Jeff Jarvis's Blog, page 6

October 10, 2022

Habermas online

*

*In 2006, Jürgen Habermas, the preeminent theorist of the public sphere, spoke of the internet for the first time, only in a footnote, all but dismissing the net as “millions of fragmented chat rooms.” Many have waited for more. Now, in a paper recently published and translated, Habermas finally reflects on the internet and its impact on public discourse.

Habermas now calls the internet “a caesura in the development of media in human history comparable to the introduction of printing,” an “equally momentous innovation” to the invention of movable type, and a “third revolution in communications technologies” whose result is “the global dissolution of boundaries” as “the communication flows of our garrulous species have spread, accelerated and become networked with unprecedented speed across the entire globe and, retrospectively, across all epochs of world history.”

As someone who has a book positing just that coming out in June — The Gutenberg Parenthesis: The Age of Print and Its Lessons for the Age of the Internet (preorder now) — I am gratified, indeed relieved not to be alone. In my book and now here, I will dispute Habermas. Agree or disagree with his provocations, though, they have a way of helping to clarify one’s own thinking. (Sadly, Habermas’ paper is behind high academic paywalls festooned with barbed wire — $351.83 to get inside the special issue — so linking to it does little good, and I am not up to the task of summarizing all he has to say. Instead, I will offer a few reactions and debates of my own about publics, media, and speech.)

Habermas has long sought the substantiation of the public sphere. Many say that ultimately eluded him in his seminal work, in which he asserted that a bourgeois public sphere mediating between populace and state emerged in critical, rational and inclusive discourse in the coffeehouses and salons of England and Europe. Problem is, that debate was far from inclusive, as it was open only to the privileged patrons of the establishments, excluding women and people of lower classes. Neither was the discussion necessarily rational, as coffeehouse historians Aytoun Ellis, Brian Cowan, Markman Ellis, and Lawrence Klein amply document. Nancy Fraser’s feminist critique of Habermas’ theory is convincing: “We can no longer assume that the bourgeois conception of the public sphere was simply an unrealized utopian ideal; it was also a masculinist ideological notion that functioned to legitimate an emergent form of class rule…. In short, is the idea of the public sphere an instrument of domination or a utopian ideal?”

Today Habermas seeks his public sphere on the internet, suggesting that “at first, the new media seemed to herald at last the fulfillment of the egalitarian-universalist claim of the bourgeois public sphere to include all citizens equally.” He has a habit of proposing the emergence of a public sphere and then simultaneously mourning its passing. As for the seventeenth- and eighteenth- public sphere, he lamented its denigration via mass media and the welfare state. As for the networked public sphere of present day, he complains of echo chambers, the dissolution of boundaries, the blurring of private and public, and social media fragmenting this new institution as soon as it appears.

But there never has been and never will be a singular public sphere; that is the fundamental fallacy of the theory. Instead, there are multiple, overlapping imagined communities, publics, institutions, and markets that vie for power and attention through debate, privilege, and protest. Michael Warner proposed counterpublics: the idea that some publics “are defined by their tension with a larger public.” Fraser wrote that alongside Habermas’ bourgeois public “there arose a host of competing counterpublics, including nationalist publics, popular peasant publics, elite women’s publics, and working-class publics. Thus there were competing publics from the start, not just in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as Habermas implies.”

Habermas repeats the mistake much of mainline media make when he interprets January 6 as “the emotive response of voters who for decades have lacked a sense that their ignored interests are taken seriously by the political system in concrete, discernible ways.” He blames political elites, saying they had “for decades disappointed the legitimate, constitutionally guaranteed expectations of a significant portion of citizens.” No. It’s not that the insurrectionists — white men — had been neglected by the power structure; they were that power structure. It’s that white men see their power slipping away at the hands of so many counterpublics — read: people of color and women — who had been neglected and now may finally be heard via the internet. As a European, Habermas fails to account for race in the public Reformation (#blacklivesmatter) and Counter-reformation (MAGA) occurring now in America.

In Habermas’ worldview, there is today a public sphere online that decomposes into “competing public spheres” and “shielded echo chambers.” (Note well that the echo chamber is a trope with little empirical data and research to support it. See Axel Bruns’ Are Filter Bubbles Real? and its answer: No.) Fraser suggests the opposite, a public not decomposing but growing out of “a multiplicity of publics” as “an advance toward democracy” to “promote the ideal of participatory parity.” She warns: “Where societal inequality persists, deliberative processes in public spheres will tend to operate to the advantage of dominant groups and to the disadvantage of subordinates. Now I want to add that these effects will be exacerbated where there is only a single, comprehensive public sphere.” That is, the vision of a single public sphere brings with it the presumption of norms and standards set on high, from those with the power to impose their vision upon all. (See, for example, journalistic objectivity — and Wesley Lowery’s critical op-ed exposing that institution’s roots in white power.)

Fraser says that with a single public sphere, “members of subordinated groups would have no arenas for deliberation among themselves about their needs, objectives, and strategies.” Fraser labels such groups “subaltern counterpublics.” In André Brock Jr.’s book, Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures, which I quote and teach often, he calls Black Twitter a “satellite counterpublic sphere.” All this is to say that rather than imprinting Habermas’ worldview on the internet, it would be more productive to understand the net for what it is becoming and adjust one’s worldview accordingly, not to pursue a single, decaying public but instead to study an interlocking ecology of many publics.

One need also adjust one’s view of media. In his foundational 1962 book, Habermas lamented the damage wrought by mass media on his first public sphere of the coffeehouse. In his current paper, he laments the supersession of mass media by social media and its effect on his new public sphere of the internet. He still imbues in mass media the power — the responsibility, in fact — to shape public opinion. “The function of the professional media is to rationally process the input that is fed into the public sphere via the information channels of the political parties, of the interest groups and PR agencies, and of the societal subsystems, among others, as well as by the organisations and intellectuals of civil society.” He goes farther: “[T]he public communication steered by mass media is the only domain in which the noise of voices can condense into relevant and effective public opinions.” He longs for “a professionalized staff that plays the gatekeeper role.” Habermas says that mass-media journalism “directs the throughput and … forms the infrastructure of the public sphere.”** Extending his electronic imagery, he argues that institutions provide the input, the public receives the output, media throughput. But I say he needs to reverse his wires.

Actually, Habermas made me understand that I have reversed my wires. I now see that the role of media is not to shape public opinion but instead to listen to public opinions now that the internet makes that possible. The goal is not to direct the views of the powerful in institutions toward the public but instead to direct the needs, desires, and goals of citizens to those in power. What has to be shaped is not public opinion about public policy but instead policy to the needs of the public. Whether media have a role in that process — that reversed throughput— is yet to be seen.

Today, media use polls as a proxy for a discerning and disseminating public opinion. Polls are fatally flawed, carrying the biases of the pollster, reducing citizens’ nuanced opinions to preconceived binaries, and warping identities into to prepackaged demographics. As James Carey — whom I also often quote — teaches us, polling preempts the public conversation it is intended to measure. In fairness, it’s all media had: one-size-fits-all publications carrying all-fit-in-one-size polls to represent vox pop.

But the internet changes that, as Habermas acknowledges, “by empowering all potential users in principle to become independent and equally entitled authors.” Now, instead of measuring people in binary buckets, we may listen to them as individuals. Habermas and countless others might consider that the ruin of democracy. He regrets speech occurring “without responsibility” or regulation: “Today, this great emancipatory promise is being drowned out by the desolate cacophony in fragmented, self-enclosed echo chambers.” No, in that cacophony, which media cannot manage, is the opportunity of democracy to hear citizens on and in their own terms, in their own communities of many definitions, as their own publics. That will require a new institution, a media of reversed pipes, to build means to listen well. That does not yet exist.

What shape would that new institution take? On the one hand, I am overjoyed that Habermas acknowledges — as I often argue — that “the new media are not ‘media’ in the established sense.” Yet he then turns around to reveal his expectation that people talking online should meet the standards of media and journalism. He is nostalgic and he is worried. He heralds “post-truth democracy” and regrets the passing of print and even of daily newspapers taking on “the ‘colourful’ format of entertaining Sunday newspapers.” German newspapers are particularly gray. “[T]he dramatic loss of relevance of the print media compared to the dominant auto-visual media seems to point to a declining level of aspiration of the offerings, and hence also for the fact that the citizens’ receptiveness and intellectual processing of politically relevant news and problems are on the decline.” When radio emerged as print’s first competitor, newspapers denigrated the receptivity of ear versus eye and called for the new technology to be regulated, just as Habermas demands that “platforms cannot evade all duties of journalistic care” and “should be liable for news that they neither produce nor edit.” Let us hope the Supreme Court does not read this in its deliberations over Section 230.

At least Habermas acknowledges that this process, whatever its shape and purpose, will take time. “Just as printing made everyone a potential reader, today digitisation is making everyone into a potential author. But how long did it take until everyone was able to read?” He expects speakers online to aspire to the roles of journalist and author, to “satisfy the entry requirements to the editorial public sphere…. The author role has to be learned; and as long as this has not been realized in the political exchange in social media, the quality of uninhibited discourse shielded from dissonant opinions and criticism will continue to suffer.” No. I say we must learn to accept online speech for what it is — conversation — and value it for what it reveals of people’s opinions and for the opportunity to engage in dialog. Habermas is rather befuddled by public spaces that carry the kind of content that used to be reserved for handwritten letters: “they can be understood neither as public nor private, but rather as a sphere of communication that had previously been reserved for private correspondence but is not inflated into a new and intimate kind of public sphere.” Is he not describing Montaigne’s place in the development of print culture?

In the end, I wish for what Habermas desires: democracy underpinned by inclusion and by public discourse as “the competition for better reasons,” as he said a half-century ago. Or as he says now: “I do not see deliberative politics as a far-fetched ideal against which sordid reality must be measured, but as an existential precondition in pluralistic societies of any democracy worthy of the name.” He is an idealist. “The point of deliberative politics is, after all, that it enables us to improve our beliefs through political disputes and get closer to correct solutions to problems. In the cacophony of conflicting opinions unleashed in the public sphere only one thing is presupposed — the consensus on the shared constitutional principles that legitimises all other disputes.” Unless, of course, one is a MAGA Republican, an AfD populist, or the leader of Hungary or Turkey, for whom the goal is not Habermas’ wished-for rational consensus but instead the visceral attractions of hate, fear, power, and insurrection.

Media have failed to get us to Habermas’ promised land. So far, so have so-called social media. Perhaps we have expected too much of either. Perhaps we have expected too much from the mere serving of information. Perhaps media must take on a new role, as educator, for education is the only cure for the ignorance reigning in the land. Or instead, should education take on the role of informing the public after school? (See this recent thread about academics leaving the academy to pursue public scholarship.) Or will we need to create new institutions to serve public enlightenment and discourse, just as we had to await the creation of the institutions of editing and publishing and journalism after the invention of print?

The shape of public discourse is changing radically and trying to pour new wine in an old Weltanschauung will not work. I can hardly blame Habermas for trying to do that, for he has spent a brilliant life crafting his theories of democracy and discourse. I find his effort to understand this new world useful not because I agree but because it focuses my perspective through a different lens. The worldwide network does not corrupt some ideal that was never achieved but instead allows us to imagine new ideals and new paths toward it.

* Not Jürgen Habermas but Dreamstudio’s AI image of him online

** Habermas is oddly italics-happy in his essay; his itals are his. In my book Public Parts, I got in trouble with Habermas adherents for likening his prose to wurst. I cannot pass up the temptation to quote one footnoted and much-italicized sentence of his here: “The lack of ‘saturation’ concerns the temporal dimension of the exhaustion — still to be achieved in the political community and still to be specified as regards its content — of the indeterminately context-transcending substance of established fundamental rights, as well as the spatial dimension of a still outstanding world-wide implementation of human rights.”

The post Habermas online appeared first on BuzzMachine.

October 9, 2022

20 Post-it provocations on media

Recently, I was asked to open an unconference with students and grads from our News Innovation and Leadership program at Newmark. I was also preparing for a Newsgeist unconference (which I unfortunately had to miss). Thus my mind has been its own unconference; I sneeze Post-its. So, for our event, I decided to present 20 provocations for discussion about news and media as virtual Post-its (that is to say, tweets):

I’m thinking about the half-life of media forms. Magazines are going out of print. Studying the form, I’ve come to see how evanescent any publication can be and perhaps so is the genre. Television is in shambles as the institutions of prime-time, networks, linear television, broadcast, and even cable fade. Recently, The Times had a story about the unsustainable resource and risk it takes to make a best-seller. And the death of the print newspaper has been oft foretold but might finally be upon us, for it is fast becoming unsustainable. Nothing is forever. So what might follow?Journalism is unprepared to cover institutional insurrection. News organizations still seek balance, fairness, sanity, tradition, and the establishment and enforcement of norms, while much of the country seeks to tear down the institutions of society — journalism, science, education, free and fair elections, democracy itself. As Jay Rosen points out, we have no strategy for how to cover this coup.Should journalists be educators? Educators deal in outcomes, telling students what they will learn, teaching them that, and asking whether they learned it. What if journalism aimed for outcomes — such as reporting why people should get vaccinations or vote or believe election outcomes — and judged its value and success accordingly? Then do we become advocates? Activists? Propagandists? At a gathering of internet researchers we convened a few weeks ago, one of the academics asked whether all propaganda is bad. If the bad guys use it, should the good?Internet leadership. I’m turning my attention from news leadership to internet leadership. For I think we in journalism need to broaden the canvas upon which we work past stories, content, and publications to the connected society and its data. What should we then we teaching in journalism schools? What of the humanities and of ethics and historical context should technologists and policymakers be taught?The story as a form is an expression of power. It empowers the storyteller. It extracts and exploits others’ stories. It can tempt journalists into fabulism — witness the scandals over time at Der Spiegel, the NY Times, and Washington Post. It carries with it the expectation of neat arcs and endings. The story is an excellent tool, no doubt. But do we concentrate on it too much? Do we sufficiently warn students of its temptations and perils? Do we imaginatively teach many possible alternatives in journalism?Death to the mass! In two books I’ve just completed (plug: The Gutenberg Parenthesis, out in June, and another on the magazine as object, both from Bloomsbury), I write about the arc of the mass: its birth with the mechanization and industrialization of print, its fall at the hands of the net. What the net kills is the mass media business model, with it mass media, and with it the idea of the mass, an insult to the public, a way not to know them as individuals and communities. Said John Carey: “The ‘mass’ is, of course, a fiction. Its function, as a linguistic device, is to eliminate the human status of the majority of people.” How do we recenter journalism around individuals and their identities in communities?Our definition of “local” is too narrow. Communities are not just geographic. I am closer to the people on my Twitter List of Book History Wonks and all the media wonks here online than I am to my frequently Trumpian neighbors. How do we expand our definition of local to communities writ large, to people’s own definitions of themselves and their affinities, circumstances, needs, and interests? Yes, save local journalism — but redefine “local.”We have much to learn about communities making spaces for themselves from Black Twitter. I recommend Charlton Mcilwain’s Black Software and André Brock Jr.’s Distributed Blackness and I await Meredith D. Clark, PhD’s upcoming book. They chronicle efforts by communities to establish their own spaces, not under mass or white gaze. Communities do not need us. We in journalism need them.Jack Dorsey regrets making Twitter a company. He wishes it were a protocol so one could speak anywhere and anyone could build enterprises atop that speech layer, adding value — curating, verifying, editing, supporting. Especially now, I eagerly await what happens with his Bluesky. How might journalism fit into such an ecosystem?Censorship is futile. At the birth of every medium, incumbents fret about bad outcomes — fake news from print (witchcraft) or radio (War of the Worlds) or television (the “vast wasteland” where we “amuse ourselves to death”). How much better it is for us to turn our attention to finding, nurturing, supporting, and improving the good.Paywalls damage democracy. When disinformation is free, how can we restrict quality information to the privileged who choose to afford it? What is our moral obligation to democracy, to society as a whole?Fuck hot takes. The answer to abundance in media is not to pile on more abundance.Journalism is terribly, fatally inefficient. Every outlet copying every other outlet’s stories to make their own content on their own pages to get their own clicks and ads. Enough. We must concentrate on unique value.We desperately need more self-criticism in journalism. Especially after the departures of David Carr, Margaret Sullivan, and Brian Stelter. Media are actors in the story of democracy but they go uncovered.We desperately need more research on public discourse and media today. We must consider the entire media ecosystem, not just Facebook and not just The Times and not relying on such baseless tropes as the filter bubble. Doubt me? See Axel Bruns’ book, Are Filter Bubbles Real? His answer: No. We need to work with researchers to examine what we do, what works, and what does not.We need to reinvent advertising. The attention economy — invented by media and imported into the internet, is obsolete and damaging. Advertising must shift to value, permission, relevance, and utility. We will still need advertisers. Advertisers won’t reinvent themselves. So we have to.Media are engaged in a moral panic about the internet. See Nirit Weiss-Blatt’s book, The Techlash , in which she marks the pivot from utopian to dystopian coverage with the election of Donald Trump: Media wanted someone else to blame. News industry organizations have become lobbyists, cashing in journalism’s political capital for the sake of protectionism and baksheesh. At a time when freedom of expression is imperiled, we must do better and fight to protect the speech of all.Facebook is not forever. Even Google is not forever. And Twitter? Who knows what the next day brings? What new functions might we build?We have time. It is 1480 in Gutenberg years. I do not advocate longtermism. Our obligation to tomorrow begins today. In print, great innovation — the essay, the novel, the newspaper — did not come until 150 years after movable type. How long must we wait for such bold innovation online? Will you be such innovators?When will the first editor in chief or publisher of a major news operation come from the ranks of the people now known as “audience” or “product?” These are the new disciplines — new to news — that base their work and value on the relationship they have with, to borrow Rosen’s term, the people formerly known as the audience. I hope someone hearing this now will be that person.The post 20 Post-it provocations on media appeared first on BuzzMachine.

September 15, 2022

Publishers’ political blackmail

Senator Amy Klobuchar’s oxymoronically titled Journalism Competition and Preservation Act — it might better be named the Journalism Lobby Blackmail Bill — was just dealt a kick to the kidneys by a confused Ted Cruz amendment. It is delayed but not dead. It is still wrong-headed and dangerous and here I’ll examine how.

As ever, Mike Masnick does stellar work picking apart the bill’s idiocy and impact in detail. In summary, the JCPA would require big internet companies — Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon, though perhaps not the incredibly shrinking Facebook — to negotiate with midsize newspaper publishers. Freed from antitrust, the publishers may band together and demand payment for linking to their news. Yes, linking to their news. The value platforms bring in terms of promotion, distribution, and audience is not a factor in these negotiations. If agreement cannot be reached, talks go to a co-called arbitration process and the platforms can be forced to carry and pay for publishers’ content.

Stop right there. That government would force anyone to carry anyone else’s speech is a clear violation of the First Amendment. Compelled speech is not free speech. Keep in mind that the extremist right in Congress is dying to concoct ways to force platforms to carry their noxious speech; Klobuchar et al are paving a way for them. That government would force anyone to pay to link to others is a fundamental violation of the principles of the internet. Links are free. Links are speech. That government would insert itself in any way into journalism and speech is simply unconstitutional.

Let us now consider the wider context of this legislation and where it goes wrong.

Newspaper publishers do not deserve paymentGod did not grant newspaper publishers the revenue they had. They chose not adapt to the internet; I spent decades watching them at close range. Competitors offered better, more efficient and effective vehicles for advertisers, who fled overpriced, inefficient, monopolistic newspapers at first opportunity. Readers, whose trust in news has been falling since the ’70s, also fled. Welcome to capitalism, boys.

Today, most newspaper chains in America are controlled by hedge funds. I briefly served on digital advisory boards for one American and one Canadian company controlled by the hedgies and witnessed what they did: selling every possible asset, cutting costs to the marrow, and stopping all investment in innovation. The JCPA offers no real means of accountability to assure that platform money would go to journalism serving communities’ needs, not straight into the pockets of the hedgies. (The JCPA shares that problem with Rupert Murdoch’s similar blackmail bill in Australia.)

Journalists should not be lobbyistsI am appalled that legacy journalistic trade organizations — led by the News Media Alliance (née Newspaper Association of America, recently merged with the former Magazine Publishers Association)— have turned into lobbyists, cashing in news’ political capital and engaging in conflict of interest in the name of protectionism. Newspapers exist to stand independent of power in government, not beggars at its trough. Journalists themselves should rise up to protest what their publishers have ganged together to do: to sell their souls.

Newspapers have a long history of antitrustThis shameful behavior of publishers is not new. When radio emerged as print’s first competitor, papers did everything possible to prevent it from competing in news. Here are a few paragraphs recounting that episode from my upcoming book with Bloomsbury, The Gutenberg Parenthesis.*

In Media at War, Gwynth Jackaway chronicled American newspapers’ opposition to broadcast in a tale of defensiveness and protectionism that would be reprised with the arrivals of television and the internet. “Having been presented with a new technology, contemporary actors voice their concerns about how the new medium will change their lives, and in so doing they reveal their vulnerabilities,” she wrote…. Newspaper publishers tried to disadvantage their new competitors, strong-arming radio executives to agree to abandon news gathering, to buy and use only reports supplied by three wire services, to limit news bulletins to five minutes, and to sell no sponsorship of news. Their agreement also prohibited commentators from even discussing news less than twelve hours old (a so-called “hot news” doctrine the Associated Press would try to establish against internet sites as late as 2009). The pact fell away as wire services and station-owning newspapers bristled under its restrictions.

Print publishers tried other tactics. They threatened to stop printing radio schedules in their newspapers, but readers protested and radio won again. They lobbied to have radio regulated by the federal government and then unironically maintained that radio companies under government control would be unreliable covering government. The newspaper press tried to have radio reporters barred from the Congressional press galleries. They called radio a “monopolistic monster” and lobbied for a European model of government control of the airwaves. They blamed radio for siphoning off advertising revenue, though the Great Depression was more likely to blame for newspapers folding or consolidating in the era. They also lobbied for the government to limit or ban advertising on radio.

All their protectionism was cloaked in self-important, sacred rhetoric, with publishers accusing radio of manifold sins. Radio, they said, spread loose statements and false rumors: fake news. Radio “filched” and “lifted” news from newspapers. Radio seduced the public with the human voice to exploit emotions, to “catch and hold attention,” and to excite listeners. Will Irwin, a muckraking print journalist, wrote in his book Propaganda and the News: “The radio, through the magic inherent in the human voice, has means of appealing to the lower nerve centers and of creating emotions which the hearer mistakes for thoughts.” Radio was “a species of show business, with overtones of peddling and soap-boxing.” Editor and Publisher maintained that “the sense of hearing does not satisfy the same intellectual craving as does the sense of reading” and the editor of American Press claimed that “most folks are eye-minded. They get only impressions through their ears; they get facts through their eyes.”

“Using the doomsday approach that so often accompanies the invocation of ‘sacred’ values,” wrote Jackaway, “they warned that the values of democracy and the survival of our political system would be endangered” if radio took on the roles of informing the electorate and serving a marketplace of ideas….

“Never,” said Jackaway, “is there the admission that public opinion might be manipulated by the printed word as well as the spoken word, or any recognition that by attempting to control radio news the press was actually infringing upon the broadcasters’ freedom of expression.”

Sound familiar? This is the same industry that today wants to be excused from antitrust law and Klobuchar et al are doing its bidding.

Government must not license and limit journalismThe JCPA sets a definition for news organizations eligible for its benefits and thus defines and de facto licenses journalists. Beware: What government giveth government may take away.

To avoid accusation that the bill would transfer money from big tech to big media, the JCPA sets a limit of 1,500 employees. It also sets a floor of $100,000 revenue. Thus, many are excluded. In our entrepreneurial program at CUNY’s Newmark Journalism School, we train independent journalists to serve communities and markets; they are too small. Our Center for Community Media and its Black, Latino, and Asian Media Initiatives work with a wide array of news organizations serving communities; many of them are too small. LION, the wonderful association serving local news organizations, says 44 percent of its members are too small.

These newcomers and publishers of color are the real innovators in journalism, not the old, tired, failing, incumbent newspapers. They are left out of the JCPA. The JCPA is aimed at companies whose papers are, in the immortal words of Goldilocks, just right — that is, the ones controlled by the hedge funds who pay the lobbyists.

The help platforms should giveI am all for technology companies helping the cause of news. In full disclosure, my school receives funds from various of the technology companies to fight disinformation, to independently study the internet, to train journalists in the new skills of product, to train community news organizations in business innovation. For years, I’ve attended Newsgeist, an event started by the Knight Foundation and Google, and there I began what is now the tradition of running a session asking, “What should Google do for news?”

Forcing payments from technology companies as this bill and others elsewhere would do is no business model. It’s blackmail. What we need instead is help to develop new models. Google does that with subscriptions and YouTube players offering monetization. Facebook used to do that in various programs but has thrown up its hands and given up on news (I frankly do not blame them). Apple and Microsoft send audience to news. Jeff Bezos saved The Post. We need more of this kind of help. JCPA does nothing to make news sustainable.

Should news even be copyrighted?The legislation in the U.S., Australia, and Canada, as well as Germany’s Leistungsschutzrecht, Spain’s link tax, and the EU’s resulting Article 15 are all attempts to extend copyright.

In The Gutenberg Parenthesis, I also write about the origins of copyright. Note well that at the start, in the Statute of Anne of 1710 and in the first American copyright laws, news was explicitly not included. Not until 1909 in the United States did copyright law include newspapers, but even still, according to Will Slauter in Who Owns the News?, some still debated whether news articles, as opposed to literary features, were protected, for they were the product of business more than authorship.

The first, best government subsidy newspapers received was a franking privilege from the Post Office, starting in 1792, which allowed publishers to exchange editions with each other for the express purpose of copying each others’ news. This, too, from my book: “Newspapers employed ‘scissors editors’ to compile columns of reports from other papers. Editors would not complain about being copied because they copied in turn — but they would protest and loudly about not being credited…. It is ironic that newspapers — which since their founding in Strasbourg in 1605 have been compiled from news created by others — today complain that Google, Facebook, et al steal their property and value by quoting headlines and snippets from articles in the process of sending them readers via links. The publishers receive free marketing.”

I came to learn that copyright was created not to protect creators. Instead, copyright turned creation into a tradable asset, benefitting the publishers and producers who acquired rights from writers.

Just as a thought experiment, instead of extending copyright as so many legacy publishers in league with legislators wish to do, let us imagine what journalism might be today without copyright.

Without copyright, news organizations might not concentrate, as they do now, on the notion of journalism as a product to be restricted and sold to the privileged who can afford it. They are returning news to what it was before the printing press, when it was contained in expensive, exclusive newsletters called avvisi. Meanwhile, disinformation, lies, and propaganda will always fly free.

Without copyright, journalists might see news as a service that individuals and communities could choose to support — as they do public radio, The Guardian, and countless newsletters — because it is useful to them.

Without copyright, journalists might then concentrate on creating service of original value rather than employing digital scissors editors to rewrite each others’ stories into trending clickbait to make their own content to fill their own pages to attract their own SEO and social links to feed ever-decreasing programmatic CPMs.

Without copyright, they might turn all that wasted journalistic labor and talent loose on watching, reporting on, and holding accountable the politicians they are instead now lobbying.

Without copyright and the Gutenberg-era notions of content, property, and product, journalists might also feel freer to collaborate with the public, rather than speaking and selling to the public. Journalists might come to center journalism in the community rather in themselves, as we teach in our Engagement Journalism program at Newmark.

Without copyright, journalism might no longer be seen as a widget to be used as a wedge but instead a contributor to the quality of public discourse.

Do I want to get rid of copyright for news? Actually, yes, I do. I know that is not going to happen. But I can at least beg my legislators — I am looking at you, Cory Booker — not to extend and mangle copyright in the service of hedge funds and failed newspaper monopolists. Instead, let us find ways and means to support collaboration and innovation to improve news.

* The Gutenberg Parenthesis is scheduled to be published by Bloomsbury in June. You can be assured I would be sending you to a preorder link now if it existed, but it won’t until November. Watch this space.

The post Publishers’ political blackmail appeared first on BuzzMachine.

September 9, 2022

What is happening to TV?If AI made TV: I asked Dreamstudi...

If AI made TV: I asked Dreamstudio for an old TV set with Shakespeare in a sitcom

If AI made TV: I asked Dreamstudio for an old TV set with Shakespeare in a sitcomTV has had more supposed golden ages than the Queen had bling: Sid Cesar’s brief blip during TV’s infancy was hailed as one such shimmering age only because what followed — America stranded on Gilligan’s Island — was so unbearable as to make his Show of Shows’ Vaudeville shtick seem worthy of nostalgia. On broadcast, Cosby — yes, that Cosby, but only at the beginning — and Hill Street Blues marked a prime-time pop-cultural high. Then with cable’s freedoms came what I think of as TV’s real golden age, spanning The Sopranos to Succession.

TV today is certainly in no golden age. Prime-time, broadcast TV is profoundly self-parodic, populated with sitcoms that look as if they ran out of Viagra, cop- and doc-shows exhibiting the production and thespian quality of telenovelas, and “reality” shows that have lost any hold on reality. On premium cable, I pay for HBO and Showtime every damned month, watching none of it, waiting for Billions and Succession. On regular cable, I let MSNBC doomscroll the news for me — in between commercials for butt-cheek cream and dancing poop emojis (have they no standards?) — and then gratefully fall asleep to Guy Fieri’s comfort food. Netflix is so dark it has become Black Mirror. I dread subscribing to Apple TV+, Disney+, Discovery+, ESPN+, and all the other pluses for fear of what it will take to cancel them. Just yesterday, I received an actual letter delivered by the Post Office from Amazon saying, “We’re sending you this letter because you are an Amazon prime member who has not recently used any of the video benefits available to you.”

I was, for many years, a TV critic: the Couch Critic at TV Guide, the first TV critic at People, and founder of Entertainment Weekly. I was born with and grew up with TV. In the day, I defended television, which was almost as difficult as defending the internet is now. Of course, there are still good things to watch on TV. But given the medium’s current state, I am concerned about its health. Consider recent developments:

The Times reported that NBC is considering handing over its 10 p.m., prime-time hour to local stations — which is even more of a surrender than giving it to Jay Leno. This week, The Times valiantly tried to find 41 shows to recommend this fall — only five from network prime time, the rest mainly found in the bottoms of barrels — while the newspaper’s own critics mourn the death of fall TV. (I, too, am old enough to remember when fall brought new TV series and car models instead of just new phones.)

If network prime time has lost its value, so have networks, so has television, so has broadcast.

Cord-cutting continues apace, so cable is ailing, too. Thus all Hollywood is rushing to stream. Nielsen just reported that, for the first time, streaming surpassed both broadcast and cable in time spent watching in the U.S.:

But hold off writing that hot take about streaming taking over the world. Even as it triumphs in viewing time, The Washington Post declares that streaming “is having an existential crisis, and viewers can tell.” Take HBO, lately acquired by Discovery, which is merging the former’s streaming network, HBO Max, with the latter’s, Discovery+. To streamline — to cut costs — both are not just canceling shows but erasing them from the archives and even from social-media mentions. Netflix, which last year spent $13.6 billion on programming, is panicking, cutting back, and adding ads. Writers, producers, and actors are panicking, too, as they are finding fewer buyers for their output in Hollywood’s new monopsony — that is, a market with fewer and fewer buyers. There are only five corporate-conglomerate major studios now: Universal (NBC), Paramount (née Viacom), Warner (ex Time Warner, ex AT&T, now Discovery), Disney, and Columbia (Sony). And don’t forget that Amazon bought MGM.

Why is this happening now? In a fascinating Twitter thread, University College London researcher G. Vaughn Joy said we are rapidly reverting to the bad old days of Hollywood’s studio system. Recall that in those days, five all-powerful studios controlled entertainment from end to end, from production to distribution to exhibition. A 1948 Supreme Court anti-trust decision led to the Paramount Decree, forcing studios to divest their movie theaters. In the happy heyday since, independent theaters and production companies flourished.

Unbeknownst to me and maybe to you, in 2020 Trump’s anti-anti-trust Justice Department asked the court to sunset the Paramount Decree because, well, times have changed. That took effect just last month.

So again, how is this relevant now?

— V for Vaughndetta (@gvaughnjoy) September 5, 2022

The Paramount Accords were reversed in August 2020, set for a sunsetting period of two years which puts us at OH LAST MONTH. WHEN WB STARTED EATING ITSELF AND SHIT STARTED HITTING THE FAN IN HOLLYWOOD AND WE'RE ALL LIKE WHY ARE THEY DOING THIS pic.twitter.com/A3qANttMqQ

So now big studios can once again lock up vertical integration in entertainment, from production to distribution to exhibition, not in movie theaters — they are rapidly going bankrupt — but on your small screen via their streaming services. There is no longer a bright line between movies and TV shows, between broadcast and cable, between production and distribution; it’s all a stew of stuff flowing by your house in streams, each with a toll booth.

We tend to think of media as immutable institutions. But nothing in media is forever. In addition to my big book, The Gutenberg Parenthesis, coming out next year from Bloomsbury (more plugs coming soon), I’ve been writing a short book on the magazine as object (also for Bloomsbury). In my research and reminiscences, I come to see that all media artifacts — a magazine, a show, a series, a newspaper, a channel — are evanescent, like a bubble in the champagne glass of time; ultimately, so is any medium: television, radio, magazine, movie. I’ll get to the book in a minute.

Is this the internet’s fault? Yes, for once it is. What the net destroys is scarcity and scale. It kills the blockbuster. It massacres mass media. But isn’t the internet all about scale, you ask? Yes, but in a network ecology, it is that unprecedented scale that permits anyone connected to it to speak, to create, to collaborate, to share. We didn’t end up in a 500-channel world but in a five-billion-network world, each unique. So now there is an abundance of voice and creativity and every old medium — each of which trafficked in scarcity of space, time, talent, or attention — must now compete in a marketplace of abundance. The first reflex of old media is invariably wrong: to seek protection against new competitors by lobbying in Congress and courts, to buy up competitors to become bigger yet (see: Discovery + Warner), to reduce costs and thus quality, to raise prices.

All media are affected. The newspaper industry is consolidating into the hands of hedge funds and is engaging in profound journalistic conflict of interest by lobbying for protectionist legislation (one attempt just failed). The magazine industry is consolidating (see once-mighty Time Inc., sold into homemaker heaven Meredith, and sold in turn to content sweatshop Dotdash, with various of their magazines — including my own Entertainment Weekly — folded along the way). The book industry is trying to hold onto its old ways; see this saga about the resource and risk poured into making just one book a best-seller; how can this be sustained and how often can it succeed? The music industry did all this and more until it finally saw the light, clawed back, and found growth in a new abundance of talent, genres, and fans.

What comes next? At first, what comes next is inevitably derivative of what was. Marshall McLuhan said “the ‘content’ of any medium is always another medium,” that is, the medium that came before. See how, a few years ago at Vidcon, YouTube was pushing shows that looked a lot like old TV series.

YouTube has since killed much of this effort because it was expensive and didn’t work. Of course, it wouldn’t. YouTube should not aspire to be TV. It still must figure out what it means to be YouTube.

What we are left with today is a mess. TV and movies are still hoping for blockbusters and so they invest only in what they believe are sure things — Game of Thrones the Presequel House of Dragons — and otherwise, they fill their channels with cheap pap. Producers, writers, and actors will no longer find studios willing to back the endless credits of their big-budget productions. Streaming services will fold as viewers get frustrated paying for crap.

In each medium before, it took time to invent new, native genres. In The Gutenberg Parenthesis, I recount a rush of innovation that came a century and a half after movable type with the creation of the essay, the novel, and the newspaper. In my magazine research, I saw how new forms met new opportunities and needs: how Harper’s started in 1850 with a mission to curate a new abundance of content; how Godey’s found value in women as a new market; how Ebony outlasted Life and Look as white people abandoned their picture magazines when they saw themselves on TV but Black people did not; how Henry Luce and Briton Hadden invented not only the newsmagazine but the media corporation. As a TV critic, I came to appreciate the sitcom as well as the series, the miniseries, and the soap opera as genres native to the medium.

What will the new, native genres for the post-mass, post-theater, post-broadcast, post-blockbuster internet ecosystem look like? I cannot know. They are only now being germinated, mostly by people who could not have survived the gauntlet of old media. I think we see hints of that future in TikTok, which to my mind is the first truly collaborative creative platform original to the net (thus: Ratatouille the TikTok Musical and the Unofficial Bridgerton Musical, which is being sued by big, bad Netflix). We see hints, too, in Wattpad, a receptacle for the energy and affection of fan fiction. No, I am not saying this is the future of culture, only that that future can come from unexpected places. While the big, old companies try desperately to hold onto their control, cultural insurgents will undermine them.

I’ve been thinking about the institutions of culture and media — editing, publishing, networks, and so on — and what we may lose if or when they disappear. I celebrate the fall of the gatekeepers who restricted media to the privileged and powerful, the elite and highbrow. I am glad for the end of the Cronkitization of journalism and civic life: the hubris that one old, white man could speak to and for all. I am happy to see our sitcom addiction to happy endings fall to the messy realism of, say, Breaking Bad. I do not miss the paternalistic nature of mass media, but I do regret that media today have not maintained its sense of mission; see how network TV entered into public discourse about bigotry (Roots, All in the Family, Will & Grace) but is all but silent today on evangelical white supremacy and authoritarianism.

We may miss past institutions’ contributions to the culture — finding, nurturing, goading talent — until these institutions are eventually replaced as needs demand.

I believe culture will come out the other end better for the turmoil: more representative, less exploitative, less expensive, more collaborative, more inventive. In the meantime? It’ll be a mess.

The post appeared first on BuzzMachine.

August 18, 2022

The story media miss: themselves

Media are not merely observers in the story of democracy’s demise; they are players. Media require coverage. Who will cover media? Not media. Then no one.

The New York Times and The Washington Post eliminated their ombudsmen long since. With the death of David Carr and the departure of his short-lived and inconsequential successors, with the retirement of Margaret Sullivan, and now with the cancellation of Brian Stelter’s Reliable Sources on CNN, there is no one covering media as a story for the public. Yes, there are pontificators aplenty — present company included — and there is inside-baseball coverage for media people from the likes of the Columbia Journalism Review. But who is holding media to account for its impact on the political process for the public? No one.

This is a shameful abrogation of responsibility by our field, journalism.

I have been shouting — even on MSNBC’s air — that we must cover the impact of Murdoch’s Fox News on public discourse. I begged MSNBC to create a feature: We watch Fox News so you don’t have to. I wrote an executive there a proposal, never answered. So I arranged funding of an alum of the Newmark J-School, Juliet Jeske, to start Decoding Fox News on Twitter and Substack. (Someone in media should hire her to continue this important work.)

Fox News is only part of the story. The impact The Times and The Post have on political discourse — hell, on political outcomes — deserves coverage, criticism, and accountability. The impact of polling, bisecting America into simplistic and combative binaries, requires research. The slow death of local news must be studied. The entrance of pink-slime and evangelical news needs to be watched.

Now more than ever, media are a story media should cover. But media — so eager to criticize everyone else — are frightened of criticism themselves.

Were I to summon the spirit of David Carr, I wonder whether he would nominate Stelter as his legitimate successor as media columnist of The Times. I wonder whether anyone would have the freedom Carr and Sullivan had there to question the ways of journalism. I wonder whether any editor or producer or network executive will ever again display the cajones to critique their own.

Media are not objective, impartial, neutral, distant observers on society. Media — as in any other circumstance, media otherwise would love to convince you — have impact. If only media gave themselves a fraction of the attention that they give to so-called social media these days. If only media listened to media scholars and their research. If only media were open to criticism.

But no, media use their power and privilege to to turn spotlight on others, no longer themselves. That is wrong.

The post The story media miss: themselves appeared first on BuzzMachine.

June 27, 2022

How harmful is it?

As the UK gets ready to regulate harmful (including legal but harmful) speech online, the appointed regulator, Ofcom, released its annual survey of users. It’s informative to see just how concerned UK citizens seem to be about the internet. Not terribly.

First, a list of potential “harms” encountered.

Let’s look at these. Scams (27%). Yes, We get those through every possible medium: phone, mail, and net. Misinformation (22%). Well, that requires definition. “Generally offensive or ‘bad’ language” (21%). Oh, that is so broad; it is in the ear of the beholder; and — even without a First Amendment — does government want to be in the position of policing “bad” language? Unwelcome friend requests (20%). Sounds like a bad cocktail party; one may easily walk away. Content encouraging gambling (16%). Gambling is legal in the UK and promoted by many newspapers, which profit from it.

The sixth and seventh complaints are ones worthy of attention and are mostly native to online: trolling (15%) and discriminatory content (11%). Other categories worthy of attention include objectification of women, bullying, unwanted sexual messages, and content about body image (each 8%).

Now how concerned are these users about their complaints? 15% are “really bothered.”

What did the complainers do about it? 30% scrolled past, 20% reported it, 20% unfollowed whoever posted the offending content, 18% did nothing, 11% closed the app or site…

That’s the complaint side of the report. It does not alarm me about the extent of online harm users are reporting to their regulator.

To its credit, Ofcom also asked about the benefits of the net for its citizens. These results are striking.

“Being online has an overall positive effect on my mental health.” Only 14% disagreed; two and a half times more users agreed that the net is good for their mental health.

Oh, but isn’t the net addictive and taking over our lives? To this statement — “I feel I have a good balance between my online and offline life — a solid majority of 74% agree; only 9% do not.

“I can share my opinions and have a voice.” I consider this a critical difference between the net and mass media. 44% agree; only 17% disagree; a third don’t share an opinion about sharing their opinions.

“I feel more free to be myself online.” A third agree; almost a fifth disagree; half, being British, shrug.

Many people see the net less as a means of self-expression and more as a useful helpmate. “Accessing goods and services online is more convenient for me.” A whopping 83% agree; a mere 3% disagree.

Rather than being imprisoned by the desires of algorithms, it seems people see themselves as individuals following their own desires. “It gives me space to pursue my hobbies and interests.” Almost two-thirds — 63% agree — while 11% do not.

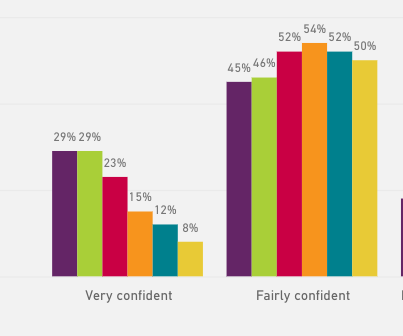

So far, as I read the survey, people feel predominantly positive about their use of the net and they do not seem terribly concerned about their complaints. The reason for a regulator to step in would be if users thought themselves incapable of handling problems there. Ah, but UK internet users do not paint themselves as desperate. To the contrary, they are confident: 79% call themselves very or fairly confident as internet users; not so much, 8%.

Well, what about attempts to pull the wool over their eyes by unscrupulous marketers? How confident are they that they can recognize online advertising? 78% are; 7% are not.

But data is/are a problem, everyone agrees, yes? Sure people feel they have lost the ability to manage their personal data online? Not so. A majority — 58% — are confident managing their data; 18% not.

OK, then fake news must be terrorizing citizens. News media say so. How many feel confident judging the truthfulness of online information? 69%; 9% feel otherwise.

A

ABut young people are the most vulnerable to online disinformation — that’s why there are so many interventions to teach them news literacy, right? How do young people compare with their elders? 29% of users aged 16–34 are very confident, and it goes downhill from there.

Most people feel pretty strongly about their own abilities online. But when asked about others, well, they need help. Two thirds of users agree with the statement, “Internet users must be protected from seeing inappropriate or offensive content.”

There we see the third-person effect at work. Coined by sociologist W. Phillips Davison in 1983, the third-person effect “predicts that people will tend to overestimate the influence that mass communications have on the attitudes and behavior of others…. Its greatest impact will not be on ‘me’ or ‘you,’ but on ‘them’ — the third persons.” The third-person effect, I argue in my upcoming book, is the basis of so much regulation and censorship of media since Gutenberg. Ofcom and fellow citizens want to protect them from the internet whether they think they need it or not.

All of this would seem to me to auger against the urgent need for Ofcom and the UK government to guard its citizens from the net.

But perhaps, as we hear in a constant media drumbeat, internet companies are negligent of doing anything to address the problems — problems that humans cause — on their platforms. Ofcom reports the moderation activity of the three big companies:

Facebook took down 153 million pieces of content in the third quarter of 2021 alone, 96% found by its algorithms. Is Facebook censoring too much, as America’s right-wing would claim? Only 2% of its decisions are challenged.

I know I’m being sassy here. I am not arguing against all regulation. The net is already regulated. Neither am I defending its current proprietors. I wish for a more distributed web (a la Jack Dorsey’s Bluesky). But keep in mind that a more distributed web will be much harder for regulators to regulate. And a more distributed web will make it more difficult for moral-panicking media to find folk-devil moguls to blame for all our ills.

Interventions in the internet and our newfound freedom of speech online need to be based on empirical evidence of actual harm, clearly defined. This, it would appear, is not that.

The post How harmful is it? appeared first on BuzzMachine.

May 24, 2022

Toward a journalistic ethic of citation

After The New York Times published its extensive report on the history of Haiti’s impoverishment at the hands of its overthrown colonial overlords, a robust debate broke out between academic and journalistic Twitter about inadequate citation and sourcing. Journalism must do better.

The gist of it: The Times did include a narrative bibliography in the project, which is unusual. But some academics — including Harvard’s Mary Lewis — said they had helped reporters but were neither quoted nor credited. This thread by Pittsburgh Prof. Keisha Blain brings together other threads; read them all. Many said The Times was derelict in not quoting and citing current research but also in ignoring the seminal work of Eric Williams in his 1944 book, Capitalism and Slavery — columbusing in, of all subjects, Haiti. Joseph Rezek, a BU professor, said the real problem was that The Times acted as if it had discovered something new when much research on the topic came before:

The hook for the article, that the NYT uncovered this about Haiti, is false; that is why people are mad. The narrative in the piece, about the debt, is good. The narrative of discovery is bad. Academics are not asking journalists to tell bad stories, just ones that are true.

— Joseph Rezek (@RezekJoe) May 22, 2022

After three days, The Times reported on the citation controversy but some said it still didn’t give credit where it is due. Some journalists — notably Adam Davidson — pleaded for citational slack in telling stories for general audiences, sparking more controversy. I entered in more than once to argue that journalists must practice better discipline of citation, sourcing, and transparency: showing our work.

There are so many lessons here for journalists and journalism students that I think it is important to try to catalog them, to examine the journalistic presumptions and problems at work, and to propose standards.

Don’t blame your tools. First, let me call bullshit on the usual excuses that journalists do not have the space, time, or appropriate CMS frippery to cite sources. We now have the internet, with unlimited space and time. And we have the best possible tool for citation — the link. If any news organization cared, it would take next to no effort to also update tools to accommodate footnotes, endnotes, or notes that are revealed at a user’s option; to compile bibliographies of sources; and to create open repositories for source material. What is standing in the way of responsible citation is not tools but ethical will.

Journalists must always cite their sources. I don’t just mean attributing quotes. Let’s be honest that too often, quotes in stories are a form of extraction: I (the reporter) got you (the expert) to fill in our (the news organization’s) preconceived narrative. Anyone who has ever been interviewed knows the experience of seeing a long conversation reduced to one out-of-context line included to exploit the expert’s reputation and to make the reporter’s point, not the speaker’s.

What’s more troubling in the case of the Haiti story is what Yasmin Nair calls soft plagiarism: not a direct quote lifted but instead the coopting of ideas, background, context, perspective, and most of all an academic’s research and expertise.

I have sometimes spent an hour or two on the phone with a reporter explaining concepts, context, or history: educating them, with nothing to show for it. Far worse is Siva Vaidhyanathan’s tale of being used and discarded by a PBS series. There are a million such tales.

So, journalists, in your story or in a supplemental bibliography — try it — find a way to cite your sources, all those who, through interviews or literature, gave you the gift of education. To do anything less is intellectual and reportorial theft.

Screw the scoop. The Haiti episode exposes a grave journalistic weakness: the addiction to the scoop, to the idea that everything we report must be new, thus news. That is presumed to be one reason The Times’ Haiti story did not acknowledge much prior research. Nikole Hannah-Jones tweeted an explanation: “Simply pitching the story as ‘this happened but many people don’t know about it[’] would likely have meant the piece didn’t get done & certainly that it wouldn’t have gotten all the resources.” She is, as ever, correct. But that indicates something seriously wrong with news organizations’ priorities. Shouldn’t serving what “many people don’t know” be more important than bragging about being the first to know it?

Look, too, at how journalists treat each other, not just academics. Here, NBC reporter Mike Hixenbaugh laments that neither The Times nor The Washington Post credited local Texas reporters with the reporting that led to the devastating report on Southern Baptist evangelical sex abuse.

There is no shame in acknowledging that others came before and in giving them — academics or journalists — recognition for their contributions. The shame is in not doing so.

The story corrupts. The story is not everything. The story is merely one form, one tool to inform the public. Failing to credit sources and experts because doing so would get in the way of the flow of one’s persuasive narrative is no excuse. I have long warned of the seduction of the story, as it grants too much power to the storyteller over the story’s subject. Keeping a narrative going while imparting information and crediting sources is simply our job.

It’s the business model, stupid. So much of this current kerfuffle revolves around the media economy requiring that news organizations to be destinations, to sell subscriptions, or (less and less) to sell attention to advertisers. As Jordan Taylor put it:

So let's not pretend that this is about how clear your writing is, and let's not pretend that hyperlinks or endnotes will deter readers. That's preposterous.

— Jordan E. Taylor (@PubliusorPerish) May 23, 2022

It's about optimizing your words for an attention economy.

In the end, this is not about ethics or credibility but about the fight we’ve been having since the internet entered newsrooms: Journalists and publishers don’t want to link out; they don’t want to give credit; they want to convince themselves and the people they still consider an audience that they are selling a unique, exclusive, valuable commodity called content.

Wrong. Journalism is a service. When we credit our sources and show our work, we enhance our credibility and value. When we exploit and extract the work of academics — particularly academics of color — we extend inequity and injustice. When we value our own journalistic egos over the reputations of our sources and the education of the public, we do harm.

So stop. Find every way you can to cite and credit the sources who make your stories — your articles, your reporting, your informational service — possible. If you do not, you are thieves.

Another thing. I hate it when journalists say academics cannot write well. Yes, it is easy to find academic papers intended for small audiences inside a discipline that use baffling jargon. This writing is not intended for a broad audience. But behind me I have bookshelves filled with wonderfully written books by academics filled with not only engaging narrative but also responsible citation of rich sets of sources. So let’s cut out our intramural sniping about who’s a better writer.

To the contrary, it is vital — urgent — that we bring academics and journalists closer together so that news organizations are exposed to, use, and cite academic research relevant to their reporting. This is one of the reasons why I started an Initiative in Internet Studies at CUNY’s Newmark Journalism School — in full disclosure, funded by Google — to highlight research on internet impact for journalists and policymakers. (The Initiative is also bringing researchers together to discuss their agendas and I’m working to develop an educational program; my colleague Douglas Rushkoff and I just completed teaching a course in (re)Designing the Internet).

Diara J. Townes, who has worked with First Draft and the Aspen Institute and is a graduate of our school, is leading the effort to find, highlight, summarize, and share relevant research on internet impact. Here is the Twitter account where she is sharing research — and please send her more. Here is her Medium site and here you can sign up for her newsletter.

We in journalism mustn’t build walls to exclude academics by ignoring their prior research, by extracting their work without credit, and by mocking their writing (there is plenty to mock in news writing, folks). Instead, in a time when debate is devoid of fact and data, we must come closer together.

Just as I hit “publish” on this post, a colleague sent me a very good piece by Jonathan Katz, a “Haiti-head” — alongside his wife, Claire Payton, who holds a Ph.D. in Haitian history. Katz examines what is new in The Times project. He concludes:

My journalism-school superego says that a more honest thing for them to do would have been to package the story as what it was — a significant but incremental advance in the understanding of a historical event that scholars and Haitians know about and that much of the rest of the world does not.

But would a single front-page story with a headline like France Stole Over $500 Million from Haiti In 19th Century, Times Analysis Shows — or maybe In an Impoverished County, a Legacy of Theft — have gotten the magnitude of attention that this reporting has so far? Probably not.

Attention from The Times’ editors? I agree; probably not. But attention from the audience? That’s up to The Times’ editors. Nothing would have stopped The Times from doing just what Katz does here, saying: Here’s a story you probably don’t know; let us tell it to you and then let us tell you some new facts we uncovered in our research. Journalism is never the first-draft of history; that is our worst and most inexcusable hubris. Journalism is always another chapter in history.

The post Toward a journalistic ethic of citation appeared first on BuzzMachine.

April 27, 2022

Concede defeat to bad speech

What if we concede that the battle against “bad speech” is lost? Disinformation and lies will exist no matter what we do. Those who want such speech will always be able to say it and find it. Murdoch and Musk win. That is just realism.

Then what? Then we turn our attention to finding, amplifying, and supporting quality speech.

A big problem with concentrating so much attention and resource on “bad speech,” especially these last five years, is that it allows — no, encourages — the bad speakers to set the public agenda, which is precisely what they want. They feed on attention. They win. Even when they lose — when they get moderated, or in their terms “censored” and “canceled,” allowing them to play victim — they win. Haven’t we yet learned that?

Another problem is that all speech becomes tarred with the bad speakers’ brush. The internet and its freedoms for all are being tainted, regulated, and rejected in a grandly futile game of Whac-A-Mole against the few, the loud, the stupid. Media’s moral panic against its new competitor, the net, is blaming all our ills on technology (so media accept none of the responsibility for where we are). I hear journalists, regulators, and even academics begin to ask whether there is “too much speech.” What an abhorrent question in an enlightened society.

But the real problem with concentrating on “bad speech” is that no resource is going to good speech: supporting speech that is informed, authoritative, expert, constructive, relevant, useful, creative, artful. Good speech is being ignored, even starved. Then the bad speakers win once more.

What does it mean to concentrate on good speech? At the dawn of print and its new abundance of speech, new institutions were needed to nurture it. In my upcoming book, The Gutenberg Parenthesis (out early next year from Bloomsbury Academic), I tell the story of the first recorded attempt to impose censorship on print, coming only 15 years after Gutenberg’s Bible.

In 1470, Latin grammarian Niccolò Perotti begged Pope Paul II to impose Vatican control on the printing of books. It was a new translation of Pliny that set him off. In his litany of complaint to the pope, he pointed to 22 grammatical errors, which much offended him. Mind you, Perotti had been an optimist about printing. He “hoped that there would soon be such an abundance of books that everyone, however poor and wretched, would have whatever was desired,” wrote John Monfasani. But the first tech backlash was not long in coming, for Perotti’s “hopes have been thoroughly dashed. The printers are turning out so much dross.”

Perotti had a solution. He called upon Pope Paul to appoint a censor. “The easiest arrangement is to have someone or other charged by papal authority to oversee the work, who would both prescribe to the printers regulations governing the printing of books and would appoint some moderately learned man to examine and emend individual formes before printing,” Perotti wrote. “The task calls for intelligence, singular erudition, incredible zeal, and the highest vigilance.”

Note well that what Perotti was asking for was not a censor at all. Instead, he was envisioning the roles of the editor and the publishing house as means to assure and support quality in print. Indeed, the institutions of editor, publisher, critic, and journal were born to do just that. It worked pretty well for a half a millennium.

Come the mechanization and industrialization of print with steam-powered pressed and typesetting machines — the subject of future books I’m working on — the problem arose again. There was plenty of proper complaint about the penny press and yellow press and just crappy press. But at that same time, early in this transformation in 1850, a new institution was born: Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. See its mission in the first page of its first issue:

Rather than trying to eradicate all the new and bad speech suddenly appearing, Harper’s saw the need to support the good, “to place within the reach of the great mass of the American people the unbounded treasures of the Periodical Literature of the present day.”

Magazines — which Ben Franklin and Noah Webster had tried and failed to publish — flourished with new technology, new audiences, and new economics as good speech begat more good speech.

I am not suggesting for a second that we stop moderating content on platforms. Platforms have the right and responsibility to create positive, safe, pleasing, productive — and, yes, profitable — environments for their users.

But it is futile to stay up at night because — in the example of the legendary XKCD cartoon — someone is wrong, stupid, or mean on the internet. People who want to say stupid shit will find their place to do it. Acknowledge that. Stop paying heed to them. Attention is their feed, their fuel, their currency. Starve them of it.

I also am not suggesting that supporting good speech means supporting the incumbent institutions that have failed us. Most are simply not built to purpose for the new abundance of speech; there aren’t enough editors, publishers, and printing presses to cope.

Some of these legacy institutions are outright abrogating their responsibility: See The New York Times believing that the defense of democracy is partisan advocacy. Says the new editor of The Times: “I honestly think that if we become a partisan organization exclusively focused on threats to democracy, and we give up our coverage of the issues, the social, political, and cultural divides that are animating participation in politics in America, we will lose the battle to be independent.” No one is suggesting this as either/or. I give up.

Instead, supporting good speech means finding the speech that has always been there but unheard and unrepresented in the incumbent institutions of mass media. Until and unless Musk actually buys and ruins Twitter, it is a wealth of communities and creativity, of lived perspectives, of expertise, of deliberative dialogue — you just have to be willing to see it. Read André Brock, Jr.’s Distributed Blackness to see what is possible and worth fighting for.

Supporting good speech means helping speakers with education, not to aspire to what came before but to use the tools of language, technology, collaboration, and art to express themselves and create in new ways, to invent new forms and genres.

Supporting good speech means bringing attention to their work. This is why I keep pointing to Jack Dorsey’s Blue Sky as a framework to acknowledge that the speech layer of the net is already commodified and that the opportunity lies in building services to discover and share good speech: a new Harper’s for a new age built to scale and purpose. I hope for editors and entrepreneurs who will build services to find for me the people worth hearing.

Supporting good speech means investing in it. Millions have been poured into tamping down disinformation and good. I helped redirect some of those funds. We needed to learn. I don’t regret or criticize those efforts. But now we need to shift resources to nurturing quality and invention. As one small example, see how Reddit is going to fund experiments by its users.

We need to understand “bad speech” as the new spam and treat it with similar disdain, tools, and dismissal. There’ll always be spam and I’m grateful that Google, et al, invest in trying to stay no more than one foot behind them. We need to do likewise with those who would manipulate the public conversation for more than greedy ends: to spread their hate and bile and authoritarian racism and bigotry. Yes, stay vigilant. Yes, moderate their shit. Yes, thwart them at every turn. But also take them off the stage. Turn off the spotlight on them.

Turn the spotlight onto the countless smart, informed, creative people dying to be seen and heard. Support good speech.

The post Concede defeat to bad speech appeared first on BuzzMachine.

March 5, 2022

Where is our moral line in Ukraine?

https://twitter.com/pollari_tapani/st...

https://twitter.com/pollari_tapani/st...A thread I posted on Twitter, asking questions:

It is likely a mistake to think aloud here on Twitter but I will confess I am unsure what to think about US/NATO involvement in a no-fly zone over Ukraine. I am gun-shy, literally, after my errors regarding Iraq. But…

How can we allow this democracy to be destroyed by fascism? Generals on TV say we must do more but then stop short of specifying what “more” is. Ukraine is asking for help to establish a no-fly zone as Russia bombards their country. So that is the question.

The reflexive answer is that we will defend NATO lands. So we will not defend Finland? Sweden? Any nation in the world not in NATO? Because Russia has nuclear weapons? That turns into quite a broad license for Putin.

The presumption seems to be that once we engage in protecting Ukraine, Putin has license to escalate to nukes. He might anyway. Then what? Is *that* the line? Ironically, then, the nuclear argument is its own form of escalation, almost daring him to use them or do everything but.

I know this is a helluva lot easier for me to say safely in America. I acknowledge again that thinking the US needed to support the democratic aspirations of the people of Iraq was dangerously naive of me. I am sobered by the perils at hand. But…

I am also aware that the Bush/Neocon/LindseyGraham extension of that reasoning would be to instigate regime change in Russia. No, I am not saying that! But Russia is instigating regime change in Ukraine. Do they not deserve protection?

We have a moral question to address: What is our obligation to Ukraine? What is the line? War crimes are being committed before our eyes: targeting civilians, using cluster bombs. Will we stand by to see Ukraine as Chechnya? Where is our line?

I have no interest in entering war. Even with the difficult exit from Afghanistan, I am gratified that Biden has taken America off the battlefield for the first time in decades.

I ask all this because I am interested in others’ perspectives. If this thread turns into a shouting mess, I’ll delete it. But if you, too, are trying to grapple with these questions, I’d like to hear others’ thoughts.

I grew up with the Vietnam War on TV. It made me anti-war, a young pacifist. Perhaps best if I’d stuck with that rather than accepting the idea of human rights & democratic aspiration in Afghanistan, then Iraq. Surviving 9/11 at the WTC affected me, I will confess.

Now we watch the Ukrainian war up close on social media, not through the mediator of TV but hearing directly from the civilians being targeted. This forces us to examine our own moral stands.