Jeff Jarvis's Blog, page 11

January 21, 2020

The next net: expertise

The net is yet young and needs to learn from its present failures to build a better infrastructure not just for speaking but also for listening and finding that which is worth listening to, from experts and people with authority, intelligence, education, experience, erudition, good taste, and good sense.

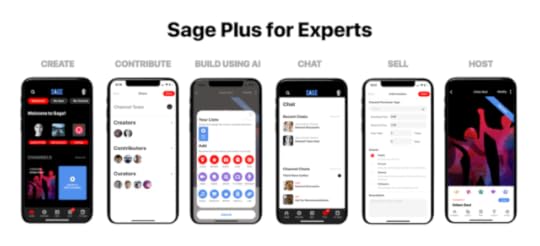

Here is a preview of one nascent example of such a system built on expertise from Samir Arora, the former CEO of Glam. Samir and I bonded a dozen years ago over the power of networks, when he came to my office to show me one history’s ugliest Powerpoint slides, illustrating how open networks of independent blogs at Glam bested closed systems of owned content in a media company. I had been beating the same drum. Glam later imploded for many reasons, among them the change in the ad market with programmatic networks and investor politics.

Next Arora quietly set to work on Sage, a network of experts. It’s not public yet — he and his team plan to open it up in the first or second quarter — and it’s a complex undertaking whose full implications I won’t fully understand until we see how people use it. But as before, I think Arora is onto an important insight.

He started with a manageable arena: travel and food — that is, expertise about places. That topic made it easier to connect what someone says with a specific destination, hotel, or restaurant; to compare what others said about these entities; and to judge whether someone was actually there and spoke from experience as a test of credibility and accuracy.

I’ve begged Arora to also tackle news but watching him grapple with expertise — at the same time I’ve watched the platforms struggle with quality in news — it becomes apparent that every sector of knowledge will need its own methodology. Sports can probably operate similarly to travel. Health and science will depend on accredited institutions (i.e., people with degrees). Culture will be sensitive to, well, cultural perspective. International affairs will require linguistic abilities. Politics and expertise is probably oxymoronic.

Sage began with 100 manually curated experts in travel. Asking the experts to in turn recommend experts and analyzing their connections yielded a network of 1,000 experts with opinions about 10,000 places. Then AI took that learning-set to scale the system and find 250k experts and influencers with their judgments about 5 million places. 250k is a lot of sources, but it’s not 1.74 billion, which is how many web sites there are. It’s a manageable set from which to judge and rank quality.

I probably would have stopped there and released this service to the public as a new travel and restaurant search engine built on a next generation Google’s page rank that could identify expertise and control for quality and gaming. Or I’d license the technology to social platforms, as Twitter’s Jack Dorsey has been talking about finding ways to present expertise in topics and Facebook is in constant search for ways to improve its ranking.

But Arora did not. His reflex is to create tools for creators, going back to his cofounding of NetObjects in 1995, which built tools to build web sites. At Glam, he bought Ning, a tool that let any organization build its own social network.

So, at Sage, Arora is creating a suite of tools that enable an expert who has been vetted in the system to interact with users in a number of ways. The system starts by finding the content one has already shared on the web — on media sites, on Instagram or Pinterest, on YouTube, on blogs, in books, wherever — allowing that person to claim a profile and organize and present the content they’ve made. It enables them to create your own channels — e.g., best sushi — and their own lists within it — best sushi in L.A. — and their own reviews there. They can create content on Sage or link to content off Sage. They can interact with their users in Q&As and chats on Sage.

Because Arora is also reflexively social, he has built tools for each expert to invite in others in a highly moderated system. The creator can ask in contributors who may create content and curators who may make lists. Sage is also going to offer closed networks among the experts themselves so they will have a quality environment for private discussions, a Slack for experts. So creators can interact with the people they invite in, with a larger circle of experts, with the public in a closed system for members and subscribers, or with the public at large.

And because the real challenge here is to support creativity and expertise, Sage is building a number of monetization models. You can link to your content elsewhere on the web with whatever business models are in force there. You can offer content for free. You can set up a subscription model with previews (the meter) and one-time purchase (an article or a book). You can sell access to an event: an online Q&A, an individual consulting session, an in-person appearance, and so on. And you can sell physical products — a cookbook, a box of hot sauces — directly or via affiliate arrangements. Plus you can accept donations at various tiers as a kind of purchase. Note that Sage will begin without advertising.

I hope this platform could place where newly independent journalists covering certain topics could build an online presence and make money from it.

All this is mobile-first. Experts can build content within Sage, on the open web, and — if they have sufficient followers — in their own apps. The current iteration is built for iOS with Android and web sites in development. (Since I live la vida Google in Android, I haven’t been able to dig into it as much as I’d like.)

Users will discover content on Sage via search on topics or by links to experts’ channels there.

After starting with restaurants and travel, Sage is expanding into culture — reviews of books and movies. Next comes lifestyle, which can include health. News, I fear, will be harder.

So what is expertise? The answer in old media and legacy institutions was whatever they decided and whomever they hired. In a more open, networked world, there will be many answers, yours and mine: I will rely on one person’s taste in restaurants, you another. The problem with this — as, indeed, we see in news and political views today — is that this extreme relativity leads to epistemological warfare, especially when institutions old (journalism) and new (platforms) are so allergic to making judgments and everyone’s opinions are considered equal. I am not looking for gatekeepers to return to decide once for all. Neither do I want a world in which we are all our own experts in everything and thus nothing. Someone will have to draw lines somewhere separating the knowledgeable from the ignorant, evidence from fiction, experience and education from imagination and uninformed opinion.

Will Sage be any good at this task? We can’t know until it starts and we judge its judgments. But Arora gave me one anecdote as a preview: About 18 months ago, he said, Sage’s systems sent up an alert about a sudden decline in the quality and consistency of reviews from a well-known travel brand. Staff investigated and, sure enough, they found that the brand had fired all its critics and relied on user-driven reviews from an online supplier.

This is not to say that users cannot be experts. As Dan Gillmor famously said in the halcyon early days of blogs and online interaction: “My readers know more than I do.” In aggregate and in specific cases, he’s right. I will take that attitude over that of an anonymous journalist quoted in a paper I just read about foundations requiring the newsrooms they now help support to engage with the public:

The people are not as knowing about a story as I am. They haven’t researched the topic. They haven’t talked to a lot of people outside of social circles. I read legal briefs or other places’ journalism. I don’t think people do that. It can become infuriating when my bosses or Columbia Journalism Review or Jeff Jarvis tells me I’m missing an opportunity by not letting people tell me what to do. I get the idea, you know, but most people are ignorant or can’t be expected to know as much as I do. It’s not their job to look into something. They aren’t journalists.

No. Expertise will be collaborative and additive. That is the lesson we in journalism never learned from the academe and science. Reporters are too much in the habit of anointing the one expert they find to issue the final word on whatever subject they’re covering: “Wine will kill us!” says the expert. “Wine will save us!” says the expert. As opposed to: “Here’s what we know and don’t know about wine and health and here is the evidence these experts use to test their hypotheses.”

What we will need in the next phase of the net is the means to help us find people with the qualifications, experience, education, and means to make judgments and answer questions, giving us the evidence they use to reach their conclusions so we can judge them. Artificial intelligence will not do this; neither will it replace expertise. The question is whether it can help us sift through the magnificent abundance of voice and view to which we now have access to help us decide who knows what the fuck they’re talking about.

(You can apply to join Sage for Experts here.)

The post The next net: expertise appeared first on BuzzMachine.

January 10, 2020

In defense of targeting

In defending targeting, I am not defending Facebook, I am attacking mass media and what its business model has done to democracy — including on Facebook.

With targeting, a small business, a new candidate, a nascent movement can efficiently and inexpensively reach people who would be interested in their messages so they may transact or assemble and act. Targeted advertising delivers greater relevance at lower cost and democratizes advertising for those who could not previously afford it, whether that is to sell homemade jam or organize a march for equality.* Targeting has been the holy grail all media and all advertisers have sought since I’ve been in the business. But mass media could never accomplish it, offering only crude approximations like “zoned” newspaper and magazine editions in my day or cringeworthy buys for impotence ads on the evening news now. The internet, of course, changed that.

Without targeting, we are left with mass media — at the extreme, Super Bowl commercials — and the people who can afford them: billionaires and those loved by them. Without targeting, big money will forever be in charge of commerce and politics. Targeting is an antidote.

With the mass-media business model, the same message is delivered to all without regard for relevance. The clutter that results means every ad screams, cajoles, and fibs for attention and every media business cries for the opportunity to grab attention for its advertisers, and we are led inevitably to cats and Kardashians. That is the attention-advertising market mass media created and it is the business model the internet apes so long as it values, measures, and charges for attention alone.

Facebook and the scareword “microtargeting” are blamed for Trump. But listen to Andrew Bosworth, who knows whereof he speaks, as he managed advertising on Facebook during the 2016 election. In a private post made public, he said:

So was Facebook responsible for Donald Trump getting elected? I think the answer is yes, but not for the reasons anyone thinks. He didn’t get elected because of Russia or misinformation or Cambridge Analytica. He got elected because he ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser. Period….

They weren’t running misinformation or hoaxes. They weren’t microtargeting or saying different things to different people. They just used the tools we had to show the right creative to each person.

I disagree with him about Facebook deserving full blame or credit for electing Trump; that’s a bit of corporate hubris on the part of him and Facebook, touting the power of what they sell. But he makes an important point: Trump’s people made better use of the tools than their competitors, who had access to the same tools and the same help with them.

But they’re just tools. Bad guys and pornographers tend to be the first to exploit new tools and opportunities because they are smart and devious and cheap. Trump used it to sell the ultimate elixir: anger. Cambridge Analytica acted as if it were brilliant at using these tools, but as Bosworth also says in the post — and as every single campaign data expert I know has said — CA was pure bullshit and did not sway so much as a dandelion in the wind in 2016. Says Bosworth: “This was pure snake oil and we knew it; their ads performed no better than any other marketing partner (and in many cases performed worse).” But the involvement of evil CA and its evil backers and clients fed the media narrative of moral panic about the corruption and damnation of microtargeting.

Hillary Clinton &co. could have used the same tools well and at the time — and still — I have lamented that they did not. They relied on traditional presumptions about campaigning and media and the culture in a changed world. Richard Nixon was the first to make smart use of direct mail — targeting! — and then everyone learned how to. Trump &co. used targeting well and in this election I as sure as hell hope his many opponents have learned the lesson.

Unless, that is, well-meaning crusaders take that tool away by demonizing and even banning micro — call it effective — targeting. I have sat in too many rooms with too many of these folks who think that there is a single devil and that a single messiah can rescue us all. I call this moral panic because it fits Ashley Crossman’s excellent definition of it:

A moral panic is a widespread fear, most often an irrational one, that someone or something is a threat to the values, safety, and interests of a community or society at large. Typically, a moral panic is perpetuated by news media, fueled by politicians, and often results in the passage of new laws or policies that target the source of the panic. In this way, moral panic can foster increased social control.

The corollary is moral messianism: that outlawing this one thing will solve it all. I’ve heard lots of people proclaiming that microtargeting and targeting — as well as the data that powers it — should be banned. (“Data” has also become a scare word, which scares me, for data are information.) We’ve also seen media — in cahoots with similarly threatened legacy politicians — gang up on Facebook and Google for their power to target because media have been too damned stubborn and stupid, lo these two decades, to finally learn how to use the net to respect and serve people as individuals, not a mass, and learn information about people to deliver greater relevance and value for both users and advertisers. I wrote a book arguing for this strategy and tried to convince every media executive I know to compete with the platforms by building their own focused products to gather their own first-party data to offer advertisers their own efficient and effective value and to collaborate as an industry to do this. Instead, the industry prefers to whine. Mass media must mass.

Over the years, every time I’ve said that the net could enable a positive, I’ve been accused of technological determinism. Funny thing is, it’s the dystopians who are the determinists for they believe that a technology corrupts people. It is patronizing, paternalistic, and insulting to the public and robs them of agency to believe they can be transformed from decent, civilized human beings into raging lunatics and idiots by exposure to a Facebook ad. If we believe that and believe our problems are so easily fixed then we miss the real problems this country has: its long-standing racism; media’s exploitation and fueling of conflict and fear; and growing anti-intellectualism and hostility to education.

We also need to fix advertising — in mass media and on the internet in the platforms, especially on Facebook. Advertising needs to shift from mass-media measures of audience and attention and clicks to value-based measures of relevance and utility and efficacy — which will only occur with, yes, targeting. It also must become transparent, making clear who is advertising to us (Facebook may confirm the identity of an advertiser but that confirmed information is not shared with us) and on what basis we are being targeted (Facebook reveals only rough demographics, not targeting goals) and giving us the power to have some control over what we are shown. Instead of banning political advertising, I wish Twitter would also have endeavored to fix how advertising works.

I hear the more extreme moral messianists say their cure is to ban advertising. That’s not only naive, it’s dangerous, for without advertising journalists will starve and we will return to the age of the Medicis and their avissi: private information for the privileged few who can afford it. Paywalls are no paradise.

What’s really happening here — and this is a post and a book for another day — is a reflexive desire to control speech. I’ve been doing a lot of reading lately about the spread of printing in early-modern Europe and I am struck by how every attempt to control the press and outlaw forms of speech failed and backfired. At some point, we must have faith in our fellow citizens and shift our attention from playing Whac-a-Mole with the bad guys to instead finding, sharing, and supporting expertise, education, authority, intelligence, and quality so we can have a healthy, deliberative democracy in a marketplace of ideas. The alternatives are all worse.

* I leave you with a few ads I found in Facebook’s library that could work only via targeting and never on expensive mass media: the newspaper, TV, or radio. I searched on “march.”

When you eliminate targeting, you risk silencing these movements.

Opening photo credit and link: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/wagakkh5

The post In defense of targeting appeared first on BuzzMachine.

December 11, 2019

Enough testosterone

Full disclosure — I am everything I am about criticize: male, white, old, privileged, entitled, too-often angry.

I, for one, was appalled at Joe Biden’s attack on an Iowa voter who asked him critical questions about his son and his age. Biden, oddly unprepared for either challenge, was immediately angry, calling the voter, an elderly farmer, a “damn liar,” not giving a substantive response regarding his son, and justifying his place in the campaign solely on entitlement: “I’ve been around a long time and I know more than most people.” He challenged the man to pushups and an IQ test. The damn liar he should be challenging is the one in the White House.

I am embarrassed for my age, race, gender, and party. But not so the men around the table at Morning Joe — or Morning Joe (Biden), as I’ve taken to calling the show. They gave a rousing cheer to Biden’s performance, arguing this was just the kind of tough-guy spirit Biden should show to win, this being a fight rather than an election. Mika Brzezinski demurred, as is her wont: “I don’t like it [the video] but I think he’ll be a great president and he’ll win.” Thank goodness the BBC’s Katty Kay was at the table, as she dared criticize Biden for coming off like a fool. I spoke with women yesterday who said he came off as threatening, which is all too frighteningly familiar to them from men.

Please compare Biden’s performance when challenged by an elderly farmer with Nancy Pelosi’s when she was attacked by a right-wing Sinclair shill in reporter camouflage:

Pelosi responded with principle, reason, morality. Biden responded with anger, insult, bravado. What we need now in this nation is a leader who demonstrates the former, not the latter.

I supported Kamala Harris in this campaign for many reasons: her policies, her leadership, her experience, her prosecutorial zeal against Trump, her humanity — and, yes, her new and diverse perspective as a woman, a person of color, and the child of immigrants. Now that she is sadly out of the race, I’m asking myself whom I will support now. Yes, I will support the Democrat in the end. I will contribute, work for, and cheer whoever that is, and not just to work against Donald Trump — though that is reason enough.

But I am having difficulty with the field as it is, especially as it seems we will end up with a lily white debate stage the next time out (and the right is mocking Democrats for that). As I said earlier this week, I am angry that Democrats had a diverse field of candidates that was mansplained over by a parade of entitled white men. I am angry that media dismiss women and people of color and won’t question this in themselves. I am angry that Democrats are treating voters of color as pawns they can take for granted rather than listening to and giving voice to their issues and experiences.

I have a suggestion to improve coverage of the election and the campaign itself: I wish MSNBC would retire its old, white man of the evening, Chris Matthews, and replace him with a show featuring Jason Johnson, Tiffany Cross, Maria Hinojosa, Eddie Glaude Jr., Soledad O’Brien, Zerlina Maxwell, Maya Wiley, Karine Jean-Pierre, Joy Reid, Elie Mystal — so many wise people to choose from. Rather than having them on a round-robin guests or weekend hosts, give them a prime-time, daily show. Rather than treating their communities and issues as after-thoughts, put them at the center. Rather than taking voters of color for granted, listen to them. Give them the opportunity to challenge the candidates and the rest of media and to inform the rest of the electorate. The Democrats will count for victory on serving the needs of voters too long ignored, so don’t ignore them. Media will still reflexively if unconsciously exhibit their bias by constantly seeking out and trying to analyze the angry, white, male voter. Someone can do better.

Not that you should care, but here’s where I am.

If need be I will vote for, contribute to, and work for Biden if he is the nominee and not reluctantly as I know we will end up in agreement about most issues. But I worry that we will end up embarrassed by our own angry and increasingly doddering old man in office. I blame him for the whitening and aging of this field. He is not my first choice.

I respect Warren and think she will bring strong, fresh leadership with a moral vision to the office. But I worry that her policies will be be seen as radical by just enough voters to lose. I also think her attack on tech is cynical and dangerous. Don’t @ me for that.

Bernie? I agree with Hillary. Don’t @ me.

Mayor Pete is smart and impressively eloquent. But he is inexperienced and his education in communities of color has been too much on stage, for show.

That’s the top of the field.

Bloomberg? He’s an able technocrat. But his re-education in stop-and-frisk is also too much on stage, for show. And we do not need billionaires buying office.

Steyer, Yang, and Williamson are novelty candidates. Don’t @ me.

That leaves me with my best but long-shot hopes. I like Cory Booker and will donate to his campaign. The same for Julián Castro. And I include Amy Klobuchar in this list of the ones I’d like to see rise. These are candidates I wish were now front and center because they bring the perspectives we need. And maybe there’s still time. I won’t accept the pundits’ predictions, not until voters vote. Now I have some new hats and hoodies to buy.

The post Enough testosterone appeared first on BuzzMachine.

December 6, 2019

Thank you, Kamala Harris

I’m sorely disappointed to lose Kamala Harris from the race.

I am angry at the parade of white men; old, white men; and old, white, male billionaires who came marching into the campaign because they felt they had to mansplain the race; because they apparently believed they had to rescue us from wonderfully diverse, young, and fresh slate of candidates; and because: ego.

I am angry at journalists and pundits — my own field — for their bias in covering candidates of color and women, a bias they will not acknowledge and will not cover, even though it is a huge story in this campaign and the last one. I am angry at them for holding candidates of color and women to different expectations. I am angry at them for learning nothing from their mistakes in covering the 2016 campaign. I am angry at them for still believing it is their job to predict elections — which they do terribly — rather than inform the electorate. I am angry at them for publicizing the opinion polls that preempt democratic conversation.

I am angry at Democrats — my party — for thinking they can mobilize women and people of colors without actually listening to them, without representing them, without paying attention to the issues that matter in their lives.

I am grateful to Kamala Harris for her candidacy, for her stands on the issues, for her intelligence, generosity, representation, determination, inspiration, and prosecutorial zeal — and her humanity.

The post Thank you, Kamala Harris appeared first on BuzzMachine.

November 20, 2019

Harmful speech as the new porn

In 1968, Lyndon Johnson appointed a National Commission on Obscenity and Pornography to investigate the supposed sexual scourge corrupting America’s youth and culture. Two years later — with Richard Nixon now president — the commission delivered its report, finding no proof of pornography’s harm and recommending repeal of laws forbidding its sale to adults, following Denmark’s example. Nixon was apoplectic. He and both parties in the Senate rejected the recommendations. “So long as I am in the White House,” he vowed, “there will be no relaxation of the national effort to control and eliminate smut from our national life.” That didn’t turn out to be terribly long.

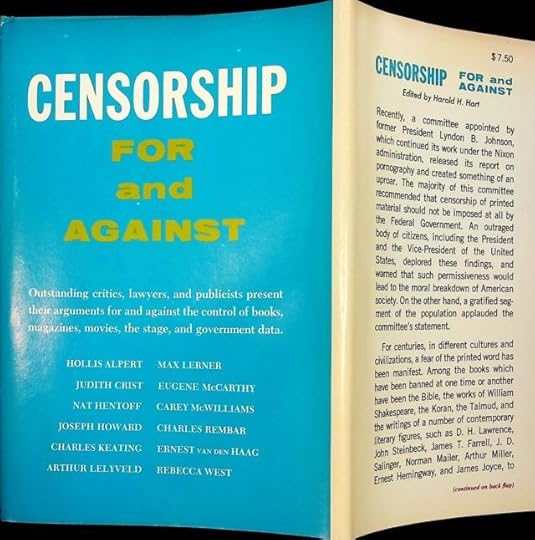

A week ago, as part of my research on the Gutenberg age, I made a pilgrimage to Oak Knoll Books in New Castle, a hidden delight that offers thousands of used books on books. On the shelves, I found the 1970 title, Censorship: For and Against, which brought together a dozen critics and lawyers to react to the fuss about the so-called smut commission. I’ve been devouring it.

For the parallels between the fight against harmful and hateful speech online today and the crusade against sexual speech 50 years ago are stunning: the paternalistic belief that the powerless masses (but never the powerful) are vulnerable to corruption and evil with mere exposure to content; the presumption of harm without evidence and data; cries calling for government to stamp out the threat; confusion about the definitions of what’s to be forbidden; arguments about who should be responsible; the belief that by censoring content other worries can also be erased.

Moral panic

One of the essays comes from Charles Keating, Jr., a conservative whom Nixon added to the body after having created a vacancy by dispatching another commissioner to be ambassador to India. Keating was founder of Citizens for Decent Literature and a frequent filer of amicus curiae briefs to the Supreme Court in the Ginzberg, Mishkin, and Fanny Hill obscenity cases. Later, Keating was at the center of the 1989 savings and loan scandal — a foretelling of the 2008 financial crisis — which landed him in prison. Funny how our supposed moral guardians — Nixon or Keating, Pence or Graham — end up disgracing themselves; but I digress.

Keating blames rising venereal disease, illegitimacy, and divorce on “a promiscuous attitude toward sex” fueled by “the deluge of pornography which screams at young people today.” He escalates: “At a time when the spread of pornography has reached epidemic proportions in our country and when the moral fiber of our nation seems to be rapidly unravelling, the desperate need is for enlightened and intelligent control of the poisons which threaten us.” He has found the cause of all our ills: a textbook demonstration of moral panic.

There are clear differences between his crusade and those attacking online behavior today. The boogeyman then was Hollywood but also back-alley pornographers; today, it is big, American tech companies and Russian trolls. The source of corruption then was a limited number of producers; today, it is perceived to be some vast number of anonymous, malign conspirators and commenters online. The fear then was the corruption of the masses; the fear now is microtargeting drilling directly into the heads of a strategic few. The arena then was moral; now it is more political. But there are clear similarities, too: Both are wars over speech.

“Who determines who is to speak and write, since not everyone can speak?” asks former presidential peace candidate Gene McCarthy in his chapter of the book. But now, everyone can speak.

McCarthy next asks: “Who selects what is to be recorded or transmitted to others, since not everything can be recorded?” But now, everything can be recorded and transmitted. That is the new fear: too much speech.

A defense of speech

Many of the book’s essayists defend freedom of expression over freedom from obscenity. Says Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld (father of Joseph, who would become executive editor of The New York Times): “Freedom of expression, if it is to be meaningful at all, must include freedom for ‘that which we loathe,’ for it is obvious that it is no great virtue and presents no great difficulty for one to accord freedom to what we approve or to that to which we are indifferent.” I hear too few voices today defending speech of which they disapprove.

Lelyveld then addresses directly the great bone of contention of today: truth. “That which I hold to be true has no protection if I permit that which I hold to be false to be suppressed — for you may with equal logic turn about tomorrow and label my truth as falsehood. The same test applies to what I consider lovely or unlovely, moral or immoral, edifying or unedifying.” I am stupefied at the number of smart people I know who contend that truth should be the standard to which social-media platforms are held. Truths exist in their contexts, not relative but neither simple nor absolute. Truth is hard.

“We often hear freedom recommended on the theory that if all expression is permitted, the truth is bound to win. I disagree,” writes another contributor, Charles Rembar, an attorney who championed the cases of Lady Chatterley, Tropic of Cancer, and Fanny Hill. “In the short term, falsehood seems to do about as well. Even for longer periods, there can be no assurance of truth’s victory; but over the long term, the likelihood is high. And certainly truth’s chances are better with freedom than with repression.”

A problem of definition

So what is to be banned? That is a core problem today. The UK’s — in my view, potentially harmful — Online Harms White Paper cops out from defining what is harmful but still proposes holding online companies liable for harm. Worse, its plan is to order companies to take down legal but harmful content — which, of course, makes that content de facto illegal. Similarly, Germany’s NetzDG hate speech law tells the platforms they must take down anything that is “manifestly unlawful” within 24 hours, meaning a company — not a court — is required to decide what is unlawful and whether it’s manifestly so. It’s bad law that is being copied so far by 13 countries, including by authoritarian regimes.

As an American and a staunch defender of the First Amendment, I’m allergic to the notion of forbidden speech. But if government is going to forbid it, it damned well better clearly define what is forbidden or else the penumbra of prohibition will cast a shadow and chill on much more speech.

In the porn battle, there was similar and endless debate about the fuzzy definitions of obscenity. Author Max Lerner writes of the courts: “The lines they draw and the tests they use keep shifting, as indeed they must: What is ‘prurient’ or ‘patently offensive’ enough to offend the ‘ordinary reader’ and the going moral code? What will hurt or not hurt children and innocents? What is the offending passage like in its context…?” Even Keating questions the standard that emerged from Fanny Hill: to be censored, content must be utterly without redeeming social importance. “There are those who will say that if you can burn a book and warm your hands from the fire,” Keating says, “the book as some redeeming social value.” Keating also argues that pornography “is actually a form of prostitution because it advertises ‘sex for sale,’ offers pleasure for a price” — and since prostitution is illegal, so must pornography be. Justice Potter Stewart’s famed standard for obscenity— “I’ll know it when I see it” — is the worst standard of all, for just like the Harms White Paper and NetzDG it requires distributors and citizens to guess. It is chilling.

Who is being protected?

“Literary censorship is an elitist notion: obscenity is something from which the masses should be shielded. We never hear a prosecutor, or a condemning judge (and rarely a commentator) declare his moral fiber has been injured by the book in question. It is always someone else’s moral fiber for which anxiety is felt. It is ‘they’ who will be damaged. In the seventeenth century, ‘they’ began to read; literacy was no longer confined to the clergy and the upper classes. And it is in the seventeenth century when we first begin to hear about censorship for obscenity.” So writes Rembar.

In the twentieth century ‘they’ began to write and communicate as never before in history — nearly all of ‘them.’ That has frightened those who had held the power to speak and broadcast. Underrepresented voices are now represented and the powerful want to silence them to protect their power. It is in the twenty-first century that we hear about control of harmful speech and hate.

“I am opposed to censorship in all forms, without any exception,” writes Carey McWilliams, who was then editor of The Nation, arguing that censorship is a form of social control. “I do not like the idea of some people trying to protect the minds and morals of other people. In practice, this means that a majority seeks to impose its standards on a minority; hence, an element of coercion is inherent in the idea of censorship.” It is also inherent in the idea of civility, an imposition of standards, expectations, and behavior from top down.

McWilliams then quotes Donald Thompson on literary censorship in England: “Political censorship is necessarily based on fear of what will happen if those whose work is censored get their way…. The nature of political censorship at any given time depends on the censor’s answer to the simple question, ‘What are you afraid of?’” Or whom are you afraid of? Rembar’s “they”? McWilliams concludes:

But in a time of turmoil and rapid social change, fears of this sort can become fused with other kinds of fears; and their censorship becomes merely one aspect of a general repression. The extent of the demands for censorship may be taken, therefore, as an indicator of the social health of a society. It is not the presence — nor the prevalence — of obscene materials that needs to be feared so much as it is the growing demand for censorship or repression. Censorship — not obscenity nor pornography — is the real problem.

Lerner puts this another way, examining a shift in the “norm-setting classes” over time. In the past, the aristocracy set norms for dress, taste, and morals. Then the middle classes did. Now, I will argue, the internet blows that apart as many communities are in a position to compete to set or protect norms.

Freedom from

Rembar notes that “reading a book is a private affair” (as it has been since silent reading replaced reading aloud starting in about the seventh century A.D.). He addresses the Constitution’s implicit — not explicit — right to be let alone, the basis of much precedent in privacy. “Privacy in law means various things,” he writes; “and one of the things it means is protection from intrusion.” He argues that in advertising, open performance, and public-address systems, “these may validly be regulated” to prevent porn from being thrust upon the unsuspecting and unwilling. It is an extension of broadcast regulation.

And that is something we grapple with still: What is shown to us, whether we want it shown to us, and how it gets there: by way of algorithm or editor or bot. What is our right not to see?

Who decides?

Max Lerner is sympathetic with courts having to judge obscenity. “I view the Court’s efforts not so much with approval or disapproval as with compassion. Its effort is herculean and almost hopeless, for given the revolution of erotic freedom, it is like trying to push back the onrushing flood.” The courts took on the task of defining obscenity though, as Lerner points out above, they never really did draw a clear line.

The Twenty-Six Words that Created the Internet is Jeff Kosseff’s definitive history and analysis of the current fight over Section 230, the fight over who will be held responsible to forbid speech. In it, Kosseff explains how debate over intermediary liability, as this issue is called, stretches back to a 1950s court fight, Smith v. California, about whether an L.A. bookseller should have been responsible for knowing the content of every volume on his shelves.

Today politicians are shying away from deciding what is hateful and harmful, and these questions aren’t even getting to the courts because the responsibility for deciding what to ban is being put squarely on the technology platforms. Because: scale. Also because: tech companies are being portrayed as the boogeymen — indeed, the pornographers — of the age; they’re being blamed for what people do on their platforms and they’re expected to just fix it, damnit. Of course, it’s even more absurd to expect Facebook or Twitter or Youtube to know and act on every word or image on their services than it was to expect bookseller Eleazer Smith to know the naughty bits in every book on his shelves. Nonetheless, the platforms are being blamed for what users do on those platforms. Section 230 was designed to address that by shielding companies — including, by the way, news publishers — from liability for what others do in their space while also giving them the freedom (but not the requirement) to police what people put there. The idea was to encourage the convening of productive conversation for the good of democracy. But now the right and the left are both attacking 230 and with it the internet and with that freedom of expression. One bite has been taken out of 230 thanks to — what else? — sex, and many are trying to dilute it further or just kill it.

Today, the courts are being deprived of the opportunity to decide cases about hateful and harmful speech because platforms are making decisions about content takedowns first under their community standards and only rarely over matters of legality. This is one reason why a member of the Transatlantic High-Level Working Group on Content Moderation and Freedom of Expression — of which I am also a member — proposes the creation of national internet courts, so that these matters can be adjudicated in public, with due process. In matters of obscenity, our legal norms were negotiated in the courts; matters of hateful and harmful speech are by and large bypassing the courts and thus the public loses an opportunity to negotiate them.

What harm, exactly?

The presidential commission looked at extensive research and found little evidence of harm:

Extensive empirical investigation, both by the Commission and by others, provides no evidence that exposure to or use of explicit sexual materials plays a significant role in the causation of social or individual harms such as crime, delinquency, sexual or nonsexual deviancy or severe emotional disturbances…. Studies show that a number of factors, such as disorganized family relationships and unfavorable peer influences, are intimately related to harmful sexual behavior or adverse character development. Exposure to sexually explicit materials, however, cannot be counted as among those determinative factors. Despite the existence of widespread legal prohibitions upon the dissemination of such materials, exposure to them appears to be a usual and harmless part of the process of growing up in our society and a frequent and nondamaging occurrence among adults.

Over this, Keating and Nixon went ballistic. Said Nixon: “The commission contends that the proliferation of filthy books and plays has no lasting harmful effect on a man’s character. If that were true, it must also he true that great books, great paintings and great plays have no ennobling effect on a man’s conduct. Centuries of civilization and 10 minutes of common sense tell us otherwise.” To hell with evidence, says Nixon; I know better.

Keating, likewise, trusts his gut: “That obscenity corrupts lies within the common sense, the reason, and the logic of every man. If man is affected by his environment, by circumstances of his life, by reading, by instruction, by anything, he is certainly affected by pornography.” In the book, Keating ally Joseph Howard, a priest and a leader of the National Office of Decent Literature, doesn’t need facts when he has J. Edgar Hoover to quote: “Police officials,” said the FBI director, “unequivocally state that lewd and obscene material plays a motivating role in sexual violence…. Such filth in the hands of young people and curious adolescents does untold damage and leads to disastrous consequences.” Damn the data; full speed ahead.

Today, we see a similar habit of skipping over research, data, and evidence to get right to condemnation. We do not actually know the full impact of Facebook, Cambridge Analytica, Twitter, and social media on the election. As the commission says of the causes of deviancy, there must be other factors that got us Trump. Legislation and regulation are being proposed based on a candy bowl of tropes — the filter bubble, the echo chamber, hate speech, digital harms — without sufficient research to back up the claims. Thank goodness we are starting to see research into these questions; see, for example, Axel Bruns’ dismantling of the filter bubble.

Here I will lay some blame at the feet of the platforms, for we cannot have adequate research to test these questions until we have data from the platforms that answer questions about what people see and how they behave.

How bad is the bad of the internet? That depends on evidence of impact. It also depends on relative judgment. Rembar’s view of what he calls the “seductio ad absurdum” of sex and titillation in media: “There is an acne on our culture.” It is “an unattractive aspect of our cultural adolescence.” And: “acne is hardly fatal.”

Is today’s online yelling and shouting, insulting and lying by some people— just some, remember — an “all-pervasive poison” that imperils the nation, as Keating viewed porn? Or is it an unsightly blemish we’ll likely grow out of, as Rembar might advise?

I am not saying we leave the zits alone. I have argued again and again that Facebook and Twitter should set their own north stars and collaborate with users, the public, and government on covenants they offer to which they will be held accountable. I think standards of behavior should apply to any user, including politicians and presidents and advertisers. I strongly argue that platforms should take down threatening and harassing behavior against their users. I embrace Section 230 precisely because it gives the platforms as well as publishers the freedom to decide and enforce their own limits. But I also believe that we must respect the public and not patronize and infantilize them by believing we should protect them from themselves, saving their souls.

Permission is not endorsement

To be clear, the anti-censorship authors in the book and other allies of the commission (including The New York Times editorial page) are not defending pornography. “To affirm freedom is not to applaud that which is done under its sign,” Lelyveld writes. van den Haag, the psychoanalyst, abstracts pornography to a disturbing end: “Pornography reduces the world to orifices and organs, human action to their combinations. Sex rages in an empty world; people use each other as its anonymous bearers and vessels, bereaved of individual love and hate, thought and feeling reduced to bare sensations of pain and pleasure existing only in and for incessant copulations, without apprehension, conflict, or relationship — without human bonds.”

Likewise, by opposing censorship conducted or imposed by government, I am not defending hateful or noxious speech. When I oppose reflexive regulation, I am not defending its apparent objects — the tech companies — but instead I defend the internet and with it the free expression it enables. The question is not whether I like the vile, lying, bigoted rantings of the likes of a Donald Trump or Donald Trump Jr. or a video faked to make Nancy Pelosi look drunk — of course, I do not — but whether by banning them a precedent is set that next will affect your or me.

Hollis Alpert, film critic then for Saturday Review, warns in his essay: “The unscrupulous politician can take advantage of the emotional, hysterical, and neurotic attitudes toward pornography to incite the multitude towards approval of repressive measures that go far beyond the control of the printed word and the photographed image.”

Of freedom of expression

Richard Nixon was quite willing to sacrifice freedom of expression to obliterate smut: “Pornography can corrupt a society and a civilization,” he wrote in his response to the commission. “The pollution of our culture, the pollution of our civilization with smut and filth is as serious a situation for the American people as the pollution of our once pure air and water…. I am well aware of the importance of protecting freedom of expression. But pornography is to freedom of expression what anarchy is to liberty; as free men willingly restrain a measure of their freedom to prevent anarchy, so must we draw the line against pornography to protect freedom of expression.”

Where will lines be drawn on online speech? Against what? For what reasons? Out of what evidence? At what cost? These questions are too rarely being asked, yet answers are being offering in legislation that is having a deleterious effect on freedom of expression.

Society survived and figured out how to grapple with porn, all in all, just as it survived and figured out how to adapt to printing, the telegraph, the dime novel, the comic book, and other supposed scourges on public morality — once society learned each time to trust itself. Censorship inevitably springs from a lack of trust in our fellow citizens.

Gene McCarthy writes:

There is nothing in the historical record to show that censorship of religious or political ideas has had any lasting effect. Christianity flourished despite the efforts of the Roman Emperors to suppress it. Heresies and new religions developed and flourished in the Christian era at the height of religious suppression. The theories of democracy did not die out even though kings opposed them. And the efforts in recent times to suppress the Communist ideology and to keep it from people has not had a measurable or determinable success. Insofar as the record goes, the indications are that heresy and political ideas either flourished or died because of their own strength or weakness even though books were suppressed or burned and authors imprisoned, exiled, or executed.

And he concludes: “The real basis of freedom of speech and of expression is not, however, the right of a person to say what he thinks or what he wishes to say but the right and need of all persons to learn the truth. The only practical approach to this end is freedom of expression.”

Epilogue

An amusing sidebar to this tale: When the commission released its report, an enterprising publisher printed and sold an illustrated version of it, adding examples of what was being debated therein: that is, 546 dirty pictures. William Hamling, the publisher, and Earl Kemp, the editor, were arrested on charges of pandering to prurient interests for mailing ads for the illustrated report, and sentenced to four and three years in prison, respectively. According to Robert Brenner’s Huffpost account, someone received the mailing, took it to Keating, who took it to Nixon, who told Attorney General John Mitchell to nab them. (And some wonder why we worry about Trump attacking the press as the enemy of the people and having a willing handmaid in William Barr, who will do his any bidding!) The Supreme Court upheld their convictions but the men served only 90 days, though the owner was forced to sell his publishing house and was not permitted to write about the case: censorship upon censorship.

Two months later, Richard Nixon left office.

The post Harmful speech as the new porn appeared first on BuzzMachine.

November 3, 2019

Polls subvert democracy: Media’s willful erasure of Kamala Harris’ campaign

It is journalistic heresy that I abandon the myth of objectivity and publicly support candidates. But the advantage of heresies is that they open one up to new perspectives. By seeing my profession and industry from the viewpoint of an interested voter, I get a new window on the failures of news media.

People know that I support Kamala Harris for president and so these days they’re asking me whether I’m still for her because, you know, the polls. Inside, I scream and deliver a searing lecture on the tyranny of the public-opinion industry, on the true heresy of journalistic prognostication, on the death of the mass, on the devaluing of the franchise of so many unheard voices in America. Outside, I just smile and say “you’re damned right, I do,” and wait to get to my desk pour out that screed here.

The coverage of Kamala Harris’ campaign is a classic case of media’s self-fulfilling prognostication. Step-by-step:

Harris’ campaign opens with a big rally and reporters say she could be bigger than Obama! Thus media set expectations the candidate did not set.

A parade of white men with established recognition (read: power) enter what had been a wonderfully diverse field, splintering the vote.

Harris’ poll numbers decline. Media declare disappointment against media’s overblown expectations.

Media give less attention to Harris’ campaign because, you know, the poll numbers.

Harris’ poll numbers fall more because media give her less attention and voters hear less of her, less from her.

The candidate finds it harder to raise money to buy the attention media isn’t giving her so the polls decline and media give her less attention. Candidates with more money get more attention. Pundits even use money as a metric for democracy. (And meanwhile, candidates can’t use the the inexpensive and efficient mechanism of Twitter advertising because media cowed the company into closing that door.) Harris closes New Hampshire offices. Pundits say they predicted this, taking no responsibility for perhaps causing it.

Return to 4. Loop.

Pundits mainsplain what went wrong with her campaign.

Not a single citizen has voted yet. Yes, campaigns come and go. That’s politics. But here I see this cycle affect the campaign of an African-American, a woman, a child of immigrants, someone 15–23 years younger than the three best-known leaders in the field, and someone who can take on our criminal president and his criminal henchmen. We need her perspective in this race and her intelligence in office. I want my chance to vote for her. But media gradually ignore her, erase her.

And then Harris delivers a speech like this one, last week in Iowa. If you want to know why I support her, all you have to do is watch it.

Afterwards, people notice. Some take to Twitter to suggest she should not be counted out. Some of them are African-American commentators who are also saying we should not count them out.

Wow!

I keep thinking about how Kamala was the first to endorse Obama in 2007 and was on the ground knocking doors before anyone thought it was even possible to have a President Obama! I wonder what it's like to be on the ground for this full circle moment. Reporters? https://t.co/MJvYASe2Ha

— Zerlina Maxwell (@ZerlinaMaxwell) October 30, 2019

Folks shouldn’t count @KamalaHarris out yet. She gave a powerful speech in Iowa punctuated with being a lawyer who has only had one client – “the people” and a “middle class tax cut” https://t.co/fQD0AHQhi5

— Maya Wiley (@mayawiley) November 2, 2019

And now the Guardian says she could salvage her campaign. It’s not in the trash, people. It’s still happening.

At the root of this process of disenfranchisement is, paradoxically, the poll. Theoretically, the opinion poll was intended to capture public opinion but in fact does the opposite: cut it off. I often quote snippets of this paragraph from the late Columbia professor James Carey. Here it is in full, my emphases added:

“This notion of a public, a conversational public, has been pretty much evacuated in our time. Public life started to evaporate with the emergence of the public opinion industry and the apparatus of polling. Polling (the word, interestingly enough, derived from the old synonym for voting) was an attempt to simulate public opinion in order to prevent an authentic public opinion from forming. With the rise of the polling industry, intellectual work on the public went into eclipse. In political theory, the public was replaced by the interest group as the key political actor. But interest groups, by definition, operate in the private sector, behind the scenes, and their relationship to public life is essentially propagandistic and manipulative. In interest-group theory the public ceases to have a real existence. It fades into a statistical abstract: an audience whose opinions count only insofar as individuals refract the pressure of mass publicity. In short, while the word public continues in our language as an ancient memory and a pious hope, the public as a feature and factor of real politics disappears.”

There is not one public; that is the myth of the mass, propagated by mass media. There are many publics — many communities — that together negotiate a definition of a society. That is what elections — not polls — are intended to enable. That is what a representative democracy is meant to implement. That is what journalism should support.

Polls are the news industry’s tool to dump us all into binary buckets: red or blue; black or white; 99% or 1%; urban or rural; pro or anti this or that; religious (read: evangelical extremist) or not; Trumpist or not; for or against impeachment. Polls erase nuance. They take away choices from voters before they get to the real polls, the voting booth. They silence voices.

That is precisely the opposite of what journalism should be doing. Journalism should be listening to voices not heard, not as gatekeeper but as a curator of the public conversation. Facebook and Twitter enable voices ignored by mass media to be heard at last and that is one reason (the other is money) why media so hate these companies.

A little over three years ago, in the midst of the general election, I wrote a similar screed about the coverage of Hillary Clinton. The sins were slightly different — but her email, false balance, the aspiration to be savvy — but my opportunity was the same: to see journalism’s faults from the perspective of the voter, not the editor. My complaints there all stand. We haven’t learned a thing.

And I’m not even addressing the myriad faults in coverage of Donald Trump: letting him set the agenda (no, the big story is not quid pro quo, it is his malfeasance in office); playing stenographer to his tweets; refusing to call a lie a lie; refusing to call racism racism; being distracted by his squirrels. That will all come back to haunt us in the general election. How the nation fares in that election depends greatly on how we are allowed by media to negotiate the primaries.

Return to 2. Loop.

The post Polls subvert democracy: Media’s willful erasure of Kamala Harris’ campaign appeared first on BuzzMachine.

October 31, 2019

Unpopular decisions

I will please no one with this post about Facebook’s and Twitter’s decisions regarding political advertising and news.

The popular opinion would be to praise Twitter for banning political and issue ads and condemn Facebook for not fact-checking political ads. I’ll do neither. I disagree with both companies, for I think they each found diametrically opposed ways to take too little responsibility for what occurs on their platforms.

First Twitter. A week ago, I disagreed on Twitter with someone who said Facebook should ban political ads. Then a few Twitter folks asked me — on Twitter, of course — why I said that. I explained my perspective, but clearly was not persuasive.

My view: if we cut off inexpensive and efficiently targeted political — and, as it turns out, issue — advertising, then we likely will be left with big-money campaigns still using mass media (that is, TV) just as we had hoped to leave that corrupt era behind. I fear that such a move will benefit incumbents — who have money, recognition, and power — at the cost of insurgents. Without advertising on social media would we have the next @AOC? Yes, I know that Ocasio-Cortez herself is endorsing Twitter’s decision but as The Intercept’s Ryan Grim points out in a thoughtful thread, even she spends money on social-media advertising. If new movements are cut off from using social advertising, Grim argues, it could be “a huge blow to progressives, and a boon to big-money candidates.”

I also argue that at some point, we must trust the public, the electorate, ourselves. If we cannot, then we are surrendering democracy. We must put our faith in the public conversation. If you want to improve it, wonderful: Promote reliable, quality news (as Facebook is doing with its news tab — more on that below); support education by new means; donate questionably gotten gains from political advertising to campaigns to fight voter suppression; support (as Twitter hopes to do) expertise over mere blather. Will we ever, as my German friends on Twitter recommend, ban political advertising in the U.S.? NFW. Because First Amendment.

Now, Facebook. [Disclosure: Facebook has funded projects at my school. I receive no compensation from any platform.] Mark Zuckerberg has said definitively that Facebook will not fact-check political ads. That, I agree with, but not for the reason you might assume. Truth is the wrong standard. If truth were so easy then we wouldn’t need countless journalists to find it. No one will trust Facebook to decide truth. But I do think that Facebook should set and uphold standards of dignity, decency, and responsibility in the public conversation and hold everyone — politicians and citizens, users and advertisers — accountable. If Facebook wants to leave up noxious speech by pols so we can see and judge it, OK, but it should add a disclaimer disapproving of the behavior. (Twitter has said that will be its policy, but I’ve yet to see it in action.) If a politician uses a racial slur in political ad — say, calling Mexicans rapists and murderers — Facebook must condemn that behavior, or its Oversight Board likely will. If Facebook accepts such words without comment or caveat, then it must be presumed to condone them. I’d find that unacceptable.

In the end, both Facebook and Twitter — and let’s throw Google and all the other platforms in now — refuse to make judgments. They cannot get away with that anymore. They are hosts to conversation and communities. They have an impact on that conversation and thus on democracies and nations. They are private companies. They are going to have to make judgments according to public principles, no matter how allergic they are to that idea.

Now to Facebook and its news judgments. Last week, the company announced details of its new news tab, Zuckerberg joining with Murdoch lieutenant and News Corp. chief executive Robert Thomson, a caustic critic of Facebook, Google, and ultimately the internet. I have worried about the precedent of a platform paying for content, which is one reason why I have supported Google’s decision not to pay European publishers’ extortion under the EU’s new Copyright Directive. But I am also happy to see a technology company stepping up to support quality news and so I’m loathe to look the gift horse in the mouth. In the end, I’m glad Facebook is making its news tab and, even if with its checkbook, making peace with publishers.

But then Facebook decided to include Breitbart in its corral of trusted, quality publishers in the new news tab. Now I’m having an allergic reaction. The project Facebook supported at my school aggregates signals of quality in news. By my standards, Breitbart is far from quality. (This is outdated — from Steve Bannon’s time there — but here’s a good roundup from Rolling Stone of awful things Breitbart has published. I’d say 10 strikes and you’re out.) I understand Facebook’s desire — expressed by Zuckerberg in the company’s news tab announcement and again by news VP Campbell Brown here — to include a range of perspectives. The real problem is that we — we in media, in journalism, in Silicon Valley — have not grappled with the political asymmetry in both news media and disinformation. The real solution, I have argued, lies in investing more in responsible, credible, fact-based, journalistic conservative media to compete with the likes of Fox News — and Breitbart. Now, if you want to present some number of conservative sources, it doesn’t take long before you find yourself staring at Breitbart and worse.

Paradoxically, in their effort to find the mythic middle, the platforms are falling into the journalistic trap of objectivity — or as the right puts it these days, neutrality. That sounds like safe space, neither this nor that. But as Jay Rosen has lectured journalists for the better part of a decade, the view from nowhere is a myth — in my words, false comfort and a lie. It doesn’t exist. There is no safe escape from these hard problems. There are no popular decisions.

The platforms — all of them, whether they want to be lumped together or not — are facing tremendous political pressure as the right and left are forming a pincer movement exploiting moral panic to go after them as a class, jeopardizing freedom of expression on the internet for all of us. That is why I defend the platforms, to defend the internet; and why I also push them to do better, to improve the internet. I understand their panic in response. But hiding from judgment is not the answer. To the contrary, every technology company must make a bold and brave decision about where it stands, about the covenant it is offering the public, about the principles of dignity and decency it will defend.

Killing political and issue advertising is no solution. Refusing to hold political and issue advertising to account is no solution. Refusing to judge journalism is no solution. Politicians — and especially media — forcing technology companies into these corners is a problem.

What I fear most is the unintended consequences of these too-easy answers. I’ll end by recommending a just-released paper from economists warning about the cost of the precautionary principle: that when out of precaution we forbid something (whether political advertising or, in the case of this paper, nuclear power) we risk a consequence that could be worse. It sounds so satisfying to tell technology companies they should butt out of politics, but then we take the tools they provide away from the very people who have not been heard by mainstream media and who are finally empowered by the net, and we leave that power in the hands of the legacy regimes that have so screwed up the world. Be careful what you wish for and retweet and like.

The post Unpopular decisions appeared first on BuzzMachine.

September 27, 2019

For a National Journalism Jury

For the last year, I’ve been engaged in a project to aggregate signals of quality in news so platforms and advertisers can recognize and give greater promotion and support to good journalism over crap.

I’ve seen that we’re missing a key — the key — signal of quality in journalism. We don’t judge journalism ourselves.

Oh, we give each other lots and lots of awards. But we have no systematized way for the public we serve to question or complain about our work and no way to judge journalistic failure while providing guidance in matters of journalistic quality and ethics.

Facebook is establishing an Oversight Board. Shouldn’t journalism have something similar? Shouldn’t we have a national ombuds organization, especially at a time when the newsroom ombudsperson is all but extinct? The Association of News Ombudsmen lists four — four! — members from consumer news organizations in the U.S. I’m delighted that CJR doubled that number, hiring four independent public editors, but they cover only as many news organizations — The Times, The Post, CNN, and MSNBC; what of the rest?

I would like to see a structure that would enable anyone — citizen, journalist, subject — to file a question or complaint to this organization — call it a board, a jury, a court, a council, a something — that would select cases to consider.

Who would be on that board? I doubt that working journalists would be willing to judge colleagues and competitors, lest they be judged. So I’d start with journalism professors — fully aware that’s a self-serving suggestion (I would not serve, as I’d be a runaway juror) and that we the ivy-covered can be accused of being either revolutionaries or sticks-in-the-mud; it’s a place to start. I would include journalism grandees who’ve retired or branched out to other callings but bring experience, authority, and credibility with journalists. I would add representatives of civil society, assuring diversity of community, background, and perspective. Will these people have biases? Of course, they will; judge their judgment accordingly.

How would cases be taken up? Anyone could file a case. Yes, some will try to game the system: ten thousand complaints against a given outlet; volume is meaningless. The jury must have full freedom and authority to grant certiorari to specific cases. Time would be limited, so they would pick cases based on whether they are particularly important, representative, instructive, or new.

What would jurors produce? I would want to see thoughtful debate and consideration of difficult questions about journalistic quality yielding constructive and useful criticism of present practice. There is no better model than Margaret Sullivan’s tenure as public editor of The New York Times.

Isn’t this the wrong time to do this, just as the president is attacking the press as the enemy of the people? It’s precisely the right time to do this, to show how we uphold standards, are not afraid of legitimate criticism, and learn from our mistakes. There is no better way to begin to build trust than to address our own faults with honesty and openness.

How would this be supported? Such an effort cannot be ad hoc and volunteer. Jurors’ time needs to be respected and compensated. There would need to be at least one administrative person to handle incoming cases and output of judgments. Calling all philanthropists.

Do journalists need to pay attention to the judgments? No. This is not a press council like the ones the UK keeps trying — and failing — to establish. It brings no obligation to news organizations. It is an independent organization itself with a responsibility to debate key issues in our rapidly changing field.

Would it enforce a given set of standards? I don’t think it should. There are as many journalistic codes of conduct and ethics as there are journalists and I think the jurors should feel free to call on any of them — or tread new territory, as demanded by the cases. I’m not sure that legacy standards will always be relevant as new circumstances evolve. It is also important to judge publications in their own context, against their own promises and standards. I have argued that news organizations (and internet platforms) should offer covenants to their users and the public; judge them against that.

Whom does it serve, journalists or the public? I think it must serve the interests of the public journalism serves. But I recognize that very few members of the public would read or necessarily give a damn about its opinions. The audience for the jury’s work would be primarily journalists as well as journalism students and teachers.

Will it convince our haters to love us? Of course not.

Isn’t Twitter the new ombudsperson? When The New York Times eliminated its public editor position, it said that social media would pick up the slack. “But today,” wrote then-publisher Arthur Sulzberger, “our followers on social media and our readers across the internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog, more vigilant and forceful than one person could ever be.” That should be the case. But in reality, when The Times is criticized, reporters there tend to unleash a barrage of defensiveness rather than dialog.

Now I don’t want to pick on The Times. I subscribe to and honor it as a critical institution; I disagree with those who react to Times’ missteps with public vows to cancel subscriptions. Indeed, I hope that this jury can act as a pressure-relief valve that leads to dialog over defensiveness and debate instead of our reflexive cancel culture.

Having said that, unfortunately The Times does give us a wealth of recent examples of the kinds of questions this jury could take up and debate. The latest is the paper’s decision to reveal details about the Trump-Ukraine whistleblower, potentially endangering the person, and the justification by editor Dean Baquet. I want to see a debate about the ethics and implications of such a decision and I believe we need a forum where that can happen. That case is why I decided to post this idea now.

This is not easy. It’s not simple. It’s not small. It might be a terrible idea. So make your suggestions, please. In the end, I believe we need to address trust in news not with media literacy that tries to teach the public how to use and trust what they don’t use and trust now; not with the codification of our processes and procedures; not with closing in around the few who love and pay for admission behind our walls; not by hectoring our legitimate critics with defensive whining; not with false balance in an asymmetrical media ecosystem; not with blaming others for our faults. No, I believe we need a means to listen to warranted criticism and gain value from it by grappling with our shortcoming so we can learn and improve. We don’t have that now. How could we build it?

Disclosure: NewsQA, the aggregator of news quality signals I helped start, has been funded in its first phase by Facebook. It is independent and will provide its data for free to all major platforms, ad networks, ad agencies, and advertisers as well as researchers.

The post For a National Journalism Jury appeared first on BuzzMachine.

September 19, 2019

‘Decomputerize?’ Over My Dead Laptop!

This week, I wrote a dystopia of the dystopians, an extrapolation of current wishes among the anti-tech among us about dangers and regulation of technology, data, and the net. I tried to be detailed and in that I feared I may have gone too far. But now The Guardian shows me I wasn’t nearly dystopian enough, for a columnist there has beaten me to hell.

This week, I wrote a dystopia of the dystopians, an extrapolation of current wishes among the anti-tech among us about dangers and regulation of technology, data, and the net. I tried to be detailed and in that I feared I may have gone too far. But now The Guardian shows me I wasn’t nearly dystopian enough, for a columnist there has beaten me to hell.

“To decarbonize we must decomputerize: why we need a Luddite revolution,” declares the headline over Ben Tarnoff’s screed.

He essentially makes the argument that computers use a lot of energy; consumption of energy is killing the planet; ergo we should destroy the computers to save the planet.

But that is a smokescreen for his true argument against his real devil, data. And that frightens me. For to argue against data overall — its creation, its gathering, its analysis, its use — is to argue against information and knowledge. Tarnoff isn’t just trying to reverse the Digital Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. He’s trying to roll back the fucking Enlightenment.

That he is doing this in the pages of The Guardian, a paper I admire and love (and have worked and written for) saddens me doubly, for this is a news organization that once explored the opportunities — and risks — of technology with open eyes and curiosity in its reporting and with daring in its own strategy. Now its writers cry doom at every turn:

Digitization is a climate disaster: if corporations and governments succeed in making vastly more of our world into data, there will be less of a world left for us to live in.

It’s all digitization’s fault. That is textbook moral panic. To call on Ashley Crossman’s definition: “A moral panic is a widespread fear, most often an irrational one, that someone or something is a threat to the values, safety, and interests of a community or society at large. Typically, a moral panic is perpetuated by news media, fuelled by politicians, and often results in the passage of new laws or policies that target the source of the panic. In this way, moral panic can foster increased social control.”

The Bogeyman, in Tarnoff’s nightmare, is machine learning, for it creates an endless hunger for data to learn from. He acknowledges that computer scientists are working to run more of their machines off renewable energy rather than fossil fuel — see today’s announcement by Jeff Bezos. But again, computers consuming electricity isn’t Tarnoff’s real target.

But it’s clear that confronting the climate crisis will require something more radical than just making data greener. That’s why we should put another tactic on the table: making less data. We should reject the assumption that our built environment must become one big computer. We should erect barriers against the spread of “smartness” into all of the spaces of our lives.

To decarbonize, we need to decomputerize.

This proposal will no doubt be met with charges of Luddism. Good: Luddism is a label to embrace. The Luddites were heroic figures and acute technological thinkers.

Tarnoff admires the Luddites because they didn’t care about improvement in the future but fought to hold off that future because of their present complaints. They smashed looms. He wants to “destroy machinery hurtful to the common good.” He wants to smash computers. He wants to control and curtail data. He wants to reduce information .

No. Controlling information — call it data or call it knowledge — is never the solution, not in a free and enlightened society (not especially at the call of a journalist). If regulate you must, then regulate information’s use: You are free to know that I am 65 years old but you are not free to discriminate against me on the basis of that knowledge. Don’t outlaw facial recognition for police — as Bernie Sanders now proposes — instead, police how they use it. Don’t turn “machine learning” into a scare word and forbid it — when it can save lives — and be specific, bringing real evidence of the harms you anticipate, before cutting off the benefits. On this particular topic, I recommend Benedict Evans’ wise piece comparing today’s issues with facial recognition to those we had with databases at their introduction.

Here is where Tarnoff ends. Am I the only one who sees the irony in the greatest progressive newspaper of the English-speaking world coming out against progress?

The zero-carbon commonwealth of the future must empower people to decide not just how technologies are built and implemented, but whether they’re built and implemented. Progress is an abstraction that has done a lot of damage over the centuries. Luddism urges us to consider: progress towards what and progress for whom? Sometimes a technology shouldn’t exist. Sometimes the best thing to do with a machine is to break it.

Save us from the doomsayers.

The post ‘Decomputerize?’ Over My Dead Laptop! appeared first on BuzzMachine.

September 17, 2019

How the Dystos Defeated the Technos: A dystopian vision

History 302 — Fall semester, 2032 — Final essay

[This is not prediction about tomorrow; it is extrapolation from today -Ed.]

Summary

This paper explores the victory of technological dystopians over technologists in regulation, legislation, courts, media, business, and culture across the United States, Europe, and other nations in the latter years of what is now known as the Trump Time.

The key moment for the dystos came a decade ago, with what Wired.com dubbed the Unholy Compromise of 2022, which found Trumpist conservatives and Warrenite liberals joining forces to attack internet companies. Each had their own motives — the Trumpists complaining about alleged discrimination against them when what they said online was classified as hate speech; the liberals inveighing against data and large corporations. It is notable that in the sixteen years of Trump Time, virtually nothing else was accomplished legislatively — not regarding climate, health care, or guns — other than passing anti-tech, anti-net, and anti-data laws.