Max Griffin's Blog, page 3

December 11, 2023

The Tale of the Persnickety Aunt

The other day, I attended a forum sponsored by our local Metropolitan Library for “authors and aspiring authors.” As these things go, it was pretty good. One of the speakers—on editing—was a professor of writing at a local college. She opened her talk by asking us for questions that she might answer during her remarks—an interesting technique, and rather daring, too. I’m not sure I’d be prepared to ad lib a talk based on off-the-wall questions from the audience. You never know what they might come up with, like, say, the one I asked. But what got my attention was the way she answered one question in particular.

The QuestionOne of the participants, a published author, said he was working on a novel in which the plot called for one of the characters to make an unexpected choice. He wanted the choice to be surprising, but also to be one that, when it happened, readers would slap their foreheads and think I should have seen that coming.

Instead of giving possible techniques to accomplish this, the speaker told this story about her mother.

The Tale of the Mother and the Persnickety AuntAll her life—or at least as long the speaker could remember—her mother had been the family peace-maker. Whether at home, or with the extended family, or just in social gatherings, she was always the one to smooth over differences. She was always all about harmony. I was thinking “classic conflict avoidance,” but then I tend to be cynical.

She went on to describe another family member, an aunt, who always had to be right and who loved conflict. For example, if she asked you if you wanted a cookie and you said “yes,” then she’d say, “It’ll make you fat.” On the other hand, if you said “no,” then she’d say, “Are you afraid it’ll make you fat?” No matter what you answered, she was right and you were wrong. Charming. But then, we’ve all known people like this, which makes the persnickety aunt memorable.

There came a day when her mother’s beloved, if a bit quirky, brother went to his heavenly reward. Her brother, it seems, was an Oklahoma good old boy. He always wore bib overalls, flannel shirts, and cowboy boots. They were even his Sunday-go-to-meeting clothes. No doubt this appalled the persnickety aunt.

For his funeral, the speaker’s mother wanted to dress him as he would have chosen, in his cherished overalls and favorite red flannel shirt. The aunt, ever eager for conflict, insisted they purchase a suit and tie and dress him properly.

For the first time in anyone’s memory, the speaker’s mother didn’t back down. She fought tooth and nail to dress her brother the way he would have dressed himself, not the way the aunt wanted him to dress.

The speaker told us that, at first, she couldn’t understand why her Mother acted in such an uncharacteristic manner. Even her father paced back and forth in the family parlor, she said, in a quandary over this strange behavior.

But the speaker finally realized that her mother acted this way because, for the first time ever, the outcome of a conflict mattered.

Why This Answered the QuestionAfter telling the story, the speaker said, “Next question?”

That was it: her answer. In fact, not only was it a good answer, it was a brilliant ad lib response to the question.

Her answer is certainly better than the author jibber-jabber I would have given in response to that question. Her answer was an example, and showing is always stronger than telling.

Still, the mathematician in me yearns for that jibber jabber, so here it comes, like it or not.

Kurt Vonnegut said that every character should want something, even if it’s just a glass of water. All characters should have goals. The goals should matter: something bad should happen if the character doesn’t achieve their goal. This establishes the stakes. There’s no story unless the character also must overcome obstacles in pursuing their goal.

Goals and obstacles are in opposition, which gives rise to conflict. Because of the stakes, the outcome of that conflict matters. This gives rise to tension, the engine that drives the story. To add rising tension, authors can deepen the goals, raise the stakes, or increase the obstacles. The tension peaks at the climax where it finally releases with the character’s success–or failure–in achieving their goal.

Now consider the story of the mother and the persnickety aunt. The story tells us that family harmony is one of the mother’s enduring goals. If we were writing a short story, instead of telling this, we’d instead show it, revealing it through her words and deeds. Since it’s central to the dilemma she faces in the story, we’d show at least two incidents prior to the final arugment. Two establish a pattern, and the expectation of how she’ll act in the third incident when the persnickety aunt insists “no overalls, suit.”

But the mother has a second goal: honoring the memory of her beloved brother. Again, in a short story, we’d show this goal as well, in the same way, with two incidents.

Both sets of repeated incidents are not only establishing patterns, they foreshadow the events at the climax, when the mother stands up to the persnickety aunt.

The day of the fight over the overalls finally arrives. What’s the conflict? At first glance, it looks like it’s the fight between the mother and the aunt. But it’s more than that. The real conflict—the conflict that reveals how the story answers the original question—is in the mother’s heart. She has two conflicting goals: being true to her brother’s memory, or retaining a harmonious a relationship with the aunt. She can’t have both, since the aunt has to always be right. Each goal is the obstacle for the other. Her choice between the goals is the source of tension in the story, and it’s released when she chooses her brother.

ConclusionGoals, stakes, and obstacles. Tension rising.Two-to-make-a-pattern, three-to-break-it. Foreshadowing. Those are the ways I would have answered the question. Jibber jabber.

The tale of the mother and the persnickety aunt is way better.

The post The Tale of the Persnickety Aunt first appeared on Max Griffin.

October 15, 2023

Ghost Stories

Do believe in ghosts? If so, you’re in good company. According to the Gallup General Social Survey, 37% of Americans believe that houses can be haunted. Strangely, only 32% believe that the spirits of dead people, i.e., ghosts, can come back in certain places. That leaves one to wonder who or what might be haunting the houses of the 5% who believe in haunted places but not ghosts. Maybe Sasquatch. Or space aliens. Or perhaps the devil—the same poll showed that 42% of Americans believe the devil can sometimes possess people.

Some Personal Ghost StoriesI don’t know if I believe in ghosts, but I believe in ghost stories.

Most of us can repeat a story we’ve heard about a haunted location. I grew up in a small town in Eastern Iowa. A nearby state park featured a system of caves, including one with a flat floor and a massive domed ceiling. I recall my grandfather calling it the “Indian Council Cave,” and he told me that when he was a boy, he could still hear the native spirits chanting on the night of the fall equinox.

Another legend involved horse rustlers and the still-present echo of stolen hooves clip-clopping in the cave, so maybe horses haunt this place. I can tell you that late at night, when chill winds rush through the caves, one can imagine hearing a whispered chant or the distant splash of hooves in the stream that runs through the chamber.

My parents told me of depression-era dances with big bands that were held in the Indian Council Cave. One late summer’s night in the sixties while camping near the Indian Council Cave, one of my buddies was sure he heard the mellow tones of Moonlight Serenade on a distant trombone. At the time I was positive it had to be an eight-track in another campsite playing a Glenn Miller tape, but now I wonder.

My grandfather grew up in nearby Ozark, Iowa which is now a ghost town with only foundations of the old mill remaining. On a crisp fall day a few years ago we visited there and found the grave of my namesake, my great-great-grandfather, who perished in an accident in that old mill. Certainly, seeing a weathered grave from 1854 with my name on it was a haunting experience. No ghosts whispered in my ear that day, but my ancestor has since visited my dreams.

Historians and Ghost StoriesDid you know that historians sometimes use local ghost stories in their research? The stories can provide clues to actual events that happened in the past but were never part of an official record. Legends surrounding prisons or abandoned mental asylums where abuses might have occurred are so familiar they’ve become a trope for scary movies. Less so are extra-legal violations of justice such as lynchings. However, some historians see legends about a person wrongly killed as possible evidence of a forgotten—or suppressed—actual event. In many cases, a deep dive into contemporary diaries, correspondence, or newspaper accounts substantiates the suspicion.

In fact, there are scholars that study ghost stories. The ghosts in these tales, like any character in a good story, usually want something. Most of the time they want to be acknowledged, and they generally fall into one of three categories. There’s the furious return group, the leave me alone group, and we’re are still here group. The three groups are familiar to fans of ghost stories, whether folklore or fictional.

The furious return ghosts are out to avenge an intolerable injustice. These are the victims of lynchings, or tortures in involuntary confinements like insane asylums or prisons, or abusive families. In the real world, the only memory of their injustice might be a recurring legend. For example, studying a recurrent legend about a haunted hospital in north Chicago revealed to historians a long-forgotten and actual hospital (and later “poor farm”) that included thousands of unmarked and forgotten graves.

The leave me alone ghosts find their homes or other sacred places invaded by the modern world. This might be the spirits of Native Americans who find their sacred places usurped by moder-day tourists, or by depression-era dance bands, or even by nineteenth century horse rustlers. It might be an ancient burial ground turned into a modern subdivision with tract houses. Or it might just be a new family invading their home.

The we’re still here ghosts aren’t malevolent. Most often, they’re just around. There’s a local theater in Tulsa in which actors sometimes see, late at night after rehearsals, the ghost of the ballerina who owned the building that now houses the theater. She wears flowing robes and still dances. Legend has it that if you listen closely, you can hear the faint sigh of Claire de Lune in the distance. Sometimes these ghosts are beloved departed relatives, returned to guide their kin or just to provide assurance of their continuing love. Almost everyone has had dreams featuring beloved but departed relatives. The dreams are real, even if only as dreams.

Why Do We Tell Ghost Stories?An even more interesting question than “What do the ghosts want?” is “What do we want from the ghosts?”

Ghost stories arise from and respond to the fears and hopes of the living. We deplore injustice, fear being a victim, and long for justice. We want to know our lives touched others, we fear being forgotten, and hope to be remembered. We miss our departed loved ones, and we fear our own death, and hope for our redemption. Ghost stories animate our fears, our yearnings, and our hopes.

Like I said, I don’t know if I believe in ghosts, but I believe in ghost stories.

ReferencesGallup General Social Survey—paranormal questions.

Glenn Miller Band playing Moonlight Serenade

Coya Paz Brownrigg’s wonderful TED Talk inspired this essay.

Clair de Lune

The post Ghost Stories first appeared on Max Griffin.

October 3, 2023

What’s for Dessert?

Chocolate Chip Sugar Cookies

Chocolate Chip Sugar CookiesI usually make chocolate chip cookies based on oatmeal cookies. But I like sugar cookies, and I like shortbread, and stumbled across this recipe that combines those two and adds chocolate chips. They’re awesome!

I found this recipe on Let’s Dish , but modified it a bit to use Mini M&Ms and added almond extract. Also, I found it takes 11 minutes with my oven to cook the cookies, not 8-10; they don’t get done with 8-10 minues. But remember, every oven is different. I’ve checked the temperature on mine with an oven thermometer, so I’m pretty sure it’s accurate.

I’ve also used cookie scoops for this recipe. It makes it easier to get same-sized cookies, and is less messy. You can get an inexpensive set on Amazon for about $23. See link below. They’re great for other purposes, too, like making stuffed mushrooms.

I use extra-large 11″x17″ cookie sheets, and similarly-sized silicon mats. That lets me fit 15 cookies per sheet, and the silicon mats make sure they don’t stick. They also make the clean-up a snap.

The recipe calls for the butter to be at room temperature. This means leave the butter on the counter for about an hour before using it. Do NOT leave it out overnight, since it will be too soft. Also, do not try to “warm” it in the microwave–it will be too soft on the outside and still hard on the inside. The butter should be just soft enough that your finger leaves an impression when you press against it. When you whip butter at this level of softness, it aereates the sugars and gives you softer cookies.

PrintChocolate Chip Sugar CookiesCourse DessertPrep Time 30 minutes minutesCook Time 48 minutes minutesServings 60 cookiesEquipment1 Medium cookie scoop (#40/2TBSP/2OZ) Optional, but makes it easier to get uniform cookies.2 2 Cookie sheets, so you can load one while the other cooks I used four 11×17 sheets2 Silicon backing mats Optional, but it makes cleanup a snap and the cookies don't stick.Ingredients1 C butter at room temperature1 C Cooking Oil Canola oil by preference1 C Powdered Sugar1 C Granulated sugar2 TSP Vanilla exract1 TSP Almond extract4.25 C Flour1 TSP Cream of tartar1 TSP Baking soda1/2 TSP salt2.5 C Mini M&Ms2.5 C Chopped Pecans Mr. Gene likes pecans, but I prefer walnutsInstructionsPre-heat oven to 350 degreesCream the sugars, butter, and oil together.Add the eggs one at a time. Mix thoroughlyMix in the vanilla and almond extract.Sift the flour, cream of tartar, baking soda, and salt together.Add the dry ingredients in thirds to the sugars and eggs, mixing after each additionAdd the nuts and the M&Ms, mixing on low or with a wooden spoonUse Medium cookie scoop (#40/2TBPS/2OZ) to place cookies on sheet. Slightly flatten with a fork.Bake for 11-12 minutes. Check cookies–they should be slightly brown on the bottom. Cookies will slightly flatten and spread while they cook.Cool on the cookie sheet for at least ten minutes, then on wire rack. The cookies are fragile when they first come out of the oven, so let them set up before removing them from the rack.

PrintChocolate Chip Sugar CookiesCourse DessertPrep Time 30 minutes minutesCook Time 48 minutes minutesServings 60 cookiesEquipment1 Medium cookie scoop (#40/2TBSP/2OZ) Optional, but makes it easier to get uniform cookies.2 2 Cookie sheets, so you can load one while the other cooks I used four 11×17 sheets2 Silicon backing mats Optional, but it makes cleanup a snap and the cookies don't stick.Ingredients1 C butter at room temperature1 C Cooking Oil Canola oil by preference1 C Powdered Sugar1 C Granulated sugar2 TSP Vanilla exract1 TSP Almond extract4.25 C Flour1 TSP Cream of tartar1 TSP Baking soda1/2 TSP salt2.5 C Mini M&Ms2.5 C Chopped Pecans Mr. Gene likes pecans, but I prefer walnutsInstructionsPre-heat oven to 350 degreesCream the sugars, butter, and oil together.Add the eggs one at a time. Mix thoroughlyMix in the vanilla and almond extract.Sift the flour, cream of tartar, baking soda, and salt together.Add the dry ingredients in thirds to the sugars and eggs, mixing after each additionAdd the nuts and the M&Ms, mixing on low or with a wooden spoonUse Medium cookie scoop (#40/2TBPS/2OZ) to place cookies on sheet. Slightly flatten with a fork.Bake for 11-12 minutes. Check cookies–they should be slightly brown on the bottom. Cookies will slightly flatten and spread while they cook.Cool on the cookie sheet for at least ten minutes, then on wire rack. The cookies are fragile when they first come out of the oven, so let them set up before removing them from the rack.The post What’s for Dessert? first appeared on Max Griffin.

September 22, 2023

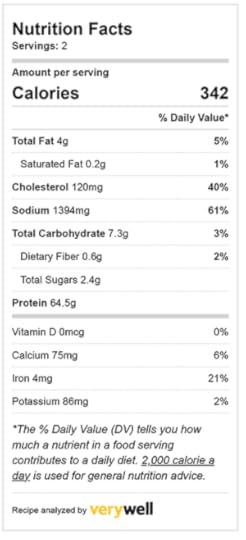

What’s for Dinner, 9/22/2023

Last week we ate out at the local Bonefish restaurant where I had a fabulous Chilean Sea B ass with an asian sauce. I liked it so much, I wanted to replicate it at home. However, Chilean sea bass is hard to find in Tulsa and expensive as well, so I’ve substituted grouper for tonight’s dinner.

ass with an asian sauce. I liked it so much, I wanted to replicate it at home. However, Chilean sea bass is hard to find in Tulsa and expensive as well, so I’ve substituted grouper for tonight’s dinner.

For a vegetable, I fixed crispy, dry-fried green beans. I used this recipe to fix those.

I’m using a new Analon X skillet. I like it loads better than the stainless steel one I bought last winter. It’s perfect for searing meats, and, unlike the stainless steel one, it’s easy to clean. It also helps to have a fish spatula for turning the filets. Finally, I used smoked salt and smoked pepper on the fish for enhanced flavor.

Mr. Gene hates fish, so I fixed a hamburger for him using Weigu ground beef, with Ore-Ida french fries for the vegetable. We both had a green salad, with baby spinach, Romaine lettuce, and watermelon.

PrintAsian inpsired, pan seared GrouperCourse Main CoursePrep Time 10 minutes minutesCook Time 10 minutes minutesServings 2 peopleIngredients2 Grouper filets approx 6 oz eachWhite wine to deglaze the panMarinade/Sauce2 tpsp soy sauce1 tbsp mirin May substitute any white wine1 tbsp avocado oil May substitute any cooking oil1 tsp rice vinegar May substitute any white vinegar4 packets splenda Substitute sugar or honey, to taste2 tsp minced ginger 1 tsp if using ground ginger4 cloves minced garlic 1 tsp if using powdered garlic, to taste1/4 tsp saltSauceHalf of the Marinade/Sauce mixture1 tbsp corn starch5 tbsp Chicken broth, divided or any mix of water, broth, and wineInstructionsDry filets with a paper towel and season with salt and pepper. (I used smoke-infused salt and pepper.)Combine all marinade ingredients and mix with a hand infuser or a blenderDivide marinade into two equal halves, in separate bowls or cups, one for the marinade and the other for the sauce. Brush all sides of the fish with the marinade. If there is any left over, do not mix it with the marinade reserved for the sauce–you don't want any residue from the surface of the fish getting into the sauce.Wrap the fish in plastic and let it rest for at least fifteeen minutes.Bring a skillet to medium-high heat. On my gas cooktop this takes four to five minutes. When it's hot, add enough avocado oil to the pan to cover the surface.Place the filets in the pan–they should sizzle when they hit the surface. If they have skin, place them skin-side down. Let them cook undisturbed for 4-5 minutes. The goal is a crispy sear on this side of the fish. Some blackening may occur from the sugars.Turn the fish over and continue to cook for two to three minutes. The fish should be flaky. Be careful–it can be fragile!Remove fish from the pan and place on a plate to rest. It will continue to cook from the internal heat. Reduce heat to medium. Whisk together the reserved portion of the marinade and four tbsp of the broth.. Add the mixture to the pan and bring to simmer.Whisk together the corn starch and the remaining one tbsp of broth and whisk this into the pan. It should thicken in thirty to sixty seconds.Swirl some sauce onto a plate and place the fish, seared side up, on top of the sauce.

Do not put sauce on top of the fish!

You want to preserve that crispy seared side that you created earlier, both for appearance and mouth feel. Notes

PrintAsian inpsired, pan seared GrouperCourse Main CoursePrep Time 10 minutes minutesCook Time 10 minutes minutesServings 2 peopleIngredients2 Grouper filets approx 6 oz eachWhite wine to deglaze the panMarinade/Sauce2 tpsp soy sauce1 tbsp mirin May substitute any white wine1 tbsp avocado oil May substitute any cooking oil1 tsp rice vinegar May substitute any white vinegar4 packets splenda Substitute sugar or honey, to taste2 tsp minced ginger 1 tsp if using ground ginger4 cloves minced garlic 1 tsp if using powdered garlic, to taste1/4 tsp saltSauceHalf of the Marinade/Sauce mixture1 tbsp corn starch5 tbsp Chicken broth, divided or any mix of water, broth, and wineInstructionsDry filets with a paper towel and season with salt and pepper. (I used smoke-infused salt and pepper.)Combine all marinade ingredients and mix with a hand infuser or a blenderDivide marinade into two equal halves, in separate bowls or cups, one for the marinade and the other for the sauce. Brush all sides of the fish with the marinade. If there is any left over, do not mix it with the marinade reserved for the sauce–you don't want any residue from the surface of the fish getting into the sauce.Wrap the fish in plastic and let it rest for at least fifteeen minutes.Bring a skillet to medium-high heat. On my gas cooktop this takes four to five minutes. When it's hot, add enough avocado oil to the pan to cover the surface.Place the filets in the pan–they should sizzle when they hit the surface. If they have skin, place them skin-side down. Let them cook undisturbed for 4-5 minutes. The goal is a crispy sear on this side of the fish. Some blackening may occur from the sugars.Turn the fish over and continue to cook for two to three minutes. The fish should be flaky. Be careful–it can be fragile!Remove fish from the pan and place on a plate to rest. It will continue to cook from the internal heat. Reduce heat to medium. Whisk together the reserved portion of the marinade and four tbsp of the broth.. Add the mixture to the pan and bring to simmer.Whisk together the corn starch and the remaining one tbsp of broth and whisk this into the pan. It should thicken in thirty to sixty seconds.Swirl some sauce onto a plate and place the fish, seared side up, on top of the sauce.

Do not put sauce on top of the fish!

You want to preserve that crispy seared side that you created earlier, both for appearance and mouth feel. Notes

The post What’s for Dinner, 9/22/2023 first appeared on Max Griffin.

September 17, 2023

The Gauntlet Runner

Every so often, I have the opportunity to read other authors whose work features LGBTQ characters. Recently, my friend J. Scott Coatsworth sent me his upcoming release, The Guantlet Runner.

There are lots of books out there featuring LGBTQ characters, but not so many that are science fiction, so I was especially pleased to see this one. It’s the second in a planned four book sci-fantasy series, the Tharassas Cycle , set on the recently colonized world of Tharassas. When humans first arrived on planet, they thought they were alone until the hencha mind made itself known. But now a new threat has arisen to challenge both humankind and their new allies on this alien world.

In the Guantlet Runner, we meet Aik who has fallen hopelessly in love with his best friend. But Raven’s a thief, which makes things… complicated. Oh, and Raven has just been kidnapped by a dragon. This launches a quest where Aik is off to hunt down the foul beast and make them give back his … friend? Lover? Soulmate? The whole not-knowing thing just makes everything more intriguing!

The book releases on September 27th, 2023 and comes highly recommended. Here’s a link to the series.

The post The Gauntlet Runner first appeared on Max Griffin.

Whodunnit?

I love mysteries, but that’s not what this newsletter is about.

Things happen in stories. Characters do things. When we write a story, we reveal who did what–whodunnit. How we reveal that is the topic of this newsletter. In particular the words and phrases we use can suggest or reinforce point of view and deepen the readers’ engagement with your fictional world.

The Fictional WorldCinema, theatre, and the written word all present fictional worlds. One artistic goal is to bring the fictional world to life in the imaginations of the audience. There is a deliberate collaboration between the artists creating those worlds and the audience who embraces them.

In cinema, the camera is the eye of the audience and the soundtrack is their ear. We not only hear the sarcasm in the actor’s tone, we see the scorn on her face. The director makes sure we hear and see these things by manipulating the camera, the soundtrack, and the mise en scene and by deploying the the Foley artist and myriad other components. Everything comes together in a seamless collaboration that includes us, the viewers, sitting in a dark theatre and experiencing the events as they transpire on the screen. Those events come alive in our imaginations. We become one with the fictional world.

Theatrical productions use many of the same tools, with staging and lighting replacing the camera.

In written fiction, we don’t have the diverse tools a director deploys. All we’ve got are words on a page. But what we do have is collaboration with our readers. The right words, deftly chosen, enhance that collaboration and breathe life into the scene. The right words place the reader inside our fictional world just as surely as good direction does in a movie or stage production. Poorly chosen words, on the other hand, distance the reader from the fictional world and make it abstract rather than concrete.

Words matter.

Point of ViewIn fiction, in effective fiction, each scene has a point of view. In the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, an omniscient narrator, standing outside the story looking in, often provided the point of view. There are many examples of great literature using this technique—Lord of the Flies or Pride and Prejudice, to name two of many possibilities. But modern fiction, especially commercial fiction, today overwhelmingly uses either third person limited or first person point of view. In third person limited, the author selects a single character in each scene to provide the point of view. The author puts the reader inside that character’s head and the reader then experiences the scene through that character.

In a well-crafted, third-person-limited story, the point-of-view character engages the readers’ imaginations. Point of view plays the same essential role in written fiction as the array of tools that the director deploys in cinema.

An ExampleThere’s a famous scene in Cheers where Diane and Sam have a fight in his office, each character showing increasing rage. In the background, we hear Norm and Cliff arguing about whether or not Wile E. Coyote is a metaphor for the Devil. Finally, Sam grabs Diane by the shoulders and they tell each other how they really feel. The heart of the scene is this exchange:

Disgusted, Sam said, “No guy in his right mind would want a babe that thinks like you.”

Diane said, “On behalf of all the babes in the world, whew!”

Sam shouted, “You drive me crazy. I can’t stand you.”

Diane screamed, “No, I can’t stand you.”

He grasped her by the shoulders and demanded, “Are you as turned on as I am?”

Helpless, she dissolved against him and cried, “Yes, my darling!”

I can imagine that the screenplay might have had dialogue somewhat like the above. As written, this could be in anyone’s point of view: Sam, Diane, or even Carla listening at the door and peeking through the keyhole. Declarative sentences convey all of the information. Even at the end, where she’s “helpless” and “dissolves” against Sam, the point of view could belong to any any observer.

The words and actions certainly have impact, and the precursor subtext of good-versus-evil in the background argument about Wile E. Coyte helps to add tension. However, adding a point of view to the exchange can transform the disagreement to one of dominance/submission, add emotional context, and add a character arc. Done with a bit thought, the point of view can add immediacy, intimacy, and tension.

Consider this modest change.

Sam rolled his eyes. Diane always acted like she was better than everyone. He sneered, “No guy in his right mind would want a babe that thinks like you.”

Diane gave an exaggerated swipe at her forehead. “On behalf of all the babes in the world, whew!”

Sam suppressed a growl at her mocking tone and clenched his fists. Instead of ringing her scrawny neck, he shouted, “You drive me crazy. I can’t stand you.”

Diane’s eyes flashed daggers and she screamed, “No, I can’t stand you.”

Sam grasped her by the shoulders. Her eyes, blue and blazing, consumed him. Impulse gripped him. Without thinking he demanded, “Are you as turned on as I am?”

Her body tensed against his before she surrendered to him and cried, “Yes, my darling!”

The words the characters speak are the same. The subtext—the argument over the Roadrunner cartoons—is still in the background. But in this version, Sam acts, thinks, and senses. He rolls his eyes, clenches his fists, and wants to ring her neck. He senses her body tense, then feels her “surrender.” Subjective descriptions reinforce that we’re in Sam’s head.

In the first version, the declarative sentences tell the reader what’s going on. But the second version doesn’t tell the reader Sam is disgusted, it shows it by having him roll his eyes. It adds, via free indirect discourse, Sam’s thought that Diane is stuck-up, which gives a reason for his anger and frames the conversation that follows. The opening now establishes Sam as the POV character, so whatever follows will be in his head.

We learn that Diane’s gesture is exaggerated and that it’s delivered in a mocking tone, both subjective descriptions in Sam’s head. We know that it makes Sam mad since he reacts: he clenches his fists and suppresses a growl. Then, “instead of ringing her scrawny neck,” he shouts at her. But the alternative action suggests that his anger is close to violence, adding tension when he later grasps her by the shoulders.

Next, we have Diane’s eyes “flash daggers.” We’re in Sam’s head, and so we see this as his subjective view of how her eyes look. When Sam grasps her shoulders, those eyes “consume” him—another subjective take how he’s feeling. Finally, we have Diane’s body “tensing” against his before she “surrenders,” both subjective ways of describing Sam’s sensations and his emotional reactions as he embraces her. This brings to closure the reason for Sam’s anger in the first place—Diane’s supposed feelings of superiority. It adds a character arc—his perceived triumph over the snooty Diane–to the mini-scene that’s absent in the dialogue-only version.

Of course, writing the scene from Diane’s point of view would have her feeling triumph over Sam, the exact opposite of Sam’s feelings. That disconnection, even as they share a passionate embrace, is the core dysfunction of their relationship and what makes it interesting.

Carla’s point of view would be different yet again. In her case, she’d be dismayed that the despised Diane has used her evil wiles to befuddle her hero, Sammy. She’d see each of the two characters’ actions in her own, unique and subjective way.

If this were a course I were teaching, I’d have two homework assignments, first to redo the scene from Diane’s POV and, second, to redo it from Carla’s. This isn’t a course, however, so I’ll leave it as an exercise for the interested reader.

ConclusionThe point of the last example—and this newsletter—is that how you frame descriptions and actions can reinforce and solidify point of view. It can also add tension and emotional subtext to a scene. The words you use to do this matter.

In principle, these ideas are simple. In practice, they are hard. I spent over forty years of my life as a professional mathematician. One thing this taught me about writing was that clear, precise, declarative sentences are at the heart of good mathematical prose. When I tried my hand at writing fiction, I soon learned that the one thing I thought knew for sure was wrong. This is still the biggest challenge I face in writing fiction, where clear, precise, emotive and subjective sentences are at the heart of good prose. Those declarative sentences I learned to write as a mathematician still sneak into my fiction, despite my knowing better.

Hopefully, you’ll have an easier time applying these ideas than I’ve had.

The post Whodunnit? first appeared on Max Griffin.

August 29, 2023

Strolling Through Genres

Why do readers like genres?

Readers like genres because they are familiar. Readers choose a genre because they’ve enjoyed other, similar books. They know more or less what to expect, and that helps them imagine the fictional world and the people who populate it. Going to a familiar genre can be like going home. Readers probably have friends who enjoy the same genres, so there can even be a sense of community. Fan fiction is a testament to this community.

Why do authors like genres?

Authors like genres because they provide a platform for world building and character types. Many genres have tropes that authors can exploit in constructing plots, creating quirky characters, and inserting tension. Genres offer opportunity for creatify by breaking expectations through violating or reversing reader expectations. In Ethan of Athos, Lois McMaster Bujold gives us a swash-buckling herione who rescues a prince-in-distress.

Even literary fiction can mine the resources of genre. Many calls for short stories specify genre, and many publishers specialize in genres. Whether you intend to write genre fiction or not, it’s worthwhile to know and understand at least some of the basics of a few genres.

Why do publishers like genres?

Genres help define the market segment, reader expectations, and comparable products. Some genres target speccific reader demographics rather than deploy specific fictional memes. For example, young adult and near adult are both recognized market segments that can use any of the genres listed in this stroll.

What’s here?

This is a survey of some of the major genres and their sub-genres. It’s eclectic rather than inclusive. People can’t even agree on what the genres are let alone the definitions, although the sub-genres are generally clearer. Moreover, many novels cross genres. The TIme Traveler’s Wife is both a romance and science fiction, for example. Is A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court a historical thriller or science fiction, or something else? Ultimately, it’s your call as author and reader.

The website TV Tropes has a great discussion of the tropes used in various genres. We’ve linked this website’s sub-sections in the genres we discuss below.

This is just one guy’s opinions on genres. It’s a start, but don’t take it as gospel.

Science FictionScience fiction usually refers to stories which explore how imagined scientific or technical discoveries change society and the everyday lives of people. There are many subgenres and cross-genre possibilities.

Dystopian/Utopian. Novels like Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four or The Dispossessed by Ursula LeGuin are examples of this sub-genre.

Space Opera. Star Wars, Star Trek, or Dune are all examples.

Alternate History. Star Trek is set in an alternate history. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle is an alternate history where the Nazis won WWII.

Cyberpunk. A form of dystopian alternate history. Johnny Mnemonic and Necromancer are examples.

Steampunk. A form of retro-futuristic alternate history based on nineteenth century technology. H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine or The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling are examples.

Military SF. These stories consider consequences of scientific or technical discoveries in a military context. Keith Laumer’s bolo series is an example, along with Jerry Pournelle’s Falkenburg books.

Romantic SF. Romance is the focus here. The movie Her is one example. The Time Traveler’s Wife is another.

Hard SF. These stories pay particular attention to scientific accuracy and logic. Examples are The Andromeda Strain or The Martian.

Soft SF. These stories may include scientific or technical advances without explaining the scientific basis or—sometimes—deal with so-called soft sciences like sociology or history. Examples might include light sabers in Star Wars, most faster-than-light drives, or Daniel Keyes’ Flowers for Algernon.

Time Travel. Stories involving travelling to different times, either in the future, the past, or both. These cross several other genres and subgenres, and are generally soft SF. Poul Anderson’s Time Patrol is an example.

Slipstream. When applied to SF, this might include interdimensional travel, or travel to another universe with different physical laws, or just a generally weird event. Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five is an example. Kafka’s Metamorphosis is another.

RomanceEvery romance story has two basic elements: a central love story and an emotionally satisfying and uplifting ending. Again, this basic form admits many crossover and subgenre possibilities.

Paranormal Romance. A romance that includes paranormal things, like ghosts or telepathy. Ghost is an example from cinema.

SciFi Romance. Any SciFi story can include the essential features of a romance. The Time Traveler’s Wife is certainly an example.

Contemporary Romance. Set in the modern world. The Notebook is an example.

Western Romance. Set in the US West, usually but not always in the late nineteenth century. Legends of the Fall and Brokeback Mountain would be two examples.

Gothic Romance. These stories have a dark atmosphere, filled with mystery, suspense, and—sometimes—supernatural elements. Wuthering Heights and Edward Scissorhands are examples.

Romantic Suspense. Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier or Fifty Shades of Gray are examples.

Regency Romance. These are romances set in the early nineteenth century, usually set in the British Isles, and usually inspired by Jane Eyre. The Regency is a period of British History from 1795-1837, although the official regency of George III only spanned the years 1811-1820.

Historical Romance. Any romance set in an historical era. E.M. Forster’s Maurce qualifies, as does Pride and Prejudice.

MysteryThere’s a crime to solve. There’s a detective to solve it. Infinite variations.

Noir/Hard Boiled. This darker form of mystery typically features an anti-hero detective battling a dark underworld and corrupt system. Works like Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and novels like those of Raymond Chandler typify the genre.

Cozy Mystery. Typically these include an amateur sleuth, set in small, intimate communities, and where sex and violence occur off-stage. Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series, or Lillian Jackson Brown’s Cat Who…series are examples.

Historical Mystery. Set in a past historical era. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose is an example.

SciFi Mystery. A mystery in a SciFi setting. Isaac Asimov wrote a series of stories with a robotic detective. Larry Niven’s Gil the ARM is a future detective who investigates harmful new technologies.

Police Procedural. These mysteries focus on police and forensic techniques. The CSI TV series is an example. Joseph Wambaugh wrote many in this genre, such as The Choirboys.

Hobby Mystery. This is a subset of the Cozy Mystery where the sleuth has a niche hobby or engages in a craft that is connected with the crime. The BBC series Lovecraft involved crimes where the protagonist’s expertise in antique restoration (and forgery) played a part. Sarah Atwell has a series of mysteries involving glass blowing.

Paranormal Mystery. The crime involves paranormal elements, or the paranormal helps to solve the crime. Stephen King’s Later is an example.

ThrillerA character in jeopardy dominates the plot. Pursuit, escape, and cliffhangers plague the characters. Suspense also characterizes these novels. There’s usually a dark and hostile person or group who threatens the protagonist. This genre readily crosses with myseries, romance, and science fiction.

Environmental Thriller These involve an environmental calamaty which may or may not be global in scope. One of the first examples was No Blade of Grass, an 1970 SciFi movie. Tourist Season by Carl Hiasson is another example.

Supernatural Thriller Thrillers with a supernatural element. Dean Koontz often writes in this genre–for example, Dragon Tears. Stephen King’s Carrie is another.

Historical Thriller A thriller set in an historical era. King’s 11/22/63 is one example. Ken Follet’s The Pillars of the Earth is another.

Medical Thriller Usually these are set in a hospital, involve medicine, and a protagonist who is a physician or knowlegeable about medicine. Robin Cook has made a career out of writing these. Michael Crichton’s Andromeda Strain is another exmample.

Psychological Thriller Here, the focus is on the mind–that of the criminal as well as the protagonist. Silence of the Lambs is an example. The Sixth Sense is an example from cinema.

Legal Thriller These focus on crimes, the law, lawyers, courtrooms, and the legal system in general. Many of John Grisham’s novels fall in this category. The 1985 Harrison Ford vehicle, Witness, is an example from cinema.

Spy Thriller These feature spies, secrets, double-crosses, and complex plots. The Bourne Identity, The Day of the Jackel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, and anything by Ian Fleming are examples.

Politcal Thriller Politics and politicians are the name of the game. The stakes are high, the opposition powerful, pervasive, and corrupt. Seven Days in May is an example, as is The Pelican Brief.

Techo Thriller Technology is the star–or the villain!–here, and the details are important, so get them right. Often these have SciFi elements as well. Dan Brown’s Digital Fortress, or Neal Stephenson’s Crytonomicon are examles.

Military Thriller It’s all about war and the people who fight them. Anything by Tom Clancy fits, but many authors write in this popular genre.

FantasyFantasy involves fantastic elements that can’t exist in real life. These can include magic, spirits, mythological creatures, beings from other dimensions or realms. Sometimes the story is set in an alternate fictional world, but sometimes the fantastic elements apppear in conventional settings.

Traditional Fantasy These have the feel of folk tales, tall tales, fairy tales, fables, myths, and legends. They often include fairies, elves, trolls, and other creatures of myth and lore. Lord of the Rings is an example of this kind of fantasy.

Urban Fantasy The supernatural arises in a contemporary urban setting. The supernatural can be mythic creatures or just wierd and spooky. The protagonist often has a foot in both worlds, and the contemporary world often borrows from the noir tradition. Jim Butcher’s The Dresden Files is an example. The 1970s TV series Kolchak was a comic version of the sub-genre.

Contemporary Fantasy Urban fantasy without the urban setting. The Twilight series is an example.

Historical Fantasy Fantasy in the past. The Book Theif, by Markus Zusak, is an example. Bergman’s The Seventh Seal is an example from cinema.

Horror Here, the purpose is to create feelings of dread, repulstion, and fear in the reader. Horror can be a sub-genre of thriller, too, but it often involves supernatural elements, as in The Shining.

Super Heros Whether it’s Spiderman, Superman, or Wonder Woman, super powers are fantasy. Hollywood cranks out endless examples. New and fresh appears to be not required for the Hollywood versions, but these can provide multiple opportunities for originality and creativity. Super-heros might also fit in the SciFi category, depending on whether the author makes a nod to science in explaining the super-powers (Superman and Spiderman, for example) or uses mythology or some other similar basis as an explanation (Wonder Woman).

Slipstream We included this in SciFi, too, for cross-dimensional travel. In fantasy, it might involve visiting magical realms, distinct from our contemporary, humdrum world. Wierd is another characteristic of slipstream. Borges’ The Aleph and Other Stories is a literary example.

High/Epic Fantasy The setting isn’t Earth as we know it, and certainly isn’t now. Whatever it is, there are supernatural forces that threaten its existience, or at least the existence of the protagonists. Supernatural forces may also be the saviing grace of the protagonists. Andre Norton’s Star Gate is an example. Better known would be Game of Thrones.

Paranormal Paranormal stories involve elements outside of conventional reality that have concrete, observable consequences in the fictional world. Most stories with vampires or werewolves fit this definition, as do most stories with extra-sensory perception. Many ghost stories do as well. There may be an initial mystery about what’s going on, but eventually all is explained through a reveal of who–or what–is causing the paranomral element.

Supernatual Supernatural stories are similar to paranormal, except that the source of the paranormal/supernatural element is unknown and, ususally, unknowable. Many ghost stories fall in this category–was that really a ghost or just an hallucination? Stories about the afterlife, the soul, or gods are other rexamples. The source of the supernatural remains a mystery. These stories take to heart the words of physicist Arthur Eddington: The world is not only stranger than we imagine, it’s stranger than we can imagine.

The post Strolling Through Genres first appeared on Max Griffin.

July 24, 2023

Characters and Plots and Themes, Oh My!

Themes? We don’t need no stinking themes.

No, John Huston never used that line in one of his movies. But the iconic line about badges from his screenplay for Treasure of the Sierra Madre reflects one of the themes of the movie, namely the lawless character of the frontier.

Huston was a smart guy. He knew that stories need themes. In fact, the theme is the soul of the story.

When I first started writing these monthly columns, I was full of ideas for topics. But you can only write about free indirect discourse or the singular they so many times before these ideas become stale. That’s where you, the readers, come in.

Last month I got a great suggestion. A reader wrote to me saying she had difficulties with themes in her fiction and wondered if I could write about that.

The first thing that occurred to me was to just create a list of possible themes. You know. Things like love, death, family, and so on. A better list might be one that listed conflicts. Things like good versus evil, duty versus honor, change versus tradition. It’s not hard to come up with lists like this. Google “themes in literature” and you’ll get over a billion hits. Too many to be useful. I wasn’t thinking properly about the reader’s question.

So what is the question?I think what that reader was really asking me was how to connect the theme to the story.

That’s trickier. How do we come up with lines like the one Huston used in Treasure of the Sierra Madre? Huston was certainly a genius, but mere mortals can do this, too–perhaps with less panache, but we can do it. It just takes thinking things through. It also helps to be willing to go back and tweak your initial drafts. There are some basic ideas to keep in mind as you do this, and that’s what this newsletter is about.

Lists like you find in a Google search just give examples of themes. However useful these examples might be, a list is not a definition.

What is a theme, anyway?Sure, the theme is the soul of the story, but that’s too general to be helpful. To answer the question about connecting theme and story, we need to first ask, “what is a theme, anyway?” We need a working definition.

Here’s one from Sara Letourneau that is both precise and helpful.

A theme is an idea, concept, or lesson that appears repeatedly throughout a story, reflects the character’s internal journey through the external plot, and resonates with the reader.

There’s a lot to unpack in that definition. First, it supposes a character arc—an internal journey during which the character changes over the course of the story. It further supposes that the events in the plot cause, or at least coincide with, the character arc. Finally, it supposes that the reader connects with the character.

A less abstract version is that there is a life lesson the character needs to learn. The readers need to like the character enough to care about whether or not she succeeds–to cheer for her. The character resists learning the lesson, which leads to conflict. Conflict leads to plot. This conflict repeats over and over again in the story, with escalating stakes. The ultimate resolution of the conflict occurs at the climax, when everything is on the line, and the character learns (or does not learn) the lesson.

Think about The Wizard of Oz. The main theme is easy: there’s no place like home. At the start, Dorothy wishes she were anywhere except home. Then a whirlwind whisks her away to Oz. Once there, she wants to return to Kansas, even though she hates the place. She meets other characters. They all need things, too, and those needs coincide with other themes in the story. The things that the Lion, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man need are all things Dorothy also needs in her quest to escape Oz. Ultimately, though, these don’t matter. She can’t return home until she learns the basic lesson of the theme. Then her goal is just a click of her heels away.

For another example, consider The Maltese Falcon. If you haven’t read the novel by Dashiell Hammett, the movie is available online and is worth watching. As an author, the lessons you’ll learn relate to connecting theme, character, and plot.

Hammett’s novel has many themes. On one level, it’s an exposition on the importance of having a strong personal code of ethics in a world lacking both ethics and the ability to catch the real criminals. But the strong underlying life lesson that the protagonist, Sam Spade, learns is the corrupting influence of greed.

Greed animates all of the characters in the novel. Spade is always on the lookout to make a quick buck, and he’s not picky about how he does it. His erstwhile client, Brigid, has killed Spade’s partner and double-crossed her own accomplice-in-greed to acquire the eponymous Falcon. Casper Gutman, played brilliantly by Sydney Greenstreet in the movie, represents the ultimate in greed. His compatriots call him “Mr. G” because of his copious gut, thus conflating greed and gluttony. His jewel-studded pistol also represents his greed, and further suggests a connection between greed and violence. Gutman even betrays his surrogate son (and possible lover) in his quest for the Falcon. The connections between the theme, the characters, and the plot are both obvious and pervasive.

But Spade’s character arc reflects the theme and the plot as well. Early on, his office assistant, Effie Perine, tells Spade she’ll never respect him if he accepts money without offering to help Brigid. She’s symbolically representing Spade’s conscience. Eventually, he’s offered and even accepts a bribe from Gutman. Ultimately, he turns the bribe over to the police to use as evidence against Gutman, closing his character arc by refusing, at least in this instance, his greedy impulses and acting for the greater good. He’s learned the life lesson.

The Falcon itself is a crucial element of the story. All the characters are convinced that it’s the source of the ultimate in untold riches. But in the end, it turns out to have no value at all. The Falcon is a metaphor for the futility of greed—even if you attain the goal, it will be of no value.

Working backwards, it’s not hard to spot the ways that Hammett connects his theme to Spade’s internal journey and to the events of the plot. Spade himself is a quirky, underdog character readers want to identify with and cheer for. Hammett’s theme fits the above definition nicely.

You might wonder if Hammett had all of this in place when he started writing. We can’t ask him, so we’ll never know. But he didn’t have to have these ideas in place when he started writing. More likely, he was initially just interested in writing a gripping detective novel. He might have had “greed” as one of several themes, or maybe he just wanted to write about an underdog detective working in a corrupt and incompetent system. He could have discovered the theme of greed in the course of writing the story, and then reinforced it in subsequent revisions.

I know that when I write a novel, I have a general idea of the themes I want to cover. But at the start, I don’t know my characters, and only have a general idea of the plot. I learn about my characters as I write them, and the life lessons they need to learn become apparent in the creative process. That sets up their character arcs and influences how the plot develops.

Other authors have different methods. There are plotters, people who start with fully developed character sketches and detailed plot outlines. Then there are pantsers, people who write by the seat of their pants. I’m firmly in the latter category. There’s nothing wrong with either method—most people are probably a mix of the two. Pick whatever method works for you.

Your characters and your plot give you opportunities to show links to the theme. Your job is to find and highlight them. Don’t preach, show. Connecting your themes with your story involves showing the theme in action. It’s the words and deeds of the characters that bring the story and its themes to life.

That synthesis, that bringing together of character, plot, and theme, that’s the soul of the story.

The post Characters and Plots and Themes, Oh My! first appeared on Max Griffin.

July 10, 2023

What’s for Dinner-Garden Edition

We’re continuing to get Stuff from Mr. Gene’s garden. In addition to cucumbers, we’re getting squash and tomatoes. Lots of tomatoes.

We’re continuing to get Stuff from Mr. Gene’s garden. In addition to cucumbers, we’re getting squash and tomatoes. Lots of tomatoes.

Today I’m going to feature two recipes. One for a cucumber and apple salad, and the other for a cucumbers and tomato salad.

I know what you’re thinking–these combinations sound ghastly. It turns out that they are both pretty tasty, much to my surprise. I’ve even done a squash and tomato dish that turned out to be pretty good, but that’s for another day.

For the cucumber and apple dish, I used my mandolin to make apple and cucumber sticks. My mandolin has a guard on it to protect fingers, but I’m a klutz so I use kevlar gloves to protect my fingers. I purchased both my mandolin and my kevlar gloves on Amazon. In case I’ve not mentioned it before, I’ve also got an awesome garlic press. My latest favorite kitchen gizmo is a microplane lemon zester, all used in at least one of these recipes.

With these tools, the prep is pretty easy. For both salads, cut the ends off of the cucumbers, then slice them in half length-wise. Next, scoop out the soft interior and the seeds. For cucumber sticks, trim the halves so they’ll fit in the mandolin’s hopper, and put them in the hopper skin-side up. In no time, you’ll have perfect sticks. Core your apple and do the same thing.

The other salad is even easier. You still get rid of the seeds and soft core in the cucumber, but then cut the parts in half-inch to three-quarter-inch chunks. You’ll cut the tomatoes into similar chunks. We had ginormous beefsteak tomatoes, so I cut them in half first, removed the stems, then quarered each half. Halving the quarters gave bite-sized chunks.

The tomato/cucumber salad calls for sliced onions–another chore made easy with a mandolin. I used the thinnest setting, then cut the resulting disks in half, rotated ninety degrees, and cut them in half again to bite-size onion bits.

PrintCucumber Apple SaladCourse SaladPrep Time 5 minutes minutesServings 2Equipment1 MandolinIngredientsDressing2 TBSP Olive Oil1 Lemon2 Packets Splenda, or 2 TSP sugar (optional)1 TSP ground fennel or ground anise (optional)dash saltSalad1 Cucumber, cut into sticks1 Apple, cut into sticksSalt and pepper to tasteInstructionsZest the lemon into a small mixing bowl.Juice the lemon into the same small bowlAdd the olive oil and any spicesAdd the sweetener, if using. You can add later after mixing the salad if the lemon makes it too tart.Thoroughly mix the dressing into the salad.Allow to sit about five minutes for the flavors to mesh.

PrintCucumber Apple SaladCourse SaladPrep Time 5 minutes minutesServings 2Equipment1 MandolinIngredientsDressing2 TBSP Olive Oil1 Lemon2 Packets Splenda, or 2 TSP sugar (optional)1 TSP ground fennel or ground anise (optional)dash saltSalad1 Cucumber, cut into sticks1 Apple, cut into sticksSalt and pepper to tasteInstructionsZest the lemon into a small mixing bowl.Juice the lemon into the same small bowlAdd the olive oil and any spicesAdd the sweetener, if using. You can add later after mixing the salad if the lemon makes it too tart.Thoroughly mix the dressing into the salad.Allow to sit about five minutes for the flavors to mesh. PrintTomato and Cucumber SaladCourse SaladPrep Time 5 minutes minutesServings 2IngredientsDressing2 TBSP Olive Oil1 TSP Balsamic vinegar2 TSP sugar (I used two Splenda packets)1 clove garlic, minced1 LemonSalad1 cucumber, seeded and cut into chunks2 tomatoes, cut into chunks1/2 C Fresh basil 1/2 C Italian Parsley1/4 C mint1/2 Red onion, sliced thinly and then roughly choppedInstructionsPlace oil, vinegar, and minced garlic in small mixing bowl.Zest the lemon into the same bowl.Juice the lemon and add to bowlAdd sweetener and thoroughly mix. You can add more later once the salad is mixed.Add the dressing to the salad and thoroughly mix so that the dressing covers all the ingredients. It shouldn't need more sweetener, but taste it to be sure. Besides, it's yummy.Let the ingredients sit for at least five minutes so the flavors blend. If it'll be more than five minutes, refrigerate it. I don't recommend refrigeratoring it overnight, as the tomatoes and cucumbers will lose their liquid.

PrintTomato and Cucumber SaladCourse SaladPrep Time 5 minutes minutesServings 2IngredientsDressing2 TBSP Olive Oil1 TSP Balsamic vinegar2 TSP sugar (I used two Splenda packets)1 clove garlic, minced1 LemonSalad1 cucumber, seeded and cut into chunks2 tomatoes, cut into chunks1/2 C Fresh basil 1/2 C Italian Parsley1/4 C mint1/2 Red onion, sliced thinly and then roughly choppedInstructionsPlace oil, vinegar, and minced garlic in small mixing bowl.Zest the lemon into the same bowl.Juice the lemon and add to bowlAdd sweetener and thoroughly mix. You can add more later once the salad is mixed.Add the dressing to the salad and thoroughly mix so that the dressing covers all the ingredients. It shouldn't need more sweetener, but taste it to be sure. Besides, it's yummy.Let the ingredients sit for at least five minutes so the flavors blend. If it'll be more than five minutes, refrigerate it. I don't recommend refrigeratoring it overnight, as the tomatoes and cucumbers will lose their liquid.The post What’s for Dinner-Garden Edition first appeared on Max Griffin.

June 27, 2023

What’s for Dinner

Yesterday, Mr. Gene left four huge, ripe cucumbers on the kitchen counter for me, fresh from the garden. I like cucumbers, and was glad to get them, but what can I do with four of the things?

Yesterday, Mr. Gene left four huge, ripe cucumbers on the kitchen counter for me, fresh from the garden. I like cucumbers, and was glad to get them, but what can I do with four of the things?

Most of the recipes I found online were for salads. These looked good, and I’ll certainly try them out. But I wanted to find more creative ideas.

That’s when I found coodles.

What are coodles, you ask? They are cucumbers spiralized into noodle-like strands. When you do this with zuchinni, they are called zoodles, so when you do it with cucumbers, they are called coodles.

I thought this was at least worth a try, and it actually worked out pretty well. At least Mr. Gene liked it, and he’s always dubious when I try new recipes.

I used the spiralizing attachement for my KitchenAid mixer on the cucumber. I was worried that the cucumber might be too soft for the gripper to keep it in place while spiralizing, but it worked just fine. I did this first, and got a nice pile of coodles plus a pile of seeds. I put them in a colander to drain the moisture, discared the seeds, and them put them between paper towels to dry off.

For the most part, the spiralizer works pretty well. I’ve made poodles (spiralized pears), and I’ve used it to slice apples, pears, cucumbers, and other things into slices. The one attachment that broke almost the first time I used it was the apple pealer, but I’ve got a hand-cranked pealer that works like a charm and makes apple pies easy to fix.

For the main course, I decided to whomp up some sesame chicken. For no other reason than wanting to use the meat grinder attachment for my KitchenAid mixer, I decided to grind two small chicken breasts and three skinless chicken thighs. Easy-peasy, except of course for cleanup. Luckily, everything can go in the dishwasher. There are lots of recipes for sesame chicken online, and I’ve made them often enough I can ad lib them, which is what I did here.

In any case, I found a novel use for one of the cucumbers, and it worked out pretty well. The coodles added a hint fresh cucumber flavor, but they also absorbed the sauce from the chicken. Together, they made an interesting combination, one that I’d be willing to try again even if I didn’t have an over-supply of cucumbers.

PrintSesame Ground Chicken with CoodlesSpiralized cucumber provides a novel base for this otherwise routine asian chicken recipe.Course Main CourseCuisine ChinesePrep Time 10 minutes minutesCook Time 15 minutes minutesServings 4Equipment1 Spiralizer1 Hand infuser (optional)IngredientsSauce1/3 C soy sauce1/4 C Chicken broth2 TBSP Shaoxing Wine (any white wine will do)2 TBSP Honey (I used Spenda)1 minced garlic clove1 TBSP Corn Starch1 TBSP Water or Chicken BrothFor main Dish1 Cucumber1 lb ground chicken2 Garlic Cloves, minced2 tsp Olive Oil1/2 C diced onion2 Green onions–green part only1/4 C Sesame seeds1 TBSP Sesame oil (I omitted this for a low-calorie version and it tasted fine)InstructionsSpiralize the cucumber to make coodlesDrain cucumber in collandar and discard the seeds. Dry on paper towels for about ten minutes. By the time you're done with the rest of the steps, the coodles should be dry.Heat skillet over medium heat. Don't add oil or other ingredients until skillet is hot–about five minutes. While you wait for the pan to heat, mix the sauce.Place all sauce ingredients except the corn starch and the last tablespoon of liquid in a small bowl and mix together. You'll add the corn starch tablespoon of liquid later. If you are using sesame oil, you'll need to use a hand-infuser to thoroughly mix the oil and the other ingredients. Add olive oil to skillet–it should shimmer if the skillet is hotAdd onions and stir until softened–three or four minutesAdd minced garlic to pan. Heat until fragrant–about a minute.Add ground chicken to pan. Stir occassionally until cooked, about five minutesMIx together 1 TBSP water or chicken broth and 1TBSP corn starch, then add to the sauce and stir. Add the sauce to the skillet with the meat and onions and stir until the sauce thickens and coats the meat–a couple of minutes.Separate the coodles into two piles and place each on a dinner plate. Top top with chicken and sauce, then sprinkle with sesame seeds and green onion tips.NotesThe cucumber from our garden was huge–normal length, but maybe twice the thickness of a store-bought cucumber. If using one from the grocery store, you might need two cucumbers to get enough coodles.The low-calorie version–no oil and Splenda instead of honey–works out to about 400 calories per serving.

PrintSesame Ground Chicken with CoodlesSpiralized cucumber provides a novel base for this otherwise routine asian chicken recipe.Course Main CourseCuisine ChinesePrep Time 10 minutes minutesCook Time 15 minutes minutesServings 4Equipment1 Spiralizer1 Hand infuser (optional)IngredientsSauce1/3 C soy sauce1/4 C Chicken broth2 TBSP Shaoxing Wine (any white wine will do)2 TBSP Honey (I used Spenda)1 minced garlic clove1 TBSP Corn Starch1 TBSP Water or Chicken BrothFor main Dish1 Cucumber1 lb ground chicken2 Garlic Cloves, minced2 tsp Olive Oil1/2 C diced onion2 Green onions–green part only1/4 C Sesame seeds1 TBSP Sesame oil (I omitted this for a low-calorie version and it tasted fine)InstructionsSpiralize the cucumber to make coodlesDrain cucumber in collandar and discard the seeds. Dry on paper towels for about ten minutes. By the time you're done with the rest of the steps, the coodles should be dry.Heat skillet over medium heat. Don't add oil or other ingredients until skillet is hot–about five minutes. While you wait for the pan to heat, mix the sauce.Place all sauce ingredients except the corn starch and the last tablespoon of liquid in a small bowl and mix together. You'll add the corn starch tablespoon of liquid later. If you are using sesame oil, you'll need to use a hand-infuser to thoroughly mix the oil and the other ingredients. Add olive oil to skillet–it should shimmer if the skillet is hotAdd onions and stir until softened–three or four minutesAdd minced garlic to pan. Heat until fragrant–about a minute.Add ground chicken to pan. Stir occassionally until cooked, about five minutesMIx together 1 TBSP water or chicken broth and 1TBSP corn starch, then add to the sauce and stir. Add the sauce to the skillet with the meat and onions and stir until the sauce thickens and coats the meat–a couple of minutes.Separate the coodles into two piles and place each on a dinner plate. Top top with chicken and sauce, then sprinkle with sesame seeds and green onion tips.NotesThe cucumber from our garden was huge–normal length, but maybe twice the thickness of a store-bought cucumber. If using one from the grocery store, you might need two cucumbers to get enough coodles.The low-calorie version–no oil and Splenda instead of honey–works out to about 400 calories per serving. The post What’s for Dinner first appeared on Max Griffin.