Beth Tabler's Blog, page 212

November 10, 2021

Review – The Valkyrie of Vanaheim by Phil Parker

check it out here

check it out here BOOK REVIEW

THE VALKYRIE OF VANAHEIM by PHIL PARKER November 10, 2021 11:02 am No Comments Facebook Twitter WordPress WHAT IT IS ABOUT?Frida Ransom has a secret, she is a human/Fae hybrid. A lonely one too. Frida and her mother lived a solitary existence to keep that secret safe. Her mother’s unexpected death, and a decade-long war with the fae, turned the girl even more emotionally fragile.

Now, with the war over, humanity and the Fae must cooperate to overcome new challenges. Except factions on both sides of the inter-dimensional portals oppose this collaboration. A new dimension has been found, one humanity could colonise.

A mission to reconnoitre this new world takes shape and Frida finds herself included on the team. Her problems deepen when factions of humanity and fae try to sabotage the mission. A sequence of events shines a spotlight on Frida and her family heritage. For this eighteen-year-old young woman, its attention threatens her sanity and places her in danger.

Beyond the spotlight, waiting in the darkness of their destination, something malevolent and cunning awaits. It needs Frida to fulfil its plans. Which, if successful, threatens the existence of humanity and the Fae.

For fans of a wonderful blend of non-stop action, meshed with skillful character development, I strongly recommend checking out the thrilling portal fantasy, ‘The Valkyrie of Vanaheim” by Phil Parker!

The book is set in a not-so-distant dystopian future, filled with prejudice, mistrust, and misunderstanding between Fae and human-kind. Humans live in one dimension, while Fae live in another, however the two species can enter one another’s space, and other dimensions as well.

The protagonist, a teenager named Frida, is part-human, part-Fae. This mixed heritage would make both sides – human and Fae – suspicious of Frida, therefore her true lineage is hidden. Frida’s deceased mother elected to pass her daughter off as human only, in order to protect Frida from scorn, ridicule, or worse.

The humans and the Fae have been at war for years, however a fragile peace has been forged. Still, there are forces on both sides that disapprove of the detente, and actively conspire to ruin the treaty. Meanwhile, other dimensions that are suitable for habitation, unexplored by humans or fae, have been discovered. A collaborative mission is formed to investigate the new universe, but danger and disaster await those who attempt the journey.

Frida has grown up somewhat isolated, a bit socially awkward, and feeling out of place in the world. She longs for deeper friendships, companionship and a romantic relationship. In Frida’s mind, she is not considered as feminine and as attractive to men as other women. Perceiving herself as unattractive, along with the secret bloodline factor, Frida feels despondent that she will not be able to forge deeper connections. But Frida does not wallow in self-pity. She is very brave, intelligent, capable, and a very morally upright and strong person of values.

Frida finds herself part of the military mission to survey the new dimension. The dimensions of the world in Parker’s story are inspired by Norse Legend, and the new dimension is called Vanaheim, home of the Vanir Gods in Norse mythology. The mission will need Frida’s burgeoning powers, to combat the evil that lurks in Vanaheim, and that evil intends to use Frida for its own pernicious purposes.

As I noted at the onset of this review, there is action aplenty in this book, with some heart-stopping battles, blending modern weaponry, advanced technology, and ancient magic. Lovers of a fast-paced plot will not be disappointed in this book. Parker keeps the tension on, and the reader praying their favourite players can survive the constant, epic conflict!

Again, I admire Parker’s ability to incorporate depth of character – particularly with his main character, Frida – side by side with the blurring fight scenes. The reader will acutely feel Frida’s angst, moral quandaries, hope, disappointments, rage, sorrow, and the gamut of her emotions. She is very well-drawn and believable.

The secondary characters are quite interesting as well, and I loved the twists Parker threw in with their plot arcs that the reader likely won’t see coming! I also enjoyed the diverse creatures in the book, and I don’t want to spoil it by giving away most of them, however, I’ll just say something akin to a fire-breather may make more than one unforgettable appearance!

I LOVED the themes touched on in the book. Present thought-provoking ideas in a novel and you will definitely receive my praise and admiration. The misgivings among different human and Fae factions is very well done by Parker, and portrayed with dexterously and with appropriate realism.

There are plenty of shades of grey / ambiguity among some of the characters and their motivations (outside of the downright evil ones) and there is a lot of grappling with questions about what is right and wrong, and if others who are different can be trusted and accepted. There is also the debate over colonialism, and what gives another group the right to simply take over another territory, for their own purposes, which is a theme that will always intrigue me.

A very good book, “The Valkyrie of Vanaheim” was a fun ride, with strong characterization and compelling themes! I will sure be looping back to read any sequels, and also checking out Parker’s “Knight’s Protocol” trilogy, as “The Valkyrie of Vanaheim” has converted me into a Phil Parker fan!

Check Out some of our other reviewsReview – The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix

Review – A Head Full Of Ghosts by Paul Tremblay

P.L. Stuart

I’m an experienced writer, in that I’ve been writing stories all my life, yet never thought to publish them. I’ve written informally – short stories – to entertain friends and family, for community newspapers, volunteer organization magazines, and of course formal papers for University. Now, later in life, I’ve published what I believe is a great fantasy novel, and definitely worth reading, called A Drowned Kingdom. My target audience is those who enjoy “high fantasy”. A Drowned Kingdom is not “dark fantasy”. It’s written in a more idealized and grandiose style that I hope isn’t too preachy, and not too grim. Still, I’m hoping my book has appeal to those who don’t typically read this type of work – those who don’t read fantasy of any kind – because of the “every-person” themes permeating the novel: dysfunctional familial relationships, extramarital temptation, racism, misogyny, catastrophic loss, religion, crisis of faith, elitism, self-confidence, PTSD, and more.

Many of these themes I have either personal experience with, or have friends or family who have dealt with such issues. I’ve had a long professional law enforcement career, undergone traumatic events, yet been buoyed by family, faith, and positivity. I’m a racialized middle-aged man. I’ve seen a lot of life. Ultimately I want the planned series, of which A Drowned Kingdom will be the introduction, to be one of hope, and overcoming obstacles to succeed, which I believe is my story as well. My protagonist, Othrun, will undergo a journey where he’ll evolve, change, and shape a continent. He’s not always likeable. He’s a snob, bigot, is vain, yet struggles with confidence. He’s patriarchal. Overall, he’s flawed. But even ordinary flawed people can change. We’re all redeemable.

Ordinary people can make a difference, not just fictional Princes. I want that message to shine through my work.

WHERE TO FIND HIMTwitter – @plstuartwrites

Facebook – @plstuartwrites

If You Liked This - Please Share the LoveShort Story – Ozioma the Wicked by Nnedi Okorafor

Beth Tabler 5/5

Beth Tabler 5/5  Unnatural Creatures by Neil Gaiman Purchase Here

Unnatural Creatures by Neil Gaiman Purchase Here Nnedi Okorafor, Ozioma The Wicked AboutTO MOST, OZIOMA WAS A NASTY LITTLE GIRL whose pure heart had turned black two years ago, not long after her father’s death. Only her mother would dis- agree, but her mother was a mere fourth wife to a dead yam farmer. So no one cared what her mother thought.―

“I was there when NNEDI OKORAFOR won the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel for Who Fears Death, and cheered as loudly as anyone. She’s a wonderful writer who makes her home in Chicago and has the best hair in the world. Twelve years old, and able to speak with poisonous snakes, Ozioma’s the undefeated champion of her village—despite the fact that everyone in it thinks she’s a witch. One day, though, a tremendous serpent descends from the heav- ens, and tests even Ozioma’s courage…..”

My Thoughts Ozioma the Wicked is a short story written by writer Nnedi Okorafor. It appears as the the fourth short story in the collection Unnatural Creatures. I chose to review each of the stories separately due to the stories found in the collection being so different. The stories have come from different eras. Some were written by fantasy writers, hard science fiction, comedy writers and even satirists. Ozioma is no different. Ozioma is about a young girl who can talk to snakes. Or, rather a young Nigerian girl who can communicate with snakes or sense what their intentions are. This isn’t Harry Potter though.

My Thoughts Ozioma the Wicked is a short story written by writer Nnedi Okorafor. It appears as the the fourth short story in the collection Unnatural Creatures. I chose to review each of the stories separately due to the stories found in the collection being so different. The stories have come from different eras. Some were written by fantasy writers, hard science fiction, comedy writers and even satirists. Ozioma is no different. Ozioma is about a young girl who can talk to snakes. Or, rather a young Nigerian girl who can communicate with snakes or sense what their intentions are. This isn’t Harry Potter though. Afam stopped, out of breath. “There,” he said, pointing. Then he quickly backedaway and ran off, hiding behind the nearest house and peeking around its corner.Ozioma turned back to the tree just as it began to rain.Shaped like two spiders, a large one perched upside down upon a smallerother, the thick smooth branches and roots were ideal for sitting. On days of rest,the men gathered around it to argue, converse, drink, smoke, and play cards on different branch levels.I believe that the picture that Okorafor paints is a much truer picture of how a small town or community would handle a girl like her. They ostracize her. They belittle her. They call her a witch. Ozioma is a a model of courage in the face of hard circumstances, in the face of mob mentality, and in the face of fear this little girl shines. It is a great story and at this point I would expect nothing less from Okorafor. But, if you get an opportunity to check out this short story by itself, I think it is 30 pages or so, or read Unnatural Creatures in its totality please do. Ozioma The Wicked It is worth the read. If you like this , Check Out Her Other Work

Review of Hello Moto by Nnedi Okorafor

Knowledge Comes at a Steep Price in Nnedi Okorafor’s Biniti

If You Liked This - Please Share the Love Where to find it? ProcurementI checked this out from the library

About the Author

Nnedi Okorafor is a Nigerian American author of African-based science fiction, fantasy and magical realism for both children and adults and a professor at the University at Buffalo, New York. Her works include Who Fears Death, the Binti novella trilogy, the Book of Phoenix, the Akata books and Lagoon. She is the winner of Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards and her debut novel Zahrah the Windseeker won the prestigious Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature. She lives with her daughter Anyaugo and family in Illinois. Learn more about Nnedi at Nnedi.com.

Beth Tabler

Elizabeth Tabler runs Beforewegoblog and is constantly immersed in fantasy stories. She was at one time an architect but divides her time now between her family in Portland, Oregon, and as many book worlds as she can get her hands on. She is also a huge fan of Self Published fantasy and is on Team Qwillery as a judge for SPFBO5. You will find her with a coffee in one hand and her iPad in the other. Find her on: Goodreads / Instagram / Pinterest / Twitter

November 9, 2021

Review – Yellow Jessamine by Caitlin Starling

check it out here

check it out here BOOK REVIEW

YELLOW JESSAMINE by CAITLIN STARLING November 9, 2021 10:00 am No Comments Facebook Twitter WordPressYellow Jessamine by Caitlin Starling started incredibly strong with great atmospheric detail and a very creepy vibe but puttered out and ended with a whimper.

Evelyn Perdanu is a shipping magnate, the only living survivor of her family. She walks the city veiled and hidden away from the eyes of those around her. Her country is slowly dying, rotting away like food left out to spoil. Arriving from her last voyage out, she discovers that a plague has visited her city, and it is traced back to her crew. They act erratically and slip into catatonia. She begins to investigate the plague as much for the city’s sake and those in it as for her own company and family name. What she finds is complicated and horrific.

Also highly confusing to me as a reader.

This story started beautifully. It was atmospheric and enchanting. We learn little bits of the background of Evelyn’s life; we know a bit about the relationship she has with her assistant. We realize that Evelyn is a master herbalist, and she has used her herbal concoctions all over town, both for good and evil. This fantastic backstory for Evelyn gave me a solid foundation to picture her character in my mind.

This all takes place in the first act of the story.

When we start the second act, additional ideas and characters are added to the mix; the police captain, for instance. It gets confusing, and I was not sure of the importance of things. Should I, as a reader, be concerned by the Police Captain sniffing around? Or with the plague? Or with Evelyn’s business interests?

By the third act, the story gets a bit stranger and still more confusing, and it just ends. I don’t want to give it away, as the ending is very out of the left field.

Conceptually, this is a remarkable book. Starling absolutely knows how to work words into magic in the mind of the reader. During the story’s first half, my mind’s eye was covered in yellow smoke, twisted and thorny vines, and a woman sitting amongst it all veiled in black lace. It lost me in the second and by the third act, I was so confused by some things that I was just done. The atmospheric description and excellent detailing were constant, though, and that is why I finished the story.

Check Out some of our other reviewsReview – The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix

Review – Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

Short Story Review – If You Take My Meaning by Charlie Jane Anders

Beth Tabler

Elizabeth Tabler runs Beforewegoblog and is constantly immersed in fantasy stories. She was at one time an architect but divides her time now between her family in Portland, Oregon, and as many book worlds as she can get her hands on. She is also a huge fan of Self Published fantasy and is on Team Qwillery as a judge for SPFBO5. You will find her with a coffee in one hand and her iPad in the other. Find her on: Goodreads / Instagram / Pinterest / Twitter

November 8, 2021

Interview with Zoje Stage, Author of Baby Teeth and Getaway

ZOJE STAGE "...I find it much harder to write a world that’s grounded in reality. With Getaway in particular I tried to adhere to the specific geography of the trails and places I named in the Grand Canyon. This necessitated conforming my plot elements to what was physically possible given the terrain....."

ZOJE STAGE "...I find it much harder to write a world that’s grounded in reality. With Getaway in particular I tried to adhere to the specific geography of the trails and places I named in the Grand Canyon. This necessitated conforming my plot elements to what was physically possible given the terrain....." Pittsburg native and former filmmaker Zoje Stage is a USA Today and international bestselling author of Baby Teeth, Wonderland and now her newest release Getaway. A story where two sisters, Imogen and Beck, and a long-time friend Tilda are hiking in the majestic Grand Canyon’s backcountry. “But as the terrain grows tougher, tensions from their shared past bubble up. And when supplies begin to disappear, it becomes clear secrets aren’t the only thing they’re being stalked by.”

Zoje was kind enough to interview with Grimdark Magazine about her penchant for horror and suspense, writing, and Getaway.

[BWG] What kind of stories inspired you to become a writer? And if it wasn’t a story, what was your journey here?

[ZS] For decades my dream was to be a writer/director of independent films. At the time, I believed that film was the medium that encompassed all of my interests: writing, photography, theatre, etc. Unfortunately, due to finances and health issues, I never achieved in film what I’d hope to do. At the end of 2012 I made the difficult decision to leave my film aspirations behind and see if I could learn to write novels. The kinds of books I write are very similar to the types of movies I wanted to make, with stories that delve into interesting facets of human behavior amid a situation or setting where something weird is going on—naturally or supernaturally. A lot of my creative motivation is in exploring how people react to the strangeness going on around them.

[BWG]

You have heavy film and screenplay experience. How does your background affect how you craft scenes for novels? Do you approach them visually? Do you storyboard? What is your process?

[BWG]

You have heavy film and screenplay experience. How does your background affect how you craft scenes for novels? Do you approach them visually? Do you storyboard? What is your process?

[ZS] I still think quite visually, and often an idea for a novel will start with an image or two. It was very challenging when I first switched from filmmaking to writing novels as I had to learn how to create an image entirely with words, while understanding that everyone imagines things differently. It helped that long before I was a filmmaker I wrote poetry, so I had some experience with using language expressively. Now I rather enjoy the challenge of figuring out how to translate the mood, setting, imagery that I see in my head using only the precision of sentences.

[BWG] Your first two novels, Baby Teeth, and Wonderland have supernatural elements to them? Do you find it easier to write a world where the world’s rules are changeable i.e., ones with supernatural elements or ones grounded entirely in reality?

[BWG] Your first two novels, Baby Teeth, and Wonderland have supernatural elements to them? Do you find it easier to write a world where the world’s rules are changeable i.e., ones with supernatural elements or ones grounded entirely in reality?

[ZS] I find it much harder to write a world that’s grounded in reality. With Getaway in particular I tried to adhere to the specific geography of the trails and places I named in the Grand Canyon. This necessitated conforming my plot elements to what was physically possible given the terrain. Sometimes it’s a constructive challenge to have certain kinds of restrictions—it can help you stay focused. But I really love the freedom of letting my imagination run wild, which is likely why I’ve always been attracted to writing genres like horror and fantasy.

[BWG] Your stories have various horror aspects, whether psychological, supernatural, or suspense. Do you read horror novels? And if so, what scares you?

[ZS] I’d say my greater passion is for the various ways that suspense resides in a novel, and I read more thrillers and psychological stories than straight horror. I definitely like my horror to “ring true” (no matter how fantastic it may seem): I like to see characters realistically grappling with their situation. I’m pretty hard to scare, and when a book scares me it’s usually moments of off-kilter creepiness.

[BWG] Do you find writing a therapeutic outlet?

[ZS] I’ve maintained for a long time that writing is how I process the world. I swear sometimes I don’t know what I truly feel or think about something until I have a chance to sit down and write about it.

[BWG] Having released two novels amidst the pandemic, Wonderland released in 2020 and now Getaway in 2021, how has the experience of releasing differed as an author from that of Baby Teeth in 2018?

[ZS] Releasing books during a pandemic has been very difficult, on multiple fronts. There’s the business aspect: people are not necessarily as plugged into things like new book releases as they once might have been, and are concerned about their finances in a changing world. With Baby Teeth I was just getting the hang of making public appearances as an author…and then it all came to an end. Virtual events are wonderful in certain ways, but I often end up feeling quite disconnected. In many ways it feels like Wonderland, especially, was released into a black hole. My sense of these books being “published” doesn’t feel completely real, although this time around I’ve gotten to see Getaway in a number of bookstores (always a thrill!).

[BWG] Has the pandemic had any effect on your ability to be creative?

[BWG] Has the pandemic had any effect on your ability to be creative?

[ZS] It’s been a very strange year and a half, to say the least. Like many people, my ability to concentrate was impaired for quite a while and I was more inclined to write short pieces—poetry, essays, short stories. I am back to work now, though I still experience bouts of existential malaise. Everything seems very uncertain, which makes it hard to feel grounded and in a solid, safe place. Writing is always the thing that keeps me sane, but it takes a bit more willpower now.

[BWG] In an interview from a few years ago, you mentioned in jest that people won’t know who someone is as a writer until their third book. You went on to say, Baby Teeth has a very internal story with tight relationships. Wonderland has a very strong external element, but your third book has very tight relationships within an external environment. This brings me to the question about your third, recently released book, Getaway. Can you tell me a bit about it?

[ZS] Getaway is about a trio of thirty-something women (two of them sisters) who have been friends since high school. Over the years life and distance have pulled them in different directions and their bonds with each other are fraying. Worse, our hero Imogen has experienced some life traumas that make it increasingly hard for her to function well in the world. Her sister devises a Grand Canyon backpacking trip in an effort to help the three of them get re-connected, and hopes the magnificent environment will help Imogen heal. But soon into their adventure they meet someone very unfortunate, and their vacation goes awry.

On the surface, Getaway looks like an adventure thriller, but I think it’s equally a tale of psychological suspense. The characters find themselves in a situation that tests every ounce of their physical and moral resolve and because Imogen perceives herself as small and weak, her survival strategy becomes more internal and psychological.

[BWG] I read your inspiration for a Getaway was a camping experience with your family as a child. Can you elaborate on that?

[ZS] Getaway, indeed, has its origins in an odd encounter I had with my family on a backpacking trip in the Grand Canyon. We were in a remote area called Salt, where one party at a time was permitted to camp. I was in my teens, and in my emotionally-colored memory of it a haggard fellow appeared out of nowhere, wearing a pistol in a hip holster.

My dad and sister remembered it more accurately: he wasn’t carrying a gun, but he did mention that he’d recently gotten out of prison and was just “wandering around.” He also remarked that, upon crossing paths with a lone female ranger, he realized he could’ve picked up a rock and bashed her in the head and no one would ever know.

Needless to say the incident at Salt stuck with me through the years, as it marked the first time that being in nature carried a hint of human danger. After that, I was always more paranoid, especially when it was just me and my sister camping somewhere deserted, off-season. In my family’s story, the man walked on. Getaway explores the “what if” of a trio of backpackers who aren’t so lucky.

[BWG] Getaway doesn’t fit into any category or genre. There are elements of relationship discussion and familial strife, dealing with psychological turmoil, psychological suspense, survival, and even horror. Do you think that genre labeling is helpful for authors or a hindrance?

[ZS] For better or worse, I don’t think about genre when I write. While I endeavor to write dark and suspenseful books, more specific labels feel very restrictive to me. Labels exist primarily for marketing reasons—who is the audience, where is the book going to be shelved—but I think it affects how some readers approach a book. For instance, some readers have biases toward certain genres and won’t read things that are labeled in categories they believe they don’t like. On the flip side, some readers have extremely specific ideas about what a label like “horror” should mean, and if a book doesn’t conform to that they may be disappointed. For both of these reasons I always wince a little when my books are labeled, but I guess “dark and suspenseful” isn’t an official genre.

[BWG] In the prologue of Getaway, we meet Imogen and her experience with a shooting that happened in a Jewish Synagogue in Pittsburgh. Many of the feelings that Imogen experiences, “What could I have done?” and survivor’s guilt, is felt by victims of traumatic experiences. Imogen’s experiences wrang with authenticity. Did you do any specific research into this particular type of PTSD?

[ZS] I have experienced a very different sort of trauma than Imogen’s but because of my own experience it was important to me to create a character who was complex and relatable. As part of my own effort to understand trauma it was very helpful to read Waking the Tiger by Peter A. Levine. I do truly believe that as sensitive beings in a violent and uncertain world most—if not all—of us are living with trauma, even if we don’t realize it. I believe society itself is a product of trauma, and the more we damage our world and each other the more prevalent trauma becomes.

[BWG] I know that you are from Pittsburgh, specifically the Squirrel Hill neighborhood that had a similar shooting at the Tree of Life congregation in 2018. Is your connection to this area the source of inspiration for this prologue?

[BWG] I know that you are from Pittsburgh, specifically the Squirrel Hill neighborhood that had a similar shooting at the Tree of Life congregation in 2018. Is your connection to this area the source of inspiration for this prologue?

[ZS] It is. The Tree of Life shooting took place just blocks from my then-apartment. It was a very shocking and frightening morning, made even more memorable by having a Baby Teeth event to go to, which I’d considered canceling (but didn’t). I felt the repercussions of that incident in my neighborhood for months and months afterward. There were reminders in every storefront window: posters of the names of everyone who’d been killed; Stars of David dangling from every tree and parking meter. It was both poignant and hard to see all the time.

[BWG] The locations and scenes in Getaway play a more significant role than just as a space that characters move through, often seen in novels. They almost seem like they are characters themselves. Was that intentional? Or, was that how the writing evolved because you described something that had to be incredibly difficult to explain?

[ZS] The setting of everything I write is an integral part of my books. Baby Teeth would feel completely different if Suzette didn’t obsessively clean her already perfect prison of a house. Wonderland needs not just the isolation of the family’s new Adirondacks home, but the beauty and danger that manifests in extremely wintry conditions. Getaway picks up on those wilderness themes—beauty and danger—but in the context of being so deep in the Grand Canyon’s desert backcountry that the characters can’t consider any survival strategies beyond their own wit. The place they’d come for a back-to-nature vacation becomes hostile territory, almost an inescapable fortress. I think by necessity—and by its inherent awesome presence—the Grand Canyon feels very “alive” in this book, and even when the characters feel trapped and afraid they’re never unaware of the beauty around them.

[BWG] Can you tell us a bit about the other characters in the novel? We meet Imogen in the prologue, but who are the other characters who will share this journey with Imogen?

[ZS] Imogen’s life has made her somewhat paranoid and cautious, but she has a rich imagination—which Beck and Tilda think she relies on too much. Beck, Imogen’s older sister, lives a stable life with her equally successful wife. Imogen would describe her sister’s need to “fix everyone” as annoying, but it’s probably why Beck became a physician. Their friend Tilda was always a bit of a showwoman, so her life path took her from doing high school musicals to auditioning for American Idol. She’s made a career as a motivational speaker and influencer. At one point while writing Getaway I realized I’d chosen career paths for my three women where they were each basically their own boss. There is another character…but for the sake of avoiding spoilers I will let readers discover that on their own.

[BWG] Familial relationships are significant in Getaway, both born of blood and those relationships that happen when a friend becomes lifelong family. Do you think the mental growth and mending these characters had at the end of the story could have been achieved had the trip gone on without a hitch?

[ZS] Absolutely not. If everything had gone according to plan, perhaps Imogen and Tilda would have developed some new respect for each other—and then they would’ve gone right back to their old ways. I’ve thought a lot over the years about the impact of difficult situations—how soldiers bond on the battlefield. It can be true even for less traumatic circumstances, such as an arduous backpacking trip that goes according to plan. But part of what we do as novelists is put our characters through the worst things they can endure, to test their inner resolve in the hopes of learning something vital about themselves. Part of the magic of a book is that evolution can be experienced in condensed time, whereas in real life we’re learning and changing over a span of years.

[BWG] To hearken back to a previous question about getting to know a writer through their books? What is on the horizon for you? What can you say about your next novel?

[ZS] I believe come 2022 readers will get to see my first published novella, called (at least for now) The Girl Who Outgrew the World. As a dark yet whimsical fairy tale it’s a little “off brand” for me, but it is dear to my heart. It’s about an eleven-year-old girl, Lilly, who has an inexplicable growth spurt. When her father and doctors decide to take drastic action to curb her dangerous growth, Lilly runs away—and embarks on a journey to discover her true self. In the spirit of fairy tales, the story works on two levels and TGWOTW is also a parable for how patriarchy reacts to and treats, the female body.

I’ve also recently finished a new novel, but it’s at a delicate stage at the moment so I can’t say too much about it except that it’s an adult mother/daughter story, very psychological, a little batshit crazy.

[BWG] Are you reading something exciting right now? I had heard that you loved Survivor Song by Paul Tremblay. I, too, cried when I read it as well as Cabin at the End of the World. They are gut-punches of novels.

[ZS] I love both of those novels! I’ve read some great books this year—Cackle by Rachel Harrison, Don’t Look For Me by Wendy Walker, Dark Things I Adore by Katie Lattari, Rovers by Richard Lange. At the top of my reading pile right now are These Toxic Things by Rachel Howzell Hall, and The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward.

Interview Originally Appeared in Grimdark Magazine

Check out zoje stage's books

Check Out Some Of Our Other interviews

Check Out Some Of Our Other interviews Interview – Kristyn Merbeth Author of the Nova Vita Protocol

Interview – Author Grady Hendrix

November 7, 2021

Review – Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

check it out here

check it out here BOOK REVIEW

NINTH HOUSE by LEIGH BARGUGO November 7, 2021 10:00 am No Comments Facebook Twitter WordPress What is it About?Galaxy “Alex” Stern is the most unlikely member of Yale’s freshman class. Raised in the Los Angeles hinterlands by a hippie mom, Alex dropped out of school early and into a world of shady drug dealer boyfriends, dead-end jobs, and much, much worse. By age twenty, in fact, she is the sole survivor of a horrific, unsolved multiple homicide. Some might say she’s thrown her life away. But at her hospital bed, Alex is offered a second chance: to attend one of the world’s most elite universities on a full ride. What’s the catch, and why her?

Still searching for answers to this herself, Alex arrives in New Haven tasked by her mysterious benefactors with monitoring the activities of Yale’s secret societies. These eight windowless “tombs” are well-known to be haunts of the future rich and powerful, from high-ranking politicos to Wall Street and Hollywood’s biggest players. But their occult activities are revealed to be more sinister and more extraordinary than any paranoid imagination might conceive.

Bardugo, of course, nominally needs no introduction. But in case those reading this review are not familiar with her work, she is a #1 New York Times bestselling author of numerous YA fantasy novels. Bardugo is probably best known for the Six of Crows Duology.

“Ninth House” is a deviation from Bardugo’s normal genre, into adult fantasy-horror. I have to say, I was not entirely sold on the book at certain junctures, but overall, the sum was much greater than the parts, and it truly grew on me, emerging as an amazing book.

The book’s protagonist, Galaxy “Alex” Stern, has a troubled past. Brought up in Los Angeles by a mother immersed in counterculture, Alex is a high-school dropout, who has run with the wrong crowd for the better part of her life.

Hanging out with undesirables, and steeped in the illicit drug world, Alex life is listless and even dangerous, due to her association with drug dealers and that ilk. Horrifically, Alex ends up almost the victim of murder, while some of those she knows are not so fortunate.

Recuperating from the incident that was nearly fatal for her, Alex obtains mysterious sponsors, who offer her a chance, despite her lack of academic success, to attend uber-prestigious Yale University, fully paid via the sponsors. She does not know why, after her tumultuous upbringing, and having barely escaped death, she has been given a chance to join an exclusive Ivy League school. But she, naturally, seizes the opportunity.

Alex quickly learns, as one might expect, nothing in life, especially admission to an institution as distinguished as Yale, is free. Due to her benefactors, she is soon drawn into the shadowy world of Lethe House.

Lethe House is the ninth of Yale’s clandestine societies – hence the eponymous “Ninth House” – and one that appears to be closely linked to the occult. All of the university’s secretive societies are populated with very wealthy, very influential, and very sinister people. But Alex soon learns, due to her own untapped abilities, she is not as out of place in Ninth House as she first thought she might have been.

What at first did not appeal to me, frankly, were two aspects. The main character, Alex, was seemingly somewhat ambivalent and dispassionate, despite all she undergoes, the way she was drawn by Bardugo.

I have no issues whatsoever with flawed or unlikable characters at all, and it was not that I did not like Alex, or that she was written to be unlikable. It was that Alex was hard to decipher as a character, initially. Of course, this is my opinion, and I considered early in the book that her somewhat dispassionate perspective was a result of trauma, and her other challenges.

As the book went on, for me it seemed that Alex evolved, and was much more engaged in her own story. The secondary characters are very well-done, and since most of them are villainous, or at least ambiguous in their morality, it makes for a very compelling book.

Second issue for me: I had heard raves about Bardugo’s prose, though I had read none of her work myself previously. The book was well written, but perhaps my own lofty expectations got the better of me. There were definitely some gems of passages, but I thought it would be more consistent throughout.

The plot is more slow burn, and this is just my jam, but I think the languorous pace may be the one thing that might be off-putting for some readers. Bardugo takes her time in setting all the pieces in place. The novel commences with a future scene. Then, multiple timelines are woven together, but eventually collide, with shocking results. But, just to emphasize this point, as some other reviews I have read point out a significant concern with the pacing, the major events are often dispersed in lethargic fashion throughout the book, except for certain points. Those craving faster pacing may abandon ship, unwilling to wait for those big occurrences.

For me, it was very much worth the payoff. I felt there was plenty of action, especially scary and shocking scenes, for readers to sink their teeth into. Murder, disappearances, and more abound, and Alex is sucked even deeper into the bizarre and perilous world of Ninth House. Things take on a mystical, and terrifying element, as black magic, haunting spirits, blended with corruption, dark secrets, and the impetus to protect the privileged at all costs from facing the consequences of their actions, become pervasive in the narrative.

What turned this book into a five-star from a four star, which is what I originally rated it, was the engrossing themes. Bardugo’s exploration of serious and troubling topics such as sexual assault and what consent means, feminism, classism, elitism and privilege, racism, and more, were fascinating, and handled with appropriate skill and sensitivity.

Reference the aforementioned, fair warning regarding the above as potential triggers. Moreover, there is plenty of violence and gore in the book, so readers beware if this is not something you want to digest.

This is the first book in a series, and I think it’s a series that is worth reading. The book presents a lot of realism, and plausible conflict. It has a great dose of the fantastical, is very imaginative, and has some truly mesmerizing moments. Along with the powerful themes, Ninth House has done more than enough for me to be looking forward with anticipation to the next book in the “Alex Stern” story. Check Out some of our other reviews

Review – The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix

Review – Survivor Song by Paul Tremblay

Review – A Spindle Splintered by Alix E. Harrow

P.L. Stuart

I’m an experienced writer, in that I’ve been writing stories all my life, yet never thought to publish them. I’ve written informally – short stories – to entertain friends and family, for community newspapers, volunteer organization magazines, and of course formal papers for University. Now, later in life, I’ve published what I believe is a great fantasy novel, and definitely worth reading, called A Drowned Kingdom. My target audience is those who enjoy “high fantasy”. A Drowned Kingdom is not “dark fantasy”. It’s written in a more idealized and grandiose style that I hope isn’t too preachy, and not too grim. Still, I’m hoping my book has appeal to those who don’t typically read this type of work – those who don’t read fantasy of any kind – because of the “every-person” themes permeating the novel: dysfunctional familial relationships, extramarital temptation, racism, misogyny, catastrophic loss, religion, crisis of faith, elitism, self-confidence, PTSD, and more.

Many of these themes I have either personal experience with, or have friends or family who have dealt with such issues. I’ve had a long professional law enforcement career, undergone traumatic events, yet been buoyed by family, faith, and positivity. I’m a racialized middle-aged man. I’ve seen a lot of life. Ultimately I want the planned series, of which A Drowned Kingdom will be the introduction, to be one of hope, and overcoming obstacles to succeed, which I believe is my story as well. My protagonist, Othrun, will undergo a journey where he’ll evolve, change, and shape a continent. He’s not always likeable. He’s a snob, bigot, is vain, yet struggles with confidence. He’s patriarchal. Overall, he’s flawed. But even ordinary flawed people can change. We’re all redeemable.

Ordinary people can make a difference, not just fictional Princes. I want that message to shine through my work.

WHERE TO FIND HIMTwitter – @plstuartwrites

Facebook – @plstuartwrites

If You Liked This - Please Share the LoveNovember 6, 2021

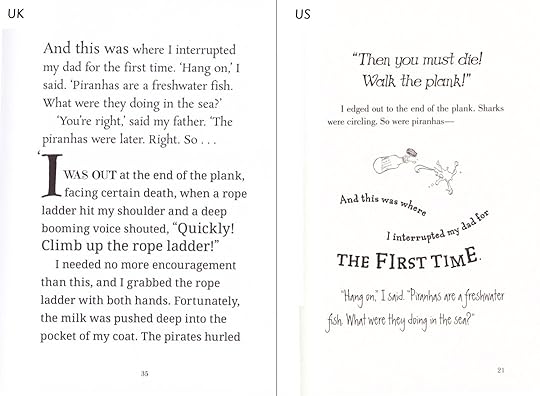

Short Story – Fortunately, the Milk by Neil Gaiman, Skottie Young

Beth Tabler

Beth Tabler

Fortunately, The Milk by Neil Gaiman Purchase Here

Neil Gaiman, Fortunately, The Milk AboutSpoons are excellent. Sort of like forks, only not as stabby.―

“I bought the milk,” said my father. “I walked out of the corner shop, and heard a noise like this: t h u m m t h u m m. I looked up and saw a huge silver disc hovering in the air above Marshall Road.”

“Hullo,” I said to myself. “That’s not something you see every day. And then something odd happened.”

Find out just how odd things get in this hilarious New York Timesbestselling story of time travel and breakfast cereal, expertly told by Newbery Medalist and bestselling author Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Skottie Young

“If the same object from two different times touches itself, one of two things will happen. Either the Universe will cease to exist. Or three remarkable dwarfs will dance through the streets with flowerpots on their heads.”

DON’T FORGET TO GET THE MILK.

Neil Gaiman is a man of whimsical and prodigious talents. He is a massive neutron star in the science fiction/fantasy/graphic novel realm. And, rightly so. He has amassed close to 2 million followers on twitter and not because of just his name. He connects with his fans and seems to generally appreciate them. Not only that, he is an authors “author.” Many authors look up to him and emulate his style. People love him and his work.

If you haven’t connected with his middle-grade stories you really should. Coraline and the Graveyard Book are precise and whimsical story telling with an edge of scary and unnerving. Not enough to be inappropriate, but enough to show kids of that age bracket that not all is sunshine and rainbows in the world. He treats kids like they have a brain, thoughts and emotions and ideas worth challenging. It is smart writing through and through.

Even when he puts random ideas in a bucket and pulls them out one at a time, he can seamlessly craft an entertaining and memorable story. Thus enters Fortunately, The Milk. The premise is simple, it is the story of what happened to dad when he went to the corner store to get milk, and why he was late. In the vein of Paul Bunyan, it is a true tall tale.

Or is it?

Examples of creatures and other awesome things found in this book:

Time traveling dinosaursHot Air BalloonsSentient VolcanoPiratesPiranhasAliensMilkThis story is the absurd, the fantastical, the amazing, and is quite possibly real.

“I mean, what if this really happened to dad?”

“He was gone a very long time.”

“Dad is an incredible guy, it could happen?”

That is the point of this story, the “what if?” Absurdly fun to read for both adults and kids. Don’t miss it.

Also, as a small side note on the illustrations. If you look in the background at the pictures on the wall, and other details you can see where dad is getting his tale from. A la The Usual Suspects.

Check Out Neil's Other WorksShort Story – Sunbird by Neil Gaiman

If You Liked This - Please Share the Love Where to find it? Procurement I Listened to this on Scribd and checked it out from the library. About the Author

I listened to this on Scribd, with Gaiman doing the narration. It is worth it just to listen to him read it. However after listening to it I went and found the wonderful illustrations.

Beth Tabler

Elizabeth Tabler runs Beforewegoblog and is constantly immersed in fantasy stories. She was at one time an architect but divides her time now between her family in Portland, Oregon, and as many book worlds as she can get her hands on. She is also a huge fan of Self Published fantasy and is on Team Qwillery as a judge for SPFBO5. You will find her with a coffee in one hand and her iPad in the other. Find her on: Goodreads / Instagram / Pinterest / Twitter

November 5, 2021

Short Story Review – If You Take My Meaning by Charlie Jane Anders

check it out here

check it out here BOOK REVIEW

IF YOU TAKE MY MEANING found in Even Greater mistakes by charlie jane anders November 5, 2021 11:00 pm No Comments Facebook Twitter WordPress Short Story List As Good As NewRat Catcher’s YellowIf You Take my MeaningThe Time Travel ClubSix Months, Three DaysLove Might Be Too Strong a WordFairy Werewolf vs. Vampire ZombieGhost ChampagneMy Breath is a RudderPower CoupleRock Manning Goes For BrokeBecause Change Was The Ocean and We Lived by Her MercyCaptain Roger in HeavenCloverThis is Why We Can’t Have Nasty ThingsA Temporary Embarrassment in SpacetimeThe Bookstore At The End of AmericaThe Visitmothers IF YOU TAKE MY MEANING illustrated by Robert Hunt

illustrated by Robert Hunt  WHAT IT IS ABOUT?

WHAT IT IS ABOUT? As an ex-smuggler and two-time reluctant revolutionary, Alyssa is used to staring into the razor-sharp jaws of death. But now she’s embarking on the most terrifying adventure of her life—journeying into the darkness to become a new type of being, one who can help humanity to survive. And deep at the heart of the city in the middle of the night, the price of transformation could be higher, and more terrible, than Alyssa ever expected.

REVIEWIf You Take My Meaning is a difficult story to come in to and get the full meaning of unless you have read Anders’s The City in the Middle of the Night. It is still a unique and enjoyable story, but I can see it being a bit confusing for some readers due to Anders jumps right into the story and doesn’t give a huge amount of info on why things are the way they are. But, because I have read The City in the Middle of the Night, I understand the gravity of the actions of the characters.

The premise is of an ex-smuggler and revolutionary Alyssa, and her becoming a new species. A new type of thing. But things get a bit wobbly.

Alyssa and Jeremy want to be more like Sophie. You learn about Sophie in the The City In The Middle of the Night, “Sophie, a young student from the wrong side of Xiosphant city, is exiled into the dark after being part of a failed revolution. But she survives–with the help of a mysterious savior from beneath the ice. Burdened with a dangerous, painful secret, Sophie and her ragtag group of exiles face the ultimate challenge–and they are running out of time.” They feel that getting implanted with the alien tendrils will allow a much greater connection to Sophie. They each have the procedure and have different reactions to it. Extreme pain, as Alyssa in a pique of revulsion, tries to rip them from her body. Jeremy feels his grafts will expand his ability to be an activist.

The two of them have an epiphany about the Gelent and the role humanity plays. They shift their perspectives and understand that they are becoming a new thing.

This is a difficult story to understand. It is hard to know what is going on. However, it is connected to the heart of the characters much like any Ander’s short stories. You feel a connection to what the characters are going through and because the story operates as a sequel lovers of The City in the Middle of the Night get a little more information on the characters’ lives.

Check Out some of our other reviews

Review – The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix

55 Books With LGBTQIAP+ Representation to Add to Your TBR

Beth Tabler

Elizabeth Tabler runs Beforewegoblog and is constantly immersed in fantasy stories. She was at one time an architect but divides her time now between her family in Portland, Oregon, and as many book worlds as she can get her hands on. She is also a huge fan of Self Published fantasy and is on Team Qwillery as a judge for SPFBO5. You will find her with a coffee in one hand and her iPad in the other. Find her on: Goodreads / Instagram / Pinterest / Twitter

Hopepunk, Optimism, Purity, and Futures of Hard Work by Ada Palmer

Ada Palmer "The punk movement is anti-establishment, with long ties to political activism and resistance, anti-consumerist, anti-corporate, anti-authoritarian, with a strong ethic of visibility and in-your-face active expression of these sentiments."

Ada Palmer "The punk movement is anti-establishment, with long ties to political activism and resistance, anti-consumerist, anti-corporate, anti-authoritarian, with a strong ethic of visibility and in-your-face active expression of these sentiments." I’m tired. You’re tired too.

Right now, we’re all more tired than most people have been in our entire lives—studies show this, both studies of our mid-pandemic world and older studies of the neurological effects of trauma and emergencies, the subtle, cumulative damage to brain and body that comes from waking day after day for months on end to find the world still turned up-side-down by crises (hurricane, flood, fire, coup). This affects our sleep, concentration, memory, reading, energy levels; no one in our interconnected Earth is operating at anywhere near 100% right now, and yet the crises—political, global, and personal—still loom. This is why today, even more than when Alexandra Rowland coined the term hopepunk in 2017, stories like Ruthanna  Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden or Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway, the kinds of tales where futuristic cyberhippies hunt through the refuse piles of consumerism for the upcyclable materials to build their green new worlds, both match and merit the countercultural and protest-associated label punk. It’s also why such tales are—and have long been—as rare as they are needed.

Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden or Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway, the kinds of tales where futuristic cyberhippies hunt through the refuse piles of consumerism for the upcyclable materials to build their green new worlds, both match and merit the countercultural and protest-associated label punk. It’s also why such tales are—and have long been—as rare as they are needed.

Let’s talk about the term first, then the tiredness, then why we need more stories that don’t end with everything burning down.

Rowland coined hopepunk in July 2017 as the “opposite of grimdark.” Associated terms such as noblebright, solarpunk, greenpunk, or ecotopia join hopepunk to sketch out a body of imagined worlds which are positive but not utopias, because their positivity lies, not in the world already being excellent, but in the world moving toward the better thanks to the efforts of excellent people who work to make a difference. It is a subgenre tied to resistance: as Rowland put it punk = “fight the man” + hope = “we deserve a better world”. Hopepunk stories tend to showcase cooperation, collective action, resilience, partial victories as the world is moved toward, not to, a better state, ending with (re)construction underway and the world changing, not changed. The subgenre has also been described as weaponized optimism, and as rising from a culture of resistance, specifically anti-authoritarian resistance which swelled around the globe in the wake of 2016, connected with what Malka Older has called speculative resistance, the use of fictional worlds to encourage resistance by showing alternatives to the systems we have now (see podcast discussion). In fact, the term hopepunk as first conceived was so linked to 2016 that, when the 2019 Dublin WorldCon held a wonderful panel on hopepunk where Rowland was joined by Jo Walton, Lettie Prell, and Sam Hawke, they had a rich discussion of whether my Terra Ignota series qualified as hopepunk given that it was written much earlier but released in fall 2016, a very informative question I shall return to after a bit why this term coined as an antonym is useful far beyond analyzing grimdark.

One general signature of hopepunk is that its stories counter tales of emotional darkness or rottenness, not just grimdark with its characteristically violent, amoral, and often dystopian/apocalyptic trappings, but also stories whose settings may be less recognizably grimdark but whose plots and character choices either advance zero-sum narratives where achievement requires causing someone else’s fall, or portraits of human nature in which, in the end, people will always be selfish, backstab, let you down, or look out for number one, and in which systems will always be corrupt and unsalvageable. In Hopepunk, people—often ordinary people, including minor characters—take a stand, resist, work together, follow through and help each other, and in the end, while some characters make bad choices, enough make good choices to leave a positive sense of the capacity of humans to choose good. Put another way, hopepunk presents an image of human beings where, in a prisoner’s dilemma situation, not everyone but enough people actually do choose the thing that helps everyone to make it possible to make the world a better place. So many stories teach us that, when crisis hits the fan, it won’t take long for biker gangs bedecked with human skulls to rampage through the devastated streets, and very few depict how studies show people really behave in crisis, banding together to supply pop-up pantries and mutual aid. In that sense, while hopepunk, at its  inception, mainly included contemporary fantasy and near-future SF, Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor represents it very well, a story where good people treating each other fairly within a political system succeed in improving their world and triumphing over corrupt backstabbers through the power of the rational fact that most people would rather work with people who treat us well and have our backs than with corrupt selfish backstabbers. Amid so many tales of murder games and cutthroat games of thrones, there is a genuinely punk-like in-your-face contrariness to stories where, when crisis looms, people stand by each other and do good, a portrait of human nature which rebels against the ubiquity of the claim that, when the going gets tough, the smart trust no one.

inception, mainly included contemporary fantasy and near-future SF, Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor represents it very well, a story where good people treating each other fairly within a political system succeed in improving their world and triumphing over corrupt backstabbers through the power of the rational fact that most people would rather work with people who treat us well and have our backs than with corrupt selfish backstabbers. Amid so many tales of murder games and cutthroat games of thrones, there is a genuinely punk-like in-your-face contrariness to stories where, when crisis looms, people stand by each other and do good, a portrait of human nature which rebels against the ubiquity of the claim that, when the going gets tough, the smart trust no one.

Before it sounds like hopepunk could describe any story where friendship triumphs, or good guys beat bad guys, these are not stories where a heroic champion or pure-hearted plucky team rise to defeat evil. Remember how often the wholesome hero(ine)’s goal is to defend or restore the status quo, whether a recent status quo (you burned my village!) or one lost years ago before the evil empire deployed its evil plans. The punk movement is anti-establishment, with long ties to political activism and resistance, anti-consumerist, anti-corporate, anti-authoritarian, with a strong ethic of visibility and in-your-face active expression of these sentiments. Punk is also messy. While the grimdark hero, forged by a traumatic backstory and strewing trails of corpses through the sunless waste, is one opposite of the Disney Princess, hopepunk is another opposite. The Disney Princess and many hero stories are purity stories. Think of the messiah-hero who passes uncorrupted through temptations, Sir Lancelot whose invincible perfection is ended by the taint of his lust, Frodo who struggles to resist the ring and takes its aftereffects home with him like a scar, and the classic B horror movie where the girl who has sex is killed by the monster while the virgin survives. Performers who play Disney Princesses for Disney branded children’s party services are warned on penalty of termination to never let audiences see them frown, seem unhappy, express anger, or even sweat.

Punk is grungy in aesthetic, and hopepunk shares that, building better among the garbage of the bad. It also expresses negative emotions, not despair but productive anger, as well as kindness which sometimes needs to take the form of confrontation, or calling someone out. Hopepunk showcases resilience by showing failure, setbacks, and compromise, not as heroic flaws or formative backstories, but acknowledging that messing up is an unavoidable part of taking action in the first place. After all, another opposite of both the grimdark hero and the flawless Disney Princess is Barak Obama in February 2019 stepping before the cameras and saying “I’m here on television saying I screwed up. And that’s part of the – your responsibility is not never making mistakes, it’s owning up to them and trying to make sure you don’t repeat them.” Most grimdark heroes make mistakes, but they are giant character-defining mistakes, leaving the person dark and grim, reinforcing the idea that any failure or impurity is a big deal, not a normal part of living a reasonable life.

Messiness and impurity paired with positive change are one core way hopepunk differs, not only from grimdark or heroic F&SF, but from a huge body of narratives, and even political logics. As articulated by philosopher/sociologist Alexis  Shotwell in her brilliant book Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times, ideas of purity often do harm to action and activism, especially in middle class white America with its Puritan cultural roots. Anxiety about impurity, Shotwell argues, increases white fragility, causing fierce emotional resistance when accepting criticism requires acknowledging impurity. Purity is also used (often strategically) to make ethical choices more difficult, variations on the argument that while company X burned thousands of acres of rainforest, company Y doesn’t 100% reject the use of GM foods, so they’re also impure and you may as well shop with company X. I recently discussed this problem with the head of my local CSA farm co-op: CSAs support buying local, but studies show that if they offer a few items from faraway farms that can’t grow in an area (for me in Chicago this means avocadoes and citrus) local food sales go up as a result, because when people need to go to a grocery store for their avocadoes they are tempted by the convenience to pick up other things (eggs, milk) they would otherwise buy from the co-op—the CSA head wanted to do this, but knew that, if he did, many of his old hard-core supporters would then boycott and attack the co-op for selling out, for not being purely local, even if the result was strictly better for both farmers and climate. Shotwell discusses the impossibility of true purity—practically no foods or products exist that don’t harm something—and the importance of acknowledging harm done in order to be able to evaluate levels of harm, reduction of harm, etc. Purity is especially weaponized against progressive politicians and grassroots movements, opponents harping on one flaw in a candidate, using that to argue that supporting that candidate is a form of impurity or selling out, a very important concept to the punk movement. While concerns over hypocrisy are important, and we must defend against them with tools like Ulysses pacts, opponents of change have learned that, much like greenwashing or the myth of individual responsibility, they can strategically deploy purity language and the accusation of selling out to undermine resistance groups and leaders.

Shotwell in her brilliant book Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times, ideas of purity often do harm to action and activism, especially in middle class white America with its Puritan cultural roots. Anxiety about impurity, Shotwell argues, increases white fragility, causing fierce emotional resistance when accepting criticism requires acknowledging impurity. Purity is also used (often strategically) to make ethical choices more difficult, variations on the argument that while company X burned thousands of acres of rainforest, company Y doesn’t 100% reject the use of GM foods, so they’re also impure and you may as well shop with company X. I recently discussed this problem with the head of my local CSA farm co-op: CSAs support buying local, but studies show that if they offer a few items from faraway farms that can’t grow in an area (for me in Chicago this means avocadoes and citrus) local food sales go up as a result, because when people need to go to a grocery store for their avocadoes they are tempted by the convenience to pick up other things (eggs, milk) they would otherwise buy from the co-op—the CSA head wanted to do this, but knew that, if he did, many of his old hard-core supporters would then boycott and attack the co-op for selling out, for not being purely local, even if the result was strictly better for both farmers and climate. Shotwell discusses the impossibility of true purity—practically no foods or products exist that don’t harm something—and the importance of acknowledging harm done in order to be able to evaluate levels of harm, reduction of harm, etc. Purity is especially weaponized against progressive politicians and grassroots movements, opponents harping on one flaw in a candidate, using that to argue that supporting that candidate is a form of impurity or selling out, a very important concept to the punk movement. While concerns over hypocrisy are important, and we must defend against them with tools like Ulysses pacts, opponents of change have learned that, much like greenwashing or the myth of individual responsibility, they can strategically deploy purity language and the accusation of selling out to undermine resistance groups and leaders.

Hopepunk narratives are genre stories which have depictions of human nature (teamwork, honesty, resilience) but which also counter purity narratives, by having space for partial victories, unfinished projects, compromise, and mundane not-character-defining failures and mistakes. Setbacks in hopepunk tend to be more about the outcome for the world, what now needs to be done to help or fix the problem, in contrast with stories where setbacks or failures are mainly beats in character development, the point where the hero must stand by his vow never to kill again, or prove her leadership skills to keep the team together. And these are stories born, as Rowland puts it, from “a political mood of resistance” where the path is neither Disney perfection, nor breaking and becoming grim and tainted, nor being the pure survivor spared by the horror monster by virtue of your virtue; the path is long, hard, exhausting, ongoing work.

This is why it matters that we’re all so tired.

And this is how it can be true, both that hopepunk was shaped by post-2016 resistance culture, and that it is larger than that, uniting both earlier projects (like my Too Like the Lightning) and later ones, especially in this moment of the dual apocalypses of COVID-19 and the climate crisis.

Recent polls show an increasing number of people are jumping straight from denying climate change to saying they believe climate change is real but that it’s too late and there’s nothing we can do can stop it. It’s the emotionally easiest way out of climate denial. It lets one feel that even if one had believed sooner, the small amount one could have done by now wouldn’t make a difference. It avoids the obligation to take action now, allowing one to continue without any lifestyle change, since it’s too late. It is an easy attitude to mock or be angry at, but I cite it here because it connects to an issue which is even bigger for those who have believed in climate change, and the authoritarian threat, and the dangers of big tech monopolies, and the censorship crisis, and systemic racism, and institutional injustice: we’re tired. Working toward change is exhausting. Continuing to work for change is even more exhausting, as we see in the patterns like the turn-out-the-vote group VoteForward, which in fall 2020 blasted past its goal of sending 15 million volunteer-written letters, but this fall keeps failing to hit targets in the 200,000 range. A lot of people poured their all into the politics and protests of 2020, and are now worn down by the exhaustion-trauma of our up-side-down COVID-19 world, and by seeing day-by-day how very partial a victory those efforts achieved, how small a slice of what needed to change is changing.

Fiction does not give us many stories of continuing to slog on after an unsatisfying partial victory. That makes hopepunk powerful.

Dystopian fiction great at out bad parts of our society, and galvanizing action. So is false-utopia fiction, the kind where the happy affluence enjoyed by some turns out to be founded in something sinister and unforgivable. But recent dystopias and false-utopias tend to end with that cathartic finale where the looming tower of the evil government burns down. That is an emotionally satisfying ending, part of what makes modern dystopian literature a fundamentally optimistic genre, transmitting the message that, even in a world with far worse versions of our problems, revolution can still win. Apocalyptic fiction, which ends with the whole world burning down, is also emotionally satisfying: if not cathartic, at least it is fair (the rich and bad guys also burn), and final; at the end comes rest. All of these tend to avoid what lived political experience shows is the hard part: building the new, better system after the evil tower burns, or the false utopia’s sinister secret is revealed—the part we’re living now. Hopepunk tales of actually building the new thing are a rare form, in part because they aren’t as emotionally satisfying. The 25th century of my Terra Ignota has fixed some of today’s problems but is still working on others, a world build which advances the unwelcome but important thesis that change takes generations, and that all our efforts may achieve neither none nor all of our goals, but some, requiring yet more work. Like Emrys’s titular half-built garden—a new society building amid the effects of climate disaster—these worlds are half-built throughout, their stories rich but emotionally difficult, in a way the Death Star blowing up is not.

Another emotionally satisfying kind of is one where everything is saved by someone special rising to fix it all, a destined savior, or in future SF often a genius who invents the tech-that-saves-everything. As I observed in my half-joking 2013 review of Iron Man 3, Tony Stark not only, as the script jokes, “just successfully privatized world peace,” he also invents an infinite clean energy device, which begins to be deployed instantly and effortlessly, without oil lobbies or congressional obstructionism. This attitude—wait for the techies to save the planet—is functionally identical with the declaration that it’s too late to save the climate, since both prescribe personal inaction. As Cory Doctorow put it in his essay Hope Not Optimism “optimists and pessimists share this belief in the irrelevance of human action to the future. Optimists think that things will get better no matter what they do, pessimists think things will get worse no matter what they do — but they both agree that what they do doesn’t matter… An optimist decides not to equip the Titanic with lifeboats because it is unsinkable. A pessimist doesn’t bother to swim when the ship sinks and is lost at sea. To be hopeful is to tread water because so long as you haven’t gone to the bottom, rescue is still possible.” Both optimism and pessimism—both giving up and leaving the work to others—are tempting when we are all so very, very tired.

Embracing hope not optimism involves recognizing  that progress is not a natural process which somehow grinds on inexorably no matter what we do, progress is our name for the group consequences of our collective actions. Writing about hope not optimism means writing about the hard and ongoing process of building and rebuilding, not just about the evil tower burning down. In Jo Walton’s Thessaly series, a failed effort to set up a Platonic utopia gives way to the survivors learning from those mistakes and setting up new, less-unsuccessful Platonic utopias, not scrapping it all but keeping the good, and building back better. C. L. Polk’s Kingston Cycle in the books that follow the revelations in Witchmark do much the same. Is my Terra Ignota hopepunk, despite the first three books being written before 2016? Yes, not just in themes, but because hopepunk is fiction about the difficult path of rebuilding, and Terra Ignota draws heavily on Enlightenment France, which literally stormed and burnt down the overlord’s fortress, only to face the multi-century process of building a new system on the ashes. Another profoundly hopepunk novel in that sense is Yusuke Kishi’s 2008 From the New World, which has many twists and surprises for the reader, but the one that stunned me most was when the false utopia’s mask was ripped off and the protagonists… committed themselves to working incrementally within the system to bring about peaceful reform. Kishi’s story is pre-2016, like but Japanese F&SF has for some time had a lot more hopepunk-type tales of incremental rebuilding than Anglophone fiction, since Japan both was and is still incrementally rebuilding after the overthrow of a real lived authoritarian dystopia in World War 2. Thus, I would argue that pre-2016 hopepunk does exist, but shares the characteristic of being born from a real culture of antiauthoritarian resistance, and of rebuilding.

that progress is not a natural process which somehow grinds on inexorably no matter what we do, progress is our name for the group consequences of our collective actions. Writing about hope not optimism means writing about the hard and ongoing process of building and rebuilding, not just about the evil tower burning down. In Jo Walton’s Thessaly series, a failed effort to set up a Platonic utopia gives way to the survivors learning from those mistakes and setting up new, less-unsuccessful Platonic utopias, not scrapping it all but keeping the good, and building back better. C. L. Polk’s Kingston Cycle in the books that follow the revelations in Witchmark do much the same. Is my Terra Ignota hopepunk, despite the first three books being written before 2016? Yes, not just in themes, but because hopepunk is fiction about the difficult path of rebuilding, and Terra Ignota draws heavily on Enlightenment France, which literally stormed and burnt down the overlord’s fortress, only to face the multi-century process of building a new system on the ashes. Another profoundly hopepunk novel in that sense is Yusuke Kishi’s 2008 From the New World, which has many twists and surprises for the reader, but the one that stunned me most was when the false utopia’s mask was ripped off and the protagonists… committed themselves to working incrementally within the system to bring about peaceful reform. Kishi’s story is pre-2016, like but Japanese F&SF has for some time had a lot more hopepunk-type tales of incremental rebuilding than Anglophone fiction, since Japan both was and is still incrementally rebuilding after the overthrow of a real lived authoritarian dystopia in World War 2. Thus, I would argue that pre-2016 hopepunk does exist, but shares the characteristic of being born from a real culture of antiauthoritarian resistance, and of rebuilding.

While optimism and pessimism both offer tempting ways out of feeling one must take personal action, Shotwell’s analysis of purity helps expose another such temptation, a third narrative: purity stories where just by remaining pure the protagonist triumphs or survives. All those B horror movies where the virgin lives, or purity of heart expels the demons, the Disney movies where the princess comes through spotless, the moment when the T-Rex eats the bloodsucking lawyer not the hero, or in the disaster movie when the kind protagonist goes back to save the orphan and thus is saved when falling rubble crushes others—these narratives are inheritances of Puritan-influenced providentialist thinking which expects fate to preserve the pure. As we face climate change and COVID-19, the archetype of purity of action offering safety in troubled times offers a strange hybrid between abdicating responsibility and facing responsibility: the idea that by making the right choices to stay personally pure—an end far easier to act on than political reform—one increases one’s chances of salvation, either on the personal scale (the eco-disaster spares your house, the virus spares your family), or on the global scale of feeling that, if enough members of the human race are good at heart, if there are enough good people in the city of Sodom, then God/Fate/Providence/climate change will be more likely to move toward the good ending not the bad ending. For many people, especially in America, the ideological residue of Puritanism and providentialist Christianity means that pursuing personal purity can feel like a way of helping indirectly with crises like climate or authoritarianism when direct action is intimidating or exhausting. Someone who feels guilty doing nothing may feel overwhelmed trying to engage politically, but making grocery store choices that prioritize personal purity feel like taking effective action, because so many narratives tell us that purity makes the optimist ending more likely to come true. There are other varieties of providentialist thinking which let one abdicate a sense of personal responsibility (the new fad for stoicism is one) but pursuing personal purity has the bonus of making it feel like you actually are taking action, while evading the whirlwind of messiness, compromise, and option paralysis involved in choosing among the array of impure political candidates, or the innumerable activist causes competing for our help.

I have written elsewhere about the importance of diversity of narrative structures, that we need not only many kinds of characters but many shapes of stories: heroes and antiheroes, protagonists and teams, kind aliens and scary aliens, false utopias and real utopias, stories where we cure the plague and stories where we accept a lower quality of life. We even need some purity stories since—as Shotwell obesrves—purity is a very useful and positive tool for self-examination and thinking hard about our choices. And we need hopepunk. There is nothing wrong with sitting back sometimes to enjoy blowing up the Death Star—when we’re this tired that’s often what we crave. But because we’re this tired, we also need stories of people who are tired like us. Who are trapped between crises like us. Who are grungy, and sweaty, and compromised, and struggling like us. Who resiliently come together, trusting and supporting one another, as we must. Who screw up, and admit it without being broken or defined by the screw-up, and work on ways to not screw up again. Who make good-but-imperfect choices, and  are genuinely slowed down by their exhaustion (an important one) yet help one another get back on their feet and keep working.

are genuinely slowed down by their exhaustion (an important one) yet help one another get back on their feet and keep working.

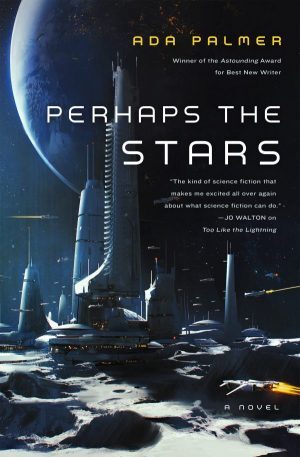

We need all sorts of stories, but we have a special need for hopepunk right now, because, in many people’s lived experience, this is one of those false-utopias which seemed great but has had its unforgivable underbelly exposed, plural underbellies in fact—climate impact, structural inequality, global inequity, systemic racism, dystopian tech. We need better models for what to do now than just blowing up the overlord’s tower, since that doesn’t fix it. Revolutionary France three revolutions later tells us that doesn’t fix it. As the final volume of my Terra Ignota (Perhaps the Stars) sees print this month, it’s amazing finally feeling how the themes and structure the series already had when I first planned it years ago have a different momentum here in 2021. People often ask if my outline changed as I wrote the books—it didn’t, but my understanding of what parts of that outline were powerful, and needed, that has changed. Speculative resistance is about looking at other ways the world could work (worse, better, mixed), and using that to help us think outside the box and push for new things. The hopepunk subsect of speculative resistance is about depicting how that push requires kindness, compromise, teamwork, resilience, and—tired as we are—a lot more time.

We need those stories, always, but especially right now.

Check Out Ada Palmer's Full Series - Terra Ignota

ADA PALMER is a professor in the history department of the University of Chicago, specializing in Renaissance history and the history of ideas. Her first nonfiction book, Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance, was published in 2014 by Harvard University Press. She is also a composer of folk and Renaissance-tinged a cappella vocal music on historical themes, most of which she performs with the group Sassafrass. She writes about history for a popular audience at exurbe.com and about SF and