Adam Thierer's Blog, page 64

May 24, 2013

FCC Commissioner Rosenworcel’s Speech on Spectrum Policy Reveals Intellectual Bankruptcy at DOJ

This week at CTIA 2013, FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel presented ten ideas for spectrum policy. Though I don’t agree with all of them, she articulated a reasonable vision for spectrum policy that prioritizes consumer demand, incorporates market-oriented solutions, and establishes transparent goals and timelines. Commissioner Rosenworcel’s principled approach stands in stark contrast to the intellectually bankrupt incentive auction recommendation offered by the Department of Justice last month.

Commissioner Rosenworcel clearly defines three simple goals for a successful incentive auction:

Raising enough revenue to support the nation’s first interoperable, wireless broadband public safety network;

Making more broadband spectrum available through policies that are attractive to broadcasters; and

Providing fair treatment to those broadcasters who do not wish to participate in the auction.

All three goals are consistent with consumer demand for wireless broadband services, the market-oriented reassignment of broadcast spectrum envisioned by the National Broadband Plan, and the will of Congress.

In comparison, the DOJ’s recommendation focuses on only one goal: Subsidizing two particular companies – Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile – to ensure they obtain spectrum in the auction. The DOJ claims these subsidies are necessary to promote competition. But, there is a substantial difference between fair government policies that promote competition generally and a policy of favoring foreign-owned companies over their domestic competitors.

Unfortunately, the DOJ is not alone in its belief that bestowing government benefits on favored companies is a legitimate goal in a free society. Some members of the House Commerce Committee believe the DOJ’s past merger reviews provide “a solid factual and analytical basis” for its current recommendation to the FCC.

The fatal flaw in this theory is that the DOJ’s recommendation to the FCC is inconsistent with the factual findings and analysis of the DOJ in its past merger reviews. As I’ve noted previously, in its complaint against the AT&T/T-Mobile merger, the DOJ found that, “due to the advantages arising from their scope and scale of coverage,” Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile are “especially well-positioned to drive competition” in the wireless industry. That finding doesn’t provide any factual or analytical basis whatsoever to conclude that Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile require special government treatment in the incentive auction in order to compete with Verizon and AT&T.

That’s why the DOJ recommendation relies on an irrational and discriminatory presumption that Verizon and AT&T are using spectrum less efficiently than Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile. A speculative presumption doesn’t require the DOJ to admit its own deceit. It merely requires audacity.

In an era when government officials routinely revise the facts to suit their preferred outcomes and disclaim responsibility for the actions of the agencies they’re charged with leading, Commissioner Rosenworcel’s speech required intellectual bravery and political courage. Her ideas deserve a fair hearing.

May 23, 2013

What Does It Mean to “Have a Conversation” about a New Technology?

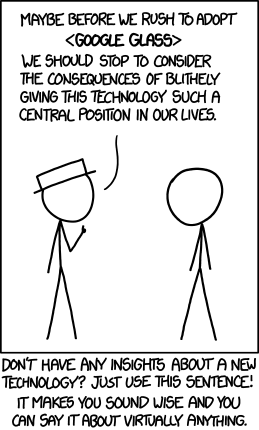

My colleague Eli Dourado brought to my attention this XKCD comic and when tweeting it out yesterday he made the comment that “Half of tech policy is dealing with these people”:

The comic and Eli’s comment may bit a bit snarky, but something about it rang true to me because while conducting research on the impact of new information technologies on society I often come across books, columns, blog posts, editorials, and tweets that can basically be summed up with the line from that comic: “we should stop to consider the consequences of [this new technology] before we …” Or, equally common is the line: “we need to have a conversation about [this new technology] before we…”

But what does that really mean? Certainly “having a conversation” about the impact of a new technology on society is important. But what is the nature of that “conversation”? How is it conducted? How do we know when it is going on or when it is over?

Generally speaking, it is best to avoid guessing as to motive when addressing public policy arguments. It is better to just address the assertions or proposals set forth in someone’s work and not try to determine what motivates it or what other ulterior motives may be driving their reasoning.

Nonetheless, I can’t help but think that sometimes what the “we-need-to-have-a-conversation” crowd is really suggesting is that we need to have a conversation about how to slow or stop the technology in question, not merely talk about its ramifications.

I see this at work all the time in the field of privacy policy. Many policy wonks craft gloom-and-doom scenarios that suggest our privacy is all but dead. I’ve notice a lot more of this lately in essays about the “Internet of Things” and Google Glass in particular. (See these recent essays by Paul Bernal and Bruce Schneier for good examples). Dystopian dread drips from almost every line of these essays.

But, after conjuring up a long parade of horribles and suggesting “we need to have a conversation” about new technologies, authors of such essays almost never finish their thought. There’s no conclusion or clear alternative offered. I suppose that in some cases it is because there aren’t any easy answers. Other times, however, I get the feeling that they have an answer in mind — comprehensive regulation of new technologies in question — but that they don’t want to come out and say it because they think they’ll sound like Luddites. Hell, I don’t know and, again, I don’t want to guess as to motive. I just find it interesting that so much of the writing being done in this arena these days follows that exact model.

But here’s the other point I want to make: I don’t think we’ll ever be able to “have a conversation” about a new technology that yields satisfactory answers because real wisdom is born of experience. This is one of the many important lessons I learned from my intellectual hero Aaron Wildavsky and his pioneering work on risk and safety. In his seminal 1988 book Searching for Safety, Wildavsky warned of the dangers of the “trial without error” mentality — otherwise known as the precautionary principle approach — and he contrasted it with the trial-and-error method of evaluating risk and seeking wise solutions to it. Wildavsky argued that:

The direct implication of trial without error is obvious: If you can do nothing without knowing first how it will turn out, you cannot do anything at all. An indirect implication of trial without error is that if trying new things is made more costly, there will be fewer departures from past practice; this very lack of change may itself be dangerous in forgoing chances to reduce existing hazards … Existing hazards will continue to cause harm if we fail to reduce them by taking advantage of the opportunity to benefit from repeated trials.

This is a lesson too often overlooked not just in the field of health and safety regulation, but also in the world of information policy and this insight is the foundation of a filing I will be submitting to the FTC next week in its new proceeding on the “Privacy and Security Implications of the Internet of Things.” In that filing, I will note that, as was the case with many other new information and communications technologies, the initial impulse may be to curb or control the development of certain Internet of Things technologies to guard against theoretical future misuses or harms that might develop.

Again, when such fears take the form of public policy prescriptions, it is referred to as a “precautionary principle” and it generally holds that, because a given new technology could pose some theoretical danger or risk in the future, public policies should control or limit the development of such innovations until their creators can prove that they won’t cause any harms.

The problem with letting such precautionary thinking guide policy is that it poses a serious threat to technological progress, economic entrepreneurialism, and human prosperity. Under an information policy regime guided at every turn by a precautionary principle, technological innovation would be impossible because of fear of the unknown; hypothetical worst-case scenarios would trump all other considerations. Social learning and economic opportunities become far less likely, perhaps even impossible, under such a regime. In practical terms, it means fewer services, lower quality goods, higher prices, diminished economic growth, and a decline in the overall standard of living.

For these reasons, to the maximum extent possible, the default position toward new forms of technological innovation should be innovation allowed. This policy norm is better captured in the well-known Internet ideal of “permissionless innovation,” or the general freedom to experiment and learn through trial-and-error experimentation.

Stated differently, when it comes to new information technologies such as the Internet of Things, the default policy position should be an “anti-Precautionary Principle.” Paul Ohm, who recently joined the FTC as a Senior Policy Advisor, outlined the concept in his 2008 article, “The Myth of the Superuser: Fear, Risk, and Harm Online.” “Fear of the powerful computer user, the ‘Superuser,’ dominates debates about online conflict,” Ohm argued, but this superuser is generally “a mythical figure” concocted by those who are typically quick to set forth worst-case scenarios about the impact of digital technology on society. Fear of such superusers and the hypothetical worst-case dystopian scenarios they might bring about prompts policy action, since “Policymakers, fearful of his power, too often overreact by passing overbroad, ambiguous laws intended to ensnare the Superuser but which are instead used against inculpable, ordinary users.” “This response is unwarranted,” Ohm says “because the Superuser is often a marginal figure whose power has been greatly exaggerated.”

Ohm gets it exactly right and he could have cited Wildavsky on the matter, who noted that, “’Worst case’ assumptions can convert otherwise quite ordinary conditions… into disasters, provided only that the right juxtaposition of unlikely factors occur.” In other words, creative minds can string together some random anecdotes or stories and concoct horrific-sounding scenarios for the future that leave us searching for preemptive to solutions to problems that haven’t even developed yet.

Unfortunately, fear of “superusers” and worst-case boogeyman scenarios are already driving much of the debate over the Internet of Things. Most of the fear and loathing involves privacy-related dystopian scenarios that envision a miserable panoptic future from which there is no escape. And that’s about the time the authors suggest “we need to have a conversation” about these new technologies — by which they really mean to suggest we need to find ways to put the genie back in the bottle or smash the bottle before the genie even gets out.

But how are we to know what the future holds? And even to the extent some critics believe they possess a techno-crystal ball that can forecast the future, why is it seemingly always the case that none of those possible futures involves humans gradually adapting and assimilating these new technologies into their lives the way they have countless times before? In my FTC filing next week, I will document examples of that process of initial resistance, gradual adaptation, and then eventual assimilation of various new information technologies into society. But I have already developed a model explaining this process and offering plenty of examples in my recent law review article, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” as well as in this lengthy blog post, “Who Really Believes in ‘Permissionless Innovation’?”

In sum, the most important “conversations” we have about new technologies are the ones we have every day as we interact with those new technologies and with each other. Wisdom is born of experience, including experiences involving risk and the possibility of mistakes and accidents. Patience and an openness to permissionless innovation represent the wise disposition toward new technologies not only because it provides breathing space for future entrepreneurialism, but also because it provides an opportunity to observe both the evolution of societal attitudes toward new technologies and how citizens adapt to them.

May 22, 2013

Tech Policy Job Opportunity at AEI

Just FYI… The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is looking for a full-time Program Manager for its new project focused on Internet, communications, and technology policy. The job description can be found online here and is pasted down below:

# # #

The American Enterprise Institute seeks a full-time Program Manager for its new project focused on Internet, communications, and technology policy.

This project will advance policies to encourage innovation, competition, liberty, and growth, creating a positive agenda centered on the political economy of creative destruction. The Program Manager will work closely with the Program Director in the development and day-to-day management of the project; conducting research; developing a new blog website; commissioning monographs and reports; and coordinating events.

Additionally, the Research Program Manager is expected to:

Be a strong writer, capable of drafting and editing funding proposals, research and opinion articles, marketing materials, and correspondence

Provide research and administrative support for the program director on various technology policy initiatives, as required

Be capable of managing numerous projects, initiatives, conferences, and deadlines simultaneously, without oversight

Contribute original writing and research to AEI research programs

Be well-versed in Internet and communications policy and capable of proposing new ideas for conferences, initiatives, and projects

The ideal candidate for this position will combine an outstanding academic record with experience working in a technology and communications policy environment with extensive project-management responsibilities, and excellent writing, research and communications skills. BA in economics, or related degree required. The candidate should have a demonstrated interest in a wide range of policy topics and should have a strong grasp of Washington institutions and current events. Applicants should be flexible, creative, and have proven time-management and writing skills.

If interested, please submit an online application to www.aei.org/jobs, complete with a cover letter, resume, transcripts, and 500-word writing sample.

May 21, 2013

Cato’s “Deepbills” Project Advances Government Transparency

It’s not the culmination–that will come soon–but a major step in work I direct at the Cato Institute to improve government transparency has been achieved. I’ll be announcing and extolling it Wednesday at the House Administration Committee’s Legislative Data and Transparency conference. Here’s a quick survey of what we’ve been doing and the results we see on the near horizon.

After president Obama’s election in 2008, we recognized transparency as a bipartisan and pan-ideological goal at an event entitled: “Just Give Us the Data.” Widespread agreement and cooperation on transparency has held. But by the mid-point of the president’s first term, the deep-running change most people expected was not materializing, and it still has not. So I began working more assiduously on what transparency is and what delivers it.

In “Publication Practices for Transparent Government” (Sept. 2011), I articulated ways the government should deliver information so that it can be absorbed by the public through the intermediary of web sites, apps, information services, and so on. We graded the quality of government data publication in the aptly named November 2012 paper: “Grading the Government’s Data Publication Practices.”

But there’s no sense in sitting around waiting for things to improve. Given the incentives, transparency is something that we will have to force on government. We won’t receive it like a gift.

So with software we acquired and modified for the purpose, we’ve been adding data to the bills in Congress, making it possible to learn automatically more of what they do. The bills published by the Government Printing Office have data about who introduced them and the committees to which they were referred. We are adding data that reflects:

What agencies and bureaus the bills in Congress affect;

What laws the bills in Congress effect: by popular name, U.S. Code section, Statutes at Large citation, and more;

What budget authorities bills include, the amount of this proposed spending, its purpose, and the fiscal year(s).

We are capturing proposed new bureaus and programs, proposed new sections of existing law, and other subtleties in legislation. Our “Deepbills” project is documented at cato.org/resources/data.

This data can tell a more complete story of what is happening in Congress. Given the right Web site, app, or information service, you will be able to tell who proposed to spend your taxpayer dollars and in what amounts. You’ll be able to tell how your member of Congress and senators voted on each one. You might even find out about votes you care about before they happen!

Having introduced ourselves to the community in March, we’re beginning to help disseminate legislative information and data on Wikipedia.

The uses of the data are limited only by the imagination of the people building things with it. The data will make it easier to draw links between campaign contributions and legislative activity, for example. People will be able to automatically monitor ALL the bills that affect laws or agencies they are interested in. The behavior of legislators will be more clear to more people. Knowing what happens in Washington will be less the province of an exclusive club of lobbyists and congressional staff.

In no sense will this work make the government entirely transparent, but by adding data sets to what’s available about government deliberations, management and results, we’re multiplying the stories that the data can tell and beginning to lift the fog that allows Washington, D.C. to work the way it does–or, more accurately, to fail the way it does.

At this point, data curator Molly Bohmer and Cato interns Michelle Newby and Ryan Mosely have marked up 75% of the bills introduced in Congress so far. As we fine-tune our processes, we expect essentially to stay current with Congress, making timely public oversight of government easier.

This is not the culmination of the work. We now require people to build things with the data–the Web sites, apps, and information services that can deliver transparency to your door. I’ll be promoting our work at Wednesday’s conference and in various forums over the coming weeks and months. Watch for government transparency to improve when coders get a hold of the data and build the tools and toys that deliver this information to the public in accessible ways.

Gina Keating on netflix

Gina Keating, author of Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs, discusses the startup of Netflix and their competition with Blockbuster.

Keating begins with the history of the company and their innovative improvements to the movie rental experience. She discusses their use of new technology and marketing strategies in DVD rental, which inspired Blockbuster to adapt to the changing market.

Keating goes on to describe Netflix’s transition to internet streaming and Blockbuster’s attempts to retain their market share.

Related Links

Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs, Keating

Gina Keating’s New Book about the Rise of Netflix, Babayan

‘Netflixed,’ Book by Gina Keating, Describes CEO Reed Hastings As a Nasty Boss’ Liedtke

May 17, 2013

EFF Reverses Course on Bitcoin

Tim Lee is right. The Electronic Frontier Foundation post announcing its decision to accept Bitcoin is strange.

“While we are accepting Bitcoin donations,” the post says, “EFF is not endorsing Bitcoin.” (emphasis in original)

They’ve been using dollars over there without anyone inferring that they endorse dollars. They’ve been using various payment systems with no hint of endorsement. And they use all kinds of protocols without disclaiming endorsement—because they don’t need to.

Someone at EFF really doesn’t like Bitcoin. But, oh, how wealthy EFF would be as an institution if they had held on to the Bitcoin they were originally given. I argued at the time it refused Bitcoin that it was making a mistake, not because of the effect on its bottom line, but because it showed timidity in the face of threats to liberty.

Well, just in time for the Bitcoin 2013 conference in San Jose (CA) this weekend, EFF is getting on board. That’s good news, but it’s not as good as the news would have been if EFF had been a stalwart on Bitcoin the entire time. I have high expectations of EFF because it’s one of the great organizations working in the area of digital liberties.

May 15, 2013

The Best Essay on ‘The Right to be Forgotten’ That You Will Read This Year

The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) has been running some terrific guest essays on its Privacy Perspectives blog lately. (I was honored to be asked to submit an essay to the site a few weeks ago about the ongoing Do Not Track debate.) Today, the IAPP has published one of the most interesting essays on the so-called “right to be forgotten” that I have ever read. (Disclosure: We’ve written a lot here about this issue here in the past and have been highly skeptical regarding both the sensibility and practicality of the notion. See my Forbes column, “Erasing Our Past on the Internet,” for a concise critique.)

In her fascinating and important IAPP guest essay, archivist Cherri-Ann Beckles asks, ”Will the Right To Be Forgotten Lead to a Society That Was Forgotten?” Beckles, who is Assistant Archivist at the University of the West Indies, powerfully explains the importance of archiving history and warns about the pitfalls of trying to censor history through a “right to be forgotten” regulatory scheme. She notes that archives “protect individuals and society as a whole by ensuring there is evidence of accountability in individual and/or collective actions on a long-term basis. The erasure of such data may have a crippling effect on the advancement of a society as it relates to the knowledge required to move forward.”

She concludes by arguing that:

From the preservation of writings on the great pharaohs to the world’s greatest thinkers and inventors as well as the ordinary man and woman, archivists recognise that without the actions and ideas of people, both individually and collectively, life would be meaningless. Society only benefits from the actions and ideas of people when they are recorded, preserved for posterity and made available. Consequently, the “right to be forgotten” if not properly executed, may lead to “the society that was forgotten.”

Importantly, Beckles also stresses the importance of individual responsibility and taking steps to be cautious about the digital footprints they leave online. “More attention should instead be paid to educating individuals to ensure that the record they create on themselves is one they wish to be left behind,” she notes. “Control of data at the point of creation is far more manageable than trying to control data after records capture.”

Anyway, read the whole essay. It is very much worth your time.

DOJ Spectrum Plan Is Not Supported by Economic Theory or FCC Findings

Frontline relied on the DOJ foreclosure theory to predict that the lack of eligibility restrictions in the 700 MHz auction would “inevitably” increase prices, stifle innovation, and reduce the diversity of service offerings as Verizon and AT&T warehoused the spectrum. In reality, the exact opposite occurred.

The DOJ recently recommended that the FCC rig the upcoming incentive auction to ensure Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile are winners and Verizon and AT&T are losers. I previously noted that the DOJ spectrum plan (1) inconsistent with its own findings in recent merger proceedings and the intent of Congress, (2) inherently discriminatory, and (3) irrational as applied. Additional analysis indicates that it isn’t supported by economic theory or FCC factual findings either.

Economic Theory

The Phoenix Center published a paper with an economic simulation that exposes the fundamental economic defect in the foreclosure theory underlying the DOJ recommendation. The DOJ implicitly recognizes that the “private value” of spectrum (the amount a firm is willing to pay) equals its “use value” (derived from using spectrum to meet consumer demand) plus its “foreclosure value” (derived from excluding its use by rivals). In its application of this theory, however, the DOJ erroneously presumes that Verizon and AT&T would derive zero use value from the acquisition of additional spectrum – a presumption that is inconsistent with the FCC findings that prompted the auction.

The Phoenix Center notes that all firms – including Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile – derive a foreclosure value from the acquisition of spectrum due to its scarcity. When considering the benefits to consumers, it is the comparative use value of the spectrum for each provider that is relevant. If the use value of the spectrum to Verizon and AT&T exceeds that of Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile, economic theory says Verizon and AT&T would maximize the potential consumer benefits of that spectrum irrespective of its foreclosure value.

Of course, determining the differing use values of spectrum to particular firms is what spectrum auctions are for, which brings the DOJ’s argument full circle: If government bureaucrats at the DOJ and the FCC could accurately assess the use values of spectrum, we wouldn’t need to hold spectrum auctions in the first place.

The circularity of the DOJ theory explains its reliance on an unsubstantiated presumption that Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile have the highest use value for the spectrum. If the DOJ had instead (1) conducted a thorough factual investigation, (2) analyzed the resulting data to assign bureaucratic use values for the spectrum to each of the four nationwide mobile providers, and (3) compared the results to determine that Verizon and AT&T had lower use values, the DOJ would have engaged in the same failed “comparative hearing” analysis that Congress intended to avoid when it authorized spectrum auctions. Given the Congressional mandate to auction spectrum yielded by the broadcasters, the FCC cannot engage in a comparative process to pick winners and losers, and it certainly cannot substitute an unsubstantiated presumption for an actual comparative process in order to avoid the legal prohibition.

FCC Factual Findings

The foreclosure theory and DOJ presumption are also inconsistent with the auction experience and current factual findings of the FCC. The DOJ foreclosure theory has been presented to the FCC before and has proved invalid by the market.

When the FCC was developing rules for the 700 MHz auction in 2007, Frontline Wireless sought preferential treatment using the same foreclosure theory as the DOJ. Frontline submitted a paper (prepared by Stanford professors of economics and management) that relied on the same types of information and reached the same conclusion as the DOJ – that Verizon and AT&T were dominant “low-frequency” wireless incumbents with “strong incentives” to acquire and warehouse 700 MHz spectrum, and that their participation in the 700 MHz auction must be limited in order to “promote competition” and prevent “foreclosure.” Frontline predicted that, if Verizon and AT&T were not prevented from bidding in the 700 MHz auction, it would “inevitably lead to higher prices, stifled innovation, and reduced diversity of service offerings.”

The FCC rejected Frontline’s foreclosure theory. The FCC concluded that, “given the number of actual wireless providers and potential broadband competitors, it [was] unlikely that [incumbents] would be able to behave in an anticompetitive manner as a result of any potential acquisition of 700 MHz spectrum.”

The last five years have proven that the FCC was correct. Though Verizon and AT&T acquired significant amounts of unfettered 700 MHz spectrum, the auction results have not led to the “higher prices, stifled innovation, and reduced diversity of service offerings” predicted by Frontline. In its most recent mobile competition report, the FCC reported that:

Verizon used its 700 MHz spectrum to deploy a 4G LTE network to more than 250 million Americans less than four years after Verizon’s 700 MHz licenses were approved (i.e., it didn’t warehouse the spectrum).

Mobile wireless prices declined overall in 2010 and 2011, and the price per megabyte of data declined 89% from the 3rd quarter of 2008 – a few months before Verizon received its 700 MHz licenses – to the 4th quarter of 2010 (i.e., industry prices decreased).

The number of subscribers to mobile Internet access services more than doubled from year-end 2009 to year-end 2011 (i.e., industry output increased).

Prepaid services are growing at the fastest rate, and new wholesale and connected device services are growing significantly (i.e., providers continued to provide new and diverse service offerings).

Market concentration has remained essentially unchanged since 2008 (the population weighted average of HHIs increased from 2,842 in 2008 to 2,873 in 2011 – a change of only 1 percent).

Remember: Frontline relied on the DOJ foreclosure theory to predict that the lack of eligibility restrictions in the 700 MHz auction would “inevitably” increase prices, stifle innovation, and reduce the diversity of service offerings as Verizon and AT&T warehoused the spectrum. In reality, the exact opposite occurred. Verizon and AT&T did not warehouse the spectrum, industry prices decreased while output increased, diverse new service offerings exhibited the strongest growth, and market concentration remained essentially unchanged. And, while competition thrived, consumers reaped the benefits.

So, why would the DOJ make the same failed argument for the 600 MHz auction (other than crony capitalism)? Some might say, “Even the boy who cried wolf was right once.” But, even if one were inclined to give the DOJ the benefit of the doubt, the theoretical possibility that the foreclosure theory could adversely impact the 600 MHz auction must be weighed against the potential harm of limiting participation in the auction.

The harm is well documented and could prove particularly problematic in this auction. A paper coauthored by Leslie Marx, who led the design team for the 700 MHz auction when she was the FCC’s Chief Economist, demonstrates that excluding Verizon and AT&T would have even more severe consequences in the incentive auction than in previous auctions.

A paper published by economists at Georgetown University’s Center for Business and Public Policy attempts to quantify the severity of these consequences. It estimates that excluding Verizon and AT&T from the auction could reduce revenues by as much as 40 percent ($12 billion) – a result that would jeopardize funding for the nationwide public safety network, reduce the amount of spectrum made available for wireless Internet services, and adversely affect more than 118,000 U.S. jobs. That is a steep price to pay for the privilege of seeing whether the boy is crying wolf again.

May 14, 2013

Timothy Ravich on drones

Timothy Ravich, a board certified aviation lawyer in private practice and an adjunct professor of law at the Florida International University School of Law and the University of Miami School of Law, discusses the future of unmanned aerial system (UAS), also known as drones.

Ravich defines what UAVs are, what they do, and what their potential non-military uses are. He explains that UAV operations have outpaced the law in that they are not sufficiently supported by a dedicated and enforceable regime of rules, regulations, and standards respecting their integration into the national airspace.

Ravich goes on to explain that Congress has mandated the FAA to integrate UAS into the national airspace by 2015, and explains the challenges the agency faces. Among the novel issues domestic drone use raises are questions about trespass, liability, and privacy.

Related Links

The Integration of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles into the National Airspace, Ravich

Domestic Drones are Coming your Way, Brito

Making airspace available for ‘permissionless innovation,’ Technology Liberation Front

May 13, 2013

Is the FCC Seeking to Help Internet Consumers or Preserve Its Own Jurisdiction?

As the “real-world” continues its inexorable march toward our all-IP future, the FCC remains stuck in the mud fighting the regulatory wars of yesteryear, wielding its traditional weapon of bureaucratic delay to mask its own agenda.

Late last Friday the Technology Transitions Policy Task Force at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued a Public Notice proposing to trial three narrow issues related to the IP transition (the transition of 20th Century telephone systems to the native Internet networks of the 21stCentury). Outgoing FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski says these “real-world trials [would] help accelerate the ongoing technology transitions moving us to modern broadband networks.” Though the proposed trials could prove useful, in the “real-world”, the Public Notice is more likely to discourage future investment in Internet infrastructure than to accelerate it.

First, the proposed trials wouldn’t address the full range of issues raised by the IP transition. As proposed, the trials would address three limited issues: VoIP interconnection, next-generation 911, and wireless substitution. Though these issues are important, the FCC proposals omit the most important issue of all – the transition of the wireline network infrastructure itself. As a result, they would yield little, if any, data about the challenges of shutting down the technologies used by the legacy telephone network.

Second, the proposed trials are unlikely to yield significant new information. As Commissioner Pai noted in his statement last week, all three issues are already being trialed in the “real-world” by the industry, consumers, and state regulators.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, all three issues are already the subject of ongoing FCC proceedings and don’t raise any new issues (e.g., issues that would implicate FCC regulatory forbearance).

If the FCC truly wanted to accelerate the transition to all-IP infrastructure, why would it propose studies of three limited issues that it is already addressing? I expect the FCC was unwilling to propose a comprehensive trial that could jeopardize its assertion of regulatory jurisdiction over the Internet, especially its potential authority to impose Title II regulations if it loses the net neutrality case pending in the DC Circuit. The language in the Public Notice indicates it is no coincidence that the narrow issues the FCC intends to study do not implicate its forbearance authority or (at least directly) the scope of its jurisdiction. For example, the Public Notice states that VoIP interconnection involves, among other things, “pricing” and “quality of service” issues, and that the FCC wants to structure any trial to provide it with “data to evaluate which policies may be appropriate” for VoIP interconnection. This language clearly indicates that the FCC is contemplating Title II pricing regulation of VoIP interconnection.

The Public Notice also seeks additional comment on the more comprehensive approach to the IP transition originally proposed by Commissioner Ajit Pai in July 2012, but in a way that sends all the wrong signals to investors.

When Commissioner Pai proposed the establishment of a Task Force for the IP transition nine months ago, his intent was the removal of regulatory barriers to infrastructure investment, including unpredictability at the FCC. He suggested that the FCC send a clear signal that new IP networks built in competitive markets will not be subject to “broken, burdensome economic regulations” designed for monopoly telephone networks.

Last Friday’s Public Notice does just the opposite. It signals that even the worst excesses of legacy telephone regulation are still an option for the Internet. Specifically, the Public Notice “invites” telephone companies that are interested in comprehensive trials to submit a comprehensive plan listing, at a minimum:

(1) all of the services currently provided by the carrier in a designated wire center that the carrier would propose to phase out; (2) estimates of current demand for those services; and (3) what the replacement for those services would be, including current prices and terms and conditions under which the replacement services are offered.

It is telling that none of these enumerated questions are aimed at the potential technical issues posed by the IP transition (which is a forgone conclusion economically). They are aimed at economic issues relevant to the FCC’s traditional Title II price regulation of communications services.

In the nine months since Commissioner Pai began leading the IP transition, the FCC has signaled nothing more than its intent to continue bureaucratic business as usual. As the “real-world” continues its inexorable march toward our all-IP future, the FCC remains stuck in the mud fighting the regulatory wars of yesteryear, wielding its traditional weapon of bureaucratic delay to mask its own agenda. There it will remain until the FCC has a Chairman with a vision for the future, not the past.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower