Adam Thierer's Blog, page 71

March 14, 2013

The FCC at the Crossroads

(A condensed version of this essay appears today in Roll Call.)

(A condensed version of this essay appears today in Roll Call.)

Tuesday was a big day for the FCC. The Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee held an oversight hearing with all five Commissioners, the same day that reply comments were due on the design of eventual “incentive auctions” for over-the-air broadcast spectrum. And the proposed merger of T-Mobile USA and MetroPCS was approved.

All this activity reflects the stark reality that the Commission stands at a crossroads. As once-separate wired and wireless communications networks for voice, video, and data converge on the single IP standard, and as mobile users continue to demonstrate insatiable demand for bandwidth for new apps, the FCC can serve as midwife in the transition to next-generation networks. Or, the agency can put on the blinkers and mechanically apply rules and regulations designed for a by-gone era.

FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski, for one, believes the agency is clearly on the side of the future. In an op-ed last week in the Wall Street Journal, the Chairman took justifiable pride in the focus his agency has demonstrated in advancing America’s broadband advantage, particularly for mobile users.

Mobile broadband has clearly been a bright spot in an otherwise bleak economy. Network providers and their investors, according to the FCC’s most recent analysis, have spent over a trillion dollars since 1996 building next-generation mobile networks, today based on 4G LTE technology.

These investments are essential for high-bandwidth smartphones and tablet devices and the remarkable ecosystem of voice, video, and data app they have enabled. This platform for disruptive innovation has powered a level of “creative destruction” that would do Joseph Schumpeter proud.

Mobile disruptors, however, are entirely dependent on the continued availability of new radio spectrum. In the first five years following the 2007 introduction of the iPhone, mobile data traffic increased 20,000%. No surprise, then, that the FCC’s 2010 National Broadband Plan conservatively estimated that mobile consumers desperately needed an additional 300 MHz. of spectrum by 2015 and 500 MHz. by 2020.

With nearly all usable spectrum long-since allocated, the Plan acknowledged the need for creative new strategies for repurposing existing allocations to maximize the public interest. But some current licensees including over-the-air television broadcasters and the federal government itself are resisting Chairman Genachowski’s efforts to keep the spectrum pipeline open and flowing.

So far, despite bold plans from the FCC for new unlicensed uses of TV “white spaces” and the passage early in 2012 of “incentive auction” legislation from Congress, almost no new spectrum has been made available for mobile consumers. The last significant auction the agency conducted was in 2008, based on capacity freed up in the digital television transition.

The “shared” spectrum the agency has recently been touting would have to be shared with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies, which have so far stonewalled a 2010 Executive Order from President Obama to vacate its unused or underutilized allocations. (The federal government is, by far, the largest holder of usable spectrum today, with as much as 60% of the total.)

And after over a year of on-going design, there is still no timetable for the incentive auctions. Last week, FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel, speaking to the National Association of Broadcasters, urged her colleagues at least to pencil in some dates. But even in the best-case scenario, it will be years before significant new spectrum comes online for mobile devices. The statute gives the agency until 2022.

In the interim, the mobile revolution has been kept alive by creative use of secondary markets, where mobile providers have bought and sold existing licenses to optimize current allocations, and by mergers and acquisitions, which allow network operators to combine spectrum and towers to improve coverage and efficiency. Many transactions have been approved, but others have not. Efforts to reallocate or reassign underutilized satellite spectrum are languishing in regulatory limbo. Local zoning bodies continue to slow or refuse permission for the installation of new equipment. Delays are endemic.

So even as the FCC pursues its visionary long-term plan for spectrum reform, the agency must redouble efforts to encourage optimal use of existing resources. The agency and the Department of Justice must accelerate review of secondary market transactions, and place the immediate needs of mobile users ahead of hypothetical competitive harms that have yet to emerge.

In conducting the incentive auctions, unrelated conditions and pet projects need to be kept out of the mix, and qualified bidders must not be artificially limited to advance vague policy objectives that have previously spoiled some auctions and unnecessarily depressed prices on others.

Let’s hope today’s oversight hearing will hold Chairman Genachowski to his promise to “[keep] discussions focused on solving problems, and on facts and data….so that innovation, private investment and jobs follow.” We badly need all three.

March 12, 2013

So far, cellphone unlocking bills do little to nothing to fix the real problem of anti-circumvention restrictions

Since we last visited the cellphone unlocking question, three bills have been introduced in Congress that address the issue. My sources tell me that forthcoming shortly here on the TLF will be a Ryan Radia patented Radianalysis™ of the bills. While that’s still cooking, though, I wanted to give you my quick impressions.

The bills range from “meh” to crafty.

The first is a bill introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden, which as I said in my last post, “seems to just codify the DMCA exemption that was not renewed in January, so it just puts us back to the state of affairs we had a couple of months ago.” This would be a very narrow fix that would permanently exempt cellphones from the DMCA, but that’s about it. There are also some questions about who is the “owner” of the protected firmware as Ryan will explain in his analysis. Given that what I’d ideally like to see is full repeal of DMCA Section 1201, this bill is just a very modest step in that direction.

The second bill comes from Sen. Amy Klobuchar, which in its entirety reads:

Pursuant to its authorities under title III of the Communications Act of 1934 (47 U.S.C. 301 et seq.), the Federal Communications Commission, not later than 180 days after the date of enactment of this Act, shall direct providers of commercial mobile services and commercial mobile data services to permit the subscribers of such services, or the agent of such subscribers, to unlock any type of wireless device used to access such services. Nothing in this Act alters, or shall be construed to alter, the terms of any valid contract between a provider and a subscriber.

This is a very strange bill. It addresses what is a copyright problem, and a problem created by Section 1201 of the DMCA, by giving new authority to the FCC to force carriers to give up their rights under the DMCA. As I have said before, this is not a telecommunications policy issue, it is a copyright law issue, and that’s how it should be addressed—ideally by repealing the troublesome anti-circumvention prohibitions of which locked cellphones are but one symptom. Also, as written, this bill only applies to carriers, so I wonder if phone makers might still be able to assert rights under the DMCA.

Finally, the third bill is a bill by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy. It is the narrowest possible bill. It is like the Wyden bill in that is rewinds the clock back to the state of affairs before the Librarian of Congress decided to withdraw the DMCA anti-circumvention exemptions for cellphones, but unlike the Wyden bill it is not a permanent exemption in law. It simply changes the rule in the Code of Federal Regulations, something which the Librarian of Congress can undo the next time it reviews DMCA exemptions. As a result, this bill does nothing about one of the most pernicious aspects of DMCA Section 1201, which is that a sole bureaucrat gets to decide what you’re allowed to do with your devices an what you can’t.

Some have suggested that the cellphone unlocking issue is a “trojan horse” actually meant to undermine the entirety of anti-circumvention in the DMCA. If that’s the case, those of us advocating for reform of anti-circumvention have been doing a terrible job of concealing our secert motives. I for one have been pretty clear that all devices should be freed from DMCA anti circumvention restrictions. And the main group agitating for reform is calling itself “Fix the DMCA” and is pretty clear about its goals.

What might well be considered a trojan horse, however, is the Leahy bill, which after all is by the very author of the DMCA itself and co-sponsored by such staunch supporter of SOPA as Sen. Al Franken. Passing it would look like something has been done to address the excesses of the DMCA, but in effect it doesn’t not amend that law at all. Not even one word. Not only would the fundamental problems of the DMCA’s anti-circumvention provisions remain unaddressed, it wouldn’t even permanently address the issue of cellphone unlocking.

There is one promised bill outstanding, and that is from Rep. Jason Chaffetz. Reports say that it will mirror the Wyden bill, but I’m holding out hope that it will be a principled stand for property rights. A stand against regulatory restrictions on the devices I’ve bought and paid for and now own outright.

Marvin Ammori on Internet freedom

Marvin Ammori, a fellow at the New American Foundation and author of the new book On Internet Freedom explains his view of how the First Amendment applies the Internet through the lens of constitutional law and real world case studies.

According to Ammori, Internet freedom is a foundational issue for democracy, equivalent to the right to vote or freedom of speech. In fact, he says, the First Amendment can be used as a design principle for how we think about the challenges we face as Internet technology increasingly becomes a part of our lives.

Ammori’s belief in a positive right to speech—that everyone should have access to the most important speech tools in society and be able to speak with and listen to any other speaker without having to seek permission— translates to a belief that Internet should be made available for everybody, without restrictions aside from those placed on offlinet speech.

Ammori goes on to explain why he thinks SOPA threatened to infringe upon free speech while net neutrality protects it, suggesting that allowing ISPs to control bandwidth usage is tantamount to forcing internet users to become passive consumers of information, rather than creators and content-spreaders.

Related Links

On Internet Freedom , Ammori

Freedom Boxes, Freedom Voices, Ammori

The Next Big Battle in Internet Policy, Ammori

If You’ve Ever Sold a Used iPod, You May Have Violated Copyright Law, Ammori

March 11, 2013

Why we shouldn’t fear commercial drones

Mention the word “drone” to the average American today and the mental image it will conjure is likely to be of a flying robot weapon being wielded by a practically unaccountable executive. That’s why Sen. Rand Paul’s filibuster to draw attention to the administration opaque targeting process was important. I’m afraid, though, that Americans will end up seeing drones only in this negative light. In reality, the thousands of drones that will populate our skies before the end of the decade will be more like this one:

Over at Reason.com today I try to draw the distinction between killbots and TacoCopters, and I make the case we can’t let our legitimate fears of police surveillance and unaccountable assassinations keep us from the benefits of commercial drones.

Requiring that police get a warrant before engaging in surveillance is a no-brainer. But there is a danger that fear of governmental abuse of drones might result in the public demanding—or at least politicians hearing them ask for—precautionary restrictions on personal and commercial uses as well. For example, a bill being considered in New Hampshire would make all aerial photography illegal. And a bill recently introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives would make it a crime to use a private drone to photograph someone “in a manner that is highly offensive to a reasonable person … engaging in a personal or familial activity under circumstances in which the individual had a reasonable expectation of privacy”—a somewhat convoluted standard.

Restrictions on private drones may indeed be necessary some day, as the impending explosion of drone activity will no doubt disrupt our current social patterns. But before deciding on these restrictions, shouldn’t legislators and regulators wait until we have flying around more than a tiny fraction of the thousands of domestic drones the FAA estimates will be active this decade?

If officials don’t wait, they are bound to set the wrong rules since they will have no real data and only their imaginations to go on. It’s quite possible that existing privacy and liability laws will adequately handle most future conflicts. It’s also likely social norms will evolve and adapt to a world replete with robots.

You can read the whole article here.

FCC Spectrum Management: Sometimes 2 + 2 = 4, Sometimes It Doesn’t

In an opinion published in the Wall Street Journal last week, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski admonished us to keep “discussions focused on solving problems, and on facts and data” when evaluating his spectrum policy proposals. That sounds reasonable, and it could be persuasive, if the FCC based its spectrum policy on consistently applied facts and data.

The FCC has instead chosen to selectively manipulate the facts and data to support its desired policy outcomes. Within a single quarter, the FCC has simultaneously concluded that:

194 MHz of spectrum in the 2.5 GHz band is available for mobile broadband services (note: when the FCC wants to show licensed spectrum in the US compares favorably with licensed spectrum on a global basis and that the ratio of licensed to unlicensed spectrum in the US is relatively balanced), and

Only 55 MHz of the same 194 MHz in the 2.5 GHz band is available for mobile broadband services (note: when the FCC wants to deny a merger or limit the amount of spectrum available to disfavored competitors).

Neither the laws of physics and economics nor the regulations governing the 2.5 GHz band changed the actual facts and data in the intervening period between these inconsistent conclusions. The only things that changed were the results the FCC wanted to reach and the “facts and data” the FCC decided to present to the public.

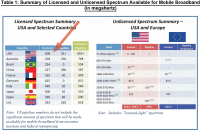

The FCC concluded that 194 MHz of licensed spectrum in the 2.5 GHz band is available for mobile broadband services in a white paper released on February 26, 2013, which compares the availability of licensed mobile and unlicensed spectrum in the United States and other countries. The first table in the white paper summarizes “the results of [FCC] analyses of licensed and unlicensed spectrum in various parts of the world.” This table (excerpted from page 2 of the white paper) clearly indicates that 608 MHz of licensed spectrum is currently available for mobile broadband and 724.5 to 874.5 MHz of spectrum is currently available for unlicensed use in the United States.

The second table in the white paper compares the most commonly deployed mobile broadband spectrum bands in the US and the European Union. This table (excerpted from page 3 of the white paper) clearly indicates that there is currently 194 MHz of licensed mobile spectrum available in the 2.5 GHz band in the US compared to only 190 MHz in the same band in the EU (which is known as the 2.6 GHz band internationally).

Based on the facts and data represented in these two tables, the FCC makes it appear that the amount of licensed spectrum available for mobile broadband in the US is similar to the amount of unlicensed spectrum available in the US and compares favorably with other countries internationally.

When evaluating mergers, however, the FCC analysis of the facts and data is significantly different. On December 18, 2012 – about two months before it issued the white paper – the FCC affirmed its prior conclusion that only 55 MHz of the total 194 MHz of licensed spectrum in the 2.5 GHz band is available for mobile broadband services. This conclusion had previously been used to show that a merger would result in one company having too much licensed spectrum and to limit the amount of spectrum available to disfavored competitors generally.

It appears that the FCC considers the entire 194 MHz of licensed spectrum in the 2.5 GHz band as available for mobile broadband in the US when the ratio of licensed to unlicensed spectrum and international pride are at stake, but only 55 MHz is available when the FCC considers the impact of licensed spectrum aggregation on mobile competition. If the 139 MHz of spectrum the FCC excludes from its calculations when considering mergers is excluded from the international comparison in Table 1 of the report, the total licensed spectrum in the US that is available for mobile broadband drops from 608 to 469 MHz. The FCC presumably wished to avoid this “fact”, because it would indicate that the US has less licensed spectrum available for mobile broadband than every country in the sample except China and the UK, and that the US has nearly twice as much unlicensed spectrum as it has licensed spectrum.

According to the law, economics, and physics, spectrum is either “available” for mobile broadband or it is not. An agency that is truly “focused . . . on facts and data” would not pretend otherwise by manipulating facts and data to satisfy its desired results. Sadly, over the last three years, the FCC has demonstrated it is no such agency.

March 8, 2013

Freedom to innovate and new top level domains

There are hundreds of applications for generic words in ICANN’s new top level domain program. They include .BOOK, .MUSIC, .CLOUD, .ACCOUNTANT, .ARAB and .ART. Some of the applicants for these domains have chosen to make direct use of the name space under the TLD for their own sites rather than offering them for broad general use. Amazon, for example, would probably make .BOOK an extension of its online bookstore rather than part of a large-scale domain name registration business; Google would probably make .CLOUD an extension of its own cloud computing enterprises.

This is really no different from Barnes and Noble registering BOOK.COM and using it only for its bookstore, Scripps registering FOOD.COM and controlling the content of the site, or CNET registering NEWS.COM and making exclusive use of the site for its own news and advertising. Nor is it terribly different from the .MUSEUM top level domain.

Yet these proposals have generated a loud chorus of objections from competing businesses. They have dubbed these applications ‘closed generics’ and shouted so loud that ICANN is once again considering changing its policies in mid-implementation. ICANN staff has called for public comment and asked specifically whether it should change its rules to determine what is a ‘generic term’ and whether ICANN should enlarge even further its role as as a top-down regulator and dictate whether certain business models can be associated with certain domain names.

A group of Noncommercial Stakeholders Group (NCSG) members have weighed in with some badly-needed disinterested public comment. It isn’t about ‘open’ or ‘closed,’ they maintain, it is about the freedom to innovate.

As NCSG stakeholders, our position is driven neither by paying clients nor by an interest in the success of specific applications. It is based on a principled commitment to the ‘permissionless innovation’ that has made the Internet a source of creativity and growth. Our aim is to maximize the options available to DNS users and to minimize top-down controls. We support the freedom of individuals and organizations to register domains and use them legally in any way they see fit. We support experimentation with new ideas about what a TLD can do. We see no reason to impose ex ante restrictions on specific business models or methods of managing the name space under a TLD.

The group warns ICANN of the danger of giving itself the power to decide what qualifies as a ‘generic word’ and rejects any attempt to retroactively create new policies that would dictate business models for TLD applicants. Hopefully ICANN’s board will be able to look past the self-interested cries of businesses that want to eliminate competitors and consider the public interest in Internet freedom. The comments and list of supporters are available at this link.

Rise of the cyber-industrial complex

In our 2011 law review article, Tate Watkins and I warned: “[A] cyber-industrial complex is emerging, much like the military-industrial complex of the Cold War. This complex may serve not only to supply cybersecurity solutions to the federal government, but to drum up demand for those solutions as well.”

In The Hill today, Kevin Bogardus writes under the headline “K St. ready for cybersercurity cash grab”:

The cybersecurity push has drummed up work for influence shops downtown. There have been more than a dozen lobbying registrations for clients that mention “cybersecurity” since Election Day, according to lobbying disclosure records.

Robert Efrus, a long-time Washington hand, is one of many lobbyists working the issue.

“It is a growing niche on K Street,” Efrus said. “I think there are a lot of new players that are seeing action with the executive order and legislation being on worked in Congress, not forgetting the funding opportunities. A lot of tech lobbyists have upped their involvement in cyber for sure.” …

“From a lobbying perspective, with everything else going south, this is one of the few positive developments in the whole federal policy arena,” said Efrus[.] …

Lobbyists note that cybersecurity is one of the few areas where budget-conscious lawmakers are looking to spend.

Cybersecurity is officially government’s growth sector.

It’s time to end compulsory licensing for digital music

Last week, Pandora CEO Tim Westergren was at the Heritage Foundation, “trying to rally the conservative troops,” according to Politico. The company is pushing the Internet Radio Fairness Act, which would let government bureaucrats set the rates for the music it uses one way. Arguing for another (more expensive) way on Wednesday, was RIAA president Cary Sherman who, again according to Politico, was “ranting against the Internet Radio Fairness Act and condemning Pandora for its efforts to change the standard royalty rate.”

Essentially, they are negotiating through Congress; each side wanting to use the government to gore the other’s ox. In a new article at Reason.com, I make the case that the principled free market approach would be to get rid of compulsory licenses and allow the two sides to negotiate with each other. As I point out, this is yet another opportunity for the G.O.P. to take on copyright cronyism:

If a federal policy strips owners of their rights to dispose of their property as they see fit, institutes price-fixing by unelected bureaucrats, and in the process picks an industry’s winners and losers, you’d expect Republicans in Congress to be against it. But when it comes to copyright, all bets are off. …

If Republicans really care about copyright as a property right, they should treat it as property and allow copyright holders to decide to whom they will license their music. That would mean prices negotiated in a free market, not fixed by apparatchiks, and an end to politically determined winners and losers.

How the NSA is helping companies fight Chinese hackers without any information sharing law

Marc Ambinder has some phenomenal reporting in Foreign Policy today about how the NSA assists companies that are the victims of (usually Chinese) cyberespionage. It is a must read.

One thing we learn: “Cyber-warfare directed against American companies is reducing the gross domestic product by as much as $100 billion per year, according to a recent National Intelligence Estimate.”

That is just slightly more than half a percent of GDP, which puts the scope of the threat in perspective.

The most interesting thing, though, is this:

In the coming weeks, the NSA, working with a Department of Homeland Security joint task force and the FBI, will release to select American telecommunication companies a wealth of information about China’s cyber-espionage program, according to a U.S. intelligence official and two government consultants who work on cyber projects. Included: sophisticated tools that China uses, countermeasures developed by the NSA, and unique signature-detection software that previously had been used only to protect government networks.

Press reports have indicated that the Obama administration plans to give certain companies a list of domain names China is known to use for network exploitation. But the coming effort is of an entirely different scope. These are American state secrets.

Very little that China does escapes the notice of the NSA, and virtually every technique it uses has been tracked and reverse-engineered. For years, and in secret, the NSA has also used the cover of some American companies – with their permission – to poke and prod at the hackers, leading them to respond in ways that reveal patterns and allow the United States to figure out, or “attribute,” the precise origin of attacks. The NSA has even designed creative ways to allow subsequent attacks but prevent them from doing any damage. Watching these provoked exploits in real time lets the agency learn how China works.

Will you look at that? Information sharing between the government and the private sector without liability protection. Even more than information sharing, it seems some businesses are allowing the NSA to monitor their systems.

As I’ve said before, there is nothing preventing the government from sharing information about cyberattacks with the private sector. Legislation isn’t required to allow that. As for businesses sharing information with government, they too are free to do so. The only question is whether they should get a free pass for violating contracts or breaking the law when they share in the name of security. I think that would be a mistake.

As Ambiner points out, “the NSA’s reputation has been tarnished by its participation in warrantless surveillance[.]” People don’t trust the NSA with good reason. Security is important, but so are civil liberties. Removing the possibility of liability would also remove any incentive companies might have to be a check on what information the NSA collects. Ambinder writes that given their experience with the warrantless wiretapping program, today “telecoms are wary of cooperating with the NSA beyond the scope of the law.” That’s as it should be. Do we really want to give companies cover to cooperate with the NSA beyond the scope of the law?

According to Ambinder, the NIE suggests “that the NSA will have to perform deep packet inspection on private networks at some point.” (This is the so-called EINSTEIN 3 system This doesn’t sound like a good idea, but if it is to happen, it should be debated in public. Liability protection might allow businesses to allow the NSA to employ the system in secret.

March 7, 2013

FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai Picks the Right Path to the Internet Protocol Transition

In remarks delivered at the Hudson Institute today, Federal Communications Commissioner Ajit Pai outlined two paths for the Internet Protocol (or IP) transition: One that clings to a legacy of heavily-regulated, monopoly communications networks and another that embraces the future being wrought by the competitive nature of IP communications. He noted that, while the FCC has thus far refused to choose one path or the other, consumers have overwhelming chosen the lightly regulated, competitive IP technologies of the future over the preference for monopoly the government chose in the past. Commissioner Pai has chosen to side with consumers by choosing the future – the path that protects consumers while making it clear that 20th Century economic regulation will not be imported into the IP-world.

To start down that path, Commissioner Pai formally proposed that the FCC move forward with a pilot program to test the transition to all-IP networks in a few markets. He noted the groundswell of support for the transition to all-IP networks from Americans across all political and demographic spectra. He also noted that the FCC has often relied on trial runs before embarking on nationwide transitions to new technologies, and specifically mentioned the value of pilot programs involving the DTV transition, the rural healthcare, and educational broadband.

Given the broad consensus in favor of a pilot program to assist in the transition to all-IP networks and the past success of similar efforts, Commissioner Pai indicated that the only significant question the FCC must decide is how to structure the pilot. He proposed four guiding principles:

First, participation in the pilot program should be voluntary.

Second, tests should be conducted in locations that represent diverse geography and demographics.

Third, residential customers with fixed telephone service today should continue to have voice service available to them on IP networks.

Fourth and finally, we must be able to evaluate empirical data from the pilot program in order to figure out what worked and what didn’t.

These are sound principles that I expect the FCC, the industry, and the public will support.

It is critical that the FCC move quickly to implement the pilot program. Commissioner Pai said the FCC would need to seek comment on the rules governing the pilot through a notice of proposed rulemaking, which will take significant time. If the FCC intends to start a pilot program before the end of the year, it would need to issue a notice of proposed rulemaking soon. The clock is ticking, and better networks are waiting.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower