Max Griffin's Blog, page 6

September 16, 2022

To Trope Or Not To Trope

Trope. Other than an obscure word, what is it? The dictionary says it’s a figurative or metaphorical use of a word or expression. If that’s all it is, why think about it at all? Well, that’s because a trope is much more than the dictionary definition. In fact, tropes are everywhere.

For example, book covers often include visual tropes, making science fiction, romance, and detective novels among others recognizable to their readers. The cape is a superhero trope. The sidekick has a been a trope since Cervantes and Don Quixote. Bad guys wearing black is trope. A red tunic in Star Trek is a trope—it tells us the unfortunate crew member will die. The twelve-chord-progression is a trope in blues music, and the do-wop progression is a trope of fifties pop. Salvador Dali’s melted clocks are a trope in his paintings, representing time devouring itself and everything else. Teenagers making bad decisions in horror stories is another familiar trope.

Tropes are ubiquitous, and in all artistic media. They’re even in non-artistic media, like political oratory where folksy stories are a trope to establish the common touch.

Tropes involve more than just symbols and metaphor, or even handy things like metonymy, as in writing “Hollywood” as a substitute for “the US film industry.” The observant reader will notice I just used a synecdoche by describing metonymy as “handy.” Okay, my proclivity for polysyllabic elucidation is showing again. That’s one of my personal tropes.

The point is that tropes are familiar things. You don’t need fancy words to understand them. They are a big part of how we communicate, and you almost certainly already use them.

A trope is simply a common convention that gets used often enough that people recognize it. That’s it. Nothing hard in that.

Tropes are ways that writers can reveal things about plot and character by applying the familiar in a new or unexpected way. The website TV-Tropes has hundreds of examples. There’s the “kill-the-dog” trope, for example, where the bad guy kills a puppy, establishing just how evil he is. That’s different from the “shoot-the-dog” trope, where a good guy makes a difficult moral choice, like shooting Old Yeller to spare him a horrible death from rabies. Then there’s the “pet-the-dog” trope showing a bad guy who can pet a dog isn’t so bad after all, similar to the “even-bad-guys-love-their-mommas” trope. The idea is that specific, familiar situations and actions reveal things about character and plot. What makes TV-Tropes website so useful is that it’s a vast compendium of clever tropes for achieving various ends.

Tropes are not cliches, or at least not necessarily. For example, a story using the it-came-from-space trope, where a calamity arriving from outer space threatens Earth, could involve new ideas, as, for example, in Lucifer’s Hammer by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. Or it could be a hopelessly cliched and scientifically impossible mess, like the recent Moonfall. Tropes are most useful when they subconsciously act on the audience, or when their application involves some unexpected twist. To be effective, tropes need your creativity and originality in order to be fresh.

Tropes are also different from archetypes, although an archetype can be a kind of trope. Tropes are about people, actions, things, situations, and so on that appear in life, in fiction, and in history. Tropes often include personality and cultural context. Archetypes usually refer to the role a character plays in a story, such as mentor, damsel-in-distress, or sidekick. Archetypes tend to be general, while tropes are particular. Hercules of myth is an archetype; Hollywood Hercules, with bulging muscles and a loin cloth, is a trope.

What are my favorite tropes, other than using big words? Well, one is the “AM-radio-reveals-all” trope, where the music the character listens to on the car radio foreshadows plot. If they’re listening to the Charlie Daniels Band’s “The Night the Devil Went Down to Georgia,” you can bet the story will involve demons of some kind. On the other hand, John Denver’s “Country Roads” sets a different expectation. If the radio plays both, that sets up unresolved tension, suggesting we’re not really on the road to rural paradise.

The ticking clock is another favorite trope. It establishes a deadline and thus creates tension. This trope appears everywhere in cinema, from Speed to almost any James Bond flick. Any deadline serves as a ticking clock, so midnight in most versions of Cinderella acts as a ticking clock. Michael Connely’s detective novels often cite the 48-hour for solviing homocides, another example of the ticking clock.

There’s a famous Hitchcock discussion of the ticking clock where he contrasts tension and shock. Some use this to argue that tension is superior to shock, but that’s not what the master said. In fact, he said “the bomb must never go off.” If Hitchcock had never shocked his audience, his movies would be a sequence of false alarms. In fact, he was quite willing to shock his audience—the shower scene from Psycho is a trope all by itself because of its shock value. That scene is so famous, it’s even appeared in The Simpsons.

For another trope, consider the ending of North By Northwest, which shows the train entering a tunnel as a metaphor for an implied tryst between Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint. The tunnel-of-love is a well-established trope, although I wonder how many viewers in the 1950s were consciously aware of it.

Teasers and queries are a place where tropes can be helpful. Whether it’s the “can’t-live-with-them-can’t-live-without-them” trope in a romance novel, or the “hero-with-a-thousand-faces” trope of the adventure novel, or the “defective-detective” trope seen in the noir detective novels such as the works of Dashiell Hammett, tropes can provide quick signposts to potential readers and editors about the novel’s plot.

The point is that tropes are everywhere and you can’t avoid them. So, the answer to the question, “To Trope Or Not To Trope” is that you don’t have a choice: you’re already using them. But tropes are like anchors. They can weigh down a story if used thoughtlessly, or they can deepen the reader’s engagement with your fictional world by providing an anchor to the familar.

Tropes can be rainbows leading to a pot of gold, or torpedos that sink your story. Since you can’t avoid them, use the power of tropes to free your creativity and follow that rainbow. Who knows, maybe there really is gold at the end.

References

Jeni Chappelle posted this insightful thread on twitter which inspired this newsletter.

If you’re interested in big-words-as-tropes, see Wikipedia

I wound up in a sink-hole listening to musical tropes, so I’ll share some of those here..

You can hear the twelve bar blues chord progression here. In the Mood by Glenn Miller, the theme to Petticoat Junction, and Tutti Frutti by Little Richard all use this progression.

The fifties do-wop progression is here Examples are Roy Orbison’s Pretty Woman and Sh-Boom by the Chords.

The falling bass progression is another trope that appears lots of places, including Bach. Examples from pop music include Procul Harem’s A Whiter Shade of Pale and Jim Croce’s Time In a Bottle. You can really hear the descending baseline in the opening measures in these examples.

Different chord progressions induce different moods. See here for a discussion by a composer of scores for movies and video games.

The post To Trope Or Not To Trope first appeared on Max Griffin.

August 21, 2022

It Takes a Detective

I confess. I love mysteries and I love science fiction. So, it’s natural that I’d love novels that blend the two. In particular, I’ve enjoyed my friend Alex Morgan‘s series of Psionic Detective novels. In fact, I enjoyed them so much that I suggested in January that we collaborate on one. We both had so much fun that we wrote another, then another. We’re now on our fourth.

For me, that’s an amazing pace—three complete, 60,000+ word novels in six months. One reason is that my coauthor is amazing. His considerable skills at plotting and characterization easily chop my own thinking time in half, if not by more. The fact that we’re having fun is, of course, another reason. It helps that we also usually start with some real-life case as the generic basis for the crime. Then we more or less alternate writing chapters. That means there’s that guy at the other end, tapping his foot, waiting for the next chapter. That implicit deadline adds motivation, even though we both have other things to do and often there are lags in chapters. The pressure is all imaginary, but it’s still real.

There’s another, more basic reason why these go faster, though: the basic story arc is already set. There’s a murder. Someone discovers it. Our intrepid Psionic Corps detective gets involved, and his skills play a roll in the investigation. The investigation turns into an adventure, and he eventually solves the crime. In the ones Alex and I have written together, the Psionic Detective has a regular guy for sidekick, and I usually write the chapters in that are in character’s point of view.

This formula is just a variation of the tried-and-true detective novel which has been around since April, 1841 when the genre was invented.

It’s not common that one can so precisely date when a genre was born, but in this case it’s clear. One story published that year included the following elements:

A crime is committedAn eccentric detective investigatesThis detective appers in a series of subsequent storiesThe detective has a non-eccentric sidekick (an everyman)The crime occurs in an urban settingThe detective has a disdain for law enforcementThe story fictionalizes a real-life caseThe readers have the same clues as the detective and so could theoretically solve the caseNotwithstanding knowing all the clues, the detective’s revelation of the criminal is a surpriseThe crime occures in a locked roomThis set of elements had never before occurred in one piece of fiction. In fact, the “locked room” concept, where the crime occurred in a room locked from the inside, first appeared in this story and has since devolved into an entire sub-genre. The story, of course, is The Murders in the Rue Morgue, and the author is Edgar Allen Poe.

Not only is this the first detective story, it established the foundation for all subsequent such stories. An important feature is the surprise revelation of WhoDunIt–in the case of Murders, it’s is an orangutan. This story and its killer are so iconic that they’ve even been parodied in a TV sitcom. See Retirement is Murder, the second episode of season twelve of Frasier. Here, the eponymous doctor hilariously “solves” one of Martin’s open cases by announcing the monkey did it.

So far, the stories Alex and I have written have included all of these basic elements except the locked room. To be sure, there’s a different detective in each story, but they are all outsiders, members of the elite, and sometimes despised, Psionic Corps.

The perceptive reader will recognize Sherlock Holmes uses the same elements. Even Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason has all of these features, with Paul Drake serving as the sidekick. Both of these classic heroes also have a disdain for law enforcement, which is often corrupt and almost always incompetent. Alex’s Psionic Detectives are part of law enforcement, but their eccentricity—namely their psionic talents—makes them outsiders and regular law enforcement skeptics.

The detective novel has endured for all this time for several reasons. For one thing, it’s adaptable. Arthur Conan Doyle made the investigations into adventures and his detective relatable, both improvements and additions to Poe’s model. There are other examples of outsider detectives, including Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, Agatha Christys’ Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot , and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. Each of these are unique, and each author added innovations to the genre. For example, Christy invented “cozy mysteries,” puzzle stories often set in the English countryside. In The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Mikael Blomkvist added the Swedish countryside to the settings.

The genre has diversified in other ways, too, to include for example gay detectives (Michael Nava’s Henry Rios) and African-American detectives (Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins). Each detective shares a certain alienation from broader society, letting them stand outside and analyze from afar. The various sidekicks anchor the stories in the real world with their everyman universality.

The story arcs have morphed over time, too. Jeff Lindsay’s Deeply Dreaming Dexter features a blood-splatter CSI detective who is also a serial killer. Talk about an outsider! This novel, and later ones in the series, are both police procedurals and moral adventures, where Dexter chooses his victims based on the failings of the criminal justice system.

But if the story arcs are all fundamentally the same, why do people keep coming back to them? Well, in the first place, not all the story arcs are the same—just the best-selling ones. But that’s for another essay. What almost all detective novels do have in common is that the detective solves the crime. Poe’s Auguste Dupin and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes use reason and evidence to outsmart the criminal. The detective novel is a contest between the criminal and the detective.

A key feature that Poe innovated is that the story is honest with the reader, in that the reader knows exactly the same evidence as the detective. All of it, including the evidence that, despite appearances, doesn’t bear on the crime. In The Hounds of the Baskervilles, it’s not even explicit evidence, but rather the lack of it, namely that the dog did not bark, that solves the crime. This makes the detective story also a contest between the reader and the detective.

Finally, underpinning these detective mysteries is an optimistic, almost romantic, view that we can make sense of the world through reason, deduction, and logic. The world may seem to be a strange and scary place, full of disorder and criminality, but in solving the crime, the detective replaces chaos with order and returns the world to its normal state. Even in the noir sub-genre, where the normal world is irredeemably filled with chaos and crime, the detective still applies evidence and deduction, along with a willingness to be endlessly be beaten up, to solve the crime.

The main reason the genre has survived all this time, I think, is its uriversality. Originally, detectives were mostly white, mostly English or American, and all male. But now there are Japanese detectives, female detectives, gay detectives, even serial killer detectives. It takes a detective, an outsider, to solve the crime and, in doing so, to make sense of a frightening and often hostile universe. Jim Rockford of the Rockford Files is a model for the modern detective: a steadfast outsider, a good guy, relatable and common, at odds with a corrupt and indifferent world. Like Sir Thomas More, the detective is a character for all seasons.

The post It Takes a Detective first appeared on Max Griffin.

August 13, 2022

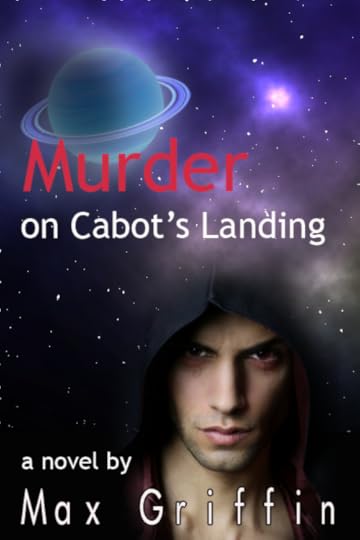

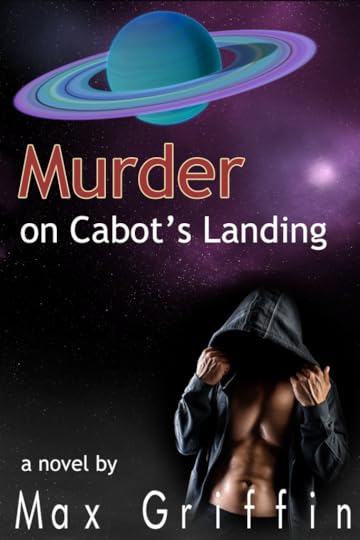

Evolution of Cover Doodles

I’ve spent some time this week working on doodles for a cover to my current work-in-progress.

This novel started out as a locked-room mystery set in the 31st century, kind of Agatha Christy meets The Shining. It’s evolved from that to add a touch of Robert Ludlum and the Bourne series, not that I write as well as any of those authors. It’s also got a bit of Casablanca-style romance between the two main characters.

Eventually, I’ll finish writing this and my publisher will want ideas for a cover, so I figured, why not give it a shot? A professional artist will do better than my Photoshop doodles, but I can give them an idea of how I think a cover might look.

This has gone through several of iterations. Initially, I thought it might be something like this:

[image error]First DoodleI didn’t like the fonts on this, and thought maybe adding rings to the planet might help. I also wanted a color picture of the guy, so I came up with this and shared it with some online friends.

People kind of liked it, but thought the planet looked cheesy. Also, almost everyone joined the “abs team,” i.e., the group who liked the picture of hooded guy with the great abs better than the handsome, but threatening guy.

That led to this version, which I think I like best. I’m not sure that the planet is better, but at least it’s shadowed in a way that’s more or less consistent with Mr. Abs. The planet casts a shadow on the rings, too, and its ambient glow is reduced on the shadowed side. I also made the sky a little more subdued than the prior version.

Anyway, I think I’ll stop doodling with covers and get back to writing. When I left them, my characters were under attack and fleeing through subterranean tunnels. I don’t think they’re going to like what happens next…

The post Evolution of Cover Doodles first appeared on Max Griffin.