Adam Thierer's Blog, page 72

March 6, 2013

The right and the wrong way to think about cellphone unlocking and DMCA anti-cirumvention

In a recent blog post Scott Cleland endorses the Administration’s stance that the DMCA should be reformed to accommodate, as he puts it, “pro-competitive exceptions that consumers who have fully paid for the phone and fulfilled their legal and contractual obligations, of course should be able to use it with other carriers.” As he deftly explains,

In a nutshell, if one has honored one’s legal obligations to others, one should be free to unlock their phone/property because they indeed own the lock and the key. However if one has not honored one’s full-payment and legal obligations to others, one may have the phone in one’s possession, but one does not legally own the key to unlocking all the commercial value in the mobile device. Most everyone understands legally and morally that there is a huge difference between legally acquiring the key to unlock something of value and breaking into property without permission. The core cleave of this cellphone issue is just that simple.

I couldn’t have put it better myself. There is a key distinction to be drawn between two very different conceptions of “cellphone unlocking.”

One is the principled view, based on respect for property rights and contract law. This view opposes the DMCA’s anti-competitive circumvention provisions, but leaves contract and property rights untouched. It respects contract law because it recognizes that even though you may own your cell phone, you must live up to any contractual obligations you have undertaken. It also respects property rights because it recognizes that once you have satisfied your contractual obligations, there should be no additional legal impediment to your full enjoyment of your device. That’s why we need, as Cleland says, “pro-competitive exemptions” to the DMCA. In this he rightly echoes Tim Lee’s excellent 2006 Cato Institute paper.

The other conception of “cell phone unlocking” is a weird one. It’s that consumers should be able to buy a cheap subsidized phone from a carrier, and then have the right to walk away from their contract to go to another carrier without having to face any penalties. It means limiting the kinds of agreements into which consumers and carriers can enter. This is a view of cellphone unlocking that would eviscerate contract law. Such a rule would be not just wrong on principle, but it would also be bad for consumers who would soon find that they no longer had access to subsidized phones.

It’s an especially weird view of cell phone unlocking because, while it seems to be “in the water” in the current debate, I can’t find anyone who has actually made such a proposal. (If you have any such examples, please drop links to them in the comments!) The White House specifically ruled out such a view of cell phone unlocking in their response to the user petition. The bill just introduced by Sen. Wyden seems to just codify the DMCA exemption that was not renewed in January, so it just puts us back to the state of affairs we had a couple of months ago. And here’s how Politico describes the forthcoming bill from Rep. Chaffetz:

The contours of legislation are still being crafted, but the bill could carve out an exemption to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act rules that would make it OK to unlock a cell phone even if the owner is still under a contract with a carrier. Breaking the contract would likely still carry whatever penalty the carrier contract dictates, but the action, if the bill is indeed drafted that way, would no longer be a criminal offense.

The word “likely” in that quotation gives me pause, but I can’t imagine that Rep. Chaffetz intends to upend contract law. So, I think we can chalk that up to early reporting until we see a bill. The rest of the report makes sense. As long as you honor a contract you’ve entered into—either by maintaining service with your carrier or paying the early termination fee—you should be able to unlock your phone at any time so that you can, for example, take it overseas or maintain service on two carriers for redundant coverage. You would not be making the carrier any worse off by your additional use of your phone. And breach of contract should never be a criminal offense.

No one today is seriously making the retrograde and seriously debunked case for “wireless net neutrality.” As I pointed out yesterday, the present debate is not about telecommunications policy, it’s about copyright. We need to be on guard that it stays that way. To underscore the point, the debate should actually be about more than just cell phones. I’d like to see Rep. Chaffetz, Sen. Wyden, and others expand their bills to tackle anti-circumvention more broadly.

Even though in his post he unfortunately makes some characteristically groundless assertions about people and their motives, Cleland is absolutely right to draw this distinction between a right to use one’s property within the confines of contract law, and a right to ignore contracts with others. As we move forward to reform the DMCA, we must make sure that we don’t replace one bad regulation with a worse one, and that we ensure that contractual obligations are always respected.

A chat with the Wireless Association on cellphone unlocking

I just had a very respectful, reasoned, and, most importantly, informative conversation with Derek Khanna and CTIA on Twitter. It helps clarify a lot about the debate over cellphone unlocking, and I thought I’d share it with you after the jump.

The fact is that carriers today offer a wide range of unlocked devices for sale, so you never have to worry about unlocking or breaking the law. In fact, almost all of the phones Verizon sells are always unlocked. And as far as I can tell, almost all carriers will unlock your phone, once you end your contract, if you just ask. This is all truly great for consumers.

So I don’t understand why carriers should be opposed to an unlocking DMCA exemption. (To be clear, I’m not aware of individual carriers taking positions on the matter, but their trade association did file in the most recent proceeding against the exemption.) It would be better if their customers didn’t have to ask for permission before unlocking a phone that happens to be locked—especially since carriers are willing to give that permission. And if unlocking is no big deal as long as you live up to your contractual obligations, I don’t understand why there should be limits on who can do the unlocking. Here is the exchange:

[View the story "Conversation with CTIA and Derek Khanna on cellphone unlocking" on Storify]

March 5, 2013

The free market case for cell phone unlocking

Conservatives and libertarians believe strongly in property rights and contracts. We also believe that businesses should compete on a level playing field without government tipping the scales for anyone. So, it should be clear that the principled position for conservatives and libertarians is to oppose the DMCA anti-circumvention provisions that arguably prohibit cell phone unlocking.

Indeed it’s no surprise that it is conservatives and libertarians—former RSC staffer Derek Khanna and Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R–Utah)—who are leading the charge to reform the laws.

In it’s response to the petition on cell phone unlocking, the White House got it right when it said: “[I]f you have paid for your mobile device, and aren’t bound by a service agreement or other obligation, you should be able to use it on another network.”

Let’s parse that.

If you have paid for your mobile device, it’s yours, and you should be able to do with it whatever you want. That’s the definition of property rights. If I buy a bowling ball at one bowling alley, I don’t need anyone’s permission to use it in another alley. It’s mine.

Here comes the caveat, though. I don’t need anyone’s permission unless I have entered into an agreement to the contrary. If I got a great discount on my bowling ball in exchange for a promise that for the next two years I’d only use it at Donny’s Bowling Alley, then I am bound to that contract and I can’t very well go off and use it at Walter’s Alley. But once those two years are up, the ball is mine alone and I can do with it whatever I want. Again, that’s the definition of property, and the same should be true for cell phones or any other device.

So how is it that after you have paid for a phone, and you no longer have a contractual obligation with a carrier, that they can still prevent you from using it on another network? The answer is that they are manipulating copyright law to gain an unfair advantage.

For one thing, it’s a bit of a farce. In theory the DMCA’s anti-circumvention provisions exist to protect copyrighted works by making it illegal to circumvent a digital lock that limits access to a creative work. That kind of makes sense when it comes to, say, music that is wrapped in DRM (and indeed the DMCA was targeted at piracy). But what is the creative work that is being protected in cell phones? It’s not clear there is any, but ostensibly it’s the phone’s baseband firmware. It doesn’t pass the laugh test to say that Americans are clamoring to unlock their phones in order to pirate the firmware.

No, Americans don’t want to pirate firmware. They simply want to use their phones as they see fit and carriers and phone makers are misusing the DMCA to make out-of-contract and bought-and-paid-for phones less valuable. That’s bad enough, but what should really upset conservatives and libertarians is that they are employing the power of the state to gain this unfair advantage.

If I use my bowling ball at Walter’s Alley while I’m still under contract to Donny’s, the only remedy available to Donny is to sue me for breach. If he was smart, Donny probably included an “early termination” clause in the contract that spelled out the damages. What Donny can’t do is call the police and have me arrested, nor will he have access to outsized statutory damages. Yet that’s what the DMCA affords device makers and carriers. They are using the power of the state to deny the property rights of others and to secure for themselves rights they could not get through contract law.

Where the White House’s response gets it wrong, however, is in involving the FCC and the NTIA. This is not a telecommunications policy issue; it’s a copyright issue. It’s not just cell phone makers and carriers that are misusing the DMCA. Device makers are employing the same technique to garage door openers, printers, and other devices. Yet that’s how it seems the White House is approaching the issue. From their petition response:

The Obama Administration would support a range of approaches to addressing this issue, including narrow legislative fixes in the telecommunications space that make it clear: neither criminal law nor technological locks should prevent consumers from switching carriers when they are no longer bound by a service agreement or other obligation.

If Congress acts to fix this mess, it should not limit itself to just a narrow provision that exempts cell phone unlocking from the DMCA. In fact, this is an opportunity for conservatives and libertarians in Congress to act on principle and propose a comprehensive fix to the DMCA in the name of respecting property rights. I for one would love to see that challenge put the President.

Finally, it should be made clear that contrary to what some folks are suggesting, by involving the FCC the White House is not endorsing a “Carterfone for wireless”—the idea that carriers should not be allowed to limit how consumers can use their devices, even through contract. The White House response was quite clear that agreements that bind consumers to a particular carrier should still be allowed. And it makes perfect sense.

Today Verizon announced that it activated a record 6.2 million iPhones in its fourth quarter. What accounts for this feat? CFO Fran Shammo explains:

This past fourth quarter, you … had really one thing happen that never happened before, especially with Verizon Wireless, and that was for the first time ever, because of the iPhone 5 launch, we had the 4 at free. So it was the first time ever you could get a free iPhone on the Verizon Wireless network.

A free iPhone is a great deal for consumers who can’t or don’t want to pay for the $450 device up front. The only way carriers can make these offers is in exchange for a promise from the consumer to stay with the carrier for a fixed amount of time and to pay a penalty if they don’t. That’s a win-win-win for the consumer, the carrier and the phone maker—and it’s possible just with the contract law we know and love.

Joe Karaganis on public attitudes toward piracy

Joe Karaganis, vice president at The American Assembly at Columbia University, discusses the relationship between digital convergence and cultural production in the realm of online piracy.

Karaganis’s work at American Assembly arose from a frustration with the one-sided way in which industry research was framing the discourse around global copyright policy. He shares the results of Copy Culture in the US & Germany, a recent survey he helped conduct that distinguishes between attitudes towards piracy in the two countries. It found that nearly half of adults in the U.S. and Germany participate in a broad, informal “copy culture,” characterized by the copying, sharing, and downloading of music, movies, TV shows, and other digital media. And while citizens support laws against piracy, they don’t support outsized penalties.

Karaganis also discuses the new “six-strike” Copyright Alert System in the U.S., of which he is skeptical. He also talks about the politics of copyright reform and notes that there is a window of opportunity for the Republican Party to take up the issue before demography gives the advantage to the much younger Democratic Party.

Related Links

“Copy Culture in the US and Germany”, The American Assembly

Presenting ‘Copy Culture in the US and Germany’, Karagenis

Copy Culture by Race and Ethnicity, Karagenis

Unauthorized File Sharing: Is It Wrong?, Karagenis

March 4, 2013

Forbes commentary on Susan Crawford’s “broadband monopoly” thesis

Over at Forbes we have a lengthy piece discussing “10 Reasons To Be More Optimistic About Broadband Than Susan Crawford Is.” Crawford has become the unofficial spokesman for a budding campaign to reshape broadband. She sees cable companies monopolizing broadband, charging too much, withholding content and keeping speeds low, all in order to suppress disruptive innovation — and argues for imposing 19th century common carriage regulation on the Internet. We begin (we expect to contribute much more to this discussion in the future) to explain both why her premises are erroneous and also why her proscription is faulty. Here’s a taste:

Things in the US today are better than Crawford claims. While Crawford claims that broadband is faster and cheaper in other developed countries, her statistics are convincingly disputed. She neglects to mention the significant subsidies used to build out those networks. Crawford’s model is Europe, but as Europeans acknowledge, “beyond 100 Mbps supply will be very difficult and expensive. Western Europe may be forced into a second fibre build out earlier than expected, or will find themselves within the slow lane in 3-5 years time.” And while “blazing fast” broadband might be important for some users, broadband speeds in the US are plenty fast enough to satisfy most users. Consumers are willing to pay for speed, but, apparently, have little interest in paying for the sort of speed Crawford deems essential. This isn’t surprising. As the LSE study cited above notes, “most new activities made possible by broadband are already possible with basic or fast broadband: higher speeds mainly allow the same things to happen faster or with higher quality, while the extra costs of providing higher speeds to everyone are very significant.”

Even if she’s right, she wildly exaggerates the costs. Using a back-of-the-envelope calculation, Crawford claims that slow downloads (compared to other countries) could cost the U.S. $3 trillion/year in lost productivity from wasted time spent “waiting for a link to load or an app to function on your wireless device.” This intentionally sensationalist claim, however, rests on a purely hypothetical average wait time in the U.S. of 30 seconds (vs. 2 seconds in Japan). Whatever the actual numbers might be, her methodology would still be shaky, not least because time spent waiting for laggy content isn’t necessarily simply wasted. And for most of us, the opportunity cost of waiting for Angry Birds to load on our phones isn’t counted in wages — it’s counted in beers or time on the golf course or other leisure activities. These are important, to be sure, but does anyone seriously believe our GDP would grow 20% if only apps were snappier? Meanwhile, actual econometric studies looking at the productivity effects of faster broadband on businesses have found that higher broadband speeds are not associated with higher productivity.

* * *

So how do we guard against the possibility of consumer harm without making things worse? For us, it’s a mix of promoting both competition and a smarter, subtler role for government.

Despite Crawford’s assertion that the DOJ should have blocked the Comcast-NBCU merger, antitrust and consumer protection laws do operate to constrain corporate conduct, not only through government enforcement but also private rights of action. Antitrust works best in the background, discouraging harmful conduct without anyone ever suing. The same is true for using consumer protection law to punish deception and truly harmful practices (e.g., misleading billing or overstating speeds).

A range of regulatory reforms would also go a long way toward promoting competition. Most importantly, reform local franchising so competitors like Google Fiber can build their own networks. That means giving them “open access” not to existing networks but to the public rights of way under streets. Instead of requiring that franchisees build out to an entire franchise area—which often makes both new entry and service upgrades unprofitable—remove build-out requirements and craft smart subsidies to encourage competition to deliver high-quality universal service, and to deliver superfast broadband to the customers who want it. Rather than controlling prices, offer broadband vouchers to those that can’t afford it. Encourage telcos to build wireline competitors to cable by transitioning their existing telephone networks to all-IP networks, as we’ve urged the FCC to do (here and here). Let wireless reach its potential by opening up spectrum and discouraging municipalities from blocking tower construction. Clear the deadwood of rules that protect incumbents in the video marketplace—a reform with broad bipartisan appeal.

In short, there’s a lot of ground between “do nothing” and “regulate broadband like electricity—or railroads.” Crawford’s arguments simply don’t justify imposing 19th century common carriage regulation on the Internet. But that doesn’t leave us powerless to correct practices that truly harm consumers, should they actually arise.

Read the whole thing here.

Who Really Believes in “Permissionless Innovation”?

Let’s talk about “permissionless innovation.” We all believe in it, right? Or do we? What does it really mean? How far are we willing to take it? What are its consequences? What is its opposite? How should we balance them?

What got me thinking about these questions was a recent essay over at The Umlaut by my Mercatus Center colleague Eli Dourado entitled, “‘Permissionless Innovation’ Offline as Well as On.” He opened by describing the notion of permissionless innovation as follows:

In Internet policy circles, one is frequently lectured about the wonders of “permissionless innovation,” that the Internet is a global platform on which college dropouts can try new, unorthodox methods without the need to secure authorization from anyone, and that this freedom to experiment has resulted in the flourishing of innovative online services that we have observed over the last decade.

Eli goes on to ask, “why it is that permissionless innovation should be restricted to the Internet. Can’t we have this kind of dynamism in the real world as well?”

That’s a great question, but let’s ponder an even more fundamental one: Does anyone really believe in the ideal of “permissionless innovation”? Is there anyone out there who makes a consistent case for permissionless innovation across the technological landscape, or is it the case that a fair degree of selective morality is at work here? That is, people love the idea of “permissionless innovation” until they find reasons to hate it — namely, when it somehow conflicts with certain values they hold dear.

I’ve written about this here before when referencing the selective morality we often see at work in debates over online safety, digital privacy, and cybersecurity. [See my essays: "When It Comes to Information Control, Everybody Has a Pet Issue & Everyone Will Be Disappointed;" "Privacy as an Information Control Regime: The Challenges Ahead," and "And so the IP & Porn Wars Give Way to the Privacy & Cybersecurity Wars."] In those essays, I’ve noted how ironic it is that the same crowd that preaches about how essential permissionless innovation is when it comes to overly-restrictive copyright laws are often among the first to advocate “permissioned” regulations for online data collection and advertising practices. I also noted how many conservatives who demand permissionless innovation on the economic / infrastructure front are quick to call for preemptive content controls to restrict objectionable online content, and a handful of them want “permissioned” cybersecurity rules.

Of course, it’s not really all that surprising that people wouldn’t hold true to the ideal of “permissionless innovation” across the board because at some theoretical point almost every technology has a use scenario that someone — perhaps many of us — would want to see restricted. How do we know when it makes sense to impose some restrictions on innovation to make it more “permissioned”?

The Range of Options

I spend a lot of time thinking about that question these days. The sheer volume and diversity of interesting innovations that surround us today — or that are just on the horizon — are forcing us struggle both individually and collectively with our tolerance for unabated innovation. Here are just a few of the issues I’m thinking of (many of which I am currently writing about) where these questions come up constantly:

Online data aggregation / targeted advertising

Commercial drones

3D printing

Facial recognition & biometrics

Wearable computing

Geolocation / Geotagging / RFID

Robotics

Nanotechnology

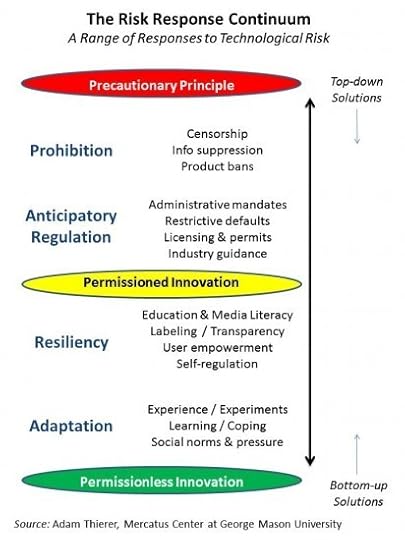

When thinking about innovation in these spaces, it is useful to consider a range of theoretical responses to new technological risks. I developed such a model in my new Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology article on, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle.” In that piece, I identify four general responses and place them along a “risk response continuum”:

Prohibition: Prohibition attempts to eliminate potential risk through suppression of technology, product or service bans, information controls, or outright censorship.

Anticipatory Regulation: Anticipatory regulation controls potential risk through preemptive, precautionary safeguards, including administrative regulation, government ownership or licensing controls, or restrictive defaults. Anticipatory regulation can lead to prohibition, although that tends to be rare, at least in the United States.

Resiliency: Resiliency addresses risk through education, awareness building, transparency and labeling, and empowerment steps and tools.

Adaptation: Adaptation involves learning to live with risk through trial-and-error experimentation, experience, coping mechanisms, and social norms. Adaptation strategies often begin with, or evolve out of, resiliency-based efforts.

While these risk-response strategies could also describe the possible range of responses that individuals or families might employ to cope with technological change, generally speaking, I am here using this framework to consider the theoretical responses by society at large or governments. That allows us to bring three general policy concepts into the discussion:

“Permissionless Innovation“: Complete freedom to experiment and innovate.

“Permissioned Innovation“: General freedom to experiment and innovate, but with possibility that innovation might later be restricted in some fashion.

“The Precautionary Principle“: New innovations are discouraged or even disallowed until their developers can prove that they won’t cause any harms.

Here’s how I put all these concepts together in one image:

This gives us a framework to consider responses to various technological developments we are struggling with today. But how do we decide which response makes the most sense for any given technology? The answer will come down to a complicated (and often quite contentious) cost-benefit analysis that weighs the theoretical harms of technological innovation alongside the many potential benefits of ongoing experimentation.

The Case for Permissionless Innovation or an “Anti-Precautionary Principle”

I believe a strong case can be made that permissionless innovation should be our default position in public policy deliberations about technological change. Here’s how I put it in the conclusion of my “Technopanics” article:

Resiliency and adaption strategies are generally superior to more restrictive approaches because they leave more breathing room for continuous learning and innovation through trial-and-error experimentation. Even when that experimentation may involve risk and the chance of mistake or failure, the result of such experimentation is wisdom and progress. As Friedrich August Hayek concisely wrote, “Humiliating to human pride as it may be, we must recognize that the advance and even preservation of civilization are dependent upon a maximum of opportunity for accidents to happen.”

I believe this is the more sensible default position toward technological innovation because the opposite default — a technological Precautionary Principle — essentially holds the “anything new is guilty until proven innocent,” as journalist Ronald Bailey has noted in critiquing the notion. When the law mandates “play it safe” as the default policy toward technological progress, progress is far less likely to occur at all. Social learning and adaptation become less likely, perhaps even impossible, under such a regime. In practical terms, it means fewer services, lower quality goods, higher prices, diminished economic growth, and a decline in the overall standard of living.

Therefore, the default policy disposition toward innovation should be an “anti-Precautionary Principle.” Paul Ohm outlined that concept in his 2008 article, “The Myth of the Superuser: Fear, Risk, and Harm Online.” Ohm, who recently joined the Federal Trade Commission as a Senior Policy Advisor, began his essay by noting that “Fear of the powerful computer user, the ‘Superuser,’ dominates debates about online conflict,” but that this superuser is generally “a mythical figure” concocted by those who are typically quick to set forth worst-case scenarios about the impact of digital technology on society. Fear of the “superuser” and hypothetical worst-case scenarios prompts policy action, since as Ohm notes: “Policymakers, fearful of his power, too often overreact by passing overbroad, ambiguous laws intended to ensnare the Superuser but which are instead used against inculpable, ordinary users.” “This response is unwarranted,” Ohm argues “because the Superuser is often a marginal figure whose power has been greatly exaggerated.” (at 1327).

Ohm correctly notes that Precautionary Principle policies are often the result. He prefers the “anti-Precautionary Principle” instead, which he summarized as follows: “when a conflict involves ordinary users in the main and Superusers only at the margins, the harms resulting from regulating the few cannot be justified.” (at 1394) In other words, policy should not be shaped by hypothetical fears and worst-case “boogeyman” scenarios. He elaborates as follows:

Even if Congress adopts the Anti-Precautionary Principle and begins to demand better empirical evidence, it may conclude that the Superuser threat outweighs the harm from regulating. I am not arguing that Superusers should never be regulated or pursued. But given the checkered history of the search for Superusers — the overbroad laws that have ensnared non-Superuser innocents; the amount of money, time, and effort that could have been used to find many more non-Superuser criminals; and the spotty record of law enforcement successes — the hunt for the Superuser should be narrowed and restricted. Policymakers seeking to regulate the Superuser can adopt a few strategies to narrowly target Superusers and minimally impact ordinary users. The chief evil of past efforts to regulate the Superuser has been the inexorable broadening of laws to cover metaphor-busting, impossible-to-predict future acts. To avoid the overbreadth trap, legislators should instead extend elements narrowly, focusing on that which separates the Superuser from the rest of us: his power over technology. They should, for example, write tightly constrained new elements that single out the use of power, or even, the use of unusual power. (at 1396-7)

To summarize, the Anti-Precautionary Principle generally holds that:

society is better off when innovation is not preemptively restricted;

accusations of harm and calls for policy responses should not be premised on worst-case scenarios; and,

remedies to actual harms should be narrowly tailored so that beneficial uses of technology are not derailed.

Alternatives to Precaution / Permissioning

I don’t necessarily believe that the “anti-Precautionary Principle” or the norm of “permissionless innovation” should hold in every case. Neither does Ohm. In fact, in his recent work on privacy and online data collection, Ohm betrays his own rule. He does so too casually, I think, and falls prey to the very “Superuser” boogeyman fears he lamented earlier.

For example, in his latest law review article on “Branding Privacy,” Ohm argues that “Change can be deeply unsettling. Human beings prefer predictability and stability, and abrupt change upsets those desires. . . . Rapid change causes harm by disrupting settled expectations” (at 924). His particular concern is the way that corporate privacy policies continue to evolve and generally in the direction of allowing more and more sharing of personal information. Ohm believes that this is a significant enough concern that, at a minimum, companies should be required to assign a new name to any service or product if a material change was made to its information-handling policies and procedures. For example, if Facebook or Google wanted to make a major change to their services in the direction of greater information sharing, they have to change their names (at least for a time) to something like Facebook Public or Google Public.

Before joining the FTC, Ohm also authored a panicky piece for the Harvard Business Review that outlined a worst-case scenario “database of ruin” that will link our every past transgression and most intimate secret. This fear led him to argue that:

We need to slow things down, to give our institutions, individuals, and processes the time they need to find new and better solutions. The only way we will buy this time is if companies learn to say, “no” to some of the privacy-invading innovations they’re pursuing. Executives should require those who work for them to justify new invasions of privacy against a heavy burden, weighing them against not only the financial upside, but also against the potential costs to individuals, society, and the firm’s reputation.

Well geez Paul, that sounds a lot like the same Precautionary Principle that you railed against in your “Superuser” essay! In a sense, I can’t blame Paul for not being true to his “anti-Precautionary Principle.” I would be the first to admit that use scenarios matter, it’s just that I don’t think Paul has proven that the Precautionary Principle should be the norm we adopt in this case, or even that permissioned regulation is necessary. To be fair, Paul has left it a bit unclear just what he wants law to accomplish in this case and when I challenged him on the issue at a recent policy conference at GMU, I could not nail him down on it. But it is not enough just to claim, as Ohm does, that “change can be deeply unsettling” or that “human beings prefer predictability and stability, and abrupt change upsets those desires.” Those are universal truths that can be applied to almost any new type of technological change that society must come to grips with. But it simply cannot serve as the test for preemptively restricting innovation. Something more is needed. Before we get to the point where we “slow things down” for online data collection, or anything else for that matter, we should consider:

How serious is the asserted problem or “harm” in question? (And we need to be very concrete about these harms; conjectural fears and hypothetical harms should not drive regulation.)

What alternatives exist to prohibition or administrative regulation as solutions to those problems?

Regarding this second point, we should ask: how can education and awareness-building help solve problems? How might consumers take advantage of the empowerment tools or strategies at their disposal to deal with technological change? How might we learn to assimilate some of these new technologies into our lives in a gradual fashion to take advantage of the many benefits they offer? Short of administrative regulation, what other legal mechanisms exist (contracts, property rights, torts, anti-fraud statutes, etc), that could be tapped to remedy harms — whether real or perceived? And should we trust the value judgments consumers make and encourage them to exercise personal and parental responsibility before we call in the law to trump everyone’s preferences?

I spend the entire second half of my “Technopanics” paper trying to develop this “bottom-up” approach to dealing with technological change in the hope that we can remain as true as possible to the ideal of “permissionless innovation” whenever possible. When real harms are identified and proven, when can then slide our way up that continuum outlined above as needed, but generally speaking, we should be starting from the default position of innovation allowed.

Applying the Model to Online Safety & Digital Privacy

I’d argue that this “bottom-up” model of coping with technological change is already at work in many areas of modern society. In my “Technopanics” paper, I note that this pretty much the approach we’ve adopted for online safety concerns, at least here in the United States. Very little innovation (or content) is prohibited or even permissioned today. Instead, we rely on other mechanisms: User education and empowerment, informal household media rules, social pressure, societal norms, and so on. [I've documented this in greater detail in this booklet.]

Fifteen years ago, there were many policymakers and policy activists who advocated a very different approach: indecency rules for the Net, mandatory filtering schemes, mandatory age verification, and so on. But that prohibitionary and permission-based approach lost out to the resiliency and adaptation paradigm. As a result, innovation and freedom speech continues relatively unabated. That doesn’t mean everything is sunshine and roses. The Web is full of filth, and hateful things are said every second of the day across digital networks. But we are finding other ways to deal with those problems — not always perfectly, but well enough to get by and allow innovation and speech to continue. When serious harms can be identified — such as persistent online bullying or predation of youth — targeted legal remedies have been utilized.

In two forthcoming law review articles (for the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy and the George Mason Law Review), I apply this same framework to concerns about commercial data collection and digital privacy. I conclude the Harvard essay by noting that:

Many of the thorniest social problems citizens encounter in the information age will be better addressed through efforts that are bottom-up, evolutionary, education-based, empowerment-focused, and resiliency-centered. That framework is the best approach to address personal privacy protection. Evolving social and market norms will also play a role as citizens incorporate new technologies into their lives and business practices. What may seem like a privacy-invasive practice or technology one year might be considered an essential information resource the next. Public policy should embrace—or at least not unnecessarily disrupt—the highly dynamic nature of the modern digital economy.

Two additional factors shape my conclusion that this framework makes as much sense for privacy as it does for online child safety concerns. First, the effectiveness of law and regulation on this front is limited by the normative considerations. The inherent subjectivity of privacy as a personal and societal value is one reason why expanded regulation is not sensible. As with online safety, we have a rather formidable “eye of the beholder” problem at work here. What we need, therefore, are diverse solutions for a diverse citizenry, not one-size-fits-all top-down regulatory solutions that seek to apply to values of the few on the many. Second, enforcement challenges must be taken into consideration. Most of the problems policymakers and average individuals face when it comes to controlling the flow of private information online are similar to the challenges they face when trying to control the free flow of digitalized bits in other information policy contexts, such as online safety, cybersecurity, and digital copyright. It will be increasingly difficult and costly to enforce top-down regulatory regimes (assuming we can even agree to common privacy standards), therefore, alternative approaches to privacy protection should be considered.

Of course, some alleged privacy harms involve highly sensitive forms of personal information and can do serious harm to person or property. Our legal regime has evolved to handle those harms. We have targeted legal remedies for health and financial privacy violations, for example, and state torts to fill other gaps. Meanwhile, the FTC has broad discretion under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act to pursue “unfair and deceptive practices,” including those that implicate privacy. These remedies are more “bottom-up” in character in that they leave sufficient breathing room for ongoing experimentation and innovation but allow individuals to pursue remedies for egregious harms that can be proven.

Applying the Model Elsewhere

We can apply this model more broadly. Let’s pick an issue that’s been in the news recently: concerns about Google Glass and fears about “wearable computing” more generally, which Jerry Brito wrote about earlier today. Google Glass hasn’t even hit the market yet, but the privacy paranoia has already kicked into high gear. Andrew Keen argues that “Google Glass opens an entirely new front in the digital war against privacy” and that “It is the sort of radical transformation that may actually end up completely destroying our individual privacy in the digital 21st century.” His remedy: “I would make data privacy its default feature. Nobody else sees the data I see unless I explicitly say so. Not advertisers, nor the government, and certainly not those engineers of the human soul at the Googleplex. No, Google Glass must be opaque. For my eyes only.”

There’s even more fear and loathing to be found in this piece by Mark Hurst entitled, “The Google Glass feature no one is talking about.” That feature would be Glass’s ability to record massive amounts of video and audio in both public and private spaces. In reality, plenty of people are talking about that feature and wringing the hands about its implications for our collective privacy. Also see, for example, Gary Marshall’s essay, “Google Glass: Say Goodbye to Your Privacy.”

But Google Glass is just the beginning. For another example of a wearable computing technology that is bound to raise concern once it goes mainstream, check out the Memoto Lifelogging Camera. Here’s the description from the website:

The Memoto camera is a tiny camera and GPS that you clip on and wear. It’s an entirely new kind of digital camera with no controls. Instead, it automatically takes photos as you go. The Memoto app then seamlessly and effortlessly organizes them for you. . . . As long as you wear the camera, it is constantly taking pictures. It takes two geotagged photos a minute with recorded orientation so that the app can show them upright no matter how you are wearing the camera. . . . The camera and the app work together to give you pictures of every single moment of your life, complete with information on when you took it and where you were. This means that you can revisit any moment of your past.

Of course, that means you will also be able to revisit many moments from the lives of others who may have been around you while your Memoto Camera was logging your life. So, what are we going to do about Google Glass, Memoto, and wearable computing? Well, for now I hope that our answer is: nothing. This technology is not even out of the cradle yet and we have no idea how it will be put to use by most people. I certainly understand some of the privacy paranoia and worst-case scenarios that some people are circulating these days. As someone who deeply values their own privacy, and as the father of two digital natives who are already begging for more and more digital gadgets, I’ve already thought about a wide variety of worse-case scenarios for me and my kids.

But we’ve been here before. In my Harvard essay, I go back and track privacy panics from the rise of the camera and public photography in the late 1800s all the way down to Gmail in the mid-2000s and note that societal attitudes quickly adjusted to these initially unsettling technologies. That doesn’t mean that all the concerns raised by those technologies disappeared. A century after Warren and Brandeis railed against the camera and called for controls on public photography, many people are still complaining about what people can do with the devices. And although 425 million people now use Gmail and love the free service it provides, some vociferous privacy advocates are still concerned about how it might affect our privacy. And the same is true of a great many other technologies.

But here’s the key question: Are we not better off because we have allowed these technologies to develop in a relatively unfettered fashion? Would we have been better off imposing a Precautionary Principle on cameras and Gmail right out of the gates and then only allowing innovation once some techno-philosopher kings told us that all was safe? I would hope that the costs associated with such restrictions would be obvious. And I would hope that we might exercise similar policy restraint when it comes to new technologies, including Google Glass, Memoto, and other forms of wearable computing. After all, there are a a great many benefits that will come from such technologies and it is likely that many (perhaps most) of us will come to view these tools as an indispensable part of our lives despite the privacy fears of some academics and activists. As Brito notes in his essay on the topic, “in the long run, the public will get the technology it wants, despite the perennial squeamishness of some intellectuals.”

How will we learn to cope? Well, I already have a speech prepared for my kids about the proper use of such technologies that will build on the same sort of “responsible use” talk I have with them about all their other digital gadgets and the online services they love. It won’t be an easy talk because part of it will involve the inevitable chat about responsible use in very personal situations, including times when they may be involved in moments of intimacy with others. But this is the sort of uncomfortable talk we need to be having at the individual level, the family level, and the societal level. How can social norms and smart etiquette help us teach our children and each other responsible use of these new technologies? Such a dialogue is essential since, no matter how much we might hope for these new technologies and the problems they raise might just go away, they won’t.

In those cases where serious harms can be demonstrated — for example “peeping Toms” who use wearable computing to surreptitiously film unsuspecting victims — we can use targeted remedies already on the books to go after them. And I suspect that private contracts might play a stronger role here in the future as a remedy. Many organizations (corporations, restaurants, retail establishments, etc) will want nothing to do with wearable computing on their premises. I can imagine that they may be on the front line of finding creative contractual solutions to curb the use of such technologies.

Embracing Permissionless Innovation While Rejecting “The Borg Complex”

One final point. It is essential that advocates of the “anti-Precautionary Principle” and the ideal of “permissionless innovation” avoid falling prey to what philosopher Michael Sacasas refers to as “the Borg Complex“:

A Borg Complex is exhibited by writers and pundits who explicitly assert or implicitly assume that resistance to technology is futile. The name is derived from the Borg, a cybernetic alien race in the Star Trek universe that announces to their victims some variation of the following: “We will add your biological and technological distinctiveness to our own. Resistance is futile.”

Indeed, too often in digital policy texts and speeches these days, we hear pollyannish writers adopting a cavalier attitude about the impact of technological change on individuals and society. Some extreme technological optimists are highly deterministic about technology as an unstoppable force and its potential to transform man and society for the better. Such rigid technological determinism and wild-eyed varieties of cyber-utopianism should be rejected. For example, as I noted in my review of Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants, “Much of what Kelly sputters in the opening and closing sections of the book sounds like quasi-religious kookiness by a High Lord of the Noosphere” and that “at times, Kelly even seems to be longing for humanity’s assimilation into the machine or The Matrix.”

I discussed this problem in more detail in my chapter on “The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 1,” which appeared in the book, The Next Digital Decade. I noted that technological optimists need to appreciate that, as Neil Postman argued, there are some moral dimensions to technological progress that deserve attention. Not all changes will have positive consequences for society. Those of us who espouse the benefits of permissionless innovation as the default rule must simultaneously be mature enough to understand and address the downsides of digital life without casually dismissing the critics. A “just-get-over-it” attitude toward the challenges sometimes posed by technological change is never wise. In fact, it is downright insulting.

For example, when I am confronted with frustrated fellow parents who are irate about some of the objectionable content their kids sometimes discover online, I never say, “Well, just get over it!” Likewise, when I am debating advocates of increased privacy regulation who are troubled by data aggregation or targeted advertising, I listen to their concerns and try to offer constructive alternatives to their regulatory impulses. I also ask them to think through to consequences of prohibiting innovation and to realize that not everyone shares their same values when it comes to privacy. In other words, I do not dismiss their concerns, no matter how subjective, about the impact of technological change on their lives or the lives of their children. But I do ask them to be careful about imposing their value judgments on everyone else, especially by force of law. I am not harping at them about how “Resistance is futile,” but I am often explaining to them a certain amount of societal and individual adaptation will be necessary and that building coping mechanisms and strategies will be absolutely essential. I also share tips about the tools and strategies they can tap to help protect their privacy and specifically how it is easier (and cheaper) than ever to find and use ad preference managers, private browsing tools, advertising blocking technologies, cookie-blockers, web script blockers, Do Not Track tools, and reputation protection services. This is all part of the resiliency and adaptation paradigm.

Conclusion

In closing, it should be clear by now that I am fairly bullish about humanity’s ability to adapt to technological change; even radical change. Such change can be messy, uncomfortable, and unsettling, but the amazing thing to me is how we humans have again and again and again found ways to assimilate new tools into our lives and marched boldly forward. On occasion, we may need to slow down that process a bit when it can be demonstrated that the harms associated with technological change are unambiguous and extreme in character. But I think a powerful case can be made that, more often than not, we can and do find ways to effectively adapt to most forms of change by employing a variety of coping mechanisms. We should continue to allow progress through trial-and-error experimentation — in other words, through permissionless innovation — so that we can enjoy the many benefits that accrue from this process, including the benefits of learning from the mistakes that we will sometimes along the way.

“Creepiness” is not a bug, it’s *the* feature

Yesterday I explained why I’m not too worried about Silicon Valley’s penchant for “solutionism,” which Evgeny Morozov tackles in his new book. Essentially I think that as long as we make decisions about which technologies to adopt via market processes, people will reject those applications that are stupid or bad. Today I want to explore one reason why I’m optimistic that, in the long run, the public will get the technology it wants, despite the perennial squeamishness of some intellectuals.

The problem some thinkers and pundits have with my sanguine let-a-thousand-flowers-bloom approach is that inevitably the public will embrace some technologies that the thinkers don’t like. The result is usually a lot of fretting and hand-wringing by public intellectuals about what the scary new technology will do to our brains or society. Eventually, activists take on the cause and try to use state power to limit the choices the rest of us can make—for our own good, rest assured.

Today it seems that the next technology to get this treatment will be life-logging and personal data mining, as I discussed in my last post. Squarely in the crosshairs right now is Google Glass.

In this CNN op-ed about Glass Andrew Keen waits only seven words before using the adjective “creepy”—the watchword of nervous nellies everywhere. His concern is that those wearing Google Glass will be spying on anyone in their line of sight. Mark Hurst expresses similar concerns in a widely circulated blog post that also frets about what happens when we’re all not just recording but also being recorded.

This time around, though, I think the worrywarts face an uphill battle. That’s because in the case of life-logging and personal data mining, the “creepy” parts of the technologies are one in the same with the technologies themselves. The “creepiness” is not a bug, it’s the feature, and it can’t be severed without destroying the technology.

The promise of Glass is that one day you’ll be able to quickly get an answer to a questions like, “When was the last time I had coffee with James?” or “What was the name of the woman I met with the last time I visited Sen. Smith’s office?” This doesn’t work, though, unless you can record everyone you see.

When privacy activists turn their attention to Google Glass and other life-logging technologies, I’m not sure how they will argue for a limitation short of an outright ban. And I don’t think the public will stand for that as they will likely appreciate the benefits of these technologies more than they will lament the costs.

“Creepiness,” after all, is not a tangible harm; it’s an emotional appeal. The video below from Memoto—a company making a life-logging camera that I’m hoping to get next month—is also an emotional appeal but in the other direction. Which one do you think will win out?

Memoto snaps two five-megapixel shots every minute and stamps them with your GPS coordinates. The product is something of a proto-Glass and still a bit primitive, but imagine adding facial recognition to it and maybe tying it to all the other data one captures throughout the day as a matter of course, including one’s calendar, email and social networks. I’ll never forget (as I very often do now) who I’ve met and where and what about.

Creepy? No. Useful. Does this make me less human? Not in any meaningful way. In fact one could argue it’s my very human impulse to integrate well into society that I will be serving.

And we are already getting used to these personal data mining technologies, long before we’re all photographing everything we see.

Cue is an app I’ve been using on my iPhone for a little while that mines the gigabytes of data that I already have lying around, including my eight-year archive on Gmail, my Dropbox account (which is essentially my hard drive), my calendar, my social networks, and more. If I have a meeting coming up in my calendar, it knows contextually who the meeting is with and presents me with the emails related to the meeting without any intervention on my part. If I have to call someone but don’t have their number in my contacts, Cue searches my email archive and finds the number because it’s no doubt in there, usually in an email signature. Pretty creepy stuff!

And now comes Tempo, which looks like a much more capable version of Cue. It’s from SRI, the folks who made Siri. Check out this video of Tempo’s CEO talking about what can be deduced from access to your calendar (starting around minute 17):

We can tell from his frank tone that he’s obviously talking to a fellow Valley traveler, not a professional pessimist from the ivory tower or a self-appointed “consumer advocate” from D.C. The thing to note, though, is that if you remove the “creepy” parts of what he’s describing, you destroy the technology altogether, and I don’t think the public will stand for that.

This is all not to say that we won’t have to confront serious ethical and political question as we do with all radical new technologies. Kevin Kelly points out a few obvious ones:

What part of your life is someone else’s privacy?

Is remembering a scene with your brain different from remembering with a camera?

Can the government subpoena your lifelog?

Is total recall fair?

Can I take back a conversation I had with you?

Is it a lie if a single word is different from the record?

How accurate do our biological memories have to be?

Can you lifelog children without their “permission”?

But the fact that we’ll have to wrestle with these questions doesn’t put me off from the technology. I fear that others, though, might want to avoid them altogether and the only way to do that is to avoid the technology itself. But I’m not worried.

“I believe we’ll invent social norms to navigate the times when lifelogging recording is appropriate or not, but for the most part total recording will become as pervasive as text is to us now,” Kelly says. “It will be everywhere and we won’t even notice it – except when it is gone.”

March 3, 2013

People are smarter than they look (or, why I’m not worried about solutionism)

In the New York Times today, Evgeny Morozov indicts the “solutionism” of Silicon Valley, which he defines as the “intellectual pathology that recognizes problems as problems based on just one criterion: whether they are ‘solvable’ with [technology].” This is the theme of his new book, To Save Everything, Click Here, which I’m looking forward to reading.

Morozov is absolutely right that there is a tendency among the geekerati to want to solve things that aren’t really problems, but I think he overestimates the effects this has on society. What are the examples of “solutionism” that he cites? They include:

LivesOn, a yet-to-launch service that promises to tweet from your account after you have died

Superhuman, another yet-to-launch service with no public description

Seesaw, an app that lets you poll friends for advice before making decisions

A notional contact lens product that would “make homeless people disappear from view” as you walk about

It should first be noted that three of these four products don’t yet exist, so they’re straw men. But let’s grant Morozov’s point, that the geeks are really cooking these things up. Does he really think that no one besides him sees how dumb these ideas are?

If LivesOn gets off the ground, how many people does he suppose will sign up to tweet beyond the grave? Or take Seesaw, the one real product on the list. How many people are really going to use the app for anything more than having a bit of fun once in a while? Surely Morozov wouldn’t use such an app to make important decisions, nor would he use it to slavishly make every minor decision of life, so why would he expect that anyone else would?

It seems to me that a more balanced list of “solutionist” technologies might include applications like Google’s Ngram Viewer, a technology that no one really had a clear idea what it would be good for until it was built. The fact that a technology was spawned by a solutionist tendency doesn’t make it bad, and I’m confident society will reject the bad or stupid ones.

What seems to worry Morozov the most, though, are personal data mining technologies that expose our inconsistencies. He quotes Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski:

“The breed of the hesitant and the weak …of those …who believe in telling the truth but rather than tell a distinguished painter that his paintings are daubs will praise him politely,” he wrote, “this breed of the inconsistent is still one of the main hopes for the continued survival of the human race.” If the goal of being confronted with one’s own inconsistency is to make us more consistent, then there is little to celebrate here.

But there’s no reason to think that a technology that confronts one with one’s inconsistencies must also propel one inexorably toward unthinking consistency. To the contrary, such technology might be a way of surfacing choices to be seriously contemplated (something Morozov seems to like).

Take the example posed by Gordon Bell that Morozov quotes (and mocks): “Imagine being confronted with the actual amount of time you spend with your daughter rather than your rosy accounting of it.” At that moment you are presented with a choice. It’s not clear from the mere fact that there is an inconsistency that the obvious course of action is to spend more time with your daughter. It probably does mean that you will want to reflect on your actions and priorities, and you might well conclude that no change is required.

I think Emerson put it better than Kolakowski: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” The operative word is foolish. If we treat the mere discovery of an inconsistency as an answer rather than a question, then yes, that would be problematic. But I don’t see what it is about the mere existence of technologies like personal data mining that would rob people of their autonomy and their reasoning faculties.

Morozov is again right when he says,

Whenever technology companies complain that our broken world must be fixed, our initial impulse should be to ask: how do we know our world is broken in exactly the same way that Silicon Valley claims it is? What if the engineers are wrong and frustration, inconsistency, forgetting, perhaps even partisanship, are the very features that allow us to morph into the complex social actors that we are?

But we do indeed ask ourselves these questions all the time—not only in the pages of the NYT Sunday Review and Dissent, but more importantly in the marketplace. I predict that LivesOn won’t amount to much, that Seesaw will get acquired by some bigger company and then shut down, that Superhuman will be some kind of souped-up to-do list, and (going out on a limb) that we’ll never have homeless-hiding contact lenses. Just because Silicon Valley dreams up these things doesn’t mean that people will want them.

As for automatic life logging and personal data mining, I predict it is here to stay because people will like the benefits. Will it turn us into robots? Not any more than Amazon’s recommendation algorithms make us buy anything. Have we all bought more as a result of such recommendations? Sure, but as a matter of choice that few of us regret. I could be wrong, but I think people will decide that they can do without some kinds of frustration and forgetting, and that they would at least like to be aware of their inconsistencies, and that it’ll be O.K. because they’ll reject the stupid technologies and uses of technologies that diminish their humanity.

March 1, 2013

New free online course on the economics of media

MRUniversity, the “massive open online course” project of Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok, has just launched several new course today, including one on the economics of the media, featuring guests lessons by yours truly and Adam Thierer. From the site:

In the Information Age, media is everywhere. This course will help you make sense of it all, providing insight into the structure of media firms, the nature of their products and how they make money.

Is media biased? Is consolidation of media companies bad for consumers? This course will address those questions as well as how the government effects the structure of media through policies such as net neutrality, copyright, TV regulation and spectrum allocation.

This course will provide a general background on the research from economists on media and journalism. There will be a lot of economics and not too much math.

If you pass the final exam, you will earn our “Economics of the Media” certificate on your profile.

Putting together a couple of 5-minute lessons was a lot harder than it sounded when we were asked to contribute, and it’s given me greater appreciation for what Tyler and Alex are doing with this project. It worth the hard work, though. They are reaching thousands of students for much the same effort that would go into a regular university course.

February 27, 2013

The copyright reform agenda is a natural fit for the G.O.P.

In a recent article in National Review, Joe Karaganis of American Assembly notes that copyright law is increasingly out of step with social norms. His polling suggests that it’s only a matter of time before a majority supports a broad copyright reform agenda.

As I’ve noted before, copyright has for too long been a bipartisan issue, but it will soon become a partisan one. The question is, which party will take up the winning copyright reform issue?

Karaganis:

How would� an� Internet� politics� emerge� in� the Democratic� party? �The �answer� is �probably� simple:� It� is� impossible� in� the� short term� because �of �the �power �of �Hollywood and �inevitable �in �the �long �term �because �of the �power �of �time. �Most� of� the �young �are already �Democrats.

How �would �an� Internet� politics� emerge in� the� Republican� party?� Given� the decades� of� rhetorical� entrenchment around� property �rights �and� law� enforcement,� it� would� probably� require� the recasting� of� intellectual-property� rights as� government� monopoly,� of� SOPA-style� bills� as� crony� capitalism,� and� of Internet� enforcement� as �part� of� a �digital-surveillance �state.

Such� views� in� favor� of� recasting� IP rights �already �have� a �home� on� the� right, and� are �supported �by �congressmen �such as� Darrell� Issa� and� Jason� Chaffetz. Tactical� considerations� alone� could� produce �Republican-led �majorities �on �these issues,� galvanized� by� the� prospect� of wounding� the� Democrats’� Hollywood money� base� or� splitting� Silicon� Valley libertarians.�

Seems to me like the case is strong for a Republican-led movement, but time is of the essence. Will the G.O.P. squander this opportunity?

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower