Adam Thierer's Blog, page 43

June 2, 2014

Son’s Criticism of U.S. Broadband Misleading and Misplaced

Chairman and CEO Masayoshi Son of SoftBank again criticized U.S. broadband (see this and this) at last week’s Code Conference.

The U.S. created the Internet, but its speeds rank 15th out of 16 major countries, ahead of only the Philippines. Mexico is No. 17, by the way.

It turns out that Son couldn’t have been referring to the broadband service he receives from Comcast, since the survey data he was citing—as he has in the past—appears to be from OpenSignal and was gleaned from a subset of the six million users of the OpenSignal app who had 4G LTE wireless access in the second half of 2013.

Oh, and Son neglected to mention that immediately ahead of the U.S. in the OpenSignal survey is Japan.

Son, who is also the chairman of Sprint, has a legitimate grievance with overzealous U.S. antitrust enforcers. But he should be aware that for many years the proponents of network neutrality regulation have cited international rankings in support of their contention that the U.S. broadband market is under-regulated.

It is a well-established fact that measuring broadband speeds and prices from one country to the next is difficult as a result of “significant gaps and variations in data collection methodologies,” and that “numerous market, regulatory, and geographic factors determine penetration rates, prices, and speeds.” See, e.g., the Federal Communications Commission’s most recent International Broadband Data Report. In the case of wireless services, as one example, the availability of sufficient airwaves can have a huge impact on speeds and prices. Airwaves are assigned by the FCC.

There are some bright spots in the broadband comparisons published by a number of organizations.

For example, U.S. consumers pay the third lowest average price for entry-level fixed broadband of 161 countries surveyed by ITU (the International Telecommunications Union).

And as David Balto notes over at Huffington Post, Akamai reports that the average connection speeds in Japan and the U.S. aren’t very far apart—12.8 megabits per second in Japan versus 10 Mbps in the U.S.

Actual speeds experienced by broadband users reflect the service tiers consumers choose to purchase, and not everyone elects to pay for the highest available speed. It’s unfair to blame service providers for that.

A more relevant metric for judging service providers is investment. ITU reports that the U.S. leads every other nation in telecommunications investment by far. U.S. service providers invested more than $70 billion in 2010 versus less than $17 billion in Japan. On a per capita basis, telecom investment in the U.S. is almost twice that of Japan.

In Europe, per capita investment in telecommunications infrastructure is less than half what it is in the U.S., according to Martin Thelle and Bruno Basalisco.

Incidentally, the European Commission has concluded,

Networks are too slow, unreliable and insecure for most Europeans; Telecoms companies often have huge debts, making it hard to invest in improvements. We need to turn the sector around so that it enables more productivity, jobs and growth.

It should be noted that for the past decade or so Europe has been pursuing the same regulatory strategy that net neutrality boosters are advocating for the U.S. Thelle and Basalisco observe that,

The problem with the European unbundling regulation is that it pitted short-term consumer benefits, such as low prices, against the long-run benefits from capital investment and innovation. Unfortunately, regulators often sacrificed the long-term interest by forcing an infrastructure owner to share its physical wires with competing operators at a cheap rate. Thus, the regulated company never had a strong incentive to invest in new infrastructure technologies — a move that would considerably benefit the competing operators using its infrastructure.

Europe’s experience with the unintended consequences of unnecessary regulation is perhaps the most useful lesson the U.S. can learn from abroad.

May 30, 2014

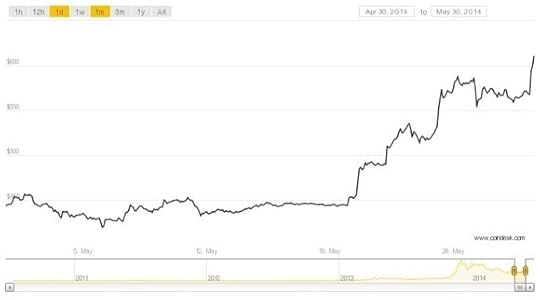

Mark T. Williams predicted Bitcoin’s price would be under $10 by now; it’s over $600

In April I had the opportunity to testify before the House Small Business Committee on the costs and benefits of small business use of Bitcoin. It was a lively hearing, especially thanks to fellow witness Mark T. Williams, a professor of finance at Boston University. To say he was skeptical of Bitcoin would be an understatement.

Whenever people make the case that Bitcoin will inevitably collapse, I ask them to define collapse and name a date by which it will happen. I sometimes even offer to make a bet. As Alex Tabarrok has explained, bets are a tax on bullshit.

So one thing I really appreciate about Prof. Williams is that unlike any other critic, he has been willing to make a clear prediction about how soon he thought Bitcoin would implode. On December 10, he told Tim Lee in an interview that he expected Bitcoin’s price to fall to under $10 in the first half of 2014. A week later, on December 17, he clearly reiterated his prediction in an op-ed for Business Insider:

I predict that Bitcoin will trade for under $10 a share by the first half of 2014, single digit pricing reflecting its option value as a pure commodity play.

Well, you know where this is going. We’re now five months into the year. How is Bitcoin doing?

It’s in the middle of a rally, with the price crossing $600 for the first time in a couple of months. Yesterday Dish Networks announced it would begin accepting Bitcoin payments from customers, making it the largest company yet to do so.

None of this is to say that Bitcoin’s future is assured. It is a new and still experimental technology. But I think we can put to bed the idea that it will implode in the short term because it’s not like any currency or exchange system that came before, which was essentially William’s argument.

May 23, 2014

The Problem with “Pessimism Porn”

I’ve spent a lot of time here through the years trying to identify the factors that fuel moral panics and “technopanics.” (Here’s a compendium of the dozens of essays I’ve written here on this topic.) I brought all this thinking together in a big law review article (“Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle”) and then also in my new booklet, “Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom.”

One factor I identify as contributing to panics is the fact that “bad news sells.” As I noted in the book, “Many media outlets and sensationalist authors sometimes use fear-based tactics to gain influence or sell books. Fear mongering and prophecies of doom are always effective media tactics; alarmism helps break through all the noise and get heard.”

In line with that, I want to highly recommend you check out this excellent new oped by John Stossel of Fox Business Network on “Good News vs. ‘Pessimism Porn‘.” Stossel correctly notes that “the media win by selling pessimism porn.” He says:

Are you worried about the future? It’s hard not to be. If you watch the news, you mostly see violence, disasters, danger. Some in my business call it “fear porn” or “pessimism porn.” People like the stuff; it makes them feel alive and informed.

Of course, it’s our job to tell you about problems. If a plane crashes — or disappears — that’s news. The fact that millions of planes arrive safely is a miracle, but it’s not news. So we soak in disasters — and warnings about the next one: bird flu, global warming, potential terrorism. I won Emmys hyping risks but stopped winning them when I wised up and started reporting on the overhyping of risks. My colleagues didn’t like that as much.

He continues on to note how, even though all the data clearly proves that humanity’s lot is improving, the press relentlessly push the “pessimism porn.” He argues that “time and again, humanity survived doomsday. Not just survived, we flourish.” But that doesn’t stop the doomsayers from predicting that the sky is always set to fall. In particular, the press knows they can easily gin up more readers and viewers by amping up the fear-mongering and featuring loonies who will be all too happy to play the roles of pessimism porn stars. Of course, plenty of academics, activists, non-profit organizations and even companies are all too eager to contribute to this gloom-and-doom game since they benefit from the exposure or money it generates.

The problem with all this, of course, is that it perpetuates societal fears and distrust. It also sometimes leads to misguided policies based on hypothetical worst-case thinking. As I argue in my new book, which Stossel was kind enough to cite in his essay, if we spend all our time living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy upon them—it means that best-case scenarios will never come about.

Facts, not fear, should guide our thinking about the future.

______________________

Related Reading:

Journalists, Technopanics & the Risk Response Continuum (July 15, 2012)

How & Why the Press Sometimes “Sells Digital Fear” (April 8, 2012)

danah boyd’s “Culture of Fear” Talk (March 26, 2012)

Prophecies of Doom & the Politics of Fear in Cybersecurity Debates (Aug. 8., 2011)

Cybersecurity Threat Inflation Watch: Blood-Sucking Weapons! (March 22, 2012)

May 22, 2014

The Anticompetitive Effects of Broadcast Television Regulations

Shortly after Tom Wheeler assumed the Chairmanship at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), he summed up his regulatory philosophy as “competition, competition, competition.” Promoting competition has been the norm in communications policy since Congress adopted the Telecommunications Act of 1996 in order to “promote competition and reduce regulation.” The 1996 Act has largely succeeded in achieving competition in communications markets with one glaring exception: broadcast television. In stark contrast to the pro-competitive approach that is applied in other market segments, Congress and the FCC have consistently supported policies that artificially limit the ability of TV stations to compete or innovate in the communications marketplace.

Radio broadcasting was not subject to regulatory oversight initially. In the unregulated era, the business model for over-the-air broadcasting was “still very much an open question.” Various methods for financing radio stations were proposed or attempted, including taxes on the sale of devices, private endowments, municipal or state financing, public donations, and subscriptions. “We are today so accustomed to the dominant role of the advertiser in broadcasting that we tend to forget that, initially, the idea of advertising on the air was not even contemplated and met with widespread indignation when it was first tried.”

Section 303 of the Communications Act of 1934 thus provided the FCC with broad authority to authorize over-the-air subscription television service (STV). When the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals addressed this provision, it held that “subscription television is entirely consistent with [the] goals” of the Act. Analog STV services did not become widespread in the marketplace, however, due in part to regulatory limitations imposed on such services by the FCC. As a result, advertising dominated television revenue in the analog era.

The digital television (DTV) transition offered a new opportunity for TV stations to provide STV services in competition with MVPDs. The FCC had initially hoped that “multicasting” and other new capabilities provided by digital technologies would “help ensure robust competition in the video market that will bring more choices at less cost to American consumers.”

Despite the agency’s initial optimism, regulatory restrictions once again crushed the potential for TV stations to compete in other segments of the communications marketplace. When broadcasters proposed offering digital STV services with multiple broadcast and cable channels in order to compete with MVPDs, Congress held a hearing to condemn the innovation. Chairmen from both House and Senate committees threatened retribution against broadcasters if they pursued subscription television services — “There will be a quid pro quo.” Broadcasters responded to these Congressional threats by abandoning their plans to compete with MVPDs.

It’s hard to miss the irony in the 1996 Act’s approach to the DTV transition. Though the Act’s stated purposes are to “promote competition and reduce regulation, it imposed additional regulatory requirements on television stations that have stymied their ability to innovate and compete. The 1996 Act broadcasting provision requires that the FCC impose limits on subscription television services “so as to avoid derogation of any advanced television services, including high definition television broadcasts, that the Commission may require using such frequencies,” and prohibits TV stations from being deemed an MVPD. The FCC’s rules require TV stations to “transmit at least one over-the-air video programming signal at no direct charge to viewers” because “free, over-the-air television is a public good, like a public park, and might not exist otherwise.

These and other draconian legislative and regulatory limitations have forced TV stations to follow the analog television business model into the 21st Century while the rest of the communications industry innovated at a furious pace. As a result of this government-mandated broadcast business model, TV stations must rely on advertising and retransmission consent revenue for their survival.

Though the “public interest” status of TV stations may once have been considered a government benefit, it is rapidly becoming a curse. Congress and the FCC have both relied on the broadcast public interest shibboleth to impose unique and highly burdensome regulatory obligations on TV stations that are inapplicable to their competitors in the advertising and other potential markets. This disparity in regulatory treatment has increased dramatically under the current administration — to the point that is threatening the viability of broadcast television.

Here are just three examples of the ways in which the current administration has widened the regulatory chasm between TV stations and their rivals:

In 2012, the FCC required only TV stations to post “political file” documents online, including the rates charged by TV stations for political advertising; MVPDs are not required to post this information online. This regulatory disparity gives political ad buyers and incentive to advertise on cable rather than broadcast channels and forces TV stations to disclose sensitive pricing information more widely than their competitors.

This year the FCC prohibited joint sales agreements for television stations only; MVPDs and online content distributors are not subject to any such limitations on their advertising sales. This prohibition gives MVPDs and online advertising platforms a substantial competitive advantage in the market for advertising sales.

This year the FCC also prohibited bundled programming sales by broadcasters only; cable networks are not subject to any limitations on the sale of programming in bundles. This disparity gives broadcast networks an incentive to avoid limitations on their programming sales by selling exclusively to MVPDs (i.e., becoming cable networks).

The FCC has not made any attempt to justify the differential treatment — because there is no rational justification for arbitrary and capricious decision-making.

Sadly, the STELA process in the Senate is threatening to make things worse. Some legislative proposals would eliminate retransmission consent and other provisions that provide the regulatory ballast for broadcast television’s government mandated business model without eliminating the mandate. This approach would put a quick end to the administration’s “death by a thousand cuts” strategy with one killing blow. The administration must be laughing itself silly. When TV channels in smaller and rural markets go dark, this administration will be gone — and it will be up to Congress to explain the final TV transition.

May 19, 2014

Network Non-Duplication and Syndicated Exclusivity Rules Are Fundamental to Local Television

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) recently sought additional comment on whether it should eliminate its network non-duplication and syndicated exclusivity rules (known as the “broadcasting exclusivity” rules). It should just as well have asked whether it should eliminate its rules governing broadcast television. Local TV stations could not survive without broadcast exclusivity rights that are enforceable both legally and practicably.

The FCC’s broadcast exclusivity rules “do not create rights but rather provide a means for the parties to exclusive contracts to enforce them through the Commission rather than the courts.” (Broadcast Exclusivity Order, FCC 88-180 at ¶ 120 (1988)) The rights themselves are created through private contracts between TV stations and video programming vendors in the same manner that MVPDs create exclusive rights to distribute cable network programming.

Local TV stations typically negotiate contracts for the exclusive distribution of national broadcast network or syndicated programming in their respective local markets in order to preserve their ability to obtain local advertising revenue. The FCC has long recognized that, “When the same program a [local] broadcaster is showing is available via cable transmission of a duplicative [distant] signal, the [local] broadcaster will attract a smaller audience, reducing the amount of advertising revenue it can garner.” (Program Access Order, FCC 12-123 at ¶ 62 (2012)) Enforceable broadcast exclusivity agreements are thus necessary for local TV stations to generate the advertising revenue that is necessary for them to survive the government’s mandatory broadcast television business model.

The FCC determined nearly fifty years ago that it is an anticompetitive practice for multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) to import distant broadcast signals into local markets that duplicate network and syndicated programming to which local stations have purchased exclusive rights. (See First Exclusivity Order, 38 FCC 683, 703-704 (1965)) Though the video marketplace has changed since 1965, the government’s mandatory broadcast business model is still required by law, and MVPD violations of broadcast exclusivity rights are still anticompetitive.

The FCC adopted broadcast exclusivity procedures to ensure that broadcasters, who are legally prohibited from obtaining direct contractual relationships with viewers or economies of scale, could enjoy the same ability to enforce exclusive programming rights as larger MVPDs. The FCC’s rules are thus designed to “allow all participants in the marketplace to determine, based on their own best business judgment, what degree of programming exclusivity will best allow them to compete in the marketplace and most effectively serve their viewers.” (Broadcast Exclusivity Order at ¶ 125.)

When it adopted the current broadcast exclusivity rules, the FCC concluded that enforcement of broadcast exclusivity agreements was necessary to counteract regulatory restrictions that prevent TV stations from competing directly with MVPDs. Broadcasters suffer the diversion of viewers to duplicative programming on MVPD systems when local TV stations choose to exhibit the most popular programming, because that programming is the most likely to be duplicated. (See Broadcast Exclusivity Order at ¶ 62.) Normally firms suffer their most severe losses when they fail to meet consumer demand, but, in the absence of enforceable broadcast exclusivity agreements, this relationship is reversed for local TV stations: they suffer their most severe losses precisely when they offer the programming that consumers desire most.

The fact that only broadcasters suffer this kind of [viewership] diversion is stark evidence, not of inferior ability to be responsive to viewers’ preferences, but rather of the fact that broadcasters operate under a different set of competitive rules. All programmers face competition from alternative sources of programming. Only broadcasters face, and are powerless to prevent, competition from the programming they themselves offer to viewers. (Id. at ¶ 42.)

The FCC has thus concluded that, if TV stations were unable to enforce exclusive contracts through FCC rules, TV stations would be competitively handicapped compared to MVPDs. (See id. at ¶ 162.)

Regulatory restrictions effectively prevent local TV stations from enforcing broadcast exclusivity agreements through preventative measures and in the courts: (1) prohibitions on subscription television and the use of digital rights management (DRM) prevent broadcasters from protecting their programming from unauthorized retransmission, and (2) stringent ownership limits prevent them from obtaining economies of scale.

Preventative measures may be the most cost effective way to protect digital content rights. Most digital content is distributed with some form of DRM because, as Benjamin Franklin famously said, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” MVPDs, online video distributors, and innumerable Internet companies all use DRM to protect their digital content and services — e.g., cable operators use the CableCard standard to limit distribution of cable programming to their subscribers only.

TV stations are the only video distributors that are legally prohibited from using DRM to control retransmission of their primary programming. The FCC adopted a form of DRM for digital television in 2003 known as the “broadcast flag”, but the DC Circuit Court of Appeals struck it down.

The requirement that TV stations offer their programming “at no direct charge to viewers” effectively prevents them from having direct relationships with end users. TV stations cannot require those who receive their programming over-the-air to agree to any particular terms of service or retransmission limitations through private contract. As a result, TV stations have no way to avail themselves of the types of contractual protections enjoyed by MVPDs who offer services on a subscription basis.

The subscription television and DRM prohibitions have a significant adverse impact on the ability of TV stations to control the retransmission and use of their programming. The Aereo litigation provides a timely example. If TV stations offered their programming on a subscription basis using the CableCard standard, the Aereo “business” model would not exist and the courts would not be tying themselves into knots over potentially conflicting interpretations of the Copyright Act. Because they are legally prohibited from using DRM to prevent companies like Aereo from receiving and retransmitting their programming in the first instance, however, TV stations are forced to rely solely on after-the-fact enforcement to protect their programming rights — i.e., protected and uncertain litigation in multiple jurisdictions.

Localism policies make after-the-fact enforcement particularly cost for local TV stations. The stringent ownership limits that prevent TV stations from obtaining economies of scale have the effect of subjecting TV stations to higher enforcement costs relative to other digital rights holders. In the absence of FCC rules enforcing broadcast exclusivity agreements, family owned TV stations could be forced to defend their rights in court against significantly larger companies who have the incentive and ability to use litigation strategically.

In sum, the FCC’s non-duplication and syndication rules balance broadcast regulatory limitations by providing clear mechanisms for TV stations to communicate their contractual rights to MVPDs, with whom they have no direct relationship, and enforce those rights at the FCC (which is a strong deterrent to the potential for strategic litigation). There is nothing unfair or over-regulatory about FCC enforcement in these circumstances. So why is the FCC asking whether it should eliminate the rules?

May 16, 2014

IP Transition Luncheon Briefing on Monday, May 19

Telephone companies have already begun transitioning their networks to Internet Protocol. This could save billions while improving service for consumers and promoting faster broadband, but has raised a host of policy and legal questions. How can we ensure the switch is as smooth and successful as possible? What legal authority do the FCC and other agencies have over the IP Transition and how should they use it?

Join TechFreedom on Monday, May 19, at its Capitol Hill office for a lunch event to discuss this and more with top experts from the field. Two short technical presentations will set the stage for a panel of legal and policy experts, including:

Jodie Griffin, Senior Staff Attorney, Public Knowledge

Hank Hultquist, VP of Federal Regulatory, AT&T

Berin Szoka, President, TechFreedom

Christopher Yoo, Professor, University of Pennsylvania School of Law

David Young, VP of Federal Regulatory Affairs, Verizon

The panel will be livestreamed (available here). Join the conversation on Twitter with the #IPTransition hashtag.

When:

Monday, May 19, 2014

11:30am – 12:00pm — Lunch and registration

12:00pm – 12:20pm — Technical presentations by AT&T and Verizon

12:20pm – 2:00 pm — Panel on legal and policy issues, audience Q&A

Where:

United Methodist Building, Rooms 1 & 2

100 Maryland Avenue NE

Washington, DC 20002

Questions?

Email mail@techfreedom.org.

May 15, 2014

Why Reclassification Would Make the Internet Less Open

There seems to be increasing chatter among net neutrality activists lately on the subject of reclassifying ISPs as Title II services, subject to common carriage regulation. Although the intent in pushing reclassification is to make the Internet more open and free, in reality such a move could backfire badly. Activists don’t seem to have considered the effect of reclassification on international Internet politics, where it would likely give enemies of Internet openness everything they have always wanted.

At the WCIT in 2012, one of the major issues up for debate was whether the revised International Telecommunication Regulations (ITRs) would apply to Operating Agencies (OAs) or to Recognized Operating Agencies (ROAs). OA is a very broad term that covers private network operators, leased line networks, and even ham radio operators. Since “OA” would have included IP service providers, the US and other more liberal countries were very much opposed to the application of the ITRs to OAs. ROAs, on the other hand, are OAs that operate “public correspondence or broadcasting service.” That first term, “public correspondence,” is a term of art that means basically common carriage. The US government was OK with the use of ROA in the treaty because it would have essentially cabined the regulations to international telephone service, leaving the Internet free from UN interference. What actually happened was that there was a failed compromise in which ITU Member States created a new term, Authorized Operating Agency, that was arguably somewhere in the middle—the definition included the word “public” but not “public correspondence”—and the US and other countries refused to sign the treaty out of concern that it was still too broad.

If the US reclassified ISPs as Title II services, that would arguably make them ROAs for purposes at the ITU (arguably because it depends on how you read the definition of ROA and Article 6 of the ITU Constitution). This potentially opens ISPs up to regulation under the ITRs. This might not be so bad if the US were the only country in the world—after all, the US did not sign the 2012 ITRs, and it does not use the ITU’s accounting rate provisions to govern international telecom payments.

But what happens when other countries start copying the US, imposing common carriage requirements, and classifying their ISPs as ROAs? Then the story gets much worse. Countries that are signatories to the 2012 ITRs would have ITU mandates on security and spam imposed on their networks, which is to say that the UN would start essentially regulating content on the Internet. This is what Russia, Saudia Arabia, and China have always wanted. Furthermore (and perhaps more frighteningly), classification as ROAs would allow foreign ISPs to forgo commercial peering arrangements in favor of the ITU’s accounting rate system. This is what a number of African governments have always wanted. Ethiopia, for example, considered a bill (I’m not 100 percent sure it ever passed) that would send its own citizens to jail for 15 years for using VOIP, because this decreases Ethiopian international telecom revenues. Having the option of using the ITU accounting rate system would make it easier to extract revenues from international Internet use.

Whatever you think of, e.g., Comcast and Cogent’s peering dispute, applying ITU regulation to ISPs would be significantly worse in terms of keeping the Internet open. By reclassifying US ISPs as common carriers, we would open the door to exactly that. The US government has never objected to ITU regulation of ROAs, so if we ever create a norm under which ISPs are arguably ROAs, we would be essentially undoing all of the progress that we made at the WCIT in standing up for a distinction between old-school telecom and the Internet. I imagine that some net neutrality advocates will find this unfair—after all, their goal is openness, not ITU control over IP service. But this is the reality of international politics: the US would have a very hard time at the ITU arguing that regulating for neutrality and common carriage is OK, but regulating for security, content, and payment is not.

If the goal is to keep the Internet open, we must look somewhere besides Title II.

May 13, 2014

Adam Thierer on Permissionless Innovation

Adam Thierer, senior research fellow with the Technology Policy Program at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, discusses his latest book Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom. Thierer discusses which types of policies promote technological discoveries as well as those that stifle the freedom to innovate. He also takes a look at new technologies — such as driverless cars, drones, big data, smartphone apps, and Google Glass — and how the American public will adapt to them.

Related Links

Biography, Thierer

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, Thierer

Video: Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Technological Freedom, Thierer

May 12, 2014

In Defense of Broadband Fast Lanes

The outrage over the FCC’s attempt to write new open Internet rules has caught many by surprise, and probably Chairman Wheeler as well. The rumored possibility of the FCC authorizing broadband “fast lanes” draws most complaints and animus. Gus Hurwitz points out that the FCC’s actions this week have nothing to do with fast lanes and Larry Downes reminds us that this week’s rules don’t authorize anything. There’s a tremendous amount of misinformation because few understand how administrative law works. Yet many net neutrality proponents fear the worst from the proposed rules because Wheeler takes the consensus position that broadband provision is a two-sided market and prioritized traffic could be pro-consumer.

Fast lanes have been permitted by the FCC for years and they can benefit consumers. Some broadband services–like video and voice over Internet protocol (VoIP)–need to be transmitted faster or with better quality than static webpages, email, and file syncs. Don’t take my word for it. The 2010 Open Internet NPRM, which led to the recently struck-down rules, stated,

As rapid innovation in Internet-related services continues, we recognize that there are and will continue to be Internet-Protocol-based offerings (including voice and subscription video services, and certain business services provided to enterprise customers), often provided over the same networks used for broadband Internet access service, that have not been classified by the Commission. We use the term “managed” or “specialized” services to describe these types of offerings. The existence of these services may provide consumer benefits, including greater competition among voice and subscription video providers, and may lead to increased deployment of broadband networks.

I have no special knowledge about what ISPs will or won’t do. I wouldn’t predict in the short term the widespread development of prioritized traffic under even minimal regulation. I think the carriers haven’t looked too closely at additional services because net neutrality regulations have precariously hung over them for a decade. But some of net neutrality proponents’ talking points (like insinuating or predicting ISPs will block political speech they disagree with) are not based in reality.

We run a serious risk of derailing research and development into broadband services if the FCC is cowed by uninformed and extreme net neutrality views. As Adam eloquently said, “Living in constant fear of hypothetical worst-case scenarios — and premising public policy upon them — means that best-case scenarios will never come about.” Many net neutrality proponents would like to smear all priority traffic as unjust and exploitative. This is unfortunate and a bit ironic because one of the most transformative communications developments, cable VoIP, is a prioritized IP service.

There are other IP services that are only economically feasible if jitter, latency, and slow speed are minimized. Prioritized traffic takes several forms, but it could enhance these services:

VoIP. This prioritized service has actually been around for several years and has completely revolutionized the phone industry. Something unthinkable for decades–facilities-based local telephone service–became commonplace in the last few years and undermined much of the careful industrial planning in the 1996 Telecom Act. If you subscribe to voice service from your cable provider, you are benefiting from fast lane treatment. Your “phone” service is carried over your broadband cable, segregated from your television and Internet streams. Smaller ISPs could conceivably make their phone service more attractive by pairing up with a Skype- or Vonage-type voice provider, and there are other possibilities that make local phone service more competitive.

Cloud-hosted virtual desktops. This is not a new idea, but it’s possible to have most or all of your computing done in a secure cloud, not on your PC, via a prioritized data stream. With a virtual desktop, your laptop or desktop PC functions mainly as a dumb portal. No more annoying software updates. Fewer security risks. IT and security departments everywhere would rejoice. Google Chromebooks are a stripped-down version of this but truly functional virtual desktops would be valued by corporations, reporters, or government agencies that don’t want sensitive data saved on a bunch of laptops in their organization that they can’t constantly monitor. Virtual desktops could also transform the device market, putting the focus on a great cloud and (priority) broadband service and less on the power and speed of the device. Unfortunately, at present, virtual desktops are not in widespread use because even small lag frustrates users.

TV. The future of TV is IP-based and the distinction between “TV” and “the Internet” is increasingly blurring, with Netflix leading the way. In a fast lane future, you could imagine ISPs launching pared-down TV bundles–say, Netflix, HBO Go, and some sports channels–over a broadband connection. Most ISPs wouldn’t do it, but an over-the-top package might interest smaller ISPs who find acquiring TV content and bundling their own cable packages time-consuming and expensive.

Gaming. Computer gamers hate jitter and latency. (My experience with a roommate who had unprintable outbursts when Diablo III or World of Warcraft lagged is not uncommon.) Game lag means you die quite frequently because of your data connection and this depresses your interest in a game. There might be gaming companies out there who would like to partner with ISPs and other network operators to ensure smooth gameplay. Priority gaming services could also lead the way to more realistic, beautiful, and graphics-intensive games.

Teleconferencing, telemedicine, teleteaching, etc. Any real-time, video-based service could reach critical mass of subscribers and become economical with priority treatment. Any lag absolutely kills consumer interest in these video-based applications. By favoring applications like telemedicine, providing remote services could become attractive to enough people for ISPS to offer stand-alone broadband products.

This is just a sampling of the possible consumer benefits of pay-for-priority IP services we possibly sacrifice in the name of strict neutrality enforcement. There are other services we can’t even conceive of yet that will never develop. Generally, net neutrality proponents don’t admit these possible benefits and are trying to poison the well against all priority deals, including many of these services.

Most troubling, net neutrality turns the regulatory process on its head. Rather than identify a market failure and then take steps to correct the failure, the FCC may prevent commercial agreements that would be unobjectionable in nearly any other industry. The FCC has many experts who are familiar with the possible benefits of broadband fast lanes, which is why the FCC has consistently blessed priority treatment in some circumstances.

Unfortunately, the orchestrated reaction in recent weeks might leave us with onerous rules, delaying or making impossible new broadband services. Hopefully, in the ensuing months, reason wins out and FCC staff are persuaded by competitive analysis and possible innovations, not t-shirt slogans.

Technology Policy: A Look Ahead

This article was written by Adam Thierer, Jerry Brito, and Eli Dourado.

For the three of us, like most others in the field today, covering “technology policy” in Washington has traditionally been synonymous with covering communications and information technology issues, even though “tech policy” has actually always included policy relevant to a much wider array of goods, services, professions, and industries.

That’s changing, however. Day by day, the world of “technology policy” is evolving and expanding to incorporate much, much more. The same forces that have powered the information age revolution are now transforming countless other fields and laying waste to older sectors, technologies, and business models in the process. As Marc Andreessen noted in a widely-read 2011 essay, “Why Software Is Eating The World”:

More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.

Why is this happening now? Six decades into the computer revolution, four decades since the invention of the microprocessor, and two decades into the rise of the modern Internet, all of the technology required to transform industries through software finally works and can be widely delivered at global scale.

More specifically, many of the underlying drivers of the digital revolution—massive increases in processing power, exploding storage capacity, steady miniaturization of computing, ubiquitous communications and networking capabilities, the digitization of all data, and increasing decentralization and disintermediation—are beginning to have a profound impact beyond the confines of cyberspace.

The pace of this disruptive change is only going to accelerate and come to touch more and more industries. As it does, the public policy battles will also evolve and expand, and so, too, will our understanding of what “tech policy” includes.

That’s why the Mercatus Center Technology Policy Program continues to expand its issue coverage to include more scholarship on a wide array of emerging technologies and sectors. What we’re finding is that everything old is new again. The very same policy debates over privacy, safety, security, and IP that have dominated information policy are expanding to new frontiers. For example, when we started our program five years ago, we never thought we would be filing public interest comments on privacy issues with the Federal Aviation Administration, but that’s where we found ourselves last year as we advocated for permissionless innovation in the emerging domestic drone space. We now expect that we will soon find ourselves making a similar case at the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Transportation, and many other regulatory bodies in the near future.

In many ways, we’re still just talking about information policy, it’s just that increasing number of devices and sensors are being connected to the Internet. In other ways, however, it is in fact about more than simply an expanded conception of information policy. It’s about bringing the benefits of a permissionless innovation paradigm, which has worked so well in the Internet space, to sectors now controlled by prescriptive and precautionary regulation. As software continues to eat the world, innovation is increasingly butting up against outmoded and protectionist barriers to entry. Most will agree that the Internet has been the success it is because to launch a new product or service, you don’t have to ask anyone’s permission; we only need contract and tort law, and smart guard rails like safe harbors, to protect our rights. Yet if you want to offer a software-driven car service, you have to get permission from government first. If you want to offer genome sequencing and interpretation, you have to get permission first.

Maybe it’s time for a change. As Wall Street Journal columnist L. Gordon Crovitz argues, “The regulation the digital economy needs most now is for permissionless innovation to become the default law of the land, not the exception.” As a result, we’ll see this debate between “permissionless innovation” and the “precautionary principle” play out for a wide variety of new innovations such as the so-called “Internet of Things” and “wearable technologies,” but also with smart car technology, commercial drones, robotics, 3D printing, and many other new devices and services that are just now emerging. A recent New York Times survey, “A Vision of the Future From Those Likely to Invent It,” highlights additional innovation opportunities where this tension will exist.

The evolution of our work is also driven by the accelerating trend of decentralization and disintermediation, which could potentially make precautionary regulation too costly to undertake. When governments want to control information, they invariably head for the choke points, like payment processors or ISP-run DNS servers. This fact has created a demand for technologies that bypass such intermediaries. As mediated systems are increasingly replaced by decentralized peer-to-peer alternatives, there will be fewer points for control for governments to leverage. The result may be that any enforcement may have to target end users directly, which would not only increases the direct costs of enforcement, but also the political ones.

So in the coming months, you can expect to see Mercatus produce research on the economics of intellectual property, broadband investment, and spectrum policy, but also research on autonomous vehicles, wearable technologies, cryptocurrencies, and barriers to medical innovation. The future is looking brighter than ever, and we are excited to make permissionless innovation the default in that future.

Further Reading:

Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2014).

Adam Thierer, Why Permissionless Innovation Matters, Medium, April 24, 2014.

Eli Dourado, ‘Permissionless Innovation’ Offline as Well as On," The Umlaut, February 6, 2013.

Jerry Brito, Escape from Political Control, Reason, January 13, 2014

Jerry Brito, Regulating Drones Is as Bad an Idea as Regulating 3D Printing, The Umlaut, May 2, 2013

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower