Adam Thierer's Blog, page 33

October 27, 2016

Title II, Broadcast Regulation, and the First Amendment

Title II allows the FCC to determine what content and media Internet access providers must transmit on their own private networks, so the First Amendment has constantly dogged the FCC’s “net neutrality” proceedings. If the Supreme Court agrees to take up an appeal from the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, which rejected a First Amendment challenge this summer, it will likely be because of Title II’s First Amendment deficiencies.

Title II has always been about handicapping ISPs qua speakers and preventing ISPs from offering curated Internet content. As former FCC commissioner Copps said, absent the Title II rules, “a big cable company could block access to an investigative report about its less-than-stellar customer service.” Tim Wu told members of Congress that net neutrality was intended to prevent ISPs from favoring, say, particular news sources or sports teams.

But just as a cable company chooses to offer some channels and not others, and a search engine chooses to promote some pages and not others, choosing to offer a curated Internet to, say, children, religious families, or sports fans involves editorial decisions. As communications scholar Stuart Benjamin said about Title II’s problem, under current precedent, ISPs “can say they want to engage in substantive editing, and that’s enough for First Amendment purposes.”

Title II – Bringing Broadcast Regulation to the Internet

Title II regulation of the Internet is frequently compared to the Fairness Doctrine, which activists used for decades to drive conservatives out of broadcast radio and TV. As a pro-net neutrality media professor explained in The Atlantic last year, the motivation for the Fairness Doctrine and Title II Internet regulation are the same: to “rescue a potentially democratic medium from commercial capture.” This is why there is almost perfect overlap between the organizations and advocates who support the Fairness Doctrine and those who lobbied for Title II regulation of the Internet.

These advocates know that FCC regulation of media has proceeded in similar ways for decades. Apply the expansive “gatekeeper” label to a media distributor and then the FCC will regulate distributor operations, including the content transmitted. Today, all electronic media distributors–broadcast TV and radio, satellite TV and radio, cable TV, and ISPs–whether serving 100 customers or 100 million customers, are considered “gatekeepers” and their services and content are subject to FCC intervention.

With broadband convergence, however, the FCC risked losing the ability to regulate mass media. Title II gives the FCC direct and indirect authority to shape Internet media like it shapes broadcast media. In fact, Chairman Wheeler called the Title II rules “must carry–updated for the 21st century.”

The comparison is apt and suggests why the FCC can’t escape the First Amendment challenges to Title II. Must-carry rules require cable TV companies to transmit all local broadcast stations to their cable TV subscribers. Since the must-carry rules prevent the cable operator editorial discretion over their own networks, the Supreme Court held in Turner I that the rules interfered with the First Amendment rights of cable operators.

But the Communications Act Allows Internet Filtering

Internet regulation advocates faced huge problem, though. Unlike other expansions of FCC authority into media, Congress was not silent about regulation of the Internet. Congress announced a policy in the 1996 update to the Communications Act that Internet access providers should remain “unfettered by State and Federal regulation.”

Regulation advocates dislike Section 230 because of its deregulatory message and because it expressly allows Internet access providers to filter the Internet.

Professor Yochai Benkler, in agreement with Lawrence Lessig, noted that Section 230 gives Internet access providers editorial discretion. Benkler warned that because of 230, “ISPs…will interject themselves between producers and users of information.” Further, these “intermediaries will be reintroduced not because of any necessity created by the technology, or because the medium requires a clearly defined editor. Intermediaries will be reintroduced solely to acquire their utility as censors of morally unpalatable materials.”

Professor Jack Balkin noted likewise that “…§ 230(c)(2) immunizes [ISPs] when they censor the speech of others, which may actually encourage business models that limit media access in some circumstances.”

Even the FCC acknowledges the consumer need for curated services and says in the Open Internet Order that Title II providers can offer “a service limited to offering ‘family friendly’ materials to end users who desire only such content.”

While that concession represents a half-hearted effort to bring the Order within compliance of Section 230, it simply exposes the FCC to court scrutiny. Allowing “family friendly” offers but not other curated offers is content-based distinction. Under Supreme Court RAV v. City of St. Paul, “[c]ontent-based regulations are presumptively invalid.” Further, the Supreme Court said in US v. Playboy, content-based burdens must satisfy the same scrutiny as content-based bans on content.

Circuit Split over the First Amendment Rights of Common Carriers

Hopefully the content-based nature of the Title II regulations are reason enough for the Supreme Court to take up an appeal. Another reason is that there is now a circuit split regarding the extent of First Amendment protections for common carriers.

The DC Circuit said that the FCC can prohibit content blocking because ISPs have been labeled common carriers.

In contrast, other courts have held that common carriers are permitted to block content on common carrier lines. In Information Providers Coalition v. FCC, the 9th Circuit held that common carriers “are private companies, not state actors…and accordingly are not obliged to continue…services of particular subscribers.” As such, regulated common carriers are “free under the Constitution to terminate service” to providers of offensive content. The Court relied on its decision a few years earlier in Carlin Communications v. Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company that when a common carrier phone company is connecting thousands of subscribers simultaneously to the same content, the “phone company resembles less a common carrier than it does a small radio station” with First Amendment rights to block content.

Similarly, the 4th Circuit in Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Co. v. US held that common carrier phone companies are First Amendment speakers when they bundle and distribute TV programming, and that a law preventing such distribution “impairs the telephone companies’ ability to engage in a form of protected speech.”

The full DC Circuit will be deciding whether to take up the Title II challenges. If the judges decline review, the Supreme Court would be the final opportunity for a rehearing. If appeal is granted, the First Amendment could play a major role. The Court will be faced with a choice: Should the Internet remain “unfettered” from federal regulation as Congress intended? Or is the FCC permitted to perpetuate itself by bringing legacy media regulations to the online world?

September 21, 2016

Why is the FCC Doubling Down on Regulating the TV Industry and Set Top Boxes?

The FCC appears to be dragging the TV industry, which is increasingly app- and Internet-based, into years of rulemakings, unnecessary standards development and oversight, and drawn-out lawsuits. The FCC hasn’t made a final decision but the general outline is pretty clear. The FCC wants to use a 20 year-old piece of routine congressional district pork, calculated to help a now-dead electronics retailer, as justification to regulate today’s TV apps and their licensing terms.

In the 1996 Telecom Act, a provision was added about set top boxes sold by cable and satellite companies. In the FCC’s own words, Section 629 charges the FCC “to assure the commercial availability of devices that consumers use to access multichannel video programming.” The law adds that such devices, boxes, and equipment must be from “manufacturers, retailers, and other vendors not affiliated with any multichannel video programming distributor.” In English: Congress wants to ensure that consumers can gain access to TV programming via devices sold by parties other than cable and satellite TV companies.

The FCC’s major effort to effect this this law did not end well. To create a market for “non-affiliated equipment,” the FCC created rules in 1998 that established the CableCARD technology, a module designed to the FCC’s specifications that could be inserted into “nonaffiliated” set top boxes.

CableCARD was developed and released to consumers, but after years of complex lawsuits and technology dead ends, cable technology had advanced and few consumers demanded CableCARD devices. The results reveal the limits of lawmaker-designed “competition.” In 2010, 14 years after passage of the law and all that hard work, fewer than 1% of pay-TV customers had “unaffiliated” set top boxes.

It’s a strangely specific statute with no analogues for other technology devices. Why was this law created? Multichannel News reporting in 1998 is suggestive.

[Rep.] Bliley, whose district includes the headquarters of electronics retailer Circuit City, sponsored the provision that requires the FCC to adopt rules to promote the retail sale of cable set-top boxes and navigation devices.

So it it was a small addition to the Act, presumably added after lobbying by Circuit City, in order that electronics retailers and device companies could sell more consumer devices.

The good news is that by the law’s straightforward terms and intent, mission: accomplished. Despite CableCARD’s failure, electronics retailers today are selling devices that give consumers access to TV programming. That’s because, increasingly, TV providers are letting their apps do much of the work that set top boxes do. Today, many consumers can watch TV programming by installing a provider’s streaming TV app device of their choice. These devices are manufactured and sold by dozens of companies, like Samsung, Apple, and Google, and retailers (unfortunately, Circuit City shuttered its last stores in 2009 and wasn’t around to benefit).

But the FCC says, no, mission: not accomplished. The interpretative gymnastics necessary to reach this conclusion is difficult to follow. The FCC says “devices and equipment” should be interpreted broadly in order to capture apps made by pay-TV providers. Yet, while “devices and equipment” is broad enough to capture software like apps, it is not broad enough to capture actual devices and equipment, like smartphones, smart TVs, tablets, computers, and Chromecasts that consumers use to access pay-TV programming.

This is quite a forced reading of statutory language. It will certainly create a regulatory mess out of the evolving pay-TV industry, that already has labyrinthine regulations.

But if you look at the history of FCC regulation, and TV regulation in particular, it’s pretty unexceptional. Advocates for FCC regulation have long seen a competitive and vibrant TV marketplace as a threat to the agency’s authority.

As former FCC chairman Newton Minow warned in his 1995 book, Abandoned in the Wasteland, the FCC would lose its ability to regulate TV if it didn’t find new justifications:

A television system with hundreds or thousands of channels—especially channels that people pay to watch—not only destroys the notion of channel scarcity upon which the public-trustee theory rests but simultaneously breathes life and logic into the libertarian model.

Minow advocated, therefore, that the FCC needed to find alternative reasons to retain some control of the TV industry, including affordability, social inclusiveness, education of youth, and elimination of violence. The FCC has simply discovered another manufactured crisis in TV–“monopoly control” [sic] of set top boxes by TV distributors.

The FCC’s blinkered view of the TV industry is necessary because the US TV and media marketplace is blossoming. Consumers have never had more access to programming and more choice of content and providers. More than 100 standalone streaming video-on-demand products launched in 2015 alone and the major TV providers are going where consumers are and launching their own streaming apps. The market won’t develop perfectly to the Commissioners’ liking and there will be hiccups, but competition is vigorous, output and quality are high, and consumers are benefiting.

The FCC decision to devote dozens of highly-educated agency staff and countless hours of labor in the future defending its decision from court challenge to an arcane consumer issue with such cynical origins is a lamentable waste of agency resources.

This an agency that for decades has done a hundred things poorly instead of doing a handful of things well. (Commissioner Pai has some useful ideas about infrastructure reforms and Commissioner Rosenworcel has an interesting proposal, that I’ve written about, to deploy federal spectrum into commercial markets). Let’s hope the agency leadership reassesses the necessity the this proceeding before dragging the TV industry into another wild goose chase.

Related research: This week Mercatus released a paper by MA Economics Fellow Joe Kane and me about the FCC’s reinvention as a social and cultural regulator: “The FCC and Quasi–Common Carriage A Case Study of Agency Survival.”

September 20, 2016

DOT’s Driverless Cars Guidance: Will “Agency Threats” Rule the Future?

Today, the U.S. Department of Transportation released its eagerly-awaited “Federal Automated Vehicles Policy.” There’s a lot to like about the guidance document, beginning with the agency’s genuine embrace of the potential for highly automated vehicles (HAVs) to revolutionize this sector and save thousands of lives annually in the process.

It is important we get HAV policy right, the DOT notes, because, “35,092 people died on U.S. roadways in 2015 alone” and “94 percent of crashes can be tied to a human choice or error.” (p. 5) HAVs could help us reverse that trend and save thousands of lives and billions in economic costs annually. The agency also documents many other benefits associated with HAVs, such as increasing personal mobility, reducing traffic and pollution, and cutting infrastructure costs.

I will not attempt here to comment on every specific recommendation or guideline suggested in the new DOT guidance document. I could nit-pick about some of the specific recommended guidelines, but I think many of the guidelines are quite reasonable, whether they are related to safety, security, privacy, or state regulatory issues. Other issues need to be addressed and CEI’s Marc Scribner does a nice job documenting some of them is his response to the new guidelines.

Instead of discussing those specific issues today, I want to ask a more fundamental and far-reaching question which I have been writing about in recent papers and essays: Is this guidance or regulation? And what does the use of informal guidance mechanisms like these signal for the future of technological governance more generally?

When Is “Voluntary” Really Mandatory?

The surreal thing about DOT’s new driverless car guidance is how the agency repeatedly stresses it “is not mandatory” and that the guidelines are voluntary in nature but then — often in the same paragraph or sentence — the agency hints how it might convert those recommendations into regulations in the near future. Consider this paragraph on pg. 11 of the DOT’s new guidance document:

The Agency expects to pursue follow-on actions to this Guidance, such as performing additional research in areas such as benefits assessment, human factors, cybersecurity, performance metrics, objective testing, and others as they are identified in the future. As discussed, DOT further intends to hold public workshops and obtain public comment on this Guidance and the other elements of the Policy. This Guidance highlights important areas that manufacturers and other entities designing HAV systems should be considering and addressing as they design, test, and deploy HAVs. This Guidance is not mandatory. NHTSA may consider, in the future, proposing to make some elements of this Guidance mandatory and binding through future regulatory actions. This Guidance is not intended for States to codify as legal requirements for the development, design, manufacture, testing, and operation of automated vehicles. Additional next steps are outlined at the end of this Guidance. [emphasis added.]

The agency continues on to request that “manufacturers and other entities voluntarily provide reports regarding how the Guidance has been followed,” but then notes how “[t]his reporting process may be refined and made mandatory through a future rulemaking.” (p. 15)

And so it goes throughout the DOT’s new “guidance” document. With one breath the DOT suggests that everything is informal and voluntary; with the next it suggests that some form of regulation could be right around the proverbial corner.

Agency Threats Are the Future of Technological Governance

What’s going on here? In essence, DOT’s driverless car guidance is another example of how “soft law” and “agency threats” are becoming the dominant governance models for fast-paced emerging technology.

As noted by Tim Wu, a proponent of such regimes, these agency threats can include “warning letters, official speeches, interpretations, and private meetings with regulated parties.” “Soft law” simply refers to any sort of informal governance mechanism that agencies might seek to use to influence private decision-making or in this case the future course of technological innovation.

The problem with agency threats, as my former Mercatus Center colleague Jerry Brito pointed out in a 2014 law review article, is that they are fundamentally undemocratic and represent a betrayal of the rule of law. The use of “threat regimes,” Brito argued, “places undue power in the hands of regulators unconstrained by predictable procedures.” Such regimes breed uncertainty by leaving decisions up to the whim of regulators who will be unconstrained by administrative procedures, legal precedents, and strict timetables. “[B]ecause it has no limiting principle,” Brito concluded, the agency threats model “leaves the regulatory process without much meaning” and “would obviously be ripe for abuse.”

The danger exists that we are witnessing gradual mission creep as the DOT’s “guidance” process slowly moves from being a truly voluntary self-certification process to something more akin to a pre-market approval process. Every “informal” request that DOT makes — even when those requests are just presented in the form of vague questions — opens the door to greater technocratic meddling in the innovation process by federal bureaucrats.

Coping with the Pacing Problem

Why are agencies like the DOT adopting this new playbook? In a nutshell, it comes down to the realization on their part that the “pacing problem” is now an undeniable fact of life.

I discussed the pacing problem at length in my recent review of Wendell Wallach’s important new book, A Dangerous Master: How to Keep Technology from Slipping beyond Our Control. Wallach nicely defined the pacing problem as “the gap between the introduction of a new technology and the establishment of laws, regulations, and oversight mechanisms for shaping its safe development.” “There has always been a pacing problem,” Wallach noted, but like other philosophers, he believes that modern technological innovation is occurring at an unprecedented pace, making it harder than ever to “govern” it using traditional legal and regulatory mechanisms.

Which is exactly why the DOT and whole lot of other agencies are now defaulting to soft law and agencies threat models as their old regimes struggle to keep up with the pace of modern technological innovation. As the DOT put it in its new guidance document: “The speed with which HAVs are advancing, combined with the complexity and novelty of these innovations, threatens to outpace the Agency’s conventional regulatory processes and capabilities.” (p. 8) More specifically, the agency notes that:

The remarkable speed with which increasingly complex HAVs are evolving challenges DOT to take new approaches that ensure these technologies are safely introduced (i.e., do not introduce significant new safety risks), provide safety benefits today, and achieve their full safety potential in the future. To meet this challenge, we must rapidly build our expertise and knowledge to keep pace with developments, expand our regulatory capability, and increase our speed of execution. (p. 6)

Rarely has any agency been quite so blunt about how it is racing to get ahead of the pacing problem before it completely loses control of the future course of technological innovation.

But the DOT is hardly alone in its increased reliance on soft law governance mechanisms. In fact, I’m in the early research stages of a new paper about what soft law and agency threat models mean for the future of emerging technology and its governance. In that paper, I hope to document how many different agencies (FAA, FDA, FTC, FCC, NTIA, & DOT among others) are using some variant of soft law model to informally regulate the growing universe of emerging technologies out there today (commercial drones, connected medical devices, the Internet of Things, 3D printing, immersive technology, the sharing economy, driverless cars, and more.)

If nothing else, I would like to devise a taxonomy of soft law/agency threat models and then discuss the upsides and downsides of those models. If anyone has recommendations for additional reading on this topic, please let me know. The best thing I have seen on the issue is a 2013 book of collected essays on Innovative Governance Models for Emerging Technologies, edited by Gary E. Marchant, Kenneth W. Abbott and Braden Allenby. I’m surprised more hasn’t been written about this in law reviews or political science journals.

What Does It Mean for Innovation? And Accountable Government?

So, what does all this mean for the future of driverless cars, autonomous systems, and other emerging technologies? I think it’s both good and bad news.

The good news — at least from the perspective of those of us who want to see innovators freed up to experiment more without prior restraint — is that the technological genie is increasingly out of the bottle. Technology regulators are at an impasse and they know it. Their old regulatory regimes are doomed to always be one step behind the action. Thus, a lot of technological innovation is going to be happening before any blessing has been given to engage in those experiments.

The bad news is that the regulatory regimes of the future will become almost hopelessly arbitrary in terms of their contours and enforcement ceiling. Basically, in our new world of soft law and agency threats, you can tear up the Administrative Procedures Act and throw it out the window. When regulatory agencies act in the future, they will do so in a sort of extra-legal Twilight Zone, where things are not always as they seem. Agencies will increasingly act like nagging nannies, constantly pressuring innovators to behave themselves. And sometimes that nagging will work, and sometimes it will even improve consumer welfare at the margin! It will work sometimes precisely because government still wields a mighty big hammer and no innovator wants to be nailed to the ground in the courts, or the court of public opinion for that matter. Thus, many — not all, but many — of those innovators will go along with whatever agencies like DOT suggests as “best practices” even if those guidelines are horribly misguided or have no force of law whatsoever. And because agencies know that many (perhaps most) innovators will fall in line with whatever “best practices” or “codes of conduct” that they concoct, it will reinforce the legitimacy of this model and become the new method of imposing their will on current or emerging technology sectors.

Again, agency threats won’t always work because some innovators will continue to engage in rough forms of “technological civil disobedience” and just ignore a lot of these informal guidelines and agency threats. Agencies will push back and seek to make an example of specific innovators (especially the ones with deep pockets) in order to send a message to every other innovator out there that they better fall in line or else!

But what that “or else!” moment or action looks like remains completely unclear. The problem with soft law is that, by its very nature, it is completely open-ended and fundamentally arbitrary. It is really just “non-law law.” That’s the “legal regime” that will “govern” the emerging technologies of the present and the future.

Isn’t Soft Law Better Than the Alternative?

Now, here’s the funny thing about this messy, arbitrary, unaccountable world of soft law and agency threats: It is probably a hell of lot better than the old world we used to live in!

The old analog era regulatory systems were very top-down and command-and-control in orientation. These traditional regimes were driven by the desire of regulators to enforce policy priorities by imposing prior restraints on innovation and then selectively passing out permission slips to get around those rules.

As I noted in my latest book, the problem with those traditional regulatory systems is that they “tend to be overly rigid, bureaucratic, inflexible, and slow to adapt to new realities. They focus on preemptive remedies that aim to predict the future, and future hypothetical problems that may not ever come about. Worse yet, administrative regulation generally preempts or prohibits the beneficial experiments that yield new and better ways of doing things.” (Permissionless Innovation, p. 120)

For all the reasons I outlined in my book and other papers on these topics, “permissionless innovation” remains the superior policy default compared to precautionary principle-based prior restraints. But I am not so naïve as to expect that permissionless innovation will prevail in the policy world all of the time. Moreover, I am not one of those technological determinists who goes around saying that technology is an unstoppable force that relentlessly drives history, regardless of what policymakers say. I am more of a soft determinist who believes that technology often can be a major driver of history, but not without a significant shaping from other social, cultural, economic, and political forces.

Thus, as much as I worry about the new “soft law/agency threats” regime being arbitrary, unaccountable, and innovation-threatening, I know that the ideal of permissionless innovation will only rarely be our default policy regime. But I also don’t think we are going back the old regulatory regimes of the past and we absolutely wouldn’t want to anyway in light of the deleterious impacts those regimes had on innovation in practice.

The best bet for those of us who care about the freedom to innovate is to make sure that these soft law governance mechanisms have some oversight from Congress (unlikely) and the Courts (more likely) when agencies push too far with informal agency threats. Better yet, we can hope that the pace of technological change continues to accelerate and pressures agencies to only intervene to address the most pressing problems and then largely leaves the rest of the field wide open for continued experimentation with new and better ways of doing things.

But make no doubt about it, as today’s DOT guidance document for driverless cars makes clear, “agency threats” will increasingly shape the future of emerging technologies whether we like it or not.

August 26, 2016

Which Emerging Technologies are “Weapons of Mass Destruction”?

On Tuesday, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon delivered an address to the UN Security Council “on the Non-Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction.” He made many of the same arguments he and his predecessors have articulated before regarding the need for the Security Council “to develop further initiatives to bring about a world free of weapons of mass destruction.” In particular, he was focused on the great harm that could come about from the use of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. “Vicious non-state actors that target civilians for carnage are actively seeking chemical, biological and nuclear weapons,” the Secretary-General noted. A stepped-up disarmament agenda is needed, he argued, “to prevent the human, environmental and existential destruction these weapons can cause . . . by eradicating them once and for all.”

On Tuesday, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon delivered an address to the UN Security Council “on the Non-Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction.” He made many of the same arguments he and his predecessors have articulated before regarding the need for the Security Council “to develop further initiatives to bring about a world free of weapons of mass destruction.” In particular, he was focused on the great harm that could come about from the use of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. “Vicious non-state actors that target civilians for carnage are actively seeking chemical, biological and nuclear weapons,” the Secretary-General noted. A stepped-up disarmament agenda is needed, he argued, “to prevent the human, environmental and existential destruction these weapons can cause . . . by eradicating them once and for all.”

The UN has created several multilateral mechanisms to pursue those objectives, including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Biological Weapons Convention. Progress on these fronts has always been slow and limited, however. The Secretary-General observed that nuclear non-proliferation efforts have recently “descended into fractious deadlock,” but the effectiveness of those and similar UN-led efforts have long been challenged by the dual realities of (1) rapid ongoing technological change that has made WMDs more ubiquitous than ever, plus (2) a general lack of teeth in UN treaties and accords to do much to slow those advances, especially among non-signatories.

Despite those challenges, the Secretary-General is right to remain vigilant about the horrors of chemical, biological and nuclear attacks. But what was interesting about this address is that the Secretary-General continued on to discuss his concerns about a rising class of emerging technologies, which we usually don’t hear mentioned in the same breath as those traditional “weapons of mass destruction”:

I will now say a few words about new global threats emerging from the misuse of science and technology, and the power of globalization. Information and communication technologies, artificial intelligence, 3D printing and synthetic biology will bring profound changes to our everyday lives and benefits to millions of people. However, their potential for misuse could also bring destruction. The nexus between these emerging technologies and WMD needs close examination and action.

As a starting point, the international community must step up to expand common ground for the peaceful use of cyberspace and, particularly, the intersection between cyberspace and critical infrastructure. People now live a significant portion of their lives online. They must be protected from online attacks, just as effectively as they are protected from physical attacks.

Disarmament and non-proliferation instruments are only as successful as Member States’ capacity to implement them.

And the Secretary-General concluded by calling on “all Member States to re-commit themselves and to take action. The stakes are simply too high to ignore.”

The Secretary-General’s inclusion of all these emerging technologies in a speech about WMDs and the dangers of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons raises an interesting question: Are all these things actually equivalent? Does a danger exist from the continued evolution of ICTs, AI, 3D printing, and synthetic biology that is equal to the very serious threat posed by chemical, biological and nuclear weapons?

On one hand, it is tempting to say, Yes! If nothing else, most of us have seen more than enough techno-dystopian Hollywood plots through the years to understand the hypothetical dangers that some of these technologies pose. But even if (like me) you dismiss most of the movie plots as far-fetched Chicken Little-ism meant to drum up big box office, plenty of serious scholars out there have sketched out more credible pictures of the threat some of these new technologies might pose to humanity. Information platforms can be hacked and our personal data or security compromised. 3D printers can be used to create cheap, undetectable firearms. Robotics and autonomous systems can be programmed to kill. Synthetic biology might help create genetically-modified super-soldiers. And so on.

These are serious questions with profound ramifications and I discussed them at much greater length in my lengthy review of Wendell Wallach’s important book, A Dangerous Master: How to Keep Technology from Slipping beyond Our Control. Like many other books and essays on these technologies, Wallach champions “the need for more upstream governance” as in “more control over the way that potentially harmful technologies are developed or introduced into the larger society. Upstream management is certainly better than introducing regulations downstream, after a technology is deeply entrenched or something major has already gone wrong,” he suggests. “Yet, even when we can access risks, there remain difficulties in recognizing when or determining how much control should be introduced. When does being precautionary make sense, and when is precaution an over-reaction to the risks?”

Indeed, that is the right question, and quite a profound one. The problem associated with all such “upstream governance” and preemptive controls on emerging technologies is determining how to avoid hypothetical future risks without destroying the potential for these same technologies to be used in life-enriching and even life-saving ways.

Solutions are illusive and involve myriad trade-offs. More generally, it’s not even clear that they would be workable. That is especially true when you expand the scale of governance to include the entire planet. It seems unlikely, for example, that a hypothetical UN-led Synthetic Biology Non-Proliferation Treaty, 3D-Printed Weapons Convention, or Agreement on the Peaceful Use of Cyberspace are going to be workable solutions in a world where these technologies are so radically decentralized and proliferating so rapidly. At least with some of the older technologies, the underlying materials were somewhat harder to obtain, manufacture, weaponize, and then distribute/use. But the same is not true of many of these newer technologies. It’s a heck of lot easier to get access to a computer and 3D printer than uranium and enrichment facilities, for example.

Moreover, when we discuss the risks associated with emerging technologies compared to past technologies, there needs to be some sort of weighing of the actual probability of serious harm coming about. In the expanded Second Edition of my Permissionless Innovation book, I tried to offer a rough framework for when formal precautionary regulation (i.e., operational restrictions, licensing requirements, research limitations, or even formal bans) might be necessary. In a section of Chapter 3 of my book entitled, “When Does Precaution Make Sense?” I argued that:

Generally speaking, permissionless innovation should remain the norm in the vast majority of cases, but there will be some scenarios where the threat of tangible, immediate, irreversible, catastrophic harm associated with new innovations could require at least a light version of the precautionary principle to be applied. In these cases, we might be better suited to think about when an “anti-catastrophe principle” is needed, which narrows the scope of the precautionary principle and focuses it more appropriately on the most unambiguously worst-case scenarios that meet those criteria.

“But most [emerging technology] cases don’t fall into this category,” I concluded. It is simply not the case that most emerging technologies pose the same sort of tangible, immediate, irreversible, catastrophic, and highly probably risk that traditional “weapons of mass destruction” do.

And that gets at my problem with that recent address by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. By so casually moving from a heated discussion of traditional WMDs into a brief discussion about the potential risks associated with ICTs, AI, 3D printing and synthetic biology, I really worry about the sort of moral equivalence that some might read into this speech. Again, these things, and the threats they pose, are simply not the same. Yet, when the UN Secretary-General sandwiches these technologies in between impassioned opening and closing statements about the need “to take action” because “the stakes are simply too high to ignore,” it seems to suggest he is prepared to speak of them all in the same breath as traditional “weapons of mass destruction” and suggest similar global control efforts are needed. I do not believe that is sensible.

Does this mean we just throw our hands up in the air and give up any inquiry into the matter? Of course not. As I noted in my review of Wallach’s book, some very sensible “soft law” approaches exist that are worth pursuing. Soft law approaches can include a wide variety of efforts to “bake a dose of precautionary directly into the innovation process through a wide variety of informal governance/oversight mechanisms,” as I noted in my review of Wallach’s book. “By embedding shared values in the very design of new tools and techniques, engineers improve the prospect of a positive outcome,” Wallach says in his book.

Many soft law or informal governance systems already exist in the forms of so-called “multistakeholder governance” systems, informal industry codes of conduct, best practices, and other coordinating mechanisms. But these solutions would likely fall short of addressing some extreme scenarios that many people are worried about. Toward that end, when the case can be made that a particular application of a new general purpose technology will result in tangible, immediate, irreversible, catastrophic, and highly probably dangers, then perhaps some international action should be considered. For example, a case can be made that governments (and perhaps even the UN) should do more to preemptively curb the most nefarious uses of robotics. There’s already a major effort underway called the “Campaign to Stop Killer Robots” that seeks a multinational treaty to stop deadly uses of robotics. Again, I’m not sure how enforcement will work, but I think it’s worth investigating how some of the uses of “killer robots” might be limited through international accords and actions. Moreover, I could imagine an extension of existing the UN’s Biological Weapons Convention framework to cover some synthetic biology applications that involve extreme forms of human modification.

That being said, policymakers and international figures of importance like UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon should be extremely cautious about the language they use to describe new classes of technologies lest they cast too wide a net with calls for controlling “weapons of mass destruction” that may be nothing of the sort.

Additional Reading

“Wendell Wallach on the Challenge of Engineering Better Technology Ethics“

“On the Line between Technology Ethics vs. Technology Policy“

“What Does It Mean to “Have a Conversation” about a New Technology?”

“Making Sure the “Trolley Problem” Doesn’t Derail Life-Saving Innovation”

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom

August 25, 2016

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Drone Delivery Edition

Just three days ago I penned another installment in my ongoing series about the growing phenomenon of “global innovation arbitrage” — or the idea that “innovators can, and increasingly will, move to those countries and continents that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.” And now it’s already time for another entry in the series!

Just three days ago I penned another installment in my ongoing series about the growing phenomenon of “global innovation arbitrage” — or the idea that “innovators can, and increasingly will, move to those countries and continents that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.” And now it’s already time for another entry in the series!

My previous column focused on driverless car innovation moving overseas, and earlier installments discussed genetic testing, drones, and the sharing economy. Now another drone-related example has come to my attention, this time from New Zealand. According to the New Zealand Herald:

Aerial pizza delivery may sound futuristic but Domino’s has been given the green light to test New Zealand pizza delivery via drones. The fast food chain has partnered with drone business Flirtey to launch the first commercial drone delivery service in the world, starting later this year.

Importantly, according to the story, “If it is successful the company plans to extend the delivery method to six other markets – Australia, Belgium, France, The Netherlands, Japan and Germany.” That’s right, America is not on the list. In other words, a popular American pizza delivery chain is looking overseas to find the freedom to experiment with new delivery methods. And the reason they are doing so is because of the seemingly endless bureaucratic foot-dragging by federal regulators at the FAA.

Some may scoff and say, ‘Who cares? It’s just pizza!’ Well, even if you don’t care about innovation in the field of food delivery, how do you feel about getting medicines or vital supplies delivered on a more timely and efficient basis in the future? What may start as a seemingly mundane or uninteresting experiment with pizza delivery through the sky could quickly expand to include a wide range of far more important things. But it will never happen unless you give innovators a little breathing room–i.e., “permissionless innovation”–to try new and different ways of doing things.

Incidentally, Flirtey, the drone deliver company that Domino’s partnered with in New Zealand, is also an American-based company. On the company’s website, the firm notes that: “Drones can be operated commercially in a growing number of countries. We’re in discussions with regulators all around the world, and we’re helping to shape the regulations and systems that will make drone delivery the most effective, personal and frictionless delivery method in the market.”

That’s just another indication of the reality that global innovation arbitrage is at work today. If the U.S. puts it head in the sand and lets bureaucrats continue to slow the pace of progress, America’s next generation of great innovators will increasingly look offshore in search of patches of freedom across the planet where they can try out their exciting new products and services.

BTW, I wrote all about this in Chapter 3 of my Permissionless Innovation book. And here’s some additional Mercatus research on the topic.

Additional Reading

How to Destroy American Innovation: The FAA & Commercial Drones, Oct. 6, 2014

Permissionless Innovation & Commercial Drones, February 4, 2015.

DRM for Drones Will Fail, January 28, 2015.

Regulatory Capture: FAA and Commercial Drones Edition, January 16, 2015.

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Commercial Drones & Sharing Economy Edition, December 9, 2014.

Filing to FAA on Drones & “Model Aircraft”, Sept. 23, 2014

Private Drones & the First Amendment, Sept. 19, 2014

[TV interview] The Beneficial Uses of Private Drones, March 28, 2014

Comments of the Mercatus Center to the FAA on integration of drones into the nation’s airspace, April 23, 2o13

Eli Dourado, Deregulate the Skies: Why We Can’t Afford to Fear Drones, Wired, April 23, 2013

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom (2014)

[Video] Cap Hill Briefing on Emerging Tech Policy Issues (June 2014)

August 22, 2016

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Driverless Cars Edition

In previous essays here I have discussed the rise of “global innovation arbitrage” for genetic testing, drones, and the sharing economy. I argued that: “Capital moves like quicksilver around the globe today as investors and entrepreneurs look for more hospitable tax and regulatory environments. The same is increasingly true for innovation. Innovators can, and increasingly will, move to those countries and continents that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.” I’ve been working on a longer paper about this with Samuel Hammond, and in doing research on the issue, we keep finding interesting examples of this phenomenon.

The latest example comes from a terrific new essay (“Humans: Unsafe at Any Speed“) about driverless car technology by Wall Street Journal technology columnist L. Gordon Crovitz. He cites some important recent efforts by Ford and Google and he notes that they and other innovators will need to be given more flexible regulatory treatment if we want these life-saving technologies on the road as soon as possible. “The prospect of mass-producing cars without steering wheels or pedals means U.S. regulators will either allow these innovations on American roads or cede to Europe and Asia the testing grounds for self-driving technologies,” Crovitz observes. “By investing in autonomous vehicles, Ford and Google are presuming regulators will have to allow the new technologies, which are developing faster even than optimists imagined when Google started working on self-driving cars in 2009.”

Alas, regulators at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration are more likely to continue to embrace a heavy-handed and highly precautionary regulatory approach instead of the sort of “permissionless innovation” approach to policy that could help make driverless cars a reality sooner rather than later. If regulators continue to take that path, it could influence the competitive standing of the U.S. in the race for global supremacy in this arena.

Crovitz cites a recent essay by innovation consultant Chunka Mui’s on this point: “The appropriate first-mover unit of innovation is not the car, or even the car company. It is the nation.” Mui uses the example of Singapore, where “the lead government agency [is] working to enhance Singapore’s position as a global business center” and has been inviting self-driving car developers to work with the island nation to avoid what Mui describes as “the tangled web of competition, policy fights, regulatory hurdles and entrenched interests governing the pace of driverless-car development and deployment in the U.S.”

That’s global innovation arbitrage in a nutshell and it would be a real shame if America was on the losing end of this competition. To make sure we’re not, Crovitz notes that U.S. policymakers need to avoid overly-precautionary “pre-market-approval steps” that “would give bureaucrats the power to pick which technologies can develop and which are banned. If that happens,” he notes, “the winner in the race to the next revolution in transportation is likelier to be Singapore than Detroit or Silicon Valley.”

Too true. Let’s hope that policymakers are listening before it’s too late.

Additional Reading:

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Commercial Drones & Sharing Economy Edition

Global Innovation Arbitrage: Genetic Testing Edition

“Removing Roadblocks to Intelligent Vehicles and Driverless Cars” [law review article with Ryan Hagemann]

How Many Accidents Could Be Averted This Holiday if More Intelligent Cars Were on the Road?

Driverless Cars, Privacy & Security: Event Video & Talking Points

Making Sure the “Trolley Problem” Doesn’t Derail Life-Saving Innovation

Embracing a Culture of Permissionless Innovation

Europe’s Choice on Innovation

Why Permissionless Innovation Matters

Problems with Precautionary Principle-Minded Tech Regulation & a Federal Robotics Commission (9/22/14)

August 16, 2016

No, the Telecom Act didn’t destroy phone and TV competition

I came across an article last week in the AV Club that caught my eye. The title is: “The Telecommunications Act of 1996 gave us shitty cell service, expensive cable.” The Telecom Act is the largest update to the regulatory framework set up in the 1934 Communications Act. The basic thrust of the Act was to update the telephone laws because the AT&T long-distance monopoly had been broken up for a decade. The AV Club is not a policy publication but it does feature serious reporting on media. This analysis of the Telecom Act and its effects, however, omits or obfuscates important information about dynamics in media since the 1990s.

The AV Club article offers an illustrative collection of left-of-center critiques of the Telecom Act. Similar to Glass-Steagall repeal or Citizens United, many on the left are apparently citing the Telecom Act as a kind of shorthand for deregulatory ideology run amuck. And like Glass-Steagall repeal and Citizens United, most of the critics fundamentally misstate the effects and purposes of the law. Inexplicably, the AV Club article relies heavily on a Common Cause white paper from 2005. Now, Common Cause typically does careful work but the paper is hopelessly outdated today. Eleven years ago Netflix was a small DVD-by-mail service. There was no 4G LTE (2010). No iPhone or Google Android (2007). And no Pandora, IPTV, and a dozen other technologies and services that have revolutionized communications and media. None of the competitive churn since 2005, outlined below, is even hinted at in the AV Club piece. The actual data undermine the dire diagnoses about the state of communications and media from the various critics cited in the piece.

Competition in Telephone Service

Let’s consider the article’s provocative claim that the Act gave us “the continuing rise of cable, cellphone, and internet pricing.” Despite this empirical statement, no data are provided to support this. Instead, the article mostly quotes progressive platitudes about the evils of industry consolidation. I suppose platitudes are necessary because on most measures there’s been substantial, measurable improvements in phone and Internet service since the 1990s. In fact, the cost-per-minute of phone service has plummeted, in part, because of the competition unleashed by the Telecom Act. (Relatedly, there’s been a 50-fold increase in Internet bandwidth with no price increase.)

The Telecom Act undid much of the damage caused by decades of monopoly protection of telephone and cable companies by federal and state governments. For decades it was accepted that local telephone and cable TV service were natural monopolies. Regulators therefore prohibited competitive entry. The Telecom Act (mostly) repudiated that assumption and opened the door for cable companies and others to enter the telephone marketplace. The competitive results were transformative. According to FCC data, incumbent telephone companies, the ones given monopoly protection for decades, have lost over 100 million residential subscribers since 2000. Most of those households went wireless only but new competitors (mostly cable companies) have added over 32 million residential phone customers and may soon overtake the incumbents. The chart below breaks out connections by technology (VoIP, wireless, POTs), not incumbency, but the churn between competitors is apparent.

Further, while the Telecom Act was mostly about local landlines, not cellular networks, we can also dispense with the AV Club claim that dominant phone companies are increasing cellphone bills. Again, no data are cited. In fact, in quality-adjusted terms, the price of cell service has plummeted. In 1999, for instance, a typical cell plan was for regional coverage and offered 200 voice minutes for about $55 per month (2015 dollars). Until about 2000, there was no texting (1999 was the first year texting between carriers worked) and no data included. In comparison, for that same price today you can find a popular plan that includes, for all of North America, unlimited texting and voice minutes, plus 10 GB of 4G LTE data. Carriers spend tens of billions of dollars annually on maintaining and upgrading cellular networks and as a result, millions of US households are dropping landline connections (voice and broadband) for smartphones alone.

Competition in Television and Media

The criticisms of cable deregulation completely misunderstand and misstate the role of competition in the TV industry. Media quality is harder to measure, but its not a stretch to say that quality is higher than ever. Few dispute that we are in the Golden Age of Media, resulting from the proliferation of niche programming provided by Netflix, podcasts, Hulu, HBO, FX, and others. This virtual explosion in programming came about largely because there are more buyers (distributors) of programming and more cutthroat competition for eyeballs.

Again, the AV Club quotes the Common Cause report: “Roughly 98 percent of households with access to cable are served by only one cable company.” Quite simply this is useless stat. Why do we care how many coaxial cable companies are in a neighborhood? Consumers care about outputs–price, programming, quality, customer service–and number of competitors, regardless of the type of transmission network, which can be cellular, satellite, coaxial cable, fiber, or copper.

Look beyond the contrived “number of coaxial competitors” measure and it’s clear that most cable companies face substantial competition. The Telecom Act is a major source of the additional competition, particularly telco TV. Since passage of the Telecom Act, cable TV’s share of the subscription TV market fell from 95% to nearly 50%.

The Telecom Act repealed a decades-old federal policy that largely prohibited telephone companies from competing with cable TV providers. Not much changed for telco TV until the mid-2000s, when broadband technology improved and when the FCC freed phone companies from “unbundling” rules that forced telcos to lease their networks to competitors at regulated rates. In this investment-friendly environment, telephone companies began upgrading their networks for TV service and began purchasing and distributing programming. Since 2005, telcos have attracted about 13 million households and cable TV’s market share fell from about 70% to 53%. Further, much of consumer dissatisfaction with TV is caused by legacy regulations, not the Telecom Act. If cable, satellite, and phone companies were as free as Netflix and Hulu to bundle, price, and purchase content, we’d see lower prices and smaller bundles.

The AV Club’s focus on Clear Channel [sic] and now-broken up media companies is puzzling and must be because of the article’s reliance on the 2005 Common Cause report. The bête noire of media access organizations circa 2005 was Clear Channel, ostensibly the sort of corporate media behemoth created by the Telecom Act. The hysteria proved unfounded.

Clear Channel broadcasting was rebranded in 2014 to iHeartRadio and its operations in the last decade do not resemble the picture described in the AV Club piece, that of a “radio giant” with “more than 1200 stations.” While still a major player in radio, since 2005 iHeartRadio’s parent company went private, sold all of its TV stations and hundreds of its radio station, and shed thousands of employees. The firm has serious financial challenges because of the competitive nature of the radio industry, which has seen entry from the likes of Pandora, Spotify, Google, and Apple.

The nostalgia for Cold War-era radio is also strange for an article written in the age of Pandora, Spotify, iTunes, and Google Play. The piece quotes media access scholar Robert McChesney about radio in the 1960s:

Fifty years ago when you drove from New York to California, every station would have a whole different sound to it because there would be different people talking. You’d learn a lot about the local community through the radio, and that’s all gone now. They destroyed radio. It was assassinated by the FCC and corporate lobbyists.

This oblique way of assessing competition–driving across the country–is necessary because local competition was actually relatively scarce in the 1960s. There were only about 5000 commercial radio stations in the US, which sounds like a lot except when you consider the choice and competition today. Today, largely because of digital advancements and channel splitting, there are more than 10 times as many available broadcast channels, as well as hundreds of low-power stations. Combined with streaming platforms, competition and choice is much more common today. Everyone in the US can, with an inexpensive 3G plan and a radio, access millions of niche podcasts and radio programs featuring music, hobbies, entertainment, news, and politics.

The piece quotes the 2005 report, alarmed that “just five companies—Viacom, the parent of CBS, Disney, owner of ABC, News Corp, NBC and AOL, owner of Time Warner—now control 75 percent of all primetime viewing.” Again, I don’t understand why the article quotes decade-old articles about market share without updates. There is no mention that Viacom and CBS split up in 2005 and NewsCorp. and Fox split in 2013. The hysteria surrounding NBC, AOL, and Time Warner’s failed commercial relationships has been thoroughly explored and discredited by my colleague Adam Thierer and I’ll point you to his piece. As Adam has also documented, broadcast networks have been losing primetime audience share since at least the late 1970s, first to cable channels, then to streaming video. And nearly all networks, broadcast and cable, are seeing significant drops in audience as consumers turn to Internet streaming and gaming. Market power and profits in media is often short lived.

The article then decries the loss of local and state news reporting. It’s strange to blame the Telecom Act for newspaper woes since shrinking newsrooms is a global, not American, phenomenon with well-understood causes (loss of classifieds and increased competition with Web reporting). And, as I’ve pointed out, the greatest source of local and state reporting is local papers, but the FCC has largely prohibited papers from owning radio and TV broadcasters (which would provide papers a piece of TV’s lucrative ad and retrans revenue) for decades, even as local newspapers downsize and fail.

The article was a fascinating read if only because it reveals how many left-of-center prognostications about media aged poorly. Those on the right have their own problems with the Act, namely its vastly different regulatory regimes (“telecommunications,” “wireless,” “television”) in a world of broadband and convergence. But useful reform means diagnosing what inhibits competition and choice in media and communications markets. Much of the competitive problems in fact arise from the enforcement of natural monopoly restrictions in the past. Media and communications has seen huge quality improvements since 1996 because the Telecom Act rejected the natural monopoly justifications for regulation. The Telecom Act has proven unwieldy but it cannot be blamed for nonexistent problems in phone and TV.

August 11, 2016

The Politics of the ICANN transition

One would think that if there is any aspect of Internet policy that libertarians could agree on, it would be that the government should not be in control of basic internet infrastructure. So why are Tech Freedom and a few other so-called “liberty” groups making a big fuss about the plan to complete the privatization of ICANN? The IANA transition, as it has become known, would set the domain name system root, IP addressing and Internet protocol parameter registries free of direct governmental control, and make those aspects of the Internet transnational and self-governing.

Yet, the same groups that have informed us that net neutrality is the end of Internet freedom because it would have a government agency indirectly regulating discriminatory practices by private sector ISPs, are now trying to tell us that retaining direct U.S. government regulation of the content of the domain name system root, and indirect control of the domain name industry and IP addressing via a contract with ICANN, is essential to the maintenance of global Internet freedom. It’s insane.

One mundane explanation is that TechFreedom, which is known for responding eagerly to anyone offering them a check, has found some funding source that doesn’t like the IANA transition and has, in the spirit of a true political entrepreneur, taken up the challenge of trying to twist, turn and spin freedom rhetoric into some rationalization for opposing the transition. But that doesn’t explain the opposition of Senators Cruz and other conservatives who feign a concern for Internet freedom. No, I think this split represents something bigger. At bottom, it’s a debate about the role of nation-states in Internet governance and the state’s role in preserving freedom.

In this regard it would be good to review my May 2016 blog post at the Internet Governance Project, which smashes the myths being asserted about the US government’s role in ICANN. In it, I show that NTIA’s control of ICANN has never been used to protect Internet freedom, but has been used multiple times to limit or attack it. I show that the US control of the DNS root was never put into place to “protect Internet freedom,” but was established for other reasons, and that the US explicitly rejected putting a free expression clause in ICANN’s constitution. I show that the new ICANN Articles of Incorporation created as part of the transition contain good mission limitations and protections against content regulation by ICANN. Finally, I argued that in the real world of international relations (as opposed to the unilateralist fantasies of conservative nationalists) the privileged US role is a magnet for other governments, inviting them to push for control, rather than a bulwark against it.

Another libertarian tech policy analyst, Eli Dourado, has also argued that going ahead with the IANA transition is a ‘no-brainer.’

Assistant Secretary of Commerce Larry Strickling’s speech at the US Internet Governance Forum last month goes through the FUD being advanced by TechFreedom and the nationalist Republicans one by one. Among other points, he contends that if the U.S. tries to retain control, Internet infrastructure will become increasingly politicized as rival states, such as China, Russia and Iran, argue for a sovereignty-based model and try to get internet infrastructure in the hands of intergovernmental organizations:

Privatizing the domain name system has been a goal of Democratic and Republican administrations since 1997. Prior to our 2014 announcement to complete the privatization, some governments used NTIA’s continued stewardship of the IANA functions to justify their demands that the United Nations, the International Telecommunication Union or some other body of governments take control over the domain name system. Failing to follow through on the transition or unilaterally extending the contract will only embolden authoritarian regimes to intensify their advocacy for government-led or intergovernmental management of the Internet via the United Nations.

The TechFreedom “coalition letter” raises no new arguments or issues – it is a nakedly political appeal for Congress to intervene to stop the transition, based mainly on partisan hatred of the Obama administration. But I think this debate is highly significant nevertheless. It’s not about rational policy argumentation, it’s about the diverging political identity of people who say they are pro-freedom.

What is really happening here is a rift between nationalist conservativism of the sort represented by the Heritage Foundation and the nativists in the Tea Party, on the one hand, and true free market libertarians, on the other. The root of this difference is a radically different conception of the role of the nation-state in the modern world. Real libertarians see national borders as, at best, administrative necessary evils, and at worst as unjustifiable obstacles to society and commerce. A truly classical liberal ethic is founded on individual rights and a commitment to free and open markets and free political institutions everywhere, and thus is universalist and globalist in outlook. They see the economy and society as increasingly globalized, and understand that the institution of the state has to evolve in new directions if basic liberal and democratic values are to be institutionalized in that environment.

The nationalist Republican conservatives, on the other hand, want to strengthen the state. They are hemmed in by a patriotic and exceptionalist view of its role. Insofar as they are motivated by liberal impulses at all – and of course many parts of their political base are not – it is based on a conception of freedom situated entirely on national-level institutions. As such, it implies walling the world off or, worse, dominating the world as a pre-eminent nation-state. The rise of Trump and the ease with which he took over the Republican Party ought to be a signal to the real libertarians that the Republican Party is no longer viable as a lesser-of-two-evils home for true liberals. The base of the Republican Party, the coalition of constituencies and worldviews of which it is composed, is splitting into two camps with irreconcilable differences over fundamental issues. Good riddance to the nationalists, I say. This split poses a tremendous opportunity for libertarians to finally free themselves of the social conservatism, nationalistic militarists, nativists and theocrats that have dragged them down in the GOP.

July 29, 2016

Book Review: Calestous Juma’s “Innovation and Its Enemies”

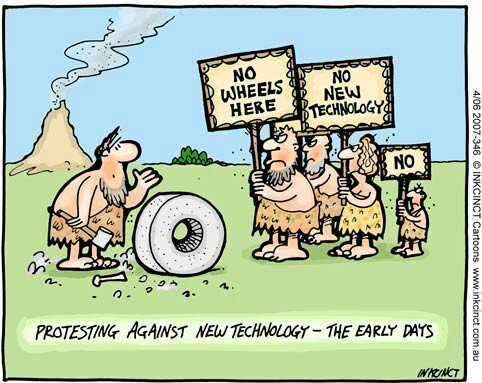

“The quickest way to find out who your enemies are is to try doing something new.” Thus begins Innovation and Its Enemies, an ambitious new book by Calestous Juma that will go down as one of the decade’s most important works on innovation policy.

Juma, who is affiliated with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, has written a book that is rich in history and insights about the social and economic forces and factors that have, again and again, lead various groups and individuals to oppose technological change. Juma’s extensive research documents how “technological controversies often arise from tensions between the need to innovate and the pressure to maintain continuity, social order, and stability” (p. 5) and how this tension is “one of today’s biggest policy challenges.” (p. 8)

What Juma does better than any other technology policy scholar to date is that he identifies how these tensions develop out of deep-seated psychological biases that eventually come to affect attitudes about innovations among individuals, groups, corporations, and governments. “Public perceptions about the benefits and risks of new technologies cannot be fully understood without paying attention to intuitive aspects of human psychology,” he correctly observes. (p. 24)

Opposition to Change: It’s All in Your Head

Juma documents, for example, how “status quo bias,” loss aversion, and other psychological tendencies tend to encourage resistance to technological change. [Note: I discussed these and other “root-cause” explanations of opposition to technological change in Chapter 2 of my book, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, as well as in my 2012 law review article on “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle.”] Juma notes, for example, that “society is most likely to oppose a new technology if it perceives that the risks are likely to occur in the short run and the benefits will only accrue in the long run.” (p. 5) Moreover, “much of the concern is driven by perception of loss, not necessarily by concrete evidence of loss.” (p. 11)

Juma’s approach to innovation policy studies is strongly influenced by the path-breaking work of Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, who long ago documented how entrepreneurial activity and the “perennial gales of creative destruction” were the prime forces that spurred innovation and propelled society forward. But Schumpeter was also one of the first scholars to realize that psychological fears about such turbulent change was what ultimately lead to much of the short-term opposition to new technologies that, in due time, we eventually come to see as life-enriching or even life-essential innovations. Juma uses Schumpeter’s insight as the launching point for his exploration and he successfully verifies it using meticulously-detailed case studies.

Case Study-Driven Analysis

Short-term opposition to change is particularly acute among incumbent industries and interest groups, who often feel they have the most to lose. In this regard, Innovation and Its Enemies contains some spectacular histories of how special interests have resisted new technologies and developments throughout the centuries. Those case studies include: coffee and coffeehouses, the printing press, margarine, farm machinery, electricity, mechanical refrigeration, recorded music, transgenic crops, and genetically engineered salmon. These case studies are remarkably detailed histories that offer engaging and enlightening accounts of “the tensions between innovation and incumbency.”

Short-term opposition to change is particularly acute among incumbent industries and interest groups, who often feel they have the most to lose. In this regard, Innovation and Its Enemies contains some spectacular histories of how special interests have resisted new technologies and developments throughout the centuries. Those case studies include: coffee and coffeehouses, the printing press, margarine, farm machinery, electricity, mechanical refrigeration, recorded music, transgenic crops, and genetically engineered salmon. These case studies are remarkably detailed histories that offer engaging and enlightening accounts of “the tensions between innovation and incumbency.”

My favorite case study in the book discusses how the dairy industry fought the creation and spread of margarine (excuse the pun!). I had no idea how ugly that situation got, but Juma provides all the gory details in what I consider one of the very best crony capitalist case studies ever penned.

In particular, in a subsection of that chapter entitled “The Laws against Margarine,” he provides a litany of examples of how effective the dairy industry was in convincing lawmakers to enact ridiculous anti-consumer regulations to stop margarine, even though the product offered the public a much-needed, and much more affordable, substitute for traditional butter. At one point, the daily industry successfully lobbied five states to adopt rules mandating that any imitation butter product had to be dyed pink! Other states enacted labelling laws that required butter substitutes to come in ominous-looking black packaging. Again, all this was done at the request of the incumbent dairy industry and the National Dairy Council, which would resort to almost any sort of deceptive tactic to keep a cheaper competing product out of the hands of consumers.

And so it goes in chapter after chapter of Juma’s book. The amount of detail in each of these unique case studies is absolutely stunning, but they nonetheless remain highly readable accounts of sectoral protectionism, special interest rent-seeking, and regulatory capture. In this way, Juma is plowing some familiar ground already covered by other economic historians and political scientists, such as Joel Mokyr and Mancur Olson, both of whom are mentioned in the book, as well as a long line of public choice scholars who are, somewhat surprisingly, not discussed in the text. Nonetheless, Juma’s approach is still fresh, unique, and highly informative. In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many distinct and highly detailed case studies assembled in one place by a single scholar. What Juma has done here is truly impressive.

Related Innovation Policy Paradigms

Beyond Schumpeter’s clear influence, Juma’s approach to studying innovation policy also shares a great deal in common with two other unmentioned innovation policy scholars, Virginia Postrel and Robert D. Atkinson.

Postrel’s 1998 book, The Future and Its Enemies, contrasted the conflicting worldviews of “dynamism” and “stasis” and showed how the tensions between these two visions would affect the course of human affairs. She made the case for embracing dynamism — “a world of constant creation, discovery, and competition” — over the “regulated, engineered world” of the stasis mentality. Similarly, in his 2004 book, The Past and Future of America’s Economy, Atkinson documented how “American history is rife with resistance to change,” and in recounting some of the heated battles over previous technological revolutions he showed how two camps were always evident: “preservationists” and “modernizers.”

When Juma repeatedly recounts the fight between “innovation and incumbency” in his case studies, he is essentially describing the same paradigmatic divide that Postrel and Atkinson highlight in their works when they discuss “dynamist” vs. “stasis” tensions and the “modernizers” vs. “preservationists” battles that we have seen throughout history. [Note: In my 2014 essay on, “Thinking about Innovation Policy Debates: 4 Related Paradigms,” I discussed Postrel and Atkinson’s books and other approaches to understanding tech policy divisions and then related them to the paradigms I contrast in my work: the so-called “precautionary principle” vs. “permissionless Innovation” mindsets.]

Finally, Juma’s book could also be compared to another freshly released book, The Politics of Innovation, by Mark Zachary Taylor. Taylor’s book is also essential reading on this lamentable history of industrial protectionism and the resulting political opposition to change we have seen over time. [Note: Brent Skorup and provided many other high-tech cronyist case studies like these in our 2013 law review article, “A History of Cronyism and Capture in the Information Technology Sector.”]

To counter the prevalence of special interest influence and poor policymaking more generally, Juma stresses the need for evidence-based analysis and a corresponding rejection of fear-mongering and deceptive tactics by public officials and activist groups. He’s particularly concerned with “the use of demonization and false analogies to amplify the perception of risks associated with a new product.”

Accordingly, he would like to see improved educational and risk communication efforts aimed at better informing the public about risk trade-offs and the many potential future benefits of emerging technologies. “Learning how to communicate to the general public is an important aspect of reducing distrust [in new technologies],” Juma argues. (p. 312)

On the Pacing Problem

But Juma never really adequately squares that recommendation with another point he makes throughout the text about how “the pace of technological innovation is discernibly fast,” (p. 5) and how it is accelerating in an exponential fashion. “The implications of exponential growth will continue to elude political leaders if they persist in operating with linear worldviews.” (p. 14) But if it is indeed the case that things are moving that fast, then are we not potentially doomed to live in never-ending cycles of technopanics and misinformation campaigns about new technologies no matter how much education we try to do?

Regardless, Juma’s argument about the speed of modern technological change is quite valid and shared by many other scholars. He is essentially making the same case that Larry Downes did in his excellent 2009 book, The Laws of Disruption: Harnessing the New Forces That Govern Life and Business in the Digital Age. Downes argued that lawmaking in the information age is inexorably governed by the “law of disruption” or the fact that “technology changes exponentially, but social, economic, and legal systems change incrementally.” This law, Downes said, is “a simple but unavoidable principle of modern life,” and it will have profound implications for the way businesses, government, and culture evolve going forward. “As the gap between the old world and the new gets wider,” he argued, “conflicts between social, economic, political, and legal systems” will intensify and “nothing can stop the chaos that will follow.”

Again, Juma makes that same point repeatedly throughout the chapters of his book. This is also a restatement of the so-called “pacing problem,” as it is called in the field of the philosophy of technology. I discussed the pacing problem at length in my recent review of Wendell Wallach’s important new book, A Dangerous Master: How to Keep Technology from Slipping beyond Our Control. Wallach nicely defined the pacing problem as “the gap between the introduction of a new technology and the establishment of laws, regulations, and oversight mechanisms for shaping its safe development.” “There has always been a pacing problem,” he noted but, like Juma, Wallach believes that modern technological innovation is occurring at an unprecedented pace, making it harder than ever to “govern” using traditional legal and regulatory mechanisms.

New Approaches to Technological Governance Needed

Both Wallach in A Dangerous Master and Juma in Innovation and Its Enemies struggle with how to solve this problem. Wallach advocates “soft law” mechanisms or even informal “Governance Coordinating Committees,” which would oversee the development of new technology policies and advise existing governmental institutions. Juma is somewhat ambiguous regarding potential solutions, but he does stress the general need for a flexible approach to policy, as he notes on pg. 252: