entails tradeoffs.

Therefore, even as America struggles to reach political consensus over the scope of privacy rights in the information age, it makes sense to find methods and mechanisms—most of which will lie outside of the law—that can help citizens cope with social and technological changes that affect their privacy. Part III will outline some of the ways citizens can pursue and achieve greater personal privacy.

I fully realize that this way of thinking about privacy leaves many challenging questions at the margin and I also understand how it will be unsatisfactory to those who view privacy as a “dignity right” that trumps all other values and considerations. But, to reiterate, what I am suggesting here is that we will likely never be able to achieve a coherent fixed definition of the term or determine when it constitutes a formal right outside of some narrow contexts (such as for sensitive health or financial information, where the potential harms of collection, sharing, and use are more tangible). The primary reason for this is that privacy primary comes down to assertions about “harms” that are primarily psychological in character. But precisely because such asserted harms (1) lack a tangible/physical/monetary nature and (2) also can come into conflict with other liberty rights (especially the right to freely gather information and speak about it; i.e., First Amendment rights), it makes it more difficult to classify psychological “harms” as harms at all.

I feel the same way about concepts like “safety” and “security.” Who among us doubts these values and goals are important? As the father of two young digital natives, I am living a constant struggle to mentor my kids and ensure they have safe and healthy online interactions. But that doesn’t mean I think anyone in this world — including my own children — has an amorphous “right to safety.” What they do have a right to is not to be harmed by others in their online interactions. Where things become sticky, however, is when some child safety advocates adopt an extremely expansive view of what constitutes “harm” in this context and suggest that hearing a single dirty word or seeing a fleeting dirty image somehow irrevocably “harms” their mental well-being and development, or perhaps just their personal morality. (I have written about this here in dozens of essays through the years such as this one on “The Problem of Proportionality in Debates about Online Privacy and Child Safety” as well in longer papers, such as my recent law review article about, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle.”)

While I appreciate the diverse beliefs and values that drives sensitivities about potentially objectionable online content, it is an entirely different matter when one claims “rights” and actionable “harms” in this context. It means that politics will essentially answer what are fundamentally deeply personal “eye of the beholder” questions. It is better, I believe to educate and empower citizens about safe and sensible online interactions and then let them determine what works best for them. Again, whether we are talking about safety or privacy, this model relies upon a certain amount of personal (and parental) responsibility.

To be sure, real harms exist and, at times, law will need to be brought in to right certain wrongs. For example, in the online safety context I favor strong penalties for anyone attempting predatory behavior or extreme forms of incessant harassment. In the privacy context, we’ll still need laws to deal with identity/data theft and certain uses of highly sensitive health and financial information. Outside of those narrow contexts, however, it is better to let people define their own online experiences free of top-down, one-size-fits-all regulatory enactments that attempt to make those determinations for all of us. To reiterate, we all have the right to pursue the objectives we care about–safety, privacy, or just happiness more generally–according to our own value systems. But we should be careful about elevating such amorphous concepts to the level of “rights” and then expecting the State to enforce one set of values and choices on a diverse citizenry.

The Pursuit of Privacy in a World Where Information Control is Failing

March 29, 2013

How ARIN and U.S. Commerce Department were duped by the ITU

ARIN is the Internet numbers registry for the North American region. It likes to present itself as a paragon of multistakeholder governance and a staunch opponent of the International Telecommunication Union’s encroachments into Internet governance. Surely, if anyone wants to keep the ITU out of Internet addressing and routing policy, it would be ARIN. And conversely, in past years the ITU has sought to carve away some of the authority over IP addressing from ARIN and other RIRs.

But wait, what is this? March 15 the ITU Secretary-General released a preparatory report for the ITU’s World Telecommunications Policy Forum, which will take place in Geneva May 14-16. The report contains 6 Internet-related policy resolutions “to provide a basis for discussion …focusing on key issues on which it would be desirable to reach conclusions.” Draft Opinion #3 pertains to Internet addressing. Among other things, the draft resolves:

“that needs-based address allocation should continue to underpin IP address allocation, irrespective of whether they are IPv6 or IPv4, and in the case of IPv4, irrespective of whether they are legacy or allocated address space;

“that all IPv4 transactions be reported to the relevant RIRs, including transactions of legacy addresses that are not necessarily subject to the policies of the RIRs regarding transfers, as supported by the policies developed by the RIR communities;”

“that policies of inter-RIR transfer across all RIRs should ensure that such transfers are needs based and be common to all RIRs irrespective of the address space concerned.”

These policy positions thrust the ITU and its intergovernmental machinery directly into the realm of IP addressing policy. But that is quite predictable; the ITU has always wanted to do that. What is unusual about these resolutions is that they bear an uncanny resemblance to the policy positions currently advocated by ARIN and the U.S. Department of Commerce.

In other words, far from challenging the authority of the RIRs, as it used to do, the ITU now seems to be supinely issuing policy positions that reflect the interests of the RIRs. And after checking with sources who were at the meetings where these draft opinions were created, I confirmed that it was indeed ARIN staff, other RIRs and U.S. Commerce Department representatives who pushed for these positions. Indeed, some sources complained that the whole discussion was completely dominated by RIRs and the U.S.; hardly anyone else was participating.

This is a rather significant turn of events. If nothing else, it makes you think twice about the claims coming out of Dubai that the Internet’s organic multistakeholder institutions were locked in a to-the-death struggle with the forces of repression and authoritarianism in the ITU.

Why did this happen?

As we have noted in earlier blogs, ARIN’s staff and board cling to needs-based address allocations because it gives them control, and they want to retain policy authority over legacy address block holders – because it gives them control. Yet its authority over legacy holders is questionable, to say the least. Legacy block holders not only have no contract with ARIN, they received their number blocks before ARIN existed. Many of them would like to be able to sell numbers to any buyer, regardless of ARIN approvals or needs assessments. ARIN’s current leadership just can’t bring itself to accept this.

Apparently, ARIN is so desperate to validate its shaky claim of authority over legacy address space that it will go to any lengths to find support for it – including inserting its policy preferences into an ITU resolution.

What the geniuses at Commerce and ARIN do not seem to understand is that by getting ITU to be its sock puppet, they are also legitimizing the notion that the ITU and its collection of governments have a legitimate role to play in making and enforcing IP address policy. And yet there is a nice bargain here: ARIN uses the ITU process to validate its position; ITU validates it process by having it used by ARIN.

It is clear that the ITU no longer cares much what the substantive policy is, it just wants to be recognized as a platform for global internet policy. Indeed, it is ironic that just as the more enlightened sections of the Internet technical community are starting to question or openly reject needs assessment, the ITU is just starting to embrace it. Insert your favorite joke about regulatory dinosaurs here: by the time the ITU starts endorsing the conventional wisdom, it’s probably no longer wisdom.

March 28, 2013

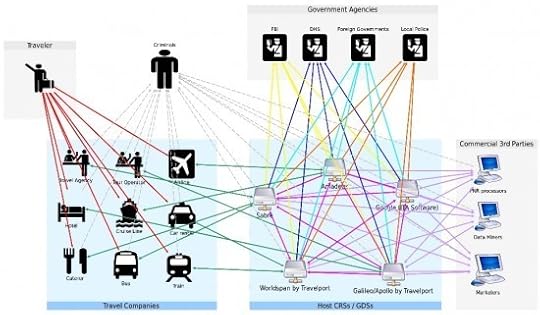

Government Surveillance of Travel IT Systems

If you haven’t seen Edward Hasbrouck’s talk on government surveillance of travel IT systems, you should.

It’s startling to learn just how much access people other than your airline have to your air travel plans.

Here’s just one image that Hasbrouck put together to illustrate what the system looks like.

He’ll be presenting his travel surveillance talk at the Cato Institute at noon on April 2nd. We’ll also be discussing the new public notice on airport strip-search machines issued by the TSA earlier this week.

Register now for Travel Surveillance, Traveler Intrusion.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower