Beth Kephart's Blog, page 31

December 18, 2015

She's not a sellout, is all: Martine Leavitt and Calvin

It was Tim Wynne-Jones who suggested. At Bank Street. While we were waiting for our panel on narrative risk.

It was Tim Wynne-Jones who suggested. At Bank Street. While we were waiting for our panel on narrative risk.Martine Leavitt is one of our smartest writers, period.

Martine Leavitt is a writer of great integrity.

Martine Leavitt spends her time making books (and teaching the artistry of making books, in the Vermont College of Fine Arts program, alongside Tim), as opposed to self-promoting.

Read Martine.

(Tim said. Rita Williams-Garcia nodded.)

And so I did. Picked up her newest, Calvin. Sat down. Utter immersion ensued.

Calvin, a seventeen-year-old smart kid who has been diagnosed with schizophrenia, was born the day the very final Calvin and Hobbes comic strip was published. As a baby, he had a stuffed tiger at his side. As a young man with a best friend named Susie, he has a lot of questions. He has hope, too—delusional hope?—that Bill Watterson, the comics' creator, will create one final cartoon strip that will set Calvin free of his persistent unrealities.

Are they unrealities?

All of which (but naturally, right?) sets Calvin off across the frozen tundra of Lake Erie in pursuit of Mr. Watterson. But oh, Lake Erie is very cold and very wide. And Susie may or may not be accompanying Calvin on this trek.

It feels like just a touch of sin to reduce this elegant novel to a summary. Because yes, this is a moving and original premise. But it's what happens inside Calvin's mind that matters most. The kid asks huge questions. He ponders without restraint. He thinks about God, vastness, the otherness of others, the beauty of beauty, the difference between reality and truth, the nature of friendship. He thinks about these things profoundly—but he, and the Susie with whom he hopes he's actually traveling, always sound like kids.

Here, for example, is Calvin pondering the great silence of the lake.

When you've lived all your life with the sound of Life in General, you don't even hear it anymore. You don't hear the noise of cars, trucks, trains, airplanes, refrigerators, air conditioners, furnaces, and you don't feel radio and television waves shooting through you, and you don't hear telephones, animals, birds, floors creaking, doors opening, the voices of six billion people all talking and laughing and crying, and over a billion cows mooing and nineteen billion chickens clucking and a million species of bugs buzzing and you don't realize that it all adds up to this low hum of Life in General.

Life in General doesn't live in the middle of the lake.

There's a touch of autobiography in almost everything we read. Or we, as readers, can pretend (to ourselves) that we've pierced the veil. So that when I came upon this next passage, I thought about Tim talking about Martine—a writer far more invested in making than self-glorifying. Susie and Calvin, stranded out in the bitter cold, are wondering why Mr. Watterson has remained elusive. About why he stopped drawing Calvin and Hobbes, about why he's not talking to the press (or to these two kids).

It's the end of the year. I've not read half the books I should have read. I'm trying now to make amends in between corporate deadlines. But this Martine—I'd like to do some promoting for her. She's a writer we all should read. We could learn a lot from the humanity and originality of her prose. We could learn how to be artists, too.

He's just not a sellout, is all. He thinks selling out is buying into someone else's values. Or maybe he knows there's power in creating something and then stepping out of the way. All that silence, that refusal to show up for adulation—it forces you to look harder at the creation itself, like he's saying, this is what I have to say. You laugh, you cry, you think, you change—and that's the point.

And as for you, Mr. Tim: I'm going to try to slip a zeugma into some annual report writing today.

Published on December 18, 2015 04:46

December 17, 2015

What else have I missed? Lucia Berlin asks us to look harder.

I have a neighbor who is addicted to renovation. Not a week goes by without the grrrr of a truck, the song of a carpenter, the buzz of a saw in a tree. I'm renovation shy myself. I do what needs to be done only when it must be done. Only when I force myself to see that yes, the roof is leaking again, or the bathtub crack hasn't put its own sutures in, or, unless I take some action now, I won't have a working oven.

There is a lot that I don't see. There's a lot that I forget after I see it. There are details that go to insta-blur. I remember, for example, a pink dress, a long table and its drying watercolors, Jethro Tull playing through a rickety box, and a bottle of linseed oil stashed where most might stash some food, all of which equals the day I fell for certain in love with my husband.

But what else was there? I could search my memory for a very long time, but if I didn't see the greater details first, if I didn't notice then, I've got nothing now.

This week I read Lucia Berlin's extraordinary collection, A Manual for Cleaning Women. The stories are primarily (we're told) autobiographical, except when Berlin felt the need to exaggerate for effect. Many "memoirists" will exaggerate and call the story a memoir. Thankfully Berlin does not. We read her and know a version of her. We sift our way through the authentics. She makes no claims, except on our imagination.

In the final story in the collection, Berlin's narrator—tethered to an oxygen tank, full of Berlinesque thoughts—looks back over the what if's of her life. She seduces us until we're caught in the snare of her possibilities, then snapped back to her quasi-fictional now. The character watches crows crowd a tree and wonders why she never sees them leave at dawn. She wonders what else she hasn't seen, what else she hasn't done.

Here, early, she worries over details missed. I find this passage extraordinary because I'm not sure I've ever read an author of any genre who has read the world as closely as Berlin must have read the world to write her stories.

And yet: What else?

What else?

It's a question for all of us.

I don't know why I even brought this up. Magpies flash now blue, green against the snow. They have a similar bossy shriek. Of course I could get a book or call somebody and find out about the nesting habits of crows. But what bothers me is that I only accidentally noticed them. What else have I missed? How many times in my life have I been, so to speak, on the back porch, not the front porch? What would have been said to me that I failed to hear? What love might there have been that I didn't feel?

Lucia Berlin, "Homing," A Manual for Cleaning Women

Published on December 17, 2015 04:48

December 15, 2015

Lucia Berlin/A Manual for Cleaning Women: Reflections

It's a beautiful object. It's a collection of, to borrow Lydia Davis's reference, auto-fiction. It's the galloping work of Lucia Berlin, who is no longer with us, who is famous now, on all the lists, some ten years since her passing.

It's a beautiful object. It's a collection of, to borrow Lydia Davis's reference, auto-fiction. It's the galloping work of Lucia Berlin, who is no longer with us, who is famous now, on all the lists, some ten years since her passing.What would she make of her fame? What would she do with it?

You read these stories and you think—perhaps they're not stories. Perhaps they are the beads of an abacus—pushed in this direction, pushed in that, always (reliably) adding up to something. These pieces may be insistently compact, but they are never rushed, they are never a detail short, they are never mere asides. They're some of the most intimate interludes I've ever read—parabolically witty and (at the same time) deeply unsettling.

We meet:

A child who helps her grandfather pull all of his teeth. A woman who believes herself to be generous in ways others do not. An alcoholic who cannot help herself. A sister who reconciles with a dying sister. A seductress who shows up in all the stories men tell. A nurse. A cleaning woman. A daughter tending an unwell mother. An unwell mother mothering sons. An unfaithful adventuress.

And then the stories cycle through and some of the same characters with the same names appear again and we already know them, we bring our growing knowledge of this singular storyteller's band of characters to every story that she tells.

Like Colum McCann in Thirteen Ways of Looking, Berlin sometimes dabbles in the meta, comments on the commentary, leaves overt clues regarding how her stories get made.

From "Point of View":

You'll listen to all the compulsive, obsessive boring little details of this woman's, Henrietta's, life only because it is written in the third person. You'll feel, hell if the narrator thinks there is something in this dreary creature worth writing about there must be. I'll read on and see what happens.

Nothing happens, actually. In fact the story isn't even written yet. What I hope to do is, by the use of intricate detail, to make this woman so believable you can't help but feel for her.

At other times, as in her title story, Berlin appears to be rattling off observations about the houses she cleans, but that's not really her point at all. Her point is what happens when the pattering noise of her daily living gets interrupted by the deep abyss of sadness that she feels:

My friends say I am wallowing in self-pity and remorse. Said I don't see anybody anymore. When I smile, my hand goes involuntarily to my mouth.

And you stop. You press your hand to your mouth. You feel her pain.

Berlin creates a familiar terrain, but she doesn't repeat herself. She generates a recognizable voice, but it has energy, it is not dulled by repeated use. I had the feeling, reading these stories, that I got when I read Jenny Offill's Dept. of Speculation. Something new, I thought. Something bold. Something classic. Berlin is alive on these pages.

Published on December 15, 2015 17:33

December 13, 2015

dim the noise of the world; spend an afternoon at an indie

At the Big Blue Marble Bookstore on a warm Saturday afternoon, I sat with Elliott batTzedek and Sarah Sawyers-Lovett (of Book Jawn Podcast) and talked.

At the Big Blue Marble Bookstore on a warm Saturday afternoon, I sat with Elliott batTzedek and Sarah Sawyers-Lovett (of Book Jawn Podcast) and talked.Oh boy, did we talk.

About what happens when authors become brands. (It isn't pretty.)

About what happens when an author remains true. (Or, put another way, when an author, despite her success, works as hard and as fierce and as brave as she once did, before the world knew her name.)

About what happens when an author puts more stock in a trend than in her own imagination. (Leveraging a movement to the detriment of the story she might have told, for the making is always more important, ultimately, than the marketing—or shouldn't it be?)

About how picture books work. (Which is to say, how picture books stop time, in the hands of those who want to fully feel.)

About Kent Haruf, Sy Montgomery, Spirographs, Pigeons, A.S. King, Coates, Skippy Jon, living among noise, and the life of a ten-year-old community bookstore that serves an intelligent neighborhood and offers up its wares to those who believe in the capital B Book—and put their money where their faith is.

In and out the patrons came. A fifth-grade boy whose mother had to persuade him (gently) out of the stacks. A young man seeking a book for a friend. (David Levithan! Sarah and I said, nearly in unison.) An older man seeking lyrical nonfiction. (H is for Hawk! I shouted out. The Soul of an Octopus! Bettyville! M Train!) Such a seduction, sitting there, listening to what readers want, pointing the way, sharing the life and love of books with two intelligent readers who let me pretend, for part of an afternoon, that I was a book trader, too.

We are living in harsh times. We are trying to rise above the vitriol. We are hoping that the world will see beyond our wearying headlines, our damning theatrics, our brazen banners to the people so many of us actually are.

Look for the compassion, look for the hope, look for the conversation in your local indie. Go home with a book beneath your arm. Allow the wider world to seep in through you.

PS: Sarah. I finished the Colum McCann. I'm now onto Lucia Berlin. You?

Published on December 13, 2015 05:33

December 12, 2015

"All they want is someone to listen." The lessons of LOVE.

On Thursday, while down at the Barnes and Noble off Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, I struck up a conversation with the woman who greets those both entering and leaving the store. It was a warm day, a sunny one, and a breeze was blowing in.

On Thursday, while down at the Barnes and Noble off Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, I struck up a conversation with the woman who greets those both entering and leaving the store. It was a warm day, a sunny one, and a breeze was blowing in."Tell me about your job," I'd said and soon she was telling me stories. About those who come to the store not for books, but for community. About those who come for shelter. About those who, upon hearing her simple greeting, break down and cry.

A man concerned about a child in a foreign place.

A man concerned about a daughter.

Others.

"People think my job is about saying hello, but really my job is about listening," she said. "I'm here to offer simple hope. I'm reminding people to trust in doctors or to trust in others. I'm just letting others know that they've been heard, and that's all that many of us want or need, most of the time."

She was beautiful, this woman, with long ropes of braided hair and very liquid eyes. She had a soul about her, seemed to know just what to say to the repeat customers and the new ones. Hardly a simple job, making others feel welcome. There is a talent to it.

I'm headed to my final signing for LOVE this afternoon—the lovely indie with the fabulous name: the Big Blue Marble. What I've realized, during this LOVE journey, is that this book of mine is the least of it. This book of mine has been an excuse to get out in the world and to see how people are. To listen and reflect on stories.

I'll be curling back in toward my own life after this afternoon. But I have deeply appreciated the many people I have met through this autumn/winter celebration of our city.

December 12, 2015, 2 PM

In-store signing

LOVE, etc.

Big Blue Marble Bookstore

551 Carpenter Lane

Philadelphia, PA

Published on December 12, 2015 07:27

December 10, 2015

fresh from the kiln, after a graceless fall

Never good when you go to bed at midnight and you are up and working at 1 AM. And not very pretty when, hours later, in an all-out sprint in your graffiti Doc Martens, you run to catch a train and fall on the escalator that (darn) keeps going up and up.

Never good when you go to bed at midnight and you are up and working at 1 AM. And not very pretty when, hours later, in an all-out sprint in your graffiti Doc Martens, you run to catch a train and fall on the escalator that (darn) keeps going up and up.Good when you save yourself in the nick of time.

But such a pretty day it was, and so nice to be in the city among friends and a former student and kind strangers. And how nice to return home to three new kiln pieces, collected by my husband earlier in the day. As always, the organic shape is mine from scratch. The well-made bowls are well made by my husband, but glazed by moi.

I'm going to miss the world of ceramics, as new responsibilities force me to put that once-a-week hobby at rest for the time being.

Off to make my first holiday meal for my father and a friend. I'm not sure why I chose to work with new recipes at this hour, this late in the day. But the house is pretty. The tree is up. There is wine. There is the cake baked during a dawn hour.

We will be fine.

Published on December 10, 2015 13:19

December 9, 2015

narrative risktaking, the inherent lessons in the work of Colum McCann

I have a place on my shelf reserved for Colum McCann. An Irish man. A global citizen. A risk-taker.

I have a place on my shelf reserved for Colum McCann. An Irish man. A global citizen. A risk-taker.In his newest book, Thirteen Ways of Looking, McCann provides a master class not just in storytelling, but in story making. The title novella is, on the surface, the story of an elderly man's unwitting final day—his roiling thoughts, his disgust at all the ways the body betrays us, his docking and decking of time, his relationship with his nurse, his lunch with an unfortunately distracted son. It's also a detective story, a whodunnit, and a meditation on the intersection of poetry and life.

Poetry as life?

Life as poetry?

From the novella:

Poets, like detectives, know the truth is laborious: it doesn't occur by accident, rather it is chiseled and worked into being, the product of time and distance and graft. The poet must be open to the possibility that she has to go a long way before a word rises, or a sentence holds, or a rhythm opens, and even then nothing is assured, not even the words that have staked their original claim or meaning. Sometimes it happens at the most unexpected moment, and the poet has to enter the mystery, rebuild the poem from there.

What strikes me as particularly exceptional here is McCann's talent for manipulating the eye of the story—the old man's un-wary first person seamlessly held within the frame of a third-person voice that already knows how this story sadly ends. You could study the mechanics of those transitions for days. How thought bends to action, how interior monologue becomes dialogue, how all the cameras in this story keep titling their angles.

McCann proves how resplendent the effect can be when one leaves every line open to the possibility of a shifted POV.

Watch this:

How many mornings, noon, and nights have I walked up and down this street? How many footsteps along this same path? When I was young and nimble and slick I would dart across the road in Dublin traffic, horse carriages, bicycles, milktrucks, and all. Jaywalking. Jayshuffling it is, now. The jaybird. Mr. J., indeed. On the Upper East Side. A lot of volume in this life. Echoes too.A few weeks ago, when I thought I'd have some time, I planned an essay on narrative risktaking. Had I written that piece, I would have included these seamless POV shifts within my accounting. For this is the kind of risk that interests me—a true master sidestepping the expected not just in what the story is, but how it gets told.

—Just fine.

Sally's hand lies steady on his elbow now. Gripping rather hard into what is left of the muscle. The walking stick in his other hand, propping him up and propelling him along. And why is it that the mind can do anything it wants, yet the body won't follow?....

It doesn't read like flashy pyrotechnics.

It reads like something far smarter.

Published on December 09, 2015 12:07

December 7, 2015

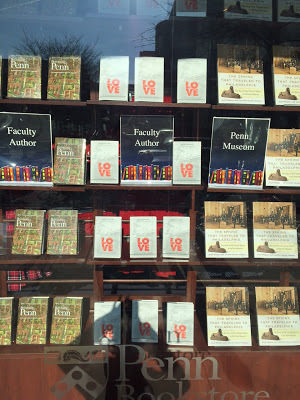

Faculty Author. Two final LOVE signings.

For introducing me to students who change my life and for sharing my books in your store in such a gorgeous, prominent way, thank you, University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Bookstore. For snapping this photograph and sending it my way, thank you, Gary Kramer.

For introducing me to students who change my life and for sharing my books in your store in such a gorgeous, prominent way, thank you, University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Bookstore. For snapping this photograph and sending it my way, thank you, Gary Kramer.There are just two more LOVE signings on the radar. You are, of course, invited:

December 10, 2015, 12 - 2PM

Barnes and Noble LOVE signing

Rittenhouse Square

Philadelphia, PA

December 12, 2015, 2 PM

In-store signing

LOVE, etc.

Big Blue Marble Bookstore

551 Carpenter Lane

Philadelphia, PA

Published on December 07, 2015 07:01

December 6, 2015

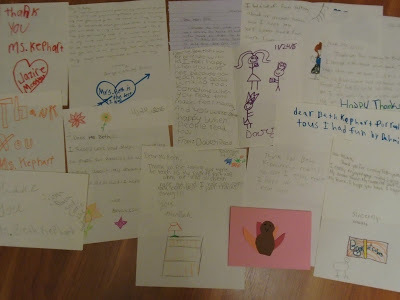

the power of thank you

It has been a fall of vast proportions and very little sleep and soon, soon, I will sit very quietly in a still and silent spot and reflect upon it all. What have I learned? What lessons carry forward?

It has been a fall of vast proportions and very little sleep and soon, soon, I will sit very quietly in a still and silent spot and reflect upon it all. What have I learned? What lessons carry forward?But there is no need to find a quiet space to reflect upon this: the power of thank you. That simple truth—so well known, so often disregarded—was reinvented for me yesterday by the arrival of a yellow-brown envelope from the Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church Tutoring Center, which I had visited two consecutive Tuesday evenings not long ago. I had met with the children of West Philadelphia and their tutors. I had to read to them from books by Jacqueline Woodson, Sandra Cisneros, and others. I had talked to them about language, and what it can do, and then the children had written stories for me. Stood up before their friends and let their dreams ring out.

The joy during those two evenings was palpable. I wrote of one young writer on my blog. I left, and I left them to their stories, but I did not forget their hearts, their faces.

Yesterday, in that envelope, I received their notes, their kindness, their sprawling enthusiasm, their books of dreams, and one fine Thanksgiving turkey. I received the autographs of aspiring writers and inspired readers and home builders. I received these words: "I am really excited that you put me on your blog. That was the best thing that ever happened to me in my life."

The keepsake of this whirring fall. The authenticity that lives in children.

Published on December 06, 2015 03:29

December 5, 2015

what we have is our right now, so who do we want to be?

If the news has driven home any one unassailable fact, it is this: Time is not for wasting. What we have is our right now. The people we choose to be in this moment.

If the news has driven home any one unassailable fact, it is this: Time is not for wasting. What we have is our right now. The people we choose to be in this moment.The man who put his arm around his young San Bernardino co-worker, behind the shield of a fallen chair, and said, "I got you." The brother who had the courage to stand before cameras and say, "Like you, I am in shock, I do not understand." The colleagues of the fallen, who have chosen to use their time before CNN cameras to raise up those who lost their lives.

We can be bitter, angry, hopeless in these days of awful violence and crass politics. (I sometimes am.) We can also be people alive, people grateful for the days we have and for the company of each other, people who avoid the quick conclusion, the radical exclusion, the questionable claim. We can be people tapping at the roots of that immeasurable goodness that still offers itself to us, and we can be part of the good.

For the past week I've been talking to someone I deeply love about the question: How do we become who we hope to be? A question preceded by a question: Who do we hope to be? Maybe the answers involve curiosity, engagement, activism. Maybe they involve tipping the balance between receiving and giving. Maybe they involve being more honest and more willing to convey that honesty. Maybe they involve new bravery, less waste, more direct appreciation for the lives we lead.

If anything good can come from the very much bad that blares at us through the news, it is the urgency now incumbent upon us to shake off the fog, yank off the mask, straighten the spine, and fully (but not selfishly) be. To live each day like the gift it is. To do better by ourselves, so that we can do better by us all.

Published on December 05, 2015 04:06