Jeff Jarvis's Blog, page 13

February 10, 2019

Scorched Earth

I just gave a talk in Germany where a prominent editor charged me with being a doomsayer. No, I said, I’m an optimist … in the long run. In the meantime, we in media will see doom and death until we are brutally honest with ourselves about what is not working and cannot ever work again. Then we can begin to build anew and grow again. Then we will have cause for optimism.

Late last year in New York, I spoke with a talented journalist laid off from a digital news enterprise. She warned that there would be more blood on the streets and she was right: In January, more than 2,000 people have lost their jobs at news companies old and now new: Gannett, McClatchy, BuzzFeed, Vice, Verizon. She warned that we are still fooling ourselves about broken models and until we come to terms with that, more blood will flow.

So let us be blunt about what is doomed:

Advertising in its current forms is burning out — perhaps even for the lucky ones who still have it.Paywalls will not work for more than a few — and their builders often do not account for the real motives of people who pay and who don’t.There is not enough philanthropy from the rich — or charity from the rest of us — to pay for what is needed.Government support — whether financial or regulatory — is a dangerous folly.

There are no messiahs. There are no devils to blame, either.

Google and Facebook did not rob the news industry; they only took up the opportunity we were blind to. Our fate is not their fault. Taking them to the woodshed will produce little but schadenfreude.VCs, private equity, and the public markets are not to blame; like lions killing antelope and vultures eating the rest, they are doing only what nature commanded.

Are we to blame for our own destruction? I confess I used to think that was somewhat true — for the optimist in me believed there had to be something we could do to find opportunity in all this disruption, to rebuild an old industry in a new image, and if we didn’t we were at fault for the result. But perhaps we simply could not see the fallacies in our operating assumptions:

Information is a commodity.Content is a commodity.In an age of abundance, commodities are losing businesses.Nobody owes us a damned thing: not technologists, not financiers, not philanthropists, not advertisers, not the public, and certainly not government. Instead, we are in debt to many of them and can’t pay it back.

Maybe there is nothing we could have done to save businesses built on now-outmoded models. Maybe nobody is to blame. Reality sucks until it doesn’t.

I believe we can and must build new models for journalism based on real value, understanding people’s needs and motives so we can serve them. But I’m getting ahead of myself again. I can’t help it: I’m an optimist. Before we can build the new, we must recognize what is past. Only then can we rise from the ashes. That process — when it begins — will not be easy or short. As I am fond of telling anyone who will listen, I believe we are at the start of a long, slow evolution, akin to the start of the Gutenberg Age, as we enter a new and still-unknown age. It’s only 1475 in Gutenberg years. There might be a few peasants’ wars, a Thirty Years War, and a Reformation between us and a Renaissance ahead. No guarantees that there’ll be a Renaissance, either. But there’ll definitely be no resurrection of what was.

Recently, Ben Thompson and Jeremy Littau shared cogent analyses of how we got in this hole. I want to examine why merely adjusting those same strategies will not get us out of it. I want to shift our gaze from the ashes below to a north star above — to optimism about the future — but I don’t think we can do that until we are honest about our present. So let’s examine each of the bullets (to our heads) above.

ADVERTISING IS BURNING OUT.

Mass marketing — that is, volume-based advertising — killed quality and injured trust in media because, as abundance grew and prices fell and desperation rose, every movement and metric was reduced to a click and inevitably a cat and a Kardashian. Programmatic advertising commodifies everything it touches: content, media, consumers, data, and even the products it sells. Personalization via retargeting — those ads that follow you everywhere — is insulting and stupid. (Hey, Amazon: why do you keep advertising things to me you know I bought?)

Advertising ultimately exists to fool people into thinking they want something they hadn’t thought they wanted. Thus every new form of advertising inevitably burns out when customers catch on, when the jig is up. That’s why advertisers always want something new. Clicks at volume worked for Business Insider, Upworthy, and many like them until it no longer did. Native advertising worked for Quartz — which, I think, did the best and least fraudulent job implementing it — until it no longer paid all the bills. So-called influencer marketing sort-of worked until customers learned that even their friends can’t be trusted. Axios is proud that it is breaking even on corporate responsibility advertising —which will work until people remember that some evil empires are all still evil. Facing advertising’s limits, each of these companies is resorting to a paywall. We’ll discuss how well that will work in a minute.

Many years ago — at the start of all this — I said that by definition, advertising is failure. Every maker and every marketer wants to be loved, its products bought because its customers are already sold or because its customers sell its products with honest recommendations. When that doesn’t work, you advertise. The net puts seller and buyer into direct contact and advertisers will explore every possible way to avoid advertising.

Amazon finds another path by exploiting others’ cost structures — manufacturers, marketers, distributors — to arrive at pure sales. Then Amazon can eliminate all those middlemen by making products that require neither brand nor advertising, recommending them to customers based on their behavior and intent (and robots will eventually take care of distribution).

If advertising and brands are diminished, even Google and Facebook may suffer and fall because arbitraging data to intuit intent — like every other advertising business model so far — might be short-lived. I think the definition of “short” might be decades, and so I’m not ready to short their stock (disclosure: I own Google’s). I also expect no end of glee at their pain. My point: The platforms are not invincible.

I think that BuzzFeed was onto something before it pivoted to pivoting. It didn’t sell audience per se but instead sold expertise: We know how to make our shit viral and we can make your shit viral. If we in journalism have any hope of holding onto any scraps of advertising that still exist, I believe we need to think similarly and understand the expertise we could bring to others. I like to think that could be understanding how to serve communities. But first we have to learn how to do that.

The bottom line: Because it enables anyone to speak as an individual, the net kills the idea of the faceless mass and with it mass media and mass marketing and possibly mass manufacturing. It’s over, people. The mass was a myth and the net exposed that.

PAYWALLS WILL NOT WORK FOR MORE THAN A FEW

Not long ago, every time I encountered a paywall for an article I wanted to read, I recorded the annual cost. I stopped after two weeks when the total hit $3,650. NFW. Oh, I know: I’ve been Twitter-scolded along with the rest of the cheap-bastard masses for not comparing the intrinsic, moral worth of a news think piece to a latte. What entitlement it takes for journalists to lecture people on how they spend their own hard-earned money. Scolding is no business strategy.

Yes, at least for some years, some media properties will make money by charging readers for access to content — until the idea of “content” disappears (more on that in a minute) along with the concept of the “mass” and the industry called “advertising.” But let’s be honest about a few things:

Consumer willingness to pay for content is a scarcity and we’ve already likely hit its limits. A recent Reuters Institute study said more than half of surveyed executives vowed paywalls would be their main focus for 2019. The line on the other side of the cash register is going to get mighty crowded.Much of the content behind many of the paywalls out there is not worth the price charged.Most of the information in that content is duplicative of what exists elsewhere for less or free.

Paywalls are an attempt to create a false scarcity in an age of abundance. They will work for the few that sell speed (see Bloomberg v. Reuters and also Michael Lewis’ Flash Boys — though time is a diminishing asset) or unique value (which inevitably means a limited audience of people who can make money on that value) or loyalty and quality (yes, the strategy is working wellfor The New York Times because it is the fucking New York Times — and you’re not).

The mistake that many paywallers make is that they don’t understand what might motivate people to pay. I pay for The Washington Post because I think it is the best newspaper in America and because Jeff Bezos gave me a great price. Personally, I pay for the New York Times and The Guardian out of patronage but only one of them is clever enough to realize that (more on that in a minute). You might be paying for social capital or access to journalists or to other members of a community or out of social responsibility. The product, the offering, and the marketing all need to take into account your motive.

The economics of subscriptions and paywalls are never discussed in full. I learned from my first day in the magazine business that you have to spend money in marketing to earn money in subscriptions. I’ve been privy to the subscriber acquisition cost of some news organizations and it is staggering. Yes, some of the fees news orgs are charging are high but the subscriber acquisition cost can be two or three times the cost to the consumer or more. And churn rates are higher than most will admit.

I do think we need to explore more sources of revenue from consumers. At Newmark’s Tow-Knight Center, we have brought together media companies trying commerce. Some companies are selling their own ancillary products — everything from books to wine to cooktops to gravity blankets. High-end media companies are surprised at how much people will spend through them on travel. The Telegraph is making financial services and sports betting a priority. Texas Tribune and others find success in events. I’m in favor of trying all these paths to consumer revenue but each one brings the need for expertise, resources, and risk. As for micropayments: dream on.

Those abandoning advertising — or rather, those abandoned by advertising — often argue for the moral superiority of paywalls. But every revenue source brings moral hazards to beware of, as Jay Rosen explores regarding dependence on readers. In the end, the arguments in favor of paywalls are often fatally tautological: They must be working because everyone is building them. Good luck with that.

There is not enough philanthropy from the rich — or charity from the rest of us

The Reuters Institute survey found that a third of executives expected more largesse from foundations this year. Well, last year, Harvard and Northeastern published a study of foundation support of journalism, tolling up $1.8 billion in grants over six years. Not counting support for education (but thanking those who give it), I calculate that comes to less than $200 million a year. For the sake of comparison, The New York Times’ costs add up to almost $1.5 billion. The grants are a drop in the empty bucket. Foundations can be wonderful but they cannot support all the efforts that think they are worthy. They also tend to have ADD, wanting to support the next new thing. They are not our salvation.

How about wealthy individuals? Depends on the wealthy individual. G’bless Jeff Bezos for bringing innovation to The Washington Post and giving Marty Baron the freedom to excel. It’s nice that Marc Benioff bought Time, though I’m not sure why he did and whether that was the best investment in journalism. Pierre Omidyar is funding ideologically diverse efforts from The Intercept to The Bulwark; good for him. Good for all that. But there are also many bad billionaires. Sugar daddies are not our salvation.

Then what about charity — patronage — from the public? I have been a proponent of membership over paywalls, of creating services that serve the affinities of people and communities. Jay Rosen’s Membership Puzzle Project is helping De Correspondent bring its lessons to the U.S. and key among them is that people give money not for access to content but to support the work of a journalist. I advocated a membership strategy for The Guardian but when its readers said they didn’t want a paywall because they wanted to support The Guardian’s journalism for the good of society, it became evident that the relationship was actually charity or contribution. And it works. The Guardian will finally break even thanks to the generosity of its readers. Is this for everyone? No, because everyone is not The Guardian. I give to The Guardian. I consider my payments to The New York Times patronage. I give to Talking Points Memo simply because I want to support its work. But just as with subscriptions, there is a finite pool of generosity. Charity won’t save us.

Government support — whether financial or regulatory — is a dangerous folly

I could go on and on about the lessons learned from regulatory protectionism in Europe but I won’t because I already did.

Should government support journalism in the U.S.? I have a two-word response to that.

Enough said.

So now onto the devils who get the blame for ruining news. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, whom I greatly admire and often agree with, identifies what she says are the biggest threats to journalism.

Gonna keep it

January 27, 2019

Journalism is the conversation. The conversation is journalism.

An illustration of Edward Lloyd’s coffee house, which served as a headquarters for marine underwriters. The business eventually evolved into Lloyd’s of London insurance company.

An illustration of Edward Lloyd’s coffee house, which served as a headquarters for marine underwriters. The business eventually evolved into Lloyd’s of London insurance company.I am sorely disappointed in The New York Times’ Farhad Manjoo, CNN’s Brian Stelter, and other journalists who these days are announcing to the world, using the powerful platforms they have, that they think journalists should “disengage” from the platform for everyone else, Twitter.

No. It is the sacred duty of journalists to listen to the public they serve. It is then their duty to bring journalistic value — reporting, facts, explanation, context, education, connections, understanding, empathy, action, options— to the public conversation. Journalism is that conversation. Democracy is that conversation.

In a moment, I will quote from the late James Carey’s eloquent lessons on the primacy of the conversation in journalism. But first I want to observe, as I’ve written before, that these journalists’ pronouncements come from a position of extreme privilege. Manjoo has a column, Stelter a show where they can expose their worries to the world. If you are an African-American who is shopping or barbecuing or eating lunch or going into your own home when a white person calls the police on you, you do not have a newsroom of journalists who look like you who will tell your story because they, too, have lived it. The outlet you have is a hashtag on Twitter. These stories are now, finally, making it into mainstream media only because #livingwhileblack exists as a tool for those forever unrepresented and unserved by mass media.When journalists delete, dismiss, or disengage from Twitter or Facebook or YouTube or Instagram or Reddit or blogs, they turn their backs on the people who finally — like the journalists — have a printing press to call their own. For too long — since Habermas’ alleged birth of the public sphere in the coffee houses and salons of London and Paris — that sphere has excluded too many people, whom social media finally can include. Listen to them.

In fairness to Manjoo, he does not suggest killing Twitter entirely. “Instead, post less, lurk more,” he advises. No. Two problems with that: It means that journalists continue to rob and exploit the stories of people for their articles without giving them the respect of conversation and collaboration. And it means that journalists are not doing what they can to bring journalism to the public conversation where it occurs — which they can finally do, thanks to the internet. I learned this at Vidcon: In some cases, we need to remake news as social tokens packed with fact and context that people can share in their own conversations. The public conversation is indeed in need of help. We cannot help that conversation by disengaging from it.

Manjoo also suggests, rightly, that journalists get their acts together and not be jerks and bozos online. Who can argue with that? But to be clear, that is entirely up to journalists — and everyone on Twitter. I do not subscribe to the technological determinism and moral panic that blames the tool. “Twitter is ruining American journalism,” says Manjoo. No, journalists are responsible for the state of American journalism. They have no one to blame but themselves when they jump on a story too soon with unconfirmed information and rash conclusions, when they insist on joining in with their own needless and repetitive hot takes, when they match snark for snark.When I’m a jerk on Twitter it’s because I’m being a jerk, not because Twitter made me on. “Everything about Twitter’s interface encourages a mind-set antithetical to journalistic inquiry,” Manjoo argues. “It prizes image over substance and cheap dunks over reasoned debate, all the while severely abridging the temporal scope of the press.” No, I find plenty of very smart people on Twitter who share information and perspective and wisdom. If you haven’t found them, you haven’t tried hard enough; you haven’t done your reporting. A poor craftsman blames his Twitter.

In the discussion about this over the last week or so, I’ve seen people responding to my arguments by saying that Twitter is not representative of the population. Well, neither is The New York Times. I’ve seen them complain that Twitter has assholes. Well, so does the world; don’t follow them. And I’ve seen them say that Twitter is too small to bother with. That is an outmoded, mass-media worldview — inspired by the commercial demands of advertisers — that values and recognizes only scale. Stop thinking of people as masses; start recognizing them as individuals and members of communities and you will begin to appreciate the people you can meet, hear, and learn from on Twitter and Facebook and YouTube and in tools not yet imagined, tools that connect people (which is the value of the net) rather than merely manufacture content (which is the value of old, dying, mass media).

Now I’d like to call class to order and invite the spirit of the too-soon-departed Columbia professor, James Carey from his essay, “A Republic, If You Can Keep It”: Liberty and Public Life in the Age of Glasnost. (Sadly, that link is behind a paywall. I heartily recommend the book James Carey: A Critical Reader,especially including Jay Rosen’s introduction to this essay.) Here Carey teaches us about the true nature of journalism and democracy.

But I believe we must begin from the primacy of conversation. It implies social arrangements less hierarchical and more egalitarian than its alternatives. While people often dry up and shy away from the fierceness of argument, disputation, and debate, and while those forms of talk often bring to the surface the meanness and aggressiveness that is our second nature, conversation implies the most natural and unforced, unthreatening, and most satisfying of arrangements.

A press that encourages the conversation of [the public’s] culture is the equivalent of an extended town meeting. However, if the press sees its role as limited to informing whoever happens to turn up at the end of the communication channel, it explicitly abandons its role as an agency for carrying on the conversation of the culture.

That is to say, if the press serves only those who come to its destinations and pay to get past its paywalls then it is serving only a tiny elite. Talk about echo chambers, that is an echo chamber.

Carey continues even more sternly:

A press independent of the conversation of culture, or existing in the absence of such a conversation, is likely to be, in practical terms, whatever the value of the right the press represents, a menace to public life and an effective politics. The idea of the press as a mass medium, independent of, disarticulated from, the conversation of the culture, inherently contradicts the goal of creating an active remembering public. Public memory can be recorded by but cannot be transmitted through the press as an institution. The First Amendment, to repeat, constitutes us as a society of conversationalists, of people who talk to one another, who resolve disputes with one another through talk. This is the foundation of the public realm, the inner meaning of the First Amendment, and the example the people of Eastern Europe were quite inadvertently trying to teach us. The “public” is the God term of the press, the term without which the press does not make any sense. Insofar as the press is grounded, it is grounded in the public. The press justifies itself in the name of the public. It exists, or so it is said, to inform the public, to serve as the extended eyes and ears of the public. The press is the guardian of the public interest and protects the public’s right to know. The canons of the press originate in and flow from the relationship of the press to the public.

This is about respecting more than journalism. It is about maintaining democracy:

Republics require conversation, often cacophonous conversation, for they should be noisy places. That conversation has to be informed, of course, and the press has a role in supplying that information. But the kind of information required can be generated only by public conversation; there is simply no substitute for it. We have virtually no idea what it is we need to know until we start talking to someone.Conversation focuses our attention, it engages us, and in the wake of conversation we have need not only of the press but also of the library. From this view of the First Amendment, the task of the press is to encourage the conversation of the culture — not to preempt it or substitute for it or supply it with information as a seer from afar. Rather, the press maintains and enhances the conversation of the culture, becomes one voice in that conversation, amplifies the conversation outward, and helps it along by bringing forward the information that the conversation itself demands.

We say we in the press are guardians of the First Amendment as we are guarded by it. Carey tells us what the First Amendment really means:

We value, or so we say, the First Amendment because it contributes, in Thomas Emerson’s formulation, four things to our common life. It is a method of assuring our own self-fulfillment; it is a means of attaining the truth; it is a method of securing participation of members of society in political decision making; and it is a means of maintaining a balance between stability and change.

This is why I value social media and how it gives us the ability to hear people too long not heard. This is why I started a degree in Social Journalism at the Newmark J-School, where my colleague Carrie Brown and our students constantly explore new definitions, new obligations, and new opportunities for journalism that the net enables. This is why I so admire Spaceship Media, a journalistic startup that embodies my revised definition and mission of journalism: to convene communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation. This is why I argue for a post-content, relationship-based strategy for the future of journalism. It starts with listening.

Manjoo ends declaring: “Twitter will ruin us, and we should stop.” No, that attitude of snobbery and willful ignorance of the world around us and moral panic about technology is what will la-la-la the news business into oblivion.

But don’t listen to me. Go to Twitter and Facebook and elsewhere and find new people you don’t know who experience things you don’t experience who have perspectives you don’t have and listen to them. That is journalism.

Carey concludes:

We must turn to the task of creating a public realm in which a free people can assemble, speak their minds, and then write or tape or otherwise record the extended conversation so that others, out of sight, might see it. If the established press wants to aid the process, so much the better. But if, in love with profits and tied to corporate interests, the press decides to sit out public life, we shall simply have to create a space for citizens and patriots by ourselves.

He wrote that in 1991, 15 years before Twitter was created because the press didn’t create it and someone else had to.

The post Journalism is the conversation. The conversation is journalism. appeared first on BuzzMachine.

January 20, 2019

We Have Met the Problem. Guess Who?

Here is chapter I contributed to the Hackademic 2018 book, Anti-Social Media?: The Impact on Journalism and Society. I’ve used various ideas in this in other posts recently. I’m leaving the British spelling because it just might make me seem smarter.

In all the urgent debate about regulating, investigating, and even breaking up internet companies, we have lost sight of the problem we are trying to confront: not technology but instead human behaviour on it, the bad acts of some (small) number of fraudsters, propagandists, bigots, misogynists, and jerks.

Computers do not threaten and harass people; people do. Hate speech is not created by algorithms but by humans. Technology did not interfere with the American election; another government did.* Yet we demand that technology companies cure what ails us as if technology were the disease.

When before have we required corporations to monitor and mediate human behaviour? Isn’t that the job — the very definition — of government: to define and enforce the limits of acceptable acts? If not government, then won’t parents, schools, clergy, therapists, or society as a whole — in its process of negotiating norms — fill the role? But all that takes time. In the face of the speed and scale of the invention and dissemination not only of technology but of its manipulation, government has no idea what to do. So in their search for someone to blame, government outsource fault and responsibility, egged on by media (whose schadenfreude constitutes a conflict of interest, as publishers wish to witness their new competitors’ comeuppance).

Why would we ever expect or want corporations to doctor us? Indeed, isn’t manipulation of our speech and psyches by technologists what critics fear most? Some argue this is the platforms’ problem because it’s the platforms that screwed us up. I disagree. It’s not as if before the net the world was a choir of angels. To argue that the internet addicts the connected masses, makes them stupid, turns them into trolls, and transforms them into agents of society’s ruin is elitist and fundamentally insulting, denying people their agency, their intelligence, their goodwill or lack thereof. The internet is not ruining humankind. Humankind is still trying to figure out what the internet can and should be.

It is true that internet technology has provided bad actors with new means of manipulation and exploitation in the pursuit of money and lately political gain or demented psychology. It’s also true that the technologists were too optimistic and naive about how their powerful tools could be misused — or rather, used but for bad ends. I agree that Facebook, Google, Twitter, and company must exercise more responsibility in anticipating and forestalling manipulation, in understanding the impact they have, in being transparent about that impact, and in collaborating with others to do better. There’s no doubt that the culture of Silicon Valley is too isolated and hubristic and must learn to listen, to value and empower diversity, to move fast but think first. Do I absolve them of responsibility? No. Do I want them to do more? Yes.

The terms of the conversation

But what precisely do we expect of them? For a project underwritten by the How Institute for Society, founded by Dov Seidman, I interviewed and convened discussions with people I respect as leaders, visionaries, and responsible voices in journalism, technology, law, and ethics. What struck me is that I heard no consensus on the definition of the problems to be solved, let alone the solutions. There is general head-shaking and tsk-tsking about the state of the internet and the platforms that now operate much of it. But dig deeper in search of an answer and you’ll find yourself in a maze.

At Google’s 2018 European journalism unconference, Newsgeist, I proposed a session asking, “What could Facebook do for news?” Some journalists in the room argued that Facebook must eliminate bad content and some argued that Facebook must make no judgments about content, good or bad. Sometimes, they were the same people, not hearing themselves making opposing arguments.

In my interviews, Professor Jay Rosen of New York University told me that we do not yet have the terms for the discussion about what we expect technology companies to do. Where are the norms, laws, or regulations that precisely spell out their responsibility? Professor Emily Bell of the Columbia School of Journalism said that capitalism and free speech are proving to be a toxic combination. Data scientist Deb Roy of the MIT Media Lab said capitalistic enterprises are finely tuned for simple outcomes and so he doesn’t believe a platform designed for one result can be fixed to produce another, but he hopes innovators will find new opportunities there. Technologist Yonatan Zunger, formerly of Google, argued that computer scientists must follow the example of engineering forebears — e.g., civil engineers — to recognise and account for the risks their work can bring. Entrepreneur John Borthwick, founder of Betaworks, proposed self-regulation to forestall government regulation. Seidman the ethicist insisted that neutrality is no longer an option and that technology companies must provide moral leadership. And philosopher David Weinberger argued that we are past trying to govern according to principles as society is so divided it cannot agree on those principles. I saw Weinberger proven right in the discussion at Newsgeist, in panels I convened at theInternational Journalism Festival, and in media. As Rosen says, we cannot agree on where to start the conversation.

The limits of openness

In the web’s early days, I was as much a dogmatist for openness as I am for the First Amendment. But I have come to learn — as the platforms have — that complete openness invites manipulation and breeds trolls. Google, Facebook, and Twitter — like news media themselves — argue that they are merely mirrors to society, reflecting the world’s ills. Technology’s and media’s mirrors may indeed be straight and true. But society warps and cracks itself to exploit these platforms. The difference between yesterday’s manipulation via media (PR and propaganda) and today’s via technology (from trolls to terrorists) is scale; the internet allows everyone who is connected to speak — which I take as a good — but that also means that anyone can become a thief, a propagandist, or a tormentor at a much lower cost and with greater access than mass media permitted. The platforms have no choice but to understand, measure, reveal, and compensate for that manipulation. They are beginning to do that.

Good can come of this crisis, trumped up or not. I now see the potential for a flight to quality on the net. After the 2016 elections and the rising furore about the role of the platforms in nations’ nervous breakdowns, Google’s head of search engineering, Ben Gomes, said that thenceforth the platform would account for the authority, reliability, and quality of sources in search ranking. In a search result for a query such as ‘Is climate change real?’ Google now sides with science. Twitter has recognised at last that it must account for its role in the health of the public conversation and so it sought help from researchers to define good discourse.

For its part, Facebook downgraded the prominence of what it broadly considered public (as opposed to social) content, which included news. Now it is trying to bring back and promote quality news. At The Newmark J-Schools Tow-Knight Center at CUNY, I am working on a project to aggregate signals of quality (or lack thereof) from the many disparate efforts, from the Trust Project to the Credibility Coalition and . We will provide this data to both platforms and advertisers to inform their decisions about ranking and buying so they may stop supporting disinformation and instead support quality news. [Disclosure: This work and that of the News Integrity Initiative, which I started at CUNY, are funded in part by Facebook but operate with full independence and I receive no compensation from any platform.]

Are these acts of self-regulation by the platforms sufficient? Of course, not. But I argue we must view this change in temporal context: We are only 24 years past the introduction of the commercial web. If the net turns out to be as disruptive as movable type, then in Gutenberg terms that puts us in the year 1474, years before Luther’s birth and print-sparked revolution, decades before the book took on the post-scribe structure we know now, centuries before printing and steam technology combined to create the idea of the mass.

Causes for concern

We don’t know what the net is yet. That is why I worry about premature regulation of it. I fear we are operating today on vague impressions of problems rather than on journalistic and academic evidence of the scale of the problems and the harm they are causing. I challenge you to look at your Facebook feed and show me the infestation of nazis there. Where is the data regarding real harm?

I worry, too, about the unintended consequences of well-intentioned regulation. In Europe, government moves aimed at challenging the power of the platforms have ended up giving them yet more power. The so-called right to be forgotten has put Google in the uneasy position of rewriting and erasing history, a perilous authority to hold. Germany’s Leistungsschutzrecht (ancillary copyright) gave Google the power to set the terms of the market in links to news. Spain’s more aggressive link tax led to the exit of Google News from the country. I shudder to think what a pending EU-wide version of each law will do. Germany’s hate-speech law, the Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz or NetzDG law, is all but killing satire there and requires the devotion of resources to killing crap, not rewarding quality. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will leave Google and Facebook relatively unscathed — as they have the resources to deal with its complex requirements — but some American publishers have cut off European readers, balkanising the web. Anticipated ePrivacy regulation will go even farther and I fear an extreme privacy regime will obstruct a key strategy for sustaining journalism — providing greater relevance and value to people we know as individuals and members of communities and gaining new revenue through membership and contribution as a result. Thus this regulation could artificially extend the life of outmoded mass media and the paternalistic idea of the mass.

I worry mostly that we may be entering into a full-blown moral panic, with technology — internet platforms — as the enemy. Consider Ashley Crossman’s definition: “A moral panic is a widespread fear, most often an irrational one, that someone or something is a threat to the values, safety, and interests of a community or society at large. Typically, a moral panic is perpetuated by news media, fuelled by politicians, and often results in the passage of new laws or policies that target the source of the panic. In this way, moral panic can foster increased social control.” Sound familiar? To return to the lessons of Gutenberg’s age, let us recall that Erasmus feared what books would do to society. “To what corner of the world do they not fly, these swarms of new books?” he complained. “The very multitude of them is hurtful to scholarship, because it creates a glut and even in good things satiety is most harmful.” But we managed.

When I was invited to contribute this chapter, I was asked to write “in defence of Facebook.” With respect, that sets the conversation at the wrong level, at the institutional level: Journalism vs. Facebook. Thus we miss the trees for the forest, the people for the platforms. No matter what we in journalism think of Facebook, Google, or Twitter as companies, we must acknowledge that the public we serve is there and we need to take our journalism to them where they are. We must take advantage of the opportunity the net provides to see the public not as a mass but as a web of communities. We cannot do any of this alone and need to work with platforms to fulfill what I now see as journalism’s real job: to convene communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation. If society is a polarised world at war with itself — red vs. blue, white vs. black, insider vs. outsider, 99% vs. 1% — we perhaps should begin by asking how we in journalism led society there.

* I expect someone on Twitter to respond to this paragraph with a picture of the bumper sticker declaring that guns don’t kill people; people do. The sentence structures may be parallel but the logic is not. Guns are created for one purpose: to kill. The internet was created for purposes yet unknown. We are negotiating its proper and improper uses and until we do — as we are learning — the improper will out.

The post We Have Met the Problem. Guess Who? appeared first on BuzzMachine.

January 18, 2019

A Rising Moral Panic

This is just what I fear: fear itself. See that exchange above. Nick Thompson, the very impressive editor-in-chief of Wired, touted a column by one of his writers who idly wondered whether the #10YearChallenge meme could be a conspiracy created by Facebook to get us chumps to provide it with photos and data to enable facial recognition over time.

Just maybe. What if?

Except that’s ridiculous, on its face. At its public I/O developers conference more than three years ago, Google demonstrated that it could identify the same person in photos from infancy to elderly. And Facebook hardly needs two random photos from a smattering of people when it has huge stores of dated photos of people who identify themselves. (Disclosure: I raised money for my school from Facebook but we are fully independent and I receive no funds personally from any platform.)

I pointed out this logic on Twitter, and Nick — who, I want to emphasize again, has done wonders with Wired and made it better than it has been in years and who is often on the same, sane, calm side of the debate over #technopanic with me — immediately acknowledged in response that Facebook said it did not start the #10YearChallenge meme (reporting that, in my opinion, would have best been done before the column was posted). So, to quote the immortal Emily Litella:

Nonetheless, Nick’s original tweet to his 100k followers lives on and we know that people reach conclusions from a tweet or a headline without always reading on. Then today Keith Olbermann repeats this to his more than 1 million Twitter followers. What if? becomes WTF!! becomes OMG!!! A meme is born, a doubt is raised, paranoia is spawned. What’s my fear? Regulation will follow and the internet will suffer. See, as one of many examples, this tweet calling all regulators.

See also this presentation I gave to Munich Media Days on the unintended consequences of regulation. In a nutshell: Regulators and courts wanted to take power away from the platforms but ended up giving them more.

Germany’s ancillary copyright (Leistungsschutzrecht) was intended to make Google pay for snippets but gave Google greater negotiating power because publishers needed the eggs.With the stricter Spanish link tax, publishers cut off their nose to spite their face and Google cut off Google News and with it much traffic to them.The right to be forgotten court ruling gave Google the power of God (a power it did not want) to decide what should and should not be remembered and set a precedent Europe should beware of rewriting and erasing history.Germany’s NetzDG hate-speech law gives Facebook similar power and all but kills satire in Germany. (I provide the straight line, you provide the joke.)Europe’s sweeping privacy regulation, GDPR, did good things but also balkanized the news web with thousands of US publishers cutting off European readers and made expensive requirements that are burdens for small companies in Europe but are nothing to Google and Facebook, which could end up being even more competitive as a result.And now we have the the noxious new EU copyright law with Articles 11 and 13 threatening our ability to quote and share what was formerly known as content and now is known as conversation.

That is what I fear. The atmosphere created by paranoid memes such as the one I write about here — and it’s just one and one of the more minor of many examples — empowers media to raise alarms, which empowers politicians to pass more such legislation.

Am I opposed to all regulation? No, of course not. Every human activity on the internet is already subject to law and regulation and it’s human activity — lies, fraud, manipulation, hate, misogyny — that is causing us trouble today, not so much the underlying technology. It is too soon to say that we know what the internet is and what its impact will be and so it is too soon to define and limit and regulate it as if we can be sure of the consequences of our actions. We risk cutting off opportunities we cannot anticipate, especially from people who were never well-represented and served by the old power structures.

Thanks to research I’m doing lately, I just reread James Dewar’s prescient 1998 RAND paper, The Information Age and the Printing Press. Learning lessons from Gutenberg’s disruption, Dewar sees parallels to the disruption we face now. “The future of the information age will be dominated by unintended consequences,” he says. “It will be decades before we see the full effects of the information age.” I might argue that could be centuries. He concludes: “The above factors combine to argue for: a) keeping the Internet unregulated, and b) taking a much more experimental approach to information policy.” He cautions: “This is speculation of the highest order.”

I emailed Dr. Dewar and he said that two decades on he still thinks its too early to say what the internet’s impact is or even what the internet is. I agree. In his paper, Dewar warns: “Countries that failed to take advantage of the printing press fell behind Europe. Those that strictly suppressed the printing press … were eclipsed on the world stage. Even in Europe countries that tried to suppress ‘dangerous’ aspects of the printing press suffered. This strongly suggests that the advantages of the printing press outweighed the disadvantages. Further, it suggests that, in retrospect, it was more important to explore the upside of the technology than to protect against the downside.”

Scholars Elizabeth Eisenstein and Adrian Johns and many others have debated about the printing press and technological determinism and thus about its alleged impact. Six centuries from now scholars will feud about the same questions regarding our networked age. At this moment, we are arguing about that impact of the net on our daily lives. Some have said to me that this fuss about the #10YearChallenge meme is helpful because people are talking about the issues at hand.

I have one response: Let that debate be based on facts and evidence, not on baseless provocations and what-if worries, which fuel a moral panic that comes to blame all our troubles on technology and assume malign motive for every action the technologists take. Journalists do not have license to relax their standards of fact and evidence and should be informing the debate, not fueling the panic.

Just to show you how fearless I am, I went into Flickr to save my photos from ages past and found this one of me 10 years ago. I look like a dork. Now Facebook, Google, and every one of you knows that. And no one is surprised.

The post A Rising Moral Panic appeared first on BuzzMachine.

January 9, 2019

The kids are alright. Grandpa’s the problem.

NYU and Princeton professors just released an important study that took a set of fake news domains identified by BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman and others and asked who shares them on Facebook. They found that:

Sharing so-called fake news appears to be rare. “The vast majority of Facebook users in our data” —more than 90 %— “did not share any articles from fake news domains in 2016 at all.”

Most of the sharing is done by old people, not young people. People over 65 shared fake news at a rate seven times higher than young people 18–29. This factor held across controls for education, party affiliation and ideology, sex, race, or income.

It is also true that conservatives — and, interestingly, those calling themselves independent — shared most of the fake news (18.1% of Republicans vs. 3.5% of Democrats), though the researchers caution that the sample of fake news was predominantly pro-Trump.

Interestingly, people who share more on Facebook are less likely to share fake news than others, “consistent with the hypothesis that people who share many links are more familiar with what they are seeing and are able to distinguish fake news from real news.”

Compare this with accepted wisdom: That fake news is everywhere and that everyone on Facebook is sharing it. That Facebook users can’t tell fake from true. That young people are sharing this stuff and don’t understand how media work and thus are in need of news literacy training. Not so much.

Instead, we need other interventions: start by worrying about Grandpa. But I will argue this is not about dealing with Grandpa’s inability to discern facts. Fact-checking won’t enlighten Gramps. Instead, we have to examine Grandpa’s misplaced sense of anger, victimhood, paranoia, and general grumpiness. Grandpa grew up in a great time in this country and saw tremendous progress. So what’s making Grandpa into such an angry, loud-mouthed jerk?

Well, there’s another external factor that this study could not deal with. The factor I want to examine is how many fake-news sharers — how many Grandpa’s — are influenced by media, namely Fox News and talk radio.

I’d love to see more research such as this. I want to see Facebook and the platforms cooperate and hand over more data.

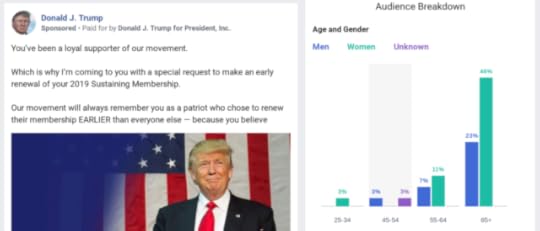

The researchers — Princeton’s Andrew Guess and NYU’s Jonathan Nagler and Joshua Tucker — point out that they lack data on what these older users are seeing in their feeds. To get perhaps some insight on that, go to Facebook’s new, open political ad archive, search on any contentious topic — say, “wall” — and you will see how money vs. money is battling for the minds of America. Look at Trump’s latest ads and I found in many of them that they were directed mostly at people over the age of 65.

Research such as this is critical to inform our discussion and fend off stupid interventions and decisions fueled by bad presumption and moral panic. More, please.

* Thanks to Josh Tucker for alerting me to this research — and for the joke in the headline.

The post The kids are alright. Grandpa’s the problem. appeared first on BuzzMachine.

January 6, 2019

Hot Trump. Cool @aoc.

I’ve been rereading a lot of Marshall McLuhan lately and I’m as confounded as ever by his conception of hot vs. cool media. And so I decided to try to test my thinking by comparing the phenomena of Donald Trump and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at this millennial media wendepunkt, as text and television give way to the net and whatever it becomes. I’ll also try to address the question: Why is @aoc driving the GOP mad?

McLuhan said that text and radio were hot media in that they were high-definition; they monopolized a sense (text the eye, radio the ear); they filled in all the blanks for the reader/listener and required or brooked no real interaction; they created — as we see with newspapers and journalism — a separation of creator from consumer. Television, he said, was a cool medium for it was low-definition across multiple senses, requiring the viewer to interact by filling in the blanks, starting quite literally with the blanks between the raster lines on the cathode-ray screen. “Low-definition invites participation,” explains McLuhan’s recently departed son Eric. (Thanks to Eric’s son, Andrew McLuhan, for sending me to this delightful video:)

Given that McLuhan formulated his theory at the fuzzy, black-and-white, rabbit-ears genesis of television, I wonder how much the label would be readjusted with 4K video and huge, wrap-around screens and surround sound. Eric McLuhan answers that hot v. cool is a continuum. I also wonder — as does every McLuhan follower — what the master would say about the internet. That presumes we can yet call the internet a thing unto itself and define it, which we can’t; it’s too early. So I’ll narrow the question to social media today.

And that brings us to Trump v. Ocasio-Cortez. Recall that McLuhan said that Richard Nixon lost his debate with John F. Kennedy because Nixon was too hot for the cool medium of TV. He told Playboy:

Kennedy was the first TV president because he was the first prominent American politician to ever understand the dynamics and lines of force of the television iconoscope. As I’ve explained, TV is an inherently cool medium, and Kennedy had a compatible coolness and indifference to power, bred of personal wealth, which allowed him to adapt fully to TV. Any political candidate who doesn’t have such cool, low-definition qualities, which allow the viewer to fill in the gaps with his own personal identification, simply electrocutes himself on television — as Richard Nixon did in his disastrous debates with Kennedy in the 1960 campaign. Nixon was essentially hot; he presented a high-definition, sharply-defined image and action on the TV screen that contributed to his reputation as a phony — the “Tricky Dicky” syndrome that has dogged his footsteps for years. “Would you buy a used car from this man?” the political cartoon asked — and the answer was no, because he didn’t project the cool aura of disinterest and objectivity that Kennedy emanated so effortlessly and engagingly.

As TV became hotter — as it became high-definition — it found its man in Trump, who is as hot and unsubtle as a thermonuclear blast. Trump burns himself out with every appearance before crowds and cameras, never able to go far enough past his last performance — and it is a performance — to find a destination. He is destruction personified and that’s why he won, because his voters and believers yearn to destroy the institutions they do not trust, which is every institution we have today. Trump then represents the destruction of television itself. He’s so hot, he blew it up, ruining it for any candidate to follow, who cannot possibly top him on it. Kennedy was the first cool television politician. Obama was the last cool TV politician. Trump is the hot politician, the one who then took the medium’s every weakness and nuked it. TV amused itself to death.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was not a candidate of television or radio or text because media — that is, journalists — completely missed her presence and success, didn’t cover her, and had to trip over each other to discover her long after voters had. How did voters discover her? How did she succeed? Social media: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube….

I think McLuhan’s analysis here would be straightforward: Social media are cool. Twitter in particular is cool because it provides such low-fidelity and requires the world to fill in so much, not only in interpretation and empathy but also in distribution (sharing). And Ocasio-Cortez herself is cool in every definition.

She handles her opponents brilliantly on social media, always flying above, never taking flack from them. Some people say she’s trolling the Republicans but I disagree. Trolling’s sole purpose is to get a rise out of an opponent, to make them angry and force them to react. She does not do that. She consistently states her positions and policies with confidence; let the haters hate. Yes, she shoots at her opponents, but like a sniper, always from her position, her platform.

You’re the GOP Minority Whip. How do you not know how marginal tax rates work?

Oh that’s right, almost forgot: GOP works for the corporate CEOs showering themselves in multi-million

December 27, 2018

The Spiegel Scandal and the Seduction of Storytelling

“Everyone who writes knows the seduction of the narrative.”

— Bernhard Pörksen in Die Zeit

The German journalism world is grappling with the implications of a shocking scandal at Der Spiegel: An award-winning, 33-year-old reporter — no, a fabulist and a fraud — named Claas Relotius made up article after article with stunning and audacious contempt for truth, as this fact-checking of his account of the rural American psyche makes clear.

German journalists are questioning Der Spiegel’s process and Relotius’ own psyche (he told his editors that he was motivated by a fear of failure) — as occurred in comparable American scandals of Jayson Blair at The New York Times and Janet Cooke at The Washington Post. But the Germans are digging deeper into the essence of journalism, questioning the perils of the seduction of the narrative form; the misplaced rewards inherent in professional awards; the risk to credibility for the institution in the time of “f*ke news;” the need for investigative self-examination in media; and more.

As best as ubiquitous paywalls and my very, very bad (sehr, sehr schlecht) German will allow [and I do hope my German friends will correct me where I’m wrong], I want to look at what the German journalists are talking about to see what lessons there are for journalists everywhere.

The perils of the story and storyteller

“A beautiful lie.” That is the headline on the essay in Zeit Online quoted above, in which Pörksen, a professor of media studies, discusses the form of the story: “What shows up here is called the narrative distortion, story bias. You have the story in your head, you know what sound readers or colleagues want to hear. And you deliver what works.” And it worked. Relotius was so well-known for his style that his magazine had a label for it: “the Relotius sound.”

In journalism, the story too often becomes a self-fulfilling creation. Early in my career at the Chicago Tribune, I watched a managing editor write a headline — complete with victim and drama — and then direct his investigative task force to go get that story. I worry when I sit in journalism classes and hear talk of getting quotes to fill in “my story,” with the emphasis on the reporter’s control of the narrative. I dislike that our process too often starts — in newsroom and classroom — with pitching a story people will want to read.

This has long been my heresy. Back in 2011, I was questioning the article as the atomic unit of journalism in a time when we were playing instead with flows and streams: journalism as process; the article deconstructed. That roiled storytellers.

The Spiegel affair cuts deeper into our presumptions and make us ask whether our compulsion to make news compelling (yes, entertaining) leads us astray. In various of the German reactions I read, some wondered whether we should in essence make news duller: just the facts, mein Herr. “At last, don’t we need a new objectivity, a return to stricter form,” Pörksen asks, “or instead an absolute and open declaration of subjectivity, which identifies specific description as purely personal perception?” Do we need to admit that journalism is not a mirror to the world (“Spiegel” means mirror) — adhering to the

December 24, 2018

Facebook. Sigh.

I’d rather like to inveigh against Facebook right now as it would be convenient, given that ever since I raised money for my school from the company, it keeps sinking deeper in a tub of hot, boiling bile in every media story and political pronouncement about its screwups. Last week’s New York Times story about Facebook sharing data with other companies seemed to present a nice opportunity to thus bolster my bona fides. But then not so much.

I’d rather like to inveigh against Facebook right now as it would be convenient, given that ever since I raised money for my school from the company, it keeps sinking deeper in a tub of hot, boiling bile in every media story and political pronouncement about its screwups. Last week’s New York Times story about Facebook sharing data with other companies seemed to present a nice opportunity to thus bolster my bona fides. But then not so much.

The most appalling revelation in The Times story was that Facebook “gave Netflix and Spotify the ability to read Facebook users’ private messages.” I was horrified when I read that and was ready to raise the hammer. But then I read Facebook’s response.

Specifically, we made it possible for people to message their friends what music they were listening to in Spotify or watching on Netflix directly from the Spotify or Netflix apps….

In order for you to write a message to a Facebook friend from within Spotify, for instance, we needed to give Spotify “write access.” For you to be able to read messages back, we needed Spotify to have “read access.” “Delete access” meant that if you deleted a message from within Spotify, it would also delete from Facebook. No third party was reading your private messages, or writing messages to your friends without your permission. Many news stories imply we were shipping over private messages to partners, which is not correct.

And I read other background, including from Alex Stamos, Facebook’s former head of security, who has been an honest broker in these discussions:

I’m sorry, but allowing for 3rd party clients is the kind of pro-competition move we want to see from dominant platforms. For ex, making Gmail only accessible to Android and the Gmail app would be horrible. For the NY Times to try to scandalize this kind of integration is wrong.

— Alex Stamos (@alexstamos) December 19, 2018

And there’s James Ball, a respected London journalist — ex Guardian and BuzzFeed — who is writing a critical book about the internet:

The hill I am going to have to reluctantly die on:

Facebook is a bad company that’s done lots of bad things! But “sharing the contents of messages” was to make in-app messaging work! And people who don’t understand APIs shouldn’t write opinion pieces on this!

— James Ball (@jamesrbuk) December 20, 2018

In short: Of course, Netflix and Spotify had to be given the ability to send, receive, and delete messages as that was the only way the messaging feature could work for users. Thus in its story The Times comes off like a member of Congress grandstanding at a hearing, willfully misunderstanding basic internet functionality. Its report begins on a note of sensationalism. And not until way down in the article does The Times fess up that it similarly received a key to Facebook data. So this turns out not to be the ideal opening for inveighing. But I won’t pass up the opportunity.

The moral net

I’ve had a piece in the metaphorical typewriter for many months trying to figure out how to write about the moral responsibility of technology (and media) companies. It has given me an unprecedented case of writer’s block as I still don’t know how to attack the challenge. I interviewed a bunch of people I respect, beginning with my friend and mentor Jay Rosen, who said that we don’t even have agreement on the terms of the discussion. I concur. People seem to assume there are easy answers to the questions facing the platforms, but when the choices gets specific — free speech vs. control, authority vs. diversity, civility as censorship — the answers no longer look so easy.

None of this is to say that Facebook is not fucking up. It is. But its fuckups are not so much of the kind The Times, The Guardian, cable news, and others in media dream of in their dystopias: grand theft user data! first-degree privacy murder! malignant corporate cynicism! war on democracy! No, Facebook’s fuckups are cultural in the company — as in the Valley — which is to say they are more complex and might go deeper.

For example, I was most appalled recently when Facebook — with three Jewish executives at the head — hired a PR company to play into the anti-Semitic meme of attacking George Soros because he criticized Facebook. What the hell were they thinking? Why didn’t they think?

This case, I think, revealed the company’s hubristic opacity, the belief that it could and should get away with something in secret. I’m sure I needn’t point out the irony of a company celebrating publicness being so — to understate the case — taciturn. Facebook must learn transparency, starting with openness about its past sins. I’ve been saying the company needs to perform an audit of its past performance and clear the decks once and for all. But transparency is not just about confession. Transparency should be about pride and value. From the top, Facebook needs to infuse its culture with the idea that everything everyone does should shine in the light of public scrutiny. The company has to learn that secrecy is neither a cloak nor a competitive advantage (hell, who are its competitors anyway?) but a severe liability.

Facebook and its leaders are often accused of cynicism. I have a different diagnosis. I think they are infected with latent and lazy optimism. I do believe that they believe a connected world is a better world — and I agree with that. But Facebook, like its neighbors in Silicon Valley, harbored too much faith in mankind and — apart from spam— did not anticipate how it would be manipulated and thus did not guard against that and protect the public from it. I often hear Facebook accused of leaving trolling and disinformation online because it makes money from those pageviews. Nonsense. Shitstorms are bad for business. I think it’s the opposite: Facebook and the other platforms have not calculated the full cost of finding and compensating for manipulation, fraud, and general assholery. And in some fairness to them, we as a society have not yet agreed on what we want the platforms to do, for I often hear people say — in the same breath or paragraph — that Facebook and Twitter and YouTube must clean up their messes … but also that no one trusts them to make these judgments. What’s a platform to do?

If Facebook and its league had acted with transparent good faith in enacting their missions — and bad faith in anticipating the behavior of some small segment of malignant mankind — then perhaps when Russian or other manipulation reared its head the platforms would have been on top of the problem and would even have garnered sympathy for being victims of these bad actors. But no. They acted impervious when they weren’t, and that made it easier to yank them down off their high horses. Media — once technoboosters — now treat the platforms, especially Facebook, as malign actors whose every move and motive is to destroy society.

I have argued for a few years now that Facebook should hire an editor to bring a sense of public responsibility to the company and its products. As a journalist, that’s rather conceited, for as I’ll confess shortly, journalists have issues, too. Then perhaps Facebook should hire ethicists or philosophers or clergy or an Obama or two. It needs a strong, empowered, experienced, trusted, demanding, tough force in its executive suite with the authority to make change. While I’m giving unsolicited advice, I will also suggest that when Facebook replaces its outgoing head of coms and policy, Elliot Schrage, it should separate those functions. The head of policy should ask and demand answers to tough questions. The head of PR is hired to avoid tough questions. The tasks don’t go together.

So, yes, I’ll criticize Facebook. But I also believe it’s important for us in journalism to work with Facebook, Twitter, Google, YouTube, et al because they are running the internet of the day; they are the gateways to the public we serve; and they need our help to do the right thing. (That’s why I do what I do in the projects I linked to in the first sentence above.)

Moral exhibitionism

Instead, I see journalists tripping over each other to brag on social media about leaving social media. “I’m deleting Facebook — find me on Instagram,” they proclaim, without irony. “I deleted Facebook” is the new “I don’t own a TV.” This led me to tweet:

I want to quit the platform people are using to brag to the world that they’re quitting platforms.

— Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) December 19, 2018

People with discernible senses of humor got the gag. One person attacked me for not attacking Facebook. And meanwhile, a few journalists agonized about the choice. A reporter I whose work I greatly respect, Julia Ioffe, was visibly torn, asking:

A very real dilemma: do I deactivate my Facebook account or do I keep it because Facebook remains one of the only platforms for free discussion in Russia and is therefore key to doing my job?

— Julia Ioffe (@juliaioffe) December 19, 2018

I responded that Facebook enriches her reporting and that journalists need more — not fewer — ways to listen to the public we serve. She said agreed with that. (I just asked what she decided and Ioffe said she is staying on Facebook.)

Quitting Facebook is often an act of the privileged. (Note that lower income teens are about twice as likely to use Facebook as teens from richer families.) It’s fine for white men like me to get pissy and leave because we have other outlets for our grievances and newsrooms are filled with people who look like us and report on our concerns. Without social media, the nation would not have had #metoo or #blacklivesmatter or most tellingly #livingwhileblack, which reported nothing that African-Americans haven’t experienced but which white editors didn’t report because it wasn’t happening to them. The key reason I celebrate social media is because it gives voice to people who for too long have not been heard. And so it is a mark of privilege to condemn all social media — and the supposed unwashed masses using them — as uncivilized. I find that’s simply not true. My Facebook and Twitter feeds are full of smart, concerned, witty, constructive people with a wide (which could always be wider) diversity of perspective. I respect them. I learn by listening to them.

When I talked about all this on the latest This Week in Google, I received this tweet in response:

@jeffjarvis Very much appreciated your comments today on This Week in Google equating leaving Facebook with privilege. For some of us who are underemployed and socially isolated, quitting at this point in history is a luxury we simply can’t afford.

— Jeff Castel De Oro (@jeffcdo) December 20, 2018

I thanked Jeff and immediately followed him on Facebook.

A moral mirror

These days, too much of the reporting about the internet is done without knowledge of how technology works and without evidence behind the accusations made. I fear this is fueling a moral panic that will lead to legislation and regulation that will affect not just a few Silicon Valley technology companies but everyone on the net. This is why I so appreciate voices like Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, now head of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford, who often meets polemical presumptions about the net — for example, that we are supposedly all hermetically sealed in filter bubbles — with demands for evidence as well as research that dares contradict the pessimistic assertion. This is why I plan to convene a meeting of similarly disciplined researchers to examine how bad — or good — life on the net really is and to ask what yet needs to be asked to learn more.

Dave Winer, a pioneer in helping to create so much of the web we enjoy today (podcasts, RSS, blogging…) is quite critical of the closed systems the platforms create but also was very frustrated with the New York Times story that inspired this post:

Also I watched nyt tech coverage for decades from inside tech, and they kissed a lot of bigco ass over the years. Then they decided quite openly to destroy Facebook, probably because they were threatened by them. This is what happens when tech stops playing the access game.

— scripting.com (@davewiner) December 20, 2018

Could this be why usually advocacy-allergic news organizations are oddly taking it upon themselves to try to convince people to delete Facebook?

This is also why Dave also had a suggestion for journalists covering technology and for journalism schools:

The whole thing is a huge mess. One of the big journalism schools should have a conference with tech people and journalists and we should put our heads together and figure out how this stuff should be covered.

— scripting.com (@davewiner) December 22, 2018

A bunch of us journo profs jumped on his idea and I hope we all make it happen soon.

But there’s more journalists need to do. As we in news and media attack the platforms and their every misstep — and there are many — we need to turn the mirror on ourselves. It was news media that polarized the nation into camps of red v. blue, white v. black, 1 percent v. 99 percent long before Facebook was born. It was our business model in media that favored confrontation over resolution. It was our business model in advertising that valued volume, attention, page views, and eyeballs — the business model that then corrupted the internet. It was our failure to inform the public that enabled people to vote against their self-interest for Trump or Brexit. We bear much responsibility for the horrid mess we are in today.

So as we demand transparency of Facebook I ask that we demand it of ourselves. As we expect ethical self-examination in Silicon Valley, we should do likewise in journalism. As we criticize the skewed priorities and moral hazards of technology’s business model, let us also recognize the pitfalls of our own — and that includes not just clickbait advertising but also paywalls and patronage (which will redline journalism for the privileged). Let us also be honest with ourselves about why trust in journalism is at historic lows and why people chose to leave the destinations we built for them, instead preferring to talk among themselves on social media. Let he who should live in a glass house — and expects everyone else to live in glass houses — think before throwing stones.

I’m neither defending nor condemning Facebook and the other platforms. My eyes are wide open about their faults — and also ours. They and the internet they are helping to build are our new reality and it is our mutual responsibility to build a better net and a better future together. These are difficult, nuanced problems and opportunities.

The post Facebook. Sigh. appeared first on BuzzMachine.

August 12, 2018

There is no Trump without Murdoch

In the video above you will see New York Mayor Bill de Blasio trying to school CNN senior media correspondent Brian Stelter in the most important and most undercovered story in media today, a story that’s right under his nose: the ruinous impact of Fox News and Rupert Murdoch on American democracy. You’ll then see Stelter dismiss the critique in a fit of misplaced journalistic both-sideism.

Without Murdoch — without Fox News nationally and the New York Post locally — “we would be a more unified country,” de Blasio tells Stelter. “There would be less overt hate. There would be less appeal to racial division…. They put race front and center and they try to stir the most negative impulses in this country. There is no Donald Trump without News Corp.”

Stelter: “You’d rather not have Fox News or the New York Post exist?”

de Blasio: “I’m saying because they exist we’ve been changed for the worse.”

Stelter: “But isn’t that like saying they’re fake news or an enemy of the people?”

Jarvis: Sigh. No. He is criticizing Murdoch particularly. He’s not criticizing all of media. He’s not trying to send the public into battle against them. He’s not trying to kill them. He’s saying News Corp does a bad job. He’s saying they harm the nation. He’s right. Listen to him.

Stelter a little later: “Politicians make lousy media critics. Why do you feel it’s your role to be calling out a newspaper?”

de Blasio: “Because I think it’s not happening enough…. When it comes to News Corp., they have a political mission and we have to be able to talk about it.”

Stelter: “But singling out News Corp., it’s like Trump singling out CNN. Two wrongs don’t make a right.”

Jarvis: Scream. No, News Corp. is singular. That is the point de Blasio is trying to make as he compares them to CNN, the other networks, The New York Times, and The Washington Post: “One of these things is not like the others.” There is nothing like News Corp. in this country or in recent history. We’re not talking about that and we should be. When I say “we” I don’t just mean the nation, I specifically mean us in journalism and media and I very much mean media reporters and critics — that is de Blasio’s further critique. This is not a matter of balance, of symmetry, of two wrongs. The behavior of Fox News and of the right is asymmetrical. That is the key lesson of the election of 2016. If we do not start there, we are nowhere.

Now I’ll grant a few caveats: The rest of media are liberal and don’t admit it and that’s much of the reason they’re not trusted by half the nation. de Blasio also brings baggage when it comes to criticizing local media that criticize him. Because I teach at the City University of New York, I suppose I’m employee of the mayor’s. And I’ve been a fan of Stelter’s since he was in college. But I think Stelter is wrong to dismiss de Blasio’s critique because de Blasio is a politician, not a media critic. Indeed, we in media need to listen to voices other than our own.

de Blasio also brings caveats of his own. He supports the First Amendment. He supports free speech. He supports the press. He likes apple pie. (I’m guessing.) But that’s not good enough for Stelter, who accuses de Blasio of criticizing News Corp. because he wants to run for president. That is reportorial cynicism in action: ascribing cynicism to the motive of anyone you interview so you can seem to be tough on them rather than dealing with their critique and message at face value.

I imagine Stelter is frightened of criticizing Fox News directly because it is (a) a competitor and (b) conservative and we know that shit storm will rain from the right. So be it.

I will not mince words: Rupert Murdoch has single-handedly brought American democracy to ruin. Cable news — especially CNN — made its business on conflict and the rest of media built theirs on clickbait but only Fox News is built to — in de Blasio’s words — “sensationalize, racialize, and divide.” Rupert Murdoch and News Corp. are specifically to blame. How can any civilized soul, let alone a media correspondent, not have heard Laura Ingraham’s bilious racist rant last week and then demanded in all caps and bold: HOW THE FUCK IS THIS ON TELEVISION? WHO ALLOWS THIS? Murdoch does.

Media are fretting and kvetching about Twitter and Facebook enabling a few — yes, a few — crackpots to speak but it’s Fox News that has the bigger megaphone. It’s Murdoch that empowers Trump. It’s Fox News that instructs him on what to do, as we can see on Twitter every morning. Murdoch has far more impact than Infowars or any random asshole in your Twitter feed. de Blasio could not be more right: Rupert Murdoch made Donald Trump. He made it acceptable for the racism we saw in Washington this weekend to come out into the light. This is a damned big media story that media are not covering. So what if it takes a politician to bring attention to it? Credit Stelter for inviting de Blasio on after he gave a preview of his perspective to The Guardian. But arguing with him does not necessarily journalism make. Journalism is also listening, probing, exploring, understanding.

I go into class this week urging students to become media critics, to question what they see in journalism and why it is done that way. To prepare, I’m rereading The Elements of Journalism by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel. In it, they quote Murdoch when he won TV rights in Singapore:

Singapore is not liberal, but it’s clean and free of drug addicts. Not so long ago it was an impoverished, exploited colony with famines, diseases and other problems. Now people find themselves in three-room apartments with jobs and clean sheets. Material incentives create business and the free market economy. If politicians try it the other way around with democracy first, the Russian model is the result. Ninety percent of the Chinese are interested more in a better material life than in the right to vote.