Adam Thierer's Blog, page 35

April 1, 2016

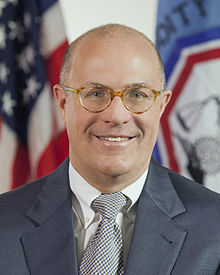

CFTC’s Giancarlo on Permissionless Innovation for the Blockchain

U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Commissioner J. Christopher Giancarlo delivered an amazing address this week before the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation 2016 Blockchain Symposium. The title of his speech was “Regulators and the Blockchain: First, Do No Harm,” and it will go down as the definitive early statement about how policymakers can apply a principled, innovation-enhancing policy paradigm to distributed ledger technology (DLT) or “blockchain” applications.

U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Commissioner J. Christopher Giancarlo delivered an amazing address this week before the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation 2016 Blockchain Symposium. The title of his speech was “Regulators and the Blockchain: First, Do No Harm,” and it will go down as the definitive early statement about how policymakers can apply a principled, innovation-enhancing policy paradigm to distributed ledger technology (DLT) or “blockchain” applications.

“The potential applications of this technology are being widely imagined and explored in ways that will benefit market participants, consumers and governments alike,” Giancarlo noted in his address. But in order for that to happen, he said, we have to get policy right. “It is time again to remind regulators to ‘do no harm,'” he argued, and he continued on to note that

The United States’ global leadership in technological innovation of the Internet was built hand-in-hand with its enlightened “do no harm” regulatory framework. Yet, when the Internet developed in the mid-1990s, none of us could have imagined its capabilities that we take for granted today. Fortunately, policymakers had the foresight to create a regulatory environment that served as a catalyst rather than a choke point for innovation. Thanks to their forethought and restraint, Internet-based applications have revolutionized nearly every aspect of human life, created millions of jobs and increased productivity and consumer choice. Regulators must show that same forethought and restraint now [for the blockchain].

What Giancarlo is referring to is the approach that the U.S. government adopted toward the Internet and digital networks in the mid-1990s. You can think of this vision as “permissionless innovation.” As I explain in my recent book of the same title, permissionless innovation refers to the notion that we should generally be free to experiment and learn new and better ways of doing things through ongoing trial-and-error.

How did U.S. policymakers make permissionless innovation the cornerstone of Internet policy during the mid-1990s? In my book, I highlight several key policy decisions, but the most crucial moment came with the Clinton Administration’s 1997 publication of Framework for Global Electronic Commerce in July 1997. As I have noted here many times before, the document was a succinct and principled vision statement that made the idea of permissionless innovation the cornerstone of Internet policy for America. The five principles at the heart of this beautiful Framework were:

1. The private sector should lead. The Internet should develop as a market driven arena not a regulated industry. Even where collective action is necessary, governments should encourage industry self-regulation and private sector leadership where possible.

2. Governments should avoid undue restrictions on electronic commerce. In general, parties should be able to enter into legitimate agreements to buy and sell products and services across the Internet with minimal government involvement or intervention. Governments should refrain from imposing new and unnecessary regulations, bureaucratic procedures or new taxes and tariffs on commercial activities that take place via the Internet.

3. Where governmental involvement is needed, its aim should be to support and enforce a predictable, minimalist, consistent and simple legal environment for commerce. Where government intervention is necessary, its role should be to ensure competition, protect intellectual property and privacy, prevent fraud, foster transparency, and facilitate dispute resolution, not to regulate.

4. Governments should recognize the unique qualities of the Internet. The genius and explosive success of the Internet can be attributed in part to its decentralized nature and to its tradition of bottom-up governance. Accordingly, the regulatory frameworks established over the past 60 years for telecommunication, radio and television may not fit the Internet. Existing laws and regulations that may hinder electronic commerce should be reviewed and revised or eliminated to reflect the needs of the new electronic age.

5. Electronic commerce on the Internet should be facilitated on a global basis. The Internet is a global marketplace. The legal framework supporting commercial transactions should be consistent and predictable regardless of the jurisdiction in which a particular buyer and seller reside.

It was and remains a near-perfect vision for how emerging technologies should be governed because, as I note in my book, it “gave innovators the green light to let their minds run wild and experiment with an endless array of exciting new devices and services.”

Commissioner Giancarlo agrees, noting of the Framework that, “This model is well-recognized as the enlightened regulatory underpinning of the Internet that brought about profound changes to human society. … During the period of this “do no harm” regulatory framework, a massive amount of investment was made in the Internet’s infrastructure. It yielded a rapid expansion in access that supported swift deployment and mass adoption of Internet-based technologies.” And countless new exciting systems, devices, and applications came about, which none of us could have anticipated until we let people experiment freely.

By extension, we should apply the “do no harm” / permissionless innovation policy paradigm more broadly, Giancarlo says.

‘Do no harm’ was unquestionably the right approach to development of the Internet. Similarly, “do no harm” is the right approach for DLT. Once again, the private sector must lead and regulators must avoid impeding innovation and investment and provide a predictable, consistent and straightforward legal environment. Protracted regulatory uncertainty or an uncoordinated regulatory approach must be avoided, as should rigid application of existing rules designed for a bygone technological era. . . . I believe that innovators and investors should not have to seek government’s permission, only its forbearance, to develop DLT so they can do the work necessary to address the increased operational complexity and capital consumption of modern financial market regulation.

And if America fails to adopt this approach for the Blockchain, it could be disastrous. “Without such a “do no harm” approach,” Giancarlo predicts, “financial service and technology firms will be left trying to navigate a complex regulatory environment, where multiple agencies have their own rule frameworks, issues and concerns.” And that led Giancarlo to touch upon an issue I have discussed here many times before: The growing reality of a world of “global innovation arbitrage.” As I noted in an essay on that topic, “Capital moves like quicksilver around the globe today as investors and entrepreneurs look for more hospitable tax and regulatory environments. The same is increasingly true for innovation. Innovators can, and increasingly will, move to those countries and continents that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.”

This is why it is so crucial that policymakers set the right tone for innovation for blockchain-based technologies and applications. If they don’t, innovators would seek out more hospitable legal environments in which they can innovate without prior restraint. As he ellaborates:

It is therefore critical for regulators to come together to adopt a principles-based approach to DLT regulation that is flexible enough so innovators do not fear unwitting infractions of an uncertain regulatory environment. Some regulators have already openly acknowledged the need for light-touch oversight. For instance, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has committed to regulatory forbearance on DLT development for the foreseeable future in an effort to give innovators “space” to develop and improve the technology. The FCA is even going one step further and engaging in discussions with the industry to determine whether DLT could meet the FCA’s own needs. Similarly, a few weeks ago, Masamichi Kono, Vice Minister for International Affairs at the Japan Financial Services Agency, stated that regulators must take a “pragmatic and flexible approach” to regulation of new technologies so not to stifle innovation.

I have no doubt that the FCA’s intention to give DLT innovators “space” to innovate will be good for DLT research and development. I also suspect that it will be good for the UK’s burgeoning FinTech industry and the jobs it creates across the Atlantic. U.S. lawmakers concerned about the rapid loss of jobs in the U.S. financial service industry, especially in the New York City area, should similarly look to provide “space” to U.S. DLT innovation and entrepreneurship and the well-paying American jobs that will surely follow.

That is exactly right. I just hope other policymakers are listening to this wisdom. The future of blockchain-based innovation depends upon it. America should follow Commissioner Giancarlo’s wise call to adopt permissionless innovation as the policy default for this exciting technology.

Additional Reading:

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom

Embracing a Culture of Permissionless Innovation

“Permissionless Innovation” & the Clash of Visions over Emerging Technologies (SLIDESHOW)

How Attitudes about Risk & Failure Affect Innovation on Either Side of the Atlantic

FTC’s Ohlhausen on Innovation, Prosperity, “Rational Optimism” & Wise Tech Policy

The Innovator’s Defense Fund: What it is and why it’s needed

A Nonpartisan Policy Vision for the Internet of Things

Problems with Precautionary Principle-Minded Tech Regulation & a Federal Robotics Commission

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Genetic Testing Edition

UK Competition & Markets Authority on Online Platform Regulation

March 16, 2016

Assessing Broadband Subsidies and Lifeline Reform

The FCC has signaled that it may vote to overhaul the Lifeline program this month. Today, Lifeline typically provides a $9.25 subsidy for low-income households to purchase landline or mobile telephone service from eligible providers. While Lifeline has problems–hence the bipartisan push for reform–years ago the FCC structured Lifeline in a way that generally improves access and mitigates abuse (the same cannot be said about the three other major universal service programs).

A direct subsidy plus a menu of options is a good way to expand access to low-income people (assuming there are effective anti-fraud procedures). A direct subsidy is more or less how the US and state governments help lower-income families afford products and services like energy, food, housing, and education. For energy bills there’s LIHEAP. For grocery bills there’s SNAP and WIC. For housing, there’s Section 8 vouchers. For higher education, there’s Pell grants.

Programs structured this way make transfers fairly transparent, which makes them an easy target for criticism but also promotes government accountability, and gives low-income households the ability to consume these services according to their preferences. If you want to attend a small Christian college, not a state university, Pell grants enable that. If you want to purchase rice and tomatoes, not bread and apples, SNAP enables that. The alternative, and far more costly, ways to improve consumer access to various services is to subsidize providers, which is basically how Medicare the rural telephone programs operate, or command-and-control industrial policy, like we have for television and much of agriculture.

Because the FCC is maintaining the consumer subsidy and expanding the menu of Lifeline options to include wired broadband, mobile broadband, and wifi devices, there’s much to commend in the proposed reforms.

Lifeline Broadband Subsidies

Ironically, despite tech activist declarations that 10 Mbps is not “real broadband,” the FCC considers 10 Mbps broadband totally adequate as low-income families’ sole connection to the digital world. If the proposals stand, Lifeline subsidies can be used for 10 Mbps wireline and wireless subscriptions.

The confusion about “real broadband” echoed from tech activists, some tech reporting, and a presidential candidate arises because the FCC has at least three different conceptions of “broadband,” essentially based on whatever definition will increase its regulatory control. For Title II purposes, even a mere 1 Mbps is “broadband” because the FCC wants to be inclusive and regulate all providers. For Section 706, defining “broadband” as high as practical increases the agency’s regulatory powers, so it’s not “real broadband” unless it’s 25 Mbps. For universal service and (apparently) Lifeline subsidies, 10 Mbps is “broadband” because setting it too high would be too restrictive for the consumers and carriers who benefit from a moderate standard.

Wireless Substitution

Expanding Lifeline to mobile broadband suggests an increasing awareness by the FCC that, for many Americans, wireless broadband is a substitute for wireline broadband. This is a little surprising because the FCC decided in January 2016 that “fixed and mobile broadband services are not functional substitutes.” The available data, however, shows that wireless is a substitute for the millions of homes that don’t contain avid Netflix watchers. While popular broadband offerings have monthly limits of 300 GB or more, based on Sandvine data, the typical US home with a wired Internet connection probably uses under 30 GB per month.

Pew surveys also reveal many Americans who substitute wireless for wireline. Of those in the growing number of smartphone-only households, 65% said their smartphones allow them to do everything online they need. Note also that, of those with no home broadband connection–which includes smartphone-only households–only 25% are interested in subscribing. This is why it’s good the FCC doesn’t simply subsidize carriers–most nonadopters simply have no interest in home Internet. Certainly there are some in these groups who don’t realize that their lives would be enriched by a wired broadband connection, but that is mainly a question of digital literacy and education.

Concerns and Reforms

While I support the FCC expanding the menu of Lifeline options and improving the eligibility process, I’m wary of some of the proposed reforms. More details will come out later but Commissioner O’Rielly has pointed out several potential problems with the direction this is going. For one, the eligibility process has always been a mess, in part because it’s based on a patchwork of federal and state programs. The largest problem is the FCC is proposing a major increase in the Lifeline budget, which will increase most Americans’ phone bills. Until the FCC gets its Lifeline house in order, it’s premature to increase the fund so substantially.

Further, I’d like to see satellite broadband on the “menu” of options for Lifeline consumers. Based on the preliminary reports, it’s not clear that satellite broadband will be eligible. Satellite broadband satisfies the speed requirement (10 Mbps) but the FCC plans to require a 150 GB allowance for fixed connections. Satellite is considered a fixed connection. However, satellite broadband providers generally have a low data allowance during daytime hours. On the other hand, they often have unmetered, unlimited data in off-peak hours. Arguably, because data is unmetered every day, satellite broadband should qualify. It would give low-income rural households, who have very low Internet penetration, one more option to be connected.

Finally, one possible reform to ensure the truly needy are benefiting would be to simultaneously increase substantially the $9.25 monthly subsidy but disallow subsidies to households with subscription TV. The most recent data I can find is a 2010 FCC report that 80% of Internet non-adopters have satellite or “cable premium” television. Tightening the requirements means fewer households are eligible but it would increase public support for the program and I think the FCC could then afford to be more generous with the Lifeline subsidy.

March 9, 2016

Permissionless Innovation & Cybersecurity: Are They Compatible?

[This is an excerpt from Chapter 6 of the forthcoming 2nd edition of my book, “Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom,” due out later this month. I was presenting on these issues at today’s New America Foundation “Cybersecurity for a New America” event, so I thought I would post this now. To learn more about the contrast between “permissionless innovation” and “precautionary principle” thinking, please consult the earlier edition of my book or see this blog post.]

Viruses, malware, spam, data breeches, and critical system intrusions are just some of the security-related concerns that often motivate precautionary thinking and policy proposals. But as with privacy- and safety-related worries, the panicky rhetoric surrounding these issues is usually unfocused and counterproductive.

In today’s cybersecurity debates, for example, it is not uncommon to hear frequent allusions to the potential for a “digital Pearl Harbor,” a “cyber cold war,” or even a “cyber 9/11.” These analogies are made even though these historical incidents resulted in death and destruction of a sort not comparable to attacks on digital networks. Others refer to “cyber bombs” or technological “time bombs,” even though no one can be “bombed” with binary code. Michael McConnell, a former director of national intelligence, went so far as to say that this “threat is so intrusive, it’s so serious, it could literally suck the life’s blood out of this country.”

Such outrageous statements reflect the frequent use of “threat inflation” rhetoric in debates about online security. Threat inflation has been defined as “the attempt by elites to create concern for a threat that goes beyond the scope and urgency that a disinterested analysis would justify.” Unfortunately, such bombastic rhetoric often conflates minor cybersecurity risks with major ones. For example, dramatic doomsday stories about hackers pushing planes out of the sky misdirects policymakers’ attention from the more immediate, but less gripping, risks of data extraction and foreign surveillance. Well-meaning skeptics might then conclude that our real cybersecurity risks are also not a problem. In the meantime, outdated legislation and inappropriate legal norms continue to impede beneficial defensive measures that could truly improve security.

Meanwhile, similar concerns have already been raised about security vulnerabilities associated with the Internet of Things and driverless cars. Legislation has already been floated to address the latter concern through federal certification standards. More broad-based cybersecurity legislative proposals have also been proposed, most notably the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act, which would extend legal immunity to corporations that share customer data with intelligence agencies.

Ironically, these efforts to expand federal cybersecurity authority come before the federal government has even gotten its own house in order. According to a recent report, federal information security failures had increased by an astounding 1,169 percent, from 5,503 in fiscal year 2006 to 69,851 in fiscal year 2014. Of course, many of these same agencies would be tasked with securing the massive new datasets containing personally identifiable details about US citizens’ online activities that legislation like the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act would authorize. In the worst-case scenario, such federal data storage could counterintuitively encourage more attacks on government systems.

It’s important to put all these security issues in some context and to realize that proposed legal remedies are often inappropriate to address online security concerns and sometimes end up backfiring. In his research on the digital security marketplace, my Mercatus Center colleague Eli Dourado has illustrated how we are already able to achieve “Internet Security without Law.” Dourado documented the many informal institutions that enforce network security norms on the Internet to show how cooperation among a remarkably varied set of actors improves online security without extensive regulation or punishing legal liability. “These informal institutions carry out the functions of a formal legal system—they establish and enforce rules for the prevention, punishment, and redress of cybersecurity-related harms,” Dourado says.

For example, a diverse array of computer security incident response teams (CSIRTs) operate around the globe, sharing their research on and coordinating responses to viruses and other online attacks. Individual Internet service providers (ISPs), domain name registrars, and hosting companies work with these CSIRTs and other individuals and organizations to address security vulnerabilities.

Encouraging the development of robust and lawful software vulnerability markets would provide even more effective cybersecurity reporting. Some private companies and nonprofit security research firms have offered financial incentives for hackers to find and report software vulnerabilities to the proper parties for years now. Such “bug bounty” and “vulnerability auction” programs better align hackers’ monetary incentives with the public interest. By allowing a space for security researchers to responsibly report and profit from discovered bugs, these markets dissuade hackers from selling vulnerabilities to criminal or state-backed organizations.

A growing market for private security consultants and software providers also competes to offer increasingly sophisticated suites of security products for businesses, households, and governments. “Corporations, including software vendors, antimalware makers, ISPs, and major websites such as Facebook and Twitter, are aggressively pursuing cyber criminals,” notes Roger Grimes of Infoworld. “These companies have entire legal teams dedicated to national and international cyber crime. They are also taking down malicious websites and bot-spitting command-and-control servers, along with helping to identify, prosecute, and sue bad guys,” he says. Meanwhile, more organizations are employing “active defense” strategies, which are “countermeasures that entail more than merely hardening one’s own network against threats and instead seek to unmask one’s attacker or disable the attacker’s system.”

A great deal of security knowledge is also “crowd-sourced” today via online discussion forums and security blogs that feature contributions from experts and average users alike. University-based computer science and cyber law centers and experts have also helped by creating projects like Stop Badware, which originated at Harvard University but then grew into a broader nonprofit organization with diverse financial support. Meanwhile, informal grassroots security groups like The Cavalry have formed to build awareness about digital security threats among developers and the general public and then devise solutions to protect public safety.

The recent debacle over the Commerce Department’s proposed new export rules for so-called cyberweapons provides a good example of how poorly considered policies can inadvertently undermine such beneficial emergent ecosystems. The agency’s new draft of US “Wassenaar Arrangement” arms control policies would have unintentionally criminalized the normal communication of basic software bug-testing techniques that hundreds of companies employ each day. The regulators who were drafting the new rules had good intentions. They wanted to crack down on cyber criminals’ abilities to sell malware to hostile state-backed initiatives. However, their lack of technical sophistication led them to unknowingly write a proposal that would have compelled software engineers to seek Commerce Department permission before communicating information about minor software quirks. Fortunately, regulators wisely heeded the many concerned industry comments and rescinded the initial proposal.

Dourado notes that informal, bottom-up efforts to coordinate security responses offer several advantages over top-down government solutions such as administrative regulatory regimes or punishing liability regimes. First, the informal cooperative approach “gives network operators flexibility to determine what constitutes due care in a dynamic environment.” “Formal legal standards,” by contrast, “may not be able to adapt as quickly as needed to rapidly changing circumstances,” he says. Simply put, markets are more nimble than mandates when it comes to promptly patching security vulnerabilities.

Second, Dourado notes that “formal legal proceedings are adversarial and could reduce ISPs’ incentives to share information and cooperate.” Heavy-handed regulation or threatening legal liability schemes could have the unintended consequence of discouraging the sort of cooperation that today alleviates security problems swiftly.

Indeed, there is evidence that existing cybersecurity law prevents defensive strategies that could help organizations to more quickly respond to system infiltrations. For example, some argue that private individuals and organizations should be allowed to defend themselves using special measures to expel or track system infiltrators, often called “hacking back” or “active defense.” Anthony Glosson’s analysis for the Mercatus Center discusses how the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act currently prevents computer security specialists from utilizing defensive hacking techniques that could improve system defenses or decrease the number of attempted attacks.

Third, legal solutions are less effective because “the direct costs of going to court can be substantial, as can be the time associated with a trial,” Dourado argues. By contrast, private actors working cooperatively “do not need to go to court to enforce security norms,” meaning that “security concerns are addressed quickly or punishment . . . is imposed rapidly.” For example, if security warnings don’t work, ISPs can “punish” negligent or willfully insecure networks by “de-peering,” or terminating network interconnection agreements. The very threat of de-peering helps keep network operators on their toes.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Dourado notes that international cooperation between state-based legal systems is limited, complicated, and costly. By contrast, under today’s informal, voluntary approach to online security, international coordination and cooperation are quite strong. The CSIRTs and other security institutions and researchers mentioned above all interact and coordinate today as if national borders did not exist. Territorial legal system and liability regimes don’t have the same advantage; enforcement ends at the border.

Dourado’s model has ramifications for other fields of tech policy. Indeed, as noted above, these collaborative efforts and approaches are already at work in the realms of online safety and digital privacy. Countless organizations and individuals collaborate on educational initiatives to improve online safety and privacy. And many industry and nonprofit groups have established industry best practices and codes of conduct to ensure a safer and more secure online experience for all users. The efforts of the Family Online Safety Institute were discussed above. Another example comes from the Future of Privacy Forum, a privacy think tank that seeks to advance responsible data practices. The think tank helps create codes of conduct to ensure privacy best practices by online operators and also helps highlight programs run by other organizations. Likewise, the National Cyber Security Alliance helps promote Internet safety and security efforts among a variety of companies and coordinates National Cyber Security Awareness Month (every October) and Data Privacy Day (held annually on January 28).

What these efforts prove is that not every complex social problem requires a convoluted legal regime or heavy-handed regulatory response. We can achieve reasonably effective safety and security without layering on more and more law and regulation. Indeed, the Internet and digital systems could arguably be made more secure by reforming outdated legislation that prevents potential security-increasing collaborations. “Dynamic systems are not merely turbulent,” Postrel notes. “They respond to the desire for security; they just don’t do it by stopping experimentation.” She adds, “Left free to innovate and to learn, people find ways to create security for themselves. Those creations, too, are part of dynamic systems. They provide personal and social resilience.”

Education is a crucial part of building resiliency in the security context as well. People and organizations can prepare for potential security problems rationally if given even more information and better tools to secure their digital systems and to understand how to cope when problems arise. Again, many corporations and organizations already take steps to guard against malware and other types of cyberattacks by offering customers free (or cheap) security software. For example, major broadband operators offer free antivirus software to customers and various parental control tools to parents. In the context of “connected car” technology, automakers have banded together to come up with privacy and security best practices to address worries about remote hacking of cars as well as concerns about how much data they collect about our driving habits.

Thus, although it is certainly true that “more could be done” to secure networks and critical systems, panic is unwarranted because much is already being done to harden systems and educate the public about risks. Various digital attacks will continue, but consumers, companies, and others organizations are learning to cope and become more resilient in the face of those threats through creative “bottom-up” solutions instead of innovation-limiting “top-down” regulatory approaches.

This section partially adapted from Adam Thierer, “Achieving Internet Order without Law,” Forbes, June 24, 2012, http://www.forbes.com/sites/adamthier.... The author wishes to thank Andrea Castillo for major contributions to this section.

See Richard A. Serrano, “Cyber Attacks Seen as a Growing Threat,” Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2011, A18. (“[T]he potential for the next Pearl Harbor could very well be a cyber attack.”)

Harry Raduege, “Deterring Attackers in Cyberspace,” The Hill, September 23, 2011, 11, http://thehill.com/opinion/op-ed/1834....

Kurt Nimmo, “Former CIA Official Predicts Cyber 9/11,” InfoWars.com, August 4, 2011, http://www.infowars.com/former-cia-of....

Rodney Brown, “Cyber Bombs: Data-Security Sector Hopes Adoption Won’t Require a ‘Pearl Harbor’ Moment,” Innovation Report, October 26, 2011, 10, http://digital.masshightech.com/launc... Craig Spiezle, “Defusing the Internet of Things Time Bomb,” TechCrunch, August 11, 2015, http://techcrunch.com/2015/08/10/defu....

“Morning Edition: Cybersecurity Bill: Vital Need or Just More Rules?” NPR, March 22, 2012, http://www.npr.org/templates/transcri....

Jerry Brito and Tate Watkins, “Loving the Cyber Bomb? The Dangers of Threat Inflation in Cybersecurity Policy” (Mercatus Working Paper No. 11-24, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, 2011).

Jane K. Cramer and A. Trevor Thrall, “Introduction: Understanding Threat Inflation,” in American Foreign Policy and the Politics of Fear: Threat Inflation Since 9/11, ed. A. Trevor Thrall and Jane K. Cramer (London: Routledge, 2009), 1.

Tufekci, “Dumb Idea”; Byron Acohido, “Hackers Take Control of Internet Appliances,” USA Today, October 15, 2013, http://www.usatoday.com/story/cybertr....

Ed Markey, Tracking & Hacking: Security & Privacy Gaps Put American Drivers at Risk, US Senate, February 2015, http://www.markey.senate.gov/imo/medi....

Ed Markey, “Markey, Blumenthal to Introduce Legislation to Protect Drivers from Auto Security and Privacy Vulnerabilities with Standards and ‘Cyber Dashboard,’” press release, February 11, 2015, http://www.markey.senate.gov/news/pre....

Andrea Castillo, “How CISA Threatens Both Privacy and Cybersecurity,” Reason, May 10, 2015, https://reason.com/archives/2015/05/1....

Eli Dourado and Andrea Castillo, “Poor Federal Cybersecurity Reveals Weakness of Technocratic Approach” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, June 22, 2015), http://mercatus.org/publication/poor-....

Eli Dourado, “Internet Security without Law: How Security Providers Create Online Order” (Mercatus Working Paper No. 12-19, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, June 19, 2012), http://mercatus.org/publication/inter....

Ibid.

Charlie Miller, “The Legitimate Vulnerability Market: Inside the Secretive World of 0-day Exploit Sales,” Independent Security Evaluators, May 6, 2007, http://www.econinfosec.org/archive/we....

Andrea Castillo, “The Economics of Software-Vulnerability Sales: Can the Feds Encourage ‘Pro-social’ Hacking?” Reason, August 11, 2015, https://reason.com/archives/2015/08/1....

Roger Grimes, “The Cyber Crime Tide Is Turning,” Infoworld, August 9, 2011, http://www.pcworld.com/article/237647....

Dourado, “Internet Security.”

Anthony D. Glosson, “Active Defense: An Overview of the Debate and a Way Forward,” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, August 10, 2015), http://mercatus.org/publication/activ....

https://www.iamthecavalry.org.

Andrea Castillo, “The Government’s Latest Attempt to Stop Hackers Will Only Make Cybersecurity Worse,” Reason, July 28, 2015, https://reason.com/archives/2015/07/2....

Russell Brandom, “The US is Rewriting its Controversial Zero-Day Export Policy,” The Verge, July 29, 2015, http://www.theverge.com/2015/7/29/9068665/wassenaar-export-zero-day-revisions-department-of-commerce.

Dourado, “Internet Security.”

Ibid.

Glosson, “Active Defense.”

Dourado, “Internet Security.”

Dourado, “Internet Security.”

Future of Privacy Forum, “Best Practices,” http://www.futureofprivacy.org/resour....

See http://www.staysafeonline.org/ncsam and http://www.staysafeonline.org/data-pr....

Glosson, “Active Defense,” 22. (“The precautionary principle is especially inadvisable in the dynamic realm of tech policy, and until the ostensible harms of active defense materialize, the law should facilitate maximum innovation in the network security field.”)

Postrel, Future and Its Enemies, at 199.

Ibid., 202.

See Future of Privacy Forum, “Connected Cars Project,” accessed October 16, 2015, http://www.futureofprivacy.org/connec... Auto Alliance, “Automakers Believe That Strong Consumer Data Privacy Protections Are Essential to Maintaining the Trust of Our Customers,” accessed October 16, 2015, http://www.autoalliance.org/automotiv.... See also Future of Privacy Forum, “Comments of the Future of Privacy Forum on Connected Smart Technologies in Advance of the FTC ‘Internet of Things’ Workshop,” May 31, 2013, http://www.futureofprivacy.org/wp-con....

Adam Thierer, “Don’t Panic over Looming Cybersecurity Threats,” Forbes, August 7, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/adamthier....

March 7, 2016

Court Stay Signals Loss for FCC on Prison Payphone Reform

This article originally appeared at techfreedom.org.

Today, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals stayed, for the second time, an FCC Order attempting to lower prison payphone phone calling rates. Back in 2003, Martha Wright had petitioned the FCC for relief, citing the exorbitant rates she was charged to call her incarcerated grandson. Finally, in 2012, the FCC sought comment on proposed price caps. In 2013, when Commissioner Mignon Clyburn took over as acting chairman, she rushed through an orderthat implemented rate-of-return regulation, a different approach on which the FCC had not yet sought public comment.

“Once again, the D.C. Circuit has reminded the FCC that good intentions are not enough,” said Berin Szoka, President of TechFreedom. “The FCC must follow basic requirements of administrative law. When it fails to do so, all its talk of protecting consumers is just that: empty talk.”

When the FCC issued its 2013 order, TechFreedom issued the following statement:

If justice delayed is justice denied, the FCC has once again denied justice to the millions of Americans and their families who pay far too much for prison payphone calls. The FCC’s elaborate system of price controls was not among the ideas on which the FCC sought comment last December, nor is it supported by the record. Thus, today’s long-overdue order will very likely be struck down in court — and the Commission will have wasted nine years sitting on Martha Wright’s 2003 payphone justice petition, nine months proposing an illegal solution, and who-knows-how-long litigating about it — only to wind up right back where we started, with payphone operators paying up to two-thirds of their revenue in kickbacks to state prisons, in exchange for the monopoly privilege of gouging a truly captive audience.

This is just the latest example of the FCC’s M.O. of “Ready, Fire, Aim.” The FCC consistently dawdles, then suddenly works itself up into a rush to regulate in ways that are either illegal or unwise — and usually both. Once again, good intentions, the desire to make headlines, disregard for basic principles of legal process, and a deep-seated ideological preference for returning to rate-of-return price controls, have triumphed over common sense, due process and, sadly, actually helping anyone.

In January 2014, the appeals court stayed key provisions of the order. The FCC then went back to the drawing board and, in October 2015, issued a second report and order and third NPRM that, among other things, established price caps for inmate calling services. Affected service providers challenged the order and sought a stay from the D.C. Circuit, which is granted only if, as the court said here, “petitioners have satisfied the stringent requirements for a stay pending court review,” which means showing a strong likelihood of success on the merits.

“The stay issued by the D.C. Circuit isn’t a certain death knell for the inmate calling order, but it certainly casts a grim pall over the order’s future,” said Tom Struble, Policy Counsel at TechFreedom. “This FCC has proven more than willing to tout noble goals to justify its procedural shortfalls, but the courts are less willing to bless such an outcome-driven approach. The rules for administrative procedure are there for a reason, and agencies can’t simply disregard them when it suits their interests. If something is worth doing, they should take the time to do it right.”

“It’s worth noting that Judge Tatel was among the three judges voting for today’s stay,” concluded Szoka, noting that Tatel also sits on the D.C. Circuit panel hearing challenges to the FCC’s Open Internet Order. “Even though today’s stay order addresses unrelated issues, it may suggest that the D.C. Circuit is taking a harsher look at the FCC’s procedure, and while the court didn’t grant an initial stay in the challenge to the Open Internet Order, the FCC could still lose on the merits of that case when it comes to the threshold question of whether it provided adequate notice of Title II reclassification, and rules that went well beyond ‘net neutrality.’ If so, the court might simply kick the matter back to the FCC and set the stage for a fourth court battle over the key legal questions. It’s anyone’s bet as to which issue, prison payphones (started in 2003) or net neutrality (started in 2005) the FCC will actually manage to resolve first, after more than a decade of heated fulmination exceeded only by the FCC’s incompetence.”

Apple eBooks Case: Supreme Court Refuses to Defend Permissionless Innovation

This article originally appeared at techfreedom.org.

Today, the Supreme Court declined to review a Second Circuit decision that held Apple violated the antitrust laws by fixing ebook prices when, in preparing to launch its own iBookstore, it negotiated a deal with publishers that would allow them to set prices above Amazon’s one-size-fits-all $9.99 price. The appeals court reached its decision by applying the strict per se rule, which ignores any procompetitive justifications of a challenged business practice. The dissent had argued that Apple “was unwilling to [enter the ebook market] on terms that would incur a loss on e-book sales (as would happen if it met Amazon’s below-cost price),” and thus that Apple’s agreement with major publishers actually benefitted consumers by facilitating competition in the ebooks market, even if it meant higher prices for some ebooks.

The Supreme Court’s refusal to hear the case means the 2013 verdict against Apple, resulting in a $450 million dollar class-action settlement, will stand. The case began in 2010 when Apple negotiated with five major publishers, adopting an agency pricing model in which the publishers set a book’s price and gave a sales commission to Apple. This pricing model is distinct from Amazon’s previously dominant model, where t was allowed to unilaterally set e-book prices — often for below cost as a loss leader strategy to encourage sales of its own Kindle reader and promote the overall Amazon platform. The Justice Department claimed that Apple’s agency model amounted to antitrust conspiracy — and the Second Circuit agreed. Meanwhile, Apple’s entry reduced Amazon’s share of the ebooks market from 90% to 60%.

“The question here wasn’t actually whether Apple should win, but whether Apple should even be allowed to argue that its arrangement could benefit consumers,” said TechFreedom President Berin Szoka. “Apple made a strong case that its deal with publishers was critical to allowing it compete with Amazon. The Supreme Court might or might not have found those arguments convincing, but it should have at least weighed them under antitrust’s flexible rule of reason. By letting the rigid per se deal stand as the controlling legal standard, the Court has ensured that antitrust law in general will put obsolete legal precedents from the pre-digital era above consumer welfare.”

“Business model innovation is no less essential for progress than technological innovation,” concluded Szoka. “Indeed, the two usually go hand in hand. And new business models are usually essential to unseating the first mover in new markets like ebook publishing, especially when the first mover sets artificially low prices. Categorically banning deals that attempt to rebalance pricing power between distributors and publishers in multi-sided markets likely means strangling competition in its crib. Unfortunately, the real costs of today’s decision will go unseen: without an opportunity to defend new business models, innovative companies like Apple will be less likely to attempt to disrupt the dominance of entrenched incumbents. Consumers will simply never know how much today’s decision cost them.”

Read more about the argument for reversing the Second Circuit and applying a rule of reason to novel business arrangements in the amicus brief filed by the International Center for Law & Economics and eleven leading antitrust scholars. Truth on the Market, a blog dedicated to law and economics, held ablog symposium on the case last month.

March 1, 2016

A Section 230 for the “Makers” Movement

The success of the Internet and the modern digital economy was due to its open, generative nature, driven by the ethos of “permissionless innovation.” A “light-touch” policy regime helped make this possible. Of particular legal importance was the immunization of online intermediaries from punishing forms of liability associated with the actions of third parties.

As “software eats the world” and the digital revolution extends its reach to the physical world, policymakers should extend similar legal protections to other “generative” tools and platforms, such as robotics, 3D printing, and virtual reality.

In other words, we need a Section 230 for the “maker” movement.

The Internet’s Most Important Law

Today’s vibrant Internet ecosystem likely would not exist without “Section 230” (47 U.S.C. § 230) of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. That law, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary, immunized online intermediaries from onerous civil liability for the content and communications that travelled over their electronic networks.

The immunities granted by Section 230 let online speech and commerce flow freely, without the constant threat of legal action or onerous liability looming overhead for digital platforms. Without the law, many of today’s most popular online sites and services might have been hit with huge lawsuits for the content and commerce that some didn’t approve of on their platforms. It is unlikely that as many of them would have survived if not for Section 230’s protections.

For example, sites such as eBay, Facebook, Wikipedia, Angie’s List, Yelp, and YouTube all depend on Section 230 immunities to shield them from potentially punishing liability for the content that average Americans post to those sites. But Section 230 protects countless small sites and services just as much as those larger platforms and it has been an extraordinary boon to online commerce and speech.

Extending Immunities to Other General-Purpose Technologies: 3 Models

To foster generativity and permissionless innovation for the next wave of tech entrepreneurs, it may be necessary to immunize some intermediaries (i.e., platform providers or device manufacturers) from punishing forms of liability, or at least to limit liability in some fashion to avoid the chilling effect that excessive litigation can have on life-enriching innovation. Specifically, they should be immunized from liability associated with the ways third-parties use their platforms or devices to speak, experiment, or innovate.

“The past ten years have been about discovering new ways to create, invent, and work together on the Web,” noted Chris Anderson in his book Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. “The next ten years will be about applying those lessons to the real world.” But that can only happen if we get public policy right.

Thus, the creators of newer general-purpose technologies may need to receive certain limited immunizations from liability for the ways third-parties use their devices. If troublemakers use general-purpose technologies to do harm—i.e., cybersecurity violations, privacy invasions, copyright infringement, etc.—it is almost always more sensible to hold those problematic users directly accountable for their actions.

The other approach—holding those intermediaries accountable for the actions of third parties—will discourage innovators from creating vibrant, open platforms and devices that could facilitate new types of speech and commerce. Therefore, an embrace of permissionless innovation requires a rejection of such middleman deputization schemes.

There are three different existing immunity models we might consider applying to emerging general-purpose technologies.

Model #1: Section 230 & online services

The first model, of course, is Section 230 itself. Section 230 stipulated that it is the policy of the United States “to promote the continued development of the Internet and other interactive computer services and other interactive media,” and “to preserve the vibrant and competitive free market that presently exists for the Internet and other interactive computer services, unfettered by Federal or State regulation.” To accomplish that, the law made it clear that, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

Since implementation of Section 230 two decades ago, courts have generally read this immunity fairly broadly, so much so that some critics have argued that 230’s scope has been enlarged well beyond congressional intent. Even if that is true, I believe that has been a net positive (excuse the pun) and that it is not only wise to preserve that sweeping immunity but extend it to other technologies and sectors.

Model #2: Firearm manufacturing

Another immunization model can be found in the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act of 2005 (Pub. L. No. 109-92, 119 Stat. 2095). Although “lawsuits alleging negligent distribution plagued the firearm industry until 2005,” the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act “effectively ended the ‘gun tort’ era,” notes Peter Jensen-Haxel. The law did so by granting gun manufacturers immunities for such legal actions. (It would seem that, by extension, those who use 3D printers to create firearms will also be immunized from civil actions.)

Importantly, unlike Section 230, which provided broad immunity by default to all online platforms, the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act applied to manufactures/sellers that fit into the certain qualifications (i.e., they get immunity if they comply with certain licensing rules, record keeping requirements, etc.). This tension between broad versus targeted immunity will become the subject of debate for emerging general-purpose technologies as scholars and policymakers contemplate optimal default liability rules.

Model #3: Vaccines

A final legal immunization model comes, ironically, from the world of medical immunizations. As part of the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 (42 U.S.C. §§ 300aa-1 to 300aa-34), Congress created The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, “after lawsuits against vaccine companies and health care providers threatened to cause vaccine shortages and reduce U.S. vaccination rates, which could have caused a resurgence of vaccine preventable diseases.”

As described by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the program, “is a no-fault alternative to the traditional legal system for resolving vaccine injury petitions.” Thus, those suffering injuries from vaccines are able to seek compensation from this program instead of having to sue vaccine companies.

As Avery Johnson of the Wall Street Journal noted in 2009 article about the program, “A spate of lawsuits against vaccine makers in the 1970s and 1980s had caused dozens of companies to get out of the low-profit business, creating a public-health scare. The strategy worked and the public health implications have been sizable. Vaccines have driven huge reductions — and in the case of smallpox, for instance, complete eradications — of major childhood diseases.”

This model is obviously very different than Section 230 and the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act in that it includes a government-created compensation fund provided as an alternative to civil lawsuit remedies. In all likelihood, such a compensation fund would not be necessary for new general-purpose “maker” technologies or sectors.

Nonetheless, this model could, perhaps, have some relevance for certain narrow classes of those technologies. For example, 3D-printed medical devices might be one area where it would make sense to exempt from liability the creators of 3D printers and the platforms over which 3D printer blueprints are distributed. But if there is significant resulting harm from some of those devices or plans, it remains unclear how compensation would work and who would be picking up the tab for it. The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program offers one potential answer, although it may not be wise to craft such a consumer-funded or taxpayer-supported program for other reasons. Even if creating a government-run compensation fund was eventually seen as a good idea, we cannot determine how big the fund should be until some actual harms occur.

Three Sectors to Cover

Next, we should consider which sectors or technologies should be eligible for such immunities.

I wish it was possible to craft some sort of “General-Purpose Technology Immunization Act” that would shield such platforms and technologies from onerous liability associated with third-party uses. Realistically, however, it is not likely such a broad-based regime could achieve political traction. There would just be too many opposing forces. Moreover, there may be some unique distinctions between technologies and sectors which necessitate specialized legal regimes.

In any event, I believe a good case can be made for adopting some sort of legal immunity regime for three specific technologies: Robotics, 3D printing, and immersive technology (i.e., virtual reality and augmented reality).

Robotics

Ryan Calo, professor of law at the University of Washington School of Law, has done important work on the law of robotics and he has suggested that such legal immunities may need to be extended to this field. In his 2011 Maryland Law Review article on “Open Robotics,” Calo made his case as follows:

To preempt a clampdown on robot functionality, Congress should consider immunizing manufacturers of open robotic platforms from lawsuits for the repercussions of leaving robots open. Specifically, consumers and other injured parties should not be able to sue roboticists, much less recover damages, where the injury resulted from one of the following: (1) the use to which the consumer decided to put the robot, no matter how tame or mundane; (2) the nonproprietary software the consumer decided to run on the robot; or (3) the consumer’s decision to alter the robot physically by adding or changing hardware. This immunity would include lawful and unlawful uses of the robot. (p. 134)

. . .

The immunity I propose is selective: Manufacturers of open robots would not escape liability altogether. For instance, if the consumer runs the manufacturer’s software and the hardware remains unmodified, or if it can be shown that the damage at issue was caused entirely by negligent platform design, then recovery should be possible. The immunity I propose only applies in those instances where it is clear that the robot was under the control of the consumer, a third party software, or otherwise the result of end-user modification. Because this issue will not always be easy to prove, we should expect litigation at the margins. I am thus arguing for a compromise position: A presumption against suit unless the plaintiff can show the problem was clearly related to the platform’s design. (p. 136)

I find this entirely convincing and I also believe Calo is wise to begin with robotics as the first target for such legal immunization because such technologies are already being widely manufactured and deployed today.

These liability questions are already being widely debated, for example, in the field of autonomous systems and driverless cars in particular. I’d like to believe that the common law would sort out these things fairly quickly and that an efficient liability regime would emerge from autonomous technologies in short order.

Alas, because America lacks a “loser pays” rule, a perverse incentive exists for overly-zealous trial lawyers to file an avalanche of lawsuits at the first sign of any problem. This could significantly hamper the development of autonomous technologies, which have the potential to immediately decrease the staggering death toll associated with human error behind the wheel. Therefore, it may be necessary for Congress to craft some sort of limited immunity regime for autonomous technology makers to ensure that the development of these potential life-saving technologies is not discouraged by the looming threat of perpetual litigation.

3D Printing

3D printing would be my second choice for a general-purpose technology that should be covered by some sort of intermediary immunity model.

In a forthcoming law review article for the Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology, Adam Marcus and I argue that “the manufacturers of 3D printing devices and the website operators hosting blueprints for 3D-printed objects may need to be protected from liability to avoid chilling innovation. In this sense, a ‘Section 230 for 3D printing’ might be needed.”

We discuss three specific ways that 3D printers could be used by third-parties in such a way that existing laws or regulations are implicated and someone might seek to bring action against the manufacturers of 3D printers or 3D printing marketplaces, like Shapeways or Thingiverse. These cases involve things like 3D-printed prosthetics, which could raise policy concerns at the Food and Drug Administration, and 3D-printed toys or sculptures, which could present intellectual property issues.

But perhaps the most interesting case study for liability purposes will be 3D-printed firearms, which are already raising a great deal of controversy. Marcus and I argue, once again, that “the proper focus of regulation should remain on the user and uses of firearms, regardless of how they are manufactured.” And because, as already noted, the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act immunizes gun manufacturers from legal liability for third-party actions, it would seem logical that the law’s protections would extend to 3D-printed firearms. Moreover, Section 230 itself (and perhaps also the First Amendment) might also apply to 3D printing design schematics that appear on various websites or 3D printing marketplaces.

Generally speaking, Marcus and I argue, “imposing liability on third parties—sites hosting schematics, search engines, and manufacturers of devices—seems neither workable nor wise. There exists a broad spectrum of general-purpose technologies that can be used to facilitate criminal activity,” we note, such as cars, computers, or paper printers. But we don’t blame those intermediaries when those technologies are used by third parties in criminal acts. The same principle should apply to 3D printers.

Immersive Technology

A final sector we might eventually want to apply some sort of intermediary immunity model to is immersive technology. “Immersive technology” refers to services that currently utilize wearable devices (such as a head-mounted display or headset) to let users explore virtual worlds, virtual objects, or hologram-like projections. Immersive technology can be separated into two different, but related groups: virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR).

These technologies are still in the cradle, but many companies are already developing VR and AR technologies for both entertainment and professional uses. As they gain more widespread usage, immersive technologies could raise some policy issues, including concerns about privacy, intellectual property (ex: who owns certain “experiences”), and potentially even worries about distraction and addiction.

It would not be surprising, therefore, if some critics begin advocating greater regulation of, or liability for, VR and AR intermediaries. If that happens, policymakers will need to consider immunizing them from the threat of lawsuits or else innovation will die in these sectors.

Conclusion

Following the general logic of permissionless innovation, and understanding the importance of keeping intermediaries free of punishing liability for what others might do with their general-purpose technologies and platforms, the proper focus of regulation should remain on the user and uses of those technologies.

Accordingly, policymakers should craft a “Section 230 for the maker movement” by adopting legal protections for robotics, 3D printing, and immersive technology. At the same time, we should seek out better solutions—legal and otherwise—to the old problems that might persist or new ones that might come about due to the use of these new devices and platforms. But we should not let hypothetical worst-case scenarios and concerns about future technologies lead us down a path where intermediaries are “deputized” or hit with punishing liability for downstream actions by third parties.

Note#1 : This is a preliminary sketch of a law review article I would eventually like to write entitled, “A Section 230 for the “Makers” Movement: Extending Section 230 Immunities to Robotics, 3D Printing & Virtual Reality.” Toward that end, I welcome suggestions for (a) which general-purpose technologies deserve some sort of immunization, and also (b) what other legal immunity regimes exist that we could learn from. Please forward any ideas you might have along to me.

Note #2: My thanks to Adam Marcus and Christopher Koopman for their helpful suggestions on this essay.

February 29, 2016

Bipartisan Digital Security Commission Is Only Way to Avoid PATRIOT-Style Legislative Panic

This article originally appeared at techfreedom.org.

Today, Rep. Michael McCaul (R-TX) and Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) introduced legislation to create a blue ribbon commission that would examine the challenges encryption and other forms of digital security pose to law enforcement and national security. The sixteen-member commission will be made up of experts from law enforcement, the tech industry, privacy advocacy and other important stakeholders in the debate and will be required to present an initial report after six months and final recommendations within a year.

In today’s Tech Policy Podcast, TechFreedom President Berin Szoka and Ryan Hagemann, the Niskanen Center’s technology and civil liberties policy analyst, discussed the commission’s potential.

“I see this commission as an ideal resting place for this debate,” Hagemann said. “Certainly what we’re trying to avoid is pushing through any sort of knee-jerk legislation that Senators Feinstein or Burr would propose, especially in the wake of a new terrorist attack.”

“I share the chairman’s concerns that since we’re not making any headway on these issues in the public forum, what is really needed here is for Congress to take some level of decisive action and get all of the people who have something to gain as well as something to lose in this debate to just sit down and talk through the issues that all parties have,” he continued.

“I think it’s going to come out and say that there is no middle ground on end-to-end encryption, but it’s probably going to deal with the Apple situation very specifically,” Szoka said. “I think you’re going to see some standard that is going to be probably a little more demanding upon law enforcement than what law enforcement wants under the All Writs Act.”

February 26, 2016

Senate Bill to Keep the Internet Free of Regulation

Yesterday, almost exactly one year after the FCC classified Internet service as a common carrier service, Sen. Mike Lee and his Senate cosponsors (including presidential candidates Cruz and Rubio) introduced the Restoring Internet Freedom Act. Sen. Lee also published an op-ed about the motivation for his bill, pointing out the folly of applying a 1930s AT&T Bell monopoly law to the Internet. It’s a short bill, simply declaring that the FCC’s Title II rules shall have no force and it precludes the FCC from enacting similar rules absent an act of Congress.

It’s a shame such a bill even has to be proposed, but then again these are unusual times in politics. The FCC has a history of regulating new industries, like cable TV, without congressional authority. However, enforcing Title II, its most intrusive regulations, on the Internet is something different altogether. Congress was not silent on the issue of Internet regulation, like it was regarding cable TV in the 1960s when the FCC began regulating.

Former Clinton staffer John Podesta said after Clinton signed the 1996 Telecom Act, “Congress simply legislated as if the Net were not there.” That’s a slight overstatement. There is one section of the Telecommunications Act, Section 230, devoted to the Internet and it is completely unhelpful for the FCC’s Open Internet rules. Section 230 declares a US policy of unregulation of the Internet and, in fact, actually encourages what net neutrality proponents seek to prohibit: content filtering by ISPs.

The FCC is filled with telecom lawyers who know existing law doesn’t leave room for much regulation, which is why top FCC officials resisted common carrier regulation until the end. Chairman Wheeler by all accounts wanted to avoid the Title II option until pressured by the President in November 2014. As the Wall Street Journal reported last year, the White House push for Title II “blindsided officials at the FCC” who then had to scramble to construct legal arguments defending this reversal. The piece noted,

The president’s words swept aside more than a decade of light-touch regulation of the Internet and months of work by Mr. Wheeler toward a compromise.

The ersatz “parallel version of the FCC” in the White House didn’t understand the implications of what they were asking for and put the FCC in a tough spot. The Title II rules and legal justifications required incredible wordsmithing but still created internal tensions and undesirable effects, as pointed out by the Phoenix Center and others. This policy reversal, to go the Title II route per the President’s request, also created First Amendment and Section 230 problems for the FCC. At oral argument the FCC lawyer disclaimed any notion that the FCC would regulate filtered or curated Internet access. This may leave a gaping hole in Title II enforcement since all Internet access is filtered to some degree, and new Internet services, like LTE Broadcast, Free Basics, and zero-rated video, involve curated IP content. As I said at the time, the FCC “is stating outright that ISPs have the option to filter and to avoid the rules.”

Nevertheless, Title II creates a permission slip regime for new Internet services that forces tech and telecom companies to invest in compliance lawyers rather than engineers and designers. Hopefully in the next few months the DC Circuit Court of Appeals will strike down the FCC’s net neutrality efforts for a third time. In any case, it’s great to see that Sen. Lee and his cosponsors have made innovation policy priority and want to continue the light-touch regulation of the Internet.

February 18, 2016

FCC Violates Basic Legal Principles in Rush to Regulate Set-Top Boxes

This article originally appeared at techfreedom.org.

Today, the FCC voted on a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that would force pay-tv or multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) to change their existing equipment to allow third-party set-top boxes to carry their signals. Currently, MVPD subscribers typically pay $15–20/month to lease set-top boxes from their cable, satellite, or telco video provider. Those set-top boxes allow subscribers to view video programming on their TVs and, in some cases, also provide access to online video distributors (OVDs) such as Netflix and Hulu. However, Chairman Wheeler and some interest groups say those leasing fees are too high, that MVPDs have a stranglehold on video programming, and that the set-top box market must be opened to competition from third parties.

“Regulating set-top boxes may do serious damage to video programmers, especially small ones and those geared to minorities,” said Berin Szoka. “That’s why Congressional Democrats, minority groups and other voices have urged caution. Yet FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler blithely dismisses these concerns, insisting that ‘this is just the beginning of a fact-finding process.’ Do not believe him. If that were true, the FCC would issue a Notice of Inquiry to gather data to inform a regulatory proposal. Instead, the FCC has issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. That means the FCC Chairman has already made up his mind, and that the agency is unlikely to adjust course.”

“This is simply the latest example of the FCC abusing the rulemaking process by bypassing the Notice of Inquiry,” concluded Szoka. “Every time the FCC does this, it means the gun is already loaded, and ‘fact-finding’ is a mere formality. It’s high time Congress put a stop to this pretense of objectivity and require the FCC to begin all major rulemakings with an NOI. That key reform was at the heart of an FCC reform bill initially proposed by Republicans in 2013 — but, tellingly, removed at the insistence of Congressional Democrats.”

The FCC’s proposal is based on the recommendations of the Downloadable Security Technology Advisory Committee (“DSTAC”), which was directed to investigate this issue by Congress in the STELA Reauthorization Act of 2014.

“The FCC is also abusing the advisory committee process—once again,” argued Tom Struble, Policy Counsel at TechFreedom. “The Commission acts as if the DSTAC unanimously supported the NPRM’s proposal. In fact, the DSTAC recommended two alternative approaches, only one of which was taken up by the FCC. This is only the most recent example of the FCC abusing the advisory committee process, denying broad input from stakeholders and steering the committee to issue recommendations that suit the administration’s policy preferences. The FCC should have used an NOI to seek comment on both the DSTAC recommendations. But at the very least, Chairman Wheeler should drop his absurd pretense that the FCC is merely beginning a fact-finding process.”

TechFreedom Sues the FAA on Drone Regulations

This article originally appeared at techfreedom.org.

TechFreedom has sued the Federal Aviation Administration (“FAA”) to overturn the agency’s recently adopted “interim” drone regulations, which require that drones that weigh over 250 grams be registered for a $5 fee.

“Whether or or not requiring drone registration is a wise policy, the rules the FAA rushed out before Christmas are unlawful,” said Berin Szoka, President of TechFreedom. “They exceed the authority Congress has given the FAA. Moreover, the agency illegally bypassed the most basic transparency requirement in administrative law: that it provide an opportunity for the affected public to comment on its regulations. That means the FAA could not fully consider the real-world complexities of regulating drones. Thus, the FAA’s rules could lead to a host of unintended consequences.”

“The notice-and-comment rulemaking process serves an important role in ensuring that regulation doesn’t do more harm than good,” said Tom Struble, Policy Counsel at TechFreedom. “It ensures that the agency is exposed to viewpoints from all the relevant stakeholders, and it forces the agency to weigh competing considerations before issuing a rule. The holiday rush did not justify the FAA bypassing standard notice-and-comment rulemaking, and the paltry cost-benefit analysis contained in the IFR does not pass muster. The D.C. Circuit should set aside these interim rules and force the FAA to go back to the drawing board.”

See TechFreedom’s petition for review here.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower