Adam Thierer's Blog, page 38

March 14, 2015

Autonomous Vehicles Under Attack: Cyber Dashboard Standards and Class Action Lawsuits

In a recent Senate Commerce Committee hearing on the Internet of Things, Senators Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) “announced legislation that would direct the National highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to establish federal standards to secure our cars and protect drivers’ privacy.” Spurred by a recent report from his office (Tracking and Hacking: Security and Privacy Gaps Put American Drivers at Risk) Markey argued that Americans “need the equivalent of seat belts and airbags to keep drivers and their information safe in the 21st century.”

Among the many conclusions reached in the report, it says, “nearly 100% of cars on the market include wireless technologies that could pose vulnerabilities to hacking or privacy intrusions.” This comes across as a tad tautological given that everything from smartphones and computers to large-scale power grids are prone to being hacked, yet the Markey-Blumenthal proposal would enforce a separate set of government-approved, and regulated, standards for privacy and security, displayed on every vehicle in the form of a “Cyber Dashboard” decal.

Leaving aside the irony of legislators attempting to dictate privacy standards, especially in the post-Snowden world, it would behoove legislators like Markey and Blumenthal to take a closer look at just what it is they are proposing and ask whether such a law is indeed necessary to protect consumers. For security in particular, there may be concerns that require redress, but if one looks at the report, it becomes apparent that it lacks a very important feature:: no specific examples of real car hacking are mentioned. The only examples illustrated in the report are described in brief detail:

An application was developed by a third party and released for Android devices that could integrate with a vehicle through the Bluetooth connection. A security analysis did not indicate any ability to introduce malicious code or steal data, but the manufacturer had the app removed from the Google Play store as a precautionary measure.

Great! The company solved the problem. What about the other instance cited in the report?

Some individuals have attempted to reprogram the onboard computers of vehicles to increase engine horsepower or torque through the use of “performance chips”. Some of these devices plug into the mandated onboard diagnostic port or directly into the under-the-hood electronics system.

So the only two examples of “car hacking” described in the Markey report are essentially duds. The first is a non-issue, since the company (1) determined there was little security risk involved and (2) removed the item from the market anyways, just to be sure. The second is, in a sense, hacking, but it is individual car owners doing it to their own cars. Neither of these cases appears to be sufficient grounds for imposing a set of arbitrary and, in many cases, capriciously anti-innovation approaches to privacy and data security in cars.

In the wake of the report’s release, this past Tuesday, March 10, General Motors, Toyota, and Ford were all hit with a nationwide class action lawsuit, alleging that the companies concealed “dangers posed by a lack of electronic security in a vast swath of vehicles.” Specifically, the lawsuit is aimed at the presence of controller area network (CAN) buses, which act as data hubs between the various electronic systems in a car. These systems are, indeed, susceptible to hacking, but no more than any personal computer that is connected to the Internet.

The trouble with this lawsuit, brought by the Stanley Law Group, is that it has not cited any specific harms that have occurred as a result of this “defect” (as a side note, saying a computer being susceptible to hacking constitutes a defect in design is the equivalent of saying an airplane that is susceptible to lightning strikes is fundamentally defective). Rather, the plaintiffs argue that “[w]e shouldn’t need to wait for a hacker or terrorist to prove exactly how dangerous this is before requiring car makers to fix the defect.”

As Adam Thierer and I pointed out in our 2014 paper, Removing Roadblocks to Intelligent Vehicles and Driverless Cars:

Manufacturers have powerful reputational incentives at stake here, which will encourage them to continuously improve the security of their systems. Companies like Chrysler and Ford are already looking into improving their telematics systems to better compartmentalize the ability of hackers to gain access to a car’s controller-area-network bus. Engineers are also working to solve security vulnerabilities by utilizing two-way data-verification schemes (the same systems at work when purchasing items online with a credit card), routing software installs and updates through remote servers to check and double-check for malware, adopting of routine security protocols like encrypting files with digital signatures, and other experimental treatments. (pg. 40-41)

It’s always easy to see the potential for abuse and harm with any new emerging technology, but optimism and fortitude in the face of the uncertain is what helps society, and individuals, grow and progress. Car hacking, while certainly a viable concern, is not so ubiquitous that it necessitates a heavy-handed regulatory approach. Rather, we should permit various standards to emerge and attempt to deal with possible harms. In this way, we can experiment to properly determine what approaches work and what do not. Federal standards imposed from on high assume that firms and individuals are not capable of working through these murky issues. We should be a bit more optimistic about the human capacity for ingenuity and adaptability.

To end on something of a more optimistic note, Tom Vanderbilt of Wired magazine gives keen insight into the reality of regulating based on hypothetical scenarios:

Every scenario you can spin out of computer error – what if the car drives the wrong way – already exists in analog form, in abundance. Yes, computer-guidance systems and the rest will require advances in technology, not to mention redundancy and higher standards of performance, but at least these are all feasible, and capable of quantifiable improvement. On the other hand, we’ll always have lousy drivers.

Additional Reading

Law review article: “Removing Roadblocks to Intelligent Vehicles and Driverless Cars,” September 17, 2014.

“Don’t Hit the (Techno-)Panic Button on Connected Car Hacking & IoT Security,” February 10, 2015.

“Don’t Slam the Brakes on Smart Cars,” December 1, 2014.

“Intelligent Vehicles Could Save Lives,” November 25, 2014.

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom (2014)

March 4, 2015

Bipartisan Internet of Things Resolution Introduced in Senate

A new bipartisan “sense of the Senate” resolution was introduced today calling for “a national strategy for the Internet of Things to promote economic growth and consumer empowerment.” [PDF is here.] The resolution was cosponsored by U.S. Senators Deb Fischer (R-Neb.), Cory A. Booker (D-N.J.), Kelly Ayotte (R-N.H.), and Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii), who are all members of the Senate Commerce Committee, which oversees these issues. Just last month, on February 11th, the full Commerce Committee held a hearing titled “The Connected World: Examining the Internet of Things,” which examined the policy issues surrounding this exciting new space.

The new Senate resolution begins by stressing the many current or potential benefits associate with the Internet of Things (IoT), which, it notes, “currently connects tens of billions of devices worldwide and has the potential to generate trillions of dollars in economic opportunity.” It continues on to note how average consumers will benefit because “increased connectivity can empower consumers in nearly every aspect of [our] daily lives, including in the fields of agriculture, education, energy, healthcare, public safety, security, and transportation, to name just a few.” And then the resolution also discussed the commercial benefits, noting, “businesses across our economy can simplify logistics, cut costs in supply chains, and pass savings on to consumers because of the Internet of Things and innovations derived from it.” More generally, the Senators argue “the United States should strive to be a world leader in smart cities and smart infrastructure to ensure its citizens and businesses, in both rural and urban parts of the country, have access to the safest and most resilient communities in the world.”

In light of those amazing potential benefits, the resolution continues on to argue that while “the United States is the world leader in developing the Internet of Things technology,” an even more focused and dedicated policy vision is needed to promote continued success. “[W]ith a national strategy guiding both public and private entities,” it argues, “the United States will continue to produce breakthrough technologies and lead the world in innovation.”

Toward that end, the resolution says that it is the sense of the Senate that:

(1) the United States should develop a national strategy to incentivize the development of the Internet of Things in a way that maximizes the promise connected technologies hold to empower consumers, foster future economic growth, and improve our collective social well-being;

(2) the United States should prioritize accelerating the development and deployment of the Internet of Things in a way that recognizes its benefits, allows for future innovation, and responsibly protects against misuse;

(3) the United States should recognize the importance of consensus-based best practices and communication among stakeholders, with the understanding that businesses can play an important role in the future development of the Internet of Things;

(4) the United States Government should commit itself to using the Internet of Things to improve its efficiency and effectiveness and cut waste, fraud, and abuse whenever possible; and,

(5) using the Internet of Things, innovators in the United States should commit to improving the quality of life for future generations by developing safe, new technologies aimed at tackling the most challenging societal issues facing the world.

This is a pretty solid statement from this group of Senators, who appear committed to advancing a pro-innovation, pro-growth approach to the emerging Internet of Things universe of technologies. This is exciting because this reflects the strong bipartisan approach American policymakers adopted two decades ago for the Internet more generally. America’s unified, “light-touch” Internet policy vision worked wonders for consumers and our economy before, and it can happen again thanks to a vision like the one these four Senators floated today.

As I explained in more detail when I testified at the February 11th Senate Commerce hearing on IoT issue:

America took a commanding lead in the digital economy because, in the mid-1990s, Congress and the Clinton administration crafted a nonpartisan vision for the Internet that protected “permissionless innovation” — the idea that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted without prior approval. Congress embraced permissionless innovation by passing the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and rejecting archaic Analog Era command-and-control regulations for this exciting new medium. The Clinton administration embraced permissionless innovation with its 1997 “Framework for Global Electronic Commerce,” which outlined a clear vision for Internet governance that relied on civil society, voluntary agreements, and ongoing marketplace experimentation. This nonpartisan blueprint sketched out almost two decades ago for the Internet is every bit as sensible today as we begin crafting a policy paradigm for the Internet of Things

I view this new Senate resolution on the Internet of Things as an effort to freshen up and extend that original vision that lawmakers crafted for the Internet back in the mid-1990s. As I documented in my recent essay, “Why Permissionless Innovation Matters,” that vision has worked wonders for American consumers and our modern economy. Meanwhile, our international rivals languished on this front because they strapped their tech sectors with layers of regulatory red tape that thwarted digital innovation.

We got policy right once before in the United States, and we can get it right again with a policy vision like that found in this new Senate resolution for the Internet of Things.

____________________________

Additional Reading

testimony: “My Testimony for Senate Internet of Things Hearing,” February 11, 2015.

essay: “What Cory Booker Gets about Innovation Policy,” February 16, 2015.

essay: “A Nonpartisan Policy Vision for the Internet of Things,” December 11, 2014.

law review article: “The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation,” November 2014.

essay: “Don’t Hit the (Techno-)Panic Button on Connected Car Hacking & IoT Security,” February 10, 2015.

essay: “Striking a Sensible Balance on the Internet of Things and Privacy,” January 16, 2015.

essay: “Some Initial Thoughts on the FTC Internet of Things Report,” January 28, 2015.

slide presentation: “Policy Issues Surrounding the Internet of Things & Wearable Technology,” September 12, 2014.

essay: “CES 2014 Report: The Internet of Things Arrives, but Will Washington Welcome It?” January 8, 2014.

February 27, 2015

Initial Thoughts on Obama Administration’s “Privacy Bill of Rights” Proposal

The Obama Administration has just released a draft “Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2015.” Generally speaking, the bill aims to translate fair information practice principles (FIPPs) — which have traditionally been flexible and voluntary guidelines — into a formal set of industry best practices that would be federally enforced on private sector digital innovators. This includes federally-mandated Privacy Review Boards, approved by the Federal Trade Commission, the agency that will be primarily responsible for enforcing the new regulatory regime.

Many of the principles found in the Administration’s draft proposal are quite sensible as best practices, but the danger here is that they could soon be converted into a heavy-handed, bureaucratized regulatory regime for America’s highly innovative, data-driven economy.

No matter how well-intentioned this proposal may be, it is vital to recognize that restrictions on data collection could negatively impact innovation, consumer choice, and the competitiveness of America’s digital economy.

Online privacy and security is vitally important, but we should look to use alternative and less costly approaches to protecting privacy and security that rely on education, empowerment, and targeted enforcement of existing laws. Serious and lasting long-term privacy protection requires a layered, multifaceted approach incorporating many solutions.

That is why flexible data collection and use policies and evolving best practices will ultimately serve consumers better than one-size-fits all, top-down regulatory edicts. Instead of imposing these FIPPs in a rigid regulatory fashion, privacy and security best practices will need to evolve gradually to new marketplace realities and be applied in a more organic and flexible fashion, often outside the realm of public policy.

Regulatory approaches, like the Obama Administration’s latest proposal, will instead impose significant costs on consumers and the economy. Data is the fuel that powers our information economy. Privacy-related mandates that curtail the use of data to better target or personalize new services could raise costs for consumers. There is no free lunch. Something has to pay for all the wonderful free sites and services we enjoy today. If data can’t be used to cross-subsidize those services, prices will go up.

Data regulations could also indirectly cost consumers by diminishing the abundance of content and culture now supported by the data-driven economy. In other words, even if prices and paywalls don’t go up, quantity or quality could suffer if data collection is restricted.

Data regulations could also hurt the competitiveness of domestic markets and the global competitive advantage that America’s tech sector has in this space. That regulatory burden would fall hardest on smaller operators and new start-ups. Today’s “app economy” has given countless small innovators a chance to compete on even footing with the biggest players. Burdensome data collection restrictions could short-circuit the engine that drives entrepreneurial innovation among mom-and-pop companies if ad dollars get consolidated in the hands of only the larger companies that can afford to comply with new rules.

We don’t want to go down the path the European Union charted in the 1990s with heavy-handed data directives. That suffocated high-tech entrepreneurialism and innovation there. America’s Internet sector came to be the envy of the world because our more flexible, light-touch regulatory regime leaves more breathing room for competition and innovation compared to Europe’s top-down regime. We should not abandon that approach now.

Finally, the Obama Administration’s proposal deals exclusively with private sector data collection and has nothing to say about government surveillance activities. The Administration would be wise to channel its energies into that far more significant privacy problem first.

________________________

Additional Reading from Adam Thierer of the Mercatus Center

Law Review Articles:

“The Pursuit of Privacy in a World Where Information Control is Failing,” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vol. 36, No. 2, (2013).

“A Framework for Benefit-Cost Analysis in Digital Privacy Debates,” George Mason Law Review, Vol. 20, No. 4, (2013).

“Privacy Law’s Precautionary Principle Problem,” Maine Law Review, Vol. 66, No. 2 (2014).

“The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation,” Richmond Journal of Law and Technology, Vol. 21 (2015).

“Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology, Vol. 14, No. 1, (2013).

Testimony / Filings

Testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee on the Internet of Things, February 11, 2015.

Testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee on Privacy, Data Collection & Do Not Track, April 24, 2013.

Filing to the Federal Trade Commission on Privacy & Security Implications of the Internet of Things, May 31, 2013.

Filing to the Federal Trade Commission on Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change, February 22, 2011.

February 23, 2015

Mercatus Center Scholars Contributions to Cybersecurity Research

by Adam Thierer & Andrea Castillo

Cybersecurity policy is a big issue this year, so we thought it be worth reminding folks of some contributions to the literature made by Mercatus Center-affiliated scholars in recent years. Our research, which can be found here, can be condensed to these five core points:

1) Institutions, societies, and economies are more resilient than we give them credit for and can deal with adversity, even cybersecurity threats.

See: Sean Lawson, “Beyond Cyber-Doom: Assessing the Limits of Hypothetical Scenarios in the Framing of Cyber-Threats,” December 19, 2012.

2) Companies and organizations have a vested interest in finding creative solutions to these problems through ongoing experimentation and they are pursing them with great vigor.

See: Eli Dourado, “Internet Security Without Law: How Service Providers Create Order Online,” June 19, 2012.

3) Over-arching, top-down “cybersecurity frameworks” threaten to undermine dynamism in cybersecurity and Internet governance, and could promote rent-seeking and corruption. Instead, the government should foster continued dynamic cybersecurity efforts through the development of a robust private-sector cybersecurity insurance market.

See: Eli Dourado and Andrea Castillo, “Why the Cybersecurity Framework Will Make Us Less Secure,” April 17, 2014.

4) The language sometimes used to describe cybersecurity threats sometimes borders on “techno-panic” rhetoric that is based on “threat inflation.

See the Lawson paper already cited as well as: Jerry Brito & Tate Watkins “Loving the Cyber Bomb? The Dangers of Threat Inflation in Cybersecurity Policy,” April 10, 2012; and Adam Thierer, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” January 25, 2013.

5) Finally, taking these other points into account, our scholars have conclude that academics and policymakers should be very cautious about how they define “market failure” in the cybersecurity context. Moreover, to the extent they propose new regulatory controls to address perceived problems, those rules should be subjected to rigorous benefit-cost analysis.

See: Eli Dourado, “Is There a Cybersecurity Market Failure,” January 23, 2012.

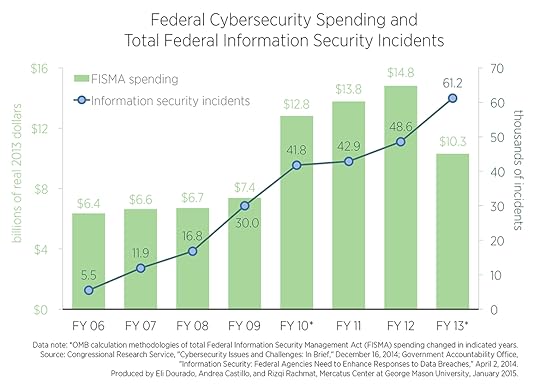

Developing cybersecurity policies—like the White House’s “Securing Cyberspace” proposal and the Senate Intelligence Committee’s risen-from-the-grave Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) of 2015—prioritize government-led “information-sharing” among federal agencies and private organizations as a one-stop technocratic solution to the dynamic problem of cybersecurity provision. But, as Eli and Andrea pointed out in a Mercatus chart series from this year, the federal government’s own success with internal information-sharing policies has been abysmal for decades.

Developing cybersecurity policies—like the White House’s “Securing Cyberspace” proposal and the Senate Intelligence Committee’s risen-from-the-grave Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) of 2015—prioritize government-led “information-sharing” among federal agencies and private organizations as a one-stop technocratic solution to the dynamic problem of cybersecurity provision. But, as Eli and Andrea pointed out in a Mercatus chart series from this year, the federal government’s own success with internal information-sharing policies has been abysmal for decades.

The Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 compelled federal investment in IT security infrastructure along with internal information-sharing of system breaches and proactive responses among agencies. Apparently, this has not worked like a charm. The chart shows that reported federal breaches have risen by over 1000% since 2006 despite spending billions of dollars on agency systems and information sharing capabilities over the same time.

Many of the same agencies who would be imbued with power to coordinate information-sharing among private and government entities through CISA and other cybersecurity proposals were responsible for coordinating threat-sharing on the federal level. These are the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Are we to believe these bodies will become magically efficient once they have more power to cajole the private sector?

Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports analyzing the failure of federal information security practices and threat coordination find that the technocratic solutions that look so perfectly rational and controlled on paper break down when imposed from above on employees that have no buy-in. The report concludes, “As we and inspectors general have long pointed out, federal agencies continue to face challenges in effectively implementing all elements of their information security programs.” Repeating the same failed policies in the private sector is unlikely to result in success.

Cybersecurity provision is too important of an issue to be left to brittle, technocratic policies with proven track records of failure. Rather, good cybersecurity policy will be grounded in an understanding of the incentives and norms that have allowed the Internet to develop and thrive as the system that it is today to target specific sources of failure.

Industry analyses find again and again that with cybersecurity, the problem exists between chair and keyboard—“human error,” not insufficient government meddling, is responsible for the vast majority of cyber incidents. Introducing more error-prone humans to the equation, as government cybersecurity plans seek to do, will only complicate the problem while neglecting the underlying factors that need addressing.

Cybersecurity will be an issue we continue to cover closely at the Mercatus Center Technology Policy Program.

February 16, 2015

Initial Thoughts on New FAA Drone Rules

Yesterday afternoon, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) finally released its much-delayed rules for private drone operations. As The Wall Street Journal points out, the rules “are about four years behind schedule,” but now the agency is asking for expedited public comments over the next 60 days on the whopping 200-page order. (You have to love the irony in that!) I’m still going through all the details in the FAA’s new order — and here’s a summary of what the major provisions — but here are some high-level thoughts about what the agency has proposed.

Opening the Skies…

The good news is that, after a long delay, the FAA is finally taking some baby steps toward freeing up the market for private drone operations.

Innovators will no longer have to operate entirely outside the law in a sort of drone black market. There’s now a path to legal operation. Specifically, small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) operators (for drones under 55 lbs.) will be able to go through a formal certification process and, after passing a test, get to operate their systems.

… but Not Without Some Serious Constraints

The problem is that the rules only open the skies incrementally for drone innovation.

You can’t read through these 200 pages of regulations without getting sense that the FAA still wishes that private drones would just go away.

For example, the FAA still wants to keep a bit of a leash around drones by (1) limiting their use to being daylight-only flights (2) that are in the visual line-of-sight of the operators at all times. And (3) the agency also says that drones cannot be flown over people.

Those three limitations will hinder some obvious innovations, such as same-day drone delivery for small packages, which Amazon has suggested they are interested in pursuing. (Amazon isn’t happy about these restrictions.)

Impact on Small Innovators?

But what I worry about more are all the small ‘Mom-and-Pop’ drone entrepreneur, who want to use airspace as a platform for open, creative innovation. These folks are out there but they don’t have the name or the resources to weather these restrictions the way that Amazon can. After all, if Amazon has to abandon same-day drone delivery because of the FAA rules, the company will still have a thriving commercial operation to fall back on. But all those small, nameless drone innovators currently experimenting with new, unforeseeable innovations may not be so lucky.

As a result, there’s a real threat here of drone entrepreneurs bolting the U.S. and offering their services in more hospitable environments if the FAA doesn’t take a more flexible approach.

[For more discussion of this problem, see my recent essay on “global innovation arbitrage.”]

Impact on News-Gathering?

It’s also worth asking how these rules might limit legitimate news-gathering operations by both journalistic enterprises and average citizens. If we can never fly a drone over a crowd of people, as the rules stipulate, that places some rather serious constraints on our ability to capture real-time images and video from events of societal importance (such as political protests or even just major events like sporting events or concerts).

[For more discussion about this, see this September 2014 Mercatus Center working paper, “News from Above: First Amendment Implications of the Federal Aviation Administration Ban on Commercial Drones.”]

Still Time to Reconsider More Flexible Rules

Of course, these aren’t final rules and the agency still has time to relax some of these restrictions to free the skies for less fettered private drone operation.

I suspect that drone innovators will protest the three specific limitations I identified above and ask for a more flexible approach to enforcing those rules.

But it’s good that the FAA has finally taken the first step toward decriminalizing private drone operations in the United States.

___________________________

Additional Reading

Permissionless Innovation & Commercial Drones, February 4, 2015.

DRM for Drones Will Fail, January 28, 2015.

Regulatory Capture: FAA and Commercial Drones Edition, January 16, 2015.

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Commercial Drones & Sharing Economy Edition, December 9, 2014.

How to Destroy American Innovation: The FAA & Commercial Drones, October 6, 2014.

Filing to FAA on Drones & “Model Aircraft”, Sept. 23, 2014.

Private Drones & the First Amendment, Sept. 19, 2014.

[TV interview] The Beneficial Uses of Private Drones, March 28, 2014.

Comments of the Mercatus Center to the FAA on integration of drones into the nation’s airspace, April 23, 2o13.

Eli Dourado, Deregulate the Skies: Why We Can’t Afford to Fear Drones, Wired, April 23, 2013.

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom (2014).

[Video] Cap Hill Briefing on Emerging Tech Policy Issues (June 2014).

What Cory Booker Gets about Innovation Policy

Last Wednesday, it was my great pleasure to testify at a Senate Commerce Committee hearing entitled, “The Connected World: Examining the Internet of Things.” The hearing focused “on how devices… will be made smarter and more dynamic through Internet technologies. Government agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, however, are already considering possible changes to the law that could have the unintended consequence of slowing innovation.”

Last Wednesday, it was my great pleasure to testify at a Senate Commerce Committee hearing entitled, “The Connected World: Examining the Internet of Things.” The hearing focused “on how devices… will be made smarter and more dynamic through Internet technologies. Government agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, however, are already considering possible changes to the law that could have the unintended consequence of slowing innovation.”

But the session went well beyond the Internet of Things and became a much more wide-ranging discussion about how America can maintain its global leadership for the next-generation of Internet-enabled, data-driven innovation. On both sides of the aisle at last week’s hearing, one Senator after another made impassioned remarks about the enormous innovation opportunities that were out there. While doing so, they highlighted not just the opportunities emanating out of the IoT and wearable device space, but also many other areas, such as connected cars, commercial drones, and next-generation spectrum.

I was impressed by the energy and nonpartisan vision that the Senators brought to these issues, but I wanted to single out the passionate statement that Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) delivered when it came his turn to speak because he very eloquently articulated what’s at stake in the battle for global innovation supremacy in the modern economy. (Sen. Booker’s remarks were not published, but you can watch them starting at the 1:34:00 mark of the hearing video.)

Embrace the Opportunity

First, Sen. Booker stressed the enormous opportunity with the Internet of Things. “This is a phenomenal opportunity for a bipartisan, profoundly patriotic approach to an issue that can explode our economy. I think that there are trillions of dollars, creating countless jobs, improving quality of life, [and] democratizing our society,” he said. “We can’t even imagine the future that this portends of, and we should be embracing that.”

Sen. Booker has it exactly right. And for more details about the enormous innovation opportunities associated with the Internet of Things, see Section 2 of my new law review article, “The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation,” which provides concrete evidence.

Protect America’s Competitive Advantage in the Innovation Age

Second, Sen. Booker highlighted the importance of getting our policy vision right to achieve those opportunities. He noted that “a lot of my concerns are what my Republican colleagues also echoed, which is we should be doing everything possible to encourage this and nothing to restrict it.”

“America right now is the net exporter of technology and innovation in the globe, and we can’t lose that advantage,” he said and “we should continue to be the global innovators on these areas.” He continued on to say:

And so, from copyright issues, security issues, privacy issues… all of these things are worthy of us wrestling and grappling with, but to me we cannot stop human innovation and we can’t give advantages in human innovation to other nations that we don’t have. America should continue to lead.

This is something I have been writing actively about now for many years and I agree with Sen. Booker that America needs to get our policy vision right to ensure we don’t lose ground in the international competition to see who will lead the next wave of Internet-enabled innovation. As I noted in my testimony, “If America hopes to be a global leader in the Internet of Things, as it has been for the Internet more generally over the past two decades, then we first have to get public policy right. America took a commanding lead in the digital economy because, in the mid-1990s, Congress and the Clinton administration crafted a nonpartisan vision for the Internet that protected “permissionless innovation”—the idea that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted without prior approval.”

Meanwhile, as I documented in my longer essay, “Why Permissionless Innovation Matters: Why does economic growth occur in some societies & not in others?” our international rivals languished on this front because they strapped their tech sectors with layers of regulatory red tape that thwarted digital innovation.

Reject Fear-Based Policymaking

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Sen. Booker stressed how essential it was that we reject a fear-based approach to public policymaking. As he noted at the hearing about these new information technologies, “there’s a lot of legitimate fears, but in the same way of every technological era, there must have been incredible fears.”

He cited, for example, the rise of air travel and the onset of humans taking flight. Sen. Booker correctly noted that while that must have been quite jarring at first, we quickly came to realize the benefits of that new innovation. The same will be true for new technologies such as the Internet of Things, connected cars, and private drones, Booker argued. In each case, some early fears about these technologies could lead to overly-precautionary approach to policy. “But for us to do anything to inhibit that leap in humanity to me seems unfortunate,” he said.

Once again, the Senator has it exactly right. As I noted in my law review article on “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” as well as my recent essay, “Muddling Through: How We Learn to Cope with Technological Change,” humans have exhibited the uncanny ability to adapt to changes in their environment, bounce back from adversity, and learn to be resilient over time. A great deal of wisdom is born of experience, including experiences that involve risk and the possibility of occasional mistakes and failures while both developing new technologies and learning how to live with them. More often than not, citizens have found ways to adapt to technological change by employing a variety of coping mechanisms, new norms, or other creative fixes.

Booker gets that and understands why we need to be patient to allow that process to unfold once again so that we can enjoy the abundance of riches that will accompany a more innovative economy.

Avoiding Global Innovation Arbitrage

Sen. Booker also highlighted how some existing government legal and regulatory barriers could hold back progress. On the wireless spectrum front he noted that “the government hoards too much spectrum and there is a need for more spectrum out there. Everything we are talking about,” he argued, “is going to necessitate more spectrum.” Again, 100% correct. Although some spectrum reform proposals (licensed vs. unlicensed, for example) will still prove contentious, we can at least all agree that we have to work together to find ways to open up more spectrum since the coming Internet of Things universe of technologies is going to demand lots of it.

Booker also noted that another area where fear undermines American leadership is the issue of private drone use. He noted that, “the potential possibilities for drone technology to alleviate burdens on our infrastructure, to empower commerce, innovation, jobs… to really open up unlimited opportunities in this country is pretty incredible to me.”

The problem is that existing government policies, enforced by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), have been holding back progress. And that has had consequences in terms of global competitiveness. “As I watch our government go slow in promulgating rules holding back American innovation,” Booker said, “what happened as a result of that is that innovation has spread to other countries that don’t have these rules (or have) put in place sensible regulations. But now we seeing technology exported from America and going other places.”

Correct again! I wrote about this problem in a recent essay on “global innovation arbitrage,” in which I noted how “Capital moves like quicksilver around the globe today as investors and entrepreneurs look for more hospitable tax and regulatory environments. The same is increasingly true for innovation. Innovators can, and increasingly will, move to those countries and continents that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.”

That’s already happening with drone innovation, as I documented in that piece. Evidence suggests that the FAA’s heavy-handed and overly-precautionary approach to drones has encouraged some innovators to flock overseas in search of more hospitable regulatory environment.

Luckily, just this weekend, the FAA finally announced its (much-delayed) rules for private drone operations. (Here’s a summary of those rules.) Unfortunately, the rules are a bit of mixed bag, with some greater leeway being provided for very small drones, but the rules will still be too restrictive to allow for other innovative applications, such as widespread drone delivery (which has Amazon angry, among others.)

Bottom line: if our government doesn’t take a more flexible, light-touch approach to these and other cutting-edge technologies, than some of our most creative minds and companies are going to bolt.

I dealt with all of these innovation policy issues in far more detail in my latest little book Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, which I condensed further still into this essay on, “Embracing a Culture of Permissionless Innovation.” But Sen. Booker has offered us an even more concise explanation of just what’s at stake in the battle for innovation leadership in the modern economy. His remarks point the way forward and illustrate, as I have noted before, that innovation policy can and should be a nonpartisan issue.

____________________________

Additional Reading

testimony: “My Testimony for Senate Internet of Things Hearing,” February 11, 2015.

essay: “A Nonpartisan Policy Vision for the Internet of Things,” December 11, 2014.

law review article: “The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation,” November 2014.

essay: “Don’t Hit the (Techno-)Panic Button on Connected Car Hacking & IoT Security,” February 10, 2015.

essay: “Striking a Sensible Balance on the Internet of Things and Privacy,” January 16, 2015.

essay: “Some Initial Thoughts on the FTC Internet of Things Report,” January 28, 2015.

slide presentation: “Policy Issues Surrounding the Internet of Things & Wearable Technology,” September 12, 2014.

essay: “CES 2014 Report: The Internet of Things Arrives, but Will Washington Welcome It?” January 8, 2014.

February 11, 2015

My Testimony for Senate Internet of Things Hearing

This morning at 9:45, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation is holding a full committee hearing entitled, “The Connected World: Examining the Internet of Things.” According to the Committee press release, the hearing “will focus on how devices — from home heating systems controlled by users online, to wearable devices that track health and activity with the help of Internet-based analytics — will be made smarter and more dynamic through Internet technologies. Government agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, however, are already considering possible changes to the law that could have the unintended consequence of slowing innovation.”

It is my pleasure to have been invited to testify at this hearing. I’ve long had an interest in the policy issues surrounding the Internet of Things. All my relevant research products can be found online here, including my latest law review article, “The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation.”

My testimony, which can be found on the Mercatus Center website here, begins by highlighting the three general conclusions of my work:

First, the Internet of Things offers compelling benefits to consumers, companies, and our country’s national competitiveness that will only be achieved by adopting a flexible policy regime for this fast-moving space.

Second, while there are formidable privacy and security challenges associated with the Internet of Things, top-down or one-size-fits-all regulation will limit innovative opportunities.

Third, with those first two points in mind, we should seek alternative and less costly approaches to protecting privacy and security that rely on education, empowerment, and targeted enforcement of existing legal mechanisms. Long-term privacy and security protection requires a multifaceted approach incorporating many flexible solutions.

I continue on to elaborate on each point and then conclude my testimony on a note of optimism:

we should also never forget that, no matter how disruptive these new technologies may be in the short term, we humans have an extraordinary ability to adapt to technological change and bounce back from adversity. That same resilience will be true for the Internet of Things. We should remain patient and continue to embrace permissionless innovation to ensure that the Internet of Things thrives and American consumers and companies continue to be global leaders in the digital economy.

My testimony also includes 7 appendices offering more detail for those interested. Two of those appendices focus on defining the parameters of the Internet of Things as then documenting the projected economic impact associated with this rapidly-growing market. The other appendices reproduce essays I have published here before, including articles about the Federal Trade Commission’s recent Internet of Things report as well as my thoughts on how to craft a nonpartisan policy vision for the Internet of Things.

Finally, here’s a list of most of my recent work the Internet of Things and wearable technology policy issues for those interested in reading even more about the topic:

law review article: “ The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation ,” November 2014.

essay: “Don’t Hit the (Techno-)Panic Button on Connected Car Hacking & IoT Security,” February 10, 2015.

essay: “Striking a Sensible Balance on the Internet of Things and Privacy,” January 16, 2015.

essay: “Some Initial Thoughts on the FTC Internet of Things Report,” January 28, 2015.

essay: “A Nonpartisan Policy Vision for the Internet of Things,” December 11, 2014.

slide presentation: “Policy Issues Surrounding the Internet of Things & Wearable Technology,” September 12, 2014.

essay: “CES 2014 Report: The Internet of Things Arrives, but Will Washington Welcome It?” January 8, 2014.

essay: “The Growing Conflict of Visions over the Internet of Things & Privacy,” January 14, 2014.

oped: “Can We Adapt to the Internet of Things?” IAPP Privacy Perspectives, June 19, 2013

agency filing: My Filing to the FTC in its ‘Internet of Things’ Proceeding, May 31, 2013

book: Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom , 2014.

video: Cap Hill Briefing on Emerging Tech Policy Issues, June 2014.

essay: “What’s at Stake with the FTC’s Internet of Things Workshop,” November 18, 2013.

law review article: “Removing Roadblocks to Intelligent Vehicles and Driverless Cars,” September 16, 2014.

February 10, 2015

Don’t Hit the (Techno-)Panic Button on Connected Car Hacking & IoT Security

On Sunday night, 60 Minutes aired a feature with the ominous title, “Nobody’s Safe on the Internet,” that focused on connected car hacking and Internet of Things (IoT) device security. It was followed yesterday morning by the release of a new report from the office of Senator Edward J. Markey (D-Mass) called Tracking & Hacking: Security & Privacy Gaps Put American Drivers at Risk, which focused on connected car security and privacy issues. Employing more than a bit of techno-panic flare, these reports basically suggest that we’re all doomed.

On Sunday night, 60 Minutes aired a feature with the ominous title, “Nobody’s Safe on the Internet,” that focused on connected car hacking and Internet of Things (IoT) device security. It was followed yesterday morning by the release of a new report from the office of Senator Edward J. Markey (D-Mass) called Tracking & Hacking: Security & Privacy Gaps Put American Drivers at Risk, which focused on connected car security and privacy issues. Employing more than a bit of techno-panic flare, these reports basically suggest that we’re all doomed.

On 60 Minutes, we meet former game developer turned Department of Defense “cyber warrior” Dan (“call me DARPA Dan”) Kaufman–and learn his fears of the future: “Today, all the devices that are on the Internet [and] the ‘Internet of Things’ are fundamentally insecure. There is no real security going on. Connected homes could be hacked and taken over.”

60 Minutes reporter Lesley Stahl, for her part, is aghast. “So if somebody got into my refrigerator,” she ventures, “through the internet, then they would be able to get into everything, right?” Replies DARPA Dan, “Yeah, that’s the fear.” Prankish hackers could make your milk go bad, or hack into your garage door opener, or even your car.

This segues to a humorous segment wherein Stahl takes a networked car for a spin. DARPA Dan and his multiple research teams have been hard at work remotely programming this vehicle for years. A “hacker” on DARPA Dan’s team proceeded to torment poor Lesley with automatic windshield wiping, rude and random beeps, and other hijinks. “Oh my word!” exclaims Stahl.

Never mind that we are told that the “hackers” who “hacked” into this car had been directly working on its systems for years—a luxury scarcely available to the shadowy malicious hackers about whom DARPA Dan and his team so hoped to frighten us. The careful setup, editing, and Lesley Stahl’s squeals made for convincing theater.

Then there’s the Markey report. On the surface, the findings appear grim. For instance, we are warned that “Nearly 100% of cars on the market include wireless technologies that could pose vulnerabilities to hacking or privacy intrusions.” Nearly 100%? We’re practically naked out there! But digging through the report, we learn that the basis for this claim is that most of the 16 manufacturers surveyed responded that 100% of their vehicles are equipped with wireless entry points (WEPs)—like Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, navigation, and anti-theft features. Because these features “could pose vulnerabilities,” they are listed as a threat—one that lurks in nearly 100% of the cars on the market, at that.

Much of the report is similarly panicky and sometimes humorous (complaint #3: “many manufacturers did not seem to understand the questions posed by Senator Markey.”) The report concludes that the “alarmingly inconsistent and incomplete state of industry security and privacy practice,” warrants recommendations that federal regulators — led by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — “promulgate new standards that will protect the data, security and privacy of drivers in the modern age of increasingly connected vehicles.”

Take a Deep Breath

As we face an uncertain future full of rapidly-evolving technologies, it’s only natural that some might feel a little anxiety about how these new machines and devices operate. Despite the exaggerated and sometimes silly nature of techno-panic reports like these, they reflect many people’s real and understandable concerns about new technologies.

But the problem with these reports is that they embody a “panic-first” approach to digital security and privacy issues. It is certainly true that our cars are become rolling computers, complete with an arsenal of sensors and networking technologies, and the rise of the Internet of Things means almost everything we own or come into contact with will possess networking capabilities. Consequently, just as our current generation of computing and communications technologies are vulnerable to some forms of hacking, it is likely that our cars and IoT devices will be as well.

But don’t you think that automakers and IoT developers know that? Are we really to believe that journalists, congressmen, and DARPA Dan have a greater incentive to understand these issues than the manufacturers whose companies and livelihoods are on the line? And wouldn’t these manufacturers only take on these risks if consumer demand and expected value supported them? Watching the 60 Minutes spot and reading through the Markey report, one is led to think that innovators in this space are completely oblivious to these threats, simply don’t care enough to address them, and don’t have any plans in motion. But that is lunacy.

No Mention of Liability?

To begin, neither report even mentions the possibility of massive liability for future hacking attacks on connected cars or IoT devices. That is amazing considering how the auto industry already attracts an absolutely astonishing amount of litigation activity. (Ambulance-chasing is a full-time legal profession, after all.) Thus, to the extent that some automakers don’t want to talk about everything they are doing to address security issues, it’s likely because they are still figuring out how to address the various vulnerabilities out there without attracting the attention of either enterprising hackers or trial lawyers.

Nonetheless, contrary to the absurd statement by Mr. Kaufman that “There is no real security going on” for connected cars or the Internet of Things, the reality is that these are issues that developers are actively studying and trying to address. Manufacturers of connected devices know that: (1) nobody wants to own or use devices that are fundamentally insecure or dangerous; and (2) if they sell such devices to the public, they are in for a world of hurt once the trial lawyers see the first headlines about it.

It also still quite unclear how big the threat is here. Writing over at Forbes yesterday, Doug Newcomb notes that “the threat of car hacking has largely been overblown by the media – there’s been only one case of a malicious car hack, and that was an inside job by a disgruntled former car dealer employee. But it’s a surefire way to get the attention of the public and policymakers,” he correctly observes. Newcomb also interviewed Damon McCoy, an assistant professor of computer science at George Mason University and a car security researcher, who noted that car hacking hasn’t become prevalent and that “Given the [monetary] motivation of most hackers, the chance of [automotive hacking] is very low.”

Security is a Dynamic, Evolving Process

Regardless, the notion that we can just clean this whole device security situation up with a single set of federal standards, as the Markey report suggests, is appealing but fanciful. “Security threats are constantly changing and can never be holistically accounted for through even the most sophisticated flowcharts,” observed my Mercatus Center colleagues Eli Dourado and Andrea Castillo in their recent white paper on “Why the Cybersecurity Framework Will Make Us Less Secure.” “By prioritizing a set of rigid, centrally designed standards, policymakers are neglecting potent threats that are not yet on their radar,” Dourado and Castillo note elsewhere.

We are at the beginning of a long process. There is no final destination when it comes to security; it’s a never-ending process of devising and refining policies to address vulnerabilities on the fly. The complex problem of cybersecurity readiness requires dynamic solutions that properly align incentives, improve communication and collaboration, and encourage good personal and organizational stewardship of connected systems. Implementing the brittle bureaucratic standards that Markey and others propose could have the tragic unintended consequence of rendering our devices even less secure.

Standards Are Developing Rapidly

Meanwhile, the auto industry has already come up with privacy standards that go above and beyond what most other digital innovators apply to their own products today. Here are the Auto Alliance’s “Consumer Privacy Protection Principles: Privacy Principles for Vehicle Technologies and Services,” which 23 major automobile manufacturers agreed to abide by. And, according to a press release yesterday, “automakers are currently working to establish an Information Sharing Analysis Center (or “Auto-ISAC”) for sharing vehicle cybersecurity information among industry stakeholders.”

Again, progress continues and standards are evolving. This needs to be a flexible, evolutionary process, instead of a static, top-down, one-size-fits-all bureaucratic political proceeding.

We can’t set down security and privacy standards in stone for fast-moving technologies like these for another reason, and one I am constantly stressing in my work on “Why Permissionless Innovation Matters.” If we spend all our time worrying about hypothetical worst-case scenarios — and basing our policy interventions on a parade of hypothetical horribles — then we run the risk that best-case scenarios will never come about. As analysts at the Center for Data Innovation correctly argue, policymakers should only intervene to address specific, demonstrated harms. “Attempting to erect precautionary regulatory barriers for purely speculative concerns is not only unproductive, but it can discourage future beneficial applications of the Internet of Things.” And the same is true for connected cars.

Trade-Offs Matter

Technopanic indulgence isn’t always merely silly or annoying—it can be deadly.

“During the four deadliest wars the United States fought in the 20th century, 39 percent more Americans were dying in motor vehicles” than on the battlefield. So writes Washington Post reporter Matt McFarland in a powerful new post today. The ongoing toll associated with human error behind the wheel is falling but remains absolutely staggering, with almost 100 people losing their lives and almost 6,500 people injured every day.

We must never fail to appreciate the trade-offs at work when we are pondering precautionary regulation. Ryan Hagemann and I wrote about these issues in our recent Mercatus Center working paper, “Removing Roadblocks to Intelligent Vehicles and Driverless Cars.” That paper, which has been accepted for publication in a forthcoming edition of the Wake Forest Journal of Law & Policy, outlines the many benefits of autonomous or semi-autonomous systems and discusses the potential cost of delaying their widespread adoption.

When it comes to the various security, privacy, and ethical considerations related to intelligent vehicles, Hagemann and I argue that they “need to be evaluated against the backdrop of the current state of affairs, in which tens of thousands of people die each year in auto-related accidents due to human error.” We continue on later in the paper:

Autonomous vehicles are unlikely to create 100 percent safe, crash-free roadways, but if they significantly decrease the number of people killed or injured as a result of human error, then we can comfortably suggest that the implications of the technology, as a whole, are a boon to society. The ethical underpinnings of what makes for good software design and computer-generated responses are a difficult and philosophically robust space for discussion. Given the abstract nature of the intersection of ethics and robotics, a more detailed consideration and analysis of this space must be left for future research. Important work is currently being done on this subject. But those ethical considerations must not derail ongoing experimentation with intelligent-vehicle technology, which could save many lives and have many other benefits, as already noted. Only through ongoing experimentation and feedback mechanisms can we expect to see constant improvement in how autonomous vehicles respond in these situations to further minimize the potential for accidents and harms. (p. 42-3)

As I noted here in another recent essay, “anything we can do to reduce it significantly is something we need to be pursuing with great vigor, even while we continue to sort through some of those challenging ethical issues associated with automated systems and algorithms.”

No Mention of Alternative Solutions

Finally, it is troubling that neither the 60 Minutes segment nor the Markey report spend any time on alternative solutions to these problems. In my forthcoming law review article, “The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation,” I devote the second half of the 90-page paper to constructive solutions to the sort of complex challenges raised in the 60 Minutes segment and the Markey report.

Many of the solutions I discuss in that paper — such as education and awareness-building efforts, empowerment solutions, the development of new social norms, and so on – aren’t even touched on by the reports. That’s a real shame because those methods could go a long way toward helping to alleviate many of the issues the reports identify.

We need a better public dialogue than this about the future of connected cars and Internet of Things security. Political scare tactics and techno-panic journalism are not going to help make the world a safer place. In fact, by whipping up a panic and potentially discouraging innovation, reports such as these can actually serve to prevent critical, life-saving technologies that could change society for the better.

________________________________

Additional Reading

Making Sure the “Trolley Problem” Doesn’t Derail Life-Saving Innovation, January 15, 2015.

Muddling Through: How We Learn to Cope with Technological Change, June 30, 2014

Law review article: “Removing Roadblocks to Intelligent Vehicles and Driverless Cars,” September 17, 2014.

Law review article: “The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation.”

Ongoing blog series: Moral Panics & Technopanics

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom (2014)

Slide Presentation: Policy Issues Surrounding the Internet of Things & Wearable Technology, September 12, 2014

[Video] Cap Hill Briefing on Emerging Tech Policy Issues (June 2014)

The Growing Conflict of Visions over the Internet of Things & Privacy, January 14, 2012

Can We Adapt to the Internet of Things? IAPP Privacy Perspectives, June 19, 2013

My Filing to the FTC in its ‘Internet of Things’ Proceeding, May 31, 2013

My State of the Net panel on Bitcoin

A couple weeks ago at State of the Net, I was on a panel on Bitcoin moderated by Coin Center’s Jerry Brito. The premise of the panel was that the state of Bitcoin is like the early Internet. Somehow we got policy right in the mid-1990s to allow the Internet to become the global force it is today. How can we reprise this success with Bitcoin today?

In my remarks, I recall making two basic points.

First, in my opening remarks, I argued that on a technical level, the comparison between Bitcoin and the Internet is apt.

What makes the Internet different from the telecommunications media that came before is the separation of an application layer from a transport layer. The transport layer (and the layers below it) does the work of getting bits to where they need to go. This frees anybody up to develop new applications on a permissionless basis, taking this transport capability basically for granted.

Earlier telecom systems did not function this way. The applications were jointly defined with the transport mechanism. Phone calls are defined in the guts of the network, not at the edges.

Like the Internet, Bitcoin separates out not a transport layer, but a fiduciary layer, from the application layer. The blockchain gives applications access to a fiduciary mechanism that they can take basically for granted.

No longer will fiduciary applications (payments, contracts, asset exchange, notary services, voting, etc.) and fiduciary mechanisms need to be developed jointly. Unwieldy fiduciary mechanisms (banks, legal systems, oversight) will be able to be replaced with computer code.

Second, in the panel’s back and forth, particularly with Chip Poncy, I argued that technological change may necessitate a rebalancing of our laws and regulations on financial crimes.

We have payment systems because they improve human welfare. We have laws against certain financial activities because those activities harm human welfare. Ideally, we would balance the gains against the losses to come up with the optimal, human-welfare-maximizing level of regulation.

However, when a new technology like the blockchain comes along, the gains from payment freedom increase. People in a permissionless environment will be able to accomplish more than before. This means that we have to redo our balancing calculus. Because the benefits of unimpeded payments are higher, we need to tolerate more harms from unsavory financial activities if our goal remains to maximize human welfare.

Thanks to my co-panelists for a great discussion.

February 9, 2015

Wanted: talented, gritty libertarians who are passionate about technology

Ten or fifteen years ago, when I sat around and thought about what I would do with my life, I never considered directing the technology policy program at Mercatus. It’s not exactly a career track you can get on — not like being a lawyer, a doctor, a professor.

One of the things I loved about Peter Thiel’s book Zero to One is that it is self-consciously anti-track. The book is a distillation of Thiel’s 2012 Stanford course on startups. In the preface, he writes,

“My primary goal in teaching the class was to help my students see beyond the tracks laid down by academic specialties to the broader future that is theirs to create.”

I think he is right. The modern economy provides unprecedented opportunity for people with talent and grit and passion to do unique and interesting things with their lives, not just follow an expected path.

This is great news if you are someone with talent and grit and passion. Average is Over. What you have is valuable. You can do amazing things. We want to work with you, invest in you—maybe even hire you—and unleash you upon the world.

The biggest problem we have is finding you.

There is no technology policy career track, nor would we want there to be one. Frankly, we don’t want someone who needs the comfort and safety of a future that someone else designed for him.

Unfortunately, this also means that there is no defined pool of talented, gritty libertarians who are passionate about technology for Mercatus or our tech policy allies to hire from.

So how are we supposed to find you? We need your help. You need to do two things.

First, get started now.

Just start doing technology policy.

Write about it every day. Say unexpected things; don’t just take a familiar side in a drawn-out debate. Do something new. What is going to be the big tech policy issue two years from now? Write about that. Let your passion show.

The tech policy world is small enough — and new ideas rare enough — that doing this will get you a following in our community.

It also sends a very strong signal come interview time. Anybody can say that they are talented, or gritty, or passionate. You’ll be able to show it.

I literally got hired because of a blog post. There were other helpful inputs, of course — credentials, references, some contract work that turned out well. But what initially got me on Mercatus’s radar screen was a single post.

Wonderful insight RT @elidourado: Can the War on Drugs bootstrap Bitcoin? http://t.co/EQ68CtL

— Jerry Brito (@jerrybrito) June 4, 2011

Second, get in touch.

Everyone on the Mercatus tech policy team is highly Googleable (on Twitter, here’s me, Adam, Brent, and Andrea). We want to know who you are, what you are doing, and what your plans are.

There is almost no downside to this.

Best case scenario: we create a position for you. No one on our team was hired to fill a vacancy. Instead, we hire people because it’s too good of an opportunity for us to pass up.

Alternatively, maybe we’ll pay you to write a paper or a book.

If for some reason you’re not a great fit for Mercatus, we can connect you with allied groups in tech policy. My discussions with people running other tech policy programs confirms that finding talent is an ever-present problem for them, too.

And at a minimum, we’ll know who you are when we see your work online.

We are serious about winning the battle of ideas over technology, but we can’t do it alone. As technology policy eats the world, the opportunities in our field are going to grow. Let us know if you want to get in on this.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower