Beth Kephart's Blog, page 28

January 26, 2016

here you begin (today at Penn, with Dillard and Didion)

Annie Dillard and Joan Didion will be our guides today in English 135. Voice and meaning will be our quest. We'll consider, for a moment, these two sentiments.

Annie Dillard and Joan Didion will be our guides today in English 135. Voice and meaning will be our quest. We'll consider, for a moment, these two sentiments.Can both be true?

“Why do you never find anything written about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to, about your fascination with something no one else understands? Because it is up to you. There is something you find interesting, for a reason hard to explain. It is hard to explain because you have never read it on any page; there you begin. You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment." — Annie Dillard, “Write Till You Drop”

And from this:

"We are all brought up in the ethic that others, any others, all others, are by definition more interesting than ourselves; taught to be diffident, just this side of self-effacing... Only the young and very old may recount their dreams at breakfast, dwell upon self, interrupt with memories of beach picnics and favorite Liberty lawn dresses and the rainbow trout in a creak near Colorado Springs. The rest of us are expected, rightly, to affect absorption in other people's favorite dresses, other people's trout."— Joan Didion, "On Keeping a Notebook"

Published on January 26, 2016 05:28

January 25, 2016

let's talk about book courage

It should have gotten easier. In fact, it has not.

It should have gotten easier. In fact, it has not.Because I always forget. I always forget when I am writing my books—happily writing my books, lost in my books, compelled and impelled by the making of books—that at some point along the way the book that is privately mine will no longer be private or, even, mine. It will be an object to be dismissed or discussed, dissed or shared. It will have very little to do with me, except that it is all of me, a part of me, an emanation of my heart, a hope.

Time and again, I have told myself that I can quit, that there are other ways, that the book biz is too cruel a biz (too tilted, unfair, overly made; too much about the in-crowd and the out-crowd; too forced a spectacle). And then: There I go, back to the couch with some paper and a pen because I cannot help myself, because I am most at peace while writing, because the stories demand to be told, because I somehow forget how being published feels, because books themselves aren't the problem here; it's the selling of books, which is different. I'm not a brand. I'm not a platform. I'm not a trend. I don't know how to be those things. I don't really have any business doing what I'm doing, except: writing is who I am.

Reviews are subjective. Of course. Every reader is a market of one. Absolutely. I religiously do not Google myself, search for reviews, seek Big Attention. I am, every single time, stunned when generous words find their way to me.

And—yes—unspooled when the less generous comes knocking, too.

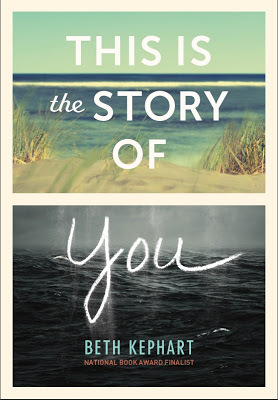

I have been trying hard not to think (in a real way) about the upcoming launch of This Is the Story of You. I have no readings planned, no book-specific appearances, no celebration party, no whirlwind. Still, I realized this snowy weekend, that the angst of the book's release lives loud in me. That I care more than I should about how it will be received. That—especially because Story is so much about the world we live in now, this world of storms and environmental shifts and (still) love and need—I want it to succeed. I want it to find the right readers. I want them to love my Mira Banul and her brother, Jasper Lee, and her friends, and that beach. I want them to think about our world, the sand, the wind, the rising seas.

I write all of this because early this morning, 4 AM, when I woke to work on the first flight of student assignments, I was alerted a flurry of tweets about Story.

A very early reader speaks.

I am embarrassed by how much this means to me. But it means so much to me.

Published on January 25, 2016 04:18

January 24, 2016

thoughts on Philadelphia's Grand Lady (and freedoms, artistic and otherwise), in the Inky

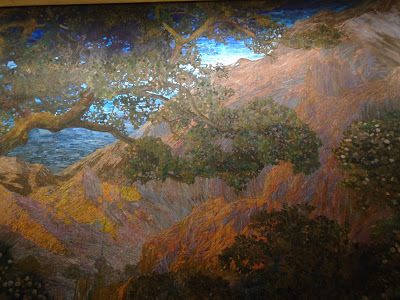

Last Friday, as readers of this blog know, I took my father to the Academy of Music to see the fabulous musical "Once." Before we got there, we toured the birthplace of American liberty and sat within the spell of Maxfield Parish's "Dream Garden."

Last Friday, as readers of this blog know, I took my father to the Academy of Music to see the fabulous musical "Once." Before we got there, we toured the birthplace of American liberty and sat within the spell of Maxfield Parish's "Dream Garden."I write about that in today's Philadelphia Inquirer.

The link is here.

Published on January 24, 2016 07:51

The Dogs of Littlefield/Suzanne Berne: a Chicago Tribune review

Well, I certainly loved this book and highly recommend it to anyone who feels stuck in a pre-packagedly perfect version of suburbia—or stuck inside the angst that comes from knowing that there is no achievable perfection.

Well, I certainly loved this book and highly recommend it to anyone who feels stuck in a pre-packagedly perfect version of suburbia—or stuck inside the angst that comes from knowing that there is no achievable perfection.The whole is here, in today's Chicago Tribune.

Published on January 24, 2016 02:31

January 20, 2016

This Is the Story of You Giveaway (and the winner(s) are...)

A few weeks ago, when I posted the THIS IS THE STORY OF YOU giveaway, I hoped for a handful of stories about the sea—quick imagery.

A few weeks ago, when I posted the THIS IS THE STORY OF YOU giveaway, I hoped for a handful of stories about the sea—quick imagery.What happened instead is that some very beautiful memories, shaped inside some very beautiful sentences, came my way.

And then I was stuck. How could I choose (even randomly) a single winner?

With thanks to Lara Starr and the entire Chronicle team, I do not have to. Please read below the words that floated my way for this giveaway. All of you here have won. Please send me your mailing addresses.

Hilary Morgan:

There is a sea in Scotland, bordered by a black beach. A beach of stone, covered in seaweed. The sea is a brilliant color, a stark contrast to the dark shore. The sea is almost so enchanting I almost don't see my friend slip on the sea-wet seaweed and fall right on his back. But I do, and this trip to the hardened coast of Scotland is all the more memorable.

Jennifer Hoppins:

I've only ever taken one trip with my daughter, just the two of us. Although we've shared years of family vacations there was this one adventure we had---to celebrate my graduation from college. I had read in a travel guide about this place on the Outer Banks where you could go hang-gliding near the beach. Not a big risk taker, I surprised everyone by saying that this, more than anything was how I wanted to mark the occasion---by soaring on the breeze. On the evening after our solo flights (a feeling that now makes me jealous of all birds, even vultures!) we got a permit to have a campfire on the beach. That night, my teen daughter opened up and talked to me, laughing and being completely free, as if the roles of mother and daughter had been erased, and we were simply people who loved one another. I will remember her face in the dark, while the waves rolled in under the full moon, always.

Melissa Sarno:

A sea story... I learned to swim at my Aunt and Uncle's house on Bayville beach, thanks to Aunt Angie. She wasn't actually my Aunt. She was, just, everyone's Aunt. She wore a bathing suit with a skirt that bubbled up and ruffled around the surf and she called herself 'a waterbaby'. I don't even really know what that means. But she held on to my belly while I kept my chin high and I paddled and paddled above the safety of her arms. And when she decided I was ready, she let go, and I magically stayed afloat, chin up and paddling. Every year, somebody somewhere at some family function will mention Aunt Angie and, inevitably, that person will say, 'she taught me to swim at Bayville beach' and her sister will say, 'she taught everyone to swim at Bayville beach. She was a waterbaby.'

Colleen Mondor:

I can not tell you only one story about the sea; I can only tell you I have thousands. When you grow up on the ocean, when your feet are in the sand before you can walk, when you learn to ride the waves by catching them on your father's back, when this is the life you have known then it is impossible to distill it down to one story.

How do I make you understand that there is an ocean, a stretch of beach, that I know better than my own body?

I will give you this then, Beth, one short story, a few lines of what it is to be me and my brother and my father. After my father's surgery, his body cut open to remove a cancer that never left, he asked me to take him to the beach. He had never spent the night in the hospital, had never even broken a bone, and now he was shredded and tired and worn. He was pale; my eternally tanned father was pale.

So we drove across the causeway, looked at the pelicans on the Indian River, turned onto A1A and then up to his beach. He had an "office" there on the sand, he was known as the "Mayor." Every day before his second shift job, swimming with the lifeguards half his age, fishing with us, body surfing with us, listening to ballgames on countless lazy summer afternoons. This was his beach in all name.

I had to help him up the six steps to the boardwalk and he sat down there heavily on the bench, too tired to walk on the sand. He just wanted to see it he told me, he wanted to smell the salt air.

"Now I believe I'm still alive," he said.

I didn't cry. He didn't want me to cry, so I didn't. But it was one of the hardest things I've ever done to keep those tears at bay.

My father died almost three years later and, good Catholic that he was, made arrangements to have his ashes interred in consecrated ground at a church on A1A, where you can hear the ocean's roar. My brother and I, beach babies all our lives, agreed to hold back a small portion of his ashes and my brother took them out into the water a few weeks later as a storm brewed offshore. We had to give some part of him to the sea; it's where he had taught us over and over that he truly belonged.

That's the ocean for me; impossibly connected to the heart of my family. I miss it everyday.

Victoria Marie Lees:

As always, Beth, I love your photos and your words. All the best in 2016! A short sea story/scene:

Can a sea breathe romance? It can if you escape from the daily grind of parenting five beautiful children for a few days’ respite on your fifteenth wedding anniversary.

Two lovers drag their toes in a beach drenched in gritty powdered pink coral; the sea clear as glass displays a dance of sergeant major fish. The sea is frigid for so late in May. At Bermuda’s Horseshoe Bay Beach, the couple reminisces about life and love and strive not to repeat an element of their honeymoon when they both turned as pink as the sand.

Emily Lewis:

The first time my toe touched the ocean I felt like I was hugged by God himself. The smell of the ocean, the crash of the waves and the feel of sand and salt between my toes was truly moving. Coming from Wisconsin I am no stranger to beauty...I am surround by forests, lakes, fields of corn. But the vastness of the ocean...the endlessness of the sea...makes you feel like a speck on the map of the world. It allows you to put life into perspective. How can one not be moved to tears to see the wonders in the world? The hidden treasures are among us...whether an ocean, a butterfly or a snowflake find your wonder!

Published on January 20, 2016 10:09

books in the real world: three surprising sightings and the STORY update

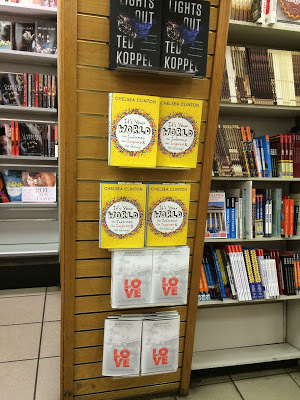

Yesterday, bitterly cold from all the bitter cold, I stopped briefly at the Thirtieth Street Station bookstore while en route to my first day at Penn. There I was greeted with a tower of books featuring Ted Koppel, Chelsea Clinton, and me (

Love

). Everyday, ordinary company? For me, not really.

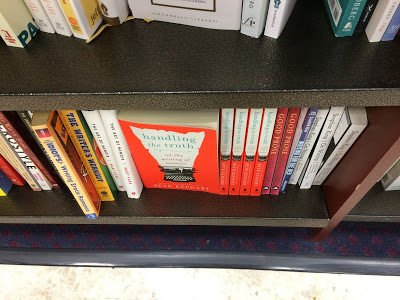

Yesterday, bitterly cold from all the bitter cold, I stopped briefly at the Thirtieth Street Station bookstore while en route to my first day at Penn. There I was greeted with a tower of books featuring Ted Koppel, Chelsea Clinton, and me (

Love

). Everyday, ordinary company? For me, not really.Later, at the Penn Bookstore, I was searching for something else when I discovered all these Handling the Truth's (Handlings of Truth?) beside Mary Karr's much-publicized The Art of Memoir (about which I'd had so many (politely stated) concerns).

Last week I heard from a kind soul who had found Going Over at a train station in Germany.

My point being: We write and then we let our words and stories go. We can't do a whole lot about what happens after that, except to be happily surprised when we're discovered (or when we discover ourselves).

Speaking of books, submissions have now closed for the This Is the Story of You giveaway. I'll have some news about that later today.

Published on January 20, 2016 04:38

January 19, 2016

the new semester begins at Penn with an Adele hello

Sometimes, as the first day of a new semester begins at Penn, I think of how very close I came to saying no to this opportunity all those years ago.

Sometimes, as the first day of a new semester begins at Penn, I think of how very close I came to saying no to this opportunity all those years ago.It would have been one of the greatest mistakes of my life.

And so, again, on this bitter cold day, we begin. We're focused on home this semester. We're reading Annie Dillard's An American Childhood, George Hodgman's Bettyville, and Ta-Nahesi Coates's Between the World and Me, not to mention John Hough on dialogue and countless excerpts (countless as of now, anyway, because I can never tell what's going to inspire me before and during class). We'll be tapping into the new Wexler Studio—recording some of our work. We'll be laying the groundwork for the Beltran evening on March 1—all invited—during which time we'll be visited by my writing friends (and worldly talents) Reiko Rizzuto, A.S. King, and Margo Rabb. We'll hear from former students. We'll write letters to the people in our lives, in Mary-Louise Parker and Ta-Nahesi style.

And today, if all the machines are working, we'll start out with this.

I can't tell you why or how we'll use it.

You'll just have to imagine.

Meanwhile, before any of that, I get to share an hour with Nina and David, who will be writing their theses with me.

How lucky I am.

Published on January 19, 2016 04:47

January 18, 2016

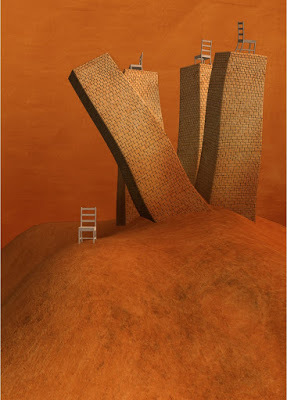

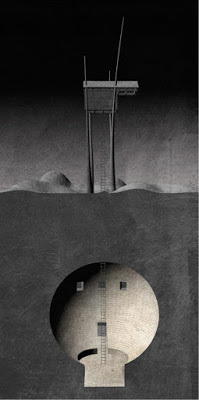

my husband's illustrations

With my husband and I now at work on another joint illustration/word project, I thought I'd share some of his earlier imagery—demonstrating his great range and technical proficiency. If you are in the market for illustrations, I know a guy you can talk to.

With my husband and I now at work on another joint illustration/word project, I thought I'd share some of his earlier imagery—demonstrating his great range and technical proficiency. If you are in the market for illustrations, I know a guy you can talk to.His full website is here.

All work is copyrighted.

Published on January 18, 2016 05:47

January 15, 2016

On looking ahead to this day—among leaders, and in the audience of "Once"

Today I'll give what I'm pretty sure will be my final talk emanating from

LOVE: A Philadelphia Affair

. I'll join Liz Dow, the extraordinary woman behind Leadership Philadelphia, and her leaderly contingent. We'll talk about this city we believe in.

Today I'll give what I'm pretty sure will be my final talk emanating from

LOVE: A Philadelphia Affair

. I'll join Liz Dow, the extraordinary woman behind Leadership Philadelphia, and her leaderly contingent. We'll talk about this city we believe in.The rest of the day will be a father-daughter day. Museums in the afternoon. Dinner. Then my father's early birthday present—tickets to "Once," which won eight Tony Awards, including Best Musical, in 2012.

I. Love. This. Story.

I. Sing. Those. Songs.

And while I gave my father many choices when we were planning out this day, I was secretly very glad when he said that "Once" was his first choice.

So off we will go.

Away, for a day, from here.

Published on January 15, 2016 05:42

January 13, 2016

anonymized characters and the rights of authorship: lessons from "The Trials of Alice Goffman"

The Gideon Lewis-Kraus New York Times Magazine story "The Trials of Alice Goffman" has me stirred up here in the dark this morning.

The Gideon Lewis-Kraus New York Times Magazine story "The Trials of Alice Goffman" has me stirred up here in the dark this morning.My thoughts spin. Let me settle them down.

The deck beneath the headline reads, "Her first book, 'On the Run'—about the lives of young black men in West Philadelphia—has fueled a fight within sociology over who gets to speak for whom." The story goes on to tell the tale of a young University of Pennsylvania graduate (and daughter of a famed sociologist) who spent years immersively studying and writing about "a group of young black men in a mixed-income neighborhood in West Philadelphia, some of the low-level drug dealers who live under constant threat of arrest and cycle in and out of prison."

The book quickly became a sensation. Goffman, and her TED talk, became a sensation. (I remember all of this well; I was watching.) But soon enough detractors spoke. Why did Goffman burn most of her transcripts and notes? Why did Goffman feel the need to write with such colorful flair about individuals and scenes that had been notably (extravagantly?) anonymized? Why did she focus so hard on individuals, when sociology, her field, is about societies? Why did she seem to break (or merely ignore?) so many academic rules? What are the consequences?

And did she have a right to tell this story?

Lewis-Kraus does an excellent job of laying all of this out for the reader—contextualizing the book, contextualizing the field, contextualizing Goffman herself. It is the sort of story the Magazine is best at—big questions, roiling fields of study considered through the lens of a single person or event.

The story is fascinating, illuminating. I'd recommend it to anyone, and I'd especially like to recommend it today to memoirists, on the one hand, and to anyone who is caught up in the many prevailing debates of Young Adult literature, on the other.

Briefly:

In Handling the Truth (and in all my talks, and through all my classes), I express deep concern about anonymized subjects—the extravagant decorations some memoirists apply to the others in their stories. Through Notes to the Readers, we'll learn that most everyone in the book (save the first person I) is a composite—names have been changed, scenes, appearances. At the very least, this is distracting. At the very least, we're being asked, as readers, to apply a filter I'm not sure we readers should have to apply to a genre that's already highly suspicious. Ah, we think, as we meet a composite character, This person is not real. Ahh, again: this person is not real. And if this person isn't real, if she really isn't a twin and she really isn't wearing a marigold dress and she really doesn't talk with a nasal quality, what else about this scene isn't real? What are we supposed to believe? Is there truth inside this memoir?

(Often, of course, there is truth inside that memoir. But the reader has to find it.)

Last week I read a memoir for review that is truly lovely, but as a memoir built of composites, I felt a distance. Yesterday I read Paul Lisicky's memoir of friendship The Narrow Door. It is not a memoir built of composites. Lisicky names names (names many readers will know). When he can't fully name a character he uses an initial. When he really can't name a character (one single case), he gives her a fake name and tells us he is doing that. Not a composite, then. Just an indirect pronoun. There's a difference. We're not distracted. We don't have to put up our truth-seeking guard. We can relax into the story.

Goffman's story, as told by Lewis-Kraus, is, in part, a cautionary tale, about what happens when authors go to extreme lengths to disguise the real people at the heart of their stories. They lose track of the disguises. They start writing extravagantly. They put themselves in the way of critics who wonder about embellishments.

Now, onto the question: Who has the right to tell this story?

I can't answer—I don't know—if Goffman overstepped. But the issue has me thinking about a topic that is lately swirling through Young Adult literature. The right to ownership of story. Can a man write convincingly as a girl? Can a woman write convincingly as a boy? Does the American living in California have the right to tell the story of a child of Haiti?

Young Adult literature, obstensibly, is written for teens. It is written to reach the hearts and souls and minds of young people on the brink—young people facing bullies, uncertainty, challenge, any number of things; young people who are in need of compassion. And yet, among Young Adult authors and advocates, a storm has broken out. Swirling questions. Who is allowed to tell this story?

Fiction is not memoir, of course it's not. But it still requires fidelity to emotional truth. I can't, for example, pretend to know what a young woman of 1876 might think as she sets out on a hot day for the Centennial grounds. I can't pretend to know what a young man living in East Berlin in 1983 feels, or what a young man living anywhere at any time, for that matter, feels. I can't pretend to know what it is to be rich. I can't pretend to know what it is to be a pregnant teen stuck in southern Spain with a band of gypsies and a cook. I can't pretend to know what it is to be losing my mind to a neurodegenerative disease.

I can't pretend any of that—but I can, and I have, deeply researched. I have gone to these places, I have talked to these doctors, I have read the transcripts, I have sought real people out, I have interviewed the graffiti artist, I have walked the old Centennial grounds. I have used all the resources at my disposal to find out what it might have been like, and then I have written fiction—relying on my heart, my experiences, my imagination to lead me forward. Because I may not have lived the circumstance of some of my characters, but I have lived their fear, I have lived their distrust, I have lived their anxiety, their anorexia, their panic, their kind of sadness, their kind of loss.

I have lived their feelings, I have researched their worlds. Have I had the right to tell these stories?

It's a question, as I say, that swirls. It's a question any writer of fiction might be asked: What gives you the right to write about a martian? What gives you the right to write the character of Don Quixote? What gives the right to imagine yourself on a boat with a Bengal tiger? What gives you, Marilynne Robinson, the right to write the character of Lila, or you, William Faulkner, the right to all those voices inside As I Lay Dying?

I have been married, for thirty years, to a beautiful Salvadoran, and boy has he told me stories. Do I have the right (with his permission) to faithfully reinvent his stories?

What gives you the right to imagine anyone who isn't you?

If we don't have the right to responsibly (and I need that word inside this sentence) write characters who aren't us, then we don't have the luxury of imagining, which is to say empathizing with, characters who are not us.

We need to empathize with the people who are not us.

There are many questions about Goffman's story. I have not read her book. But as we ponder the accounting of Lewis-Kraus let us also ponder the difficulties we encounter when we actively disguise the truth but call it truth.

Conversely, let's think about the difficulties we encounter when we ask writers who choose to delve into (and write of) other worlds, whether or not they have the right. If they have done their research, if they are writing for the right reasons (which is to say, not to capitalize on a trend, not to capitalize on a market, not to capitalize on potential headlines or income), if they have given these projects their heart and their minds, perhaps they have the right.

Published on January 13, 2016 04:24