Peter Smith's Blog, page 61

March 5, 2020

Some IFL2 exercises

Thirty-seven of the forty-two chapters of IFL2 have sets of exercises at the end. So that’s many merry hours to be spent, putting answers to all the exercises online. What joy. And yes, this is pretty time-consuming, to say the least.

But, when taken just a chapter or two at a time, writing up the answers without worrying too much about typographical niceties is quite diverting. And unlike the business of writing the book itself, it is not at all stress-inducing — after all, any slip-ups or silly mistakes or other infelicities can be instantly corrected when noticed, rather than being preserved for ever in embarrassing print.

Here then is the slowly growing page with links to (1) some of the sets of exercises, and then to (2) corresponding sets of answers. Since the exercises are available independently of the book, many of these sets with their answers could eventually be useful to students even if they are not actually using IFL2.

The most recent additions are two sets of questions covering propositional natural deduction proofs for negation and conjunction, and then for disjunction too, with extensive answer sets — talking through strategies for finding the solutions rather in the manner of an examples class. Next up, examples for proofs using the conditional, and more. Watch this space.

The post Some IFL2 exercises appeared first on Logic Matters.

Some more IFL2 exercises

Thirty-seven of the forty-two chapters of IFL2 have sets of exercises at the end. So that’s many merry hours to be spent, putting answers to all the exercises online. What joy. And yes, this is pretty time-consuming, to say the least.

But, when taken just a chapter or two at a time, writing up the answers is quite diverting. And unlike the business of writing the book itself, it is not at all stress-inducing — after all, any slip-ups or silly mistakes or other infelicities can be instantly corrected when noticed, rather than being preserved for ever in embarrassing print.

Here then is the slowly growing page with links to (1) some of the sets of exercises, and then to (2) corresponding sets of answers. Since the exercises are available independently of the book, many of these sets with their answers could eventually be useful to students even if they are not actually using IFL2.

The most recent additions are two sets of questions covering propositional natural deduction proofs for negation and conjunction, and then for disjunction too, with extensive answer sets — talking through strategies for finding the solutions rather in the manner of an examples class. Next up, examples for proofs using the conditional, and more. Watch this space.

The post Some more IFL2 exercises appeared first on Logic Matters.

March 3, 2020

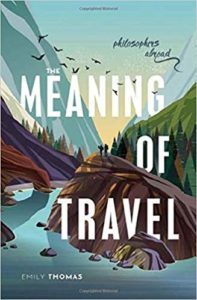

The Meaning of Travel

In mid December, the Uffizi can be almost empty of visitors. One year, we were sitting very quietly for some time in what was then the room with the great Botticelli paintings. A few other visitors came and went. But then there was a sudden flurry of noise; and from one corner of the room entered a group of young Chinese, each with their headset, with a guide talking into a microphone. The group processed without pausing to the opposite corner and left as quickly as they had arrived. The scene was saddening and comical — what was the point? But then the thought strikes: are our Florentine visits in recent years really much better? They are still fleeting; our knowledge and understanding of what we are seeing is still shallow; yes, we know the restaurants and cafés the locals like; but we are skimming along the surface. What is the meaning of our travel here?

In mid December, the Uffizi can be almost empty of visitors. One year, we were sitting very quietly for some time in what was then the room with the great Botticelli paintings. A few other visitors came and went. But then there was a sudden flurry of noise; and from one corner of the room entered a group of young Chinese, each with their headset, with a guide talking into a microphone. The group processed without pausing to the opposite corner and left as quickly as they had arrived. The scene was saddening and comical — what was the point? But then the thought strikes: are our Florentine visits in recent years really much better? They are still fleeting; our knowledge and understanding of what we are seeing is still shallow; yes, we know the restaurants and cafés the locals like; but we are skimming along the surface. What is the meaning of our travel here?

Emily Thomas’s new book The Meaning of Travel perhaps didn’t full answer my question. But it is a real delight. It’s a relatively short book, very nicely produced by OUP — in a small format too, so it will appropriately fit in a jacket pocket on your travels, if only as you stride across the common to your favourite coffee bar to read it. But perhaps that too can be travel, in a miniature way? In my case, the coffee bar is run by Italians, the chatter is in Italian, the radio is Italian, the coffee and dolci are Italian, most of the other customers are non-English. Part of the pleasure, then, is relishing the slight otherness (albeit very safe and tame!): and as Emily Thomas suggests, “the difference between everyday journeys and travel journeys lies in how much otherness the traveller experiences”. The businessman who hops on a plane to Hong Kong, spends two days cloistered in meetings held in English, stays with colleagues in an international hotel chain, and is pampered again in business class as he flies home hasn’t really travelled, we feel.

The book is written with a light touch. There are a dozen engaging essays; on maps, for example; on how traveller’s tales challenged thoughts about innate ideas; on why mountains changed from forsaken places full of dangers to be avoided (Donne’s “warts and pock-holes on the face of th’earth”) to become places of spendour where you could encounter the sublime; on the idea of wilderness and our relation to nature (or Nature). Some of the usual philosophical suspects appear in familiar stories (Bacon, experimenting to the last, stuffs a chicken with snow, and catches a fatal chill; Descartes, never really settling in one place, travels to wintry Stockholm and dies of flu or perhaps pneumonia). But there are many less familiar philosophers here, on real or imagined journeys (I was intrigued by Margaret Cavendish’s bizarre-sounding Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World). And sprinkled through the book are snippets from Emily Thomas’s obviously lovingly assembled scrapbook of quotations and illustrations (travel adverts and posters for example). It all makes for a fun and thought-provoking read.

In her last section, “Returning Home: Top 10 Vintage Tips”, there’s a quotation from Descartes, in which he remarks of his reading that “conversing with those of past centuries is much the same as travelling”. That’s a thought which could have made for another intriguing essay on the relation between our travelling from place to place and our travelling (as best we can) from time to time. And indeed are these not often bound together? When we (at least, the “we” who are likely to be this book’s readers!) go to Venice, it isn’t exactly Venice now that we want to see, but a Venice before mass tourism, before tacky gift shops and the like — so we explore down side canals, quite away from the modern clamour (which indeed is still surprisingly easy to do), or escape the crowds by wandering through the city late in the evening. An essay on this theme, the attractions of travelling to sites steeped in history to try to capture that sense of times past, would have been good to have too.

Early on in the book, Emily Thomas distinguishes travelling not only from making a humdrum journey perhaps for work or study abroad (or a less humdrum journey as a refugee, perhaps) but also from going on a pilgrimage. Which got me wondering whether here too is a theme for another essay. For isn’t travelling, say, to Florence (braving Ryanair, and — if you can’t go in December! — braving crowds and unpleasant heat too) a pilgrimage of sorts for some of us? We are visiting Santa Maria Novella, Santa Maria del Carmine, Santa Croce, …, because they are still numinous places, the frescoes and paintings still expressive of feelings which have a deeper pull and give us pause. Or, when he writes of it long after, when the world he travelled through on foot has vanished, doesn’t Patrick Leigh Fermor’s walk from the Hook of Holland to Hungary and beyond take on in the telling something of the character of a pilgrimage through Old Europe, or perhaps something of the character of a romance-quest (another kind of journey)? I’m not sure: I would have liked to have heard still more, perhaps, about the varieties of travellings and their different meanings.

A writer Emily Thomas could perhaps have engaged with to add some further depth and nuance is Jonathan Raban (who oddly gets only the most fleeting mention for a comment about Byron). For Raban was not only one of the very best of all English prose writers in the last couple of decades of the last century, but the most reflective — philosophical, if you will — of travellers and travel writers. His late, great, Passage to Juneau (1999) should have appealed to the author of The Meaning of Travel, not only given some Raban’s themes (the discovery of otherness and of oneself in the process), but also given its location: some of Emily Thomas’s own book is structured loosely round her journeys through Alaska. But I’m thinking too of Raban’s earlier masterpiece, Old Glory from 1981, notionally recounting his travelling down the Mississippi in a small boat. I say “notionally” as this complex work is lightly disguised as a straight travel book, a literal recounting of a journey taken. But, as I’ve written here before, the one-time English literature lecturer warns us clearly enough. One of the epigraphs of the book is from T. S. Eliot (writing indeed of the Mississippi), starting “I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river/Is a strong brown god …” The other epigraph is from Jean François Millet: “One man may paint a picture from a careful drawing made on the spot, and another may paint the same scene from memory, from a brief but strong impression; and the last may succeed better in giving the character, the physiognomy of the place, though all the details may be inexact.” So we are set up for this to be a mythic tale, and for the “Jonathan Raban” who features as the narrator and his adventures to be a very inexact rendition of the author and his own journey. And a mythic tale is what we get, a romance-quest with ordeal by water, with auguries and signs, battles fought, a princess won (but also lost, for this is a flawed epic, and the journey ends in emptiness). Woven together with this are encounters with American myths of frontiers and journeys (more travelling!).

Raban’s is a many-layered book, particularly artful in the artlessness of its transparent prose. We are reminded that the lesser tales we tell ourselves about our own smaller travellings (at the time and after), while a lot less artful, are no doubt also shot through with their elements of fiction, as we weave our stories to fit some patterns we are perhaps only half-aware of. Which takes us back to The Meaning of Travel, which indeed has interesting things to say about the blurred lines between purely fictional travel narratives at one end of the spectrum and (say) some of Darwin’s writings at the other. It is such varied narratives which give our travels their varied meanings for us. Emily Thomas in her so-readable book helps us think about some of those narratives. I enjoyed it greatly!

The post The Meaning of Travel appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 27, 2020

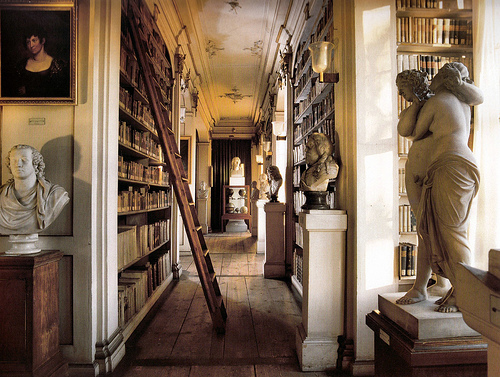

The book problem, revisited!

I’ve a lot of reading around and about logical matters I’d really like to catch up with, now that I have indeed sent off a final(?) version of IFL2 to CUP. Indeed, there is a rather ridiculously large number of new-ish books piled on my study floor (when will I ever learn?). An early task, then, is to do another major sort-through of older books, giving away ones that will never be read or referred to again, to make shelf room. Does anyone enjoy doing this? I certainly don’t! I’ve written about this problem before here, a number of times. Let’s have some excerpts again … leading to some wise advice (which I will try to heed!) about how to downsize your library!

I’m having to try to sort out my philosophy library — I can’t start shelving yet another wall at home — and that’s a painful business. It’s not just that there is a ridiculous number to sort through. It’s also a matter of encountering long-past philosophical selves, and not quite wanting to wave them goodbye. In the seventies, I was mostly interested in the philosophy of language (though there are also many ancient philosophy books dating from then, and a lot of Wittgenstein-related stuff); from the eighties there is a great number of books on the philosophy of mind; from the nineties a lot of philosophy of science and metaphysics. Digging through these archeological layers I’m reminded of past enthusiasms — not just of mine, but often quite widely shared enthusiasms which seemed philosophically rewarding at the time, but some of which now seem rather remote and even in some cases quite odd misdirections of energy. What creatures of fashion we are!

But at least in those more academically relaxed days I could follow my then interests wherever they led or didn’t lead (I never got bored). Young colleagues now don’t have the luxury: to get even their first permanent job they have to specialize, concentrate their resources, carve out a niche, build a research profile: and it takes more of the same to get promoted. Some feel constrained, lucky to have a job but trapped. The structures that we philosophers have allowed to be imposed on “the profession” (as we are now supposed to think of it) have thus come to be in real tension with the free-ranging cast of mind that gets many people into philosophy in the first place. What Marxists used to call a contradiction …

I’m still trying to sort out my (tiny) study at home. It all takes ridiculously long. Not just because I have to decide what to give to the library/students/Oxfam (though that’s difficult enough). But I find it impossible not to keep stopping over a book I haven’t opened in years and begin reading. I’m of the same mind as Churchill, who wrote

If you cannot read all your books, at any rate handle, or as it were, fondle them — peer into them, let them fall open where they will, read from the first sentence that arrests the eye, set them back on the shelves with your own hands, arrange them on your own plan so that if you do not know what is in them, you at least know where they are. Let them be your friends; let them at any rate be your acquaintances. If they cannot enter the circle of your life, do not deny them at least a nod of recognition.

And those nods of recognition as I move the books from one shelf to another all take so much time!

Chez Logic Matters, approximately

So you start buying books — I mean academic, work-related, books of one kind or another — in your late teens. As retirement age looms you’ve been doing it for the better part of fifty years. Suppose you average a couple of books a month. Not very difficult to do! You buy a few current books on topics that you are working on; books for reference; books you feel you should read anyway, given the ripples they are producing; books for seminars or reading groups you belong to; books it is useful to have to hand for teaching (the textbooks the kids are reading, or just useful collections of articles, before the days when everything was online). It very soon mounts up. Add in a few review copies, freebies, books given by friends, serendipitous finds rescued from the back of obscure second-hand bookshops (I got a set of Principia Mathematica that way). Then without any effort at all your modest library is steadily growing at over thirty books a year or more. But go figure: that’s already around 1500 books as you get to the end of your career. I’ve been a bit more incontinent than some, but actually not a lot (especially as my interests have rather jumped about). Say I’ve acquired 1750 over the years. I’ve got rid of a few books from time to time, of course, though I’ve been absurdly reluctant to let them go: but overall, I’ve still probably got not far short of 1600. Which, I agree, is a quite stupid number to end up with — but (as we’ve seen!) it’s easy enough to end up there without a ridiculously self-indulgent rate of book-buying as you go along.

Soon enough, I’m going to finally lose an office; and we’re trying to declutter at home anyway. So over the coming weeks and months I need to cut that number down. A lot. Halving is the order of the day. What to do?

Most of the Great Dead Philosophers and the commentaries can go — I can’t see myself ever being overwhelmed by a desire to re-read Locke’s Essay, for example (and anyway I can always get the text online). But that doesn’t make much of a dent, as I was never much into the history of philosophy anyway. I can get rid of some of the books-for-teaching, and old collections of articles whose contents are now instantly available on Jstor. But that doesn’t help particularly either. So now it gets difficult.

It could just be neurotic attachment of course! But I like to think that there is a bit more to it than that. I’m sure I’m never going to seriously work on chaos again, so — though it was great fun at the time — I guess I will let the chaotic dynamics books go fairly easily. I’m also pretty sure that I’m never going to seriously work on the philosophy of mind again, and I’ve never done anything in epistemology: but just axing the phil. mind and theory of knowledge books seems to go clean against how I think of philosophy, as the business of trying to understand “how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest sense of the term” as Sellars puts it. And anyway, some of the issues I’d like to understand better in the philosophy of mathematics seem to hang together with broader issues about representation and about knowledge. So perhaps I need to hang on to more of the mind and knowledge books after all ….?

No, no, that way madness lies (or at any rate, swamping by unnecessary books). After all, Cambridge is not exactly short of libraries, even if I do dump something I later find myself wanting to read again! So, I’m just going to have to be brutal. A few old friends apart, if I haven’t opened it in twenty years, it can certainly go. If it is just too remote from broadly logicky/phil mathsy stuff, it really better go too. Sigh.

… But now it is getting harder. I’m slowing down, and it is all getting more discombobulating. In some cases it is a matter of regretfully having to acknowledge that — being realistic — I am never going to have a year or so to really get my head again round X or Y. I’d love to really get to the point where I was sufficiently on top of the state of play in the philosophy of quantum mechanics (say), at least to follow some current debates; but it is never going to happen — or at least, it’s never going to happen if I am to have half a chance of finishing some logicky projects. So that whole area will have to remain a closed book, or rather a pile of closed books. A cheering reminder of faded hopes, eh?

Then there are the books to which I still feel an odd attachment and find difficult to let go for no reason I can easily articulate. Irrational, as I’ve not read them for decades, and I’m surrounded by Cambridge libraries. For instance, I’ve just found myself rereading some of Cornford’s Unwritten Philosophy, which I must have bought in 1967, and not had occasion to read much since. I’m sure it is all very creaky: ancient philosophy has come such a very long way since when Cornford was writing (the essays date from the thirties and forties). I’ve long since lost touch, and my Greek has quite disappeared. And yet, and yet … The charm of his writing still weaves its magic. No; this I think I will keep, just for a bit longer.

Back to the pile for sorting …

Hello. My name is Peter and I am a bookaholic …

Well, perhaps it isn’t quite as bad as that. But I’ve certainly bought far too many books over the years. I’ve now given a great number away, but retiring and losing office space means there is still a serious Book Problem at home. We want to do some re-organization, which will mean losing book shelving there too. So lots more must go. Dammit, the house is for us, not the books. One hears tell of retiring academics who have built an extension at home for their library or converted a garage into a book store. But that way madness lies (not to mention considerable expense).

“A little library, growing larger every year, is an honourable part of a man’s history. It is a man’s duty to have books. A library is not a luxury, but one of the necessaries of life.” Yes. But let “little” be the operative word!

Or so I now tell myself. Still it was — at the beginning — not exactly painless to let old friends go, or relinquish books that I’d never got that friendly with but always meant to, or give away those reproachful books that I ought to have read, and all the rest. After all, there goes my philosophical past, or at any rate the past I would have wanted to have (and similar rather depressing thoughts).

But I think I’ve now got a grip (so at last, here’s my advice to anyone else in the same position, needing to downsize). It’s a question of stopping looking backwards and instead thinking, realistically, about what I might want to think about seriously over the coming few years, and then aiming to cut right down to (a still generous) working library around and about that. So instead of daunting shelves of books reminding me about what I’m not going to do, there’ll be a much smaller and more cheering collection of books to encourage me in what I might really want to do. The power of positive thinking, eh?

And really, I have surprised myself. I can only remember one occasion when I’ve been kicking myself, really regretting some book I got rid of. Though, as I said at the beginning, I do seem to have acquired yet more books. I can’t imagine how that happened. Time, then, for another sort-out …

The post The book problem, revisited! appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 25, 2020

The Pavel Haas Quartet — at Cambridge

A few days after playing at Wigmore Hall, The Pavel Haas Quartet and Boris Giltburg were in Cambridge at the Peterhouse Theatre, again playing the Shostakovich Piano Quintet. This time, the other piece in the programme was Dvořák’s Op. 81 Piano Quintet.

One of PHQ’s remarkable gifts is to make performances of music that we know that they have rehearsed with great intensity sound freshly inspired, newly wrought. (The last quartet I heard in Cambridge was Quatuor Ebène, who are indeed fine — yet somehow they struck me as sounding too polished, and that surface gloss made it difficult to get an emotional grip on their performance.) PHQ recorded the Dvořák with Giltburg in 2017, and rightly won the highest praise for the disc and a Gramophone Award; but they played last night with such verve and warmth and evident love for the music, it was as if they had just recently discovered the piece. It is difficult to imagine, too, a more fitting match than between Giltburg’s mercurial playing and the Quartet’s — the happiest of musical partnerships.

I said after hearing their Shostakovich in London that I doubted that the Quintet could be played better. Yet, if anything, it was so last night. Perhaps it was the setting. Lovely though Wigmore Hall is, the small Peterhouse venue — seating just 180 people on two levels, so you can be no more than seven rows from the small stage — is a much more intimate space. And a group like the Pavel Haas, playing with characteristic passionate intensity, can then make a particularly intense impact. So in that venue, together with Boris Giltburg, their Shostakovich really took fire. Wonderful playing from all five of them.

(I was so caught up in the warmest applause at the end of the concert, I forget to turn on my phone to picture them responding wreathed in smiles — so here they are, deservedly looking equally cheerful, after another concert!)

The post The Pavel Haas Quartet — at Cambridge appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 23, 2020

Better late than never …

So here we are: four hundred and twenty pages of logical goodness, written with insight, clarity, zest, and wit, making it an unmissable read for students new and old.

So here we are: four hundred and twenty pages of logical goodness, written with insight, clarity, zest, and wit, making it an unmissable read for students new and old.

Well, that’s the theory ….

Kind friends and relations have said it is mostly not bad, give or take. On a good day, I can almost agree.

So, after a ridiculously protracted re-writing, I really will have to let this second edition of my Intro to Formal Logic go into the world this week and then take its chances. There’s a couple of (small) remaining tasks and then off to CUP with it!

I won’t tell you how many things that I ought to have realized decades ago when I started teaching this stuff that I’ve learnt (at last) in putting this edition together. That would be just too embarrassing. But better late than never …

The post Better late than never … appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 22, 2020

Raving on to the finish line …

The end is in sight for writing IFL2. Though through the great kindness of strangers, and some very last minute sets of very useful comments, I’m still editing up to the wire. I just came across this in Elizabeth Bowen’s novel The Death of the Heart:

Nothing arrives on paper as it started, and so much arrives that never started at all. To write is always to rave a little — even if one did once know what one meant.

Such indeed are the joys.

The post Raving on to the finish line … appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 21, 2020

The Pavel Haas Quartet — at Wigmore Hall

The Pavel Haas Quartet glimpsed rehearsing the Shostakovich Quintet for their Wigmore Hall concert on Wednesday with the terrific Boris Giltburg. The evening performance was wonderful, the best I’ve heard that piece played, full of ambiguities, tensions, life and colour. Indeed they rocked! (Or as the Times reviewer put it, they were at the top of their game. “The prelude was beautifully drawn, its counterpoint perfectly balanced. The sulphurous jig of the scherzo thickly painted, grimacing theatre music, while the intermezzo unfolded with magical transparency. There’s a volte-face in the finale to levity, a shift in tone that the quartet managed here with the grace of a master conjurer.”)

Here they are playing the intermezzo of the Quintet live on the BBC the previous evening (starting 43 mins in).

And here are just the Quartet on Swiss Radio, a concert they played in Geneva earlier in the month (Schulhoff, Quartet No. 1; Dvorák, Quartet No. 12, ‘American’; Tchaikovsky, Quartet No. 3).

The post The Pavel Haas Quartet — at Wigmore Hall appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 7, 2020

Luca Incurvati, Conceptions of Set

Quite delighted to pick up in the CUP bookshop Luca Incurvati’s newly published Conceptions of Set and the Foundations of Mathematics. I saw some draft chapters some years ago when Luca was still in Cambridge, and this should really be very good. (Hopefully there will be a cheap paperback version sooner rather than later — but meanwhile do make doubly sure your library gets a copy, and/or gets e-access via the Cambridge Core system!)

Quite delighted to pick up in the CUP bookshop Luca Incurvati’s newly published Conceptions of Set and the Foundations of Mathematics. I saw some draft chapters some years ago when Luca was still in Cambridge, and this should really be very good. (Hopefully there will be a cheap paperback version sooner rather than later — but meanwhile do make doubly sure your library gets a copy, and/or gets e-access via the Cambridge Core system!)

I’ve dipped in a little, and plan to blogpost about the book once I’ve finally sent off the camera-ready copy for IFL2 in a couple of weeks. (Yes, yes, you’ve heard it before; but the incremental revisions will come to an end, and Achilles will catch the tortoise, Zeno’s arrow will reach the target, and the my second edition will reach the publishers … the seemingly impossible sometimes happens.) In fact, I want more generally to get back to occasionally blogging about books as I read them, if only because I find it a very good way to fix my ideas. But in the meantime, it is back to fishing for typos and thinkos … What fun!

The post Luca Incurvati, Conceptions of Set appeared first on Logic Matters.

February 1, 2020

A European moment

This was new to me, and was being shared by some at the moment of Brexit, making a sunny counterpoint to what I found a rather miserable evening. If you too haven’t seen it before then, whatever your views, enjoy!

The post A European moment appeared first on Logic Matters.