Adam Thierer's Blog, page 39

February 5, 2015

This Is Not How We Should Ensure Net Neutrality

Chairman Thomas E. Wheeler of the Federal Communications Commission unveiled his proposal this week for regulating broadband Internet access under a 1934 law. Since there are three Democrats and two Republicans on the FCC, Wheeler’s proposal is likely to pass on a party-line vote and is almost certain to be appealed.

Free market advocates have pointed out that FCC regulation is not only unnecessary for continued Internet openness, but it could lead to years of disruptive litigation and jeopardize investment and innovation in the network.

Writing in WIRED magazine, Wheeler argues that the Internet wouldn’t even exist if the FCC hadn’t mandated open access for telephone network equipment in the 1960s, and that his mid-1980s startup either failed or was doomed because the phone network was open whereas the cable networks (on which his startup depended) were closed. He also predicts that regulation can be accomplished while encouraging investment in broadband networks, because there will be “no rate regulation, no tariffs, no last-mile unbundling.” There are a number of problems with Chairman Wheeler’s analysis. First, let’s examine the historical assumptions that underlie the Wheeler proposal.

The FCC had to mandate open access for network equipment in the late 1960s only because of the unintended consequences of another regulatory objective—that of ensuring that basic local residential phone service was “affordable.” In practice, strict price controls required phone companies to set local rates at or below cost. The companies were permitted to earn a profit only by charging high prices for all of their other services including long-distance. Open access threatened this system of cross-subsidies, which is why the FCC strongly opposed open access for years. The FCC did not seriously rethink this policy until it was forced to do so by a federal appeals court ruling in the 1950s. That court decision set the stage for the FCC’s subsequent open access rules. Wheeler is trying to claim credit for a heroic achievement, when actually all the commission did was clean up a mess it created.

The failure of Wheeler’s Canadian government-subsidized startup in 1985 had nothing to do with open access, according to Wikipedia. NABU Network was attempting to sell up to 6.4 Mbps broadband service over Canadian cable networks notwithstanding the extremely limited capabilities of the network at the time. For one thing, most cable networks of that era were not bi-directional. The reason Wheeler’s startup didn’t choose to offer broadband over open telephone networks is because under-investment rendered those networks unsuitable. The copper loop simply didn’t offer the same bandwidth as coaxial cable. Why was there under-investment? Because of over-regulation.

Next, let’s examine Chairman Wheeler’s prediction that new regulation won’t discourage investment because there will be “no rate regulation, no tariffs, no last-mile unbundling.” Let’s be real. Wheeler simply cannot guarantee there will be no rate regulation, no tariffs, no last-mile unbundling nor other inappropriate regulation in the future. Anyone can petition the FCC to impose more regulation at any time, and nothing will prevent the commission from going down that road. The FCC will become a renewed target for special-interest pleading if Chairman Wheeler’s proposal is adopted by the commission and upheld by the courts.

Wheeler’s proposal would reclassify broadband as a “telecommunications” service notwithstanding the fact that the commission has previously found that broadband is an “information” service and the Supreme Court upheld that determination. These terms are clearly defined in the In the 1996 telecom act, in which bipartisan majorities in Congress sought to create a regulatory firewall. Communications services would continue to be regulated until they became competitive. Services that combine communications and computing (“information” services) would not be regulated at all. Congress wanted to create appropriate incentives for firms that provide communications service to invest and innovate by adding computing functionality. Congress was well aware that the commission tried over many years to establish a bright-line separation between communications and computing, and it failed. It’s an impossible task, because communications and computing are becoming more integrated all the time. The solution was to maintain legacy regulation for legacy network services, and open the door to competition for advanced services. The key issue now is whether or not broadband is a competitive industry. If the broadband offerings of cable operators, telephone companies and wireless providers are all taken into account, the answer is clearly yes.

In the view of Chairman Wheeler and others, regulation is needed to ensure the Internet is fast, fair and open. In reality, the Internet wants to be fast, fair and open. So called “walled garden” experiments of the past have all ended in failure. Before broadband, the open telephone network was significantly more profitable than the closed cable network. Now, broadband either is or soon will become more profitable than cable. Since open networks are more profitable than closed networks, legacy regulation is more than likely to be unnecessary and almost certain to be counter-productive. Internet openness is chiefly a function not of regulation but of innovation and investment in bandwidth abundance. With sufficient bandwidth, all packets travel at the speed of light.

Then again, this debate isn’t really about open networks. Republican leaders in Congress are offering to pass a bill that would prevent blocking and paid prioritization, and they can’t find any Democratic co-sponsors. That’s because the bill would prohibit reclassification of broadband as a “telecommunications” service, which would give the FCC a green light to regulate like it’s 1934. The idea that we need to give the commission unfettered authority so it can enact a limited amount of “smart” regulation that can be accomplished while encouraging private investment–and that we can otherwise rely on the FCC to practice regulatory restraint and not abuse its power–sounds a lot like the sales pitch for the Affordable Care Act, i.e., that we can have it all, there are no trade-offs. Right.

February 4, 2015

Permissionless Innovation & Commercial Drones

Farhad Manjoo’s latest New York Times column, “Giving the Drone Industry the Leeway to Innovate,” discusses how the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) current regulatory morass continues to thwart many potentially beneficial drone innovations. I particularly appreciated this point:

But perhaps the most interesting applications for drones are the ones we can’t predict. Imposing broad limitations on drone use now would be squashing a promising new area of innovation just as it’s getting started, and before we’ve seen many of the potential uses. “In the 1980s, the Internet was good for some specific military applications, but some of the most important things haven’t really come about until the last decade,” said Michael Perry, a spokesman for DJI [maker of Phantom drones]. . . . He added, “Opening the technology to more people allows for the kind of innovation that nobody can predict.”

That is exactly right and it reflects the general notion of “permissionless innovation” that I have written about extensively here in recent years. As I summarized in a recent essay: “Permissionless innovation refers to the notion that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted by default. Unless a compelling case can be made that a new invention or business model will bring serious harm to individuals, innovation should be allowed to continue unabated and problems, if they develop at all, can be addressed later.”

The reason that permissionless innovation is so important is that innovation is more likely in political systems that maximize breathing room for ongoing economic and social experimentation, evolution, and adaptation. We don’t know what the future holds. Only incessant experimentation and trial-and-error can help us achieve new heights of greatness. If, however, we adopt the opposite approach of “precautionary principle”-based reasoning and regulation, then these chances for serendipitous discovery evaporate. As I put it in my recent book, “living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy upon them—means that best-case scenarios will never come about. When public policy is shaped by precautionary principle reasoning, it poses a serious threat to technological progress, economic entrepreneurialism, social adaptation, and long-run prosperity.”

In this regard, the unprecedented growth of the Internet is a good example of how permissionless innovation can significantly improve consumer welfare and our nation’s competitive status relative to the rest of the world. And this also holds lessons for how we treat commercial drone technologies, as Jerry Brito, Eli Dourado, and I noted when filing comments with the FAA back in April 2013. We argued:

Like the Internet, airspace is a platform for commercial and social innovation. We cannot accurately predict to what uses it will be put when restrictions on commercial use of UASs are lifted. Nevertheless, experience shows that it is vital that innovation and entrepreneurship be allowed to proceed without ex ante barriers imposed by regulators. We therefore urge the FAA not to impose any prospective restrictions on the use of commercial UASs without clear evidence of actual, not merely hypothesized, harm.

Manjoo builds on that same point in his new Times essay when he notes:

[drone] enthusiasts see almost limitless potential for flying robots. When they fantasize about our drone-addled future, they picture not a single gadget, but a platform — a new class of general-purpose computer, as important as the PC or the smartphone, that may be put to use in a wide variety of ways. They talk about applications in construction, firefighting, monitoring and repairing infrastructure, agriculture, search and response, Internet and communications services, logistics and delivery, filmmaking and wildlife preservation, among other uses.

If only the folks at the FAA and in Congress saw things this way. We need to open up the skies to the amazing innovative potential of commercial drone technology, especially before the rest of the world seizes the opportunity to jump into the lead on this front.

___________________________

Additional Reading

DRM for Drones Will Fail, January 28, 2015.

Regulatory Capture: FAA and Commercial Drones Edition, January 16, 2015.

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Commercial Drones & Sharing Economy Edition, December 9, 2014.

How to Destroy American Innovation: The FAA & Commercial Drones, October 6, 2014.

Filing to FAA on Drones & “Model Aircraft”, Sept. 23, 2014.

Private Drones & the First Amendment, Sept. 19, 2014.

[TV interview] The Beneficial Uses of Private Drones, March 28, 2014.

Comments of the Mercatus Center to the FAA on integration of drones into the nation’s airspace, April 23, 2o13.

Eli Dourado, Deregulate the Skies: Why We Can’t Afford to Fear Drones, Wired, April 23, 2013.

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom (2014).

[Video] Cap Hill Briefing on Emerging Tech Policy Issues (June 2014).

February 3, 2015

New FCC rules will kick at least 4.7 million households offline

This month, the FCC is set to issue an order that will reclassify broadband under Title II of the Communications Act. As a result of this reclassification, broadband will suddenly become subject to numerous federal and local taxes and fees.

How much will these new taxes reduce broadband subscribership? Nobody knows for sure, but using the existing economic literature we can come up with a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

According to a policy brief by Brookings’s Bob Litan and the Progressive Policy Institute’s Hal Singer, reclassification under Title II will increase fixed broadband costs on average by $67 per year due to both federal and local taxes. With pre-Title II costs of broadband at $537 per year, this represents a 12.4 percent increase.

[I have updated these estimates at the end of this post.]

How much will this 12.4 percent increase in broadband costs reduce the number of broadband subscriptions demanded? For that, we must turn to the literature on the elasticity of demand for broadband.

As is often the case, the literature on this subject does not give one clear answer. For example, Austan Goolsbee, who was chairman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors in 2010 and 2011, estimated in 2006 that broadband elasticity ranged from -2.15 to -3.76, with an average of around -2.75.

A 2014 study by two FCC economists and their coauthors estimates the elasticity of demand for marginal non-subscribers. That is, they use survey data of people who are not currently broadband subscribers, exclude the 2/3 of respondents who say they would not buy broadband at any price, and estimate their demand elasticity at -0.62.

Since the literature doesn’t settle the matter, let’s pick the more conservative number and use it as a lower bound.

With 84 million fixed broadband subscribers facing a 12.4 percent increase in prices, with an elasticity of -0.62, there will be a 7.7 percent reduction in broadband subscribers, or a decline of 6.45 million households.

Obviously, this is a terrible result.

A question for my friends in the tech policy world who support reclassification: How many households do you think will lose broadband access due to new taxes and fees? Please show your work.

UPDATE: Looks like I missed this updated post from Singer and Litan, which notes that due to the extension of the Internet Tax Freedom Act, the total amount of new taxes from reclassification will be only about $49/year, not $67/year as stated above.

This represents a 9.1 percent increase in costs, so the number of households with broadband will decline by only 5.6 percent, or 4.7 million.

While I regret the oversight, this is still a very high number that deserves attention.

Network Neutrality’s Watershed Moment

After some ten years, gallons of ink and thousands of megabytes of bandwidth, the debate over network neutrality is reaching a climactic moment.

Bills are expected to be introduced in both the Senate and House this week that would allow the Federal Communications Commission to regulate paid prioritization, the stated goal of network neutrality advocates from the start. Led by Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.) and Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), the legislation represents a major compromise on the part of congressional Republicans, who until now have held fast against any additional Internet regulation. Their willingness to soften on paid prioritization has gotten the attention of a number of leading Democrats, including Sens. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) and Cory Booker (D-N.J.). The only question that remains is if FCC Chairman Thomas Wheeler and President Barack Obama are willing to buy into this emerging spirit of partisanship.

Obama wants a more radical course—outright reclassification of Internet services under Title II of the Communications Act, a policy Wheeler appears to have embraced in spite of reservations he expressed last year. Title II, however, would give the FCC the same type of sweeping regulatory authority over the Internet as it does monopoly phone service—a situation that stands to create a “Mother, may I” regime over what, to date, has been an wildly successful environment of permissionless innovation.

Important to remember is that Title II reclassification is a response to repeated court decisions preventing the FCC from enforcing certain provisions against paid prioritization. Current law, the courts affirmed, classifies the Internet as an information service, a definition that limits the FCC’s regulatory control over it. Using reclassification, the FCC hopes to give itself the necessary legal cover.

But the paid prioritization matter can addressed easily, elegantly and, most important, constitutionally, through Congress.

As a libertarian, I question the value of any regulation on the Internet on principle. And practically speaking, there’s been no egregious abuse of paid prioritization that justifies unilateral reclassification. It’s not in an ISPs interest to block any websites. And, contrary to being a consumer problem, allowing major content companies like Netflix to purchase network management services that improve the quality of video delivery while reducing network congestion for other applications might actually serve the market.

But if paid prioritization is the concern, then Thune-Upton addresses it. It would allow the FCC to investigate and impose penalties on ISPs that throttle traffic, or demand payment for quality delivery. On the other hand, Thune-Upton would also create carve outs for certain types of applications that require prioritization to work, like telemedicine and emergency services, and would allow for the reasonable network management that is necessary for optimum performance—answering criticisms that come not only from center-right policy analysts, but from network engineers.

Legislation also gives the FCC specific instructions, whereas Title II reclassification opens the door to large-scale, open-ended regulation. Here’s where I do indulge my libertarian leanings. Giving the government vague, unspecified powers asks for trouble. All we have to do is look at the National Security Agency’s widespread warrantless wiretapping and the Drug Enforcement Administration’s tracking of private vehicle movements around the country. Disturbing as they are to all citizens who value liberty and privacy, these practices are technically legal because there are no laws setting rules of due process with contemporary communications technology (a blog for another day). As much as the FCC promises to “forbear” more extensive Internet regulation, it’s better for all if specific limits are written in.

At the same time, the addition of regulatory powers invites corporate rent-seeking whereby companies turn to the government to protect them in the marketplace. Even as the FCC was drafting its Title II proposal, BlackBerry’s CEO, John Chen, were complaining that applications developers were only focusing on the iPhone and Android platforms. Chen seeks “app neutrality,” essentially a law to require any applications that work on iPhone and Android platforms to work on BlackBerry’s operating system, too, despite the low marker penetration of the devices.

Also, forcing the FCC to work inside narrow parameters means it can more readily ease up or even reverse itself in case a ban on paid prioritization leads to intended consequences, like a significant uptick in bandwidth congestion and measureable degradation in applications performance.

Finally, successful bi-partisan legislation can put net neutrality to bed. If the White House remains stubborn and instead pushes the FCC to reclassify, it almost assures a lengthy court case that not only would drag out the debate, but likely end with another decision against the FCC. But even if the court rulings go the FCC’s way, Title II is no guarantee against paid prioritization. Allowing Congress to give the FCC the necessary authority is constitutionally sound approach and has a better chance of meeting the desired objectives. Congress is offering a bipartisan solution that is reasonable and workable. The Obama administration has been banging the drum for network neutrality since Day 1. This is its moment to seize.

February 2, 2015

Money for graduate students who love liberty

My employer, the Mercatus Center, provides ridiculously generous funding (up to $40,000/year) for graduate students. There are several opportunities depending on your goals, but I encourage people interested in technology policy to particularly consider the MA Fellowship, as that can come with an opportunity to work with the tech policy team here at Mercatus. Mind the deadlines!

The PhD Fellowship is a three-year, competitive, full-time fellowship program for students who are pursuing a doctoral degree in economics at George Mason University. Our PhD Fellows take courses in market process economics, public choice, and institutional analysis and work on projects that use these lenses to understand global prosperity and the dynamics of social change. Successful PhD Fellows have secured tenure track positions at colleges and universities throughout the US and Europe.

It includes full tuition support, a stipend, and experience as a research assistant working closely with Mercatus-affiliated Mason faculty. It is a total award of up to $120,000 over three years. Acceptance into the fellowship program is dependent on acceptance into the PhD program in economics at George Mason University. The deadline for applications is February 1, 2015.

The Adam Smith Fellowship is a one-year, competitive fellowship for graduate students attending PhD programs at any university, in a variety of fields, including economics, philosophy, political science, and sociology. The aim of this fellowship is to introduce students to key thinkers in political economy that they might not otherwise encounter in their graduate studies. Smith Fellows receive a stipend and spend three weekends during the academic year and one week during the summer participating in workshops and seminars on the Austrian, Virginia, and Bloomington schools of political economy.

It includes a quarterly stipend and travel and lodging to attend colloquia hosted by the Mercatus Center. It is a total award of up to $10,000 for the year. Acceptance into the fellowship program is dependent on acceptance into a PhD program at an accredited university. The deadline for applications is March 15, 2015.

The MA Fellowship is a two-year, competitive, full-time fellowship program for students pursuing a master’s degree in economics at George Mason University who are interested in gaining advanced training in applied economics in preparation for a career in public policy. Successful fellows have secured public policy positions as Presidential Management Fellows, economists and analysts with federal and state governments, and policy analysts at prominent research institutions.

It includes full tuition support, a stipend, and practical experience as a research assistant working with Mercatus scholars. It is a total award of up to $80,000 over two years. Acceptance into the fellowship program is dependent on acceptance into the MA program in economics at George Mason University. The deadline for applications is March 1, 2015.

The Frédéric Bastiat Fellowship is a one-year competitive fellowship program for graduate students interested in pursuing a career in public policy. The aim of this fellowship is to introduce students to the Austrian, Virginia, and Bloomington schools of political economy as academic foundations for pursuing contemporary policy analysis. They will explore how this framework is utilized to analyze policy implications of a variety of topics, including the study of American capitalism, state and local policy, regulatory studies, technology policy, financial markets, and spending and budget.

It includes a quarterly stipend and travel and lodging to attend colloquia hosted by the Mercatus Center. It is a total award of up to $5,000 for the year. Acceptance into the fellowship program is dependent on acceptance into a graduate program at an accredited university. The deadline for applications is April 1, 2015.

January 30, 2015

The LAPD versus the First Amendment

Last month, my Mercatus Center colleague Brent Skorup published a major scoop: police departments around the country are scanning social media to assign people individualized “threat ratings” — green, yellow, or red. This week, police are complaining that the public is using social media to track them back.

LAPD Chief Charlie Beck has expressed concerns that Waze, the social traffic app owned by Google, could be used to target police officers. The National Sherriff’s Association has also complained about the app.

To be clear, Waze does not allow anybody to track individual officers. Users of the app can drop a pin on a map letting drivers know that there is police activity (or traffic jams, accidents, or traffic enforment cameras) in the area.

That’s it.

And police departments around the country frequently publicize their locations. They are essentially required to do so for sobriety checkpoints bySupreme Court order and NHTSA guidelines.

But in a letter to Google CEO Larry Page, Beck writes breathlessly that Waze “poses a danger to the lives of police officers in the United States.” The letter also (falsely) states that the app was used by Ismaaiyl Brinsley to kill two NYPD officers. The Associated Press notes that “Investigators do not believe he used Waze to ambush the officers, in part because police say Brinsley tossed his cellphone more than two miles from where he shot the officers.”

It’s somewhat rich of the LAPD to cite fear for its officers’ lives while the department is in possession of some 3408 assault rifles, 7 armored vehicles, and 3 grenade launchers.

In fact, what Waze poses a danger to is police department revenue. Drivers are using the app as a crowdsourced radar detector, as a means of avoiding traffic tickets. But unlike radar detectors, which have been outlawed in my home state of Virginia, Waze benefits from First Amendment protection.

The fundamental activity that Waze users are engaging in is speech. “Hey, there is a cop over there,” is protected speech under the First Amendment. As all LAPD officers must swear an oath affirming that they “will support and defend the Constitution of the United States,” it seems reasonable to expect the police chief not to stifle, by lobbying private corporations, the First Amendment rights of those citizens who choose to engage in this protected activity.

The Waze kerfuffle is a symptom of a longer-term breakdown in trust between police departments around the country and the publics they are sworn to protect and serve. This is a widely recognized problem, and some in the law enforcement community are working on strategies to remedy it.

But as long as departments continue to view the public as the enemy or even as a passive revenue source, not as the rightful recipients of their service and protection, we will continue to see the public respond by introducing technologies that protect users from the police’s arbitrary powers.

Fortunately, police complaints about Waze have backfired. Many smartphone users had no idea there was an app for avoiding speeding tickets until Beck and the Sherriff’s Association made it national news. As a result of the publicity, downloads of Waze have skyrocketed.

Police are running a media blitz against Google Waze. It helps drivers avoid traps. Here’s how iPhone users reacted… pic.twitter.com/gLv5x1kAGn

— Jonathan Mayer (@jonathanmayer) January 28, 2015

This is how the modern world works, and it gives me great hope for the future.

January 28, 2015

DRM for Drones Will Fail

I suppose it was inevitable that the DRM wars would come to the world of drones. Reporting for the Wall Street Journal today, Jack Nicas notes that:

In response to the drone crash at the White House this week, the Chinese maker of the device that crashed said it is updating its drones to disable them from flying over much of Washington, D.C.SZ DJI Technology Co. of Shenzhen, China, plans to send a firmware update in the next week that, if downloaded, would prevent DJI drones from taking off within the restricted flight zone that covers much of the U.S. capital, company spokesman Michael Perry said.

Washington Post reporter Brian Fung explains what this means technologically:

The [DJI firmware] update will add a list of GPS coordinates to the drone’s computer telling it where it can and can’t go. Here’s how that system works generally: When a drone comes within five miles of an airport, Perry explained, an altitude restriction gets applied to the drone so that it doesn’t interfere with manned aircraft. Within 1.5 miles, the drone will be automatically grounded and won’t be able to fly at all, requiring the user to either pull away from the no-fly zone or personally retrieve the device from where it landed. The concept of triggering certain actions when reaching a specific geographic area is called “geofencing,” and it’s a common technology in smartphones. Since 2011, iPhone owners have been able to create reminders that alert them when they arrive at specific locations, such as the office.

This is complete overkill and it almost certainly will not work in practice. First, this is just DRM for drones, and just as DRM has failed in most other cases, it will fail here as well. If you sell somebody a drone that doesn’t work within a 15-mile radius of a major metropolitan area, they’ll be online minutes later looking for a hack to get it working properly. And you better believe they will find one.

Second, other companies or even non-commercial innovators will just use such an opportunity to promote their DRM-free drones, making the restrictions on other drones futile.

Perhaps, then, the government will push for all drone manufacturers to include DRM on their drones, but that’s even worse. The idea that the Washington, DC metro area should be a completely drone-free zone is hugely troubling. We might as well put up a big sign at the edge of town that says, “Innovators Not Welcome!”

And this isn’t just about commercial operators either. What would such a city-wide restriction mean for students interested in engineering or robotics in local schools? Or how about journalists who might want to use drones to help them report the news?

For these reasons, a flat ban on drones throughout this or any other city just shouldn’t fly.

Moreover, the logic behind this particular technopanic is particularly silly. It’s like saying that we should install some sort of kill switch in all automobile ignitions so that they will not start anywhere in the DC area on the off chance that one idiot might use their car to drive into the White House fence. We need clear and simple rules for drone use; not technically-unworkable and unenforceable bans on all private drone use in major metro areas.

Some Initial Thoughts on the FTC Internet of Things Report

Yesterday, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) released its long-awaited report on “The Internet of Things: Privacy and Security in a Connected World.” The 55-page report is the result of a lengthy staff exploration of the issue, which kicked off with an FTC workshop on the issue that was held on November 19, 2013.

I’m still digesting all the details in the report, but I thought I’d offer a few quick thoughts on some of the major findings and recommendations from it. As I’ve noted here before, I’ve made the Internet of Things my top priority over the past year and have penned several essays about it here, as well as in a big new white paper (“The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation”) that will be published in the Richmond Journal of Law & Technology shortly. (Also, here’s a compendium of most of what I’ve done on the issue thus far.)

I’ll begin with a few general thoughts on the FTC’s report and its overall approach to the Internet of Things and then discuss a few specific issues that I believe deserve attention.

Big Picture, Part 1: Should Best Practices Be Voluntary or Mandatory?

Generally speaking, the FTC’s report contains a variety of “best practice” recommendations to get Internet of Things innovators to take steps to ensure greater privacy and security “by design” in their products. Most of those recommended best practices are sensible as general guidelines for innovators, but the really sticky question here continued to be this: When, if ever, should “best practices” become binding regulatory requirements?

The FTC does a bit of a dance when answering that question. Consider how, in the executive summary of the report, the Commission answers the question regarding the need for additional privacy and security regulation: “Commission staff agrees with those commenters who stated that there is great potential for innovation in this area, and that IoT-specific legislation at this stage would be premature.” But, just a few lines later, the agency (1) “reiterates the Commission’s previous recommendation for Congress to enact strong, flexible, and technology-neutral federal legislation to strengthen its existing data security enforcement tools and to provide notification to consumers when there is a security breach;” and (2) “recommends that Congress enact broad-based (as opposed to IoT-specific) privacy legislation.”

Here and elsewhere, the agency repeatedly stresses that it is not seeking IoT-specific regulation; merely “broad-based” digital privacy and security legislation. The problem is that once you understand what the IoT is all about you come to realize that this largely represents a distinction without a difference. The Internet of Things is simply the extension of the Net into everything we own or come into contact with. Thus, this idea that the agency is not seeking IoT-specific rule sounds terrific until you realize that it is actually seeking something far more sweeping: greater regulation of all online / digital interactions. And because “the Internet” and “the Internet of Things” will eventually (if they are not already) be consider synonymous, this notion that the agency is not proposing technology-specific regulation is really quite silly.

Now, it remains unclear whether there exists any appetite on Capitol Hill for “comprehensive” legislation of any variety – although perhaps we’ll learn more about that possibility when the Senate Commerce Committee hosts a hearing on these issues on February 11. But at least thus far, “comprehensive” or “baseline” digital privacy and security bills have been non-starters.

And that’s for good reason in my opinion: Such regulatory proposals could take us down the path that Europe charted in the late 1990s with onerous “data directives” and suffocating regulatory mandates for the IT / computing sector. The results of this experiment have been unambiguous, as I documented in congressional testimony in 2013. I noted there how America’s Internet sector came to be the envy of the world while it was hard to name any major Internet company from Europe. Whereas America embraced “permissionless innovation” and let creative minds develop one of the greatest success stories in modern history, the Europeans adopted a “Mother, May I” regulatory approach for the digital economy. America’s more flexible, light-touch regulatory regime leaves more room for competition and innovation compared to Europe’s top-down regime. Digital innovation suffered over there while it blossomed here.

That’s why we need to be careful about adopting the sort of “broad-based” regulatory regime that the FTC recommends in this and previous reports.

Big Picture, Part 2: Does the FTC Really Need More Authority?

Something else is going on in this report that has also been happening in all the FTC’s recent activity on digital privacy and security matters: The agency has been busy laying the groundwork for its own expansion.

In this latest report, for example, the FTC argues that

Although the Commission currently has authority to take action against some IoT-related practices, it cannot mandate certain basic privacy protections… The Commission has continued to recommend that Congress enact strong, flexible, and technology-neutral legislation to strengthen the Commission’s existing data security enforcement tools and require companies to notify consumers when there is a security breach.

In other words, this agency wants more authority. And we are talking about sweeping authority here that would transcend its already sweeping authority to police “unfair and deceptive practices” under Section 5 of the FTC Act. Let’s be clear: It would be hard to craft a law that grants an agency more comprehensive and open-ended consumer protection authority than Section 5. The meaning of those terms — “unfairness” and “deception” — has always been a contentious matter, and at times the agency has abused its discretion by exploiting that ambiguity.

Nonetheless, Sec. 5 remains a powerful enforcement tool for the agency and one that has been wielded aggressively in recently years to police digital economy giants and small operators alike. Generally speaking, I’m alright with most Sec. 5 enforcement, especially since that sort of retrospective policing of unfair and deceptive practices is far less likely to disrupt permissionless innovation in the digital economy. That’s because it does not subject digital innovators to the sort of “Mother, May I” regulatory system that European entrepreneurs face. But an expansion of the FTC’s authority via more “comprehensive, baseline” privacy and security regulatory policies threatens to convert America’s more sensible bottom-up and responsive regulatory system into the sort of innovation-killing regime we see on the other side of the Atlantic.

Here’s the other thing we can’t forget when it comes to the question of what additional authority to give the FTC over privacy and security matters: The FTC is not the end of the enforcement story in America. Other enforcement mechanism exist, including: privacy torts, class action litigation, property and contract law, state enforcement agencies, and other targeted privacy statutes. I’ve summarized all these additional enforcement mechanisms in my recent law review article referenced above. (See section VI of the paper.)

FIPPS, Part 1: Notice & Choice vs. Use-Based Restrictions

Next, let’s drill down a bit and examine some of the specific privacy and security best practices that the agency discusses in its new IoT report.

The FTC report highlights how the IoT creates serious tensions for many traditional Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs). The FIPPs generally include: (1) notice, (2) choice, (3) purpose specification, (4) use limitation, and (5) data minimization. But the report is mostly focused on notice and choice as well as data minimization.

When it comes to notice and choice, the agency wants to keep hope alive that it will still be applicable in an IoT world. I’m sympathetic to this effort because it is quite sensible for all digital innovators to do their best to provide consumers with adequate notice about data collection practices and then give them sensible choices about it. Yet, like the agency, I agree that “offering notice and choice is challenging in the IoT because of the ubiquity of data collection and the practical obstacles to providing information without a user interface.”

The agency has a nuanced discussion of how context matters in providing notice and choice for IoT, but one can’t help but think that even they must realize that the game is over, to some extent. The increasing miniaturization of IoT devices and the ease with which they suck up data means that traditional approaches to notice and choice just aren’t going to work all that well going forward. It is almost impossible to envision how a rigid application of traditional notice and choice procedures would work in practice for the IoT.

Relatedly, as I wrote here last week, the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) recently released a new white paper entitled, “A Practical Privacy Paradigm for Wearables,” that notes how FIPPs “are a valuable set of high-level guidelines for promoting privacy, [but] given the nature of the technologies involved, traditional implementations of the FIPPs may not always be practical as the Internet of Things matures.” That’s particularly true of the notice and choice FIPPS.

But the FTC isn’t quite ready to throw in the towel and make the complete move toward “use-based restrictions,” as many academics have. (Note: I have lengthy discussion of this migration toward use-based restrictions in my law review article in section IV.D.). Use-based restrictions would focus on specific uses of data that are particularly sensitive and for which there is widespread agreement they should be limited or disallowed altogether. But use-based restrictions are, ironically, controversial from both the perspective of industry and privacy advocates (albeit for different reasons, obviously).

The FTC doesn’t really know where to go next with use-based restrictions. The agency says that, on one hand, “has incorporated certain elements of the use-based model into its approach” to enforcement in the past. On the other hand, the agency says it has concerns “about adopting a pure use-based model for the Internet of Things,” since it may not go far enough in addressing the growth of more widespread data collection, especially of more sensitive information.

In sum, the agency appears to be keeping the door open on this front and hoping that a best-of-all-worlds solution miraculously emerges that extends both notice and choice and use-based limitations as the IoT expands. But the agency’s new report doesn’t give us any sort of blueprint for how that might work, and that’s likely for good reason: because it probably won’t work at that well in practice and there will be serious costs in terms of lost innovation if they try to force unworkable solutions on this rapidly evolving marketplace.

FIPPS, Part 2: Data Minimization

The biggest policy fight that is likely to come out of this report involves the agency’s push for data minimization. The report recommends that, to minimize the risks associated with excessive data collection:

companies should examine their data practices and business needs and develop policies and practices that impose reasonable limits on the collection and retention of consumer data. However, recognizing the need to balance future, beneficial uses of data with privacy protection, staff’s recommendation on data minimization is a flexible one that gives companies many options. They can decide not to collect data at all; collect only the fields of data necessary to the product or service being offered; collect data that is less sensitive; or deidentify the data they collect. If a company determines that none of these options will fulfill its business goals, it can seek consumers’ consent for collecting additional, unexpected categories of data…

This is an unsurprising recommendation in light of the fact that, in previous major speeches on the issue, FTC Chairwoman Edith Ramirez argued that, “information that is not collected in the first place can’t be misused,” and that:

The indiscriminate collection of data violates the First Commandment of data hygiene: Thou shall not collect and hold onto personal information unnecessary to an identified purpose. Keeping data on the off chance that it might prove useful is not consistent with privacy best practices. And remember, not all data is created equally. Just as there is low quality iron ore and coal, there is low quality, unreliable data. And old data is of little value.

In my forthcoming law review article, I discussed the problem with such reasoning at length and note:

if Chairwoman Ramirez’s approach to a preemptive data use “commandment” were enshrined into a law that said, “Thou shall not collect and hold onto personal information unnecessary to an identified purpose.” Such a precautionary limitation would certainly satisfy her desire to avoid hypothetical worst-case outcomes because, as she noted, “information that is not collected in the first place can’t be misused,” but it is equally true that information that is never collected may never lead to serendipitous data discoveries or new products and services that could offer consumers concrete benefits. “The socially beneficial uses of data made possible by data analytics are often not immediately evident to data subjects at the time of data collection,” notes Ken Wasch, president of the Software & Information Industry Association. If academics and lawmakers succeed in imposing such precautionary rules on the development of IoT and wearable technologies, many important innovations may never see the light of day.

FTC Commissioner Josh Wright issued a dissenting statement to the report that lambasted the staff for not conducting more robust cost-benefit analysis of the new proposed restrictions, and specifically cited how problematic the agency’s approach to data minimization was. “[S]taff merely acknowledges it would potentially curtail innovative uses of data. . . [w]ithout providing any sense of the magnitude of the costs to consumers of foregoing this innovation or of the benefits to consumers of data minimization,” he says. Similarly, in her separate statement, FTC Commissioner Maureen K. Ohlhausen worried about the report’s overly precautionary approach on data minimization when noting that, “without examining costs or benefits, [the staff report] encourages companies to delete valuable data — primarily to avoid hypothetical future harms. Even though the report recognizes the need for flexibility for companies weighing whether and what data to retain, the recommendation remains overly prescriptive,” she concludes.

Regardless, the battle lines have been drawn by the FTC staff report as the agency has made it clear that it will be stepping up its efforts to get IoT innovators to significantly slow or scale back their data collection efforts. It will be very interesting to see how the agency enforces that vision going forward and how it impacts innovation in this space. All I know is that the agency has not conducted a serious evaluation here of the trade-offs associated with such restrictions. I penned another law review article last year offering “A Framework for Benefit-Cost Analysis in Digital Privacy Debates” that they could use to begin that process if they wanted to get serious about it.

The Problem with the “Regulation Builds Trust” Argument

One of the interesting things about this and previous FTC reports on privacy and security matters is how often the agency premises the case for expanded regulation on “building trust.” The argument goes something like this (as found on page 51 of the new IoT report): “Staff believes such legislation will help build trust in new technologies that rely on consumer data, such as the IoT. Consumers are more likely to buy connected devices if they feel that their information is adequately protected.”

This is one of those commonly-heard claims that sounds so straight-forward and intuitive that few dare question it. But there are problems with the logic of the “we-need-regulation-to-build-trust-and boost adoption” arguments we often hear in debates over digital privacy.

First, the agency bases its argument mostly on polling data. “Surveys also show that consumers are more likely to trust companies that provide them with transparency and choices,” the report says. Well, of course surveys say that! It’s only logical that consumers will say this, just as they will always say they value privacy and security more generally when asked. You might as well ask people if they love their mothers!

But what consumers claim to care about and what they actually do in the real-world are often two very different things. In the real-world, people balance privacy and security alongside many other values, including choice, convenience, cost, and more. This leads to the so-called “privacy paradox,” or the problem of many people saying one thing and doing quite another when it comes to privacy matters. Put simply, people take some risks — including some privacy and security risks — in order to reap other rewards or benefits. (See this essay for more on the problem with most privacy polls.)

Second, online activity and the Internet of Things are both growing like gangbusters despite the privacy and security concerns that the FTC raises. Virtually every metric I’ve looked at that track IoT activity show astonishing growth and product adoption, and projections by all the major consultancies that have studied this consistently predict the continued rapid growth of IoT activity. Now, how can this be the case if, as the FTC claims, we’ll only see the IoT really take off after we get more regulation aimed at bolstering consumer trust? Of course, the agency might argue that the IoT will grow at an even faster clip than it is right now, but there is no way to prove one way or the other. In any event, the agency cannot possible claim that the IoT isn’t already growing at a very healthy clip — indeed, a lot of the hand-wringing the staff engages in throughout the report is premised precisely on the fact that the IoT is exploding faster that our ability to keep up with it!! In reality, it seems far more likely that cost and complexity are the bigger impediments to faster IoT adoption, just as cost and complexity have always been the factors weighing most heavily on the adoption of other digital technologies.

Third, let’s say that the FTC is correct – and it is – when it says that a certain amount of trust is needed in terms of IoT privacy and security before consumers are willing to use more of these devices and services in their everyday lives. Does the agency imagine that IoT innovators don’t know that? Are markets and consumers completely irrational? The FTC says on page 44 of the report that, “If a company decides that a particular data use is beneficial and consumers disagree with that decision, this may erode consumer trust.” Well, if such a mismatch does exist, then the assumption should be that consumers can and will push back, or seek out new and better options. And other companies should be able to sense the market opportunity here to offer a more privacy-centric offering for those consumers who demand it in order to win their trust and business.

Finally, and perhaps most obviously, the problem with the argument that increased regulation will help IoT adoption is that it ignores how the regulations put in place to achieve greater “trust” might become so onerous or costly in practice that there won’t be as many innovations for us to adopt to begin with! Again, regulation — even very well-intentioned regulation — has costs and trade-offs.

In any event, if the agency is going to premise the case for expanded privacy regulation on this notion, they are going to have to do far more to make their case besides simply asserting it.

Once Again, No Appreciation of the Potential for Societal Adaptation

Let’s briefly shift to a subject that isn’t discussed in the FTC’s new IoT report at all.

Regular readers may get tired of me making this point, but I feel it is worth stressing again: Major reports and statements by public policymakers about rapidly-evolving emerging technologies are always initially prone to stress panic over patience. Rarely are public officials willing to step-back, take a deep breath, and consider how a resilient citizenry might adapt to new technologies as they gradually assimilate new tools into their lives.

That is really sad, when you think about it, since humans have again and again proven capable of responding to technological change in creative ways by adopting new personal and social norms. I won’t belabor the point because I’ve already written volumes on this issue elsewhere. I tried to condense all my work into a single essay entitled, “Muddling Through: How We Learn to Cope with Technological Change.” Here’s the key takeaway:

humans have exhibited the uncanny ability to adapt to changes in their environment, bounce back from adversity, and learn to be resilient over time. A great deal of wisdom is born of experience, including experiences that involve risk and the possibility of occasional mistakes and failures while both developing new technologies and learning how to live with them. I believe it wise to continue to be open to new forms of innovation and technological change, not only because it provides breathing space for future entrepreneurialism and invention, but also because it provides an opportunity to see how societal attitudes toward new technologies evolve — and to learn from it. More often than not, I argue, citizens have found ways to adapt to technological change by employing a variety of coping mechanisms, new norms, or other creative fixes.

Again, you almost never hear regulators or lawmakers discuss this process of individual and social adaptation even though they must know there is something to it. One explanation is that every generation has their own techno-boogeymen and lose faith in the ability of humanity to adapt to it.

To believe that we humans are resilient, adaptable creatures should not be read as being indifferent to the significant privacy and security challenges associated with any of the new technologies in our lives today, including IoT technologies. Overly-exuberant techno-optimists are often too quick to adopt a “Just-Get-Over-It!” attitude in response to the privacy and security concerns raised by others. But it is equally unforgivable for those who are worried about those same concerns to utterly ignore the reality of human adaptation to new technologies realities.

Why are Educational Approaches Merely an Afterthought?

One final thing that troubled me about the FTC report was the way consumer and business education is mostly an afterthought. This is one of the most important roles that the FTC can and should play in terms of explaining potential privacy and security vulnerabilities to the general public and product developers alike.

Alas, the agency devotes so much ink to the more legalistic questions about how to address these issues, that all we end up with in the report is this one paragraph on consumer and business education:

Consumers should understand how to get more information about the privacy of their IoT devices, how to secure their home networks that connect to IoT devices, and how to use any available privacy settings. Businesses, and in particular small businesses, would benefit from additional information about how to reasonably secure IoT devices. The Commission staff will develop new consumer and business education materials in this area.

I applaud that language, and I very much hope that the agency is serious about plowing more effort and resources into developing new consumer and business education materials in this area. But I’m a bit shocked that the FTC report didn’t even bother mentioning the excellent material already available on the “On Guard Online” website it helped created with a dozen other federal agencies. Worse yet, the agency failed to highlight the many other privacy education and “digital citizenship” efforts that are underway today to help on this front. I discuss those efforts in more detail in the closing section of my recent law review article.

I hope that the agency spends a little more time working on the development of new consumer and business education materials in this area instead of trying to figure out how to craft a quasi-regulatory regime for the Internet of Things. As I noted last year in this Maine Law Review article, that would be a far more productive use of the agency’s expertise and resources. I argued there that “policymakers can draw important lessons from the debate over how best to protect children from objectionable online content” and apply them to debates about digital privacy. Specifically, after a decade of searching for legalistic solutions to online safety concerns — and convening a half-dozen blue ribbon task forces to study the issue — we finally saw a rough consensus emerge that no single “silver-bullet” technological solutions or legal quick-fixes would work and that, ultimately, education and empowerment represented the better use of our time and resources. What was true for child safety is equally true for privacy and security for the Internet of Things.

It’s a shame the FTC staff squandered the opportunity it had with this new report to highlight all the good that could be done by getting more serious about focusing first on those alternative, bottom-up, less costly, and less controversial solutions to these challenging problems. One day we’ll all wake up and realize that we spent a lost decade debating legalistic solutions that were either technically unworkable or politically impossible. Just imagine if all the smart people who were spending all their time and energy on those approaches right now were instead busy devising and pushing educational and empowerment-based solutions instead!

One day we’ll get there. Sadly, if the FTC report is any indication, that day is still a ways off.

January 27, 2015

Television is competitive. Congress should end mass media industrial policy.

Congress is considering reforming television laws and solicited comment from the public last month. On Friday, I submitted a letter encouraging the reform effort. I attached the paper Adam and I wrote last year about the current state of video regulations and the need for eliminating the complex rules for television providers.

As I say in the letter, excerpted below, pay TV (cable, satellite, and telco-provided) is quite competitive, as this chart of pay TV market share illustrates. In addition to pay TV there is broadcast, Netflix, Sling, and other providers. Consumers have many choices and the old industrial policy for mass media encourages rent-seeking and prevents markets from evolving.

Dear Chairman Upton and Chairman Walden:

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the Committee’s December 2014 questions on video regulation.

…The labyrinthine communications and copyright laws governing video distribution are now distorting the market and therefore should be made rational. Congress should avoid favoring some distributors at the expense of free competition. Instead, policy should encourage new entrants and consumer choice.

The focus of the committee’s white paper on how to “foster” various television distributors, while understandable, was nonetheless misguided. Such an inquiry will likely lead to harmful rules that favor some companies and programmers over others, based on political whims. Congress and the FCC should get out of “fostering” the video distribution markets completely. A light-touch regulatory approach will prevent the damaging effects of lobbying for privilege and will ensure the primacy of consumer choice.

Some of the white paper’s questions may actually lead policy astray. Question 4, for instance, asks how we should “balance consumer welfare and the rights of content creators” in video markets. Congress should not pursue this line of inquiry too far. Just consider an analogous question: how do we balance consumer welfare and the interests of content creators in literature and written content? The answer is plain: we don’t. It’s bizarre to even contemplate.

Congress does not currently regulate the distribution markets of literature and written news and entertainment. Congress simply gives content producers copyright protection, which is generally applicable. The content gets aggregated and distributed on various platforms through private ordering via contract. Congress does not, as in video, attempt to keep competitive parity between competing distributors of written material: the Internet, paperback publishers, magazine publishers, books on tape, newsstands, and the like. Likewise, Congress should forego any attempt at “balancing” in video content markets. Instead, eliminate top-down communications laws in favor of generally applicable copyright laws, antitrust laws, and consumer protection laws.

As our paper shows, the video distribution marketplace has changed drastically. From the 1950s to the 1990s, cable was essentially consumers’ only option for pay TV. Those days are long gone, and consumers now have several television distributors and substitutes to choose from. From close to 100 percent market share of the pay TV market in the early 1990s, cable now has about 50 percent of the market. Consumers can choose popular alternatives like satellite- and telco-provided television as well as smaller players like wireless carriers, online video distributors (such as Netflix and Sling), wireless Internet service providers (WISPs), and multichannel video and data distribution service (MVDDS or “wireless cable”). As many consumers find Internet over-the-top television adequate, and pay TV an unnecessary expense, “free” broadcast television is also finding new life as a distributor.

The New York Times reported this month that “[t]elevision executives said they could not remember a time when the competition for breakthrough concepts and creative talent was fiercer” (“Aiming to Break Out in a Crowded TV Landscape,” January 11, 2015). As media critics will attest, we are living in the golden age of television. Content is abundant and Congress should quietly exit the “fostering competition” game. Whether this competition in television markets came about because of FCC policy or in spite of it (likely both), the future of television looks bright, and the old classifications no longer apply. In fact, the old “silo” classifications stand in the way of new business models and consumer choice.

Therefore, Congress should (1) merge the FCC’s responsibilities with the Federal Trade Commission or (2) abolish the FCC’s authority over video markets entirely and rely on antitrust agencies and consumer protection laws in television markets. New Zealand, the Netherlands, Denmark, and other countries have merged competition and telecommunications regulators. Agency merger streamlines competition analyses and prevents duplicative oversight.

Finally, instead of fostering favored distribution channels, Congress’ efforts are better spent on reforms that make it easier for new entrants to build distribution infrastructure. Such reforms increase jobs, increase competition, expand consumer choice, and lower consumer prices.

Thank you for initiating the discussion about updating the Communications Act. Reform can give America’s innovative telecommunications and mass-media sectors a predictable and technology neutral legal framework. When Congress replaces industrial planning in video with market forces, consumers will be the primary beneficiaries.

Sincerely,

Brent Skorup

Research Fellow, Technology Policy Program

Mercatus Center at George Mason University

January 20, 2015

The government sucks at cybersecurity

Originally posted at Medium.

The federal government is not about to allow last year’s rash of high-profile security failures of private systems like Home Depot, JP Morgan, and Sony Entertainment to go to waste without expanding its influence over digital activities.

Last week, President Obama proposed a new round of cybersecurity policies that would, among other things, compel private organizations to share more sensitive information about information security incidents with the Department of Homeland Security. This endeavor to revive the spirit of CISPA is only the most recent in a long line of government attempts to nationalize and influence private cybersecurity practices.

But the federal government is one of the last organizations that we should turn to for advice on how to improve cybersecurity policy.

Don’t let policymakers’ talk of getting tough on cybercrime fool you. Their own network security is embarrassing to the point of parody and has been getting worse for years despite spending billions of dollars on the problem.

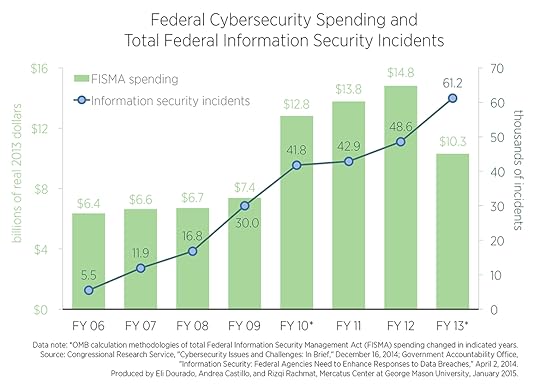

The chart above comes from a new analysis on federal information security incidents and cybersecurity spending by me and my colleague Eli Dourado at the Mercatus Center.

The chart uses data from the Congressional Research Service and the Government Accountability Office to display total federal cybersecurity spending required by the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 displayed by the green bars and measured on the left-hand axis along with the total number of reported information security incidents of federal systems displayed by the blue line and measured by the right-hand axis from 2006 to 2013. The chart shows that the number of federal cybersecurity failures has increased every year since 2006, even as investments in cybersecurity processes and systems have increased considerably.

In 2002, the federal government created an explicit goal for itself to modernize and strengthen its cybersecurity infrastructure by the end of that decade with the passage of the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA). FISMA required agency leaders to develop and implement information security protections with the guidance of offices like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—some of the same organizations tasked with coordinating information-sharing about cybersecurity threats with the private sector in Obama’s proposal, by the way—and authorized robust federal investments in IT infrastructure to meet these goals.

The chart is striking, but a quick data note on the spending numbers is in order. Both the dramatic increase in FISMA spending from $7.4 billion in FY 2009 to $12.8 billion in FY 2010 and the dramatic decrease in FISMA spending from $14.8 billion in FY 2012 to $10.3 billion in FY 2013 are partially attributable to OMB’s decision to change its FISMA spending calculation methodology in those years.

Even with this caveat on inter-year spending comparisons, the chart shows that the federal government has invested billions of dollars to improve its internal cybersecurity defenses in recent years. Altogether, the OMB reports that the federal government spent $78.8 billion on FISMA cybersecurity investments from FY 2006 to FY 2013.

(And this is just cybersecurity spending authorized through FISMA. When added to the various other authorizations on cybersecurity spending tucked in other federal programs, the breadth of federal spending on IT preparedness becomes staggering indeed.)

However, increased federal spending on cybersecurity is not reflected in the rate of cyberbreaches of federal systems reported by the GAO. The number of reported federal cybersecurity incidents increased by an astounding 1012% over the selected years, from 5,503 in 2006 to 61,214 in 2013.

Yes, 1012%. That’s not a typo.

What’s worse, a growing number of these federal cybersecurity failures involve the potential exposure of personally identifiable information—private data about individuals’ contact information, addresses, and even Social Security numbers and financial accounts.

The second chart displays the proportion of all reported federal information security incidents that involved the exposure of personally identifiable information from 2009 to 2013. By 2013, over 40 percent of all reported cybersecurity failures involved the potential exposure of private data to outside groups.

It is hard to argue that these failures stem from lack of adequate security investments. This is as much a problem of scale as it is of an inability to follow one’s own directions. In fact, the government’s own Government Accountability Office has been sounding the alarm about poor information security practices since 1997. After FISMA was implemented to address the problem, government employees promptly proceeding to ignore or undermine the provisions that would improve security—rendering the “solution” merely another checkbox on the bureaucrat’s list of meaningless tasks.

The GAO reported in April of 2014 that federal agencies systematically fail to meet federal security standards due to poor implementation of key FISMA practices outlined by the OMB, NIST, and DHS. After more than a decade of billion dollar investments and government-wide information sharing, in 2013 “inspectors general at 21 of the 24 agencies cited information security as a major management challenge for their agency, and 18 agencies reported that information security control deficiencies were either a material weakness or significant deficiency in internal controls over financial reporting.”

This weekend’s POLITICO report on lax federal security practices makes it easy to see how ISIS could hack into the CENTCOM Twitter account:

Most of the staffers interviewed had emailed security passwords to a colleague or to themselves for convenience. Plenty of offices stored a list of passwords for communal accounts like social media in a shared drive or Google doc. Most said they individually didn’t think about cybersecurity on a regular basis, despite each one working in an office that dealt with cyber or technology issues. Most kept their personal email open throughout the day. Some were able to download software from the Internet onto their computers. Few could remember any kind of IT security training, and if they did, it wasn’t taken seriously.

“It’s amazing we weren’t terribly hacked, now that I’m thinking back on it,” said one staffer who departed the Senate late this fall. “It’s amazing that we have the same password for everything [like social media.]”

Amazing, indeed.

What’s also amazing is the gall that the federal government has in attempting to butt its way into assuming more power over cybersecurity policy when it can’t even get its own house in order.

While cybersecurity vulnerabilities and data breaches remain a considerable problem in the private sector as well as the public sector, policies that failed to protect the federal government’s own information security are unlikely to magically work when applied to private industry. The federal government’s own poor track record of increasing data breaches and exposures of personally identifiable information render its systems a dubious safehouse for the huge amounts of sensitive data affected by the proposed legislation.

President Obama is expected to make cybersecurity policy a key platform issue in tonight’s State of the Union address. Given his own shop’s pathetic track record in protecting its own network security, one has to ponder the efficacy and reasoning in his intentions. The federal government should focus on properly securing its own IT systems before trying to expand its control over private systems.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower