Beth Kephart's Blog, page 29

January 12, 2016

On Writer Envy and The Narrow Door, by Paul Lisicky

I have wondered (not infrequently) if envy rankles writers more, deeper, better than it does organic farmers, say, or pastry chefs, or people who build fences. What is it about what we do that makes us, as a category, cagey, needy, whiny—quite sure that whatever success we have is hardly equal to the success we have (surely!) earned?

I have wondered (not infrequently) if envy rankles writers more, deeper, better than it does organic farmers, say, or pastry chefs, or people who build fences. What is it about what we do that makes us, as a category, cagey, needy, whiny—quite sure that whatever success we have is hardly equal to the success we have (surely!) earned?Why do (too many) teachers step away when their students seem, even for a moment, to out-write them?

Why do (too many) friendships falter in the wake of one person's good news?

And how many writers have felt themselves forced to subsume their own dreams and bury their own gifts, so as not to challenge the presumptive status quo? I shall listen long to you, they say to the Supreme Other, their heads bowed slightly. I shall sing the song of you. I shall see you, always, as the True Talent, and I shall never tip this balance, never hope that you'll read me, never hope that you'll root for me, never hope that you'll truly see me.

Oh, writing. Oh, writers. Why does our blood run green, or thin?

In The Narrow Door, Paul Lisicky takes a devastating, and devastatingly beautiful, look at the two treasured friendships of his life—the one that developed early in his life with the novelist Denise Gess, and the one upon which his marriage to a poet he calls M. is based.

Denise is sexy, consuming, interesting, seductive—and while these two talk of many things, sometimes for hours every day, Lisicky manages (perhaps because Denise does most of the talking?) to keep from her his secret affection for men. Denise will tuck her arm into Lisicky's, take him on novel-building adventures, allow the world around them to imagine that they are a happy couple, read her best lines to him. She will name a character for him in her second, less-successful novel, she will betray him, they will lose touch, and they will enter, again, into each other's orbit—deeply. Lisicky will be there for Denise as she lives the final hellacious months of a deadly cancer. He will love, and eulogize, her.

M., meanwhile, is already famous when Lisicky becomes his lover, then husband—famous and famously grieving for a man who has died of AIDS. M. is the well-paid poet-celebrity. Lisicky is the talented, handsome lover—the one with whom M. has important conversations, and the one whom Lisicky, it is suggested here, is never to overshadow.

Not only that but, perhaps, Lisicky is not to overshadow the long-gone former lover. Lisicky, helpless, tries:

To think you can love someone so well that he'd forget the dead, forget his pain. To think of love as a laser beam of attention. To think you could beam that attention toward him in such a way that he wouldn't even know you were doing it. To learn that your attention is doomed. Unwelcome, better having been put to other uses: helping the poor, working for the environment, for animals. To learn that you are only a pale winter sun, when you once thought you could have made the hillsides green.

This is a book built of slipped time and interweaves. We see Denise vibrant, we see M.'s charms, we see the turns these friendships will take, the toxic releases, the unspoken hurts, the flailed anger, the unstoppable rise of Lisicky's talent and the costs of that said talent. Denise is near death; she is alive again. M. and Lisicky are in love; the love is breaking; the love is new. Propelled forward. Slung straight back. The year is 2010, 2004, 2010, 2012, and what does it matter what order the numbers fall in? And in between, the gnarly earth hurls lava up through volcano spouts, tsunamis speed toward shorelines, hurricanes smash into lives; Joni Mitchell sings. The world may be so much bigger than one man's woes, Lisicky says. But also: the world speaks directly for and of them.

What is Lisicky to do—with the talent he has, the love he feels, the respect he has not just for those in his circle, but for his own abilities (deeply proven here) with language? Can the practiced accommodator at long last be accommodated?

For heaven's sake, let's hope so.

Published on January 12, 2016 16:24

January 11, 2016

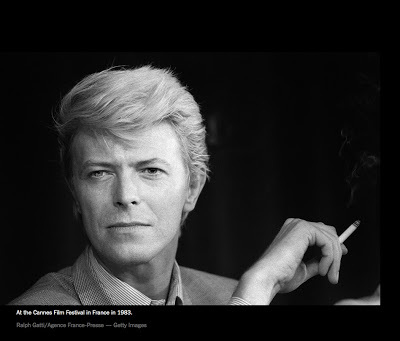

David Bowie, I will miss you.

I danced to you in the basement of my parents' home.

I danced to you in the basement of my parents' home.I knew your words.

I shook the hand of your wife, and trembled for days.

You inspired many pages in my Berlin novel, Going Over, with your own Berlin song, "Heroes."

I am sorry that you suffered.

I will miss you.

Published on January 11, 2016 03:34

January 10, 2016

STORY OF YOU giveaway. And: When these two cousins asked to be put inside one of my novels, I said yes, of course

January 10, 2016:

January 10, 2016:It seems a very long time ago—this trip to Alaska, taken with my father. The whales and the blue ice, the New York Times journalist and the famous screenwriter, the naturalists and songs.

We made friends.

We've kept them.

Among our friends are two dear cousins, Sarah and Gillian. As I mentioned in this post below, originally published in July 2014, they asked, all that time ago, for a place inside one of my novels. This new novel that I would surely write had to have an adventure at its heart, they warned me (guessing, perhaps, that I was literary and dull). Something had to happen. It took me a while, but that story became the story that now is This Is the Story of You —a fact I mentioned in a recent email to the cousins' lovely literary grandmother.

A sea is involved. A storm. An adventure. An eradication of home. (Note here, in today's Chicago Tribune essay, my obsession with home.) A discovery. In these pages, you will find a Gillian and a Sarah. Because I had promised I would.

Yesterday I heard from dear Sarah. She's living across an ocean, still singing her songs, still wearing, she says, those matching PJs. She wondered about that book I'd been writing, wondered if she might read an early copy—put it to good use for a book report.

She now has a copy in hand.

I have one more copy. And that copy is for one of you.

Tell me a short story, in the comments box below, about a sea you once visited or loved or read about. I'll have my husband make a name-blind choice.

You have until January 20. For residents of the U.S. —

July 2014:

On a trip to Alaska: the brighter blues and ceding purples of dawn, the calving of ice (like a dynamite blast), the candy twist of fog between the breaks in hills, the lugubrious faces of seals, the fins and tails of whales, the naturalists and crew we won't soon forget, the Great Young Elly P and her brother Owen (oh, my!), the loving Abi and Ziqin, the people it was easy to adore (grandparents, a pair of brothers, a pair of sisters like sisters to me), and a song that traveled through the green rain of a spruce and hemlock forest, carried forward by blonde cousins.

Gillian and Sarah. Sarah and Gillian. On our boat, on our trails, in our hearts.

"We want to be in one of your novels," they said to me, at the very end, their two faces glowing beneath glow-golden hair.

"What sort of novel would that be?" I wanted to know, and they laughed (for they were capable of such laughter) and explained: A story in which big things happened. Unexpected things. Wow-worthy things. Secret powers lost and found. Adventures spinning forward. Not (most definitely not) one of those dreary novels in which description stands in for plot, character, and everything else.

Something has to happen, they said, they repeated.

They were emphatic. They were two smart girls with big, expressive eyes, and they were hopeful, insistent, ready for the next great book, a Sarah and Gillian book, a story about two girls caught in a fabulous whirl, or, perhaps, in one of their sweet-soprano songs (He sat by her window and smoked his cigar... He told her he loved her, but my how he lied... They were to get married but somehow she died... The tombstone fell over and squish-squash he died... The moral of this story is don't smoke cigars, don't smoke cigar ar ar ars.)

"You can even make me evil," Sarah offered, intuiting, perhaps, that my imagination might not be big enough, my skills not sufficiently wide ranging, my details too soggy for their high-adventure taste.

"Make you evil?" I said. "Impossible."

She laughed her Sarah laugh. Gilly laughed her cousin laugh. These two girls with adventure tastes offering everything they felt a writer might need—inspiration, encouragement, latitude.

Make something happen, they said.

Write the story, they said.

Put us in the heart of it.

They are out there now, and they are waiting. But if, someday, you see a story of mine with a Sarah and Gillian twist, you'll know this: I will have captured only a fraction of the gold that each of these cousins is.

Published on January 10, 2016 04:51

January 9, 2016

Um. Wow. What an amazing Best of 2015 list. Thank you, Hawwa, etc.

I remember where I was and what I was doing when I first read this generous reader's review of Going Over in the Guardian. This morning Twitter alerts me to this. I can promise you that my work has never appeared on a list that also features F. Scott, a writer whose portrait now hangs in my living room (for inspiration's sake). I'm going to hold onto this.

I remember where I was and what I was doing when I first read this generous reader's review of Going Over in the Guardian. This morning Twitter alerts me to this. I can promise you that my work has never appeared on a list that also features F. Scott, a writer whose portrait now hangs in my living room (for inspiration's sake). I'm going to hold onto this.Thank you, Hawwa, etc.

The link is here.

Published on January 09, 2016 03:40

January 8, 2016

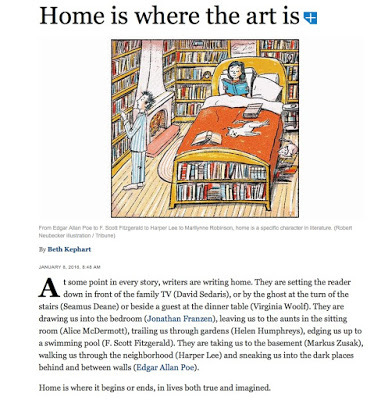

Home is where the art is: a new essay in Chicago Tribune

I've been working out ideas about home and literature, literature and home for awhile now, and on March 1, accompanied by friends A.S. King, Reiko Rizzuto, and Margo Rabb, my colleagues at Penn, and students past and present, I'll be doing even more thinking about the topic for the Beltran Family Teaching Award event at the Kelly Writers House at Penn.

I've been working out ideas about home and literature, literature and home for awhile now, and on March 1, accompanied by friends A.S. King, Reiko Rizzuto, and Margo Rabb, my colleagues at Penn, and students past and present, I'll be doing even more thinking about the topic for the Beltran Family Teaching Award event at the Kelly Writers House at Penn.My newest thinking, in this weekend's Chicago Tribune (Printers Row), with thanks to Jennifer Day, Joyce Hinnefeld, and Debbie Levy, upon whom I seem to first try out my ideas. (Oh, Debbie, you're a gift.)

To read the whole story, go here.

Published on January 08, 2016 17:32

January 5, 2016

I failed. I'm glad. Here's to being me.

A few months ago I was invited, last minute, to an audition and I, against my better judgment, said yes. I had but a week to prepare, I had another event that day, there really wasn't time, I was already exhausted by a spate of too many speaking engagements and a summer/fall of physical labor and countless everyday concerns, but I failed to say the right thing: No.

A few months ago I was invited, last minute, to an audition and I, against my better judgment, said yes. I had but a week to prepare, I had another event that day, there really wasn't time, I was already exhausted by a spate of too many speaking engagements and a summer/fall of physical labor and countless everyday concerns, but I failed to say the right thing: No.Instead, I gave my all (or the all I still had) to the job at hand, rushed to the audition at the break of one dawn, then rushed back to the event where I was actually supposed to be.

And then, in a mass, impersonal email, the invitation givers said no.

I could not, I realize, be more relieved.

I lost months in 2015—of time, of income, absolutely, but also of the solitude and the room I need to make better decisions. Over the past few days I've sat on the couch beneath a blanket doing what I love best—reading books and thinking about them, writing sentences of my own. In doing that, I've reclaimed some of the parts of me. Odd and imperfect as I most surely am, I discover that I've missed me.

There will be less of me out in the world in 2016. There will be more considered responses to last-minute invitations, requests, expectations. There will be me asking me, Do I really want this, and why, and how much do the people asking actually care about me, actually need or want specifically me, actually think of me as me (and not as a willing convenience), and will, at the end of all my effort, a mass, impersonal email await me?

It's up to me to make the choices.

I'm going to try to make the right ones.

Published on January 05, 2016 06:19

January 1, 2016

the mushroom dropped; our friends are the best; happy new year

Published on January 01, 2016 08:30

December 31, 2015

to the new good, for all of us

Last night I saw a movie ("The Danish Girl") I have long wanted to see, and it was gloriously visual and terribly heartbreaking and genius acting, and it was good. Afterward, my brother called and we talked for a long time (I talked to his daughter, too) and all of that was good.

Last night I saw a movie ("The Danish Girl") I have long wanted to see, and it was gloriously visual and terribly heartbreaking and genius acting, and it was good. Afterward, my brother called and we talked for a long time (I talked to his daughter, too) and all of that was good.In the dark hours before this dawn, I began to read the memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes, and it is good. I set the Hare aside to sketch out the outline for a new and interesting (to me) nonfiction book, and I think it will be good.

After the sun rose I added fresh mint to the strawberries, the banana, and the coconut water, spun the Ninja, and that breakfast smoothie was good. I went online and found a very generous LOVE citation on Savvy Verse and Wit Best of the Year round-up (thank you!) AND ALSO an uber kind citation for ONE THING STOLEN, and that was good and very good.

Today we will see dear friends in a new place, and it will be (it always is with them) good.

This is the last day of an old year. The sun (which hasn't made much of an appearance lately) has decided to show up, and I'm hoping that augurs something new, something good, for all of us. I'm hoping that the unsettling headlines dim, that our planet is respected, that terror is abated, that homes are found for those seeking homes. I'm hoping that more people do happy things. I'm hoping the people I love get good news, have good health, have good dreams come true.

I'm hoping that for strangers, too.

To the new good, for all of us.

Published on December 31, 2015 07:11

December 30, 2015

remembering my mother

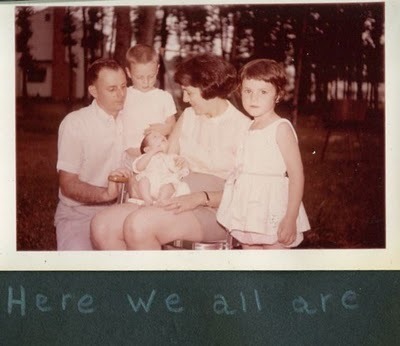

Five years ago, I posted this tribute to my mother, who we lost on December 30, 2006. Thinking of her now (as I often do) and looking back, it seemed most right to share something I have shared before.

Five years ago, I posted this tribute to my mother, who we lost on December 30, 2006. Thinking of her now (as I often do) and looking back, it seemed most right to share something I have shared before.There are many memories. But, sometimes, few words.

Today is the anniversary of my mother's passing, and in remembering her, I have gone back to old photographs, to this one, in particular, of my mother, father, older brother, younger sister, and me; that is my mother's white pencil caption, below. I return to the words I shared during her memorial service. Lore Kephart passed away four years ago, but she is present, still.

@font-face { font-family: "Times"; }p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

On the morning after the evening that my mother passed away, the sky was sherbet colored—bold and also delicate pinks, upward-rising tangerines, traces of lemon. It was the sort of sky one only rarely sees in winter—complex and unforgettable and outrageously beautiful—and it was, of course, my mother, at peace at last. She had brushed by me, on her way to heaven, the night before—the gentlest knock on my right shoulder. She had gathered around her, in her final days, so many varieties of kindness in the doctors and the nurses who had come to care for her, so many reminders that goodness, after such sadness, reigns. She had left behind parts of her to discover still—a note stuck in a bible, a photograph no one remembered taking, the namesake song “Dolores” playing in a nearly empty restaurant. On the day of my mother’s funeral, a warm breeze blew. It was her; there is no question. She wouldn’t leave us lonely. Beauty is the art my mother mastered. For her, orchids kept their angel wings for surpassing months on end. For her, the mashed potatoes always whipped up right, the gravy thickened, the turkey cut tender to the bone, and anyone who ever had my mother’s chocolate-chip cheesecake was never, in some way, the same. She made the dresses my sister and I wore as little girls. She embroidered flowers into our collars. She filled her house with color, fabric, texture, and light. With conversation and surprise. With gifts—abundant, always. In the weeks since my mother’s passing, I have been pondering the many measures of a life—that which dissipates, that which remains. I have been looking up, studying the skies. I have been watching the greening of the stalk of curly willow that sits in a vase in my most sun-filled room. I have considered spring’s rumbling things, impatient, even in winter, to rise. I have been blessed—immeasurably blessed—by the outreach and wisdom of souls like you, and I have made my decision: Beauty remains. In the words she put down on a page, in the friends she gathered around her, in the gifts only she had the talent to give, in the orchids that yet bloom in her deep-silled windows, and in the man who was her husband and is my father, my mother, always a beauty, remains. Winter will soon cede to spring, and she’ll be here. The moon will blaze bright through an afternoon haze, the stars won’t leave the sky at dawn, a fox won’t run when you walk by, and in all of this, you’ll find my mother. And in a garden called Chanticleer, between the risen roots of that most magnificent Katsura tree, there will, come summer, be a stone that reads The Wedge of Sun Between Us. That stone will be my mother’s stone. Perhaps she’ll find you there.

Published on December 30, 2015 03:27

December 29, 2015

Still life with a flawed Fitbit. A flawed me?

All right, yeah, sure, of course. I'm a tad obsessive. Only vaguely competitive with the outside world. Insanely competitive with myself. Best part of me, if you ask a client or an editor or a student or a partner (or a high school teacher) is that I always beat a deadline. Worst part of me, if you ask my friends (or most anyone else) is that I'm morosely consumed with besting my best. If I walked five miles yesterday, why can't I walk six miles today? If one of my books got four stars, how can I live with a mere two stars today? Or (OMG!!) just one? None?!?!??!? And if I managed not to eat any cookies this morning, why the heck can't I stop myself from eating one cookie (two cookies?) this very night?

All right, yeah, sure, of course. I'm a tad obsessive. Only vaguely competitive with the outside world. Insanely competitive with myself. Best part of me, if you ask a client or an editor or a student or a partner (or a high school teacher) is that I always beat a deadline. Worst part of me, if you ask my friends (or most anyone else) is that I'm morosely consumed with besting my best. If I walked five miles yesterday, why can't I walk six miles today? If one of my books got four stars, how can I live with a mere two stars today? Or (OMG!!) just one? None?!?!??!? And if I managed not to eat any cookies this morning, why the heck can't I stop myself from eating one cookie (two cookies?) this very night?And jeepers: What are these wrinkles doing here? I did not have such wrinkles last year.

See what I mean? I'm freaking impossible.

I'm not completely sure, then, why my long-suffering husband decided to get me a Fitbit for Christmas. "Aren't I awful enough?" I asked, when I unwrapped the generous gift. "Is this an experiment? Are you trying to see just how self-inflictingly awful I can become?"

"You know you want it," he said.

But here's the thing: My Fitbit doesn't like me.

I run for 30 minutes and it says I've burned 148 calories. I dance for 30 minutes; calories consumed: 148. I walk slowly, meanderingly, philosophically with my son for 30, count 'em, minutes and guess what? I've burned 148 calories.

My Fitbit is making fun of me.

Or how about this: I run up and down and up and down and up and down the stairs, doing the laundry, doing the cleaning, doing the things this woman does. According to my Fitbit, I've done no such thing. Indeed, my Fitbit must think I live in a rancher: It says (daily now) that I've climbed precisely 0 stairs.

Or I sleep for just three hours and it claims I've slept for ten. What the hell, Fitbit? What the hell? I'm working over here. Working. Can't you see?

Or I run around at the grocery store, then run around the kitchen, then run from pantry to stove to pantry—run, I say—and after two whole hours have gone by, my Fitbit declares that I've had 15 active minutes.

What? Scraping, chopping, stirring isn't active, Fitbit? What do you want from me? Please tell.

I don't know, or I do know, and I've already said.

My Fitbit doesn't like me.

It's not the first to feel that way.

Published on December 29, 2015 17:04