Beth Kephart's Blog, page 9

March 15, 2017

EXIT WEST and all the stories that have lately revived my hope

Mohsin Hamid's new novel, Exit West, holds the whole of our world on its blue (star-specked) palm. The story of hard-fisted regimes and near apocalypse, escapees and plundered landscapes, dark doors and possibilities, Exit West is the story, too, of People as illuminated by two particular people: the young lovers Nadia and Saeed. They meet at a time of crumbling infrastructures, raging drones, ID searches, random violence. They take up the journey (through these dark, mysterious, escape-hatch doors) together. They live among other immigrants in foreign lands in subsistence circumstances, and they try (they both do try) to retain the feelings they believe they have for one another throughout the raw rub of it all.

Mohsin Hamid's new novel, Exit West, holds the whole of our world on its blue (star-specked) palm. The story of hard-fisted regimes and near apocalypse, escapees and plundered landscapes, dark doors and possibilities, Exit West is the story, too, of People as illuminated by two particular people: the young lovers Nadia and Saeed. They meet at a time of crumbling infrastructures, raging drones, ID searches, random violence. They take up the journey (through these dark, mysterious, escape-hatch doors) together. They live among other immigrants in foreign lands in subsistence circumstances, and they try (they both do try) to retain the feelings they believe they have for one another throughout the raw rub of it all.Global and intense and palpable, sprinkled with this necessary, never-intrusive magic, Exit West is hard-hitting and heart-hurting, but never, for an instant, cruel.

I will never look at another image of a dislocated refugee and not see Nadia or Saeed or their fellow travelers. I hope every American reads this book, every European, too, and that we all have the same response. That we act on it.

Over and over and over again, Hamid smashes the conundrum of love and life, home and homelessness with long, binary sentences and short words. He writes philosophy into action and within action he posits tenderness. He makes powerful use of the conjunction and the multiple, the crowded and the stop:

That night a rumor spread that over two hundred migrants had been incinerated when the cinema burned down, children and women and men, but especially children, so many children, and whether or not this was true, or any of the other rumors, of a bloodbath in Hyde Park, or in Earl's Court, or near the Shepherd's Bush roundabout, migrants dying in their scores, whatever it was that had happened, something seemed to have happened, for there was a pause, and the soldiers and police officers and volunteers, who had advanced into the outer edges of the ghetto pulled back, and there was no more shooting that night.

Two pages later, returning his focus to the two characters that shoulder his novel, Hamid writes:

Saeed for his part wished he could do something for Nadia, could protect her from what would come, even if he understood, at some level, that to love is to enter into the inevitability of one day not being able to protect what is most valuable to you. He thought she deserved better than this, but he could see no way out, for they had decided not to run, not to play roulette with yet another departure. To flee forever is beyond the capacity of most: at some point even a hunted animal will stop, exhausted, and await its fate, if only for a while.How lucky I have been to spend the last few weeks reading and re-reading books that teach me. Books that have forced me to ask myself what it is I think I am doing with my writing life...and what I should be doing. Paul Lisicky's The Narrow Door (unspool time to find the truth). Dana Spiotta's Innocents and Others (the novel as document, the document as story). George Saunders' Lincoln in the Bardo (be unafraid to do the things that will, inevitably, be questioned). Paulette Jiles's News of the World (make history now, make details crackle). Claire Fuller's Swimming Lessons (there are always many sides to one story). Debbie Levy's Soldier Song (picture books, the best of them, are as smart and as well-researched as anything on the adult table). Vivian Gornick's The Odd Woman and the City (memoir is as much about what you've thought as about what you've done). Amor Towles' A Gentleman in Moscow (nothing wrong, nothing at all, with a good, old-fashioned hero set down inside a good, old-fashioned, finely told story).

Don't despair, my friends. Great art is still among us.

Today I creep back into my own writing life. Edits are arriving on a book due out next summer. Having been emptied and defeated for so long by the news, I am bolstered, ready, hopeful, again, about the power of story.

Published on March 15, 2017 05:35

March 13, 2017

choosing less: my essay in Family Circle (April 2017)

Published on March 13, 2017 09:27

March 9, 2017

George Saunders, Paulette Jiles: excellence prevails (and what it teaches me about writing)

This is spring break week at Penn. My students are off doing their mighty things and I miss them—their questions, their engagement, their enthusiasm, their appreciation for the fine writers they are reading and for the work their classmates present.

This is spring break week at Penn. My students are off doing their mighty things and I miss them—their questions, their engagement, their enthusiasm, their appreciation for the fine writers they are reading and for the work their classmates present."What will you be doing during break?" asked Emily (one of my Emilys), as we were concluding our day with the great memoirist Paul Lisicky. (Words about what Paul taught us, and a video of his fabulous reading, here .)

"I think I might be writing," I said.

And I have. If you can call lifting, bricking, and gluing writing. I have (again) deconstructed and reconstructed a novel that has plagued and delighted me for three long years. Here is proof of how imprecise this writing process is: This particular novel began in first-person past tense, moved to an omniscient third person, was rearranged from flashback intensive to chronologically told, was written again as first person, was then written in a present-tense free indirect, and now, friends, yes: It is a first-person present-tense chronological telling. Wasted time? Not really. With every rendition, with every read, I came to know my characters more. I discovered the dark and light in their hearts.

We writers. We do persist.

But, Emily, beautiful Emily, I'm not just writing during our time apart. I'm reading. The two go hand-in-hand. I'm reading the best of the best because that's how I learn, because we teachers are always teaching ourselves. We're bowing down to those who have done what we imagine we ourselves could never do, and we ask ourselves: How did they do that?

How, for example, did George Saunders write the profound Lincoln in the Bardo? Willie Lincoln has died, President Lincoln has come to the grave to visit, and the ghosts are all astir. Can we call them ghosts? Not really. They are those who have died and who have paused on their way to the next and final stop. They watch the president arrive. They mass together, float together, skim-walk. They have regrets about the ways they lived, about the things they'll never do. They wonder whether it is fair to have been condemned to be the people that they were. Are?

Reading Lincoln in the Bardo is like sitting on a stage in a theater in the round and having the actors perform in the seats around you. Reading Lincoln is like standing in for a hologram. It's bawdy, gorgeous, kind, tender, funny. It is supremely beautiful, pressing in from all sides. It is a story that took Saunders several years to write, yet a story that feels so at ease with itself that a reader can't imagine any struggle at all. Here's a passage, a bit of Bardo conversation by the grave. These characters would like a life do-over. Wouldn't we all?

Did I murder Elmer? the woman said.Goodness, that's fine stuff. It's proof, like the work of Dana Spiotta (whose new Innocents and Others I celebrate here ), that you can write way the heck out of expected forms and still land on the most humane story of all. That's not just a lesson for novelists, my friends. That's a lesson for memoirists. That's a lesson for people in general.

You did, said the Brit.

I did, said the woman. Was I born with just those predispositions and desires that would lead me, after my whole preceding life (during which I had killed exactly no one), to do just that thing? I was. Was that my doing? Was that fair? Did I ask to be born licentious, greedy, slightly misanthropic, and to find Elmer so irritating? I did not. But there I was.

And here you are, said the Brit.

Here I am, quite right, she said.

Now I turn to News of the World by Paulette Jiles, a National Book Award finalist, a worthy one. In a recent Guardian essay, "What Writers Really Do When They Write," Saunders wrote of the power of successive edits, the incremental discovery of a story and its heroes through the act of changing this imprecise word for that better word, for adding this found detail into a sort-of-nothing spot. Jiles, in this fabulous historical novel, offers example upon example of the right word, found:

The girl still didn't move. It takes a lot of strength to sit that still for that long. She sat upright on the bale of Army shirts which were wrapped in burlap, marked in stencil for Fort Belknap. Around her were wooden boxes of enamel washbasins and nails and smoked deer tongues packed in fat, a sewing machine in a crate, fifty-pound sacks of sugar. Her round face was flat in the light of the lamp and without shadows, or softness. She seemed carved.I have more to share. I'm on a roll. I'll soon be reading Amor Towles's A Gentleman in Moscow, and after that some Vivian Gornick and after that Tim Winton, and I won't be done. We can't be done. Not with this.

Reading to write. Reading to live. That's what I'm doing, dear Emily.

Published on March 09, 2017 05:35

March 1, 2017

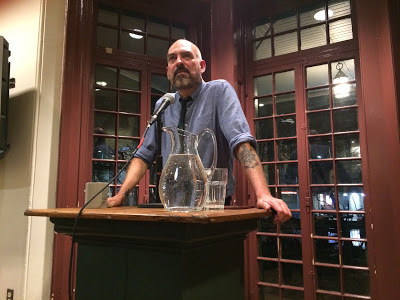

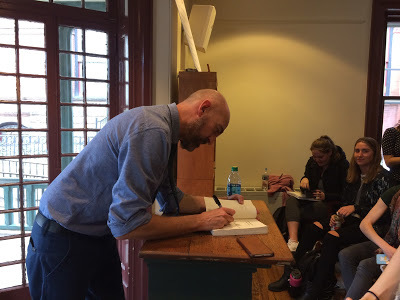

in the language of reconciliation (and how to write a memoir): Paul Lisicky visits Penn

In the course of one week, I've been miraculously uplifted by two writers of annealing generosity and talent. There was Dana Spiotta at Bryn Mawr College last week. There was Paul Lisicky at my own University of Pennsylvania yesterday.

Glimmer. Gleam. Resurgence.

Paul came to speak with our students about his gorgeous memoir The Narrow Door . For more than two hours in the afternoon he stood at that lectern at the Kelly Writers House cafe and answered questions from those (Julia Bloch's students, my students) who had carefully read and wholly embraced his work. He spoke of emotional time, which trumps, in literature, chronology. He suggested the power of staring directly at that thing that you must see...and then turning away, to breathe. He spoke of writing until patterns reveal themselves, about inquiry nudging plot, about learning to work with uncertainty—about learning, indeed, that uncertainty does not necessarily diminish a coherent world view. He spoke of scenes bound together by images, of the responsibility not to replicate memories but to be active with them, to unspool the question; What does that memory have to teach me? Asked about the management and selection of detail, Paul spoke of reverberations, of the need for any chosen detail to deliver far more than the facts.

The Narrow Door, Paul said, is his archive of ongoingness. Writing the book forced him to be attentive at a time of dissolution and personal loss. It was, Paul said, a bit like falling in love again. "It kept me awake and alive at a time when I felt logy."

"You can't expose other people without opening up about yourself," Paul said. "You need self-implication, confrontation, inquiry. You need to ask questions about your own complicity in the story, in the scenes." Readers, Paul reminded us, can only participate in a story if there is no distance, if one has written toward the emotional heat of an experience.

Emotional heat.

Later, as a warm rain fell on a darkening campus, Paul returned to that lectern and read from The Narrow Door, and there it was again: his inarguable talent, his way of seeing, his ushering of us into his spell. Raw and real. That's what it was. That's where beauty and humanity live.

Greatness is community, it is a web. Julia Bloch, who directs our Creative Writing program at Penn so immaculately, said yes at once when I asked if Paul might come to visit us at Penn. Our students invested in his story. Our Penn people (and a dear friend of mine) made the evening come alive by what? By being there. The Kelly Writers House was, as it always is, a gracious host.

My students will soon be off for their spring break. They are driving across the country, singing in Florida, spending a few days in LA, going and being and doing—and thinking about, perhaps even writing some lines of, their own memoirs. Be safe, I say. Pay attention. Expectations and subversions. The world is open to you.

Paul's public reading was recorded. That link is live.

Published on March 01, 2017 04:16

February 26, 2017

Innocents and Others/Dana Spiotta: She'll leave you exhilarated

Long before my son enrolled in Dana Spiotta's undergraduate fiction workshops at Syracuse University, I was a Spiotta fan. No need for proof. I was.

Long before my son enrolled in Dana Spiotta's undergraduate fiction workshops at Syracuse University, I was a Spiotta fan. No need for proof. I was.You can't blame me, though, for confessing that my affection for Spiotta deepened as I learned more about her from my son. She's just really great, he'd say, repeatedly. She just makes stories fun. Saunders was fun. Critiques were fun. Spiotta's workshops were fun. I'd spent much of my motherhood hoping my son would make room for my kind of literature. And there was Dana Spiotta, liberating that kind of love.

Readers of this blog know that, in 2011, I declared Spiotta's Stone Arabia the book of that year, and that by many other estimations, I was right. Those who happened to be at a certain Phillip Lopate reading at Bryn Mawr College last year heard me gasp when Dan Torday (who managed to write this novel while creating and managing this exceptional series) announced that Dana Spiotta would be a Bryn Mawr guest in February 2017.

(Novella artist Cyndi Reeves was there. She heard me gasp.)

Given the history, you'd think I'd have been prepared for the Dana Spiotta I did in fact meet last Wednesday, but I was not remotely prepared. For her easy embrace of near strangers. For her willingness to confide about structure, process, economy, the pursuits of her immense intelligence. For her enormously endearing magic trick of not behaving like the most important person in the room.

Sure, as Spiotta noted during her time at Bryn Mawr, we all curate ourselves, whittle ourselves into the moment. But there's no faking Spiotta's brand of deep-leaning generosity.

Nor is there any denying the almost giddy power of Innocents and Others, Spiotta's newest novel. Recently nominated for the LA Book Prize, Innocents is a profound miracle—a mash up of artifactual nerdiness, filmic obsession, and unforeseen but somehow perfectly logical collisions of characters and ideas. I have no desire to try to describe this book, because the point is: it must be experienced. It must be yielded to on a cold winter day, when it's only you, the couch, the book, and a blanket. Ambition and fabules, listening and seeing, isolation and enduring friendships—you'll find it all here, alongside the arcane and the pop. You'll find riffs (and they don't for one second interfere with the novel's pacing) on rare facts of real life like body listening. This is a section taken from early in the book, from the POV of a woman who calls herself Jelly. Jelly practices the art of phone seduction:

It was when you surrendered to a piece of music or a story. By reclining and closing your eyes, you could respond without tracking your response. You listened. The opposite were the people who started to speak the second someone finished talking or playing or singing. They practically overlapped the person because they were so excited to render their thoughts into speech. They couldn't wait to get their words into it and make it theirs. They couldn't stand the idea of not having a part in it. They spent the whole experience formulating their response, because their response is the only thing they value.Here, later on in the book, are thoughts about being an artist:

It is partly a confidence game. And partly magic. But to make something you also need to be a gleaner. What is a gleaner? Well, it is a nice word for a thief, except you take what no one wants. Not just unusual ideas or things. You look closely at the familiar to discover what everyone else overlooks or ignores or discards.My friend Thomas Devaney was at the reading last Wednesday night. He had Spiotta's novel in his hand, but no words for it. It's just that good. It's just that wise. There's no actual point in talking about it.

Buy it, please, and read.

Published on February 26, 2017 14:04

February 23, 2017

Juncture Notes 12, set for release

In Juncture Notes, our free monthly newsletter, we celebrate classic and contemporary memoirs, the making of the form, memoir prompts, and the work of our readers.

In Juncture Notes, our free monthly newsletter, we celebrate classic and contemporary memoirs, the making of the form, memoir prompts, and the work of our readers.Sign up here .

Published on February 23, 2017 05:28

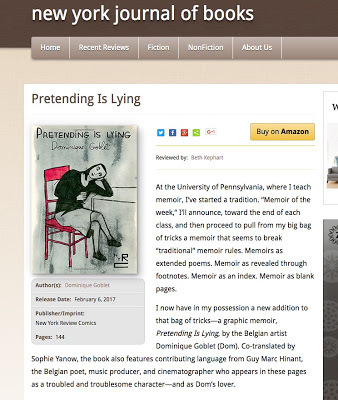

Pretending is Lying/Dominique Goblet: New York Journal of Books Review

My thoughts on a most-interesting new graphic memoir, in today's New York Journal of Books. Full review can be found

here

.

My thoughts on a most-interesting new graphic memoir, in today's New York Journal of Books. Full review can be found

here

.

Published on February 23, 2017 04:21

February 18, 2017

when music and community are our shelter: Musicalia, in the Philadelphia Inquirer

I keep searching for beauty. It is our imperative. To keep finding the best of ourselves, the humanity within ourselves, the tenderness, the good.

I keep searching for beauty. It is our imperative. To keep finding the best of ourselves, the humanity within ourselves, the tenderness, the good.And so I spent a few hours last Friday listening to the Musicalia Ensemble rehearse for its upcoming performance at St. John's Presbyterian Church—a free concert of international folk music, to be held at St. John's in Devon, PA, this Sunday 5 PM. I wrote about Iris, the piano-playing Cuban musician who created this exquisite series, and the Harvey sisters, whose cello and violin further elevate it, and the dedication to song that binds a community in need of a non-rancorous hour.

That story appears in this Sunday's Philadelphia Inquirer.

All are welcome.

Published on February 18, 2017 06:16

February 14, 2017

The Ever-Present Past: E.B. White and Terrence des Pres

[image error]

Today my creative nonfiction students at the University of Pennsylvania shifted my mood, as they do. Their tough-tender souls, their velocity of ideas, their endearing capacity for listening, their well-wrought, thoroughly considered words. Their nouns and verbs outpacing their adjectives and adverbs. Their piano melodies. These young people respect the work and one another; that's transparent. They put their souls into their words; I cheer them on. They do unexpected things elaborately well without ever getting precious in the process.

We're talking about time in memoir this semester. Our conversation today turned to the ways that E.B. White, in his classic "Once More to the Lake," taps eternal weather and landscape to freeze and elongate the past, to windmill the present, to take us (tragically, beautifully) to a time that isn't but (in memory) is.

I promised the students that I would share this essay, which I created for my memoir video series, when I got home. So here I am, home, and here this is, for any of you who are reminiscing today, for any of you in a mood for words.

On Valentine's Day, the gift of memoirEPISODE 6: The Ever-Present Past(excerpted from my memoir video series)

E.B. White, “Once More to the Lake,” Essays of E.B. WhiteTerrence des Pres, “Memory of Boyhood,” Writing into the World

In his beloved essay “Once More to the Lake,” first published in Harper’s magazine in 1941, E.B. White recreates summers once spent as a boy near a lake by returning to the same terrain with his son.

At first the trip is speculation, a question White has about “how time would have marred this unique, this holy spot—the coves and streams, the hills that the sun set behind, the camps and the paths behind the camps.”

But once arrived, White settles in and discovers that the past is sensationally near. The past can be seen, smelled, touched. It is the first morning. White is lying in bed, “smelling the bedroom and hearing the boy sneak quietly out and go off along the shore in a boat.” He begins “to sustain the illusion that he was I, and therefore, by simple transposition, that I was my father.”

It’s a tantalizing thought. A pleasant confusion. And now a vague, lovely timelessness sets in, only sometimes disturbed, say, by a noticeable change in the tracks of a road and the “unfamiliar, nervous sound of the outboard motor.” And yet, White allows the clocks to stand still, the illusion to hold, the dizziness to set in when, as he fishes with his son, he doesn’t “know which rod I was at the end of.”

“Summertime, oh summertime, pattern of life indelible, the fade-proof lake, the woods unshatterable, the pasture with the sweetfern and the juniper forever and ever, summer without end….,” White writes. Persuasively.

But how long can we stop the clocks when we are living? How long can we pretend now is then? How long can we carry the comforting illusions in our head, the gentle perturbations? What brings us back to our own selves, our aging skins? For White it is a thunderstorm—a revival of familiar weather, everything the same about it, at that same lake, boyhood/manhood indivisible—White’s son takes his wet trunks from the line and pulls “around his vitals the small, soggy, icy garment” and it is then, only then, that the years pass quickly in White’s fugue state, when he is reminded that he is a father now, that he is mortal, that time has passed, that time is always passing. As his son buckles the belt, White writes, “suddenly my groin felt the chill of death.”

The illusion has been pleasing. White’s illusion has, over the course of those brief pages, been our own. He has made time stand still by professing persuasive confusion about what time is, about who we are, about age itself, about the tremors of youth. He has made us young again by returning us to a younger version of himself. We have been grateful. And we have been shocked, with him, by a reminder of this: Time does not stop.

In the very final pages of Terrence des Pres’s collection of essays Writing into the World, time is held in the balance once more, but by a very different strategy on the page. Here, in “Memory of Boyhood,” a reflection on des Pres’s fishing days as a child in Missouri first published in Sports Illustrated in 1973, des Pres begins by acknowledging that he is not the boy he once was. “I no longer fish,” he writes, “and the boy who did is twenty years into the past.”

And yet, des Pres says, “memories of that time come constantly to mind. They return to me, or I to them, as if they were my source, a keel of sanity in a world more gnarled and rotted than—at a right-angle bend in the river—the gigantic pile of driftwood and tree trunks we used to call Snake City.”

Boyhood. Summertime. Water. Fish. Des Pres, like White in “Once More,” is recreated, renewed by the primeval. He is washed back into time. He sees, as he travels on, “a boy heading down to the river,” where, “with cane pole and worms” he would catch his fish.

That boy heading down to the river is now a third-person character. He is becoming nearly fictive. He is a dream sustained by memory. He is not des Pres, but he could not exist without des Pres. He is true, because he was. He is false, because he is no more.

We walk with him. Through the haze, toward the banks and fish, to the hours most loved: “He loved best to take his fly rod—a ferruled cane pole to which he’d wired eyes and a reel—and start for the river at dawn. To enter the wet gray stillness of day before sunrise.”

We remain within this ineluctable fiction, this timeless glory, until des Pres snaps his authorial fingers and brings us back to now. “The boy, of course, is myself,” he writes, “a self more vital, compact, pure, like wood within the inmost ring of a tree whose life has reached to many rings.”

The story continues, but now the third person is left behind in favor of first person. We learn more and more about the fishing of des Pres’s youth; the fishing becomes more treacherous, more gory, even brutal. Des Pres remarks on the savagery. He shows it to us. He suggests that “Joy was what counted, the rush of deep delight that came, I think, from rites that for a million years kept men living and in touch with awe.” He ends with this:

“That was the blessing of boyhood. It depended on a way of life now largely vanished and to which in any case I cannot return. Perhaps that is why I no longer fish. Except in memory, a grace that is lost stays lost.”

Des Pres, unlike White, will not return to those Missouri banks. He will see himself through the veil of a third-person telling. He will yearn for the self “more vital, compact, pure, like wood within the inmost ring of a tree.”

White and des Pres, in very different ways, have returned us to childhood. White by physically returning to the site of his boyhood and by creating an elastic envelope of time in which a father is a son, or a son is a father. Des Pres by concentrating his boyhood, by wringing it free of all but the sweet myth, by making himself a known fiction, by preserving the memory by submitting to the possibility that a grace that is lost stays lost. Neither writer pokes holes through the piece with dialogue. Both stay rooted in the primeval—the haze and the sun, the water and the fish.

All of which returns me to you: What are the components of your elemental past? What is your sun and your haze? Do you believe in the elasticity of time? If you were to write of your most primeval self, who would that self be? The third person girl you can just barely see through the neural fog? Or the little boy who sits beside you while you’re listening to me?

Find a quiet place. Grab a keyboard or a pen. Take yourself back to another time and write the elemental you.

Write it in past tense. Write it in present. Write it in first person. Write it in second or third.

Somewhere in there is the story you must tell.

[image error]

[image error]

Today my creative nonfiction students at the University of Pennsylvania shifted my mood, as they do. Their tough-tender souls, their velocity of ideas, their endearing capacity for listening, their well-wrought, thoroughly considered words. Their nouns and verbs outpacing their adjectives and adverbs. Their piano melodies. These young people respect the work and one another; that's transparent. They put their souls into their words; I cheer them on. They do unexpected things elaborately well without ever getting precious in the process.

We're talking about time in memoir this semester. Our conversation today turned to the ways that E.B. White, in his classic "Once More to the Lake," taps eternal weather and landscape to freeze and elongate the past, to windmill the present, to take us (tragically, beautifully) to a time that isn't but (in memory) is.

I promised the students that I would share this essay, which I created for my memoir video series, when I got home. So here I am, home, and here this is, for any of you who are reminiscing today, for any of you in a mood for words.

On Valentine's Day, the gift of memoirEPISODE 6: The Ever-Present Past(excerpted from my memoir video series)

E.B. White, “Once More to the Lake,” Essays of E.B. WhiteTerrence des Pres, “Memory of Boyhood,” Writing into the World

In his beloved essay “Once More to the Lake,” first published in Harper’s magazine in 1941, E.B. White recreates summers once spent as a boy near a lake by returning to the same terrain with his son.

At first the trip is speculation, a question White has about “how time would have marred this unique, this holy spot—the coves and streams, the hills that the sun set behind, the camps and the paths behind the camps.”

But once arrived, White settles in and discovers that the past is sensationally near. The past can be seen, smelled, touched. It is the first morning. White is lying in bed, “smelling the bedroom and hearing the boy sneak quietly out and go off along the shore in a boat.” He begins “to sustain the illusion that he was I, and therefore, by simple transposition, that I was my father.”

It’s a tantalizing thought. A pleasant confusion. And now a vague, lovely timelessness sets in, only sometimes disturbed, say, by a noticeable change in the tracks of a road and the “unfamiliar, nervous sound of the outboard motor.” And yet, White allows the clocks to stand still, the illusion to hold, the dizziness to set in when, as he fishes with his son, he doesn’t “know which rod I was at the end of.”

“Summertime, oh summertime, pattern of life indelible, the fade-proof lake, the woods unshatterable, the pasture with the sweetfern and the juniper forever and ever, summer without end….,” White writes. Persuasively.

But how long can we stop the clocks when we are living? How long can we pretend now is then? How long can we carry the comforting illusions in our head, the gentle perturbations? What brings us back to our own selves, our aging skins? For White it is a thunderstorm—a revival of familiar weather, everything the same about it, at that same lake, boyhood/manhood indivisible—White’s son takes his wet trunks from the line and pulls “around his vitals the small, soggy, icy garment” and it is then, only then, that the years pass quickly in White’s fugue state, when he is reminded that he is a father now, that he is mortal, that time has passed, that time is always passing. As his son buckles the belt, White writes, “suddenly my groin felt the chill of death.”

The illusion has been pleasing. White’s illusion has, over the course of those brief pages, been our own. He has made time stand still by professing persuasive confusion about what time is, about who we are, about age itself, about the tremors of youth. He has made us young again by returning us to a younger version of himself. We have been grateful. And we have been shocked, with him, by a reminder of this: Time does not stop.

In the very final pages of Terrence des Pres’s collection of essays Writing into the World, time is held in the balance once more, but by a very different strategy on the page. Here, in “Memory of Boyhood,” a reflection on des Pres’s fishing days as a child in Missouri first published in Sports Illustrated in 1973, des Pres begins by acknowledging that he is not the boy he once was. “I no longer fish,” he writes, “and the boy who did is twenty years into the past.”

And yet, des Pres says, “memories of that time come constantly to mind. They return to me, or I to them, as if they were my source, a keel of sanity in a world more gnarled and rotted than—at a right-angle bend in the river—the gigantic pile of driftwood and tree trunks we used to call Snake City.”

Boyhood. Summertime. Water. Fish. Des Pres, like White in “Once More,” is recreated, renewed by the primeval. He is washed back into time. He sees, as he travels on, “a boy heading down to the river,” where, “with cane pole and worms” he would catch his fish.

That boy heading down to the river is now a third-person character. He is becoming nearly fictive. He is a dream sustained by memory. He is not des Pres, but he could not exist without des Pres. He is true, because he was. He is false, because he is no more.

We walk with him. Through the haze, toward the banks and fish, to the hours most loved: “He loved best to take his fly rod—a ferruled cane pole to which he’d wired eyes and a reel—and start for the river at dawn. To enter the wet gray stillness of day before sunrise.”

We remain within this ineluctable fiction, this timeless glory, until des Pres snaps his authorial fingers and brings us back to now. “The boy, of course, is myself,” he writes, “a self more vital, compact, pure, like wood within the inmost ring of a tree whose life has reached to many rings.”

The story continues, but now the third person is left behind in favor of first person. We learn more and more about the fishing of des Pres’s youth; the fishing becomes more treacherous, more gory, even brutal. Des Pres remarks on the savagery. He shows it to us. He suggests that “Joy was what counted, the rush of deep delight that came, I think, from rites that for a million years kept men living and in touch with awe.” He ends with this:

“That was the blessing of boyhood. It depended on a way of life now largely vanished and to which in any case I cannot return. Perhaps that is why I no longer fish. Except in memory, a grace that is lost stays lost.”

Des Pres, unlike White, will not return to those Missouri banks. He will see himself through the veil of a third-person telling. He will yearn for the self “more vital, compact, pure, like wood within the inmost ring of a tree.”

White and des Pres, in very different ways, have returned us to childhood. White by physically returning to the site of his boyhood and by creating an elastic envelope of time in which a father is a son, or a son is a father. Des Pres by concentrating his boyhood, by wringing it free of all but the sweet myth, by making himself a known fiction, by preserving the memory by submitting to the possibility that a grace that is lost stays lost. Neither writer pokes holes through the piece with dialogue. Both stay rooted in the primeval—the haze and the sun, the water and the fish.

All of which returns me to you: What are the components of your elemental past? What is your sun and your haze? Do you believe in the elasticity of time? If you were to write of your most primeval self, who would that self be? The third person girl you can just barely see through the neural fog? Or the little boy who sits beside you while you’re listening to me?

Find a quiet place. Grab a keyboard or a pen. Take yourself back to another time and write the elemental you.

Write it in past tense. Write it in present. Write it in first person. Write it in second or third.

Somewhere in there is the story you must tell.

[image error]

[image error]

Published on February 14, 2017 15:11

February 11, 2017

what difference does it make to writers if public figures deny responsibility for their own actions?

At Penn this semester I'm teaching memoir, as I do (until next spring, when I'll be teaching the art of literary middle grade and young adult fiction). But I am also overseeing two adult linked short stories projects, a responsibility that has me working very hard to ensure that I bring more than intuition and experience, preference and instinct to these young writers. It doesn't actually matter that I, years ago, published many short stories or that I publish novels with young protagonists at their heart or that I have reviewed, for papers like the Chicago Tribune, many collections of stories. A deep grounding in the history of critique is also a prerequisite for this teaching job, I think. Readers' guides for well-chosen works. Deep dives into craft books and craft conversations.

At Penn this semester I'm teaching memoir, as I do (until next spring, when I'll be teaching the art of literary middle grade and young adult fiction). But I am also overseeing two adult linked short stories projects, a responsibility that has me working very hard to ensure that I bring more than intuition and experience, preference and instinct to these young writers. It doesn't actually matter that I, years ago, published many short stories or that I publish novels with young protagonists at their heart or that I have reviewed, for papers like the Chicago Tribune, many collections of stories. A deep grounding in the history of critique is also a prerequisite for this teaching job, I think. Readers' guides for well-chosen works. Deep dives into craft books and craft conversations.When we say yes to doing something, anything, we have to commit to doing it fully. And so, I read, take notes, suggest, and ponder.

This week while reading Charles Baxter's immaculate Burning Down the House: Essays on Fiction, I came across these words:

What difference does it make to writers of stories if public figures are denying their responsibility for their own actions? So what if they are, in effect, refusing to tell their own stories accurately? So what if the President of the United States is making himself out to be, of all things, a victim? Well, to make an obvious point, they create a climate in which social narratives are designed to be deliberately incoherent and misleading. Such narratives humiliate the act of storytelling. You can argue that only a coherent narrative can manage to explain public events, and you can reconstruct a story if someone says, "I made a mistake," or We did that." You can't reconstruct a story—you can't even know what the story is—if everybody is saying, "Mistakes were made." Who made them? Everybody made them and no one did, and it's history anyway, so let's forget about it. Every story is a history, however, and when there is no comprehensible story, there is no history. The past, under these circumstances, becomes an unreadable mess.Incredible words, right? Written as if they erupted just yesterday, but they did not. Burning Down the House was first published in the 1990s, and Baxter begins this chapter, called "Dysfunctional Narratives," by talking about Richard M. Nixon.

What am I saying? Why I am putting this here? Because I suspect that the exhaustion so many of us are feeling right now is at least partially bound up with our sense of extreme confusion regarding the narrative we are watching unfold. How do we keep pace with it, untangle it, read it, learn from it, responsibly act on it, and keep moving in our own daily lives? How, especially, if so much of what is happening now rocks us with its strange familiarity (to use another concept Baxter later explores)? But weren't we here, already, once? Are we repeating our past?

Writers have responsibilities. As parents. As partners. As friends. As teachers. As assemblers and testers of narratives. As entertainers. As chroniclers of human (non-partisan, non-polarizing, finally binding) beauty. We are called upon to pay ever closer attention, and fatigue sets in.

And then we pick up a book by a writer like Charles Baxter. We think about what we will teach and how we will write. How we will carry the wisdom forward and on.

We carry forward, too, by the grace and goodness of friends. That work of art, that EXPLORE, in my office window there, in the photo here, was the gift of a Juncture memoir writer named Tracey Yokas. It has sat here, Tracey, right here, where I daily see it, since the moment I brought it home.

A sign of goodness. An unconfused narrative. Explore. Keep going. We can do this.

Published on February 11, 2017 08:10