Beth Kephart's Blog

March 24, 2018

4,215 Blogger posts later, I'm starting clean with a new website

My friends, the time has come.

My friends, the time has come.All of these thousands of posts, over the course of these dozen years. Celebrations of books I've loved, of friends I've made, of kindnesses that have been extended my way.

It's all become a bit much—overgrown, weedy, unkempt.

And so, after cleaning out my father's home and then my own, after thinking hard about who I want to be in the days I still have, after writing and publishing a Woven Tale Press essay called "Clean" about all the things I am learning to leave behind, I am also leaving this blog behind. I'm moving on with a simple web site, which I invite you to enter here.

All thanks to each of you who took the time to stop by, to comment, to share.

All thanks to the friends I made through the books we loved.

All thanks to my husband, who has sat with me and built this new site, scrubbed it down to the essentials. Let the reviews and stars of bygone years be bygone. Let the nuggets of thought get tucked into time. Let the photographs recede.

It's time to start fresh again.

The blog will remain live for any who want to sift back through. But I will no longer be adding to it.

Excerpts from eight of my books can be found on the site.

Published on March 24, 2018 12:33

March 17, 2018

I'll be out; I'll be about: upcoming talks and events

A few upcoming events, as spring makes its way too us (and none too soon):

A few upcoming events, as spring makes its way too us (and none too soon):

April 20/ 7 PM

Keynote Address

1st Annual Writing Conference: Brave New Words

Pendle Hill

Wallingford, PA

May 6 - May 11

Currents 2018

Five-Day Juncture Memoir Workshop

Frenchtown, PA

June 3/2:45 PM

The Big YA Workshop

2018 Rutgers-New Brunswick Writers' Conference

300 Atrium Drive

Somerset, NJ

June 5/7:00 PM

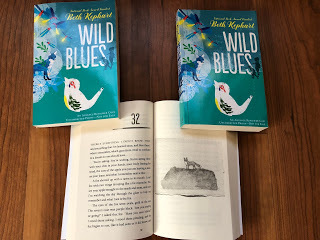

Launch of WILD BLUES

Main Point Books

Wayne, PA

June 10/9:30 AM

The Personal Essay Workshop

Philadelphia Writers Conference 2018

Sheraton Hotel

Philadelphia, PA

September 28/9:30 AM

One-day Juncture Memoir Workshop

Chanticleer Garden

Wayne, PA

Published on March 17, 2018 09:11

March 16, 2018

on spiraling toward the essential, in "Clean," a new essay for Woven Tale Press

What a blessing it is to work with Sandra Tyler at Woven Tale Press. She looks at every word, scours every sentence, asks, and asks with kindness. "Clean," my essay up today on her beautiful literary site, is so much better for having had her graceful interventions.

What a blessing it is to work with Sandra Tyler at Woven Tale Press. She looks at every word, scours every sentence, asks, and asks with kindness. "Clean," my essay up today on her beautiful literary site, is so much better for having had her graceful interventions.With thanks as well to Angelica Gonzalez—reliably kind.

Published on March 16, 2018 04:40

March 14, 2018

Reviewing CENSUS (Jesse Ball) for Chicago Tribune

My review of Jesse Ball's incredible Census here, in Chicago Tribune. So privileged to have read this book.

My review of Jesse Ball's incredible Census here, in Chicago Tribune. So privileged to have read this book.

Published on March 14, 2018 12:54

March 9, 2018

the boy with AXE hair (one image, five sentences, many stories)

My husband's illustration inspired us at Penn again. My husband, whose illustrations will also appear in Wild Blues, due out in June. (This man is good. Check this out, below, and then imagine that fox in color.)

My husband's illustration inspired us at Penn again. My husband, whose illustrations will also appear in Wild Blues, due out in June. (This man is good. Check this out, below, and then imagine that fox in color.)

This time I also share with you some of the work of my glorious honors/independent studies students.

I'm so lucky, right?

Daddy kept the AXE hair gel on the top shelf, said it was his, but Ryan wasn’t so sure. A second grader only has so many tricks to pull—new t-shirt, new kicks—before his style gets old. Even Fanny Wiggins walked past him on the playground to go run through the old pothole. But one else in the class used hair gel yet. He’d be the coolest thing since dino nuggets.

Lauren

He strides to the plate, smirking at the rest of his team with a knowing look. He is the kickball king of Linden Elementary School, and he knows it. The girls in his fourth grade class swoon as he walks the baseline, bending his right knee to prepare for the pitch. With a resounding smack, the toe of his Converse collides with the red rubber and sends the ball into orbit, soaring high above the heads of the pinnie-team like a meteorite thrust into some new gravitational pull. He struts around the bases, unconcerned, smugly jogging back to home base where he scores yet another grand slam.

Erin F.

“Welp, I’m getting out of here,” Darren says to his classmates as the bell rings at 3:15pm. Finally, it was time to relax, Friday was done and that meant the weekend was here. Darren’s mind filled with thoughts of the amusement park he and his friends were headed to on Saturday. Darren heads down the hallway, walking towards his locker contently. The sleep-deprivation from the long week had gotten to him, now it was time for an escape.

Serena

His friends were playing on the playground behind him, without him. He walked away. He heard Billy call out to him, and then a thud. He turned around to find Billy had fallen off the swing setAliya

John was the cool kid I wish I could be. He hung his wallet on a chain and could tie up his yoyo string in the shape of the eiffle tower and still have it bounce back. If I were John, I’d walk around with my nose in the air too, knowing whatever trouble came my way was just passing turbulence. I’m not john though. I’m John’s best friend, which makes me even lukier than the cool kid I wish I could be.

Bri

Brows raised, head cocked, just like his father taught him.“Never look ‘em in the eye, son,” he’d say. “Side eye says it all.”His mess of stiff black hair pulls him towards an alternate expression, but his hunched, thin body remains still. Except for his left hand, pale twitching, uncomfortable by his side.

Jane

He smirked that infuriating smirk, raising his eyebrows impossibly high and drooping his eyelids in a way that said “I couldn’t care less” like only Frank could do. Maybe he slouched his shoulders and hadn’t touched a hairbrush in weeks. But Frank did care, his mother knew. Under that stupid grin he always wore, she knew he didn’t like failing school. She had caught him studying when he thought she was asleep. Why he wanted to prove to the world that nothing mattered to him, she would never understand.

Becca

The boy didn’t mind the outdoors. He knew his sister didn’t like it – too many bugs, she’d say, and the sweltering sun would cause beads of sweat to appear on her face, smudging her painstakingly drawn-on eyeliner. Unlike his sister, the boy longed for the warmth of the sun’s rays on his face, the force of the untamed wind pushing its way through his thick hair. The back of his shirt broke free from his skin, seeming to ripple in the wind, while the front became plastered to his chest.

Lexi

Published on March 09, 2018 04:50

February 28, 2018

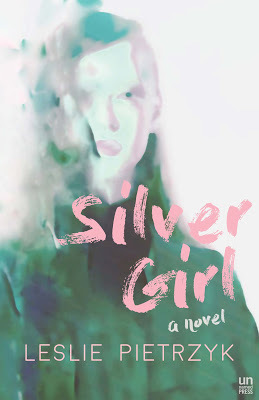

The big lies, the bigger truths of SILVER GIRL, the new starred novel by Leslie Pietrzyk

Let's pretend you want to read one of the most interesting, well-starred books released this very season. One of those, wait, did she really say that, did that really happen, do I really like this character who is lying so much and doing so much wrong and still so very empathetic novels?

Let's pretend you want to read one of the most interesting, well-starred books released this very season. One of those, wait, did she really say that, did that really happen, do I really like this character who is lying so much and doing so much wrong and still so very empathetic novels? Let's pretend you want to know the story behind the story.

Okay, then. We're making this official.

Beth Kephart interviews Leslie Pietrzyk about her new novel, Silver Girl.

Pietrzyk is the author of SILVER GIRL, a new novel set in 1980s Chicago during the time of the Tylenol murders. Her collection of short stories THIS ANGEL ON MY CHEST won the 2015 Drue Heinz Literature Prize, and she has published two previous noKephart is the award-winning author of 22 books, co-founder of Juncture Workshops, editorial director of the nationally syndicated arts and culture show “Articulate with Jim Cotter,” a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, and a frequent reviewer for Chicago Tribune. She recently produced a truth-saturated workbook, TELL THE TRUTH. MAKE IT MATTER.

Don’t look to Leslie Pietrzyk for easy binaries. Don’t think she has easy in her. In 2015 she won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize for This Angel on My Chest —sixteen stories whose subject matter—the early death of a husband—remained fixed while the form, the mood, the accusations, the willingness to confess or not to confess, to blame or to forgive, to tell the truth or to construct the truth remained fluid.

Now, in February 2018, Pietrzyk has published, with Unnamed Press, Silver Girl, a thrillingly voicey novel featuring an unnamed narrator who will do almost anything—monstrous anythings, if you’re measuring by sister and best-friend standards—to cage the monster within. Anything so that she cannot disclose who she actually is and where she actually came from and why she does what she does. She’s at college when we first encounter her—forging a friendship with the girl (this one has a name; her name is Jess) who declares, right up front, love, the word the narrator “longed most to hear.”

Two best friends: like sisters. Except nobody is a sister but a sister, and both Jess and our storyteller have sisters of their own, complicating matters with implicating stories. Both also have histories with men—and ideas about what a man might be, what a man should and should not be trusted with.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, and this is starting to sound like a review, and my point is that with sharp-tongued, sharp-edged episodes that defy chronology and disclosure (but offer up out-of-sequence survival tips) Pietrzyk’s narrator yields a careful, messy life. She has to destroy to live, or so she thinks. She has to take to give. She has become systematically unsympathetic until the frozen ice of her skin shatters and we see (and then might choose to love) the actual person that she is.

Crazy, crazy, crazy. The word appears again and again in Silver Girl. As a joke. As a threat. As an amateur diagnosis. The repetition is intentional, controlled, controlling. So are all the lies. “Most about anyone leaves shit out when they’re telling stories and lies their ass off,” a minor but major character says to a slightly younger version of our unnamed. “That’s what a story is, a long, fearless lie unwinding.”

The lesson has been learned. The story has been made.

I met Pietrzyk years ago at Bread Loaf , where I was writing truth and she was writing fiction. I’m still pondering truth and she’s still bending it, and so I had some questions for her about the slippery slide that fuels this most propulsive book.

Silver Girlis a deck of cards shuffled thrice. We have, in this order, a Prologue, The Middle, The Beginning. The End. Where Every Story Truly Begins. We have, additionally, time stamps, that come at the reader like this: fall, freshman year; fall, junior year; winter, freshman year; winter, before college, and so on. Finally, we have survival tips—numbered (for our narrator is a list maker) but presented out of order. The question is: What calculations did you make as you were sequencing this story on the page? How do the jumbled times and themes comment on truth, memory, and trauma?

This is the only novel I’ve written out of order. Early on, I simply wrote about these two girls, exploring the prickles of their relationship and wandering through their lives by writing randomly to one-word prompts. (I belong to a monthly prompt writing group.) I was no hurry for the bigger story of the plot to arrive…until, suddenly, I was totally in a hurry to hone in on the plot, feeling paralyzed by so much freedom (and so many pages of hand-written material I was certain would burn in a fire or be lost in a flood). What was my actual story? All along, I’d known three things: college girls, Chicago, and the Tylenol murders. So I leaned into what had been revealed in the prompt writing to discover the events of the story and to make meaning of those events.

So that’s the structural answer. But more so, I think exploring one’s life from a distance—as this narrator is doing—likely requires a sideways approach, re-envisioning memories with a clearer, colder eye. And that means all the memories, ALL of them. That’s painful work. The narrator’s revelations on the page needed to mirror that difficult untangling, a sense of spinning through time, literally being unable to tease out which was that first bad turn. I often focus on characters longing to make sense of something awful from a later, safer space, and in each of my books, time is a character of sorts, the way other books might use weather as a character or the landscape. One of my first writerly decisions is how much time will pass in the story I’m about to tell. I ordered and reordered this book a hair-pulling amount of times.

What about this word, crazy? What about the casual fling of “inappropriate” observations about religion, sexuality, race? What about a narrator who can say “I didn’t want to be evil, but I was.” What about the freedom you gave yourself to occupy this narrator’s head without censure? What happens to a novel when the novelist chooses to play by nobody’s rules?

From the beginning, I felt immense compassion for this troubled and troubling girl. She sees herself as fighting the best she can to fit into a world she doesn’t understand (though she imagines she does). Her immense desire to escape made me view her as someone uninterested in the usual rules and best practices. I also pondered the way literature’s males and females have traditionally escaped, or, the “jump on a raft and head downriver” novel vs. the “marriage plot” novel. Honestly, I wanted this girl to escape like a boy. Once I understood that about her, I knew she was going for broke and that I’d let her. It WAS liberating. I could never in a thousand years be so bold. Channeling her determination and desperation set free the novel (and the novelist).

Since we’re at it, you have never played by any rules. How did you learn that you didn’t have to?

Ha! Growing up as a good girl of the Midwest, I’m pretty sure I followed every rule there was. In my ordinary life I’m fairly rule-bound (always on time, standing behind the yellow line, etc.). This Flaubert quotation was pinned on my bulletin board to make me feel better about being so hopelessly Midwestern: “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” But it was around the time that I started working on THIS ANGEL ON MY CHEST, stories about the too-soon death of my first husband, that I started thinking about the “rules” of the writing life: the way New York publishing works vs. the way art is created. My motivating principle became something along the lines of, If I were guaranteed of getting one last book published, what story would I want to tell? (To be clear, I had no guarantee from anyone!) That focus offered clarity and a powerful internal sense of, let’s stop wasting time here. Amazing how easy it can be to shed rules when you see how much time they waste.

“I loved her in a fierce and confused way, like a sister,” the narrator tells us. “I loved Jess for saving me from who I was.” What is a sister? What is a best friend? What is sympathy, and what is empathy, and what is their role in this novel?

These are questions I struggle with, which is why this story grabbed me. I have one sister, younger, and while we’re very different personalities, there’s a core of similarity between us. I wanted the narrator to have this ace, a little sister who’s under-valued at the moment, as family often may be when we’re young. I confess that for me, the best friend is tricky. I have beloved female friends, but not the one and only, the true-blue, the “spill all the secrets to” best friend, unwavering from grade school to death. My past experience has led me to be wary of the “best friend” relationship, which I lament. Isn’t that what we all want, one person who knows and loves us for who we truly are? Is it even logical to expect such a thing? To me, it’s such a miracle when it happens, and that’s the push and pull between Jess and the narrator. They’re living in this miraculous—and fragile—space.

I have sympathy and empathy for each character in this book, for all my characters; I doubt I could write effectively if I didn’t understand who these people are and where they’re coming from. One of my favorite observations about writing—and life—is that no one thinks they’re the villain. It was important to me to expose at least one moment of vulnerability for every character in the book, even those I wanted to despise.

In the novel, I longed to explore this tangle, where our loyalties lie ultimately, what family can do and be that friends can’t, and, at its core, pondering what might be left if there is no family. The popular idea of family as savior is troublesome for those who grew up in a toxic situation or for those whose family members have died or headed for the hills. Maybe they won’t take you in when you show up. Saying we can simply “choose” our own family, as advice columns often do, feels simplistic to me. My narrator wants to connect, with no clear path to do so. How can the heart not ache at such a simple desire?

What makes shame such a fascinating story—to you, to us?

Shame takes us to our most vulnerable space, and when we’re utterly vulnerable, we’re likely either to reveal our deepest selves or to lash out in fear. Or both. That’s what I see this narrator doing. One of my favorite exercises in a writing class is to ask everyone to think about the events from their lives that are the most horrifying to them, the most shameful, the stories that scare them, and to write a list no one will see. “That’s what you should be writing about,” I say. There’s a moment of pure silence where I feel them knowing I’m right.

“I took a deep breath, feeling that superior look settle onto my face, that careful, untouchable composition the only weapon I had, the only weapon I ever had, that mask of utter boredom and vast superiority,” the narrator says, and already, at this point, we understand the source of her badness, the degree of her shame, the events from which she herself could not escape. You have written a blaze of a novel about a seemingly unsympathetic character, and yet I sense that you loved her deeply. Tell us more. Tell us why.

Absolutely: I do love her deeply. She’s the first character I’ve missed writing about after finishing the book. (I even cheated on my current novel-in-progress to write flash fiction about her!) I was pulling for her as I wrote, even as writer-me loaded her with increasingly worrisome plot turns. Like her, I showed up at college utterly ill-equipped, and I worked my ass off trying to catch on to my new environment. I wasn’t the first in my family to go to college, but both of my parents had been, and because no one had explained anything to them, not much was explained to me. Now I understand that most people feel unsteady at the beginning of any vast, new venture, but back then I was certain I was the only one. That vulnerability, that deep desire, that fear of being revealed as a fraud…I just wanted to hug this girl. She does a lot of bad things, but I’m pretty sure we all do.

More and more (and then some) the stories that are emerging—on the big screens and little screens, in the memoirs and the essays, in the novels—center around defiantly irredeemable characters who either ultimately do redeem themselves or don’t bother to (or can’t). Why have we come to this? Why are we thrilled by this? Have we lost our capacity for, or interest in, the authentic quest for truth?

I’m a fan of several T.V shows featuring complicated, bold antiheroes—The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Mad Men—the shows that arguably started the movement. Or did they? I know now that for obvious reasons GONE WITH THE WIND is not a good role model of a book (or movie), but as I grew up in Iowa, its antihero, the conniving and crafty Scarlett O’Hara, influenced me tremendously. Intellectually, I got that I shouldn’t want to emulate her; after all, sweet Melanie possessed Scarlett’s same iron-core strength and resilience. Still, it was Scarlett inhabiting my imagination, scaring me with the rawness of her desires (which were thrillingly selfish). I’d like to see more portrayals of women that show us as the complicated, challenging, flawed people we are, filled with rage and desire…not just “moms” and objects of the male gaze. That’s an authentic quest for truth I can get behind.

Or, maybe this is our authentic quest for truth, antiheroes worming behind the façade of the life-is-good, happily-ever-after bullshit, returning to the original Grimm brothers’ fairy tales, where at the wedding, Snow White’s evil stepmother is forced to dance to her death wearing red-hot iron shoes. We have to know in our hearts that life is not ONLY good, so let’s say so and stare into that dark abyss. Or—maybe the thrill of irredeemable evil is the only authentic truth we can accept during these coarse times. OR—maybe during these coarse times, this darkness is what passes as authentic truth. These are the questions that keep me writing.

Published on February 28, 2018 11:44

February 23, 2018

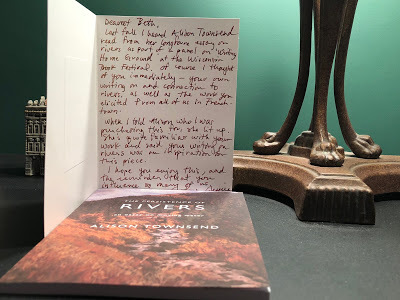

teaching the teachers, and a deeply prized gift

Yesterday, after months of planning, I joined the English teachers of the T/E School District (K through 12) for a teach-the-teachers session. TELL THE TRUTH. MAKE IT MATTER. memoir writing workbooks had been ordered for each of the participants. My job was to connect many of the exercises inside that book to the books that children read. I chose, among others, BOAT OF DREAMS, TAR BEACH, FRIENDS, THE MEANING OF MAGGIE, RAIN REIGN, THE BOOK THIEF, and my own FLOW, GOING OVER, and THIS IS THE STORY OF YOU.

Yesterday, after months of planning, I joined the English teachers of the T/E School District (K through 12) for a teach-the-teachers session. TELL THE TRUTH. MAKE IT MATTER. memoir writing workbooks had been ordered for each of the participants. My job was to connect many of the exercises inside that book to the books that children read. I chose, among others, BOAT OF DREAMS, TAR BEACH, FRIENDS, THE MEANING OF MAGGIE, RAIN REIGN, THE BOOK THIEF, and my own FLOW, GOING OVER, and THIS IS THE STORY OF YOU.What a conversation we had. What work the teachers themselves produced. We moved from nonfiction into fiction, from fiction into truth, from history into the right now, from the personal to the public, from the silent fear to the empathetic gesture. There are few more delightful things for this teacher-reader-writer than to be among other devoted teachers-readers-writers. I was glad for all of it.

I left the program, spent an hour with my husband, then made the half hour drive to my father's home, where I have been spending so much of these past many weeks. I stayed until the near-dark, drove home in rush-hour rain, and dropped my bag on the floor. After a week of barely an hour or two of sleep each night, after so much TV work, so much other teaching, so much corporate America, so many recommendation letters, I was, for the moment, done.

"There's something for you from Jessica," my husband said.

"Really?" I said.

"Open it," he said.

I did. And here from our beloved Juncture friend (read her words in the sidebar here) was a beautiful card, a startling note, a book called RIVERS by Alison Townsend. Out in Wisconsin, Jessica had heard Alison read. Knowing my own obsession with rivers, my FLOW, Jessica had bought me Alison's book. Alison, as it turns out, knew something about me, a circle was drawn, a beginning touching an end touching a beginning, and flowing forward through our Jessica.

There is so much about our lives that we can't understand.

I do understand love.

Thank you, Jessica.

Published on February 23, 2018 04:35

February 19, 2018

One image. Any story. Words from The Big YA at Penn

All throughout this semester we have paused to write a five-sentence story for an image. Most of the time we've used my husband's illustrations to spark the tale, and last week was no different.

All throughout this semester we have paused to write a five-sentence story for an image. Most of the time we've used my husband's illustrations to spark the tale, and last week was no different.What was different is that Katie, a student of many years ago, spent the first half hour of class time with us. Katie, my Katie, who inspired a key character in my novel One Thing Stolen and who has gone on to UCLA, where, as an intern in the OBGYN program, she is already delivering babies.

My students—of now, of then—are hope-yielding. Here, below, are some of their stories. (Katie wrote, too, but her handwriting is truly doctor-worthy, and I feared mis-transcribing her story here.)

My body is grounded in class but my head is up in the clouds, brimming with the stories my mom reads to me every night. Vivid pages of Kings and dragons and knights, faraway lands that are much more interesting than the one I am currently stuck in: the land of math. My hand reaches out and up to catch them all, to hold them close, when I hear my name called.

"Oh! Derek, you know the answer?"

The stories are no help to me now, and they flutter away as my face flushes. I do not know the answer.

Erin L.

My mother insists on leaving the windows open and uncovered all day, all year. It's beyond frustrating. With no blinds to protect me from the sun, I wake up at the crack of dawn. In the winter, I freeze and my skin dries and cracks. It's almost unlivable, but I learned long ago never to ask her why.

John

Published on February 19, 2018 02:34

February 8, 2018

contemplating the single sentence, and celebrating Anna Badkhen, in the new Juncture Notes

What if we only gave ourselves the task of writing a single beautiful sentence each day? I ponder that question, and interview Anna Badkhen about her new book, Fisherman's Blues, in

this issue of Juncture Notes.

What if we only gave ourselves the task of writing a single beautiful sentence each day? I ponder that question, and interview Anna Badkhen about her new book, Fisherman's Blues, in

this issue of Juncture Notes.

Published on February 08, 2018 03:28

February 2, 2018

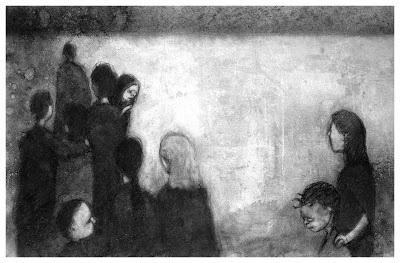

One Image. Many Stories. (2) More work from my MG/YA class

Again, I shared with my beautiful class an image that my husband had created.

Again, I shared with my beautiful class an image that my husband had created.Five minutes, I said. Write the story.

Here are some of the stories.

What is the story to you?

I see the people walking in front of me, their eyes downcast, arms interlinked. My mother urges me to move along, to catch up. We don’t want to be left behind, she tells me. I’m not so sure I agree with her. I drag my feet along the uneven path, my shoelace becoming undone in the process. It’s already lost most of its original whiteness from the dozens of times it’s dragged through the dirt. I idly wonder if, when we get to our destination, I will be able to get a new pair of sneakers.

Lexi

I was quite unsure of where my mama was taking me. We had walked downtown in all black clothes; she slicked my hair back with her frail hands every few blocks. Eventually, I saw faces that I recognized. They were all wearing black clothes... Just like me. Just like mama. I recognized a tall woman with long black hair— my aunt. Her face was more puffy than normal and her eyes were pricked with red. I wondered why she was crying. I wondered why we were here, standing around, wearing black, saying ‘sorry.’

Ania

We avoid it. The void of light. No one should want to be found. To be found is to be known and to be known is to be judged. And punishment is the inevitable nature of judgment’s tight lips, loose gown, and stone grip of opinion.

Gene

"We're almost there. Just keep going." The tall girl bent to whisper in my ear. her hand rubbing "comforting" circles into my shoulder. Easy for her to say; her long legs carried her closer to the promised land while my short, stubby knees wobbled to catch up. There's nothing left in me, no energy to keep going, no will to survive. "20 more miles." she whispers, seeing me struggle to keep from stumbling.

I just want her to stop talking.

Precious

In the darkness we crossed the lake, praying its frozen crust wouldn't give way under our feet. It had been a warm few days, and the ice groaned under our weight. However, a frigid death in the lake would be better than what we left behind.

John

He kicked a rock down the sidewalk, his boot making loud, angry impact with the curb. It hit the back of his sister's shoe, and she twisted to throw a vicious look at him, but she didn't say anything. His mother placed a quelling hand on his shoulder. Whenever something like this happened, his father made his whole family go on one of these walks. Whenever something like this happened, the silence was complete.

Charlotte

His mother’s hand rests lightly upon his shoulder, neither pushing him forward nor backwards. But holding him in place. He does not want to go. He watches in trepidation as the other children are herded towards the empty class full of possibility and brimming with uncertainty. He remembers the stories his older sister tells him of friends and colored squares and story-time, but all he really wants is to sit on his mother’s lap, her arm clutched around him with the other balancing a book, mouth spewing wonderful stories of dragons and knights. He never wants her to let go.

Erin L.

A first funeral - at six, the idea is beyond digestion, an aerial view from her mother's shoulders of the devastation below. She has no emotional ties or any age, truly, to know what she is seeing: a collage of photos of a happy man fishing, a photo with his wife. A scene before her, in human form, a mother's hand on her crying son's shoulder. All he can feel is the vastness of the room, its vacancy of color, the darkness of black ties and tights and tight-lipped apologies for loss.

Erin F.

My fingers have gone through my hair so many nervous times that I can feel it messy and spiky on my forehead. I don’t have anything else left to grab on to. So I reach up, straining my elbow to hold my wrist backwards, and take my sister’s hand. I don’t want it sitting on my shoulder, guiding me like a pet dog with a leash. I need to hold it, to touch reassurance, to grasp some of the resolve with which she looks straight ahead, and walks.

Catherine

I see the people walking in front of me, their eyes downcast, arms interlinked. My mother urges me to move along, to catch up. We don’t want to be left behind, she tells me. I’m not so sure I agree with her. I drag my feet along the uneven path, my shoelace becoming undone in the process. It’s already lost most of its original whiteness from the dozens of times it’s dragged through the dirt. I idly wonder if, when we get to our destination, I will be able to get a new pair of sneakers.

Lexi

The icy wind slapped Jacob in the face, but the sting of the cold was nothing compared to the relentless burn of hunger. Three days, they had been walking now. Three days with barely any food, only what a resourceful few had thought to carry. His mother rested a gentle hand on his shoulder. “Just a bit further,” she said softly. “We’re almost there now.” Jacob wanted to believe her, but how could he when his legs felt like lead and his shoes were torn and he could still hear the screams they had left behind every time it got too quiet?

Becca

Published on February 02, 2018 06:44