David Tallerman's Blog, page 14

September 13, 2019

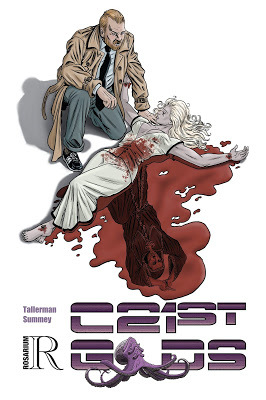

Requiem For the C21st Gods

Any career has it's share of disappointments, and the fate of my comic book C21st Gods perhaps wasn't the biggest I've had, but it's one that stuck with me - maybe because the project was so beset by disaster and then because it came so close to a measure of success. To have a book unpublished is one thing; to have a book partially published and doomed to never be finished is quite another. And somehow, the release of one issue of a three-and-a-bit part miniseries was almost worse than having nothing out at all.

Any career has it's share of disappointments, and the fate of my comic book C21st Gods perhaps wasn't the biggest I've had, but it's one that stuck with me - maybe because the project was so beset by disaster and then because it came so close to a measure of success. To have a book unpublished is one thing; to have a book partially published and doomed to never be finished is quite another. And somehow, the release of one issue of a three-and-a-bit part miniseries was almost worse than having nothing out at all.But the very worst of it was, it's not that great an issue. I mean, if we're honest, it's probably not that great a script full stop; beginning as a five page strip, then expanding into ten pages, then expanding into a graphic novel, it was born out of a few short, sharp shocks of effort that all seemed to occur at particularly rubbish times in my life. And once the artist it had been written for dropped out, it looked for an age as though it would never see the light of day. So I was all the more thrilled when eventually the pieces appeared to be coming together: with interesting-seeming independent outfit Rosarium in place as publisher and the talented Anthony Summey taking over on artist duties, it appeared that some good might come of all that work after all.

Yet, for reasons I guess I could dig into but won't, there was only ever this one issue, the weakest part of a book that was, in a weird sense, intended to start somewhat weakly. The thing is, I'd never meant for C21st Gods to appear in separate segments, and it was never going to comfortably fit that format; issue one was deliberately rife with clichés and the entire concept was built on playing with the reader's established expectations. Essentially, the book was two parts prologue, one part climax, and the climax was what everything was about.

Nevertheless, while it's certainly not the best thing I've written, there's plenty in C21st Gods that I think genuinely stands up, that last issue would have been pretty damn cool, and I wasn't comfortable with leaving things the way they'd been left. Therefore, as promised rather a long while back now, I've tidied the entire script a bit and stuck it up on my website. I realise I've been kind of negative about it, but I swear, it's worth a read - especially if, like me, you're one of those folks who likes to get a glimpse behind the scenes!

There's an index of all the parts here, or you can find each separate issue at the following links:

Issue 1, Issue 2, Issue 3, Epilogue.

Published on September 13, 2019 11:41

September 7, 2019

Film Ramble: Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 55

No themes or gimmicks this time around, just four titles selected at random from the to-watch shelf, with nothing much in common besides the fact that they're all nineties anime. Er, except for the two that are from 1989. Well, one and a half, anyway. Which reminds me, this is kind of five reviews rather than the usual four, or six if you count the fact that one title is two OVAs on a single disk. I swear, I don't know why I ever tried to set myself rules here! It's basically anarchy.

This time around: Spirit Warrior: Revival of Evil & Spirit Warrior: Regent of Darkness, Earthian, Goku Midnight Eye, and Mobile Suit Gundam F91: The Motion Picture...

Spirit Warrior: Revival of Evil / Spirit Warrior: Regent of Darkness, 1994, dir: Rintaro

Spirit Warrior: Revival of Evil / Spirit Warrior: Regent of Darkness, 1994, dir: Rintaro

Here's a first: there really is no sensible option except to review two separate DVD releases as one. And I suppose we can't altogether blame U.S. Manga Corps for putting out the twin parts of what's self-evidently a single film this way, since that appears to have been how they were released in Japan, but nor is there any getting around the fact that it's seriously cheeky.

Anyway, while they pose an unexpected reviewing problem, there's plenty of familiarity elsewhere. We've already covered a couple of short films from this supernatural horror series, in the shape of the nondescript Spirit Warrior: Festival of Ogres' Revival and the surprisingly good Spirit Warrior: Castle of Illusion - though it's worth noting that those two belonged to an earlier take on the franchise, preceding this by some five years. And we've also had plenty of encounters with the big-name director, Rintaro, who was chosen to drag Spirit Warrior back into the limelight.

I'm inclined to say that Rintaro is the best thing Revival of Evil and Regent of Darkness have going for them. I've noted before that the man is a staggering visual stylist when at his best, and an awful storyteller at his worst, and that he generally manages to hit both extremes in every work he produces, often simultaneously. But Spirit Warrior is well suited to playing up his strengths and disguising his signal weakness, or at least making it easier to ignore. The thing is, if you're here for the story then you've had it anyway: its tale of ancient evils manifesting in modern-day Japan is nothing you won't have encountered before if you've watched the least bit of dark fantasy anime. There are some novel twists, to be sure - robot neo-Nazis is a novel twist, right? - but on the whole it's hardly groundbreaking. With all of that said, while Rintaro can't wreck what's already broken, he's certainly not the sort to take a messy script in hand. In particular, the lack of a clear protagonist is a liability, as our supposed hero keeps getting sidelined for long stretches. It's impressive, really, how Revival of Darkness (as I'm now calling it) manages to shortchange all of its cast.

However, if we accept that the Spirit Warrior franchise was never about to offer up a searingly original narrative or a complex, three-dimensional characters, it's safe to say that having Rintaro on board is a damn good thing. Given a story that only succeeds on a scene-by-scene basis anyway, the fact that he directs the hell out of every one is a major plus. There's evidence of budgetary constraints, such as that Rintaro staple of entire scenes occurring more than once, but there's also an extraordinary visual sense at play. There are some terrific sequences here, along with many a gorgeous, painterly background. If it's not the loveliest of his works, because X and Metropolis both exist, it's not far off, and frequently that's enough to patch over those narrative weaknesses.

But there's no wrapping this up without going to back to where we started: Revival of Darkness is a single movie chopped inelegantly into two, and presumably planned that way, because watching it in a single take doesn't really help matters: too much of Revival of Evil is exposition and basically all of Regent of Darkness is climax. While it's absolutely possible to see how they could be re-edited into ninety minutes of brilliance, that's not what actually exists, and though there's lots here that's great and nothing genuinely bad, it probably remains one for Spirit Warrior and / or Rintaro completists only.

Earthian, 1989 / 1996, dir's: Kenichi Ohnuki, Nobuyasu Furukawa, Toshiyasu Kogawa

Earthian, 1989 / 1996, dir's: Kenichi Ohnuki, Nobuyasu Furukawa, Toshiyasu Kogawa

Sometimes, a little context would go a long way. I'm sure there's a good reason Earthian consists of two separate OVA series, one of two forty-five minute halves from the end of the eighties and a second of two thirty minute episodes from half a decade later. Likewise, I'm sure there's a reason the second part of the original series was basically a standalone tale, whereas the second series picks up the plot and certain characters from the first, albeit with a colossal time leap that skips the sort of events you'd think would be basically essential to any telling of this story. My best guess is that the anime was never meant to be watched in isolation, that more of the original series was intended, and that the second go round was planned to coincide with the manga's wrapping up. But three decades on, who besides hardened fans of a mostly forgotten comic book can say for sure?

Likewise, you can just about piece together the larger story from what's on offer here. Our protagonists are two angels, or at any rate beings that look and behave like angels, sent from a planet named Eden to judge whether mankind is safe to keep around. In a nice touch, one is tasked with totting up our worst failings, whereas the other is assigned to hunting out our better aspects. It follows that the latter, Kagetsuya, has a tendency of getting overly attached to these beings called Earthians, but that may also have something to do with him being a freak among his own kind. With black hair and wings, he's basically unique, though we learn in the second episode that certain "fallen" angels acquire those traits in their last days of life. There's a lot there that seems like it might be important, and probably was in the manga, but for our purposes, the majority gets either cast aside or wrapped up in those missing years, and when we return with the sequel, Kagetsuya and his partner Chihaya are in a relationship, Eden has judged the Earthians unworthy and fought an abortive war with them, and most of the plot revolves around a mad scientist from part one, who's created a synthetic human / angel hybrid that he plans to wipe out humanity with, in revenge for the off-screen death of a minor character he seemed largely indifferent to when last we saw him.

Which takes us back to my original point. There are intriguing ideas here, and hints of a fascinatingly mythology, but without the manga to refer to, digging them out feels too much like work. That leaves us with the characters, who start off appealing but soon settle into an irritating rut: Kagetsuya gets obsessed with someone he's met or heard about, Chihaya berates him, Kagetsuya rushes in anyway, only to get kidnapped or beaten up or both, and Chihaya ends up grudgingly saving him with his awesome martial arts skills. It's a fun dynamic for forty-five minutes, but after more than two hours I felt like I was being forced to hang around with a real bickering couple.

None of this is saved by the technical execution, which is pretty poor for the 1989 material (and worsened by technical issues on the AnimeWorks print) and maybe a little above average by the time we return in 1996; at any rate, there are some stunning backgrounds in the latter portion. The music is somewhat better, except for one syrupy ballad near the start, but it's not so great that it stands out. All told, that amounts to a moderately ugly first half with some novel storytelling and a notably prettier second half that manages to botch all of the character and narrative elements that made the beginning watchable, while mentioning in passing events that sound vastly more interesting than what we're shown. Put them together and you're not left with much besides the sense that the manga was probably a heck of a lot more time-worthy.

Goku Midnight Eye, 1989, dir: Yoshiaki Kawajiri

Goku Midnight Eye, 1989, dir: Yoshiaki Kawajiri

For a while at the back end of the eighties and the start of the nineties, Yoshiaki Kawajiri could do no wrong. Few directors were so in tune with the mood of the times, at least as far as it related to a certain kind of anime for a certain kind of audience. If you wanted violent, action-packed films and OVAs with copious nudity, above par animation, a distinctive aesthetic, and lashings of style, then Kawajiri was your man. I have no idea how well he was received in Japan (though the fact that he appears to have stayed in high-profile directing work for over a decade is surely indicative of something) but certainly in the West it's hard to point at a more iconic body of work. Kawajiri defined action horror in Wicked City and Demon City Shinjuku, did cyberpunk as well as any of his contemporaries with Cyber City Oedo 808, and followed both up with Ninja Scroll, a movie that for many a fan (though not this one) is the abiding high-point of nineties anime.

Yet with all that, you don't hear much talk of Goku Midnight Eye, the two hour long, two part OVA Kawajiri made between Demon City and Cyber City, and his first stab at the sort of neon-drenched, high concept SF he'd return to the following year. Many reviewers would have you believe that this is because Goku was a rare career misstep, too goofy and frantic to really be considered among his best work, and that's certainly an argument that can be made. In any other hands, the tale of ex-cop turned PI Goku Furinji, who survives a near-death encounter only to find himself gifted by a mysterious benefactor with a telescopic staff and an artificial eye that can hack into any computer system, would be a stretch of credibility; with Kawajiri leaning hard into his wildest impulses, it's giddy stuff indeed. Ever wanted a scene of a dwarf riding a laser-spitting robot pole dancer with motorcycle handlebars strapped to her back? Then Kawajiri has you covered.

That certainly highlights a couple of the genuine problems with Goku Midnight Eye. In common with basically everything Kawajiri produced, it's crass, violent, and exploitative in ways that haven't aged at all well, and especially in regards to its female characters, if we're willing to abuse the word that far. For me, the heightened unreality of the thing pulled me through; nobody, Goku included, behaves in any way like a rational human being or shows the slightest hint of depth. Then again, that also highlights its principle success, as an object of raw style over substance that flings ideas around with abandon. Even when the plot is being conventional, as in the second episode, where our hero finds himself tracking the enhanced victim of shady military experiments, the execution, the weird details, and the inordinate stylishness, makes the material feel fresh. And if this was true of Cyber City too, that show would subsequently be imitated to death in a manner that Goku Midnight Eye never was, meaning that its originality holds up all the better.

The result is the definition of not for all tastes, even insomuch as that's true of all of Kawajiri's oeuvre. And if you're unlucky enough to get caught up in the mystery of who Goku's benefactor is and why he's willing to hand him a power that could destroy all life on Earth in a heartbeat, then you're definitely out of luck, because the show drops that aspect nearly as quickly as it's raised. But want some striking, lushly animated, deeply weird cyberpunk with an insane concept and a perfect marriage of Film Noir and eighties kitsch, topped off with a theme tune that couldn't epitomise that marriage any harder if it tried? Then you might just love the heck out of Goku Midnight Eye.

Mobile Suit Gundam F91: The Motion Picture, 1991, dir: Yoshiyuki Tomino

Mobile Suit Gundam F91: The Motion Picture, 1991, dir: Yoshiyuki Tomino

There are, I'd say, two significant criticisms that can be aimed at Mobile Suit Gundam F91, and both stem from the same source. Intended to be the beginning of a new saga in the Gundam universe, production difficulties found it downgraded from a planned series to a movie of fractionally less than two hours that crams in an inordinate amount of plot and a sizable cast at a breakneck pace. And presumably because this was to be something of a soft reboot, that plot and those characters are awfully similar to those of the original Mobile Suit Gundam. An aristocratic family decide to turn their backs on a complacent, selfish Earth government, beginning by violently capturing an isolated colony, driving a band of plucky civilians to fight at first for survival and then, by degrees, because it's apparent that they're as good at it as the so-called professionals who haven't cut their teeth on the sort of bloody conflict they've seen. Heck, our heroes even get a White Base of their own, and it truly doesn't need saying that our sullen, youthful protagonist with a host of parental issues ends up in the cockpit of a certain red, white, and blue mecha.

So: it's Mobile Suit Gundam, except in two hours and with feature quality animation, or at least something a heck of a lot closer to that mark than TV animation from over a decade earlier, and told by a director who'd had no end of practice with the franchise by this point. With all of that, and while there are many who seem to hold it in low regard for these reasons, I'm inclined to call Mobile Suit Gundam F91 my favourite chunk of Gundam so far, at least if we ignore the recent, superb Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin. It's certainly on a par with War in the Pocket, my previous personal high point, and indeed I liked it for many the same reasons. The opening assault on Frontier IV, for example, is an extraordinary way to kick things off, showing in no uncertain terms what it would be like to be a civilian caught in a battle of robots as large as buildings; at one point, someone's even killed by a falling shell casing bigger than their head. It's a chaotic, exhilarating, horrifying sequence that sums up as well as anything I could point at why this is such an enduring franchise.

Inevitably, Tomino has to take his foot off the gas a little after that, but there are plenty of other terrific scenes to come. Moreover, while you could argue that everyone except the core cast receive short shrift, it's also true that the film does fine work of sketching in details with the bare minimum of beats, cramming entire arcs into a line of dialogue or a gesture. It's exhausting, it's a ton of work to keep up with, and there are moments when even then it really feels like a bit more footage would not only have been useful but vital. On the other hand, it does most of what the movie trilogy of the original Mobile Suit Gundam did, and - again, presumably because Tomino had this stuff down by now - does a great deal of it better, while routinely looking and sounding fantastic.

Nonetheless, this clearly isn't going to be for everyone, or even every Gundam fan. Since it's a standalone story, you might argue that it's a good jumping-on point, but I suspect I'd have struggled even more without a reasonable sense of how the universe functions, because Mobile Suit Gundam F91 hardly makes a single concession in that direction. Then again, the core narrative is certainly self-contained, as much as it ends with the promise of sequels that would never materialise. Possibly the answer, then, is that this is one for the established but casual Gundam fan, as I guess I'd have to term myself by now. Yet that still feels like a disservice, and I'd suggest that if you've a fondness for space opera and / or giant robots, or just want a taste of what's on offer without digging into any of the many series, F91 is seriously worth a look.

-oOo-

Hmm, I feel like I got close to recommending three out of four titles and then shied away a bit at the last second. Look, if any one of Spirit Warrior, Goku Midnight Eye, or Mobile Suit Gundam F91 sounds like it might float your boat then you should absolutely give them a go, and especially those last two, both of which are pretty much excellent. It's just that cyberpunk interpretations of Journey to the West and failed attempts to get a new Gundam franchise off the ground are never going to be everyone's bag, you know?

Next time around, if all goes to plan, we'll be heading back to the eighties again, in this blog series that I really ought to have given a less decade-specific name...

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

This time around: Spirit Warrior: Revival of Evil & Spirit Warrior: Regent of Darkness, Earthian, Goku Midnight Eye, and Mobile Suit Gundam F91: The Motion Picture...

Spirit Warrior: Revival of Evil / Spirit Warrior: Regent of Darkness, 1994, dir: Rintaro

Spirit Warrior: Revival of Evil / Spirit Warrior: Regent of Darkness, 1994, dir: RintaroHere's a first: there really is no sensible option except to review two separate DVD releases as one. And I suppose we can't altogether blame U.S. Manga Corps for putting out the twin parts of what's self-evidently a single film this way, since that appears to have been how they were released in Japan, but nor is there any getting around the fact that it's seriously cheeky.

Anyway, while they pose an unexpected reviewing problem, there's plenty of familiarity elsewhere. We've already covered a couple of short films from this supernatural horror series, in the shape of the nondescript Spirit Warrior: Festival of Ogres' Revival and the surprisingly good Spirit Warrior: Castle of Illusion - though it's worth noting that those two belonged to an earlier take on the franchise, preceding this by some five years. And we've also had plenty of encounters with the big-name director, Rintaro, who was chosen to drag Spirit Warrior back into the limelight.

I'm inclined to say that Rintaro is the best thing Revival of Evil and Regent of Darkness have going for them. I've noted before that the man is a staggering visual stylist when at his best, and an awful storyteller at his worst, and that he generally manages to hit both extremes in every work he produces, often simultaneously. But Spirit Warrior is well suited to playing up his strengths and disguising his signal weakness, or at least making it easier to ignore. The thing is, if you're here for the story then you've had it anyway: its tale of ancient evils manifesting in modern-day Japan is nothing you won't have encountered before if you've watched the least bit of dark fantasy anime. There are some novel twists, to be sure - robot neo-Nazis is a novel twist, right? - but on the whole it's hardly groundbreaking. With all of that said, while Rintaro can't wreck what's already broken, he's certainly not the sort to take a messy script in hand. In particular, the lack of a clear protagonist is a liability, as our supposed hero keeps getting sidelined for long stretches. It's impressive, really, how Revival of Darkness (as I'm now calling it) manages to shortchange all of its cast.

However, if we accept that the Spirit Warrior franchise was never about to offer up a searingly original narrative or a complex, three-dimensional characters, it's safe to say that having Rintaro on board is a damn good thing. Given a story that only succeeds on a scene-by-scene basis anyway, the fact that he directs the hell out of every one is a major plus. There's evidence of budgetary constraints, such as that Rintaro staple of entire scenes occurring more than once, but there's also an extraordinary visual sense at play. There are some terrific sequences here, along with many a gorgeous, painterly background. If it's not the loveliest of his works, because X and Metropolis both exist, it's not far off, and frequently that's enough to patch over those narrative weaknesses.

But there's no wrapping this up without going to back to where we started: Revival of Darkness is a single movie chopped inelegantly into two, and presumably planned that way, because watching it in a single take doesn't really help matters: too much of Revival of Evil is exposition and basically all of Regent of Darkness is climax. While it's absolutely possible to see how they could be re-edited into ninety minutes of brilliance, that's not what actually exists, and though there's lots here that's great and nothing genuinely bad, it probably remains one for Spirit Warrior and / or Rintaro completists only.

Earthian, 1989 / 1996, dir's: Kenichi Ohnuki, Nobuyasu Furukawa, Toshiyasu Kogawa

Earthian, 1989 / 1996, dir's: Kenichi Ohnuki, Nobuyasu Furukawa, Toshiyasu KogawaSometimes, a little context would go a long way. I'm sure there's a good reason Earthian consists of two separate OVA series, one of two forty-five minute halves from the end of the eighties and a second of two thirty minute episodes from half a decade later. Likewise, I'm sure there's a reason the second part of the original series was basically a standalone tale, whereas the second series picks up the plot and certain characters from the first, albeit with a colossal time leap that skips the sort of events you'd think would be basically essential to any telling of this story. My best guess is that the anime was never meant to be watched in isolation, that more of the original series was intended, and that the second go round was planned to coincide with the manga's wrapping up. But three decades on, who besides hardened fans of a mostly forgotten comic book can say for sure?

Likewise, you can just about piece together the larger story from what's on offer here. Our protagonists are two angels, or at any rate beings that look and behave like angels, sent from a planet named Eden to judge whether mankind is safe to keep around. In a nice touch, one is tasked with totting up our worst failings, whereas the other is assigned to hunting out our better aspects. It follows that the latter, Kagetsuya, has a tendency of getting overly attached to these beings called Earthians, but that may also have something to do with him being a freak among his own kind. With black hair and wings, he's basically unique, though we learn in the second episode that certain "fallen" angels acquire those traits in their last days of life. There's a lot there that seems like it might be important, and probably was in the manga, but for our purposes, the majority gets either cast aside or wrapped up in those missing years, and when we return with the sequel, Kagetsuya and his partner Chihaya are in a relationship, Eden has judged the Earthians unworthy and fought an abortive war with them, and most of the plot revolves around a mad scientist from part one, who's created a synthetic human / angel hybrid that he plans to wipe out humanity with, in revenge for the off-screen death of a minor character he seemed largely indifferent to when last we saw him.

Which takes us back to my original point. There are intriguing ideas here, and hints of a fascinatingly mythology, but without the manga to refer to, digging them out feels too much like work. That leaves us with the characters, who start off appealing but soon settle into an irritating rut: Kagetsuya gets obsessed with someone he's met or heard about, Chihaya berates him, Kagetsuya rushes in anyway, only to get kidnapped or beaten up or both, and Chihaya ends up grudgingly saving him with his awesome martial arts skills. It's a fun dynamic for forty-five minutes, but after more than two hours I felt like I was being forced to hang around with a real bickering couple.

None of this is saved by the technical execution, which is pretty poor for the 1989 material (and worsened by technical issues on the AnimeWorks print) and maybe a little above average by the time we return in 1996; at any rate, there are some stunning backgrounds in the latter portion. The music is somewhat better, except for one syrupy ballad near the start, but it's not so great that it stands out. All told, that amounts to a moderately ugly first half with some novel storytelling and a notably prettier second half that manages to botch all of the character and narrative elements that made the beginning watchable, while mentioning in passing events that sound vastly more interesting than what we're shown. Put them together and you're not left with much besides the sense that the manga was probably a heck of a lot more time-worthy.

Goku Midnight Eye, 1989, dir: Yoshiaki Kawajiri

Goku Midnight Eye, 1989, dir: Yoshiaki KawajiriFor a while at the back end of the eighties and the start of the nineties, Yoshiaki Kawajiri could do no wrong. Few directors were so in tune with the mood of the times, at least as far as it related to a certain kind of anime for a certain kind of audience. If you wanted violent, action-packed films and OVAs with copious nudity, above par animation, a distinctive aesthetic, and lashings of style, then Kawajiri was your man. I have no idea how well he was received in Japan (though the fact that he appears to have stayed in high-profile directing work for over a decade is surely indicative of something) but certainly in the West it's hard to point at a more iconic body of work. Kawajiri defined action horror in Wicked City and Demon City Shinjuku, did cyberpunk as well as any of his contemporaries with Cyber City Oedo 808, and followed both up with Ninja Scroll, a movie that for many a fan (though not this one) is the abiding high-point of nineties anime.

Yet with all that, you don't hear much talk of Goku Midnight Eye, the two hour long, two part OVA Kawajiri made between Demon City and Cyber City, and his first stab at the sort of neon-drenched, high concept SF he'd return to the following year. Many reviewers would have you believe that this is because Goku was a rare career misstep, too goofy and frantic to really be considered among his best work, and that's certainly an argument that can be made. In any other hands, the tale of ex-cop turned PI Goku Furinji, who survives a near-death encounter only to find himself gifted by a mysterious benefactor with a telescopic staff and an artificial eye that can hack into any computer system, would be a stretch of credibility; with Kawajiri leaning hard into his wildest impulses, it's giddy stuff indeed. Ever wanted a scene of a dwarf riding a laser-spitting robot pole dancer with motorcycle handlebars strapped to her back? Then Kawajiri has you covered.

That certainly highlights a couple of the genuine problems with Goku Midnight Eye. In common with basically everything Kawajiri produced, it's crass, violent, and exploitative in ways that haven't aged at all well, and especially in regards to its female characters, if we're willing to abuse the word that far. For me, the heightened unreality of the thing pulled me through; nobody, Goku included, behaves in any way like a rational human being or shows the slightest hint of depth. Then again, that also highlights its principle success, as an object of raw style over substance that flings ideas around with abandon. Even when the plot is being conventional, as in the second episode, where our hero finds himself tracking the enhanced victim of shady military experiments, the execution, the weird details, and the inordinate stylishness, makes the material feel fresh. And if this was true of Cyber City too, that show would subsequently be imitated to death in a manner that Goku Midnight Eye never was, meaning that its originality holds up all the better.

The result is the definition of not for all tastes, even insomuch as that's true of all of Kawajiri's oeuvre. And if you're unlucky enough to get caught up in the mystery of who Goku's benefactor is and why he's willing to hand him a power that could destroy all life on Earth in a heartbeat, then you're definitely out of luck, because the show drops that aspect nearly as quickly as it's raised. But want some striking, lushly animated, deeply weird cyberpunk with an insane concept and a perfect marriage of Film Noir and eighties kitsch, topped off with a theme tune that couldn't epitomise that marriage any harder if it tried? Then you might just love the heck out of Goku Midnight Eye.

Mobile Suit Gundam F91: The Motion Picture, 1991, dir: Yoshiyuki Tomino

Mobile Suit Gundam F91: The Motion Picture, 1991, dir: Yoshiyuki TominoThere are, I'd say, two significant criticisms that can be aimed at Mobile Suit Gundam F91, and both stem from the same source. Intended to be the beginning of a new saga in the Gundam universe, production difficulties found it downgraded from a planned series to a movie of fractionally less than two hours that crams in an inordinate amount of plot and a sizable cast at a breakneck pace. And presumably because this was to be something of a soft reboot, that plot and those characters are awfully similar to those of the original Mobile Suit Gundam. An aristocratic family decide to turn their backs on a complacent, selfish Earth government, beginning by violently capturing an isolated colony, driving a band of plucky civilians to fight at first for survival and then, by degrees, because it's apparent that they're as good at it as the so-called professionals who haven't cut their teeth on the sort of bloody conflict they've seen. Heck, our heroes even get a White Base of their own, and it truly doesn't need saying that our sullen, youthful protagonist with a host of parental issues ends up in the cockpit of a certain red, white, and blue mecha.

So: it's Mobile Suit Gundam, except in two hours and with feature quality animation, or at least something a heck of a lot closer to that mark than TV animation from over a decade earlier, and told by a director who'd had no end of practice with the franchise by this point. With all of that, and while there are many who seem to hold it in low regard for these reasons, I'm inclined to call Mobile Suit Gundam F91 my favourite chunk of Gundam so far, at least if we ignore the recent, superb Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin. It's certainly on a par with War in the Pocket, my previous personal high point, and indeed I liked it for many the same reasons. The opening assault on Frontier IV, for example, is an extraordinary way to kick things off, showing in no uncertain terms what it would be like to be a civilian caught in a battle of robots as large as buildings; at one point, someone's even killed by a falling shell casing bigger than their head. It's a chaotic, exhilarating, horrifying sequence that sums up as well as anything I could point at why this is such an enduring franchise.

Inevitably, Tomino has to take his foot off the gas a little after that, but there are plenty of other terrific scenes to come. Moreover, while you could argue that everyone except the core cast receive short shrift, it's also true that the film does fine work of sketching in details with the bare minimum of beats, cramming entire arcs into a line of dialogue or a gesture. It's exhausting, it's a ton of work to keep up with, and there are moments when even then it really feels like a bit more footage would not only have been useful but vital. On the other hand, it does most of what the movie trilogy of the original Mobile Suit Gundam did, and - again, presumably because Tomino had this stuff down by now - does a great deal of it better, while routinely looking and sounding fantastic.

Nonetheless, this clearly isn't going to be for everyone, or even every Gundam fan. Since it's a standalone story, you might argue that it's a good jumping-on point, but I suspect I'd have struggled even more without a reasonable sense of how the universe functions, because Mobile Suit Gundam F91 hardly makes a single concession in that direction. Then again, the core narrative is certainly self-contained, as much as it ends with the promise of sequels that would never materialise. Possibly the answer, then, is that this is one for the established but casual Gundam fan, as I guess I'd have to term myself by now. Yet that still feels like a disservice, and I'd suggest that if you've a fondness for space opera and / or giant robots, or just want a taste of what's on offer without digging into any of the many series, F91 is seriously worth a look.

-oOo-

Hmm, I feel like I got close to recommending three out of four titles and then shied away a bit at the last second. Look, if any one of Spirit Warrior, Goku Midnight Eye, or Mobile Suit Gundam F91 sounds like it might float your boat then you should absolutely give them a go, and especially those last two, both of which are pretty much excellent. It's just that cyberpunk interpretations of Journey to the West and failed attempts to get a new Gundam franchise off the ground are never going to be everyone's bag, you know?

Next time around, if all goes to plan, we'll be heading back to the eighties again, in this blog series that I really ought to have given a less decade-specific name...

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

Published on September 07, 2019 13:03

August 21, 2019

Film Ramble: Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 54

If there's one thing that firmly differentiates nineties anime from Western films and TV of the period, it's the willingness to put female characters front and centre, often to the point where they make up basically the entire cast. Sometimes - heck, often! - that can be for reasons that are closer to exploitation than feminism, yet there's a great deal of stuff that occupies a weird middle ground that, sure, crowbars in more shots of underwear than can reasonably be justified, but also manages to present an interesting, complex female cast, or else a protagonist who's every bit as capable and more as the men around her.

And yes, this is me flailing for a themed post topic, but hey. Here we have four titles that focus on female protagonists and largely female casts, and yet take very different approaches, in the shape of: Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie, Idol Project, Kekko Kamen, and Cleopatra D.C....

Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie, 1999, dir: Morio Asaka

Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie, 1999, dir: Morio Asaka

Above all else, the first Carcaptor Sakura feature is an extraordinarily pleasant film. It portrays pleasant characters having pleasant adventures in pleasant locations, via soft and appealing designs and a warm palette and mostly fun and gentle music. Even when it gets dark and creepy - as it does quite frequently, and more so than the TV series, from what I've read - it feels as though the shift in tone is less to persuade you that something bad might happen to a favourite character, as there's never the slightest suspicion that it genuinely will, but more to offer contrast. Indeed, the moments that have most potential to be scary are played in a quite different register, a sort of wistfulness that makes perfect sense by the time the plot has reached its end.

Mind you, I use the word "plot" advisedly. It's hard to imagine a more wafer-thin story supporting eighty minutes of film. The conflict doesn't get started in any meaningful way until past the halfway point, and is incredibly minor in scope, threatening Sakura and her friends in a rather indirect fashion but never anyone else: at one point, a few random people are rained on, and that's the closest to a city-shaking crisis we get. Indeed, the movie is much more interested in plucking up its cast and dropping them into a new setting - in this case, Hong Kong - and generally watching them hang out amid that change of scenery. It's possible that the larger narrative is plugging a few gaps in Cardcaptors law that I'm oblivious to, but if it is, I doubt they're answers anyone was desperately seeking. It's all incredibly low key and inconsequential, in a way that seems altogether deliberate.

As such, this isn't a criticism, or not really. The plot was certainly too airy for me, but I fully acknowledge that I'm not the intended audience here: I'm not familiar with the series or the manga, and perhaps more importantly, I'm not a young Japanese girl. And even with all of that said, I had no trouble following along, or figuring out relationships and crucial details, and no trouble staying engaged either. It helps that Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie looks terrific, with a generally high level of animation worthy of a cinematic release, some deft direction from Asaka, and frequent moments of real loveliness and artistry; there's a sense of affection for the material that marks this out as no mere knocked-off franchise film. It's not exactly thrilling and the story won't stay with you past the opening credits, but for what it is, a magical girl adventure that prizes niceness, decency, and inclusivity over all else, it's very good indeed, and it's easy to see why Eastern Star recently chose to save it on blu-ray when many a similar title from the time is lost to obscurity.

Idol Project, 1995, dir's: Keitarô Motonaga, Yasuchika Nagaoka, Yutaka Sato

Idol Project, 1995, dir's: Keitarô Motonaga, Yasuchika Nagaoka, Yutaka Sato

When I say that Idol Project is hilarious, what I mean, of course, is that I found it hilarious, because nothing's more subjective than humour. And I think that's truer than ever here, since while I laughed out loud a good many times - indeed, as much as I have at any anime comedy - I can readily imagine someone else barely cracking a smile. Because Idol Project is also phenomenally stupid, and absolutely expects you to be as devoted to the most absurd aspects of Japanese popular culture as it is.

To set the scene a little: Mimu Emilton wants nothing more than to be a pop idol, like her hero Yuri, an idol so idol-tastic that she ended up becoming president of the world, only to immediately abdicate and set up six other idols as effectively the rulers of the planet, despite the fact that none of them seem to be remotely competent human beings. Mimu's convinced that if she can just compete in a yearly talent contest, then she can join their ranks, but it seems the universe has different ideas, as both she and the six Excellent Idols get kidnapped by aliens for the purposes of -

Look, there's no point going any further with this, is there? I mean, that right there is barely the first episode, and things only get more preposterous going forward. And then more preposterous, and more, until somehow the fate of the galaxy is at stake, though for the most incomprehensible reasons. I mean, the starting point here is a world run by pop idols! And it's not even as if they're any good at that; a fair percentage of the jokes involve the characters shouting out at inopportune times the one-word motivational catchphrases that represent their single trait personalities. Which, I have to stress, is funnier than it has any right to be if you happen to be on the show's wavelength, as I clearly can't guarantee anyone else might be.

What else is there to say? Well, there's a ton of fan service, which would normally put me off in a big way but here feels like part of the joke, especially since it's mostly confined to the single episode where the idols have to try and desperately reinvent their careers by any means possible on an alien planet. And needless to say, it's about as sexy as watching particularly unsexy paint dry, given those colossally eyed character designs, which again I'd normally hate and here are perfect in their absurdity. Meanwhile, the animation is mid-budget OVA stuff, but made with enough passion that you can tell the creators were committed to this madness. And the music, unsurprisingly for a show about idols, is some of the giddiest bubblegum pop you could hope for, yet with enough of a weird edge to make it funny rather than merely twee.

Actually, I think I've inadvertently summed up Idol Project perfectly, because that's its absolute core: delivering the campiest, most saccharine pastiche of anime and Japanese pop culture, with just enough of a knowing wink to let us in on the joke. And with that bit of summing up done, I'd better just mention the most bizarre fact about the show, which is that someone thought it would be a bright idea to reuse its barcode on hardcore hentai DVD La Blue Girl, and as such I now own two copies of La Blue Girl that I really don't want. On the other hand, it feels somehow entirely appropriate that, when you order Idol Project, there's a two in three chance of ending up with tentacle porn...

Kekko Kamen, 1991, dir's: Nobuhiro Kondô, Shunichi Tokunaga, Kinji Yoshimoto

Kekko Kamen, 1991, dir's: Nobuhiro Kondô, Shunichi Tokunaga, Kinji Yoshimoto

If there's one thing Kekko Kamen could urgently do with, it's some jokes. I think the creators thought they were there, but there's a big difference between a broadly amusing set of circumstances and a gag of the sort that might make you laugh out loud. Kekko Kamen is often broadly amusing - and let's be clear, if the humour here is anything, it's broad - but truly funny? Not so much.

Still, if you're willing to look past how purposefully crass it all is, the sheer ridiculousness of Kekko Kamen's setup is hard not to smirk at. Sparta Academy has some unconventional attitudes to teaching and a perverse approach to punishing students who don't shape up, to the extent that they even have a member of the faculty devoted to nothing but said punishment: in the first episode, it's a Nazi-themed S&M fanatic named Gestapoko, which should tell you about eighty percent of what you ought to expect here. Anyway, our villains are particularly obsessed with first year student Mayumi Takahashi, and what better way to express their displeasure at her poor grades than to strap her to a giant swastika and cut her clothes off with throwing knives? Fortunately for Mayumi, Sparta Academy has just acquired a new hero, and if she's not necessarily the one it needs, she's certainly what it deserves: Kekko Kamen fights in boots, gloves, a mask with goggles and giant rabbit ears, and nothing else. As she cheerfully proclaims, nobody knows her face but the whole world knows her body, and she's not above suffocating her foes with her crotch if that's what the cause of love and justice demands.

Though, in one of those elements that resembles a joke without altogether becoming one, it's hard not to notice that, for all her birthday suit-clad heroics, Kekko Kamen only ever really seems to rescue Mayumi, and then only ever after she's been stripped down to her pants. You wonder if she's altogether thought this heroing business through. Nonetheless, our masked avenger is one of the most outright fun aspects of the four episodes, possessed of a beguiling innocence and lack of common sense which suggests that, yes, she did sit down and conclude that fighting crime in the buff is definitely the way to go. Which is all to the best given that the rest of the cast aren't half so engaging; the main villains, in particular, are visually intriguing but have one personality trait between them, if lecherousness counts as a personality trait. Indeed, it's only in the fourth and final part that Kekko Kamen gets to test her skills against a worthy foe, a fallen samurai with a penchant for snapping indecent Polaroids and, er, making umbrellas.

The animation is distinctly mediocre and some of the designs are flat-out horrible - there's something terribly wrong about Mayumi's eyes - though you probably won't be surprised to hear that a degree of loving attention goes into getting all those naked female bodies right. Weirdly, things improve markedly with the third episode, otherwise the least interesting due to a shift of focus onto Mayumi's infatuation with a beautiful transfer student, and then get worse again for the climax, which is in all other ways by far the best, thanks to being the first to spend time setting up a few real gags. At least the ludicrous theme tune is a pleasure, an energetic ode to its heroine's righteousness with some immensely dopey lyrics. But I dunno, add all of that up and the results still feel like awfully little for something trying so hard to be shocking. Ultimately, I guess that's the problem: cartoon nudity and crass gags are fine if that's your bag, but for me, the only thing that could turn those elements into genuine entertainment is some actual humour. As such, while Kekko Kamen is a tolerable distraction, it's easy to imagine a version that's greatly more enjoyable than what we get.

Cleopatra D.C., 1989, dir: Naoyuki Yoshinaga

Cleopatra D.C., 1989, dir: Naoyuki Yoshinaga

It would be tough to write a review of Cleopatra D.C. that didn't degenerate into a list of all the ways in which it's a bit odd, and given that these reviews are a hobby and not a job, I guess there's no reason I should try! Though even then, there's the temptation to just say "Pretty much everything" and leave it there. The thing is, even the basic setup is strange. Our hero, she of the unlikely name Cleopatra Corns, is the leader of the Corns Group, which basically seems to own half the world, but only uses its corporate powers for good. This leaves young Cleo with trillions of dollars at her disposal and an excess of time on her hands, both of which she spends getting into adventures that mostly seem to revolve around a combination of damsels in distress and the shenanigans of another mega-corporation that devotes its resources solely to the dirtiest sorts of profit. So right there we already have a protagonist who's basically a gender-swapped Batman without the angst and flying rodent fetish.

Cleo also couldn't be much higher up in the one percent if she tried, and that would make her awfully hard to empathise with if she wasn't such a fun presence, bouncing from crisis to crisis with the giddy abandon of a sixteen year old who has all the money in the world. Her idea of problem solving, at one time or another, might involve guns, jet packs, ICBMs, parachuting from a fighter plane so that she can shoot at a space rocket with a missile launcher, or just plain buying up an entire firm. And this in turn leads to some exceedingly strange plots, which seem to be almost but not quite a pastiche of American action cinema - not quite because the show is ultimately too in love with that sort of preposterous excess to wish it any real harm. Indeed, it feels very much like what would happen if someone got the wildly wrong-headed idea that Roger Moore-era James Bond was a great template to emulate. And like so much of pre-twentieth century anime, you're sometimes left wondering who the audience is meant to be. Cleo is just enough like a real sixteen-year-old girl, hanging out with her ever-expanding band of female friends, to suggest that the answer is other teenage girls, but then there are sufficiently gratuitous shots of her naked butt to imply that, no, it was teenage boys after all, and presumably they're the ones who might be expected to get most out of its Moonraker-esque dementedness.

Add to that the character designs, which are relatively normal for the period when it comes to the men and very weird indeed when it comes to the women: Cleo and co look as if someone tried to funnel a contemporary anime aesthetic through the medium of Betty Boop, and thus become the only characters in all of anime to not only have eyes bigger than their mouths but to have eyelashes as big as their eyes. And while the animation is fair to middling, it's not the fair to middling of 1989; had I been guessing, I'd have pegged it at maybe a half decade later. Meanwhile, the jazzy score is a nice fit for the material, but just unusual enough to fit into Cleopatra D.C.'s generally off-kilter landscape. Heck, the show can't even get its episode structure right: the first two are standard length and the third clocks in at fifty minutes, so why not just split it in two? But Cleopatra D.C., like its titular protagonist, refuses to do anything in conventional fashion. Whether that makes the end result worthy of your time is, I suppose, another question. It's certainly fun, pleasant enough to look at, and full of energy and ideas - though it has to be said that the longest episode is the one that feels most conventional. Even then, though, if you're looking for something different, it's certainly an intriguing curio.

-oOo-

Dumb themes aside, there was kind of a serious purpose here: I definitely find it interesting that anime from three decades ago was happy to put female protagonists front and centre when there are still large portions of the US film and TV industry that consider the idea a bit of a gamble. But in honestly, I'm not sure this particular selection tells us a huge deal, though at least we touched on some of the major bases. And whatever else, I enjoyed the lot: even the basically rubbish Kekko Kamen was fun in its own weird way!

Next up: no stupid themes, hopefully.

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

And yes, this is me flailing for a themed post topic, but hey. Here we have four titles that focus on female protagonists and largely female casts, and yet take very different approaches, in the shape of: Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie, Idol Project, Kekko Kamen, and Cleopatra D.C....

Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie, 1999, dir: Morio Asaka

Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie, 1999, dir: Morio AsakaAbove all else, the first Carcaptor Sakura feature is an extraordinarily pleasant film. It portrays pleasant characters having pleasant adventures in pleasant locations, via soft and appealing designs and a warm palette and mostly fun and gentle music. Even when it gets dark and creepy - as it does quite frequently, and more so than the TV series, from what I've read - it feels as though the shift in tone is less to persuade you that something bad might happen to a favourite character, as there's never the slightest suspicion that it genuinely will, but more to offer contrast. Indeed, the moments that have most potential to be scary are played in a quite different register, a sort of wistfulness that makes perfect sense by the time the plot has reached its end.

Mind you, I use the word "plot" advisedly. It's hard to imagine a more wafer-thin story supporting eighty minutes of film. The conflict doesn't get started in any meaningful way until past the halfway point, and is incredibly minor in scope, threatening Sakura and her friends in a rather indirect fashion but never anyone else: at one point, a few random people are rained on, and that's the closest to a city-shaking crisis we get. Indeed, the movie is much more interested in plucking up its cast and dropping them into a new setting - in this case, Hong Kong - and generally watching them hang out amid that change of scenery. It's possible that the larger narrative is plugging a few gaps in Cardcaptors law that I'm oblivious to, but if it is, I doubt they're answers anyone was desperately seeking. It's all incredibly low key and inconsequential, in a way that seems altogether deliberate.

As such, this isn't a criticism, or not really. The plot was certainly too airy for me, but I fully acknowledge that I'm not the intended audience here: I'm not familiar with the series or the manga, and perhaps more importantly, I'm not a young Japanese girl. And even with all of that said, I had no trouble following along, or figuring out relationships and crucial details, and no trouble staying engaged either. It helps that Carcaptor Sakura: The Movie looks terrific, with a generally high level of animation worthy of a cinematic release, some deft direction from Asaka, and frequent moments of real loveliness and artistry; there's a sense of affection for the material that marks this out as no mere knocked-off franchise film. It's not exactly thrilling and the story won't stay with you past the opening credits, but for what it is, a magical girl adventure that prizes niceness, decency, and inclusivity over all else, it's very good indeed, and it's easy to see why Eastern Star recently chose to save it on blu-ray when many a similar title from the time is lost to obscurity.

Idol Project, 1995, dir's: Keitarô Motonaga, Yasuchika Nagaoka, Yutaka Sato

Idol Project, 1995, dir's: Keitarô Motonaga, Yasuchika Nagaoka, Yutaka SatoWhen I say that Idol Project is hilarious, what I mean, of course, is that I found it hilarious, because nothing's more subjective than humour. And I think that's truer than ever here, since while I laughed out loud a good many times - indeed, as much as I have at any anime comedy - I can readily imagine someone else barely cracking a smile. Because Idol Project is also phenomenally stupid, and absolutely expects you to be as devoted to the most absurd aspects of Japanese popular culture as it is.

To set the scene a little: Mimu Emilton wants nothing more than to be a pop idol, like her hero Yuri, an idol so idol-tastic that she ended up becoming president of the world, only to immediately abdicate and set up six other idols as effectively the rulers of the planet, despite the fact that none of them seem to be remotely competent human beings. Mimu's convinced that if she can just compete in a yearly talent contest, then she can join their ranks, but it seems the universe has different ideas, as both she and the six Excellent Idols get kidnapped by aliens for the purposes of -

Look, there's no point going any further with this, is there? I mean, that right there is barely the first episode, and things only get more preposterous going forward. And then more preposterous, and more, until somehow the fate of the galaxy is at stake, though for the most incomprehensible reasons. I mean, the starting point here is a world run by pop idols! And it's not even as if they're any good at that; a fair percentage of the jokes involve the characters shouting out at inopportune times the one-word motivational catchphrases that represent their single trait personalities. Which, I have to stress, is funnier than it has any right to be if you happen to be on the show's wavelength, as I clearly can't guarantee anyone else might be.

What else is there to say? Well, there's a ton of fan service, which would normally put me off in a big way but here feels like part of the joke, especially since it's mostly confined to the single episode where the idols have to try and desperately reinvent their careers by any means possible on an alien planet. And needless to say, it's about as sexy as watching particularly unsexy paint dry, given those colossally eyed character designs, which again I'd normally hate and here are perfect in their absurdity. Meanwhile, the animation is mid-budget OVA stuff, but made with enough passion that you can tell the creators were committed to this madness. And the music, unsurprisingly for a show about idols, is some of the giddiest bubblegum pop you could hope for, yet with enough of a weird edge to make it funny rather than merely twee.

Actually, I think I've inadvertently summed up Idol Project perfectly, because that's its absolute core: delivering the campiest, most saccharine pastiche of anime and Japanese pop culture, with just enough of a knowing wink to let us in on the joke. And with that bit of summing up done, I'd better just mention the most bizarre fact about the show, which is that someone thought it would be a bright idea to reuse its barcode on hardcore hentai DVD La Blue Girl, and as such I now own two copies of La Blue Girl that I really don't want. On the other hand, it feels somehow entirely appropriate that, when you order Idol Project, there's a two in three chance of ending up with tentacle porn...

Kekko Kamen, 1991, dir's: Nobuhiro Kondô, Shunichi Tokunaga, Kinji Yoshimoto

Kekko Kamen, 1991, dir's: Nobuhiro Kondô, Shunichi Tokunaga, Kinji YoshimotoIf there's one thing Kekko Kamen could urgently do with, it's some jokes. I think the creators thought they were there, but there's a big difference between a broadly amusing set of circumstances and a gag of the sort that might make you laugh out loud. Kekko Kamen is often broadly amusing - and let's be clear, if the humour here is anything, it's broad - but truly funny? Not so much.

Still, if you're willing to look past how purposefully crass it all is, the sheer ridiculousness of Kekko Kamen's setup is hard not to smirk at. Sparta Academy has some unconventional attitudes to teaching and a perverse approach to punishing students who don't shape up, to the extent that they even have a member of the faculty devoted to nothing but said punishment: in the first episode, it's a Nazi-themed S&M fanatic named Gestapoko, which should tell you about eighty percent of what you ought to expect here. Anyway, our villains are particularly obsessed with first year student Mayumi Takahashi, and what better way to express their displeasure at her poor grades than to strap her to a giant swastika and cut her clothes off with throwing knives? Fortunately for Mayumi, Sparta Academy has just acquired a new hero, and if she's not necessarily the one it needs, she's certainly what it deserves: Kekko Kamen fights in boots, gloves, a mask with goggles and giant rabbit ears, and nothing else. As she cheerfully proclaims, nobody knows her face but the whole world knows her body, and she's not above suffocating her foes with her crotch if that's what the cause of love and justice demands.

Though, in one of those elements that resembles a joke without altogether becoming one, it's hard not to notice that, for all her birthday suit-clad heroics, Kekko Kamen only ever really seems to rescue Mayumi, and then only ever after she's been stripped down to her pants. You wonder if she's altogether thought this heroing business through. Nonetheless, our masked avenger is one of the most outright fun aspects of the four episodes, possessed of a beguiling innocence and lack of common sense which suggests that, yes, she did sit down and conclude that fighting crime in the buff is definitely the way to go. Which is all to the best given that the rest of the cast aren't half so engaging; the main villains, in particular, are visually intriguing but have one personality trait between them, if lecherousness counts as a personality trait. Indeed, it's only in the fourth and final part that Kekko Kamen gets to test her skills against a worthy foe, a fallen samurai with a penchant for snapping indecent Polaroids and, er, making umbrellas.

The animation is distinctly mediocre and some of the designs are flat-out horrible - there's something terribly wrong about Mayumi's eyes - though you probably won't be surprised to hear that a degree of loving attention goes into getting all those naked female bodies right. Weirdly, things improve markedly with the third episode, otherwise the least interesting due to a shift of focus onto Mayumi's infatuation with a beautiful transfer student, and then get worse again for the climax, which is in all other ways by far the best, thanks to being the first to spend time setting up a few real gags. At least the ludicrous theme tune is a pleasure, an energetic ode to its heroine's righteousness with some immensely dopey lyrics. But I dunno, add all of that up and the results still feel like awfully little for something trying so hard to be shocking. Ultimately, I guess that's the problem: cartoon nudity and crass gags are fine if that's your bag, but for me, the only thing that could turn those elements into genuine entertainment is some actual humour. As such, while Kekko Kamen is a tolerable distraction, it's easy to imagine a version that's greatly more enjoyable than what we get.

Cleopatra D.C., 1989, dir: Naoyuki Yoshinaga

Cleopatra D.C., 1989, dir: Naoyuki YoshinagaIt would be tough to write a review of Cleopatra D.C. that didn't degenerate into a list of all the ways in which it's a bit odd, and given that these reviews are a hobby and not a job, I guess there's no reason I should try! Though even then, there's the temptation to just say "Pretty much everything" and leave it there. The thing is, even the basic setup is strange. Our hero, she of the unlikely name Cleopatra Corns, is the leader of the Corns Group, which basically seems to own half the world, but only uses its corporate powers for good. This leaves young Cleo with trillions of dollars at her disposal and an excess of time on her hands, both of which she spends getting into adventures that mostly seem to revolve around a combination of damsels in distress and the shenanigans of another mega-corporation that devotes its resources solely to the dirtiest sorts of profit. So right there we already have a protagonist who's basically a gender-swapped Batman without the angst and flying rodent fetish.

Cleo also couldn't be much higher up in the one percent if she tried, and that would make her awfully hard to empathise with if she wasn't such a fun presence, bouncing from crisis to crisis with the giddy abandon of a sixteen year old who has all the money in the world. Her idea of problem solving, at one time or another, might involve guns, jet packs, ICBMs, parachuting from a fighter plane so that she can shoot at a space rocket with a missile launcher, or just plain buying up an entire firm. And this in turn leads to some exceedingly strange plots, which seem to be almost but not quite a pastiche of American action cinema - not quite because the show is ultimately too in love with that sort of preposterous excess to wish it any real harm. Indeed, it feels very much like what would happen if someone got the wildly wrong-headed idea that Roger Moore-era James Bond was a great template to emulate. And like so much of pre-twentieth century anime, you're sometimes left wondering who the audience is meant to be. Cleo is just enough like a real sixteen-year-old girl, hanging out with her ever-expanding band of female friends, to suggest that the answer is other teenage girls, but then there are sufficiently gratuitous shots of her naked butt to imply that, no, it was teenage boys after all, and presumably they're the ones who might be expected to get most out of its Moonraker-esque dementedness.

Add to that the character designs, which are relatively normal for the period when it comes to the men and very weird indeed when it comes to the women: Cleo and co look as if someone tried to funnel a contemporary anime aesthetic through the medium of Betty Boop, and thus become the only characters in all of anime to not only have eyes bigger than their mouths but to have eyelashes as big as their eyes. And while the animation is fair to middling, it's not the fair to middling of 1989; had I been guessing, I'd have pegged it at maybe a half decade later. Meanwhile, the jazzy score is a nice fit for the material, but just unusual enough to fit into Cleopatra D.C.'s generally off-kilter landscape. Heck, the show can't even get its episode structure right: the first two are standard length and the third clocks in at fifty minutes, so why not just split it in two? But Cleopatra D.C., like its titular protagonist, refuses to do anything in conventional fashion. Whether that makes the end result worthy of your time is, I suppose, another question. It's certainly fun, pleasant enough to look at, and full of energy and ideas - though it has to be said that the longest episode is the one that feels most conventional. Even then, though, if you're looking for something different, it's certainly an intriguing curio.

-oOo-

Dumb themes aside, there was kind of a serious purpose here: I definitely find it interesting that anime from three decades ago was happy to put female protagonists front and centre when there are still large portions of the US film and TV industry that consider the idea a bit of a gamble. But in honestly, I'm not sure this particular selection tells us a huge deal, though at least we touched on some of the major bases. And whatever else, I enjoyed the lot: even the basically rubbish Kekko Kamen was fun in its own weird way!

Next up: no stupid themes, hopefully.

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

Published on August 21, 2019 12:59

August 15, 2019

Kickstarting Wells

H. G. Wells is probably my favourite genre fiction author of all time, and The War of the Worlds is very possibly my favourite genre novel of all time, and I don't know that either of those facts quite explains why I felt the need - let alone the right! - to come up with a sequel to it. I mean, I'm not, as a rule, the sort of person who feels the urge to dabble in other writers' creations, or who wonders after every dangling thread in a story I love. What happens to the narrator of The War of the Worlds after the book ends? I mean, who cares, right?

H. G. Wells is probably my favourite genre fiction author of all time, and The War of the Worlds is very possibly my favourite genre novel of all time, and I don't know that either of those facts quite explains why I felt the need - let alone the right! - to come up with a sequel to it. I mean, I'm not, as a rule, the sort of person who feels the urge to dabble in other writers' creations, or who wonders after every dangling thread in a story I love. What happens to the narrator of The War of the Worlds after the book ends? I mean, who cares, right?The answer, apparently, is that I did, and enough so to write The Last of the Martians: what my good friend and trusted proof reader referred to as a Vietnam-era sequel to Well's classic, perhaps not entirely positively. The thing is, as powerful as the book as, as chilling as the Martians are, I can't be altogether comfortable with the concept of an enemy that's just so damn alien that there's no hope of ever rationalising with them: that sort of thinking has led us, as a species, into too many dark places over the millenia, and that's never been truer than now. So the story I wrote was an attempt to square that circle to my own satisfaction, while at the same time staying as true as I could to Wells's style and themes; no act of angry post-modernism this! I guess my goal was an epilogue to The War of the Worlds that Wells might conceivably have written if he'd come to think that maybe, just maybe, the Martians weren't all and every one of them quite that bad.

Why does any of this matter? Because I sold The Last of the Martians, that's why. And more to the point, because the two volume anthology of Wells-ian fiction that it's due to appear in is being kickstarted at this very moment, and if that kickstarter should fail to fund, my story - along with plenty of other dabblings in Wells's many worlds - might not ever see the light of day, which would suck, frankly! I don't think it's terribly likely to happen though, since the guys at Belanger Books know what they're about, and have been successfully putting out similar (though mostly Sherlock Holmes related until now) collections for a good long while. And at time of posting, this one's already almost hit its deadline with the better part of a month to go. So hey, don't fund it to help me out, fund it because it's an exciting project, and because you fancy a couple of volumes' worth of tales devoted to arguably the greatest science fiction writer ever to have lived. If that sounds at all appealing, you can find the link here.

Published on August 15, 2019 11:44

August 8, 2019

Film Ramble: Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 53

I guess lumping shorter titles together is a thing I'm doing now, possibly because there are just so many of them in the world of vintage anime that doing so makes sense. At any rate, this time we have the treat of four titles that were actually meant to be short, rather than cancelled after an episode or two, which is a definite plus. Indeed, three out of the four are actual movies, and I do kind of love the peculiar beast that is the vintage anime movie of less than an hour in length, the best examples of which tend to be miniature masterpieces of concise storytelling.

But is that what we're looking at this time around? Woo, perhaps! There are certainly a couple of major highlights to be found amid Spring and Chaos, Psychic Force, The Weathering Continent, and Judge...

Spring and Chaos, 1996, dir: Shôji Kawamori

Spring and Chaos, 1996, dir: Shôji Kawamori

Would that there were more films in the world like Spring and Chaos! Biopics of famous people are ten a penny, but often as not the goal is more to diminish than to understand, by presenting a greatest hits of the person they're lauding or by showing the rocky path to their most noteworthy accomplishment or by dumbing down their struggles to a point where they can be spoon fed to the viewer over the course of a couple of hours. But Spring and Chaos, in its attempts at offering an hour-long window into the life of poet and author Kenji Miyazawa (probably best known in the West for Night on the Galactic Railroad) refuses any of that. It isn't the story of Miyazawa's career in any meaningful sense, nor a beginner's guide to his achievements, and it certainly doesn't end on a triumphant note, since Miyazawa died young and unrecognised. And because it's told through animation - indeed, through some frequently gorgeous and risk-taking animation - it certainly doesn't confine itself to any prosaic reality, let alone to what may or may not really have happened.

Talking about what Spring and Chaos actually does do is more difficult. Its goals are numerous and contradictory, a celebration of the joy of creating but also a glimpse at its frustrations and even horrors. Writer / director Kawamori doesn't shy from the fact that Miyazawa was severely depressive, and perhaps mentally ill in wider ways; his hallucinations are presented as precisely that, and there's no suggestion that his creativity was a pleasant or even a healthy process. For every moment of rapture, there's another where he stalls agonisingly close to the idea he's seeking, or simply sees visions of corpses crawling out of the earth and trying to suck him down. Miyazawa is neither understood nor rewarded by his peers; in fact, the response to his art is an endless series of punishments and failures, mitigated in part, perhaps, by his moments of sheer pleasure, but never altogether. Whether he's wrangling with his loan shark father or trying to comfort his ailing sister or playing at school teacher or throwing himself into becoming a peasant farmer, he fails, and fails, and fails again.

Yet the result is as uplifting as it isn't. If there's a positive message here, it's that Miyazawa was true to himself, and while that lack of compromise was certainly bad for him, it left us with a legacy of great work that couldn't have come about otherwise. It helps, maybe, that all the characters are drawn as animals, mostly cats, adding a certain whimsy to moments that might otherwise be just too sour. More so, the very artistry of Spring and Chaos is uplifting, even when what it's depicting is heartbreaking. In fact, Kawamori's wisest choice in an exceedingly well written and directed film is to let the medium itself do the heavy lifting of comprehending Miyazawa's poetry: essentially, what we have is one art form celebrating another. Or rather, two art forms, since the use of music and the score itself are equally superlative.

Contrarily, you might argue that the biggest mistake Kawamori makes is leaning heavily into CG animation way back in 1996, when even relatively good CG was destined to stand out. However, as he notes in an interview on the otherwise sparse special edition disk, that was at least a conscious choice, and it's notable that all the obvious computer animation is confined to dream sequences and such, where its heightened unreality is a thematic fit. Frankly, it still ages the material in a manner that the lovely hand-drawn animation doesn't, yet it also allows for some astonishing images that might have been impossible to accomplish otherwise: the opening, in which a train pulls away from a station, only for the world to split beneath it, revealing a disturbing array of subterranean gears, is one striking example.

The upshot is a film that defies easy summary. Were it not for that dated CG, and perhaps if it were a dash longer than an hour, it would be easy to call it a masterpiece. Yet its apparent flaws are definitely part of what makes it so satisfying. It's easy to imagine a cleaner, tidier, and even more beautiful Spring and Chaos, but harder to conceive of one so brave and fascinating in its choices. It's not perfect, but it's certainly special, and deserves to be much more widely known than it is.

Psychic Force, 1998, dir: Tomio Yamauchi

Psychic Force, 1998, dir: Tomio Yamauchi

The truth is, I've nothing much to say about Psychic Force, try as I might: it really isn't very good, and it isn't very interesting either. In fact, my main observation was that it was released by obscure distributor Image Entertainment, who were also responsible for the incredibly shonky edition of Babel II I bought. Come to think of it, Psychic Force has a lot in common with Babel II, though the comparisons do it few favours. The latter was basically a mess, but at least had a couple of interesting ideas and a certain goofy charm; strip that away, cram the results into two OVA episodes with perhaps a tenth of the animation budget, and this would be what you had left. Though while Babel II was the sparsest DVD release I've ever seen, Psychic Force goes almost too far in the other direction, with a host of special features on a release that doesn't remotely deserve the attention.

Psychic Force is based on an arcade beat-em-up, which is rarely a good sign, but assuming there's a right way and a wrong way to go about adapting a game that involves nothing except characters hitting each other, this is a certainly a fine example of what not to do. For a start, there's very little fighting, and what there is isn't remotely exciting. Instead, we concentrate on the two main characters, which might have worked if there was a bit more to them, and if the focus had been even tighter: attempts to introduce the rest of the game's cast in brief snatches are merely confusing and annoying. And even the central arc expects us to believe that a friendship so powerful that our hero Burn Griffiths would devote years of his life to tracking down our sort-of-antagonist Keith Evans could be formed in the space of approximately five minutes. I swear I'm not making this up: Burn and Keith meet, hang out for a couple of scenes, Keith gets captured by the shadowy government agents who are chasing him, and then Burn spends literally years trying to track his vanished "friend" down. Seriously, Burn, this is why on-line dating exists.*

Also, Burn is a really distracting name to give someone. Especially when multiple scenes involve fire, and people being set on fire, and other people shouting "Burn" in a wholly inappropriate fashion.