Jeff Jarvis's Blog, page 15

January 11, 2018

Facebook’s changes

[Disclosure: I raised $14 million from Facebook, the Craig Newmark and Ford foundations, and others to start the News Integrity Initiative . I personally receive no money from and am independent of Facebook.]

So, here’s what’s on my mind about Facebook’s changes, just announced by Mark Zuckerberg, to “prioritize posts that spark conversations and meaningful interactions between people” over content from media and brands.

Yes, I’m worried. Let me start there.

I’m worried that now that Facebook has become a primary distributor of news and information in society, it cannot abrogate its responsibility — no matter how accidentally that role was acquired — to help inform our citizenry.

I’m worried that news and media companies — convinced by Facebook (and in some cases by me) to put their content on Facebook or to pivot to video — will now see their fears about having the rug pulled out from under them realized and they will shrink back from taking journalism to the people where they are having their conversations because there is no money to be made there.

I’m worried for Facebook and Silicon Valley that both media and politicians will use this change to stir up the moral panic about technology I see rising in Europe and now in America.

But…

I am hopeful that Facebook’s effort to encourage “meaningful interactions” could lead to greater civility in our conversations, which society desperately needs. The question is: Will Facebook value and measure civility, intelligence, and credibility or mere conversation? We know what conversation alone brings us: comments and trolls. What are “meaningful interactions?”

And…

I wish that Facebook would fuel and support a flight to quality in news. Facebook has lumped all so-called “public content” into one, big, gnarly bucket. It is is dying to get rid of the shit content that gets them into political and PR trouble and that degrades the experience on Facebook and in our lives. Fine. But they must not throw the journalistic baby out with the trolly bathwater. Facebook needs to differentiate and value quality content — links to The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Guardian, and thousands of responsible, informative, useful old and new news outlets around the world.

I wish that Facebook would make clear that it will not use this change to exploit media companies for more advertising revenue when the goal is to inform the public.

I wish that Facebook would not just connect us with the people we know and agree with — our social filter bubbles — but also would devote effort to making strangers less strange, to robbing the demagogues and hate mongers of their favorite weapon: the Other. That, I firmly believe, is the most valuable thing Facebook could do to combat polarization in our world: creating safe spaces where people can share their lives and perspectives with others, helping to build bridges among communities.

I wish that Facebook would work with journalists to help them learn how to use Facebook natively to inform the public conversation where and when it occurs. Until now, Facebook has tried to suck up to media companies (and by extension politicians) by providing distribution and monetization opportunties through Instant Articles and video. Oh, well. So much for that. Now I want to see Facebook help news media make sharable journalism and help them make money through that. But I worry that news organizations will be gun-shy of even trying, sans rug.

So…

I have been rethinking my definition of journalism. It used to be: helping communties organize their knowledge to better organize themselves. That was an information-based definition.

After our elections in the U.S., the U.K., Austria, Germany, and elsewhere, I have seen that civility is a dire need and a precondition for journalism and an informed society. So now I have a new definition for journalism, an imperative that I believe news organizations share with Facebook (if it is serious about building communities).

My new definition of journalism: convening communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation, reducing polarization and building trust through helping citizens find common ground in facts and understanding.

Will Facebook’s changes help or hurt that cause? We shall see.

LATER: One more thought overnight on what publishers and Facebook should do now: Facebook makes it clear that the best way to get distribution there is for users to share and talk about your links. Conversation is now a key measure of value in Facebook.

The wrong thing to do would be to make and promote content that stirs up short and nasty conversation: “Asshole.” “Fuck you.” “No, fuck you, troll.” “Cuck.” “Nazi.” You know the script. I don’t want to see media move from clickbait to commentbait. Facebook won’t value that. No one will.

The right thing to do — as I have been arguing for almost two years — is to bring journalism to people on Facebook (and Twitter and Snap and Instagram and YouTube…) natively as part of people’s conversations. The easiest example, which I wrote about here, is the meme that someone passes along because it speaks for them, because it adds facts and perspectives to their conversation. There are many other forms and opportunities to make shareable, conversational journalism; a colleague is planning to create a course at CUNY Journalism School around just that.

The problem that will keep publishers from doing this is that there are few ways to monetize using Facebook as Facebook should be used. I’ve been arguing to Facebook for more than two years that they should see Jersey Shore Hurricane News as a model of native news on Facebook — with its loyal members contributing and conversing about their community — and that they should help its creator, Justin Auciello, make money there. Instead, Facebook has had to play to large, established publishers’ desires to distribute the content they have. So Facebook created formats for self-contained content — Instant Articles and videos — with the monetization within. Facebook and publishers painted themselves into a corner by trying to transpose old forms of media into a new reality. Now they’re admitting that doesn’t work.

But journalism and news clearly do have a place on Facebook. Many people learn what’s going on in the world in their conversations there and on the other social platforms. So we need to look how to create conversational news. The platforms need to help us make money that way. It’s good for everybody, especially for citizens.

The post Facebook’s changes appeared first on BuzzMachine.

December 29, 2017

Death to the Mass(es)!

without a shared reality, democracy may not be possible https://t.co/rvjvEsxkck

— Anne Applebaum (@anneapplebaum) December 29, 2017

I am not sure it’s possible to fully appreciate the implications of this sort of thing. Basically all democratic theory is built around the idea people have a roughly accurate and shared view of what’s going on. What if they don’t? https://t.co/dfmG5fQ3va

— Ezra Klein (@ezraklein) December 29, 2017

44 percent of Republicans think Trump has repealed Obamacare.https://t.co/AfgrvFBy4W

— Sarah Kliff (@sarahkliff) December 27, 2017

In the tweets above, leading journalists Ezra Klein and Anne Applebaum reflect the accepted wisdom, raison d’être, and foundational myth of their field: that journalism exists to align the nation upon a common ground of facts, so a uniformly informed mass of citizens can then manage their democracy.

The idea that the nation can and should share one view of reality based on one set of facts is the Cronkite-era myth of mass media: And that’s the way it is.But it wasn’t. The single shared viewpoint was imposed by the means of media production: broadcast uniformity replaced media diversity.

Now that era is over. What the internet kills is the mass media business model, with it mass media, and with it the idea of “the mass” as the homogenized, melted pot of citizens.

I’ll argue that we are returning to a media model that existed before broadcast: with many voices from and for many worldviews.

We are also returning to an earlier meaning of the word “mass” — from “mass market” to “the masses” as the political mob, the uninformed crowd, the ruly multitude … Trump’s base, in other words. That’s what the tweets above lament: a large proportion of the nation (at least ≈30%) who accept what is fed to them by Fox News and fake news and come out believing, just for example, that Obamacare is dead. What are we to do?

The answer isn’t to hope for a return to the Cronkite myth, for it was a myth. Mainstream media did not reflect reality for countless unreflected, underrepresented, and underserved communities; now, thanks to the net, we can better hear them. And mainstream media did not uniformly inform the entire nation; we just couldn’t know who all was uninformed, but now we have a better sense of our failings.

In 1964, E.V. Walter examined the shift from “the masses” to “mass” in his paper, Mass Society: The late stages of an idea in Social Research. He wrote (his emphases):

In the historical course of the idea, the decade 1930–1939 is a watershed. Before those years, thinking about mass behavior was restricted to dealing with the “mass” as a part of society, examining the conditions that produced it, the types of actions peculiar to it and their implications. After that time, the characteristics of the “mass” were attributed to society as a whole. This change was associated with significant historical events. One was the development of mass media…. The other was the more traumatic development of totalitarian systems…

Mass media, mass marketing, and mass production turned the ugly masses, the mobs, into the good mass, the marketplace-of-all to whom we sold uniform products (news, deodorant, politicians), convincing them that everyone should like what everyone else likes: the rule of the Jones. Well, good-bye to all that.

And so we are properly freaked out today: The mass isn’t a cohesive whole anymore (or now we know better). The masses have re-emerged as a mob and have taken over the country. We’ve seen how this played out before with the rise of totalitarian states riding on the shoulders of unruly, uninformed, angry crowds. “[T]he masses, by definition, neither should nor can direct their own personal existence, and still less rule society in general,” José Ortega y Gasset properly fretted in 1930 in The Revolt of the Masses.

So what do we do? Let’s start by recalling that before the 1920s and radio and the 1950s and television, media better reflected the diversity of society with newspapers for the elite, the working class, the immigrant (54 papers were published in New York in 1865; today we can barely scrape together one that covers the city effectively). Some of those newspapers were scurrilous and divisive. The yellow journalism rags could lie worse than even Fox News and Breitbart. Yet the nation survived and managed its way through an industrial revolution, a civil war, a Great Depression, and two world wars, emerging as a relatively intact democracy. How?

It is tempting to consider ignoring and writing off as hopeless the masses, the third of Americans who take Fox and Trump at their words. Clearly that would not be productive. These people managed to elect a president. That’s how they showed the rest of us they cannot be ignored. I worry about an effort to return to rule by the elite because the elites (the intelligent and the informed) are not the same as the powerful (see: Congress).

It is tempting, too, to pay too much attention to that so-called base, reporting on the lies and myths they believe without challenge. This presents two problems. The first, as pointed out by Ezra Klein, is that the election hinged not on the base but on the hinge.

I've written this before, but the idea of these "Trump country" stories is you can't understand Trump's win, or his 2020 chances, unless you understand his diehard voters. That's backwards. Trump's political success depends on his least diehard voters. https://t.co/PTKkVhAq6s

— Ezra Klein (@ezraklein) December 27, 2017

The second problem is that by paying so much attention to that base, we risk ignoring the majority of Americans who don’t believe these lies, who don’t approve of Trump’s behavior, who don’t approve of the tax bill just signed. As my Twitter friends love to point out, where have you seen the empathetic stories listening to the plurality of voters who elected Hillary Clinton?

The problem is that we in media keep seeking to cadge together a mass that makes sense. We don’t know how to — or have lost from our ancestral memory the ability to — serve diverse communities.

I argue that one solution is not just diversity in the newsrooms we have but diversity in the news and media ecosystem as a whole, with new and better outlets serving and informing many communities, owned by those communities: African-Americans, Latino-Americans, immigrant Americans, old Americans, young Americans, and, yes, conservative Americans.

We need to work with Facebook particularly to find ways to build bridges among communities, so the demagogues cannot fuel and exploit fear of strangers.

We need to work on better systems of holding both politicians and media to account for lies. Fact-checking is a start but is insufficient. Is there any way to shame Fox News into telling the truth? Is there any way to let its viewers know how they are being lied to and used?

We need to listen to James Carey’s lessons about journalism as transmission of fact (that’s what the exchange above is about) to journalism as a ritual of communication. This is why we need to examine new forms of journalism. (This is why we’re looking to start a lab at the CUNY J-school and why I’m leading a brief class next month in Comedy as a Tool of Journalism — and Journalism as a Tool of Comedy.)

What makes me happy about the Twitter exchange atop this post is that it resets the metric of journalistic success away from audience and attention and toward the outcome that matters: whether the public is informed or not. “Not” should scare the shit out of us.

I’m working on a larger piece (maybe a book or a part of one) about post-mass society and the many implications of this shift. A slice of it is how the mass-media mindset affects our view of our work in journalism and of the structure of politics and society. We need a reset. The bad guys — trolls and Russians, to name a few — have learned that talking to the mass is a waste of time and money and targeting is more effective. They have learned that creating social tokens is a more effective means of informing people than creating articles. We have lessons to learn even from them.

The mass is dead. I don’t regret its passing. In some ways, we need to learn how society managed before media helped create this monster. In other ways, we need to recognize how we can use new tools — the ones the bad guys have exploited first — to better connect and inform and manage society. Let’s begin by recognizing that the goal is not to create one shared view of reality but instead to inform discussion and deliberation among many different communities with different perspectives and needs. That’s what society needs. That’s what journalism must become

The post Death to the Mass(es)! appeared first on BuzzMachine.

December 22, 2017

Democracy Dies in the Light

When the nation’s representatives pass sweeping tax legislation that the majority of voters do not want and that will in the long-run harm most citizens — helping instead corporations, a small, rich elite (including donors), and the politicians themselves — there can be only one interpretation:

Our representatives no longer represent the public; they do not care to. American democracy has died.

Democracy didn’t die in darkness. It died in the light.

The full glare of journalism was turned on this legislation, its impact and motives, but that didn’t matter to those who had the power to go ahead anyway. Journalism, then, proved to be an ineffective protector of democracy, just as it is proving ineffective against every other attack on democracy’s institutions by this gang. Fox News was right to declare a coup, wrong about the source. The coup already happened. The junta is in power. In fact, Fox News led it. We have an administration and Congress that are tearing down government institutions — law enforcement, the courts, the State Department and foreign relations, safety nets, consumer protection, environmental protection — and society’s institutions, starting with the press and science, not to mention truth itself. The junta is, collaborative or independently, doing the bidding of a foreign power whose aim is to get democracy to destroy itself. Journalism, apparently, was powerless to stop any of this.

I don’t mean to say that journalism is solely to blame. But journalism is far from blameless. I have sat in conferences listening to panels of journalists who blame the public they serve. These days, I watch journalists blame Facebook, as if the sickness in American democracy is only a decade old and could be turned on by a machine. I believe that journalism must engage in its own truth and reconciliation process to learn what we have done wrong: how our business models encourage discord and reduction of any complexity to the absurd; how we concentrate on prediction over information and education;how we waste journalistic resource on repetition; how we lately have used ourfalse god of balance to elevate the venal to the normal; how we are redlining quality journalism as a product for the elite. I don’t believe we can fix journalism until we recognize its faults. But I’ll save that for another day. Now I want to ask a more urgent question given the state of democracy.

What should journalism do? Better: What should journalism be? It is obviously insufficient to merely say “this happened today” or “this could happen tomorrow.”

What should journalism’s measures of value be? A stronger democracy? An informed public conversation? Civil discourse? We fail at all those measures now. How can journalism change to succeed at them? What can it do to strengthen — to rescue — democracy? That is the question that consumes me now.

I will start here. We must learn to listen and help the public listen to itself. We in media were never good at listening — not really — but in our defense our media, print and broadcast, were designed for speaking. The internet intervened and enabled everyone to speak but helped no one listen. So now we live in amid ceaseless dissonance: all mouths, no ears. I am coming to see that civility — through listening, understanding, and empathy — is a necessary precondition to learning, to accepting facts and understanding other positions, to changing one’s mind and finding common ground. Thus I have changed my own definition of journalism.

My definition used to be: Helping communities organize their knowledge to better organize themselves. That was conveniently broad enough to fit most any entrepreneurial journalism students’ ideas. It was information based, for that was my presumption — the accepted wisdom — about journalism: It lives to inform. Now I have a new definition of journalism:

To convene communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation.

Journalism — and, I’d argue, Facebook and internet platforms — share this imperative to reduce the polarization we all helped cause by helping citizens find common ground.

This is the philosophy behind our Social Journalism program at CUNY. It is why we at the News Integrity Initiative invested in Spaceship Media’s work, to convene communities in conflict into meaningful conversation. But that is just the beginning.

Clearly, journalism must devote more of its resources to investigation, to making sure that the powerful know they are watched, whether they give a damn or not. Journalism must understand its role as an educator and measure its success or failure based on whether the public is more informed. Journalism and the platforms need to provide the tools for communities to organize and act in collaborative, constructive ways. I will leave this exploration, too, for another day.

We are in a crisis of democracy and its institutions, including journalism. The solutions will not be easy or quick. We cannot get there if we assume what we are living through is a new normal or worse if we make it seem normal. We cannot succeed if we assume our old ways are sufficient for a new reality. We must explore new goals, new paths, new tools, new measures of our work.

The post Democracy Dies in the Light appeared first on BuzzMachine.

October 4, 2017

Moral Authority as a Platform

[image error]

[See my disclosures below.*]

Since the election, I have been begging the platforms to be transparent about efforts to manipulate them — and thus the public. I wish they had not waited so long, until they were under pressure from journalists, politicians, and prosecutors. I wish they would realize the imperative to make these decisions based on higher responsibility. I wish they would see the need and opportunity to thus build moral authority.

Too often, technology companies hide behind the law as a minimal standard. At a conference in Vienna called Darwin’s Circle, Palantir CEO Alexander Karp (an American speaking impressive German) told Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern that he supports the primacy of the state and that government must set moral standards. Representatives of European institutions were pleasantly surprised not to be challenged with Silicon Valley libertarian dogma. But as I thought about it, I came to see that Karp was copping out, delegating his and his company’s ethical responsibility to the state.

At other events recently, I’ve watched journalists quiz representatives of platforms about what they reveal about manipulation and also what they do and do not distribute and promote on behalf of the manipulators. Again I heard the platforms duck under the law — “We follow the laws of the nations we are in,” they chant — while the journalists pushed them for a higher moral standard. So what is that standard?

Transparency should be easy. If Facebook, Twitter, and Google had revealed that they were the objects of Russian manipulation as soon as they knew it, then the story would have been Russia. Instead the story is the platforms.

I’m glad that Mark Zuckerberg has said that in the future, if you see a political ad in your feed, you will be able to link to the page or user that bought it. I’d like the platforms to all go farther:

First, internet platforms should make every political ad available for public inspection, setting a standard that goes far beyond the transparency required of political advertising on broadcast and certainly beyond what we can find out about dark political advertising in direct mail and robocalls. Why shouldn’t the platforms lead the way?

Second, I think it is critical that the platforms reveal the targeting criteria used for these political ads so we can see what messages (and lies and hate) are aimed at whom.

Third, I’d like to see all this data made available to researchers and journalists so the public — the real target of manipulation — can learn more about what is aimed at them.

The reason to do this is just not to avoid bad PR or merely to follow the law, to meet minimal expectations. The reason to do all this is to establish public responsibility consumate with the platforms’ roles as the proprietors of so much of the internet and thus the future.

In What Would Google Do?, I praised the Google founders’ admonition to their staff — “Don’t be evil” — as a means to keep the company honest. The cost of doing evil in business has risen as customers have gained the ability to talk about a company and as anyone could move to a competitor with a click. But that, too, was a minimal standard. I now see that Google — and its peers — should have evolved to a higher standard:

“Do good. Be good.”

I don’t buy the arguments of cynics who say it is impossible for a corporation to be anything other than greedy and evil and that we should give up on them. I believe in the possibility and wisdom of enlightened self-interest and I believe we can hold these companies to an expectation of public spirit if not benevolence. I also take Zuck at his word when he asks forgiveness “for the ways my work was used to divide people rather than bring us together,” and vows to do better. So let us help him define better.

The caveats are obvious: I agree with the platforms that we do not want them to become censors and arbiters of right v. wrong; to enforce prohibitions determined by the lowest-common-demoninators of offensiveness; to set precedents that will be exploited by authoritarian governments; to make editorial judgments.

But doing good and being good as a standard led Google to its unsung announcement last April that it would counteract manipulation of search ranking by taking account of the reliability, authority, and quality of sources. Thus Google took the side of science over crackpot conspirators, because it was the right thing to do. (But then again, I just saw that Alternet complains that it and other advocacy and radical sites are being hit hard by this change. We need to make clear that fighting racism and hate is not to be treated like spreading racism and hate. We must be able to have an open discussion about how these standards are being executed.)

Doing good and being good would have led Facebook to transparency about Russian manipulation sooner.

Doing good and being good would have led Twitter to devote resources to understanding and revealing how it is being used as a tool of manipulation — instead of merely following Facebook’s lead and disappointing Congressional investigators. More importantly, I believe a standard of doing good and being good would lead Twitter to set a higher bar of civility and take steps to stop the harassment, stalking, impersonation, fraud, racism, misogyny, and hate directed at its own innocent users.

Doing good and being good would also lead journalistic institutions to examine how they are being manipulated, how they are allowing Russians, trolls, and racists to set the agenda of the public conversation. It would lead us to decide what our real job is and what our outcomes should be in informing productive and civil civic conversation. It would lead us to recognize new roles and responsibilities in convening communities in conflict into uncomfortable but necessary conversation, starting with listening to those communities. It should lead us to collaborate with and set an example for the platforms, rather than reveling in schadenfreude when they get in trouble. It should also lead us all — media companies and platforms alike — to recognize the moral hazards embedded in our business models.

I don’t mean to oversimplify even as I know I am. I mean only to suggest that we must raise up not only the quality of public conversation but also our own expectations of ourselves in technology and media, of our roles in supporting democratic deliberation and civil (all senses of the word) society. I mean to say that this is the conversation we should be having among ourselves: What does it mean to do and be good? What are our standards and responsibilities? How do we set them? How do we live by them?

Building and then operating from that position of moral authority becomes the platform more than the technology. See how long it is taking news organizations to learn that they should be defined not by their technology — “We print content” — but instead by their trust and authority. That must be the case for technology companies as well. They aren’t just code; they must become their missions.

* Disclosure: The News Integrity Initiative , operated independently at CUNY’s Tow-Knight Center, which I direct, received funding from Facebook, the Craig Newmark Philanthropic Fund, and the Ford Foundation and support from the Knight and Tow foundations, Mozilla, Betaworks, AppNexus, and the Democracy Fund.

The post Moral Authority as a Platform appeared first on BuzzMachine.

June 12, 2017

Our problem isn’t ‘fake news.’ Our problems are trust and manipulation.

“Propaganda is the executive arm of the invisible government.”

— Edward Bernays, Propaganda (1928)

“Fake news” is merely a symptom of greater social ills. Our real problems: trust and manipulation. Our untrusted — and untrustworthy — institutions are vulnerable to manipulation by a slough of bad guys, from trolls and ideologues to Russians and terrorists, all operating under varying motives but similar methods.

Trust is the longer-term problem — decades- or even a century-long. But if we don’t grapple with the immediate and urgent problem of manipulation, those institutions may not live to reinvent themselves and earn the public’s trust back with greater inclusion, equity, transparency, responsiveness, and honesty. At the News Integrity Initiative, we will begin to address both needs.

Here I want to examine the emergency of manipulation with a series of suggestions about the defenses needed by many sectors — not just news and media but also platforms, technology companies, brands, marketing, government, politics, education. These include:

Awareness. As Storyful asks, “Who’s your 4chan correspondent?” If we do not understand how we are being manipulated, we become the manipulators’ agents.

Starving the manipulators of money but more importantly of attention, exposing their methods without giving unwarranted attention to their messages.

Learning from the success of the manipulators’ methods and co-opting them to bring facts, journalism, and truth to the public conversation where it occurs.

Bringing greater transparency and accountability to our institutions. In journalism’s case, this means showing our work, recognizing the danger of speed (a game the manipulators will always win), and learning to listen to the public to reflect and serve communities’ distinct needs. In the platforms’ case, it means accounting for quality in algorithmic decisions and helping users better judge the sources of information. In the ad industry’s case, it means bringing tools to bear so we can hold brands, agencies, and networks responsible for what they choose to support.

I will explore these suggestions in greater detail after first examining the mechanisms and motives of manipulation. I claim no expertise in this; I’m just sharing my learning as it occurs.

I became convinced that manipulation is the immediate emergency thanks to danah boyd of Data & Society, which recently issued an excellent report by Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis, “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online.” They catalog who is trying to manipulate media — trolls, ideologues, hate groups, conspiracy theorists, gamergaters; where and how they do it — via blogs, sites, message boards, and social media; and why they do it — for money, for hate, for power, to cause polarization, to disrupt institutions, or for the lulz.

In discussing manipulation, it is important to also examine Russian means and methods. For that, I recommend two provocative reports: the NATO Defense College’s “Handbook of Russian Information Warfare” by Keir Giles and the RAND Corporation’s “The Russian ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model” by Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews.

Says danah: “Our media, our tools, and our politics are being leveraged to help breed polarization by countless actors who can leverage these systems for personal, economic, and ideological gain. Sometimes, it’s for the lulz. Sometimes, the goals are much more disturbing.”

In short: We are being used.

Russian manipulation

I found the NATO manual particularly worrying, for in examining what Russia has done to manipulate information in Ukraine and elsewhere, we see the script for much of what is happening now in the United States. I’m not suggesting Russia is behind this all but instead that all the manipulators learn from each other while we in media do not.

NATO emphasizes that Russia does not think of this as cyber warfare but instead as information warfare. “Russia refers to ‘information space,’” Rand says, “and includes in this space both computer and human information processing, in effect the cognitive domain.” Human psychology, that is. Thus, Russia’s weapons work neatly not only online but also in mainstream media, enabling it to “steal, plant, interdict, manipulate, distort or destroy information.”

“Information,” says the author of a Russian paper NATO cites, “has become the same kind of weapon as a missile, a bomb, and so on [but it] allows you to use a very small amount of matter or energy to begin, monitor, and control processes whose matter and energy parameters are many orders of magnitude larger.”

Russia has weaponized a new chain reaction in social media. To what end?

“The main aim of information-psychological conflict is regime change,” says another Russian paper, “by means of influence on the mass consciousness of the population — directing people so that the population of the victim country is induced to support the aggressor, acting against its own interests.”

Sound familiar? Sound chilling? See, our problem is not just some crappy content containing lies and stupidity. The problem is a powerful strategy to manipulate you.

Our institutions help them. “Russia seeks to influence foreign decision-making by supplying polluted information,” NATO says, “exploiting the fact that Western elected representatives receive and are sensitive to the same information flows as their voters.” That is, when they play along, the journalism, the open internet, and the free speech we cherish are used against us. “Even responsible media reporting can inadvertently lend authority to false Russian arguments.” Therein lies the most insidious danger that danah boyd warns against: playing into their hands by giving them attention and calling it news.

Their goal is polarization — inside a nation and among its allies — and getting a country to eat its own institutions. Their tactics, in the words of former NATO press officer Ben Nimmo, aim to “‘dismiss, distract, dismay’ and can be achieved by exploiting vulnerabilities in the target society, particularly freedom of expression and democratic principles.” They use “‘mass information armies’ conducting direct dialogue with people on the internet” and describe information weapons as “more dangerous than nuclear ones.” Or as the Russian authors of a paper NATO cites say: “The mass media today can stir up chaos and confusion in government and military management of any country and instill ideas of violence, treachery, and immorality and demoralize the public.”

Feel demoralized these days? Then it’s working.

The Russian paper on information-psychological warfare that NATO quotes lists Russia’s key tactics, which— like their goals and outcomes — will sound eerily familiar:

The primary methods of manipulating information used by the mass media in the interests of information-psychological confrontation objectives are:

Direct lies for the purpose of disinformation….;

Concealing critically important information;

Burying valuable information in a mass of information dross…;

Terminological substitution: use of concepts and terms whose meaning is unclear or has undergone qualitative change, which makes it harder to form a true picture of events; [see “fake news”]

Introducing taboos on specific forms of information or categories of news…; [see “political correctness”]

Providing negative information, which is more readily accepted by the audience than positive.

More tactics: Trolls and bots are used to create a sense of public opinion so it is picked up by media. Journalists are harassed and intimidated, also by trolls and bots. They exploit volume: “When information volume is low,” says RAND, “recipients tend to favor experts, but when information volume is high, recipients tend to favor information from other uses.” And they exploit speed: “Russian propaganda has the agility to be first,” Rand observes. “It takes less time to make up facts than it does to verify them.” And the first impression sets the agenda.

At the highest level, they attack truth. “Multiple untruths, not necessarily consistent, are in part designed to undermine trust in the existence of objective truth, whether from media or from official sources,” says NATO. “This contributes to eroding the comparative advantages of liberal democratic societies when seeking to counter disinformation.” [My emphasis]

What do we in journalism do in response? We fact-check. We debunk. We cover them. But that’s precisely what they want us to do for then we give them attention. Says former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt: “You could spend every hour of every day trying to bat down every lie, to the point where you don’t achieve anything else. And that’s exactly what the Kremlin wants.”

Western manipulation

Again, I am not saying the Russia is behind all media manipulation. Far from it. But as Hillary Clinton suggested, the Macedonian fake news factory that went after her learned their tricks somewhere. Trolls and manipulators learn from each other and so we must learn about them ourselves.

In their Data & Society report, Marwick and Lewis do considerable forensic research into the dissemination of pro-Trump populist messages, which spread (1) “through memes shared on blogs and Facebook, through Twitter bots, through YouTube channels;” sometimes passing through even (2) the Trump’s own Twitter account; until they are then (3) “propagated by a far-right hyper-partisan press rooted in conspiracy theories and disinformation” (read: Breitbart et al); until (4) “they influenced the agenda of mainstream news sources.” From 4chan and 8chan to Alex Jones to Breitbart to Trump to Fox to CNN to you.

Just as “fake news” is a sloppy label, so is “alt-right.” Marwick and Lewis dissect that worm into its constituent segments: “an amalgam of conspiracy theorists, techno-libertarians, white nationalists, Men’s Rights advocates, trolls, anti-feminists, anti-immigration activists, and bored young people.” They “leverage both the techniques of participatory culture and the affordances of social media to spread their various beliefs” and “target vulnerabilities in the news media ecosystem to increase the visibility of and audience for their messages.” What ties them together is some measure of belief — anti-establishment, anti-multiculturalism, anti-globalism, anti-feminism, anti-Semitic, anti-political correctness, and nationalist and racist ideologies. But what mostly links them is their techniques. As trolls, they aim for reaction for reaction’s sake. They mock the “type of tragedy-of-the-week moral panic perpetrated by talk shows and cable news,” as observed by net scholar Whitney Phillips. And they exploit Poe’s Law, playing “with ambiguity in such a way that the audience is never quite sure whether or not they are serious.”

They hack social media, media, and ultimately attention and democracy.

And therein lies the paradoxical vice in which we find ourselves: When we address, check, and attack them, we feed them with attention. Hillary Clinton learned the hard way that “by addressing [fringe] ideas, she also gave them new visibility and legitimacy.” She “inadvertently cemented their importance.” Say Marwick and Lewis: “By getting the media to cover certain stories, even by debunking them, media manipulators are able to influence the public agenda.”

And it is only going to get worse. At a World Economic Forum discussion on the topic that I facilitated in San Francisco, I heard a few frightening predictions: First, the bad guys’ next targets will be “pillars of society” — doctors, pastors, auditors, judges. Second, communities will devolve into “belief tribes” where anyone who disagrees with an orthodoxy of opinion will be branded a shill. Third, augmented reality will make it easier to fake not just text and photo but also audio and video and thus identity. And fourth, what I am coming to fear greatly: a coming Luddite rebellion against technology will separate us into “connected and disconnected tribes.”

At another WEF discussion, I heard from executives of NGOs, governments, banks, consumer brands, pharma, accounting, and media that they are beginning to recognize the emergency we face. Good.

So WTF do we do?

We in media and other institutions must develop new strategies that account for the very new tactics undertaken by our new enemies. We must go far beyond where we are now.

Today, some are tackling falsehoods by fact-checking. Some want to enhance the public’s critical thinking through so-called news literacy. Some are compiling lists and signals of vice (NII is collaborating with Storyful and Moat in one such effort) and of virtue in sources. Google is seeking to account for the reliability, authority, and quality of sources in its ranking. Facebook is killing the fake accounts used to mimic public conversation. (If only Twitter would get aggressive against malevolent bots and fakes.) I’ve seen no end of (Quixotic, I believe) efforts to rank sites for quality.

These are fine as far as they go, but rather than attacking the facts, sources, and accounts — merely tactics — we need to go after the real symptom (manipulation) and the real ill (trust). “The first step is to recognize that this is a nontrivial challenge,” RAND understates. Some of the suggestions I’m thinking about:

Build awareness: News media must recognize how and when they are the objects of manipulation. I so like Storyful’s idea of hiring a 4chan correspondent that we at NII are thinking of underwriting just such a journalist to help news organizations understand what is happening to them, giving them advance notice of the campaigns against them.

I also want to see all the experts I quote above — and others on my growing list — school media and other sectors in how they are being manipulated and what they could do in defense. Without that, they become trolls’ toys and Putin’s playthings.

Share intelligence: Besides 4chan correspondents, major newsrooms should have threat officers whose job it is to recognize manipulation before it affects news coverage and veracity. These threat officers should be communicating with their counterparts in newsrooms elsewhere. At the WEF meetings, I was struck how major brands staff war rooms to deal with disinformation attacks yet they don’t share information among themselves. So let’s establish networks of security executives in and across sectors to share intelligence, threat assessments, warnings, best practices, and lessons. To borrow the framing of NII supporter Craig Newmark, these could be NATOs for journalism, media, brands, and so on, established to both inform and protect each other. NII would be eager to help such efforts.

Starve them: There are lots of efforts underway — some linked above — to starve manipulators of their economic support through advertising, helping ad networks, agencies, and brands avoid putting their money behind the bad guys (and, I hope, choosing instead to support quality in media). We also need to put the so-called recommendations engines (Revcontent, Adblade, News Max, as well as Taboola and Outbrain) on the spot for supporting and profiting fake news — likewise for the publishers that distribute their dross. Even this takes us only so far.

The tougher challenge — especially for news organizations — is starving the manipulators of what they crave and feed upon: attention. I can hear journalists object that they have to cover what people are talking about. But what if people aren’t talking about it; bots are? What if the only reason people end up talking is because a polluted wellspring of manipulation rose from a few fanatics on 4chan to Infowars to Breitbart to Fox to MSM and — thanks to the work of a 4chan correspondent — you now know that? I can also hear journalists argue that everything I’ve presented here makes manipulators a story worth covering and telling the public about. Yes, but only to an extent. I’ll argue that journalism should cover the manipulators’ methods but not their messages.

Get ahead of them: RAND warns that there is no hope in answering the manipulators, so it is wiser to compete with them. “Don’t direct your flow of information directly back at the firehose of falsehood; instead, point your stream at whatever the firehose is aimed at, and try to push that audience in more productive directions…. Increase the flow of persuasive information and start to compete.” In other words, if you know — thanks to your intelligence network and 4chan correspondent — that the bad guys are going to go after, say, vaccines, than get there first and set the public agenda with journalism and facts about it. Warn the public about how someone will try to manipulate them. Don’t react later. Inform first.

Learn from them: We in media continue to insist that the world has not changed around us, that citizens must come to us and our fonts of information to be informed. No! We must change how we operate, taking journalism to the public where and when their conversation occurs. We should learn from the bad guys’ lessons in spreading disinformation so we can use their techniques to spread information. We also should not assume that all our tried-and-true tools — articles, explainers, fact-checking — can counteract manipulators’ propaganda. We must experiment and learn what does and does not persuade people to favor facts and rationality.

Rebuild yourself and your trust: Finally, we move from the symptoms to ailments. Our institutions are not trusted for many reasons and we must address those reasons. Media — not just our legacy institutions but also the larger media ecosystem — must become more equitable, inclusive, reflective of, and accountable to many communities. We must become more transparent. We must learn to listen first before creating the product we call content. Brands, government, and politics must also learn to listen first. These are longer-term goals.

The post Our problem isn’t ‘fake news.’ Our problems are trust and manipulation. appeared first on BuzzMachine.

May 2, 2017

Fueling a flight to quality

Storyful and Moat — together with CUNY and our new News Integrity Initiative*— have announced a collaboration to help advertisers and platforms avoid associating with and supporting so-called fake news. This, I hope, is a first, small step toward fueling a flight to quality in news and media. Add to this:

A momentous announcement by Ben Gomes, Google’s VP of engineering for Search, that its algorithms will now favor “quality,” “authority,” and “the most reliable sources” — more on that below.

The consumer revolts led online by Sleeping Giants and #grabyourwallet’s Shannon Coulter that kicked Bill O’Reilly off the air and are cutting off the advertising air supply to Breitbart.

The advertiser revolt led by The Guardian, the BBC, and ad agency Havas against offensive content on YouTube, getting Google to quickly respond.

These things — small steps, each — give me a glimmer of hope for supporting news integrity. I will even go so far as to say — below — that I hope this can mark the start of renewing support to challenged institutions — like science and journalism — and rediscovering the market value of facts.

The Storyful-Moat partnership, called the Open Brand Safety framework, first attacks the low-hanging and rotten fruit: the sites that are known to produce the worst fraud, hate, and propaganda. I’ve been talking with both companies for some time because supporting quality is an extension of what they already do. Storyful verifies social content that makes news; its exhaust is knowing which sites can’t be verified because they lie. Moat tells advertisers when they should not waste money on ads that are not seen or clicked on by humans. Its CTO, Dan Fichter, came to me weeks ago saying they could add a warning about content that is crap (my word) — if someone could help them define crap. That is where this partnership comes in.

My hope is that we build a system around many signals of both vice and virtue so that ad agencies, ad networks, advertisers, and platforms can weigh them according to their own standards and goals. In other words, I don’t want blacklists or whitelists; I don’t want one company deciding truth for all. I want more data so that the companies that promote and support content — and by extension users — can make better decisions.

The hard work will be devising, generating, and using signals of quality and crapness, allowing for many different definitions of each. The best starting point for discussion of a definition is from the First Draft Coalition’s Claire Wardle:

One set of signals is obvious: sites whose content is consistently debunked as fraudulent. Storyful knows; so do Politifact, Buzzfeed’s Craig Silverman, and Snopes. There are other signals of caution, for example a site’s age: An advertiser might want to think twice before placing its brand on a two-week-old Denver Guardian vs the almost-200-years-old Guardian. Facebook and Google have their own signals around suspicious virality.

But even more important, we need to generate positive signals of credibility and quality. The Trust Project endeavors to do that by getting news organizations to display and uphold standards of ethics, fact-checking, diversity, and so on. Media organizations also need to add metadata around original reporting, showing their work.

In talking about all this at an event we held at CUNY to kick off the News Integrity Initiative, I came to see that human effort will be required. Trust cannot be automated. I think there will be a need for auditing of media organizations’ compliance with pledges — an Audit Bureau of Circulations of good behavior — and for appeal (“I know we screwed up once but we’re good now”) and review (“Yes, we’re only two weeks old but so was the Washington Post once”).

Who will pay for that work? In the end, it will be the advertisers. But it is very much an open question whether they will pay more for the safety of associating with credible sources and for the societal benefit of putting their money behind quality. With the abundance the net creates, advertisers have relished paying ever-lower prices. With the targeting opportunities technology and programmatic ad marketplaces afford, they have put more emphasis on data points about users than the environment in which their ads and brands appear. Will public pressure from the likes of Sleeping Giants and #grabyourwallet change that and make advertisers and their agencies and networks go to the trouble and expense of seeking quality? We don’t know yet.

I want to emphasize again that I do not want to see single arbiters of trust, quality, authority, or credibility — not the platforms, not journalistic organizations, not any self-appointed judge — nor single lists of the good and bad. I do want to see more metadata about sources of information so that everyone in the media ecosystem — from creator to advertiser to platform to citizen — can make better, more informed decisions about credibility.

With that added metadata in hand, these companies must weigh it according to their own standards and needs in their own judgments and algorithms. That is what Google does every second. That is why Google News creator Krishna Bharat’s post about how to detect fake news in real-time is so useful. The platforms, he writes, “are best positioned to see a disinformation outbreak forming. Their engineering teams have the technical chops to detect it and the knobs needed to to respond to it.”

And that is also why I see Ben Gomes’ blog post as so important. Google’s head of Search engineering writes:

Last month, we updated our Search Quality Rater Guidelines to provide more detailed examples of low-quality webpages for raters to appropriately flag, which can include misleading information, unexpected offensive results, hoaxes and unsupported conspiracy theories….

We combine hundreds of signals to determine which results we show for a given query — from the freshness of the content, to the number of times your search queries appear on the page. We’ve adjusted our signals to help surface more authoritative pages and demote low-quality content…

I count this as a very big deal. Google and Facebook — like news media before them — contend that they are mirrors to the world. Their mirrors might well be straight and true but they must acknowledge that the world is cracked and warped to try to manipulate them. For months now, I have argued to the platforms — and will argue the same to news media — that they must be more transparent about efforts to manipulate them … and thus the public.

Example: A few months ago, if you searched on Google for “climate change,” you’d get what I would call good results. But if your query was “is climate change real?” you’d get some dodgy results, in my view. In the latter, Google was at least in part anticipating, as it is wont to do, the desires or expectations of the user under the rubric of relevance (as in, “people who asked whether climate change is real clicked on this”). But what if a third-grader also asks that question? Search ranking was also influenced by the volume of chatter around that question, without necessarily full regard to whether and how that chatter was manufactured to manipulate — that is, the huge traffic and engagement around climate-change deniers and the skimpy discussion around peer-reviewed scientific papers on the topic. But today, if you try both searches, you’ll find similar good results. That tells me that Google has made a decision to compensate for manufactured controversy and in the end favor the institution of science. That’s big.

On This Week in Google, Leo Laporte and I had a long discussion about whether Google should play that role. I said that Google, Facebook, et al are left with no choice but to compensate for manipulation and thus decide quality; Leo played the devil’s advocate, saying no company can make that decision; our cohost Stacey Higginbotham called time at 40 minutes.

Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg has made a similar decision to Google’s. He wrote in February: “It is our responsibility to amplify the good effects and mitigate the bad — to continue increasing diversity while strengthening our common understanding so our community can create the greatest positive impact on the world.” What’s good or bad, positive or not? As explained in an important white paper on mitigating manipulation, that is a decision Facebook will start to make as it expands it security focus “from traditional abusive behavior, such as account hacking, malware, spam and financial scams, to include more subtle and insidious forms of misuse, including attempts to manipulate civic discourse and deceive people.” That includes not just fake news but the fake accounts that amplify it: fake people.

I know there are some who would argue that I’m giving lie to my frequent contention that Google and Facebook are not media companies and that by defending their need to rule on quality, I am having them make editorial decisions. No, what they’re really defining is fakery: (1) That which is devised to deceive or manipulate. (2) That which intentionally runs counter to fact and accepted knowledge. Accepted by whom? By science, by academics, by journalism, even by government — that is, by institutions. Thus this requires a bias in favor of institutions at a time when every institution in society is being challenged because — thanks to the net — it can be. Though I often challenge institutions myself, I don’t do so in the way Trumpists and Brexiters do, trying to dismantle them for the sake of destruction.

In the process of identifying and disadvantaging fake news, Krishna Bharat urges the platforms to be transparent about “all news that has been identified as false and slowed down or blocked” so there is a check on their authority. He further argues: “I would expect them to target fake news narrowly to only encompass factual claims that are demonstrably wrong. They should avoid policing opinion or claims that cannot be checked. Platforms like to avoid controversy and a narrow, crisp definition will keep them out of the woods.”

Maybe. In these circumstances, defending credibility, authority, quality, science, journalism, academics, and even expertise — that is, facts — becomes a political act. Politics is precisely where Google and Facebook, advertisers and agencies do not want to be. But they are given little choice. For if they do not reject lies, fraud, propaganda, hate, and terrorism they will end up supporting it with their presence, promotion, and dollars. On the other hand, if they do reject crap, they will end up supporting quality. They each have learned they face an economic necessity to do this: advertisers so they are not shamed by association, platforms so they do not create user experiences that descend into cesspools. Things got so bad, they have to do good. See that glimmer of hope I see?

None of this will be easy. Much of it will be contentious. We who can must help. That means that media should add metadata to content, linking to original sources; showing work so it can be checked; upholding standards of verification; openly collaborating on fact-checking and debunking (as First Draft is doing across newsrooms in France); and enabling independent verification of their work. That means that the advertising industry must recognize its responsibility not only to the reputation of its own brands but to the health of our information and media ecosystem it depends on. That means Facebook, Google — and, yes, Twitter — should stand on the side of sense and civility against manufactured nonsense and manipulated incivility. That means media and platforms should work together to reinvent the advertising industry, moving past the poison of reach and clickbait to a market built on value and quality. And that means that we as citizens and consumers should support those who support quality and must take responsibility for not spreading lies and propaganda, no matter how fun it seems at the time.

What we are really seeing is the need to gather around some consensus of fact, authority, and credibility if not also quality. We used to do that through the processes of education, journalism, and democratic deliberation. If we cannot do that as a society, if we cannot demand that our fellow citizens — starting with the President of the United States— respect fact, then we might as well pack it in on democracy, education, and journalism. I don’t think we’re ready for that. Please tell me we’re not. What ideas do you have?

* Disclosure: The News Integrity Initiative, operated independently at CUNY’s Tow-Knight Center, which I direct, received funding and support from the Craig Newmark Philanthropic Fund; Facebook; the Ford, Knight, and Tow foundations; Mozilla; Betaworks; AppNexus; and the Democracy Fund.

The post Fueling a flight to quality appeared first on BuzzMachine.

April 24, 2017

Jimmy Wales’ new Wikitribune

Jimmy Wales changed encyclopedias and news while he was at it. And now he’s at it at it again, announcing a crowdfunding campaign to start Wikitribune, a collaborative news platform with “professional journalists and community contributors working side-by-side to produce fact-checked, global news stories. The community of contributors will vet the facts, help make sure the language is factual and neutral, and will to the maximum extent possible be transparent about the source of news posting full transcripts, video, and audio of interviews.” The content will be free with monthly patrons providing as much support as possible, advertising as little as possible.

Jimmy Wales changed encyclopedias and news while he was at it. And now he’s at it at it again, announcing a crowdfunding campaign to start Wikitribune, a collaborative news platform with “professional journalists and community contributors working side-by-side to produce fact-checked, global news stories. The community of contributors will vet the facts, help make sure the language is factual and neutral, and will to the maximum extent possible be transparent about the source of news posting full transcripts, video, and audio of interviews.” The content will be free with monthly patrons providing as much support as possible, advertising as little as possible.

I’m excited about this for a few reasons:

First, I see the need for innovation around new forms of news.

Next, I want some news sites to break the overwhelming and constant flow of news and allow us in the public to pull back and find answers to the question, “What do we know about…?” We already have plenty of streams of news; we also need repositories of knowledge around news topics. As Jimmy explained this to me, it will have the value of a wiki (and Wikipedia) in a new platform built to purpose.

Finally, of course, I am delighted to see news services that respect and collaborate with the public.

I am listed as an adviser, personally. You can sign up here.

The post Jimmy Wales’ new Wikitribune appeared first on BuzzMachine.

April 2, 2017

Real News

I’m proud that we at CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism and the Tow-Knight Center just announced the creation of the News Integrity Initiative, charged with finding ways to better inform the public conversation and funded thus far with $14 million by nine foundations and companies, all listed on the press release. Here I want to tell its story.

This began after the election when my good friend Craig Newmark — who has been generously supporting work on trust in news — challenged us to address the problem of mis- and disinformation. There is much good work being done in this arena — from the First Draft Coalition, the Trust Project, Dan Gillmor’s work at ASU bringing together news literacy efforts, and the list goes on. Is there room for more?

I saw these needs and opportunities:

First, much of the work to date is being done from a media perspective. I want to explore this issue from a public perspective — not just about getting the public to read our news but more about getting media to listen to the public. This is the philosophy behind the Social Journalism program Carrie Brown runs at CUNY, which is guided by Jay Rosen’s summary of James Carey: “The press does not ‘inform’ the public. It is ‘the public’ that ought to inform the press. The true subject matter of journalism is the conversation the public is having with itself.” We must begin with the public conversation and must better understand it.

Second, I saw that the fake news brouhaha was focusing mainly on media and especially on Facebook — as if they caused it and could fix it. I wanted to expand the conversation to include other affected and responsible parties: ad agencies, brands, ad networks, ad technology, PR, politics, civil society.

Third, I wanted to shift the focus of our deliberations from the negative to the positive. In this tempest, I see the potential for a flight to quality — by news users, advertisers, platforms, and news organizations. I want to see how we can exploit this moment.

Fourth, because there is so much good work — and there are so many good events (I spent about eight weeks of weekends attending emergency fake news conferences) — we at the Tow-Knight Center wanted to offer to convene the many groups attacking this problem so we could help everyone share information, avoid duplication, and collaborate. We don’t want to compete with any of them, only to help them. At Tow-Knight, under the leadership of GM Hal Straus, we have made the support of professional communities of practice — so far around product development, audience development and membership, commerce, and internationalization — key to our work; we want to bring those resources to the fake news fight.

My dean and partner in crime, Sarah Bartlett, and I formulated a proposal for Craig. He quickly and generously approved it with a four-year grant.

And then my phone rang. Or rather, I got a Facebook message from the ever-impressive Áine Kerr, who manages journalism partnerships there. Facebook had recently begun working with fact-checking agencies to flag suspect content; it started its Journalism Project; and it held a series of meetings with news organizations to share what it is doing to improve the lot of news on the platform.

Áine said Facebook was looking to do much more in collaboration with others and that led to a grant to fund research, projects, and convenings under the auspices of what Craig had begun.

Soon, more funders joined: John Borthwick of Betaworks has been a supporter of our work since we collaborated on a call to cooperate against fake news. Mozilla agreed to collaborate on projects. Darren Walker at the Ford Foundation generously offered his support, as did the two funders of the center I direct, the Knight and Tow foundations. Brian O’Kelley, founder of AppNexus, and the Democracy Fund joined as well. More than a dozen additional organizations — all listed in the release — said they would participate as well. We plan to work with many more organizations as advisers, funders, and grantees.

Now let me get right to the questions I know you’re ready to tweet my way, particularly about one funder: Have I sold out to Facebook? Well, in the end, you will be the judge of that. For a few years now, I have been working hard to try to build bridges between the publishers and the platforms and I’ve had the audacity to tell both Facebook and Google what I think they should do for journalism. So when Facebook knocks on the door and says they want to help journalism, who am I to say I won’t help them help us? When Google started its Digital News Initiative in Europe, I similarly embraced the effort and I have been impressed at the impact it has had on building a productive relationship between Google and publishers.

Sarah and I worked hard in negotiations to assure CUNY’s and our independence. Facebook — and the other funders and participants present and future — are collaborators in this effort. But we designed the governance to assure that neither Facebook nor any other funder would have direct control over grants and to make sure that we would not be put in a position of doing anything we did not want to do. Note also that I am personally receiving no funds from Facebook, just as I’ve never been paid by Google (though I have had travel expenses reimbursed). We hope to also work with multiple platforms in the future; discussions are ongoing. I will continue to criticize and defend them as deserved.

My greatest hope is that this Initiative will provide the opportunity to work with Facebook and other platforms on reimagining news, on supporting innovation, on sharing data to study the public conversation, and on supporting news literacy broadly defined.

The work has already begun. A week and a half ago, we convened a meeting of high-level journalists and representatives from platforms (both Facebook and Google), ad agencies, brands, ad networks, ad tech, PR, politics, researchers, and foundations for a Chatham-House-rule discussion about propaganda and fraud (née “fake news”). We looked at research that needs to be done and at public education that could help.

The meeting ended with a tangible plan. We will investigate gathering and sharing many sets of signals about both quality and suspicion that publishers, platforms, ad networks, ad agencies, and brands can use — according to their own formulae — to decide not just what sites to avoid but better yet what journalism to support. That’s the flight to quality I have been hoping to see. I would like us to support this work as a first task of our new Initiative.

We will fund research. I want to start by learning what we already know about the public conversation: what people share, what motivates them to share it, what can have an impact on informing the conversation, and so on. We will reach out to the many researchers working in this field — danah boyd (read her latest!) of Data & Society, Zeynep Tufekci of UNC, Claire Wardle of First Draft, Duncan Watts and David Rothschild of Microsoft Research, Kate Starbird (who just published an eye-opening paper on alternative narratives of news) of the University of Washington, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen of the Reuters Institute, Charlie Beckett of POLIS-LSE, and others. I would like us to examine what it means to be informed so we can judge the effectiveness of our — indeed, of journalism’s — work.

We will fund projects that bring journalism to the public and the conversation in new ways.

We will examine new ways to achieve news literacy, broadly defined, and investigate the roots of trust and mistrust in news.

And we will help convene meetings to look at solutions — no more whining about “fake news,” please.

We will work with organizations around the world; you can see a sampling of them in the release and we hope to work with many more: projects, universities, companies, and, of course, newsrooms everywhere.

We plan to be very focused on a few areas where we can have a measurable impact. That said, I hope we also pursue the high ambition to reinvent journalism for this new age.

But we’re not quite ready. This has all happened very quickly. We are about to start a search for a manager to run this effort with a small staff to help with information sharing and events. As soon as we begin to identify key areas, we will invite proposals. Watch this space.

The post Real News appeared first on BuzzMachine.

March 22, 2017

Quality over crap

We keep looking at the problems of fake news and crap content — and the advertising that feeds them — through the wrong end of the periscope, staring down into the depths in search of sludge when we could be looking up, gathering quality.

There is a big business opportunity to be had right now in setting definitions and standards for and creating premium networks of quality.

In the last week, the Guardian, ad agency Havas, the UK government, the BBC, and now AT&T pulled their advertising from Google and YouTube, complaining about placement next to garbage: racist, terrorist, fake, and otherwise “inappropriate” and “offensive” content. Google was summoned to meet UK ministers under the threat they’ll exercise their European regulatory reflex.

Google responded quickly, promising to raise its standards regarding “hateful, offensive and derogatory content” and giving advertisers greater control over excluding specific sites.

Well, good. But this seems like a classic case of boiling the (polluted) ocean: taking the entire inventory of ad availabilities and trying to eliminate the bad ones. We’re doing the same thing with fake news: taking the entire corpus of content online and trying to warn people away from the crap.

So now turn this around.

The better, easier opportunity is to create premium networks built on quality: Not “we’ll put your ad anywhere except in that sewer we stumbled over” but instead “we found good sites we guarantee you’ll be proud to advertise on.”

Of course, this is how advertising used to work. Media brands produced quality products and sold ads there. Media departments at ad agencies chose where to put clients’ ads based on a number of factors — reach, demographic target, cost, and quality environment.

The net ruined this lovely, closed system by replacing media scarcity with online abundance. Google made it better — or worse, depending on your end of the periscope — by charging on performance and thus sharing risk with the advertisers and establishing the new metric for value: the click. AppNexus and other programmatic networks made it yet better/worse by creating huge and highly competitive marketplaces for advertising inventory, married with data about individual users, which commoditized media adjacency. Thus the advertiser wants to sell boots to you because you once looked at boots on Amazon and it doesn’t much matter where those boots follow you — even to shite like Breitbart…until Sleeping Giants comes along and shames the brand for being there.

So why not sell quality? Could happen. There are just a few matters standing in the way:

First, advertisers need to value quality. There has been much attention paid to assuring marketers that their ads are visible to the user and that they are clicked on by a human, not a bot. But what about the quality of the environment and its impact on the brand? In our recent research at CUNY’s Tow-Knight Center, we found that brands rub off both ways: users judge both media and brands by the company they keep. This is why it is to the Guardian’s benefit to take a stand against crappy ad adjacencies with Google — because The Guardian sells quality. But will advertisers buy quality?

Second, there’s the question of who defines and determines quality. Over the years, I have seen no end of attempts to automate the answer to this question, whether by determining trust in news or quality in media. Impossible. There is no God signal of trust or virtue. The decision in the end is a human one and human decisions cost money. Besides, there is no one-size-fits-all definition and measurement of quality; that should vary by media brand and advertiser and audience. Still, the responsibility for determining quality has to fall somewhere and this is a hot potato nobody — brands, agencies, networks, platforms — wants because it is an expensive task.

Third, there’s the matter of price. Media companies, ad agencies, and ad networks will need to convince advertisers of the value of quality and the wisdom of paying for it, returning to an ad market built on a new scarcity. With fewer avails in a quality market — plus the cost of monitoring and assuring quality — the price will rise. Will advertisers give a damn if they can still sell stuff on shitty but cheap sites? Will the cost of being humiliated for appearing on Breitbart be worth the premium of avoiding that? On the other hand, will the cost of being boycotted by Breitbart when the advertiser pulls ads there be worth the price? This is a business decision.

I always tell my entrepreneurial students that when they see a problem, they should look for the solution, as an engineer would, or the opportunity, as an entrepreneur would. There are many opportunities here: to create premium networks of quality and trustworthy news and content; to create mechanisms to judge and stand by quality; to audit quality … and, yes, to create quality.

Our opportunity is not so much to kill bad content and bad advertising placements and to teach people to avoid all that bad stuff but to return to the reason we all got into these businesses: to make good stuff.

The post Quality over crap appeared first on BuzzMachine.

February 19, 2017

Trump & the Press: A Murder-Suicide Pact

The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 17, 2017

The press will destroy Trump and Trump will destroy the press.

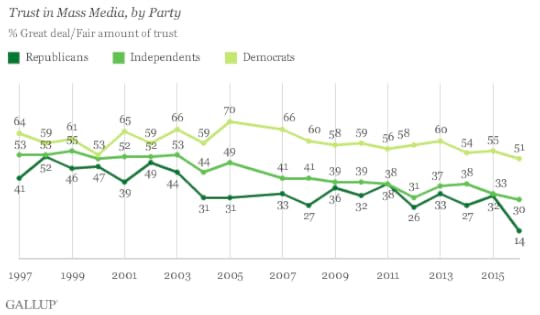

Consider that trust in media began falling in the ’70s, coincident with what we believe was our zenith: Watergate. We brought down a President. A Republican President.

Now the press is the nation’s last, best hope to bring down a compromised, corrupt, bigoted, narcissistic, likely insane, incompetent, and possibly dangerous President. A Republican President. Donald Trump.

If the press does what Congress is so far unwilling to do — investigate him — then these two Republican presidencies will bookend the beginning of the end and the end of the end of American mass media. Any last, small hope that anyone on the right would ever again trust, listen to, and be informed by the press will disappear. It doesn’t matter if we are correct or righteous. We won’t be heard. Mass media dies, as does the notion of the mass.

Therein lies the final Trump paradox: In failing, he would succeed in killing the press. And his final projection: The enemy of the people convinces the people that we are the enemy.

The press that survives, the liberal press, will end up with more prizes and subscriptions, oh joy, but with little hope of guiding or informing the nation’s conversation. Say The New York Times reaches its audacious dreamof 10 million paying subscribers. So what? That’s 3% of the U.S. population (and some number of those subscribers will be from elsewhere). And they said that blogs were echo chambers. We in liberal media will be speaking to ourselves — or, being liberal, more likely arguing with ourselves.

No number of empathetic articles that try to understand and reflect the worldview of the angry core of America will do a damned bit of good getting them to read, trust, and learn from The New York Times. My own dear parents will not read The New York Times. They are left to be informed by Fox News, Breitbart, Drudge, RT, and worse.

Last week, Jim Rutenberg and David Leonhardt of The Times wrote tough columns about turmoil in Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal over journalists’ fears that they find themselves working for an agent of Trump. They missed the longer story: What we are living through right now was the brainchild of Rupert Murdoch. It started in 1976 (note the timeline of trust above) when he bought the New York Post to be, in his words, his bully pulpit — and he added new meaning to that phrase. Yes, Rush Limbaugh and his like came along in the next decade to turn American radio into a vehicle for spreading fear, hate, and conspiracy. But it was in the following decade, in 1996, when Murdoch started Fox News, adding new, ironic meaning to another phrase: “fair and balanced.” He and his henchman, Roger Ailes, used every technique, conceit, and cliché of American television news to co-opt the form and forward his worldview, agenda, and war.

Murdoch could have resurrected the ideological diversity that was lost in the American press when broadcast TV culled newspapers in competitive markets and the survivors took on the impossible veil of objectivity. Instead, he made the rest of the press into the enemy: not us “and” them but us “or” them; not “let us give you another perspective” but “their perspective is bad.”