Jeff Jarvis's Blog, page 10

June 1, 2020

Speech is not harmful: A lesson to be relearned

Be careful what you clamor for. You demand that platforms deal with harmful speech. Then he whose speech is thus affected unleashes the dogs of Trump. They harass the platform and its employees for exercising their freedom of speech. They threaten to limit freedom of expression for everyone on that platform and the net — including you.

Thus efforts to control noxious, right-wing speech have backfired as the right-wing exploits every tool used against them. The weapons Trump brandishes — regulating social platforms, limiting or repealing Section 230, redirecting government advertising, blaming algorithmic “bias,” demanding “neutrality,” defining the net as media and platforms as publishers — are things proposed by those who want to limit harmful speech online. In his so-called executive order, the Troll in Chief is using them all for his ends. Have we learned nothing from bad actors online— that every function, every lever, every precedent that can be gamed and exploited by them will be? Now Section 230, our best protection of freedom of expression on the internet, is in peril.

The more I study net regulation, the more of a free-speech absolutist I become. To think that speech is harmful is almost inevitably a third-person effect: believing that everyone else — but not you — is vulnerable to bad words and ideas and that protecting them from it will cure their ignorance. There is but one cure for ignorance: education. The goal of education is to prepare the mind to wrestle with lies and hatred and idiocy … and win.

It is worthwhile to remind us of that very argument made long ago by Franklin, Milton, and Wilkes. Sherman, set the Wayback Machine.

In 1731 Benjamin Franklin was fed up with people complaining about what came off his press — not just in his newspaper, but even in advertisements — and so he wrote an Apology for Printers, which was nothing of the sort. I’m going to take the heart of that essay and substitute modern words like platform and social media for old-fashioned words like printer to make my point: that Franklin’s point still stands. Let me be clear: I do not believe the internet is a medium. It is a platform, a platform for facts and opinions and conversation about them. That is how Franklin viewed his press, as a platform. He wrote:

I request all who are angry with me on the Account of serving things they don’t like, calmly to consider these following Particulars

1. That the Opinions of Men are almost as various as their Faces; an Observation general enough to become a common Proverb, So many Men so many Minds.

2. That the Business of Social Media has chiefly to do with Mens Opinions; most things that are posted tending to promote some, or oppose others….

4. That it is as unreasonable in any one Man or Set of Men to expect to be pleas’d with every thing that is posted , as to think that nobody ought to be pleas’d but themselves.

5. Technologists are educated in the Belief, that when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter: Hence they chearfully serve all contending Twitter or Facebook users , without regarding on which side they are of the Question in Dispute.

6. Being thus continually employ’d in serving all Parties, Platforms naturally acquire a vast Unconcernedness as to the right or wrong Opinions contain’d in what they serve ; regarding it only as the Matter of their daily labour: They serve things full of Spleen and Animosity, with the utmost Calmness and Indifference, and without the least Ill-will to the Persons reflected on; who nevertheless unjustly think the Platform as much their Enemy as the Tweeter , and join both together in their Resentment.

7. That it is unreasonable to imagine Platforms approve of every thing they serve , and to censure them on any particular thing accordingly; since in the way of their Business they serve such great variety of things opposite and contradictory. It is likewise as unreasonable what some assert, That Platforms ought not to serve any Thing but what they approve; since if all of that Business should make such a Resolution, and abide by it, an End would thereby be put to Free Tweeting and Facebooking and Instagramming and TikToking and YouTubing , and the World would afterwards have nothing to read but what happen’d to be the Opinions of the Technologists .

8. That if all Platforms were determin’d not to serve any thing till they were sure it would offend no body, there would be very little posted .

9. That if they sometimes serve vicious or silly things not worth reading, it may not be because they approve such things themselves, but because the People are so viciously and corruptly educated that good things are not encouraged….

“Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.” — John Milton, the Areopagitica

In 1638 Milton visited Gilileo, who was under house arrest for what authorities decreed were his dangerous ideas and harmful speech. Milton paid tribute to Galileo, including him in Paradise Lost, and the visit helped inspire the Areopagitica, Milton’s 1644 polemic against the licensing of books in England and in defense of freedom of expression.

The abolition of the Star Chamber in 1637 had led to the effective end of censorship and a flowering of publishing — too much publishing for the taste of authorities. In 1643, Parliament passed a Licensing Order “for suppressing the great late abuses and frequent disorders in Printing many false, forged, scandalous, seditious, libellous, and unlicensed Papers, Pamphlets, and Books to the great defamation of Religion and Government.” Might as well add tweets and Facebook comments to the list. Parliament argued, as unfortunately some do today, that there was too much speech. Bad actors, they said, “have taken upon them to set up sundry private Printing Presses in corners, and to print, vend, publish, and disperse books, pamphlets and papers, in such multitudes, that no industry could be sufficient to discover or bring to punishment all the several abounding Delinquents.”

Speech scaled and control did not. In England, the Stationers Company — a private, industry organization for printers — had been deputized to regulate this speech, just as Twitter and Facebook are expected to do today. The Order decreed no publication could be printed unless it was first licensed.

In the Areopagitica Milton rose up in righteous, eloquent anger in defense of speech, of debate, of learning, and of this less-than-200-year-old art of printing.

“For books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life … of that living intellect that bred them.” Thus, Milton said, one might as well “kill a man as kill a good book…. he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God.”

But what of bad books? Well, who is to decide the difference? A Star Chamber? The Stationers Company? Twitter? Facebook’s Oversight Board? The White House? Courts? Or readers? “Read any books whatever come to thy hands, for thou art sufficient both to judge aright and to examine each matter.” That is God speaking to Pope Dionysius of Alexandria in 240 A.D., according to Milton.

We learn by testing ourselves, Milton argues. “That which purifies us is trial and trial is by what is contrary…. Our faith and knowledge thrives by exercise.” He acknowledges the authorities’ fears that bad speech is “the infection that may spread” — just what we hold this fear today about internet disinformation. But he contends that “evil manners are as perfectly learned without books” and so eliminating bad books will not staunch the infection. So: “A fool will be a fool with the best book, yea or without a book; there is no reason that we should deprive a wise man of any advantage to his wisdom, while we seek to restrain from a fool, that which being restrained will be no hindrance to his folly.”

This is Milton’s article of faith: “See the ingenuity of Truth, who, when she gets a free and willing hand, opens herself faster than the pace of … discourse can overtake her.” And: “And though the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously, by licensing and prohibiting, to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple.”

Yet he adds a caution: ‘Truth and understanding are not such wares as to be monopolized and traded in by tickets and statutes and standards. We must not think to make a staple commodity of all the knowledge in the land, to mark and license it like our broadcloth and our woolpacks.” Truth is not a product to be packaged. It is a choice.

He makes two key arguments: that citizens need to learn by facing and rejecting sin (“When God gave him reason,” Milton says of Adam, “he gave him freedom to choose, for reason is but choosing”) and that no small group of men is capable of making decisions to protect citizens from those choices: “Who shall regulate all the mixed conversation of our youth, male and female together, as is the fashion of this country? Who shall still appoint what shall be discoursed, what presumed, and no further? Lastly, who shall forbid and separate all idle resort, all evil company?”

Milton warned of the precedents licensing would set. If we license printing, must we not then license dancing and lutes and lyrics and visitors who bring ideas? And what does Adam teach us about forbidden fruit? “The punishing of wits enhances their authority… This Order, therefore, may provide a nursing-mother to sects.” To forbid it is to spread it; that is another lesson of disinformation on the net.

Milton, like Franklin, recognizes the value of the public conversation: “Where there is much desire to learn, there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions; for opinion in good men is but knowledge in the making.” I cannot help but also call on James Carey, who said: “Republics require conversation, often cacophonous conversation, for they should be noisy places.” In the development of the net I have come to see that what we are witnessing is a society relearning how to have a conversation with itself.

But what of nasty, hateful conversations with trolls? Should we not be protected from them?

I give you John Wilkes, the urtroll, who is also, in the title of Arthur H. Cash’s biography, The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty. Wilkes was, by every description, unattractive, a cur, a libertine, a smartass. He feuded with the prime minister, Lord Bute, and published anonymously a newspaper that mocked him, which “proceeded with an acrimony, a spirit, and a licentiousness unheared [sic] of before even in this country,” said Horace Walpole.

In the first issue of the North Briton, Wilkes called a free press “the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country … the terror of all bad ministers.” Says Cash: “Wilkes was in constant danger of having his ironies taken literally by humorless or stupid men.” Indeed, Wilkes and his printers were arrested and his papers seized and there were attempts to rob him of his seat in Parliament.

But he persevered and in the process, according to Cash, set many legal precedents: the end of general warrants, the establishment of a right to privacy, an enhanced right to sue the government for false arrest, in addition to a right to transparency of Parliament and freedom of the press. Wilkes did it by nastily trolling, because that was the power he had at hand. Wilkes is a hero of mine, not as a troll, of course, but as a defender of liberty.

Larry Kramer, who died this week, was also a hero of mine. He was also a troll, a power he used when it was all he had to save lives at the start of the AIDS epidemic. Hear Dr. Anthony Fauci about their relationship:

“How did I meet Larry? He called me a murderer and an incompetent idiot on the front page of the San Francisco Examiner magazine.” …

Addressing Dr. Fauci in the letter, Mr. Kramer wrote: “Your refusal to hear the screams of AIDS activists early in the crisis resulted in the deaths of thousands of Queers. Your present inaction is causing today’s increase in HIV infection outside of the Queer community.”

“I thought, ‘This guy, I need to reach out to him,’” Dr. Fauci recalled. “So I did, and we started talking. We realized we had things in common.”

How better to tell the story of the power of listening?

So what speech is it you want to control? Hate? I hate our president and say so. Lies? Who wants an official truth but the officials who set it? Trolling? We risk losing the righteous power of Wilkes and Kramer and the opportunity to learn from them.

Donald Trump is a hateful, lying troll. So what should Twitter do with him? Whatever it wants to. That is the point. That is its right as a private entity in the United States. That is its freedom of expression. It has the freedom to do nothing, to delete his tweets, to add fact checks and warnings to them, to not promote them. I think it is now doing the right thing.

Above all, what Facebook and Twitter and every technology company should be doing is deciding why they exist. I have complained that in establishing its Oversight Board, Facebook has not set a North Star, a raison d’être for the platform. Why does it exist? What behavior on it is beneficial and welcome and what is not, for what reason? They are asking the 20 wise members of the Oversight Board — its Stationers Company — to enforce a set of statutes without a Constitution. Twitter, by its actions, is beginning to write its Constitution, to decide what is acceptable and not and why. Those are their decisions to make.

So what of Trump’s people, those whom he eggs on? Well, what are the characteristics we know of his so-called base: they are uneducated, white males. White, male entitlement matters. But uneducated, that is the key. To update Milton as I updated Franklin: “A fool will be a fool with the best Twitter, yea or without Twitter.”

If we try to use official power to restrain speech on social media, we give fools the power to restrain wisdom there. That is what Trump is trying to do. We must recognize it for what it is: not a legal but a political ploy, an unconstitutional one, also unAmerican. We must fight to protect the freedom of expression, even for fools, so we protect our own. We must fight for the net.

The post Speech is not harmful: A lesson to be relearned appeared first on BuzzMachine.

May 28, 2020

Sprouts from the ashes

Our house was already on fire; COVID threw gunpowder on the flames. In this piece for Tortoise, I surveyed the damage to our field. Now I will look at some hopeful sprouts rising from the ashes.

First, to be clear: There is no messiah that will save us overnight; our messiahs have all been false. We will not — and should not — return to journalism as it was; we must not lose this opportunity to rethink what journalism can be. Though I want to give them the benefit of hope, I fear the innovation required will not often come from incumbents as they are overwhelmed trying to save the business that was; but I still wish they’d try. The new journalism will not arrive big and fully birthed; it will grow from many small seedlings, many experiments, thus many failures. Patience is required.

Here I’d like to report on conversations I’ve had with three local examples I’m impressed with: Canada’s Village Media, Innocode’s transparency app, and a German paper’s experiment with delivery for stores.

Talk with Google’s senior VP for news, Richard Gingras, about local news (as I will be on June 10) and he will tell you that Jeff Elgie has the answer. I agree. He has a very good answer.

Elgie’s Village Media has the model of simple local reporting for three dozen towns of 50,000 to 150,000, some of its outlets owned by the Sault St. Marie-based company, some franchised to partners (including a few experiments underwritten by Google with McClatchy in Youngstown, Ohio, and with Archant in the UK). In Elgie’s model, the ideal town is a bit isolated, the kind of place where people are born, live, and work without commuting to the big city. Village Media isn’t perfect for tiny, uh, villages (though it has a town of 10,000 as a satellite to a neighboring market) or suburbs or big cities, at least not yet. Elgie says in his best markets residents have a local news habit; it’s easier to start a Village Media site in a town with competition or in which the paper just died, rather in one that has been a news desert.

Village Media sites provide just the value you’d expect from a local newspaper a few decades ago: town council doings, schools, crime, new businesses; it’s comforting in its familiarity. Each site has a handful of reporters covering what matters and Elgie firmly believes they should not waste time rewriting press releases; their sites post them, properly labeled. Village media provides the model and the technology.

Village Media sites are supported by — get ready for it — local advertising. It has not died. Elgie has creative offerings for local merchants beyond standard ad units, video, and sponsored content. There is directory advertising that is self-published by the local merchants, and “sponsored journalism.” That’s not as fearsome as it sounds. It’s underwriting as engaged in by public-radio stations: A sponsor is able to take credit for making it possible to offer coverage of, say, volunteerism or high-school sports or local arts. Village Media also has some programmatic advertising and — like McClatchy, Advance, and Stat — has instituted voluntary payment (read: contributions) in this crisis.

Now hold onto your hat: Even in the COVID crisis, Village Media’s revenue is *up* this April over last by more than a third, not counting growth in franchise fees.

Yes, Village Media sites lost advertisers in the shutdown. But it worked hard (like the German site I’ll mention below) to help them get customers. A major auto dealer that was ready to cancel has ended up spending more. Cities are advertising.

There are other, similar models out there. Patch in the U.S. spread like kudzu into 900 towns, blew up, and rose again from its own ashes, smaller. My area in New Jersey has TAPinto sites as well as independent blogs. In Geeks Bearing Gifts I extolled the hyperlocal blog as a building block of a new news ecosystem and then I confessed my over-enthusiasm, though there are still lots of great single-proprietor blogs serving towns. Every commentator about local news — and there are more commentators about it than reporters in it these days — is quick to complain that any model I propose doesn’t scale. Well, nothing will scale in an instant; that was Patch’s problem: thinking it could. Local is going to be spotty. For Village Media, the challenge is identifying and training the perfect local publishers; as a school, I’m drawn to help.

I’ve long taught our entrepreneurial students the C-A-R rule of media businesses: They must first build a critical mass of content before they can attract a critical mass of audience before they can get a critical mass of revenue. This meansan enterprise of the size of Village Media’s requires a low six-figure investment to get to break-even. Given that the model is proven and the revenue and margins are enviable, I see no reason that capital cannot be raised as loans to build new outlets all over the map. Think of it as a burger franchise and it makes financial sense.

What about tiny burgs that don’t fit the Village Media model? On my last trip outside New York, I got to sit down with Richard Anderson, the founder of Village Soup (no relation) in Maine and a great pioneer in online local journalism. He had thriving local digital sites and then unfortunately bought the local newspapers just before the crash and ended up selling the business. But he remains an innovator, working on how to serve towns’ needs for local government transparency and accountability without wasting time and resources on distractions. Anderson is working on an exciting idea I’ll tell you about another day, when he’s ready.

Anderson and I are inspired by a 2018 paper by Pengjie Gao, et al, that contends: “Following a newspaper closure, we find municipal borrowing costs increase by 5 to 11 basis points in the long run…. The loss of monitoring that results from newspaper closures is associated with increased government inefficiencies.” That is, transparency is good for local towns, schools, businesses, and taxpayers. In my state we have something called Sustainable Jersey, which certifies towns on a number of criteria — including public information and engagement — and they compete to improve.

This inspired another thought: call it transparency-as-a-service. What if transparency services offered a start — just a start — on the way to a healthier local information ecosystem? What if that could be a business? What if the client is the town? Is that a conflict of interest? Sure. So is advertising. Bear in mind that Benjamin Franklin was not only the publisher of a newspaper in Philadelphia but also the official printer of Pennsylvania and the postmaster at the same time. If Ben could manage it, we can.

I was sharing this thought with a Scandinavian media executive I respect and he told me I had to talk with Morten Holst of Innocode, which provides technology for many media companies. I mentioned my thoughts on transparency-as-a-service to Holst and he showed me the Sandefjord Citizen app they’ve already built. The client is the local government. The users are a third of the population of the town. The product is local data. With the app, users can sign up for alerts when building permits are filed (the town would rather people raise objections before v. after it is issued), get data on water temperature and snow plowing (it’s Norway), and send out messages on behalf of their local clubs and organizations.

No one would say such data transparency is sufficient to assure local government accountability. Journalism is needed atop this data. The Citizen app is just one piece of an impressive, larger local strategy Innocode has. In any case, why waste journalists’ time rewriting press releases about snow plowing? Why not, too, follow the lead of Chicago’s City Bureau and make citizens collaborators in covering meetings and gathering data? The journalists should devote their time to true accountability journalism, not just filling space. The more informed and engaged citizens are in their local government, the better for journalism, the better for the town.

My point here is that we need to cut journalism up into component parts so we can start smaller. As I said in this post, one of my students argued that when faced with building from ground up, one must choose whether to build transparency or service journalism and I would add community. You want to end up with all three, but you need to start somewhere. The Citizen app is an example.

Finally a note on local business and community. This headline in Germany’s Die Zeit struck me:

Translated: “The newspaper now brings beer. Many local papers are fighting to survive. But in the middle of the pandemic, the Mindener Tageblatt had an idea.”

I emailed the publisher, Carsten Lohmann, to learn more. What impressed me is that he empathized with the needs of his local advertisers and their customers and brought to bear what he could: his own newspaper delivery staff. The company had already decided to take a cost center — delivery — and turn it into a revenue stream. Then came COVID. Lohmann told me:

With our daily newspaper we reach about 45% of all households in the distribution area and pass through about 70% of all mailboxes. So it made sense to take other products with us on this route.

Since we have to collect business mail from our customers during the day and also deliver it for our printing plant and office supplier (a local Staples), we decided to offer this service to external customers as well.

In this respect, our logistics department is certainly already experienced. Nevertheless the project is a challenge. For example, we have invested in a new logistics software.

They have been delivering beer (it’s Germany), plus about 80 pair of shoes so far, and office supplies. Will this make him rich? Is it the elusive messiah? Of course not.

It’s not gonna make us a fortune. But it should and does help us to share our own costs with external customers and to intensify contacts with local retailers on several levels — or even to establish them for the first time. At kauflokal-minden.de(buy local — Minden) companies have registered with which we have had no business contacts so far.

This is not the only line extension the paper has developed. In 2003, it founded MR-Biketours and is now the largest provider of guided motorcycle tours to the U.S. By the way, when I told students in our News Innovation and Leadership program at Newmark about the Minden paper, my colleague Anita Zielina said the paper she once worked for in Austria, Der Standard, bought a local bread company and offered daily delivery of papers and rolls. Who wouldn’t want a nice Zimtschnecke with the news?

Many years ago, when I was still consulting, I set up a meeting with eBay and PalPal (they were still together) to investigate whether local newspapers could help local businesses sell online and deliver locally to compete with Amazon. The eBay executive said the problem was that local stores did not generally have inventory digitized, so it could not be presented for sale online. I wrote a business plan for a stores’ equivalent of OpenTable, which had to build a system for restaurants to manage reservations so those reservations could be offered online. It almost got investment and a team but then didn’t. More recently, at the Newmark J-School, we started a professional community of practice for ecommerce with a not-so-hidden agenda to convince and help publishers to open online stores (à la Wirecutter) to build a new revenue stream and a new set of skills around individualized user data. The group convinced one company to do this and it gained a new revenue stream of a few million dollars.

My point is that we need to build new journalistic enterprises, new models, new services, and new revenue in small ways. This is why I like the dialog-driven journalism of Spaceship Media, the collaborative journalism of Chicago’s City Bureau, the answers and advocacy that come from Detroit’s Outlier, the listening inherent in Tortoise’s Thinkins, the power-sharing of The City’s open newsrooms, as well as innovation from the incumbents: Advance’s texting platform Subtext; McClatchy’s and Archants experiments above, and service journalism from the Arizona Daily Star’s This is Tucson. They build a piece at a time.

At Newmark, we just announced that we are also thinking small to train individual, resilient journalists in our new Entrepreneurial Journalism program. It will prepare journalists to serve passionate communities by making email newsletters, videos, events, sites, texting services, books, and more — and to support their work by making money via Medium, YouTube, Patreon, book publishers, events, and so on. My colleague Jeremy Caplan will head the program.

None of these journalists is likely to get venture-capital funding and return 100x. None of them will instantly serve every town in America. None of them will solve all of journalism’s woes overnight. None of them is a messiah. But any of them could serve a town’s transparency needs or bring together a community to share with each other or find creative ways to earn money by serving local merchants. Any of them could rebuild journalism from the ashes as small sprouts. That’s what it’s going to take, when the fire is out.

The post Sprouts from the ashes appeared first on BuzzMachine.

May 11, 2020

A conversation with Steak-umm’s Twitter voice, Nathan Allebach

I just had a delightful conversation with the voice behind Steak-umm’s Twitter, Nathan Allebach, who — from the platform of a frozen meat brand — has brought sanity, rationality, and empathy to the discussion online in the midst of this pandemic.

I did this mainly for journalism students and journalists, for there is much to learn from Nathan about listening, about bringing value to conversation, about community, about empathy, and about authenticity and transparency. In the end, when I ask him whether he would think of being a journalist, he said he might be too radical in his view of journalism and marketing; I told him he’s made for our Social Journalism program at the Newmark J-School.

Nathan talks about how he approaches communities on Twitter, how he built trust between himself and his client and their brand and the public, how he has to navigate the delicate line between being himself and being the voice of a brand, and a little about himself as an autodidact nerd and musician.

The post A conversation with Steak-umm’s Twitter voice, Nathan Allebach appeared first on BuzzMachine.

April 22, 2020

The open information ecosystem

Media are no longer the deliverers of information. The information has already been delivered. So the question now for journalists is how — and whether — we add value to that stream of information.

In this matter, as in our current crisis, we have much to learn from medicine.

In microcosm, the impact of the new, open information ecosystem is evident in the COVID-19 pandemic as scientists grapple with an avalanche of brand new research papers, which appear — prior to peer review and publication — on so-called preprint servers, followed by much expert discussion on social media. Note that the servers carry the important caveat that their contents “should not be reported in news media as established information.”

Almost to a scientist, the experts I’ve been following on my COVID Twitter list welcome this new availability of open information, for it gives them more data more quickly with more opportunity to discuss the quality and importance of researchers’ findings with their colleagues — and often to provide explanation and context for the public. So far, I’ve seen only one scientist suggest putting preprints behind a wall — and then I saw other scientists argue the point.

Clearly, low-quality information presents a problem. There is the case of the hydroxychloroquine paper with a tiny number of patients and no controls that got into the head and out of the mouth of Donald Trump. But many, many scientists objected to and pointed to the problems with that paper, as they should. The weakness in that chain, as in many, is Trump.

A better example of what’s occurring today is the reaction to a SARS-CoV2 antibody study in Santa Clara County, California — which matters because we still do not know how reliable our counts of infected patients is. I am not nearly qualified to understand it. But as soon as the paper was posted, I saw a string of thoughtful, informed threads from scientists in the field pointing out issues with the study: See Drs. Natalie Dean, Howard Forman, Trevor Bedford, John Cherian, and grateful reaction to all of them from a scientist all the others respect, Dr. Marc Lipsitch. All of them responded within one day. That is peer review at the speed of the internet.

The tone of their criticism is respectful and backed up with reasoning and citations. Because science. One example, about the paper’s conclusion regarding the infection fatality rate (IFR):

This paper has NOT been peer-reviewed. The data seem robust; the analysis seems appropriate (leave to others to judge); the conclusions re: IFR are a bridge too far.

— (((Howard Forman))) (@thehowie) April 18, 2020

Credit to @medrxivpreprint for providing access to preprints.

2/xhttps://t.co/TuAVdVyYey

To make this open, rapid system of information functional, scientists are, with admirable dispatch, adapting new methods and models, which brings many requirements:

First: The information needs to be open, of course, and that is happening as SARS-CoV2 papers are being published by journals outside their high and pricey paywalls. Preprint servers are free. Note also that the EU just announced the establishment of a Europe-wide platform for open sharing of both papers and data on the pandemic. #OpenScience is a movement.

Second: There needs to be some means to sort and discover all this work. Seeing that need, up popped this index to preprints that clusters and maps them around topics; and the Covid Open Research Dataset, which tries to provide organization; and a writer who summarizes 87 pieces of original research published in a week. The volume is heaven-sent but crushing. As a delightfully wry medical blogger named Richard Lehman writes: “Five weeks ago, when I began writing these reviews, everyone was aghast at the challenge of covid-19 and thrilled how it was dynamizing all the usual slow processes of medical knowledge exchange. In the intervening century, we have become more weary and circumspect.”

Secondly a lot of papers are coming out, I mean a lot ! To date > 4000 papers from Pubmed search and 1885 #preprint on #bioRxiv and #medRxiv on a virus we knew nothing about 5 months ago is truly incredible. So there are a lot of research going on and it is a challenge to keep up pic.twitter.com/ywoLcHRdd1

— Dr Gaetan Burgio, MD, PhD. (@GaetanBurgio) April 19, 2020

Third: Of course, there need to be mechanisms to review and monitor quality of the papers. That’s happening almost instantaneously through medical social media, as illustrated above. And there are papers about the papers, cited by Dr. Gaetan Burgio in the thread above. One analyzes the 239 papers on COVID-19 released in the first 30 days of the crisis, separating research science, basic science, and clinical reports. “It is very much like everyone would like to have a go at #COVID19 & we end up with a massive ‘publication pollution,’” Burgio tweets. Some are good, he says, some atrocious; some come from relevant researchers, some not. That is why the swift and clear peer review and some level of vetting is important. And that leads to…

Fourth: There needs to be a means for experts to judge experts, for credentialing and review of those rendering judgment of the research. That, too, is happening in the public conversation. In the process of maintaining my own COVID Twitter list of epidemiologists, virologists, infectious-disease physicians, and researchers, it becomes clear by their citations and comments whom they respect. It also becomes clear whom many respect less. This is the question: Whom do you trust? On what basis? For which questions?

But when the question moves from science to personality, things can get uneasy. One case: Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding has been getting much Twitter traffic and TV airtime for his tweets. Some scientists made a point of telling me that he does not have credentials and experience as relevant as others’. Then followed a deftly critical Chronicle of Higher Education piece about him, which he in a DM to me called a hit piece. I’ll leave this to others, more qualified than I am, to judge.

True, there is an ever-present risk of credentialed disciplines endorsing only the members of their tribe. But that credentialing is an institution that has long been central to the academe and science, necessary to certify credibility in an educated and enlightened society. The granting of degrees and appointments is the best system we have for determining expertise. Especially in these anti-intellectual, science-denying, cognition-impaired times, it is vital that we maintain and support it.

I have been arguing to editors, producers, bookers, and reporters that they should be doing a better job asking the right questions of the most relevant and experienced experts — not, for example, asking a spine surgeon about virology, not giving op-ed space to armchair epidemiologists. This means that journalists — and internet platforms, too — need to make judgments about who to quote and promote and who not to. To quote my friend Siva Vaidhyanathan: “I wish journalists were more discriminating when assessing expertise worthy of informing the public. Knowing academic ranks, positions, journals would help. More scientific expertise in the newsroom would be best.” This gets us to:

Fifth: Both scientists and journalists must do a better job explaining science. I’m working with Connie Moon Sehat in our NewsQ project (funded — full disclosure — by Facebook) to formulate definitions of quality in news, starting with science news, so those definitions can be used by platforms to make better judgments in their promotion of content. This will end up with measurable standards — for example, whether reporting on a preprint includes views from multiple scientists who are not its authors and what the credentials of the quoted experts are.

I hear scientists worry about how well they communicate with the public. That’s why they are sent to take training in science communication (“scicomm”). But I tell them it’s not the scientists who should change, but the journalists, who must learn how to grapple with open information themselves.

Before I explore some of the lessons for journalism and media, let me make clear that — as ever — none of this is new. In science, says a paper by Mark Hooper, the accepted historical narrative has been that peer review began with the first science journals in 1665. Or when the Royal Society “published a collection of refereed medical articles for the first time” in 1731. Or when the Royal Society formalized the process of using independent referees in 1832. Or during the Cold War when peer review became “a requirement for scientific legitimacy.” The term “peer review” was not used until the 1960s and 1970s.

But Hooper contends that the practice of peer review — which he defines as “1) organized systems for facilitating review by peers; 2) in the context of publishing practices; 3) to improve academic works; 4) to provide quality control for academic works” — began much, much earlier. Cicero received editorial review from Atticus, his publisher and editor, in the first century B.C. (A lovely full circle, as Petrarch’s rediscovery of Cicero’s letters to Atticus is marked as a foundational moment of the Renaissance.) Scholia — “comments inscribed in the margins of ancient and medieval works” — were so valuable that scribes made margins larger to accommodate them. Pre-publication censorship in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries was also a form of academic review, Hooper says.

All of which is to say that every form of media is an adaptation of another. Peer review by experts has been a need long fulfilled by different, available means. As I wrote the other day, news was poetry, song, official decrees, cheap broadsides, single-subject pamphlets, and handwritten newsletters before it became newspapers.

So what does this open information ecosystem portend for news? Well, again, we don’t deliver news or information anymore. It is delivered already: via blogs, social media, direct connection from officialdom and companies to the public, scientific papers, open databases, and means yet unimagined in the vast public conversation opened up by the net. Nobody depends on us to bring them information. We are no longer the deliverer or the gatekeeper.

But this open information ecosystem does bring many demands — just as that in medicine — and therein lie many opportunities.

First: How do we help make information open, breaking the seals of governments and companies and other information sources to the public? How do we aid transparency? Maybe that’s one of our new jobs: transparency-as-a-service (more on that idea another day). And we must ask: Can we function in an open information ecosystem when our information is ever-more frequently closed behind paywalls?

Second: How do we make information more discoverable and organized? Google, of course, did that with search, but that’s only a beginning, as I’m sure Google itself would agree: a miraculous but still-crude layer of automated organization it is constantly improving. Who will master the challenge of sorting wheat?

Third: How do we create mechanisms to review the credibility and quality of information and disinformation? Note how Medium is, to its credit, grappling with making judgments on the credibility of COVID-19 content while other platforms all but throw up their hands at the impossibility of judgment at scale. Ultimately, this task will depend upon:

Fourth: How do we judge the expertise of those we call upon for judgment?

Fifth: How do we amplify their expertise, adding context, explanation, verification, and perspective in the public conversation?

Expertise is key. The problem here is that experts are much easier to find, certify, and judge in medicine than in other fields. Because science. Is there such a thing as an expert in politics? Half the world thinks it’s them. Another problem is that academically certified experts are becoming scarcer — and less heed is paid to them — in this era than elevates idiocy. One more problem is the methodology of journalism, which is built to regurgitate events and opinions around those already in power without accountability for outcomes. Imagine — as one of my former students, Elisabetta Tola, is— journalism in the scientific method, beginning with a hypothesis, seeking data to test it, calling on experts to challenge it, and recognizing — as scientists do and journalists do not — that knowledge does not come in the form of a final word but instead as a process, a conversation.

It is no longer our job to tell finished stories. In the economic aftermath of this crisis, that is a legacy luxury that will die along with the old business models that supported it. Get over it. Adapt. Survive by adding value to the free flow of information in the open ecosystem that is our new normal. Or die.

UPDATE: The day after writing this came an all-too-perfect example of what I’m trying to warn against in this post. The New York Times gave space to a controversial and contrarian preprint without getting differing views from scientists, without providing the context that this scientist’s views have been used by the it’s-just-flu, open-up-now COVID deniers. Shameful editing. In my thread, see also the last link to an example of good reporting from the San Jose Mercury News.

April 8, 2020

COVID Journalism: Episodes 1-4

UPDATE: Here is a fourth episode of my series of interviews with the experts of COVID.

I spoke with the amazing Dr. Emma Hodcroft, a phylogeneticist (which she will explain) at the University of Basel, who co-developed the Nextstrain project, a herculean effort to track, so far, 5,000 strains of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as it travels across the world. We talked about lessons from that project; about good and bad journalism about the pandemic; about how journalists should responsibly report on debate and discussion in the medical community that occurs in preprint papers and Twitter; about about her own role in this extraordinary event. She is an excellent explainer on social media, and here:

EARLIER EPISODES: I have been interviewing experts in COVID-19 to give journalists advice about how to cover the crisis.

In our Social Journalism program at the Newmark Journalism School, we believe community journalism must start with listening to the community. Well, science journalism must start with listening to the scientists. This is why I have been maintaining a COVID Twitter list of more than 500 credentialed, relevant experts.

So I have spoken so far with an epidemiologist, an infectious disease expert, and a virologist. I will continue with other experts in more disciplines. Here are the first three interviews:

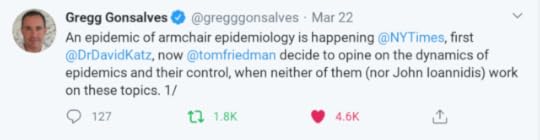

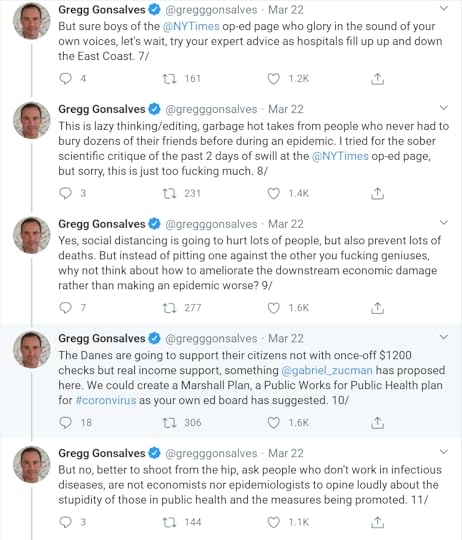

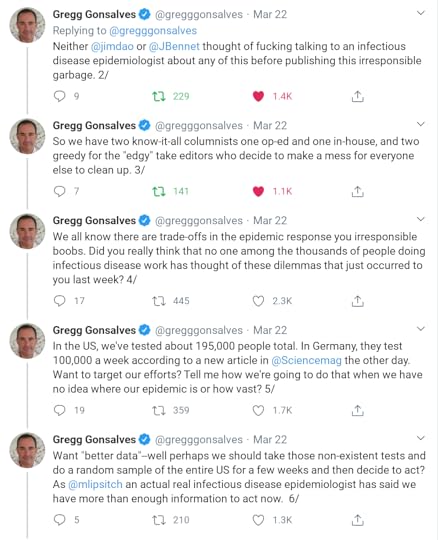

Episode 1: Yale epidemiologist Dr. Gregg Gonsalves

I start with epidemiologist Dr. Gregg Gonsalves of Yale, who has been a trenchant critic of coverage, especially of armchair epidemiology from the op-ed pages of The New York Times. He is also a strong voice in my COVID Twitter list of more than 500 experts.

Dr. Gonsalves dissects what was wrong with a contrarian Times op-ed arguing that the cure might be worse than the disease — something we’ve heard since from Trump and company. The Times’ mistake was in giving space to a contrarian rather than an expert, succumbing to our professional weakness for false balance and controversy, even if manufactured. We discuss the challenges of journalists covering modeling and the politicization of research. Importantly, he gives journalists advice about what they should be covering: not only the medical scandal of the century in the Trump administration’s failures in this epidemic, but also what will come next. He says much of the work to come will fall on local journalists (at a time when local journalism is suffering and years past the departure of most local science reporters).

Episode 2: Infectious diseases expert and ebola veteran Dr. Krutika Kuppalli

Dr. Krutika Kuppalli is an expert in infectious diseases with experience in HIV and Ebola. She is vice chair of the Global Health Committee at the Infectious Diseases Society of America and a Biosecurity Fellow at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. She supervised treatment at an Ebola unit in Sierra Leone in the 2014 outbreak and has also worked in Ethiopia, India, Uganda, and Haiti.

I asked her advice on how to cover the transmission of the virus; what to look for and when to look for it in news about the development of therapeutics and vaccines; and — importantly — how bring attention to what I believe is the great uncovered story of this crisis: inequality and its impact on poor and vulnerable communities in the U.S. and worldwide. Dr. Kuppalli emphasized both her concern for the impact the pandemic will have on poor nations — and what we can learn from them, considering that nations like Sierra Leone faced Ebola without the money we in America can throw at problems. We also spoke about the psychological toll treating the disease has to be having on our health care workers. Finally, she urges reporters, editors, and bookers to check the credentials of the sources you call to make sure they are experts with experience, not people from other fields with opinions. Now more than ever, expertise matters. We must amplify it.

Episode 3: Columbia virologist Dr. Angela Rasmussen

Now I interview a virologist, Dr. Angela Rasmussen of Columbia’s School of Public Health, to get her help for journalists covering the COVID-19 crisis. She and I talk about what media are doing right and wrong; about the need for journalists — reporters, editors, bookers — to find the appropriate, relevant, credentialed experts and to take advantage of the tremendous diversity among them; about how she works in this new age of open information and conversation among scientists and between scientists and the public; and, yes, masks. I thoroughly enjoyed our conversation. I hope you — especially journalists — find it useful.

The post COVID Journalism: Episodes 1-4 appeared first on BuzzMachine.

COVID Journalism: Episodes 1-3

I have been interviewing experts in COVID-19 to give journalists advice about how to cover the crisis.

In our Social Journalism program at the Newmark Journalism School, we believe community journalism must start with listening to the community. Well, science journalism must start with listening to the scientists. This is why I have been maintaining a COVID Twitter list of more than 500 credentialed, relevant experts.

So I have spoken so far with an epidemiologist, an infectious disease expert, and a virologist. I will continue with other experts in more disciplines. Here are the first three interviews:

Episode 1: Yale epidemiologist Dr. Gregg Gonsalves

I start with epidemiologist Dr. Gregg Gonsalves of Yale, who has been a trenchant critic of coverage, especially of armchair epidemiology from the op-ed pages of The New York Times. He is also a strong voice in my COVID Twitter list of more than 500 experts.

Dr. Gonsalves dissects what was wrong with a contrarian Times op-ed arguing that the cure might be worse than the disease — something we’ve heard since from Trump and company. The Times’ mistake was in giving space to a contrarian rather than an expert, succumbing to our professional weakness for false balance and controversy, even if manufactured. We discuss the challenges of journalists covering modeling and the politicization of research. Importantly, he gives journalists advice about what they should be covering: not only the medical scandal of the century in the Trump administration’s failures in this epidemic, but also what will come next. He says much of the work to come will fall on local journalists (at a time when local journalism is suffering and years past the departure of most local science reporters).

Episode 2: Infectious diseases expert and ebola veteran Dr. Krutika Kuppalli

Dr. Krutika Kuppalli is an expert in infectious diseases with experience in HIV and Ebola. She is vice chair of the Global Health Committee at the Infectious Diseases Society of America and a Biosecurity Fellow at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. She supervised treatment at an Ebola unit in Sierra Leone in the 2014 outbreak and has also worked in Ethiopia, India, Uganda, and Haiti.

I asked her advice on how to cover the transmission of the virus; what to look for and when to look for it in news about the development of therapeutics and vaccines; and — importantly — how bring attention to what I believe is the great uncovered story of this crisis: inequality and its impact on poor and vulnerable communities in the U.S. and worldwide. Dr. Kuppalli emphasized both her concern for the impact the pandemic will have on poor nations — and what we can learn from them, considering that nations like Sierra Leone faced Ebola without the money we in America can throw at problems. We also spoke about the psychological toll treating the disease has to be having on our health care workers. Finally, she urges reporters, editors, and bookers to check the credentials of the sources you call to make sure they are experts with experience, not people from other fields with opinions. Now more than ever, expertise matters. We must amplify it.

Episode 3: Columbia virologist Dr. Angela Rasmussen

Now I interview a virologist, Dr. Angela Rasmussen of Columbia’s School of Public Health, to get her help for journalists covering the COVID-19 crisis. She and I talk about what media are doing right and wrong; about the need for journalists — reporters, editors, bookers — to find the appropriate, relevant, credentialed experts and to take advantage of the tremendous diversity among them; about how she works in this new age of open information and conversation among scientists and between scientists and the public; and, yes, masks. I thoroughly enjoyed our conversation. I hope you — especially journalists — find it useful.

The post COVID Journalism: Episodes 1-3 appeared first on BuzzMachine.

March 31, 2020

9/11-19

I didn’t realize how affected I have been by the trauma of COVID-19 until today, when the death toll in America passed that of 9/11, when the cumulative stress of seeing medical workers suffer and scientists wonder and politicians bungle piled too high, when I found myself snapping for no good reason, when the pain of uncertainty returned.

On 9/11, I was at the World Trade Center, feeling the heat of the jets’ impact, seeing lives lost, overcome by the debris of the towers’ fall, barely surviving — because I didn’t step two feet this way or that — and witnessing my mortality in the moment, the result of my bad decision to stay and report … for what? for a story.

Now that moment of mortality is every day, fearing the wrong moment in a grocery story or touching a surface or rubbing a nose will do any of us in, jeopardizing ourselves, our families, our communities. It is 9/11 in slow-motion, repeated every day for everyone: a morning that will last a year or two; evil groundhog day.

One of my last trips into Manhattan before the shutdown was to Bellevue Hospital, to the World Trade Center Health Program, where I finally went after many years of denial to have them prod my body and memory. I thought it would be therapeutic. It was more bureaucratic, to certify me for treatment that doesn’t really exist for my two cancers (both lite: prostate and thyroid, each on the List), for my heart condition (atrial fibrillation, not on the List), for respiratory issues (sleep apnea; I’ll get a machine), and — here was my surprise — for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Me? I’m fine. Just fine. I have been for 19 years, not just coping but always cognizant of my privilege, having survived the day and prospered since, lucky to have my family and home and work.

And then, 19 years later, comes COVID-19 (as if numbers were self-aware of their irony) to remind me again of my fragility, my mortality.

I am still fortunate and know that well. I live out in the country with much social distance around me. I have a wonderful family and thanks to my wife am safe at home. I have a rewarding job working with dedicated deans and teachers who want nothing more than to help our students not just weather this crisis but learn from it and become wiser and more resilient for it. Thanks to the internet, I can keep my job and income and my connection with the world. I am privileged still.

I look at the numbers on charts, deaths and death rates daily, and think we are not doing a good job of seeing the humanity in them. The so-called president acts as if losing 100,000 or 200,000 people is a job well-done and deserving of credit. His flags are not at half-staff; never. The news is just beginning to fill with the names of the lost, the stories of their lives buried under slopes on charts. So many of the first we lose are selfless medical workers, gone for no reason, gone because of our feckless government’s denials. God knows how the doctors and nurses do this, facing the mortality of so many, including themselves, every moment. God bless them.

I am not them. We do not have to be among them. We do not have to be if we pay attention and stay inside and don’t breathe the wrong air and touch the wrong thing and scratch our eyes at the wrong moment and hang on until science — blessed science — gives us a vaccine. I bury myself in science. That is where I find hope.

But we are vulnerable. We always are, always have been, always will be. It’s just that most of the time, we manage to ignore that fact.

Especially us New Yorkers. Our city is so strong: The center of the fucking universe, as I delight in telling students and visitors, a fortress of spirit and will, intelligence and effort. But here it is again, under attack, brought down and brought silent this time by a mere virus for which we — the nation — were criminally unprepared.

And so my anger does me in. I cannot bear watching him on television every fucking night, that tower of ego and unself-aware fragility exploiting the vulnerability and suffering and his citizens and spewing falsity and hate and ignorance to his cult. That is too much to bear. I am ashamed of my own life’s field, media, for giving him this platform, for not calling his lies until they are spread like a virus across the land, for failing to diagnose the disease that he is. This depresses me.

But writing this is its own form of self-indulgence, I must confess. I haven’t shared emotions like this since some long-gone anniversary of 9/11. For I was healing or healed, I thought. But now I see my weakness again. The emotions are bare.

I told the psychiatrist at Bellevue (a phrase I use with no irony) that I saw few lasting effects of 9/11 on my psyche. I became phobic about bridges and there are many I will not cross. I find my emotions can well up at the most idiotic moments, when a manipulative twist in a TV show or even a goddamned commercial can peel me back and reveal my gooey center. But all that’s not so hard to control. I just find the nearest tunnel or a shorter bridge and shake my head to wave off the storytellers’ manipulation of my heart.

Yet today that is harder. The emotions are rising again. I wouldn’t name them fear. I’d name them apprehension and worry and anger and stress and empathy for the numberless and nameless who go before us, too soon.

So there. Nineteen years ago, when I started blogging after that day, I found it helpful to share so I could connect with others and learn I was far from alone. That act itself — linking with people here, online — changed my perspective of my career, of journalism, of media, of society. It taught me that properly considered my life and profession should not have been about writing stories but about listening and conversing; that is what I believe now. That gave me a new career as a teacher.

Now I don’t tell my story so much as I confess my weakness in case someone reading this feels the same: vulnerable but fortunate, worried but wishing, just uncertain yet not alone.

The post 9/11-19 appeared first on BuzzMachine.

March 24, 2020

Time for Experts

In this novel crisis, we in media and online need to shift much of our attention away from trying to eradicate disinformation (and how’s that going?) to spend more of our time and resources once again finding and amplifying good information — authoritative information from experts.

That is why I am maintaining and immersing myself in my COVID Twitter list of 500 epidemiologists, virologists, physicians, researchers, NGOs, and selected specialist journalists. I have been taking in their conversations with each other and the public, learning every hour, privileged to be able to ask questions, witnessing science in action; it’s that and only that that gives me hope. Through those experts I get a better view of our new reality versus any bro’s contrarian thumbsucking in blog posts or New York Times columns or in mindless TV location shots in front of poke bars that — guess what? — have no business. More on all that in a minute.

Of course, I’m not suggesting an end to fact-checking and fighting disinformation. First Draft, Storyful, fact-checkers worldwide, and news organizations aplenty have that well in hand, or as well as anyone can these days. But the flavor of disinformation has changed; the target has shifted; the enemy is different. As First Draft’s founder and my leader in all such things, Dr. Claire Wardle, said in a video conference with journalists the other day, much disinformation these days comes not from malicious actors but from the well-meaning ignorant. Ignorance is our foe.

That is why we need the experts. That is why we need to put our effort behind finding them, listening to them, learning from them, and amplifying what they have to say. That is media’s job № 1.

Cable TV news is doing a decent job, I think, of getting experts on air to answer questions — authorities such as Dr. Caitlin Rivers, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Dr. Peter Hotez, professor at Baylor; Dr. Ashish Jha of Harvard; Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel of Penn; Dr. Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness; Andy Slavitt, former Obama ACA head. My primary complaint is that, TV being TV, they fill too much time with meaningless, repetitive location shots, coming back to an empty deli or Times Square a dozen times in a day or standing in front of the soon-to-be mass hospital at Javits Center where there’s no reporting to be done. Stop.

I want to see that time filled instead with more voices of science. I want to see TV do what it does best: make stars, stars of experts, scientists, doctors — the people we should trust and listen to, not pontificators or certain politicians at podiums. I can recommend many more scientists from my list. Here are some examples:

Devi Sridhar, chair of global health at the University of Edinburgh, has been a brilliant and outspoken critic of UK policy who can explain anything in the crisis with crystal clarity. Watch her from two years ago predicting precisely predict what we are now enduring:

"Our biggest health challenges are interconnected."

— Hay Festival (@hayfestival) March 16, 2020

– @devisridhar gave a prescient talk on global health alongside @ChelseaClinton at Hay Festival 2018. Worth another watch over on #HayPlayer now https://t.co/HO4e9Qorut pic.twitter.com/QqTmhYxsRo

Here is Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, a lead researcher on the NIH effort to create a vaccine and an excellent explainer on Twitter.

Also from the UK (which I recommend because we need international perspectives) here is scientist Mike Galsworthy explaining with concise clarity and a simple notebook why Boris Johnson’s herd immunity strategy was dead wrong.

It looks like UK govt messed up Covid-19 modeling… and are now backtracking hard. https://t.co/Jw0pWuhbKg

— Mike Galsworthy (@mikegalsworthy) March 16, 2020

And more experts with amazing credentials and a talent for explanation:

Yale’s Dr. Greg Gonsalves is fantastic on Twitter — blunt and informative (you’ll hear more from him in a moment);Dr. Marc Lipsitch, a highly respected epidemiologist at Harvard;Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University;Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia;Dr. Florian Krammer of Mt. Sinai, who has delighted scientists with his work on COVID-19 serology (which can lead to a test to see who is over the disease);Dr. Ellie Murray, an epidemiologist who is super at making graphic explainers of virology;Dr. Jeremy Faust of Harvard and now publisher of an authoritative COVID newsletter, Brief19;Richard Horton, editor in chief of The Lancet;Dr. Christian Drosten, a German virologist who is having considerable influence on policy there (here’s an excellent interview with him);Dr. Saskia Popescu, who has a PhD in biodefense;Dr. Muge Cevik, a virology clinician and researcher at the University of St. Andrews;Adam Kucharski, author of The Rules of Contagion;Juliette Kayyem, a Harvard prof now writing in The Atlantic;Dr. Celine Gounder, an NYU prof and cohost of the Epidemic Podcast on with Biden advisor Ronald Klain;Dr. Howard Forman, radiologist and former Senate staff;Dr. Emma Hodcroft, doing amazing work in tracking the various strains of the disease and how they have spread, in collaboration with scientists around the world ;Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding, an epidemiologist at Harvard;Dr. Krutika Kuppalli, who specializes in pandemic preparedness;Kai Kupferschmidt, a science journalist who has been good on the topic;Lawrence Gostin, professor of global health law at Georgetown;Lisa Jarvis (no relation), a reporter at Chemical and Engineering News;Dr. Rob Davidson is the frontline ER physician who challenged Vice-President Pence and who gives us messages, exhausted, after his shifts.

They are all sharing directly with us on Twitter; what a privilege to be able to read them. That is but a small sample of the 500 experts I follow. You could follow each of them or better yet subscribe to my list (I get nothing out of it but the knowledge that you’ll help spread good information). Twitter, to its credit, decided they wanted to expedite verification (that is, the anointing of checkmarks) of these experts and so they came to me for help and I’ve been trying to guide some of them through the process, still ongoing.

One caution: What passes in tweet-length conversation in the midst of a constantly changing situation is science in progress. That is to say, there are no answers and conclusions, but there is information and data, and there are important questions. And that would be OK for most people. But Trump. I retweeted a report of very incomplete information about one doctor’s experience giving a few patients a malaria drug and antibiotic — worth looking at, the doctors in my feed said; no more. Then Trump trumpeted this as practically a cure, causing doctors to scream and a run on the medicine. I was properly castigated by someone on Twitter for tweeting such a small study and he was right to the extent that I should have added the context that it was small and nowhere near conclusive. You might wish for the days of gatekeepers — reporters — to add that context, but we’re leaving that era. I welcome hearing so much information directly from so many experts and practitioners. In this age of more open information, the public will have to learn to deal with incomplete data. You might call what’s needed media literacy, except media often do an idiotic job of reporting the progress of science (“Wine will kill us!” “Wine will save us!”). I call the solution simply education.

Now let us compare and contrast how certain media have dealt with — that is, spread or ignored — expertise. Some media have been wonderful. The Atlantic immediately put its excellent COVID coverage — for example this well-documented policy proposal from two renowned doctors and an ongoing project tracking how many Americans have the disease — outside its paywall. Some followed the example, making COVID coverage free; some haven’t. For God’s sake, if there were ever a moment when journalists should see reporting as a public good, if there were ever a moment when we should do everything we can to eradicate ignorance so we help eradicate this threat, this is it! Before you start poor-mouthing about tough times — which we all now share — know that it was The Atlantic’s decision to go outside its paywall that motivated me to subscribe. Sometimes doing good is its own reward; sometimes, there’s a bonus.

I also want to single out Medium for praise. As a platform, it does not choose what is posted there. Among the God-knows-how-many posts that went up recently was an absolutely awful festival in willful ignorance and hubris from a so-called growth hacker who thought he could do better with epidemiological data than untold experts around the world. To quote:

I’m quite experienced at understanding virality, how things grow, and data. In my vocation, I’m most known for popularizing the “growth hacking movement” in Silicon Valley that specializes in driving rapid and viral adoption of technology products. Data is data. Our focus here isn’t treatments but numbers. You don’t need a special degree to understand what the data says and doesn’t say. Numbers are universal.

Scores of experts in my Twitter list went properly berserk over his conclusions, — a biology professor at the University of Washington, Dr. Carl Bergstrom, decrying every paragraph. It spread for a time via Fox News fools and others. (I could insert a rant here about Fox News and Rupert Murdoch killing people and democracy, but let’s just stipulate that for the time being.)

But then Medium took the piece down.

UPDATE: Medium released this statement about the takedown:

“We’re giving careful scrutiny to coronavirus-related content on Medium to help stem misinformation that could be detrimental to public safety. The post was removed based on its violation of our Rules, specifically the risk analysis framework we use for ‘Controversial, Suspect, and Extreme Content.’ We’ve clarified these rules to address more specific concerns around the evolving public health crisis. We’ve also taken steps to point readers to credible, fact-checked pieces on Medium and elsewhere on the web, and to remind readers that Medium is an open platform where anyone can write. We’re assessing the situation daily and making adjustments as necessary.”

Bravo for Medium. Yes, I wish Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, et al would do likewise. The differences are clear: Medium is a platform for content while social media provide platforms for conversation; social media carries exponentially more items to monitor. Facebook says, and I agree, that it would make a bad arbiter of truth. Fine. But I do want to see especially Facebook grow a spine and decide what does and does not fit in the community it has built. Denying informed science and endangering lives belongs in no community. Besides tamping down the bad, I also want to see Facebook, like Twitter, do everything possible to amplify science and sense.

Yes, there are idiots out there and idiots who believe idiots and who don’t want to believe science. But we will go mad trying to save them all from their ignorance; we are too busy to focus on them. I say we must concentrate now on those willing, wishing, and needing to learn, which I firmly believe is most of us. We do that by helping them pay attention to science and facts and helping them ignore the idiots.

You’d think that concentrating on the evidence produced by experts would be easy at a publication still controlled by editors, as opposed to a technology platform. But I cannot understand why The New York Times is publishing some of what it has published lately, fully in its control.

Take, for example, this op-ed by David Katz, which like the post Medium took down takes a contrarian position that this pandemic really isn’t as bad as it seems, implying we are overreacting. Once again, countless experts in my Twitter list went nuts over this. They were particularly amazed that The Times chose to give over its precious space and its invaluable distribution and imprimatur not to an epidemiologist or a virologist but to someone who is well-known for defending sugar and acting as a California walnut ambassador and creating a discredited nutrition rating system (all of which The Times could have found, as I did, in a simple Google search). Could The Times have found no one more knowledgeable about the disease? I could suggest 500 people. Here Yale’s Dr. Greg Gonsalves takes it apart:

So right. In choosing that author and that op-ed and passing on others who know so much more, The Times is — I’ll repeat Gonsalves’ words —exercising “denigration of expertise, when we need it most, prizing generalist knowledge when specifics matter.”

And it gets worse with — surprise, surprise — Bret Stephens, who took the same contrarian path, questioning the experts and their “models” — yes, he put “models” in scare quotes. He based his arguments in great measure on a piece by John P.A. Ioannidis — which I had already seen the expert doctors in my Twitter list excoriate. Here is a very polite takedown of Ioannidis’ theories by Harvard’s Dr. Marc Lipsitch, who concludes: “Waiting and hoping for a miracle as health systems are overrun by Covid-19 is not an option. For the short term there is no choice but to use the time we are buying with social distancing to mobilize a massive political, economic, and societal effort to find new ways to cope with this virus.”

And then there is Tom Friedman’s latest column, in which he echoes the challenges of the contrarians: “Is this cure — even for a short while — worse than the disease?’’ He all but gives the back of his hand to the epidemiologists who are informing policy, calling what they offer — with scare quotes — “group think.” Good Lord. Theirs is not the opinion of a goddamned coffee klatch. It’s science, based on data and experience — which is more than any columnist has. Friedman hides behind the classic excuse of the journalist: “I am not a medical expert. I’m just a reporter.” Translated: We’re supposed to ask dumb questions — just questions — on behalf of the dumb public. No! Our job is to go to the experts to help make the public smarter. Amazingly, Friedman goes on to favorably quote both Katz and Ioannidis from The New York Times. Talk about an echo chamber! Talk about “group think”!

Gonsalves tweeted again, about this Times hat trick, and I must quote it all:

Expertise. We will live or die by expertise: by science, by evidence, by experience, by knowledge, by data. Hot takes will kill us, whether they are Donald Trump’s (‘I have a good feeling about the drug’) or a tech bro’s (‘I know data’) or New York Times’ columnists’ with their scare quotes (‘are “group think” and “models” good? we’re just asking’).

In journalism, we are never experts. It is our job to find experts and give them voice for the public, adding questions and context where helpful. But thank goodness, I don’t need the journalists to stand in the way. I can go straight to 500 amazing, brave, brilliant, experienced, knowledgeable, dedicated, and caring experts thanks to the internet.

Thank you, doctors.

The post Time for Experts appeared first on BuzzMachine.

March 13, 2020

In this crisis, God bless the net

Imagine, just try to imagine what it would be like to weather this very real-world crisis without the internet. Then imagine all the ways it can help even more. And stop, please stop claiming the net is broken and makes the world worse. It doesn’t. In this moment, be grateful for it.

What we need most right now is expertise. Thanks to the net, it’s not at all hard to find. I spent a few hours putting together a COVID Twitter list of more than 200 experts: doctors, epidemiologists, academics, policymakers, and journalists. It is already invaluable to me, giving me and anyone who cares to follow it news, facts, data, education, context, answers. Between social and search, good information is easy to find — and disinformation easy to deflate and ignore.

Through that list and elsewhere on the net, I am heartened to see how generously and quickly experts are sharing information with each other: asking for data on presenting symptoms, or emergency room experience in Italy and China, or information on how long the virus stays active on various surfaces. The net will help them do their jobs more effectively and that will benefit us all.

On social media, I have watched citizens connect, gather, and mobilize to press authorities and companies to act responsibly (well, except the ones who are never responsible). CUNY students used hashtags and petitions to hold a virtual protest or march — or very nearly riot — to insist that our classes go online. It worked.

Online, we can thus see the shaping of public policy occur in public, with the public, in full view, and with complete accountability. On social media, we the people get to lobby for what matters most urgently to us in this crisis: availability of free testing, help for workers over companies, paid sick leave. I am confident that without the collective voice of the concerned public online, the powerful would have been much slower to act.

In the coming weeks — months?— of social distancing, we will feel isolated, anxious, bored, stir-crazy; we will need to reach out to the people we cannot touch. The net — yes, Facebook and Twitter — will enable us to socialize, to connect with friends and family, to find and offer help, to stay connected with each other, to stay sane. How invaluable is that! Imagine having only the telephone. Imagine a crisis without the relief of humor, without silly social memes.*

Of course, it is the net and all its tools that empower us to work at home, to keep the economy moving in spite of shutting the physical presences of most every business, to keep many — if too few — people employed. Imagine the value of the economy during a pandemic without the net.

It is the net that also allows us to buy from Amazon — even if we go overboard with everything good and use this power to hoard toilet paper.

The internet is doing just what it should do: connect people with information, people with people, information with information. It enables us to speak, listen, assemble, and act from anywhere. It is just what we need today.

I have been upset lately with some people claiming that the net is broken. This often comes from technologists who helped build the net we have, who go through some sort of Damascene conversion, who then claim that the net is breaking society, and who ultimately argue that they are the ones to fix it — fix what they helped break in the first place. What boundless, self-serving, privileged hubris.

I was going to write a screed about the damage these dystopians can do to the freedoms the net brings us, and I probably still will. But then news overtook my attention and I decided instead that this is the moment to remind us of the gift the net is, how much we depend upon it, and how grateful we should be for it. So much attention in media and government lately goes to what is wrong on and about the net, blaming it for our human shortcomings. But I repeat: It is wonderfully easy to find good information from experts in this moment and it is easy to ignore the idiots. What’s been wrong is that we have been paying too much attention to those idiots. Hell, we elected one president. No, I don’t blame the net for that. I blame old, mass media: Fox News and talk radio. You want to hold someone responsible for the mess we are in? Start there.

So now let us turn our attention to how to improve — not fix — the net and, more to the point, how we use it. We need more mechanisms to find and listen to expertise and authority. We need better means to listen to communities in need and communities too long ignored by Gutenberg’s old, mass media. We need to develop models for supporting sharing of reliable information and continually educating people. There is much work to do.

Is the net perfect? Of course, it is not. I’ll remind you that when movable type was introduced, it was used to print lies and hate, to bring the corruption of indulgences to scale, to seed nationalism, and to fuel peasant uprisings and massacres, the Thirty Years War, and perhaps every Western war since. Did print break society? No, it let society be what society would be. Did we ever perfect print? Of course not. Could we imagine life without it? No.

Martin Luther called printing “the ultimate gift of God and the greatest one.” Well, I’d say God outdid herself with her next act.

* Favorite meme so far:

The post In this crisis, God bless the net appeared first on BuzzMachine.

February 3, 2020

Stop. Stop the presses.

At the end of an exceptional first week for our new program in News Innovation and Leadership at the Newmark J-school, the students — five managing editors, a VP, a CEO, and many directors among them — said they learned much from teachers and speakers, yes, but the greatest value likely came from each other, from the candid lessons they all shared.