Max Griffin's Blog

October 13, 2025

Making Maps

I’ve been fiddling around making maps of fictional worlds. This is my latest, of the planet Hopeulikit from the Cabot’s Landing universe.+

September 5, 2025

Meanings in Fiction

with apologies to Dante Alighieri

We all have stories to tell.

Dante had many stories, his most famous being the one about touring the afterlife. But he wrote more than stories. In his essay Convivio, he lists four levels of meaning for stories: the literal one, the metaphorical one, the moral one, and the anagogical one. This essay is about those four levels, which continue to influence Western literature seven hundred years later.

Like Dante, I have a story to tell. It’s not much of a story, but it will illustrate Dante’s four levels of meaning. My story comes first, then the meanings.

Max in der HölleMy first time abroad, I traveled to Germany to teach a mathematics course to US service members. As I got in my rental car to drive from the hotel to my classroom, my ego swelled at the idea that I was going to help win wars and defend our country. A tiny worry nibbled at me, though. You see, I didn’t know word of German beyond “deutschmark,” so I was concerned about getting lost. But I was the man with the plan. I resolved to memorize the street signs along my route.

My budget would only support the cheapest rental available, a Trabant. If you don’t know, the Trabant was made in East Germany, and it was powered by a two cycle engine–just like my lawnmower back in Tulsa. So here I was, puttering down the busy streets of Frankfurt in an East German lawnmower, dodging massive BMWs and sleek Porsches. All the while, I was peering at street signs written in an incomprehensible language comprised of words with an average of 86.38 letters.

If Lady Luck hadn’t smiled on me, some hausfrau’s mammoth Beemer would have doubtless accidentally squashed me. What saved me was that the signs said my route stayed on a single street all through the city: Einbahnstrasse. Any dummkopf could remember that, thought I. Einbahnstrasse.

It wasn’t until later, when I tried to retrace my route back to my hotel, that I deduced from the kindly finger gestures of other drivers that “Einbahnstrasse” is German for “one way street.”

As you can guess, I was lost.

Lucky for me, there was a map in the glove box of my rental car. In German.

But someone at the rent-a-car company was my guardian angel. Someone cared enough about a stranger–me!–to walk in another person’s shoes. When I snatched up the map and examined it, I recognized some French words. When I looked closer, it had Italian text, too. Then, at last, I saw that the fine print was in English Now, I’m fluent in Okie, but I can get by in English if pressed. That anonymous benefactor became my guide, my Virgil, in what ahd become my journey through German Hell.

Because of that silent savior, that person who walked in my shoes before I did–or, more accurately drove in my Trabant before I did–I wasn’t lost after all. I was found.

When I finally returned to my hotel, I reflected over a fine German lager that things always seem to work out, one way or another–not always like we planned, but they work out. I guess it’s true, what Oscar Wilde said: the good Lord watches over mathematicians and dummkopf.

MeaningsLike all stories, this one has levels of meaning. The lowest level is historical: this really did happen to me. That’s the literal level of meaning.

As authors, we spend years learning the craft of making our stories come alive in our readers’ heads. The predominant theory of modern fiction is built on this notion. We do everything we can and use every trick we can summon to convince our readers that our fictional world is real, populated by real people, with real problems and real lives. Realism is what it’s all about.

Realism, this literal level of meaning, is what draws readers into our stories and keeps them there. If our stories don’t create a convincing world, most readers will drop our books and pick up something more engaging, something more real.

But literal meaning is just the first part of what makes a story memorable. Without it, only masochists and relatives will likely read our works. Most of us crave a wider audience.

Multiple levels of meaning can keep readers coming back to our fiction, looking for more. What are some other levels of meaning?

Well, there is the metaphorical. In this level, a story uses one kind of reality, the created reality of fiction, to illuminate another kind of reality, the one we all live in. When we use metaphor and allegory in fiction, we use the visible world of our story to illuminate the visible world of reality.

Getting back to my little story, we all live in an artificial world of human making, not a natural one. We surround ourselves with constructed symbols to help us interpret and negotiate that world. But sometimes we misinterpret the symbols and lose our way. That’s when we need someone, a guardian angel, if you will, to reach out and help us. My story is a metaphor for this very real, and very human, situation. It’s the parable of the Good Samaritan, with tongue in cheek. It’s a metaphor.

But there’s another level of meaning here, a level that Dante and medieval theologians called the tropological, and what we might call the moral today. Besides illuminating a truth about the real world through metaphor, this story has a moral.

In the story, I thought I had the answers. I had a plan: just read those German signs, and I’d be the man. I was over-confident. I didn’t ask for help. I just charged ahead. This kind of hubris, this arrogance, almost always leads to disaster. It’s not what you don’t know that gets you in trouble; it’s what you think you know that’s wrong.

But the story also shows how planning and forethought can pay off, if done thoughtfully by putting yourself in another person’s shoes. My plan went bust. But whoever put that map in the glovebox had a plan, too. My benefactor’s plan involved imagining another person’s needs and thinking about more than yourself. It really does take a village to create a livable world.

I bet my benefactor would have stopped and asked for directions, too. Being a rugged individualist, I’d never do that.

So, we’ve got the literal meaning of the story, the metaphorical meaning of the story, and tropological or moral meaning of the story. What’s left?

Remember how I said that a metaphor uses the visible to illuminate the visible? What’s left is using the visible to illuminate the invisible. The world is not only stranger than we imagine, it’s stranger than we can imagine. There is a mystical element to life and living. A complete story conveys that mystery, sometimes with poetry, sometimes with tragedy, and sometimes with comedy.

I think there’s a mystical element to my little tale of being a stranger in a strange land. Perhaps it’s about the ambivalence of fate, perhaps it’s something else. After all, this isn’t much of a story. The beauty of fiction is that each reader can–and usually will–find their own unique mystical meaning in a story. Dante would have called this the anagoge, literally, “leading upward,” from the seen to the unseen. Like those street signs that read “Einbahnstrasse,” the anagoges point in one direction, but the readers may find different destinations. Just as I did with the map in my Trabant, readers will use the symbols authors give them, but they will interpret them in the language of their own culture, history, and experience.

The idea here is that a well-crafted story will, unlike my Trabant, hit on all four cylinders of meaning: literal, metaphorical, moral, and anagoge. These levels of meaning have been part of the western literary tradition at least since the middle ages. They are ingrained in our culture and in our souls.

ConclusionWe all have stories to tell. You have stories. They will be more powerful, more enduring, and more from the heart if you provide your readers with a roadmap, just like my guardian angel gave me that day in Germany. Dante gave us the roadmap. It’s simple: give your readers truth, metaphor, moral, and mystery, and they will always find their way back to you.

July 3, 2025

Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?

Films like��The Matrix��and��The Thirteenth Floor��popularized the notion of a simulated reality, populated by simulated people who didn���t know they were living in a simulation. This might seem like clever idea, but in fact it���s not at all new.��The Thirteenth Floor��is based on Daniel F. Galouye���s 1964 novel,��Simulacron-3,��while in 1942, Robert Heinlein wrote ���The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag���, a short story with similar concepts. Indeed, one could argue that Plato���s myth of the cave is the progenitor of the notion that our world is a mental construct.

So, how about it? Are��you��living in a simulation? We���re going to look at this question from three perspectives: technology, philosophy, and neuroscience. Each gives us surprising answers.

TechnologyIn order for the question in the title to make sense, two things about our future state of technology must be true.

We will eventually be able to produce��simulated people, i.e., self-aware artificial intelligences with the ability to process information in a way that���s indistinguishable from human intelligences; andWe will be able to produce a��simulated reality��of sensory inputs for these simulated people, and do so in such a way that the simulated people would be unable to determine that they were in a simulation.Despite all the current hype around AI, we are nowhere close to achieving either of these things. Still, the general consensus is that it��is��possible, some think it���s even likely, that��someday, maybe as soon as in the next hundred years, we��will��achieve the above two things. But the consensus is clear that we won���t do so any time soon.

In fact, we don���t even have a good definition of what it means to be self-aware, what consciousness is, or our how it arises in our brains. We���re a long way from even a theory of how to do (A) and (B).

Besides these theoretical constraints, our hardware is also far from being capable of (A) and (B).

Just for comparison, our brains are capable processing between 1014 and 1016 operations per second. Our current fastest super computer processes roughly 1018 operations per second, so that computer could���in theory���simulate as many 104 or as few as 102 human brains. But, that doesn���t take into account simulating the reality for these brains, which could use up another 108 (or so) operations per second. In other words, our fastest supercomputers couldn���t even do a simulation involving a few dozen simulated people and their associated reality, assuming we even knew how to simulate people or reality in the ways (A) and (B) posit.

PhilosophyWe already mentioned the myth of the cave, but there���s a 2003 paper��by the philosopher Nick Bostrom that asks the specific and��personal��question that���s the title of this newsletter:��are you living in a computer simulation?��Bostrom���s contribution is that he reframes this question:��What are the��chances��you are living in a computer simulation?��Instead of ���yes��� or ���no,��� this reframing lets him assign the odds of this being true. Are they one in one hundred? One in a thousand? Even? His reframing gave the following astonishing conclusion.

In terms of our question, Bostrom concluded there are two possibilities.

We someday acquire the abilities in (A) and (B) above, in which case it is almost certain you��are��living in a simulation���the odds are trillions to one that this is true; OR��We never acquire the abilities in (A) and (B) above, so we���re never able to create the necessary simulation, so the odds are zero.If, in fact, (A) and (B) are feasible, then if we���re��not��living in a simulation conclusion (2) suggests we destroy ourselves before our technology advances to the point that we��can��create such simulations.

One could argue that if we ever achieve (A) and (B), many simulations will include past realities, as in��The Thirteenth Floor. That means that if we��ever��achieve (A) and (B), the future reality in which we do so will generate simulations that exactly mimic the world we think we live in.

In passing, I should note that Bostrom���s reasoning in getting to (1) and (2) is open to argument. For example, if (B) includes simulating features like quantum mechanics and the uncertainty principle, it���s not at all clear that we could ever achieve (B) on the scale required to reach his conclusions (1) and (2).

NeuroscienceNeuroscience tells us that��most��of what we think we��see��is a visual construct��inside our brains, so we���re��already��living in a simulation, just not one that���s computer-generated.

Try this. Close your left eye. What���s that big thing jutting into the left side of your visual field? Oh. Of course. It���s your nose. Open your left eye, and it magically disappears. That���s evidence of your brain correcting what you ���see��� by consolidating the visual information from the two eyes and editing out the unnecessary bits. It���s not that your nose isn���t necessary. It���s just that we don���t need to see it in order to avoid that saber tooth tiger lurking in the savanna.

Next, hold out your arm and give yourself a ���thumbs up.��� See your thumbnail? That���s roughly one degree of visual arc. It turns out, that���s how much of the world we can see with 20/20 vision. The rest is blurred���so much so, that we���re legally blind outside of that one degree arc. It doesn���t look that way, because your eye is subconsciously moving around all the time, scanning your environment. The brain patches these scans together, seeking out patterns and predicting what���s in the out-of-focus pieces. Under most circumstances, the brain does a good job of this. Fooling that prediction is the source of most optical illusions.

Then there���s that famous dress. You remember that one, right? Is it��blue and black��or is it��white and gold? The dress revealed individual differences in color perception.

The brain has over 100 trillion neural connections. That���s more connections than there are stars in the Milky Way. Those connections somehow work together to create us and the world we think we live in. It���s still a mystery how this gives birth to the self-aware, free-willed individuals we all consider ourselves to be. It���s even possible that our perception of self is an illusory construct of this complex neural network.

The point here is that neuroscience seems to be telling us that we��already��live in a simulated reality, one created by our brains based on our sensory inputs. Also, in case you didn���t know, that input includes information from between fourteen and twenty senses or even more, not just five.

ConclusionSo, what���s the answer? Are you living in a computer simulation?

The consensus is that it���s possible we might build such a simulation someday. Bostrom���s analysis says if we ever do, then the answer is an emphatic yes. But neuroscience says we���re already living in a simulation.

If the real world we think we live in is an illusion constructed by our brains, does it matter if we���re living in a computer simulation? Would your choices be any different if it turned out you are living in a computer simulation? If so, what choices and why would they be different? How about other people? Are they NPCs, non-player characters in the game of life and thus expendable? Or are NPCs, who are exactly the same as real people except for their cybernetic origin, deserving of the same respect and agency as you? What if you’re an NPC? If you were, you wouldn’t know it (see (B) above).

As authors and artists, these are kinds of questions that are interesting. They are questions about the meaning and purpose of life, about what makes us human, about ethics and morality, about freedom and destiny. Whether reality is just shadows on the wall of Plato���s cave or a simulation in Neo���s matrix, whether it includes the uncertainty principle or is deterministic, we still have to answer these kinds of questions.

In thinking about fiction and reality, I always come back to something Hemingway said: “I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea, a real fish, and real sharks. But if I made them good and true enough, they would mean many things. The hardest thing is to make something really true and sometimes truer than true.”

Whether reality is simulated or not, there���s still the shared truth, the truth that Hemingway is talking about, the truth that makes us all human.

That���s what matters.

May 25, 2025

The Cave of Worlds

I’ve started a new novel.

Sebastian likes his new job, except for all the distractions. His OCD forces him to constantly check stuff out, like that hunky guy he spotted going into the mysterious office down the hall. When Sebastian checks him out, he winds up joining a desperate quest to save the Cave of Worlds, a system of wormholes and the realms they connect.

The frist three chapters are available on Writing.com.

April 3, 2025

The Wheft

Wheft. (n) (nautical)A kind of streamer or flag used either as a signal, or at the masthead for ornament or to indicate the direction of the wind to aid in steering.

Webster’s online dictionary

Verisimilitude is the appearance of being true or real. It’s a fundamental feature of realistic fiction. It applies to characters, plot, setting, and all other elements of the ficttional world. It’s what Hemingway was talking about when he said

I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea and a real fish and real sharks. But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things. The hardest thing is to make something really true and sometimes truer than true.

Ernest Hemingway

Anyone reading fiction knows it’s not real, but, for the sake of the story, the reader starts out willing to believe what’s one the page. It’s up the author to endow the fictional world with the appearance of reality, to nurture the readers’ willingness to believe. This means giving the reader sufficient reasons, if they squint and don’t think too much about it, to continue to believe.

Fiction will sometimes include a signal to the readers that things are different in the fictional world. An example of this is when the clock strikes thirteen in the first line of Orwell’s novel 1984. Science fiction often includes words that, at least on the surface, makes the fictional world plausible. We know, for example, that the faster-than-light spacecraft in Star Trek are impossible, but they are called warp drives. The word warp is a signal that they they alter space-time in new ways, making the faster-than-light travel possible. It’s a subtle but effective signal.

When fiction involves supernatural elements, this signal sometimes includes a dream-like veil that separates the real and supernatural worlds of the story. However, I’ve always had a problem believing in this kind of fictional world. After all, the real world doesn’t include such a veil except in dreams.

For me, the problem with supernatural elements in most fantasy stories is that they require I abandon physical aspects of the real world that I know are valid without giving me an even semi-plausible explanation. Even if I squint really, really hard and really, really want to believe, I still can’t accept that a spiderbite can give you superpowers. The same is true for a veil marking a supposedly real, but dream-like, world filled with wierd stuff.

Morden physics, however, is full of weird stuff. Stuff like spooky action at a distance (quantum entanglement), or wormholes (space-time tunnels), or invisible stuff (dark matter and dark energy). In this essay, I’m going to use the word wheft as a signal for a particular kind of supernatural fictional world that is grounded in way that permits this kind of weird stuff and more. I think it could even make it plausible that dreams are real, at least, if you squint hard enough, don’t think too much about it, and want to believe for the sake of a story.

The basic idea of this essay is to hypothesize a universe–or even universes–of invisible matter and/or energy occuping the same space-time we occupy. The wheft is the what I’m calling the hypothetical boundary–or boundaries–between this invisible universe and our visible one.

In order to ground this hypothesis, I first give some history on “the willing suspension of disbelief,” then discuss some unsolved problems in physics, including some speculation, by real physicists, about possible solutions. The point of the science discussion is that physicists need to figure out ways to account for wierd, invisible stuff, and they are creative in doing so. If you’re not interested in the scientific discussion, you can just skip to the final section where there is free-wheeling speculation on the kinds of ways an author might deploy this wheft as a signal.

Willing suspension of disbeliefSamuel Taylor Coleridge was the first to use this phrase in 1817 when he said that in his poetry he tried to infuse

a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure…that willing suspension of disbelief.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Biographia Literaria, Chapter XIV

The idea is even older. For example, in Book II of Acadmica in CE57, Cicero mentions adsensionis retentio, or “holding back of assent.” Both Coleridge and Ciciero were writing about poetry with a supernatural element, but the concept applies more broadly to all fiction.

The Coleridge quote is important because it places the the burden on the author to provide both the human interest and the semblance of truth to keep the reader’s willing suspension of disbelief going.

Two Kinds of MatterThe first kind is the one we’re familiar with, the matter that we can touch and feel. We’ve been studying that matter as long as we’ve existed. Whether it’s Plato’s forms, or Einstein’s space-time continuum, or Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, we’ve been studying it and measuring it forever. Physicists have developed a detailed model, the Standard Model, that describes this kind of matter with enormous accuracy, down to hundreds of decimal places. It’s the most-tested and most accurate model ever created by science. Well, that and General Relativity, which we’ll get to later.

Anyway, that’s one kind of matter, a kind we understand in detail.

What’s the evidence for two kinds of matter?

Back in 1933, Fritz Zwicky started to observe something unusual about the rotation of galaxies. He could measure the speed of galactic rotation and roughly calculate the mass of the galaxies. His calculations showed that the rotation was so fast that the galaxies should fly apart, that there wasn’t enough mass to hold them together.

Zwicky was a meticulous scientist, so no one argued with his measurements. However, he was also a snarky kind of guy, and no one liked talking to him. The easiest thing to do was to just ignore him, his snark, and his puzzling observations, which is what happened for the next forty years or so.

Eventually, however, it became obvious he was onto something, especially thanks to Vera Rubin’s work in the 1970s. It eventually became clear that a halo of invisible matter surrounded almost all galaxies, and this invisible matter was the extra mass needed to hold them together. We know this matter exists because we can observe its gravitational effects. It’s what’s holding galaxies together despite their rapid spin. Detailed measurements of the cosmic background radiation provided even more, if indirect, confirmation of this invisible halo.

We call this invisible matter “dark” because we can’t see it directly. In particular, it doesn’t interact with photons. It’s invisible.

Whatever it is, we know from its gravitational effects how much of it there must be. The answer is a lot. There’s about six times as much dark matter as regular matter in the Universe.

Dark MatterThinking back to regular matter and the Standard Model, it’s natural to supose there might be an unknown component of that model, a particle or maybe a field, that accounts for dark matter. Perhaps dark matter arises from something similar to, say, the Higgs Boson which accounts for the mass of ordinary matter.

There’s something called “supersymmetry” which gives candidates, WIMPS and Axions for example, for such a particle or field. Physicists have been looking at candidates for a couple of decades with increasingly sensitive experiments. They have found exactly nothing. Well, not quite nothing. They’ve managed to restrict range of possible places to look. It’s pretty narrow at this point. It’s bad enough that some physicists are starting to think this is a dead end.

There’s an emerging theory that supposes an entire “dark universe” that coexists with the one of our senses, the one of the Standard Model. This theory hypothesizes that this “dark universe” has its own version of a “Standard Model.” The dark universe and our universe interact primarily, or maybe only, through gravity.

Einstein teaches us that gravity involves the shape of space-time, so the dark universe would share the same space-time continuum in which we live. But, if this new idea is right, the dark universe might have different laws of physics. Different laws of physics mean that anything is possible in this universe, a universe that’s right here, occupying the same space-time that we occupy. It might even have had its own equivalent of the Big Bang, but not contemporaneous with ours, whatever “contemporaneous” might mean in this context.

This idea is brand new, having only been proposed in the last year or so. It’s intriguing, especially in light of the failure to find evidence consistent with the Standard Model for dark matter. In fact, the primary evidence for the theory is the failure of these experiments. Not the only evidence, though. It might also explain some problems related to the earliest nanoseconds of our universe. The jury’s out on that, and it’s right to be skeptical about a radical new theory like this one.

In any case, finding out the nature of dark matter is a Big Open Problem in physics.

I’ll relate this back to fantasy worlds and the idea of a “wheft” later, but next I want to mention the Big Bang and dark energy.

The Big BangAll the way back in 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that the universe is expanding. No one paid much attention at first. Hubble wrote Einstein a letter about the expansion and its relation to Einstein’s proposed “cosmological constant.” Einstein ignored him at first. But the evidence eventually became clear, and Einstein apologized and took the cosmological constant out of his theory of general relativity. He even said it was the worst mistake he ever made.

If the universe is getting bigger, then it must have been smaller in the past. Running the clock backwards is what led to the hypothesis of the Big Bang. This, too, was controversial, until 1964 when Penzio and Wilson discovered the microwave background radiation, an echo of the Big Bang.

Everyone figured one of three things were possible after the Big Bang. One possibility would be that the expansion would go on forever, slowed down by gravity but never reversed. Another was that gravity would eventually slow down the expansion and reverse it. The reversal could then result in another Big Bang, in an eternal cycle. That was an appealing conjecture, so most scientists supposed it was probably true, although there was no data to support it. A third possibility was that the expansion and mass would exactly match up and the expansion would stop but not contract. That balancing of pencil-on-its point seemed highly unlikely.

Eventually, astronomers were able to gather data to decide which of the three hypotheses were correct. To their amazement, they discovered that none of them was right. Instead, they found that the expansion of the universe initially slowed as expected, but then, about five billion years ago, it started to speed up.

Speeding up the expansion of space-time has to use energy. We have some ideas about what the source of that energy might be from quantum mechanics, but we don’t know for sure. We’re kind of in the dark. Hence the name “dark energy.” It’s also called “dark energy” just for symmetry with the other Big Unknown Thing I mentioned above, dark matter. In any case, finding the source of dark energy is a second Big Open Problem in Physics.

A natural question is, how much energy does it take to account for the observed acceleration? Knowing the rate of expansion and an estimate of amount of matter in the universe, we can deduce the approximate energy requirements via Newton’s F=ma. It turns out it’s a lot of energy because there’s a lot of mass.

Remember Einstein’s E=mc2? That says energy and mass are the same thing. That means we can calculate the totality of the mass and energy in the universe, taking into account regular matter, dark matter, and dark energy.

The two kinds of matter, regular matter and dark matter, only constitute about 27% of the universe. The remaining 73% of the universe consists of dark energy. Like a said, that’s a lot. It also means that the “dark” parts, the parts we can’t see and know next to nothing about, constitute over 95% of the space-time continuum in which we reside.

The Hubble TensionAs if dark energy weren’t bad enought, things get even worse.

It turns out that astronomers have two ways to measure how fast the universe’s expansion is accelerating. They are largely based on looking at different time frames, and astronomers have lots of data to give them confidence in each of the two ways.

The problem is that the two methods give different answers.

This is called the “Hubble tension,” and is a third Major Open Problem in Physics. New data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JSWT for short) confirms the disagreement between the two methods, the tension. Yet, they can’t both be right.

Our best guess about what gives rise to dark energy is that it’s a characteristic of space-time itself. The acceleration in the expansion then kind of makes sense. As the universe expands, there’s more space-time, and thus, whatever it is about space-time that generates dark energy, there’s more of it and thus more dark energy.

But, there’s more pesky data. The same data from JSWT that verified the tension also seems to imply the acceleration is now slowing down. It that’s right, the “more space-time-means-more-dark-energy” idea must be wrong.

Relativity and Quantum MechanicsThe Standard Model, that hyper-accurate model that makes the modern world of electronics possible, is based on something called quantum mechanics. Gravity, on the other hand, has to do with the shape of space-time and comes from general relativity. General relativity is just as accurate and well-verified as the General Model. Global positioning systems work because they have built-in corrections deduced from relativity, for example.

Early attempts at combining gravity and quantum mechanics resulted in nonsense results. We understand relativity and hence gravity at large scales, like satellites orbiting the earth or light from distant stars. We understand quantum mechanics at atomic and sub-atomic scales. At atomic scales, gravity and speed-of-light delays usually don’t matter.

Except, of course, when they do. In black holes, for example. Or in the early nanoseconds of the Big Bang.

Uniting relativity and quantum mechanics in a single set of equations is a fourth Big Unsolved Problem in physicists. Einstein spent the last forty years of his life searching for just such a unified field theory and failed. String theory and loop quantum gravity are two promising attempts, both requiring multiple dimensions to work. If either of these are the right equations, we live in a universe consisting of twelve or maybe thirteen dimensions, with all but four wrapped up so small we can’t see them.

The WheftFinally, let’s close the loop back to the notion of the wheft.

What follows is free-wheeling speculation. There is no science or theory or data behind it or any of the speculations in the rest of this essay. It’s all just letting imagination run wild on the ways that a fiction author might use some of the above ideas in a fictional universe. The fictional universe might have a passing similarity to the one we live in, just like the Star Trek universe. Or the Hobbit universe, for that matter. The purpose here is to use some of the above ideas to spit-ball more fictional universes, to exploit the Big Open Problems but not solve them.

The Big Open Problems are an opening for our imagination, a signal flag to stimulate thinking about what might be possible. They wave a flag I’ve called the wheft, both for the metaphor and because I like the sound of it.

Just to review, the premise for that new theory about dark matter mentioned above involves a whole universe of invisible dark matter particles, similar to but different from those of visiible matter, that share the same space-time we occupy, but don’t interact with photons. That makes this dark matter invisible. In this theory, dark matter does intearct with visible matter via gravity–that’s how we know dark matter must exist–but not in any other way that we can observe, at least so far.

The shorthand version is that there’s an hypothesized invisible dark universe occupying the same space-time we occupy, but with potentially different and unknown physics. The wheft is what I’ve called a hypothetical boundary between the visible universe and the hypothesized dark universe.

I admit that I’ve borrowed this from a similar word, weft, used by my friend and author, Brianna Tientze in her forthcoming novel Rain. She borrowed the word from weavers and used it as the vehicle, along with incense, that carried magic in the fictional world of that novel. It’s an amazing piece of fiction and a wonderful word.

With that said, here we go!

The characteristics of such a fictional universe could fit nicely with some of the Big Unsovled Problems in physics. Since they’re unsolved, there’s lots of room for fiction authors to exploit them in novel ways.

First, and foremost, there’s the notion of a “dark universe” that co-occupies space-time with our visible universe. If it has its own laws of physics, well, that’s certainly magical. We just need those laws to make consistent sense. We can know it interacts with our visible universe, for example via gravity, but not with photons, so it’s invisible. But, maybe, it interacts in other ways we can’t measure.

Another thing we don’t understand is how consciousness arises. In fact, we don’t even have a good definition of what consciousness is. There’s lots of research into machine learning and artificial intelligence, but the implications for human consciousness and free will remain unresolved at best. Why not, for fictional purposes, suppose that consciousness arises at the boundary between the dark universe and the observable universe, i.e., in the wheft?

By hypothesis, the dark universe and the observable universe interact, for example, via gravity. If consciousness arises on the boundary between the two, then consciousness itself could be another kind of interaction. Note, this is all evidence-free speculation, but it’s called speculative fiction, after all. This gives another premise for stories.

If the dark universe has different laws of physics, well, that’s so much the better for fictional purposes. We have zero observations right now on what those laws might be, so let your imaginations run free. Just be consistent.

How about sensing the wheft ? Suppose some people have deeper insight into the dark universe than others, and these talented magicians can perceive a signal, a wheft, from that universe. That could be one feature how consciousness and a dark universe might interact. It could also be used to create the veil so common to many fantasy stories.

How about travel to a dark universe? Well, relativity allows for the existence of wormholes, openings in space-time to other parts of the universe. Under our laws of physics, these wormholes are both unstable and require ginormous amounts of energy to open. Worse, travelling through them in our universe probably shreds normal matter. But…if the dark universe had different laws of physics, it might have different rules for wormholes.

Maybe something like wormholes between the dark universe and the observable are possible.

Faster-than-light travel is impossible in our universe. How about the dark universe? Is it possible there? Probably not, since that limit is part of the shape-of-space-time stuff from general relativity, but, again, speculation. Wormhole to the dark universe, zip along faster than light, then wormhole back to the observable universe.

Maybe the arrow of time is different in the dark universe. Now we’ve got time travel.

The same wormhole-to-a-dark-universe idea would permit invisible spirits from the dark universe moving around space-time right next to us. But those savants in our universe, the fictional ones we’ve imagined with the supposed special sensitivity to the dark universe, could sense them.

Maybe consciousness passes to the dark universe on our death.

The possibilities for this thing I’ve called the wheft are endless. They make pseudo-science sense out of most fantasy memes. They are a framework to unify many themes, to say nothing of many legends.

Please, do not think I’m proposing that my idea of the wheft explains legends, or any real thing for that matter! This is supposed to be a fun exercise for authors of speculative fiction. It’s not a candidate for an episode of Expedition Unknown. I mean, I kind of like Josh Gates, but, really, don’t go there. God forbid.

Run with it. Free your imagination. Have fun but don’t take it seriously. Tell me how you’d use these ideas.

March 31, 2025

The Allegory of the Cave

Nature doesn’t ask your permission; it doesn’t care about your wishes, or whether you like its laws or not. You’re obliged to accept it as it is, and consequently all its results as well.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, in The Dream of a Ridiculous Man

We have art so that we shall not die of reality.

–Friedrich Nietzsche

I like realism in literature. I want fiction to take me to places I can’t go and introduce me to people I’d never meet in real life. Realism in literature replaces one kind of reality—the reality I in which I live and breathe—with another kind of reality, one I imagine in my head. It doesn’t matter if I visit that fictional reality by reading a book, by going to a play, or by watching a movie. Fiction transports me to alternate realities. Fiction reveals endless possibilities.

But wait. If fiction is just imagination, it’s not really real, right? What’s real is what I can touch and taste, what my senses reveal. That’s reality, not words in a book or images on a screen.

Maybe. But maybe there’s more to it.

The allegoryImagine, if you will, prisoners in a cave facing a stone wall. Behind them, a fire flickers, but none of the prisoners turn to see it. Jailers might walk between the prisoners and the flames, but all the prisoners would see are shadows moving on the wall they face. The jailers might hold an object, say a book, and the prisoners, seeing the shadow of the book, would mistake the shadow for the thing itself.

Now imagine a prisoner turns and sees, in the dim flickering light, the flame, the jailers, and what they carry. Such a prisoner now sees more clearly, sees the book itself and not the mere shadow. The prisoner’s view of reality has just undergone a revolutionary change. Never again will shadows seem real.

Thus begins Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. We can learn many lessons from this simple story.

The prisoners have constructed a reality from the shadows they see on the stone wall. They might talk about it. They might even conjecture about the nature of a book from its shadow. In a sense, they are making observations, collecting data, and drawing conclusions, just like a modern-day scientist. Well, they’re not solving differential equations or other complex math, so it’s not just like a modern-day scientist, but the basic model of drawing conclusions from observations is there.

Another thing the allegory reveals that observations depend on the observer. As long as the prisoners face the wall, all they see are shadows. Once one of them turns around and sees the light, their frame of reference changes and the model of reality in their heads expands. The world itself doesn’t change, but how they think about it does.

But there’s more. The prisoner might spend many hours or days examining a book, touching it, turning its pages, examining the words scribed thereon. But if the prisoner doesn’t know how to read, the true form of the book will be forever hidden. The prisoners’ reality is still limited, not by what prisoners imagine but by what they can imagine.

In fact, our prisoner and the jailers are both in a dimly lit cave. Most aspects of reality are hidden from them. If they step outside, into the sunlight, what will they see? At first, the brilliant light might blind them, but eventually they’d see leaves of green, and red roses, too. They’d see our wonderful, wonderful world. No doubt they’d want to return to the cave to spread the news

But back in the cave, the light is again dim. With eyes wide open from the sun, we can imagine they’d stumble. We can imagine the tales they would struggle to tell.

Back in the cave, prisoners and jailers alike still live in a shadowland. They might deduce the laws of the cave—how water flows and breezes blow—but oceans and thunderstorms are unknown and unimaginable. The prisoner who has seen the light of the outside would seem apostate, or even perhaps insane.

I sometimes think writers are like prisoners who have seen the light.

Why the allegory mattersThe Allegory of the Cave is powerful. It has had a profound influence on Western thought and the evolution of natural philosophy, first to natural law, and, eventually, to science as we know it today. There’s a direct line of descent from Plato’s forms, to Newton’s Principia, to Einstein’s General Relativity, to Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. Einstein famously said, “God does not play dice with the Universe,” because Einstein, like Dostoevsky, thought of the universe as a clockwork, with knowable laws and an ultimate certainty.

In fact, Einstein’s expressed disdain for dice was intended as a direct rebuttal to quantum mechanics and, in particular, to the Uncertainty Principle. Einstein believed in a deterministic reality and rejected the notion, implicit in quantum mechanics, that probability played any necessary role. In his view, nature at its most fundamental level is knowable, even if it’s implacable as Dostoevsky’s ridiculous man asserts. .

In the Allegory of the Cave, different frames of reference lead to different interpretations of reality. Our frame of reference colors how we think about the information our senses bring to us, whether that information is shadows on a stone wall or the dazzling garden outside the cave.

As I walk through the real world, the one I can touch and smell, I carry with me a cultural frame of reference that includes Plato’s forms, Newton’s clockwork mechanics, Einstein riding an imaginary light beam, Bohr’s atom, Shakespeare’s MacBeth, Picasso’s Gurenica, and much more. On top of this cultural frame are even more basic intuitions, some of which may be genetic. The cause-and-effect sequence, for example, is doubtless ingrained in not only humans but other species as well. The same is probably true about the arrow time.

Beyond the allegorySo, what is really real? I believe that the universe is what it is, not what I wish it to be. I believe that we don’t live by bread alone, but that we unquestionably do live by bread. Reality acts on me: I stub my toe and it hurts; the sun shines and warms my skin; I can fall ill; I can die. But I also believe that what is really real is a deep mystery. Maybe we live in a simulation, like in The Matrix. If such a simulation is possible, then a convincing argument can be made that it’s virtually certain that we do live in a simulation. If that’s true, either nothing is real or everything is real.

But it gets worse. That cultural baggageheritage I mentioned? The one that influences how I think about the world around me, the one where effects follow from causes, where the arrow of time advances and never retreats, the one that abhors spooky action at a distance…that frame of reference? It’s probably wrong. All of it. If so, my walking, breathing reality, the one I think I live in, is as false as the prisoners’ shadows on the stone wall.

For you see, something called Bell’s Inequality has upended Einstein’s deterministic reality and, with it, Plato’s forms and all the rest. It turns out chance does rule, at least at the most basic, quantum level. The late, great physicist Richard Feynman once remarked that if you think you understand the surreal quantum world, you’re wrong. The universe is not only more mysterious than we imagine, it’s more mysterious than we can imagine.

The allegory and fictionWhat’s all this mean for the author of fiction? Well, fiction all happens in our head, whether we are authors or readers. One lesson from the Allegory of the Cave is that our personal reality happens in our heads as well, structured by a frame of reference. Authors can use all that baggage, that shared frame of reference, to stimulate the readers’ imaginations and create compelling, believable worlds. In doing so, they can sometimes even reveal truth.

Hemingway said it best: “I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea and a real fish and real sharks. But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things. The hardest thing is to make something really true and sometimes truer than true.”

March 7, 2025

Copyright and Artificial Intelligence

Last July, the US Copyright Office issued the first of two reports dealing with copyright and artificial intelligence. The second, released on January 29, 2025, deals with copyrights and generative AI. Both of these reports clarify prior guidance and answer some open questions about copyright, digital copies, and generative AI.

This post will mostly deal with the January, 2025 report on generative AI and copyright. The July report on digital replicas raises many serious questions and urgently calls for new legislation to regulate the exploitation of digital images and protect the rights of individual citizens with respect to their personal name, image, and likeness. NIL issues are certainly important, but only indirectly for most authors, hence the focus of this newsletter.

This blog discusses copyright and not the merits (or lack thereof) of using AI. Generative AI, in particular, raises troubling questions about the degree to which an author contributes to setting the final form of the product. Historically, new technology such as photography raised similar troubling questions that have since been resolved–at least for most people.

An important issue raised by generative AI, however, is that, as the Copyright Office notes, the training data for generative AI involves probable violations of the vaild copyrights held by living authors. The US Copyright Office plans a third report for later this year that addresses these and other legal issues. While “legal,” “ethical,” and “artisitcally valid” are distinct concepts, there is significant overlap in the issues they raise. In particular, US copyright is constitutionally intended to protect creators of “useful and practical arts.” As the discussion below will suggest, the degree to which an author’s creative process exerts control over the final form of a manuscript will be of critical importance.

Copyright varies from nation to nation. This newsletter deals exclusively with US copyright laws and, in particular, the above reports.

For the sake of completeness, we’ll begin with a review of some background concepts on copyright. Remember, I am not a lawyer and this is not legal advice. If you need legal advice, consult an attorney.

The BasicsThere are two basic requirements that must be met for something you’ve created to be eligible for copyright: it must be fixed in some tangible form and it must be original.

While there are two requirements, there are at least four ideas: create, fixed, tangible form, and originality.

You can’t create an idea or a fact, so, no copyright.

Tangible form means that your creation can be expressed to others, usually through visual or other means. Fixed means that the tangible form can’t be ephemeral, which generally means there must be a physical record. Performance art, for example, usually has a tangible form that, by definition, is not fixed and hence not subject to copyright. Same for ice sculptures.

However, it’s easy to fix a story in tangible form. Writing it on a piece of paper is sufficient. If you type your story on your computer, that puts it in tangible form. It’s fixed once you save it. It’s that easy. Just remember to save it, otherwise it’s not fixed and vanishes when you turn your computer off!

“Original” means that the “tangible form” is something you alone created. In particular, it means the tangible form is not copied in whole or part. The original creation doesn’t have to be novel (as in patent law), unique, imaginative, or inventive. Creating it doesn’t even have to be hard to do. It can even be obvious. It just means that you, on your own, set the fixed, tangible form. Under copyright law, “originality” is a low bar, and almost all works will satisfy it.

It’s a low bar, but there are still restrictions. Your original work can’t copy someone else’s work in whole or part, even if what you copy is not itself copyrighted. You can’t copy Homer’s Iliad, even though the concept of copyright was unknown to the Greeks. If it’s not original, you can’t assert copyright.

Remember, an idea can’t be copyrighted. That means you can write a detective novel about a world-weary detective in San Franscisco, and not violate Dashiell Hammet’s copyright. However, you can’t use all or part of someone else’s tangible expression in your work, at least not without permission. Sam Spade is part of Hammet’s tangible expression of The Maltese Falcon, and you can’t use him in your work without permission.

While your tangible form must be original, that doesn’t mean you can’t use tools to produce it. Most authors do research, use dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other tools. But these are tools the author deploys as part of the process of creating the tangible form.

You can follow the outline Joseph Campbell provides in The Hero With A Thousand Faces to plot your novel. That outline is an idea, and hence not subject to copyright. That particular outline is an idea that can and has been used by many authors, which was Campbell’s whole point. Your novel is one of many possible tangible expressions of that idea, and you can own the copyright to it.

In fact, you can use any outline to plot your novel. Outlines are ideas and not subject to copyright. The tangible form, the novel, is.

You can write a sequence of stories about travelers telling stories to each other, even though Chaucer has already had that idea. The idea doesn’t have to be original, just your tangible expression of that idea.

You can write a detective story, even though Edgar Allen Poe came up with the idea.

Continuing on this line, you can use technology to assist in the creation of your tangible expression. You don’t have to use a quill pen and parchment to write your novel. You can use a typewriter, a computer, or Microsoft Word. You can use a spell checker, a grammar checker, or other tech tools to improve or refine your tangible expression. But your hand, the creator’s hand, must set the final form of the tangible expression.

Some forms of technology are fine, but what about artificial intelligence? We’ll get to that, but the US Copyright Office report asserts that there is ample existing case law to handle questions regarding AI generated content. The advent of photography and the consequent evolution of case law regarding copyright is an example.

The example of photographyIn the nineteenth century, many artists made a living doing portraits. Such portraits had fixed tangible form and were original, and thus the artist who created them owned the copyright.

Then photographs got invented. Photographs also have tangible form. But did the photographer “create” them, or was the final form set by the camera? Today, the final form of your selfie is entirely set by your phone—all you do is click a button. How creative is that?

The answer, at least in the US, is that it’s sufficient to assert copyright. The person who clicks the button is, generally, the creator and thus the owner of the copyright. “Person” here is critical—a monkey can push the button and take a selfie, but US Copyright Office confirms that the law only applies to human-created works.

In some cases, though, someone else might be creatively involved in the photograph and own the copyright rather than the person who clicks the button. There might be decisions about staging, costuming, lighting, or even inducing facial expressions, that constitute “setting the final form” before the button gets pushed.

The point is, though, that when you click the button for your selfie, you’re generally the one making those decisions. You’re exercising the minimal creative control over the photograph required to meet the low bar of originality. Since the photograph is both fixed and tangible, it qualifies for copyright protection.

If a monkey clicks the button, however, there’s no copyright. The law only applies to works created by humans. Similarly, if a security camera takes a picture, that’s an entirely automated process with no human agency, so no copyright.

You can no doubt see where this is headed. We’re ready at last to discuss the most recent report.

Generative AI and CopyrightThe first finding in the January report is that works wholly created by generative AI with no human agency do not accrue copyright protection. The monkey precedent establishes that. A big corporation running a super-duper AI program on their trillion-dollar computers might use it to produce a novel a zillion times better than War and Peace. (Probably not, but bear with me.) They can’t copyright that novel and make a fortune off of it because a computer wrote it. The novel, the tangible form, involved no human agency. It’s exactly like the monkey’s selfie. Not much motive for a profit-hungry mega-company in that.

But what about the prompt that generates AI content? Can the author of the prompt claim copyright on the prompt itself, or on the resulting content? The report notes that a prompt alone is insufficient to claim copyright on either the prompt or the result. Via 17 USC § 102(b), copyright does not protect “any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied…” in a work, and thus the prompt cannot be protected by copyright. It’s similar to things like recipes or knitting patterns that also aren’t generally protected by copyright.

A “prompt” is like an outline or an idea, and hence you can’t claim copyright on the prompt. If the tangible form resulting from that prompt is entirely AI generated, then it is not subject to copyright for the reason noted above.

This finding is also based, at least in part, on the observation that minor changes to prompts can result in unexpected and significantly different outputs. The person writing the prompt is thus exercising insufficient creative control over the tangible form. The technology is evolving, however, and the report notes that this finding may change along with the technology.

What if you use AI to generate an outline for your novel, then you write the novel? Well, at least in principle, that’s like using the outline from A Hero With a Thousand Faces. When you use it to write your novel, you’re setting the tangible form of the idea, i.e. the outline. The report finds that you can claim copyright on the resulting novel.

Where it gets tricky is when AI-generated content is embedded within your own, original content. Suppose, for example, you’re flummoxed trying to come up with a description of the Sahara Desert and ask ChatGPT to write a description for you? If you put that in your novel, does that compromise your copyright?

More generally, what, if any, is the line between spell checking your novel and having ChatGPT write content? How about if you use what ChatGPT wrote, but you revised it? Does changing one word make it original, or does the change need to be more substantial? How much AI-generated content would it take to void the copyright protection for an entire novel?

The Copyright Office’s report concludes that, at least for the moment, there is no bright line that answers these questions. Indeed, it cautions against establishing such a bright line. Copyright disputes over nuances like this are common and rely on case-by-case evaluation and the application of appropriate precedent and judgement, not rigid rules. The report finds that existing law and relevant processes will be sufficient in resolving questions regarding mixed content–content that is partly AI-generated and partly original.

An example of “relevant process” is the famous dispute between Led Zeppelin and Spirit over a chord progression in Stairway to Heaven. You can’t copyright a chord progression, but can copyright a song. The extent to which one song might or might not violate another artist’s copyright is a matter of judgement, not the mere use of a chord progression, no matter how similar the songs may sound.

The case-by-case assessment on how the use of AI impacts copyright in any document is likely to hinge on the creative process—whether the AI is used to assist in polishing the document or, instead, acts as the principal decision maker in fixing the final form of the document. Authors who plan to use AI as an assistive technology will likely need to attend, at least for the present, to documenting their creative process.

Some AI platforms permit the author to interact with the AI-generated content, editing and revising it. The report reiterates that, in this case, documenting the creative process will be critical in assessing the extent, if any, to which copyright might attach.

Name, Image, and LikenessThe report on digital replicas is new since my last newsletter, so I want to briefly discuss this topic.

What if someone takes a picture you? Do you own the copyright of your own image? The answer, in most cases, is no. However, most US states have laws protecting your name, image and likeness (NIL), and a third party can’t use those without your consent, even though they might own the copyright on a photo of you. If a third party profits from using your name, image, or likeness, you may usually make your consent to use the same contingent on compensation. If you follow NCAA football, NIL is a now-familiar concept.

A related issue is a digitally-generated replca of your name, image, or likeness. Suppose, for example, a movie studio makes a digital copy of Brad Pitt and casts that copy in a movie? Can they do that? The technology for that isn’t quite there, but could be soon. However, the technology does exist to realistically replicate someone’s voice. You might mistake a digital replica of a distinctive voice—William Shatner’s, say—on the telephone. More frightening, you might mistake the replica of a politician’s voice for the real thing. The possibilities for damage are frightening to contemplate.

While state laws may provide some protection for NIL, there are currently no national standards. The US Copyright Office’s report of July 31 last deals with such digital replicas. The report concluded that there was an urgent need for national legislation to regulate this technology and to protect the use of name, image, and likeness for all citizens, not just celebrities.

Congress has yet to take up this issue. Doubtless they’ve been busy with more urgent matters.

In this newsletter, we discussed several conclusions from the recent reports from the US Copyright Office. These include the follwing findings:

The output of generative AI is not eligible for copyright protection.The prompt that resulted in the output of generative AI is not eligible for copyright protection.Documents with mixed content–partly original to the author and partly generated by AI–might be eligible for protection in whole or part by copyright.Current statutes and established procedures are adequate to resolve issues related to mixed content and copyright (i.e., no new legislation is needed).As with the introduction of other technologies, standards for mixed content will evolve through the application of precedents arising from specific cases (case law). Documention of the creative process will likely inform decisions in legal disputes involving mixed content and copyright.New legislation is urgently needed to resolve numerous critical issues related to digital replicas.The copyright office plans a third report regarding the databases that “teach” artificial intelligence. Many of these databases include material that is protected by copyright, and their use in producing the output from generative AI engines is is likely a violation, in whole or part, of said copyright. This third report, planned for later this year, will discuss the broad question of the use of copyrighted material in the training data for generative AI engines.

ReferencesCopyright and Artificial Intelligence, Part 1

Copyright and Artific i al Intelligence, Part 2

Copyright Law of the United States

An earlier version of this blog appeared as a newsletter by the author on Writing.Com.

January 18, 2025

It’s a Dog’s Life

What’s this post about?

Humans have created long-standing relationships with other species, but none are longer or, arguably, deeper than our relationship with dogs. They have been our companions for at least thirty thousand years. They are often beloved members of our families, and frequently play a role in our art and literature. Sometimes, they are even the protagonists in the stories we tell each other.

This newsletter is about using dogs and other non-humans to provide the point of view in stories. We start with some examples, then discuss briefly the how to do this, and finally end with why one should do this.

The Examples

More than one author has written from a dog’s perspective. An example that comes immediately to mind is Dean Koontz in his novel Dragon Tears. There’s one whole chapter written from a dog’s point of view. The dog’s world is filled with smells, and not just any smells. They are all interesting, and so very distracting. The dog is looking for something—I don’t remember what—but keeps getting sidetracked by these fascinating odors. The genius of the chapter is that, while dogs have eyes and ears, their sense of smell of smell is so refined, compared to humans, that it dominates their world view. Even a cat person like me can enjoy this chapter.

Another example of an author writing from a dog’s point of view is Harlan Ellison’s short story, “A Boy and His Dog.” The dog, Blood, provides the point of view as he and his human companion, Vic, scavenge items from a post-apocalyptic Earth. In fact, Blood is smart one of the pair, who share a telepathic bond. It’s more like Vic is Blood’s pet.

I mentioned I’m a cat person, so of course I like stories where a cat provides the point of view. Fritz Leiber wrote a delightful story, “Spacetime for Springers,” in which a super-smart kitten saves his family. I kind of ripped off Leiber’s idea in my silly story, “Schrodinger’s Cat” .

Science fiction offers multiple opportunities for alien points of view. Larry Niven, for example, in his short story “Rescue Party,” uses Nessus, his puppeteer alien, to provide the point of view. Other stories use the obligate carnivore species Kzin to provide the point of view.

Science fiction has long considered the possibility of intelligent machines, Asimov’s R. Daneel Olivaw was a robotic detective. See, for example, his novel The Naked Sun. For me, though, one of the most memorable stories where machine intelligence provides the point of view is Roger Zelazny’s “For a Breath I Tarry.” The story itself blends elements from literature, and especially from the first chapter of the Book of Job. But it also has echoes of the first three chapters of Genesis and of Goethe’s Faust. The title is from a phrase in A. E. Housman’s collection A Shropshire Lad.

Another fascinating set of machine intelligences appears in Keith Laumer’s Bolo stories. The Bolos are intelligent tanks invented by humans in a decades-long war with aliens. The story “Combat Unit” uses one of the units to provide the point of view. The plot is interesting all by itself, as the author uses events to ramp up tension and put us in the, er, mind of a Mark XXXI Combat Unit. Aliens have reanimated the unit from a long period of dormancy and hope to exploit it to win the war against humans. But the unit’s cunning and latent skills win the day. At the end, the unit signals for relief and realizes it will take humans decades to arrive. What it does then is what makes the story. It’s a short read and worth the effort.

The above examples are all from speculative fiction, but literature has examples, too. Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” is from the point of view of Gregor Samsa, a human who wakes up one morning transformed into an insect, usually taken by readers to be a cockroach. The story starts with him in bed and stuck on his back. Of course, since he’s a bug, that means he can’t get up. Rotten food is the only kind that appeals to him. The story is, of course, an extended metaphor. Wikipedia lists hundreds of other stories, movies, and works that this story inspired.

For another literary example, John Gardner’s novel Grendel is a retelling of the Old English Beowulf poem from the point of view of the monster. The authgor uses the novel as a platform for exploring the search for meaning in the world, the power of literature, and the nature of good and evil.

The How

In the writing state—the state of inspiration—the fictive dream springs up fully alive: the writer forgets the words he has written on the page and sees, instead, his characters moving around their rooms, hunting through cupboards, glancing irritably through their mail, setting mousetraps, loading pistols.

— John Gardner, The Art of Fiction

The above is just scattered list of stories that use non-human points of view. The specific techniques the authors use are as varied as the stories themselves. But there’s a more fundamental technique at work here, the “fictive dream” that Gardner speaks of. Gardner writes about the essential importance of inducing a fictive dream that plays in the readers’ heads. The words on the page induce this dream-like state, in which the readers fill in all the myriad details that never make it to the page but that the words suggest. The first step in creating that dream is that the author becomes a dreamer.

Becoming a dreamer means that the author first imagines what it would be like to be this different entity. Even with human characters, this almost always involves more than being a different person. There are always differences between the self and the other. The author’s dream must include physicality, gender, social context and myriad other factors. The cultural and moral context might differ, too. But for non-human characters, the entire range of sensory inputs, the reactions to those inputs, even the pace of those reactions could all be different. Truly unconventional points of view are not imitation humans. Indeed, the most interesting ones can’t be understood in human terms but are truly strange. Putting that alien, internal, and subjective experience on the page in a way that brings it to life in the readers’ imaginations requires craft and art.

But the first step, the essential step, is becoming a dreamer. That can’t be taught. It requires a deliberate loss of control. It’s much like a meditative state from which deeper insights arise. It takes practice and imagination.

The Why

Art is not what you see. It is what you make others see.

–Edgar Degas

Every time an author writes a story, there’s the necessity of being in the head of the characters, imagining how the fictional world acts to create their emotional state. It’s an essential element of the fictive dream, of becoming a dreamer. The character and the dreamer become one. This requires a kind of empathy for the fictional character. That’s hard enough for human characters, but if that character is non-human, it’s even more challenging. Writing from a non-human perspective makes an already hard task harder, so why do it?

The reason is that it’s one way to develop and deepen this necessary skill. It will stretch your writing skills and make you a better author. Like any useful exercise, it strengthens the underlying activity.

Indeed, empathy is an important life skill, one that can be a challenge in the real world, too. Empathy is probably an innate ability of humans. Alas, it’s one that political, religious, cultural and other barriers often work to stifle, sometimes for nefarious ends. Developing this skill as an author can develop it in real life, too. It can make your life more meaningful and fulfilling. Empathy, in one form or another, is a foundational value for a broad range of religious and etheical systems. I’ve found a useful rule is to conclude that if Socrates, Buddha, Muhammed, and Jesus all agree something is worth doing, it probably is.

All of the examples I cited achieve inducing the fictional dream in the reader. Well, all but my own, which is silly. The others are worth looking at just to learn from the specific craft these skilled authors employ. But the exercise itself, writing from a non-human perspective, is worthwhile on its own.

November 17, 2024

Judging a Story By Its Cover

Photo by Bo Peng on Unsplash

Photo by Bo Peng on Unsplash Everyone knows the old bromide about not judging a book by its covers. If it’s true, why do books even have covers? And why doesn’t anyone say the same thing about short stories? The answers involve marketing and return on investment.

MarketingI’ll tell you a secret. I hate marketing my fiction. In the first place, I’m not good at it. No, that’s not right. I’m horrible at it. In the second place, it’s a skill I have zero desire to learn. Understand, I generally like learning new things, but marketing? That’s boring. Even painful. I’d rather take golf lessons, or have root canal. Marketing combines the least attractive features of each.

This aversion to marketing is also self-limiting. I certainly would like people to read my stuff, but that necessarily involves marketing it, even if it’s just to an acquisitions editor. But successful self-publishing means going whole hog into marketing. Boring and painful. See above.

Thing is, while I’d like people to read my stuff, that’s not why I write. I write because I need to. Having readers would be a plus, but it’s not something I want to devote lifespan to obtain. When you get to my age, that lifespan thing becomes more important.

The good news is that for novels, a publisher has a marketing team. These are people who, for whatever unfathomable reason, enjoy marketing and are good at it. I still have to do some marketing to get a publisher, but not the soul-consuming, overwhelming parts that involve getting sales. The publisher will do that, and as nearly as I can tell, their souls are doing fine. It’s mine that gets devoured when I try to do something that’s unnatural to me.

Return On InvestmentWhich brings me short stories. (Sorry, that’s best transition I could come up with.)

Don’t judge a book by its cover. Back to the original questions. Why does everyone say this, and why doesn’t anyone say this about stories? (It’s always about books.)

Well, the second question is easy to answer. Stories are short. There’s not much money involved for anyone — author or publisher . Covers, on the other hand, are expensive. That means there’s insufficient ROI. (That’s return-on-investment, an abbreviation I’m almost ashamed to admit I know. See above about how I enjoy learning things.). As a consequence, stories don’t have covers. It’s all about the money.

That answers the second question. The first question, why do people say this about novels, is equally easy. It’s because this is exactly how people do choose what book to buy. More accurately, it’s the first step in how people choose what to buy. That’s the point of the photo at the top of this post. Whether you’re in a bookstore or browsing online, you have to first pick a book to examine. How do you do that? From the cover, of course. Because novels do at least have a chance to make money, the ROI is there to pay for the cover.

The Internet to the rescueBack to short stories — trust me, I’ve not lost the thread. A friend recently mentioned Medium.com to me. He’d posted some stories there and had actually made money. Well, admittedly, not much money. Less than a dollar. But he’d gotten readers, just for posting. That was what got my attention. The money didn’t matter. Even the royalties on my novels don’t matter to me. What I want is readers. Anyway, I decided to give Medium a try.

The first thing I noticed was that every story had a cover. It didn’t’ matter if it was a non-fiction article or a short story, they all had covers.

Confusing, right? There’s no ROI on hiring a cover artist. So where did all these covers come from?

When you post a story on Medium, it actually prompts you for a cover, and gives you a link to search for images on Unsplash.com. In case you didn’t’ know, that’s a place where artists publish their work. Artists, like authors, like having eyeballs on their work. Getting paid is nice, but not essential. So, there is a lot of beautiful artwork available for use on Unsplash. All you have to do is give appropriate credit to the source — and using Medium’s built-in search tool helpfully provides this.

I actually used a photo I found on Unsplash for the image at the top of this blog post, including the citation that Unsplash provides (and Medium copies, if I’d written this on Medium).

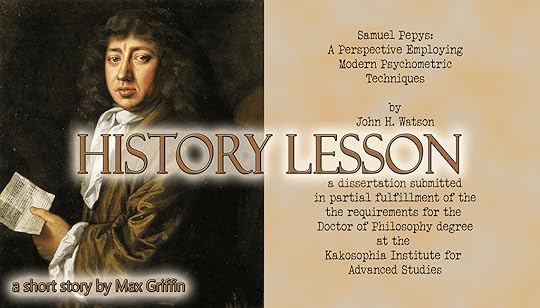

There are other places where you can find artwork for a minimal monthly fee. Unsplash has lots of links to iStock, for example. For another example, for $4 per month, I get access on CreativeFabrica.Com to artwork, fonts, and many other useful things. There are lots of other places to find artwork, either free or low cost. Many — but not all! — images on Wikipedia are public domain and, if they are, they include tools for properly citing the source. I used a Wikipedia image for this story, about unforseen dangers for a PhD candidate in history who uses AI to interview a simulation of Samuel Pepys:

Portrait of Samuel Pepys by John Hayls, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Samuel Pepys by John Hayls, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsBut…don’t use a random image you find via Google search. Google will produce many images that are not public domain and are not free for you to use. Using them without permission is plagiarism. The point of the sites mentioned above is that the images are public domain and/or the creators have given (or sold via, your membership fee) permission for you to use their work. Be sure to also properly cite your source.

Another possibility is to generate your own cover. If you’re like me, I can barely draw a stick figure, but there are AI tools that will generate an image from text that you provide. For example, on Designer.Microsoft.com, I entered the following text:

Picture of a run-down and boarded up red brick Victorian mansion on a bright afternoon. The mansion has an overgrown yard and round turret on left side of a wrap-around porch.

That gave me an image close to what I wanted. After some modest Photoshop manipulations, I got his image:

Image generated by Designer.Microsoft.Com

Image generated by Designer.Microsoft.ComThe story involves a haunted house that takes the protagonist back to 1906, so I bought a vintage-looking font from CreativeFabrica via my monthly subscription and used Photoshop tools to add the title, author byline, and to tweak the image a bit. The story itself is a post-modernist critique of modernity, if you’re into that kind of thing. It’s also a haunted house story.

Of course, doing these minor additions involves knowing a little about Photoshop. It also involved writing several different versions of the generating text before I got the exact picture I wanted. Note that the same text can, and probably will, generate different images on each use. There’s also a difference between “painting,” and “drawing.” See above about how I like to learn some new things.

The story’s only been up for a week, so I don’t know how effective the cover is. A cover is just one of the ways of getting noticed on Medium, and I’m still exploring those. In any case, the cover alone won’t get eyeballs. But the point is, there are ways to get a cover for your story that don’t involve low ROI.

But it’s AII’m not opposed to using AI tools. I use Word’s built-in tools to check grammar and related things all time. I am opposed to someone claiming that they created work that was in fact AI generated. All I here did was write the description, and I do take credit for that, for what little it’s worth (basically zero). I’ve also noticed that the same prompt gives different images. If you try the above prompt, you won’t necessarily get the above.

In passing, I’ve also noticed that about seventy percent of the time I describe a “handsome man” using the Microsoft tool, I get the same face as in this image. The other times I get a handsome guy with a different ethnicity, and they all look like each other, too. It’s almost impossible to get two handsome guys with same ethnicity and different faces in the same picture.