Beth Kephart's Blog, page 30

December 29, 2015

new year, new hair, with thanks to Rebecca

Published on December 29, 2015 08:42

On stoppering the storm while reading One More Day (Kelly Simmons)

For months it has been raining in my kitchen. Whenever the clouds break, the water comes—through the roof, through the new ceiling, down the columns of new paint. The roofers say they're coming. I wait. I wait. And while I wait, storm by storm, I stand on a stool holding towels to the ceiling. 4 AM. 5 AM. Almost dawn.

For months it has been raining in my kitchen. Whenever the clouds break, the water comes—through the roof, through the new ceiling, down the columns of new paint. The roofers say they're coming. I wait. I wait. And while I wait, storm by storm, I stand on a stool holding towels to the ceiling. 4 AM. 5 AM. Almost dawn.Last night, while I was still in bed, I dreamed that the Beatles came to help hold back the storm. John and Ringo. (Paul was off getting married again and George was—absent.) Wearing white shirts, they sang their songs while they pressed old towels to the ceiling. When I woke at 3:30 they were no longer singing. It was up to me to stopper the storm.

Lucky for me, then, that I had ONE MORE DAY, the third novel by my friend Kelly Simmons, to keep me company. One toweled hand pressed to the ceiling, one hand cradling the book, my bare feet balanced on the old black stool, I read the last 100 pages of this novel from 4 AM to just right now, thinking, as I read, about all the conversations Kelly and I have had (during walks, over non-tea, in her house, in her yard, turning our turn-it-around bracelets on our arms) while this novel was in its stir. News of the first galvanizing surge of idea that sent Kelly to the page. News of the first electrifying email from Kelly's agent. News of the novel's sale to Sourcebooks. News of the story unfolding and again unfolding as Kelly worked through edits and revisions. News of our shared excerpt moment in Main Line Today. Kelly was writing something new to her, taking risks, exploring the idea of the supernatural set against the backdrop of a mother's loss. She was onto something.

When, a few days ago, ONE MORE DAY arrived, courtesy of Lathea Williams, I began reading at once. I am a fan of Kelly's work—her lovely sentences, her twists of humor, her insights into shame and longing. (Read my reviews of STANDING STILL and THE BIRD HOUSE.) ONE MORE DAY, with its limning of relationships and its multiplying secrets, is vintage Kelly with more than a soupcon of the otherworldly strange. A mother's kidnapped child returns for a single day. Ghosts appear—a grandmother, an old boyfriend, a childhood pet. The losses are real, the hurt is real, the secrets are real—but what is poor Carrie, the bereft mother, to think about these visitations? And what is her husband to think? Her mother? The police? The intruding newswoman? The neighbors? Libby, her friend from church? What are any of them supposed to believe, and what are we, the readers, to make of it all?

Whose side are we on?

Where do we come down on faith in things that rise up and then vanish?

I needed to know. I was so eager to find out that I didn't even notice that my suspended, book-cradling arm was shaking until I closed the book. Kelly, my copy is mottled with the unstoppered parts of today's storm. I hope you won't mind. I hope you won't mind, either, if I quote back to you my favorite passage in this book. You're so good at seeing this place we both call home. And you're so good at feeling that apartness that I, too, so often feel. And you're so good at writing sentences that sound just like this:

It was the type of neighborhood that was all proximity; you could turn left or right at any point off the boulevard and find a house that would inspire longing, part of your neighborhood technically, but not part of your world, with a quiet, lumbering grace that marked nobility, remove, other. Carrie was separate from all those people, she knew, and always had been. Not more deserving or less, just different from everyone else.Congratulations, KellyKellyKelly.

Published on December 29, 2015 03:38

December 28, 2015

Fine Writing or Plain Prose? Where do you fall within the Annie Dillard spectrum?

Last night I was all tangled up with Annie Dillard's Living by Fiction, a book that ponders the makings, magic, and meaning (is there any?) of fiction.

Last night I was all tangled up with Annie Dillard's Living by Fiction, a book that ponders the makings, magic, and meaning (is there any?) of fiction.Living by Fiction was published in 1982, while I was still at Penn studying the history of science and too intimidated by capital L literature to take the courses I might have been taking, given the turn my "career" ultimately took.

(Although I have argued, perhaps to appease myself, that my years of studying science and history and biography ultimately helped the novels I'd write. Certainly they shaped my idea of what a novel should or might contain—something larger than plot, something big enough to cradle culture, landscape, and idea, something with a hint of the mesmerized.)

Fiction is about books I have read and also about many books I have not read by authors like Robert Coover, John Hawkes, Rudolph Wurlitzer, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jonathan Baumbach, and Flann O'Brien. It weaves in and out of ideas, whisks readers along, challenges at the same time that it befriends. It is short, but the heart and range of it feels unbounded.

I won't pretend to have received all the heft of Dillard's mind in a single reading. I'm planning on a re-read. But I cherish what I've already picked up along the way, a bevy of fragments that have me thinking about how I read and why I write—and, indeed, how and why I write reviews.

Here, for example, the gauntlet is thrown down:

Fiction writers are, I hope to show, thoughtful interpreters of the world. But instead of producing interpretations—instead of doing research or criticism—they doodle on the walls of the cave. They make art objects which must themselves be interpreted. How convolute, how absurd, how endlessly interesting is this complexity! The world is filling up with works of fiction, with these useless, beautiful objects of thought—to what end? What links any work of fiction with anything we want to learn? To the world we see? To our understanding of the world we see? Does fiction illuminate the great world itself, or only the mind of its human creator?Dillard takes time, in Fiction, to delineate between "fine writing" and "plain prose." These are my favorite pages, the places where I scribbled most energetically in the margins. I have racked up my share of detractors for my interest in complex, unusual language. I have often admired, even envied, the simple and unadorned. I am most assuredly not a fan of the simplistic, which deteriorates all too quickly into dull, trite, overly familiar, crude, or any number of other things. Simplistic doesn't make room for stories, I find. It hammers stories out of imaginistic possibility.

Dillard's own thoughts on all of this had me reading very slow—and wishing I could share the whole with you here. Instead I'll share a few more fragments.

Fine writing, with its elaborated imagery and powerful rhythms, has the beauty of both complexity and grandeur. It also has as its distinction a magnificent power to penetrate. It can penetrate precisely because, and only because, it lays no claim to precision. It is an energy. It sacrifices perfect control to the ambition to mean.... Fine writing is not a mirror, not a window, not a document, not a surgical tool. It is an artifact and an achievement; it is at once an exploratory craft and the planet it attains; it is a testimony to the possibility of the beauty and penetration of written language.Fine writing lays no claim to precision. It is an energy. Beth Kephart, are you listening?

After teaching us how fine writing sometimes gets done, Dillard moves on to plain prose.

The prose is, above all, clean. It is sparing in its use of adjectives and adverbs; it avoids relative clauses and fancy punctuation; it forswears exotic lexicons and attention-getting verbs; it eschews splendid metaphors and cultured allusions.... There is nothing relaxed about the pace of this prose; it is as restricted and taut as the pace of lyric poetry. The short sentences of plain prose have a good deal of blank space around them, as lines of lyric poetry do, and even as the abrupt utterances of Beckett characters do. They erupt against a backdrop of silence. These sentences are—in an extreme form of plain writing—objects themselves, objects which invite inspection and which flaunt their simplicity.

Plain prose erupts against a backdrop of silence. Beth Kephart, is that not enticing?

Published on December 28, 2015 15:02

This Is the Story of You: Teacher Guide

Jaime Wong of Chronicle Books works tirelessly on the teacher guides for author books, and I learn so much from her when I read them.

Jaime Wong of Chronicle Books works tirelessly on the teacher guides for author books, and I learn so much from her when I read them.She's just shared this one with me.

(Link)

I'm grateful for her curious mind, and her reach.

Published on December 28, 2015 14:01

December 27, 2015

Through NEGROLAND Margo Jefferson elevates the memoir form, and leaves me grateful, again

It was Margo Jefferson, the great cultural critic, who first put my name in the New York Times. In a review of another's book, in a closing paragraph, she made mention of something I'd penned in solitude and put forward with innocence and didn't even understand as well as she seemed to.

It was Margo Jefferson, the great cultural critic, who first put my name in the New York Times. In a review of another's book, in a closing paragraph, she made mention of something I'd penned in solitude and put forward with innocence and didn't even understand as well as she seemed to.She looked up and saw me, and I, discovering her snatch of words quite by accident, never felt such gratitude.

When I read earlier this year that Margo had written a memoir called Negroland, I wanted it at once, bought it when I could, and put it on the top of a pile called (in my mind), "the books you'll be allowed to read once you have completed your tour of duty with all known responsibilities."

Yesterday I was done with all known (until next week) responsibilities. I picked up Negroland. I read.

And oh my, oh now: this. Like H is for Hawk, like M Train , like My Life as a Foreign Country, Negroland is the kind of book that elevates not just its readers but the capital M Memoir itself. It's personal—and otherwise. It's I, You, We. It's inquiry, declaration, admission, confusion—the story of the impossible ideals, hurtful expectations, pleasant privileges, and chaotic undertows that have been all bound up with being a member of the black elite. It's a book by an esteemed critic who was "taught to distinguish (her)self through presentation, not declaration, to excel through deeds and manners, not showing off" and who then (but always judiciously, always for a higher purpose) allows us in.

In a book of anecdote, history, cultural expose, and yearning, we encounter, on almost every page paragraphs as searing as this:

Privilege is provisional. Privilege can be denied, withheld, offered grudgingly, and summarily withdrawn. Entitlement is impervious to the kinds of verbs that modify privilege. Our people had to work, scrape for privilege, gobble it down when those who would snatch it away weren't looking.And this:

Being an Other, in America, teaches you to imagine what can't imagine you. That's your first education. Then comes the second. Call it your social and intellectual change. The world outside you gets reconfigured, and inside too. Patterns deviate and fracture. Hierarchies disperse. Now you can imagine yourself as central. It feels grand. But don't stop there. Let that self extend into other narratives and truths.This year, when my beautiful son goes into bookstores he goes straight (his mother's child) to the memoir shelves. He, like me, views memoir as one of the best chances we have of broadening our vision, breaking down our walls, stepping out of our recklessly limited world view.

I have been taught by Margo Jefferson with her gorgeous Negroland. I have seen a little further. I have hurt a little more. I have been made grateful for both the seeing and the hurting.

Published on December 27, 2015 08:17

December 23, 2015

perfectly incomplete: on BEING WRONG (Kathryn Schulz)

Every single day we get something wrong. We assume, we misinterpret, we misconstrue, we fail to hear, we post deliberate, blatant untruths somewhere within the forest of the internet, we (conversely, with no intent to harm) confuse our facts, we accuse, we attack, we (in our desire to defend ourselves) polish and sharpen our narrow rationales. We leave others scrambling for cover.

Every single day we get something wrong. We assume, we misinterpret, we misconstrue, we fail to hear, we post deliberate, blatant untruths somewhere within the forest of the internet, we (conversely, with no intent to harm) confuse our facts, we accuse, we attack, we (in our desire to defend ourselves) polish and sharpen our narrow rationales. We leave others scrambling for cover.Welcome to Humanity.

In Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error (Ecco), Kathryn Schulz, a daring and intelligent writer, tackles wrongness. Where it comes from. How it is institutionalized (and broken). How our response to it defines us. Fear it, she says, and we lose our ability to learn and grown. Accept it, even embrace it, and we live more intellectually elegant lives.

Nested with the history of science, democracies, philosophy, adventures in love and transformation, Shakespeare and Proust, Being Wrong is an exquisite book. It is, in fact, a page turner; I read its 300-plus pages over the course of a single day and one early morning. I read for the ideas and the anecdotes. I read for the prose, which cradles clarity, nuance, and intrigue with seeming ease.

And I read for selfish reasons. I read because, from time to time, a reader will write to me about something I have written—words like an arrow slung.

Once, in an essay, I infuriated a reader by describing Philadelphia as having a European glow in October (I was a rich, Main Line soccer mother of many apparently snooty children, she declared, in her comment—the only part of the accusation that is in fact true is that I live in a tiny two-bedroom house not far from the Main Line tracks. Perhaps Philadelphia does not have a European glow.)

Once, in an 800-word story about the present-day culture and ambiance of Bethlehem, PA, and our ideas of home, I upset a reader for not mentioning the name of one of her husband's distant relatives who figured in Bethlehem's history—her displeasure communicated to me through both an Op/Ed letter and in person, when she found me at a bookstore.

Once I deeply angered a reader for mentioning one cemetery and not both cemeteries along a pedestrian trail, and indeed I might have mentioned both, and I was sorry that I hadn't. It was an oversight, a wrongness glimpsed in hindsight—and learned from.

And once I surprised a reader by mentioning her husband (who had passed away) and my search (along South Street) for his last name. My conversations with those who remembered this artist had led me to conclude that his name was Bud Franklin. Indeed, as I later learned, his name was (Bud) Franklin Drake. The artist's widow had called to let me know the truth. Our phone conversation led to email conversations led to a gift led to a friendship—a story I later told here.

The history of us, Schulz teaches, is the history of error. Of assumptions sliding beneath the weight of new assumptions. Of rigid ideals yielding to debated possibilities. Of "fact" becoming footnote. No one wants to make mistakes (I am so very mad at me when I make mistakes, just ask my poor editors), and yet all of us do. But there is hope, Schulz suggests, for those who choose to grow through errors, to let down their guard, to speak in the measured maybe as opposed to the caustic, self-righteous declaration, to make room for an apology, as Ruth made room for my apology.

... whatever damage can arise from erring pales in comparison to the damage that arises from our fear, dislike, and denial of erring. This fear acts of a kind of omnipurpose coagulant, hardening heart and mind, chilling our relationships with other people, and cooling our curiosity about the world.

Published on December 23, 2015 06:21

December 21, 2015

hopes for peace. our holiday card

Published on December 21, 2015 11:55

talking LOVE on iHeart radio, with Loraine Ballard Morrill

With thanks to Loraine Ballard Morrill, who has done so very much for this city, in so many ways.

With thanks to Loraine Ballard Morrill, who has done so very much for this city, in so many ways.The link is here.

Published on December 21, 2015 07:27

December 20, 2015

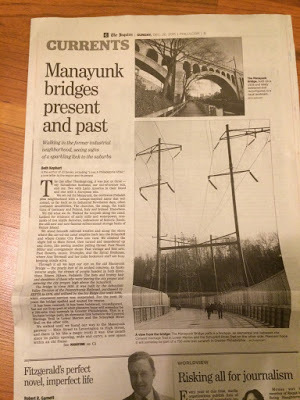

pondering bridges and a shared sky, in Manayunk (today's Philadelphia Inquirer)

I close my year with the Philadelphia Inquirer with this story about an old railroad bridge that has been converted into a walking/biking trail that connects the city and the suburbs, the past and the present, and, indeed, all of us—no matter where we come from, no matter what languages we prefer to speak, no matter which heritages we are celebrating.

I close my year with the Philadelphia Inquirer with this story about an old railroad bridge that has been converted into a walking/biking trail that connects the city and the suburbs, the past and the present, and, indeed, all of us—no matter where we come from, no matter what languages we prefer to speak, no matter which heritages we are celebrating.With thanks to Kevin Ferris, for allowing me to explore ideas—and to hope out loud.

A link to the full story is here.

Published on December 20, 2015 03:58

December 19, 2015

sneak previewing THIS IS THE STORY OF YOU

Chronicle has posted the early pages of This Is the Story of You, my Jersey Shore storm story due out in April—and I'm happy to share them here.

Chronicle has posted the early pages of This Is the Story of You, my Jersey Shore storm story due out in April—and I'm happy to share them here.The link.

For more on the book—the blurbs, the news—please go here.

Published on December 19, 2015 04:21