Adam Thierer's Blog, page 63

June 11, 2013

Dick Thornburgh Is Mistaken: The New DOJ Spectrum Recommendation Is Inconsistent with Its Prior Approach to Mobile Competition

The Department of Justice has suddenly reversed course from its previous findings that mobile providers who lack spectrum below 1 GHz can become “strong competitors” in rural markets and are “well-positioned” to drive competition locally and nationally. Those supporting government intervention as a means of avoiding competition in the upcoming incentive auction attempt to avoid these findings by highlighting misleading FCC statistics, including the assertion that Verizon owns “approximately 45 percent of the licensed MHz-POPs of the combined [800 MHz] Cellular and 700 MHz band spectrum, while AT&T holds approximately 39 percent.”

Sprint Nextel Corporation (Sprint Nextel) recently sent a letter to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) signed by Dick Thornburgh, a former US Attorney General who is currently of counsel at K&L Gates, expressing his support for the ex parte submission of the Department of Justice (DOJ) that was recently filed in the FCC’s spectrum aggregation proceeding. The DOJ ex parte recommends that the FCC “ensure” Sprint Nextel and T-Mobile obtain a nationwide block of mobile spectrum in the upcoming broadcast incentive auction. In his letter of support on behalf of Sprint Nextel, Mr. Thornburgh states he believes the DOJ ex parte “is fully consistent with its longstanding approach to competition policy under Republican and Democratic administrations alike.”

Mr. Thornburgh is mistaken. The principle finding on which the DOJ’s new recommendation is based – that the FCC should adopt an inflexible, nationwide restriction on spectrum holdings below 1 GHz – is clearly inconsistent with the DOJ’s previous approach to competition policy in the mobile marketplace. Both the FCC and the DOJ have traditionally found that there is no factual basis for making competitive distinctions among mobile spectrum bands in urban markets, and the DOJ has distinguished among mobile spectrum bands only in rural markets.

In its 2006 complaint against the merger of Alltel and Western Wireless, the DOJ found that, in rural markets with relatively low population densities, it cost more to achieve broad mobile coverage using 1.9 GHz PCS spectrum, which made it less likely that providers with PCS spectrum would deploy in those markets. Based on that finding, the DOJ concluded that additional mobile entry would be difficult in certain rural markets in which the combined firm would own all available 800 MHz Cellular spectrum – the only mobile spectrum below 1 GHz that was available on a nationwide basis at that time.

In that same merger proceeding (I was the FCC Chairman’s wireless advisor at the time), the FCC refused to adopt the DOJ’s rural market distinction and instead maintained its traditional view that spectrum bands above 1 GHz are suitable for the provision of competitive services in both urban and rural markets.

Although the DOJ continued to apply its rural market distinction in subsequent merger reviews (i.e., Alltel/Midwest Wireless and AT&T/Dobson), it recognized that the distinction wasn’t reliably predictive in every rural market and was competitively irrelevant to nationwide competition. For example, in the 2008 Verizon/Alltel merger, the DOJ found that Verizon was a “strong competitor” in rural markets in which Verizon didn’t own any Cellular spectrum below 1 GHz, “because, unlike many other providers with PCS spectrum in rural areas, it has constructed a PCS network that covers a significant portion of the population.” Similarly, in its 2011 complaint against the proposed merger of AT&T and T-Mobile, the DOJ concluded that “T-Mobile in particular” was “especially well-positioned to drive competition, at both a national and local level,” in the mobile market even though T-Mobile owned very little spectrum below 1 GHz at that time.

The DOJ’s new recommendation is a sudden reverse in course from its previous findings that mobile providers who lack spectrum below 1 GHz can become “strong competitors” in rural markets and are “well-positioned” to drive competition locally and nationally.

The DOJ’s sudden reversal is particularly surprising given that the amount of spectrum below 1 GHz has increased substantially since the DOJ adopted its rural distinction in 2006. At that time, the 800 MHz Cellular band was the only spectrum band below 1 GHz that was broadband-capable and fully available on a nationwide basis. Since then, two additional sub-1 GHz spectrum bands capable of supporting mobile broadband services have become available on a nationwide basis – the 800 MHz SMR and 700 MHz bands. Sprint Nextel owns nearly all of the 800 MHz SMR band nationwide, T-Mobile acquired 700 MHz spectrum through its acquisition of MetroPCS this year, and many rural and regional mobile providers own 800 MHz Cellular and 700 MHz spectrum in rural areas across the country.

Those supporting government intervention as a means of avoiding competition in the upcoming incentive auction attempt to avoid these facts by highlighting misleading FCC statistics, including the assertion that Verizon owns “approximately 45 percent of the licensed MHz-POPs of the combined [800 MHz] Cellular and 700 MHz band spectrum, while AT&T holds approximately 39 percent.” This statistic is misleading in two respects.

First, this statistic excludes the 800 MHz SMR band, which is owned almost exclusively by Sprint Nextel. Excluding an entire spectrum band below one gigahertz from the statistical calculation creates the misleading impression that Verizon and AT&T hold a higher percentage of mobile spectrum below 1 GHz than they actually do.

Second, the FCC’s “MHz-POPs” methodology is weighted by population, which skews the resulting percentage of spectrum ownership significantly higher for companies that own spectrum in densely populated urban areas. A hypothetical using this methodology to calculate the percentage of “MHz-POPs” in the Cellular Market Areas (CMAs) covering the State of New York demonstrates just how skewed this methodology can be in the spectrum aggregation context.

Assume that “Company A” and “Company B” both own spectrum “Block X” (i.e., both companies own the same amount of spectrum in absolute terms) in different geographic areas in New York State. Specifically, assume that “Company A” owns “Block X” in geographic license area CMA001 (covering New York City and Newark, New Jersey), and “Company B” owns the same spectrum block in the other sixteen CMAs, including all six rural license areas in the state. If their spectrum holdings are calculated using the FCC’s population-weighted “MHz-POPs” methodology, “Company A” holds 70 percent of the “Block X” spectrum and “Company B” holds only 30 percent. (For an explanation of this methodology, see the “Technical Appendix” at the bottom of this post.)

As this example demonstrates, analyzing the percentage of spectrum mobile providers hold on a nationwide basis using the FCC’s “MHz-POPs” methodology is particularly misleading given the DOJ’s determination that spectrum below 1 GHz is competitively relevant only in sparsely populated rural areas. For example, if the FCC were to adopt a rule prohibiting any one mobile provider from holding 50% or more of the spectrum below 1 GHz in New York State on a “MHz-POPs” basis, “Company A” would be in violation of the rule even though it holds spectrum in only 1 market and doesn’t hold any spectrum in rural markets.

When the 800 MHz SMR band is included and spectrum holdings are evaluated on a market-by-market basis, at least four different mobile providers hold spectrum below 1 GHz in most markets – a result that wasn’t even possible in 2006 (absent nationwide spectrum disaggregation on the secondary market) when the DOJ adopted its rural distinction.

Mr. Thornburgh’s broad statements about the DOJ’s past approach to competition policy generally and the FCC’s skewed statistics are not legitimate, data-based substitutes for a detailed analysis of DOJ precedent and current spectrum holdings below 1 GHz in both urban and rural markets. A detailed analysis indicates that the DOJ’s new recommendation is not “fully consistent” with its previous approach to competition in the mobile marketplace, though it is consistent with a desire to rig the spectrum auction to favor certain competitors.

Technical Appendix

The FCC calculates “MHz-POPs” by multiplying the megahertz of spectrum held by a mobile provider in a given area by the population of that area.

The FCC also weights spectrum holdings by population using a “population-weighted average megahertz” calculation. The FCC calculates the nationwide “population-weighted average megahertz” of a mobile provider by dividing that provider’s “MHz-POPs” (as calculated above) by the US population.

The calculations for the New York State example in this blog post use “Cellular Market Areas,” which consist of Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and Rural Service Area (RSA) licenses as defined by the FCC in Public Notice Report No. CL-92-40, “Common Carrier Public Mobile Services Information, Cellular MSA/RSA Markets and Counties,” DA 92-109, 7 FCC Rcd. 742 (1992). The population figures are from the 2000 U.S. Census, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

Ethan Zuckerman on the connected world

Are we as globalized and interconnected as we think we are? Ethan Zuckerman, director of the MIT Center for Civic Media and author of the new book, Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection, argues that America was likely more globalized before World War I than it is today. Zuckerman discusses how we’re more focused on what’s going on in our own backyards; how this affects creativity; the role the Internet plays in making us less connected with the rest of the world; and, how we can broaden our information universe to consume a more healthy “media diet.”

Related Links

Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection, Zuckerman

What Ethan Zuckerman’s Rewire tells us about the internet changing our lives, Morrison

Rewire: Rethinking Globalization in an Age of Connection Zuckerman

June 10, 2013

The Media’s Sound and Fury Over NSA Surveillance

It was, to paraphrase Yogi Berra, déjà vu all over again. Fielding calls last week from journalists about reports the NSA had been engaged in massive and secret data mining of phone records and Internet traffic, I couldn’t help but wonder why anyone was surprised by the so-called revelations.

Not only had the surveillance been going on for years, the activity had been reported all along—at least outside the mainstream media. The programs involved have been the subject of longstanding concern and vocal criticism by advocacy groups on both the right and the left.

For those of us who had been following the story for a decade, this was no “bombshell.” No “leak” was required. There was no need for an “expose” of what had long since been exposed.

As the Cato Institute’s Julian Sanchez and others reminded us, the NSA’s surveillance activities, and many of the details breathlessly reported last week, weren’t even secret. They come up regularly in Congress, during hearings, for example, about renewal of the USA Patriot Act and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the principal laws that govern the activity.

In those hearings, civil libertarians (Republicans and Democrats) show up to complain about the scope of the law and its secret enforcement, and are shot down as being soft on terrorism. The laws are renewed and even extended, and the story goes back to sleep.

But for whatever reason, the mainstream media, like the corrupt Captain Renault in “Casablanca,” collectively found itself last week “shocked, shocked” to discover widespread, warrantless electronic surveillance by the U.S. government. Surveillance they’ve known about for years.

Let me be clear. As one of the long-standing critics of these programs, and especially their lack of oversight and transparency, I have no objection to renewed interest in the story, even if the drama with which it is being reported smells more than a little sensational with a healthy whiff of opportunism.

In a week in which the media did little to distinguish itself, for example, The Washington Post stood out, and not in a good way. As Ed Bott detailed in a withering post for ZDNet on Saturday, the Post substantially revised its most incendiary article, a Thursday piece that originally claimed nine major technology companies had provided direct access to their servers as part of the Prism program.

That “scoop” generated more froth than the original “revelation” that Verizon had been complying with government demands for customer call records.

Except that the Post’s sole source for its claims turned out to a PowerPoint presentation of “dubious provenance.” A day later, the editors had removed the most thrilling but unsubstantiated revelations about Prism from the article. Yet in an unfortunate and baffling Orwellian twist, the paper made absolutely no mention of the “correction.” As Bott points out, that violated not only common journalistic practice but the paper’s own revision and correction policy.

All this and much more, however, would have been in the service of a good cause–if, that is, it led to an actual debate about electronic surveillance we’ve needed for over a decade.

Unfortunately, it won’t. The mainstream media will move on to the next story soon enough, whether some natural or man-made disaster.

And outside the Fourth Estate, few people will care or even notice when the scandal dies. However they feel this week, most Americans simply aren’t informed or bothered enough about wholesale electronic surveillance to force any real accountability, let alone reform. Those who are up in arms today might ask themselves where they were for the last decade or so, and whether their righteous indignation now is anything more than just that.

As Politico’s James Hohmann noted on Saturday, “Government snooping gets civil libertarians from both parties exercised, but this week’s revelations are likely to elicit a collective yawn from voters if past polling is any sign.”

Why so pessimistic? I looked over what I’ve written on this topic in the past, and found the following essay, written in 2008, which appeared in slightly different form in my 2009 book, “The Laws of Disruption.” It puts the NSA’s programs in historical context, and tries to present both the costs and benefits of how they’ve been implemented. It points out why at least some aspects of these government activities are likely illegal, and what should be done to rein them in.

What I describe is just as scandalous, if not moreso, than anything that came out last week.

Yet I present it below with the sad realization that if I were writing it today–five years later–I wouldn’t need to change a single word. Except maybe the last sentence. And then, just maybe.

Searching Bits, Seizing Information

U.S. citizens are protected from unreasonable search and seizure of their property by their government. In the Constitution, that right is enshrined in the Fourth Amendment, which was enacted in response to warrantless searches by British agents in the run-up to the Revolutionary War. Over the past century, the Supreme Court has increasingly seen the Fourth Amendment as a source of protection for personal space—the right to a “zone of privacy” that governments can invade only with probable cause that evidence of a crime will be revealed.

Under U.S. law, Americans have little in the way of protection of their privacy from businesses or from each other. The Fourth Amendment is an exception, albeit one that applies only to government.

But digital life has introduced new and thorny problems for Fourth Amendment law. Since the early part of the twentieth century, courts have struggled to extend the “zone of privacy” to intangible interests—a right to privacy, in other words, in one’s information. But to “search” and “seize” implies real world actions. People and places can be searched; property can be seized.

Information, on the other hand, need not take physical form, and can be reproduced infinitely without damaging the original. Since copies of data may exist, however temporarily, on thousands of random computers, in what sense do netizens have “property” rights to their information? Does intercepting data constitute a search or a seizure or neither?

The law of electronic surveillance avoids these abstract questions by focusing instead on a suspect’s expectations. Courts reviewing challenged investigations ask simply if the suspect believed the information acquired by the government was private data and whether his expectation of privacy was reasonable.

It is not the actual search and seizure that the Fourth Amendment forbids, after all, but unreasonable search and seizure. So the legal analysis asks what, under the circumstances, is reasonable. If you are holding a loud conversation in a public place, it isn’t reasonable for you to expect privacy, and the police can take advantage of whatever information they overhear. Most people assume, on the other hand, that data files stored on the hard drive of a home computer are private and cannot be copied without a warrant.

One problem with the “reasonable expectation” test is that as technology changes, so do user expectations. The faster the Law of Disruption accelerates, the more difficult it is for courts to keep pace. Once private telephones became common, for example, the Supreme Court required law enforcement agencies to follow special procedures for the search and seizure of conversations—that is, for wiretaps. Congress passed the first wiretap law, known as Title III, in 1968. As information technology has revolutionized communications and as user expectations have evolved, the courts and Congress have been forced to revise Title III repeatedly to keep it up to date.

In 1986, the Electronic Communications Privacy Act amended Title III to include new protection for electronic communications, including e-mail and communications over cellular and other wireless technologies. A model of reasonable lawmaking, the ECPA ensured these new forms of communication were generally protected while closing a loophole for criminals who were using them to evade the police. (By 2005, 92 percent of wiretaps targeted cell phones.)

As telephone service providers multiplied and networks moved from analog to digital, a 1994 revision required carriers to build in special access for investigators to get around new features such as call forwarding. Once a Title III warrant is issued, law enforcement agents can now simply log in to the suspect’s network provider and receive real-time streams of network traffic.

Since 1968, Title III has maintained an uneasy truce between the rights of citizens to keep their communications private and the ability of law enforcement to maintain technological parity with criminals. As the digital age progresses, this balance is harder to maintain. With each cycle of Moore’s Law, criminals discover new ways to use digital technology to improve the efficiency and secrecy of their operations, including encryption, anonymous e-mail resenders, and private telephone networks. During the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, for example, co-conspirators used television reports of police activity to keep the gunmen at various sites informed, using Internet telephones that were hard to trace.

As criminals adopt new technologies, law enforcement agencies predictably call for new surveillance powers. China alone employs more than 30,000 “Internet police” to monitor online traffic, what is sometimes known as the “Great Firewall of China.” The government apparently intercepts all Chinese-bound text messages and scans them for restricted words including democracy, earthquake, and milk powder.

The words are removed from the messages, and a copy of the original along with identifying information is stored on the government’s system. When Canadian human rights activists recently hacked into Chinese government networks they discovered a cluster of message-logging computers that had recorded more than a million censored messages.

Netizens, increasingly fearful that the arms race between law enforcement and criminals will claim their privacy rights as unintended victims, are caught in the middle. Those fears became palpable after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and those that followed in Indonesia, London, and Madrid. The world is now engaged in a war with no measurable objectives for winning, fought against an anonymous and technologically savvy enemy who recruits, trains, and plans assaults largely through international communication networks. Security and surveillance of all varieties are now global priorities, eroding privacy interests significantly.

The emphasis on security over privacy is likely to be felt for decades to come. Some of the loss has already been felt in the real world. To protect ourselves from future attacks, everyone can now expect more invasive surveillance of their activities, whether through massive networks of closed-circuit TV cameras in large cities or increased screening of people and luggage during air travel.

The erosion of privacy is even more severe online. Intelligence is seen as the most effective weapon in a war against terrorists. With or without authorization, law enforcement agencies around the world have been monitoring large quantities of the world’s Internet data traffic. Title III has been extended to private networks and Internet phone companies, who must now insert government access points into their networks. (The FCC has proposed adding other providers of phone service, including universities and large corporations.)

Because of difficulties in isolating electronic communications associated with a single IP address, investigators now demand the complete traffic of large segments of addresses, that is, of many users. Data mining technology is applied after the fact to search the intercepted information for the relevant evidence.

Passed soon after 9/11, the USA Patriot Act went much further. The Patriot Act abandoned many of the hard-fought controls on electronic surveillance built into Title III. New “enhanced surveillance procedures” allow any judge to authorize electronic surveillance and lower the standard for warrants to seize voice mails.

The FBI was given the power to conduct wiretaps without warrants and to issue so-called national security letters to gag network operators from revealing their forced cooperation. Under a 2006 extension, FBI officials were given the power to issue NSLs that silenced the recipient forever, backed up with a penalty of up to five years in prison.

Gone is even a hint of the Supreme Court’s long-standing admonitions that search and seizure of information should be the investigatory tool of last resort.

Despite the relaxed rules, or perhaps inspired by them, the FBI acknowledged in 2007 that it had violated Title III and the Patriot Act repeatedly, illegally searching the telephone, Internet, and financial records of an unknown number of Americans. A Justice Department investigation found that from 2002 to 2005 the bureau had issued nearly 150,000 NSLs, a number the bureau had grossly under-reported to Congress.

Many of these letters violated even the relaxed requirements of the Patriot Act. The FBI habitually requested not only a suspect’s data but also those of people with whom he maintained regular contact—his “community of interest,” as the agency called it. “How could this happen?” FBI director Robert Mueller asked himself at the 2007 Senate hearings on the report. Mueller didn’t offer an answer.

Ultimately, a federal judge declared the FBI’s use of NSLs unconstitutional on free-speech grounds, a decision that is still on appeal. The National Security Agency, which gathers foreign intelligence, undertook an even more disturbing expansion of its electronic surveillance powers.

Since the Constitution applies only within the U.S., foreign intelligence agencies are not required to operate within the limits of Title III. Instead, their information- gathering practices are held to a much more relaxed standard specified in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. FISA allows warrantless wiretaps anytime that intercepted communications do not include a U.S. citizen and when the communications are not conducted through U.S. networks. (The latter restriction was removed in 2008.)

Even these minimal requirements proved too restrictive for the agency. Concerned that U.S. operatives were organizing terrorist attacks electronically with overseas collaborators, President Bush authorized the NSA to bypass FISA and conduct warrantless electronic surveillance at will as long as one of the parties to the information exchange was believed to be outside the United States.

Some of the president’s staunchest allies found the NSA’s plan, dubbed the Terrorist Surveillance Program, of dubious legality. Just before the program became public in 2005, senior officials in the Justice Department refused to reauthorize it.

In a bizarre real-world game of cloak-and-dagger, presidential aides, including future attorney general Alberto Gonzales, rushed to the hospital room of then-attorney general John Ashcroft, who was seriously ill, in hopes of getting him to overrule his staff. Justice Department officials got wind of the end run and managed to get to Ashcroft first. Ashcroft, who was barely able to speak from painkillers, sided with his staff.

Many top officials, including Ashcroft and FBI director Mueller, threatened to resign over the incident. President Bush agreed to stop bypassing the FISA procedure and seek a change in the law to allow the NSA more flexibility. Congress eventually granted his request.

The NSA’s machinations were both clumsy and dangerous. Still, I confess to having considerable sympathy for those trying to obtain actionable intelligence from online activity. Post-9/11 assessments revealed embarrassing holes in the technological capabilities of most intelligence agencies worldwide. (Admittedly, it also revealed repeated failures to act on intelligence that was already collected.) Initially at least, the public demanded tougher measures to avoid future attacks.

Keeping pace with international terror organizations and still following national laws, however, is increasingly difficult. For one thing, communications of all kinds are quickly migrating to the cheaper and more open architecture of the Internet. An unintended consequence of this change is that the nationalities of those involved in intercepted communications are increasingly difficult to determine.

E-mail addresses and instant-message IDs don’t tell you the citizenship or even the location of the sender or receiver. Even telephone numbers don’t necessarily reveal a physical location. Internet telephone services such as Skype give their customers U.S. phone numbers regardless of their actual location. Without knowing the nationality of a suspect, it is hard to know what rights she is entitled to.

The architecture of the Internet raises even more obstacles against effective surveillance. Traditional telephone calls take place over a dedicated circuit connecting the caller and the person being called, making wiretaps relatively easy to establish. Only the cooperation of the suspect’s local exchange is required.

The Internet, however, operates as a single global exchange. E-mails, voice, video, and data files—whatever is being sent is broken into small packets of data. Each packet follows its own path between connected computers, largely determined by data traffic patterns present at the time of the communication.

Data may travel around the world even if its destination is local, crossing dozens of national borders along the way. It is only on the receiving end that the packets are reassembled.

This design, the genius of the Internet, improves network efficiency. It also provides a significant advantage to anyone trying to hide his activities. On the other hand, NSLs and warrantless wiretapping on the scale apparently conducted by the NSA move us frighteningly close to the “general warrant” American colonists rejected in the Fourth Amendment. They were right to revolt over the unchecked power of an executive to do what it wants, whether in the name of orderly government, tax collection, or antiterrorism.

In trying to protect its citizens against future terror attacks, the secret operations of the U.S. government abandoned core principles of the Constitution. Even with the best intentions, governments that operate in secrecy and without judicial oversight quickly descend into totalitarianism. Only the intervention of corporate whistle-blowers, conscientious government officials, courts, and a free press brought the United States back from the brink of a different kind of terrorism.

Internet businesses may be entirely supportive of government efforts to improve the technology of policing. A society governed by laws is efficient, and efficiency is good for business. At the same time, no one is immune from the pressures of anxious customers who worry that the information they provide will be quietly delivered to whichever regulator asks for it. Secret surveillance raises the level of customer paranoia, leading rational businesses to avoid countries whose practices are not transparent.

Partly in response to the NSA program, companies and network operators are increasingly routing information flow around U.S. networks, fearing that even transient communications might be subject to large-scale collection and mining operations by law enforcement agencies. But aside from using private networks and storing data offshore, routing transmissions to avoid some locations is as hard to do as forcing them through a particular network or node.

The real guarantor of privacy in our digital lives may not be the rule of law. The Fourth Amendment and its counterparts work in the physical world, after all, because tangible property cannot be searched and seized in secret. Information, however, can be intercepted and copied without anyone knowing it. You may never know when or by whom your privacy has been invaded. That is what makes electronic surveillance more dangerous than traditional investigations, as the Supreme Court realized as early as 1967.

In the uneasy balance between the right to privacy and the needs of law enforcement, the scales are increasingly held by the Law of Disruption. More devices, more users, more computing power: the sheer volume of information and the rapid evolution of how it can be exchanged have created an ocean of data. Much of it can be captured, deciphered, and analyzed only with great (that is, expensive) effort. Moore’s Law lowers the costs to communicate, raising the costs for governments interested in the content of those communications.

The kind of electronic surveillance performed by the Chinese government is outrageous in its scope, but only the clumsiness of its technical implementation exposed it. Even if governments want to know everything that happens in our digital lives, and even if the law allows them or is currently powerless to stop them, there isn’t enough technology at their disposal to do it, or at least to do it secretly.

So far.

June 6, 2013

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief Guard Band Systems

This post is a parody of “

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

” written by Galileo Galilei in 1632, which attempted to prove that the earth revolves around the sun (the Copernican system). Although the Copernican system was ultimately proven to be scientifically correct, Galileo was convicted of heresy and his book was placed on the Index of Forbidden Books for more than two hundred years.

Galileo’s book was written as a dialogue between three characters, Salviati, who supported Galileo’s view, Simplicio, who believed the universe revolves around the earth (the Ptolemaic system), and Sagredo, an open-minded person with no established position. In this parody, Salviati supports the use of actual or de facto guard bands between broadcast and mobile services, Simplicio supports the FCC’s competing guard band proposals in the 600 MHz and 700 MHz bands, and Sagredo remains open-minded.

INTERLOCUTORS

Salviati, Sagredo, Simplicio

SALVIATI. We resolved to meet today and discuss the differences in the FCC’s approach to the potential for harmful interference between broadcast and mobile services in the 600 MHz band on the one hand and the lower 700 MHz band on the other.

To prevent harmful interference between broadcast and mobile services in the 600 MHz band, the FCC has proposed separating these services with guard bands in which neither service would be allowed to operate. To make this easier to understand, let us use this tablet to illustrate the FCC’s proposed 600 MHz band plan and other such matters as they arise during our discussion.

The FCC adopted a very different approach to this issue in the 700 MHz band. Rather than require a spectral guard band between broadcast and mobile services, the FCC created geographic exclusion zones to protect broadcast services from the potential for harmful interference from mobile services in the lower 700 MHz A Block.

The FCC considered imposing additional limitations to protect mobile services in the A Block from broadcast services in Channel 51, but ultimately decided to provide A Block licensees with the flexibility to account for harmful interference through their own business plans, services, and facilities.

As a result, the 3GPP defined two LTE band classes for paired spectrum in the lower 700 MHz band:

Band Class 17, which uses the A Block as a de facto guard band separating mobile services in the lower 700 MHz B and C Blocks from broadcast services in Channel 51; and

Band Class 12, which has no guard band.

A group of A Block licensees subsequently filed a petition asking the FCC to initiate a rulemaking proceeding to require that all devices operating on paired commercial spectrum in the 700 MHz band be capable of operating on all paired frequencies in the band and also to suspend authorization of 700 MHz devices that are incapable of operating on all such frequencies. Last year the FCC initiated a rulemaking proceeding to evaluate whether the lower 700 MHz B and C Blocks would experience harmful interference, and to what degree, if the FCC were to impose an interoperability mandate.

It would appear that the FCC has since answered the first question, whether eliminating the de facto guard band in 3GPP Band Class 17 would cause harmful interference, by proposing 6 MHz guard bands between broadcast and mobile services in the 600 MHz band.

SIMPLICIO. The 600 MHz band uses different frequencies than the 700 MHz band, and different frequencies have different characteristics. The FCC has often adopted different rules for different frequency bands. If the potential for harmful interference between broadband mobile services were similar in both bands, the FCC would not have omitted that fact.

SAGREDO. You might at least add, “if it had occurred to the FCC to consider the question.” If the FCC were to consider it, could the FCC plausibly conclude that the potential for harmful interference between broadcast and mobile services is substantially different in the 600 MHz band?

SALVIATI. Your question seems to me most excellent. Though I grant that the FCC adopts spectrum rules on an ad hoc basis, I feel no compulsion to grant that the arbitrary distinctions of FCC process confer legitimacy on question of physics. Whether the potential for harmful interference is substantially the same in the 600 MHz and 700 MHz bands is a question amenable to answer only by demonstrative science, not speculation regarding past FCC actions and current omissions.

Neither the FCC nor the industry has adduced any evidence that the potential for harmful interference varies substantially between the 600 MHz and 700 MHz bands. To the contrary, the available evidence indicates that the potential for harmful interference in these bands is substantially similar due their relatively close proximity within the electromagnetic spectrum and the fact that the phenomena responsible for interference between broadcast and mobile services are not frequency dependent.

SIMPLICIO. I do not mean to join the number of those who are too curious about the mysteries of physics. But as to the point at hand, I reply that licensees in the A Block are asking the FCC to impose an interoperability mandate for competitive reasons. AT&T, who owns spectrum in the lower 700 MHz B and C Blocks, has deployed only Band Class 17, which excludes the A Block. Licensees in the A Block must use Band Class 12, which is not supported by AT&T. That is preventing A Block licensees from taking advantage of AT&T’s economies of scale for purchasing devices and roaming on its network. This seems to be conclusive evidence that AT&T excluded Band Class 12 from its B and C Block devices to raise the costs of its rivals, a form of anticompetitive behavior.

SAGREDO: I do not claim to comprehend the mysteries of physics, but I have some knowledge of the laws governing competition. The law does not penalize a company merely for being successful in the marketplace – it prohibits only anticompetitive behavior that is “unreasonable” or “wrongful.” The fact that AT&T’s decision to deploy Band Class 17 may incidentally raise its rivals’ costs is irrelevant if AT&T had legitimate business reasons to make that decision.

SALVIATI. Exactly so, which brings us full circle. Whether AT&T had legitimate reasons to deploy Band Class 17 depends on the laws of physics. If deploying Band Class 12 has the potential to cause harmful interference to the B and C Blocks, AT&T’s decisions to deploy Band Class 17 cannot be considered anticompetitive.

SIMPLICIO. What about the expectations of the A Block licensees? Band Class 17 was not proposed to the 3GPP until after the 700 MHz auction was completed. It seems legitimate to me that the FCC honor their expectation that all licensees would deploy Band Class 12.

SALVIATI. Another question answers yours. Did the FCC require or even encourage the deployment of interoperable devices in the 700 MHz band?

SIMPLICIO. You already know the answer. The FCC clearly said licensees could make their own determinations respecting the services and technologies they deploy in the band so long as they comply with the FCC’s technical rules. What does that have to do with the expectations of the A Block licensees?

SALVIATI. It demonstrates that the ostensible expectations of the A Block licensees were unreasonable. The FCC’s rules clearly gave B and C block licensees the absolute right to eschew deploying Band Class 12, and it was reasonably foreseeable that B and C Block licensees would exercise that right given the potential for harmful interference inherent in Band Class 12. Based on the FCC’s rules, the ostensible expectation of the A Block licensees is more reasonably categorized as a blind hope or a calculated risk. On average, the A Block licensees paid less than half the price the B Block licensees paid for the same amount of spectrum. If the B Block licensees had decided to deploy Band Class 12, the A Block licensees would have enjoyed access to maximal economies of scale while the B Block licensees suffered from the same interference potential at twice the price. If not, the A Block licensees knew that they could still deploy Band Class 12 on their own at half the price.

SIMPLICIO. You say the A Block licensees could still deploy Band Class 12 systems in their spectrum, but they say they cannot deploy without AT&T’s help. Why should I favor your position over theirs?

SALVIATI. Experience proves my position is correct. US Cellular, one of the A Block licensees who petitioned the FCC in this matter, has already deployed Band Class 12 in its A Block spectrum.

SAGREDO. I cannot without great astonishment – I might say without great insult to my intelligence – hear it said that something cannot be done that has already been done. I submit that I am better satisfied with your discourse than that of the A Block licensees in respect to the competitive and economic issues. But my knowledge is insufficient to reach my own conclusion regarding the physics. Perhaps AT&T was acting unreasonably when it chose to use the A Block as a de facto guard band to protect its operations in the C and B Blocks from harmful interference.

SALVIATI. That is the question Simplicio dreads. He knows that, if the FCC answers that question in the affirmative, it cannot establish guard bands in the 600 MHz band. The law governing the 600 MHz band provides that “guard bands shall be no larger than is technically reasonable to prevent harmful interference between licensed services outside the guard bands.” It can hardly be technically reasonable to require a 6 MHz guard band in the 600 MHz band while finding it was technically unreasonable for AT&T to treat the 6 MHz A Block as a de facto guard band given the evidence that the interference potential is substantially the same.

SAGREDO. Let us close our discussions for the day. The honest hours being past, I think Simplicio might like to contemplate this question during our cool ones. Tomorrow I shall expect you both so that we may continue the discussions now begun.

June 4, 2013

White House announces new steps on patent reform

Today, the Obama administration announced 5 executive actions it is taking and 7 legislative proposals it is making to address the problem of patent trolls. While these are incremental steps in the right direction, they are still pretty weak sauce. The reforms could alleviate some of the litigation pressure on Silicon Valley firms, but there’s a long way to go if we want to have a patent system that maximized innovation.

The proposals aim to reduce anonymity in patent litigation, improve review at the USPTO, give more protection to downstream users, and improve standards at the International Trade Commission, a venue which has been gamed by patent plaintiffs. These are all steps worth taking. But they’re not enough. The White House’s press release quotes the president as saying that “our efforts at patent reform [i.e. the America Invents Act, passed in 2011] only went about halfway to where we need to go.” Presumably the White House believes these steps will take us the rest of the way there.

But the problem with computer-enabled patents isn’t merely that they result in a lot of opportunistic litigation, though they do. The problem is that almost every new idea is actually pretty obvious, in the sense that it is “invented” at the same time by lots of companies that are innovating in the same space. Granting patents in a field where everyone is innovating in the same way at the same time is a recipe for slowing down, not speeding up, innovation. Instead of just getting on with the process of building great new products, companies have to file for patents, assemble patent portfolios, license patents from competitors who “invented” certain software techniques a few months earlier, deal with litigation, and so on. A device like a smartphone requires thousands of patents to be filed, licensed, or litigated.

If we really want to speed up innovation, we need to take bolder steps. New Zealand recently abolished software patents by declaring that software is not an invention at all. It would be terrific if the White House would get behind that kind of bold thinking. In the meantime, we’ll have to watch closely as the Obama administration’s executive actions are implemented and its legislative recommendations move through Congress. I hope for the best, but for now I’m not too impressed.

Federal agencies have too much spectrum

Few dispute that mobile carriers are being squeezed by the relative scarcity of radio spectrum. This scarcity is a painful artifact of regulatory decisions made decades ago, when the regulators gave valuable spectrum away for free to government agencies and to commercial users via so-called “beauty contests.” As more Americans purchase tablets and smartphones (as of a year ago, smartphones comprise a majority of phone plans in the US), many fear that consumers will be hurt by higher prices, stringent data limits, and less wireless innovation.

In the face of this demand, freeing up more airwaves for mobile broadband became a bipartisan effort and many scholars and policymakers have turned their hungry eyes to the ample spectrum possessed by federal agencies, which hold around 1500 MHz of the most valuable bands. The scholarly consensus for years–confirmed by government audits–is that federal agencies use their spectrum poorly. Because many licensees use spectrum under the old rules (free spectrum) and use it inefficiently, President Obama directed the FCC and NTIA to find 500 MHz of spectrum for mobile broadband use by 2020.

I recently published a Mercatus working paper surveying plans that encourage federal agencies to economize on their use of radio spectrum, with the ultimate goal of auctioning cleared spectrum to the highest bidders (probably mobile broadband service providers given consumer needs). In my research, interviewees pointed to two problems with reclaiming federal spectrum: (a) there is no effective process to get federal users (especially the powerful Department of Defense) to turn over spectrum, and (b) federal users don’t pay market prices for spectrum, resulting in inefficient use and billions of dollars of value annually wasted.

I’ll note two of the promising spectrum management plans here. As for improving the process of quickly getting federal spectrum auctioned off, there is a bill, authored by Sen. Kirk and Rep. Kinzinger, to “BRAC the spectrum.” BRAC (the Base Realignment and Closure procedure), as Jerry Brito documents, was a move by Congress in 1988 to successfully accomplish the politically difficult task of closing military bases. BRAC-ing the spectrum would mean the congressional creation of a commission with the authority to clear federal users out of their spectrum. All spectrum-clearing decisions by this commission during its tenure would stand, absent a disapproving joint resolution from Congress. The identified spectrum could be auctioned off within a few years and the proceeds could be used to move the federal systems to other bands, with the remainder going to the Treasury.

The second proposal I highlight is the creation of a GSA-like agency that controls federal spectrum. This proposal, from Thomas Lenard, Lawrence White, and James Riso, would accomplish the second goal of making federal users pay substantial fees for their spectrum. The federal government pays market rates for many important inputs–tanks, carriers, land, etc.–so why is spectrum free? The GSA, the authors explain, owns real estate and buildings and it leases those to federal agencies. Just as paying rent forces federal agencies to economize on building size and amenities, a “GSA for spectrum” would lease spectrum to agencies, hopefully preventing the sort of waste currently seen in federal bands.

I’m probably the first TLF author to favor the creation of 2 new federal agencies in a post (hopefully not my last!), but these proposals may be necessary given the damaging status quo. Federal waste of spectrum assets isn’t disputed and the consumer benefits of freeing up spectrum are obvious. The fight lies primarily between powerful interest groups and affected congressional committees, some of whom will see their constituent oxen gored (DoD, defense contractors, technology firms). Given the urgent needs, it’s foolish to continue to do nothing.

June 3, 2013

David Garcia on social resilience in online communities

David Garcia, post doctoral researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and co-author of Social Resilience in Online Communities: The Autopsy of Friendster, discusses the concept of social resilience and how online communities, like Facebook and Friendster, withstand changes in their environment.

Garcia’s paper examines one of the first online social networking sites, Friendster, and analyzes its post-mortem data to learn why users abandoned it.

Garcia goes on to explain how opportunity cost and cost benefit analysis can affect a user’s decision whether or not to remain in an online community.

Related Links

Social Resilience in Online Communities: The Autopsy of Friendster, Garcia, Mavrodiev, Schweitzer

An autopsy of a dead social network, The Physics arXiV Blog

Researchers conduct ‘autopsy’ of dead social network Friendster, Solon

June 2, 2013

Free Speech Has Consequences & Counter-Speech Is a Vital Part of Deliberative Democracy

Alexander Howard has put together this excellent compendium of comments on Mike Rosenwald’s new Washington Post editorial, “Will the Twitter Police make Twitter boring?” I was pleased to see that so many others had the same reaction to Rosenwald’s piece that I did.

For the life of me, I cannot understand how anyone can equate counter-speech with “Twitter Police,” but that’s essentially what Rosenwald does in his essay. The examples he uses in his essay are exactly the sort of bone-headed and generally offensive comments that I would hope we would call out and challenge robustly in a deliberative democracy. But when average folks did exactly that, Rosenwald jumps to the preposterous conclusion that it somehow chilled speech. Stranger yet is his claim that “the Twitter Police are enforcing laws of their own making, with procedures they have authorized for themselves.” Say what? What laws are you talking about, Mike? This is just silly. These people are SPEAKING not enforcing any “laws.” They are expressing opinions about someone else’s (pretty crazy) opinions. This is what a healthy deliberative democracy is all about, bud!

Moreover, Rosenwald doesn’t really explain what a better world looks like. Is it one in which we all just turn a blind eye to what many regard as offensive or hair-brained commentary? I sure hope not!

I’m all for people vigorously expressing their opinions but I am just as strongly in favor of people pushing back with opinions of their own. You have no right to be free of social sanction if your speech offends large swaths of society. Speech has consequences and the more speech it prompts, the better.

May 31, 2013

FCC Wireless Bureau Ignores Incentives in the Broadcast Incentive Auction

” . . . the cooperative process envisioned by the National Broadband Plan is at risk of shifting to the traditionally contentious band plan process that has delayed spectrum auctions in the past.”

The National Broadband Plan proposed a new way to reassign reallocated spectrum. The Plan noted that, “Contentious spectrum proceedings can be time-consuming, sometimes taking many years to resolve, and incurring significant opportunity costs.” It proposed “shifting [this] contentious process to a cooperative one” to “accelerate productive use of encumbered spectrum” by “motivating existing licensees to voluntarily clear spectrum through incentive auctions.” Congress implemented this recommendation through legislation requiring the FCC to transition additional broadcast spectrum to mobile use through a voluntary incentive auction process rather than traditional FCC mandates.

Among other things, the FCC’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking initiating the broadcast incentive auction proceeding proposed a “lead” band plan approach and several alternative options, including the “down from 51” approach. An overwhelming majority of broadcasters, wireless providers, equipment manufacturers, and consumer groups rejected the “lead” approach and endorsed the alternative “down from 51” approach. This remarkably broad consensus on the basic approach to the band plan promised to meet the goals of the National Broadband Plan by accelerating the proceeding and motivating voluntary participation in the auction.

That promise was broken when the FCC’s Wireless Bureau unilaterally decided to issue a Public Notice seeking additional comment on a variation of the FCC’s “lead” proposal as well as a TDD approach to the band plan. The Bureau issued this notice over the objection of FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai, who issued a separate statement expressing his concern that seeking comment on additional approaches to the band plan when there is a “growing consensus” in favor of the “down from 51” approach could unnecessarily delay the incentive auction. This statement “peeved” Harold Feld, Senior Vice President at Public Knowledge, who declared that there is no consensus and that the “down from 51” plan would be a “disaster.” As a result, the cooperative process envisioned by the National Broadband Plan is at risk of shifting to the traditionally contentious band plan process that has delayed spectrum auctions in the past.

Consumer groups, including Public Knowledge, acknowledged the consensus

Mr. Feld’s “pique” with Commissioner Pai’s view that the “down from 51” approach had become the “consensus framework” for the 600 MHz band plan is surprising. According to Mr. Feld, Sprint, Microsoft, and the Public Interest Spectrum Coalition (PISC) objected to the “down from 51” approach. As support for this position, Mr. Feld cited reply comments filed by the PISC, a coalition that includes, among others, Public Knowledge.

Contrary to Mr. Feld’s assertion, however, the PISC reply comments support Commissioner Pai’s view. The PISC reply comments expressly state that there is a “consensus in favor of a 51-down band plan with a duplex gap,” which is “supported as technically superior by virtually all major industry commenters.”

To be sure, after Commissioner Pai issued his statement, Mr. Feld met with the Wireless Bureau to state for the record that there is no consensus support for the “down from 51” approach. Prior to that meeting, however, Public Knowledge had not expressed that view.

Why has Mr. Feld suddenly become so vehemently opposed to the “down from 51” approach?

“Down from 51” would not reduce revenue

Mr. Feld claims that the “down from 51” approach embraced by the broadcasters and “so many carriers and equipment manufacturers” would be an “absolute disaster” for that very reason – i.e., most of the industry supports it. In Mr. Feld’s view, the fact that the overwhelming majority of industry participants support the “down from 51” approach is evidence that they are “colluding” to reduce auction revenue.

Although the service rules and auction revenue are to some extent interdependent, insofar as band plans are concerned, wireless providers have far greater incentives to promote spectral and operational efficiency than to reduce auction prices. The costs of building and operating wireless networks are significantly higher than the one-time costs of acquiring spectrum at auction, and consumer demand for wireless broadband capacity is rapidly increasing. Given these facts, no rational wireless provider has an incentive to promote a band plan designed to reduce auction revenue.

In any event, Mr. Feld’s theory that the “down from 51” approach could reduce revenue by making too much spectrum available is irrelevant to the band plan issue. Even assuming his theory is correct, the FCC’s other proposed approaches to the band plan, none of which “cap” the amount of spectrum that would be accepted in the reverse auction, would run the same risk. Similarly, Mr. Feld’s proposed solution of limiting the amount of spectrum accepted in the reverse auction could be applied to any approach to the band plan, including “down from 51.”

“Down from 51” is not anticompetitive

Mr. Feld claims that the “down from 51” approach is anticompetitive because, in his view, wireless providers that lack spectrum below 1 GHz “are the only ones capable of using the downlink spectrum, and even then only if they bid exclusively on the supplementary downlinks.” According to Mr. Feld, this means such providers will bid only on the downlink spectrum and leave the paired spectrum to Verizon and AT&T even though, in his view, providers that lack spectrum below 1 GHz are the ones that “most need” uplink spectrum.

Of course, if this were true, it would be irrational for any wireless provider to join Verizon and AT&T in supporting the “down from 51” approach. Yet, T-Mobile, the only nationwide provider that lacks nationwide spectrum below 1 GHz, is a signatory to the “Joint Accord” supporting the “down from 51” approach, an approach that is also supported by rural and regional providers.

Given the current state of the record, a finding based on Mr. Feld’s hypothesis would require the FCC to assume that wireless providers generally behave irrationally when developing band plans – an assumption so absurd it would fail even the most deferential application of the Chevron standard for judicial review.

“Down from 51” is not inefficient

Mr. Feld claims the “down from 51” approach is spectrally inefficient because it “maximizes the total number of guard bands” while retaining a duplex gap.

To the contrary, the “down from 51” approach proposed by the FCC would require the minimum total number of guard bands while retaining a duplex gap: one.

If enough spectrum is cleared to place the guard band adjacent to Channel 37 as proposed by T-Mobile, the “down from 51” approach would also minimize the amount of spectrum that must be allocated to guard bands. This specific version of the “down from 51” approach would require a total of only 4 MHz of guard band spectrum while providing 10 MHz of protection against interference (6 MHz in Channel 37 plus an additional 4 MHz yielded by broadcasters in the reverse auction).

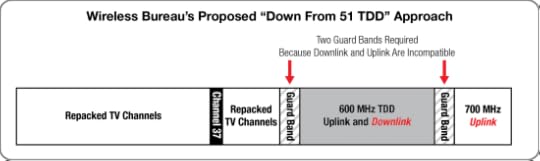

In comparison, the “down from 51 reversed” approach proposed by the Wireless Bureau in the Public Notice would require at least two guard bands.

If the FCC intends to maximize spectral efficiency by minimizing the total number of guard bands, it will not adopt the “down from 51 reversed” approach proposed by the Wireless Bureau. That is why the FCC proposed to place the 600 MHz uplink band adjacent to the lower 700 MHz uplink band in the “lead” proposal in its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

A TDD approach is inefficient

Mr. Feld claims that a “down from 51 TDD” approach would make “maximum use” of spectrum above Channel 37 because it would eliminate the duplex gap required for FDD deployments. He neglects to mention, however, that a TDD approach would require an additional guard band that would be the same or substantially similar in size to the FDD duplex gap in the “down from 51″ approach. Compare the FCC’s “down from 51” approach with the Wireless Bureau’s “down from 51 TDD” approach:

As I’ve noted previously, the switching times inherent in LTE TDD systems also produce latency and reduce coverage – issues that would be exacerbated in rural deployments in the 600 MHz band. LTE TDD operates in two modes: a 10-millisecond mode (more latency, but more coverage) and a 5-millisecond mode (less latency, but less coverage). In the 10-millisecond mode, LTE TDD is generally not suitable for the streaming applications that stress mobile networks the most (e.g., video chat applications). In the 5-millisecond mode, LTE TDD is generally suitable for streaming applications, but suffers from significantly reduced coverage. According to Qualcomm, in a coverage-limited system using the same frequency, TDD requires 31 to 65 percent more base stations than FDD to maintain the same throughput.

This doesn’t mean that TDD technologies have no role to play in the wireless marketplace. In the absence of channel aggregation opportunities, TDD is the only choice when paired spectrum is unavailable. It can also be used to enhance capacity when coverage is not the delimiting factor.

The primary driver behind LTE TDD deployment generally, however, appears to be Chinese industrial policy, not spectral efficiency. After China’s TDD-based SCDMA technology failed to gain traction internationally, it focused its efforts on developing a TDD version of LTE that would be backward compatible with its SCDMA standard and expand China’s technological influence globally. As a result, China became the primary promoter of the LTE TDD standard and a major owner of the standard’s essential patents (i.e., Huawei states that it leads the world in essential LTE patents). Based on likely deployment scenarios in the 600 MHz band, an FCC-mandated TDD approach would benefit Chinese patent holders, not American consumers.

The Public Notice Should Not Have Been Issued by the Bureau

Finally, Mr. Feld accused Commissioner Pai of “poisoning” the rulemaking process by calling attention to the Wireless Bureau’s disregard for his role as a Commissioner. Mr. Feld portrayed the Public Notice as a routine matter, but as a former Chief of the Wireless Bureau, I know that Bureaus do not circulate routine items to the Commissioners. A Bureau typically circulates an item to the Commissioners with a waiting period only when its authority to issue the item at the Bureau-level is unclear. If a Commissioner objects to the issuance of the item at the Bureau level, established practice requires that it be submitted to the Commission for a vote.

In my experience, the Bureau’s decision to ignore Commissioner Pai’s objection was, at a minimum, a serious breach of comity and established protocol. If anything “poisoned” the process in this instance, it was the Bureau’s insistence on issuing a Public Notice on authority delegated to it by the Commission over the objection of a Commissioner.

Conclusion

The surest path to “disaster” in this proceeding is for the FCC to take the incentives out of the incentive auction. The Bureau’s insistence on pushing an approach that most broadcasters, wireless providers, and equipment manufacturers don’t support is more likely to deter participation in the auction than incent it. It is the industry – not the Wireless Bureau – that ultimately must agree to risk its capital in the auction and deploy new wireless infrastructure. If the Wireless Bureau’s preferred approach wins and, as a result, the industry declines to participate in the auction, everyone loses.

My Filing to the FTC in its ‘Internet of Things’ Proceeding

In mid-April, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) requested comments regarding “the consumer privacy and security issues posed by the growing connectivity of consumer devices, such as cars, appliances, and medical devices” or the so-called “Internet of Things.” This is in anticipation of a November 21 public workshop that the FTC will be hosting on the same issue.

These issues are finally starting to catch the attention of the public and policymakers alike with the rise of wearable computing, remote home automation and monitoring technologies, smart grids, autonomous vehicles and intelligent traffic systems, and so on. The Internet of Things represents the next great wave of Internet innovation, but it also represents the next great battleground in the field of Internet policy.

I filed comments with the FTC today in this proceeding and made a few simple points about why they should proceed cautiously here. A summary of my filing follows.

Avoiding a Precautionary Principle for the Internet of Things

First, while it is unclear where the FTC is heading with this proceeding—or for that matter, whether this even a formal proceeding at all—the danger exists that it represents the beginning of a regulatory regime for a new set of information technologies that are still in their infancy. Fearing hypothetical worst-case scenarios about the misuse of some IoT technologies, some policy activists and policymakers could seek to curb or control their development.

Policymakers should avoid acting on those impulses. Simply put, the Internet of Things—like the Internet itself—should not be subjected to a precautionary principle, which would impose preemptive, prophylactic restrictions on this rapidly evolving sector to guard against every theoretical harm that could develop. Preemptive restrictions on the development of the Internet of Things could retard technological innovation and limit the benefits that flow to consumers.

In other words, to the maximum extent possible, the default position toward new forms of technological innovation such as the Internet of Things should be innovation allowed, or what Paul Ohm, who recently joined the FTC as a Senior Policy Advisor, refers to as an “anti-Precautionary Principle.” This policy norm is better captured in the well-known Internet ideal of “permissionless innovation,” or the general freedom to experiment and learn through trial-and-error experimentation. As I noted in a recent essay here:

Wisdom is born of experience, including experiences involving risk and the possibility of mistakes and accidents. Patience and openness to permissionless innovation represent the wise disposition toward new technologies not only because it provides breathing space for future entrepreneurialism, but also because it provides an opportunity to observe both the evolution of societal attitudes toward new technologies and how citizens adapt to them.

Adaptation Is Not Just Possible but Likely

Which leads to the next major point I make in my filing: Humans adapt! The more I study the history of various technological innovations the more I find the same story unfolding: again and again society has found ways to adapt to new technological changes by employing a variety of coping mechanisms or new social norms. In fact, we see a common cycle of initial resistance, gradual adaptation, and then eventual assimilation of new technologies into society. (I previously outlined this cycle in my law review article, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle.”)

I offer several specific examples of this process in action—from the rise of the telephone and the camera to RFID and Gmail. I argue that these examples should give us hope that we will also find ways of adapting to the challenges presented by the rise of the Internet of Things.

Norms Evolve and “Regulate”

Third, my filing discusses how societal norms evolve in response to new technologies and even come to “regulate” acceptable use of those technologies. Law tends to regulate in sweeping ways and then get locked in. Social norms and technological etiquette, by contrast, flexibly evolve in unique ways over time.

Some of these norms or social constraints are more “top-down” and formal in nature in that they are imposed by establishments or organizations in the form of restrictions on technologies. In other cases, these norms or social constraints are purely bottom-up and group-driven. I offer examples of both types of norms in my filing.

Other Remedies Exist or Will Develop as Needed

Finally, I argue in my filing that policymakers should exercise restraint and humility in the face of uncertain change and address harms that develop—if they do at all—after careful benefit-cost analysis of various remedies. I note that many federal and state laws already exist that could address perceived harms associated with these technologies.

And let’s be clear: some misuses and harms will develop, just as they have for every other information technology ever invented. But, to reiterate, we have generally not preemptive applied precautionary regulation to each and every new information technology based on the potential threat of some misuses developing. Instead, we have allowed experimentation and innovation to take place largely unimpeded and then relied on a combination of education, user empowerment, various social norms and coping mechanisms, and then targeted laws as needed after serious harms were demonstrated. That same approach should govern the Internet of Things.

If we succumb to the opposite impulse and apply a “Mother May I?” permissioned approach to the Internet of Things—with innovation only being allowed after regulators deem those technologies “safe” or “acceptable”—then we risk derailing the next great wave of Internet-based innovation. The implications for America’s consumers and our global competitiveness could not be more profound. The result will be fewer services, lower quality goods, higher prices, diminished economic growth, and a decline in the overall standard of living.

Hopefully the FTC is not going down that path with this proceeding or its forthcoming workshop on the Internet of Things. But stay tuned. This set of issues is expanding rapidly and promises to produce heated privacy, security, and safety debates for many years to come.

Please read my filing for more details. I’ve also embedded it below.

Comments of Adam Thierer Mercatus Center in FTC Internet of Things Proceeding (June 2013)

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower