Adam Thierer's Blog, page 60

July 29, 2013

Gary Becker on patent terms and scope

Nobel laureate Gary Becker and I are on the same page. He says patent terms should be short:

Major reforms to reduce these unproductive opportunities would include lowering typical patent length and the scope of innovations that are eligible for patents. The current patent length of 20 years (longer for drug companies) from the date of filing for a patent can be cut in half without greatly discouraging innovation. One obvious advantage of cutting patent length in half is that the economic cost from the temporary monopoly power given to patent holders would be made much more temporary. In addition, a shorter patent length gives patent holders less of an effective head start in developing follow on patents that can greatly extend the effective length of an original patent.

More importantly, he says we should carve out particularly troublesome areas, like software, from the patent system:

In narrowing the type of innovations that are patentable, one can start by eliminating the patenting of software. Disputes over software patents are among the most common, expensive, and counterproductive. Their exclusion from the patent system would discourage some software innovations, but the saving from litigation costs over disputed patent rights would more than compensate the economy for that cost. Moreover, some software innovations would be encouraged because the inability to patent software will eliminate uncertainty over whether someone else with a similar patent will sue and do battle in the courts.

[...]

In addition to eliminating patents on software, no patents should be allowed on DNA, such as identification of genes that appear to cause particular diseases. Instead, they should be treated as other scientific discoveries, and be in the public domain. The Supreme Court recently considered a dispute over whether the genes that cause BRCA1 and BRCA2 deviations and greatly raises the risk of breast cancer is patentable. Their ruling banned patenting of human DNA, and this is an important step in the right direction.

Other categories of innovations should also be excluded from the patent system. Essentially, patents should be considered a last resort, not a first resort, to be used only when market-based methods of encouraging innovations are likely to be insufficient, and when litigation costs will be manageable. With such a “minimalist” patent system, patent intermediaries would have a legitimate and possibly important role to play in helping innovators get and protect their patent rights.

It’s good to see a consensus for major reform developing among economists. I hope that legal scholars and policymakers will start to listen.

July 24, 2013

video: Mediaite’s “Privacy, Security and The Digital Age” Event

It was my pleasure last night to take part in an hour-long conversation on “Privacy, Security, and the Digital Age,” which was co-sponsored by Mediaite and the Koch Institute. The discussion focused on a wide range of issues related to government surveillance powers, Big Data, and the future of privacy. It opened with dueling remarks from former U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. John Bolton and Ben Wizner of the ACLU. You can view their respective remarks here.

I then sat on a panel that included Atlantic Media CTO Tom Cochrane and Michael R. Nelson, who is affiliated with with Bloomberg Government and Georgetown University. The entire session was expertly moderated by Andrew Kirell of Mediaite. He did an amazing job facilitating the discussion. Anyway, the videos for my panel are below, split into two parts. My comments focused heavily on the importance of separating the government uses of data from private sector uses and explaining the need to create a high and tight firewall between State and Industry when it comes to information sharing. I also argued that we will never get a handle on government-related privacy concerns until we get control of the scope of government power. I used the example of the drug war and our government’s constantly-expanding militaristic activities both abroad and here at home. So long as government is expanding without any rational, constitutional constraint, we are going to have serious surveillance and privacy problems. (See this essay, “It’s About Power, not Privacy,” by my colleague Eli Dourado for more on that theme.)

July 23, 2013

Jane Bambauer on whether data is speech

Jane Yakowitz Bambauer, associate professor of law at the University of Arizona, discusses her forthcoming paper in the Stanford Law Review titled Is Data Speech? How do we define “data” and can it be protected in the same way as free speech? She examines current privacy laws and regulations as they pertain to data creation and collection, including whether collecting data should be protected under the First Amendment.

Related Links

Jane Bambauer Faculty Profile, University of Arizona

Is Data Speech?, Bambauer, Stanford Law Review, Forthcoming

Tragedy of the Data Commons, Bambauer, Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, 2011

Why Progress Cannot Be Planned, or Even Forecast

Few modern intellectuals gave more serious thought to forecasting the future than Herman Kahn. He wrote several books and essays imagining what the future might look like. But he was also a profoundly humble man who understood the limits of forecasting the future. On that point, I am reminded of my favorite Herman Kahn quote:

Few modern intellectuals gave more serious thought to forecasting the future than Herman Kahn. He wrote several books and essays imagining what the future might look like. But he was also a profoundly humble man who understood the limits of forecasting the future. On that point, I am reminded of my favorite Herman Kahn quote:

History is likely to write scenarios that most observers would find implausible not only prospectively but sometimes, even in retrospect. Many sequences of events seem plausible now only because they have actually occurred; a man who knew no history might not believe any. Future events may not be drawn from the restricted list of those we have learned are possible; we should expect to go on being surprised.[1]

I have always loved that phrase, “a man who knew no history might not believe any.” Indeed, sometimes the truth (how history actually unfolds) really is stranger than fiction (or the hypothetical forecasts that came before it.)

This insight has profound ramifications for public policy and efforts to “plan progress,” something that typically ends badly. No two scholars nailed that point better in their work than Karl Popper and F.A. Hayek, two of the preeminent philosophers of science and politics of the 20th century. Popper cogently argued that the problem with “the Utopian programme” is that “we do not possess the experimental knowledge needed for such an undertaking.”[2] “Progress by its very nature cannot be planned,” Hayek taught us, and the wiser man “is very much aware that we do not know all the answers and that he is not sure that the answers he has are certainly the right ones or even that we can find all the answers.”[3] One hundred years prior to Hayek making that insight, social philosopher Herbert Spencer explained how humans would only be truly wise once they fathomed the limits of their own knowledge:

In all directions his investigations eventually bring him face to face with the unknowable; and he ever more clearly perceives it to be the unknowable. He learns at once the greatness and the littleness of human intellect—its power in dealing with all that comes within the range of experience; its impotence in dealing with all that transcends experience. He feels more vividly than any others can feel, the utter incomprehensibleness of the simplest fact, considered in itself. He alone truly sees that absolute knowledge is impossible. He alone knows that under all things there lies an impenetrable mystery.[4]

Unfortunately, most humans suffer from what Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls “epistemic ignorance” or hubris concerning the limits of our knowledge. “We are demonstrably arrogant about what we think we know,” he says.[5] “We overestimate what we know, and underestimate uncertainty.”[6] “There are no crystal balls, and no style of thinking, no technique, no model will ever eliminate uncertainty,” argues Dan Gardner, author of Future Babble: Why Expert Predictions Are Next to Worthless. “The future will forever be shrouded in darkness. Only if we accept and embrace this fundamental fact can we hope to be prepared for the inevitable surprises that lie ahead,” Gardner notes.[7]

This is why attempts to forecast the future so often end in folly. The great Austrian school economist Israel Kirzner spoke of “the shortsightedness of those who, not recognizing the open-ended character of entrepreneurial discovery, repeatedly fall into the trap of forecasting the future against the background of today’s expectations rather than against the unknowable background of tomorrow’s discoveries.”[8] This is especially true as it pertains to technological change and change in information markets. “Anyone who predicts the technological future is sure soon to seem foolish,” noted technology scholar George Gilder. “It springs from human creativity and thus inevitably consists of surprise.”[9]

Knowledge of history and historical trends can help inform our decisions and predictions, yet they are insufficient to accurately forecast all that may come our way. “The past seldom obliges by revealing to us when wildness will break out in the future,” observes Peter L. Bernstein, author of Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk.[10]

We can relate these lessons to Internet policy and digital economics. A largely unfettered cyberspace has left digital denizens better off in terms of the information they can access as well as the goods and services from which they can choose. In true Schumpeterian fashion, “information empires” have come and gone in increasingly rapid progression.[11] There are countless “tech titans” that, for a time, seemed to rule their respective sectors only to experience a precipitous fall.[12] Indeed, if you blink your eyes in the information age, you can miss revolutions.[13]

“The challenge of disruptive innovation,” observes technology lawyer Glenn Manishin, is that “it forces market participants to rethink their premises and reimagine the business they are in. Those who get it wrong will be lost in the dustbin (or buggy whip rack) of history. Those who get it right typically enjoy a window of success until the next inflection point arrives.”[14] And the cycle Manishin describes just keeps repeating faster and faster throughout modern information sectors.

This explain why, just as planning and forecasting often fail in a macro sense, they also fail in the micro sense as industries and analysts repeatedly fail to accurately identify future trends and marketplace developments. “Markets that don’t exist can’t be analyzed,” observes Clayton M. Christensen, author of The Innovator’s Dilemma. “In dealing with disruptive technologies leading to new markets,” he finds, “researchers and business planners have consistently dismal records.”[15] Simply put, as Yogi Berra once famously quipped: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

The ramifications for public policy are clear. Patience and humility are key virtues since, as economist Daniel F. Spulber correctly writes, “Governments are notoriously inept at picking technology winners or steering fast-moving markets in superior directions. Understanding technology requires extensive scientific and technical knowledge. Government agencies cannot expect to replicate or improve upon private sector knowledge. Technological innovation is uncertain by its very nature because it is based on scientific discoveries. The benefits of new technologies and the returns to commercial development also are uncertain.”[16]

Policymakers would be wise to heed all this advice before trying to “plan progress,” especially in highly-dynamic, rapidly-evolving technology sectors. As the old saying goes, the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry.

[1] Herman Kahn and Anthony Wiener, The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-three Years (New York: Macmillan, 1967), 264-5.

[2] Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, (London: Routledge, 1957, 2002), 77.

[3] Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty, 41, 406. Similarly, political scientist Vincent Ostrom has observed that, “Human beings face difficulties in dealing with a world that is open to potentials for choice but always accompanied by basic limits. There is much about the mystery of being that cannot be known by mortal human beings.” Vincent Ostrom, The Meaning of Democracy and the Vulnerability of Democracies (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1997), 29-30.

[4] Herbert Spencer, “Progress: Its Law and Cause,” (April 1857), republished in Essays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative (London: Williams and Norgate, 1891), available at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?...

[5] Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House, 2007), 138.

[6] Id., 140. Similarly, Cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman speaks of, “Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.” Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011) 201.

[7] Dan Gardner, Future Babble: Why Expert Predictions Are Next to Worthless, and You Can Do Better (New York: Dutton, 2011), 16-17.

[8] Israel Kirzner, Discovery and the Capitalist Process (University of Chicago Press, 1985), at xi.

[9] George Gilder, Wealth & Poverty, 101.

[10] Peter L. Bernstein, Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996) 334.

[11] “Each era of computing seems to run for about a decade of total dominance by a given platform. Mainframes (1960-1970), minicomputers (1970-1980), character-based PCs (1980-1990), graphical PCs (1990-2000), notebooks (2000-2010), smart phones and tablets (2010-2020?). We could look at this in different ways like how these devices are connected but I don’t think it would make a huge difference. Now look at the dominant players in each succession – IBM (1960-1985), DEC (1965-1980), Microsoft (1987-2003), Google (2000-2010), Facebook (2007-?). That’s 25 years, 15 years, 15 years, 10 years, and how long will Facebook reign supreme? Not 15 years and I don’t think even 10. I give Facebook seven years or until 2014 to peak.” Robert Cringely, “The Decline and Fall of Facebook,” I, Cringely, July 20, 2011, http://www.cringely.com/2011/07/the-d....

[12] Adam Thierer, “Of ‘Tech Titans’ and Schumpeter’s Vision,” Forbes, August 22, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/adamthier....

[13] Megan Garber, “The Internet at the Dawn of Facebook,” The Atlantic, May 17, 2012, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology....

[14] Glenn Manishin, “Of Buggy Whips, Telephones and Disruption,” DisCo, June 25, 2012, http://www.project-disco.org/competit....

[15] Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma (New York: Harper Business Essentials, 1997), xxv.

[16] Daniel F. Spulber, “Unlocking Technology: Antitrust and Innovation,” 4(4), Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 915–96, 965. (May 2008).

July 21, 2013

video: Education Beats Silver-Bullet Solutions for Privacy & Online Safety

Last month, it was my great pleasure to serve as a “provocateur” at the IAPP’s (Int’l Assoc. of Privacy Professionals) annual “Navigate” conference. The event brought together a diverse audience and set of speakers from across the globe to discuss how to deal with the various privacy concerns associated with current and emerging technologies.

My remarks focused on a theme I have developed here for years: There are no simple, silver-bullet solutions to complex problems such as online safety, security, and privacy. Instead, only a “layered” approach incorporating many different solutions–education, media literacy, digital citizenship, evolving society norms, self-regulation, and targeted enforcement of existing legal standards–can really help us solve these problems. Even then, new challenges will present themselves as technology continues to evolve and evade traditional controls, solutions, or norms. It’s a never-ending game, and that’s why education must be our first-order solution. It better prepares us for an uncertain future. (I explained this approach in far more detail in this law review article.)

Anyway, if you’re interested in an 11-minute video of me saying all that, here ya go. Also, down below I have listed several of the recent essays, papers, and law review articles I have done on this issue.

Some of My Recent Essays on Privacy & Data Collection

Testimony / Filings:

Senate Testimony on Privacy, Data Collection & Do Not Track – April 24, 2013

Comments of the Mercatus Center to the FTC in Privacy & Security Implications of the Internet of Things

Mercatus filing to FAA on commercial domestic drones

Law Review Articles:

“The Pursuit of Privacy in a World Where Information Control is Failing” – Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy

“Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle” – Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology

“A Framework for Benefit-Cost Analysis in Digital Privacy Debates” – (forthcoming, George Mason University Law Review)

Blog posts:

A Better, Simpler Narrative for U.S. Privacy Policy – March 19, 2013

On the Pursuit of Happiness… and Privacy – March 31, 2013

Let’s Not Place All Our Eggs in the Do Not Track Basket (IAPP Privacy perspectives blog)

Can We Adapt to the Internet of Things? – June 19, 2013 (IAPP Privacy perspectives blog)

Isn’t “Do Not Track” Just a “Broadcast Flag” Mandate for Privacy? – Feb. 20, 2011

Two Paradoxes of Privacy Regulation – Aug. 25, 2010

Privacy as an Information Control Regime: The Challenges Ahead – Nov. 13, 2010

When It Comes to Information Control, Everybody Has a Pet Issue & Everyone Will Be Disappointed – Apr. 29, 2011

Lessons from the Gmail Privacy Scare of 2004 – March 25, 2011

Who Really Believes in “Permissionless Innovation”? – March 4, 2013

The Problem of Proportionality in Debates about Online Privacy and Child Safety – Nov. 28, 2009

Obama Admin’s “Let’s-Be-Europe” Approach to Privacy Will Undermine U.S. Competitiveness– Jan. 5, 2011

July 19, 2013

PPI: Net neutrality problems “simply do not exist”

The Progressive Policy Institute has released a new and remarkable broadband report. In it, PPI explicitly distances itself from the Crawford/Wu wing of the left-of-center telecommunications conversation. A money quote from the introduction:

What should the progressive agenda be? Are our choices either to embrace this aggressive regulatory agenda or to accede to conservative laissez-faire? This essay argues that there is a third, and far more promising, option for such a progressive broadband policy agenda. It balances respect for the private investment that has built the nation’s broadband infrastructure with the need to realize the Internet’s full promise as a form of social infrastructure and a tool for individual empowerment. It turns away from problems we may reasonably fear but that simply do not exist—most importantly, the idea that the provision of broadband services is dominated by an anti-competitive “duopoly” that stifles the broad dissemination of content.

On “cage match” competition in the telecom sector:

So perhaps the greatest paradox inherent in “cage match” competition is that, while advocates champion more intrusive regulation, the signal providers are in the fight of their business lives. The benefits of their innovation and investment are being appropriated by the devices and services that use the signal; their stock values and capitalizations are listless compared to the companies that make devices and applications; they have made commitments in the tens of billions to build infrastructure that cannot be reversed. And they are trapped in a vicious circle: they innovate to improve signal quality and availability, these innovations make possible new devices, applications, and services that capture consumer allegiance, these other aspects of the broadband experience appropriate value and make signal more commodity-like in the eyes of consumers, which forces the providers to further improve their product, perpetuating the cycle. They are the economy’s front line for investing in and innovating for our broadband infrastructure, and perhaps they benefit from that investment and innovation the least.

From the section entitled “Neutrality,” “Unbundling,” and other progressive policy failures:

The weight of the evidence, therefore, suggests the activist agenda leads progressives to a dead end. It addresses a problem that doesn’t exist—the absence of competition in broadband—and compromises another and more important objective—investment in broadband leading to ubiquitous broadband access. In reality, access providers have made massive investments in high-fixed cost broadband wired and wireless capacity that they can only justify by competing for market share and that are continually improving. The case that they are suppressing or might suppress content—either editorially or competitively—is virtually nonexistent.

This analysis is spot on. While I don’t agree with every policy proposal in the report (though I do agree with some, such as liberating spectrum from the broadcasters and DoD), PPI deserves a lot of credit for its excellent study of the state of telecommunications competition.

July 18, 2013

Aaron’s Law: What’s Next for CFAA Reform?

The suicide of Aaron Swartz earlier this year has sparked a national debate about reforming the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). Most notably, in June, Reps. Zoe Lofgren and Jim Sensenbrenner joined Sen. Ron Wyden to introduce Aaron’s Law, which aims to rein in the excesses of the federal computer fraud law and ensure it targets real criminals, rather than researchers or tinkerers.

Would this bipartisan reform go far enough — or too far? Would Aaron’s Law preserve the government’s ability to prosecute harmful hacking? What can activists do to promote CFAA reform in Congress?

These are some of the questions that will be explored in a panel discussion hosted by TechFreedom and the Electronic Frontier Foundation at CNET’s San Francisco Headquarters on July 22. RSVP here.

You can join the conversation on Twitter on the #CFAA hashtag.

When:

Monday, July 22, 2013

Drinks served at 6:00pm

Panel 6:30pm – 7:30pm PDT

Where:

CNET

235 2nd Street

San Francisco, CA

Questions?

Email contact@techfreedom.org.

July 16, 2013

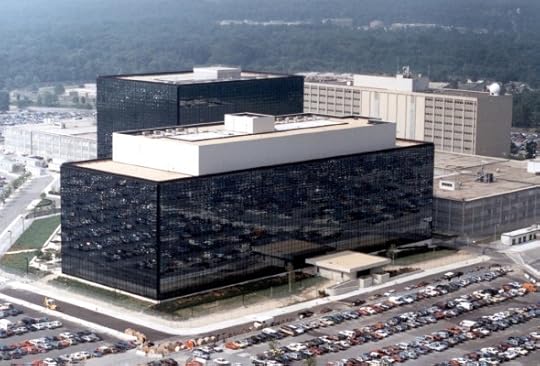

Why the Lawsuit Challenging NSA Surveillance is Crucial to Internet Freedom

In June, The Guardian ran a groundbreaking story that divulged a top secret court order forcing Verizon to hand over to the National Security Agency (NSA) all of its subscribers’ telephony metadata—including the phone numbers of both parties to any call involving a person in the United States and the time and duration of each call—on a daily basis. Although media outlets have published several articles in recent years disclosing various aspects the NSA’s domestic surveillance, the leaked court order obtained by The Guardian revealed hard evidence that NSA snooping goes far beyond suspected terrorists and foreign intelligence agents—instead, the agency routinely and indiscriminately targets private information about all Americans who use a major U.S. phone company.

It was only a matter of time before the NSA’s surveillance program—which is purportedly authorized by Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act (50 U.S.C. § 1861)—faced a challenge in federal court. The Electronic Privacy Information Center fired the first salvo on July 8, when the group filed a petition urging the U.S. Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus nullifying the court orders authorizing the NSA to coerce customer data from phone companies. But as Tim Lee of The Washington Post pointed out in a recent essay, the nation’s highest Court has never before reviewed a decision of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) court, which is responsible for issuing the top secret court order authorizing the NSA’s surveillance program.

Today, another crucial lawsuit challenging the NSA’s domestic surveillance program was brought by a diverse coalition of nineteen public interest groups, religious organizations, and other associations. The coalition, represented by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, includes TechFreedom, Human Rights Watch, Greenpeace, the Bill of Rights Defense Committee, among many other groups. The lawsuit, brought in the U.S. district court in northern California, argues that the NSA’s program—aptly described as the “Assocational Tracking Program” in the complaint—violates the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution, along with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

In a statement today, TechFreedom President Berin Szoka described the lawsuit as follows:

We’re standing up for the constitutional rights of all Americans: The First Amendment protects our right to communicate and associate privately. The Fourth Amendment protects us against unreasonable searches and seizures by barring the kind of general warrant that compelled U.S. telephone carriers to turn over potentially sensitive information about Americans’ telephone call records. The secretive processes of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court violate the most fundamental guarantees of the Fifth Amendment to due process, as well as basic principles of the rule of law.

Amen. Our founding fathers wrote the 4th Amendment to prevent precisely this kind of secretive sifting through citizens’ private records. As the recent scandal involving the IRS targeting tea party groups illustrates, America’s founders knew all too well that government would always be tempted to use perfectly innocuous information about Americans’ beliefs and behaviors to harass them and treat them unfairly. This is why our Constitution and federal laws restrict the government’s power to collect private information about its citizens. These rules exist not so criminals can conceal their behavior, but to protect you and me. And when the government violates those rules, it is acting criminally.

Think you’re off the the hook because you communicate primarily using the Internet, rather than via phone? Think again. We know that far more extensive collection of Americans’ data has occurred under the same authority—50 U.S.C. § 1861—upon which the Associational Tracking Program is based.

According to a leaked 2009 NSA Inspector General report, NSA in 2001 began collecting “bulk Internet metadata” from at least three unknown large Internet companies. A 2007 DOJ memo regarding “supplemental procedures” for NSA data collection authorized the agency to collect Internet metadata—including the “email address[es]” of each sender and recipient of an email, along with their “IP address”—for “persons in the United States.” The memo further states that “NSA has in its database a large amount of communications metadata associated with persons in the United States.” However, a spokesman for James Clapper, the Director of National Intelligence has claimed this Internet metadata collection program was “discontinued in 2011 for operational and resource reasons.” Who knows if this is accurate, or another “clearly erroneous” statement that will be corrected in future months or years in a statement resembling the letter James Clapper sent to the Senate Intelligence Committee a few weeks ago.

Yet if the NSA’s Associational Tracking Program is lawful, the Internet metadata program is probably legal as well. If courts fail to halt the NSA’s program as it currently exists, and clarify what Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act really means, nothing is stopping the government from resuming its acquisition of Internet metadata—that is, if it hasn’t already done so.

These suspicionless mass surveillance programs don’t just endanger our constitutional rights. They also threaten free enterprise in the information economy. Increasingly, we transact, communicate, innovate, and create in the digital realm, where information itself is a form of wealth. But if Americans reasonably perceive their digital communications—including metadata—are subject to warrantless governmental interception, some who might use cloud services will choose not to do so. Not only would this distort the future of Internet commerce, it might cause cloud computing servers and businesses to move or be formed abroad—which, ironically, could deny U.S. law enforcement access to this cloud data.

If the information age is to realize its full potential, providers of electronic communications services must be free to make credible assurances to their users about when private information will be shared, and with whom. Users need to know that the data they relinquish is confined to agreed-upon business, transactional, and record-keeping purposes—not automatically stored in a government datacenter.

The GAC officially objects to .amazon

ICANN is meeting in Durban, South Africa this week, and this morning, its Governmental Advisory Committee, which goes by the delightfully onomatopoetic acronym GAC, announced its official objection to the .amazon top-level domain name, which was set to go to Amazon, the online purveyor of books and everything else. Domain Incite reports:

The objection came at the behest of Brazil and other Latin American countries that claim rights to Amazon as a geographic term, and follows failed attempts by Amazon to reach agreement.

Brazil was able to achieve consensus in the GAC because the United States, which refused to agree to the objection three months ago in Beijing, had decided to keep mum this time around.

The objection will be forwarded to the ICANN board in the GAC’s Durban communique later in the week, after which the board will have a presumption that the .amazon application should be rejected.

The board could overrule the GAC, but it seems unlikely.

This is a loss for anything resembling rule of law on the Internet. There are rules for applying for new generic TLDs, and the rules specifically say which geographic terms are protected. Basically, anything on this list, known as ISO 3166-1 is verboten. But “Amazon” is not on that list, nor is “Patagonia;” .patagonia was recently withdrawn. Amazon and Patagonia followed the rules and won their respective gTLDs fair and square.

The US’s decision to appease other countries by remaining silent is a mistake. The idea of diplomacy is to get countries to like you so that you can get what you want on policy, not to give up what is right on policy so that other countries will like you. I agree with Milton Mueller, whose bottom line is:

What is at stake here is far more important than the interests of Amazon, Inc. and Patagonia, Inc. What’s really at stake is whether the Internet is free of pointless constraints and petty political objections; whether governments can abuse the ICANN process to create rights and powers for themselves without any international legislative process subject to democratic and judicial checks and balances; whether the alternative governance model that ICANN was supposed to represent is real; whether domain name policy is made through an open, bottom-up consensus or top-down by states; whether the use of words or names on the Internet is subject to arbitrary objections from politicians globalizing their local prejudices.

Book Review: Ronald Deibert’s “Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace”

Ronald J. Deibert is the director of The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and the author of an important new book, Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace, an in-depth look at the growing insecurity of the Internet. Specifically, Deibert’s book is a meticulous examination of the “malicious threats that are growing from the inside out” and which “threaten to destroy the fragile ecosystem we have come to take for granted.” (p. 14) It is also a remarkably timely book in light of the recent revelations about NSA surveillance and how it is being facilitated with the assistance of various tech and telecom giants.

Ronald J. Deibert is the director of The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and the author of an important new book, Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace, an in-depth look at the growing insecurity of the Internet. Specifically, Deibert’s book is a meticulous examination of the “malicious threats that are growing from the inside out” and which “threaten to destroy the fragile ecosystem we have come to take for granted.” (p. 14) It is also a remarkably timely book in light of the recent revelations about NSA surveillance and how it is being facilitated with the assistance of various tech and telecom giants.

The clear and colloquial tone that Deibert employs in the text helps make arcane Internet security issues interesting and accessible. Indeed, some chapters of the book almost feel like they were pulled from the pages of techno-thriller, complete with villainous characters, unexpected plot twists, and shocking conclusions. “Cyber crime has become one of the world’s largest growth businesses,” Deibert notes (p. 144) and his chapters focus on many prominent recent examples, including cyber-crime syndicates like Koobface, government cyber-spying schemes like GhostNet, state-sanctioned sabotage like Stuxnet, and the vexing issue of zero-day exploit sales.

Deibert is uniquely qualified to narrate this tale not just because he is a gifted story-teller but also because he has had a front row seat in the unfolding play that we might refer to as “How Cyberspace Grew Less Secure.” Indeed, he and his colleagues at The Citizen Lab have occasionally been major players in this drama as they have researched and uncovered various online vulnerabilities affecting millions of people across the globe. (I have previously reviewed and showered praise on a couple important books that Deibert co-edited with scholars from The Citizen Lab and Harvard’s Berkman Center, including: Access Controlled: The Shaping of Power, Rights, and Rule in Cyberspace and Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering. They are truly outstanding resources worthy of your attention.)

Black Code’s Many Meanings

So, what is “black code” and why should we be worried about it? Deibert uses the term as a metaphor for many closely related concerns. Most generally it includes “that which is hidden, obscured from the view of the average Internet user.” (p. 6) More concretely, it refers to “the criminal forces that are increasingly insinuating themselves into cyberspace, gradually subverting it from the inside out.” (p. 7) “Those who take advantage of the Internet’s vulnerabilities today are not just juvenile pranksters or frat house brats,” Deibert notes, “they are organized criminal groups, armed militants, and nation states.” (p. 7-8) Which leads to the final way Deibert uses the term “black code.” It also, he says, “refers to the growing influence of national security agencies, and the expanding network of contractors and companies with whom they work.” (p. 8)

Deibert is worried about the way these forces and factors are working together to undermine online stability and security, and even delegitimize liberal democracy itself. His thesis is probably most succinctly captured in this passage from Chapter 7:

We live in an era of unprecedented access to information, and many political parties campaign on platforms of transparency and openness. And yet, at the same time, we are gradually shifting the policing of cyberspace to a dark world largely free from public accountability and independent oversight. In entrusting more and more information to third parties, we are signing away legal protections that should be guaranteed by those who have our data. Perversely, in liberal democratic countries we are lowering the standards around basic rights to privacy just as the center of cyberspace gravity is shifting to less democratic parts of the world. (p. 130-1)

What Deibert is grappling with in this book is the same fundamental problem that has long plagued the Internet: How do you preserve the benefits associated with the most open and interconnected “network of networks” the world has ever known while also remedying the various vulnerabilities and pathologies created by that same openness and interconnectedness? Deibert acknowledges this problem, noting:

Ever since the Internet emerged from the world of academia into the world of the rest of us, its growth trajectory has been shadowed by a grey economy that thrives on opportunities for enrichment made possible by an open, globally connected infrastructure. (p. 141)

The Paradox of the Net’s Open, Interconnected Nature

Again, paradoxically, this inherent instability and vulnerability is due precisely to the Net’s open and globally interconnected nature. And many governments are looking to exploit that fact. “These unfortunate by-products of an open, dynamic network are exacerbated by increasing assertions of state power,” Deibert notes. (p. 233)

More generally, this uncomfortable fact—that the Net’s open, interconnected nature leads to both enormous benefits as well as huge vulnerabilities—isn’t just true for criminal online activity or the cyber-espionage activities that various nation-states are pursuing today. It is equally true for everything online today. There is a sort of yin and the yang to the Net that is simply undeniable and completely unavoidable. For one issue after another we find that the Net’s greatest blessing—its open, interconnected nature—is also its greatest curse.

For example, as I noted here recently in my review of Abraham H. Foxman and Christopher Wolf ‘s new book, Viral Hate: Containing Its Spread on the Internet, the open and interconnected Internet gives us “the most widely accessible, unrestricted communications platform the world has ever known” but also means we have to tolerate a great many imbeciles “who use it to spew insulting, vile, and hateful comments.” The same is true for other types of online speech and content: You have access to an abundance of informational riches, but there’s also no avoiding all the garbage out there now, too.

Similarly, as I noted in my essay, “Privacy as an Information Control Regime: The Challenges Ahead,” the open and interconnected Internet has given us historically unparalleled platforms for social interaction and commerce. But that same openness and interconnectedness has left us with a world of hyper-exposure and a variety of privacy and surveillance threats—not just from governments and large corporations, but also from each other.

And then there’s the never-ending story of digital copyright. On one hand, the open and globally interconnected network or networks has provided us with an amazing platform for sharing knowledge, art, and expression. On the other hand, as I noted in this essay on “The Twilight of Copyright,” creators of expressive works have less security than ever before in terms of how they can control and monetize their artistic and scientific inventions.

I could go on and on—as I did in my essays on “Copyright, Privacy, Property Rights & Information Control: Common Themes, Common Challenges” and “When It Comes to Information Control, Everybody Has a Pet Issue & Everyone Will Be Disappointed”—but the moral of the story is pretty clear: The Internet giveth and the Internet taketh away. Openness and interconnectedness offer us enormous benefits but also force us to confront major risks as the price of admission to this wonderful network.

Will the Whole System Collapse?

The uncomfortable question that Deibert’s book tees up for discussion is: When will this balance get completely out of whack in terms of online security? Or, has it already? In some portions of the text, he hints that may already be the case. Consider this passage in Chapter 11 in which Deibert discusses whether the Chicken Little-ism of digital security worry-warts like Eugene Kaspersky and Richard Clarke is warranted:

Eugene Kaspersky, Richard Clarke, and others may sound like broken records or self-serving fear mongers, but there is no denying the evolving cyberspace ecosystem around us: we are building a digital edifice for the entire planet, and it sits above us like a house of cards. We are wrapping ourselves in expanding layers of digital instructions, protocols, and authentication mechanisms, some them open scrutinized, and regulated, but many closed, amorphous, and poised for abuse, buried in the black arts of espionage, intelligence gathering, and cyber and military affairs. Is it only a matter of time before the whole system collapses? (p. 186)

That sounds horrific, but is it really the case that the entire system really about to collapse? And, if so, what are we going to do about it?

This raises a small problem with Deibert’s book. He does such a nice job itemizing and describing these security vulnerabilities that by the time the reader wades through 230 pages and nears the end of the book, they are left in a highly demoralized state, searching for some hope and a concrete set of practical solutions. Unfortunately, they won’t find an abundance of either in Deibert’s brief closing chapter, “Toward Distributed Security and Stewardship in Cyberspace.”

Don’t get me wrong; I agree with the general thrust of Deibert’s framework, which I describe below. The problem is that it is highly aspirational in nature and lacks specifics. Perhaps that is simply because there are no easy answers here. Digital security is damn hard and, as with most other online pathologies out there, no silver-bullet solutions exist.

Deibert notes that some government officials will seek to exploit those vulnerabilities—many of which they created themselves—to expand their authority over the Internet. “Faced with mounting problems and pressures to do something, too many policy-makers are tempted by extreme solutions,” he notes. (p. 234) He worries about “a movement towards clamp down” that would be “antithetical to the principles of liberal democratic government” by undermining checks and balances and accountability. (p. 235) In turn, this will undermine the “mixed common-pool resource” that is the current Internet.

Deibert’s alternative cyber security strategy to counter the push to “clamp down” is based on three interrelated notions or components:

Principles of restraint or “mutual restraint”: “Securing cyberspace requires a reinforcement, rather than a relaxation, of restraint on power, including checks and balances on governments, law enforcement, intelligence agencies, and on the private sector,” he argues. (p. 239)

“Distributed security”: “The Internet functions precisely because of the absence of centralized control, because of thousands of loosely coordinated monitoring mechanisms,” Deibert notes. “While these decentralized mechanisms are not perfect and can occasionally fail, they form the basis of a coherent distributed security strategy. Bottom-up, ‘grassroots’ solutions to the Internet’s security problems are consistent with principles of openness, avoid heavy-handedness, and provide checks and balances against the concentrations of power,” he observes. (p. 240)

“Stewardship” which Deibert defines as “an ethic of responsible behavior in regard to shared resources” and which, he argues, “would moderate the dangerously escalating exercise of state power in cyberspace by defining limits and setting thresholds of accountability and mutual restraint.” (p. 243)

Again, as an aspirational vision statement this all generally sounds fairly sensible, but the details are lacking. I think Deibert would have been wise to spend a bit more time developing this alternative “bottom-up” vision of how online security should work and bolstering it with case studies.

Digital Security without Top-Down Controls

Luckily, as my Mercatus Center colleague Eli Dourado noted in an important June 2012 white paper, distributed security and stewardship strategies are already working reasonably well today. Dourado’s paper, “Internet Security Without Law: How Service Providers Create Order Online,” documented the many informal institutions that enforce network security norms on the Internet and shows how cooperation among a remarkably varied set of actors improves online security without extensive regulation or punishing legal liability. “These informal institutions carry out the functions of a formal legal system—they establish and enforce rules for the prevention, punishment, and redress of cybersecurity-related harms,” Dourado noted.

For example, a diverse array of computer security incident response teams (CSIRTs) operates around the globe and share their research and coordinate their responses to viruses and other online attacks. Individual Internet service providers (ISPs), domain name registrars, and hosting companies, work with these CSIRTs and other individuals and organizations to address security vulnerabilities. A growing market for private security consultants and software providers also competes to offer increasingly sophisticated suites of security products for businesses, households, and governments.

A great deal of security knowledge is also “crowd-sourced” today via online discussion forums and security blogs that feature contributions from experts and average users alike. University-based computer science and cyberlaw centers (like Citizen Lab) and experts have also helped by creating projects like “Stop Badware,” which originated at Harvard University but then grew into a broader non-profit organization with diverse financial support.

Dourado continues on in his paper to show how these informal, bottom-up efforts to coordinate security responses offer several advantages over top-down government solutions, such as administrative regulation or punishing liability regimes.

Dourado’s description of the ideal approach to online security is entirely consistent with Deibert’s vision in Black Code. In fact, Deibert notes, “It is important to remind ourselves that in spite of the threats, cyberspace runs well and largely without persistent disruption. On a technical level, this efficiency is founded on open and distributed networks of local engineers who share information as peers,” he observes. (p. 240) That is exactly right, but I wish Deibert would have spent more time discussing how this system works in practice today and how it can be tweaked and improved to head off the heavy-handed and very costly top-down solutions that we both dread.

Toward Resiliency

But there’s one other thing I wish Deibert would have explored in the book: resiliency, or how we have adapted to various cyber-vulnerabilities over time.

For example, in another recent Mercatus Center study entitled “Beyond Cyber Doom: Cyber Attack Scenarios and the Evidence of History,” Sean Lawson, an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Utah, has stressed the importance of resiliency as it pertains to cybersecurity and concerns about “cyberwar.” “Research by historians of technology, military historians, and disaster sociologists has shown consistently that modern technological and social systems are more resilient than military and disaster planners often assume,” he writes. “Just as more resilient technological systems can better respond in the event of failure, so too are strong social systems better able to respond in the event of disaster of any type.”

More generally, as I noted in my recent law review article on “technopanics” and “threat inflation” in information technology policy debates:

while it is certainly true that “more could be done” to secure networks and critical systems, panic is unwarranted because much is already being done to harden systems and educate the public about risks. Various digital attacks will continue, but consumers, companies, and others organizations are learning to cope and become more resilient in the face of those threats.

What Professor Lawson and I are getting at in our respective articles is that the ability of organizations, institutions, and individuals to bounce back from adversity is a frequently unheralded feature of various systems and that it deserves more serious study. (See Andrew Zolli and Ann Marie Healy’s nice book, Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back, for more on this general topic). In the context of online security, what is most remarkable to me is not that the Internet suffers from vulnerabilities due to its open and interconnected nature; it’s that we don’t suffer far more damage as a result.

This gets us back to that very profound question that Deibert poses in Black Code: “Is it only a matter of time before the whole system collapses?” The better question, I think, is: why hasn’t the system already collapsed? Perhaps the answer is, because things haven’t gotten bad enough yet. But I believe that the more realistic answer is that: individuals and institutions often learn how to cope and become resilient in the face of adversity. This is partially the case online because of the stewardship and distributed, decentralized security we already see at work today that makes digital life tolerable.

But it has to be something more than that. After all, many of the security problems that Deibert describes in his book are quite serious and already affect millions of us today. How, then, are we getting by right now? Again, I think the answer has to be that adaptation and resiliency are at work on many different levels of online life.

Consider, for example, how we have learned to deal with spam, viruses, online porn, various online advertising and privacy concerns, and so on. Our adaptation to these threats and annoyances has not been perfectly smooth, of course. No doubt, some people would still like “something to be done” about these things. But isn’t it remarkable how we have, nonetheless, carried on with online commerce and interactive social life even as these problems have persisted?

Conclusion

Going forward, therefore, perhaps there are some reasons for hope. Perhaps the various generic strategies that Deibert outlines in his book, coupled with the remarkable ability of humans to roll with the punches and adapt, will help us come out of this just fine (or at least reasonably well).

Of course, it could also be the case that these security concerns just multiply and that the Internet then morphs into sometime quite different than the interconnected “network of networks” we know today. As I noted in my 2009 essay on “Internet Security Concerns, Online Anonymity, and Splinternets,” we might be moving toward a world with more separate disconnected digital networks and online “gated communities.” This could take place spontaneously over time and be driven by corporations seeking to satisfy the demand of some consumers for safer and more secure online experiences. As I noted in my review of Jonathan Zittrain’s book, The Future of the Internet, I am actually fine with some of that. I think we can live in a hybrid world of “walled gardens” alongside of the “Wild West” open Internet, so long as this occurs in a spontaneous, organic, bottom-up fashion. [For a more extensive discussion, see my book chapter, "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 – Saving the Net From Its Supporters."]

If, however, this “splintering” of the Net is done from the top-down through intentional (or even incidental) government action, then it is far more problematic. We already see signs, for example, that Russia is pushing even more strongly in that direction in the wake of the NSA leaks. (See “N.S.A. Leaks Revive Push in Russia to Control Net,” New York Times, July 14.) The Russians have been using amorphous security concerns to push for greater Internet control for some time now. Of course, China has been there for years. So have many Middle Eastern countries. Of course, there’s no guarantee that their respective “splinternets” are, or would be, any more secure than today’s Internet, but it sure would make those networks far more susceptible to state control and surveillance. If that’s our future, then it certainly is a dismal one.

Anyway, read Ron Deibert’s Black Code for an interesting exploration of these and other issues. It’s an excellent contribution to field of Internet policy studies and a book that I’ll be recommending to others for many years to come.

Additional resources:

the official website for Black Code

the Citizen Lab website at the University of Toronto

follow Ronald Deibert and The Citizen Lab on Twitter

video of Washington, D.C. book launch for Black Code (held at the National Endowment for Democracy on 6/24/13)

Other books you should read alongside “Black Code” (links are for my reviews of each book):

Access Controlled: The Shaping of Power, Rights, and Rule in Cyberspace edited by Ronald J. Deibert, John G. Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski, and Jonathan Zittrain

Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle for Internet Freedom , by Rebecca MacKinnon

Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It , by Richard A. Clarke and Robert K. Knake

Liars & Outliers: Enabling the Trust that Society Needs to Thrive , by Bruce Schneier

Regulating Code: Good Governance and Better Regulation in the Information Age , by Ian Brown & Christopher T. Marsden

Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance , by Milton Mueller

Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back , by Andrew Zolli & Ann Marie Healy

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower