Max Griffin's Blog, page 5

April 10, 2023

What’s for Dinner

Why should an author blog include stuff about cooking?

I know what you’re thinking. Who care’s what a fiction author is fixing for dinner? Well, I believe one reason people might come here to get to know the author as a person. I know that there’s a difference–a gap–between the author and the work, but I also know that my life experience informs what I write. Part of my daily life experience involves new adventures in the kitchen, so this is a chance for readers to see this side of me.

I hope to include at least one kitchen adventure every week. Even if there’s not much interest in this, it sounds like a fun thing to do, so I expect to stick with this for a few months at least.

This week’s dinner

Jump to Recipe

Sous Vide Pork chops

Pan Sauce

Blackberry Sauce

Su Vide Chops

For the uninitiated, sous vide means cooking in a water bath at a controlled, constant temperature. You put what you want to cook in a sealed plastic bag, dunk it in the bath, and leave it there for a couple of hours or so. For pork chops, for example, a water bath of 135 degrees Fahrenheit for two hours gives meat that’s cooked evenly all the way through, tender and juicy. It’s basically fool-proof, with no risk of the chops turning to dried-out, tasteless shoe leather.

For the uninitiated, sous vide means cooking in a water bath at a controlled, constant temperature. You put what you want to cook in a sealed plastic bag, dunk it in the bath, and leave it there for a couple of hours or so. For pork chops, for example, a water bath of 135 degrees Fahrenheit for two hours gives meat that’s cooked evenly all the way through, tender and juicy. It’s basically fool-proof, with no risk of the chops turning to dried-out, tasteless shoe leather.

It’s not totally fool-proof, of course. If you leave chops in the bath longer than four hours, the meat fibers will release most of their moisture, come apart, and get mushy. But that’s a two hour window, unlike the the seconds it takes to ruin chops when grilling, pan-frying, or baking in the oven. Sous vide is as close to fool-proof as you can get.

We’d already invested in a gizmo to vacuum seal food for freezing. With this handy doo-dad, you slip your food in a plastic bag and it sucks all the air out and then seals the bag closed. That helps prevent freezer burn and makes your frozen food last longer. It also creates the perfect container for sous vide cooking. You don’t have to have one of these devices, but it makes sous vide cooking even easier.

Once your chops–or whatever your cooking sous vide–are done, remove them from the plastic bag and dry them off. Even though the bag is sealed, in the hot water bath, water will seep through the plastic and get on your food. Since the next step is to sear the chops, you need to be sure they are dry.

You might be asking yourself why the “next step” is to sear the chops. I can hear you thinking, They’re already cooked. I just checked, and that’s what you said a couple of paragraphs ago.

It’s true, they are already cooked. But one of the things that makes meat taste good comes from searing the outer layer at a high temperature. This searing creates a Mailard Reaction, a chemical reaction between the natural sugars and proteins in the meat and gives it a brown texture. This “browning” step is essential to give the chop it’s final, flavorful taste.

I added herbs and spices after the sous vide bath. Some cooks recommend adding them to bag with the meat before cooking, and use the sous vide bath to infuse the flavors. I’ve tried this with fresh thyme and rosemary, but didn’t notice that it added flavors to the meat. It did add gloppy cooked herbs I had to dispose of before searing. It does seem to work if you rub some brown sugar and coriander on the meat prior to sealing in the sous vide bag, although tonight I waited to add these until right before searing the chops.

So, once you’ve got the chops out of their plastic bag, cooked through and through, and dried off, you put a couple of tablespoons of butter in a skillet and bring it to medium-high heat. This is also the time to rub your meat with herbs and spices. I used fresh thyme, ground coriander, ground ginger, and a touch of brown sugar. I also added minced garlic to skillet right before the chops. Anyway, stick the chops in the hot skillet for about a minute on each side, and they’ll be done to perfection. Just be sure the skillet is hot–give it a two or three minutes on the burner before you add the butter.

Pan Sauce

You’ll also be able create pan sauces with the juices and brown bits that wind up in the skillet. Once the chops are browned and out of the skillet, you can add chopped onions or shallots to the pan, a touch of olive oil, and then, after the onions are soft, de-glaze the pan with wine, Add some broth, herbs, garlic, mushrooms, maybe a touch of corn starch for thickening, and finish with more butter, and you’ve got a pan sauce. I used the pan sauce to top the Brussel’s sprouts I roasted in the oven, but you could use it as topping for the chops.

Blackberry Sauce

Yesterday, the grocery store had fresh blackberries on sale, and they looked so good I bought some. Now all I needed was to find a use for them. Impulse shopping has its downsides. I decided to fix a blackberry sauce for the pork chops. I found several recipes on the web, but constructed my own by smooching a few of them together. My idea was to get a sweet and savory sauce, kind of like a honey mustard pan sauce that’s a favorite of ours.

For the blackberry sauce, I used a basic recipe for a sauce you might use with pancakes or a dessert like cheesecake, and intended to add a touch of dijon mustard at the end. It turned out to not need it, so I left it out.

Take-aways

All right, so what have you learned so far? Well, you’ve learned that I’m a geek who likes gizmos, and who likes sciency-stuff when cooking, even if it does lead me to France and snooty French cooks. In fact, on my trips to France I’ve found that the myth of the snooty Frenchman is exactly that–a myth. Everyone I met while in France was warm and friendly, if a bit amused by my American walk and confused expression. Myth-busing is another favorite pastime.

Oh, and maybe you learned something about sous vide cooking. You’ve also learned I tend to lecture, er, I mean ramble.

For the rest of the meal, I roasted Brussels sprouts and topped them with the pan sauce I mentioned above.

Overall, this was a pretty easy meal. For cleanup, I had the skillet used to sear the chops and the saucepan used to make the blackberry sauce. I used a silicone cookie mat to line the cooking sheet that I used to roast the Brussels sprouts, so I only had to rinse that off–no real cleanup. Prep time was pretty minimal too. Maybe five minutes to trim and halve the Brussels sprouts. Cooking time added maybe fifteen minutes, most of it waiting for the sauces to thicken. I baked the sprouts while I seared the chops and made the pan sauce. We usually have a fruit salad with our meals, so add another ten minutes to cut up the fresh fruit–in this case, watermelon, strawberries, a pear, and a banana.

Overall, this was a pretty easy meal. For cleanup, I had the skillet used to sear the chops and the saucepan used to make the blackberry sauce. I used a silicone cookie mat to line the cooking sheet that I used to roast the Brussels sprouts, so I only had to rinse that off–no real cleanup. Prep time was pretty minimal too. Maybe five minutes to trim and halve the Brussels sprouts. Cooking time added maybe fifteen minutes, most of it waiting for the sauces to thicken. I baked the sprouts while I seared the chops and made the pan sauce. We usually have a fruit salad with our meals, so add another ten minutes to cut up the fresh fruit–in this case, watermelon, strawberries, a pear, and a banana.

PrintSous Vide Boneless Pork Chops#wprm-recipe-rating-0 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-full svg * { fill: #343434; }#wprm-recipe-rating-0 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-33 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-0-33); }#wprm-recipe-rating-0 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-50 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-0-50); }#wprm-recipe-rating-0 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-66 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-0-66); }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-0-33 stop { stop-color: #343434; }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-0-50 stop { stop-color: #343434; }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-0-66 stop { stop-color: #343434; }Course Main CoursePrep Time 5 minutesCook Time 1 hour 30 minutesServings 2EquipmentANOVA Sous Vide cookerIngredients2 Pork Chops, at least one inch in thickness1 TSP Ground Coriander1 TSP Ground Ginger1 TSP Ground Garlic1 TSP Sea salt2 TSP Brown SugarInstructionsPlace water in your tank and set your sous vide cooker to 135 degrees F for medium chops. I don't recommend higher settings. You can cook at 130 F for medium rare chops if that's your preference. See note below on food safety. Combine the herbs and spices in a small bowl.Lightly salt the chops on both sidesRub the chops all over with the spice mixture, massaging it into the meatSeal chops in separate plastic bags. You can use ordinary baggies for this step, but then you'll need to hang them from clips so less water seeps into the bag during the cooking process. If you have a vacuum sealer, you can just put the bags in water.You don't have to wait for the bath to reach temperature–you can just put the chops in right away. But be sure to get 90 minutes at full temperature.NotesYour chops can come directly from the freezer–just add thirty minutes to the cooking time after sealing them in their bag. In this case, you have to do the spice rub after they come out of the su vide bath and before searing. While I used two bags, it’s not really necessary. You could easily cook two or even four chops in a single bag. That’s not true for salmon and most fish, though. They will mush together at temperature, and so need separate bags.FDA standards suggest cooking pork to 145 F internal temperature in order to kill bacteria on the meat. It’s not necessary to reach this temperature with su vide cooking since the bacteria can’t live under the sustained 135 (or 130) degree heat of the su vide process. The FDA standard presumes the shorter cooking time of conventional methods, hence the higher recommended temperature. This is true for all meats cooked sous vide.

PrintPan Sauce#wprm-recipe-rating-1 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-full svg * { fill: #343434; }#wprm-recipe-rating-1 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-33 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-1-33); }#wprm-recipe-rating-1 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-50 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-1-50); }#wprm-recipe-rating-1 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-66 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-1-66); }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-1-33 stop { stop-color: #343434; }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-1-50 stop { stop-color: #343434; }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-1-66 stop { stop-color: #343434; }Prep Time 1 minuteCook Time 5 minutesEquipment1 SkilletIngredients2 Shallots, diced. A quarter cup of onions is a suitable substitute1 TBSP Olive oil1 Clove Garlic, minced1/4 C White wine1 C sliced mushrooms (I used porcini)1/2 C Chicken broth1 TSP fresh thyme (you can just put the entire sprig in the pan)2 TBSP Chicken Broth1 TBSP Brandy1 TBSP corn starch2 TBSP Butter1-2 TBSP Dijon mustard (optional)InstructionsThe idea for a pan sauce is that you have already seared your meat in the skillet, leaving behind juices and brown bits. Now, with your skillet under medium heat, add the shallots and olive oil. If lots of pan juices are in the skillet, skip the olive oil. You might even need to drain some of the juices, but be sure to keep the brown bits. You just need enough to cook the shallots without burning them.Stir and sweat the shallots for 3-4 minutes while they softenAdd the minced garlic and stir until it's fragrant–not more than 30 seconds or soAdd sliced mushrooms and cook until brown and they've lost most of their moistureDe-glaze the pan with the wine. Use a wooden spoon to scrape up the brown bits left over from browning the meat. They will dissolve in the wine and shallot mixture. The pan will sizzle when you add the wine! Fun!Now add the chicken broth, brandy, and whatever herbs you are using.For a thicker sauce, make the corn starch slurry and add to the mix. With the corn starch, it should begin to thicken almost at once. Without, it takes a few minutes longer and is generally less thick.Once thickened (with our without corn starch slurry), remove from heat and stir in butter. If your're adding mustard, this is the time to do it. The sauce thickens further as it cools, which is why the corn starch is only needed if you want a more gravy-like sauce. NotesI generally like a thicker sauce, so I use the corn starch slurry.Lots of meal kits use pan sauces because they are easy, don’t require having lots of ingredients on hand, and don”t involve getting another pan dirty. The kits usually use water mixed with a concentrated broth packet that’s included in the kit. You you can find these packets on Amazon if you want to replicate a meal kit recipe without the kit. Combining one of these packets with broth gives an extra intensity to the savory flavor of the sauce.

PrintBlackberry Sauce#wprm-recipe-rating-2 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-full svg * { fill: #343434; }#wprm-recipe-rating-2 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-33 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-2-33); }#wprm-recipe-rating-2 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-50 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-2-50); }#wprm-recipe-rating-2 .wprm-rating-star.wprm-rating-star-66 svg * { fill: url(#wprm-recipe-rating-2-66); }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-2-33 stop { stop-color: #343434; }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-2-50 stop { stop-color: #343434; }linearGradient#wprm-recipe-rating-2-66 stop { stop-color: #343434; }Easy Sweet and Savory Blackberry SauceCourse SaucePrep Time 5 minutesCook Time 15 minutesEquipment1 Small sauce panIngredients1 C Fresh blackberries1/4 C sugar or honey (I used Splenda)1 TSP Lemon juice 1 TSP Lemon zest1 TBSP Brandy1 TSP Chopped fresh rosemary2 TBSP Water1 TBSP CornstarchInstructionsAdd blackberries, sugar, chopped rosemary, brandy, and lemon zest and juice to sauce pan and bring to medium heat.Cook until it comes to a boil, stirring frequently. Boil for about ten minutes, until fruit breaks apart.Make a slurry of the water and corn starch and add to the boiling mixture.Continue at low boil until thickened–it should thicken almost at once. Once thickened, remove from heat. Refrigerate if you don't use it once. It should keep a couple of days at least.NotesBlackberries have seeds. If you don’t like the texture of the seeds, you can strain the sauce to take them out. This changes the recipe some, since you would need to strain the sauce after the fruit breaks down but before it thickens, and then return it to the stove, bring it back to a boil, and add the corn starch. Straining will also remove some of the other matter and tend to make the sauce more like a syrup. My preference is to leave them in and, in fact, to have a lumpy sauce that has the texture of preserves rather than jelly or syrup.

The post What’s for Dinner first appeared on Max Griffin.

April 3, 2023

A Grammarian’s Panegyric, Part Deux

NOTE: I see that I omitted this, my second Writing.Com “For Writer’s ” column, on grammar from my blog here. So I’m belatedly republishing it now. The previous “part deux” is now “part trois.”

I’m feeling moody today. It doesn’t help that TV seems to be nothing but re-runs. Heaven help us, even C-Span seems to be re-runs this week.

Well, since re-runs are everywhere, I’ll continue the trend and talk some more about verbs in this month’s newsletter since that was so popular last month. What? You didn’t like it? Be that as it may, that’s what you’re going to get. This month, I’m going to talk about a verb’s mood. When we’re done, you’ll know which of the following is correct and why.

If it wasn’t for your directions, I wouldn’t have gotten lost.

If it weren’t for your directions, I wouldn’t have gotten lost.

Sorry, that’s the best hook I can come up with.

Unless you’re a grammar geek, I bet you didn’t know verbs could be moody. Most of the time, a verb’s mood is indicative. That’s a nice, friendly mood where the verb expresses a fact or opinion or maybe asks a question about facts or opinions. “They voted again” is an example. “They voted stubbornly” is another, the former expressing a fact and the second an opinion. “How did they vote” is a third example, asking a question about a fact or opinion.

Other times verbs are in an imperative mood—they give a command. “Vote now,” is one example. However, imperative verbs are sometimes polite, as in “Please vote for me,” making a direct request, or “You may vote now,” granting permission. Note that the subject—“you”—is implied in these constructions. Other times, the subject might be given, as in “Kevin, stop that.” Note that “Kevin” is not the subject of this sentence–it’s a direct address.

About 99% of the time, verbs are either indicative or imperative. That other 1% is where it gets complicated. That’s also where it gets interesting, or at least confusing.

Consider phrases like “Heaven help us” or “be that as it may,” both of which appeared above. These are examples of a verb in a subjunctive mood. Subjunctive verbs are kind of bashful and don’t show up too often. When they do, they are often counterfactual, i.e., statements contrary to fact, or at least statements in the absence of fact. They speculate about things that might be true.

Subjunctive mood is uncommon, but we’re all familiar with it. For example, when Topol sings, “If I were a rich man…” in Fiddler on the Roof, he’s expressing a conjecture, i.e., he’s using “were” in subjunctive mood. If your landlord says, “That dog has to go,” she’s making a demand that the facts change, again subjunctive mood. If your boss says, “you need to take some time off,” that’s a suggestion about changing what you’re doing, so it’s again subjunctive.

Subjunctive moods come in three flavors, present, past, and past perfect. In almost all cases, subjunctive verbs pair with a form of the verb “to be.”

Present subjunctive is the easiest. If you write, “He recommends that they be prepared to vote at any time,” you’re using subjunctive present. Here, “be prepared” is not passive voice, which we covered last month. It’s part of a conjectural statement about unknown facts, hence subjunctive. The conjectural character is clear when compared with the sentence, “He is prepared to vote at any time,” which uses “prepared” to indicate a known state of being. Present subjective pairs the verb’s past tense with the present tense of “to be.”

Past subjunctive refers to something in the present or future (no one ever said grammar made sense), and always uses were regardless of how many subjects are involved, so the form is usually

if [subject] were [some state or action]

Thus, the sentence

If Sally were safe at home

conjectures that Sally is not at home and probably not safe. The word if often appears when using present subjunctive.

Admittedly, past subjunctive mood and imperative mood are easy to confuse. Consider, the two sentences at the start of this blog.

If it wasn’t for your directions, I wouldn’t have gotten lost.

If it weren’t for your directions, I wouldn’t have gotten lost.

The initial phrase is speculation, which means the verb should be subjunctive. Thus, the correct verb mood in the first clause is “weren’t” not “wasn’t” even though the subject, “it,” is singular. The second sentence is correct, the first is not. The mood in the second clause is left as an exercise for the reader.

Past perfect subjunctive adds yet another wrinkle. This is a conjectural statement that refers to something in the past. It uses the base verb’s past perfect form to refer to a counter-factual statement about the past. That’s clear, right?

For example

If only I had discussed past perfect tense first, this would make more sense.

We’ll talk about tense in a later post, but the above example shows past perfect subjunctive in action. The conjecture is about a past event, so we use the past perfect tense of “discuss;” “had discussed” indicates the past perfect subjunctive mood.

You can’t do past perfect mode without using the word “had.” That’s because you can’t do past perfect tense without “had.”

Sometimes you’ll see lists of words to avoid. These are almost always useful things, and often include non-specific adjectives like “large,” or “small,” or adverbs like “very.” But they sometimes also include words like “had.” It’s true that “had” can take the readers out of the here-and-now of ongoing events. That’s generally a bad idea. But sometimes, as in the use of subjunctive mood, you can’t avoid the word “had.” Your character might need to express regret, for example, and think, “If only I had not made that deal with Mephistopheles,” or “if only I had paid the insurance.”

That’s it for this month. If I decide to continue this series, a verb’s tense is up next. There’s twelve of these little things altogether. I don’t know about you, but just thinking about that makes me tense.

———————————

References

Paragraphs 5.123-5.127 of the Chicago Manual of Style

The post A Grammarian’s Panegyric, Part Deux first appeared on Max Griffin.

March 30, 2023

Writers’ Writing Rules

Ray Bradbury once said, “I don’t tell anyone how to write and no one tells me.” Yet, when pressed, he produced eight “rules” for successful authors.

In fact, if you Google your favorite author together with “writing rules,” you’re likely to discover links to that author’s answer to the question, “What are your rules for writing success?” Try it. I found rules that ran from two items for Robert Heinlein to twenty-four for Dashiell Hammett. That may say something about their respective styles, or maybe about how much self-reflection went into their writing, or something else. But still, there is some wisdom to be garnered by looking at these lists.

Not all Writing Rules are equal. Hammett’s, for example, are detailed, but in such a way that they apply primarily to detective novels of his era. Here’s his first rule, for example:

There was an automatic revolver, the Webley-Fosbery, made in England some years ago. The ordinary automatic pistol, however, is not a revolver. A pistol, to be a revolver, must have something on it that revolves.

This is interesting, but it’s not exactly advice. Of course, the point is that authors shouldn’t confuse a “pistol” with a “revolver.” More generally, authors should use technical terms in an accurate way. This more general form of the rule would include, for example, don’t confuse a unit of distance, like “parsec,” with a unit of time, like how long it takes to make a journey.

At the other end are Heinlein’s two rules.

You must write.

You must finish what you write

These certainly clear, and they apply to all authors and all genres. But they are so general as to be useless. For example, they don’t tell you how often or how much you should write, nor how to know you’ve finished. He eventually expanded this to five rules, including that you should never rewrite except to editorial order, but even that is not specific enough to be helpful. We also know, from the correspondence in Grumbles from the Grave, that he in fact did cut his manuscripts, which is certainly revision.

Tom Clancy proposed five rules.

Tell the story.

Writing is like golf.

Make pretend more than real.\

Writer’s block is unacceptable.

No one can take your dream away.

What? Like golf? What he means is that if you aspire to become a golfer, you practice. You might even take lessons from a pro. What you don’t do is read a book on how to play golf, or watch people playing golf, and then think you know the sport. You learn by doing. With respect to rule three, Clancy once opined, “The difference between fiction and reality? Fiction has to make sense.” That’s one way to make fiction more than real. For rule four, he clarifies that he means to write every day, whether you feel like it or not. Treat writing as a job. Finally, in rule five he says don’t let naysayers destroy your dreams. This is all good advice. Remember, J.K. Rowling went through twenty rejections for the first Harry Potter book before she found a publisher.

Hemingway proposed four rules.

Use short sentences.

Use short first paragraphs.

Use vigorous English.

Be positive, not negative.

These give clear instructions. They provide a basis for writing and revision. Anyone who has read Hemingway could deduce the first three rules. The last rule is the only one that might require some explanation. In rule four, he means describe what something is, not what it is not. He does not mean “be Pollyanna.”

The main problem with Hemmingway’s set of rules is that they are incomplete. Of course, any set of rules for writing is likely to share this flaw, but there are sets of rules that both serve as practical guides and are more comprehensive.

Kurt Vonnegut produced eight rules for short story authors, but they have value for novelists as well.

Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

Start as close to the end as possible.

Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

I’ve gotten particular inspiration from rules two, three, and four on this list. Write at least one character readers will cheer for, give every character a goal, and always advance character and plot. If you can follow these three rules, you’ve got a leg up on a good story.

Elmore Leonard also produced a succinct set of rules.

Never open a book with weather.

Avoid prologues.

Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said”…he admonished gravely.

Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.

Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

Again, these are clear rules, things you can bring to the page as you write.

Raymond Chandler gave us many amazing mysteries, but he also wrote advice on a what makes a good murder mystery:

It must be credibly motivated, both as to the original situation and the dénouement.

It must be technically sound as to the methods of murder and detection.

It must be realistic in character, setting and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world.

It must have a sound story value apart from the mystery element: i.e., the investigation itself must be an adventure worth reading.

It must have enough essential simplicity to be explained easily when the time comes.

It must baffle a reasonably intelligent reader.

The solution must seem inevitable once revealed.

It must not try to do everything at once. If it is a puzzle story operating in a rather cool, reasonable atmosphere, it cannot also be a violent adventure or a passionate romance.

It must punish the criminal in one way or another, not necessarily by operation of the law…. If the detective fails to resolve the consequences of the crime, the story is an unresolved chord and leaves irritation behind it.

It must be honest with the reader.

I like these rules because they easily generalize to other genres. For example, change a word here and there and you’ve got a guide for a good science fiction story.

Stephen King has given us twenty writing rules. These are also quite good, and replicate some of the advice above, especially about adverbs and leaving out the boring bits. King also takes the interesting view that writing is like archeology in that you are discovering your fictional world as you write, much like an archeologist discovers, potsherd by potsherd, a village in ancient Mesopotamia, Mongolia, or Mesoamerica.

Can we find truth in these writing rules? Sure. There’s the truth about how these individual authors view writing. There’s truth in that there is some agreement between this diverse set of authors, although agreement doesn’t necessarily imply a deeper truth. But there’s truth in the diversity of opinion, too. Each of these successful authors found their own truth. If you want to be successful, you have to find yours, too.

Isaac Newton wrote, “”If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” As you seek your own truth, you can build on the shoulders of these authors. Starting with their wisdom, find your own truth.

References

You can find the Writing Rules mentioned above in various sources. Here are the ones I used.

Ray Bradbury

Raymond Chandler

Tom Clancy

Dashiell Hammett

Robert Heinlein

Earnest Hemingway

Stephen King

Elmore Leonard

Kurt Vonnegut

The post Writers’ Writing Rules first appeared on Max Griffin.

The Allegory of the Cave

Nature doesn’t ask your permission; it doesn’t care about your wishes, or whether you like its laws or not. You’re obliged to accept it as it is, and consequently all its results as well.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, in The Dream of a Ridiculous Man

We have art so that we shall not die of reality.

–Friedrich Nietzsche

I like realism in literature. I want fiction to take me to places I can’t go and introduce me to people I’d never see in real life. Realism in literature replaces one kind of reality—the reality I live and breathe in—with another kind of reality, one I imagine in my head. It doesn’t matter if I visit that reality by reading a book, by going to a play, or by watching a movie. Fiction transports me to alternate realities. Fiction reveals endless possibilities.

But wait. If fiction is just imagination, it’s not really real, right? What’s real is what I can touch and taste, what my senses reveal. That’s reality, not words in a book or images on a screen.

Maybe. But maybe there’s more to it.

The allegoryImagine, if you will, prisoners in a cave facing a stone wall. Behind them, a fire flickers, but none of the prisoners turn to see it. Jailers might walk between the prisoners and the flames, but all the prisoners would see are shadows moving on the wall they face. The jailers might hold an object, say a book, and the prisoners, seeing the shadow of the book, would mistake the shadow for the thing itself.

Now imagine a prisoner turns and sees, in the dim flickering light, the flame, the jailers, and what they carry. Such a prisoner now sees more clearly, sees the book itself and not the mere shadow. The prisoner’s view of reality has just undergone a revolutionary change. Never again will shadows seem real.

Thus begins Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. We can learn many lessons from this simple story.

The prisoners have constructed a reality from the shadows they see on the stone wall. They might talk about it. They might even conjecture about the nature of a book from its shadow. In a sense, they are making observations, collecting data, and drawing conclusions. Just like a modern-day scientist. Well, they’re not solving differential equations or other complex math, so it’s not just like a modern day scientist, but the basic model of drawing conclusions from observations is there.

Another thing the allegory reveals that observations depend on the observer. As long as the prisoners face the wall, all they see are shadows. Once one of them turns around and sees the light, their frame of reference changes and the model of reality in their heads expands. The world itself doesn’t change, but how they think about it does.

But there’s more. The prisoner might spend many hours or days examining a book, touching it, turning its pages, examining the words scribed thereon. But if the prisoner doesn’t know how to read, the true form of the book will be forever hidden. The prisoners’ reality is still limited, not by what prisoners imagine but by what they can imagine.

In fact, our prisoner and the jailers are both in a dimly lit cave. Most aspects of reality are hidden from them. If they step outside, into the sunlight, what will they see? At first, the brilliant light might blind them, but eventually they’d see leaves of green, and red roses, too. They’d see our wonderful, wonderful world. No doubt they’d want to return to the cave to spread the news.

But back in the cave, the light is again dim. With eyes wide open from the sun, we can imagine they’d stumble. We can imagine the tales they would struggle to tell.

Back in the cave, prisoners and jailers alike still live in a shadowland. They might deduce the laws of the cave—how water flows and breezes blow—but oceans and thunderstorms are unknown and unimaginable. The prisoner who has seen the light of the outside would seem apostate, or even perhaps insane.

I sometimes think writers are like prisoners who have seen the light.

Why the allegory mattersThe Allegory of the Cave is powerful. It has had a profound influence on Western thought and the evolution of natural philosophy, first to natural law, and, eventually, to science as we know it today. There’s a direct line of descent from Plato’s forms, to Newton’s Principia, to Einstein’s General Relativity. Einstein famously said, “God does not play dice with the Unvierse,” because Einstein, like Dostoevsky, thought of the universe as a clockwork, with knowable laws and an ultimate certainty.

In fact, Einstein’s expressed disdain for dice was intended as a direct rebuttal to quantum mechanics and, in particular, to the Uncertainty Principle. Einstein believed in a deterministic reality and rejected the notion, implicit in quantum mechanics, that probability played any necessary role. In his view, as in Plato’s, nature at its most fundamental level is knowable, even if it’s implacable as Dostoevsky’s ridiculous man asserts. .

In the Allegory of the Cave, different frames of reference lead to different interpretations of reality. Our frame of reference colors how we think about the information our senses bring to us, whether that information is shadows on a stone wall or the dazzling garden outside the cave. As I walk through the real world, the one I can touch and smell, I carry with me a cultural frame of reference that includes Plato’s forms, Newton’s clockwork mechanics, Einstein riding an imaginary light beam, Bohr’s atom, and much more. On top of this cultural frame are even more basic intuitions, some of which may be genetic. The cause-and-effect sequence, for example, is doubtless ingrained in not only humans but other species as well. The same is probably true about the arrow time.

Beyond the allegorySo, what is really real? I believe that the universe is what it is, not what I wish it to be. I believe that we don’t live by bread alone, but that we unquestionably do live by bread. Reality acts on me: I stub my toe and it hurts; the sun warms my skin; I fall ill; I can die. But I also believe that what is really real is a deep mystery. Maybe we live in a simulation, like in The Matrix. If such a simulation is possible, then a convincing argument can be made that it’s virtually certain that we do live in a simulation. If that’s true, either nothing is real or everything is real.

But it gets worse. That cultural baggageheritage I mentioned? The one that influences how I think about the world around me, the one where effects follow from causes, where the arrow of time advances and never retreats, the one that abhors spooky action at a distance…that frame of reference? It’s probably wrong. All of it. If so, my walking, breathing reality, the one I think I live in, is as false as the prisoners’ shadows on the stone wall.

For you see, something called Bell’s Inequality has upended Einstein’s deterministic reality and, with it, Plato’s forms and all the rest. It turns out chance does rule, at least at the most basic level. The late, great physicist Richard Feynman once remarked that if you think you understand the surreal quantum world, you’re wrong. The universe is not only more mysterious than we imagine, it’s more mysterious than we can imagine.

The allegory and fictionWhat’s all this mean for the author of fiction? Well, fiction all happens in our head, whether we are authors or readers. One lesson from the Allegory of the Cave is that our personal reality happens in our heads as well, structured by a frame of rreference. Authors can use all that baggage, that shared frame of reference, to stimulate the readers’ imaginations and create compelling, believable worlds. In doing so, they can sometimes even reveal truth.

Hemingway said it best: “I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea and a real fish and real sharks. But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things. The hardest thing is to make something really true and sometimes truer than true.”

The post The Allegory of the Cave first appeared on Max Griffin.

February 28, 2023

Time, Realism, and Surrealism

All that we see or seem is but a dream.

–Edgar Allen Poe

I’ve been thinking about time, realism, and surrealism.

When an author writes in first person or in third person limited, the reader is inside the head of the point-of-view character. Being inside that character’s head means they’re also in the moment, in that character’s here-and-now . The readers’ imaginations are right there, experiencing the fictional world. As readers, we feel the chill of winter wind, the adrenalin rush that sends prickles down our spine, and the warmth of a lover’s embrace. It’s all happening in the moment, in the now, and in our heads.

We’re experiencing the “now” of the story. Our own, personal now, becomes enmeshed with the now of the story. In a true sense, we inhabit the story. At least, if the author is good enoiugh.

We experience our lives—and fiction—as a sequence of nows. That’s why flashbacks are a challenge in fiction, because they disrupt this natural and intuitive flow of here-and-nows. They run the risk of breaking the reader’s always tenous connection with the story.

Writers portray fictional characters in the here-and-now as they experience it. The best fiction cyrstalizes that here-and-now and brings it to life in the readers’ imaginations. This is true even if what the character experiences is surreal.

Consider, for one example, The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland. The story stays with Alice throughout. We know what she sees, smells, hears and otherwise senses. We know what she thinks and feels. We experience her here-and-now in Wonderland by being inside her head. So, Wonderland is an example of realism, right? But Wonderland, as the Cheshire Cat might purr, is a surreal place.

Kafka’s Metamorphosis is another example. He puts us in Grogor Samsa’s head and we experience his reality as he wakes one morning, transformed into a cockroach. What happens is surreal, but Kafka relentlessly portrays the protagonisit’s here-and-now. The style is realism, used to protray a sureal here-and-now.

There are countless other examples of fiction where the author stays in a character’s here-and-now, even though that here-and-now is surreal. Sometimes, it turns out the here-and-now is a dream. Sometimes other devices come into play, and the here-and-now isn’t even sequential in the normal way.

Time travel novels move the characters to the past or future, but they most often still use the point-of-view character as an anchor. In time travel novels, the point-of-view of the character provides a coherent sequence of here-and-nows. In “By His Bootstraps,” for example, Heinlein has a scene where the point-of-view character meets and argues with two future versions of himself. Subsequently, as he ages, he experiences the same scene as each of the later versions. As readers, we experience each scene with new eyes and ears, or at least older eyes and ears. I’d say this is Rashomon-like, except that Heinlein’s story predates the Kurosawa movie by ten years.

The same kind of thing happens in The Time Traveler’s Wife, or in David Gerrold’s marvelous The Man Who Folded Himself, or even in my own novel, Timekeepers.

Dreams are another kind of reality. They’re in our head, too, so they’re just as real as anything else. Surrealist fiction often uses dreams. Consider one of the most famous examples, The Wizard Of Oz, in which everything, including all the surreal elements of Oz, turn out to be a dream. For another exmaple in The Lathe of Heaven, the protagonist’s dreams become reality.

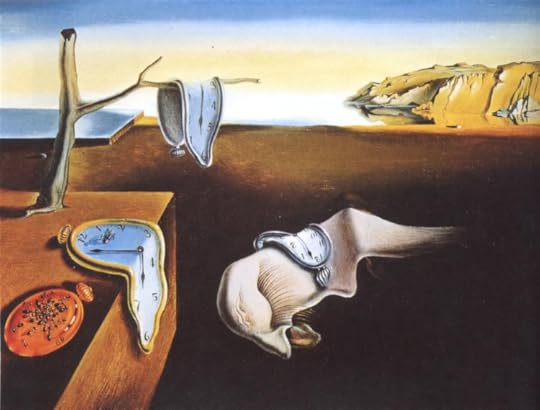

For an example of surrealism in the visual arts, consider Dali’s painting The Persistence of Memory which shows a surreal Jungian  vision of realty. Time loses meaning with the melting clocks. The monstrous creature draped across the center evokes nightmares. Ants devouring everything, symbolize decay. The painting depicts this vision of time and memory as fluid objects, imposed on the real world, i.e., the Catalan coast in the background.

vision of realty. Time loses meaning with the melting clocks. The monstrous creature draped across the center evokes nightmares. Ants devouring everything, symbolize decay. The painting depicts this vision of time and memory as fluid objects, imposed on the real world, i.e., the Catalan coast in the background.

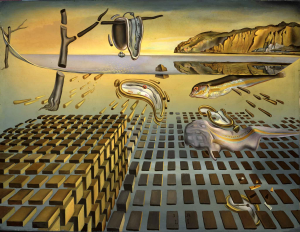

Even more interesting, though, is a later Dali painting, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, in which everything is disconneteced. The bottom is broken down into parts that flatten to nothingness. The Catalan coast becomes an unraveling page in the background. It’s as though atoms and quantum mechanics have replaced Jung in Dali’s portrayal of time and memory.

Even more interesting, though, is a later Dali painting, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, in which everything is disconneteced. The bottom is broken down into parts that flatten to nothingness. The Catalan coast becomes an unraveling page in the background. It’s as though atoms and quantum mechanics have replaced Jung in Dali’s portrayal of time and memory.

There’s a marvelous story by John Varley, “The Persistence of Vision,” that shows how vision and sound can distort our constnructed reality of the here-and-now. I’ve sometimes wondered if Dali’s paintings inspired this story. In any case, it’s worth reading.

Examples of surrealism abound in movies. One of my all-time favorite movies is David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive. Certainly, the Hollywood of that movie has many surreal elements–that’s true of the real Hollywood, as well. What’s less obvious is that the two major parts of the movie are out of order. The break occurs when Rebeka del Rio sings “Lloando,” a Spanish rendittion of the Roy Orbison classic “Crying.” Almost the entire first half of the movie shows Diane, played brilliantly by Naomi Watts, arriving and flourishing in LA. But there’s a quick flash in the opening moments, almost too fast to take in, that first shows a wizened Diane in a bleak apartment. What we’re seeing from that point forward until the “Lloroando” scene is a dream, how Diane wishes her time in LA might have gone. After Crying, we see the way her time in LA really went, all the way to the end with the wizened Diane again in her bleak apartment, all her fantasies dashed. Lynch directs the two segments with the camera’s unflinching, realistic eye, so the audience has only the barest clue of what’s really going on. A brilliant piece of realistic surreal cinema by one of America’s most talented auteurs.

But I digress.

We all live in many ‘nows.’ Some are in the past, some are in the still-to-be-experienced future, some are in the neverland of might-have-been. But wherever and whenever they are, they all are both real and the stuff of dreams. They arise in the fragile moment of a human breath, yet they are everlasting, from Big Bang to the heat-death of the multiverse and beyond.

All those nows, eternal and yet fleeting, are in our heads. All of them. Past, present, future, might-have-been, never-to-be, and fictional. All that we can know, see, or seem is right there, in our heads. And in our hearts, to be sure, but certainly in our minds and souls. That’s all and everything we can know, but surely it’s enough.

The post Time, Realism, and Surrealism first appeared on Max Griffin.

February 3, 2023

A Grammarian’s Panegyric Part Trois

Verbs are an author’s friend. They bring our characters to life. Verbs put them in motion, imbue them with traits, and describe their adventures. In particular, verbs inform us about actions, states, or occurrences. After all, every character has interesting attributes. My cat sleeps. My cat is asleep. My cat falls asleep.

Well, okay, some attributes are more interesting than others.

The tense of a verb informs us when the action, state, or occurrence took place. There are three basic tenses: past, present, and future. My cat slept. My cat sleeps. My cat will sleep. These are familiar and don’t need explanation.

Each of these tenses has a perfect form to indicate a more remote time for the action, state, or occurrence. Because the time in question is “more remote,” there’s an implicit or explicit reference time.

For example, for present perfect we might write I have just the cleaned floor when the cat knocks flour all over the place. The reference time is the present—when the cat makes the mess—and the cleaning happened right before this event, so we use present perfect. You form the present perfect tense by combining have or has with the primary past participle of the verb.

Past perfect is similar, except instead of have or has, it always combines had with the verb’s past participle. So, for example, I had just cleaned the floor when the cat dumped flour all over the place. My action—cleaning–is in the past, but it occurred right before the cat’s action—making a mess. Isn’t that way it always works with cats?

Similarly, future perfect denotes a time in the future but before some other future time. For example, By the time I’ve owned a cat a year, I will have cleaned up cat vomit over three hundred times. The point of time in the future is one year after I’ve acquired a cat, and the action involved is cleaning up vomit. Ah, the joys of owning those little balls of fur. Maybe I should have used this example instead: By the time I’ve owned my cat a year, he will have cuddled on my lap over a thousand times. There. The joys and sorrows of cat ownership in one paragraph.

Perfect tenses are especially relevant to fiction authors, who necessarily pay attention to the fictional present, the fictional past, and the fictional future.

When we write about the here-and-now for our characters, we almost always use past tense. Our earliest examples of stories, epics like Gilgamesh and The Iliad and The Odyssey, use the past tense to describe what happens to the characters. Later examples, from The Aeneid to the Poetic Edda, to Beowulf continue to use past tense to describe the here-and-now of the heroic protagonists. This tradition largely continues to this day, although masterpieces like Bleak House and Rabbit Run break with that tradition.

Most of the time, however, we write our fiction using the past tense to describe the here-and-now of our characters. In other words, the fictional present is the here-and-now of the characters, usually depicted using past tense relative to the readers. That means we must use past perfect to describe things that happened in the fictional past and future perfect to describe what will happen in the fictional future. For this reason, authors must master the grammatical nuances of the perfect tenses.

So far, we’ve considered six verb tenses: the three basic ones and the perfect versions of each. But each of these six have another version to reflect the difference between things completed and things ongoing. There’s a difference, for example, between I clean the floor and I am cleaning the floor. The first describes a point-in-time, while the second describes an ongoing action.

That gives us six new tenses, one for each of the six earlier tenses, for a total of twelve in all. These new tenses, which describe ongoing activities, are sometimes called continuous, progressive, or—just to be confusing—imperfect. Paragraph 1.35 of The Chicago Manual of Style calls them progressive, but admits that continuous is sometimes used. Continuous seems more descriptive to me, but take your pick.

To get the continuous tenses, use the appropriate form of be—past, present or future—with the present participle of the main verb. So, for example,

present continuous (he is cleaning the floor);present-perfect continuous (he has been cleaning the floor);past continuous (he was cleaning the floor);past-perfect continuous (he had been cleaning the floor);future continuous (he will be cleaning the floor); andfuture-perfect continuous (he will have been cleaning the floor)Again, the various perfect continuous tenses are important for the fictional author who is using (notice the continuous present tense) the past tense for the character’s here-and-now.

That’s it. Twelve tenses. Add these to the moods of a verb as we discussed last time, and you can see verbs are complex little fiends. Er, I mean, friends.

I think this will be my last excursion into grammar unless popular demand wants more. Like that’s going to happen. See you all next month with something new.

See also Part One and Part DeuxThe post A Grammarian’s Panegyric Part Trois first appeared on Max Griffin.

A Grammarian’s Panegyric Part Deux

Verbs are an author’s friend. They bring our characters to life. Verbs put them in motion, imbue them with traits, and describe their adventures. In particular, verbs inform us about actions, states, or occurrences. After all, every character has interesting attributes. My cat sleeps. My cat is asleep. My cat falls asleep.

Well, okay, some attributes are more interesting than others.

The tense of a verb informs us when the action, state, or occurrence took place. There are three basic tenses: past, present, and future. My cat slept. My cat sleeps. My cat will sleep. These are familiar and don’t need explanation.

Each of these tenses has a perfect form to indicate a more remote time for the action, state, or occurrence. Because the time in question is “more remote,” there’s an implicit or explicit reference time.

For example, for present perfect we might write I have just the cleaned floor when the cat knocks flour all over the place. The reference time is the present—when the cat makes the mess—and the cleaning happened right before this event, so we use present perfect. You form the present perfect tense by combining have or has with the primary past participle of the verb.

Past perfect is similar, except instead of have or has, it always combines had with the verb’s past participle. So, for example, I had just cleaned the floor when the cat dumped flour all over the place. My action—cleaning–is in the past, but it occurred right before the cat’s action—making a mess. Isn’t that way it always works with cats?

Similarly, future perfect denotes a time in the future but before some other future time. For example, By the time I’ve owned a cat a year, I will have cleaned up cat vomit over three hundred times. The point of time in the future is one year after I’ve acquired a cat, and the action involved is cleaning up vomit. Ah, the joys of owning those little balls of fur. Maybe I should have used this example instead: By the time I’ve owned my cat a year, he will have cuddled on my lap over a thousand times. There. The joys and sorrows of cat ownership in one paragraph.

Perfect tenses are especially relevant to fiction authors, who necessarily pay attention to the fictional present, the fictional past, and the fictional future.

When we write about the here-and-now for our characters, we almost always use past tense. Our earliest examples of stories, epics like Gilgamesh and The Iliad and The Odyssey, use the past tense to describe what happens to the characters. Later examples, from The Aeneid to the Poetic Edda, to Beowulf continue to use past tense to describe the here-and-now of the heroic protagonists. This tradition largely continues to this day, although masterpieces like Bleak House and Rabbit Run break with that tradition.

Most of the time, however, we write our fiction using the past tense to describe the here-and-now of our characters. In other words, the fictional present is the here-and-now of the characters, usually depicted using past tense relative to the readers. That means we must use past perfect to describe things that happened in the fictional past and future perfect to describe what will happen in the fictional future. For this reason, authors must master the grammatical nuances of the perfect tenses.

So far, we’ve considered six verb tenses: the three basic ones and the perfect versions of each. But each of these six have another version to reflect the difference between things completed and things ongoing. There’s a difference, for example, between I clean the floor and I am cleaning the floor. The first describes a point-in-time, while the second describes an ongoing action.

That gives us six new tenses, one for each of the six earlier tenses, for a total of twelve in all. These new tenses, which describe ongoing activities, are sometimes called continuous, progressive, or—just to be confusing—imperfect. Paragraph 1.35 of The Chicago Manual of Style calls them progressive, but admits that continuous is sometimes used. Continuous seems more descriptive to me, but take your pick.

To get the continuous tenses, use the appropriate form of be—past, present or future—with the present participle of the main verb. So, for example,

present continuous (he is cleaning the floor);

present-perfect continuous (he has been cleaning the floor);

past continuous (he was cleaning the floor);

past-perfect continuous (he had been cleaning the floor);

future continuous (he will be cleaning the floor); and

future-perfect continuous (he will have been cleaning the floor)

Again, the various perfect continuous tenses are important for the fictional author who is using (notice the continuous present tense) the past tense for the character’s here-and-now.

That’s it. Twelve tenses. Add these to the moods of a verb as we discussed last time, and you can see verbs are complex little fiends. Er, I mean, friends.

I think this will be my last excursion into grammar unless popular demand wants more. Like that’s going to happen. See you all next month with something new.

The post A Grammarian’s Panegyric Part Deux first appeared on Max Griffin.

December 6, 2022

A Grammarian’s Panegyric

In a prior life, one of my jobs was to draft academic policy. This was always fraught with peril, not over the policy but over alleged grammar errors. I recall one particularly nasty note accusing me of the sin of using a split infinitive. I had to look that one up, and was shocked to learn that a phrase like, “To boldly go where no man has gone before” was a split infinitive. The adverb “boldly” splits the infinitive “to go.”

Today, I’d probably avoid both the adverb and the generic use of “man” for “person,” but back then I was chastised. At least, until a colleague from the English Department pointed me to paragraph 5.108 of the Chicago Manual of Style, which states “Although from about 1850 to 1925 many grammarians stated otherwise, it is now widely acknowledged that adverbs sometimes justifiably separate the to from the principal verb.”

Ha! Take that, nasty-gram author!

Still, effective writing involves effective use of language, and that inevitably means understanding grammar. Take verbs, for example. A verb, any verb, has five properties: voice, mood, tense, person, and number. Verbs are conjugated to show these properties. Each of these, even the obvious ones like tense and person, have nuances. Paragraphs 5.117 through at least 5.155 of the Chicago Manual of Style deal with verbs. Each of the five verb properties have a place in the fiction author’s inventory, and it occured to me that it might be useful to have a newsletter devoted to each one.

At least, it seemed useful when I couldn’t think of anything else to write about this month, so here goes.

Chicago Manual of Style, 5.118: Active and passive voice. Voice shows whether the subject acts (active voice) or is acted on (passive voice)—that is, whether the subject performs or receives the action of the verb.

Consider the two sentences.

Marie slapped Sam. Sam was slapped by Marie.They describe the same event, but the subject of the verb changes. In both sentences, Marie is the actor and Sam receives the action, but the grammatical construction is different. Marie is the subject of the first sentence, while Sam is the subject of the second. The first sentence uses active voice, while the second uses passive, signaled by the helper verb “was” and the prepositional phrase, “by Marie,” identifying her as the actor. The grammar is simple enough, although CMOS drones on about progressive conjugations and other matters, the basics are pretty direct.

But it’s also more complicated than mere grammar.

In fiction, the author attends not only to voice but also to point of view. We want to put the readers inside the point-of-view character’s head. When this is successful, the readers become the author’s partner in imagining the fictional world. This active imagination then fills in the myriad incidental details that don’t make it to the page but nonetheless bring the scene to life. Activating the readers’ imaginations is one of the primary goals of point-of-view.

If we’re in Marie’s head, then the first sentence, the one using active voice, keeps the readers in her head. She’s acting on an element of the fictional world, namely Sam. Her action keeps the readers’ imaginations engaged and helps to keep them inside her head and thus inside the fictional world. In this case, the first sentence, with active voice, is superior to the second because it keeps the reader focused on Marie and her actions.

But suppose Sam is the point-of-view character and the readers are in his head. To be sure, the second sentence keeps the focus on Sam, but he’s not acting or even reacting. Instead, he’s passively receiving the action. This passivity gets transferred to the readers since they’re in his head. The result tends to deactivate the readers’ imaginations and distance them from the ongoing events in the here-and-now. So, the passive voice in the second sentence acts in a manner contrary to one of the main goals of point-of-view, namely inciting active readers.

Of course, in the real world, and hence in the fictional world, things happen that are beyond our control. It’s certainly possible that Sam might get slapped. The point here is that way to show that is not with passive voice, but rather by showing Sam’s reaction to being slapped. For example, we might write, “Marie slapped Sam and set his cheek on fire.” Marie’s acting, but now the focus shifts to Sam’s internal reaction, namely the sensation of being slapped, something only he can feel. This keeps us in his head and keeps the readers active. Better yet, the metaphor “fire” suggests an emotional response of anger as well as a physical one and stimulates the readers’ imaginations. Marie is still the actor in this sentence for both verbs—“slapped” and “set”—but now the readers are in Sam’s head, imagining both his sensations and emotions.

I’m a mathematician by training, and that peculiar heritage often clouds my thinking. It would be nice if language followed consistent rules, like Zermel-Frankel set theory, but the reality is that English is both irregular and evolving. To be sure, there are grammar rules, and they are often clear-cut, but they can be convoluted as well. I’ve learned over the years to rely on a guide like The Chicago Manual of Style when in doubt. It’s inexpensive to access online, and definitive. If you can’t afford the modest charge, online sources like the Purdue Owl are free and quite good.

Grammar is useful for both clarity and rigor. But grammar isn’t the whole story, or even an important part of it, as the above discussion on voice demonstrates. It’s showing your characters acting and reacting to the fictional world that brings your story to life. Grammar is no substitute for effective craft and artistic nuance. If you write with your heart but edit with your head, you’ll probably achieve a good balance.

Next month, I’ll tackle a verb’s mood. Unless I think of something more interesting.

The post A Grammarian’s Panegyric first appeared on Max Griffin.

November 13, 2022

It’s Axiomatic

When I retired, I decided to try my hand at writing fiction. I remember thinking, “How hard can this be?” I’d already written a couple of successful mathematics textbooks and published dozens of research papers. Novels were like textbooks, and short stories were like research monographs, right?

You can stop laughing now. Of course, that’s not right.

When I tried writing fiction, stories danced in my head, all fire and ice. But when I put them on the page, they turned to ashes and fog. I tried to imitate authors I liked, but while their stories were full of life and depth while mine were dead and flat. I now know that I was striving for the wrong things—and sometimes looking at the wrong authors!

When I wrote mathematics, my approach was holistic. I knew the conclusion—the QED at the end of the theorem. I knew the clever argument to get to that QED. I knew the readers’ goal, too: to understand the argument and the conclusion. I knew the content. I knew what the readers wanted. I knew what I wanted. QED.

The problem was, I didn’t know any of these things when I started writing fiction. Even worse, what I thought I knew was wrong.

But fortune smiled on me. Out of nowhere, a guy named Timm sent me a critique to a story I’d posted on Writing.Com. He was pretty scathing, but he gave me a reason for everything he said. I could see his comments made sense, so I revised the story. It was still pretty bad, but the revision was clearly better. That led to more reviews from Timm, and I reviewed him, too. Before long, he invited me to join a private writing group on the site, and several experienced and talented authors started to explain craft to me. I learned about point of view. They explained the difference between showing and telling and why it mattered. I learned about tension and pacing.

In short, I learned the building blocks of creating an effective story. To my mathematical mind, these were like learning the axioms and basic theorems of mathematics, the essential precursors for the textbooks and research papers I’d written. In mathematics, the techniques might involve obscurities like Zorn’s Lemma or the Banach-Alaoglu theorm. In fiction, they involve things like third person limited, the three-act play, free indirect discourse, scene/sequel pairings, and many other techniques. Learning the techniques opened my eyes as both a reader and a writer.

It made all the difference.

I still tend to write holistically. I’ve learned a lot about craft. Some of it is now even second nature to me. I still tend to think of “craft” as the foundation of fiction, like the axioms of mathematics. But craft and axioms are not the same thing. Not exactly, anyway. Craft is the accumulation of techniques that other authors have used effectively over the years. Free indirect discourse dates all the way back to Charlotte Bronte and Jane Eyre. The three-act play is even older, with roots in Greek drama. Dwight Swain first formulated the scene/sequel concept in 1965. Craft is continuously evolving, just like research mathematics.

Further, the author’s artistic goals determine how and why craft works. The fictional dream, the prevailing theory in commercial fiction, demands one sort of craft. But expressionist fiction has different goals. Kafka’s absurdist goals in The Metamorphosis are different from the realism of Hemingway in The Old Man and the Sea, and the authors’ choice of craft is correspondingly different. Waiting for Godot and A Streetcar Named Desire are two examples of wildly different artistic goals from theater.

I already knew that different axioms lead to different kinds of mathematics—consider the curved geometries of space-time compared with flat Euclidian geometry. So, too, do differing artistic goals lead to differing choices in craft. There’s no one-size-fits-all, not for math and not for fiction. Not for life, either, now that I think of it.

Originally, I’d intended to write about perfect verbs this month. But I had a recent happy encounter with a friend, a distinguished professor in the English department at my former university. My friend had known me only as a dean and a mathematician. When I revealed to him that I’d published several novels, he lifted an eyebrow and said I must have used completely different parts of my brain to write fiction. That got me to thinking about how my brain works, and here we are. I’m still using the same boring old brain as before, just in new ways. I hope this is at least interesting. In any case, I’ll do perfect verbs another month. See you then.

The post It’s Axiomatic first appeared on Max Griffin.

October 16, 2022

Snark

Snark. I love it when it’s aimed at someone else. Not so much when it’s aimed at me.

Just what is snark, anyway? I mean, I’ve read Lewis Carrol, so I know it’s like a Bajoom, except nobody knows what that is either, except that if you find one, it will kill you. He says there’s a map to help me find a snark somewhere around here. Oh, wait. It’s blank.

What’s that? You thought I was going to write about the portmanteau, snark, not the Lewis Carroll poem The Hunting of the Snark?

I guess I could write a Newsletter on Carrol’s scathing critique of Realism. See, he was a logician and therefore an idealist. He believed that thought and logic alone revealed Truth. For him, those silly scientists and their empirical ways were just floundering around looking for a nonsense thing, a snark. They didn’t even have a proper map—that is, ideas—to guide them. In the end, they find a Bajoom, which of course will eat them all.

But I digress. This is a blog for authors, not for a critique of a poem some author wrote in 1876. So, I guess I’ll write about snide remarks, the two words that combine to form the modern portmanteau snark. Generally, any comment that’s witty, clever, or sarcastic but always snide counts as snark.

Carrol is sometimes credited with inventing the word snark, but in fact its roots are a Middle English word for snoring. Its first use as a snide remark seems to have been in the early twentieth century, but the modern sense of the word probably came into its own in the mid-1980s with CBS Late Night host David Letterman. His use of the word added a playful insouciance to what would otherwise be biting sarcasm.

That sinkhole of popular fads, television, is a virtual fountain of snark. Some TV shows are wall-to-wall snark, where the goal of the writers seems to be to show how clever they are. Consider this exchange from Firefly, which is typical.

Jayne

: Ten percent of nothing is, let me do the math here, nothing into nothing, carry the nothin’…

Mal

: Jayne, your mouth is talking. You might wanna look to that.

Snark is so common in the Harry Potter books, TVTropes has an entire webpage devoted to it.

In the age of celebrity, the snarky riposte is another trope.

Faulkner once commented about Hemmingway that “he has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.” Hemingway on Faullkner: “Does he really think big emotions come from big words?”

George Bernard Shaw once wrote Winston Churchill, “I am enclosing two tickets to the first night of my new play. Bring a friend. If you have one.” Not to be out-snarked, Churchill replied, “Cannot attend first night. Will attend second. If there is one.”

Dorothy Parker was a snark master, or should it be mistress? Anyway, on hearing an author was always kind to her inferiors, Parker wondered, “where does she find them?” Parker aimed her wit at herself as well as others. When asked if she would join Alcoholics Anonymous, she said, “Certainly not. They’d want me to stop now.” She also said of herself, “One drink and I’m under the table. Two, and I’m under the host.”

Even Shakespeare used snark. Think about Marc Antony’s famous “I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him” speech in Julius Caesar. He goes on to call Brutus and the other assassins “honorable men,” which is pure snark. Authors like Jim Butcher, Carl Hiassen, and P.G. Wodehouse pepper their dialogue with snark. In Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken, the road that “made all the difference,” can be read as snark. Jane Austen, in Pride and Prejudice, uses snark when Mrs. Bennet says her husband has “no compassion for her poor nerves,” and he replies, “I have high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these twenty years at least.”

Why do authors use snark? It can create humor and pass judgement. It can relieve tension. It can reveal character by showing bravery in the face danger. It can showcase a character’s sense of humor—or show off the author’s. It can also be used as a mask, or a defensive device. Snark creates its own flavor and can help make a bit of dialogue or description come to life. In real life, snark can hurt people through humor, and this is true in fiction, too. But the humor can also take the edge off a bitter comment and soften an otherwise hurtful comment.

Snark is a literary device. Like any device, it can be over-used. A thirty-minute snark-fest on a TV sitcom can be amusing. Two hundred pages of non-stop snark would make a tiresome novel. As with any device, if it calls attention to itself, it detracts from the story. If it flows with the story and contributes to the here-and-now, it’s effective amusing.

How do you tell when snark is effective? I wish I had a snarky answer to that. Maybe you can help me out in the comments.

The post Snark first appeared on Max Griffin.