Brian Fies's Blog, page 49

July 28, 2017

Robotic Ruminations

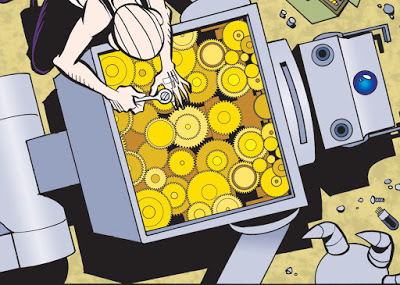

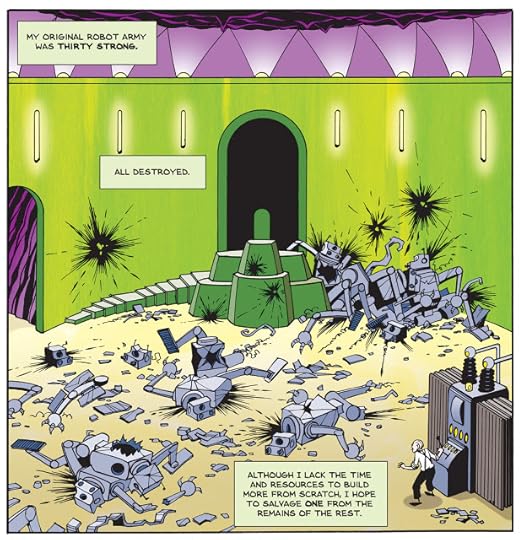

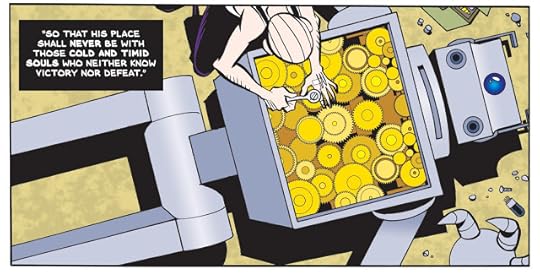

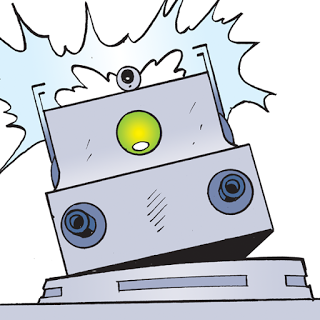

I had a comment/reply on my "Last Mechanical Monster" webcomic, currently running on GoComics.com, I thought was interesting enough to share. (Background info: my story is a sequel to a 75-year-old Superman cartoon.) A reader questioned a drawing in which I showed my Robot full of gears, saying gears'd be too heavy and slow. My reply is a good example of how I approach a story:

"(That's) something I actually spent quite a lot of time mulling over before I even began 'The Last Mechanical Monster': How does the Robot work? I thought hard and seriously about it for some time, drew a lot of diagrams, and decided it simply can’t, especially with a mostly hollow chest cavity (as shown in the Fleischer cartoon). There’s no way to attach the arms, no place to put a motor for its neck-propeller, no room for an engine or batteries, etc.

"Basically I had to decide if I was telling a science fiction story or a fantasy story (I think it’s fair to say Superman himself could go either way), and the total impossibility of the Robot convinced me I was writing fantasy. If this were science fiction, I wouldn’t have filled his chest with gears; since it’s fantasy, and I thought gears looked cool and fit with some themes I develop later in the story, I went for it.

"Think of the gears less as a way to move a robot and more as a metaphor to reveal a character."

Published on July 28, 2017 13:19

June 30, 2017

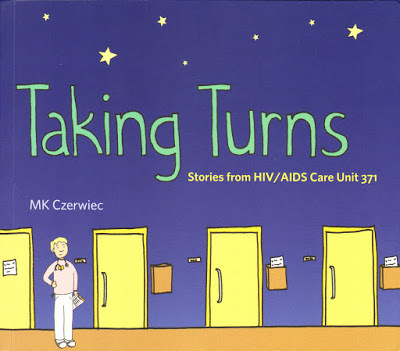

Taking Turns by MK Czerwiec

I like it when friends write good, interesting, even important books. It removes any awkwardness from your next meeting when they ask you what you thought and you can honestly say it was great.

Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371 is by my friend MK Czerwiec, who as "Comic Nurse" is one of the ringleaders of the Graphic Medicine community. It's the story of her experience as a nurse on a pioneering hospital unit through the 1990s, from the early days of a mysterious deadly disease to the day AIDS treatment became so effective that Unit 371 closed and MK was the last one left to turn off the lights.

Done as a graphic novel, Taking Turns is part memoir, part oral history, and mostly journalism. It's deeply personal. MK writes about her struggles as a young nurse learning the job and finding her place, the panic of an accidental needle-stick, and the challenge of maintaining professional distance--or even knowing if she should maintain professional distance. Doctors, nurses and volunteers broke some rules getting close to patients who were mostly going to die, and while none of them seem to regret it, it took its toll.

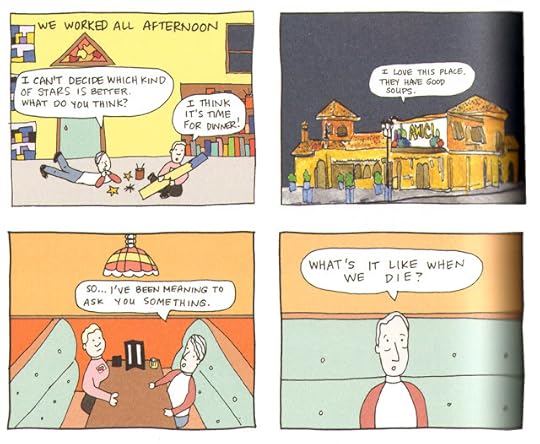

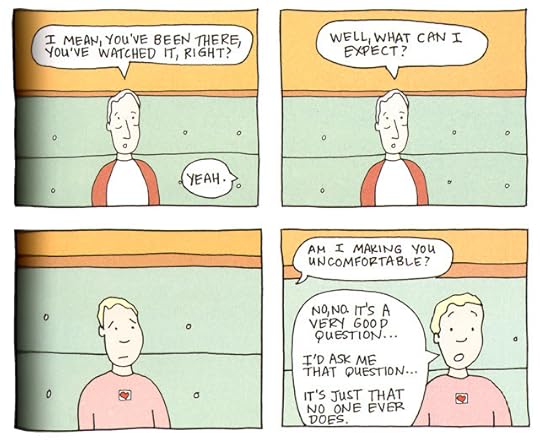

A two-page sequence with MK (in the pink shirt) and Tim, a patient and artist whom MK got to know away from Unit 371. Tim's experience is a major arc through the book, and must represent the fate of dozens of patients MK cared for. The first panel also touches on the motif of stars, to which MK returns throughout the book. Pay no mind to the dark bands on these pages. I scanned them myself and didn't want to break the book's spine to lay it flat on the scanner, so they curved a bit.

A two-page sequence with MK (in the pink shirt) and Tim, a patient and artist whom MK got to know away from Unit 371. Tim's experience is a major arc through the book, and must represent the fate of dozens of patients MK cared for. The first panel also touches on the motif of stars, to which MK returns throughout the book. Pay no mind to the dark bands on these pages. I scanned them myself and didn't want to break the book's spine to lay it flat on the scanner, so they curved a bit. I know from talking to MK while she worked on her book that Taking Turns is primarily intended as an oral history of Unit 371 and the AIDS crisis, captured while memories are still fresh but with the perspective of time. MK needed to record these stories before they faded away. At that, she succeeds tremendously.

MK credits fellow Chicagoan Studs Turkel as one of her influences, and I see that. What strikes me as unusual and ambitious, though, is that MK isn't writing about individual people or even an entire generation, as Turkel might have. Although the story is set in a particular time and place, they aren't her true subjects. There's not much that specifically pins her story to the 1990s, and little that requires it to be in this hospital in this city rather than Miami or Baltimore or San Francisco. Her story, and the stories of all the people she interviewed for Taking Turns, focus on what it felt like to do this job. They were eyewitnesses to history. In that respect, I see Taking Turns foremost as first-person journalism.

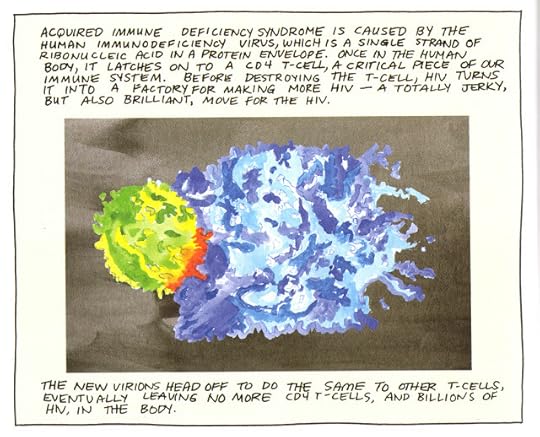

A watercolor by MK illustrating how the HIV virus destroys the immune system.

A watercolor by MK illustrating how the HIV virus destroys the immune system.

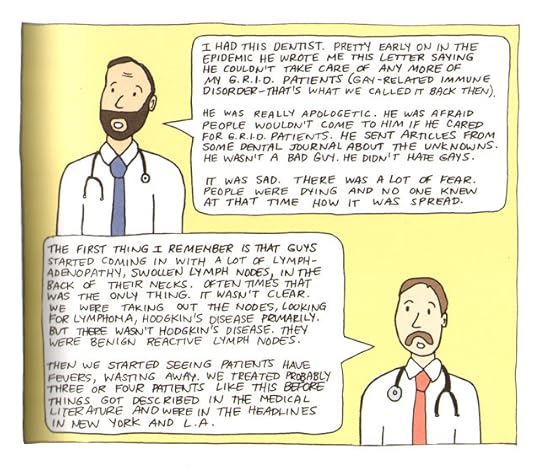

Parts of MK's interviews with the two physicians who started Unit 371. Text-heavy pages like this are interspersed throughout the book, separated by other multi-panel pages that often have little or no text. MK's not afraid of white space and silence. Taking Turns is dense in parts but doesn't feel heavy as a whole. Again, ignore the dark stripe on the left caused by my scan.

Parts of MK's interviews with the two physicians who started Unit 371. Text-heavy pages like this are interspersed throughout the book, separated by other multi-panel pages that often have little or no text. MK's not afraid of white space and silence. Taking Turns is dense in parts but doesn't feel heavy as a whole. Again, ignore the dark stripe on the left caused by my scan.Let's talk about the art. The excerpts above are representative; that's how it looks. For some comics readers, MK's style would be a barrier. I like it. Her drawings provide all the information needed and tell her story clearly. I know that she put great thought into her color palette and the deliberate decision to use flat tones rather than all the gradients and flashy flair that are only a Photoshop click away. It's a "just the facts" approach to comics and, again, journalism that suits the topic. MK is a documentarian whose camera is locked on its tripod and pointed directly at its subject. I respect her choice. It works for me.

A close childhood friend of mine died of AIDS. I don't claim any special insight from that, except that I was there and aware during the time MK wrote about. I think she gets it right, providing the unique perspective of someone working on the side we don't often hear about. I'd like to think and hope that my friend Jim had a nurse like MK looking after him. What I appreciate about Taking Turns is that MK helps me understand what it was like to care for hundreds of Jims during a time of tragedy and hope that shouldn't be forgotten.

Taking Turns is published by Pennsylvania State University Press as part of a Graphic Medicine series that's on its way to becoming an impressive library. Other recent titles in the series include My Degeneration by Peter Dunlap-Shohl and The Bad Doctor by Ian Williams. Penn State is building a special and unique body of work that's worth supporting. Keep an eye on it.

A truly terrible selfie I took with MK in Seattle two weeks ago. Apologies.

A truly terrible selfie I took with MK in Seattle two weeks ago. Apologies.

Published on June 30, 2017 11:46

June 19, 2017

Graphic Medicine: Seattle

I did not have to go out of my way to find Starbucks in Seattle. However, I understand that the one at top left is the original coffee shop that built an empire, which would explain the constant scrum of pilgrims snaking out the door and down the block.

I did not have to go out of my way to find Starbucks in Seattle. However, I understand that the one at top left is the original coffee shop that built an empire, which would explain the constant scrum of pilgrims snaking out the door and down the block.There've been eight international Graphic Medicine Conferences since 2010. I've been to six of them. We've developed some traditions, one of which is that I always write a long and windy blog post when I get home. Another tradition, as explained by graphic medicine (GM) guru Ian Williams, is that if I don't proclaim every conference "the best one ever," they'll know they've failed.

Luckily, this was the best one ever.

Comics and medicine seems like an odd combination, but it works. Patients make comics about being patients, doctors and nurses make comics about being doctors and nurses. Comics teach kids how to use inhalers, encourage Australian aborigines to use public health clinics, and get informed consent from children undergoing medical procedures. In addition to tons of graphic memoirs that touch on medical topics (mine, Epileptic, Cancer Made Me a Shallower Person, Pedro & Me, Special Exits, Hyperbole and a Half, Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Tangles, Marbles, Psychiatric Tales and many many more), people find myriad fascinating ways to work comics into healthcare themes or practice.

Professors, students, doctors, nurses, writers, artists, cartoonists and others get together at these conferences to meet and compare notes. People come from all over North America, Europe, Australia, Japan and more. It's a big tent.

In every previous conference, I've done some sort of talk or workshop. It took me this long to figure out I could just go to the thing without doing all that work. I recommend it!

Some faces and names will show up repeatedly in the photos below:

The aforementioned Ian Williams, one of two proprietors of the GM website, coiner of the term "graphic medicine," a British M.D., author of The Bad Doctor graphic novel, co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and recent first-time father.

"Comic Nurse" MK Czerwiec, the other proprietor of the website, a Chicago nurse and teacher, another co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and author of the new graphic novel Taking Turns about her experience on an early AIDS ward.Mita Mahato, an associate professor of English and cartoonist who does beautiful cut-paper art, has a book of poetry coming out in the fall, and was the on-the-ground lead for the Seattle conference.Susan Squier, professor of English and Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Penn State University, yet another co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and part of the organizing committee.Michael Green, an M.D. and bioethicist at Penn State University, yet another co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and part of the organizing committee.Juliet McMullin, a cultural and medical anthropologist at UC Riverside, who led the organizing for 2015's conference in Riverside, Calif.I hope I got all that right. I'll introduce others as they come up. Assume every name I mention is preceded by the words "my friend." Pictures (most of which were taken on an iPhone in poor lighting) to prove it happened:

"Comic Nurse" MK Czerwiec, the other proprietor of the website, a Chicago nurse and teacher, another co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and author of the new graphic novel Taking Turns about her experience on an early AIDS ward.Mita Mahato, an associate professor of English and cartoonist who does beautiful cut-paper art, has a book of poetry coming out in the fall, and was the on-the-ground lead for the Seattle conference.Susan Squier, professor of English and Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Penn State University, yet another co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and part of the organizing committee.Michael Green, an M.D. and bioethicist at Penn State University, yet another co-author of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, and part of the organizing committee.Juliet McMullin, a cultural and medical anthropologist at UC Riverside, who led the organizing for 2015's conference in Riverside, Calif.I hope I got all that right. I'll introduce others as they come up. Assume every name I mention is preceded by the words "my friend." Pictures (most of which were taken on an iPhone in poor lighting) to prove it happened: The conference was held at the main Seattle Public Library, a modern steel and glass building with a strange fourth floor, where some of our sessions were held. The whole level was painted red, with intense spotlighting and twisting, rounded walls. It felt like being inside a living heart and was a little unnerving.

The conference was held at the main Seattle Public Library, a modern steel and glass building with a strange fourth floor, where some of our sessions were held. The whole level was painted red, with intense spotlighting and twisting, rounded walls. It felt like being inside a living heart and was a little unnerving. The fourth floor. Lub-dub, lub-dub, lub-dub, redrum.

The fourth floor. Lub-dub, lub-dub, lub-dub, redrum. Ian Williams and MK Czerwiec, photobombed by Mita Mahato. I love this picture.

Ian Williams and MK Czerwiec, photobombed by Mita Mahato. I love this picture. Smart and talented Shelley Wall and Dana Walrath have been important parts of these conferences. Shelley organized the Toronto conference in 2012; Dana authored a book titled Aliceheimer's and presented on her latest project in Seattle.

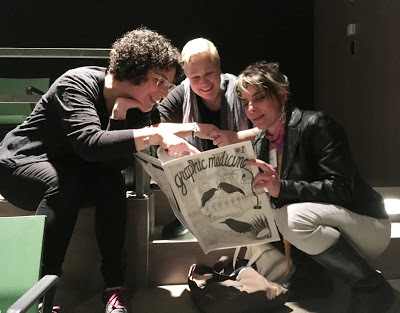

Smart and talented Shelley Wall and Dana Walrath have been important parts of these conferences. Shelley organized the Toronto conference in 2012; Dana authored a book titled Aliceheimer's and presented on her latest project in Seattle. Tangles cartoonist Sarah Leavitt, MK, and Marbles cartoonist Ellen Forney pretend to peruse an anthology of comics produced for the conference because they saw my camera and wanted to look impressive.

Tangles cartoonist Sarah Leavitt, MK, and Marbles cartoonist Ellen Forney pretend to peruse an anthology of comics produced for the conference because they saw my camera and wanted to look impressive. "So four doctors and a lawyer walk into a bar . . ." In front, cartoonist-physicians Ian Williams, cartoonist-physician Theresa Maatman, and non-cartoonist physician Michael Green. Behind, professor and attorney Dan Bustillos and Australian psychiatrist-cartoonist Neil Phillips.

"So four doctors and a lawyer walk into a bar . . ." In front, cartoonist-physicians Ian Williams, cartoonist-physician Theresa Maatman, and non-cartoonist physician Michael Green. Behind, professor and attorney Dan Bustillos and Australian psychiatrist-cartoonist Neil Phillips.A few interesting themes spontaneously emerged over the weekend. One concerned the growth and spread of the GM concept. I heard a lot about Graphic Anthropology--not sure what it is or who does it, though I suspect anthropologist Juliet McMullin is a ringleader. Professor-lawyer Dan Bustillos, whose classes I occasionally crash via Skype, introduced me to Graphic Justice, which is what happens when comics meet law. There were a lot of young first-timers at this conference, and, it seemed to me, a real explosion of recent books that fit under the GM umbrella. When I did Mom's Cancer there were maybe one or two dozen in the canon; now it seems like there are hundreds.

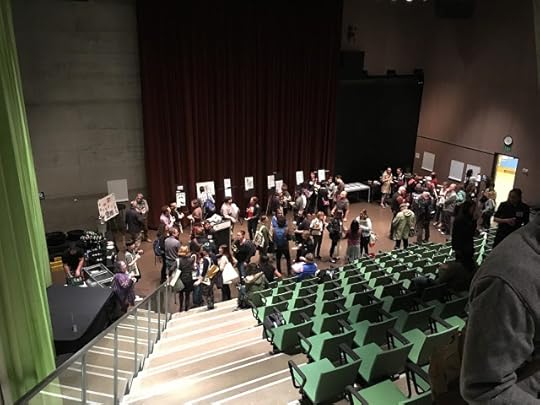

An overview of the big, main auditorium where the keynote speeches and some of the panels took place. Other panels were in rooms on the red fourth floor (shudder) upstairs.

An overview of the big, main auditorium where the keynote speeches and some of the panels took place. Other panels were in rooms on the red fourth floor (shudder) upstairs.

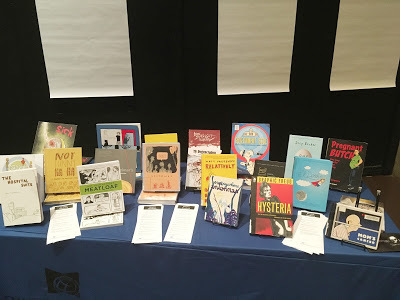

The Seattle Public Library pulled several GM comics from their shelves for display and browsing, and provided reading lists for dozens more. The white sheets of paper on the wall were taped up for people to draw on.

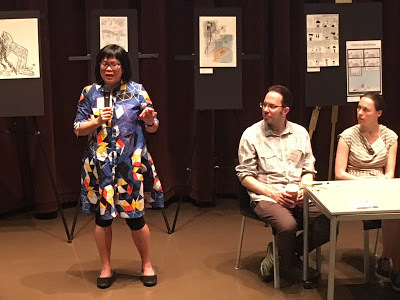

The Seattle Public Library pulled several GM comics from their shelves for display and browsing, and provided reading lists for dozens more. The white sheets of paper on the wall were taped up for people to draw on. Conference co-planner Meredith Li-Vollmer, Eisner-winning cartoonist David Lasky, and Nikki Eller talk about public health comics they've made for King County (Wash.) that have been translated into two dozen languages. Behind them is original art for a silent auction.

Conference co-planner Meredith Li-Vollmer, Eisner-winning cartoonist David Lasky, and Nikki Eller talk about public health comics they've made for King County (Wash.) that have been translated into two dozen languages. Behind them is original art for a silent auction.  Juliet McMullin on "Accessing Land-Based Health with Indigenous Graphic Narratives."

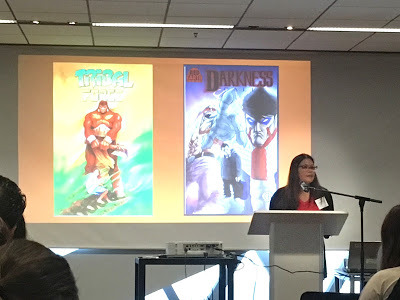

Juliet McMullin on "Accessing Land-Based Health with Indigenous Graphic Narratives." Courtney Donovan of San Francisco State University on "Graphic Narratives and Nomadic Subjectivities."

Courtney Donovan of San Francisco State University on "Graphic Narratives and Nomadic Subjectivities." Susan Squier moderating a panel in one of the smaller rooms.

Susan Squier moderating a panel in one of the smaller rooms.

Juliet McMullin, Amerisa Waters (who's working toward her PhD in Medical Humanities), and Neil Phillips.

Juliet McMullin, Amerisa Waters (who's working toward her PhD in Medical Humanities), and Neil Phillips.

Journalist-comedian-cartoonist Aaron Freeman and Mita Mahato.

Journalist-comedian-cartoonist Aaron Freeman and Mita Mahato. Ian Williams illustrated a wry and dry progress report on his next book with a drawing of his family.

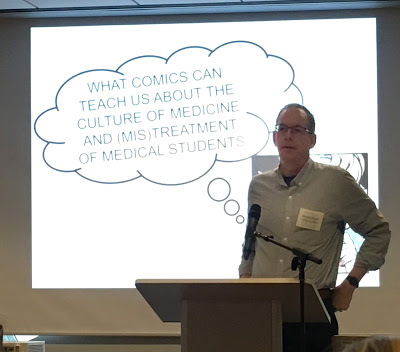

Ian Williams illustrated a wry and dry progress report on his next book with a drawing of his family. Michael Green asks medical students to make comics about the hardships of medical school. The results are enlightening.

Michael Green asks medical students to make comics about the hardships of medical school. The results are enlightening.Some people told me how much they appreciated Mom's Cancer, and many cited it in their talks or said they teach it in their classes, which is a deeply gratifying legacy. One story I want to tell at the risk of immodesty: a young PhD gave a talk on "Webcomics Building Communities," focusing mostly on Allie Brosh's Hyperbole and a Half but mentioning Mom's Cancer along the way. I thought she made some good insightful points, so during the panel Q&A I stood up, said that I'd done Mom's Cancer, which started as a webcomic and went to print, and had some thoughts on the topic.

We had a good exchange. In private afterward, she said she'd had no idea I was there and would have been terrified if she had, while I confessed that the opportunity to have my Marshall McLuhan "Annie Hall" moment ("You know nothing of my work...How you ever got to teach a class in anything is totally amazing!") was nearly irresistible. We'll keep in touch.

The conference ended with a marketplace for people to sell their stuff. I'd brought a pretty big stack of cash to spend, but still ran out of money--and, more importantly, space in my carry-on luggage--before I hit all the tables. Sorry, I did my best.

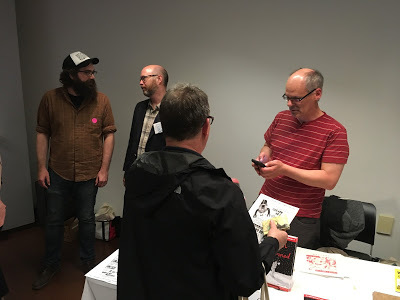

Peter Dunlap-Shohl (My Degeneration), MK Czerwiec and Ian Williams selling well at the marketplace. All three are published by Penn State University Press, whose Graphic Medicine Series is growing into an impressive and important library.

Peter Dunlap-Shohl (My Degeneration), MK Czerwiec and Ian Williams selling well at the marketplace. All three are published by Penn State University Press, whose Graphic Medicine Series is growing into an impressive and important library. Kurt Schaffert (second from left) and James Sturm (right) from the Center for Cartoon Studies have committed to hosting the next GM Conference in White River Junction, Vermont. Fools. Mark your calendar for August 16-18, 2018.

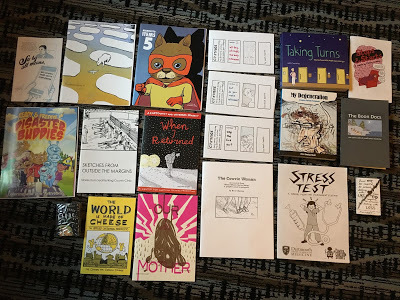

Kurt Schaffert (second from left) and James Sturm (right) from the Center for Cartoon Studies have committed to hosting the next GM Conference in White River Junction, Vermont. Fools. Mark your calendar for August 16-18, 2018. My haul from the marketplace. I'm looking forward to reading it all.

My haul from the marketplace. I'm looking forward to reading it all.

Mild Night Life

Both nights of the conference were capped with extracurriculars. After the first full day, many attendees made the long trek south to the Fantgraphics Bookstore and Gallery, which for fans of sophisticated comics literature is a bit like a pilgrimage to Mecca. It's a small space packed with terrific stuff. After the second day, we adjourned to the Raygun Lounge, another funky space providing beverages, gaming tables, and vintage pinball machines.

Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery

Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery One little wing of the Fantagraphics store.

One little wing of the Fantagraphics store. As I wrote on Facebook, what I really love about these GM conferences is the improbable confluence of events that would put cartoonists Ellen Forney, David Lasky and me talking shop in a corner of the Fantagraphics bookstore. Before that moment, I wouldn't have bet those odds.

As I wrote on Facebook, what I really love about these GM conferences is the improbable confluence of events that would put cartoonists Ellen Forney, David Lasky and me talking shop in a corner of the Fantagraphics bookstore. Before that moment, I wouldn't have bet those odds.

Another selfie, this one the next day with MK at the Raygun Lounge.

Another selfie, this one the next day with MK at the Raygun Lounge. You can tell these people are artists because they all have their heads down drawing instead of drinking, talking, brawling, or dancing on the table.

You can tell these people are artists because they all have their heads down drawing instead of drinking, talking, brawling, or dancing on the table. A second table at the Raygun covered with butcher paper for art, with Neil Phillips at the head and our wonderful final keynote speaker Rupert Kinnard to Neil's left (your right). Do yourself a favor and click the link on Rupert's name; his life and work cover a lot of struggle and history. I'd been sitting in that empty space along the window and did that black scribble that I'll show you after I explain something . . .

A second table at the Raygun covered with butcher paper for art, with Neil Phillips at the head and our wonderful final keynote speaker Rupert Kinnard to Neil's left (your right). Do yourself a favor and click the link on Rupert's name; his life and work cover a lot of struggle and history. I'd been sitting in that empty space along the window and did that black scribble that I'll show you after I explain something . . .One interesting theme that emerged through the conference was "catharsis." More than one presenter talked about how making comics about illness and medical care isn't really cathartic at all: it's too hard, too slow, and doesn't accomplish the "expelling and healing" that catharsis implies. So some of us were sitting around near the end of the last day agreeing that that was a good point when Rupert Kinnard talked for an hour about comics as catharsis and introduced the humorous past-tense verb "catharted." Rupert confused and unconvinced me.

So later at the Raygun I did a doodle of my Last Mechanical Monster and the Cosmic Kid, to which my friend Mita Mahato added the red word balloons "I Catharted" and "Um...I know." And then we just doodled together while we talked, adding a mountain landscape, UFOs, and a little outhouse on the Moon in a way I haven't since my kids and I drew on restaurant placemats when they were toddlers. (An outhouse door on the Moon has a crescent Earth!) I highly recommend it.

So later at the Raygun I did a doodle of my Last Mechanical Monster and the Cosmic Kid, to which my friend Mita Mahato added the red word balloons "I Catharted" and "Um...I know." And then we just doodled together while we talked, adding a mountain landscape, UFOs, and a little outhouse on the Moon in a way I haven't since my kids and I drew on restaurant placemats when they were toddlers. (An outhouse door on the Moon has a crescent Earth!) I highly recommend it.Seattle

Seattle is a good city for hosting an event like this. Its core is very walkable, public transit is convenient and not too hard to figure out, and its setting is beautiful. The vagaries of flight schedules made it best for me to arrive a day early and fly home a day late, immediately after a reading and signing for MK's book Taking Turns at a local bookstore.

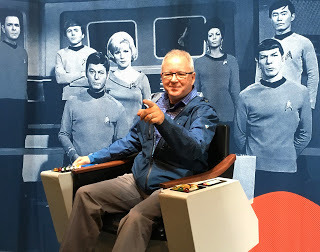

Of course I walked the waterfront and Pike Place Market. With time to kill and a passion for World's Fairs of the past, I also visited the site of the 1962 World's Fair, riding the monorail built for the event to its centerpiece, the Space Needle. Imagine my astonishment finding the Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP) right next door, then my giggling delight at finding it had a wing dedicated to "Star Trek."

A. Star. Trek. Museum.

The 1962 ALWEG monorail, built by the same folks who did Disneyland's. Retro cool transportation of the past future. Or the future past. Whichever.

The 1962 ALWEG monorail, built by the same folks who did Disneyland's. Retro cool transportation of the past future. Or the future past. Whichever. An angle on the Space Needle shot through some floral metal sculptures (hard to tell from this angle, but the flowers are about the height of light posts).

An angle on the Space Needle shot through some floral metal sculptures (hard to tell from this angle, but the flowers are about the height of light posts).

Seattle from the tippy-top.

Seattle from the tippy-top.

The Space Needle does that thing where they ask visitors to stand in front of a green screen to be electronically superimposed onto different backgrounds (it's free there, which it isn't most places). Since I was alone and didn't care, I asked the photographer if I could do something odd. She was game. Later, when scrolling through possible backgrounds, I saw this one, guffawed, and knew I'd found my match. You take one wrong step . . .

The Space Needle does that thing where they ask visitors to stand in front of a green screen to be electronically superimposed onto different backgrounds (it's free there, which it isn't most places). Since I was alone and didn't care, I asked the photographer if I could do something odd. She was game. Later, when scrolling through possible backgrounds, I saw this one, guffawed, and knew I'd found my match. You take one wrong step . . . The monorail track ends in this Frank Gehry building that houses the MoPOP.

The monorail track ends in this Frank Gehry building that houses the MoPOP.

Ohmygod. It's Captain Kirk's actual chair, and Sulu and Chekov's actual console. And Kirk's actual tunic. And Uhura's actual dress.

Ohmygod. It's Captain Kirk's actual chair, and Sulu and Chekov's actual console. And Kirk's actual tunic. And Uhura's actual dress. Ohmygod ohmygod! And actual phasers and tricorders and communicators and hyposprays!

Ohmygod ohmygod! And actual phasers and tricorders and communicators and hyposprays! OHMYGOD OHMYGOD OHMYG---

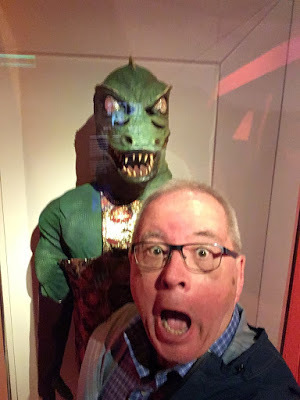

OHMYGOD OHMYGOD OHMYG--- The MoPOP also has these guys . . .

The MoPOP also has these guys . . . . . . and those guys . . .

. . . and those guys . . .

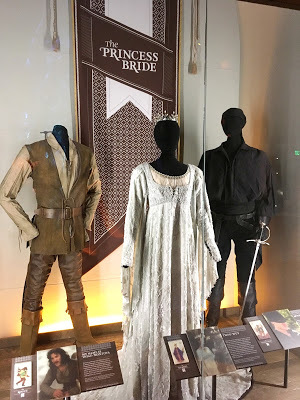

Plus a special exhibition on these guys . .

Plus a special exhibition on these guys . .  . . . and those guys . . .

. . . and those guys . . .. . . and all the other pop culture, rock-and-roll, and show business artifacts that Microsoft money could buy. I really enjoyed MoPOP, all the more because I didn't know it was there and just stumbled onto it. What a discovery.

Going Home

My flight home was one of the best I've had in years. The plane was only about a quarter full and took off due south at sunset, giving us wonderful views of the snowcapped Cascades. I took a few photos out the window, knowing that they never capture one-tenth the beauty you see by eye.

Mount St. Helens in the foreground, Mount Adams in the background. Notice the shadow of St. Helens stretching off to the upper right behind it. Neat!

Mount St. Helens in the foreground, Mount Adams in the background. Notice the shadow of St. Helens stretching off to the upper right behind it. Neat! Crater Lake National Park, Oregon.

Crater Lake National Park, Oregon.What a wonderful trip. As I told several people during the conference, I always go home from a big comics convention, such as the San Diego Comic-Con, feeling tired and beaten. I always go home from a GM conference feeling energized and inspired. Today at lunch, Karen asked me why that was.

I really think people at a GM conference, besides just being generally smarter (face it, they're mostly RNs, MDs, MAs, and PhDs), are more deeply interested in the potential of comics as a medium--and stretching the boundaries of that medium---than your typical comics fan. Some of them are trying to make comics do things they've never done before. I went away with ten new approaches to think about and five new ideas I'm just going to outright steal.

The best conference yet. And not entirely because I found a "Star Trek" museum.

Out there. Thataway. Dork Factor 5.*

Out there. Thataway. Dork Factor 5.**Not THE actual chair.

Published on June 19, 2017 15:13

June 12, 2017

Rheinstein Now & Then

Friends and long-time readers of this blog know I love 3D images, and have even dabbled in making them myself. I've also got a small collection of antique stereographs: pairs of photos printed on thick curved cardboard that are viewed through a stereoscope to show a 3D picture. They were early View-Masters. At the turn of the 20th Century, most well-appointed parlors were equipped with a viewer and a cabinet full of 3D cards to entertain guests, bringing the exotic wonders of the world to people who'd never see them otherwise.

I especially like stereographs of places I've been. It's fun (and a little spooky) to compare my modern experience of a place to that of someone a century ago. At an antiques fair yesterday, I found a card of Rheinstein Castle; since Karen and I just took a cruise up the Rhine River, I had to bring the card home and check whether we'd seen that castle ourselves.

And we did!

Here's the stereograph. The back of the card provides a little history of the castle, which Wikipedia expands upon. The card doesn't have a copyright date, but most of them were made in the late 19th Century. The fad died out in the 1910s, probably related to the coming of silent films.

Here's a modern photo of Rheinstein Castle taken from nearly the same vantage point. Some features are different, others are the same. It's interesting that the perilous-looking steps with curved railing that lead to the right-most tower look like they haven't changed in a century.

Our river boat chugged up the Rhine River in the distant background, which in fact is almost exactly where we were when I snapped this photo:

There, that hulking silhouette on the right bank.

There, that hulking silhouette on the right bank.

It's distant and dark, and unfortunately the only picture of this castle I got. Cropping and fiddling in Photoshop brings out a few more details that make it a definite match.

A century after Rheinstein Castle was visited by those two women lounging on a neighboring battlement, I was there too. Travel's good for making these connections with history--not just the centuries of history represented by the castle, but the century of tourism connecting those women to me. C'mon, that's cool!

Well, I think so.

I especially like stereographs of places I've been. It's fun (and a little spooky) to compare my modern experience of a place to that of someone a century ago. At an antiques fair yesterday, I found a card of Rheinstein Castle; since Karen and I just took a cruise up the Rhine River, I had to bring the card home and check whether we'd seen that castle ourselves.

And we did!

Here's the stereograph. The back of the card provides a little history of the castle, which Wikipedia expands upon. The card doesn't have a copyright date, but most of them were made in the late 19th Century. The fad died out in the 1910s, probably related to the coming of silent films.

Here's a modern photo of Rheinstein Castle taken from nearly the same vantage point. Some features are different, others are the same. It's interesting that the perilous-looking steps with curved railing that lead to the right-most tower look like they haven't changed in a century.

Our river boat chugged up the Rhine River in the distant background, which in fact is almost exactly where we were when I snapped this photo:

There, that hulking silhouette on the right bank.

There, that hulking silhouette on the right bank.It's distant and dark, and unfortunately the only picture of this castle I got. Cropping and fiddling in Photoshop brings out a few more details that make it a definite match.

A century after Rheinstein Castle was visited by those two women lounging on a neighboring battlement, I was there too. Travel's good for making these connections with history--not just the centuries of history represented by the castle, but the century of tourism connecting those women to me. C'mon, that's cool!

Well, I think so.

Published on June 12, 2017 10:06

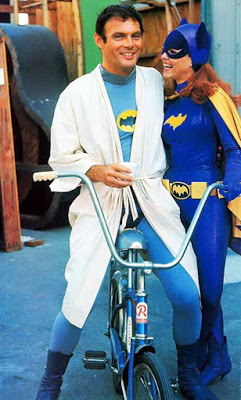

Adam West

I like this behind-the-scenes photo because it's a happy reminder that West wasn't Batman, he was a working actor who played Batman for a couple of years and rode a Raleigh stingray around the studio lot between scenes. And got to hug Yvonne Craig.

I like this behind-the-scenes photo because it's a happy reminder that West wasn't Batman, he was a working actor who played Batman for a couple of years and rode a Raleigh stingray around the studio lot between scenes. And got to hug Yvonne Craig. I had half a mind to write up something about Adam West, until NPR's Glen Weldon did it for me. It's worth a read.

The Batman '66 series hit me at just the right time--as it did Weldon, whose age must be within a year or two of mine--to make a difference. I also ran around the neighborhood with a cape, looking for crime to fight. It's no exaggeration to say that West's Batman, along with the same era's Kirk and Spock, and the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts, were as important to the development of my interests, personality, and approach to life as people who actually raised me.

West was an indispensable ingredient in my primordial soup.

I'll always treasure West's performance for one thing: I took it deadly seriously when I was a child and only realized it was a comedy when I was a teen, when I loved it all over again. I've never seen anything work on two levels as wonderfully as that. (Maybe "Peanuts," which is funny when you're a kid and melancholy when you're an adult.) For a long time, comic book readers and fans dismissed West's Batman for mocking the medium, and we still suffer through every newspaper headline about comics beginning with a "Pow!" and "Bam!" But the show was so smart and charming that opinion eventually turned, and West ended his life as a celebrated pop culture icon.

Well deserved, old chum.

Published on June 12, 2017 08:41

May 21, 2017

Hanging on the Hornet with Hyneman

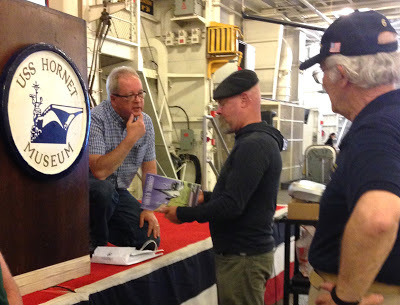

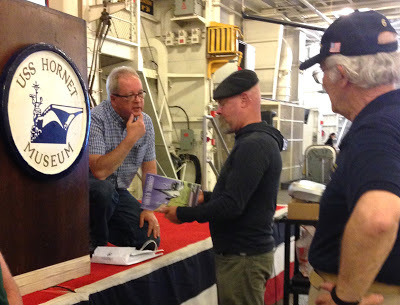

Chuck, Jamie and me.

Chuck, Jamie and me.Saturday was a special day for me, as I had the honor and pleasure of moderating a discussion of STEM (science technology engineering math) education at the USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum with docent Chuck Myers and TV Mythbuster Jamie Hyneman.

Jamie's been doing some prototyping for the U.S. Navy aboard the Hornet, in exchange for which they asked him to make an appearance.The opportunity to moderate came to me because the Hornet's STEM coordinator just had surgery and couldn't do it, the Hornet folks thought of me from other events I've done there, and maybe a bit because my daughter Laura is the museum's exhibition designer (although as I understand it, they approached her rather than the other way around).

Jamie, me, Chuck, and my daughter Laura before the event.

Jamie, me, Chuck, and my daughter Laura before the event. Me showing Jamie the venue and set-up. With its folding chairs, shared microphones and little projector screen, I think he thought it was cute.

Me showing Jamie the venue and set-up. With its folding chairs, shared microphones and little projector screen, I think he thought it was cute.Jamie, Chuck, the Hornet staff and I exchanged e-mails for weeks in advance of the event, figuring out what it would be. The idea was "STEM to Stern: How an Aircraft Carrier Works," and we settled on taking broad scientific concepts like transforming potential energy to kinetic energy, asking Jamie about his real-world experience air-dropping dummies and crashing trucks, and explaining how the concepts applied on the Hornet, e.g., catapulting airplanes off the flight deck. I prepared about three times as much material as I knew we'd use, Chuck prepared about five times as much, and Jamie showed up and told great stories.

Did you know that a TA-4J Skyhawk (which was not coincidentally parked next to our talk) weighing 24,500 pounds landing on a carrier at 135 knots has about the same kinetic energy as a fully loaded 18-wheel semi truck weighing 80,000 pounds going 85 miles per hour (about 26 million joules)? I do, because I did the math on that. Imagine a semi going from 85 mph to a complete stop in 2 seconds, which is what those planes did. Lots of cool accelerations and forces involved.

My view from the podium, with the Skyhawk behind. Chuck brought a table full of equipment and props, most of which we didn't get around to talking about but a lot of people looked at afterward. Leaning against the flag behind Chuck is a giant flat Fresnel lens I brought from home (because the Hornet used Fresnel lenses to guide aircraft coming in for a landing), which we didn't get around to discussing either.

My view from the podium, with the Skyhawk behind. Chuck brought a table full of equipment and props, most of which we didn't get around to talking about but a lot of people looked at afterward. Leaning against the flag behind Chuck is a giant flat Fresnel lens I brought from home (because the Hornet used Fresnel lenses to guide aircraft coming in for a landing), which we didn't get around to discussing either.Jamie turned out to be pretty much the guy you see on TV. I was afraid he'd be very taciturn, answering with "yup" and "nope," but he's chatty and articulate when aimed at a topic he's passionate about. He was downright eloquent talking about the importance of learning by doing and "getting your hands dirty." I said how much I admired the Mythbusters motto "Failure is always an option" and Jamie explained how the program evolved from being about demonstration to experimentation as they found that the best material often happened when things went wrong. Over lunch before the talk, he told a small group of us a terrific story about riding out a Caribbean hurricane in his sailboat.

Jamie was very pleasant and professional throughout, but the most engaged I saw him was before the talk, when we snuck him into an employee lounge as a makeshift green room, only to find a half dozen aircraft restorers eating lunch. Jamie immediately opened a 10-minute discussion with them about the challenges of painting steel, as if that were the first question that had popped into his head when he woke up that morning. It was neat.

Of course Jamie went home with copies of Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow and Mom's Cancer.

Of course Jamie went home with copies of Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow and Mom's Cancer.Jamie's given hundreds of talks like this. While he seemed very willing to roll with whatever we had in mind, he also had clear opinions about what would work best. We did whatever he said. It worked best.

I asked him privately if he missed Mythbusters. "No." He's very busy doing work he loves out of the public eye.

In all the focus on Jamie, I don't want to shortchange Chuck, who has been a docent on the Hornet for seven years and served as a bridge officer on her identical sister ship, the USS Yorktown. He's the best. Chuck really knows his ship, but more important for our purposes, has a talent for explaining what he knows without bogging down in mind-numbing detail. Chuck prepared more than 30 slides and we ended up using seven or eight of them, and I just wish we'd had another hour to really dive into some of the material he'd come ready to talk about.

The view from the back of the room. Deck. Whatever.

The view from the back of the room. Deck. Whatever.But Chuck and I both understood what we signed up for. My idea as moderator was to come prepared but flexible enough to let the conversation follow its own course. I didn't have a checklist of points I had to hit, but if the talk wandered to thermodynamics, I was ready to discuss steam turbines and exploding water heaters. People came to see Jamie; my job was to keep the ride between the ditches and otherwise stay out of the way.

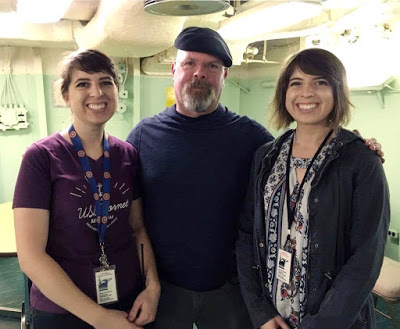

I think it all went great! We had a couple hundred people turn out, which helped raise money for the Hornet's STEM program. All in all, the day was a real life and career highlight for me. I appreciate the Hornet crew giving me a chance to do it.

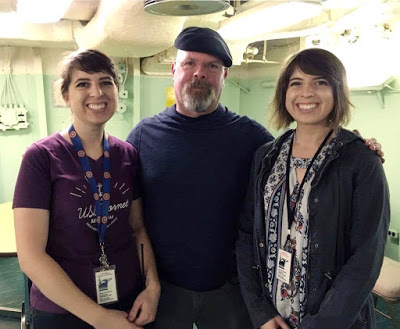

And I was glad I asked for this photo with my daughters Laura, the Hornet exhibitions designer, and Robin the archaeologist. They took most of the above photos for me and turned out to be excellent celebrity wranglers, escorting Jamie through the maze below decks.

And I was glad I asked for this photo with my daughters Laura, the Hornet exhibitions designer, and Robin the archaeologist. They took most of the above photos for me and turned out to be excellent celebrity wranglers, escorting Jamie through the maze below decks.

Published on May 21, 2017 09:30

Hanging on the Hornet with the Hyneman

Chuck, Jamie and me.

Chuck, Jamie and me.Saturday was a special day for me, as I had the honor and pleasure of moderating a discussion of STEM (science technology engineering math) education at the USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum with docent Chuck Myers and TV Mythbuster Jamie Hyneman.

Jamie's been doing some prototyping for the U.S. Navy aboard the Hornet, in exchange for which they asked him to make an appearance.The opportunity to moderate came to me because the Hornet's STEM coordinator just had surgery and couldn't do it, the Hornet folks thought of me from other events I've done there, and maybe a bit because my daughter Laura is their exhibition designer (although as I understand it, they approached her rather than the other way around).

Jamie, me, Chuck, and my daughter Laura before the event.

Jamie, me, Chuck, and my daughter Laura before the event. Me showing Jamie the venue and set-up. With its folding chairs, shared microphones and little projector screen, I think he thought it was cute.

Me showing Jamie the venue and set-up. With its folding chairs, shared microphones and little projector screen, I think he thought it was cute.Jamie, Chuck, the Hornet staff and I exchanged e-mails for weeks in advance of the event, figuring out what it would be. The idea was "STEM to Stern: How an Aircraft Carrier Works," and we settled on taking broad scientific concepts like transforming potential energy to kinetic energy, asking Jamie about his real-world experience air-dropping dummies and crashing trucks, and explaining how the concepts applied on the Hornet, e.g., catapulting airplanes off the flight deck. I prepared about three times as much material as I knew we'd use, Chuck prepared about five times as much, and Jamie showed up and told great stories.

Did you know that a TA-4J Skyhawk (which was not coincidentally parked next to our talk) weighing 24,500 pounds landing on a carrier at 135 knots has about the same kinetic energy as a fully loaded 18-wheel semi truck weighing 80,000 pounds going 85 miles per hour (about 26 million joules)? I do, because I did the math on that. Imagine a semi going from 85 mph to a complete stop in 2 seconds, which is what those planes did. Lots of cool accelerations and forces involved.

My view from the podium, with the Skyhawk behind. Chuck brought a table full of equipment and props, most of which we didn't get around to talking about but a lot of people looked at afterward. Leaning against the flag behind Chuck is a giant flat Fresnel lens I brought from home (because the Hornet used Fresnel lenses to guide aircraft coming in for a landing), which we didn't get around to discussing either.

My view from the podium, with the Skyhawk behind. Chuck brought a table full of equipment and props, most of which we didn't get around to talking about but a lot of people looked at afterward. Leaning against the flag behind Chuck is a giant flat Fresnel lens I brought from home (because the Hornet used Fresnel lenses to guide aircraft coming in for a landing), which we didn't get around to discussing either.Jamie turned out to be pretty much the guy you see on TV. I was afraid he'd be very taciturn, answering with "yup" and "nope," but he's actually chatty and articulate when you aim him at a topic he's passionate about. He was downright eloquent talking about the importance of learning by doing and "getting your hands dirty." I said how much I admired the Mythbusters motto "Failure is always an option" and Jamie explained how the program evolved from being about demonstration to experimentation as they found that the best material often happened when things went wrong. Over lunch before the talk, he told a small group of us a terrific story about riding out a Caribbean hurricane in his sailboat.

Jamie was very pleasant and professional throughout, but the most engaged I saw him was before the talk, when we snuck him into an employee lounge as a makeshift green room, only to find a half dozen aircraft restorers eating lunch. Jamie immediately opened a 10-minute discussion with them about the challenges of painting steel, as if that were the first question that had popped into his head when he woke up that morning. It was neat.

Of course Jamie went home with copies of Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow and Mom's Cancer.

Of course Jamie went home with copies of Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow and Mom's Cancer.Jamie's given hundreds of talks like this. While he seemed very willing to roll with whatever we had in mind, he also had clear opinions about what would work best. We did whatever he said. It worked best.

I asked him privately if he missed Mythbusters. "No." He's very busy doing work he loves out of the public eye.

In all the focus on Jamie, I don't want to shortchange Chuck, who has been a docent on the Hornet for seven years and served as an officer on her identical sister ship, the USS Yorktown. He's the best. Chuck really knows his ship, but more important for our purposes, has a talent for explaining what he knows without bogging down in mind-numbing detail. Chuck prepared more than 30 slides and we ended up using seven or eight of them, and I just wish we'd had another hour to really dive into some of the material he'd come ready to talk about.

The view from the back of the room. Deck. Whatever.

The view from the back of the room. Deck. Whatever.But Chuck and I both understood what we signed up for. My idea as moderator was to come prepared but flexible enough to let the conversation follow its own course. I didn't have a checklist of points to hit, but if the talk wandered to thermodynamics, I was ready to discuss steam turbines and exploding water heaters. People came to see Jamie; my job was to keep the ride between the ditches and otherwise stay out of the way.

I think it all went great! We had a couple hundred people turn out, which helped raise money for the Hornet's STEM program. All in all, the day was a real life and career highlight for me. I appreciate the Hornet crew giving me a chance to do it.

And I was glad I asked for this photo with my daughters Laura, the Hornet exhibitions designer, and Robin the archaeologist. They took most of the above photos for me and turned out to be excellent celebrity wranglers, escorting Jamie through the maze below decks.

And I was glad I asked for this photo with my daughters Laura, the Hornet exhibitions designer, and Robin the archaeologist. They took most of the above photos for me and turned out to be excellent celebrity wranglers, escorting Jamie through the maze below decks.

Published on May 21, 2017 09:30

May 15, 2017

The Last Mechanical Monster Lands at GoComics.com

One week from today, May 22, my Eisner-nominated webcomic The Last Mechanical Monster will begin appearing three days a week at GoComics.com.

I think that's pretty great.

I began posting the comic myself in 2013 and, 170 pages later, finished it in 2015. I was upfront about The Last Mechanical Monster being a "work in progress"--it said so right in each page's header--which in practice meant it was almost all black-and-white art. I also used the opportunity to solicit readers' suggestions and feedback, and used some of it.

Since then, I've colored the entire thing, and was honestly stunned by what a big difference it made. It really reads to me like a whole new story.

Now GoComics.com will offer it to a potentially much larger audience than I ever reached on my own.

GoComics is the online arm of Andrews McMeel Universal, which syndicates most of the biggest and best comic strips and newspaper features in the world. Peanuts, Doonesbury, Garfield, Pearls Before Swine, and Dear Abby are all theirs. To be clear, Last Mechanical Monster will not be in newspapers, only online. That still means thousands of potential new eyeballs. CoComics readers can subscribe to a personalized list of comics via either a free or premium membership. I might even earn a few bucks if I get a lot of subscribers, and it's easy to sign up for a free account (*ahem*). If it does really well . . . who knows?

GoComics readers familiar with my original story will notice one change right away. My first version made no secret that it was a sequel to the great 1941 Fleischer Studios "Superman" cartoon titled "The Mechanical Monsters." Those shorts have long been in the public domain, so while I obviously couldn't use Superman in my new material, I felt legally and ethically free to retell the old cartoon's story in an opening preface. Well, my editor at Andrews McMeel Universal was understandably leery of that, so the comic starts with a new two-page preface scrubbed of anything Super. Honestly? I think it works better than the original.

A few things about doing The Last Mechanical Monster surprised me. I set out thinking of it as a palate-cleanser--a light little story about an old man and his giant robot that didn't demand of me the angst of Mom's Cancer or even the prodigious research of Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? I did it because it was an idea I'd kicked around for a long time that sounded like fun, and I needed to remind myself that comics could--and often should--be fun.

And it was! Once I got on the right track (I've explained before how I spent many months writing and penciling more than 100 pages before realizing I wasn't telling the story I wanted to tell and started over from scratch, literally on the backs of the pages I'd already drawn), The Last Mechanical Monster was a hoot!

But y'know, that thing happened where the characters became kind of real to me, I felt bad when I made bad things happen to them, and sometimes they told me themselves what they wanted to do next. I found deeper themes about loss and legacy that struck a chord with me. When I finished the last page, a genuine sadness settled over me for days because I wouldn't be spending any more time with Sparky, Lillian, Helen, Chip and Ted. I missed them.

But y'know, that thing happened where the characters became kind of real to me, I felt bad when I made bad things happen to them, and sometimes they told me themselves what they wanted to do next. I found deeper themes about loss and legacy that struck a chord with me. When I finished the last page, a genuine sadness settled over me for days because I wouldn't be spending any more time with Sparky, Lillian, Helen, Chip and Ted. I missed them.Another surprise was how deeply some readers got involved with and even moved by the story. That comes with the territory when you do comics about illness or even Space Age history, but I honestly didn't expect anybody to really care about my giant robot comic. Yet some did. I had a wonderful correspondence with a man whose father had fallen into depression when his wife died, and my comic helped him climb out of it. The father sent me a song he composed, accompanying himself on the accordion, that makes me smile every time it comes around on my playlist.

Who knew?

So this is a cool deal. Thanks to Shena Wolf and John Glynn at Andrews McMeel Universal. I hope you'll check it out.

In a stroke of good timing, a guy named David Ely is trying to splice together the definitive versions of the Fleischer "Superman" cartoons. They've been in bad shape for decades; Warners did a terrific digital restoration a few years ago but inexplicably introduced some errors. By combining the best of several different versions, David's trying to do the ultimate restoration. Here's his take on "The Mechanical Monsters," some of the most gorgeous animation ever done in the history of the medium, which has nothing whatsoever to do with my "Last Mechanical Monster." Enjoy it.

Published on May 15, 2017 02:00

April 17, 2017

Enter the THIRD Dimension-n-n-n-n-n!

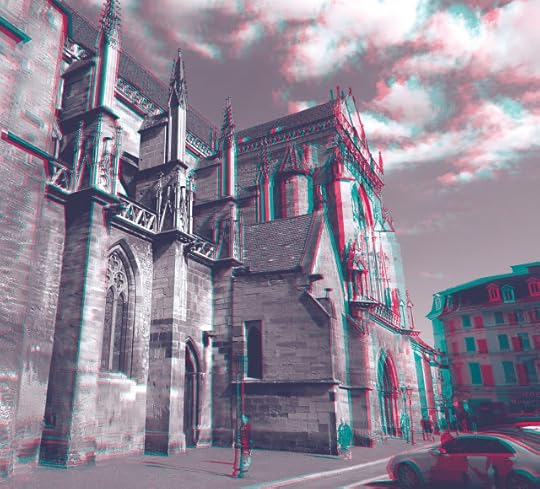

A couple of posts ago, I concluded my Rhine River Cruise trip report with a three-dimensional photo of the Strasbourg Cathedral (above). I shot more photo sequences on that trip intending to make 3D pics ("anaglyphs") out of them, and put a few together this morning. You'll need old-school red-blue 3-D glasses to see them.

In theory, making 3D pics like this is easy. You need two views of the same scene taken from slightly different vantage points, in the same way your eyes provide depth perception by seeing the world from two slightly different angles a few inches apart. So what I do is snap a photo, take one step to the right or left, and snap the exact same view. To cover my bases, I sometimes took four or five shots in a row like that: shoot, scootch, shoot, scootch, etc.

You can do the same thing if you're in a vehicle moving horizontally past a scene--for instance, on a boat on a river! Take a shot, wait a second for the boat to move, take another shot: two views of the same scene from slightly different vantage points. (That's how NASA produces 3D photos of asteroids, comets, moons, and a lot of other space objects: take the first shot, fly by for a few more seconds or minutes, and take the second shot.)

Then in Photoshop ("duotone") you turn the right image transparent red, the left image transparent green-blue, overlap them, and faster than you can say "Holy House of Wax!" you've got a 3D photo.

In practice, I've found there's a lot of art involved in getting the angles, colors, and alignment just right to get a good 3D effect. Some of these work better than others.

There are many other approaches to making 3D pics. You can make stereoscopic images, like the old Viewmaters slides, which let you use full color. In theory, you could also make full-color red-blue anaglyphs by deleting all the non-red out of one picture, all the non-blue out of the other picture, and overlapping them like I do here. I haven't had much success with that unless the original colors are balanced just right, which most of the real world isn't.

Marksburg Castle. This is one of my less successful anaglyphs because I think there's too big a difference between the angles. Also, I shot them from the boat that was moving away from the castle in addition to past it, so there's some unwanted movement involved. Still, I think the 3D works.

Marksburg Castle. This is one of my less successful anaglyphs because I think there's too big a difference between the angles. Also, I shot them from the boat that was moving away from the castle in addition to past it, so there's some unwanted movement involved. Still, I think the 3D works.  A town along the Middle Rhine. There's also a big difference between these two angles, which gives the town a "cardboard cut-out" feel. But I like it.

A town along the Middle Rhine. There's also a big difference between these two angles, which gives the town a "cardboard cut-out" feel. But I like it.  A statue in the Cologne Cathedral. The upward angle gives it a nice depth of field, I think.

A statue in the Cologne Cathedral. The upward angle gives it a nice depth of field, I think.

Cathedral in Colmar. Notice how the lady walking by appears twice (by the lamp post and by the corner at center-right), as her position changed in the time it took me to shoot two pictures.

Cathedral in Colmar. Notice how the lady walking by appears twice (by the lamp post and by the corner at center-right), as her position changed in the time it took me to shoot two pictures. Finally, try this. It works by a technique called "free fusion" that was also used in those "Magic Eye" posters that were popular 20 years ago. Stare at the picture and relax your eyes--don't cross them--as if you're looking through your monitor. The left and right images may merge into a center one that pops into 3D. Some folks can do it and some can't (my wife Karen is convinced the Magic Eye posters were just a joke people played along with to make other people look foolish). With a bit of practice/exercise it gets easy.

Finally, try this. It works by a technique called "free fusion" that was also used in those "Magic Eye" posters that were popular 20 years ago. Stare at the picture and relax your eyes--don't cross them--as if you're looking through your monitor. The left and right images may merge into a center one that pops into 3D. Some folks can do it and some can't (my wife Karen is convinced the Magic Eye posters were just a joke people played along with to make other people look foolish). With a bit of practice/exercise it gets easy.

Published on April 17, 2017 10:35

April 7, 2017

A Matter of Perspective

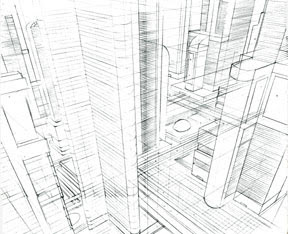

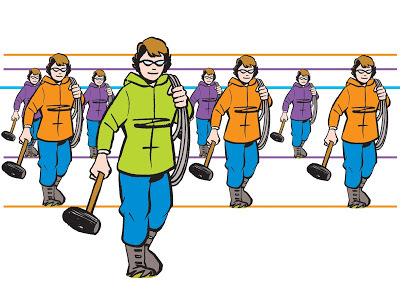

Three-point perspective I did for "Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow?"

Three-point perspective I did for "Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow?"I see a lot of artists complain that drawing in perspective is hard. I don't understand that. It's one of the first things they teach in middle school art class, and mastering it should be as fundamental to any artist as using a hammer is to a carpenter. Whenever a drawing isn't "working" for me, it's often because I haven't thought through its perspective; once I do that, the composition fixes itself.

Granting that different brains work in different ways, if you can draw a straight "horizon line" across the page and set up one, two or three "vanishing points," depending on the effect you want, the rest is drawing simple straight lines. There are a lot of lessons online and elsewhere about how to do that, and this isn't one of them.

Instead, this is a tip to share something I did this morning that, it occurred to me, might not be common knowledge.

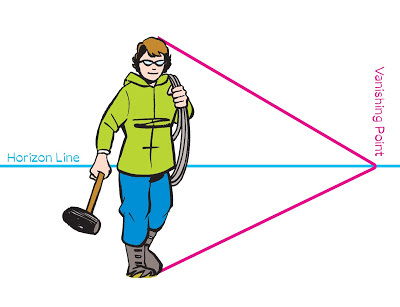

The standard technique for drawing perspective is to establish a horizon line and vanishing point:

The horizon line is literally that: the line that divides earth from sky. Then, assuming other figures are the same height as the first, fitting them within those perspective lines will make them all look the same size.

The same technique works for telephone poles, railroad ties, whatever you've got. But, as I said, this morning I did something I often do but haven't seen written up in the usual tutorials. I do it backwards.

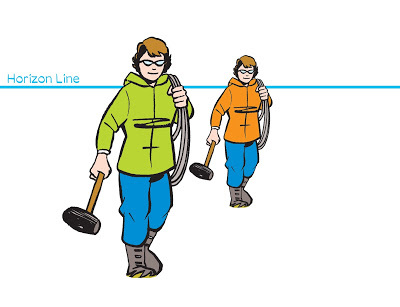

Let's say that, for whatever reason--maybe there's a caption box in the way, maybe you just like the composition--you want to arrange the figures in some arbitrary way:

To complete the drawing so that those figures make sense--to make it clear that neither is a giant or a dwarf--I want to find the horizon line. No problem. The key is this: assuming your figures are the same height, the horizon line hits at whatever parts of their bodies are level with each other.

For the drawing above, their shoulders are at the same level, so that's where I put the horizon line.

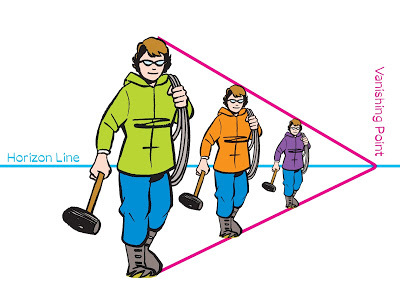

Find a vanishing point by drawing a line from the tops of their heads through the horizon line, and carry on from there. In particular, other figures that are the same height will fit within the same perspective lines, and all their shoulders will hit the horizon line, too!

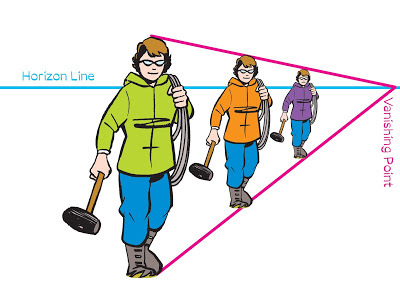

This may not seem very useful. How often would you want to draw a column of people lined up like telephone poles? Ah! Once you've figured out how large the figures look at different distances, then all figures at that distance (again, assuming they're supposed to be the same height) will be that size. Here I've drawn orange lines marking the height of the orange-coated figure, and purple lines marking the height of the purple-coated figure.

Once you know your horizon line and vanishing point(s), you can put your people anywhere, then create a world of railroad ties, telephone poles, buildings, trees, roads, earth and sky for them to live in. (And look at how all their shoulders line up with the horizon!)

Tuck that away, maybe my back-asswards perspective cheat will be useful someday.

Published on April 07, 2017 10:40

Brian Fies's Blog

- Brian Fies's profile

- 64 followers

Brian Fies isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.